Abstract

With advances in cyber threats and increased intelligence, incidents continue to occur related to new ways of using new technologies. In addition, as intelligent and advanced cyberattack technologies gradually increase, the limit of inefficient malicious code detection and analysis has been reached, and inaccurate detection rates for unknown malicious codes are increasing. Thus, this study used a machine learning algorithm to achieve a malicious file detection accuracy of more than 99%, along with a method for visualizing data for the detection of malicious files using the dynamic-analysis-based MITRE ATT&CK framework. The PE malware dataset was classified into Random Forest, Adaboost, and Gradient Boosting models. These models achieved accuracies of 99.3%, 98.4%, and 98.8%, respectively, and malicious file analysis results were derived through visualization by applying the MITRE ATT&CK matrix.

1. Introduction

The number of worldwide Internet users is increasing as a result of the development of new 5G and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. Consequently, malicious codes and cyberattacks that leak user information and cause financial damage are becoming more sophisticated and intelligent. In 91% of the cases, the inflow path of cyberattacks using malicious code starts from spear-phishing emails, and such attacks are initiated through attachments and links containing malicious code [1]. The detection and analysis of existing intrusions and malicious codes have been performed smoothly using the signature-based security control system. However, progressively developing malicious codes cannot be detected and analyzed by the existing security control systems, and false-positive and false-negative detection can increase explosively, making it difficult for administrators to judge and respond. In addition, static malicious code analysis technology is weak in terms of its inability to detect unknown malicious code, and dynamic malicious code analysis technology can be too slow. In addition, as a result of checking the rate at which the information protection systems of some companies and institutions can actually detect cyberattacks, most systems showed a detection rate of 60 to 70%, and about 30% of them had false detection and exception handling. This is a serious problem.

To respond to this, this paper proposes a method for visualizing malicious file detection data by applying a static-analysis-based machine learning (ML) algorithm to improve the shortcomings and mapping the dynamic analysis results to the MITRE ATT&CK (Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge) framework.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the ML methods used in the study and the visualization tool, the MITRE ATT&CK framework. Section 3 describes the experimental methods, and Section 4 contains the experimental results and discussion. The conclusion is presented in Section 5.

The main aim of this study was to perform a dynamic analysis of malicious and suspicious files and apply the results to the MITER ATT&CK framework to visually present the attack tactics and detailed techniques used for the files. This makes it easier for agents to identify and respond to threats. In addition, it utilizes the advantages of dynamic-analysis-based malicious file detection to increase detection accuracy. Malicious and suspicious files can be detected and analyzed, increasing the reliability of analysis and securing excellent on-site connectivity.

2. Related Work

2.1. ML

ML is a branch of AI and refers to a data analysis method that automates the building of analytic models. ML uses a large number of data for training and is mainly used to classify and predict data through a trained model. This section describes ML procedures and classification according to the learning methods [2,3,4].

ML Procedure

The ML procedure involves developing a model using training data and performing a test using the developed model. For example, ML can be used to create a model that can identify a person based on their picture, and then the generated model can be used to test and identify a picture with people in it. Although interpretations of ML procedures can vary, they are generally classified into seven stages when data management and processes for learning, such as data collection and preparation, are included in the ML stages [3,4,5]:

- Because the quantity and quality of the collected data directly affect the predictive model performance in ML, the first step is to collect high-quality data to build the model.

- The collected data are prepared using various preprocessing methods for model building. For example, preprocessing can be used to increase the size of the dataset or to denoise and/or segment images. Then, the dataset is split into two parts for training and testing.

- Many ML algorithms and models have been developed to solve various problems. In this step, the most appropriate ML model for the problem to be solved is selected. For example, some models are suitable for detecting image patterns, whereas others are more suitable for processing image data.

- This step is the heart of the ML process. A part of the dataset allocated for training is used to train the selected model. A model can be built based on trial and error. Thus, detailed experiments are required.

- When training is completed, the maturity of the model is verified through a test. This stage can test the generated model by evaluating how it actually works.

- After the evaluation, further improvement for learning can be considered, and the performance of the model can be improved by adjusting the parameters through hyper-parameter tuning.

- Because the ultimate goal of ML is to use data to answer problems, the value of ML models is determined by predicting what the given data mean using the models built and improved in the previous steps.

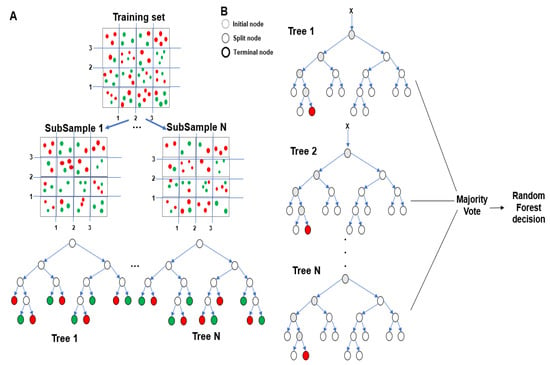

2.2. Random Forest (RF)

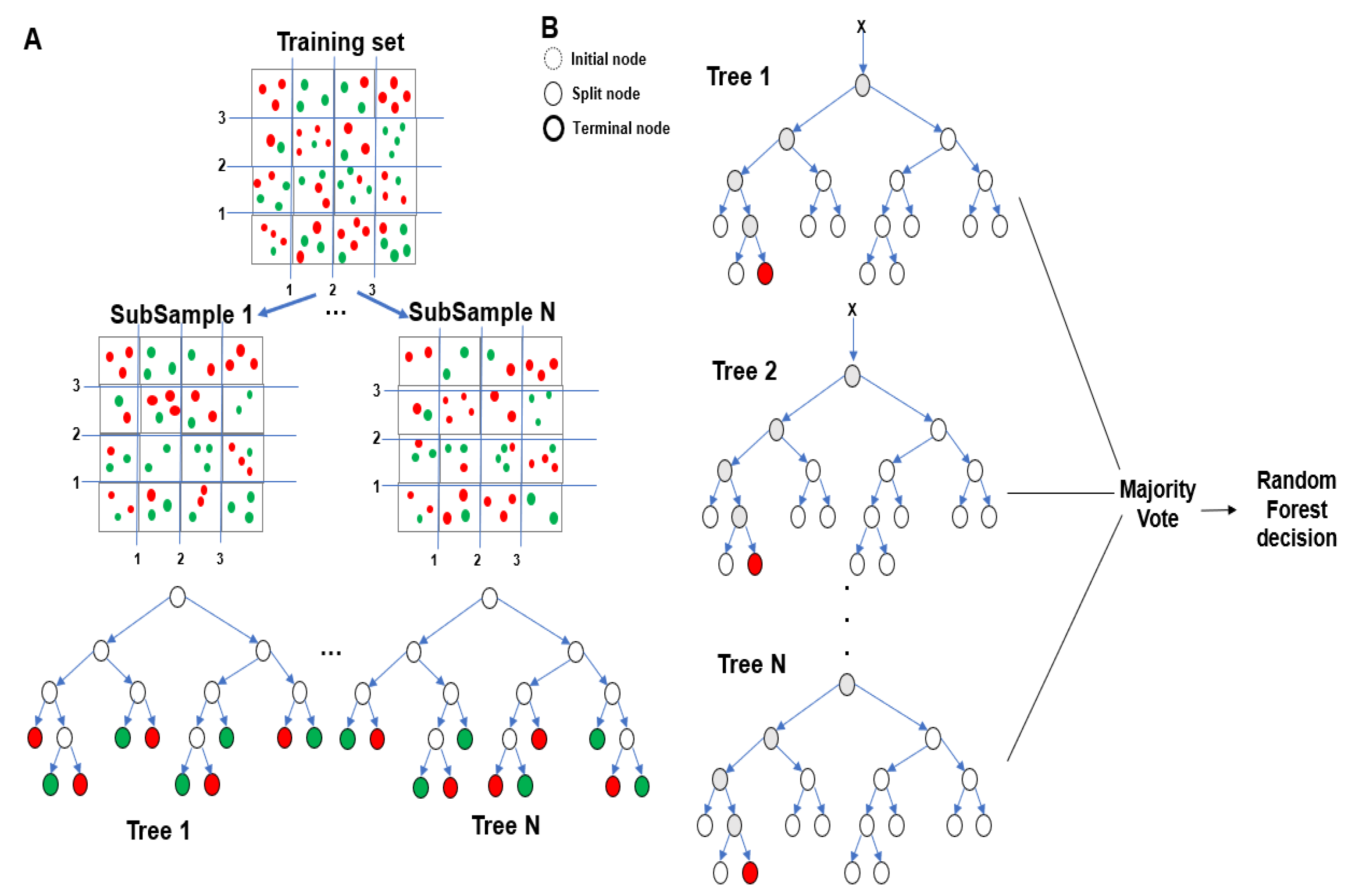

RF is an ensemble method for learning multiple decision trees. Its model is shown in Figure 1. As evident from Figure 1, it creates several decision trees with slightly different characteristics as a result of its randomness and outputs their averaged result. Through this method, the overfitting phenomenon that occurs when a single decision tree is used can be reduced [6].

Figure 1.

Random Forest (RF) model.

Various algorithms can be used in the ensemble method. Alternatively, the same algorithm can be used, but the learning method can be varied by randomly dividing the training set effectively to produce the desired effects. A process called bagging is used to generate trees in an RF. Bagging creates a decision tree by randomly selecting data from a dataset and creating multiple training sets. In this process, samples are extracted using bootstrap to allow restoration extraction [6]. The variance can be reduced by extracting a random bootstrap sample multiple times using bootstrap. The average of the extracted items is called bagging [7].

RF Characteristics

The most important characteristic of an RF is that trees have slightly different characteristics due to randomness. This characteristic causes the predictions of the trees to be decorrelated and unrelated to each other. As a result, the overfitting problem is overcome through randomization to improve the generalization performance. Additionally, randomization makes the forest robust against noise-containing data. For randomization, the learning background of each tree and randomized node optimization are frequently used. These two methods can be used simultaneously to further enhance the randomization characteristics.

The RF method can be used for both classification and regression problems because of these characteristics. It is effective for processing large numbers of data, avoids the overfitting problem that deepens the noise of the model, and improves the accuracy of the model to reduce the variability of the prediction [8].

2.3. Adaboost (AB) Algorithm

The AB algorithm can be used in combination with many other types of learning algorithms to improve the performance. It creates a selection criterion with high accuracy (strong classifier) by combining easy-to-derive selection criteria (weak classifier). AB can be applied to various situations so that subsequent weak learners can correct misclassifications by using the previous classifier. In other cases, it is not as susceptible to overfitting as other learning algorithms. Even if the performance of individual learners is poor, it is possible to prove that the final model converges to a strong learner if the performance of each learner is even slightly better than a random estimation [9,10].

AB refers to one method of training an accelerated classifier. The accelerated classifier is expressed in Equations (1) and (2) [10].

The classifier used in discrete AB expresses the result in the form of , whereas in real AB, the probability that the classification result is included in each class is expressed as . This represents the probability of being included in the element class called . Friedman et al. [10] derived , which minimizes for a fixed (which is chosen using the least-squares method).

AB using logistic regression realizes logistic acceleration. Instead of directly reducing the error in , we use a weak learner that minimizes (least-squares method) in the equation. is the term that minimizes the log-likelihood error for using Newton’s method. Moreover, is a weak learner that minimizes by using the least-squares method. The value of will be close to 0 or 1. Therefore, will also take a very small value. If the term has a large value or does not converge stably, then sample is misclassified. This problem was primarily be caused by the inaccuracy of the decimal point operation and can be avoided by forcing the maximum absolute value of or the minimum of [10].

2.4. Gradient Boosting (GB)

GB is an ML algorithm used for regression and classification tasks. We provide a predictive model in the form of an ensemble of weak predictive models, which are general decision trees. When the decision tree is a weak learner, the resulting algorithm is called a GB tree. The GB tree model is built in a stepwise fashion similar to other boosting methods; however, it generalizes to other methods by allowing arbitrary optimization [11]. GB is typically used as a base learner with fixed-sized decision trees. For such scenarios, Friedman proposed a modification to the GB method that improves the fit of each basic learner [11].

GB iteratively combines weak learners into a single strong learner. It is easiest to explain in a least-squares regression setup wherein the goal is to teach the model. To predict a value for form , , the actual value of the output variable of index n for sets of size , is converted to by minimizing the mean square error [12]. The accelerated classifier is expressed in Equation (3) [11]:

The GB algorithm is described as follows. Step : Assume some imperfect model of GB at each step, (low m, this model simply returns: ). With mean , to improve, the algorithm needs to add a new estimator ()). The accelerated classifier is expressed in Equation (4) [12].

