Abstract

Literature on digital collaboration often focuses on individual aspects, but rarely combines them into a unified, practical and sustainability-friendly management tool. The paper fills this critical gap by presenting a comprehensive framework for enhancing digital collaboration, integrating AI, and aligning digital collaboration strategies with broader sustainability objectives. The framework includes four phases and 31 factors categorised into four dimensions. The framework is validated through a case study that combines qualitative (expert interviews) and quantitative (employee survey) approaches, as well as Mayring’s content analysis and the CARL analytical framework. The study reveals that fragmented tool use undermines collaboration maturity across all dimensions, while the integration of AI enhances collaboration outcomes and mitigates digital fatigue. A dual-core collaboration setup contributes to stronger strategic alignment, with the monitoring benefits framework facilitating sustainable improvement tracking. This way, the framework addresses digital fragmentation, tool redundancy, and deficient digital cooperation, leading to increased digital collaboration maturity and alignment with sustainability objectives. The proposed framework offers theoretical, managerial, and societal value by bridging the gap between digital transformation theory and sustainable organisational practice.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid advancement of digital transformation has changed how organisations collaborate, bringing both opportunities and challenges. Digital transformation is generally understood as the integration of digital technologies into business processes to enhance performance and business operations (Schallmo & Williams, 2018; Ivančić et al., 2019). This transformation alters how collaboration is conducted, particularly in light of new tools and technologies (Warner & Wäger, 2019; Aldoseri et al., 2024) and takes into account that digital transformation depends on organisational readiness, leadership competence, and technology alignment (Min & Kim, 2024).

Scholars largely recognise the pivotal role of digital transformation in collaboration. Historically, collaboration was characterised by teamwork within small, interdependent groups working together towards a shared goal (Sewell, 2001). However, in modern organisations, digital transformation necessitates a re-evaluation of collaboration practices because traditional methods often fail to adapt to the new, technology-driven landscape (Aldoseri et al., 2024). The rapid adoption of digital tools in the workplace has led to a fragmented ecosystem, where different teams often use a variety of tools that may not integrate well (Brioschi et al., 2021). This results in inefficiencies and communication gaps (Siemon et al., 2020), more distant connections, a lack of trust, and decreased interactions (Bankins et al., 2024). Comparable challenges have been identified in the public sector, where AI-driven digitalisation demands governance adaptation and human-capital renewal (Vatamanu & Tofan, 2025).

Despite the growing body of research on digital transformation and collaboration, existing studies often address these topics separately or focus on isolated maturity models (Boughzala & de Vreede, 2015; Reeb, 2023). Prior work has examined digital transformation processes (Ivančić et al., 2019), highlighted the contribution of AI to sustainability (Khan et al., 2025; Schwaeke et al., 2025), proposed AI maturity models (Lichtenthaler, 2020; Sadiq et al., 2021), and recognised digital maturity as a fundamental capability for transformation (Warner & Wäger, 2019). However, even the broad systematic review of 840 studies by Khan et al. (2025) indicates that AI-SDG research remains heterogeneous, fragmented, and insufficiently connected to intra-organisational collaboration practices. While AI-sustainability research notes collaboration in business-customer (Petrescu et al., 2024), business-stakeholder (Waschull & Emmanouilidis, 2022), intersectoral (Rusilowati et al., 2024), and interdisciplinary contexts (Petrescu et al., 2024), the intra-organisational digital collaboration maturity perspective is missing (Khan et al., 2025).

Therefore, this article develops a holistic framework for enhancing digital collaboration that integrates AI and sustainability. This study addresses a central research question: How can AI and sustainability be integrated into a comprehensive digital collaboration maturity framework that reflects the sociotechnical nature of modern organisations? To guide this investigation, three objectives were pursued: (1) to synthesise and extend existing collaboration maturity models, (2) to incorporate AI and sustainability into the structural, technological, behavioural and procedural dimensions of collaboration, and (3) to empirically assess the current (as-is) maturity state of the sample organisation while conceptualising a to-be maturity state enabled by AI-supported sustainable collaboration practices. The proposed framework harnesses digital transformation to address inefficiencies in collaborative work processes (Schubert & Williams, 2022; Olaniyi et al., 2024), going beyond digital maturity (Warner & Wäger, 2019) or AI maturity alone (Lichtenthaler, 2020; Sadiq et al., 2021) by integrating cross-cutting sustainability outcomes. AI plays a central role by enabling advanced communication, coordination, problem-solving, and process optimisation (Siemon et al., 2020; McComb et al., 2023), thus helping organisations manage the complexity of modern collaborative environments (Schubert & Williams, 2022).

The desired output of the framework’s application is an optimised digital collaboration environment that is efficient, effective, and well-integrated with organisational workflows and culture (Warner & Wäger, 2019). Considering the expanding evidence on AI contributions to SDGs (Khan et al., 2025; Schwaeke et al., 2025), the framework also aims to embed sustainability outcomes directly within collaboration improvement processes. This framework is intended to support organisational leaders, IT managers, and collaboration strategists seeking to enhance enterprise collaboration (Olaniyi et al., 2024). To achieve this, organisations should analyse their collaboration landscape, develop coherent improvement plans, and reflect on the success of implemented initiatives to drive iterative improvement (Milstein & Chapel, 2023). Similarly to the adoption challenges described by Min and Kim (2024), successful implementation of AI-based collaboration systems requires clear strategic objectives, resource commitment, management competency, and alignment with both performance and sustainability objectives.

2. Theoretical Framework

Digital collaboration tools have been defined as technologies that support collaborative work by improving workflow processes (Schallmo & Williams, 2018). These tools play a vital role in remote collaboration, offering flexibility and enabling teams to work together in virtual environments (Aldoseri et al., 2024).

A central premise of this study is that collaboration is foregrounded. At the same time, AI and sustainability are conceptualised as forces embedded within every collaborative dimension, rather than as external add-ons. This premise reflects the increasingly sociotechnical nature of digital collaboration, where technological features, organisational structures, collaborative behaviours, and AI-enabled processes co-evolve (Warner & Wäger, 2019; Bankins et al., 2024).

Hence, the conceptual structure of the framework, organised into strategy & structure, technology, culture & behaviour, and management & processes, is explicitly consistent with sociotechnical systems theory (STS) (Pasmore et al., 1982) and S-T model (Leavitt, 1965), which describe organisations as interdependent configurations of tasks, structures, technology, and people. The present study builds upon STS by extending it to contemporary collaboration ecosystems, where AI and digital sustainability reflect each of the classic sociotechnical elements.

As companies increasingly rely on digital tools for day-to-day collaboration, the importance of understanding different classifications and use cases of these tools becomes even more critical (Bankins et al., 2024). The first step in building a holistic digital collaboration framework is assessing the existing landscape of digital tools and workflows within an organisation (Ivančić et al., 2019). This involves categorising tools based on their functionality, usage patterns, and contribution to collaboration (Warner & Wäger, 2019). Employee initiatives for using certain tools should also be considered (Olaniyi et al., 2024).

2.1. Core Functionality and Workflow Approach

Following the core functionality and workflow approach, tools are categorised based on their most important characteristics and functionalities in relation to collaboration. Some tools are designed for synchronous collaboration, where all parties work simultaneously, e.g., videoconferencing, multiplayer virtual reality (VR)), while others facilitate asynchronous collaboration, allowing team members to contribute at their own pace (e.g., email, Google Docs.

AI is employed to streamline both types of collaboration by automating tasks, such as scheduling meetings or summarising asynchronous discussions, and hence reducing the cognitive load on team members (Bankins et al., 2024). Such AI features as meeting transcription and auto-scheduling eased the transition to digital collaboration. Another example is Gemini for Google Workspace, which helps to create structured documents with tables and images, or refine the content.

Table 1 summarises the categorisation of digital collaboration tools based on their core functionality and workflow. In addition, it illustrates how AI is typically integrated into various types of digital collaboration tools, improving the efficiency and effectiveness of both synchronous and asynchronous workflows (Schubert & Williams, 2022; Koesten et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Categorisation of digital collaboration tools and AI use cases: Core functionality approach.

