Abstract

Background and aim: This study examines the impact of the digital world on the purchasing behaviour of Generation Z, with a specific focus on the Slovak context. While existing literature often analyses global or non-Slovak populations, this work provides a contextually grounded analysis of how digital exposure, online marketing communications and social networks shape the purchasing preferences of Slovak Generation Z consumers. Novelty and contributions: First comprehensive analysis in Slovakia linking digital environment exposure, social media marketing communications, and Generation Z purchase preferences within a clearly defined national context. We integrate context-specific variables (local digital infrastructure, cultural norms, and marketing practices) to identify regionally relevant determinants of online consumer behaviour. We formulate and test hypotheses about the interactions between digital experiences and online marketing channels to produce actionable insights for Slovak marketers and e-commerce platforms. Research problem and uniqueness: Problem: How do specific elements of the digital environment influence the purchasing decisions of Generation Z in Slovakia, and which online channels and content types are most effective for this demographic in the local context? Uniqueness: No prior Slovak study has systematically mapped the interrelations between digital exposure, marketing communication on social networks, and purchasing preferences of Generation Z in a local setting. This work contributes to understanding culturally and economically specific factors shaping digital purchasing behaviour in Slovakia. Methods: Quantitative study based on a questionnaire survey with a representative Slovak sample. Hypotheses are tested using appropriate statistical analyses to explore relationships between digital exposure, social network marketing communications, and Generation Z purchasing preferences. Expected results and practical implications: Identification of the most influential digital channels and content types for Slovak Generation Z consumers. Practical recommendations for local brands and e-commerce platforms to optimise digital campaigns targeting Slovak youth; insights into cultural nuances in consumer behaviour within Slovakia.

1. Introduction

In today’s modern era, when the market is evolving more dynamically than ever before, the so-called digital world is an integral part of its existence, accompanying today’s consumers of different demographic categories daily. With the growth of e-business, economic theory is being enriched by insights gained from analyses of consumer behaviour in the online space. Along with the popularity of various e-business models and the popularity of conducting purchasing activities in this space, marketing strategies have also started to evolve over time, with the main objective of captivating potential consumers through various modes of marketing communication with the help of marketing tools (; ).

The present paper is devoted to the analysis of the impact of the existence of the digital world on a specific demographic of individuals with the attribute of “digital natives”, i.e., Generation Z. This is a generation of individuals born between 1997 and 2013, whose defining characteristic is their everyday activity in the digital space (; ).

The objectives of the paper are also related to the fact that there are certain gaps in research. These include the lack of existing studies in the Slovak Republic. Furthermore, the area of investigation is limited geographically, as is the fact that the research focuses on several areas (e.g., social status, behaviour in the digital environment, marketing communication, social networks, and preferences in the digital shopping space), which means that other aspects of the purchasing behaviour of Generation Z may not yet be explored. When focusing on Generation Z, it is possible that comparisons with other generations or age groups are missing, which would increase the complexity and depth of the research, which, however, requires work on another new project in the future. We consider the fact that these gaps create space for further research and expansion of knowledge in the impact of the digital world on purchasing behaviour in the Slovak context.

The generation of consumers born between these years is also known as the “Digitally Active” generation. They grew up with access to modern media and technology and are tech-savvy (). Existing in the digital world is natural for this generation using technology, the internet and social networking from a young age (; ). This target group consumes content more than any other age group, spending nearly 11 h a day reading, liking, and sharing material on all their devices (). They are very likely to be exposed to digital advertising on social media and check Instagram at least five times a day. This target group prefers to communicate using images as opposed to the previous generation who communicate using text and are looking for innovative content. ().

Several different characteristics of Generation Z have been identified in the literature. Members of this group are eager consumers of technology and desire a digital world (; ). As true digital natives and the only generation raised solely under the influence of technology, Generation Z has become very accustomed to interacting, sometimes exclusively, in the digital world (). Due to their frequent use of technology, they have underdeveloped social and relationship-building skills, putting them at increased risk of isolation, insecurity, and mental health issues such as anxiety and depression (). Their technological habits lead them to have a limited ability to concentrate, and they quickly become ‘bored’ when they perceive monotony and repetition. Generation Z prioritizes convenience and quick results, while also being characterized by a pragmatic approach to decision-making. Because this generation grew up in a period of social, political, and economic uncertainty, it is characterized by increased caution and an emphasis on emotional, physical, and financial security. Generation Z is often described as educated, socially and environmentally conscious, but more stressed with a higher propensity for depression compared to older generations (). Individuals have high expectations of themselves that largely end up unfulfilled ().

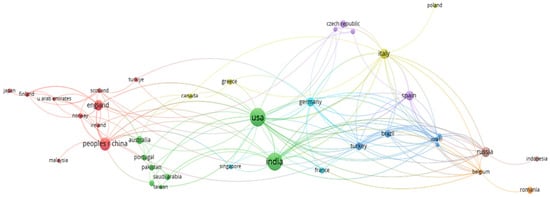

The present paper contains a body of key knowledge from different economic disciplines. It is about concepts such as consumers and consumer behaviour and the factors influencing consumer behaviour. Relevant disciplines deal with modern aspects of consumer existence in the digital world, which are directly related to concepts such as digital marketing and its tools. The paper focuses on Generation Z consumers, which is one of the categories of today’s breakdown of individuals in society depending on the interval of years in which they were born. The findings from the literature described below include the perceptions of different sub-issues by different experts in the field. Since the aim of the paper is to identify the effects of the digital world on Generation Z in the Slovak environment, it was necessary to draw on a comprehensive database of scholarly articles and publications to accurately define the modern perception of Generation Z as a consumer. As can be seen from the bibliographic map depicted in Figure 1, the Slovak Republic is not one of the countries where the issue of the digital world has been extensively addressed by authors.

Figure 1.

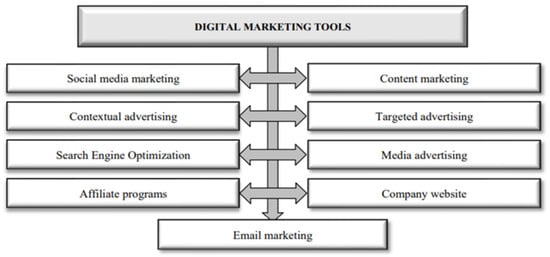

Digital marketing tools.

1.1. Literature Review

As stated in the author’s publication (), the theory of consumer behaviour in deterministic situations, as set out, for example, by Debreu in 1959–1960 or Uzawa in 1960, is “a jewel in a glass case”. It is the product of a long process of refinement from the utilitarian theorists of the 19th century through Slutzky and Hicks-Allen to the economists of the last 25 years. It has been stripped of all irrelevant postulates, so that it now serves as an example of how to achieve the minimum results from the minimum assumptions. This provoked a response from Johnson in 1958, who suggested with a touch of sarcasm that the determinacy of the sign of the substitution effect (the only substantive result of the theory of consumer behaviour) could be derived from the assumption that goods are goods. People will buy these goods, and it is the seller’s job to sell them to him. Ultimately, the customer will decide to buy what suits him best ().