2.5. Examples of AI-Based Malware Detection Technology

2.5.1. Kaspersky Lab’s ML-Based Malware Detection Technology Research

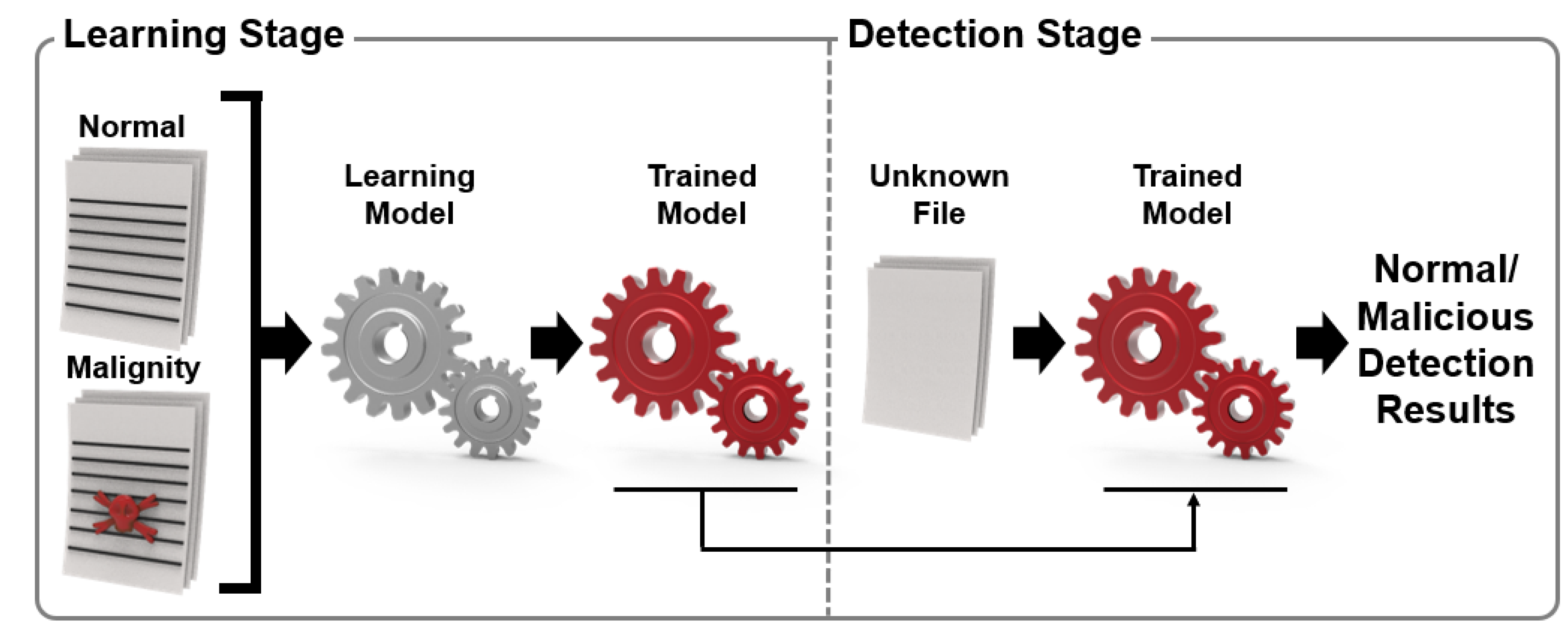

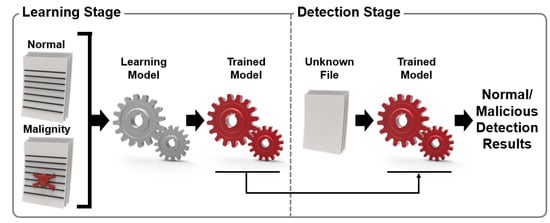

The Kaspersky Lab’s research direction involves learning ML algorithms with normal files and malicious codes and then developing a technology that detects whether suspicious files are malicious as a learning model. As shown in Figure 2, the model was optimized for malicious code detection by training the learning model with the feature information (string, command, byte information, API call history, etc.) and labels (normal, malicious, suspicious) of files [13].

Figure 2.

Basic malware detection system using machine learning (ML).

In addition, the Kaspersky Lab constructed an ML-based malware detection system and tested the detection process by dividing the detection process into the malware pre-execution stage and post-execution stage. The training information is utilized in the training phase when identifying the best model that produces the correct label Y for an entity given feature set X. In the case of malicious file detection, X acts as some function of the file content or file statistics, and a list of API functions is used. Label Y is a more accurate classification for malware or viruses and trojans. In the case of malware detection, it is a protection level. The system provides the user with a trained model that makes autonomous decisions based on model predictions. However, this can have adverse consequences for users, such as accidentally uninstalling OS drivers. To prevent such mistakes, a process that can classify normal/malignant/suspicious files through training and verification steps using an ML algorithm is presented [13].

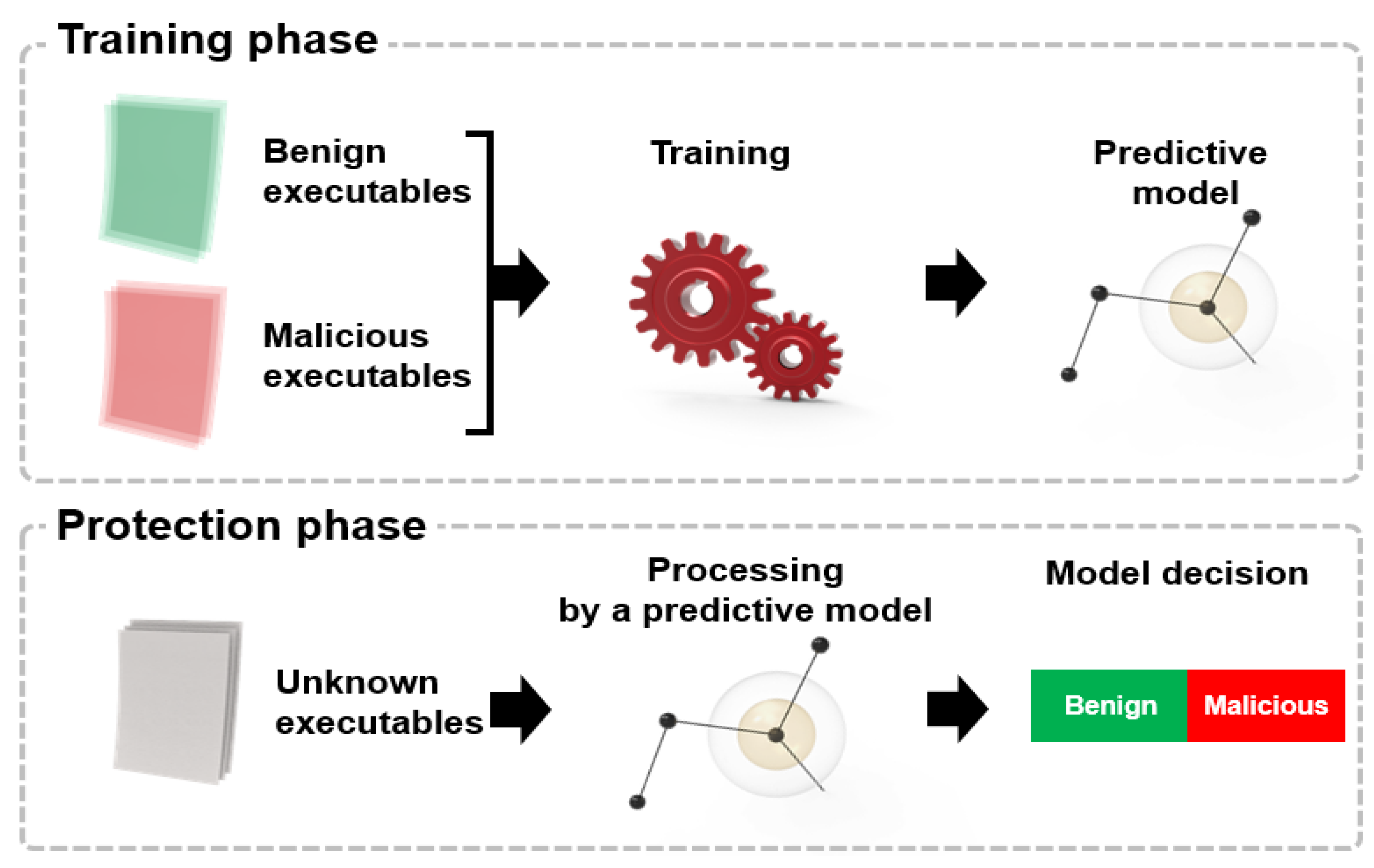

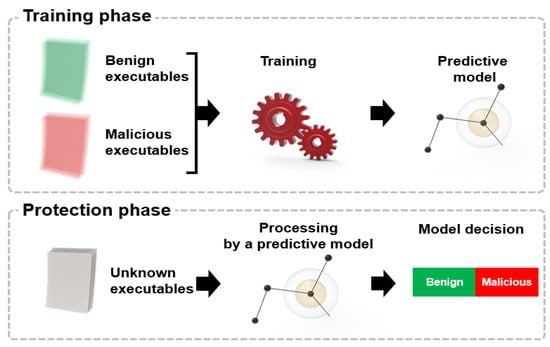

During the training phase, you need to choose a model family such as neural networks or decision trees, as shown in Figure 3. Each model in the family is usually determined by its parameters. Training means searching for a model within a selected family with a specific set of parameters that gives the most accurate answer to a model trained on a set of reference objects according to a specific metric. That is, it "learns" the optimal parameters that define a valid mapping from X to Y. After training the model and checking its quality, we are ready for the next step: applying the model to new objects. At this stage, the model type and its parameters remain unchanged. The model only produces predictions.

Figure 3.

ML: detection algorithm life cycle.

