Abstract

This study analyzes how Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) are discussed in the scientific literature, focusing on their relationship with social entrepreneurship, socioeconomic inclusion, sustainable development, and economic growth. The study adopts a narrative literature review with an analytical approach, drawing from nationally and internationally recognized databases. Additionally, this study distinguishes entrepreneurship education from social entrepreneurship, recognizing that while both share core values, they require distinct educational strategies and institutional support. The results were categorized into seven analytical dimensions, allowing a comprehensive evaluation of the relevance, challenges, best practices, and future perspectives of EEPs in higher education. Good practices were identified, as well as the importance of strengthening community networks and adopting active methodologies and emerging technologies as strategies to expand the programs’ impact. Practical recommendations were organized by target audiences—including educators, policymakers, institutional managers, and researchers—to support more inclusive and context-sensitive, and growth-oriented implementation of EEPs. This study reinforces the relevance of EEPs as instruments of social transformation and sustainable development, and recommends further investigation into the impacts of EEP on vulnerable communities, and developing more effective inclusion strategies.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) are understood in this study as formal or complementary educational initiatives developed within higher education institutions, designed to foster entrepreneurial competencies and value creation in real-world social contexts (Lackéus, 2015). This research focuses exclusively on EEPs implemented in higher education, whether integrated into the formal curriculum or offered as extracurricular or extension programs. Although general EEPs are referenced to provide conceptual context, the analytical emphasis is placed on those specifically oriented toward social entrepreneurship and socioeconomic inclusion. General EEPs are not subject to systematic analysis; they are mentioned only to clarify key concepts and to contrast with socially oriented EEPs. This study does not empirically examine basic education—defined here as primary or secondary education—and any mention of foundational levels appears solely as part of the theoretical background.

Entrepreneurship plays a critical role in economic and social development by driving innovation, creating jobs, and enhancing competitiveness. The effectiveness of entrepreneurship hinges on empowering individuals to identify opportunities, manage risks, and implement innovative solutions. In this context, entrepreneurship education becomes essential for developing skills such as creativity, critical thinking, resilience, and leadership, preparing future entrepreneurs and managers to ensure business sustainability and to operate effectively in an increasingly dynamic and globalized environment.

Entrepreneurship has increasingly emerged as a global strategy to foster innovation, strengthen competitiveness, and drive both economic and social development (Kuratko, 2005; Audretsch & Keilbach, 2008). In the context of knowledge economies, the development of entrepreneurial competencies becomes essential for addressing contemporary challenges such as youth unemployment, inequality, and the need for innovative solutions in multiple sectors (Lackéus, 2015). Within this context, entrepreneurship education stands out as a formative approach that promotes creativity, critical thinking, leadership, and social value creation, thereby contributing to the transformation of both local communities and institutional environments.

Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) have been implemented in diverse contexts, with the aim of equipping individuals for market participation, fostering innovation, and contributing to sustainable economic development. However, their outcomes may vary significantly depending on the socioeconomic environment, influenced by factors such as culture, educational infrastructure, and public policy frameworks (Kuratko, 2005). Furthermore, several challenges persist, including the need for ongoing teacher training. The adaptation of programs to local contexts and the integration of EEPs into public policy initiatives to enhance their scalability and long-term impact. Moreover, international studies have shown that the success of EEPs is strongly influenced by both cultural and institutional variables, underscoring the necessity of tailoring these programs to meet both local realities and global expectations. The approach proposed by Lackéus (2015) significantly contributes to expanding the understanding of entrepreneurship education as a pedagogical practice aimed at inclusion, motivation, and the development of competencies applicable to students’ social and professional lives. By introducing the concept of learning-by-creating-value, the author emphasizes that entrepreneurship education is not limited to the creation of businesses but rather, it involves the capacity to generate value for others in various social contexts. This perspective reinforces the role of entrepreneurship education as a strategy for social engagement and transformation, especially when integrated into the curriculum through active methodologies and interdisciplinary projects.

While entrepreneurship education and social entrepreneurship share common ground, such as the promotion of innovation and contributions to economic development, they are conceptually distinct. Entrepreneurship education refers to the process of developing knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable individuals to participate in the market, whether by creating new ventures or managing existing businesses (Kuratko, 2005). Social entrepreneurship, on the other hand, is characterized by the pursuit of innovative solutions to social problems, aiming to generate measurable social impact while maintaining financial sustainability (Oliveira, 2004; Esteves, 2011). Although entrepreneurship education can support the development of social entrepreneurs, its scope is broader, encompassing the preparation of individuals for both socially oriented initiatives and traditional business activities across diverse economic contexts.

Despite advances in research on entrepreneurship education in recent decades, significant gaps remain in understanding the true impact and effectiveness of these initiatives, particularly in diverse social and institutional contexts (Jardim et al., 2021). The literature often presents descriptive accounts that emphasize the implementation of Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs), but lacks deeper analyses of how and under what conditions these programs effectively contribute to the development of social entrepreneurship and to socioeconomic inclusion (Esteves, 2011; Limeira, 2015). Terms such as “impact” and “effectiveness” are used broadly and imprecisely, without clearly defining the indicators employed—whether social, economic, or educational which hampers comparisons between studies and limits the ability to guide more effective educational practices (Limeira, 2015). Furthermore, many previous studies suffer from fragmented referencing, which weakens the cohesion and clarity of central arguments, signaling a need for more integrated and critical approaches to literature analysis.

Furthermore, previous studies have focused predominantly on developed countries and innovation-driven universities, leaving local dynamics in peripheral or socially vulnerable contexts underexplored (Wang & Yee, 2023). These gaps hinder the alignment between academic output and the actual demands of more inclusive educational policies that are sensitive to structural inequalities (Esteves, 2011). In this regard, it is essential to understand which pedagogical practices, institutional policies, and contextual conditions enhance the effects of EEPs in training social entrepreneurs and promoting socioeconomic inclusion (Jardim & Sousa, 2023).

Given this scenario, the central research question guiding this study is: How have Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) been framed in the scientific literature regarding their capacity to promote social impact, economic development, and institutional transformation, considering their multiple formative and contextual dimensions?” To guide this investigation, the following research questions were formulated: (i) How are EEPs represented in academic literature in terms of their structure, goals, and implementation strategies? (ii) To what extent do EEPs contribute to social entrepreneurship and socioeconomic inclusion? (iii) What challenges and best practices are identified in the literature regarding EEP implementation across different contexts? (iv) How do EEPs align with the broader mission of entrepreneurial universities, particularly concerning social engagement and innovation?

This is an analytical bibliographic review based on the selection and critical analysis of a representative set of studies on EEPs, with special attention to their interface with social entrepreneurship and socioeconomic inclusion. The research does not aim to exhaust the available knowledge on the subject but rather to highlight conceptual and practical gaps identified in the literature, such as the absence of consistent criteria for measuring impact and effectiveness across different contexts, especially in regions of social vulnerability.

The review followed an analytical narrative approach. The selection of studies was based on relevance, recurrence, and analytical depth, focusing on publications that explored the relationship between EEPs, social entrepreneurship, and socioeconomic inclusion. The sources were identified through searches in academic databases such as Google Scholar, CAPES Platform, SciELO, Scopus, and Web of Science. The studies were examined through interpretative reading and categorized into seven analytical dimensions, which were aligned with the research questions and the conceptual framework. Procedural details are provided in Section 3 (Materials and Methods).

