Abstract

Performance management systems (PMSs) in private secondary education are vital, and although several tried and tested public sector performance measurement models exist, limited private secondary school performance measurement models exist in South Africa. This study aims to empirically validate a South African tailor-made theoretical performance measurement model (developed from a systematic literature review of 220 articles) and determine the relationships between its key antecedents (Academic Excellence, Internal Processes, Learning and Growth, and Resources) and their respective sub-antecedents. Data were collected by distributing a hard-copy questionnaire to appointed coworkers at 12 schools in the eThekwini Municipality of KwaZulu-Natal, in Durban, South Africa. The schoolmaster’s permission and blessing were obtained, and a coworker was appointed to assist with the distribution and collection of the structured 5-point Likert-scale questionnaires. A high response rate of 89% (N = 274; n = 244) was realised. The data were tested for normality and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients consistently exceeded 0.70), and investigated for evidence of model validity using an exploratory factor analysis. The data were normally distributed and not skewed, and the antecedents could be validated. The model showed evidence of validity, and the respective relationships between the antecedents were determined. Learning and Growth (16.46%) was the most critical antecedent, followed by Student perspective (15.51%), and Resource perspective (12.20%). The Internal perspective for academic excellence was, surprisingly, the least important (7.94%). The results show that all four antecedents are valid and should be used in the performance measurement of private secondary schools.

1. Introduction

Beyond their instructional role, schools increasingly operate as complex organisations that must strategically manage performance, resources, and stakeholder expectations to remain effective and sustainable. Educational effectiveness research has consistently demonstrated that learner outcomes are shaped by the interaction between student characteristics, teaching quality, school leadership, organisational processes, and resource availability (Sammons et al., 1995; Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008). In parallel, school improvement literature emphasises the importance of continuous, data-informed decision-making, strategic alignment, and organisational learning as central mechanisms for sustained improvement (Hopkins, 2001; Fullan, 2016). From an organisational performance perspective, schools (particularly private schools operating in competitive environments) can be viewed as service-oriented organisations in which intangible resources such as teacher competence, leadership capability, and organisational culture play a decisive role in achieving superior performance (Barney, 1991; Kaplan & Norton, 2004). Against this theoretical backdrop, the development of a context-sensitive performance management model for South African private secondary schools becomes both a managerial and scholarly imperative.

Public schools comprise 90.8% of the 24,900 schools in South Africa. The number of private secondary and primary schools is evenly distributed, with just under 10% of the private schools being secondary schools (Cowling, 2024). Private schools cater to the wealthy and privileged, whereas public schools are more diverse and serve a broader range of populations. Historically, white (predominantly English) South African students attended private schools in KwaZulu-Natal. However, after the first democratic election in 1994 and the economic empowerment of all people in South Africa, the demographics of private schools are now closely resembling those of the country. KwaZulu-Natal has 5790 schools, of which 230 (3.98%) are private schools (IEB, 2025a). However, although KZN has fewer private schools than Gauteng (918) and the Western Cape (319), many of the province’s private schools are prestigious institutions with a rich, historic background.

Private schools, costing on average ZAR 136,000 per annum, target higher-than-average family incomes and some international students (Muzanya, 2023). These elite schools provide a higher-quality education and achieved a university exemption pass rate of 99% in 2023, while public schools averaged only 34% (Muzanya, 2023).

A study by Herath et al. (2023) revealed that school infrastructure is a critical factor that significantly contributes to educational outcomes; therefore, maintaining its high quality is of utmost importance. Due to the ageing of school assets, combined with budget constraints and the rapid growth of student enrolment, many public schools are currently struggling to maintain the required standard in the long-term. Cuesta et al. (2016) found that adequate school facilities, such as toilets, laboratories, and drinking water points, increased learner enrolment and learning.

Studies have shown that many learners in South Africa still attend classes in muddy classrooms or under trees, and in some instances, two grades are accommodated within a single classroom (Marais, 2016; Meier & West, 2020). If left unresolved, inadequate school infrastructure has the potential to continue adversely affecting teaching and learning outcomes (Mokgwathi et al., 2023).

Thus, sufficient infrastructure remains a key concern in the performance of South African schools. Private schools are less affected because they can afford to develop their own infrastructure, such as boreholes for backup water supply or diesel generators for sustainable electricity supply. Many private schools have already installed alternative electricity supply systems using photovoltaic roof panels and lithium batteries to ensure a conducive learning environment.

The private education market is highly competitive and concentrated (DBE, 2024), and a private school’s performance is a crucial competitive edge. Several studies have examined the impact of various key performance areas on schools (Alolah et al., 2014; Amin, 2021; Brown et al., 2009; Siburian & Pangaribuan, 2020; Gusnardi, 2019; Hasan & Chyi, 2017; Soderberg et al., 2011; Saksono & Bernardus, 2023; Hanushek et al., 2023). In a more focused approach, Kattamaney (2024) examined the impact of school characteristics on mathematics achievement among Grade 9 students. Meanwhile, as of 2001, the Department of Basic Education introduced Whole-School Evaluation (WSE) and several Value-Added Models (VAMs) (Prior et al., 2021). Predictive models using logistic regression and Light Gradient Boosting (LightGBM) also provide policymakers with valuable insights into school performance (Wandera et al., 2019).

However, these existing models do not provide a comprehensive and holistic view of performance in South African private secondary schools. This article addresses this gap by developing a strategic performance measurement scorecard to manage the performance of a private secondary school. The traditional Kaplan and Norton (1992) Balanced Scorecard served as a point of departure for focusing and aligning the performance of private secondary schools. In the scorecard approach, pertinent data are systematically gathered and analysed to evaluate the performance of private schools. A data-driven model facilitates objective data-based decision-making to improve proficiency and eliminate deficiencies more precisely by implementing targeted managerial interventions and efficiently allocating resources.

2. Theoretical Review

This article’s literature review comprises two sections. The first section provides a theoretical overview of performance management, defining it and examining its advantages and disadvantages. It continues to discuss the methodology of measuring the performance of a secondary private school. The second section presents the newly developed theoretical model to measure the performance of secondary private schools.

2.1. Performance Management

2.1.1. Definition of Performance Management

Performance management is commonly defined as an organisational tool that leverages predefined goals and incentives to evaluate team members and serve as a motivator for employees to fulfil their professional responsibilities. Armstrong (2022) defines it as a systematic process for improving organisational performance by developing the performance of individuals and teams, emphasising its role in achieving better results through understanding and managing performance within an agreed framework of planned goals, standards, and competence requirements. Investopedia (2024) defines performance management as a tool that helps managers monitor and evaluate their employees’ work, aiming to create an environment where individuals can perform to their best abilities and align with the organisation’s overall goals. Similarly, the Cambridge Dictionary (2025) defines performance as activities ensuring goals are consistently met effectively and efficiently. Venkat et al. (2025) suggest that AI-integrated performance management has the potential to transform performance management and employee development, fostering a more efficient and dynamic work environment aligned with organisational goals.

2.1.2. The Importance of Measuring Performance Management

Measuring performance management is crucial to an organisation’s overall strategy and success, requiring continuous, systematic practices at both the individual and team levels. The core emphasis of performance management definitions is the importance of aligning individual and team efforts with organisational goals. This alignment is fundamental, as an organisation’s success is intrinsically linked to its employees’ contributions, ensuring that these efforts are directed towards the right objectives (Walters, 1995). Measuring and managing performance was formalised in the early 1990s. Examples such as Lockett’s (1992) concept of “Working towards the achievement of shared meaningful objectives” and Armstrong and Baron’s (1998) focus on “Improving the performance of the people who work in them” universally underscore the goal of harmonising individual and organisational objectives. Several authors, including Kaplan and Norton (1992), have highlighted the positive impact of a robust Performance Management System (PMS) on growth and progress. They recognised that a PMS extends beyond mere performance monitoring; it is fundamentally about enhancing overall output and productivity. By improving knowledge and skills, individuals and teams can be effectively trained to perform more effectively, thereby maximising efficiency and goal attainment. Mohrman and Mohrman’s (1995) assertion that PMS is about “managing the business” emphasises its proactive role in driving organisational advancement. Thus, performance management is positioned as a strategic, integrated process that empowers individuals and teams to achieve their goals, grow professionally, and ultimately enhance organisational productivity and success.