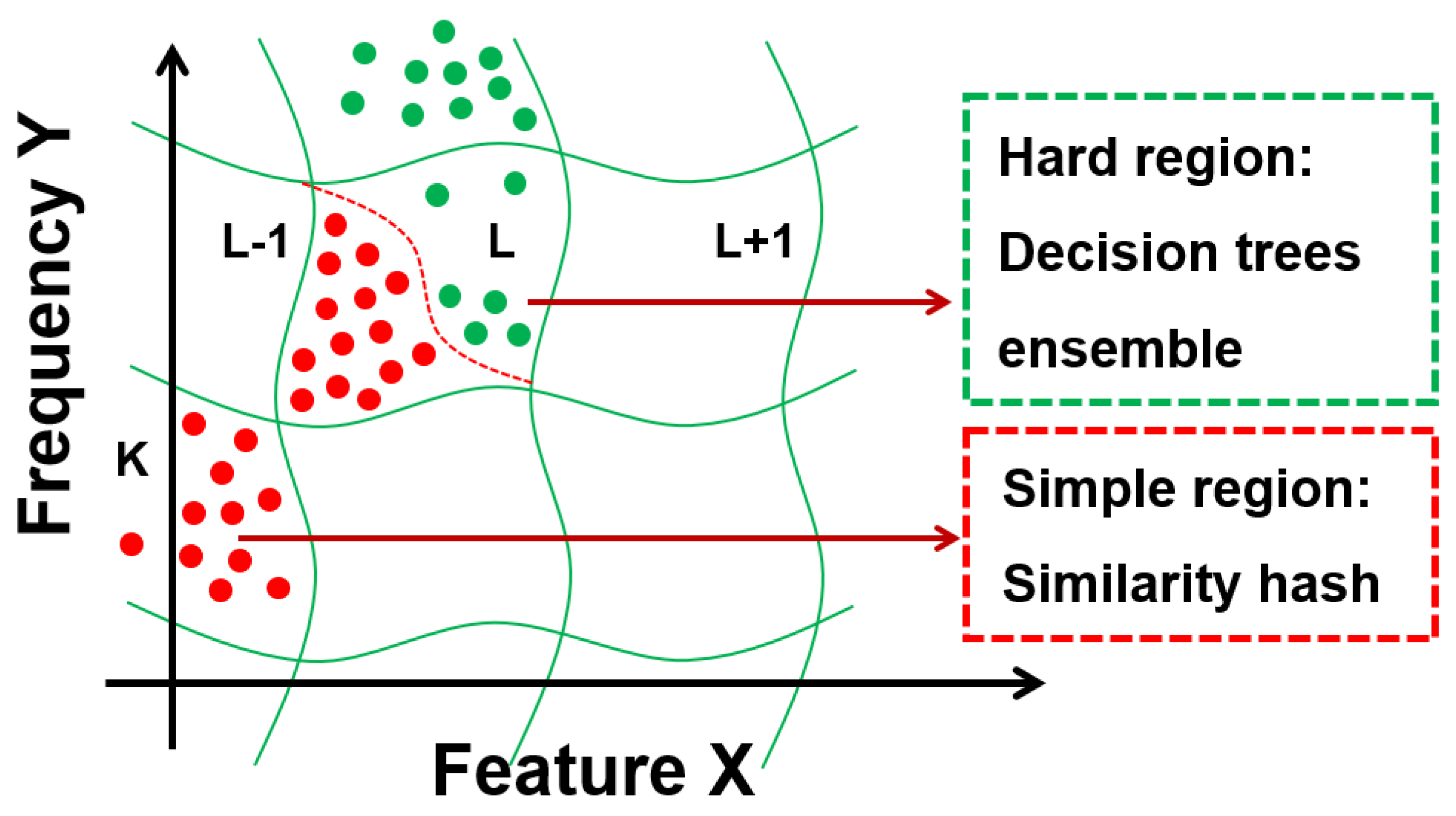

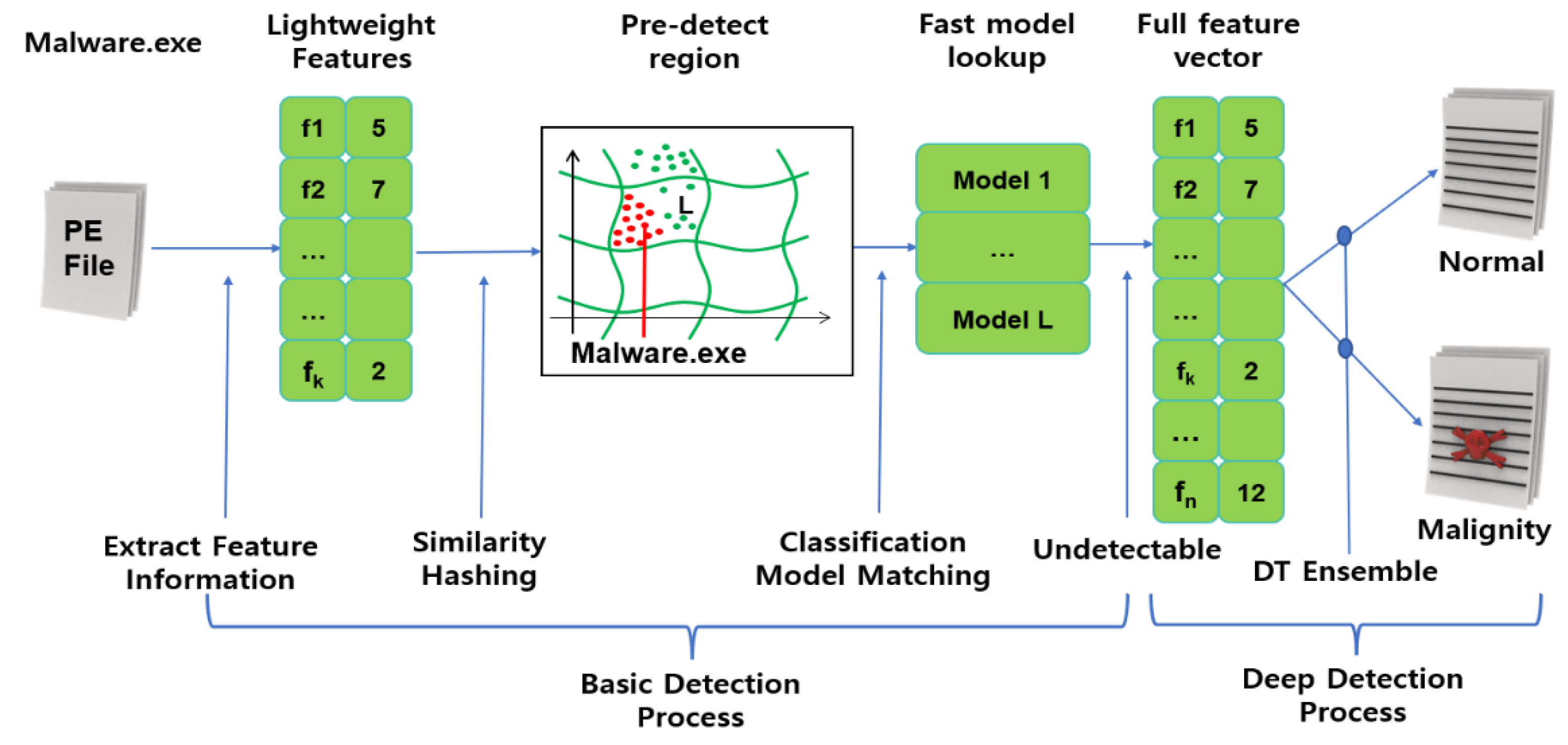

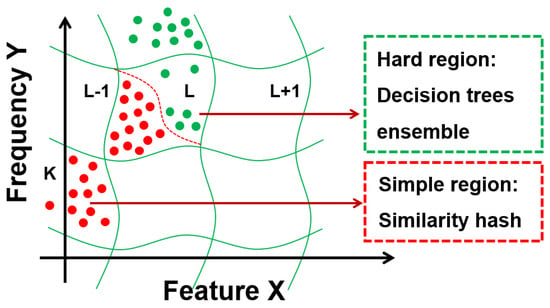

As shown in Figure 4, pre-execution was conducted on the user’s computer using a similarity hash mapping combined with a decision tree ensemble. When applied to executable file functions, this algorithm provides specific similarity hash mappings along with useful detection capabilities. Several versions of this mapping were trained with different sensitivities to local transformations of different feature sets. One version of the similarity hash mapping focused more on capturing the executable file structure while giving less attention to the actual content. Another focused more on capturing the ASCII string of the file. This feature could be used to detect the presence of unknown malicious packets through file content statistics. The most important information related to potential behavior is concentrated in the OS API used, the file name created, the URL accessed, or another string.

Figure 4.

ML: segmentation of object space.

The results of the similarity hashing algorithm were combined with other ML-based detection methods for more accurate detection by the system. To analyze the files in the pre-execution stage, the Kaspersky Lab combined the similarity hashing approach with other trained algorithms in a two-stage approach. To train this model, we used a large malware dataset [13].

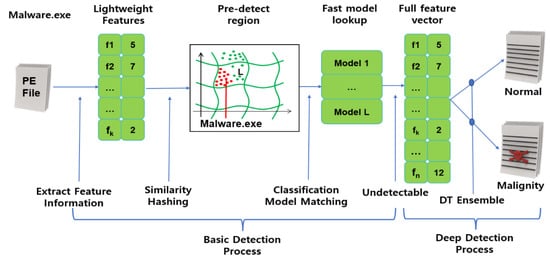

As shown in Figure 5, the pre-execution stage is divided into basic detection, deep detection, and learning rare malicious code according to malicious code information. Basic detection plays a role in classifying code as normal or malicious by learning similarity hashing with the basic characteristic information of executable files. Similarity hashing classifies malicious files into an appropriate bucket according to the hash value of the feature information, and it performs in-depth detection when a normal/malicious file is mixed in a bucket. In deep detection, a similarity hashing function is trained with all the extractable lightweight features and then classifies files as normal/malignant using an ensemble algorithm. If normal/malicious files are mixed in the classification result, the rare malicious code learning step is performed.

Figure 5.

Pre-execution basic detection and deep detection processing process.

The extracted feature information is applied to ML and deep learning (DL) models that detect rare malicious codes and similar malicious codes. If it is difficult to classify malicious files in the pre-execution stage because of encryption or obfuscation, the post-execution stage is performed. The post-execution stage detects malicious code by training a DL model with the information collected by executing the malicious file.

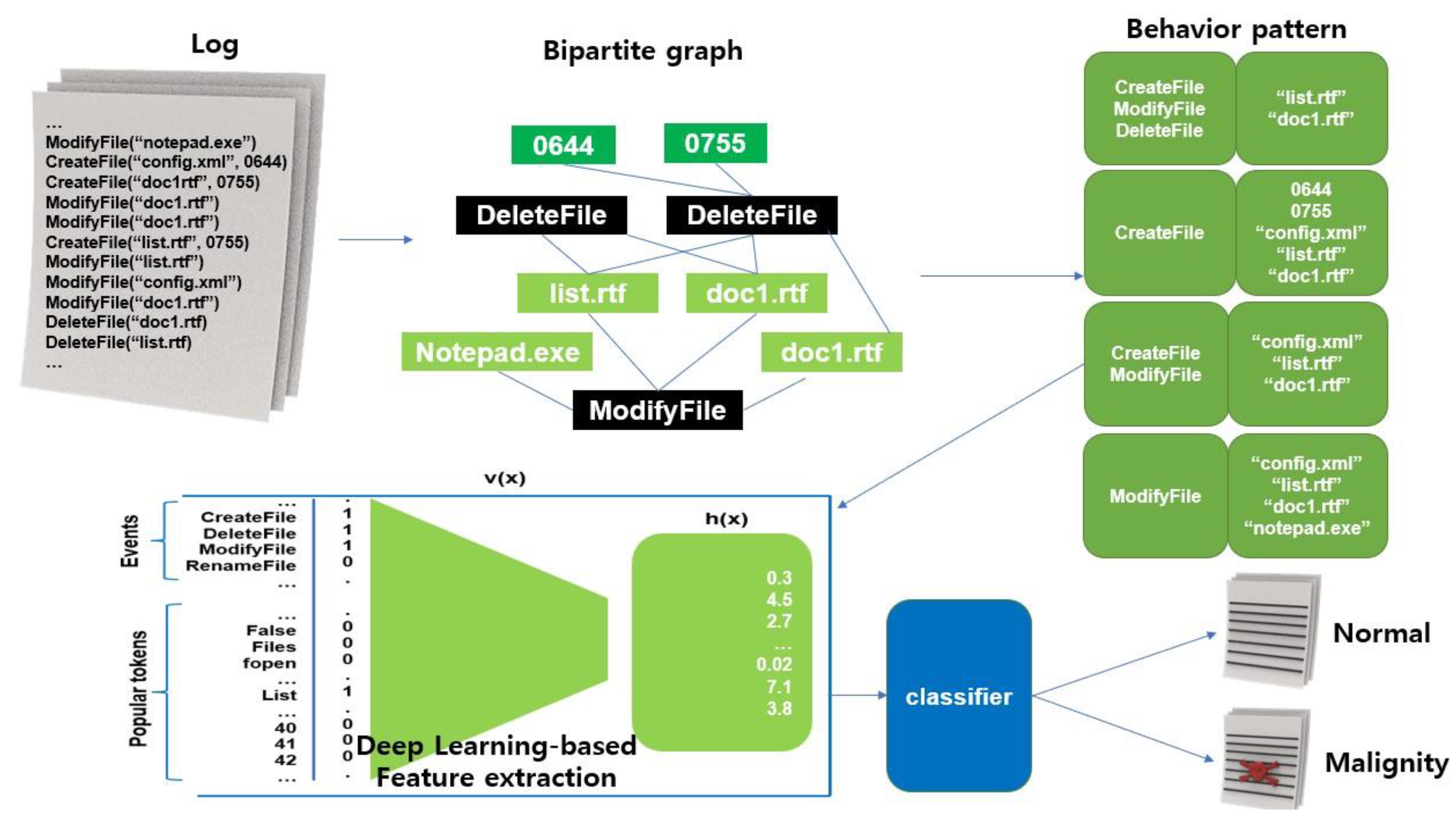

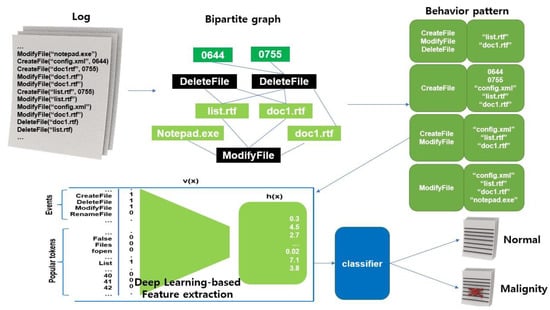

As shown in Figure 6, it creates behavior graphs and behavior patterns using the process and behavior records collected when executing malicious code, extracts key characteristic information about the behavior patterns created with a DL-based model, and then classifies and judges them as normal/malignant through the classification model. An experiment showed that considering the robustness, scalability, throughput, and explainability of the system, a good detection performance was guaranteed even for small changes in malicious code. In addition, a system was built that is suitable for processing a large amount of malicious code and allows a user to understand the detection results [13].

Figure 6.

Post-execution processing process.