The methodology was defined prior to the literature analysis and appears in the next section, in accordance with academic standards, contributing to greater transparency and structural coherence. Based on this review, the study seeks to identify conceptual and empirical gaps and propose future pathways for the improvement of EEPs in diverse realities, especially regarding socioeconomic inclusion and sustainability.

Specifically, this study aims to (i) examine how EEPs are addressed in the scientific literature; (ii) highlight best practices and challenges associated with EEP implementation; (iii) identify gaps and opportunities for enhancing EEPs across different contexts; and (iv) analyze how the academic literature has addressed the role of EEPs in promoting inclusion, innovation, and regional development, especially in relation to the expanded mission of entrepreneurial universities. Although the proposed research question addresses a broad field, this study limits its scope to the critical analysis of academic literature, and does not aim for empirical generalization, focusing on how EEPs are discussed and structured in terms of social impact, with particular emphasis on the Brazilian context in the sections related to social entrepreneurship. In doing so, the study also seeks to improve the conceptual integration between the reviewed literature and the analytical goals proposed, ensuring argumentative fluency and cohesion.

This research is warranted by the significance of entrepreneurship education as a mechanism for fostering social inclusion, innovation, and economic development. It assumes that EEPs, when integrated into institutional strategies for social impact, can drive meaningful transformations in educational and social contexts. The enhancement of EEPs can contribute to expanding training opportunities, reducing inequalities, and strengthening the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Furthermore, by synthesizing and analyzing existing knowledge, this study aims to provide valuable insights for educators, administrators, and policymakers, positioning entrepreneurship education as a key element in addressing contemporary socioeconomic challenges.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Entrepreneurship Education

Entrepreneurship Education can be understood as an intentional pedagogical process aimed at developing entrepreneurial competencies, skills, and attitudes in individuals—such as creativity, initiative, autonomy, critical thinking, and problem-solving abilities—with a view to generating value in various contexts, whether economic, social, or cultural (Kuratko, 2005; Lackéus, 2015), with a view to generating value in economic, social, and cultural settings, thus contributing to both individual empowerment and collective development.

This concept underpins the central analytical focus of this study, which investigates how Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) are positioned in the academic literature regarding their social and institutional impacts. Rather than treating entrepreneurship education as a generic training tool, this section emphasizes its multidimensional role in promoting innovation, inclusion, and transformation within higher education.

Building on this perspective, entrepreneurship education has established itself as a legitimate and essential field in developing future entrepreneurs, becoming the subject of extensive academic research and theoretical discourse. According to Kuratko (2005), entrepreneurship education has gained significant academic recognition, sparking discussions about best practices for fostering entrepreneurial behavior in educational settings. Politis (2005) argues that formal entrepreneurship training and education alone do not significantly impact the development of entrepreneurial knowledge, emphasizing instead the importance of transversal skills such as creativity and critical thinking.

In light of the economic and technological transformations of the 21st century, entrepreneurial education has gained relevance as a formative strategy and is increasingly being integrated into educational policies around the world. Jardim and Sousa (2023) highlight that the emphasis on competencies such as creativity, critical thinking, and autonomy has driven the integration of entrepreneurial practices at various levels of education. In line with this, Jardim (2021) proposes a tripartite model of entrepreneurial competencies—openness to novelty, solution creation, and effective communication—as a foundation for training innovative and resilient professionals capable of succeeding in a highly digitalized labor market.

Such models contribute to theoretical consistency by offering analytical categories that support the evaluation of EEP effectiveness, particularly in relation to the development of socially oriented entrepreneurial capacities. They also enable this study to critically examine the extent to which these competencies are reflected in the design and implementation of EEPs across different contexts.

In this context, international studies reveal that perceptions of entrepreneurship vary according to cultural and economic environments. According to the OECD (2017), countries such as the United States, Canada, Norway, Denmark, Mexico, Brazil, and Indonesia report a high perception of entrepreneurial opportunities, whereas Greece, Spain, and Portugal show greater self-confidence than actual perception of opportunities. Japan and South Korea report low levels in both areas. In Finland, Ranta et al. (2022) found that future teachers express interest in entrepreneurship and financial education but report low self-efficacy in teaching these subjects. Jardim et al. (2021) reinforce that, despite the effectiveness of EEPs, cultural factors still limit their full implementation, highlighting the importance of interdisciplinary strategies that are sensitive to local realities.

These findings reinforce the argument that EEPs must be interpreted not as standardized interventions, but as pedagogical strategies requiring contextual adaptation. This directly relates to the analytical dimension of this study that seeks to identify challenges and best practices in the literature.

According to the United Nations (UN), sustainable development refers to development that meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (United Nations, 1987). Entrepreneurship thus stands out as a key driver of sustainable economic and social development (Kauffman Foundation, 2014). Research has highlighted the importance of investing in entrepreneurial skills to foster local development. By linking entrepreneurship education to the broader agenda of sustainable development, this study integrates a cross-cutting perspective that aligns with its central research question regarding the transformative potential of EEPs in promoting socioeconomic inclusion.

Entrepreneurial skills are not only essential for the entrepreneur’s success but also for generating positive outcomes within communities. In this context, Nabi et al. (2017; see also Rideout & Gray, 2013) emphasize that Entrepreneurial Education (EE) can be seen as a crucial tool to accelerate the process of shaping individuals into entrepreneurs. However, the authors highlight the need for better structuring of the formative stages, as well as for studies that demonstrate the efficiency and effectiveness of Entrepreneurial Education Programs, both in theoretical and practical aspects. Furthermore, they point out the mixed and method-dependent nature of current evidence, indicating that there is still considerable progress to be made in enhancing entrepreneurial education in both its theoretical and applied approaches. However, the lack of these skills can pose a significant barrier to business development and sustainability.

This critical observation aligns with the goals of the present study, which seeks to identify both strengths and persistent gaps in the design, execution, and evaluation of EEPs, especially regarding their contribution to inclusive and sustainable development.

In line with this, Krüger et al. (2019) argue that entrepreneurship education plays a vital role in helping students develop expertise in specific fields, which may ultimately contribute to a country’s economic and social development. This contribution may lead to the implementation and expansion of educational initiatives in high schools and universities. These authors provide an important foundation for the analytical dimension of this study related to the opportunities for improvement in EEPs, particularly by integrating field-specific competencies with broader societal goals.

Cope (2005) emphasize that entrepreneurship education should be understood as a dynamic process encompassing awareness, knowledge integration and application, and the transformation of experiences into practical outcomes. In this regard, they argue that entrepreneurship is not an innate characteristic, but rather a competency that develops throughout one’s education, particularly during higher education. To achieve this, a structured pedagogical plan is essential, one that fosters entrepreneurship through various activities including lectures, assigned readings, case studies, company visits, simulations, and group projects. This dynamic and experiential view supports the premise that EEPs should go beyond knowledge transmission, functioning as platforms for applied learning that foster entrepreneurial identity and action, especially in vulnerable contexts.

Therefore, entrepreneurship education, as described by Krüger et al. (2019) and grounded in Cope’s (2005) perspective, emerges as a key element in developing entrepreneurial skills during academic training. By integrating theory and practice more effectively, this approach equips students to address economic and social challenges while contributing to the development of inclusive and innovative ecosystems.