One view of marketing is about making the consumer aware that he wants a certain product, even though he may not want it initially. Therefore, it is important for marketers to understand how consumers behave when exposed to advertising methods and messages (). Consumers try to make rational decisions when making purchases. This is a process that is influenced by a number of factors such as cultural, social and psychological factors: needs and wants (first, the consumer tries to identify what commodities they would like to consume), choice (they then select the commodities that will bring them the most benefit from the whole offer), budget estimation (they then estimate the funds available for purchase) and price analysis (finally, they analyse the current prices of the commodities and decide which ones to buy (; ). Research on consumer behaviour allows for a better understanding of not only what people buy, but also their purchase motivations and purchase frequency (). One of the underlying assumptions of this research is that people often buy products not for their main function, but for their subjectively perceived value (). Consumer perception of a product is often subjective as it is influenced by a variety of personal, psychological and situational factors (). Nowadays, consumer theory is already taking on new dimensions in terms of analysing consumer behaviour in the online space. Digital marketing can be understood as the activities, processes and institutions facilitated by digital technologies to create, communicate and deliver value to customers and other stakeholders (; ).

According to (), digital marketing differs from traditional marketing in several key aspects. It aims to reach consumers online through various channels such as websites, social media, search engines and email. This allows it to reach a much wider audience and target campaigns to specific groups of people based on their interests and behaviours (). Digital marketing has several advantages over traditional marketing. It is cheaper, allows for a higher return on investment and delivers better results. In addition, it allows for building relationships with consumers and engaging them in conversation, leading to a more loyal client base (). Consumers are an essential part of the functioning of the market, as they bring revenue to businesses, without which their functioning would become impossible () A consumer is defined as one who acquires goods not for the purpose of resale, but for the purpose of final consumption (). The category of potential consumers also plays an important role. These are customers who are at the very beginning of the purchase decision process, i.e., they have not decided to make a purchase (). It should be the priority of the retailer to keep the customer’s interest up to the point where he is willing to make a purchase and to use different communication channels (). Prospective customers, given the right business decision making and customer service, have great potential to become loyal customers ().

According to (), the following key facts are important for successful customer outreach: building a strong relationship with the customer, high emphasis on customer service and simplifying accessibility (web, app, payment methods). Consumer behaviour, its dynamics and elasticity with respect to social, cultural, psychological and other factors, is a fundamental element of marketing overall as a discipline (). Thus, it is a complex multidisciplinary marketing activity that involves the investigation of the purchase decision-making process in the pre-purchase stages and the associated perspectives, emotions, attitudes and final decisions of consumers (). The course of the decision-making process influences the final customer decision. According to () there is a wide range of factors that can largely influence this course, such as current trends, market changes, demographic conditions, consumer lifestyles, buying habits, and so on. The authors () consider these factors as external and internal. Internal factors include psychological factors, motivational, perception and attitudes. These factors influencing consumer behaviour are important in deciding the target groups to whom the company wants to sell the products. It is impossible to reach all groups of consumers with the same advertisement, design or any other parameter of products, so a company should also consider its capabilities and abilities when targeting and try to get to know the potential target groups better (). The external factors are mainly due to changes in the market environment and include cultural and social influences, marketing, purchasing power and consumer willingness (). The purchasing decision process is an important and topical issue. Generally, this process is defined as the time course of making a purchase from the actual emergence of the need to the evaluation of the investment made or the purchase of goods. The author () defines the sequence of its steps as follows: identifying the need, searching for information, evaluating alternatives, making the purchase, and evaluating the decision. These steps are also applicable in digital marketing. This type of marketing has a greater capacity for segmentation and different communication, which makes it more economical compared to traditional marketing. It is important to note that it differs from traditional marketing because it uses the Internet as a tool to build relationships with customers in an original way in accordance with the individual needs and desires of each consumer (). The differences are mainly related to the mode of communication, namely the media through which the marketer communicates with consumers.

Digital marketing uses modern internet-connected technologies for its marketing communication, which means that through the collection of browsing data, known as cookies, companies can carry out targeting at the individual level virtually passively () Information about products and services thus reaches potential customers incomparably more efficiently and quickly in digital marketing than in traditional marketing. The latter, even when businesses try to target potential prospects, does not achieve the same effectiveness. To maintain and optimize the digital marketing function, businesses use a set of modern online tools fulfilling different purposes. In general, the goal of digital marketing is to maximize the effectiveness of advertising messages for a specific customer segment (; ). The ability and flexibility of businesses to respond to the current market situation almost instantaneously is needed. To achieve this level of flexibility in the modern era, enterprises use a set of digital tools and software solutions that help to enhance the performance of promotion. According to (), the ultimate effect of using tools is to gain and maintain attention, interact with recipients (customer communication) and engage in the senses. The tools that can be used in digital marketing are shown in Figure 1.

These are the most popular and widely used tools in digital marketing ().

It can be stated that they represent the means, techniques and platforms that organizations use to promote their products and services in the online environment. Their goal is to reach a target audience, build relationships with customers and increase sales or brand awareness. Their classification can be expanded to include the dimension of the goals that are to be achieved when using them. They are shown in the following Table 1.

Table 1.

Digital Marketing Tools by Goals.

The main objective of a social media marketing campaign is to build brand awareness and trust, and it is also an effective sales channel. It is most often implemented on well-known social networks. The most common forms of marketing on social networks are so-called paid content in the form of images, short videos (reels), stories, etc. (; ). Such forms of promotion are the main reason why social networks are provided to users for free (). In the case of contextual advertising, it is a more targeted way of advertising compared to traditionally displayed online advertising. It displays ads relevant to the content of a given page to website visitors (). A key aspect of such advertising is its relevance to the page content being displayed or the user’s past online behaviour (). Search engine optimization describes a wide variation in techniques that companies use to increase traffic to their homepages and improve their rankings in web browser search results. The better ranking a page has, the more likely it is to be viewed and opened by users and to make a purchase decision (; ). Affiliate marketing is an advertising model consisting of rewarding third parties for generating traffic and leads to a seller’s homepage (). Affiliate entities are typically rewarded for sales generated because of the program, not for so-called click-through, i.e., erroneous clicks on an advertisement or impressions of the advertisement itself (). Content marketing includes any marketing communication with the market through modern technology for the purpose of impressing the customer. It represents a process whose main purpose is to create and distribute relevant online content to engage, attract and initiate interaction with a potential customer to make a sale of the provided good or service (; ). Targeted advertising is an effective media strategy to reach the target audience in the digital environment using the right tools. The data that are collected for the purpose of targeted advertising are mainly demographic (age, gender), geographic (country, city, region) and social (work, interests, hobbies, communities) (). Media advertising represents any marketing communication through available media channels. Over the last decade, its popularity has grown at a rapid pace, resulting in a decline in the popularity of traditional advertising communication, except for its most well-known forms such as billboards, posters, print advertisements, etc., although these have also suffered a decline in popularity ().

Websites represent a communication channel between consumers and retailers, as well as a sales platform through which transactions between the parties involved take place. Nowadays, a website represents an extremely versatile marketing tool, as it contains a portfolio, information about the goods and services provided, the manufacturer itself, contact details, or a so-called chatbot ().

Email marketing is a form of direct marketing which, using electronic mail, represents a method of communication between the consumer and the e-shop, which in the past has provided its email address for marketing purposes (). The best-known form of email marketing is the so-called newsletter, which informs the user about news in the form of new products, discounts, sales and so on ().

The above tools in the digital world have different impacts on different consumers. Their age plays a significant role. People are classified into so-called generations according to their age. In terms of marketing, businesses are interested in these generations primarily for targeting reasons. The following are mentioned in the literature: generation Z (18 to 27 years) (). Generation Y (28 to 43 years), generation X (44 to 59 years) and baby boomers (60 years and older) (). To each of the named generations there are also characteristic features in terms of consumer behaviour, tendencies and purchasing preferences. Because the paper is preferentially focused on Generation Z consumers, we define the characteristics of this generation in more detail.

