Abstract

Context: Digital entrepreneurship has attracted the attention of governments, investors, and researchers, who are directing their efforts and resources toward investigating its causes. Several studies have focused on the positive factors contributing to entrepreneurial intentions, with Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) being the most cited. This paper examines the relationship among TPB, emotions and social capital in the digital context. Objective: To evaluate the impact of social capital and anticipated emotions (positive and negative) on the digital entrepreneurial intentions of students from Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Methodology: The research proposed seven hypotheses, including two new ones, all of which are embedded in the digital context. Data were collected using a questionnaire administered to undergraduate students in Business Administration, Engineering, and Information Technology. A total of 1110 valid responses were obtained. The data were analysed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). Results: Considering the TPB factors, Attitude (AT) and Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) significantly impact Digital Entrepreneurial Intentions (DEI), while Subjective Norms (SN) show a statistically significant but weak effect (f2 < 0.02). Social Capital (SC) indirectly influences DEI by shaping attitudes. Anticipated Positive Emotions (APE) and Anticipated Negative Emotions (ANE) are statistically significant; however, their practical moderating effects are weak. Conclusions: Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) emerges as the strongest predictor of Digital Entrepreneurial Intention (DEI), while Subjective Norms (SN) and emotional factors (APE and ANE), though statistically significant, exhibit limited practical influence. Practical implications: Understanding how anticipated emotions interact with SC in shaping DEI can help educators and policymakers develop more effective strategies to support aspiring entrepreneurs. Originality: This study highlights the relationships among TPB factors, SC, APE, and ANE, underscoring the complex role of emotions in the digital entrepreneurial process. This research enriches the literature by incorporating emotional and social dimensions into the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), demonstrating that digitalisation reshapes, rather than displaces, the cognitive foundation of entrepreneurial action.

1. Introduction

Contemporary entrepreneurship is simultaneously tempting and challenging. Tempting because professionals of all ages today receive both objective and subjective stimuli to create new businesses, and challenging because today’s competitiveness requires confidence in one’s value proposition (), management capabilities, and the ability to adapt, identify and exploit opportunities that are often hidden (). Entrepreneurial activity is one of the most relevant forces sustaining the economies (; ). Entrepreneurship has been a key instrument in promoting a country’s competitive capacity and constraining competition between nations ().

With this in mind, public and private agents have promoted entrepreneurship, especially in the innovation and high-tech sectors (; ). Among the challenges involved in promoting entrepreneurship are the creation and fostering of ecosystems (; ; ; ), companies () and conditions conducive to the emergence of new entrepreneurs (; ; ; ; ).

Entrepreneurship often assumes the condition of a lifestyle or personal project, stimulating autonomy and reducing unemployment (; ). () consider the ability to identify and solve problems vital to entrepreneurial action and emphasise the belief in one’s capacity to do so creatively and effectively. Personality traits, skills, and self-management (), and social context () contribute significantly to entrepreneurial intentions.

() investigated the prediction of human behaviour to understand how specific psychological resources—attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control—can influence, or even determine, an individual’s prior (or planned) intention to act in a certain way to accomplish a goal. The author named this model the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB).

TPB has been widely used in research on Entrepreneurial Intent (EI) in emerging countries (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ), including Brazil (; ; ).

Researchers investigating the subject often employ Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). Despite this profusion of studies, we identified an opportunity to expand ’s () TPB by adding sub-factors that have not yet been jointly explored in the literature: (i) Social Capital (SC), (ii) Anticipated Positive Emotions (APE) and (iii) Anticipated Negative Emotions (ANE). Accordingly, this article investigates how social capital and anticipated emotions (negative and positive) interact to influence Digital Entrepreneurial Intentions (DEI). Its academic relevance becomes more explicit when considering that the Business Administration and IT undergraduate students in the study sample are potential entrepreneurs. This is particularly relevant because these students are often exposed to interdisciplinary knowledge, combining managerial skills with technological expertise, which is critical for identifying and seizing opportunities in the digital economy. By understanding their entrepreneurial intentions, institutional leaders and course coordinators can better adapt curricula to foster skills such as innovation, emotional resilience, and networking, thereby preparing students more effectively for the challenges of digital entrepreneurship (; ).

Although prior research has extensively applied the TPB to entrepreneurial contexts, few studies have explored how emotional and social dimensions jointly influence digital entrepreneurial intentions. This gap is especially pronounced in emerging economies like Brazil, where digital entrepreneurship is growing rapidly but remains under-researched. This study, therefore, addresses the following research question: How do social capital and anticipated emotions (positive and negative) interact to influence university students’ digital entrepreneurial intentions? By addressing this gap, the study extends the TPB model by incorporating emotional and social constructs in the context of digital entrepreneurship. Contributions state that integrating psychological and relational dimensions advances theories and offers practical insights for education, policy, and support programs for young digital entrepreneurs.

