Psychosocial Work Factors, Well-Being, and Health Pathways to Sickness Absence: An Integrated GLM–SEM Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis

2.1. Contextual Background: Sickness Absence as a Societal and Organisational Challenge

2.2. Sickness Absence Measurement: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges

2.3. Psychosocial Risks, Subjective Well-Being, and Health: Is the Link Indirect?

2.4. The Job Demands–Resources Model as the Conceptual Framework of the Study

2.5. Hypothesis and Analytical Approach

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. Dependent Variable: Sick Leave

3.4.2. Independent Variables

3.4.3. Employees’ Subjective Well-Being

3.4.4. Autonomy

3.4.5. Job Intensity

3.4.6. Social Inclusion

3.4.7. Sub-Factors

3.4.8. Growth

3.4.9. Health Risks

3.4.10. Health Problems or Subjective Health Assessments (SHA)

3.5. Covariates

3.6. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Regression Analysis of Sickness Absence Using Tweedy GLM

4.3. Indirect Effect of Subjective Well-Being on Sick Days: Results of Regression and SEM Analyses

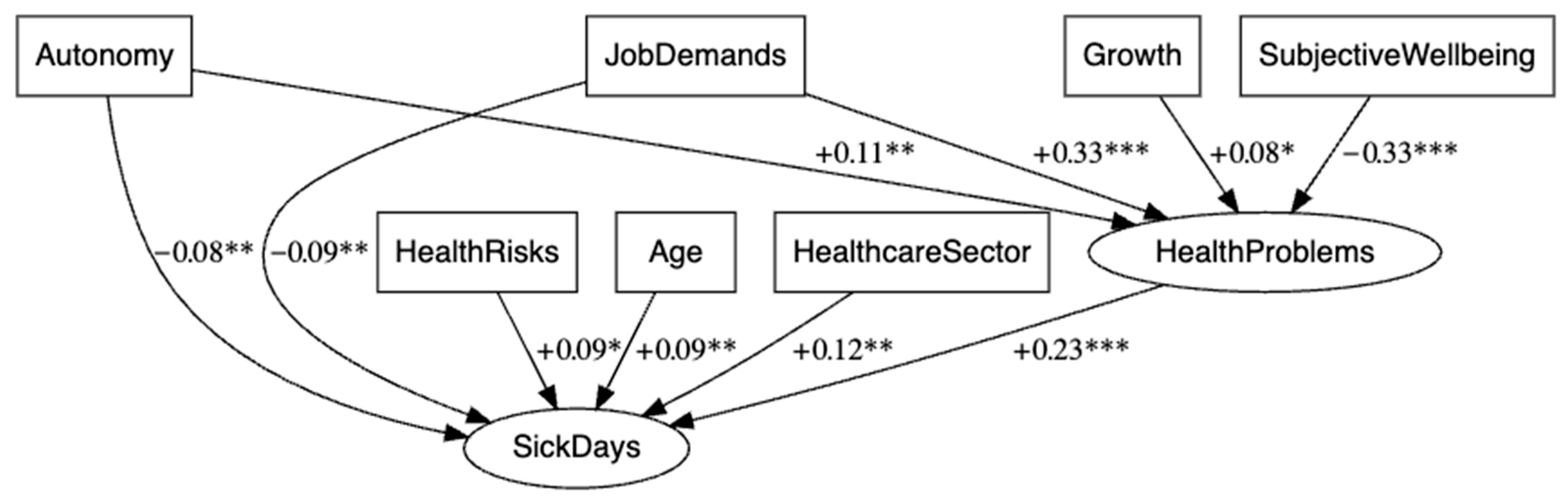

- Model 1: SEM without control variables

- Model 2: SEM with control variables

4.4. Results of Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Self-Rated Health Problems as the Strongest Predictor