Generation Z is referred to as the digitally active generation. Thus, it is becoming a significant purchasing force among consumers and in the business industry. Many individuals from this generation have lower incomes compared to older generations and have no offspring, which implies a different spending pattern and overall demand for different goods and services (). Generation Z has stricter views on shopping than other generations due to the amount of up-to-date information they draw from media sources (). This generation shows the highest level of criticality towards product quality. When shopping, they demand products with low negative environmental impact. They are willing to spend more on sustainable products of higher quality (). Generation Z prefers more careful financial management and shows higher sensitivity to price factors in purchasing decisions. Although Generation Z prefers a higher quality, more expensive and more sustainable product, they seek more prudent financial management based on the experience of older generations (). At the same time, they use social media not only for seeking relaxation or entertainment, but also for obtaining information, inspiration, researching shopping options and forming relationships with brands present on social media. Generation Z harbours scepticism about advertising and seeks authentic, transparent and trustworthy communication with the entities they buy from. They place a high value on online reviews and recommendations from those close to them. Trust in the retailer and its moral and ethical correctness have been shown to influence the purchasing tendencies of these consumers ().

Traditional advertising does not have a significant effect on Generation Z’s buying behaviour. Consumers prefer marketing communication via the Internet and social networks, but Facebook and Twitter (X) do not have a great influence on them compared to video advertising on Instagram (). Generation Z seeks authenticity, directness and transparency in their shopping experience, which is why influencer marketing has the highest success rate (; ). This generation seeks recommendations from popular influencers whose views and values they share. This sets the stage for interest in influencer-recommended products ().

The aim of this paper is to evaluate the influence of the digital world on the purchasing behaviour of consumers belonging to Generation Z in a study conducted in the conditions of the Slovak Republic. Since no similar research has been published in the Slovak Republic, we will try to fill this gap through our findings.

The following bibliometric map (Figure 2) shows that a lot of emphasis is currently being given to the digital world. We have looked at which country the most scholars are working on digital world issues.

Figure 2.

Frequency of addressing the digital world vs. generation in terms of countries. Source: authors’ research in the VosViewer 1.6.2031 program.

1.2. Reliability and Validity of the Research Instrument

To strengthen the scientific rigor of the study, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire were examined.

Reliability. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha for each thematic block of the questionnaire (digital world habits, shopping behaviour, advertising, social networks, and consumer preferences). All constructions achieved acceptable reliability coefficients above the threshold of 0.70, indicating that the items within each dimension consistently measured the same underlying concept. Items with lower item–total correlations were reviewed, and no removal was necessary, as their contribution did not significantly reduce internal consistency.

Validity. Several types of validity were evaluated:

Content validity was ensured through the derivation of questionnaire items from established literature in consumer behaviour, digital marketing, and Generation Z research.

Construct validity was examined using exploration factor analysis (EFA), which confirmed that items loaded strongly (>0.60) on their respective factors, supporting the dimensionality of the instrument.

Convergent validity was confirmed by average variance extracted (AVE) values above 0.50, indicating that each construct explained more variance than measurement error.

Discriminate validity was verified by comparing the square root of AVE with inter-construct correlations, confirming that constructs were sufficiently distinct from each other.

Criterion validity was supported by significant correlations between relevant constructions and behavioural outcomes (e.g., frequency of online shopping, preference for influencer marketing), which align with theoretical expectations.

Overall, the reliability and validity analyses confirmed that the survey instrument is a robust and scientifically reliable tool for investigating the purchasing behaviour of Generation Z in the digital environment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reliability and Validity of Constructs.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology is based on the aim of the paper. To achieve the most accurate and relevant results, we have opted for a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches. To collect relevant data, we used the method of inquiry in the form of a questionnaire. The questionnaire sent out was anonymous and people over 18 years of age could participate in its completion. We distributed the questionnaire through electronic means between 15 January 2025 and 30 April 2025. The questionnaire was preferentially distributed among university and high school students, who were given the questionnaire to fill out through social networks, by sharing it in online groups created for this purpose, and through high school teachers who provided the questionnaire to their students for elaboration. We followed the following Formula (1) () to identify the minimum research sample:

where

- Z

- value from statistical tables,

- p

- shares of the character,

- c

- permissible range of errors,

- n

- sample size.

After plugging the above values into Formula (1), we obtain the following result concerning the minimum research sample.

The result of the formula indicates a value of 384.16, which implies that a sample size of 385 respondents is necessary for the purpose of the research. However, for data relevance, we need 385 complete questionnaires only from respondents falling into category Z.

The evaluation of the questionnaire is supported by testing the stated hypotheses. To evaluate the impact of the digital world on the purchasing behaviour of Generation Z, several points of interest have been defined for the dependency analysis:

- time spent on social networks and frequency of online shopping,

- gender and effectiveness of advertising,

- gender and the intensity of the impact of the digital world,

- income and types of online platforms used,

- we also work with hypotheses on which to support our findings, working status and sustainability and ethical behaviour,

- gender and time spent online.

We defined the hypotheses in terms of the above categorical variables as follows:

- There is a statistically significant relationship between the time spent on social networking sites and the frequency of online shopping.

- There is a statistically significant relationship between gender and effectiveness of ads.

- There is a statistically significant relationship between gender and the intensity of influence of the digital world.

- There is a statistically significant relationship between the amount of income an individual earns, and the type of platforms used.

- There is a statistically significant relationship between employment status and the importance of sustainability and ethics to consumers.

- There is a statistically significant relationship between daily time spent on social media and the gender of the Generation Z consumer.

The verification of the established hypotheses was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics software 26. The hypotheses were tested for the existence of dependence of the categorical variables under study and, if proven, proceeded to determine its intensity. To test the hypotheses, the following tests were used:

Pearson’s Chi-Square test: this test was used in the cross-analysis to determine whether there is a dependence between the selected categorical variables.

Cramer’s V: This is a coefficient that allows us to quantify the strength of the relationship between two categorical variables. We interpret the results based on the p-value, which determines the significance of the test as follows:

- -

- p-value < 0.05 = The dependence between the categorical variables is statistically significant,

- -

- p-value > 0.05 = The relationship between the categorical variables is statistically insignificant.

If a statistically significant dependence between categorical variables is found, the strength of this dependence is interpreted as follows:

If the value is between 0 and 0.3, this indicates weak dependence.

If the value is between 0.3 and 0.8, it is a moderately strong dependence.

If the value is between 0.8 and 1, it is a strong dependence. If p ≤ α, we reject the null hypothesis because a lower p-value means that the null hypothesis is less likely.

Fisher’s Exact Test: this test is used when the conditions for the Chi-square test are not met, namely if more than 5% of all values in the contingency table are less than 5, or if there are zeros in the table. Fisher’s test calculates p-values based on the probability of all possible combinations in the contingency table having the same or more extreme marginal sums than the observed values (). In addition to the above, we also used multivariate analysis—logistic regression for higher interpretability. This analysis allows us to determine which demographic, and digital factors significantly influence the likelihood of frequent online shopping among Generation Z consumers.

3. Results

A total of 422 questionnaires were obtained from the survey. Of these, 403 were Generation Z respondents, 13 responses were Generation Y respondents, 4 were Generation X respondents, and 2 were Baby Boomers. Because the aim of this paper is to assess the impact of the digital world on the purchasing behaviour of Generation Z through analysis, we only worked with a sample of 403 questionnaires to analyse the results. The questionnaire was divided into the following sections: basic demographics, respondents’ social status, respondents’ digital world, marketing communication, social networks, and Generation Z preferences.