In addition to this introduction, the paper is organised into four further sections. Section 2 presents a literature review (based on articles identified by the RSL conducted) on (i) the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and Entrepreneurial Intention (EI) and (ii) PLS-SEM (analysing the studies that use this method). Section 3 explains the methodology. Section 4 presents the results, with discussion and data analysis. Finally, Section 5 outlines some conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour and Entrepreneurial Intention

The Theory of Planned Behaviour () posits that individuals make decisions in a reasoned manner, systematically using available information and considering the implications of their actions, and behave in a certain way. According to TPB, the factors responsible for behavioural variation relate to Attitude (AT), Subjective Norms (SN), and Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) (). () conclude that these factors can be mediated by experience, leading future entrepreneurs to weigh risks and understand their skills more realistically (). The intention-action gap occurs when the desire to start a business fails to translate into actual entrepreneurial behaviour ().

The EI may remain dormant but is stable over time (). Family (; ; ) and the university environment affects EI through subjective norms (). Entrepreneurs’ confidence is positively affected by the quality of financial and legal institutions ().

() and () highlight AT as the key determinant for EI. In the context of TBP, attitude refers to an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of entrepreneurship based on expected outcomes (). Individuals who perceive entrepreneurship as a path to personal fulfilment, financial success, or autonomy are more likely to develop a favourable attitude toward EI (; ; ; ). Entrepreneurial education can influence these perceptions by shaping beliefs about the feasibility and desirability of starting a business (). Therefore, fostering a positive attitude toward entrepreneurship requires exposure to entrepreneurial knowledge and reinforcement of its potential benefits and rewards.

Subjective norms (SN) refer to the perceived social pressure to engage (or not) in entrepreneurial activities, shaped by the expectations and opinions of family, friends, mentors, and broader societal influences (). These norms often serve as a source of motivation, particularly in collectivist cultures, where social acceptance plays a critical role in shaping behaviour. However, empirical findings on the impact of subjective norms remain divergent. While some studies emphasise the importance of social support and endorsement in strengthening EI, () found that subjective norms do not significantly influence EI. Similarly, () in a study with Indian university students reported limited evidence of their effect. These divergent findings suggest that the influence of subjective norms on EI may vary depending on cultural, demographic, and contextual factors.

Perceived behavioural control (PBC), the third factor in the TPB, refers to an individual’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing a specific behaviour, influenced by both internal factors (such as skills, knowledge, and confidence) and external conditions (such as available resources and potential obstacles) (). A high level of perceived behavioural control increases the likelihood that an intention will translate into an action, as individuals feel more capable of overcoming challenges. () associate PBC with risk propensity and stress tolerance, suggesting that individuals who perceive themselves as resilient and capable of managing uncertainty are more likely to develop EI. This concept is closely related to self-efficacy, defined by () as an individual’s belief in their ability to organise and execute actions required to achieve specific goals. Studies indicate that entrepreneurial self-efficacy is crucial in shaping entrepreneurial behaviour by reinforcing individuals’ confidence in starting and sustaining a business (; ). Therefore, fostering PBC through education, mentorship, and exposure to entrepreneurial experiences can enhance an individual’s likelihood of engaging in entrepreneurship.

2.2. Social Capital

Social capital (SC) is a multidimensional construct that positively impacts entrepreneurial capacity by facilitating access to resources, information, and social support (). It encompasses elements such as generalised trust, formal organisational associations, and civic engagement (), which contribute to the development of EI. Family influence plays a critical role in shaping EI through positive role models, emotional support, and resource sharing (; ; ; ). Educational environments, particularly universities, also foster social capital by expanding networks and promoting skills like risk-taking, stress management, and resilience (; ).

Social networks enhance social capital by providing emotional reinforcement, increasing confidence, and nurturing an entrepreneurial mindset (). These networks offer opportunities for knowledge exchange, mentorship, and partnerships that are crucial to entrepreneurial success, particularly in the early stages of venture creation. By connecting individuals to broader communities, social networks amplify access to diverse resources, which can be instrumental in shaping entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions.

For underprivileged groups, social capital can bridge institutional gaps, enabling entrepreneurial initiatives even with limited financial resources (; ). Additionally, technological competencies and access to information networks can strengthen an entrepreneur’s confidence and self-efficacy (; ), reinforcing the perception that success depends more on internal abilities than external conditions (). Despite the decisive role of social capital, a supportive institutional environment remains essential in fostering EI ().

While traditional studies () confirm a direct relationship between social capital and entrepreneurial intention, digital entrepreneurship introduces distinct contextual dynamics. Online ventures often rely more on technological self-efficacy, virtual collaboration, and platform-based interactions than on conventional face-to-face networks. These structural differences may weaken the direct impact of social capital, rendering it an indirect driver, mediated by AT and PBC.