Thus, entrepreneurial education emerges as an essential component not only for the development of innovative individuals but also for the strengthening of sustainable and inclusive ecosystems. The reviewed studies highlight that its success depends on the articulation between theory and practice, sensitivity to cultural contexts, and the encouragement of transversal competencies. In a global scenario marked by technological transformations and socioeconomic challenges, investing in entrepreneurial education becomes a decisive strategy to foster development, equity, and innovation.

These reflections reinforce the conceptual basis of this study by linking entrepreneurship education to broader societal challenges and emphasizing the need for EEPs to be context-sensitive and socially responsive.

A longitudinal study by Oksanen et al. (2023) conducted with 309 basic education teachers in Finland identified three engagement profiles with EE—experimenters, critics, and selective adopters—and emphasized the importance of institutional support and conceptual clarity for the effective implementation of entrepreneurial practices. Although focused on basic education, the findings offer valuable insights applicable to higher education, especially in initiatives oriented toward social inclusion and social entrepreneurship.

Such findings underscore the analytical dimension related to inclusion and diversity explored in this review, providing empirical evidence that institutional culture and clarity of purpose significantly influence the effectiveness of EEPs.

2.2. International Trends and Innovative Experiences of Entrepreneurial Universities

The rise of entrepreneurial universities, as analyzed by Etzkowitz (2003), represents an institutional reconfiguration that goes beyond the traditional functions of teaching and research. In this model, the university takes on an active role within the innovation ecosystem, collaborating with government and the productive sector. Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) are positioned within this context as strategic instruments of the university’s “third mission” by fostering entrepreneurial competencies, facilitating knowledge transfer, and promoting socioeconomic inclusion, thereby reinforcing the capacity of higher education institutions to generate social impact and regional development.

Although the Singaporean experience illustrates the potential of this model, evidence from other regions suggests that its impact varies depending on the context. For example, in Singapore, the National University (NUS) exemplifies this transition by playing an active role in innovation and knowledge commercialization through patents, spin-offs, and technological partnerships (Wong et al., 2007). According to Etzkowitz (2003), this movement broadens the traditional mission of universities by integrating teaching, research, and entrepreneurship. However, its impact varies depending on the context: it tends to be more effective in fragile ecosystems (Pita et al., 2021), requiring changes in management and interaction with external stakeholders to maintain relevance in more developed environments (Klofsten et al., 2019). These findings underline that the entrepreneurial university model must be adapted to different regional and institutional realities to maximize its transformative potential.

The experience of Glasgow Caledonian University in Scotland illustrates how EEPs can operationalize the expanded mission of the entrepreneurial university. Smith et al. (2017) focused on employability, entrepreneurship, and social value creation, demonstrating how such initiatives combine pedagogical innovation with public policies aimed at expanding access to higher education. In this case, the university acts as a coordinating agent between education, social impact, and regional development, in alignment with the principles of the Triple Helix model.

Studies highlight the strategic role of entrepreneurial universities in regional economic development. In the United Kingdom, Guerrero et al. (2015) show that these institutions generate impact through teaching, research, and entrepreneurship, with variations according to institutional profiles: while traditional universities excel in knowledge transfer, research-intensive institutions, such as those in the Russell Group, are more focused on spin-offs. This diversity suggests that institutional specialization is a key element in maximizing the entrepreneurial impact of universities within their regional ecosystems.

Complementarily, Audretsch and Keilbach (2008), based on data from German regions, argue that entrepreneurship acts as a spillover channel for knowledge, fostering regional growth by transforming discoveries into applied innovations. This reinforces the importance of fostering entrepreneurial mindsets not only within universities but also across the broader regional innovation systems.

Forliano et al. (2021) conducted a bibliometric analysis of 511 publications on entrepreneurial universities in the fields of business and management, identifying three core areas: knowledge and innovation management, performance and economic growth, and technology transfer. Although interest in the topic has increased in recent decades, scientific production remains fragmented, reinforcing the need to expand research in developing countries and promote international collaborations. This fragmentation highlights significant opportunities for future studies, particularly in underexplored geographical regions.

Supporting this perspective, Bramwell and Wolfe (2008), in their study of the University of Waterloo in Canada, emphasize that the impact of entrepreneurial universities goes beyond commercializable research. It includes initiatives such as cooperative education, intellectual property policies, and technical support to industry, all of which strengthen tacit knowledge transfer, talent attraction, and regional development. These initiatives illustrate how entrepreneurial universities can contribute not only to economic innovation but also to strengthening human capital and knowledge ecosystems.

Recent studies highlight different dimensions of the role played by entrepreneurial universities. Kalar and Antoncic (2015), in their analysis of four European universities—Amsterdam, Antwerp, Ljubljana, and Oxford—found that academics who perceive their departments as highly entrepreneurial are more likely to engage in activities such as patents, licensing, and industry collaboration. These academics also show less resistance to the integration of science, innovation, and entrepreneurship. This suggests that fostering an entrepreneurial organizational culture is critical to encouraging academic engagement with innovation.

In the North American context, O’Shea et al. (2005) analyzed the performance of universities in generating technology-based spin-offs and identified that factors such as faculty quality, focus on science and engineering, and the institution’s commercial capacity are key determinants of success. Institutions like MIT stand out for their strong entrepreneurial culture and significant regional economic impact. These findings confirm that institutional capabilities and strategic focus play decisive roles in the success of entrepreneurial initiatives.

Nevertheless, despite the successes observed, some studies reveal significant internal challenges. On the other hand, Philpott et al. (2011) examine how the concept of the entrepreneurial university manifests in a comprehensive European institution, revealing internal tensions among different academic disciplines. The study shows that enforcing the entrepreneurial mission through top-down approaches can paradoxically reduce entrepreneurial activity among faculty. Furthermore, the authors highlight a division of attitudes across fields of knowledge, which can lead to institutional disharmony. In discussing the development of the entrepreneurial university, they challenge Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff’s (2000) proposition that this model follows an isomorphic, or uniform, path of evolution across institutions and contexts.

Rasmussen and Sørheim (2006) analyzed five Swedish universities and highlighted the transition from traditional entrepreneurship education, centered on classroom theory, to more practical and collaborative approaches based on learning by doing. These initiatives involve strong engagement with regional actors and focus on training entrepreneurs, fostering new business creation and the commercialization of university research. Complementarily, Shirokova et al. (2016), using data from the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey (GUESSS), emphasize that while entrepreneurial intention is a key driver of action, its realization depends on variables such as age, gender, family background, university environment, and uncertainty avoidance. Both studies underscore that the effectiveness of entrepreneurial education programs is linked not only to the methodology employed but also to the individual and contextual conditions that shape students’ paths toward entrepreneurship.

In light of the challenges posed by knowledge-based economies, entrepreneurial education and the entrepreneurial university model have increasingly become global strategies for promoting innovation, regional development, and competitiveness. Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) have emerged as practical expressions of this model, reflecting the university’s expanded role beyond traditional teaching and research. According to Etzkowitz (2003), the entrepreneurial university transcends conventional academic functions by integrating science, markets, and society into innovative institutional arrangements.

