Abstract

Mobile robots are no longer used exclusively in research laboratories and indoor controlled environments, but are now also used in dynamic industrial environments, including outdoor sites. Mining is one industry where robots and autonomous vehicles are increasingly used to increase the safety of the workers, as well as to augment the productivity, efficiency, and predictability of the processes. Since autonomous vehicles navigate inside tunnels in underground mines, this kind of navigation has different precision requirements than navigating in an open environment. When driving inside tunnels, it is not relevant to have accurate self-localization, but it is necessary for autonomous vehicles to be able to move safely through the tunnel and to make appropriate decisions at its intersections and access points in the tunnel. To address these needs, a topological navigation system for mining vehicles operating in tunnels is proposed and validated in this paper. This system was specially designed to be used by Load-Haul-Dump (LHD) vehicles, also known as scoop trams, operating in underground mines. In addition, a localization system, specifically designed to be used with the topological navigation system and its associated topological map, is also proposed. The proposed topological navigation and localization systems were validated using a commercial LHD during several months at a copper sub-level stoping mine located in the Coquimbo Region in the northern part of Chile. An important aspect to be addressed when working with heavy-duty machinery, such as LHDs, is the way in which automation systems are developed and tested. For this reason, the development and testing methodology, which includes the use of simulators, scale-models of LHDs, validation, and testing using a commercial LHD in test-fields, and its final validation in a mine, are described.

1. Introduction

The development of robotic applications has increased significantly in the last decade, and currently, robotic systems are being utilized for many purposes, in various environments. Mobile robots are no longer used exclusively in research laboratories and indoor controlled environments, but are now also used in dynamic industrial environments and outdoor sites. Moreover, the efforts for developing autonomous cars and drones have had the effect of strengthening the development and use of other autonomous machines and vehicles in various industries.

Mining is one industry in which autonomous vehicles have been in use for at least 13 years. Industrial use of autonomous hauling trucks started in 2008 in the Gabriela Mistral copper open-pit mine, located in the north of Chile. Currently, the use of autonomous mining equipment, mainly vehicles, is an important requirement in the whole mining industry. This is because mining operations need to increase the safety of the workers, as well as to augment the productivity, efficiency, and predictability of the processes. Safety is, without doubt, a key factor, and has been the top priority of mining companies in recent years. This is true, especially, in underground mining operations with their hazardous environments in which workers are constantly exposed to the risks of rock falls, rock bursts, and mud rushes, and where the presence of dust in the air can result in a number of associated occupational diseases in the workers [1].

In an underground mine, autonomous vehicles navigate inside tunnels. This kind of navigation has different precision requirements from those where they are navigating in an open environment. First, tunnels are GNSS-denied environments and thus vehicles cannot use any GNSSs (Global Navigation Satellite Systems) to self-localize. Secondly, when driving inside tunnels, it is not relevant to have an accurate localization system, but it is essential to be able to move safely through the tunnel, and to make appropriate decisions at its intersections and access points. This is completely different from most robotic applications, where safe navigation requires an accurate determination of the robot’s position and orientation at every moment.