2.3. Emotions

Emotions—APE and ANE—play a critical role in shaping EI. () argue that fear of failure is one of the most potent psychological barriers to the realisation of entrepreneurial intentions, as it triggers feelings of frustration, self-doubt, and perceived incompetence. These negative emotions can undermine an individual’s self-efficacy—the belief in their ability to succeed—which is essential for entrepreneurial behaviour. When self-efficacy diminishes, individuals may perceive obstacles as insurmountable, leading to lower motivation to pursue entrepreneurial activities. Furthermore, fear of failure can distort how entrepreneurs assess risk, leading to overly cautious decision-making and a reduced willingness to act.

In contrast, positive emotions, such as enthusiasm and optimism, have been found to strengthen self-efficacy and enhance the likelihood of entrepreneurial engagement (; ; ). Balancing emotional responses with cognitive processes is crucial for fostering sustainable EI. While positive emotions can fuel creativity and motivation, they must be tempered by rational thinking to ensure sound decision-making (; ).

Educational programmes aimed at developing resilience and emotional regulation play a pivotal role in helping potential entrepreneurs manage emotional fluctuations (; ). Resilience, in particular, is essential for overcoming setbacks and navigating the uncertainties inherent in entrepreneurial ventures (; ). Moreover, students with high levels of proactivity and emotional intelligence tend to exhibit stronger entrepreneurial intentions, as they are better equipped to handle challenges and capitalise on opportunities ().

These emotional and psychological factors significantly influence an individual’s capacity and motivation to pursue entrepreneurial ventures.

3. Methodology

3.1. Bibliographic Portfolio

Academic papers were extracted from the Scopus and Web of Science databases in three stages: the first in December 2021, the second in February 2022, and the third in January 2025. The process is detailed in the following subsections.

3.1.1. Stage 1

Stage 1 focused on identifying papers that addressed “digital business,” “digital mindset,” “social capital”, and “theory of planned behaviour.” Table 1 presents the search terms and strategies used during the first stage of document extraction.

Table 1.

Terms and search strategies used for paper extraction in the Scopus and Web of Science databases in Stage 1.

3.1.2. Stage 2

Stage 2 focused on identifying papers addressing “emotions” and “entrepreneurial intention.” Table 2 presents the search terms and strategies used in the second stage of document extraction.

Table 2.

Terms and search strategies used for paper extraction in the Scopus and Web of Science databases in Stage 2.

3.1.3. Stage 3

Stage 3 focused on updating articles related to the topic published after February 2022. At this stage, a query was applied that combined all previously used search terms. Table 3 presents the search terms and strategies employed in the third stage of document extraction. This stage was conducted separately from Stage 1 to ensure search accuracy and to double-check the completeness of the results.

Table 3.

Terms and search strategies used for article extraction in the Scopus and Web of Science databases in Stage 3.

3.1.4. Final Portfolio

The documents extracted from Scopus and Web of Science were imported into MS Excel 365 for portfolio refinement. After the initial extraction, the refinement process involved removing (i) duplicates, (ii) papers with missing information (year, title or author), and (iii) studies not aligned with the research scope. Table 4 summarises the results of each stage.

Table 4.

Results of document extraction in Stages 1, 2 and 3.

In the end, the final portfolio comprised 1607 papers, which served as the basis for the literature review and the formulation of hypotheses presented in the next section.

3.2. Hypotheses

3.2.1. Existing Hypotheses

Table 5 summarises the hypotheses of the selected papers and their respective authors. All of these were utilised in the digital context.

Table 5.

Hypotheses developed by previous studies.

3.2.2. New Hypotheses

This section presents the two new hypotheses formulated and explored in the present work. These hypotheses, summarised in Table 6, explore the moderating effects of Anticipated Negative Emotions (ANE) and Anticipated Positive Emotions (APE) on Social Capital (SC) and Digital Entrepreneurial Intentions (DEI).

Table 6.

New hypotheses proposed by the study (anticipated positive and negative emotions).

Emotions and desires are closely related and exert a substantial influence on entrepreneurial intention (; ). Social networks can positively impact affectivity and entrepreneurial mindset (). Although positive emotions stimulate entrepreneurial intention, they must be balanced with cognition to ensure sound judgment (). () cite resilience as an important characteristic. Business education and social capital promote entrepreneurial behaviour (), requiring development through psychological mechanisms, including emotion and cognition ().

The following subsection outlines the model developed to achieve the research objectives.

3.3. Model of Digital Entrepreneurial Intentions, Social Capital and Emotions

Our proposed model comprises seven constructs. Table 7 summarises each construct’s code, description, and classification (mediator or moderator) to facilitate the understanding of the concepts discussed in the following sections.

Table 7.

Code and description of the model constructs.