Research further supports this, with Jukka (2023) finding that aligning a company’s business strategy with its management control system (MCS) is a key determinant of organisational performance. The study indicated that different business strategies achieve better results when paired with appropriate management controls through an MCS. Furthermore, in public–private partnerships, a PMS has helped practitioners better understand project performance processes, enabling them to make informed decisions that enhance future outcomes. For private secondary schools, establishing clear, measurable goals is paramount for focused efforts and effective resource utilisation, as research indicates that schools with well-defined objectives are more likely to perform purposefully and achieve better results. Adopting a balanced scorecard provides a comprehensive view of school performance across various dimensions, enabling the identification of strengths and weaknesses to inform targeted improvement decisions.

2.1.3. Advantages and Disadvantages of Performance Measurement

The following are advantages associated with measuring performance management:

- Identifying weaknesses: Performance measurement can pinpoint areas where students and teachers face difficulties, allowing for targeted interventions (Banu et al., 2024).

- Improved learner experience: Effective management by principals and school management teams is crucial for staff development, which in turn, improves or maintains students’ academic performance (Arendse et al., 2024).

- Accountability: Establishing clear performance standards can hold educators and institutions accountable, potentially improving teaching practices (T. Vandeyar & Adegoke, 2024).

- Resource allocation: Performance assessment data can guide policymakers in effectively allocating resources to address disparities in educational quality (Mlachila & Moeletsi, 2019).

- Enhanced teaching-learning experiences: Integrating Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in schools, supported by training, enhances teachers’ educational ability and improves integrated learning in classroom instruction (T. Vandeyar & Adegoke, 2024).

However, performance management could be associated with some disadvantages, such as

- Narrow focus: Prioritising testing often leads to less time for innovative instruction and a reduction in actual curriculum content, hindering holistic learning (Nahar, 2023).

- Low motivation: High-stakes testing has been found to reduce motivation for both educators and learners (Göloglu Demir & Kaplan Keles, 2021).

- Socioeconomic factors: Performance metrics may not adequately account for students’ diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, potentially leading to skewed results and perpetuating inequalities (Mlachila & Moeletsi, 2019).

2.1.4. Measuring Performance Management in a School Setting

Measuring overall school performance involves considering several influencing factors. Ahmadi et al. (2025) identified five main factors affecting students’ academic performance: individual factors, school factors, family and social factors, peer factors, and occupational factors. Among these, student mental health and the mental dimension of the family environment are highlighted as critical indicators. Educational reforms also play a significant role in measuring student performance. Adeniyi et al. (2024) reviewed educational reforms across several African countries, including curriculum modifications, teacher training, and technological advancements. Their findings emphasise the need to examine the practical effects of policies on students, utilising measures like standardised test scores, graduation rates, and qualitative assessments. Contextual factors, including socioeconomic disparities, cultural influences, and infrastructure challenges, significantly impact the implementation and outcomes of educational reform. In South Africa, Ngcobo and Ndovela (2025) investigated the effectiveness of financial performance monitoring in public schools. They found that a lack of clarity, inadequate training for governing body members, non-user-friendly financial guidelines, and poor communication and coordination significantly impact a school’s performance. Their recommendations included developing a user-friendly digital training manual for finance committees and governing bodies, as well as a digital monitoring and evaluation model that integrates artificial intelligence to track fund use and school performance. In principle, two lines of thought are used to measure performance. That is, to use a generalised or standardised model or scorecard (such as the Whole-School Evaluation developed by the Department of Basic Education (DBE, 2001), Value-Added Models (Prior et al., 2021), or the generalised Kaplan and Norton’s (1992) Balanced Scorecard). Alternatively, an organisation (or school) can develop a bespoke, tailored model. Bespoke, tailored models refer to unique, tailor-made models or scorecards that specifically measure all the antecedents relevant to the organisation (Wood, 2025). This organisation could also refer to a school and its environment, such as secondary private schools in the South African context.

2.1.5. Standardised Models

The South African Department of Basic Education introduced the Whole-School Evaluation (WSE) policy in 2001. This evaluation included external and internal school self-evaluation components (DBE, 2001). The primary goal of a WSE is to measure and then to empower schools through inclusion and improvement. Key aspects of this standardised approach include (DBE, 2001; MacBeath et al., 2003; MacBeath, 2005):

- Internal and External Evaluation: Incorporating both forms of evaluation aligns with international trends.

- Dual-purpose self-evaluation: Recognised for accountability and its potential to drive improvement.

- Stakeholder Involvement: Applying methods like interviews, discussions, classroom observations, and SWOT analyses with stakeholders such as the school management, teachers, support staff, school governing bodies, parents, and learners.

- Comprehensive school functions: The WSE in South Africa covers nine focus areas, namely Basic functionality of the school, Leadership, management and communication, Governance and relationships, Quality of teaching and learning, and educator development, Curriculum provision and resources, Learner achievement, School safety, security and discipline, School infrastructure, and Parents and community.

Although the WSE (and other) standardised models are valuable tools, they are predominantly developed for public-school performance. Several focus areas are similar (such as learner achievement, curriculum provision, or infrastructure), while others (such as governance, leadership, and the community) differ widely in the private school environment. Private school principals and the school board are business managers, overseeing budgets, income, profitability, and student recruitment (for example) to remain competitive in the market, while their public counterparts act as administrators of government funding. Although private schools are subject to some regulations (such as quality approval under the DBE’s and can receive subsidies, they operate under different criteria than public schools and are not evaluated using the same framework (ISASA, 2025). The WSE or other standardised public school models are thus not suitable for measuring the performance of a private school competing in the open market as a business.

2.1.6. Bespoke or “Tailor-Made” Models

Bespoke (tailor-made) models offer a more customised approach to performance assessment. One such model is the School Weavers Tool. It is an international school performance measurement tool validated in at least eight countries (including South Africa) (Díaz-Gibson et al., 2021). This diagnostic tool enables educational leaders to evaluate school culture from multiple perspectives, fostering deep reflection and facilitating a comprehensive 360-degree evaluation of qualitative aspects of a learning ecosystem (Whittaker & Kure, 2025). Other models, such as Logistic Regression and Light Gradient Boosting (LightGBM), employ machine learning techniques to develop predictive models for assessing school performance in South Africa. These models utilise data from community surveys, school master lists, and government reports to identify critical factors, such as access to clean water, sanitation, healthcare, electricity, household goods, mobile Internet, and community safety, that affect school performance (Wandera et al., 2019). These models offer policymakers valuable insights, as they are designed for accuracy, stability, and interpretability. In another bespoke model, Van Den Heever et al. (2024) combined machine learning with agent-based modelling to simulate learner progression and highlight key influencing factors in South African public high schools. Their XGBoost model, integrated into an agent-based framework, accurately predicts learner progression and serves as a strategic tool for evaluating educational interventions.

The applied school performance management models include both quantitative and qualitative designs. The popular quantitative models are the Value-Added Models (with or without multivariate outcomes), Adapted International Models, and Comparative Analysis models (Prior et al., 2021 Wandera et al., 2019; Sen, 2010). Popular qualitative models include the Integrated Quality Management System, Instructional and Transformational Leadership Integration, Performance Management Development Systems (Mchunu & Steyn, 2017; Shava, 2021; Ajani & Dlomo, 2025).

2.1.7. Suitability of Tailor-Made Models for South Africa

This study used a tailor-made model to measure the performance of private higher secondary schools. This decision is primarily based on the uniqueness of the private secondary school environment and the inability of existing public-school models to adequately measure private school performance, which is heavily influenced by business and entrepreneurial principles. Furthermore, South Africa’s diverse cultural landscape and complex political and economic circumstances present unique challenges in an educational environment. This study then developed and applied a theoretical model to specifically measure performance at private secondary schools. This tailor-made approach postulates the following advantages:

- Contextual relevance: Unlike standardised models that may not fully capture local nuances, tailored approaches can be adapted to the specific cultural and linguistic diversity of South Africa, ensuring validity and relevance (S. Vandeyar & Archer, 2010).

- Addressing specific challenges: South Africa faces distinct issues such as socioeconomic disparities, infrastructure challenges, and varying levels of access to resources like clean water, electricity, and community safety (Wandera et al., 2019). Tailor-made models, especially those leveraging machine learning, can incorporate these critical factors to provide policymakers with more accurate and interpretable insights (Wandera et al., 2019).

- Comprehensive Assessment: Tailor-made models can be adapted to include both academic and non-academic outcomes, providing a more holistic and equitable assessment of school effectiveness, which is crucial in a diverse and resource-constrained environment like South Africa (Prior et al., 2021; Sen, 2010).

- Strategic decision-making: Predictive models using machine learning and agent-based simulation offer strategic tools for evaluating and refining educational interventions, providing a performance measurement framework that is highly relevant to South Africa’s education system (Van Den Heever et al., 2024).