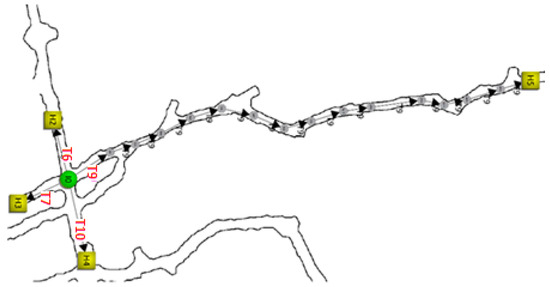

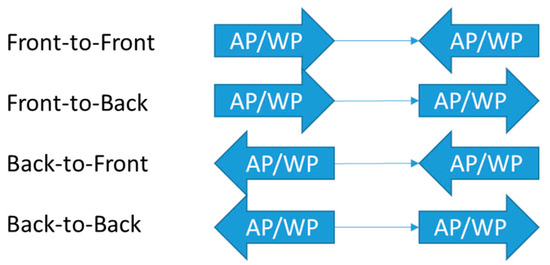

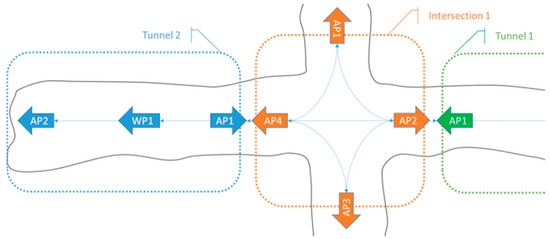

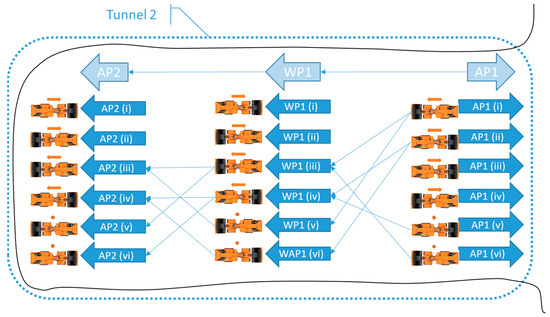

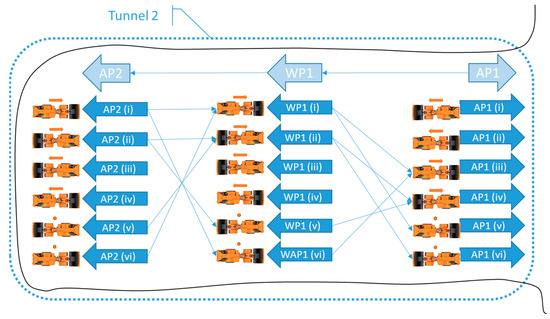

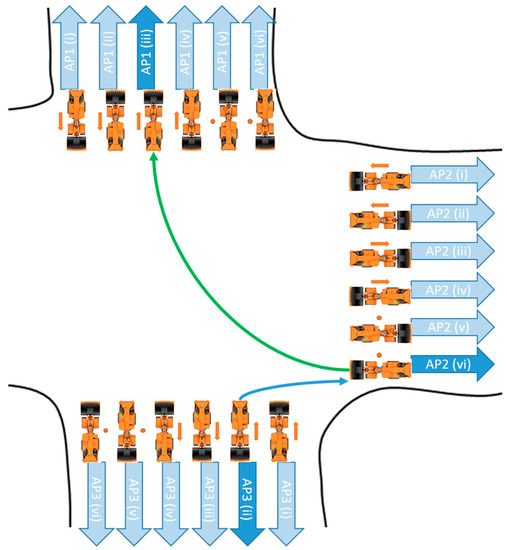

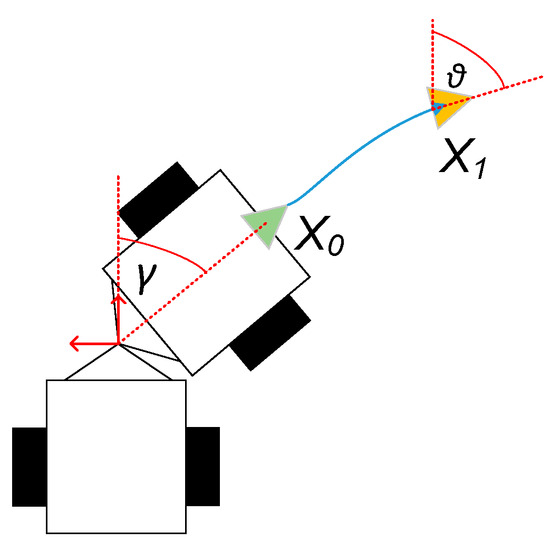

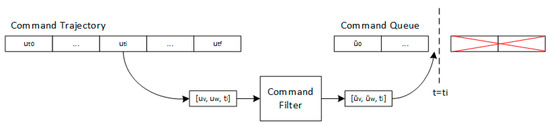

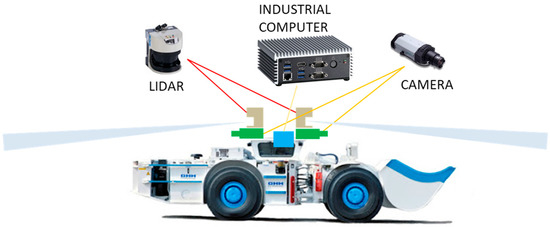

To address this need, a topological navigation system for mining vehicles operating in tunnels is proposed and validated in this paper. This system was specially designed to be used by Load-Haul-Dump (LHD) vehicles, also known as scoop trams, operating in underground mines. An LHD is a four-wheeled, center-articulated vehicle with a frontal bucket used to load and transport ore on the production levels of an underground mine (See Figure 1). These machines are a key component in the extraction of ore from underground mines because the ore extraction rate from the mine depends directly on the efficiency of the LHD. The proposed system permits a commercial LHD, which is a very large vehicle, to navigate inside tunnels that are just a couple of meters wider than the LHD. In addition, it allows bi-directional navigation and so-called inversion maneuvers, both required in standard LHD operations inside productive sectors of underground mines. (See an example in Figure 2). In addition, a localization system, specifically designed to be used with the topological navigation system and its associated topological map, is also proposed.

Figure 1.

LHD and sensors for the Autonomous Navigation System.

Figure 2.

Example of inversion maneuver.

An important aspect to be addressed when working with heavy-duty machinery, such as the LHDs, is the way in which automation systems are developed and tested. In order to address this important issue, we use a development process for autonomous systems for mining equipment, which is comprised of the following four-stages: (i) development using specific simulation tools, which are fed with real data from mining environments, (ii) development using scale-models of the actual machines, (iii) validation and testing using real machines in test-fields, and (iv) validation and testing using real machines in actual mine operations. This development process was used for achieving autonomous navigation of LHDs. The proposed topological navigation and location systems were validated using a commercial LHD, during several months at a medium-scale sub-level stoping mine, located in the Coquimbo Region of Chile.

The main contributions of this paper are the following:

- A topological navigation system for mining vehicles operating in tunnels, which can be used in any tunnel network by any articulated vehicle.

- A novel localization system specifically designed for tunnel-like environments, which estimates the vehicle’s global and local pose using the topological map.

- A development and testing methodology that can be used in the development process of heavy-duty machinery.

- Full-scale navigation experiments using a commercial LHD on a productive level of a sublevel stoping mine.