Sustainability concerns also emerge at this level: collaboration patterns directly determine digital resource consumption, including cloud storage demand, data-processing intensity, and redundancy in shared content. AI has been shown to reduce digital waste and optimise resource usage, thereby contributing to sustainability targets such as lower energy consumption (Khan et al., 2025; Rusilowati et al., 2024).

2.2. Contribution Approach

The contribution approach categorises the tools based on their level of contribution to everyday work. This includes everything from basic information sharing to active content creation. Robra-Bissantz (2020) introduces a coordination dimension ranging from: zero and passive coordination, where mechanisms for coordination are available; to active coordination, where the tool autonomously manages coordination; and social coordination, where the tool incentivises social collaboration. At the intersection of two scales—content creation and coordination—six categories of collaboration tools emerged. Table 2 reflects how AI is integrated into these tools to enhance the contribution of team members.

Table 2.

Categorisation of digital collaboration tools and AI use cases: Contribution approach.

McComb et al. (2023) present a high-level approach to AI-human interaction. They categorise AI technologies based on whether they operate in a reactive or proactive mode, and whether they help to solve problems or improve current processes. In this way, a two-dimensional matrix is proposed, paving the way for AI to be social agents. Moreover, AI team members are perceived to have higher ability and integrity compared to human teammates (Dennis et al., 2023), thus contributing to greater resilience and sustainability. However, scholars also highlight the negative effects of employing AI for collaboration purposes (McComb et al., 2023; Dennis et al., 2023), suggesting the need for caution in adopting AI.

Sustainability considerations permeate contribution mechanisms as well. AI-supported workflows reduce redundant tasks, minimise communication loops, and lower the need for duplicative digital artefacts. All contribute to more sustainable digital work routines (Khan et al., 2025; Brioschi et al., 2021). Thus, productivity-enhancing and sustainability-enhancing functions coincide.

This framing aligns with STS by emphasising that humans and machines jointly shape collaborative behaviours and group dynamics. Rather than treating AI as external to collaboration, the model positions it as part of the sociotechnical ecosystem, which simultaneously affects task execution, coordination, interpersonal interaction, and sustainability.

2.3. Digital Collaboration Suites, Systems, Platforms

Unlike standalone collaboration tools, enterprise collaboration platforms (ECPs) take a broader, organisational-level approach to digital collaboration. Rather than being a single tool, an ECP is a portfolio of collaboration software that supports company-wide teamwork (Schubert & Williams, 2022; Brioschi et al., 2021). Since enterprise collaboration systems, which integrate collaboration features into daily workflows, are often used alongside independent digital tools, the combined ecosystem of these components forms an ECP. Sustainability considerations (e.g., tool consolidation, reduced data redundancy, eco-efficient digital systems) are increasingly embedded in the design of collaboration platforms (Khan et al., 2025; Schwaeke et al., 2025).

Schubert and Williams (2022) argue that ECPs are not one-size-fits-all solutions that cover every aspect of enterprise collaboration. Instead, building an effective ECP requires selecting and integrating different types of collaboration software to create a tailored digital environment. In this way, an organisation is attributed to a certain digital collaboration configuration, e.g.,:

- concentration, where a core collaboration system or suite is used alongside a limited number of additional tools;

- diversity, which involves a core system or suite supplemented by a broad range of extra tools;

- and dual core, where two central systems or suites operate in parallel, each with a few supplementary tools (Schubert & Williams, 2022).

A significant challenge in implementing ECP is digital fragmentation, where disconnected tools create silos within organisations. AI helps overcome this by integrating tools and streamlining data flow across systems (Bankins et al., 2024). It provides insights into tool usage and thus helps organisations optimise their collaboration strategies (Aldoseri et al., 2024). For instance, for PwC, Google Workspace’s AI-powered digital tools suite enhanced global collaboration and reduced project delivery time by 15%. Similarly, IBM’s adoption of Slack, integrated with AI, streamlined communication and predicted bottlenecks, thus boosting productivity across its 350 k employees (Business Insider, 2020). Effective enterprise platforms, therefore, need integrated, AI-enhanced features to support smooth and productive collaboration.

From a sustainability perspective, collaboration architectures also shape the ecological footprint of digital work. Platform consolidation reduces unnecessary cloud storage, lowers energy demand through fewer duplicative systems, and enables energy-efficient API ecosystems (Brioschi et al., 2021). AI contributes to sustainability by identifying the most efficient collaboration configuration and detecting digital waste.

Here again, the platform perspective aligns with STS (Pasmore et al., 1982): platforms shape technological and structural layers simultaneously, influencing behavioural and managerial processes. AI-driven integration thus becomes a sociotechnical mechanism that reorganises organisational communication, task interdependence, resource flows, and outcomes in terms of SDGs.

2.4. Digital Collaboration Maturity

Collaboration maturity describes how teams progress from basic to advanced, efficient practices, enhancing overall performance (Boughzala & de Vreede, 2015). Collaboration maturity models assist in defining and prioritising improvement areas by looking at a snapshot of a company’s situation. To develop a digital collaboration maturity assessment for the digital collaboration improvement framework, we combined three maturity models and the fragmented collaboration evaluation criteria to offer a comprehensive maturity approach. From a broader digital-governance standpoint, Vatamanu and Tofan (2025) demonstrate that AI integration maturity depends on governance quality, digital readiness, and workforce adaptability: factors that similarly underlie intra-organisational collaboration maturity.

The Collaboration Maturity Model proposed by Boughzala and de Vreede (2015) is a framework designed to evaluate team collaboration quality within organisations. In the model, collaboration maturity is categorised into ad hoc, exploring, managing, and optimising, thus representing a progression from initial collaboration challenges to achieving optimal collaboration efficiency.

The Collaboration for Innovation Readiness Assessment Model, introduced by Gummer (2017), focuses on assessing social collaboration and innovation maturity within an organisation. This model evaluates seven key dimensions, including organisational culture, leadership, workspace design, supporting technologies, innovation capacity, knowledge management, and business process integration through collaboration tools.

The Intraorganizational Online Collaboration Maturity Model by Reeb (2023) is tailored toward enhancing organisations’ ability to collaborate effectively across teams and departments using online collaboration tools. The model is built around four dimensions: strategy and change, processes and structure, technology and infrastructure, and employees and culture.

In addition, various collaboration evaluation criteria are not included in the indicated models. Since maturity models can be customised to fit specific organisational needs, Table 3 provides an overview of additional collaboration assessment criteria.

Table 3.

Overview of fragmented collaboration maturity criteria.

2.5. Sustainability Aspects in Digital Collaboration

To systematise the role of sustainability within the collaboration maturity framework, Table 4 summarises how sustainability-related mechanisms identified in the literature map onto the four dimensions of digital collaboration maturity. These mechanisms align with AI-driven optimisation, digital resource efficiency, and sustainable organisational routines, all of which are consistently reported in contemporary research on sustainable digital transformation.

Table 4.

Sustainability-related mechanisms relevant to digital collaboration maturity.

Table 4 clarifies that sustainability is structurally embedded within each maturity dimension, directly supporting the logic of the holistic framework presented in the next section.