5.2. Physical Risks in the Work Environment and Increase in Sick Days

5.3. Autonomy at Work as a Protective Factor

5.4. Sectoral Differences: More Sick Leave Days Among Healthcare Workers

5.5. Gender Differences in Sickness Absence

5.6. Length of Service and Sick Leave

5.7. Time Spent Commuting to Work as an Additional Risk Factor

5.8. Subjective Well-Being as an Indirect Factor

6. Limitations

7. Future Research

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aagestad, C., Johannessen, H. A., Tynes, T., Gravseth, H. M., & Sterud, T. (2014). Work-related psychosocial risk factors for long-term sick leave: A prospective study of the general working population in Norway. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(8), 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aakvik, A., Holmås, T. H., & Islam, M. K. (2010). Does variation in general practitioner (GP) practice matter for the length of sick leave? A multilevel analysis based on Norwegian GP-patient data. Social Science & Medicine, 70(10), 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, S., Mohos, A., Kalabay, L., & Torzsa, P. (2018). Potential correlates of burnout among general practitioners and residents in Hungary: The significant role of gender, age, dependant care and experience. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonso, J. H., Tynes, T., Thyssen, J. P., Holm, J.-Ø., & Johannessen, H. A. (2016). Self-reported occupational skin exposure and risk of physician-certified long-term sick leave: A prospective study of the general working population of Norway. Acta Dermato-Venereologica, 96(3), 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L. L., Fallentin, N., Thorsen, S. V., & Holtermann, A. (2016). Physical workload and risk of long-term sickness absence in the general working population and among blue-collar workers: Prospective cohort study with register follow-up. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 73(4), 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antai, D., Oke, A., Braithwaite, P., & Anthony, D. (2015). A ‘balanced’life: Work-life balance and sickness absence in four Nordic countries. The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 6(4), 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antczak, E., & Miszczyńska, K. M. (2021). Causes of sickness absenteeism in Europe—Analysis from an intercountry and gender perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antczak, E., & Miszczyńska, K. M. (2023). Measuring and assessing sick absence from work: A European cross-sectional study. Comparative Economic Research. Central and Eastern Europe, 26(4), 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, G., Marklund, S., Leineweber, C., & Helgesson, M. (2021). The changing nature of work-Job strain, job support and sickness absence among care workers and in other occupations in Sweden 1991–2013. SSM Population Health, 15, 100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, V., Leineweber, C., Toivanen, S., & Nyberg, A. (2018). Can a poor psychosocial work environment and insufficient organizational resources explain the higher risk of ill-health and sickness absence in human service occupations? Evidence from a Swedish national cohort. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 47(3), 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, L. H., Cifuentes, M., Rodríguez, A. C., Rey-Becerra, E., Johnson, P. W., Marin, L. S., Piedrahita, H., & Dennerlein, J. T. (2019). Whole-body vibration and back pain-related work absence among heavy equipment vehicle mining operators. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 76(8), 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekker, M. H., Rutte, C. G., & Van Rijswijk, K. (2009). Sickness absence: A gender-focused review. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 14(4), 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, S. (2020). Sick leave absence and the relationship between intra-generational social mobility and mortality: Health selection in Sweden. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S. R., & Cheek, J. M. (1986). The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. Journal of Personality, 54(1), 106–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, C. (2003). Beyond somatisation: A review of the understanding and treatment of medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS). The British Journal of General Practice, 53(488), 231. [Google Scholar]