2.5.2. Research on NVIDIA’s DL-Based Malware Detection Technology

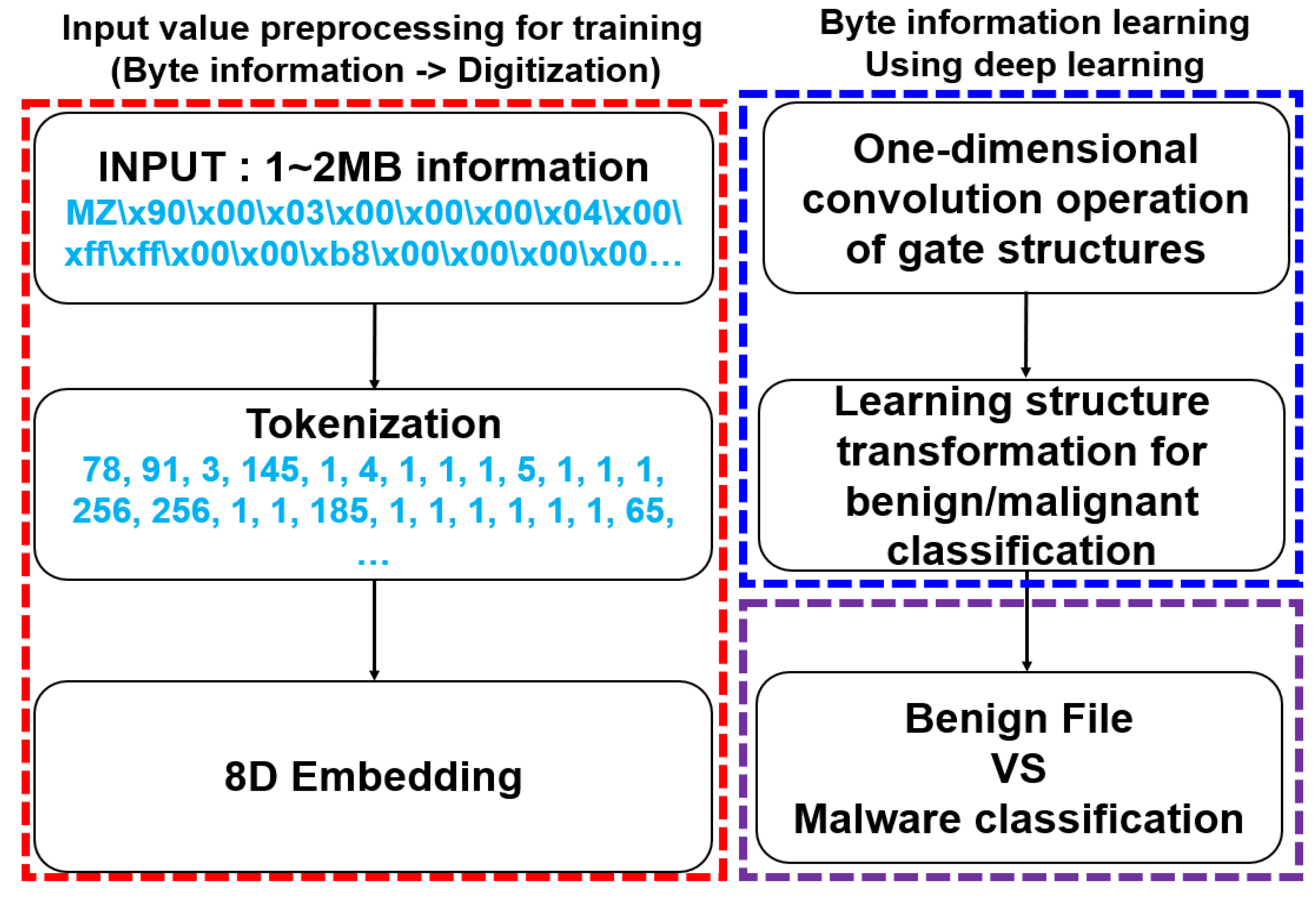

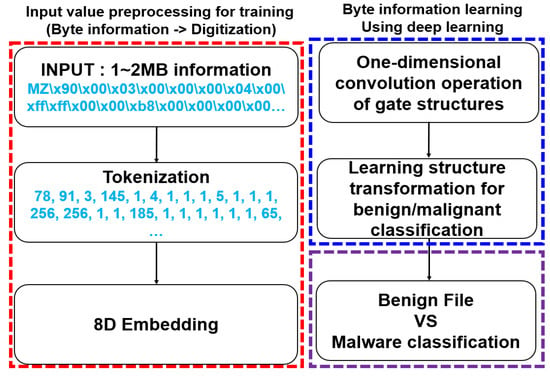

As shown in Figure 7, NVIDIA conducted an experiment to detect malicious files by training a DL model with the byte information of files to detect malicious files in Windows executable files. As for the system configuration, the system for detecting malicious files consisted of preprocessing the byte information of executable files, training a DL model with the byte information, and classifying normal and malicious files [14,15].

Figure 7.

DL-based malware classification model architecture.

To preprocess the input value for learning the DL model, the byte information (hexadecimal) of the executable file was converted into a form suitable for the input value of the learning algorithm. It learned by applying a gate structure that performed two convolutional operations on a convolutional neural network and adding a structure for classifying whether it was normal or malignant. Normal files and malicious codes were classified using the DL results.

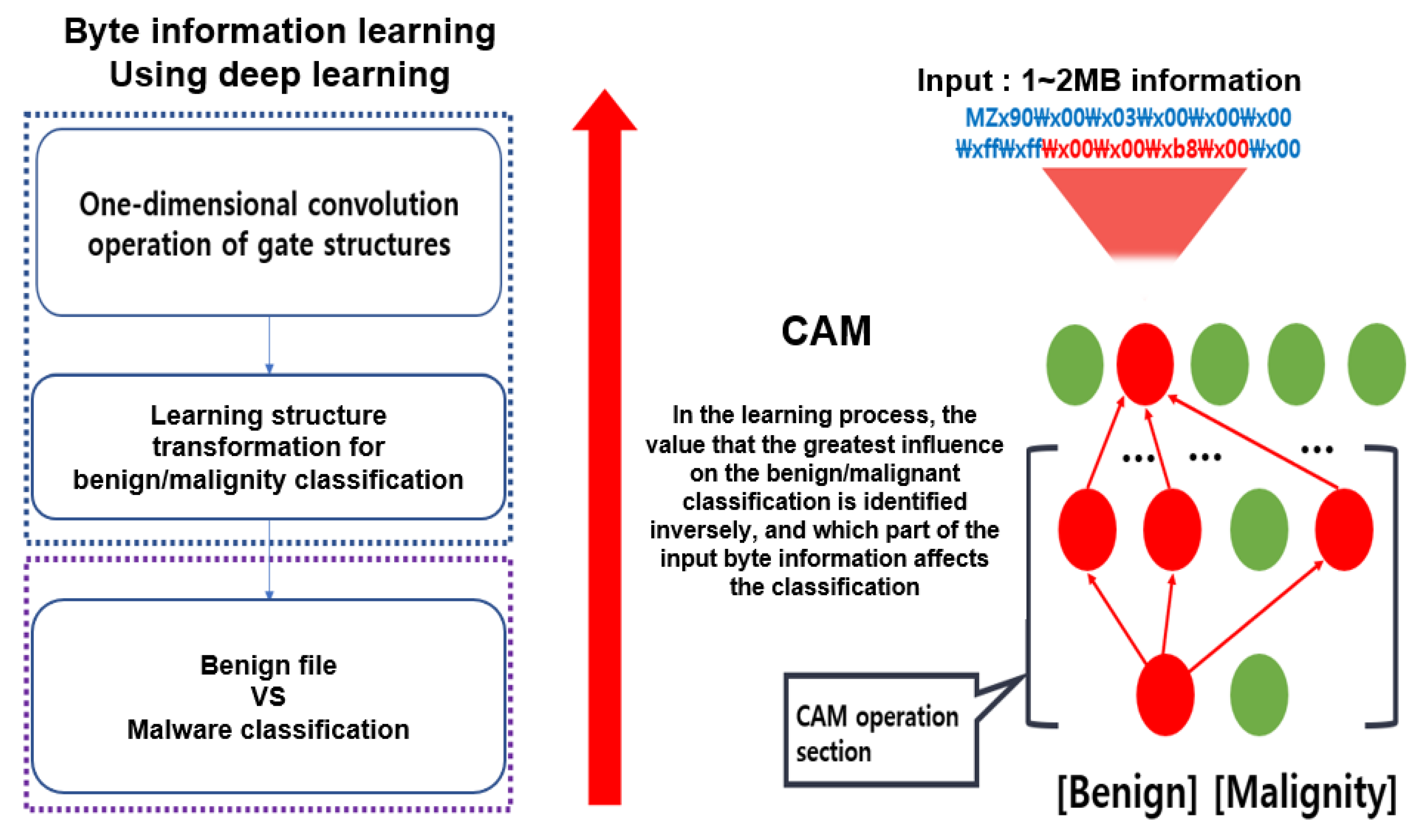

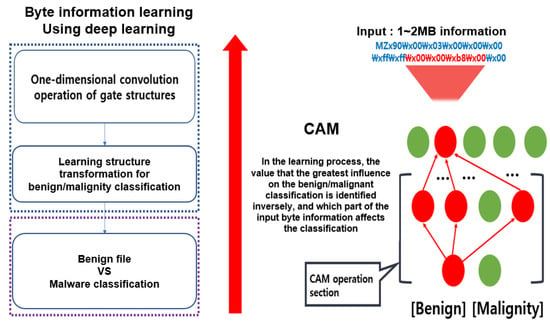

To derive the classification criteria, NVIDIA used the class activation map (CAM) method to find the basis for classifying executable files as malicious codes. In the learning process of the CAM method, the value that has the greatest influence on the normal/malignant classification is identified inversely to confirm the part of the input byte information that affects the classification. This process is illustrated in Figure 8 [15].

Figure 8.

Searching for byte part with the greatest impact on malicious code classification using the class activation map (CAM) method.

The validity of the proposed model (Malconv) was verified by comparing its accuracy with that of the learning model using byte block and file meta information as feature information by NVIDIA.

As seen in the experiment, NVIDIA guaranteed good detection performance even for small changes in malicious code by considering the generality, robustness, scalability, throughput, explainability, and dependency on feature information when designing a system. Additionally, for a general-purpose system, a dataset for training was used. By using only byte information, the process of extracting feature information was reduced, and a system was built that was suitable for processing a large amount of malicious code and could help administrators understand the detection results.

2.6. Malicious File Detection Method

Malicious file detection can be based on static and dynamic analyses. Malicious file detection based on static analysis involves detecting malicious code by extracting the characteristics of the file. It does not directly execute the file, and it has the advantages of fast detection and high accuracy. However, because the previously analyzed malicious files are detected based on the collected database, unknown malicious codes cannot be detected. Malicious file detection based on dynamic analysis involves detecting malicious files by directly executing the file in a virtual environment (VMware, Virtual Box, etc.) and analyzing it. It can detect and analyze unknown malicious files, but the disadvantage is that detection is slow and the efficiency is low [16,17]. Preliminary work on malware analysis using static analysis mainly focused on malware detection approaches. Known malware patterns were identified in [18]. Evaluation of a printable character-based malicious PE file-detection method via an approach using semantic behavior to prevent some specific code obfuscation was presented in 2021 [19]. The PE file we used is a file format for executable files, DLL object codes, FON font files, etc., used in the Windows operating system. The OE file refers to a data structure encapsulating information necessary for the Windows loader to manage executable codes. There are four types of PE files: Execution, Driver, Library, and Object. Executables include EXE and SCR, Drivers include SYS and VXD, and the Library family includes DLL, OCX, CPL, and DRV. There is OBJ in the object family. The reason why you should use a PE file is that the PE structure can see all the information for the file to be executed. You can check the API used by the program or which memory address the file is loaded into. Through the PE file, it is possible to check and collect various information, such as file attribute values, header values, signatures, magic, AddressOfEntryPoint, Image Base, and SizeOfHeader. We extracted the aforementioned information through the Google Colab analysis environment, which can analyze PE files based on Python [19].

Pandey, Sonal, Lal, and Ram and Schultz et al. proposed a study to improve the accuracy and speed of Opcode-based Android malware detection using machine learning techniques [20]. In 2021, Amirah Alshammari and Abdulaziz proposed a method to efficiently detect and analyze malicious network traffic in cloud computing by applying machine learning technology [21]. In 2020, Firoz Khan et al. [22] suggested that malicious URL detection is an important part of many cybersecurity applications and has provided a robust way to incorporate the necessary security measures into machine learning strategies. In this study, we developed a complete prototype for detection of malicious URLs using machine learning methods. In particular, we proposed an approach that attempts an exact formulation of malicious URL exposure from a machine learning perspective and uses the AdaBoost algorithm. The proposed approach has higher accuracy than other existing algorithms. The reason for choosing this particular boosting technique was that the AdaBoost algorithm could be used with other machine learning algorithms. Tina Rezaei et al., “A PE header-based method for malware detection using clustering and deep embedding techniques”, Journal of Information Security and Applications, Vol. 60, August 2021 [23], Ce Liab et al., “A novel deep framework for dynamic malware detection based on API sequence intrinsic features”, Computers & Security, Vol. 116, Issue C, May 2022 [24], Arzu Gorgulu et al., “Sequential opcode embedding-based malware detection method”, Computers & Electrical Engineering, Vol. 98, March 2022 [25], and Ahmed Bensaoud et al., “Deep multi-task learning for malware image classification”, Journal of Information Security and Applications, Vol. 64, February 2022 [26].

Recently, a malware dataset released on Kaggle was studied [27]. Ahmadi et al. [28] used Microsoft malware datasets to perform 16-dump-based functions (n-gram, metadata, entropy, image representation, and string length) and extracted functions from disassembled files (metadata, opcode, register, etc.). They obtained a 99.8% detection accuracy using the XGBoost classification algorithm. In 2017, Drew et al. [29] used a super threaded reference-free alignment-free Nsequence decoder (STRAND) classifier to classify polymorphic malware and presented an ASM sequence model that achieved an accuracy of over 99.59% through replacement verification.