2.6. Digital Collaboration Improvement Framework

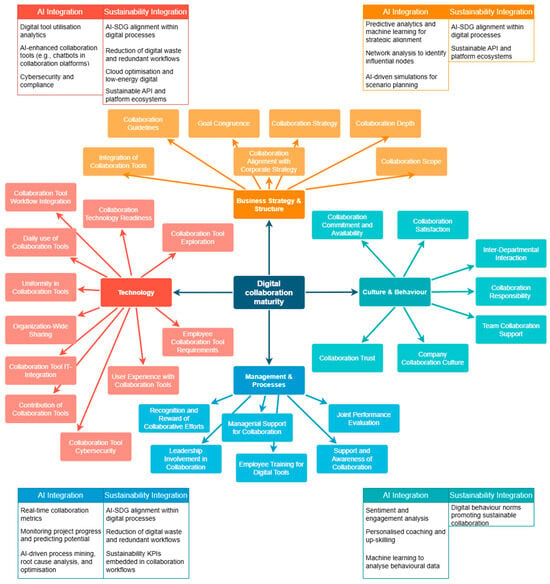

To develop a digital collaboration maturity assessment for the digital collaboration improvement framework, we combined the three identified maturity models (Boughzala & de Vreede, 2015; Gummer, 2017; Reeb, 2023) and the fragmented collaboration evaluation criteria (Table 3) to offer a comprehensive maturity approach. The framework employs four dimensions—strategy & structure, management & processes, technology, and culture & behaviour—which correspond to the main areas influencing collaborative work. These four dimensions align with the sociotechnical logic of Leavitt’s S-T model. Strategy & structure correspond to organisational structure; technology maps onto the technological subsystem; culture & behaviour correspond to the people/behavioural subsystem; and management & processes reflect task execution and workflow routines. By integrating AI and sustainability into all dimensions, the model updates STS for the contemporary digital workplace. The framework extends STS in two important ways. First, collaboration is foregrounded as the central organising principle around which all four dimensions interact, whereas STC treats task, structure, technology, and people symmetrically. And second, AI and sustainability mechanisms are embedded across all dimensions, reflecting contemporary organisational realities absent from the traditional S-T model (Leavitt, 1965). This integration positions the framework as an evolution of sociotechnical theory for AI-intensive, sustainability-oriented digital environments and demonstrates how modern collaboration combines human agency, digital tools, and AI-mediated processes in an interdependent manner. The framework is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Collaboration maturity dimensions with maturity factors.

Importantly, in this framework, each maturity dimension is influenced by embedded AI and sustainability mechanisms. For instance, strategy incorporates AI-enabled collaboration governance and sustainable digital policies, processes reflect algorithmic coordination and low-waste communication routines, technology encompasses AI-integrated workflows and eco-efficient tool use, and behaviour covers human-AI teaming, trust, and digital sustainability norms. By treating AI and sustainability as interwoven influences, the model avoids positioning them as peripheral indicators, thus responding to calls for a more integrated, contemporary understanding of collaboration maturity (Warner & Wäger, 2019; Schubert & Williams, 2022).

2.7. Theoretical Propositions

The reviewed literature highlights a set of consistent mechanisms through which collaboration structures, technologies, managerial processes, and behaviours influence the effectiveness of AI-enabled and sustainability-oriented collaboration practices. To make these mechanisms explicit and to clarify the theoretical contribution of the present framework, we derive four propositions from the reviewed literature.

First, research consistently shows that digital transformation succeeds only when collaboration is strategically embedded (Warner & Wäger, 2019; Schallmo & Williams, 2018). STS theory likewise emphasises the importance of structural and strategic alignment (Pasmore et al., 1982; Leavitt, 1965). Recent studies on AI-driven sustainability underline that governance maturity and strategic coherence are prerequisites for aligning AI with SDG-oriented practices (Schwaeke et al., 2025; Vatamanu & Tofan, 2025). Based on this, we propose:

P1. Higher maturity in the Strategy & Structure dimension enables stronger AI-supported strategic coordination and improves the alignment of collaboration practices with sustainability objectives.

Second, the literature on digital collaboration technologies highlights the centrality of integration. Fragmented tools reduce efficiency (Siemon et al., 2020; Schubert & Williams, 2022) and undermine AI-enabled optimisation, which depends on interoperable data flows (Aldoseri et al., 2024; Koesten et al., 2019). Sustainability studies similarly indicate that technological integration reduces digital waste and supports low-energy infrastructures (Khan et al., 2025; Rusilowati et al., 2024). Thus:

P2. Higher technological integration reduces digital fragmentation and digital waste by enabling AI orchestration, workflow optimisation, and interoperable data flows.

Third, empirical research shows that managerial processes—training, support structures, performance systems—shape the adoption of AI and sustainable digital practices (Hilger & Wahl, 2022; Min & Kim, 2024). Effective AI use requires stable process environments, structured data, and institutionalised routines (Dennis et al., 2023; McComb et al., 2023). Sustainability research likewise demonstrates that process discipline is essential for establishing sustainability KPIs and low-waste digital routines (Schwaeke et al., 2025; Ivančić et al., 2019). Therefore:

P3. Higher maturity in Management & Processes facilitates more effective AI-driven optimisation and supports the institutionalisation of sustainable collaboration behaviours.

Finally, the collaboration literature establishes that cultural factors—trust, psychological safety, shared norms—are critical enablers of cross-unit collaboration (De Clercq et al., 2011; Cross et al., 2019). STS views the behavioural subsystem as foundational for technology adoption. Recent research confirms that AI-supported collaboration is more effective when employees trust AI outputs and share norms of responsible digital behaviour (McComb et al., 2023) and that sustainable digital practices emerge through reinforcement of behavioural norms (Schwaeke et al., 2025). Accordingly:

P4. Higher maturity in Culture & Behaviour strengthens the adoption of AI-supported collaboration practices and reinforces sustainability-oriented digital norms.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach was structured in three phases: (1) expert interviews to validate the conceptual foundations and refine the operationalisation of collaboration maturity factors; (2) a large-scale employee survey to measure perceived collaboration maturity; and (3) analytical procedures integrating both qualitative and quantitative insights to inform the improvement plan. Across all phases, strict confidentiality safeguards were implemented to ensure the anonymity of participants and the protection of commercially sensitive organisational information.

3.1. Research Design

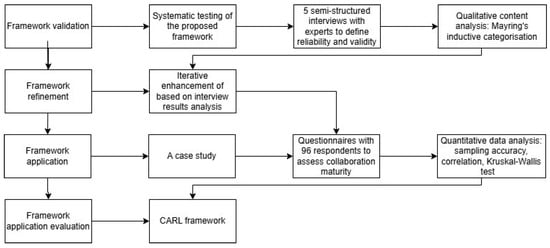

The research design followed a sequential exploratory logic, where qualitative insights informed the refinement of the maturity instrument, which was subsequently evaluated through the quantitative survey. Semi-structured expert interviews were first conducted to refine the conceptualisation of collaboration maturity and integrate AI- and sustainability-related elements within existing dimensions. This qualitative phase informed the development of the survey instrument, which was subsequently deployed organisation-wide. The survey results provided a quantitative maturity profile, enabling an assessment of the organisation’s strengths and weaknesses and supporting cross-regional, departmental and leadership-based comparisons. Figure 2 illustrates the four phases of the empirical research, each progressively building upon the previous step.

Figure 2.

Research design.

The maturity dimensions in this study are conceptualised as formative constructs, where each factor contributes a distinct aspect of the overall maturity profile, and the extension of the model with AI and sustainability follows the logic of formative augmentation. Formative constructs do not assume internal covariance among indicators (Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001; Jarvis et al., 2003), and the aim of this instrument is diagnostic. Accordingly, the present study does not attempt to establish a fully validated measurement scale (Lambert & Newman, 2023), particularly given confidentiality constraints and the inability to publish item-level data. Nevertheless, the study adheres to the core principles of rigorous construct operationalisation provided in Appendix A: exploratory qualitative work informed indicator definition, existing maturity models guided item formulation, and quantitative analysis supported empirical grounding.

3.2. Qualitative Phase: Expert Interviews

A qualitative interview approach was selected as the first step because it provides a reliable way to collect detailed and experience-based insights (Helfferich, 2019). Five semi-structured expert interviews were conducted with senior specialists occupying cross-organisational or strategic roles. Selection criteria: (1) direct involvement in digital collaboration governance, (2) platform consolidation, or (3) transformation initiatives, and at least five years of experience in the field. None of the interviewees were from the author’s department to ensure independence and avoid positional bias.