- Catalina-Romero, C., Sainz, J., Pastrana-Jiménez, J., García-Diéguez, N., Irízar-Muñoz, I., Aleixandre-Chiva, J., Gonzalez-Quintela, A., & Calvo-Bonacho, E. (2015). The impact of poor psychosocial work environment on non-work-related sickness absence. Social Science & Medicine, 138, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, K., Chng, S., Clark, B., Davis, A., De Vos, J., Ettema, D., Handy, S., Martin, A., & Reardon, L. (2020). Commuting and wellbeing: A critical overview of the literature with implications for policy and future research. Transport reviews, 40(1), 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimed-Ochir, O., Nagata, T., Nagata, M., Kajiki, S., Mori, K., & Fujino, Y. (2019). Potential work time lost due to sickness absence and presence among Japanese workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(8), 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T., Christensen, K. B., Lund, T., & Kristiansen, J. (2009). Self-reported noise exposure as a risk factor for long-term sickness absence. Noise and Health, 11(43), 93–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Colin-Chevalier, R., Pereira, B., Dewavrin, S., Cornet, T., Baker, J. S., & Dutheil, F. (2025). Psychosocial well-being index and sick leave in the workplace: A structural equation modeling of Wittyfit data. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1385708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D. R. (2018). Analysis of binary data. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davey, M. M., Cummings, G., Newburn-Cook, C. V., & Lo, E. A. (2009). Predictors of nurse absenteeism in hospitals: A systematic review. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(3), 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, J.-E., Diener, E., Tay, L., & Xuereb, C. (2013). The objective benefits of subjective well-being. In J. Helliwell, R. Layard, & J. Sachs (Eds.), World Happiness Report 2013. UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2306651 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- d’Errico, A., & Costa, G. (2012). Socio-demographic and work-related risk factors for medium-and long-term sickness absence among Italian workers. The European Journal of Public Health, 22(5), 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S. (2003). Implications of population ageing for the labour market. Labour Market Trends, 111(2), 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Duchaine, C. S., Aubé, K., Gilbert-Ouimet, M., Vézina, M., Ndjaboué, R., Massamba, V., Talbot, D., Lavigne-Robichaud, M., Trudel, X., & Pena-Gralle, A.-P. B. (2020). Psychosocial stressors at work and the risk of sickness absence due to a diagnosed mental disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(8), 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchemin, T., & Hocine, M. N. (2020). Modeling sickness absence data: A scoping review. PLoS ONE, 15(9), e0238981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L. N., West, C. P., Sinsky, C. A., Goeders, L. E., Satele, D. V., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2017). Medical licensure questions and physician reluctance to seek care for mental health conditions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 92(10), 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. (2017). Sixth european working conditions survey—Overview report (2017 update). Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/all/sixth-european-working-conditions-survey-overview-report (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Eurofound. (2018). European quality of life survey 2016: Living conditions and quality of life. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/all/european-quality-life-survey-2016 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Eurofound. (2023). Living and working in Europe 2023. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/all/living-and-working-europe-2023 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Eurostat. (2020a). Self-reported work-related health problems and risk factors—Key statistics. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Self-reported_work-related_health_problems_and_risk_factors_-_key_statistics (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Eurostat. (2020b). Sickness/healthcare benefits up in 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20211123-1?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Fagerlund, P., Shiri, R., Walker-Bone, B., & Rahkonen, O. (2024). Long-term sickness absence trajectories and associated occupational and lifestyle-related factors: A longitudinal study among young and early midlife Finnish employees with pain. BMJ Open, 14(12), e085011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Framke, E., Sørensen, J. K., Alexanderson, K., Farrants, K., Kivimäki, M., Nyberg, S. T., Pedersen, J., Madsen, I. E., & Rugulies, R. (2021). Emotional demands at work and risk of long-term sickness absence in 1· 5 million employees in Denmark: A prospective cohort study on effect modifiers. The Lancet Public Health, 6(10), e752–e759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Framke, E., Sørensen, J. K., Nordentoft, M., Johnsen, N. F., Garde, A. H., Pedersen, J., Madsen, I. E., & Rugulies, R. (2019). Perceived and content-related emotional demands at work and risk of long-term sickness absence in the Danish workforce: A cohort study of 26 410 Danish employees. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 76(12), 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerich, J. (2019). Sickness presenteeism as coping behaviour under conditions of high job control. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(2), 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., & Velilla, J. (2022). Commuting time and sickness absence of US workers. Empirica, 49(3), 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønstad, A., Kjekshus, L. E., Tjerbo, T., & Bernstrøm, V. H. (2019). Organizational change and the risk of sickness absence: A longitudinal multilevel analysis of organizational unit-level change in hospitals. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halonen, J. I., Lallukka, T., Kujanpää, T., Lahti, J., Kanerva, N., Pietiläinen, O., Rahkonen, O., Lahelma, E., & Mänty, M. (2021). The contribution of physical working conditions to sickness absence of varying length among employees with and without common mental disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 49(2), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L. L. M., Madsen, I. E., Rugulies, R., Peristera, P., Westerlund, H., & Descatha, A. (2017). Temporal relationships between job strain and low-back pain. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 43(5), 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, E., Mattisson, K., Björk, J., Östergren, P.-O., & Jakobsson, K. (2011). Relationship between commuting and health outcomes in a cross-sectional population survey in southern Sweden. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. M., & Dunn, P. K. (2011). Two Tweedie distributions that are near-optimal for modelling monthly rainfall in Australia. International Journal of Climatology, 31(9), 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M., Harvey, S. B., Øverland, S., Mykletun, A., & Hotopf, M. (2011). Mental health problems and sickness absence. Occupational Medicine, 61(4), 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R. A., Heron, J., Sterne, J. A., & Tilling, K. (2019). Accounting for missing data in statistical analyses: Multiple imputation is not always the answer. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(4), 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilmarinen, J., & Ilmarinen, V. (2015). Work ability and aging. In Facing the challenges of a multi-age workforce (pp. 134–156). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, H. A., Gravseth, H. M., & Sterud, T. (2015). Psychosocial factors at work and occupational injuries: A prospective study of the general working population in Norway. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 58(5), 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R. A., Jr. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisakye, A. N., Tweheyo, R., Ssengooba, F., Pariyo, G. W., Rutebemberwa, E., & Kiwanuka, S. N. (2016). Regulatory mechanisms for absenteeism in the health sector: A systematic review of strategies and their implementation. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 8, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, P., De Meester, M., & Braeckman, L. (2008). Differences between younger and older workers in the need for recovery after work. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 81(3), 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Braley, C. (1997). C-Tests in the context of reduced redundancy testing: An appraisal. Language Testing, 14(1), 47–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. (2013). Handbook of psychological testing. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, H., & Glied, S. A. (2021). Associations between a New York City paid sick leave mandate and health care utilization among Medicaid beneficiaries in New York City and New York State. JAMA Health Forum, 2(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuoppala, J., Lamminpää, A., & Husman, P. (2008). Work health promotion, job well-being, and sickness absences—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 50(11), 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, C. F. (2017). Tweedie distributions for fitting semicontinuous health care utilization cost data. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17(1), 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Künn-Nelen, A. (2016). Does commuting affect health? Health Economics, 25(8), 984–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laaksonen, M., Mastekaasa, A., Martikainen, P., Rahkonen, O., Piha, K., & Lahelma, E. (2010). Gender differences in sickness absence-the contribution of occupation and workplace. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 36(5), 394–403. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2007). Emerging positive organizational behavior. Journal of Management, 33(3), 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, J. N., Barton Cunningham, J., & Caverley, N. (2008). Factors in absenteeism and presenteeism: Life events and health events. Management Research News, 31(8), 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, C. A., Caputi, P., & Lee, J. K. (2016). Distinct longitudinal patterns of absenteeism and their antecedents in full-time Australian employees. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastekaasa, A. (2014). The gender gap in sickness absence: Long-term trends in eight European countries. European Journal of Public Health, 24, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastekaasa, A., & Olsen, M. (1998). Gender, absenteeism, and job characteristics: A fixed effects approach. Work and Occupations, 25(2), 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerl, H., Stolz Waxenegger, A., Rásky, E., & Freidl, W. (2016). The role of personal and job resources in the relationship between psychosocial job demands, mental strain, and health problems. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mänty, M., Kouvonen, A., Nordquist, H., Harkko, J., Pietiläinen, O., Halonen, J., Rahkonen, O., & Lallukka, T. (2022). Physical working conditions and subsequent sickness absence: A record linkage follow-up study among 19–39-year-old municipal employees. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95(2), 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlig, K., von Below, A., Holmgren, K., Björkelund, C., Lissner, L., Skoglund, I., Hakeberg, M., & Hange, D. (2024). Exploring the impact of mental and work-related stress on sick leave among middle-aged women: Observations from the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 42(4), 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mess, F., Blaschke, S., Gebhard, D., & Friedrich, J. (2024). Precision prevention in occupational health: A conceptual analysis and development of a unified understanding and an integrative framework. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1444521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Latvia. (2024). Statistical data on sick leave. Available online: https://www.vm.gov.lv/lv/statistikas-dati-par-darbnespejas-lapam (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Miraglia, M., & Johns, G. (2016). Going to work ill: A meta-analysis of the correlates of presenteeism and a dual-path model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(3), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modini, M., Joyce, S., Mykletun, A., Christensen, H., Bryant, R. A., Mitchell, P. B., & Harvey, S. B. (2016). The mental health benefits of employment: Results of a systematic meta-review. Australasian Psychiatry, 24(4), 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, E., Cerela-Boltunova, O., Blumberga, S., Mihailova, S., & Griskevica, I. (2023). The Burnout and Professional Deformation of Latvian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic at the Traumatology and Orthopaedics Hospital. Social Sciences, 12(3), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, E., Griskevica, I., Rajevska, O., Ivanovs, A., Mihailova, S., & Skruzkalne, I. (2024). Factors affecting healthcare workers burnout and their conceptual models: Scoping review. BMC Psychology, 12, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I., Bertrais, S., & Witt, K. (2021). Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: A meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 47(7), 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. B., Indregard, A.-M. R., & Øverland, S. (2016). Workplace bullying and sickness absence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the research literature. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 42(5), 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, A., Peristera, P., Toivanen, S., & Johansson, G. (2022). Does exposure to high job demands, low decision authority, or workplace violence mediate the association between employment in the health and social care industry and register-based sickness absence? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2013a). OECD guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-guidelines-on-measuring-subjective-well-being_9789264191655-en.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- OECD. (2013b). OECD skills outlook 2013: First results from the survey of adult skills. OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-skills-outlook-2013_9789264204256-en.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- OECD. (2017a). OECD employment outlook 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-employment-outlook-2017_empl_outlook-2017-en.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- OECD. (2017b). OECD guidelines on measuring trust. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-guidelines-on-measuring-trust_9789264278219-en.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- OECD. (2019). OECD employment outlook 2019: The future of work. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-employment-outlook-2019_9ee00155-en.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Ogbonnaya, C. (2019). Exploring possible trade-offs between organisational performance and employee well-being: The role of teamwork practices. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(3), 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A., Braithwaite, P., & Antai, D. (2016). Sickness absence and precarious employment: A comparative cross-national study of Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Norway. The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 7(3), 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelen, C., van Rhenen, W., Schaufeli, W., van der Klink, J., Magerøy, N., Moen, B., Bjorvatn, B., & Pallesen, S. (2014). Mental and physical health-related functioning mediates between psychological job demands and sickness absence among nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(8), 1780–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelen, C. A., Koopmans, P. C., de Graaf, J. H., van Zandbergen, J. W., & Groothoff, J. W. (2007). Job demands, health perception and sickness absence. Occupational Medicine, 57(7), 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelen, C. A., Koopmans, P. C., & Groothoff, J. W. (2010). Subjective health complaints in relation to sickness absence. Work, 37(1), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugulies, R., Aust, B., & Pejtersen, J. H. (2010). Do psychosocial work environment factors measured with scales from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire predict register-based sickness absence of 3 weeks or more in Denmark? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(Suppl. 3), 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saastamoinen, P., Laaksonen, M., Lahelma, E., Lallukka, T., Pietiläinen, O., & Rahkonen, O. (2014). Changes in working conditions and subsequent sickness absence. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 40, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sakr, C. J., Fakih, L. M., Musharrafieh, U. M., Khairallah, G. M., Makki, M. H., Doudakian, R. M., Tamim, H., Redlich, C. A., Slade, M. D., & Rahme, D. V. (2025). Absenteeism Among Healthcare Workers: Job Grade and Other Factors That Matter in Sickness Absence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(1), 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: A transdisciplinary approach (pp. 43–68). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, A. D. (2024). Social aspects of work impacting after-work recovery and wellbeing. Available online: https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4-ubp/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/66841/file/schulz_diss.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Junior, J. S., & Fischer, F. M. (2015). Sickness absence due to mental disorders and psychosocial stressors at work. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 18, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J. K., Pedersen, J., Burr, H., Holm, A., Lallukka, T., Lund, T., Melchior, M., Rod, N. H., Rugulies, R., Sivertsen, B., Stansfeld, S., Christensen, K. B., & Madsen, I. E. H. (2023). Psychosocial working conditions and sickness absence among younger employees in Denmark: A register-based cohort study using job exposure matrices. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 49(4), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Social Insurance Agency. (2024, June 25). Procedure for issuing and canceling certificates of incapacity for work, cabinet of ministers regulations No. 409, Riga, (minutes No. 26, § 43). Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/353064-darbnespejas-lapu-izsniegsanas-un-anulesanas-kartiba (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet, 385(9968), 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterud, T. (2014). Work-related mechanical risk factors for long-term sick leave: A prospective study of the general working population in Norway. The European Journal of Public Health, 24(1), 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoetzer, U., Ahlberg, G., Johansson, G., Bergman, P., Hallsten, L., Forsell, Y., & Lundberg, I. (2009). Problematic interpersonal relationships at work and depression: A Swedish prospective cohort study. Journal of Occupational Health, 51(2), 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumanen, H., Pietiläinen, O., Lahti, J., Lahelma, E., & Rahkonen, O. (2015). Interrelationships between education, occupational class and income as determinants of sickness absence among young employees in 2002–2007 and 2008–2013. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S., Chen, J., Johannesson, M., Kind, P., & Burström, K. (2016). Subjective well-being and its association with subjective health status, age, sex, region, and socio-economic characteristics in a Chinese population study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 833–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timp, S., van Foreest, N., & Roelen, C. (2024). Gender differences in long term sickness absence. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trybou, J., Germonpre, S., Janssens, H., Casini, A., Braeckman, L., Bacquer, D. D., & Clays, E. (2014). Job-related stress and sickness absence among Belgian nurses: A prospective study. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 46(4), 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynes, T., Johannessen, H. A., & Sterud, T. (2013). Work-related psychosocial and organizational risk factors for headache: A 3-year follow-up study of the general working population in Norway. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55(12), 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Bureau of Labor Statistics USD of L. 7.8 million workers had an illness-related work absence in January 2022. The economics daily [Internet]. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2022/7-8-million-workers-had-an-illness-related-work-absence-in-january-2022.htm (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Usmani, R. S. A., Saeed, A., Abdullahi, A. M., Pillai, T. R., Jhanjhi, N. Z., & Hashem, I. A. T. (2020). Air pollution and its health impacts in Malaysia: A review. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 13(9), 1093–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veldhoven, M., Van den Broeck, A., Daniels, K., Bakker, A. B., Tavares, S. M., & Ogbonnaya, C. (2017). Why, when, and for whom are job resources beneficial? Applied Psychology, 66(2), 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerdesteijn, K. H., Schaafsma, F. G., van der Beek, A. J., Merkus, S. L., Maeland, S., Hoedeman, R., Lissenberg-Witte, B. I., Werner, E. L., & Anema, J. R. (2020). Sick leave assessments of workers with subjective health complaints: A cross-sectional study on differences among physicians working in occupational health care. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(7), 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2025). European health report 2024: Keeping health high on the agenda. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. (1998). Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the depcare project, report on a WHO meeting. WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors /Reference | Example of Items | Number of Items | Scale | Cronbach’s Alpha | Diff | DI | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective well-being (Eurofound, 2018) | WHO-5: How often do you feel that you are living a full life? (Eurofound) How often do you feel that your life is in balance (work and personal time)? | 7 | 0—Never 1—Rarely 2—Less than half the time 3—More than half the time 4—Most of the time 5—Always | 0.90 | 3.78–4.42 | 0.63–0.79 | 0.93 | 0.652 |