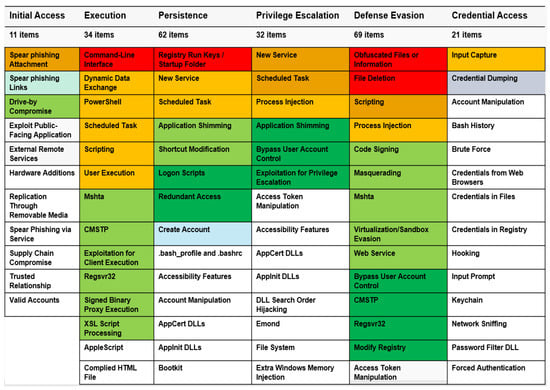

2.7. Visualization Using MITRE ATT&CK Framework

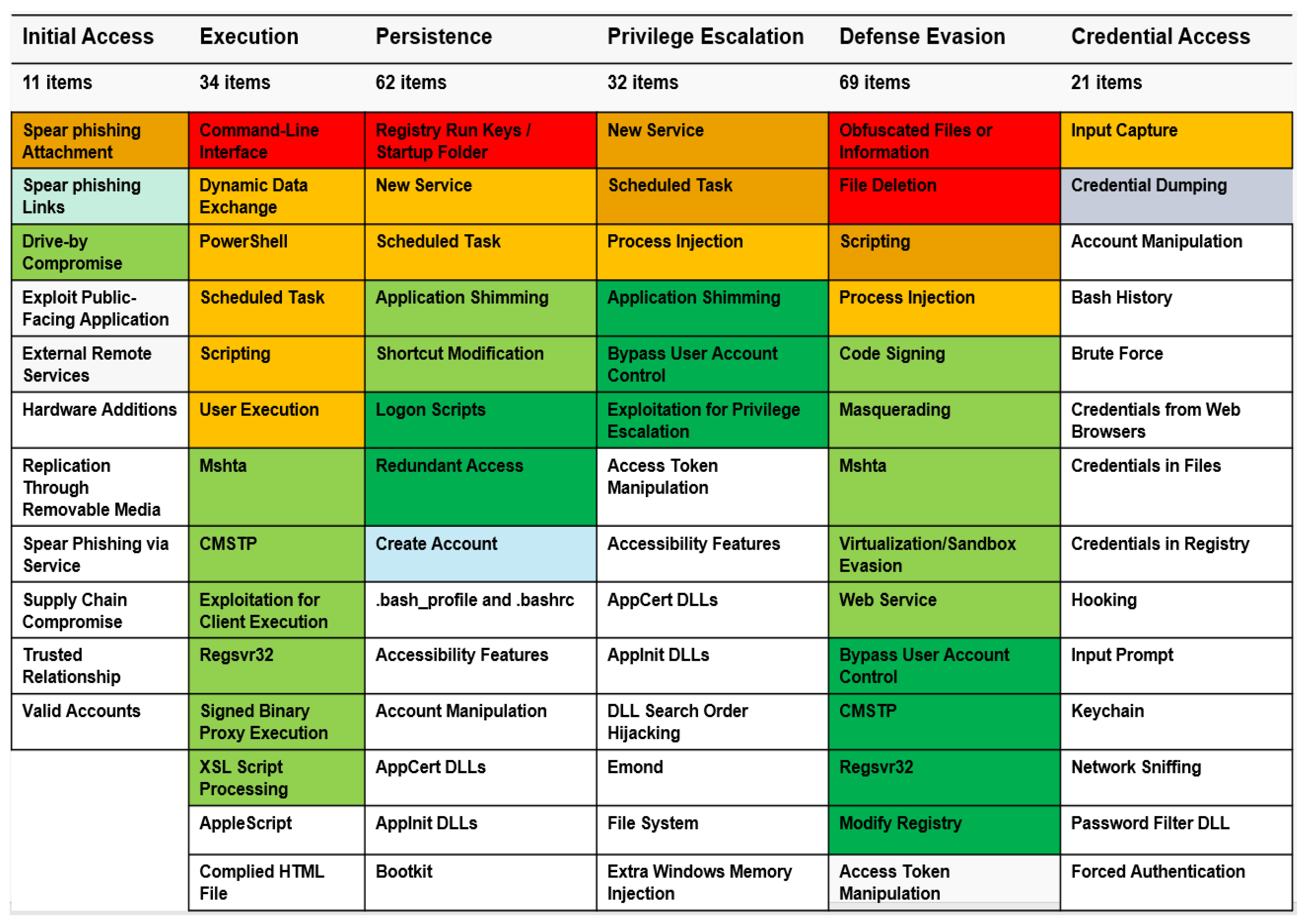

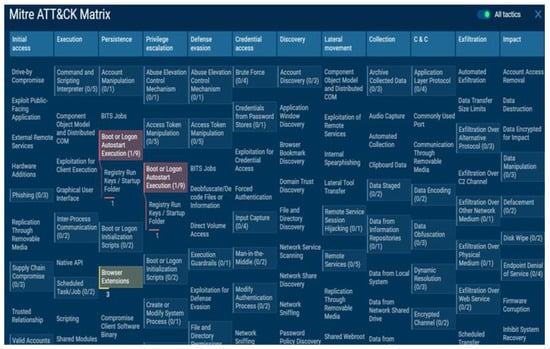

MITRE ATT&CK is an abbreviation of Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge. After observing actual cyberattack cases, the malicious behaviors used by attackers are analyzed from the perspective of attack methods (tactics) and technology. These are standard data that classify and catalog information about attack methods used by threat actors. Figure 9 is a framework derived from a part of the ATT&CK matrix proposed by MITRE. It is a systematization (patterning) of threatening tactics and techniques to improve the detection of intelligent attacks, which is slightly different from the concept of the traditional cyber kill chain. It started by documenting TTPs such as methods (tactics), techniques (techniques), and procedures (procedures). Afterwards, it developed into a framework that can identify the attacker’s behavior by mapping the TTPs’ information based on the analysis of the consistent attack behavior pattern generated by the attacker [30,31,32,33].

Figure 9.

MITRE ATT&CK Framework.

The MITRE ATT&CK website provides information in various categories, such as Matrices Mitigations, Groups, and Software, and through this, you can check attack information and countermeasures related to tactics and techniques of the system. The matrix information visualizes the concepts and relationships of attack techniques, tactics and technique. Here, tactics represents the action according to the attacker’s attack goal, and techniques represents the method for the attacker to achieve tactics for the goal. Mitigations refers to actions (techniques) that defenders (administrators) can take to prevent and detect attacks. Groups means data organized by analyzing information and attack techniques on publicly named hacking groups, and software means data organized by hacking tools used by hackers.

2.8. Voting Classifier Ensemble Modeling Studies

The study proposed by Kye Woong Lee et al. [34] combined 132 feature points, learned a model using Decision Tree, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Adaboost, and XGBoost with 98 methods excluding 34 privileges, and measured the validation accuracy within the table number for each single algorithm. As a result of the measurement, the accuracy of DT 93.1%, RF 95.2%, GB 94.9%, AB 93.9%, and XGB 93.8% was confirmed.

Choi Seung-oh et al. [35] proposed building a test bed to analyze MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques and to collect elastic-based control system security datasets. The main aim is to develop a tool that transforms and expands the dataset obtained from the test bed according to various user scenarios in order to overcome the limitations of the dataset collected from the test bed. However, from the point of view of this thesis, it can be regarded as a proposed study based on simple collection and monitoring in terms of security control.

In the study by Kris Oosthoek et al. [36], we observed an increasing number of techniques applied to sideload DLLs to evade fileless malware execution, security software detection, and defense within our dataset, and more sophisticated techniques and command and control (C&C) were observed. These observations have identified ways in which malware authors are innovating technologies to circumvent traditional defenses.

Amir Afianian et al. [37] proposed Malware Dynamic Analysis Evasion Techniques: A Survey. This content appears to have used a sandbox and seems to be a research topic using technologies that can be analyzed manually and automatically.

The comparative analysis results of these studies and this paper are dealt with in Section 5: Comparison.

3. Materials and Methods

After analyzing files using static analysis techniques, a pre-trained ML model was applied to a dataset containing malicious and normal files, and the ML model identified malicious/normal/suspicious files. At this time, if a dynamic analysis was performed and the detection data result was mapped to the ATT&CK framework through app.any.run, the experiments showed that the detection result could be visualized using the ATT&CK framework.

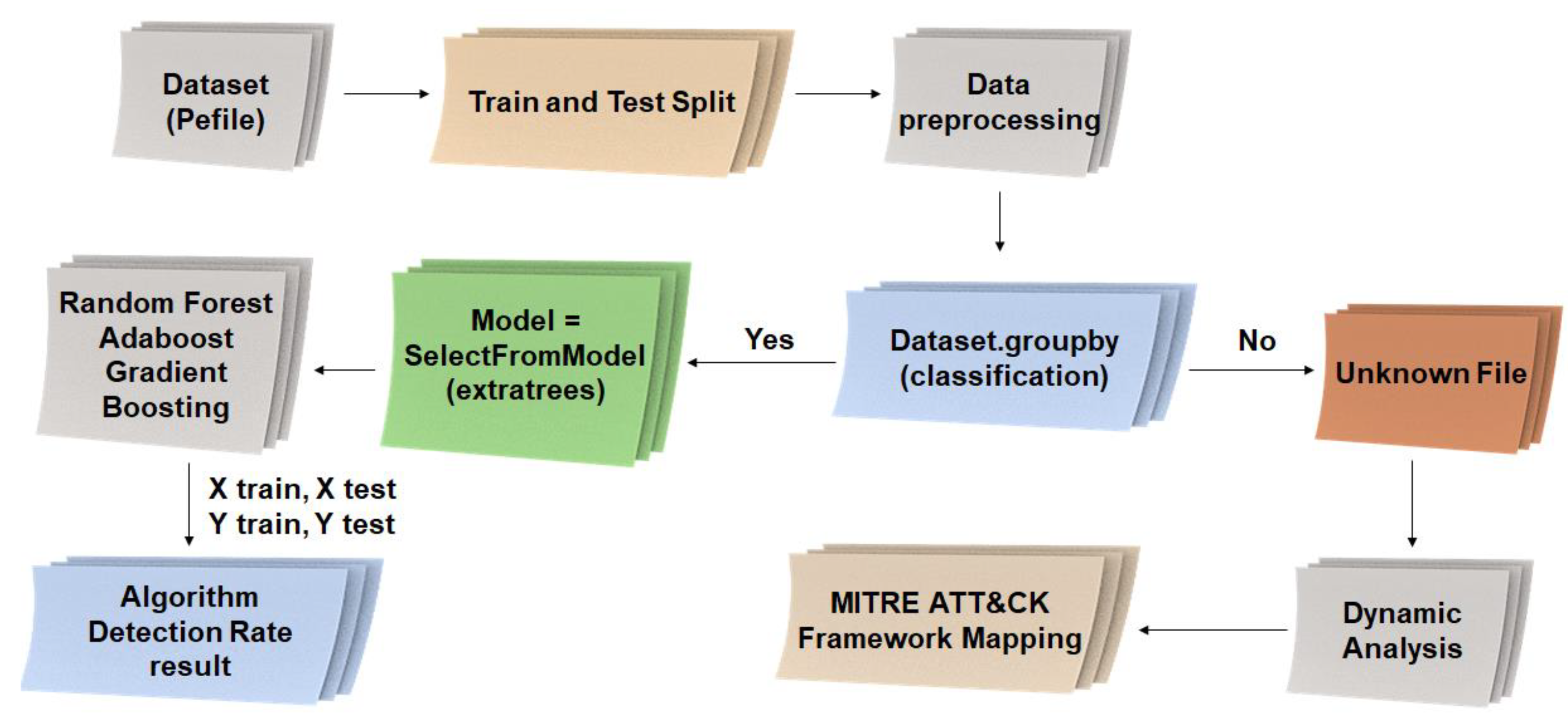

3.1. Flowchart of Experimental Process

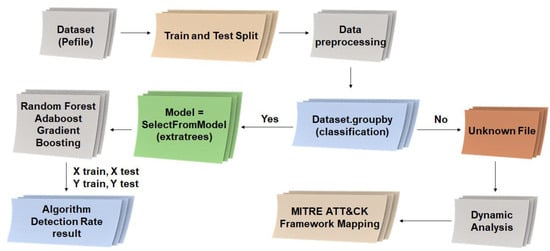

The experimental environment and process followed in this study are illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Experimental environment and configuration diagram.

There are two ways to analyze a dataset to derive results. First, if train and test split is applied and data preprocessing is performed, all information in the dataset is classified into malicious, normal, and suspicious file information. Among these, data that cannot be classified can be regarded as a suspicious file, and a dynamic analysis is performed on the suspicious file and the result is applied to the MITER ATT&CK framework to provide a visual part.

Second, in order to increase the detection accuracy of normal and malicious files when classifying datasets, selector codes for machine learning models are generated and selected using Random Forest, Adaboost, and Gradient Boosting algorithms, and the algorithm is improved by repeating training and testing. It is possible to extract the result of the detection rate.

3.2. Experimental Environment

For the virtual machine used for a dynamic analysis, with the Ubuntu and Windows 7 operating systems, the app.any.run system was used, with the Python pefile module used for the static analysis. The dataset was saved as a csv file using Kaggle. RF, AB, and GB were used as the ML algorithms, and tests were conducted using Google Colab.

3.3. Dataset

The experimental dataset was used on the public kaggle site. This was achieved using a raw PEByte stream and a csv file containing tens of thousands of data points obtained by downloading the merged PE malware dataset into a 32-byte vector. To detect static-analysis-based malicious files, we imported various modules (os, pandas, pickle, numpy, pefile, etc.) based on Python, utilized the analysis environment to extract features from files, and applied them to pre-trained ML models. They were classified into normal and malicious files. Table 1 lists the classified legitimate and malicious file results.

Table 1.

Legitimate file classification results.

Malicious Code Analysis and Feature Extraction

Dataset analysis was conducted using Google Colab to build an experimental environment, and analysis was attempted by importing various modules (os, pandas, numpy, pickle, pefile, joblib, etc.) based on Python. As a result, the data in the dataset were successfully classified into a normal file and a malicious file. The results are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Malicious code analysis and feature extraction results (partial).