- Basic demographics

For analysing the buying behaviour of the target group, the elementary demographic data of the respondents was collected.

- Gender and age

The results of the questionnaire show that most of the respondents were female. Females reached a representation of 60.45% (244 respondents) and 39.55% were males (159 respondents). In terms of age, there is only one filtered category—Generation Z with 403 respondents.

- Social status of respondents

As an additional feature, we surveyed the social status and income of the respondents. Within the social status of the respondents, facts about their work and family status were collected. The income of the respondents represents their net monthly income in EUR.

- Working status

Considering the surveyed generation and its age, the working status of most of the respondents was made up of people with the working status of student. This type of relationship accounted for 61.44% of the total number of respondents (248). The second most frequently provided answer was permanent employment, i.e., the respondent is employed on a long-term basis under a contract with an employer. These individuals accounted for a total of 19.9% of respondents (80) and the third most common employment status among respondents was contract work represented by 8.71% of respondents (35). The remainder of the total is made up of the unemployed (14), self-employed (18), entrepreneurs (2), or those currently on maternity/parental leave (6).

- Marital status

The marital status of respondents may provide relevant data for further analysis, particularly in terms of their online shopping behaviour and the types of products they purchase. Considering the age group analysed, majority of the respondents at 63.43% (256) lived in a household with their parents. Such a fact presents the possibility that the respondents’ living expenses are minimal and can spend the available finances at their discretion on a variety of products depending on their needs, desires, interests, etc. The second largest group at 12.19% (49) were those living in a household with a boyfriend or girlfriend, i.e., these individuals are already partially or fully separated from their parents, which is most likely related to the change in spending patterns in the online space. 9.2% (37) of respondents lived alone in their own household and 7.96% (32) already had an established household in which they live with a partner and a child or children.

- Income of respondents

Respondents’ income greatly influences their general shopping habits, preferences, frequency of shopping, etc., not only in the online space. This is an important part of the questionnaire for analysing the shopping behaviour of Generation Z and the impact of the digital world on it. The income structure of the respondents corresponds to both their working status. However, nowadays, there are many ways and opportunities for members of Generation Z to earn an income even alongside their active studies. Almost half of the respondents indicated the possibility of a net monthly income of less than EUR 500 in the question. The total share of this group in the total number of respondents was 48.26% (194). Such a result was to be expected, given the proportion of respondents who are students. The second group with the highest representation was made up of people with a net monthly income of 500 to 1000 euros and accounted for a share of 26.87% (108). These are probably respondents employed on an agreement or employed on a contractual employment relationship of a long-term nature, i.e., permanent employment or part-time employment. The third group is made up of those with a net monthly income between 1000 and 2000 euros with a share of 21.39% (86) of the total number of respondents and the fourth group with a net monthly income above 2000 euros is represented by 3.48% (14) of the respondents. For the last two groups, it is possible to assume multiple simultaneous earning activities, entrepreneurship, investment activities, etc.

- The digital world of respondents

Within the digital world of the respondents, their online shopping habits, shopping preferences, and evaluations of positive and negative aspects of shopping in the digital world were investigated. In this way, it is possible to obtain a picture of the preferences of Generation Z individuals, who spend the most time in the online space among the different generations and for whom online shopping and surfing the internet is a natural part of life.

- Frequency of shopping

Based on their income, marital status, preferences and other factors, Generation Z individuals participate in online shopping at different frequencies throughout the year. About one-third of the respondents, namely 32.59% (131) shop online once a month. A substantial proportion of respondents indicated the option of more than once a month with a proportion of 26.62% (107). 22.89% (92) of the respondents indicated the answer of more than once a year. Only 7.71% (31) indicated that they shop once a week, the highest frequency of shopping among the options provided. A total of 18 respondents indicated that they shop more than once a week. Similarly, 18 respondents stated that they shop only once a year. 1% (4) of the respondents do not shop online and 0.25% (1) stated the option of other. Based on the findings from the questionnaire, it can be argued that the intensity of online shopping is relatively high for Generation Z.

So, according to the results of the questionnaire survey among members of Generation Z, it can be stated that most respondents already have regular experience with online shopping. The largest share (32.59%) shop online once a month; another 26.62% even several times a month. A significant part of the respondents (22.89%) makes purchases online at least once a year, and 7.71% shop every week. A small group (18 people) stated that they shop more than once a week, while the same number of respondents declared only one purchase per year. Only 1% of the respondents do not use online shopping at all. The results therefore show that the research focused on the frequency of online shopping, not on the exact moment or age at which the respondents started shopping online.

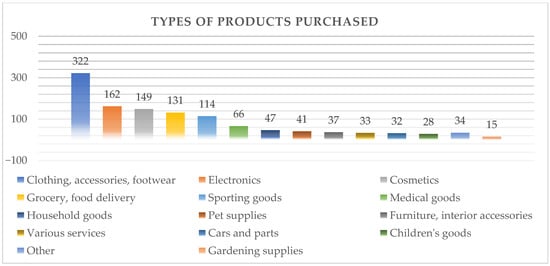

- Most frequently purchased products

Respondents were provided with options from which they were asked to select the types of products or services that they most frequently procure through online shopping. The question included a total of 13 categories of the most popular types of products purchased online, including the option to write in your own answer. For respondents who answered with their own product category, we combined their responses into an “Other” category. The figure below shows that the most popular product categories for online shopping by Generation Z are fashion products, i.e., clothing, accessories and footwear. The second most popular category of goods is electronics followed by cosmetics. Respondents largely use the internet for grocery shopping and food delivery. Sporting goods are also popular among Generation Z respondents. In general, it can be argued that Generation Z uses online shopping primarily to buy clothes, electronics, beauty products, food and sporting goods. The observed frequencies of each response are shown in the Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Types of products purchased. Source: authors’ research.

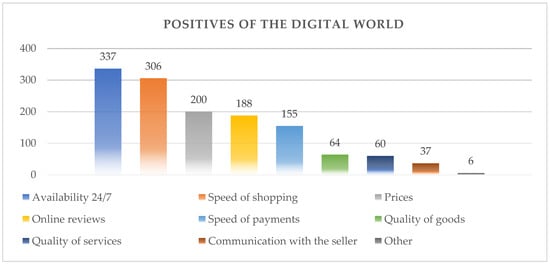

- Positives and negatives of the digital world

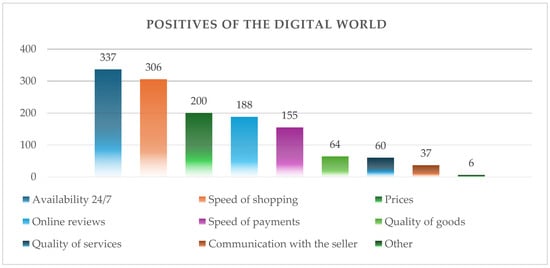

The survey questionnaire was used to find out the factors that respondents rate as positive or negative based on their own preferences. The following Figure 4 shows the most frequent responses that respondents identified as positive.

Figure 4.

Positives of the digital world. Source: authors’ research.

The biggest positive of the existence of the digital world for Generation Z is clearly the availability of online shopping 24 h a day. Generation Z also appreciates the convenience of online shopping in terms of its speed. The price factor is only the third highest positive.

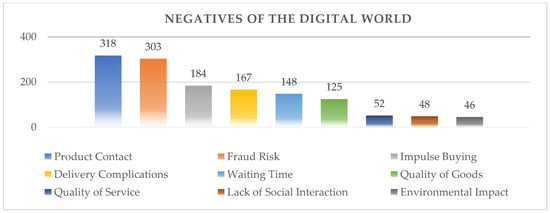

Figure 5 shows the identified negatives in this area.

