Abstract

In recent decades, haze has become an environmental issue due to its effects on human health. It also reduces visibility and degrades the performance of computer vision algorithms in autonomous driving applications, which may jeopardize car driving safety. Therefore, it is extremely important to instantly remove the haze effect on an image. The purpose of this study is to leverage useful modules to achieve a lightweight and real-time image-dehazing model. Based on the U-Net architecture, this study integrates four modules, including an image pre-processing block, inception-like blocks, spatial pyramid pooling blocks, and attention gates. The original attention gate was revised to fit the field of image dehazing and consider different color spaces to retain the advantages of each color space. Furthermore, using an ablation study and a quantitative evaluation, the advantages of using these modules were illustrated. Through existing indoor and outdoor test datasets, the proposed method shows outstanding dehazing quality and an efficient execution time compared to other state-of-the-art methods. This study demonstrates that the proposed model can improve dehazing quality, keep the model lightweight, and obtain pleasing dehazing results. A comparison to existing methods using the RESIDE SOTS dataset revealed that the proposed model improves the SSIM and PSNR metrics by at least 5–10%.

1. Introduction

Low-visibility environments have a significant influence on vision-based autonomous driving systems. For example, haze can cause serious damage to image quality, including color and brightness deviations that lead to numerous visual information losses. Consequently, the performance of computer vision algorithms, such as object detection, semantic segmentation, and visual simultaneous localization and mapping (visual SLAM), are degraded, and the safety of autonomous car driving that relies heavily on the above-mentioned algorithms is jeopardized accordingly. To preserve the performance quality of these vision-based algorithms, the images obtained by cameras require preprocessing before feeding to these functional processes.

The main cause of haze is the scattering of atmospheric particles. Gui et al. [1] divided image-dehazing methods into two categories depending on whether an atmospheric scattering model (ASM) [2] is used. Tan [3] mentioned that single-image dehazing using an ASM may face an ill-posed problem due to the availability of the transmission map and atmospheric light. Therefore, statistical experience is required to obtain a reasonable assumption called the prior, such that the ASM-based approach can be applied to a single-image dehazing problem. He et al. [4] obtained the dark channel prior (DCP) from large numbers of outdoor images by statistical methods. This is because the dark channel value of the haze-free outdoor image captured during daytime is close to zero, except for the sky and white areas. Other priors were also proposed in the literature. Zhu et al. [5] found that the difference between brightness and saturation is proportional to the depth, which is the so-called color attenuation prior (CAP). The haze-line prior [6] is based on the observation that the pixel values of a hazy image can be modeled as lines in the RGB space with atmospheric light as the origin. The distance from the origin of the same haze line is affected by the transmission map. Ju et al. [7] added an absorption function to the ASM and solved the image dehazing problem with the gray-world assumption. Based on DCP, Yang et al. [8] improved the estimation method of atmospheric light to avoid mistaking the sky region as containing haze and smoothed the transmission map with two morphological operators, namely, dilation and erosion.

The recent development of graphics processing units (GPUs), which deliver extraordinary acceleration in workloads involving artificial intelligence and machine learning, leads to an alternative dehazing approach based on these related technologies and becomes a research hotspot without using the ASM. Deep learning methods can be divided into supervised and unsupervised learning methods. The method based on supervised learning requires both hazy and ground truth images as inputs to a specially designed convolutional neural network (CNN) and trains a dehazing network using an appropriate loss function and backpropagation. Since the transmission map and atmospheric light are required when using the ASM approach, Cai et al. [9] set the atmospheric light to 1 and constructed a network structure called DehazeNet to estimate the transmission map. However, because the atmospheric light is defined in advance, the result of image dehazing is poor. Li et al. [10] integrated the transmission map and atmospheric light into a function as the learning target of the proposed AOD-Net. Furthermore, Yang et al. [8] redesigned the network architecture of AOD-Net [10], inheriting the advantages of few trainable parameters and real-time capabilities. Based on the idea of integrating the transmission map and atmospheric light as the learning target, Zhang et al. [11] designed a multi-scale network architecture using convolution and pooling. Qin et al. [12] concatenated two attention mechanisms to FFA-Net: channel attention and pixel attention. These mechanisms result in a greater weight in the blurred region, but the number of trainable parameters is too large. Liu et al. [13] proposed a generic model-agnostic CNN that is composed of an encoder and decoder associated with residual blocks, and the whole network can be trained end-to-end which means that no physical knowledge should be obtained in advance. It is worth mentioning that this network architecture can be applied to other tasks in addition to image dehazing.