By using 0 for normal files and 1 for malicious files, it is easy to distinguish between normal files and malicious files. The first column of the dataset is Name, which indicates the file name. The second column indicates MD5 hash values for normal and malicious files. In the third column, legitimate files are classified as 0 and malicious files as 1. The fourth column indicates the size of the file, and finally, Magic indicates the PE format. It was clearly classified into one of two categories: normal and malignant. The accelerated classifier is expressed as Equations (5) and (6) [11].

In the interpretation of the above formula, when the probability of predicting maliciousness is greater than or equal to the true-negative rate (TNR), the file is determined to be malicious. Moreover, if the probability of a normal prediction is greater than or equal to the true-positive rate (TPR), the file is determined to be normal. For the remaining probabilities, the file is determined to be unknown.

3.4. Data Preprocessing of Dataset

Table 3 shows the training process of the ML model, which is a data preprocessing process that removes unnecessary data so that the ML model can easily access and learn the dataset and classify its contents as malicious or normal files.

Table 3.

Part of contradictory data (before preprocessing).

3.5. Training and Test Data Split

The data column is Xlist, the label is Ylist, and training and test split process involves dividing the training and test data with a 7:3 ratio for use in the learning and verification processes of the model, respectively. The value of test_size in the training and test split function is set to 0.3 to achieve this ratio, and the results are listed in Table 4. The red border in Table 4 shows the training set, and the green border shows the test set.

Table 4.

Training and test split results.

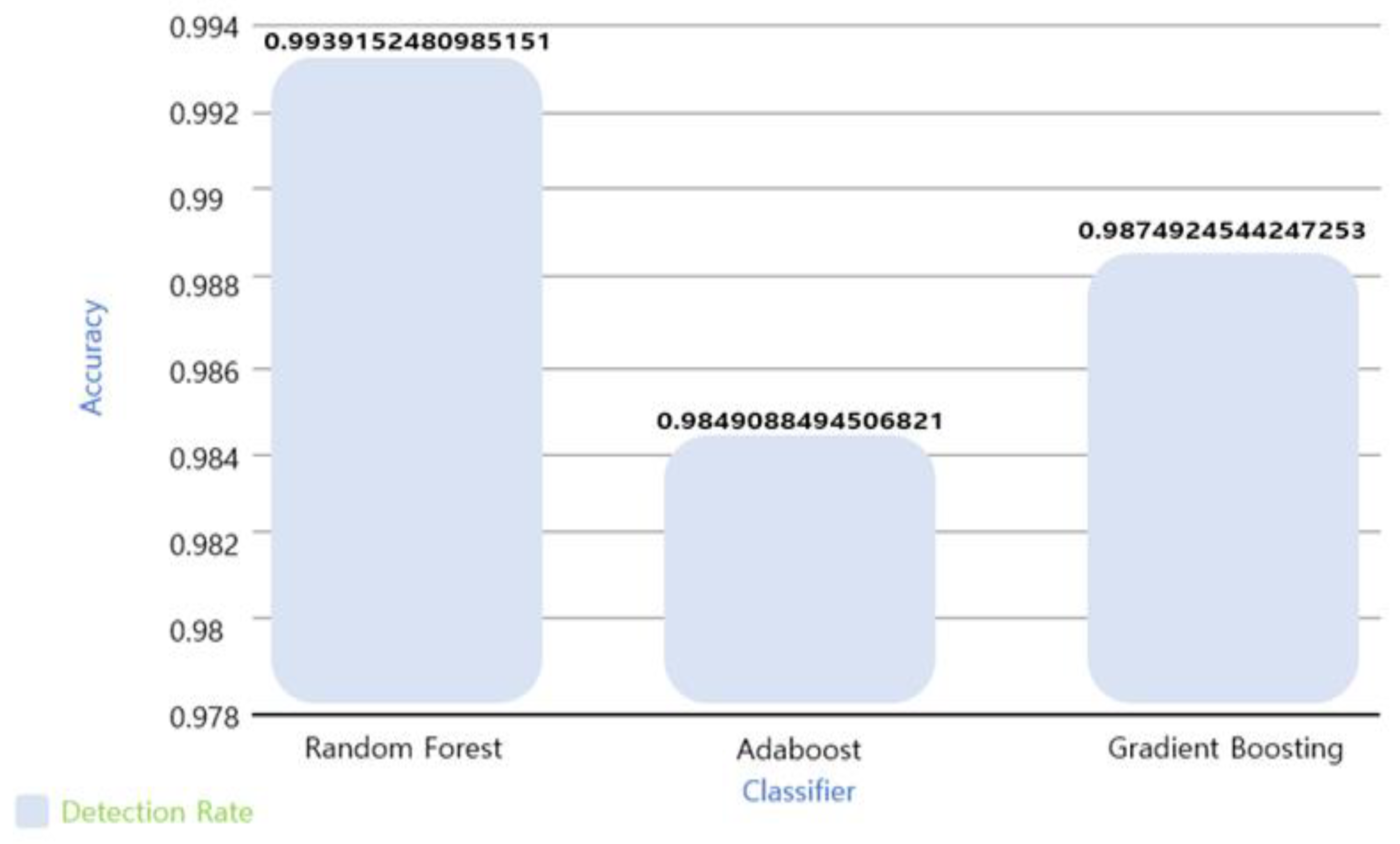

3.6. Training of Classifiers

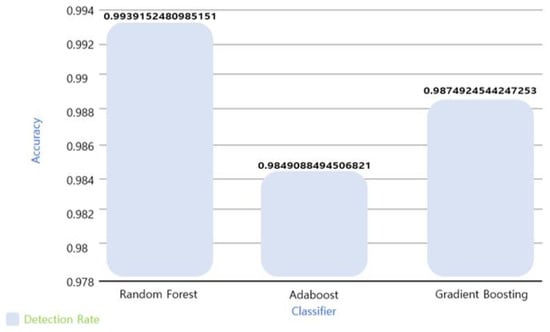

After feature selection using the train_test_split data, the next step was to identify the classifier of the optimal ML algorithm for intelligent malware detection. The experimental results of classifying the optimal model by quantifying the accuracy (detection rate) via pre-training the RF, AB, and GB models are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Classifier training results.

From Figure 11, it can be seen that the best model in terms of the detection rate accuracy was RF. All the trees in RF go through an independent training stage. In the test phase, data point v is entered into all the trees simultaneously to reach the end node. These test steps are performed in parallel, and high computational efficiency is achieved through a parallel GPU or CPU. The prediction result for RF is obtained as the average of the prediction results of all the trees. Classification is performed using Equation (7).

3.7. Malware Detection

In Section 3.6, among the three classifiers selected for the depth analysis, RF had the highest accuracy. In total, 49,376 malicious files and 2583 benign files corresponding to 95% of the entire dataset were randomly selected. Table 4 shows the detection accuracy results for the three classifiers.

4. Results

The TPR, TNR, false-positive rate (FPR), false-negative rate (FNR), and accuracy can be defined. Classification is performed using Equations (8)–(10) [38].

Table 5 lists the accuracy results for RF, GB, and AB in descending order of accuracy.

Table 5.

Accuracy results for top 3 classifiers: True Positive: normal file detection; False Positive: detection of normal files identified as malicious; False Negative: detection of malicious files identified as normal.

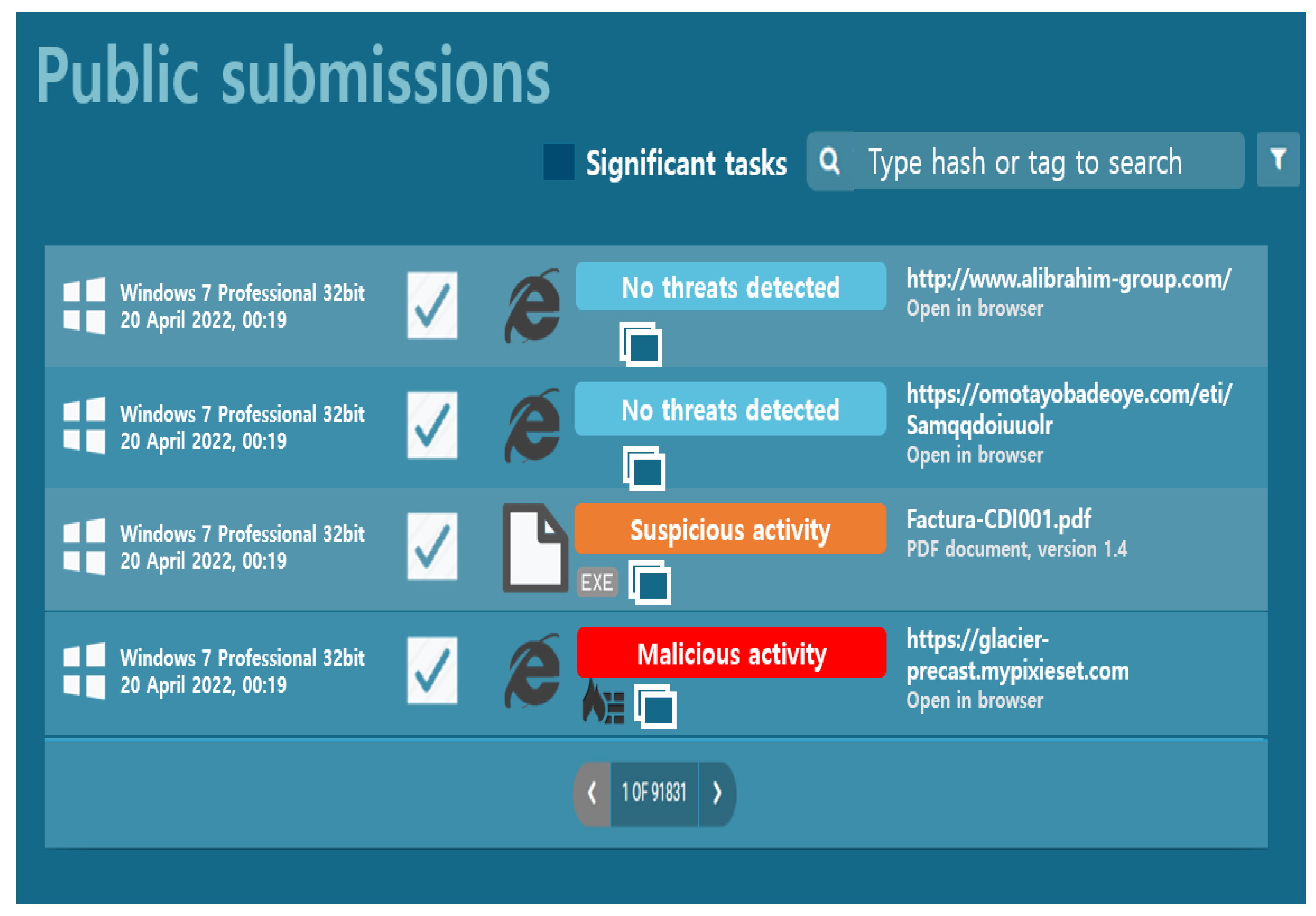

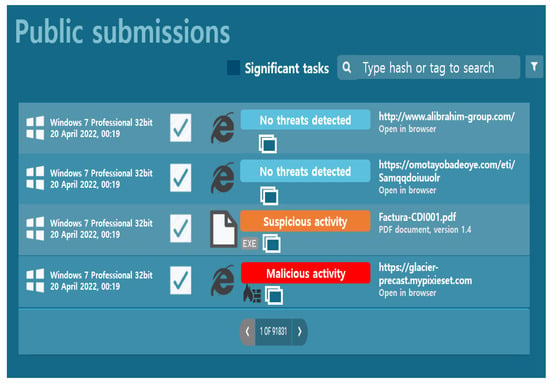

App.Any.Run

As shown in Figure 12, app.any.run, a representative service for automated malicious code analysis, is a program that analyzes the threat of malicious code files and normal files in detail. It provides results for various operating systems and office environments such as document-type malicious code and executable EXE malicious code. In addition, it supports many optional filter searches, and the Hunter version provides infinite API requests, allowing a user to quickly respond to security threats. The search filter function allows filtering based on hash information, character information included in the analysis function, and a specific script. In operating system filtering, it is possible to filter based only on the unwindowed version. From Windows XP to Windows 10, a search can be performed according to the operating system. Furthermore, it is possible to search by file type. If “Scripts” is selected, the VBA, VBE, BAT, and TXT file types are searched, and if “Verdict not specified” is selected below and then “malicious” is selected, only malicious code is searched.

Figure 12.

Classification of malicious and normal files by operating system.