- Flexibility and customisation: Tailor-made models can comprehensively perform a 360-degree evaluation of qualitative aspects of a learning ecosystem, customised to the unique culture and needs of individual schools or regions (Whittaker & Kure, 2025).

- Given the complexities and specific needs of South African schools, tailor-made models offer a more accurate, equitable, and effective means of measuring and enhancing performance.

2.2. A Theoretical Model to Measure Secondary Private Schools’ Performance

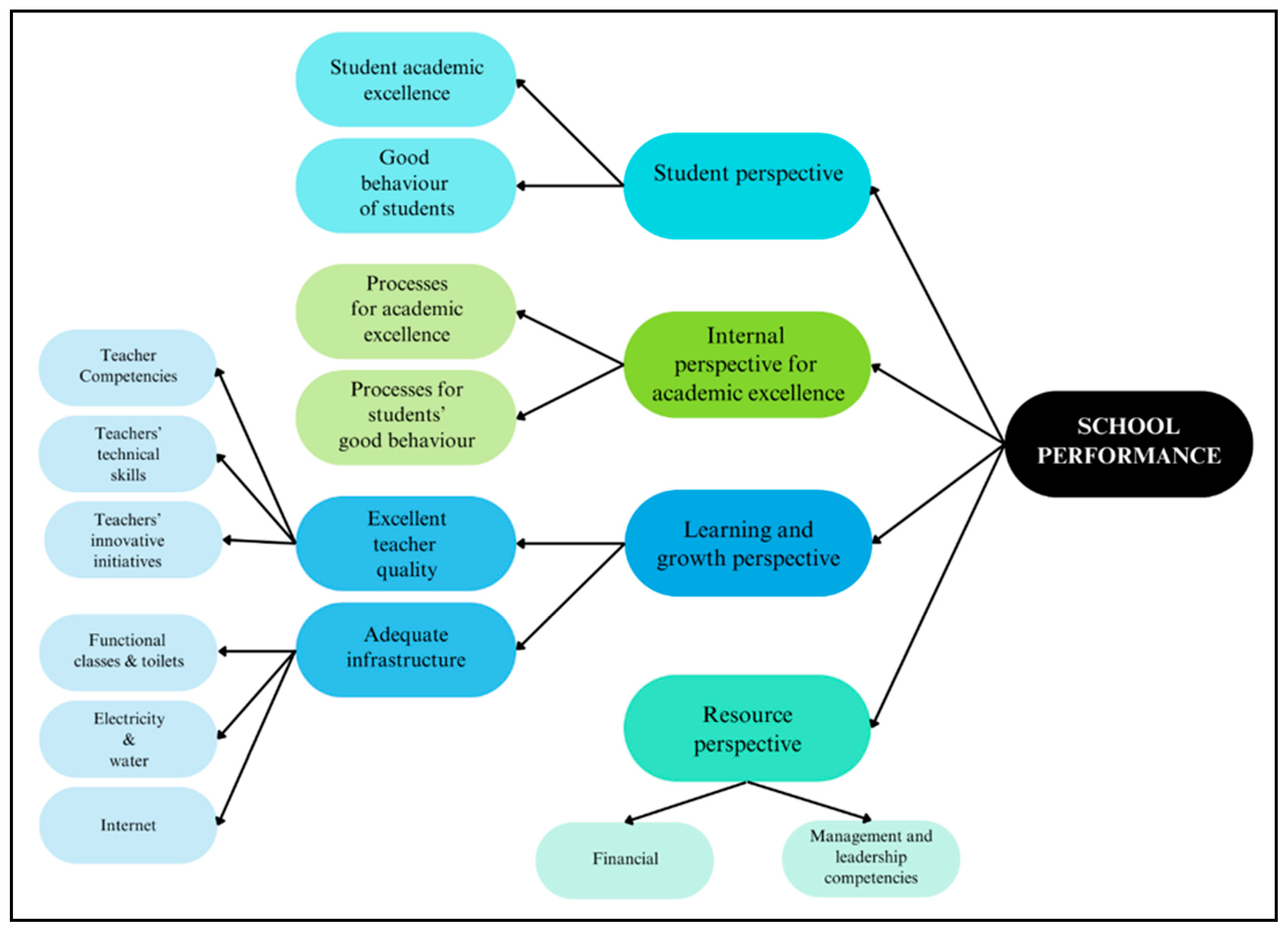

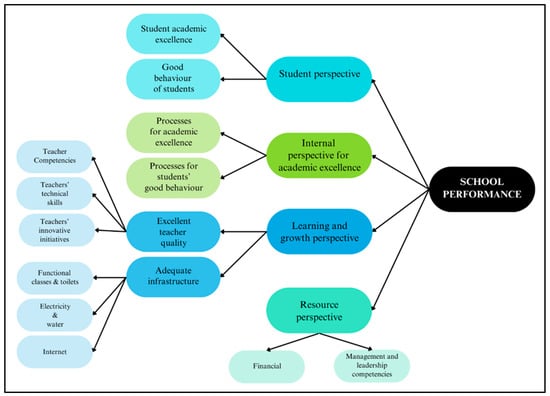

The authors propose a new strategic performance scorecard model for private secondary schools, adapting Kaplan and Norton’s (1992) original balanced scorecard framework. This theoretical model outlines potential relationships between its key influences (variables), namely (1) Academic Excellence, (2) Internal Processes, (3) Learning and Growth, and (4) Resources and Their Impact on School Performance.

These concepts are conceptually explained and educationally justified; although the structural logic of the proposed model draws on the balanced scorecard approach, the four perspectives are conceptually grounded in the organisational, pedagogical, and social functions of secondary schools. To enhance theoretical coherence and reduce ambiguity, each perspective is defined explicitly in educational terms and justified with reference to established educational theory.

- School performance is conceptualised as a multidimensional educational construct reflecting a school’s capacity to promote learner academic achievement, positive learner behaviour, professional teaching practice, organisational sustainability, and stakeholder confidence. This understanding aligns with educational effectiveness research, which views school performance as the product of interacting instructional, leadership, and organisational processes rather than as a single output measure.

- The stakeholder perspective reflects the school’s educational accountability to learners, parents, educators, and governing bodies. In contrast to market-oriented stakeholder models, this perspective captures learner engagement, parental trust, and confidence in the school’s educational mission. Educational leadership and governance literature emphasises that stakeholder relationships in schools are central to legitimacy, accountability, and sustained effectiveness, particularly in private schooling contexts.

- The internal perspective represents the core pedagogical and organisational processes through which educational goals are achieved. These processes include curriculum delivery, assessment practices, learner behaviour management, and teacher collaboration. The educational effectiveness and school improvement literature consistently identifies these internal processes as the primary mechanisms linking leadership and resources to learner outcomes.

- The learning and growth perspective reflects the school’s professional and organisational capacity to sustain improvement over time. In educational terms, this perspective encompasses teacher professional development, leadership capacity, organisational learning, and a supportive school culture. These elements are widely recognised as foundational conditions for instructional improvement and long-term school effectiveness.

- Finally, the resource perspective captures the governance, financial, and infrastructural foundations that enable effective schooling. Private secondary schools, in particular, depend on sound governance structures, financial sustainability, and adequate physical and technological resources to support teaching and learning. This perspective reflects the role of school boards and leadership teams in ensuring responsible stewardship and strategic alignment of resources with educational priorities.

Taken together, these four perspectives form an education-centred performance management framework that reflects the distinctive organisational, pedagogical, and social functions of secondary schools. While informed by balanced scorecard logic, the perspectives are theoretically reinterpreted to align with educational effectiveness, leadership, and governance literature, thereby distinguishing the model from generic corporate performance tools. Notably, each of these perspectives (as measurable antecedents) also comprises sub-antecedents.

The first sub-antecedent is Student Academic excellence, which is measured by criteria such as the results in the National Examination (Grade 12/Matric), School completion rate, Knowledge seeking skills and outcomes, and Capability to integrate knowledge (Rompho, 2020; Maqbool et al., 2024; Sengendo & Eduan, 2024; Tan et al., 2024). The second sub-antecedent is Good behaviour of students, measured by criteria like attendance, discipline, characteristics, value, and behaviour, and school expulsion rates (Rompho, 2020; Fomba et al., 2023 Wei & Ni, 2023; Chuktu et al., 2024). The antecedent Internal Perspective for Academic Excellence also comprises two sub-antecedents. These are the processes that facilitate academic excellence and good student behaviour. Saksono and Bernardus (2023) contextualise the Internal process for academic excellence by stating that it is essential for a school to create higher employee (teachers and staff) satisfaction, using a quantitative scorecard as a strategic framework for holistic evaluation. Focusing on an internal perspective on good behaviour contributes to the establishment of an environment conducive to fostering good behaviour, which culminates in a nurturing environment where students are taught the nuances of good behaviour and are assessed through criteria such as Ethics teaching, School climate, Parent–teacher involvement, and Character education (Rompho, 2020; Gningue et al., 2022; Fomba et al., 2023). Other elements that significantly affected the Internal Perspective on good behaviour are the percentage of public participants in budget preparation and the number of community activities (Rompho, 2020).