Five expert interviews were conducted with individuals occupying roles relevant to collaboration governance, digital tool management, and strategic transformation. To preserve anonymity, participants are described in aggregated categories: one senior IT architect responsible for collaboration platforms, one digital transformation manager, one process manager from professional services, one HR development specialist, and one regional operations leader. Across these roles, participants had between 7 and 18 years of professional experience (average ≈ 12 years) in digital transformation, process optimisation, or organisational collaboration, ensuring that technological, organisational, managerial, and cultural perspectives were adequately represented.

The interviews lasted between 45 and 90 min and were conducted online. The interview guide followed Helfferich’s (2019) four-step structure. A sample of five is consistent with expert-based instrument refinement in exploratory sequential designs, where conceptual saturation rather than representativeness is the criterion. All interviews were transcribed and analysed using Mayring’s qualitative content analysis (Mayring & Gläser-Zikuda, 2008). Initial inductive codes were developed and iteratively consolidated into higher-order categories corresponding to the maturity dimensions. Two coders reviewed the coding structure to ensure conceptual coherence; disagreements were resolved through discussion. Because of confidentiality constraints, no verbatim quotations are reported; instead, aggregated themes, corresponding to the four maturity dimensions and their underlying factors, are presented. Insights from this qualitative phase informed the refinement of the maturity dimensions and provided input for the survey instrument and the subsequent phase of the research.

3.3. Quantitative Phase: Employee Survey

To determine the minimum required number of survey respondents, a standard sample size estimation procedure for proportions was applied. Following common practice in organisational research, we assumed a 95% confidence level, 10% margin of error, and the most conservative estimate of population variability (p = 0.5), which maximises the required sample size (Cochran, 1977):

Thus, 96 responses would be required if the organisation had an infinitely large population. Because the actual population of the organisation consists of approximately N = 5500 employees (rounded for confidentiality), the finite population correction (FPC) was applied. After incorporating this correction, the minimum required sample size was 94 respondents. In practice, the survey achieved 96 valid responses, exceeding the corrected minimum threshold and therefore ensuring that the results are statistically adequate for exploratory analysis and descriptive maturity assessment.

The organisation employs roughly 5500 people, but the survey was distributed to these 1200 respondents across 12 departments involved in digital workflows. A total of 96 valid responses were received, yielding an 8% response rate. Importantly, this exceeds the minimum required sample size (n = 94) and is adequate for the study’s exploratory maturity assessment.

3.4. Survey Instrument

The survey was open online for three weeks from the end of March 2024. The survey measured 31 collaboration maturity factors derived from the qualitative phase. Respondents evaluated each factor on a 4-point scale (1 = low maturity, 4 = high maturity), consistent with established practice in maturity assessments. Descriptive anchors for each level were provided to support consistent interpretation, in line with best practices for maturity assessment instruments. The primary objective was to assess the core maturity dimensions—strategy and structure, technology, culture and behaviour, and management and processes. To ensure conceptual integrity, AI and sustainability were embedded within definitions of the relevant KPIs. The full instrument is provided in Appendix A.

Cronbach’s alpha values demonstrated acceptable internal consistency across the four collaboration maturity dimensions, confirming that the framework’s foundational structure is suitable for empirical use.

3.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0: descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and the Kruskal–Wallis test to identify regional differences in maturity perceptions. Non-parametric methods were selected due to the ordinal nature of the maturity scale and the non-normal distribution of responses. AI and sustainability indicators were treated as exploratory only and used to contextualise interpretations, consistent with the framework’s developmental stage.

The findings were structured using the CARL framework (Context, Actions, Results, Learnings) for comprehensive analysis and actionable insights (Robinson, 2022). Contrary to the AS-IS state, TO-BE state does not represent empirical findings, but rather the theoretically informed implications of the AS-IS diagnosis. Following design-science logic (Gregor & Hevner, 2013) and sociotechnical systems theory (Leavitt, 1965; Pasmore et al., 1982), the gaps identified in the AS-IS digital collaboration maturity assessment provide the basis for formulating AI- and sustainability-enhanced improvements. The TO-BE state therefore integrates (a) empirical weaknesses, (b) the maturity framework, and (c) established literature on AI-driven and sustainability-oriented collaboration practices. In this way, the TO-BE represents the theoretically grounded future state toward which the organisation aims to progress.

3.6. Case Application

Following Milstein and Chapel (2023), the framework was applied within one department to demonstrate its practical usability. This department was selected because it offered direct access for longitudinal monitoring and iterative refinement. While the case application occurred within a single unit, the underlying empirical data (interviews and survey responses) reflect cross-regional and cross-functional perspectives, ensuring that the framework is not limited to the context of the case example.

To monitor the implementation, we followed the monitoring benefits change framework (Nitschke & Williams, 2020). This framework enables the comparison of long-term projects by capturing, analysing, and visualising the evolution of outcomes and benefits over time. Its value lies in addressing the dynamic nature of collaboration tools and practices, which continuously evolve through usage and adaptation. By offering a structured approach to monitoring these changes, the framework helps organisations refine their collaboration strategies, allowing them to respond effectively to emerging challenges and opportunities.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and no sensitive personal data was collected. Interviewees received information about the study’s purpose and provided informed consent. In accordance with institutional guidelines, the study did not require formal ethical review because it examined organisational practices rather than personal attributes.

4. Results

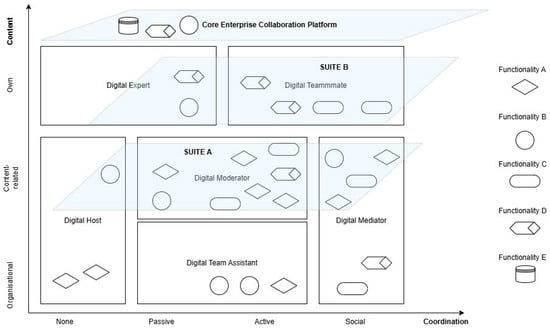

4.1. Digital Collaboration Landscape

The tools were categorised by their core functionalities, levels of contribution and coordination (Robra-Bissantz, 2020), and tools’ affiliations with digital collaboration suites, systems and platforms (Schubert & Williams, 2022) as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mapping the digital collaboration landscape.

4.2. Survey Sample, Representativeness and Reliability

Respondents were spread across Administration (10.4%), Professional Services (47.9%), Sales (31.3%), and Solution Sales (10.4%). In terms of leadership status, 17.7% of respondents held a leadership position and 82.3% did not. Sales is slightly overrepresented, and leadership roles are more represented in the sample (around 18%) than in the overall business unit (around 7%). This implies a dataset that amplifies leadership perspectives, which is beneficial in the context of collaboration improvement initiatives.

The results of the quantitative analysis indicate that the utilised scale is generally reliable and well-constructed, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Reliability analysis.

4.3. Group Differences

Across all organisational subgroups, the analysis indicates a largely homogeneous maturity profile. Kruskal–Wallis tests show no statistically significant regional differences for any of the four maturity dimensions (all p > 0.05), with only one isolated factor—collaboration trust—exhibiting a significant difference between regions (p < 0.05), although the corresponding effect size cannot be disclosed. Similarly, no significant differences emerged between leaders and non-leaders at the dimension level (all p > 0.05), although leaders consistently rated several management-related factors 5–15% lower than non-leaders, suggesting greater managerial awareness of structural and processual shortcomings. Departmental comparisons likewise revealed no dimension-level differences (p > 0.05), indicating that collaboration maturity challenges and strengths are broadly shared across functional units.

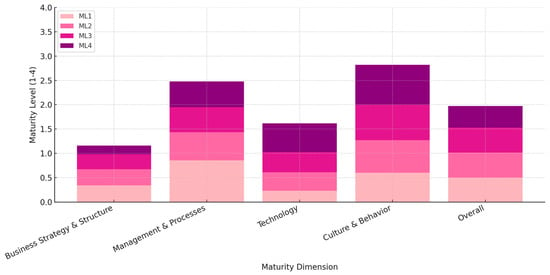

4.4. Collaboration Maturity and Dimension Profiles

When normalised to a 0–1 scale, the overall maturity level for the business unit lies between 0.63 and 0.67. In the original four-level maturity model, this corresponds to a position between Maturity Level (ML) 2 and ML 3, reflecting moderately developed collaboration practices that are present but not consistently embedded. The general results are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Overall digital collaboration maturity level results.