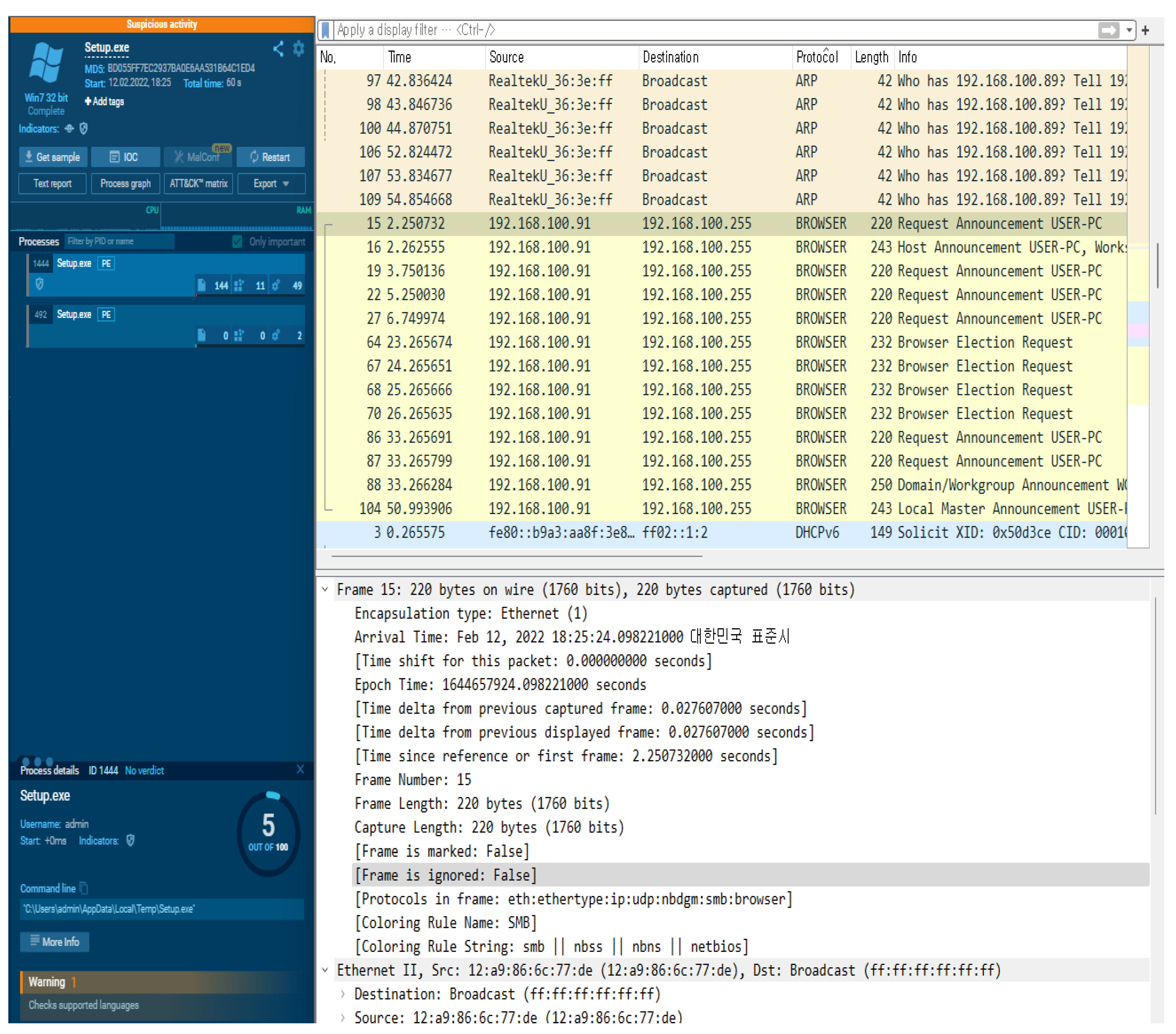

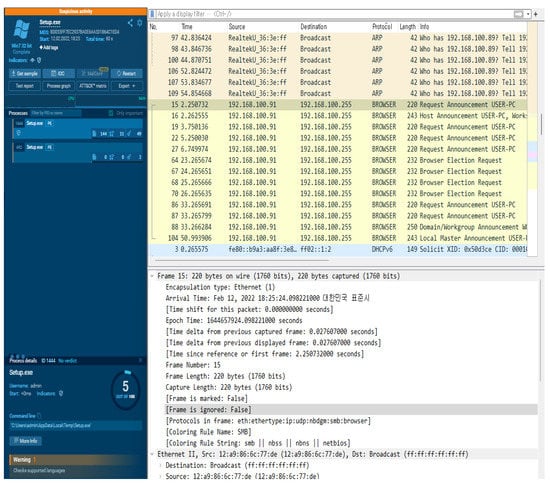

For the dynamic analysis of malicious code, a virtual environment (Windows 7 32 bit) was built, and a suspicious file (setup.exe) was executed and analyzed using the app.any.run system. Figure 13 shows the TCP Stream result data of the pcap file through the Wireshark program.

Figure 13.

Setup.exe malicious file packet analysis result.

The malicious file was analyzed using the Wireshark function provided by app.any.run. Based on the analysis, two malicious codes using the .cab extension and the URL of the distribution site were found in the setup.exe packet. The HTTP request packet analysis result data are shown in Table 6, and the network connection results are shown in Table 7. Table 8 shows the result of DNS Requests packet analysis. Table 9 lists the results of the modifications to the malicious files.

Table 6.

HTTP request packet analysis results.

Table 7.

Network connection packet analysis results.

Table 8.

DNS Requests packet analysis results.

Table 9.

File modifications.

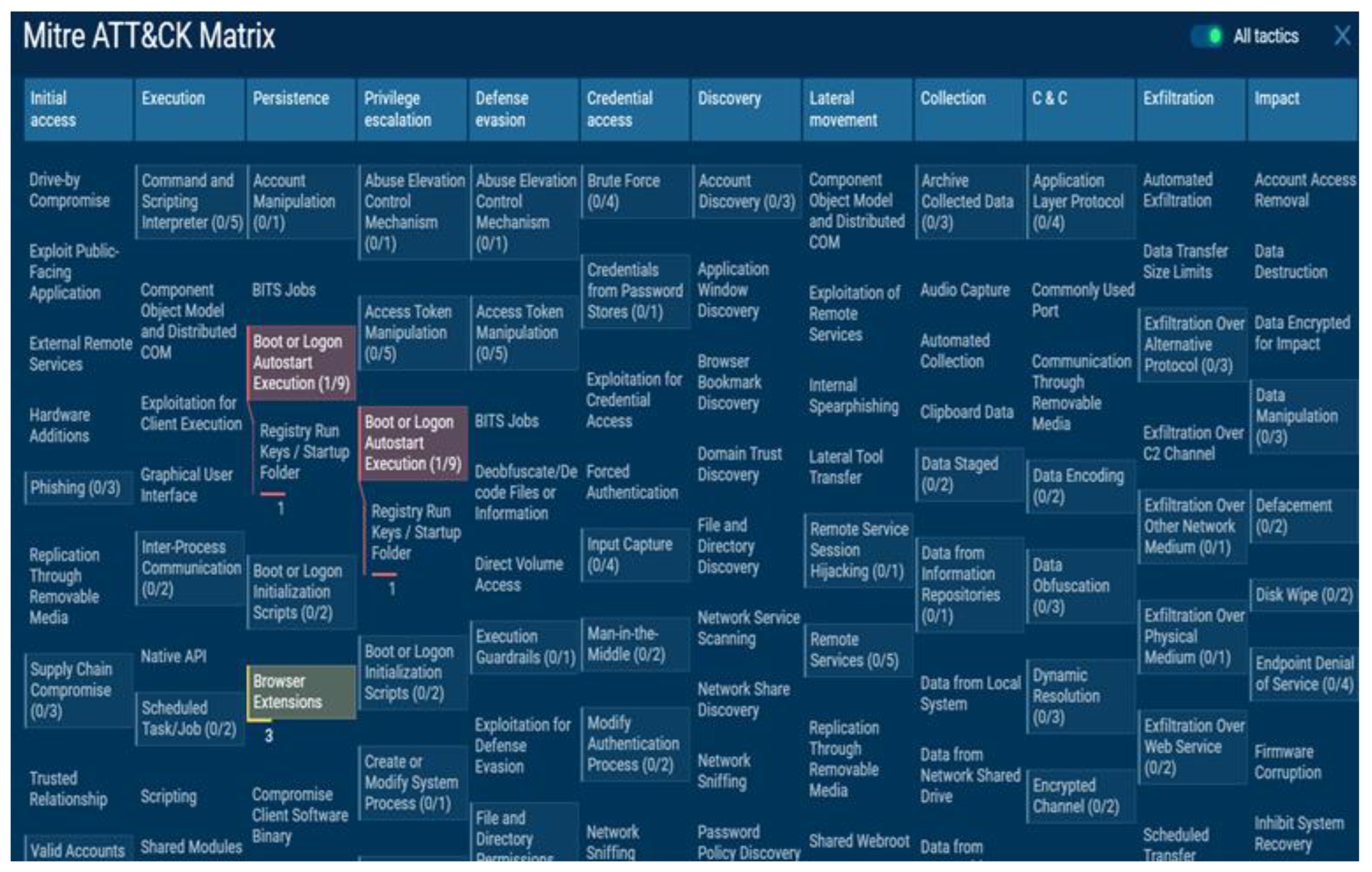

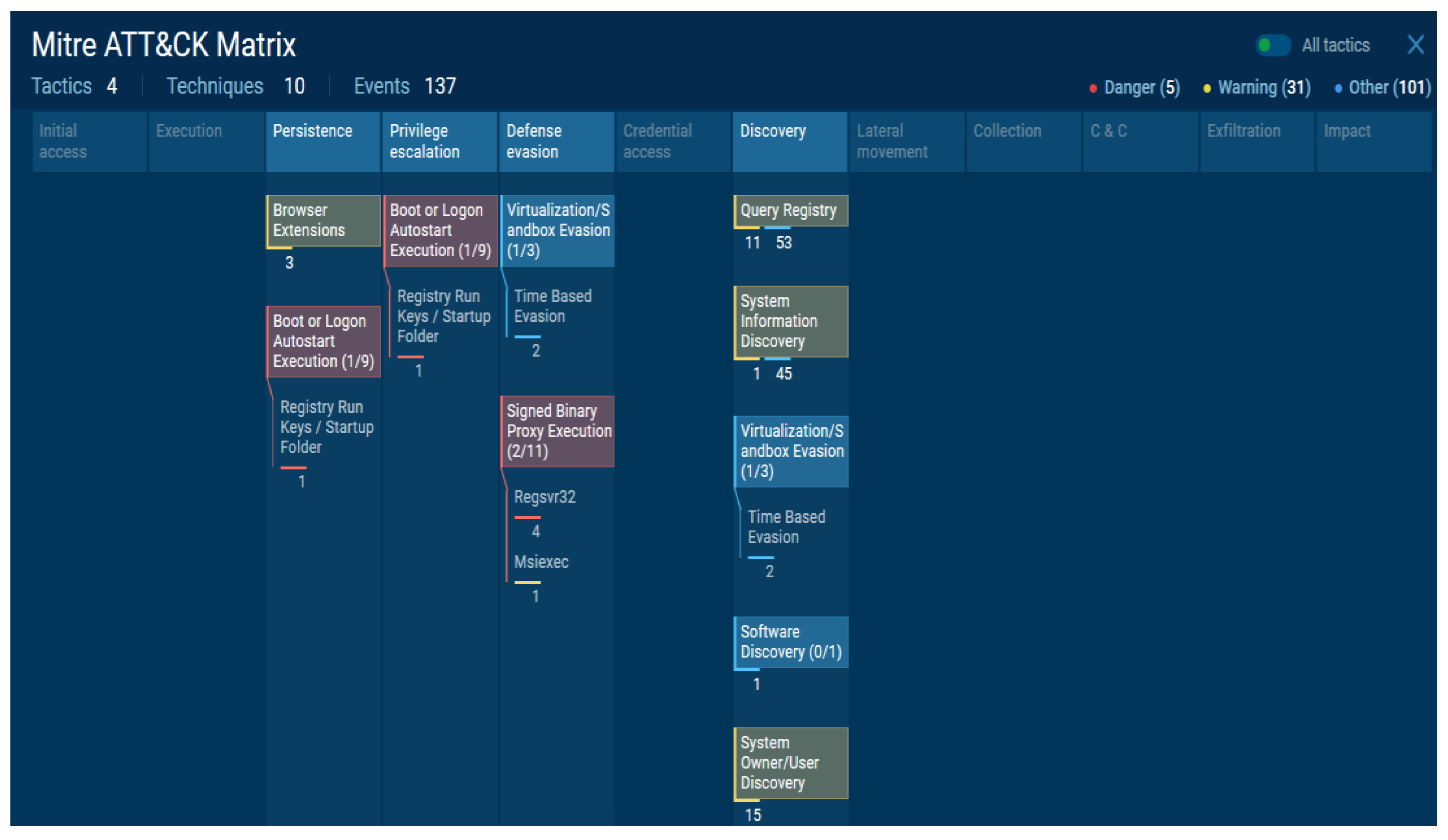

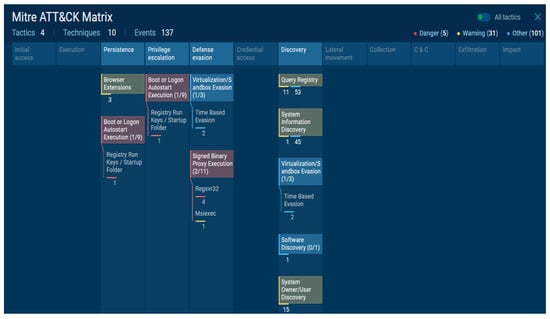

By mapping the dynamic analysis result file to TTP and the MITRE ATT&CK framework, we successfully visualized the data results for the attacker’s attack form. The tactics of the suspicious files corresponded to five categories: execution, persistence, privilege escalation, defense evasion, and discovery. The data and risk for 10 techniques and 43 events were measured as one danger, warnings, and three other cases.