This paper is organized as follows: First, related work on autonomous LHD navigation is presented in Section 2. The proposed topological navigation system for LHD is described in Section 3. Then, in Section 4, the development and testing methodology is described, and in Section 5, validation results achieved in an actual mine are presented. Finally, conclusions of this work are drawn in Section 6.

2. Related Work

Autonomous navigation of LHDs has been a subject of scientific research since the late 1990s [2,3,4]. The main objectives have been to improve productivity and increase safety for the personnel, but simultaneously to benefit from reduced machine maintenance due to less wear of components. The theoretical development, and experimental evaluation, of a navigation system for an autonomous articulated vehicle is described in [4]. This system is based on the results obtained during extensive in-situ field trials and showed the relevance of wheel-slip for the navigation of center-articulated machines. In [5], one of the earlier industrial automation implementations is reviewed. It is mentioned there, that the use of automation in day-to-day operations offers flexibility and convenience for the operators. The development of what would become the first commercially available solutions for autonomous navigation of LHD machines followed shortly thereafter.

The work of Mäkelä [6] set the basis for the AutoMine software of the LHD manufacturer Sandvik, while the work of Duff, Roberts, and Corke [7,8,9] set a similar precedent for the software MINEGEM of Caterpillar. Only a few years later, the work by Marshall, Barfoot, and Larsson [10,11,12] configured what would become Scooptram Automation of the company Atlas Copco (now Epiroc). These companies have applied their automation solutions directly to their articulated vehicles [13]. Because of their commercial application, only the initial work on the development of the autonomous systems from LHD manufacturers is available in the literature. For instance, autonomous navigation from the manufacturer Sandvik is based on an absolute localization paradigm, i.e., it relies on odometry and detection of natural markers of the tunnel network [6]. Localization is achieved by taking a profile of the tunnel in a 5 [m] long section and comparing it to a known map. Caterpillar, on the other hand, initially based its system on mainly reactive techniques (wall following), in conjunction with a topological map with information about loading points, dump points, intersections, and other markers that are used in an opportunistic location scheme [9]. Finally, Epiroc made use of a hybrid navigation paradigm [11]. A set of behaviors was programmed under a fuzzy logic scheme to form the reactive part, while a higher level (deliberative) planner was used at intersections or open spaces.

Despite its success in delivering a product to market, research in autonomous navigation for underground tunnels continues to be a relevant topic. In [14], a review is given on the performance of automated LHDs in mining operations. It also mentions some issues and challenges that remain. The dynamic and highly variable nature of mining operations underlines the need for flexible and quickly deployable systems, features that earlier commercial solutions lacked [15,16]. These shortcomings are also known to LHD manufacturers, who continue to improve their systems [17].

Automation in mining is, most certainly, a widespread trend that has already shown corporate benefits, and it will continue to drive the modernization of the mining industry [18]. Cost, productivity, and safety are still the driving forces for investments in automated systems. Recent publications in the field also suggest the increasing interest of China in the application of automation technologies [19,20,21]. Particular attention has been paid to modeling, and control techniques.

The autonomous navigation system presented in this paper is based on topological navigation, and model predictive control (MPC). Underground mining environments have been shown to be suited for the extraction of features needed to build topological maps [22], and a mixture of topological and metric maps has been used successfully to map and navigate in large environments [23]. MPC has also been proven to perform well in the high-speed control of vehicles with nonlinear kinematics [24,25,26].

4. Development and Testing Methodology

The methodology used for the development and testing of the proposed navigation system consists of four steps. The first is the development of the automation system in a simulated environment, which is a safe and cost efficient platform for that purpose. The second is the use of scale models to verify the behaviors that are too complex or impractical to be tested on a simulated environment. The third is validation and testing in real equipment, using a safe location intended for that purpose. Fourth is the validation and testing in a real operation environment under controlled conditions before moving on to production. Details are discussed further in the following section.

4.1. Development in a Simulated Environment

The system was initially developed and tested in a simulated environment using Gazebo [29] and integrated with ROS [30]. At first, an underground scenario with wide tunnels and perfect self-localization, using the real position from the simulator, was used as a testing environment. When the system could perform reasonably well, the wide tunnels were substituted by realistic tunnels, using laser scans acquired in a real underground mine. The realistic tunnels were much narrower and had irregular shapes. Finally, when the challenges of the new scenario were solved, the system was tested with a functional self-localization module, and with other factors that added complexity, such as a simulation of the LHD’s controller, in order to validate all low-level communication and security schemes.

4.2. Development Using Scale Models

Not all of the functions of the system can be tested in a simulated environment, either because of the complexity of the problem, which makes the simulation approach impractical, or because not enough data is available to simulate certain interactions between the equipment and the environment. To address this issue, a scale model can be built in order to validate some of the design assumptions before implementing the solution on a commercial vehicle. The scale models need to have a certain similarity in the aspects related to the phenomena that needs to be validated. In the case described here, a 1:5 scale model was built based on a commercial 5 [yd3] LHD, shown in Figure 12, with an electric power train and hydraulic actuation for the steering and bucket movements, mimicking real equipment. A scaled-down ore extraction point was built, including ore from an actual mine. The scale model was used to perform navigation in the laboratory before installing the control system in the commercial LHD.

Figure 12.

1:5 scaled LHD built for testing and validation.