A closer examination of the four dimensions shows that Business Strategy & Structure and Management & Processes are rated in the lower part of maturity level 2. In contrast, Technology and Culture & Behaviour are rated in the higher part of maturity level 2, with Culture & Behaviour almost reaching maturity level 3.

In addition, the data were also analysed dimension-wise for collaboration maturity scoring, improvement plan implementation and tracking, and benchmarking purposes.

4.5. Dimension-Level Findings

4.5.1. Business Strategy & Structure

Business Strategy & Structure is the least mature dimension, positioned at the lower end of ML2. Two factors—Collaboration Scope and Collaboration Guidelines—fall clearly within the lower ML2 band (≈50–55%). Mid-ML2 patterns (≈55–60%) appear for Collaboration Strategy, Strategic Alignment, and Integration of Collaboration Tools. The strongest factors in this dimension are Collaboration Depth and Goal Congruence (upper ML2, ≈60–65%), yet even these remain below ML3.

4.5.2. Technology

Technology maturity is positioned within mid ML2. The weakest item—IT integration of collaboration tools (<50%)—is also the lowest single factor across all 31 items, highlighting fragmented system landscapes and insufficient interoperability. In the lower ML2 range (50–60%), employees report insufficient consideration of collaboration-tool requirements during tool adoption and adaptation. Most remaining factors—User Experience, Organisation-wide Sharing, Tool Uniformity, Daily Use, and Technology Readiness—fall in the upper ML2 band (≈65–75%), indicating good adoption and widespread everyday use.

4.5.3. Management & Processes

Management & Processes performs substantially better than Strategy & Structure and Technology, finding itself in the mid-to-upper ML2 range (~2.5 in the figure). Lower ML2 factors (50–55%) include Joint Performance Evaluation, Training for Digital Tools, Support & Awareness of Collaboration, and Recognition & Reward of Collaborative Efforts. Mid ML2 factors (55–60%) include Leadership Involvement and Managerial Support, suggesting moderately strong leadership engagement despite gaps in support structures. Leadership respondents consistently rate several items 5–15% lower than non-leaders, indicating that managers themselves see more process fragmentation than employees.

4.5.4. Culture & Behaviour

Culture & Behaviour is the strongest dimension, positioned between upper ML2 and ML3 (≈2.8). Lower ML2 results (55–65%) appear for Team Collaboration Support, Company Collaboration Culture, and Inter-departmental Interaction. Upper ML2/ML3 outcomes (70–80%) include Collaboration Responsibility, Collaboration Trust, Collaboration Satisfaction, and Commitment & Availability.

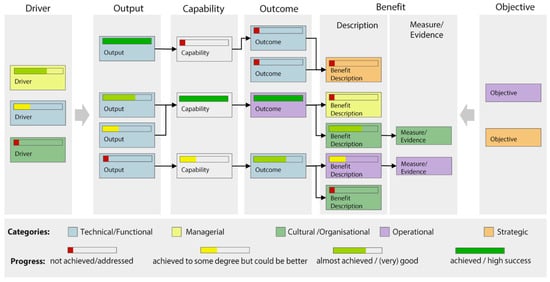

4.6. Digital Collaboration Benefits Framework

The obtained results were integrated into the monitoring benefits change framework as shown in Figure 5. This analytical framework serves as a tool for strategic planning and tracking the outcomes and benefits of collaboration systems (Nitschke & Williams, 2020).

Figure 5.

Monitoring benefits change framework (Nitschke & Williams, 2020).

The progress of each element’s implementation is assessed through subjective evaluations provided by the employees responsible for them. These evaluations are then visualised within the framework using a four-level progress bar. Except for capabilities, all elements are categorised into different organisational dimensions, each represented by a distinct colour. This classification provides a clear and structured way to track progress across various levels of the organisation while ensuring alignment with its broader goals. The project is still ongoing.

4.7. Managing Digital Collaboration Improvement Projects

Once the weaknesses in digital collaboration have been identified, a plan for improving digital collaboration was developed. This plan is tailored to the specific needs of the organisation and based on the insights gained from the previous steps. AI played a significant role in this process by providing predictive analytics that help forecast the potential impact of different improvement strategies (Koesten et al., 2019). In this way, the organisation could prioritise its improvement efforts by identifying the areas that would have the greatest impact on overall productivity and performance.

5. Discussion

5.1. AS-IS State of Digital Collaboration, AI, and Sustainability

5.1.1. Strategic Fragmentation and Limited AI-Sustainability Alignment

The Business Strategy & Structure dimension is the least mature, reflecting limited strategic coordination and a lack of formal governance for cross-unit collaboration. This low maturity level is consistent with earlier research showing that digital transformation often fails when collaboration is not strategically embedded (Warner & Wäger, 2019; Schallmo & Williams, 2018). The weak strategic alignment also explains why AI-enabled strategic capabilities, such as predictive analytics, network analysis for identifying influential nodes, and scenario modelling, remain underdeveloped. These gaps parallel external analyses that emphasise governance and readiness as prerequisites for AI-driven sustainability (Schwaeke et al., 2025; Vatamanu & Tofan, 2025).

Sustainability also remains weak at the strategic level. The absence of formal guidelines or a sustainability-oriented collaboration strategy indicates that AI–SDG alignment and resource-efficient collaboration structures are not yet part of strategic decision-making. This aligns with Khan et al. (2025), who report that organisations struggle to embed sustainability within digital processes due to fragmented governance.

These results indicate that insufficient structural maturity limits AI-supported strategic coordination and sustainability alignment, thus supporting P1.

5.1.2. Technology Strengths Hindered by Integration Gaps

The Technology dimension displays widespread adoption and daily use of tools, consistent with the organisation’s profile as a digital solutions provider. Strong results for user experience, tool uniformity, organisation-wide sharing, and technology readiness indicate that employees are willing and able to use the tools available to them (Lopes et al., 2015; Olaniyi et al., 2024).

However, the single lowest factor across the entire framework—IT integration of collaboration tools—reveals a significant structural weakness. Fragmented technology landscapes undermine collaboration, increase cognitive load, and reduce efficiency (Siemon et al., 2020; Schubert & Williams, 2022). This weakness directly affects the organisation’s capacity to adopt AI coherently. Without system integration, AI cannot perform core functions such as usage analytics, workflow optimisation, or automated data exchange between tools (Aldoseri et al., 2024; Koesten et al., 2019).

Sustainability issues are similarly affected. Redundant workflows, digital waste, and inefficient data storage persist when systems are not integrated, preventing the implementation of greener alternatives such as low-energy cloud architectures (Brioschi et al., 2021) or AI-driven reduction in unnecessary communication load (Khan et al., 2025). Thus, the results highlight a paradox: technological maturity is high in adoption but low in integration, limiting AI-enabled efficiency gains and sustainability benefits.

In general, the strong use but weak integration of tools demonstrates how fragmentation constrains AI optimisation and sustainability outcomes, supporting P2.

5.1.3. Managerial Processes: Strong Involvement, Weak Structural Support

The coexistence of strong leadership commitment and weak structural routines indicates only partial readiness for AI-driven optimisation and sustainable workflows, partially supporting P3. The Management & Processes dimension ranks second-highest, reflecting satisfactory leadership involvement and managerial support. These are positive indicators, given the importance of competency and commitment for AI-enabled transformation (Min & Kim, 2024). However, the lower-scoring factors, i.e., joint performance evaluation, recognition of collaborative efforts, training for digital tools, and collaboration support structures, indicate that many processes lack formal institutionalisation. These gaps hinder the implementation of AI-driven process mining, behavioural analytics, and personalised learning pathways, which require structured data and stable workflows (Hilger & Wahl, 2022; Dennis et al., 2023). The mixed maturity profile is consistent with the expectations of P3.