The classic method based on unsupervised learning for the image dehazing problem involves the use of generative adversarial nets (GAN). The discriminator is used to determine authenticity, and the generator and the discriminator are trained separately through backpropagation. Engin et al. [14] imported cyclic perceptual consistency loss into CycleGAN [15] to improve the quality of image dehazing, but it cannot recover color deviation and object edge well. Qu et al. [16] proposed a two-scale generator and discriminator, and an enhancer with a multi-scale average pooling architecture has been constructed to provide more different receptive fields. In heavily hazy scenes, there is still room for improvement; therefore, it is necessary to apply more enhancing blocks to enhanced Pix2pix [16]. Mehta et al. [17] modified CycleGAN [15] and conditional GAN [18] to formulate their image-dehazing model. The proposed model of [17] outperforms the aforementioned GANs, but it may generate unnatural colors for some scenes. However, GANs are difficult to train efficiently because the generator and the discriminator are hard to converge at the same time. In general, the model sizes of image-dehazing GANs are comparatively large, which has a significant impact on execution time.

In practical applications, the image-dehazing algorithm belongs to the pre-processing part for autonomous driving systems; thus, while improving the quality of image dehazing, it is also necessary to consider the execution time and size of the trainable parameters. This paper proposes a lightweight CNN containing an attention gate, an inception-like block, and a spatial pyramid pooling (SPP) block with an appropriate loss function to achieve better image-dehazing quality. Finally, using an existing dataset, comparisons between other state-of-the-art and proposed image-dehazing algorithms based on image-dehazing quality, trainable parameters, and the average execution time per image are presented. In conclusion, the main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- It provides a real-time and lightweight end-to-end image-dehazing CNN model that restores the blur caused by the haze environment without intermediate component computation for ASM and knowledge of the physical model.

- Before feeding hazy images to the CNN, an image pre-processing block was used to map normalized RGB images to different color spaces. The image pre-processing block increases the number of layers of feature maps such that the image-dehazing CNN can extract features effectively.

- The inception-like block uses two convolutions to replace one convolution, which effectively increases the receptive field. The SPP block utilizes different pooling kernel sizes to extract feature values and to generate more feature maps. The proposed attention gate can smartly pay more attention to unclear structures, such as buildings and pedestrians.

- Through an ablation study and a quantitative evaluation, this study demonstrates the advantages of using the image pre-processing block, the inception-like block, the spatial pooling blocks, and the proposed attention gate.

- The number of trainable parameters of the image-dehazing CNN is 207.3 K, the model size is 0.86 MB, and the average execution time per frame under GPU acceleration is 0.018 s, which is equivalent to 55.56 fps.

- RESIDE-SOTS and RESIDE-HSTS were used as the testing image-dehazing-quality datasets, which improved the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity (SSIM) compared to other state-of-the-art image-dehazing methods.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Atmospheric Scattering Model

In the field of computer vision, atmospheric scattering models are often used to describe the formation formula for hazy images, as shown in Equation (1).

where is the pixel position, is the hazy image, is the clear image, is the global atmospheric light, and is the transmission map described by Equation (2). is called direct attenuation, and is called airlight.

where is the scattering coefficient of the atmosphere and is the distance between the camera and the observed objects. According to Equation (2), the larger the distance, , the lower the transmittance. From the direct attenuation term, J(x)t(x), a clear image becomes blurred and unclear for a larger due to the atmospheric light, which makes the image brighter and whiter.

The single-image dehazing problem is an ill-posed problem because it requires both global atmospheric light and transmission maps to be obtained simultaneously. Therefore, statistical methods for obtaining empirical rules are necessary for model-based approaches.

2.2. Deep-Learning-Based Method

Using U-Net [19] as the prototype of the image-dehazing network to carry out single-image dehazing is a common method. Its architecture includes an encoder and a decoder. The encoder is composed of several convolution filters and maximum pooling operations, while the decoder contains several convolution filters and transposed convolution filters to perform upsampling. In addition, before the decoder performs convolution, the feature map of the same resolution generated by the encoder and the transposed convolution result of the previous layer are directly concatenated and used as the convolution input.

U-Net [19] is mainly used to solve the problem of image segmentation. When using this architecture to solve the problem of image dehazing, it is not possible to simply deepen the number of network layers; but a suitable neural network block should be imported. For example, TheiaNet [20] imports the bottleneck enhancer into the final output of the encoder, which extracts the feature map from coarse to fine through multi-scale pooling to obtain different feature maps and then concatenates these feature maps together. The final output of the decoder is added to the aggregation head, and the outputs of the encoder and decoder of different layers are upsampled to the same resolution and concatenated.