| Autonomy (Eurofound, 2017) | How often can you choose your own working methods or change them at your own discretion? | 2 | 1—Never 6—Always 7—I don’t want to answer | 0.8 | 3.64–4.00 | 0.66 | 0.697 | 0.697 |

| Job intensity (Eurofound, 2017) | How often do you have to work fast at high speed? | 3 | 1—Never 6—Always 7—I don’t want to answer | 0.74 | 3.03 | 0.46–0.63 | 0.78 | 0.536 |

| Social Inclusion (Eurofound, 2017; OECD, 2017b) | How often do you feel that you can influence decisions that are important for your work? | 6 | 1—Never 6—Always 7—I don’t want to answer | 0.83 | 3.23–4.85 | 0.52–0.66 | 0.86 | 0.494 |

| Growth (Eurofound, 2017) | Over the past year, I have received training that improves my future job prospects | 3 | 1—Yes 2—No | 0.78 | 4.09–4.55 | 0.50–0.68 | 0.90 | 0.755 |

| Health risks (Eurofound, 2017; OECD, 2017a) | How often are you exposed to noise at work? | 2 | 1—Never 6—Always 7—I don’t want to answer | 0.8 | 2.56–2.8 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.751 |

| Health problems (Eurofound, 2017) | Have you noticed any symptoms of mental ill health in yourself in the last 12 months? | 2 | 1—Yes 2—No 3—I don’t want to answer (coded as missing) | 0.78 | 0.691 | |||

| Sick days (data administered by organisations) | Please indicate the sick days of employee (code…) in 2023 (excluding postnatal leave) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Commuting time (Eurofound, 2017) | 1 (multiple choice) How much time do you spend commuting to and from work each day? | 1 | 1—Up to 30 min 5—More than 3 h | - | - | - | - | - |

| Descriptive Statistics Sick Leave Days 2023 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Company | N | Minimum | Max | Mean | Std. Deviation | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| All | 1631 | 0 | 196 | 11.75 | 21.81 | 3 | 3.57 | 17.23 |

| Public administration (1) | 281 | 0 | 180 | 9.57 | 19.36 | 0 | 4.12 | 25.59 |

| Healthcare Hospital (2) | 421 | 0 | 196 | 17.76 | 28.65 | 7 | 2.81 | 10.04 |

| Energy (3) | 488 | 0 | 140 | 9.31 | 16.50 | 0 | 3.51 | 18.40 |

| Pharma (4) | 441 | 0 | 151 | 10.12 | 19.81 | 3 | 3.81 | 18.14 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bootstrapping | Sensitivity test | ||||

| Variables | Est. coefficient, sig | Est. coefficient, sig | Est. coefficient, sig | Est. coefficient, sig | Est. coefficient, sig |

| Health risks | 0.1034 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.100 *** | 0.09 |

| Autonomy | 0.1925 | (−0.092) ** | (−0.09) *** | −0.181 | (−0.082) * |

| Health problems | 0.460 | 0.447 | 0.45 *** | 0.845 *** | 0.398 *** |

| Healthcare sector | 0.402 | 0.461 | 0.46 | 0.819 | 0.354 |

| Energy services | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.502 *** | n.s. |

| Manufacturing | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.064 *** | n.s. |

| Gender | (−0.367) ** | (−0.362) ** | (−0.36) ** | (−0.640) *** | (−0.236) * |

| Seniority in years | 0.010 | 0.010 | n.s. | 0.012 *** | 0.011 |

| commuting time_2 | 0.236 ** | n.s. | 0.352 *** | 0.247 * | |

| commuting time_3 | n.s. | 0.308 *** | n.s. | ||

| commuting time_4 | n.s. | (−0.146) *** | n.s. | ||

| commuting time_5 | n.s. | 1.024 ** | n.s. | ||

| Pseudo R2 (Mc Fadden’s) | 0.1992 | 0.1925 | 0.198 | ||

| AIC | 7568.43 | 7652.428 | 7169.4 | ||

| Path | Standardised Effect (Model 1) | Standardised Effect (Model 2) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Subjective well-being → Health problems | –0.271 *** | –0.329 *** | Higher well-being negatively associated with health problems; effect strengthens slightly after adding controls. |