Sustainability also suffers from these weaknesses: sustainable collaboration practices (e.g., reduced digital waste, sustainable behavioural norms, systematic tracking of sustainability KPIs) require standardised processes and organisation-wide monitoring mechanisms (Schwaeke et al., 2025). The finding that leaders consistently rate managerial maturity lower than non-leaders suggests that leadership is aware of the systemic gaps that inhibit high-performance collaboration, including AI-supported and sustainability-oriented improvements.

5.1.4. Cultural Strengths as a Compensatory Mechanism

The strongest dimension—Culture & Behaviour—shows that employees collaborate well interpersonally, trust colleagues, feel responsible for collaboration tasks, and are generally satisfied with collaboration experiences. These results reflect what the literature identifies as the core enabler of intra-organisational collaboration: psychological safety, relational trust, and shared norms (De Clercq et al., 2011; Bernstein et al., 2022; Cross et al., 2019). This cultural strength also explains why collaboration remains functional despite weaknesses in strategy, processes, and technology. Culture effectively acts as a compensatory mechanism, enabling teams to overcome structural fragmentation. The high maturity of trust, responsibility, and shared norms provides the cultural basis predicted to enable AI-supported and sustainable collaboration practices, supporting P4.

Nevertheless, AI integration remains limited in this dimension. Although AI-based sentiment analysis, behavioural insights, and personalised coaching are theoretically possible (McComb et al., 2023), their adoption is constrained by the lack of formal processes and strategic coherence.

Sustainability behaviours, such as minimising unnecessary digital work, reducing redundant communication, and building sustainable behavioural norms, are also not yet systematically cultivated, although the cultural foundation would support such normative change (Schwaeke et al., 2025).

Thus, while the cultural environment is favourable, it is underutilised as a platform for systematic AI-augmented and sustainability-oriented collaboration improvement.

5.1.5. Overall Interpretation: Collaboration as the Integrating Mechanism

Overall, the evidence provides full support for P1, P2, and P4, and partial support for P3. The results support the study’s underlying assumption: collaboration maturity is the integrative mechanism through which AI and sustainability are embedded. Rather than treating AI or sustainability as external domains, this study shows that their successful adoption depends on the maturity of collaboration processes, behaviours, structures, and technologies.

The current maturity profile reveals strategic gaps which block AI-driven sustainability alignment, integration gaps which hinder AI and sustainable digital infrastructure, process gaps that slow the adoption of AI-based optimisation and sustainable workflows, and cultural strengths which enable digital collaboration despite structural weaknesses. This suggests that organisational progress towards AI-enabled sustainable transformation will depend on strengthening the strategy-technology-process nexus, while leveraging cultural strengths to accelerate adoption.

5.2. TO-BE State of Digital Collaboration, AI, and Sustainability

5.2.1. AI for Sustainable Digital Transformation Through Improved Collaboration

In the TO-BE state, AI becomes an embedded component that enhances each maturity dimension. Consistent with STS (Pasmore et al., 1982) and the S–T model (Leavitt, 1965), AI acts across structure, technology, tasks, and people simultaneously. Collaboration serves as the integration point through which sustainability and AI can reinforce each other. AI-supported collaboration patterns reduce digital waste, communication overload, cloud storage demands, and redundant workflows—aligning with sustainability insights from Khan et al. (2025), Rusilowati et al. (2024), and Brioschi et al. (2021). Thus, collaboration maturity becomes a lever for organisational sustainability (Schwaeke et al., 2025).

5.2.2. AI and Sustainability in Inventorying Digital Collaboration Tools

AI improves the completeness and accuracy of tool inventories by mapping tool usage, identifying shadow tools, detecting unused licences, and revealing hidden dependencies (Aldoseri et al., 2024; Olaniyi et al., 2024; Schubert & Williams, 2022). These capabilities reduce digital waste and unnecessary resource consumption (Bankins et al., 2024; Linnes, 2020). AI can additionally assess the sustainability footprint of communication patterns or cloud providers (Schallmo & Williams, 2018; Nitschke & Williams, 2020).

5.2.3. AI and Sustainability in Creating the Landscape of Digital Tools in Use

AI helps determine whether single-core, dual-core, or distributed platform configurations offer the best balance of collaboration efficiency and environmental impact (Ivančić et al., 2019; Schubert & Williams, 2022). Process mining removes bottlenecks and redundant loops (Hilger & Wahl, 2022), reducing digital waste and cloud load (Rusilowati et al., 2024; Brioschi et al., 2021). By enabling technical, structural, and behavioural alignment, AI-driven integration operates exactly as a sociotechnical mechanism reshaping collaboration patterns.

5.2.4. AI and Sustainability in Assessing Digital Collaboration Maturity

AI enhances maturity assessment by synthesising quantitative KPIs with qualitative interview insights (Koesten et al., 2019; Hilger & Wahl, 2022). While SPSS was used to compute scores, AI supported qualitative synthesis (Helfferich, 2019; Robinson, 2022), identifying patterns such as fragmentation, wasteful routines, and low levels of AI utilisation. In the TO-BE state, VR simulations (Siemon et al., 2020), benchmarking (Warner & Wäger, 2019; Aldoseri et al., 2024), and long-term monitoring (Nitschke & Williams, 2020; Schubert & Williams, 2022) can enhance evaluation of sustainable and AI-enabled collaboration capabilities.

5.2.5. AI and Sustainability in Managing Digital Collaboration Improvement Projects

AI contributes to ongoing improvement by offering role-specific insights, personalising development pathways, automating monitoring, and supporting sustainable workflows (Hilger & Wahl, 2022; McComb et al., 2023). This aligns with findings on leadership competence as a critical success factor for AI-enabled transformation (Min & Kim, 2024). Embedding sustainability KPIs and AI-enabled governance in collaboration routines helps maintain long-term renewal (Warner & Wäger, 2019; Schallmo & Williams, 2018; Schwaeke et al., 2025).

6. Conclusions

The designed digital collaboration improvement framework integrates the dimensions of strategy & structure, technology, culture & behaviour, and management & processes. This study makes an academic contribution by integrating AI and sustainability into the theory of digital collaboration maturity. Managerially, it provides a structured roadmap for improving collaboration efficiency. Societally, it advances understanding of how digital transformation supports the SDGs. By aligning digital tools with collaborative processes, the article addresses a critical gap in the scholarly literature concerning the application of digital transformation in real-world business settings through four phases: inventorying digital collaboration tools, creating the landscape of digital tools in use, assessing digital collaboration maturity, and managing digital collaboration improvement projects.

In addition to these contributions, this study clarifies why existing collaboration maturity models are insufficient for today’s AI-augmented and sustainability-oriented environments. Prior models do not account for algorithmic orchestration, digital resource efficiency, or sustainability metrics embedded directly into collaboration workflows. By explicitly embedding AI capabilities and sustainability mechanisms across all maturity dimensions, this framework advances beyond configurational integration and provides a theoretically grounded extension of sociotechnical systems and the S-T model for the contemporary digital workplace.

AI further supports the effectiveness and sustainability of digital collaboration by using network analysis, recommendation systems, simulations, machine and deep learning techniques, as well as generative features to optimise strategies, reduce tool redundancies and digital clutter, lower carbon footprint, track sustainability metrics, ensure compliance to sustainability policies and automate tasks, decreasing workload and digital fatigue, and increasing digital collaboration sustainability and effectiveness. In the article, a solid number of AI use cases for enhancing digital collaboration are presented. They serve as a roadmap towards sustainable AI integration into digital collaboration management and practices.