Evidence from countries such as Singapore, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, and Brazil demonstrates that the success of these initiatives relies on the integration of teaching, research, entrepreneurship, and institutional policies tailored to local contexts. The literature reveals significant advances—from innovative pedagogical practices to the creation of spin-offs and the strengthening of regional networks. However, it also points to limitations such as fragmented scientific production, internal tensions within institutions, and cultural barriers to full implementation. These findings underscore the role of EEPs as strategic instruments aligned with the university’s third mission—generating social and economic impact through education and innovation. This reinforces the need for integrated, interdisciplinary, and context-sensitive approaches that enhance the transformative role of universities within the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Future research should particularly focus on identifying context-specific success factors and designing adaptive strategies that respect institutional diversity.

2.3. Analyzing the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs

The effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) has received increasing attention in the scientific literature, particularly in light of the challenges posed by knowledge-based economies and the need to foster innovation, inclusion, and sustainable development through education. This has led to growing scholarly interest in how these programs are structured, delivered, and assessed. Researchers have examined various dimensions of these programs, from their implementation in higher education to their adaptation to diverse school contexts, with emphasis on the development of entrepreneurial competencies, teacher training, and curriculum integration. This multiplicity of approaches reflects the complexity involved in the design and operationalization of EEPs, whose impacts vary according to institutional, cultural, and regional contexts. This section analyzes different contributions from the academic literature, focusing on practices, challenges, and outcomes of EEPs, aiming to identify critical elements for their improvement and expansion.

Jardim et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review examining Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) across different regions of the world, analyzing their key characteristics and impacts on the development of entrepreneurial skills. The literature review, drawing from articles indexed in databases such as Scopus and Web of Science, revealed that most entrepreneurship programs targeted higher education students, emphasizing business plan development and entrepreneurial skills training. However, the authors identified a significant gap in teacher training for entrepreneurship education, emphasizing the need for initiatives that integrate this subject matter from the early school years, a crucial period for developing entrepreneurial predispositions (Jardim et al., 2021). They emphasize that the early school years are a critical stage for nurturing entrepreneurial predispositions.

Valenciano Sentanin and Barboza (2005) examined the growth of entrepreneurship in Brazil, emphasizing its critical role in business survival and success within an environment where innovation and adaptability are essential. These authors emphasize that entrepreneurship demands not only technical expertise but also the ability to channel passion into effective action. The findings presented in this study suggest that most individuals work in fields misaligned with their genuine interests, contributing to high business failure rates across the country. Furthermore, it emphasizes the significance of market research as a vital tool enabling entrepreneurs to better understand their operating environment, facilitating continuous adaptation and innovation to ensure business growth and sustainability (Valenciano Sentanin & Barboza, 2005).

Barbosa’s (2012) study examines the development and significance of entrepreneurship education in fostering a more innovative society, emphasizing the role of education in youth skill development. Using a descriptive methodology, this research examines effective approaches to incorporating entrepreneurship into the educational system, ensuring students acquire the essential skills needed for creating and managing new business ventures. Furthermore, the author emphasizes the need for innovative pedagogical practices that transcend traditional teaching models, equipping young people with tools to excel in a competitive market and contribute to Brazil’s economic and social development (Barbosa, 2012).

Kuratko (2005), Lackéus (2015), as well as recent evidence in engineering (Santos et al., 2023; Teixeira et al., 2021) converges emphasize the significance of entrepreneurship education within Industrial Engineering, highlighting universities’ crucial role in developing professionals capable of creating new business ventures. This research examines the integration of entrepreneurship education into academic curricula, fostering both technical skills and essential managerial skills required in today’s market. They argue that entrepreneurship education should not be limited to technical content but must also stimulate creativity, innovation, and risk-taking. The authors emphasize that higher education institutions play a strategic role in creating an environment conducive to innovation by fostering an entrepreneurial culture among students. The literature identifies various approaches to entrepreneurship education, emphasizing the need for an educational model that transcends the mere transmission of technical knowledge. This model should foster creativity, risk-taking ability, and innovation, thereby preparing students for market challenges (Kuratko, 2005; Lackéus, 2015; Santos et al., 2023; Teixeira et al., 2021).

Several studies have examined the significance and effects of entrepreneurship education across various contexts, emphasizing the need to incorporate such instruction throughout the educational pipeline, from early education through higher learning. Valenciano Sentanin and Barboza (2005) discuss the importance of fostering an entrepreneurial mindset in Brazil to address high business failure rates.

Other studies emphasize the importance of educational methodologies for entrepreneurship. Barbosa (2012) emphasizes the importance of pedagogical strategies that prepare young people for a competitive market through entrepreneurship education. Furthermore, studies in engineering indicate that universities should foster an entrepreneurial culture by incorporating managerial and entrepreneurial skills into Industrial Engineering curricula (Santos et al., 2023; Teixeira et al., 2021). Collectively, these studies underscore the importance of implementing a holistic approach tailored to diverse educational levels and regional contexts, aimed at promoting innovation and sustainable economic development.

The literature review on entrepreneurship education emphasizes its crucial role as a catalyst for economic development and social innovation. The analyzed studies demonstrate the critical need to incorporate entrepreneurship education across all educational levels, from early formative years through higher education, to develop robust entrepreneurial skills. Furthermore, proper teacher training is essential for the effective transmission of entrepreneurial knowledge.

By fostering an entrepreneurial culture that encourages innovation and risk-taking, educational institutions can play a pivotal role in shaping future leaders who are capable of making positive contributions to society. Therefore, implementing entrepreneurship-focused educational strategies not only equips young people with the tools to navigate labor market challenges but also promotes sustainable economic development and addresses social issues through innovative initiatives.

The literature highlights that, in order to maximize the effectiveness of EEPs, it is necessary to go beyond technical training and adopt an integrated pedagogical approach that combines managerial competencies, innovation, and social values. Teacher training emerges as a critical factor, as does the adaptation of programs to regional realities. Collectively, the studies suggest that EEPs can play a strategic role in building entrepreneurial ecosystems and strengthening sustainable economic development, provided they are implemented in a context-sensitive manner and supported by continuous institutional commitment. This requires sustained policy support, tailored teacher training, and pedagogical flexibility to respond to diverse educational and socioeconomic conditions.

2.4. Social Entrepreneurship

Although this study adopts an international perspective in analyzing Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) and entrepreneurial universities, a national focus was chosen for the section dedicated to social entrepreneurship. This methodological decision stems from the uniqueness of Brazilian experiences, characterized by specific dynamics of inclusion, informality, solidarity economy, and the engagement of vulnerable communities. The Brazilian context presents a distinctive combination of structural deficiencies, grassroots social innovation, and fragmented public policies, which calls for a situated and context-sensitive analysis.

Moreover, although the national scientific literature on the topic is expanding, it still lacks critical organization, reinforcing the importance of mapping and critically examining these experiences through a contextualized lens. This approach aligns with the article’s objective of articulating social impact, educational practices, and institutional transformation based on concrete experiences of social entrepreneurship in Brazil.

The study by Godói-de-Sousa et al. (2011) examines the complexity of social entrepreneurship in Brazil, demonstrating its capacity to generate both economic and social value through Solidarity Economic Enterprises (SEE). Using a quantitative approach, this study analyzed a comprehensive sample of 21,859 SEE, revealing that while these initiatives are primarily driven by the need to generate income for basic needs, they do not show high performance or the typical characteristics associated with social entrepreneurship.