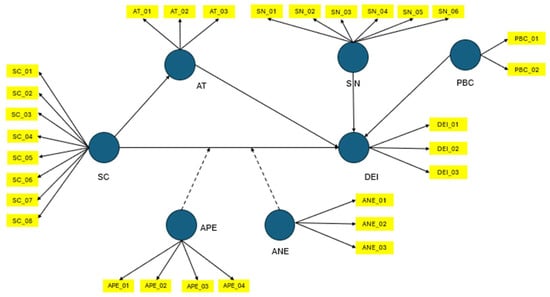

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model developed from the hypotheses discussed and those proposed following the portfolio analysis. The codes consist of four letters identifying the construct, followed by a sequential indicator number.

Figure 1.

Model of entrepreneurial intention (Elaborated by the authors). PS: The constructs added to the TPB were SC, APE and ANE.

Table 8 presents the relationship between the construct indicators and the authors who developed the questions. The TPB constructs (AT, PBC, SN, and DEI) are presented first, followed by the constructs added to the researchers’ proposed model (SC, APE, and ANE).

Table 8.

Information about model constructs and items.

The following subsection presents the criteria for sample selection and data collection techniques.

3.4. Ethics Committee

The Research Ethics Committee in Human and Social Sciences of UNICAMP (CEP-CHS), CAAE no. 58711822.6.0000.8142, approved the research. A 5-point Likert-scale questionnaire comprising 29 questions was administered (the questionnaire can be shared upon request).

3.5. Sample Selection and Data Collection

Data were collected through a questionnaire distributed to undergraduate students in Business Administration, Engineering and Information Technology, all aged 18 years or older, from public institutions in São Paulo.

This choice is justified by São Paulo’s status as Brazil’s most economically developed state, with a higher propensity to adopt technology, and by the fact that most of the researchers involved in this study are based there. The selected programmes also have a strong entrepreneurial orientation. The minimum sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 software.

The sample composition presents a potential limitation, as only 10.63% of respondents were enrolled in Information Technology programmes, a central area of digital entrepreneurship. This imbalance may have influenced the magnitude of certain relationships, particularly those associated with technology-based entrepreneurial behaviour.

Although the sample is composed of a group (IT) that may present some bias, the use of the SmartPLS FIMIX module () with two partitions indicated the existence of “two” groups with an incidence of 97.9% in segment 1 and 2.1% in segment 2, indicating that segment 2 is negligible; therefore, it can be considered that the data comes from a single sample.

3.6. Data Analysis

Data analysis used the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) approach. The quality of the model was assessed in terms of content, convergent, and discriminant validity. While convergent validity assesses the extent to which indicators measure the intended construct, discriminant validity assesses the extent to which indicators are distinct and representative ().

PLS-SEM is widely used to explain correlations among multiple variables () and is suitable for testing theoretical frameworks (). Microsoft Excel was used for data tabulation, and SmartPLS 4 was used to run the PLS-SEM algorithm—the measurement model evaluation aimed to assess the overall quality and reliability of the set of indicators.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Description

When using the G*Power software and the conditions suggested by (), with seven predictors, a 5% significance level, a statistical power of 80%, and a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), the calculation suggested a sample of 103 observations. The questionnaire was applied in both online and in-person formats. In the end, we obtained 1110 responses.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Of the 1110 respondents, 58.1% are men and 41.89% are women. As for courses, 57.30% were majoring in Engineering, 32.87% in Business Administration, and 10.63% in Information Technology (Computer Science, Information Systems, Software Engineering, etc.) (Table 9).

Table 9.

Sample description.

The following sections present calculations regarding the structural model’s (i) validity and reliability and (ii) evaluation.

4.3. Measuring Model

As previously mentioned, model validity and reliability are verified through (i) convergent validity and (ii) discriminant validity. After analysing the SmartPLS 4 results, we adjusted the model by removing six of the 29 indicators—SC_01, SC_02, SC_03, APE_01, APE_04, and DEI_02—leaving 23 indicators.

To ensure methodological transparency, the six excluded indicators (SC_01, SC_02, SC_03, APE_01, APE_04, and DEI_02) and their respective factor loadings are detailed in Appendix A (Table A1). All present external loadings were below 0.70, and cross-discrimination was low. Although the AVE of the Subjective Norms (SN) construct remained at 0.398, it was decided to maintain it due to its theoretical relevance in the Theory of Planned Behaviour (). The composite consistency above 0.70 indicates adequate reliability and supports its inclusion in the final model.

The six indicators were removed due to low outer loadings (<0.70) and low cross-loading discrimination, in accordance with (). This adjustment improved both convergent validity (AVE) and internal consistency reliability across the remaining constructs.

Table 10 presents the Fornell-Larcker criterion, Cronbach’s alpha, classical composite reliability (rho_c) and average variance extracted (AVE) values calculated using SmartPLS 4. The square roots of the AVE values (shown diagonally in Table 10) should be greater than the correlations among the corresponding constructs.

Table 10.

Fornell-Larcker criterion, Cronbach’s alpha, Composite Reliability and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values.