2.3. Downsampling and Upsampling

Downsampling and upsampling reduce and enlarge the resolution of the original image, respectively, by a specified multiple. Downsampling often uses maximum pooling, a predefined operation, to improve the receptive field without increasing the computational complexity. Upsampling often uses predefined interpolation methods, such as nearest-neighbor interpolation and bilinear interpolation.

The advantage of predefined operations is that they save memory space, but the disadvantage is that CNN cannot learn its own sampling method. Therefore, convolution and transposed convolution can be adopted to allow the CNN to learn a suitable downsampling and upsampling process during the training process. For example, to reduce the image resolution to one-half of the original image, a convolution with a stride of two can be used instead of a max pooling with a stride of two, without sacrificing the values of the other feature maps. Similarly, to double the image resolution of the original image, a transposed convolution with a stride of two can be used instead of the interpolation method.

Additionally, when the kernel size cannot be divisible by stride, it causes a checkerboard effect due to the uneven overlapping. Therefore, kernel size and stride are applied to avoid generating a checkerboard-like pattern.

2.4. Multiple Input Channel

It can be observed from the ASM that the image is mainly blurred due to atmospheric light and particle scattering. Based on these phenomena, Ren et al. [21] proposed GFN, which inputs three different image processing methods, namely, white balance to deal with color deviation, contrast enhancement to increase the structure of objects, and gamma correction to solve dark regions. Then, they are concatenated to form a 9-channel input. The dehazing image is expressed by

where , , and , are confidence maps for the white-balanced image, , the contrast enhanced image, , and the gamma corrected image, , respectively, and is the Hadamard product.

In addition to image pre-processing, a multichannel input can also be mapped to different color spaces to increase the number of channels in the input image. Wan et al. [22] emphasized that the halo effect can be suppressed in the HSV color space. Tufail et al. [23] experimentally proved that better contrast and brightness can be obtained in the YCbCr color space. Therefore, inspired by [22,23], Mehra et al. [20] used a multi-cue color space, including RGB, HSV, YCbCr, and Lab, to formulate a 12-channel input.

The proposed method integrates the concepts of GFN [21] and TheiaNet [20] to preprocess hazy images. In the next section, we introduce significant blocks of our image-dehazing CNN, including the image pre-processing blocks, inception-like blocks, SPP blocks, and attention gates (AG).

3. Proposed Method

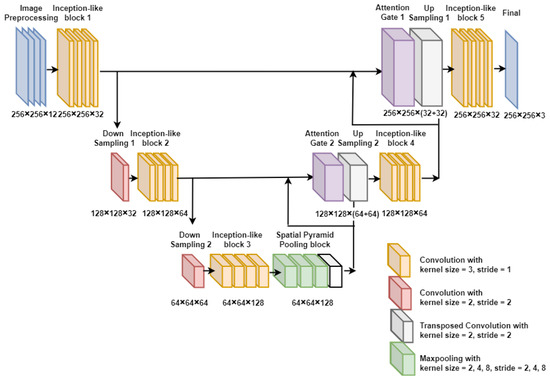

This section introduces details of the proposed image-dehazing CNN, as shown in Figure 1. First, the image preprocessing block performs image normalization and maps to different color spaces to form a 12-channel input. Subsequently, the inception-like block is used to increase the receptive field, and an SPP block is performed to increase the dimension of the feature map of high-level feature maps. The skip concatenation of U-Net [19] is replaced with an AG, which can adjust the gain of the feature map to leverage the blurry regions. Finally, an appropriate loss function for image dehazing is presented.

Figure 1.

The proposed image-dehazing CNN architecture.

3.1. Image Pre-Processing Block

Haze will make the overall image whiter, that is, three RGB channel values will concentrate on 255 for an 8-bit image and result in a blurred and unclear object structure. Therefore, a normalization procedure, as shown in Equation (4), is applied to stretch the original RGB value linearly and make the image clearer.

where is the input, is the spatial dimension, is the channel dimension referring to the RGB channels, and and denote the maximum and minimum values, respectively.

By mapping the normalized RGB image to HSV, YCbCr, and Lab, 12-channel images are formed. It is beneficial to improve the quality of image dehazing. The mapping operations to different color spaces only require simple mathematical operations without additional trainable parameters, thus saving storage space. Equation (5) denotes the output of the image preprocessing block.

where and are the dimensions of image height and width, respectively, and is the normalized image comprising 12 channels. RGB denotes red, green, and blue values. HSV denotes hue, saturation, and brightness values. YCbCr denotes the luminance, blue difference, and red difference. Lab denotes lightness, red/green values, and blue/yellow values.

3.2. Inception-like Block

Convolution was used to extract image features to form feature maps. These feature maps represent the high-dimensional images. Feature maps obtained through convolution filters usually go through nonlinear operators after convolution, such as a rectified linear unit (ReLU) or sigmoid function, to increase the nonlinear characteristics of the neural network.