4.3. Validation in Test-Fields

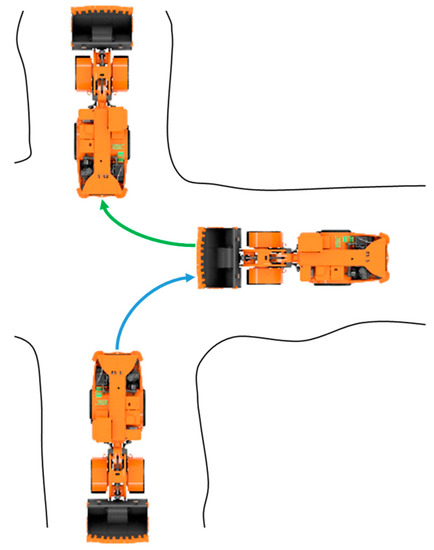

The LHD automation navigation was installed in a GHH’s LF11H LHD (GHH Fahrzeuge). The installation required mechanical and electrical modifications of the equipment to place the system’s sensors, processing units, and wireless communication equipment. All the automation software runs in an industrial fan-less computer equipped with an Intel i7 processor and with 4 logical cores. The interface between the automation and the machine was implemented on the machine controller (IFM mobile mini controller), based on GHH’s factory program (implemented in Codesys).

After the system was installed and all basic control, communications, and safety functions were thoroughly tested, the equipment was moved to a test-field nearby the OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) facilities in Santiago, Chile. The test-field emulated an underground tunnel by using light material to mimic the walls of the mine (Figure 13), which was enough to trick the system. It also had a dummy loading point, a dumping point, and a truck loading point. These tests were used to calibrate the system controller’s parameters and the kinematic characteristics of the vehicle’s model, such as the acceleration, steering, and breaking response to different operation inputs.

Figure 13.

Test-field close to GHH facilities in Santiago de Chile.

Because the test-field was located just outside the city where our development team is based (Santiago, Chile), it was possible to make a short trip to test new versions of the software, which contained bug fixes or improvements to the system. Usually a team of developers would go to the test-field two or three times a week to try out different modifications in the algorithms of the automation system.

The last milestone of this stage was to validate the reactive navigation algorithm. In order to do this in a safe manner, a hybrid operation mode was used, in which the speed of the LHD was remotely controlled by an operator while the autonomous navigation system handled the steering of the vehicle in an assisted tele-operation mode. To ensure safety precautions, an onboard operator who could shut down or override the automation system commands was on the vehicle for every test.

4.4. Validation in a Real Mining Operation

In order to carry out the final stages of development, the equipment had to be tested in its real operation environment, where the last design assumptions and algorithms needed to be validated, and the presence of personnel from the operation site were required.

In the case of the automation system described here, after test site validation, the LHD was transported to a real sublevel stopping mine in the north of Chile, where the development team, the OEM, and the mine personnel coordinated the final system validation and tests.

5. Results and Discussion

The validation in the test-field was executed from March to June of 2017, requiring approximately 300 h of work. On-site tests were carried out in a medium-scale sublevel stoping mining operation called the Mina 21 de Mayo (21st of May Mine), the property of Compañía Minera San Gerónimo, located in the north of Chile. The tests were comprised of two phases:

- During the first batch of tests in 2017, approximately 2300 work-hours were needed to test the system, of which about 800 were on-site; 600 were for remote support and system troubleshooting; 800 were with OEM remote support on-site; 100 h were spent traveling from the nearest city, La Serena, Chile, to the mine. The first batch included 66 days of testing, including installation of hardware on the LHD, network infrastructure on the tunnel, tele-operation station, and CCTV cameras. First underground tele-operation tests were done on day 32, which were followed by assisted tele-operation and self-localization tests.

- During the second batch of tests, performed in 2018, about 2900 work-hours were required, including 1000 on-site, 1000 with OEM support onsite, 750 with remote support, and 150 spent traveling from the nearest city to the mine. This second batch of tests lasted for 77 days. First, autonomous navigation tests took place on day 32. Further tests included approximately 150 h of autonomous navigation. It is important to note that the LHD was also used to test an autonomous loading system, so not all on site test were for the autonomous navigation system.

Between the first and second phases, several upgrades were made to the system in order to improve its robustness, consistency, and performance. The most important improvement was on the self-localization system, because the first batch of tests proved that the initial method (not described here) could not maintain the self-localization estimation along the test tunnel. Assisted tele-operation tests during the first phase were mainly used to tune the parameters of the Guidance module for the tunnel and intersection navigation modes (Equations (13), (14), (16), and (18)). Once the autonomous navigation was operating properly, further adjustments were made to all system’s parameters, including the parameters for the Command Executor module (Equations (20) and (21)). Parameters of the map were tuned, such as the maximum speed for certain segments of the tunnel, 2D poses of APs/WPs, and navigation modes for different parts of the tunnel.

On-site, at the mine, two validations were carried out: surface level tests, and underground tests. Surface level tests were done to test all the modules before entering the mine, and to visualize any problem that the LHD or the implemented automation system could have. After the arrival of the machine at the mine site, all sensors, antennas, and communication modules were re-installed and tested. The first teleoperation tests were carried out on the surface, on one of the dump sites of the mine, to verify that the operation of the LHD was correct.