The study emphasizes the significance of establishing enabling environments that support the socioeconomic and political organization of vulnerable citizens, thereby contributing to sustainable local development. This overview provides a critical and necessary examination of the capabilities and limitations of SEE in the Brazilian context, highlighting the urgency to strengthen these initiatives to achieve more meaningful and lasting societal impact (Godói-de-Sousa et al., 2011).

Rodrigues dos Santos Pedroso et al. (2021) examine the intersection between social entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurial opportunities through a bibliometric analysis of the existing literature. This analysis revealed that despite growing academic interest in social entrepreneurship, publications remain relatively scarce and recent, with limited representation in Brazil.

The authors identified a significant research gap, indicating that the field of social entrepreneurship remains in its nascent stages and presents substantial opportunities for future research. The study emphasized that social entrepreneurial opportunities often emerge in response to institutional voids and are crucial for designing interventions aimed at social welfare (Rodrigues dos Santos Pedroso et al., 2021).

Oliveira’s (2004) study provides a comprehensive analysis of social entrepreneurship in Brazil, examining its evolution and implementation challenges. The author identifies social entrepreneurship as an emerging response to social problems, which have been exacerbated by the reduction in public investment and the increased involvement of private companies and third-sector organizations in addressing social issues.

This research highlights the prevalent conceptual ambiguity among social entrepreneurship, corporate social responsibility, and traditional entrepreneurship. The findings emphasize the need for a more precise theoretical framework that distinguishes social entrepreneurship through its unique management approach and social impact mechanisms. Oliveira (2004) argues that, despite existing challenges, social entrepreneurship in Brazil has the potential to transform the social landscape through innovative and entrepreneurial management approaches that go beyond traditional welfare practices.

Esteves’s (2011) study examines the intersection between solidarity economy and social entrepreneurship, analyzing how these approaches can foster social inclusion through employment opportunities. The author argues that while the solidarity economy seeks to establish cooperative and collaborative practices as an alternative to the shortcomings of traditional economic systems, social entrepreneurship focuses on creating businesses aimed at addressing social challenges.

In assessing these practices’ potential to transform sociability through labor, Esteves emphasizes the need for sustained critical engagement to ensure they are not co-opted by prevailing capitalist logic. The study advances our understanding of the complex and contradictory dynamics that characterize the implementation of solidarity economy and social entrepreneurship initiatives in Brazil (Esteves, 2011).

Limeira (2015) provides a comprehensive analysis of social entrepreneurship practices in Brazil, highlighting their implementation across diverse social and economic contexts. The research identifies distinctive characteristics of social entrepreneurship, including responsiveness to emerging social needs, innovation-driven orientation, and the creation of sustainable social impact.

Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of collaborative environments between public, private, and non-profit sectors in fostering social entrepreneurship initiatives. The analysis also addresses key challenges faced by the sector, particularly financial sustainability and the need for clearer conceptual boundaries to distinguish social entrepreneurship from other business and social initiatives. Limeira (2015) suggests that strengthening this field can be achieved through more effective public policies and practice-oriented educational strategies.

Several studies have examined the scope and impact of social entrepreneurship in Brazil, highlighting both its transformative potential and the challenges it faces. Godói-de-Sousa et al. (2011) examine the contribution of Solidarity Economic Enterprises to local development, while Rodrigues dos Santos Pedroso et al. (2021) highlight the limited literature on the subject and the emergence of social entrepreneurial opportunities in response to institutional voids.

Oliveira (2004) examines the evolution of social entrepreneurship against the backdrop of declining public investment, emphasizing the need for a more precise definition to distinguish it from other business practices. Esteves (2011) examines the role of solidarity economy and social entrepreneurship in promoting social inclusion, while Limeira (2015) highlights the importance of collaboration among public, private, and third sectors in strengthening these initiatives in Brazil.

Collectively, these studies provide a comprehensive understanding of how social entrepreneurship can address emerging challenges and contribute to innovative management approaches that transcend traditional welfare practices. The findings indicate that more robust public policies and enhanced educational practices are needed to ensure the sustainable development of social entrepreneurship in the country.

Research on social entrepreneurship in Brazil reveals a diverse landscape of initiatives and challenges, highlighting this field’s capacity to drive meaningful social change through innovation and community engagement. The analyses reveal the emergence of practices that address gaps left by both state and private sectors while promoting inclusion and sustainable development in vulnerable communities.

However, there remains a need for a more precise conceptual definition and practical implementation strategies to enable social entrepreneurship to reach its full potential. To achieve this, it is essential to strengthen collaboration among public, private, and non-profit sectors, while promoting robust public policies and structured entrepreneurship education, ensuring both sustainability and immediate impact of these initiatives.

While social entrepreneurship in Brazil faces considerable challenges, its transformative potential remains undeniable. Overcoming structural barriers requires collaboration among government, private sector, and non-profit organizations, alongside effective public policies that promote their sustainability. Entrepreneurship education also plays a vital role in empowering individuals to develop innovative solutions with meaningful social impact. The ongoing commitment of all stakeholders is essential for strengthening this ecosystem, ensuring that social entrepreneurship effectively contributes to the country’s economic development and social inclusion. Considering these contributions, the analysis points to the need to advance both in the formulation of public policies and in the consolidation of educational practices that strengthen social entrepreneurship in different contexts.

It is important to emphasize that, although social entrepreneurship has a global dimension and manifests in diverse forms across different contexts, this study deliberately limited its analysis to the Brazilian context. This choice is justified by the need to deepen the understanding of the historical, institutional, and social particularities that shape social entrepreneurship practices in the country, especially regarding public policies, solidarity economy experiences, and responses to gaps left by the State and the market. Nevertheless, it is recognized that future research should expand the dialogue with international perspectives and emerging theories on the topic, exploring comparative approaches and evaluation models that account for multiple cultural and institutional realities, as highlighted by Wang and Yee (2023), who emphasize the need to overcome theoretical decentralization and to incorporate sociological, institutional, and performance-based approaches into the field of social entrepreneurship.

Moreover, achieving greater impact and long-term sustainability in this field requires strengthening intersectoral cooperation, developing clear regulatory frameworks, and expanding investment in entrepreneurship education with a focus on social innovation. In doing so, social entrepreneurship can become a strategic driver of regional development, socioeconomic inclusion, and systemic innovation. The continued commitment of all stakeholders is essential to building a resilient ecosystem that prioritizes social justice and empowers communities as active agents of change. These reflections set the stage for a broader discussion on how education, policy, and innovation can converge to unlock the full potential of social entrepreneurship.

Although this section maintains a Brazilian focus for contextual depth, we complement it with comparative evidence from developing regions. Studies in Ghana and Nigeria show that entrepreneurship education and social entrepreneurial knowledge foster social entrepreneurial intentions through psychological and resource pathways—satisfaction, self-efficacy, prosocial motivation, and perceived access to finance (Opuni et al., 2022; F. O. Peter et al., 2024). In South Asia, Hassan et al. (2022) demonstrate that entrepreneurial social networks further mediate the education–intention relationship, highlighting the role of mentoring and community-based linkages. Sub-Saharan urban cases similarly underscore state–ecosystem complementarities for scaling social innovation (C. Peter, 2021). Together with Brazilian analyses (Oliveira, 2004; Esteves, 2011; Limeira, 2015), these findings substantiate our claims while preserving a situated Brazilian lens.