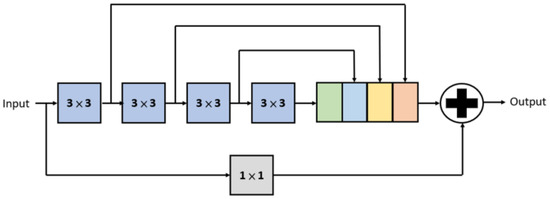

Szegedy et al. [24] proposed that the receptive fields of two convolutions are equivalent to the receptive field of one convolution. Similarly, the receptive fields of the three convolutions are equivalent to the receptive field of one convolution. One convolution is 5.44 () times more computationally expensive than one convolution, and three convolutions are 3 () times more computationally expensive than one convolution. Therefore, to increase the receptive field while also reducing the computational complexity, we use two convolutions instead of one convolution, and the same applies to and convolutions which inspired by MultiResUnet [25]. Figure 2 shows the overall inception-like block that includes four convolutions in series and one residual connection. The outputs of these convolutions are concatenated, and to increase the effectiveness of training, a convolution is added as the residual connection.

Figure 2.

An illustration of an inception-like block.

3.3. SPP Block

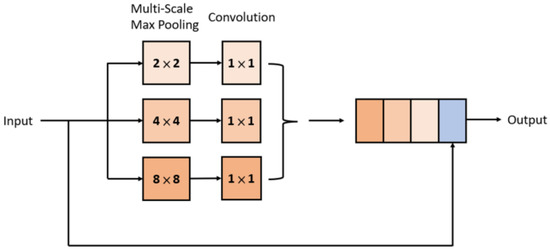

Maximum pooling was used to extract the obvious feature values in the feature maps. He et al. [26] used different pooling kernel sizes to extract feature values from the same feature map, from coarse to fine, to generate feature maps with different resolutions. In this way, without increasing the trainable parameters, it helps the shallower network obtain deeper network layers, thereby enhancing the effect of deep learning training. The SPP block in this study uses multi-scale maximum pooling with kernel sizes of , , and to extract features from coarse to fine. Because the resolution of the feature map shrinks after the maximum pooling, the results of each maximum pooling need to be upsampled by bilinear interpolation to the same resolution as the original feature map before they can be concatenated. Figure 3 shows the overall SPP block, which includes multiscale maximum pooling operations to extract features from coarse to fine.

Figure 3.

An illustration of an SPP block.

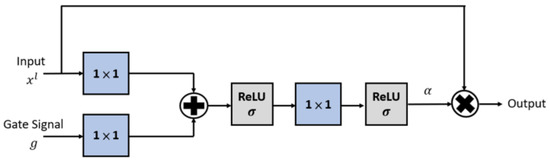

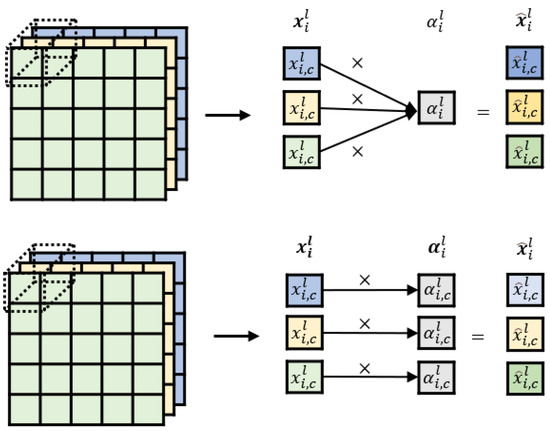

3.4. Attention Gate

The original U-Net feature fusion involves directly concatenating the output of the transposed convolution and the output of the encoder with the same resolution, while Oktay et al. [27] proposed Attention U-Net to replace the direct concatenation part with the attention gate; that is, the same spatial dimension of the feature maps needs to be multiplied by the same attention coefficient between 0 and 1, as in Equation (6). This attention mechanism is beneficial for automatically highlighting salient regions for semantic segmentation.

where is the spatial dimension, is the channel dimension, is the layer, is the input, is the attention coefficient, and is the output.

Due to different task orientations, to pay more attention to the unclear region of the hazy image, the values of the same spatial dimension are multiplied by different attention coefficients, as follows:

where is positive, which differs from Attention U-Net [27].