The third antecedent pertains to Learning and growth. This antecedent includes excellent teacher quality and adequate infrastructure. Indicators subscribing to the Learning and growth are Innovation initiatives (measured by the number of innovation proposals) and Teacher competencies (measured by the number of teachers completing professional development, to the total number of teachers in a school). Research by Ogunbayo and Mhlanga (2022) also found strong evidence that teacher training, particularly technical training (regarding the Learning and growth antecedent), positively impacts job performance and enhances academic excellence, creating value for stakeholders. The fourth antecedent relates to Resources (such as financial, managerial and leadership resources). Finally, from the resource perspective, financial, leadership, and management resources are essential in any school’s performance. The financial perspective can be further deconstructed into sub-variables such as Financial, Sustainability (net operation cash flow or revenue) Enhancement (revenue realisation, account receivables, collectability), Cost Efficiency (cost realisation, cost/student, budgeting for facilities and infrastructure that support improving the quality of education), Economical (spending the funds received according to the planned expenditures), Efficiency (income budget allocation), and so on (Maqbool et al., 2024; Sengendo & Eduan, 2024; Tan et al., 2024; Enache et al., 2021; Nxumalo et al., 2018). Regarding Management and leadership competencies, school leadership competencies include the leadership styles of principals (strategic/cultural), transformational leadership of the headmaster (which encompasses aspects such as idealised influence, motivation, and stimulation), principal supervision and its impact on teachers, among others (Maqbool et al., 2024; Sengendo & Eduan, 2024; Tan et al., 2024). Each of these four perspectives has sub-constructs and theoretically founded measurement criteria. Figure 1 shows the theoretical model.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model to measure the performance of a private secondary school. (Source: Nag et al., 2025).

Using a scorecard as a strategic framework for performance management in private secondary schools within South Africa has significant theoretical implications that may substantially influence the educational domain. A significant theoretical implication concerns the congruence between objectives and outcomes (Siburian & Pangaribuan, 2020). Implementing a scorecard enables educational institutions to effectively articulate their strategic goals, objectives, and desired outcomes in alignment with the municipality’s overarching educational mission. Establishing this alignment facilitates a unified approach to education, encourages uniformity and collaboration among educational institutions, and enhances educational outcomes (Alolah et al., 2014; Amin, 2021; Brown et al., 2009). Another noteworthy theoretical implication pertains to prioritising decision-making based on empirical data.

The scorecard approach involves systematically gathering and examining pertinent data to evaluate the performance of educational institutions. The data-driven decision-making process enables academic institutions to identify both areas of proficiency and deficiency more precisely, thereby facilitating the implementation of targeted interventions and the allocation of resources (Gusnardi, 2019; Hasan & Chyi, 2017; Soderberg et al., 2011; Saksono & Bernardus, 2023; Hanushek et al., 2023). Furthermore, this approach promotes a culture of responsibility and openness, as educational institutions must justify their achievements against predetermined criteria and demonstrate ongoing improvement. The strategic framework also incorporates the balanced scorecard concept, which encompasses various dimensions of school performance beyond academic accomplishments alone. A scorecard offers a more comprehensive assessment of a school’s effectiveness by considering various perspectives, including student satisfaction, teacher development, and community engagement (Bremser & White, 2000; Siburian & Pangaribuan, 2020).

This approach, characterised by its equilibrium, is supported by contemporary educational theories that underscore the importance of comprehensive growth and equipping students for the challenges they may encounter outside the academic realm. Furthermore, the strategic framework fosters a culture of learning and innovation within educational institutions. To achieve established performance objectives, educational institutions can explore novel pedagogical approaches, curriculum advancements, and systems to support students (Dariyo et al., 2022). The prevalence of an innovative culture can yield widespread benefits, extending beyond individual students to encompass the larger educational community through the dissemination and adoption of successful practices. Although Rompho’s (2020) study found strong evidence for using scorecards in education, a balanced scorecard for schools is not ideally suited to the Balanced Scorecard by Kaplan and Norton, but the principle is sound. A school that consistently achieves high academic achievement indicators is likely to be perceived as delivering high-quality education to its students (Brown et al., 2009; Rahayu et al., 2023). Additionally, this enhances stakeholder satisfaction and positively impacts school performance in terms of growth, financial stability, reputation, and enrolment numbers (Rompho, 2020). Regarding good student behaviour, Saksono and Bernardus (2023) suggest that students should develop good character and spirituality (well-being education) to reflect these qualities in their daily attitudes at school. Likewise, good academic performance increases parental satisfaction (Wei & Ni, 2023). As a result, parents will be more involved and engaged, thereby increasing their satisfaction (Wei & Ni, 2023), which in turn will improve the school’s reputation and increase its revenue.

Several school attributes were important in determining parents’ satisfaction with their public primary school. It is common for parents to become dissatisfied with the quality of services their children receive, and they may react by withdrawing their children from their current school in search of better options at another school. If parents continue to be dissatisfied with services, future enrolment numbers in public primary schools will decrease (Chuktu et al., 2024). Kristanti et al. (2024) highlight the importance of synergy between schools and parents in influencing students’ academic achievement and character development. In another study, Dariyo et al. (2022) found that innovations in teaching schoolteachers led to greater stakeholder satisfaction and a positive impact on academic performance. In another study, Sengendo and Eduan (2024) identified transformational leadership as a significant predictor of academic influence through idealised influence, intellectual stimulation, and individual attention.

Regarding school leadership practices, Tan et al. (2024) showed a significant relationship between leadership and students’ academic performance. In this regard, Zulela et al. (2022) added that character education significantly predicts academic success, emphasising the importance of the antecedent Internal process for good behaviour. Managers and leaders can substantially enhance learners’ outcomes by employing other leadership practices, such as distributed leadership and diverse leadership styles (Jambo & Hongde, 2020; Maqbool et al., 2024). In support, Gningue et al. (2022) demonstrated that teacher leadership significantly impacts school climate. The antecedent Internal perspective for academic excellence can be improved by measuring and managing its performance (Saksono & Bernardus, 2023). These authors stated that schools must use a scorecard to increase employee satisfaction (among teachers and staff) as a strategic framework for holistic school evaluation. An integral component of the Internal Perspective for Academic Excellence is the number of qualified pass-outs in national-level certification examinations (e.g., Grade 12), expressed as a percentage of the total number of students who excelled in matriculation. According to Dariyo et al. (2022), innovations in facilities and infrastructure lead to greater stakeholder satisfaction. Furthermore, the percentage of public members involved in budget preparation and the number of community activities significantly impacted the internal perspective on good behaviour (Rompho, 2020). Regarding the antecedents of learning and growth, excellent teacher quality and adequate infrastructure are critical parameters.

Several studies (Ogunbayo & Mhlanga, 2022; Rompho, 2020; Saksono & Bernardus, 2023) have shown that teacher training, particularly technical training, is significantly associated with improved job performance and academic excellence, thus creating value for stakeholders. The primary determinant of learning and growth is the quality of teachers. An adequate infrastructure should include functional classrooms and bathrooms, a stable electricity and water supply, Internet connectivity, and access to computers. Besides learning and growth, internal processes are driven by a resource perspective. The theoretical scorecard recognises the existence of internal relationships between the antecedents. However, in an empirical evaluation of the scorecard, these relationships can be measured using structural equation modelling to achieve better clarity and obtain a refined model fit for this context.

2.3. Theoretical Positioning of the Model Within Educational Effectiveness and Organisational Performance

While the balanced scorecard provides the structural foundation for the proposed model, the model is also theoretically embedded within broader debates on educational effectiveness, school improvement, and organisational performance in education. From an educational effectiveness perspective, the model aligns with multi-level frameworks that conceptualise school performance as the combined outcome of learner characteristics, teaching quality, school processes, leadership, and resources (Sammons et al., 1995; Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008). The inclusion of student academic excellence, behavioural outcomes, internal academic processes, and learning and growth dimensions reflects this holistic view of school effectiveness, recognising that educational outcomes are shaped by both instructional and organisational conditions.