The second validation was done inside the mine in a production tunnel. The system was tested incrementally from teleoperation to full autonomous operation. A network infrastructure was installed inside the test tunnel, and an operating station, consisting of a computer, screens, and controls, was installed inside the mine. Communication tests were carried out between the LHD inside the mine and the computer in the operation center. Teleoperation and assisted teleoperation modes were the first functionalities tested. In the first mode, the operator drives the equipment just as would be done aboard, and in the second mode the operator mainly indicates the direction of movement and the system keeps the LHD away from the walls keeping it from colliding with them. The system was successful in avoiding collisions between the equipment and the inner walls of the tunnel, and the general performance of the operation was similar to manual navigation.

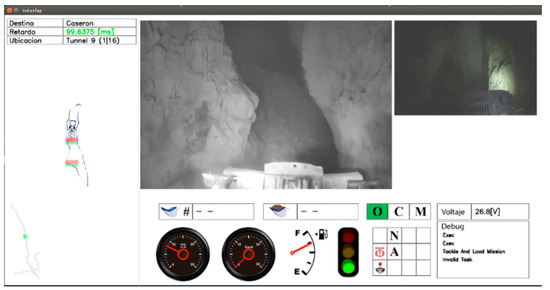

The autonomous navigation tests showed that the system allowed tramming along a 180 [m] tunnel from its entrance to the loading point. The LHD took approximately 2 [min] to go from one point to another, which is comparable to the performance achieved by an experienced human operator. Some of the difficulties that were found included the tunnel being too narrow for the LHD (sized according to the manufacturer’s specifications), and the floor having a large number of irregularities, pot holes, and varying inclinations. Of these factors, only the narrowness of the tunnel was included in the simulated environment. A view of the operator’s control interface is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Operator’s graphical interface of the navigation system.

Because of time constraints in the mine, testing, development and parameter tuning were done simultaneously. Because of this, most datasets of the tests in the mine are from a work-in-progress version of the navigation system. Results presented in this section are from 14 datasets (labeled 1, 2, 3, etc.), taken on a single afternoon two weeks before the end of on-site tests. 4 manual operation datasets (labeled M1, M2, M3, and M4) are also presented to have a reference for the performance of an experienced human LHD operator. These manual operation datasets were compiled a week later than the autonomous navigation datasets.

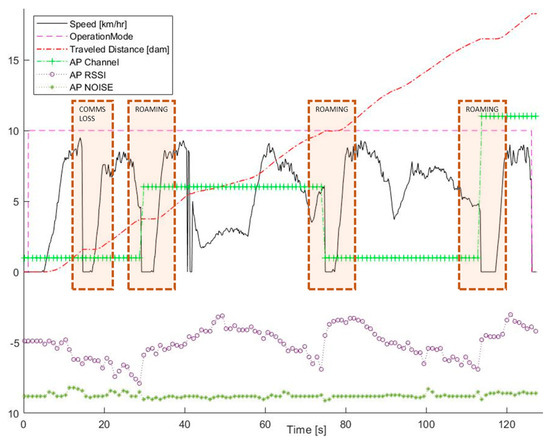

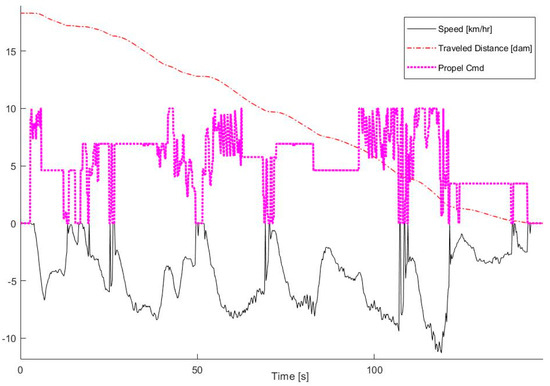

An important problem during tests was roaming between different Wi-Fi access points inside the tunnel. For safety reasons, the system stops accelerating the LHD if communication with the operation station becomes unstable, generating an emergency stop if the loss of communications is longer than a few seconds. Because of this, and a wireless network that did not have fast roaming capabilities, the system often stopped when switching from one access point to another. This can be seen in Figure 15, where stops produced by roaming, and by unstable communications, are shown. The Figure 15 also shows the instant speed of the vehicle (in km/h), the operation mode (with a value of 10 for autonomous navigation, 0 for idle, and −10 for tele-operation), distance traveled (in decameters), the Wi-Fi channel of the access point, at which the LHD is connected (different channels are used for faster roaming), and, finally, the RSSI and Noise values reported by the wireless modem of the vehicle. All the scales have been selected to fit in a single figure, to show the relation better between these variables.

Figure 15.

Instant speed, operation mode, distance traveled, wireless communication channel, RSSI, and noise for dataset 1. It can be seen in the selected areas that the LHD comes to a stop when switching between different access points, or when the communication network becomes unstable.