The details of the attention gate are shown in Figure 4, where the attention coefficients are used to pay more attention to the unclear region of the hazy image during backpropagation. The difference between the original attention coefficient and the proposed attention coefficient is shown in Figure 5, where the first half was proposed by Attention U-net [27] for semantic segmentation. The second half is proposed in this study for single-image dehazing. The attention coefficient is determined by the gate signal and the output of a certain layer of the encoder. The gate signal is the result of the transposed convolution of the decoder. For example, in Figure 1, the output of inception-like block 1 is the input of the attention gate, and inception-like block 4, after the transposed convolution, is the gate signal.

Figure 4.

An illustration of an attention gate.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of an attention gate with single and multiple attention coefficients.

The attention coefficient is calculated using Equation (8). The activation function adopts the ReLU function to ensure that the attention coefficient is greater than 0.

where is the input, is the ReLU function, , , is the number of channels in the input feature map, is the number of channels in output feature map, is the number of channels in the intermediate feature map, , and and are biases.

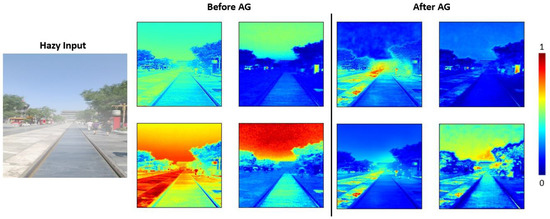

Figure 6 shows that the attention gate calls attention to objects of distant buildings, ground textures, trees, and pedestrians that are blurred due to haze. The feature map after the attention gate changes the gain by the attention coefficient to achieve the effect of focusing on objects with complex structures and suppressing objects with relatively simple structures, such as focusing on the characteristics of pedestrians and suppressing the characteristics of the sky.

Figure 6.

The effect of selecting four random feature maps before and after passing through AG 1.

3.5. Loss Function

The loss function setting of the image-dehazing CNN usually adopts the mean square error (MSE), as follows:

Treating MSE as a loss function means that only the difference in pixel values between the dehazing image and clear image is considered during training. The MSE is related to the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR).

where is the maximum possible pixel value. In the case of an 8-bit image, is 255.

Considering that using only MSE may lead to visible speckle artifacts, this study introduces the structural similarity (SSIM) to reveal the degree of similarity between dehazing and clear images, including luminance, contrast, and structure, which can improve the learning efficiency and quality of image dehazing. When the SSIM is closer to 1, the two images are more similar.

where , is the similarity of luminance, is the similarity of contrast, and is the similarity of structures. The details of , , and are as shown in Equation (12).

where and are the mean values of the signals and , respectively, and are the standard deviations of the signals and , and , , and are constant values.

In this study, the loss function is used in combination with the MSE and SSIM, as follows:

In addition to the pixel value difference between the image generated by the proposed network and the ground truth, the difference in the similarity between image patches is also considered.

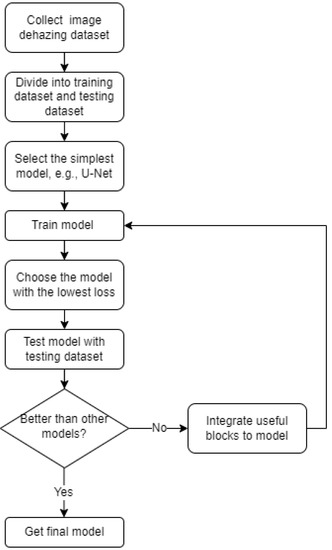

4. Experiments and Analysis

In this section, image-dehazing experiments are conducted. First, we determine the trainable parameters of the image-dehazing CNN. We then introduce the image-dehazing dataset used for training and testing the image-dehazing CNN. A comparison of the resulting performance with that of other state-of-the-art models by using the image quality metrics is provided. Figure 7 shows the workflow of the proposed-dehazing model generation.

Figure 7.

The workflow of the proposed dehazing-model generation.

4.1. Parameters of Neural Network

The input image specification of the dehazing CNN is after resizing the original image. An image pre-processing block is used to obtain a pre-processed image with 12 channels. The internal parameters of the proposed image-dehazing CNN are listed in Table 1, including five inception-like blocks, two attention gates, two downsamplings, and two upsamplings. The dehazing output image is an RGB image; therefore, there are three convolutions at the end of the neural network.

Table 1.

Parameters of proposed network.

The size of the trainable parameters of the proposed image-dehazing CNN affects the time required for training and inference speed. Although a larger number of trainable parameters can improve the image-dehazing quality, the number of trainable parameters should not be too large for real-time dehazing. Table 2 shows a comparison of the number of trainable parameters with the state-of-the-art model. Although FFA-Net [12] has outstanding dehazing quality, it has too many trainable parameters to meet a lightweight model and will not be applied in the proposed approach.

Table 2.

Comparison of trainable parameters.