From a school improvement standpoint, the model resonates with continuous improvement theories that emphasise data-informed decision-making, feedback loops, and strategic alignment (Hopkins, 2001; Fullan, 2016). The scorecard logic operationalises these principles by translating strategic objectives into measurable performance indicators, thereby enabling school leaders to identify performance gaps, prioritise interventions, and monitor improvement over time. In this sense, the model functions not merely as a measurement tool, but as a strategic management framework that supports sustained organisational learning and adaptive change in schools.

The model is further grounded in organisational performance theory, particularly the resource-based view (RBV) and strategic management perspectives. The learning and growth and resource perspectives reflect the RBV assumption that intangible assets—such as teacher competencies, leadership capability, organisational culture, and infrastructure—constitute strategic resources that underpin sustainable performance advantages (Barney, 1991; Kaplan & Norton, 2004). By explicitly modelling these resources and their contribution to school performance, the framework extends organisational performance theory into the educational domain, where schools operate as complex service organisations within competitive environments, especially in the private education sector.

Taken together, the proposed model integrates insights from educational effectiveness research, school improvement theory, and organisational performance management. This theoretical synthesis strengthens the conceptual robustness of the framework and supports its applicability as a context-sensitive performance management tool for private secondary schools operating within the South African educational landscape.

2.4. Educational Leadership, School Governance, and Effectiveness Foundations

Although the proposed performance management model draws on strategic management principles, its conceptual foundation is firmly embedded within educational leadership, school effectiveness, and school governance literature. Educational leadership research consistently emphasises the central role of instructional leadership, transformational leadership, and distributed leadership in shaping teaching quality, school culture, and learner outcomes (Hallinger, 2011; Leithwood et al., 2020). The inclusion of leadership capacity, teacher development, and internal academic processes within the model directly reflects these educational leadership constructs, positioning leadership as a mediating force between resources and educational outcomes.

From a school effectiveness perspective, the model aligns with frameworks that conceptualise effective schools as systems in which governance structures, professional capacity, learning environments, and accountability mechanisms interact to influence performance (Sammons et al., 1995; Bush & Glover, 2014). The student, internal process, and learning and growth perspectives collectively operationalise these dimensions by capturing both instructional quality and organisational conditions necessary for sustained effectiveness.

School governance literature further reinforces the educational grounding of the model. In private school contexts, governing bodies and school boards assume responsibilities that extend beyond compliance to include strategic oversight, financial stewardship, and performance accountability (Caldwell & Spinks, 2013). The resource perspective of the model explicitly incorporates these governance responsibilities by linking financial sustainability, infrastructure provision, and leadership capability to educational performance outcomes. This reflects contemporary governance models that advocate for evidence-based decision-making and transparent performance monitoring in schools (Bush, 2018).

By integrating educational leadership, school effectiveness, and governance theory, the proposed framework transcends the application of a generic corporate performance tool. Instead, it represents an education-centred performance management model that is sensitive to the institutional realities, accountability structures, and pedagogical priorities of private secondary schools.

3. Problem Statement

In schools, teachers and their supervisors initiate the PMS process by creating “Performance Development Plans” (PDPs), which are annual agreements outlining goals and targets. Supervisors check on teachers three times a year to assess their performance (Combs et al., 2006; Deci & Ryan, 2013). A Performance-based Reward System (PBRS) is also part of the PMS system. Its goal is to reward good performance. (Atamturk et al., 2011; Varma et al., 2023). The authors also considered the state of the performance management system in state-run schools in a separate study. The study aimed to determine what teachers and headmasters thought about the impact of performance management on school quality (Holland & Campbell, 2005; Dzimbiri, 2008; Marobela & Andrae-Marobela, 2013; Tan et al., 2024). The analysis of the results showed that teachers in PMS schools had to use a participatory planning process to set their goals, based on the unique setup and culture of each school. People also said that the success of PMS depended on constant feedback, training while employees were on the job, and commitment and motivation. A PMS system for teachers could be more effective if teachers received feedback, were trained by their supervisors, and participated in planning and performance review meetings (Nxumalo et al., 2018).

Private secondary schools should establish a process for collecting data on key performance indicators (KPIs) and regularly review and analyse it to assess performance. This can be achieved through student tests, surveys, staff and parent feedback, and financial reports (Mothusi, 2008; Poister, 2008). Data analysis involves identifying trends, pinpointing areas of strength and weakness, and exploring ways to improve. It is important to regularly report on the school’s performance and progress toward its goals, both inside and outside (Holland & Campbell, 2005; Dzimbiri, 2008; Marobela & Andrae-Marobela, 2013; Hart, 2023). Based on the scorecard’s data and analysis, private secondary schools should develop specific plans to address their challenges and leverage their strengths. These initiatives can include programmes to help teachers improve their skills, support students who are struggling, and changes to the curriculum or teaching methods, as well as programmes to engage parents more fully and increase their satisfaction with the school (Mothusi, 2008; Poister, 2008). Improvement initiatives should align with school goals and include clear action plans, timelines, and the people or teams responsible. Performance management should not be considered as a one-time thing in private secondary schools. Instead, it should be seen as an ongoing process. This entails creating a supportive and collaborative environment where feedback is valued and individuals are encouraged to learn from both successes and failures (Boipono et al., 2014; Mothusi, 2008; Bergdahl et al., 2020).

Schools should regularly review their strategic frameworks, making changes based on feedback and new challenges to ensure that they remain effective in improving performance. Using a scorecard as part of a strategic framework for managing performance can provide private secondary schools in South Africa with a structured approach to achieving their goals and enhancing their overall performance (Molefhi, 2016; Holland & Campbell, 2005; Saksono & Bernardus, 2023). By setting clear goals, developing a school-specific strategic balanced scorecard, monitoring and reporting performance, implementing improvement plans, and fostering a culture of continuous improvement, schools can ensure that they are on the path to excellence and meet the evolving needs of their students, parents, and other stakeholders.

However, none of these studies specifically focus on the challenges of private secondary schools in South Africa. International performance measures lack cultural and African insight and are incomplete for measuring the performance of South African private schools. Managing school performance is problematic for principals and school boards. Although there are regulated agreements among board members and principals regarding the specific performance criteria in the public-school management system, this is not the case in private schools. There are disagreements about which criteria require performance management in private schools, and what the role is in each case. For example, some members strongly emphasise academic performance criteria, while others believe that sports should play a more prominent role because of their marketing value at a private school. Private schools compete in the open market for top pupils against both one another and public schools. As such, private school management must identify the “right” performance criteria and measure these criteria regularly to ensure that their managerial actions yield the desired returns. This is problematic because no South African private school performance scorecard is available for use. This study aimed to develop such a managerial performance scorecard for private secondary schools in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa.

4. Research Objectives

The primary objective was to empirically validate a theoretical model to measure the performance of a private secondary school in South Africa.

The secondary objective was to determine whether significant relationships exist between school performance and the four theoretical antecedents (Student perspective, Internal process for academic excellence perspective, Learning and Growth Perspective, and the Resource perspective).

5. Research Hypotheses

The objective is articulated through the following hypotheses:

H0.

No significant positive effects exist between the four antecedents and the performance of a private secondary school.

H1.

Significant positive effects exist between the four antecedents and the performance of a private secondary school.

H1a.

The Student Perspective has a significant positive effect on the performance of a private secondary school.

H1b.

The Internal Process for Academic Excellence has a significant positive effect on the performance of a private secondary school.

H1c.

The Learning and Growth Perspective has a significant positive effect on the performance of a private secondary school.

H1d.

The Resource Perspective has a significant positive effect on the performance of a private secondary school.

6. Research Methodology

6.1. Research Paradigm

In this study, the authors adopted an epistemological approach rooted in a positivist paradigm, which provided an objective interpretation of events and a scientific rationale for their viewpoints. Three fundamental philosophical assumptions define positivism’s approach to scientific inquiry (Wati, 2024). As part of its ontological foundation, positivism embraces realism, which is the idea that reality is composed of distinct events that humans can experience through their senses (Karupiah, 2022). According to this perspective, there is an objective reality that exists independent of the researcher’s perceptions or beliefs (Park et al., 2020). Positivism employs dualistic and objectivist epistemological frameworks, arguing that researchers and observed reality are separate entities (Karupiah, 2022). For knowledge to be acquired, it must be value-free and objective, and truth must be static and accessible through empirical observation (Park et al., 2020).