Figure 5.

Negatives of the digital world.

The biggest negatives of online shopping are considered by consumers to be the lack of physical contact with the product and the risk of various scams that they are exposed to in the online environment. Generation Z can also be seen to be somewhat self-reflective in their purchasing behaviour, given that they ranked impulse buying as the third biggest negative of the digital world. Generation Z is prone to irrational demand, as evidenced by the number of responses for this option.

- The intensity of the impact of the digital world

Our next concern was for respondents to evaluate the intensity of the influence of the digital world on their shopping behaviour. As many as 56.72% of the respondents (229) rated the influence of the digital world as average, i.e., they do not reject its presence. 23.88% of the respondents (96) commented on the high intensity of this influence. 16.42% of the respondents expressed their answer with the option of low influence (66). Thus, the existence of influence on consumer buying behaviour among Generation Z cannot be dismissed even because only 2.99% (12) of the respondents expressed that they do not feel the influence of the digital world on their buying behaviour at all.

- Marketing communication

One of the other parts of the questionnaire survey was to find out the influence of reviews on purchasing decisions and different types of advertisements.

- The impact of reviews on purchasing decisions

Reviews are an important factor in online shopping. Users read them to gather information about products and manufacturers, most of which they have no previous experience with. Both the availability and popularity of reviews have increased substantially in recent years and therefore, in order to analyse the consumer behaviour of Generation Z, respondents were asked a question exploring the influence of reviews on their purchasing decisions. A total of 45.02% (181) of the respondents said that reviews have an average influence on them and 25.87% (104) said that reviews have a low influence on them. This finding implies that Generation Z largely searches for reviews, but they do not influence them to the extent where they change their purchase decision. A total of 14.93% (60) of Generation Z consumers said that reviews have a major influence on them, which is contrary to findings from expert sources, and 14.18% (57) of respondents said that reviews have no influence on them at all.

- Advertisement

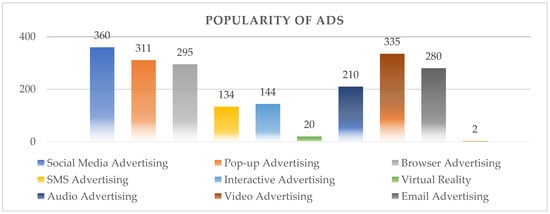

The popularity of each of the most well-known types of advertisements among consumers was surveyed along with their effectiveness in the context of their success in encouraging consumers to make a purchase. The popularity of advertisements among consumers was examined to determine the types of advertisements that Generation Z consumers encounter most frequently. The results of the findings are presented in the Figure 6 below.

Figure 6.

Popularity of ads. Source: authors’ research.

According to the results of the research, the most identified ad in terms of popularity is social media advertising, followed by video ads, then pop-up ads, browser ads, email ads and audio ads.

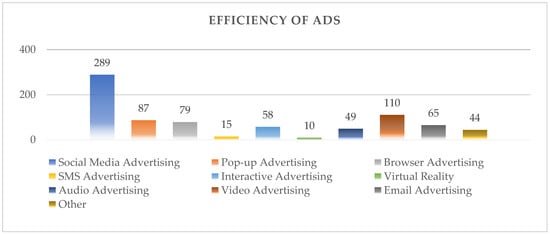

Another aspect of advertising studied was to determine the type of advertising in terms of effectiveness with the respondent.

The results (Figure 7) show that respondents attributed the highest effectiveness to social media ads, followed by video ads, pop-up ads, and in-browser ads.

Figure 7.

Efficiency from ads. Source: authors’ research.

- Social networks

Within social networking, respondents’ observations focused on their activity in this environment, time spent online, following people online, and buying from influencers.

- Time spent on social networks and online

For Generation Z, their time spent on social networks is a key data point when companies are deciding which types of ads to invest in depending on their target audience. This section of the questionnaire examined respondents’ daily activity on social media in hours per day. Nearly half of respondents, 49% (197), spend between 2 and 4 h on social media daily. The second most common response was 1 to 2 h at 25.37% of respondents (102). A total of 17.91% of respondents (72) spend more than 4 h on social networking sites daily and only 7.71% of respondents (31) spend less than an hour on social networking sites daily. From the results, it can be concluded that Generation Z spends quite a lot of time on social media, which creates an attractive opportunity for companies to target this customer group in the online space through digital marketing.

- Tracking people online

Another factor analysed in the digital world of consumers was whether respondents actively follow influencers and, if so, approximately how many of them there are. Within the questionnaire, respondents answered through the following options “I follow but less than 5”, “I follow 5 or more”, “I follow only 1 such profile” and “I am not an influencer follower”. A total of 37.06% of respondents (149) said that they do not follow influencers as part of their online activity, thus they have no influence on their purchasing decisions. The second largest proportion of respondents are those who follow less than 5 such influencers online, namely 147 respondents (36.57%). The third largest group follows 5 or more influencers, accounting for 18.16% of respondents (73), and 8.21% (33) follow only one influencer. From the findings, it is evident that consumers belonging to Generation Z can be expected to be influenced by influencers in their purchase decision making.

- Buying from influencers

The next question related to social media directed the findings to consumers regarding their shopping directly from selected influencers or brands on social media. Thus, the existence of business transactions between sellers and users in the social networking space was analysed. Respondents answered the options “Yes, I regularly buy from influencers”, “Sometimes” and “No, I do not buy”. The survey results show that 52.99% of respondents (214) do not purchase from brands or influencers on social media and 42.79% (172) sometimes use this option. The smallest proportion, 4.23%, had respondents who use this form regularly.

- Generation Z preferences

In terms of consumer preferences, we were interested in the environment that respondents prefer for purchasing. These included online retailer availability, payment methods and shopping priorities, as well as the challenges and benefits of online shopping.

- Preferred environment

At this point, we were interested in which environment Generation Z preferred for shopping. Respondents commented on the option of a brick-and-mortar store or an online store. A total of 36.67% of respondents (148) indicated brick-and-mortar store and a large proportion of respondents, 63.33% (255) preferred to shop in the online space.

- Online availability of retailers

The importance of availability of any retailer in the online space for Generation Z consumers was examined. Respondents may not only use the online space for direct shopping, but also for browsing the portfolio, contacting the retailer for queries, checking the returns policy, etc. A total of 47.51% of the respondents (191) consider the presence of a salesperson in the online space as very important. This is thus a significant assumption if the retailer’s goal is to attract Generation Z as well. The second most represented group was consumers who consider the presence of a salesperson in the online space to be less important—31.59% (127). Only 12.19% (49) completely ruled out the possibility that the online presence of a salesperson is an important factor for them in their purchasing decision, and 8.71% of respondents (35) stated that they did not know the answer. Ultimately, however, given the various proportions of possible responses, it is reasonable to conclude that in today’s world, dealer presence in the online space is considered important, at least for Generation Z consumers.

- Payment methods

Modern stores today offer their customers a variety of payment methods. The aim of this part of the survey was to identify the preferred payment methods of Generation Z. The options provided for response were cash, credit card, and E-wallet, and respondents were given the opportunity to enter their own preferred payment type. From the survey results, the clearly preferred payment method is payment card with a response rate of 62.44% (252 respondents), followed by cash (20.65%, 83 respondents) and E-wallet. E-wallet represents a virtual wallet. Its most well-known form is, for example, PayPal. This option was indicated by 15.92% (64). Thus, it can be concluded that this method is also represented in Generation Z. Only 1% (4) of respondents chose a payment method other than cash, credit card or e-wallet. The “Other” option resulted in payment types such as cryptocurrency, Google Pay, Apple Pay, Contactless phone payment, Venmo app transfer, etc.