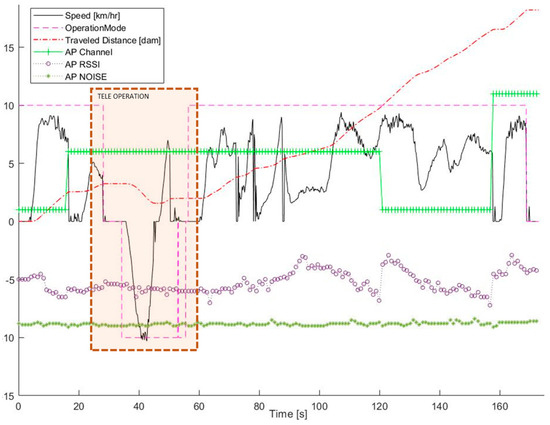

Another consideration for these datasets, since the navigation map was still being tuned, is the intervention of the operator through tele-operation (or assisted teleoperation) to help the LHD go through some narrow passages, or to get back and try again to pass autonomously through a given part of the tunnel. This is shown in Figure 16, as the vehicle needed to stop, then go back a couple of meters (with teleoperation assistance), to later reengage in the autonomous navigation mode, this time getting to the desired destination without further intervention.

Figure 16.

Instant speed, operation mode, distance traveled, and wireless communication channel for dataset 5.

Taking these factors (stops because of communication problems and tele-operation) into account, a series of performance indicators were computed for all the datasets. The mean and max speed of the LHD are presented in Table 3. When analyzing the results, it is important to consider that some datasets were compiled with the LHD having a fully loaded bucket, and others with an empty bucket. In some of these datasets, the LHD is moving forward, towards the draw point of the tunnel, and in others, it is moving backward, towards the dump point of the tunnel. To better understand the performance of the system, and the effects of roaming and tele-operation, other indicators are presented, such as the length of the dataset, the total distance of the movement, and the total distance that the LHD was driven by the autonomous system. With an empty bucket, the seasoned operator drove through the tunnel at an average speed of 6.4 [km/h], while the autonomous system did the same at 5.8 [km/h], thus slightly underperforming. The maximum speed achieved by the autonomous system was 11.3 [km/h] with a loaded bucket, while the seasoned operator achieved a maximum speed of 10.6 [km/h] with an empty bucket.

Table 3.

Mean Speed, Maximum Speed, Navigation Time, and Navigation Distance for autonomous navigation and manual operation datasets. ID: Dataset Identifier. T.Op Time: Tele-operation Time. TD: Total Distance. TAD: Total Autonomous Distance. E/L B: Empty or Loaded Bucket. H F/B: Heading Forward or Backwards.

The Navigation time is either an autonomous navigation time or a manual operation time, depending on the dataset. Stop time is the time the machine was stopped, which includes the time at the start and the end of each dataset. Tele-operation time is the amount of time spent tele-operating the LHD so that it is able to resume autonomous tele-operation, usually because the autonomous navigation system didn’t approach a curve appropriately, and reached a point where it didn’t know how to proceed. The LHD was able to go through the tunnel without remote assistance in only 6 datasets, but it is important to remember that these were done during development, and small tweaks and adjustments, some of them that worked and some of them did not, were made in between.

To further assess the driving abilities of the autonomous system, the smoothness of its operation is considered. For this, two different metrics are used. The first measures the change between two consecutive command inputs (propel and steering), as is shown in equation (22). The second, in a similar way, measures the difference between two consecutive measures of the dynamic state of the LHD, namely, its speed and the angle of its articulation, as is shown in Equation (23).