In keeping with this epistemological stance, “science is the only valid form of knowledge, and only observable facts can be used for study” (Wati, 2024). According to the positivist paradigm, researchers prioritise observable phenomena that are objectively measurable. The epistemological foundation of objectivism is derived from the observation and measurement of objective reality (Ali, 2024). This approach emphasises the separation between the researcher and the research subject to maintain objectivity. The positivist approach employs systematic hypothesis testing to advance scientific knowledge. By accumulating empirically validated findings, results from hypothesis tests are used to “inform and advance science” (Park et al., 2020). During the study, all characteristics associated with a positivist paradigm were adhered to. By utilising data to empirically test the hypothesis, objectivity was maintained. Both the researcher and the subjects were independent entities, and their responses were recorded using a reliable and valid research instrument, a questionnaire. Furthermore, it followed the norms of a positivist mode of inquiry, including empirical evidence, statistical analysis, generalisable results from large sample sizes, and the identification of causal relationships (Park et al., 2020; Alhoussawi, 2023).

6.2. Methodological Reflection on the Use of Perceptual Survey Data

School performance is a complex and multi-layered construct that encompasses instructional quality, organisational processes, leadership practices, stakeholder relationships, and resource conditions. Capturing this complexity empirically poses methodological challenges, particularly in contexts where comprehensive objective performance data are not uniformly available. The survey-based design adopted in this study addresses this challenge by drawing on the informed perceptions of educators and principals, who are directly involved in the daily instructional and organisational functioning of schools.

Perceptual measures are widely used in educational leadership and school effectiveness research, as educators and school leaders possess contextualised knowledge of teaching practices, learner behaviour, organisational processes, and leadership dynamics that may not be fully reflected in administrative or outcome-based indicators alone. In this sense, perceptual data provide insight into the process dimensions of school performance, which are central to understanding how educational outcomes are produced.

At the same time, reliance on self-reported perceptions introduces potential limitations, including response bias and subjectivity. To mitigate these risks, the study employed established measurement procedures, including scale validation, reliability testing, and aggregating responses across multiple respondents per school. Moreover, the purpose of the model is not to replace objective performance indicators, but to complement them by offering a structured, theory-informed framework for assessing organisational and pedagogical conditions that underpin school performance.

Acknowledging these strengths and limitations enhances methodological transparency and supports the interpretation of the findings as reflective of informed professional judgements rather than objective performance outcomes alone.

6.3. Data Collection and Analysis

A survey-based research design captured the perceptions of educators, administrators, principals, and board members at multiple levels (that is, to measure perceptions of the antecedents, sub-antecedents, and, in some perspectives, a third level). A 5-point Likert scale was used to collect data through a structured questionnaire. Inferential statistics were used to analyse the data and statistically test the model parameters. Exploratory factor analysis validated and simplified the model. The study targeted 18 schools within the eThekwini Municipality in Durban (DBE, 2022), and 12 schools consented to participate, provided that the necessary gatekeeper approvals were followed. As such, the questionnaires were handed in hard copy to the designated person (such as principals, school governing body members, educators, and administrative officers) who were appointed as the gatekeepers for distribution at the respective schools after obtaining informed consent. Data collection occurred between March and May 2025. A total of 285 questionnaires were distributed, and 274 were collected. However, only 244 were usable, yielding an effective response rate of 89%. Table 1 shows the participating schools and the classification of the respondents. This study was approved by both the North-West University Scientific Committee and its Ethics Committee, therefore conforming to the validity norms prescribed in a positivist research study such as this one. The study was classified as a minimal risk study and was issued with a formal ethics number (NWU-01736-24-A4) on 19 September 2024.

Table 1.

Participating schools and respondent classifications.

The data analysis was conducted using IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Version 29) (IBM Corp., 2022b). The analyses include normality tests (kurtosis and skewness), reliability (Cronbach’s coefficient alpha), sample adequacy (Kaiser’s criterion), sphericity (Bartlett’s test) and structural validity (exploratory factor analysis) (Field, 2017; Cortina, 1993; Cassim et al., 2024; Imandin et al., 2016; Tshivhase & Bisschoff, 2024; Pallant, 2020). This article reports on the development of the measuring model. Testing the model structurally and measuring model fit fell outside the scope of this study; this is future work and will be the final stage before operationalising the model.

7. Results

7.1. Suitability of the Data

7.1.1. Cleaning of the Data

The dataset was cleaned in three steps to eradicate potential data errors (Pallant, 2020). This included (1) calculating minimum and maximum values to identify data-capturing errors and remove any out-of-data-range errors outside the Likert scale used, (2) screening and replacing missing values statistically with IBM SPSS (Version 29) so that the IBM AMOS software can calculate modified indices that are used in developing the structural model (Arbuckle, 2021; IBM Corp., 2022a, 2022b), and (3) finding and correcting any other errors. All 244 responses were usable after cleaning the data.

7.1.2. Normal Distribution of Data

Normality measures a dataset’s skewness and kurtosis relative to a normal distribution. Perfect normal distributed data has kurtosis and skewness values of zero. The skewness scores for the four perspectives showed several criteria exceeding the conservative threshold of (−0.5 ≤ Skew ≤ 0.5). Some variables were more strongly negatively skewed (−1 ≤ Skew ≤ 1), meaning that most data points were located to the right of the normal distribution (Pallant, 2020). However, according to the Central Limit Theorem, skewness is not problematic for large samples (n > 20); this study’s sample was 244 (IBM Corp., 2022b). Table 2 presents the normality statistics, which only include variables with questionable skewness and kurtosis, i.e., those with values exceeding 1 or below −1 (these statistics are highlighted in bold in the table).

Table 2.

Normality statistics, means and standard deviations.

Kurtosis refers to the data’s “peakedness”, and skewness refers to the data distribution (Field, 2017; Pallant, 2020). A positive kurtosis (or leptokurtosis) indicates that the data are relatively “highly peaked” compared to the normal bell curve (Pallant, 2020), meaning that the distribution is more heavily tailed than the normal distribution This means that more values are closer to the mean, so the heavy-tailed outlier data will inflate the standard deviation values (McLeod, 2023; Stack Exchange, 2016). The kurtosis results for all four antecedents showed that the variables were within conservative acceptable deviation variances (−1 ≤ kurt ≤ 1) (Tshivhase & Bisschoff, 2024; Field, 2017). However, when analysing behavioural data (like performance management data), McLeod (2023) suggests using less strict kurtosis margins (−3 ≤ Kur ≤ 3). All but three variables fell within McLoud’s acceptable variation (see Table 1). These criteria were: IP11: The school has a good record with a high Grade 12 pass rate (5.354), LG9: The schooling staff has a sense of ownership and responsibility (3.291), and LG10: The school staff treats each other with respect (3.759). In practice, this means that most respondents perceived these criteria similarly, but a few differed significantly (heavy-tailed outliers). These criteria were subjected to the stringent Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality (see Table 3) to determine whether they could be used or discarded (IBM Corp., 2022b).

Table 3.

Tests of normality.

All three criteria’s Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests returned significant p-values (p ≤ 0.05). This means that these three criteria should be retained for analysis because they have acceptable distribution normality. The Shapiro–Wilk p-value statistic confirms these findings (p ≤ 0.05). It was concluded that the data’s skewness and kurtosis were suitable for further multivariate statistical analysis (IBM Corp., 2022a). No criterion should be discarded from the study.

7.1.3. Sample Adequacy, Sphericity and Reliability

Only suitable data can be used in multivariate analysis, such as confirmatory factor analysis or structural equation modelling. As such, the sample must be adequate (possessing sufficient data entries) (Kaiser, Meyer & Olkin test), possess acceptable sphericity (Bartlett’s test), and the data must be reliable (Cronbach’s coefficient alpha). Table 4 shows that the sample was adequate because all four antecedents’ Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin scores exceeded 0.70. Likewise, Bartlett’s Sphericity tests were significant (p ≤ 0.05) (Pallant, 2020; Field, 2017). The data were reliable and exhibited satisfactory internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, with all four antecedents in the model easily exceeding the required 0.70 coefficient (Field, 2017; Pallant, 2020). This was also true for the sub-antecedents. However, only one measuring criterion loaded onto the sub-antecedent Internet; hence, the reliability could not be calculated. Table 4 shows the reliability coefficients for the antecedents and sub-antecedents.

Table 4.

Reliability, sample adequacy and sphericity of perspectives and sub-perspectives.