- Priorities when shopping

To refine consumers’ preferences and assign importance to different aspects of online shopping, respondents were asked to indicate the most important factors influencing their satisfaction with the online shopping process. Respondents were asked to choose from a list of options that they considered most important in the process. Figure 8 shows the results of the survey.

Figure 8.

Online shopping priorities.

Consumers ranked media content on the retailer’s website, the e-shop’s advertising policy and communication with the retailer as least important. Surprisingly, product quality ranked only 6th out of 9 overall shopping priorities, which is contrary to the findings from the literature. Generation Z consumers consider the clarity of the store, i.e., the ease of navigating the retailer’s web interface, to be the most important. The second most important factor was price, which reached approximately the same level of importance as the other factors, i.e., speed of delivery, reviews and credibility of the e-shop. Thus, the conclusion from this survey is that in the sample analysed Generation Z consumers consider the clarity of e-shops, prices and the important role played by reviews of other consumers, speed of delivery and credibility of the e-shop as the most important factors for online shopping.

- Problems with online shopping

In the next question, we asked about the most common problems consumers encounter when shopping online. The findings are shown in the Figure 9 below.

Figure 9.

Online shopping problems. Source: authors’ research.

Based on the responses, it is evident that the most common complication for respondents is the late delivery of ordered goods. A significant proportion of respondents also experience delivery of incorrect goods or goods with parameters that do not match the requirements and unsatisfactory quality of the ordered goods. The findings also show that respondents also experience frequent damage to goods followed by problems with payment. This is followed by delivery of wrong goods, poor communication with the seller and the last ranked “Goods not delivered”. The most common problems of e-shops are factors related to the actual logistics solutions by the seller in the form of transportation of goods from the seller to the consumer, securing the goods against damage during transportation, sending the products with the required parameters and the actual quality of the products sold.

- Advantages of online shopping

The last question asked about the biggest benefits that respondents associate with online shopping. The findings regarding the benefits are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Benefits of online shopping.

The biggest benefits of online shopping for Generation Z, according to the survey conducted, are clearly convenience, time savings, available promotions and discounts. Another important advantage of online shopping for Generation Z was the wide range of products and the ease of gathering information about the desired product.

- Testing the stated hypotheses

The existence and measurement of the intensity of the relationship between the above categorical variables was carried out through the so-called Chi-square test to verify the existence of the relationship and Cramér’s V, to verify its intensity. To perform these tests and verify the hypotheses, it was necessary that the variables used meet the following assumptions:

H1.

Frequency of shopping and time spent on social networks.

The first pair of categorical variables tested was the daily time spent on social networks and the frequency of online shopping. Thus, the aim was to test whether consumers are more active on social media, directly have an increasing tendency to shop more frequently in the digital world. Hypotheses H0 and H1 for the variables have the following wording:

H0.

There is no statistically significant relationship between time spent on social media and frequency of online shopping.

H1.

There is a statistically significant relationship between time spent on social networks and frequency of online shopping.

The results (Table 3) of testing this hypothesis were derived from constructing a contingency table through which we found the frequencies for each response.

Table 3.

Contingency table of detected frequencies.

In the next step, we proceed to test Hypothesis 1.

(Table 4) According to the results of the Chi-Square test, the resulting values are at 0.219. This value exceeds the set significance level of α = 0.05 which means that we accept the null hypothesis H0 and reject H1 since the result of the test shows that there is no statistically significant relationship between the variables under study. Thus, we can conclude that for Generation Z consumers, the frequency of shopping does not increase in direct proportion to the time spent on social networking sites.

Table 4.

Result of the Chi-Square test of Hypothesis 1.

H2.

Gender and effectiveness of ads.

The second hypothesis concerns the testing of the relationship between the variables of gender and ad effectiveness. Ads that are considered effective are defined as ads that induced the respondent to make a purchase. We formulated the hypothesis as follows:

H0.

There is no statistically significant relationship between gender and effectiveness of ads.

H1.

There is a statistically significant relationship between gender and effectiveness of advertisements.

Table 5 shows the observed frequencies of the variables under study.

Table 5.

Contingency table of detected frequencies.

The Chi-Square result is shown in the following Table 6.

Table 6.

Result of the Chi-Square test of Hypothesis 2.

The results of the Chi-Square test show that the p-value of 0.913 is higher than the set significance level of 0.05; therefore, we accept the null hypothesis, while rejecting the alternative hypothesis. We conclude that there is no statistically significant relationship between these variables.

H3.

Gender and intensity of influence of the digital world.

In the questionnaire survey, respondents evaluated the impact of the existence of the digital world on their purchasing behaviour. The purpose of further analysis was to determine, based on the responses of a representative sample, whether there is a relationship between consumers’ gender and the intensity with which the digital world influences their purchasing behaviour. For this analysis, the following hypotheses were established:

H0.

There is no statistically significant relationship between gender and the intensity of influence of the digital world.

H1.

There is a statistically significant relationship between gender and the intensity of influence of the digital world.

The results of the analysis carried out are shown below (Table 7).

Table 7.

Contingency table of detected frequencies.

The Chi-Square result is shown in the following Table 8.

Table 8.

Result of Chi-Square Test of Hypothesis 3.

The results of the Chi-Square test show that the p-value of 0.451 is higher than the set significance level of 0.05; therefore, we accept the null hypothesis, while rejecting the alternative hypothesis. We conclude that there is no statistically significant relationship between these variables.

H4.

Intake level and type of platform used.

Having uncovered the relationship between regular income and the platforms used, this was complemented by a deeper analysis in terms of the level of income of the consumer individuals. The purpose of this analysis is to identify any possible dependence between the level of income of an individual and the type of platforms they use in the digital world. The hypothesis has been established as follows.

H0.

There is no statistically significant relationship between the level of income of an individual and the type of platforms used.

H1.

There is a statistically significant relationship between the amount of income of an individual and the type of platforms used.

According to Table 9 and Table 10, it can be stated that the p-value of the Chi-Square test at 0.047 is less than the set significance level of 0.05, indicating that there is a statistically significant relationship between the variables under study. Based on the H0 test conducted, we reject H0 and accept the alternative hypothesis H1. We proceed to measure the strength of the observed dependence.

Table 9.

Contingency table of detected frequencies.

Table 10.

Result of Chi-Square Test of Hypothesis 4.

According to the coefficient of Cramer’s V, that is in Table 11, whose level is 0.123, which is a lower value compared to the coefficient in the previous analysis. Thus, the intensity of the relationship between the level of consumer income and the type of platforms visited remains weak, although in this case it is slightly weaker than in the previous analysis.

Table 11.

Result measuring the intensity of addiction.

Thus, according to the analysis carried out, the generation of regular income has a slightly higher impact on the platforms visited than the level of income.

H5.

Working status and sustainability and vendor ethics.

The aim in this analysis is to find out whether Generation Z individuals generating a regular monthly income place a higher importance on buying sustainable products from ethically behaving sellers. To test these assumptions, the following hypotheses were established:

H0.

There is no statistically significant relationship between work status and the importance of sustainability and ethics to consumers.

H1.

There is a statistically significant relationship between working status and the importance of sustainability and ethics to consumers.

The categorical variables were tested by Chi-Square test. To run the test, we needed to create a contingency table, see below (Table 12).

Table 12.

Contingency table of detected frequencies.