While Cronbach’s alphas for SN, PCB, APE, and DEI are below 0.7, all constructs’ classical composite reliabilities (rho_c) are equal to or exceed 0.70 (). Furthermore, except for SN, all AVE values exceed 0.5. Therefore, the model can be considered adjusted.

Although the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for Subjective Norms (SN) is slightly below the 0.50 threshold, the construct was retained due to its theoretical relevance within the TPB framework and its acceptable composite reliability (ρc = 0.797).

This decision aligns with (), who argue that marginally low AVE values can be tolerated when reliability and theoretical consistency are satisfactory. Having completed the validation stage, the following section presents the structural model analysis.

4.4. Structural Model

4.4.1. Model Analysis

Table 11 presents Cohen’s (f2), Pearson’s (r2) and Stone-Geisser’s (Q2) coefficients, calculated for the dependent variables (AT and DEI) based on the independent variable (SC). These three coefficients indicate the model’s explanatory power.

Table 11.

Structural model values.

The effect size (f2), presented in Table 11, as proposed by (), classifies values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 as (i) low, (ii) medium and (iii) moderate, respectively.

Pearson’s coefficient of determination (r2) measures the correlation between two variables, with values of 0.02, 0.13, and 0.26 listed as high, medium, and low in social and behavioural sciences ().

The predictive validity of the model is confirmed when Q2 values are greater than zero (). This condition is met in the present analysis, as shown in the table above, with AT = 0.052 and DEI = 0.675.

4.4.2. Resulting Model

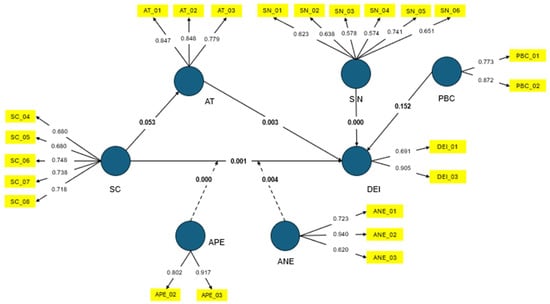

Figure 2 illustrates the final structural model with the corresponding path coefficients. The R2 analysis indicates that the DEI construct accounts for 69.3% of its variance, with Attitude (AT), Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC), Subjective Norms (SN), and Social Capital (SC) accounting for 69.3% of the variance.

Figure 2.

Adjusted final model.

Among these, PBC shows the most potent effect on DEI, accounting for 15.2% of the explained variance, thus representing the model’s most influential construct. Additionally, the constructs Anticipated Negative Emotions (ANE) and Anticipated Positive Emotions (APE) act as moderators in the relationship between Social Capital (SC) and Digital Entrepreneurial Intention (DEI).

The following section presents the results of the hypothesis test.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

Table 12 presents the result of hypothesis testing. The analysis was performed using SmartPLS 4 with the bootstrapping procedure (10,000 subsamples; 5% significance level) to calculate the t-statistics and p-values.

Table 12.

Results of the structural model hypothesis testing.

As shown in Table 12, all hypotheses—except H2 (SC → DEI)—were supported at the 5% significance level. The paths SC → AT (H1), AT → DEI (H3), SN → DEI (H4), and PBC → DEI (H5) presented significant path coefficients (p < 0.05), reinforcing the robustness of the TPB constructs.

The moderating effects of anticipated emotions (H6 and H7) were also statistically significant (p = 0.032 and p = 0.045, respectively), although their practical relevance was weak (f2 < 0.02).

In the following section, we discuss these results.

4.6. Discussion of Results

4.6.1. Social Capital and Attitudes (H1)

The positive effect of social capital on attitudes confirms that academic environments help students internalise pro-entrepreneurial behaviours through networking and collaboration. However, consistent with (), this effect remains indirect with respect to entrepreneurial intention.

4.6.2. Subjective Norms (H4)

Subjective Norms (H4) demonstrated statistical significance (t = 2.354; p = 0.019), although the effect size was weak (f2 < 0.02). This suggests that while students recognise social expectations regarding entrepreneurship, these influences play a secondary role compared with personal attitudes and perceived behavioural control.

4.6.3. Perceived Behavioural Control (H5)

PBC exhibits the strongest path coefficient (β = 0.152), confirming it as the primary driver of digital entrepreneurial intentions. This finding reinforces the role of self-efficacy and resource perception as critical enablers of entrepreneurial behaviour.

4.6.4. Emotional (H6, H7)

Both anticipated positive and negative emotions (H6 and H7) were statistically significant (p = 0.032 and p = 0.045, respectively). However, their weak effect sizes (f2 < 0.02) indicate limited practical relevance. These findings suggest that emotional anticipation exerts a slight influence on digital entrepreneurial intentions, whereas rational-cognitive factors—such as PBC and attitude—remain dominant.

4.6.5. Synthesis

Together, these findings extend the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) by demonstrating that digital entrepreneurship depends primarily on internal psychological control (PBC and AT), while social or emotional factors remain peripheral but non-negligible.