The alpha coefficients were satisfactory. Hence, it was concluded that the data were reliable and suitable for further analysis. Table 4 also shows the variance explained by each antecedent and its respective sub-antecedents. The rule of thumb suggests that a factor (in this case, an antecedent) should explain at least 50% (preferably 60%) of the variance (Hair et al., 2012; Field, 2017). The sample adequacy 0.812 exceeded the required 0.70, and the sphericity [χ2(1891) = 5764.114, p ≤ 0.01] was also satisfactory. Table 4 shows that all perspectives passed the tests easily, indicating that the data are suitable for validation with multivariate analysis.

7.2. Validity of the Data

The validity of the data and the measuring instrument was tested using exploratory factor analysis (Rehman et al., 2025; Imandin et al., 2016; Bisschoff & Salim, 2014; Moolla & Bisschoff, 2012) with the varimax rotation because varimax aims to maximise the variance explained (Maskey et al., 2018; Field, 2017). Table 5 shows the results of the exploratory factor analysis. The table includes the factor loadings, the variance explained, and the factor names.

Table 5.

Factors and factor loadings.

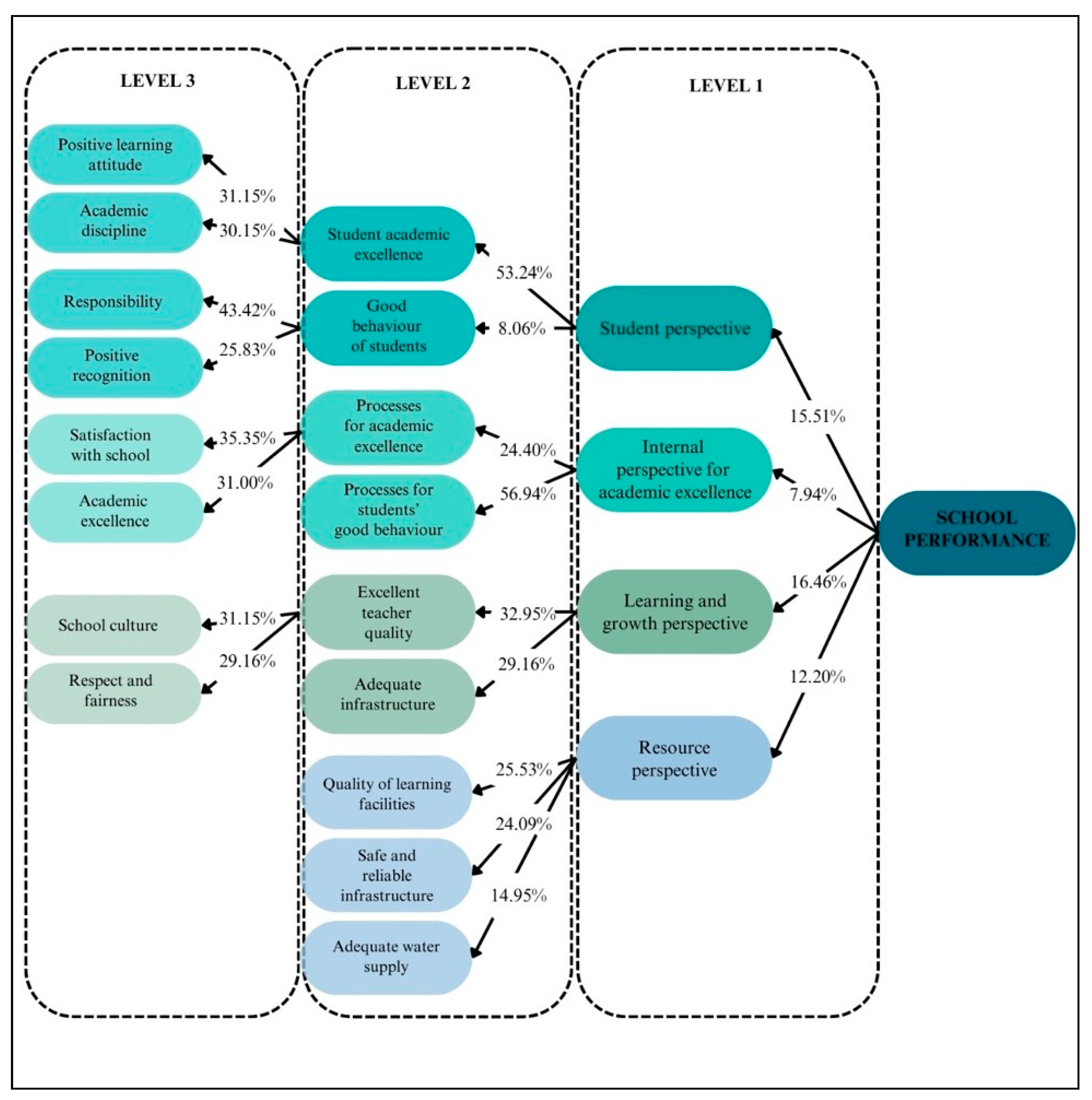

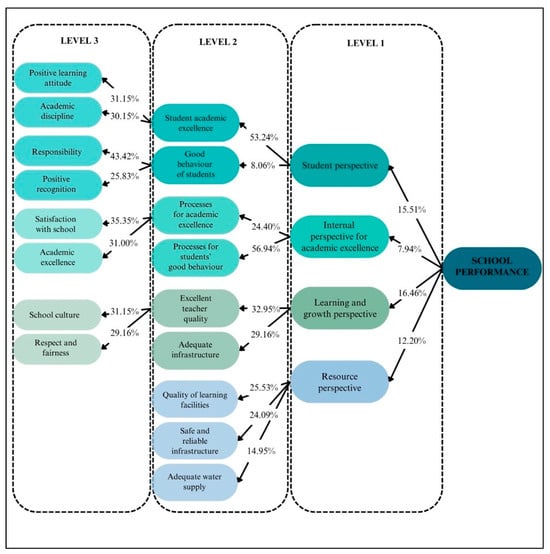

The factor structures (as detailed in Table 5) are modelled in Figure 2. In this model, the four antecedents and their sub-antecedents are shown in three levels. The model explains the contribution of each antecedent or sub-antecedent to secondary private school performance.

Figure 2.

The empirical model.

Figure 2 shows that the antecedent Student perspective accounted for 15.51% of School performance. However, the sub-antecedents Student academic excellence and Good behaviour of students, respectively, contributed 53.24% and 8.06% to the Student perspective. Likewise, the third-level sub-antecedent also contributed to each second-level sub-antecedent in the model. Table 6 shows the direct influence of each sub-antecedent on school performance. For example, the third-level antecedent, a Positive learning attitude, contributed to Student academic excellence (31.15%), which in turn contributed to the Student perspective (53.24%), ultimately contributing to the School performance (15.51%). This means that the direct effect or contribution of a Positive learning attitude to School performance is 2.50%. Likewise, Academic discipline contributes to School performance with 2.40%. Table 6 shows these direct influences of the sub-antecedents on School performance.

Table 6.

Direct contribution of sub-antecedents to school performance.

Table 6 shows that the second level sub-antecedent, Student academic excellence, had the largest direct influence on School performance (8.26%), followed by Excellent teacher quality (5.42%). School managers should thus focus on these antecedents first to maximise the benefits of their managerial interventions. The third-level sub-antecedent, Positive recognition, had the lowest direct influence on school performance and is not a priority for improving it. The influence of the other sub-antecedents was interpreted similarly.

7.3. Interpretive Clarification of Antecedent Rankings

While the statistical results indicate differential strengths in the relationships between the four antecedents and perceived school performance, these findings should be interpreted in light of the perceptual nature of the measurement approach. The relative ranking of antecedents reflects the aggregated perceptions of educators and school leaders participating in the study, rather than objective or normative institutional priorities. These perceptions are shaped by respondents’ professional roles, experiences, and the specific organisational context of private secondary schools within the study sample. Consequently, the rankings should be understood as indicative of how participants perceive and prioritise performance management dimensions, rather than as definitive statements about their inherent or universal importance. This interpretive framing aligns the findings with the study’s survey-based design and avoids overextension beyond the available evidence.

8. Accept or Reject the Hypotheses

Based on the results, the hypothesis H0: No significant positive effects exist between the four antecedents, and the performance of a private secondary school is rejected. Hypothesis H1: Significant positive effects exist between the four antecedents and the performance of a private secondary school, and all four of its sub-hypotheses (H1a, H1b, H1c and H1d) are accepted.