In addition, evidence from Latin America offers a contrasting perspective. Montes et al. (2023), in a multi-country study with students from Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru, found that entrepreneurship education by itself did not significantly predict entrepreneurial intention, while self-efficacy emerged as the main driver. These findings underscore that entrepreneurship education, when disconnected from mentoring, networks, and ecosystem support, may be insufficient to stimulate entrepreneurial—particularly social entrepreneurial—trajectories.

Recent evidence from developing contexts reinforces the role of stakeholder engagement and multi-actor coordination in scaling social entrepreneurship initiatives. A study in Indonesia demonstrates that poverty reduction programs based on social entrepreneurship require structured collaboration between state and non-state actors, including universities, NGOs, and community organizations, to ensure sustainability and reach. The authors emphasize that interactions between formal and informal institutions can be complementary, substitutive, accommodative, or even competitive, and that these dynamics critically shape the outcomes of social entrepreneurship ecosystems (Setiawan et al., 2023). These insights highlight the importance of governance arrangements and institutional partnerships, offering relevant parallels for Latin American experiences and strengthening the international scope of this discussion.

2.5. Entrepreneurship Education and Its Relationship with Social Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship education has been widely recognized as a crucial factor in economic and social development, enabling individuals to identify opportunities, manage risks, and transform ideas into tangible actions (Kuratko, 2005). Its aim is to foster the development of skills for both new venture creation and effective management of established enterprises. Thus, entrepreneurship education programs (EEP) play a strategic role in strengthening entrepreneurial culture and fostering innovative practices.

While entrepreneurship education and social entrepreneurship share common elements, such as fostering innovation and sustainable development, they remain distinct conceptual frameworks. Entrepreneurship education focuses on teaching the skills and knowledge required to undertake ventures across all sectors, encompassing both the creation of profitable businesses and the enhancement of existing organizational processes (Politis, 2005; Krüger et al., 2019). Social entrepreneurship, in turn, focuses on developing solutions to social and environmental challenges while striving to balance social impact with financial sustainability (Oliveira, 2004; Esteves, 2011).

Thus, while entrepreneurship education provides the theoretical and practical foundation for developing entrepreneurs across various contexts, social entrepreneurship represents a specific application of this knowledge, focused on initiatives that generate societal benefits. According to Krüger et al. (2019), entrepreneurship education plays a vital role in social business development by providing tools that enable social entrepreneurs to design more effective and sustainable business models.

Research suggests that entrepreneurship-focused educational programs can foster social initiatives when designed to incorporate social impact values, ethics, and sustainable innovation (Rodrigues dos Santos Pedroso et al., 2021). In this context, entrepreneurship education extends beyond preparing individuals for competitive markets—it can serve as a crucial catalyst for strengthening social entrepreneurship by fostering innovative solutions to socioeconomic challenges.

However, as Limeira (2015) point out, there are still gaps in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and social entrepreneurship, particularly regarding the integration of social impact content into traditional entrepreneurship curricula. The incorporation of active learning methodologies, case studies, and practical experiences focused on social contexts can effectively bridge these two approaches while maximizing their societal impact.

Therefore, understanding how these concepts intersect is essential for developing more effective educational strategies. While entrepreneurship education expands opportunities for innovation and economic development, social entrepreneurship channels this knowledge toward addressing societal challenges, fostering structural changes that contribute to a more equitable and sustainable society.

Entrepreneurship education represents a dynamic and continuously evolving field of study, marked by significant contributions from various researchers over the years. Studies in the field highlight both the positive impact of Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEP) and the challenges and gaps that still need to be addressed. Furthermore, social entrepreneurship has gained prominence due to its potential to foster social inclusion and sustainable development, thereby expanding the impact of entrepreneurship education.

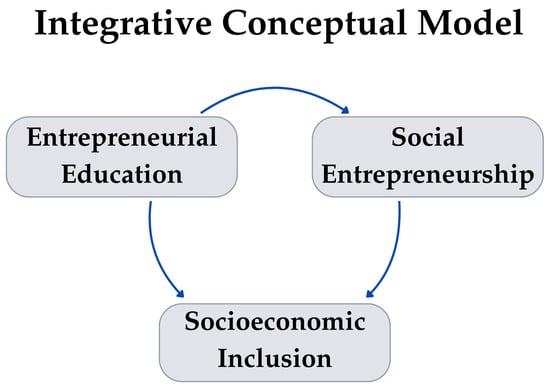

2.6. Conceptual Model: Entrepreneurial Education, Social Entrepreneurship, and Socioeconomic Inclusion

Based on the literature reviewed, this study proposes an integrative conceptual model that articulates three central dimensions of the research: (1) entrepreneurial education, (2) social entrepreneurship, and (3) socioeconomic inclusion (Figure 1). The model is grounded in the assumption that Entrepreneurial Education Programs (EEPs), when structured with active methodologies, ethical values, and impact-oriented approaches, can generate transformative effects in both the economic and social spheres.

Figure 1.

Integrative conceptual model.

Entrepreneurial education is understood as a formative process aimed at developing transversal competencies—such as creativity, leadership, and problem-solving—and at strengthening a culture of innovation. When applied in contexts sensitive to social inequalities, this educational foundation can foster social entrepreneurship, characterized by initiatives focused on addressing public issues with an emphasis on equity, social justice, and sustainability (Krüger et al., 2019; Rodrigues dos Santos Pedroso et al., 2021; Esteves, 2011).

This linkage materializes through mediating factors such as: (i) integration with public policies (Limeira, 2015); (ii) adequate teacher training (Jardim et al., 2021); (iii) engagement of community actors (Esteves, 2011); and (iv) cross-sectoral support among government, the third sector, and the private sector (Rodrigues dos Santos Pedroso et al., 2021). The ultimate outcome of this process is socioeconomic inclusion, understood as the increased participation of historically marginalized groups in local development and the formal economy, thereby promoting sustainable social transformation.

Thus, this conceptual model contributes to the visualization of the theoretical interrelations guiding this research, providing a foundation for future empirical studies to validate the proposed pathways and to further explore the contextual determinants influencing this relationship.

Our conceptual model synthesizes the main theoretical dimensions that underpin this research, articulating the relationship between entrepreneurial education, social entrepreneurship, and socioeconomic inclusion. Based on this structure, the analysis seeks to identify, within the reviewed literature, the practices, impacts, and challenges of Entrepreneurial Education Programs (EEPs) across different contexts. This theoretical framework guides the critical interpretation of the findings, structuring the connection between the research axes and the gaps identified in the scientific literature.

3. Materials and Methods

Design and reporting approach. We conducted a narrative (non-systematic) review with a two-stage screening and a theoretical sufficiency stopping rule. Our study adopts a narrative literature review with analytical interpretive approach based on the methodological guidelines of Lakatos and Marconi (2017) and Cervo et al. (2007), who define literature review as a method grounded in the critical analysis of previously published theoretical contributions, aiming to deepen the understanding of a specific object of study. We do not claim exhaustiveness or apply PRISMA-style protocols; instead, we provide transparent reporting adequate to a narrative review. Additionally, we followed general guidance for preparing and reporting review articles, emphasizing scope delimitation, procedural transparency, and critical synthesis (Murphy, 2012). Consistent with Sukhera (2022), we treat narrative reviews as interpretive syntheses suited to integrating heterogeneous evidence and contextual perspectives, while maintaining rigor and transparent reporting throughout selection and synthesis. In this case, the focus is on Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs), with an emphasis on their dynamics, impacts, challenges, and contributions to social inclusion and economic development.