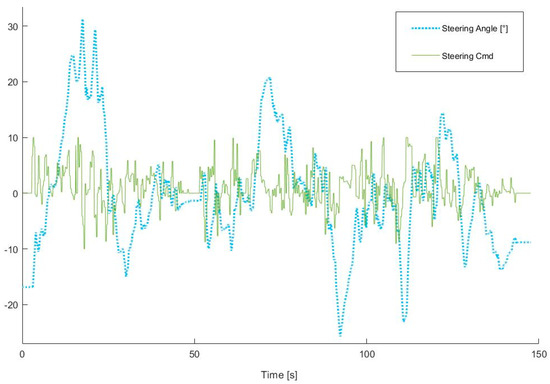

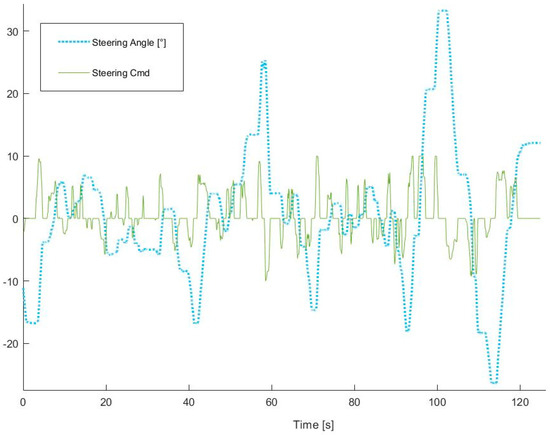

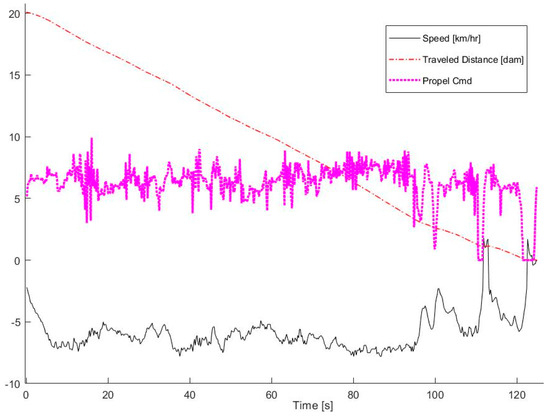

The average and maximum values of both metrics for all datasets are presented in Table 4. Again, the human operator shows a better performance than the autonomous system. The consistency of the human operator is quite remarkable, and it shows its expertise and knowledge of the machine and the tunnel. The autonomous system is also quite consistent on these metrics, but that is usually expected of an automation system. In order to have a better idea of the difference between them, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20 show the machine inputs (propel and steering) as well as the instant speed and steering angle of the LHD. Figure 17 and Figure 19 show dataset 14, while Figure 18 and Figure 20 show dataset M1. For clarity, Steering command and steering angle have been plotted separately from and propel command and LHD’s speed. Both were made with the LHD having a fully loaded bucket, and with the vehicle moving backward, towards the dump point of the tunnel. Straight lines can be seen in Figure 16 on the propel command line, showing a constant output by the autonomous system. Looking at both figures, it can be seen that the human operator uses fewer steering commands, perhaps showing a better understanding of the LHD kinematics, and, therefore, greater abilities to predict the behavior of the vehicle.

Table 4.

LHD input difference, state difference and distance to the walls for autonomous navigation and manual operation. ID: Dataset Identifier. ACD: Average Command Difference (Eu). MCD: Max Command Difference (Eu). ASD: Average State Difference (ELHD). MSD: Max State Difference (ELHD). H F/B: Heading Forward or Backwards. ADLW: Average Distance to Left Wall. MDLW: Minimum Distance to Left Wall. ADRW: Average Distance to Right Wall. MDRW: Minimum Distance to Right Wall.

Figure 17.

Autonomous System steering commands and LHD steering angle on dataset 14.

Figure 18.

Human operator steering commands and LHD steering angle on dataset M1.

Figure 19.

Autonomous System propel commands and LHD speed on dataset 14.

Figure 20.

Human operator propel commands and LHD speed on dataset M1.

The average and minimum distances to both tunnel walls are also shown on Table 4. In this regard, the system and the human operator have similar performance, with the human operator preferring to be slightly closer to the left wall (since the cabin is on that side, therefore the operator has better visibility on that side), while the autonomous system is usually closer to the right side of the tunnel.

6. Conclusions

The proposed topological navigation and localization system for LHDs was developed and tested in simulation, field trials, and finally, in a production tunnel of a copper, underground, sublevel stoping mine. Using this system, the LHD was able to navigate safely inside the mine, maintaining a safe distance between the LHD and the tunnel’s walls at all times.

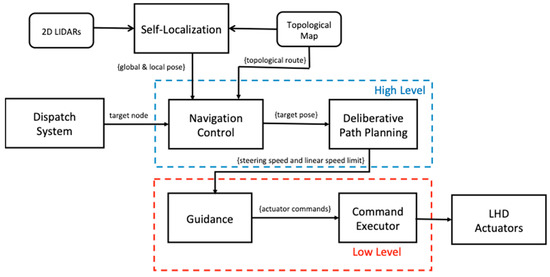

Parameterization of the navigation conditions for each individual TM node was crucial for achieving the desired behavior on the underground industrial tests. The software modularization allowed the development of specific software components for tackling the different challenges of the autonomous navigation. The Navigation Control module manages the mission requests and the overall navigation behavior. Deliberative Path Planning generates local driving trajectories for the Guidance module to follow, while avoiding the tunnel walls and obstacles. Command Executor maintains a queue of consistent and smooth commands to guarantee short-term operation, while simultaneously maintaining system safety. Finally, global and local localization allows maintaining an estimation of the pose of the LHD inside the mine.

When comparing the automation system with a seasoned human operator, it shows a slightly slower performance (about 10% in terms of average instant speed), which is not that serious when taking into consideration all the safety and operational benefits of the system. Besides being faster, the human operator showed smoother driving and more control of the LHD, but this did not necessarily reflect on the performance of the system, or at least it was not noticeable when supervising the operation. It needs to be considered that the tunnel was very narrow and the system needed to be tuned to drive very near to the walls, at a distance of about 10 [cm], in order to be able to drive through some parts of the tunnel (the LHD manufacturer recommends a minimum distance of 50 [cm] to each side of the tunnel).

One of the major problems during testing on site was the lack of a wireless communication infrastructure with the capabilities of high speed roaming. This caused preemptive stops and/or speed reductions while going through the tunnel, hindering the optimizing process of the system and hurting the overall performance. A video showing the operator’s graphic interface while the system is driving the LHD autonomously through the tunnel can be found at https://youtu.be/4Q34N25XjpA (accessed on 14 July 2021).