9. Discussion

The practical implications derived from this study are grounded in established educational leadership, school effectiveness, and school governance literature, rather than in managerial efficiency considerations alone. Educational leadership theory emphasises that effective school management is inseparable from instructional leadership, professional capacity building, and the creation of supportive learning environments (Hallinger, 2011; Leithwood et al., 2020). Similarly, school effectiveness research highlights that sustained improvement emerges from the alignment of pedagogical processes, leadership practices, stakeholder relationships, and resource stewardship (Sammons et al., 1995; Creemers & Kyriakides, 2008). The recommendations presented below should therefore be interpreted as education-centred practices aimed at strengthening teaching and learning conditions, organisational coherence, and governance accountability within private secondary schools. However, notably, the validated model represents a general internal stakeholder perspective, with the findings influenced mainly by the dominant respondent group (educators). This perspective should be borne in mind when interpreting the findings.

Three levels of antecedents and sub-antecedents were identified from the statistical analysis. It is encouraging that the original four antecedents identified by the systematic literature review (Student perspective, Internal perspective for academic excellence, Learning and Growth Perspective and the Resource perspective) (Nag et al., 2025) could be retained as the first-level antecedents. These antecedents collectively account for 52% of the variance. This approach of identifying level 1 antecedents dovetails nicely with other business performance models. This implication aligns with educational leadership perspectives (see JAG Consulting Services, 2025) and tracks key performance indicators, such as graduation rates, university admission rates, and standardised test scores, in private schools to maintain growth and attract students. Likewise, a study by the Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE, 2020), recently confirmed by Kristoff (2024), aligns educational leadership and performance by stating that private schools are increasingly popular among parents who are dissatisfied with how public education is managed. As a result, private schools must measure performance to demonstrate satisfactory educational outcomes, and leaders and managers must continuously facilitate an improvement in overall performance.

The results also indicated the significance of academic performance by identifying several related sub-antecedents, namely Student academic excellence (53.24%), Process for academic excellence (24.40%), Excellent teacher quality (32.95%), Academic excellence (31.00%), and Academic discipline (30.15%). In this regard, many private schools do not use the Department of Basic Education’s National Senior Certificate but instead adhere to internationally recognised quality standards set by the Umalusi Council. As a result, private school students undertake the Independent Examiners Board’s (IEB, 2025b) international qualification examinations to verify their academic credibility and maintain excellent academic performance.

Market competitiveness, student recruitment and growth are also key performance indicators. The Learning and Growth Perspective accounted for 16.64% of the school’s overall performance. Private schools in South Africa are gaining market share. According to the Department of Basic Education (DBE, 2024), the proportion of students attending private schools versus public schools increased from 2.5% in 1999 to 5% in 2023 (noting the increasing number of high school students over these years, the real numbers have consequently more than doubled). The Quality of teachers (32.95%) and Adequate infrastructure (29.95%) significantly contributed to market attractiveness, competitiveness and, resultantly, the school’s growth. Interestingly, the Resource perspective (12.20%) also identified detailed infrastructural performance areas. These were a Safe and reliable infrastructure (24.09%) and an Adequate water supply (14.95%). These factors, along with sufficient resources, align well with educational leadership perspectives that create a cycle in which good teachers are attracted to better resources (Rompho, 2020). These and other factors contribute to overall Satisfaction with the school (35.35%) (Firmandani et al., 2023; Funeka et al., 2022). The final model (as depicted in Figure 2) was successfully validated with empirical data. The model effectively illustrates the impact of antecedents and sub-antecedents on school performance and proposes a scorecard that school boards, principals, investors, and other related stakeholders can use to measure, manage, and track the performance of private secondary schools. Continuous measurement can also provide a longitudinal performance map, offering insight into how well managerial interventions are (or are not) effective.

Regarding the contextual scope and generalisability of the findings, this study should be interpreted with its specific context in mind. The empirical analysis was based on private secondary schools operating within the eThekwini district of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, a context characterised by rigid regulatory conditions, governance structures, market dynamics, and socio-economic factors. As such, the validated relationships reflect perceptions of school performance management within this localised setting and should not be assumed to be directly generalisable to other educational contexts.

Rather than offering universal claims, the study provides context-sensitive insights into how performance management dimensions may be structured and perceived within private secondary schooling. The proposed model is therefore best understood as analytically transferable rather than statistically generalisable, meaning that its conceptual structure may inform similar investigations in other contexts, but requires empirical validation before application elsewhere. Explicit recognition of this contextual embeddedness strengthens the interpretation of the findings and aligns the study with best practices in educational and organisational research.

10. Conclusions

This study employed multivariate statistical techniques to empirically validate a performance management model for private secondary schools in the eThekwini district of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The findings provide empirical support for the proposed scorecard’s internal structure, demonstrating statistically significant linear relationships among the identified antecedents and sub-antecedents, as well as their associations with perceived school performance. In this respect, the study provides a context-specific, empirically grounded framework for understanding performance management in private secondary schooling.

Rather than offering causal explanations or prescriptive solutions, the validated model should be interpreted as an analytical and diagnostic framework that captures educators’ and school leaders’ perceptions of key organisational, pedagogical, and governance-related dimensions of school performance. The results suggest that the model may assist school managers, principals, and members of school governance boards in developing a more structured understanding of how different performance dimensions are interrelated and how they collectively shape overall school functioning.

From a practical perspective, the model may serve as a supportive decision-making and reflection tool, enabling school leaders to identify perceived strengths and areas for development, facilitate strategic discussions, and inform medium- to long-term planning processes. However, the findings do not imply that the model can independently measure objective school performance or directly evaluate the success or failure of specific managerial interventions. Instead, the model is best viewed as complementary to other performance indicators and evaluative mechanisms used in school management and governance.

The study further contributes to the limited empirical literature on performance management in South African private secondary education by extending balanced scorecard logic into an education-centred framework. Future research could examine the model’s applicability in other private school contexts or educational phases, such as primary or early childhood education, and could explore its integration with objective performance data or longitudinal designs to further strengthen its explanatory power.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.N., C.A.B. and C.J.B.; methodology, D.N. and C.A.B.; software, C.J.B.; validation, D.N., C.A.B., and C.J.B.; formal analysis, C.J.B.; investigation, D.N.; resources, C.J.B.; data curation, C.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.N.; writing—review and editing, C.A.B. and C.J.B.; visualization, D.N.; supervision, C.A.B. and C.J.B.; project administration, D.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved North-West University Ethics Committee (NWU-01736-24-A4 and 19 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adeniyi, I. S., Hamad, N. M. A., Adewusi, O. E., Unachukwu, C. C., Osawaru, B., Onyebuchi, C. N., & David, I. O. (2024). Educational reforms and their impact on student performance: A review in African countries. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 21(2), 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S., Salehi, K., & Javadipour, M. (2025). A systematic review of measuring the effectiveness of the academic performance of elementary school students. Iranian Journal of Educational Sociology, 8(1), 192–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ajani, O. A., & Dlomo, S. S. (2025). Enhancing school administration in rural South African schools: Challenges and opportunities. Using the scoping review method. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 10(1), 332–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhoussawi, H. (2023). Perspectives on research paradigms: A guide for education researchers. International Research in Education, 11(2), 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I. M. (2024). A guide for positivist research paradigm: From philosophy to methodology. Ideology Journal, 9(2), 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alolah, T., Stewart, R. A., Panuwatwanich, K., & Mohamed, S. (2014). Determining the causal relationships among balanced scorecard perspectives on school safety performance: Case of Saudi Arabia. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 68, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, C. (2021). Balanced scorecard perspectives on school performance at the Islamic Primary School Lentera Hati. ANP Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 2(2), 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2021). IBM SPSS AMOS 28 user’s guide. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Arendse, B., Phillips, H. N., & Waghid, Z. (2024). Leadership dynamics: Managing and leading continued professional teacher development in schools to enhance learner performance. Perspectives in Education, 42(4), 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. (2022). Armstrong’s handbook of performance management: An evidence-based guide to performance leadership. Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M., & Baron, A. (1998). Performance management: The new realities (3rd ed.). Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Atamturk, H., Aksal, F. A., Gazi, Z. A., & Atamturk, A. N. (2011). Evaluation of performance management in state schools: A case of North Cyprus. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 40, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Banu, S. B., Kumar, K. S., Rizvi, M., Rai, S. K., & Rana, P. (2024). Towards a framework for performance management and machine learning in a higher education institution. Journal of Informatics Education and Research, 4(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, N., Nouri, J., Fors, U., & Knutsson, O. (2020). Engagement, disengagement and performance when learning with technologies in upper secondary school. Computers & Education, 149, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]