We report the Chi-Square result in the table below (Table 13).

Table 13.

Result of Chi-Square Test of Hypothesis 5.

The results of the Chi-Square test show that there is a statistically significant relationship between the variables under study. Consumers who generate a regular monthly income have an increased tendency to purchase products and services with a sustainable label and prefer retailers with ethically correct behaviour and values. We reject H0 and accept H1.

When measuring the strength of the dependence, we find the following results (Table 14).

Table 14.

Result measuring the intensity of addiction.

In this case, the coefficient of Cramer’s V has a value of 0.195, which means that the strength of the relationship between the categorical variables is weak.

H6.

Time on social networks and gender.

The last dependency analysis conducted was an analysis of the categorical variables of daily time spent on social networking sites and the gender of the Generation Z consumer. If a dependency was shown to exist, it would mean that one of the genders of consumers would be more available to receive marketing communications from retailers than the opposite gender. To test the existence of dependence, the following hypotheses were established:

H0.

There is no statistically significant relationship between the daily time spent on social networking sites and the gender of the Generation Z consumer.

H1.

There is a statistically significant relationship between daily time spent on social networking sites and the gender of the Generation Z consumer.

The results of the analysis are as follows (Table 15).

Table 15.

Contingency table of detected frequencies.

The following table gives the results of the testing (Table 16).

Table 16.

Result of Chi-Square Test of Hypothesis 6.

Compared to the established significance level of α = 0.05, the coefficient of the Pearson Chi-square test reaches 0.000. Thus, there is undeniably a statistically significant relationship between the categorical variables. This result is followed by the Fisher Exact Test value, which is identical to the result of Cramer’s V. Thus, we reject H0 and accept H1. The next step is to measure the strength of the dependence (Table 17).

Table 17.

Result measuring the intensity of addiction.

Cramer’s V revealed a weak strength of association between categorical variables at 0.178. However, the dependence between them ultimately exists and one of the genders is an easier target for marketing communication by salespeople or receiving it daily for longer.

Multivariate Analysis—Logistic Regression

The purpose of the multivariate analysis was to determine which demographic and digital factors significantly influence the likelihood of frequent online shopping among Generation Z consumers. To achieve this, a binary logistic regression model was used, in which the dependent variable was dichotomized as follows: 0 = respondents who shop online less than once per month; 1 = respondents who shop online at least once per month.

Based on the preceding univariate and bivariate analyses, the following predictors were selected:

1. Gender (Male = 0, Female = 1)

2. Monthly income (≤€1000 = 0, >€1000 = 1)

3. Daily time spent on social networks (≤2 h = 0, >2 h = 1)

4. Working status (no regular income = 0, regular income = 1)

5. Perceived intensity of the digital world’s influence (Low/Average = 0, High = 1).

The model summary is shown in the following Table 18.

Table 18.

Model Summary.

- -2 Log Likelihood (-2LL)

This indicator measures the overall degree of misfit between the model and the observed data. A lower value indicates that the model fits the actual data more closely. Log Likelihood expresses the logarithm of the probability of observing the data under the given model—thus, the higher the likelihood (and the lower the -2LL), the better the model fits. It is also used for comparing multiple models—lower -2LL values indicate a better model fit. The indicator has a value 438.27, which means that the model achieves an acceptable level of fit—it is not perfect, but it performs better than the null model (without predictors).

- Cox & Snell R2

This coefficient is an analogue of the classical R2 from linear regression, adjusted for logistic regression.

It expresses the proportion of variability in the dependent variable (in this case, the frequency of online shopping) explained by the set of independent variables.

However, it has an upper limit of less than 1 because, in logistic regression, the computation is based on probabilities rather than variances. Cox & Snell R2 = 0.142. It means that the model explains approximately 14.2% of the variability in online shopping frequency.

- Nagelkerke R2

It is an adjusted version of the Cox & Snell R2 that rescales the result to allow values between 0 and 1. It is often referred to as a pseudo-coefficient of determination and serves as an alternative to R2 in linear regression. Nagelkerke R2 = 0.196 and it means that the model explains 19.6% of the variability in the probability that a respondent is a frequent online shopper. In social and behavioural sciences, this represents a solid explanatory level.

- Hosmer–Lemeshow Test (p)

It divides predicted probabilities into groups and compares them with the observed outcomes. It is This is a goodness-of-fit test for logistic regression. H0: The model fits the data well. H1: The model does not fit the data. If p > 0.05 → the model has a good fit (H0 is not rejected). In our case Hosmer–Lemeshow p = 0.311 > 0.05. The model fits the data well, with no significant deviations between predicted and observed values.

- Classification Accuracy

This statistic indicates the percentage of cases correctly classified by the model (i.e., whether it correctly identifies who belongs to the group of frequent and infrequent online shoppers). It is based on the confusion matrix (predicted vs. actual categories). In social science research, typical accuracy values range between 65 and 80%. In our case it has classification accuracy 73.1%, meaning that the model correctly classifies approximately three quarters of respondents, which is a very good result for behavioural data.

- Explanation of Regression Coefficients

This subsection provides a detailed explanation of the regression coefficients obtained from the binary logistic regression model. Each coefficient describes the direction, strength, and statistical significance of the relationship between the predictor variables and the likelihood of frequent online shopping among Generation Z consumers.

B (Coefficient): Indicates the direction and strength of the predictor’s influence on the dependent variable, expressed in log-odds. A positive value means that higher values of the predictor increase the likelihood of frequent online shopping, while a negative value decreases it.

S.E.: (Standard Error) Reflects the precision of the estimated coefficient. Smaller values imply higher precision and reliability of the estimated effect.

Wald: Represents the Wald Chi-square statistic, which tests the null hypothesis that the regression coefficient (B) is equal to zero. A larger Wald value suggests that the predictor contributes significantly to the model.

Sig. (p): The significance level (p-value) indicates whether the predictor variable has a statistically significant influence on the dependent variable. If p < 0.05, the effect is statistically significant, meaning the predictor has a meaningful impact on the likelihood of the outcome.

Exp(B) (Odds Ratio): Shows how the odds of the outcome change with a one-unit increase in the predictor while keeping all other predictors constant. An Exp(B) value greater than 1 indicates an increase in the likelihood of the event, while values below 1 suggest a decrease.

Constant: Represents the baseline log-odds of the dependent variable when all predictors are set to zero. It acts as a reference point for the model and has no direct substantive interpretation.

The logistic regression results revealed that time spent online was the strongest and most statistically significant predictor (p < 0.001, Exp(B) = 2.75). Respondents who spend more than two hours daily on social media are approximately 2.75 times more likely to shop online frequently. Perceived digital influence (p = 0.018, Exp(B) = 2.04) also significantly increases the likelihood of frequent online purchases. Higher-income respondents (p = 0.023, Exp(B) = 1.92) and female consumers (p = 0.024, Exp(B) = 1.62) show greater odds of frequent online shopping. In contrast, working status (p = 0.221) was not statistically significant, indicating that employment type does not substantially affect online shopping frequency.

4. Discussion

Based on the results obtained from the questionnaire survey, it appears that Generation Z is very active in the digital world and shows clear buying tendencies that are largely influenced by the online environment.

There are many factors influencing this generation. The dominant one is currently, according to (), the ease of integrating AI into daily life and perceived AI utility enhancing purchase intentions.

This view is also confirmed by (), with their finding that artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a powerful tool that is redefining the online shopping experience.