4.2. Image-Dehazing Datasets

Constructing a large-scale real image-dehazing dataset is not easy because concurrently acquiring a hazy image and a haze-free image in the same place is not possible. Therefore, a large-scale dataset named RESIDE (REalistic Single-Image DEhazing) was proposed by Li et al. [29]. In RESIDE, data are presented as synthetic and real hazy images that correspond to clear images. The RESIDE Indoor Training Set (ITS) contains 1399 clear images, each of which contains 10 images with varying degrees of haze, for a total of 13,990 hazy images. The RESIDE Outdoor Training Set (OTS) contains 2061 clear images, and each clear image synthesizes 35 images with different degrees of haze to obtain a total of 72,135 hazy images. In addition, the testing dataset of RESIDE includes a synthetic objective testing set (SOTS) and a hybrid subjective testing set (HSTS).

In this study, RESIDE ITS and RESIDE OTS were used to train indoor and outdoor image-dehazing CNNs, while RESIDE SOTS and RESIDE HSTS were used to test the image-dehazing quality. The distribution of the dataset is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of the dataset.

4.3. Ablation Study

It is crucial to discuss the influence of each neural network block on the dehazing quality; therefore, we trained six different models to observe the performance of these blocks. Table 4 lists the details of the six models.

Table 4.

Description of ablation analysis.

Table 5 shows the dehazing quality metrics of the six models and their corresponding numbers of trainable parameters. From model 2 and model 3, the inception-like block and the pyramid pooling improve the dehazing quality. Model 4 shows that an attention gate can increase SSIM and PSNR without adding too many trainable parameters, and model 5 uses the image preprocessing block without adding trainable parameters. Model 6 uses the proposed attention gate instead of the original attention gate, resulting the best dehazing quality among these approaches.

Table 5.

Result of ablation analysis on RESIDE SOTS outdoor dataset.

4.4. Performance and Discussion

In the study, PyTorch was applied for developing the deep learning architecture with a central processing unit (CPU) of a 3.00 GHz Intel Core i5-8500 CPU. The GPU processor used a GeForce GTX 1660 Super 6G for training, the batch size was set to 8, and the loss function of Equation (13) was adopted. A learning rate of 0.0001 and 150 epochs were used for the Adam optimizer [30]. A total of 90% of the training dataset was used for training, and 10% was used for verification, which can be used to confirm the loss trend and ensure that the model does not overfit.

The image-dehazing CNN results were analyzed and compared using two metrics, namely, PSNR and SSIM, introduced in the previous section. Table 6 compares the image quality metrics of the different methods applied to the RESIDE SOTS indoor and outdoor testing datasets. The datasets contain images of various scenes with different haze concentrations. From Table 6, the proposed image-dehazing CNN leads to better results than the prior-based methods and learning-based methods that have been proposed in recent years. Compared to the latest approach, TheiaNet [20], the average SSIM of the indoor dehazing results increased by 5.65%, and the average PSNR increased by 7.73%, whereas the average SSIM of the outdoor dehazing results increased by 2.83%, and the average PSNR increased by 14.09%.

Table 6.

Comparison of dehazing results on RESIDE SOTS dataset.

Table 7 compares the image quality metrics of the different methods applied to the RESIDE HSTS testing dataset. Compared to TheiaNet [20], the average SSIM of the dehazing results increased by 2.47%, and the average PSNR increased by 8.09%.

Table 7.

Comparison of dehazing results on RESIDE HSTS dataset.

To estimate the average execution time per frame, 500 hazy images with the original resolution of were processed by the trained dehazing CNN. It only took 0.018 s per frame, on average, through the GPU, which fulfills the real-time application requirement, and it took only 0.24 s, on average, through the CPU. Table 8 and Table 9 compare the average execution time per frame of the dehazing models by ReViewNet [28] and TheiaNet [20]. Since DehazeNet [9] and AOD-Net [10] did not produce satisfactory dehazing quality, as listed in Table 6, the corresponding average execution times of both methods are not included in Table 8 and Table 9.

Table 8.

Comparison of average execution time per frame on CPU.

Table 9.

Comparison of average execution time per frame on GPU.