In this study, Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) are understood as formal or curriculum-integrated initiatives aimed at developing competencies such as creativity, initiative, critical thinking, and problem-solving (Kuratko, 2005; Jardim et al., 2021). These programs include specific courses, interdisciplinary projects, and active methodologies, primarily applied in higher education, with an emphasis on business creation and the promotion of social entrepreneurship Consistent with this lens, we prioritize studies that explicitly link pedagogy to competence development and value creation.

The adopted conception follows Lackéus’s (2015) proposal, which defines entrepreneurship education as a learning process through the creation of value for others in real social contexts. From this perspective, this study considers as EEPs all formal or complementary educational practices aligned with institutional pedagogical objectives that contribute to entrepreneurial training with social, economic, or community impact. Although this is a literature review, the study adopts an empirical stance by analyzing previously published scientific sources that report primary data. The aim is to analytically examine existing evidence on EEPs, their dynamics, impacts, and contributions, while ensuring methodological rigor and scientific validity.

The literature search was conducted using the databases Google Scholar, CAPES Platform, SciELO, Scopus, and Web of Science, focusing on publications in Portuguese and English (with occasional inclusion of Spanish when pertinent). To balance recency and theoretical grounding, we privileged the 2014–2025 window for contemporary discussions while retaining seminal works outside this range when conceptually indispensable. The following descriptors and equivalent expressions were used: “entrepreneurship education”, “entrepreneurship education programs”, “entrepreneurial university”, “social entrepreneurship”, and “entrepreneurial training.” Illustrative Boolean strings included: (“entrepreneurship education” OR “entrepreneurial education”) AND (“higher education” OR university) AND (“social entrepreneurship” OR inclusion OR “community impact”); and (“educação empreendedora” OR “programas de educação empreendedora”) AND (universidade OR “ensino superior”) AND (social OR inclusão). We complemented database queries with backward/forward citation tracking (“snowballing”) to surface theoretically relevant studies not captured initially. It is important to note that this reference was used solely to guide the exploratory organization of the search process.

All sources used in this study are peer-reviewed articles that addressed entrepreneurship education in higher education, particularly those connected to the institutional mission of universities and focused on socially oriented practices. Eligible publications could be empirical or conceptual, provided they engaged EEPs in higher education, competency development, and links to social value creation/inclusion.

Studies on basic education were also considered when they presented relevant conceptual or methodological contributions transferable to higher education, as in the case of the work by Ruskovaara et al. (2015).

Opinion pieces, editorials, news reports, and studies focusing exclusively on secondary or technical education without connection to formal or university-level educational practices were excluded. We also excluded purely operational/technical reports with no explicit connection to entrepreneurial competences or social purpose.

The selection of sources was guided by relevance and quality criteria, prioritizing journals specialized in educational policy, pedagogical innovation, and teacher training—essential fields for analyzing EEPs as institutional practices. Both national and international publications were included, some of which were published prior to the most recent period, to contextualize the conceptual evolution of entrepreneurship education. Screening occurred in two stages (titles/abstracts; then full text), with duplicates removed across databases. A light-touch appraisal considered peer-review status, journal reputation, methodological clarity, conceptual coherence with the value-creation lens, and adequacy of evidence; this appraisal informed the weight of each study in the synthesis but did not operate as a rigid exclusion filter.

Given the narrative nature of the literature review, no predefined sample of articles or quantitative inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted. Instead, the selection of materials was based on the thematic alignment of the studies with the concept of entrepreneurship education adopted in this work, as defined by authors such as Kuratko (2005), and Lackéus (2015). This approach aligns with the narrative review model, in which screening is guided by theoretical relevance and contribution to the conceptual deepening of the research object. This process was conducted through exploratory reading of titles and abstracts, followed by full analytical reading of papers considered potentially contributory, until theoretical sufficiency/saturation was reached—i.e., when additional papers no longer yielded substantively new insights with respect to the research questions and analytical dimensions. Consistent with the typology of saturation models summarized by Saunders et al. (2018), our stopping rule corresponds to theoretical sufficiency/inductive thematic saturation at the level of themes and mechanisms rather than sample size.

The research questions presented in the introduction served as a reference for guiding the literature selection and for structuring the thematic dimensions developed in the Results section. Findings were organized into seven analytical dimensions following principles of clarity, mutual exclusivity, and homogeneity (Bardin, 2011; Carlomagno & Rocha, 2016).

The choice of journals such as Education Sciences, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, and Industry and Higher Education is justified by the central role these publications play in the international debate on entrepreneurship education, particularly in approaches that link pedagogical innovation and social impact. Where available, recent works (2022–2025) were prioritized to ensure up-to-date coverage, while classic references were retained for conceptual framing.

This article adopts the conceptual model of entrepreneurship education based on value creation, as proposed by Lackéus (2015), articulated with the formative dimensions described by Kuratko (2005). It is assumed that the most effective EEPs are those that integrate active pedagogical practices, social purpose, and institutional ties with higher education, promoting entrepreneurial competencies and socio-community impact.

Based on the methodological path described, the selected studies were examined using analytical criteria that enabled the thematic organization of findings through categories inspired by the principles of clarity, mutual exclusivity, and homogeneity, as recommended by Bardin (2011) and Carlomagno and Rocha (2016). We adopted a criterion of theoretical sufficiency/saturation to close the search and screening—i.e., when additional readings no longer added themes/mechanisms relevant to the analytical dimensions; this decision aligns with good practices for transparency in education (Daher, 2023) and with guidance on rigor for narrative reviews, without claiming exhaustiveness (Sukhera, 2022). This concept refers to the moment when additional literature no longer adds substantial new insights, indicating that the reviewed material adequately supports the theoretical objectives of the study.

This method allows for a flexible and in-depth exploration of the literature, guided by analytical rigor and theoretical consistency, which are particularly important in studies involving interdisciplinary and context-sensitive topics such as entrepreneurship education. No human subjects were involved; ethical approval was not required for this study.

This study is guided by the premise that EEPs, when integrated into institutional strategies for social impact, have contributed to relevant transformations in the educational and social contexts analyzed. The next section presents the main results of the review, structured into dimensions that reflect the relevance, challenges, best practices, and future prospects of Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) in the context of higher education.

To enhance methodological clarity in this narrative review, we summarize the identification, screening, and inclusion process using a textual flow rather than a PRISMA diagram (Table 1). This textual flow complements the two-stage screening and theoretical saturation procedures described above and clarifies how studies progressed from initial retrieval to inclusion.

Table 1.

Narrative review textual flow.

4. Results

The findings of this study underscore the central role of entrepreneurship education as a vehicle for social inclusion and economic development. Based on publications obtained from sources such as Google Scholar, CAPES Platform, SciELO, and renowned scientific journals, including Education Sciences, and supported by previously cited studies that highlight the strategic integration of entrepreneurship education with sustainable development goals (e.g., Kuratko, 2005; Lackéus, 2015; Ruskovaara et al., 2015), analysis of scientific publications revealed that while Entrepreneurship Education Programs (EEPs) are widely recognized as strategic tools for fostering innovation and reducing inequalities, significant challenges remain in their implementation and improvement.