However, the online experience itself plays an important role. This is also the finding of () who obtained research results that indicate that online brand experience, brand image, brand trust, and brand loyalty play the most crucial roles, having a greater effect on Gen Z’s purchase intention, while brand awareness and knowledge also contribute. However, brand engagement and behavioural intention have weaker effects. These findings suggest that brands targeting Gen Z should prioritize building a strong, trustworthy, and engaging online presence while highlighting their sustainability efforts, and when Gen Z consumers have favourable digital interactions with a brand, perceive its image positively, trust it, and feel loyal to it, they are more likely to consider purchasing its sustainable offerings.

It is known that Generation Z is sensitive to environmental issues, which also affects their purchasing behaviour. This is also evidenced by the conclusion of the research by (). The results of their research showed that purchasing intention for eco-products is strongly influenced by the perceived quality of environmentally friendly products, consumer consciousness about eco-products, perceived value of green products, and consumer trust in ecological products.

This view is also supported by (), who concluded that pro-environmental beliefs affect Generation Z consumers’ attitudes and continuance of intention toward online fashion resale participation with strong effects for the group of self-oriented shoppers.

Focusing on our survey, we were able to gather detailed information about their purchasing behaviour, preferences and relationships to digital marketing communication.

The results of our findings show that there are advertisements that Generation Z hardly responds to at all nowadays. For these types of ads, Gen Z feedback is almost completely absent. The most popular form of advertising for this generation is social media advertising. It can therefore be concluded that if a business intends to target advertising exclusively to this generation, it should go down the social networking route.

The fact that social networks are very close to Generation Z is confirmed by the authors (). They argue that Generation Z has different activities on social media depending on whether they join it for daily routine alternatives or socialization. They also found that motivation and family income interacted and influenced Generation Z’s social media practices (e.g., social capital accumulation and exchange and self-expression). In terms of preference for specific social networking sites, according to (). The most popular platforms are YouTube, WhatsApp, TikTok, and Instagram.

Demographics and social status: there was a noticeable dominance of women among Generation Z respondents (60.45%), which may have implications for preferences in shopping categories such as fashion, cosmetics, and electronics, which are frequently found among women. The high proportion of students (61.44%) indicates that a majority of the respondents do not have a stable income, which influences their purchasing decisions. In this context, it is interesting to note that Generation Z is willing to shop even at higher prices if they are dealing with quality products, indicating their selective approach to online shopping.

The digital world and shopping: Generation Z shows a high intensity of online shopping. Almost a third of respondents shop once a month, while 26.62% shop more frequently, indicating the strong influence of the digital environment on their decision-making. The most frequently purchased products are fashion, electronics and cosmetics, which are categories that are commonly promoted through online channels, making it clear that this generation is very active in the online space and open to online shopping. (). In this regard, they add that the attributes of advertising, including fashion, socialization, entertainment, personalization and branding, significantly support the psychological needs and satisfaction of young people. In addition, satisfaction influences consumer behaviour, and in the same way, fashion and brand attributes directly influence consumer satisfaction. The study by (). shows that unlike Generation Y, which is slower to adopt e-commerce, Generation Z shows a strong preference for online shopping due to their comfort level with technology and their status as digital natives.

The positive aspects of the digital world for Generation Z are mainly in the availability of online shopping 24 h a day and the speed of the shopping process. Conversely, the downside is the lack of physical contact with the product and the risk of fraud. In this respect, it is evident that Generation Z is aware of the potential risks of online shopping, but at the same time appreciates its advantages such as convenience and flexibility.

The impact of reviews and advertising: reviews are an important factor in Generation Z’s decision-making, but they are not decisive for every respondent. More than half of respondents consider reviews to have a moderate influence on their decision-making, with only a small proportion of their purchasing decisions being entirely dependent on these reviews. This demonstrates the relative independence of this generation in making purchasing decisions, although they do value feedback from other consumers. Interesting in this context is the finding of the authors of (), who investigated the influence of online product reviews on purchase decision making. Their results showed that consumer attention to negative comments was significantly greater than attention to positive comments, especially among female consumers. The study further identified a significant correlation between consumers’ visual browsing behaviour and their purchase intention. It was also found that consumers were unable to identify fake comments. Specifically, the differential effects of consumers’ attention to negative comments appear to be moderated by gender, with consumers’ attention to negative comments being significantly greater than attention to positive comments. These findings suggest that practitioners need to pay particular attention to negative comments and address them promptly by tailoring product/service information to consumer characteristics, including gender.

Regarding advertising, social networks are proving to be the most effective tool for reaching this group. Adverts on social networks are both the most popular and the most effective, which confirms the current trend in digital marketing. This means that companies should invest heavily in ads on these platforms to maximize their reach among young consumers. However, the impact of ads can also have negative consequences, as declared by (). Indeed, the results of their investigation suggest that attitude towards advertising negatively affects the perceived intrusiveness of ads, whereas attitude towards advertising positively affects the credibility and value of ads. Thus, only tailored ad content leads to a positive attitude towards ads, creating an optimal experience on the platform and positive perceptions of ads in terms of trustworthiness and value.

Popular people, called influencers, are associated with social media activity and are followed by users based on likes, similar opinions and values. These individuals generate income from content creation, which is also associated with the creation of paid advertising. In this way, influencers can directly influence the purchasing decisions of their followers or followers’ followers. According to expert sources, influencer marketing is particularly popular among Generation Z. From the data collected so far, it can be concluded that influencers are popular among Generation Z, but most of these consumers do not use social networks to buy from them. Influencers are therefore an appropriate form of marketing communication with these consumers, but they do not form an effective sales tool between them and the retailer in the online space. This observation is supported by the author () who states that YouTubers, influencers or, in a broader context, content on social media platforms (such as Instagram, TikTok, as well as entertainment platforms such as Netflix) demonstrate how the new mediators of communication and forms of media content preferred by young people are more than ever linked to the sharing of values, norms and social expectations, similar to how family and school used to be. Similarly, the importance of influencers is confirmed by (), who offers insights from his study regarding influencers influencing Generation Z. His findings confirm that this generation is susceptible to being influenced by influencers on social media in a variety of contexts. Three factors play a key role in this regard: parasocial relationship, trust and the ability to identify with them.

In addition to the content that influencers offer on social media, the quality of the content is also very important. This is because, according to an influencer’s expertise, it is crucial for building authority and credibility in a particular field or business. Therefore, mega influencers’ recommendations on Instagram are more likely to be accepted by young audiences when they demonstrate deep expertise and understanding. Influencers have a significant influence on Generation Z’s buying behaviour, although only about 18% of respondents follow more than 5 influencers. However, most respondents do not follow them regularly. Interestingly, although influencers can influence purchasing decisions, the majority of Generation Z do not use social media to buy directly from influencers or brands. This phenomenon suggests that while influencers do shape purchasing decisions, social networks do not serve as the primary shopping environment for this generation.

The survey results show that Generation Z is very digitally oriented, with their purchasing behaviour largely influenced by the online environment. Based on the preferences and habits of Generation Z, it is evident that companies should focus on marketing strategies that include advertising on social media, using influencers and providing quality online reviews. Considering the high intensity of online shopping by this generation, their behaviour becomes a key factor for success in digital marketing.

Based on the above findings about the behaviour of Generation Z in the digital environment, the following managerial implications can be recommended for businesses:

- Adapting marketing strategy: Focus on personalised marketing campaigns that reflect values such as transparency and speed. Make sure that communications are tailored to the preferences of Generation Z, especially through video advertising on social networks.

- Optimising online presence: Create and maintain attractive and intuitive online platforms that offer a simple and fast purchasing process. This way, you will ensure that customers have a positive experience, which increases the likelihood of repeat purchases.