The results demonstrate that Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) prevails over Subjective Norms (SN) in the context of digital entrepreneurship. This predominance can be interpreted from the perspective of technological self-efficacy (; ), since the digital environment favours autonomy and reduces dependence on traditional social approval. Thus, individuals with greater technological proficiency tend to act more independently of normative pressures. Similarly, the non-significant effect of direct Social Capital (SC) on Digital Entrepreneurial Intention (DII) may reflect the transformation of trust networks: in digital ecosystems, informational capital (access to knowledge, data, and skills) surpasses relational capital based on personal ties. This perspective reinforces that digital trust and interactions mediated by virtual platforms reconfigure the traditional dynamics of social capital in entrepreneurship.

5. Conclusions

The study confirms that Attitude (AT) and Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC) are the main predictors of Digital Entrepreneurial Intention (DEI), with PBC showing the most substantial contribution (β = 0.152). Subjective Norms (SN) and Anticipated Emotions (positive and negative) were statistically significant but of weak practical importance (f2 < 0.02), indicating that social and emotional dimensions play a secondary, albeit measurable, role in shaping digital entrepreneurial behaviour.

These findings highlight that fostering self-efficacy, digital skills, and proactive attitudes may be more effective than focusing solely on emotional or social influences when designing entrepreneurship education programmes.

Emotional states are context-dependent and can be shaped by educational and environmental stimuli that enhance resilience and self-efficacy. The results indicate that positive and negative emotions (H6: ANE × SC → DEI; H7: APE × SC → DEI, supported) do not moderate the relationship between SC and DEI, but they do indirectly affect attitudes and self-efficacy.

The proposed model is limited to Brazil. Replicating this model in other cultural contexts may help us understand the moderating effect of emotions in DEI. Some findings suggest that interpretations vary in grey areas of knowledge, which may provide an opportunity to tackle the same problem in alternative contexts. As in this study, validating hypotheses with low path coefficients may provide others with new opportunities to understand this topic and test new hypotheses in new environments.

Although the sample imbalance is acknowledged—only 10.63% of IT students—future research could advance by conducting multi-group analyses or segmentations (e.g., IT vs. other areas) to assess whether academic background moderates the relationships predicted by the TCP. This approach could clarify whether the underrepresentation of IT students influences the strength of pathways associated with digital self-efficacy and technology-mediated entrepreneurial intentions.

While there is evidence supporting the hypothesis, the practical impact of the relationship may be limited, opening a range of new possibilities to challenge the existing TPB.

Furthermore, anticipated emotions tend to fluctuate significantly over time. Future research should consider using panel data to track these changes over extended periods. Data collection occurred post-pandemic, soon after in-person environments reopened. Focusing on fields with high digital entrepreneurial activity and São Paulo’s institutions enhanced feasibility but limited generalizability.

This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The sample imbalance, particularly the underrepresentation of IT students, limits the generalizability of the results. Future studies should replicate the model across diverse academic contexts and examine how disciplinary background moderates digital entrepreneurial intentions. Moreover, further investigations could employ longitudinal data to assess the stability of these relationships over time.

This study expands the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) by demonstrating that, in the context of digital entrepreneurship, emotional and social constructs—although statistically significant—play a peripheral role. This finding reinforces the dominance of cognitive components (Perceived Behavioural Control and Attitude) as the main drivers of entrepreneurial intention in technology-mediated environments. Thus, the research contributes to the literature by integrating emotional and social dimensions into the TPB, revealing that digitalisation redefines, rather than replaces, the cognitive core of entrepreneurial action.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.T.D. and C.M.; Formal analysis, A.L.T.D. and D.d.S.; Investigation, A.L.T.D. and C.M.; Methodology, A.L.T.D., C.M., E.I.J. and D.d.S.; Software, A.L.T.D., E.I.J. and D.d.S.; Supervision, E.I.J.; Validation, D.d.S.; Writing—review & editing, C.M. and E.I.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by The Research Ethics Committee in Human and Social Sciences of UNICAMP (CEP-CHS), CAAE (protocol code no. 58711822.6.0000.8142 and date 12 August 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The research data were collected through a specific form, created in Google Forms. The data are kept in Google Drive in an account managed by UNICAMP, with access restricted to Mr. André Luiz Tavares Damasceno (1st author) and Mr. Cristiano Morini (2nd author). In the informed consent form, participants were informed that the data were collected for specific use in this research. The users’ consent data were collected in written form, and their reuse in other similar research is not permitted. However, the authors are available to guarantee the veracity of the data used in the study in question.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Excluded items and their respective factor loadings.

Table A1.