One danger case was detected using the boot or logon autostart execution technique as a result of the technique details of persistence and privilege escalation tactics. The detection result of 39 warnings was obtained using the execution tactics’ Windows management instrumentation and MITRE’s command and scripting interpreter attack technology. The XSL script processing, file and directory permissions modification, and hide artifacts attack techniques of defense evasion tactics were detected. In the discovery tactics, it was detected that the query registry, system information discovery, and software discovery attack techniques were used, and the visualization of all the detected data results is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Implementation of MITRE ATT&CK framework and visualization of malicious file dynamic analysis results (1).

To verify the results of this study, an experiment was conducted by preparing data for a total of 51,960 files, comprising 2583 normal files, 49,376 malicious files, and 1 unknown file. The results of the experiment showed accurate detection results for normal/malignant files, and the results were successfully derived by conducting a dynamic analysis of suspicious files.

The results were mapped to the MITRE ATT&CK framework, and the attacker’s attack intention, form, and characteristics were successfully visualized. Figure 15 shows the results of the implementation, where only the detected range can be viewed, and the administrator can easily identify the attacker’s attack type.

Figure 15.

Implementation of MITRE ATT&CK framework visualization of malicious file dynamic analysis results (2).

5. Comparison

In this section, the malicious file detection visualization method by applying the machine learning algorithm proposed in this paper and the ATT&CK framework is compared with the previously studied machine-learning-based malicious file detection method. Table 10 briefly compares the previously studied machine-learning-based malicious file detection method with the detection method and visualization content proposed in this paper. Seungoh Choi et al. [35] proposed the ATT&CK framework.

Table 10.

Comparison of malicious file detection method using machine learning research cases.

Kris Oosthoek et al. [36] proposed building a test bed for collecting tactical and technical analysis and elastic-based control system security datasets. Although MITRE ATT&CK, which is the same method as that used in this paper, is used, it is a study based on simple collection and monitoring in terms of security control, and it is not possible to properly check how it can be visualized through actual malicious files. Additionally, in terms of security control, there is no way to minimize false positives and false positives, so it is difficult to understand them. In AMIR AFIANIAN et al.’s [37] study, we observed an increasing number of techniques applied to sideload DLLs to evade fileless malware execution, security software detection, and defense within our dataset, and more sophisticated techniques, including command and control (C&C), were observed. These observations have identified ways in which malware authors are innovating technologies to circumvent traditional defenses. The difference in our study is that through the application of the MITRE ATT&CK framework, it is possible to precisely analyze malicious, normal, and unknown malicious codes included in the dataset and provide a visual part that accurately detects the person in charge. Sanjay Sharma, C. et al. [38] appear to have used a sandbox to investigate technologies that can be analyzed manually and automatically. However, there is no visible method for specific analysis, results, and detection. Since this is research that can provide even the visualization part, we are conducting research that starts with dynamic analysis and visualizes the hybrid analysis method. Yanjie Zhao. et al.’s [39] paper seems to have studied the impact of sample replication on machine-learning-based Android malware detection. However, compared to our thesis, the classification of malicious code was excellent, but the analysis process was insufficient, and there seems to be no content on the visualization method. Judging from the use of in-the-wild analysis, it is an experimental study conducted using both supervised and unsupervised learning approaches and using various machine learning algorithms.

6. User Perspective

MITRE ATT&CK is an abbreviation of Adversarial Tactics, Techniques, and Common Knowledge. After observing actual cyberattack cases, the malicious behaviors used by attackers are analyzed from the viewpoint of attack methods (tactics) and technologies (techniques). These are standard data that classify and list information on the attack methods of the attack group. It is a systematization (patterning) of threatening tactics and technologies to improve the detection of advanced attacks. Originally, ATT&CK was used for hacking attacks used in Windows corporate network environments at MITER. It started with documenting TTPs such as (procedures), and is a framework that can identify the attacker’s behavior by mapping TTPs’ information based on the analysis of consistent attack behavior patterns generated by the attacker. Machine learning algorithms are used as a means to enhance and respond, and in conjunction with this, it can develop into an intelligent, advanced security control solution that provides real-time visualization to security personnel.

From the user’s point of view (security personnel), it is an excellent security solution and has the advantage of efficiently detecting attacks as it can minimize false positives and false positives for attack detection. In addition, since it provides real-time detected attack patterns and detailed information (techniques, tactics, various attack knowledge and attacker information, etc.), it is an all-round excellent solution for effective countermeasures and follow-up management

7. Conclusions

In this study, the detection accuracy was improved by utilizing the advantages of dynamic-analysis-based malicious file detection. In addition, it was possible to detect and analyze unknown files, which is expected to increase the analysis reliability and secure excellent field connectivity.

This was accomplished by deriving high accuracy standards for the Random Forest, AdaBoost, and Gradient algorithms, and synthesizing the formulas of research cases. To verify the results, the PE malicious file dataset was analyzed, experimental data were generated, and an experiment was conducted.

In addition, to perform dynamic analysis, normal, suspicious, and malicious codes were analyzed using the app.any.run program, and the results were mapped to the MITRE ATT&CK framework to visualize the attacker’s form and characteristics, easily identifying their attack intention. Therefore, users could easily identify malicious and normal files and respond quickly.

Future studies plan to use the introduced hybrid approach to overcome the limitations of dynamic and static analysis techniques. The hybrid method can overcome the disadvantages of both static analysis and dynamic analysis, and the ability to accurately detect malicious code and the speed at which this is carried out are improved. At the same time, it has the great advantage of being able to efficiently analyze suspicious files and having a low false-positive rate upon detection. In addition, we will continuously collect and analyze attack datasets, and we will also experiment with ways to apply linear regression, GLM, SVR, and GPR algorithms. Additionally, deep learning algorithms will explore ways to apply deep neural networks. In the future, we plan to conduct research to improve the speed of numerical accuracy by experimenting with a hybrid method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A., W.P. and D.S.; methodology, G.A., W.P. and D.S.; software, G.A. and W.P.; validation, K.K., W.P. and D.S.; formal analysis, G.A.; investigation, G.A.; resources, G.A. and W.P; data curation, G.A., K.K., W.P. and D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A.; writing—review and editing, K.K., W.P. and D.S.; visualization, G.A.; supervision, K.K., W.P. and D.S.; project administration, D.S.; funding acquisition, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Future Challenge Defense Technology Research and Development Project (9129156) hosted by the Agency for Defense Development Institute in 2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Hamar, Y.; Kolivand, H.; Tajdini, M.; Saba, T.; Ramachandran, V. Enterprise Credential Spear-phishing attack detection. J. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 94, 107363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine Learning and deep learning. Electron Mark. 2021, 31, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, G.S.; Mustafa, M.; Ponnusamy, R.; Abdufattokhov, S. Machine Learning Algorithms in Intrusion Detection and Classification. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 12211–12219. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, D.; Zhang, S. Machine Learning Model for Sales Forecasting by Using XGBoost. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICCECE), Guangzhou, China, 15 January 2021; pp. 480–483. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.; Kim, S.; Song, J.; Kim, K. Study on Machine Learning Techniques for Malware Classification and Detection. Korea Internet Inf. Soc. 2021, 15, 4308–4325. [Google Scholar]

- Kyoung-Hee, K.; Hyuck-Jin, P. Study on the Effect of Training Data Sampling Strategy on the Accuracy of the Landslide Susceptibility Analysis Using Random Forest Method. Korean Soc. Econ. Environ. Geol. 2019, 52, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.; Kumar, H.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Machine Learning in Wavelet Domain for Electromagnetic Emission Based Malware Analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2021, 16, 3426–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Fan, H.; Zhu, H.; You, C.; Zhou, H.; Huang, X. Intrusion detection system combined enhanced random forest with SMOTE algorithm. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2022, 39, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Nguyen, M.D.; Nguyen-Thoi, T.; Ho, L.S.; Koopialipoor, M.; Quoc, N.K.; Armahani, D.J.; van Le, H. A novel approach for classification of soils based on laboratory tests using Adaboost, Tree and ANN modeling. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 27, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, R.S.; Hussein, A.S.; ALRikabi, H.T.H.S. The Detection of Counterfeit Banknotes Using Ensemble Learning Techniques of AdaBoost and Voting. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2021, 14, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galen, C.; Steele, R. Empirical Measurement of Performance Maintenance of Gradient Boosted Decision Tree Models for Malware Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICALLC), Jeju Island, Korea, 13 April 2021; pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspersky. Machine Learning for Malware Detection. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pinhero, A.; Anupama, M.L.; Vinod, P.; Visaggio, C.A.; Aneesh, N.; Abhijith, S.; AnanthaKrishnan, S. Malware detection employed by visualization and deep neural network. Comput. Secur. 2021, 105, 102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J. Malware Detection in Executables Using Neural Networks. Tech. Blogs 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Yeom, S.; Oh, H.; Shin, D.; Shin, D. A Study on Malicious Code Identification System Using Static Analysis-Based Machine Learning Technique. J. Inf. Secur. Soc. Korea Inf. Secur. Assoc. 2019, 29, 775–784. [Google Scholar]

- Byeon, E.; Son, H.; Moon, S.; Jang, W.; Park, B.; Kim, Y. Constructing A Visualization & Reusable Metrics based on Static/Dynamic Analysis. In Proceedings of the Korea Information Processing Society Conference; Korea Information Processing Society: Seoul, Korea, 2017; Volume 24, pp. 621–624. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R.S.; Festijo, E.D. Generating Features of Windows Portable Executable Files for Static Analysis using Portable Executable Reader Module (PEFile). In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference of Computer and Informatics Engineering (IC2IE), Depok, Indonesia, 27 December 2021; pp. 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dudeja, H.; Modi, C. Runtime Program Semantics Based Malware Detection in Virtual Machines of Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Processing (ICInPro 2021), Bangalore, India, 1 January 2022; Volume 1483, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mimura, M. Evaluation of printable character-based malicious PE file-detection method. Internet Things 2021, 19, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Lal, R. Opcode-Based Android Malware Detection Using Machine Learning Techniques. Int. Res. J. Innov. Eng. Technol. 2021, 5, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Alshammari, A.; Aldrbi, A. Apply machine learning techniques to detect malicious network traffic in cloud computing. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ahamed, J.; Kadry, S.; Ramasamy, L.K. Detection malicious URLs using binary classification through adaboost algorithm. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2020, 10, 997–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, T.; Manavi, F.; Hamzeh, A. A PE header-based method for malware detection using clustering and deep embedding techniques. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 60, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lv, Q.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Sun, D.; Qiao, Y. A novel deep framework for dynamic malware detection based on API sequence intrinsic features. Comput. Secur. 2022, 116, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgulu, A.; Gulmez, S.; Sogukpinar, I. Sequential opcode embedding-based malware detection method. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 98, 107703. [Google Scholar]

- Bensaoud, A.; Kalita, J. Deep multi-task learning for malware image classification. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2022, 64, 103057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggle. “Malware-Exploratory-LeandroSouza”.

- Ahmadi, M.; Ulyanov, D.; Semenov, S.; Trofimov, M.; Giacinto, G. Novel Feature Extraction, Selection and Fusion for Effective Malware Family Classification. In Proceedings of the Sixth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, New York, NY, USA, 9–11 March 2016; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, J.; Hahsler, M.; Moore, T. Polymorphic malware detection using sequence classification methods and ensembles. EURASIP J. Inf. Secur. 2017, 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MITRE. MITRE ATT&CK. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.; Bae, S.; Lee, T. MITRE ATT&CK and Anomaly detection based abnormal attack detection technology research. J. Converg. Secur. Korea Converg. Secur. J. 2021, 21, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, I.S.; Cho, E.-S. iRF: Integrated Red Team Framework for Large-Scale Cyber Defence Exercise. J. Inf. Secur. Soc. 2021, 31, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.-H.; Jung, J.-W.; Lee, S.-W. Multi-perspective APT Attack Risk Assessment Framework using Risk-Aware Proble Domain Ontology. In Proceedings of the IEEE 29th International Requirements Engineering Conference Workshops, Notre Dame, IN, USA, 20–24 September 2021; pp. 400–405. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.W.; Oh, S.T.; Yoon, Y. Modeling and Selecting Optimal Features for Machine Larning Based Detections of Android Malwares. KIPS Trans. Softw. Data Eng. 2019, 8, 427–432. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Choi, J.; Yun, J.; Min, B.; Kim, H. Expansion of ICS Testbed for Security Validation based on MITRE ATT&CK Techniques. In Proceedings of the CSET20 Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Conference on Cyber Security Experimentation and Test, Daejeon, Korea, 12–14 August 2020; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Oosthoek, K.; Doerr, C. SoK: ATT&CK Techniques and Trends in Windows Malware. In International Conference on Security and Privacy in Communication Systems; Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 304. [Google Scholar]

- Afianian, A.; Niksefat, S.; Sadeghiyan, B.; Baptiste, D. Malware Dynamic Analysis Evasion Techniques: A Survey. ACM Trans. 2018, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Krishna, C.R.; Sahay, S.K. Detection of Advanced Malware by Machine Learning Techniques. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 742, pp. 332–342. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Cai, H.; Bissyandé, T.F.; Klein, J.; Grundy, J. On the Impact of Sample Duplication in Machine-Learning-Based Android Malware Detection. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2021, 30, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).