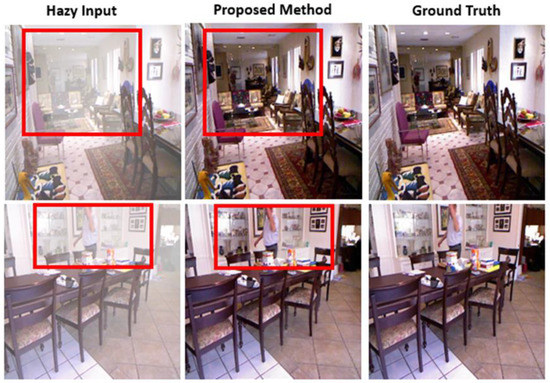

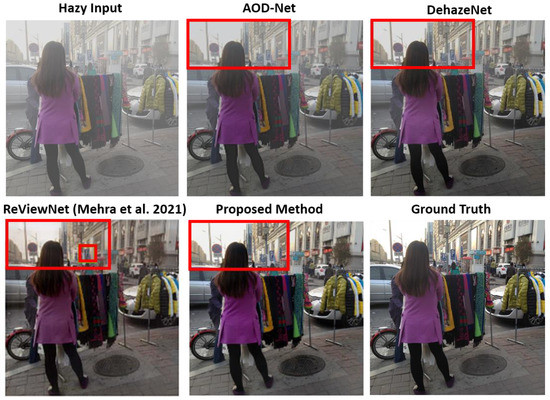

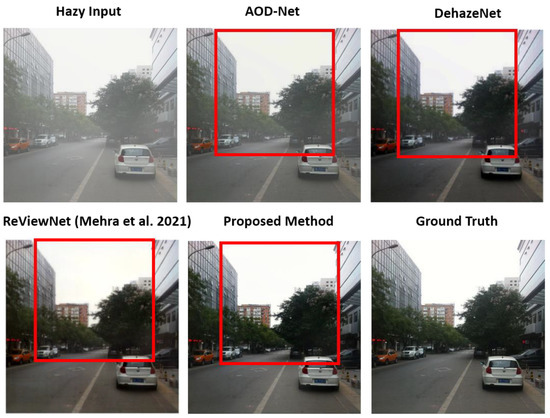

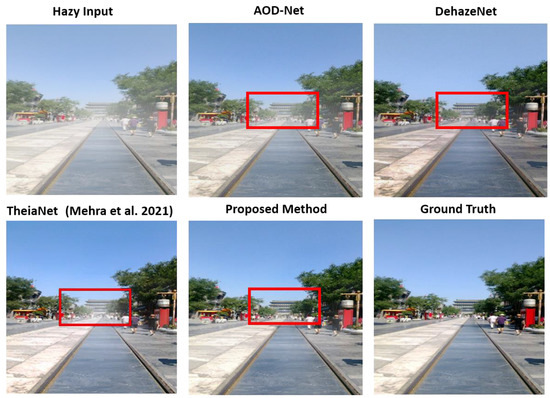

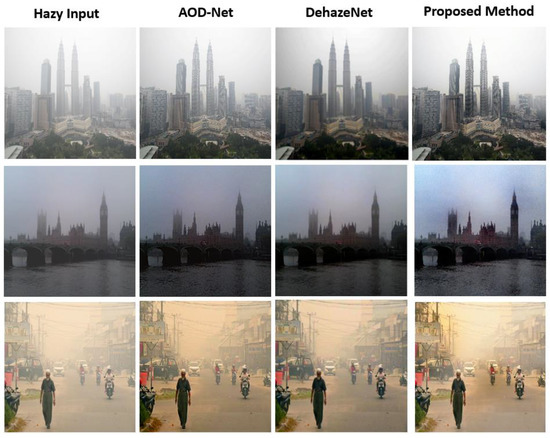

Some comparisons between the dehazing results of the RESIDE SOTS indoor and outdoor testing datasets and ground truth are demonstrated as follows. Figure 8 illustrates the indoor dehazing results. The box indicates the key recovery area where the image is not clear due to the haze. It can be seen from the results of the image dehazing that people and furniture in the distance were affected by color deviation and low contrast were well-restored and were almost the same as the ground truth. Similarly, Figure 9 shows the restoration of traffic signs, cars, and sky regions blurred by haze in the outdoor environment. AOD-Net [10] and DehazeNet [9] cannot recover the color deviation or the contrast well. ReViewNet [28] generates a darker image than ground truth and cannot restore the appearance of the no parking sign. The proposed method effectively removes the haze on buildings, sky, and traffic signs. The same dehazing effect was also achieved for images with buildings and trees, as shown in Figure 10. It shows that ReViewNet [28] generates a darker dehazing result due to a color deviation problem. As illustrated in Figure 11, removing haze for objects far in the distance is a limitation of TheiaNet [20]. Obviously, the proposed method generates a clearer dehazing result for distant buildings than the other models. For a real hazy image, the proposed method achieves a visually pleasing result compared to those of the other models, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 8.

Comparison of dehazing results from RESIDE SOTS indoor testing dataset with ground truth.

Figure 9.

Comparison of dehazing results of traffic signs, cars, and sky region [28].