Excluded items and their respective factor loadings.

| Construct | Item’s Code | Brief Description of the Item | Original Factor Loading | Exclusion Criteria | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Capital (SC) | SC_01 | “I know people who can help me start a digital business” | 0.58 | Loading < 0.70 | Adapted of () |

| Social Capital (SC) | SC_02 | “My online social network provides useful resources for digital entrepreneurship” | 0.61 | Loading < 0.70 | () |

| Social Capital (SC) | SC_03 | “I can easily obtain entrepreneurial information from my contacts” | 0.64 | Loading < 0.70 | () |

| Anticipated Positive Emotions (APE) | APE_01 | “I think I would feel proud if I started a digital business” | 0.67 | Loading < 0.70 | () |

| Anticipated Positive Emotions (APE) | APE_04 | “I will feel personal fulfilment by having my own digital business” | 0.66 | Loading < 0.70 | () |

| Digital Entrepreneurial Intention (DEI) | DEI_02 | “I am determined to create a digital business in the near future” | 0.62 | Loading < 0.70 | () |

References

- Ahmed, T., Klobas, J. E., & Ramayah, T. (2021). Personality traits, demographic factors and entrepreneurial intentions: Improved understanding from a moderated mediation study. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 11(4), 20170062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organisational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioural control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections (Vol. 26, pp. 1113–1127). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwale, Y. O., Ababtain, A. K., & Alaraifi, A. A. (2019). Structural equation model analysis of factors influencing entrepreneurial interest among university students in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 22(4), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Amini Sedeh, A., Abootorabi, H., & Zhang, J. (2021). National social capital was perceived to influence entrepreneurial ability and entrepreneurial intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 27(2), 334–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M. Y., Saleem, I., & Dwivedi, A. K. (2020). Understanding entrepreneurial intention among Indian youth aspiring for self-employment. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning, 13(3), 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, M. M., & Zeleke, S. A. (2018). Modelling the impact of entrepreneurial attitude on self-employment intention among engineering students in Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughn, C. C., Cao, J. S., Le, L. T. M., Lim, V. A., & Neupert, K. E. (2006). Normative, social and cognitive predictors of entrepreneurial interest in China, Vietnam and the Philippines. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatyreva, K., & Shirokova, G. (2017). From entrepreneurial aspirations to founding a business: The case of Russian students. Foresight and STI Governance, 11(3), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(4), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W. J., Gu, J. B., & Wu, J. L. (2021). How entrepreneurship education and social capital promote nascent entrepreneurial behaviours: The mediating roles of entrepreneurial passion and self-efficacy. Sustainability, 13(20), 11158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A., Ghezzi, A., & Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2021). Small-medium enterprises and innovative startups in entrepreneurial ecosystems: Exploring an under-remarked relation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(4), 1843–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. S., Yuan, C. H., Yin, B., & Wu, X. Z. (2021). Positive emotions and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of entrepreneurial cognition. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 760328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- da Cruz, E. F. Z., & Alvaro, A. (2013, October 23–26). Introduction of entrepreneurship and innovation subjects in a computer science course in Brazil. 2013 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Oklahoma City, OK, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doanh, D. C. (2021). The role of contextual factors in predicting entrepreneurial intention among Vietnamese students. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 9(1), 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. (2018). Entrepreneurial resilience: A biographical analysis of successful entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(2), 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T., Shirokova, G., & Tsukanova, T. (2016). The impact of family support on young entrepreneurs’ start-up activities. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(4), 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I. A., & Saad, S. K. (2021). Entrepreneurial resilience and business continuity in the tourism and hospitality industry: The role of adaptive performance and institutional orientation. Tourism Review, 77(5), 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T., Schwab, A., & Geng, X. S. (2021). Habitual entrepreneurship in digital platform ecosystems: A time-contingent model of learning from prior software project experiences. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(5), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gubik, A. S., & Farkas, S. (2016). Student entrepreneurship in Hungary: Selected results based on GUESSS survey. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 4(4), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoud, M. Y., Onjewu, A. K. E., Nowinski, W., & Alammari, K. (2022). Assessing the role of entrepreneurship education in regulating emotions and fostering implementation intention: Evidence from Nigerian universities. Studies in Higher Education, 47(2), 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjimanolis, A. (2016). Perceptions of the institutional environment and entrepreneurial intentions in a small peripheral country. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 28(1), 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equations modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2024). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, A., Contreras, F., Espinosa, J. C., & Barbosa, D. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions of Colombian business students: Planned behaviour, leadership skills and social capital. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 23(6), 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T. H., & Le, Q. H. (2021). Factors affecting youth entrepreneurial intention and suggestions for policymaking: The case of Vinh Long Province. Recent developments in vietnamese business and finance (pp. 723–743). World Scientific Publishing Co. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoong, C. W., Qureshi, Z. H., Sajilan, S., & Al Halbusi, H. (2019, December 14–15). A study on the factors influencing social entrepreneurial intention among undergraduates. 2019 13th International Conference on Mathematics, Actuarial Science, Computer Science and Statistics (MACS), Karachi, Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G. J. (2021). Social capital and financial capital acquisition: Creating gaming ventures in Shanghai’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. Chinese Journal of Communication, 14(1), 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudek, I., Tominc, P., & Sirec, K. (2021). The impact of social and cultural norms, government programs and digitalization as entrepreneurial environment factors on job and career satisfaction of freelancers. Sustainability, 13(2), 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P. P., Jambrino-Maldonado, C., Velasco, A. P., & Kokash, H. (2016). Impact of entrepreneurship programmes on university students. Education and Training, 58(2), 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izard, C. E., & Izard, C. E. (1977). Differential emotions theory. In Human emotions (pp. 43–66). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Joensuu-Salo, S., Varamäki, E., & Viljamaa, A. (2015). Beyond intentions—What makes a student start a firm? Education and Training, 57(8–9), 853–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M., Joshi, G., & Pathak, S. (2020). Awareness, entrepreneurial event theory and theory of planned behaviour as antecedents of student entrepreneurial intentions: An Indian perspective. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 25(2), 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, A., Molina, V., & Liargovas, P. (2020, September 17–18). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial beliefs and conceptualisations. 15th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, ECIE 2020, Roma, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminsky, O. Y., Yereshko, Y. O., Kyrychenko, S. O., & Tulchinskiy, R. V. (2021). Training in digital entrepreneurship as a basis for building a nation’s intellectual capital. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 81(1), 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanonuhwa, M., Rungani, E. C., & Chimucheka, T. (2018). The association between emotional intelligence and entrepreneurship as a career choice: A study on university students in South Africa. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowang, T. O., Apandi, S. Z. B. A., Hee, O. C., Fei, G. C., Saadon, M. S. I., & Othman, M. R. (2021). Undergraduates’ entrepreneurial intention: Holistic determinants matter. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 10(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoudas, M. Z., Yoon, S. Y., Boehm, R., & Asbell, S. (2020, June 22–26). Impact of an I-Corps site program on engineering students at a large southwestern university: Year 3. 2020 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference, ASEE 2020, Online. [Google Scholar]