| F3 Growth → Health problems | 0.079 ** | 0.081 * | Small positive association between growth opportunities and perceived health problems remains. |

| F4 Job Demands → Health problems | 0.261 *** | 0.329 *** | Job demands strongly associated with perceived health problems; effect slightly larger with controls. |

| F6 Autonomy → Health problems | 0.088 *** | 0.107 ** | Autonomy shows a weak positive relation with health problems in both models. |

| Health problems → Sick days | 0.146 *** | 0.232 *** | Health problems have a strong positive associations with sick-leave days; effect size increases with controls. |

| F5 Health risks → Sick days | – | 0.088 * | Work-environment risks significantly associated with predicted sick days (only significant when controls are added). |

| F6 Autonomy → Sick days | – | –0.079 ** | Greater autonomy has negative relationships with sick-leave days (protective effect emerging after controls). |

| F4 Job Demands → Sick days | – | –0.091 ** | Job demands show a small negative direct path after controls (possible suppression). |

| Age → Sick days | – | 0.091 ** | Older employees report more sick days. |

| Type company 2 → Sick days | – | 0.118 ** | Employees in the Health care sector have higher sickness absence. |

| R2 (Health problems) | 0.319 | 0.326 | Slight improvement after adding controls. |

| R2 (Sick days) | 0.075 | 0.081 | Slight improvement after adding controls. |

| Fit Index | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| CFI | 0.968 | Excellent fit (≥0.95) |

| TLI | 0.929 | Good fit (≥0.90) |

| RMSEA | 0.040 (CI: 0.019–0.064) | Excellent (below 0.05) |

| SRMR | 0.019 | Excellent (below 0.08) |

| AIC | 14,171.01 | Lowest score |

| Mediation Pathway | Indirect Effect (Model 1) | Std.all (Model 1) | Indirect Effect (Model 2) | Std.all (Model 2) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Subjective well-being → Health problems → Sick days | –1.01 | –0.040 *** | –0.093 | –0.077 *** | Higher well-being is indirectly associated with fewer sick days through lower levels of reported health problems. |

| F3 Growth → Health problems → Sick days | 0.124 | 0.012 ** | 0.010 | 0.019 * | Growth opportunities show a small positive indirect association with sick days via slightly higher levels of health problems |

| F4 Job Demands → Health problems → Sick days | 0.834 | 0.038 *** | 0.080 | 0.077 *** | Job demands show a strong and stable indirect association with sick days through higher levels of health problems. |

| F6 Autonomy → Health problems → Sick days | 0.231 | 0.013 ** | 0.021 | 0.025 ** | Autonomy shows a small positive indirect association with sick days via higher reported health problems. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Skrūzkalne, I.; Nagle, E.; Seņkāne, S.; Rajevska, O.; Nyberg, A.; Zamalijeva, O.; Ivanovs, A.; Reine, I. Psychosocial Work Factors, Well-Being, and Health Pathways to Sickness Absence: An Integrated GLM–SEM Approach. Adm. Sci. 2026, 16, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci16010007

Skrūzkalne I, Nagle E, Seņkāne S, Rajevska O, Nyberg A, Zamalijeva O, Ivanovs A, Reine I. Psychosocial Work Factors, Well-Being, and Health Pathways to Sickness Absence: An Integrated GLM–SEM Approach. Administrative Sciences. 2026; 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci16010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkrūzkalne, Iluta, Evija Nagle, Silva Seņkāne, Olga Rajevska, Anna Nyberg, Olga Zamalijeva, Andrejs Ivanovs, and Ieva Reine. 2026. "Psychosocial Work Factors, Well-Being, and Health Pathways to Sickness Absence: An Integrated GLM–SEM Approach" Administrative Sciences 16, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci16010007

APA StyleSkrūzkalne, I., Nagle, E., Seņkāne, S., Rajevska, O., Nyberg, A., Zamalijeva, O., Ivanovs, A., & Reine, I. (2026). Psychosocial Work Factors, Well-Being, and Health Pathways to Sickness Absence: An Integrated GLM–SEM Approach. Administrative Sciences, 16(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci16010007