As an illustrative example, Xanthopoulou and Sahinidis (2025) examined an entrepreneurship education program for tourism students in a Greek public university, where experiential activities such as business model canvas development, teamwork, and presentation of socially oriented projects significantly increased students’ social entrepreneurial intentions. This case highlights how active pedagogical practices can effectively connect entrepreneurship education to social impact, reinforcing the importance of linking empirical evidence to theoretical analysis.

National and international authors have contributed valuable evidence on the multiple dimensions, practices, and challenges of Entrepreneurial Education Programs (EEPs), enriching the understanding of the topic across diverse contexts. Rather than a merely descriptive approach, this section presents an interpretative synthesis grounded in the theoretical framework adopted, allowing critical reflection on the current state and future of EEPs. To analyze these findings, the research was structured along seven key dimensions: (1) the significance of entrepreneurship education; (2) observed best practices and challenges; (3) opportunities for improvement; (4) Institutional and Structural Challenges; (5) Inclusion and Diversity; (6) Innovation and Emerging Technologies; and (7) Future Perspectives and Integrated Public Policies, future perspectives for the area.

- Significance of entrepreneurship education: entrepreneurship education programs (EEPs) play a vital role in empowering individuals and communities, fostering opportunity creation, driving innovation, and reducing social inequalities.

Recent empirical evidence reinforces this significance: in a quasi-experimental study with 1036 secondary and vocational students in Spain, Núñez-Canal et al. (2023) showed that adding a structured entrepreneurship program to the standard curriculum led to significant gains in entrepreneurial attitudes and knowledge versus a control group, especially at more advanced levels (with no systematic differences by gender).

Furthermore, the findings demonstrate that EEPs can play a strategic role in both strengthening new business ventures and fostering social entrepreneurship. While some programs primarily focus on developing skills for the traditional job market, others aim to empower individuals to engage in social impact projects. This dual role underscores the need for differentiated educational strategies to address the diverse profiles of entrepreneurs (Barbosa, 2012; Esteves, 2011; Kuratko, 2005; Lackéus, 2015). This confirms the versatility of EEPs and their potential to serve as instruments of both economic productivity and social justice.

In a multi-country study spanning universities in Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru, the effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention was non-significant, suggesting strong context dependence and the need for comparable designs and metrics to detect effects across different ecosystems (Montes et al., 2023).

- 2.

- Best Practices and Challenges: Successful initiatives were identified that can serve as implementation models for EEPs. Studies such as Jardim et al. (2021) emphasize that the most effective programs are those that integrate theory and practice through active learning methodologies, including case studies, simulations, and collaborative projects. Furthermore, evidence from engineering programs indicates that incorporating both technical and managerial content into university curricula significantly contributes to the development of entrepreneurial skills (Santos et al., 2023; Teixeira et al., 2021). As an empirical example, Musara (2024), in a study with undergraduate students at a South African public university, showed that the systematic use of the case study method in entrepreneurship education significantly enhanced students’ perceptions of creativity, entrepreneurial knowledge, and social entrepreneurial intention. This evidence reinforces the role of active methodologies as drivers of both competence development and social impact, illustrating how contextually adapted practices can produce transformative results. However, challenges remain, including inadequate educational infrastructure and the need for better alignment between programs and local demands (Kuratko, 2005). These findings reinforce that, while successful practices exist, their scalability and long-term impact depend on institutional commitment, continuous teacher training, and adaptation to socioeconomic contexts.

In a study across three Ghanaian universities, the EE → entrepreneurial competencies relationship was fully mediated by student satisfaction and self-efficacy; this finding reinforces student-centered pedagogical practices (e.g., frequent feedback, authentic projects, and support for self-efficacy) as a pathway to translating EEPs into observable competencies (Opuni et al., 2022).

- 3.

- Opportunities for Improvement: Research on EEPs reveals strategic gaps that, if addressed, could maximize their positive outcomes. Krüger et al. (2019) demonstrate that insufficient teacher preparation in entrepreneurship education significantly constrains the effectiveness of these programs. Jardim et al. (2021) emphasize that the effectiveness of EEPs depends, among other factors, on more structured teacher training that incorporates entrepreneurship education from the early school years, thereby expanding its reach and impact. Another critical consideration is the need for enhanced public–private sector integration to foster strategic partnerships that enable program customization across diverse socioeconomic contexts (Barbosa, 2012). The literature also points out that the articulation between educational policies and entrepreneurial training practices is essential for ensuring that these initiatives are contextually relevant and capable of addressing local needs (Kuratko, 2005; Lackéus, 2015). These opportunities, if explored in a coordinated manner, can broaden the reach of the programs, ensure their adaptability, and contribute to the consolidation of a more robust and inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem. The literature suggests that expanding these initiatives requires strategic articulation among government, academia, and industry, as well as mechanisms to overcome the fragmentation and ensure alignment with local needs.

In Bangladesh, entrepreneurship education increased social entrepreneurial intention, with the effect occurring partly via entrepreneurial social networks—indicating that mentoring and institutional/ecosystem connections amplify EEP outcomes (Hassan et al., 2022). In Nigerian universities, knowledge of social entrepreneurship increased social entrepreneurial intention through mediations by pro-social motivation and perceived access to finance, signaling that curriculum design (content/experiences) and ecosystem levers (support/financing) are decisive (F. O. Peter et al., 2024).

- 4.

- Institutional and Structural Challenges: The consolidation of EEPs still faces significant institutional and structural hurdles. These include a lack of adequate infrastructure, limited resources, fragmented initiatives, and weak integration with university pedagogical projects. In many institutions, EEPs remain isolated actions without formal support to ensure their continuity and expansion (Jardim et al., 2021). The absence of specific learning environments, such as university incubators and innovation labs, and limited interaction with companies, governments, and social organizations, compromises the development of entrepreneurial competencies (Lackéus, 2015; Kuratko, 2005). Overcoming these challenges requires strengthening the institutional culture oriented toward entrepreneurship, supported by structured policies that integrate EEPs into the university’s core mission. The literature indicates that overcoming these limitations depends not only on financial investment, but also on the political will to recognize entrepreneurship education as part of the university’s strategic mission, the creation of permanent support structures (such as entrepreneurship centers and funding programs), and the establishment of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms with clear indicators and feedback loops to ensure the continuous improvement and long-term sustainability of EEPs (Barbosa, 2012).

- 5.

- Inclusion and Diversity: Despite progress, EEPs still replicate gender stereotypes and diversity barriers. Stoker et al. (2025) point out that the association between entrepreneurship and masculinity continues to limit the identification of women and other marginalized groups with the programs. Addressing this requires targeted strategies—such as mentoring programs, inclusive role models, and curriculum redesign—that integrate equity as a core principle, thereby advancing both social entrepreneurship and socioeconomic inclusion. However, there are signs of change. Educators and students have been redefining the entrepreneurial profile, broadening the notion of success beyond profit. Inclusive pedagogical practices with a critical focus and diverse representations are essential for EEPs to promote equity, belonging, and real social impact, fostering entrepreneurs aligned with values of justice and transformation. The literature (Barbosa, 2012; Esteves, 2011; Lackéus, 2015) reinforces the need for EEPs to adopt a human rights-based approach, where inclusion is not an accessory but a guiding principle.

- 6.