The system is now being installed and tested in a room and pillar mine in Germany, where a more robust, and better performing, network infrastructure will be used.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., I.P.-T., C.T. and J.R.-d.-S.; methodology, M.M., I.P.-T., C.T. and J.R.-d.-S.; software, I.P.-T. and C.T.; validation, M.M., I.P-T. and C.T.; resources, J.R.-d.-S.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., C.T. and J.R.-d.-S.; writing—review and editing, M.M., I.P.-T., C.T. and J.R.-d.-S.; funding acquisition, J.R.-d.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chilean National Research Agency ANID under project grant Basal AFB180004 and FONDECYT 1201170.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is contained in the article itself.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Vallejos for the valuable discussions and support for on-site execution of the experiments, and Felipe Inostroza and Daniel Cárdenas for their valuable help in computing metrics for the results section. We acknowledge Compañía Minera San Gerónimo for providing the mine infrastructure for testing the system, and GHH Chile for supplying the LHD machine needed for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Salvador, C.; Mascaró, M.; Ruiz-del-Solar, J. Automation of unit and auxiliary operations in block/panel caving: Challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the MassMin2020—The 8th International Conference on Mass Mining, Santiago, Chile, 9–11 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scheding, S.; Dissanayake, G.; Nebot, E.; Durrant-Whyte, H. Slip modelling and aided inertial navigation of an LHD. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 25 April 1997; Volume 3, pp. 1904–1909. [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan, R.; Dissanayake, M.W.M.G.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. Autonomous underground navigation of an LHD using a combined ICP-EKF approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Leuven, Belgium, 16–20 May 1998; Volume 4, pp. 3703–3708. [Google Scholar]

- Scheding, S.; Dissanayake, G.; Nebot, E.M.; Durrant-Whyte, H. An experiment in autonomous navigation of an underground mining vehicle. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1999, 15, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poole, R.A.; Golde, P.V.; Baiden, G.R.; Scoble, M. A review of INCO’s mining automation efforts in the Sudbury Basin. CIM Bull. 1998, 91, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä, H. Overview of LHD navigation without artificial beacons. J. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2001, 36, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.M.; Duff, E.S.; Corke, P.I.; Sikka, P.; Winstanley, G.J.; Cunningham, J. Autonomous control of underground mining vehicles using reactive navigation. In Proceedings of the 2000 ICRA: Millennium Conference—IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2000; Volume 4, pp. 3790–3795. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, P.; Corke, P. Autonomous control of an underground mining vehicle. In Proceedings of the Australian Conference on Robotics and Automation, Sydney, Australia, 14–15 November 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, E.S.; Roberts, J.M.; Corke, P.I. Automation of an underground mining vehicle using reactive navigation and opportunistic localization. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–31 October 2003; Volume 3, pp. 3775–3780. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, J. Reactive Navigation of an Autonomous Vehicle in Underground Mines. Ph.D. Thesis, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, J.; Barfoot, T.; Larsson, J. Autonomous underground tramming for center-articulated vehicles. J. Field Robot. 2008, 25, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J.; Appelgren, J.; Marshall, J. Next generation system for unmanned lhd operation in underground mines. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting and Exhibition of the Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration—SME, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 28 February–3 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, D. Sandvik to Automate New LHD fleet at Codelco’s El Teniente Copper Mine. 2016. Available online: https://im-mining.com/2021/02/16/sandvik-to-automate-new-lhd-fleet-at-codelcos-el-teniente-copper-mine (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Schunnesson, H.; Gustafson, A.; Kumar, U. Performance of automated LHD machines: A review. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection, Banff, AB, Canada, 16–19 November 2009; Available online: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-38494 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Walker, S. The drivers of autonomy. Eng. Min. J. 2012, 213, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Paraszczak, J.; Gustafson, A.; Schunnesson, H. Technical and operational aspects of autonomous LHD application in metal mines. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2015, 29, 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, L.G.; Marshall, J.A.; Larsson, J. Experiments in feedback linearized iterative learning-based path following for center-articulated industrial vehicles. J. Field Robot. 2019, 36, 955–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Topal, E. Transformation of the Australian mining industry and future prospects. Min. Technol. 2020, 129, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.G.; Zhan, K. Intelligent mining technology for an underground metal mine based on unmanned equipment. Engineering 2018, 4, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Ma, F.; Jin, C. A model-based method for estimating the attitude of underground articulated vehicles. Sensors 2019, 19, 5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bai, G.; Liu, L.; Meng, Y.; Luo, W.; Gu, Q.; Ma, B. Path tracking of mining vehicles based on nonlinear model predictive control. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silver, D.; Ferguson, D.; Morris, A.; Thayer, S. Feature extraction for topological mine maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Sendai, Japan, 28 September–2 October 2004; Volume 1, pp. 773–779. [Google Scholar]

- Konolige, K.; Marder-Eppstein, E.; Marthi, B. Navigation in hybrid metric-topological maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 3041–3047. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Shin, J.; Kim, H.J.; Park, Y.; Sastry, S. Model-predictive active steering and obstacle avoidance for autonomous ground vehicles. Control Eng. Pract. 2009, 17, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, J.; Oksanen, T.; Visala, A. Navigation system for agricultural machines: Nonlinear model predictive path tracking. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2012, 82, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Khajepour, A.; Melek, W.W.; Huang, Y. Path planning and tracking for vehicle collision avoidance based on model predictive control with multiconstraints. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2016, 66, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-del-Solar, J.; Vallejos, P.; Correa, M. Robust autonomous navigation for underground vehicles. In Proceedings of the Automining—5th International Congress on Automation in Mining, Antofagasta, Chile, 30 November–2 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, E. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer. Math. 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koenig, N.; Howard, A. Design and use paradigms for gazebo, an open-source multi-robot simulator. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and System, Sendai, Japan, 28 September–2 October 2004; Volume 3, pp. 2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, M.; Conley, K.; Gerkey, B.; Faust, J.; Foote, T.; Leibs, J.; Wheeler, R.; Ng, A. ROS: An open-source robot operating system. In Proceedings of the ICRA Workshop on Open Source Software, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).