This study, while comprehensive in its approach and valuable in its scientific and practical contributions, is subject to several limitations. The proposed framework follows the widely accepted view that digital collaboration should rely on one or two core platforms supported by complementary tools. Yet, in smaller organisations, relying on fewer digital tools may be more financially and sustainably sound than establishing a full collaboration suite—an aspect worth exploring in future research. As the organisation is now entering the implementation phase of the improvement plan, future research will collect proxy sustainability indicators to empirically validate the expected reductions in digital waste and carbon footprint. Next, as the maturity dimensions are formative, this study does not conduct CFA or AVE analyses, which are inappropriate for formative models. Instead, the instrument is used to assess organisational maturity, develop the digital collaboration improvement plan, and monitor its implementation. Additionally, the study does not analyse AI implementation risks in detail, such as privacy concerns, robustness, explainability, and trustworthiness. Its focus lies on opportunities to enhance digital collaboration for greater sustainability and effectiveness, while acknowledging that a deeper understanding of related risks remains an important task for future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S.; methodology, I.S. and J.M.E.; software, J.M.E.; validation, I.S. and J.M.E.; formal analysis, J.M.E.; investigation, I.S. and J.M.E.; resources, I.S. and J.M.E.; data curation, J.M.E.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.E.; writing—review and editing, I.S.; visualization, I.S.; supervision, I.S.; total, 80% I.S., 20% J.M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the provisions of the Guidelines for the Evaluation of Compliance with Research Ethics approved by the Office of the Ombudsperson for Academic Ethics and Procedures of the Republic of Lithuania (Order No. V-60, 2020, as amended in 2021), which state that ethics committee or Institutional Review Board approval is not required for non-interventional social research based solely on voluntary participation and informed consent (Point 27). The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 2013).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are confidential.

Acknowledgments

A short version of the article was presented at the 2nd International Conference on Advancing Sustainable Futures, held on 11–12 December 2024, in Abu Dhabi, as an oral presentation, and the abstract was published in the conference proceedings. The preprint of the longer, pre-current version of the manuscript is available at DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.5385869. During the preparation of this work, the authors used R Discovery for the purpose of searching the topic-relevant literature, and Grammarly for the purpose of improving the readability of the article. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CARL | Context, actions, results, learnings framework |

| ECP | Enterprise collaboration platform |

| IBM | International Business Machines Corporation |

| PwC | PricewaterhouseCoopers |

| SDG | Social development goal |

| VR | Virtual reality |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Digital Collaboration Maturity Assessment—Dimension Strategy & Structure

Table A1.

Operationalisation of Business Strategy & Structure.

Table A1.

Operationalisation of Business Strategy & Structure.

| Factor | Maturity 1 | Maturity 2 | Maturity 3 | Maturity 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration Guidelines | No guidelines; practices vary manually | Basic guidelines; limited coordination; no AI; no sustainability focus | Clear guidelines; partly AI-informed; reduced redundant workflows | AI-supported guidelines aligned with sustainability policies and digital waste reduction |

| Goal Congruence | Collaboration goals undefined | Goals partially shared; limited transparency | Clear alignment via shared tools and AI dashboards | High alignment with AI-enabled visibility of objectives and sustainability KPIs |

| Collaboration Strategy | No defined strategy | Fragmented strategy; no AI or sustainability linkage | Explicit strategy with selective AI-supported processes | Org-wide strategy integrating AI-enabled collaboration and sustainable digital practices |

| Collaboration Depth | Low interdependence; manual communication | Some interdependence; limited automation | AI-assisted workflow optimisation | High-synergy collaboration with AI-enabled patterns and sustainable digital behaviours |

| Collaboration Scope | Collaboration limited to individuals | Collaboration across teams | Cross-departmental collaboration with AI-enabled routing | Cross-organisational collaboration using secure AI tools and sustainable data practices |

| Integration of Tools | No integration | Minimal integration; no AI optimisation | Solid integration with some AI interoperability | AI-optimised integration reducing duplication and digital waste |

| Alignment with Corporate Strategy | Unrelated to strategy | Partial alignment | Good alignment incl. AI-guided insights | Strong alignment incl. AI-supported sustainability transformation |

Appendix A.2. Digital Collaboration Maturity Assessment—Dimension Management & Processes

Table A2.

Operationalisation of Management & Processes.

Table A2.

Operationalisation of Management & Processes.

| Factor | Maturity 1 | Maturity 2 | Maturity 3 | Maturity 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition & Reward | No recognition | Occasional recognition | Recognition in performance processes; AI tracking possible | Strong recognition tied to AI analytics and sustainability behaviours |

| Leadership Involvement | Leaders not involved | Limited involvement | Leaders model collaborative practices; partial AI insights | Strong leadership using AI dashboards for sustainable collaboration |

| Managerial Support | No support | Inconsistent support | Effective support incl. AI-based tools | Strategic coaching using AI insights to reduce fragmentation and waste |

| Support & Awareness | No support structure | Some awareness | Clear support; AI-enabled bottleneck monitoring | Institutionalised support incl. AI workflow improvement and sustainability practices |

| Joint Performance Evaluation | No joint evaluation | Limited joint focus | Joint performance measured; AI tracks links | Robust evaluation incl. AI indicators and sustainability KPIs |

| Employee Training | No training | Basic training | Comprehensive training incl. AI recommendations | Personalised AI-driven training incl. sustainable tool practices |

Appendix A.3. Digital Collaboration Maturity Assessment—Dimension Technology

Table A3.

Operationalisation of Technology.

Table A3.

Operationalisation of Technology.

| Factor | Maturity 1 | Maturity 2 | Maturity 3 | Maturity 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tool Exploration | No exploration | Limited exploration | Active exploration incl. AI features | Continuous exploration of AI innovations and sustainable tool alternatives |

| Technology Readiness | Tools unavailable | Basic availability | Mature availability with some automation | AI-enhanced infrastructure with energy-efficient cloud options |

| Workflow Integration | Not integrated | Partially integrated | Integrated with AI-driven optimisation | AI-orchestrated workflows reducing redundancy and digital waste |

| Daily Use | Rarely used | Occasionally used | Frequently used incl. AI features | Embedded daily use with AI-enabled sustainable patterns |

| Tool Uniformity | Fragmented tools | Some uniformity | High uniformity via governance | AI-optimised uniformity reducing tool sprawl and digital waste |

| Organisation-wide Sharing | Inefficient sharing | Partially efficient | Effective sharing | AI-enhanced sharing with sustainable data practices |

| Tool IT Integration | Not integrated | Poorly integrated | Well integrated with some AI connectors | AI-supported interoperability and optimised cloud utilisation |

| Contribution of Tools | Low contribution | Moderate contribution | Strong contribution incl. AI automation | High contribution incl. AI and sustainability-optimised processes |

| Employee Requirements | Poor match | Partial match | Good match using usage analytics | AI-personalised and sustainability-optimised configuration |

| User Experience | Poor | Fair | Good with AI usability features | Excellent UX incl. AI assistance and low-waste workflows |

| Cybersecurity | No trust | Limited trust | Moderate trust with standard protection | High trust with AI threat detection and sustainable cloud policies |

Appendix A.4. Digital Collaboration Maturity Assessment—Dimension Culture & Behaviour

Table A4.

Operationalisation of Culture & Behaviour.

Table A4.