Figure 10.

Comparison of dehazing results of urban road [28].

Figure 11.

Comparison of dehazing results of distant haze [20].

Figure 12.

Comparison of dehazing results of real hazy image.

5. Conclusions

The pros and cons of the image-dehazing methods in recent years as well as the proposed method are summarized as follows. The DCP and CAP dehazing methods based on statistical experience are training-free methods. They obtain a certain degree of image-dehazing quality, but the resulting quality is poor compared to other approaches. AOD-Net uses a simple CNN architecture to learn a function composed of the transmission map and atmospheric light. Although the model is lightweight, efforts are still required to improve its dehazing quality. Without requiring knowledge of the physical model, ReViewNet and TheiaNet use the U-Net architecture as a prototype and integrate the appropriate CNN blocks to produce quality dehazing images. However, the dehazing quality for objects far in the distance may become a drawback of using TheiaNet. Based on the U-Net architecture, the proposed approach integrates image preprocessing blocks, inception-like blocks, SPP blocks, and AGs to achieve a better image-dehazing quality, even for images with sky and objects far in the distance. For a real hazy image, it also produces clearer dehazing results. The proposed model can be considered as a lightweight and real-time model for dehazing applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-Y.T. and C.-L.C.; methodology, C.-Y.T. and C.-L.C.; software, C.-Y.T.; validation, C.-L.C.; formal analysis, C.-Y.T.; data curation, C.-Y.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-Y.T.; writing—review and editing, C.-L.C.; supervision, C.-L.C.; funding acquisition, C.-L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, under grant No. MOST 107-2221-E-006-119.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gui, J.; Cong, X.; Cao, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Tao, D. A Comprehensive Survey on Image Dehazing Based on Deep Learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.03323. [Google Scholar]

- Cozman, F.; Krotkov, E. Depth from scattering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Juan, PR, USA, 17–19 June 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, R.T. Visibility in bad weather from a single image. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Anchorage, AK, USA, 23–28 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, X. Single Image Haze Removal Using Dark Channel Prior. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011, 33, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Mai, J.; Shao, L. A Fast Single Image Haze Removal Algorithm Using Color Attenuation Prior. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2015, 24, 3522–3533. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, D.; Treibitz, T.; Avidan, S. Non-local Image Dehazing. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, M.; Ding, C.; Ren, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Guo, Y.J. IDE: Image Dehazing and Exposure Using an Enhanced Atmospheric Scattering Model. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2180–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Evans, A.N. Improved single image dehazing methods for resource-constrained platforms. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2021, 18, 2511–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Xu, X.; Jia, K.; Qing, C.; Tao, D. Dehazenet: An end-to-end system for single image haze removal. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2016, 25, 5187–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, D. AOD-Net: All-in-One Dehazing Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Tao, D. FAMED-Net: A fast and accurate multi-scale end-to-end dehazing network. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 29, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, X.; Wang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Xie, X.; Jia, H. FFA-Net: Feature fusion attention network for single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NJ, USA, 7–12 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Xiao, B.; Alrabeiah, M.; Wang, K.; Chen, J. Single Image Dehazing with a Generic Model-Agnostic Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2019, 26, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, D.; Genç, A.; Ekenel, H.K. Cycle-dehaze: Enhanced cyclegan for single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Xie, Y. Enhanced Pix2pix Dehazing Network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, A.; Sinha, H.; Narang, P.; Mandal, M. HIDeGan: A Hyperspectral-guided Image Dehazing GAN. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1411.1784. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 5–9 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, A.; Narang, P.; Mandal, M. TheiaNet: Towards fast and inexpensive CNN design choices for image dehazing. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2021, 77, 103137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Cao, X.; Liu, W.; Yang, M.-H. Gated fusion network for single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Chen, Q. Joint image dehazing and contrast enhancement using the HSV color space. In Proceedings of the 2015 Visual Communications and Image Processing (VCIP), Singapore, 13–16 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tufail, Z.; Khurshid, K.; Salman, A.; Nizami, I.F.; Khurshid, K.; Jeon, B. Improved Dark Channel Prior for Image Defogging Using RGB and YCbCr Color Space. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 32576–32587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ibtehaz, N.; Rahman, M.S. MultiResUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture for multimodal biomedical image segmentation. Neural Netw. 2020, 121, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, A.; Mandal, M.; Narang, P.; Chamola, V. ReViewNet: A Fast and Resource Optimized Network for Enabling Safe Autonomous Driving in Hazy Weather Conditions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 4256–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ren, W.; Fu, D.; Tao, D.; Feng, D.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Z. RESIDE: A Benchmark for Single Image Dehazing. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.04143. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).