Operationalisation of Culture & Behaviour.

| Factor | Maturity 1 | Maturity 2 | Maturity 3 | Maturity 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment & Availability | Low commitment | Inconsistent availability | Strong commitment with AI workload transparency | Very high commitment incl. sustainable collaboration habits |

| Collaboration Satisfaction | Not satisfied | Somewhat satisfied | Satisfied with AI-assisted coordination | Highly satisfied with AI-enhanced flow and reduced friction |

| Collaboration Responsibility | Rarely responsible | Sometimes responsible | Often responsible with AI-enabled task clarity | Strong responsibility incl. sustainable digital norms |

| Inter-Departmental Interaction | Rare interaction | Occasional interaction | Frequent AI-enabled routing | Intensive cross-unit collaboration with sustainable practices |

| Team Collaboration Support | No support | Partial support | Good support with AI-enabled coordination | Strong support incl. sustainable team behaviour expectations |

| Company Collaboration Culture | Weak culture | Emerging culture | Strong culture supported by digital transparency | Very strong culture with responsible AI use and sustainability norms |

| Collaboration Trust | Low trust | Some trust | High trust supported by AI transparency | Very high trust supporting sustainable collaboration |

References

- Aldoseri, A., Al-Khalifa, K. N., & Hamouda, A. M. (2024). AI-powered innovation in digital transformation: Key pillars and industry impact. Sustainability, 16(5), 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankins, S., Ocampo, A. C., Marrone, M., Restubog, S. L. D., & Woo, S. E. (2024). A multilevel review of artificial intelligence in organizations: Implications for organizational behavior research and practice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(2), 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, M., Hu, X., Hinds, R., & Valentine, M. (2022). A “Distance matters” paradox: Facilitating intra-team collaboration can harm inter-team collaboration. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(CSCW1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughzala, I., & de Vreede, G.-J. (2015). Evaluating team collaboration quality: The development and field application of a collaboration maturity model. Journal of Management Information Systems, 32(3), 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brioschi, M., Verga, E. S., Fuggetta, A., Zuccalà, M., Fabrizio, N., & Bonardi, M. (2021). Enabling and promoting sustainability through digital API ecosystems: An example of successful implementation in the smart city domain. Technology Innovation Management Review, 11(1), 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Insider. (2020, February 10). Slack just scored its biggest customer deal ever, as IBM moves all 350,000 of its employees to the chat app. Business Insider. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/ibm-slack-partnership-customer-digital-transformation-2020-2 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, R., Gardner, H., & Crocker, A. (2019, March). Networks for agility: Collaborative practices critical to agile transformation. Connected Commons. Available online: https://connectedcommons.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/networks-for-agility.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- De Clercq, D., Dimov, D., & Thongpapanl, N. (2011). A closer look at cross-functional collaboration and product innovativeness: Contingency effects of structural and relational context. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28(5), 680–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A. R., Lakhiwal, A., & Sachdeva, A. (2023). AI agents as team members: Effects on satisfaction, conflict, trustworthiness, and willingness to work with. Journal of Management Information Systems, 40(2), 307–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A., & Winklhofer, H. M. (2001). Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, S., & Hevner, A. R. (2013). Positioning and presenting design science research for maximum impact1. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummer, D. (2017). Strategic change design to leverage the potential of digital workplaces for effective collaboration [Master’s thesis, NHH Norwegian School of Economics]. Available online: https://openaccess.nhh.no/nhh-xmlui/handle/11250/2454060 (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Helfferich, C. (2019). Leitfaden- und experteninterviews. In N. Baur, & J. Blasius (Eds.), Handbuch methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung (pp. 669–686). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar]

- Hilger, J., & Wahl, Z. (2022). Making knowledge management clickable: Knowledge management systems strategy, design, and implementation (1st ed.). Springer International Publishing. ISBN -13 978-3030923846. [Google Scholar]

- Ivančić, L., Spremić, M., & Vukšić, V. (2019). Mastering the digital transformation process: Business practices and lessons learned. Technology Innovation Management Review, 9(2), 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, C. B., Mackenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2003). A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., Rahman, A., Mahmud, F. U., Bishnu, K. K., Ahmed, M., Mridha, M. F., & Aung, Z. (2025). A systematic review of AI-driven business models for advancing sustainable development goals. Array, 28, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koesten, L., Simperl, E., Kacprzak, E., & Tennison, J. (2019, May 4–9). Collaborative practices with structured data. CHI ‘19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Paper No. 100, pp. 1–14), Scotland, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L. S., & Newman, D. A. (2023). Construct development and validation in three practical steps: Recommendations for reviewers, editors, and authors. Organizational Research Methods, 26(4), 574–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, H. J. (1965). Applied organizational change in industry: Structural, technological, and humanistic approaches. In J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations. Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, U. (2020). Five maturity levels of managing AI: From isolated ignorance to integrated intelligence. Journal of Innovation Management, 8(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnes, C. (2020). Embracing the challenges and opportunities of change through electronic collaboration. International Journal of Information Communication Technologies and Human Development, 12(4), 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, I., Oliveira, A., & Costa, C. J. (2015). Tools for online collaboration: Do they contribute to improve teamwork? Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruping, L. M., & Magni, M. (2015). Motivating employees to explore collaboration technology in team contexts. MIS Quarterly, 39(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P., & Gläser-Zikuda, M. (2008). Die praxis der qualitativen inhaltsanalyse (2nd ed.). Beltz Pädagogik. [Google Scholar]

- McComb, C., Boatwright, P., & Cagan, J. (2023). Focus and modality: Defining a roadmap to future AI-human teaming in design. Proceedings of the Design Society, 3, 1905–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstein, B., & Chapel, T. (2023). 4. Developing a framework or model of change. The Community Tool Box. Available online: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/4-developing-framework-or-model-change (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Min, S., & Kim, B. (2024). Adopting artificial intelligence technology for network operations in digital transformation. Administrative Sciences, 14(4), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, C. S., & Williams, S. P. (2020, January 7–10). Monitoring and understanding enterprise collaboration platform outcomes and benefits change. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2020, Maui, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Olaniyi, O. O., Adigwe, C. S., Olaniyi, F. G., Arigbabu, A. T., & Ugonnia, J. C. (2024). Digital collaborative tools, strategic communication, and social capital: Unveiling the impact of digital transformation on organizational dynamics. Asian Journal of Research in Computer Science, 17(5), 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasmore, W., Haldeman, J., Shani, A., & Francis, C. (1982). Sociotechnical systems: A North American reflection on empirical studies of the seventies. Human Relations, 35(12), 1179–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, M., Fergurson, J. R., Krishen, A. S., & Gironda, J. T. (2024). Exploring AI technology and consumer behavior in retail interactions. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 23(6), 3132–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeb, S. (2023). A maturity model for intraorganizational online collaboration. International Journal of E-Collaboration, 19(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. (2022). Ace your interviews with the CARL framework of reflection. Crowjack. Available online: https://crowjack.com/blog/strategy/reflection-models/carl-framework-of-reflection#overview-of-carl-framework-of-reflection (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Robra-Bissantz, S. (2020). E-collaboration: Mehr digital ist nicht weniger Mensch. In T. Kollmann (Ed.), Handbuch digitale wirtschaft (pp. 213–239). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusilowati, U., Wahyudin Anugrah, R., Rasmita Ngemba, H., Fitriani, A., & Dian Astuti, E. (2024). Leveraging AI for superior efficiency in energy use and development of renewable resources such as solar energy, wind, and bioenergy. International Transactions on Artificial Intelligence (ITALIC), 2(2), 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, R. B., Safie, N., Abd Rahman, A. H., & Goudarzi, S. (2021). Artificial intelligence maturity model: A systematic literature review. PeerJ Computer Science, 7(6), e661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallmo, D. R., & Williams, K. (2018). Digital transformation now! Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, P., & Williams, S. P. (2022). Enterprise collaboration platforms: An empirical study of technology support for collaborative work. Procedia Computer Science, 196, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaeke, J., Kanbach, D. K., Gast, J., Nguyen, H. L., & Gerlich, C. (2025). Artificial intelligence (AI) for good? Enabling organizational change towards sustainability. Review of Managerial Science, 19(10), 3013–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, G. (2001). What goes around, comes around: Inventing a mythology of teamwork and empowerment. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 37(1), 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemon, D., Li, R., & Robra-Bissantz, S. (2020, December 13–16). Towards a model of team roles in human-machine collaboration. International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2020), Hyderabad, India. [Google Scholar]

- Vatamanu, A. F., & Tofan, M. (2025). Integrating artificial intelligence into public administration: Challenges and vulnerabilities. Administrative Sciences, 15(4), 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K. S. R., & Wäger, M. (2019). Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Planning, 52(3), 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschull, S., & Emmanouilidis, C. (2022). Development and application of a human-centric co-creation design method for AI-enabled systems in manufacturing. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 55(2), 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.