- Lasso, S. V., Mainardes, E. W., & Motoki, F. Y. S. (2018). Types of technological entrepreneurs: A study in a large emerging economy. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 9(2), 378–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. G., Cortes, A. F., & Joo, M. (2021). Entrepreneurship education and founding passion: The moderating role of entrepreneurial family background. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 743672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J., & Welsch, H. (2005). Roles of social capital in venture creation: Key dimensions and research implications. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(4), 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. L., & Wang, Y. J. (2021). Innovation and entrepreneurship practice education mode of animation digital media major based on intelligent information collection. Mobile Information Systems, 2021, 3787018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londono, J. C., Wilson, B., & Osorio-Tinoco, F. (2021). Understanding the entrepreneurial intentions of youth: A PLS multi-group and FIMIX analysis using the model of goal-directed behaviour. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(3), 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.-F., Huang, J., & Gao, S. (2022). Relationship between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intentions in college students: Mediation effects of social capital and human capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 861447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, A., & Lee, C. (2021). The influence of entrepreneurial desires and self-efficacy on the entrepreneurial intentions of New Zealand tourism and hospitality students. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Education, 35(1), 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T. M. A. T., Al Mamun, A., Bin Ahmad, G., & Ibrahim, M. D. (2019). Predicting entrepreneurial intentions and pre-start-up behaviour among asnaf millennials. Sustainability, 11(18), 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolova, T. S., Edelman, L. F., Shirokova, G., & Tsukanova, T. (2019). Youth entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Can family support help navigate institutional voids? Journal of East-West Business, 25(4), 363–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y., & Ye, Y. (2021). Specific antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among newly returned Chinese international students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 622276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mawson, S., & Kasem, L. (2019). Exploring the entrepreneurial intentions of Syrian refugees in the UK. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 25(5), 1128–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, N. B., & Kerkeni, S. (2021). The role of the family environment in the development of entrepreneurial intention among young Tunisian students. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 9(1), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, R., & Dominic, P. D. D. (2014). Socio-economic and psychological determinants of entrepreneurial intentions: A structural equation model. Global Business and Economics Review, 16(4), 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscio, A., Shibayama, S., & Ramaciotti, L. (2021). Universities and start-up creation by PhD graduates: The role of scientific and social capital of academic laboratories. Journal of Technology Transfer, 47(1), 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2021). On the costs of digital entrepreneurship: Role conflict, stress, and venture performance in digital platform-based ecosystems. Journal of Business Research, 125, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A., Obschonka, M., Schwarz, S., Cohen, M., & Nielsen, I. (2019). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic literature review on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, R., Scandurra, G., & Thomas, A. (2017). The emergence of innovative entrepreneurship: Beyond the intention—Investigating the participants in an academic SUC. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 14(5), 1750025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H., Li, B., Zhou, C., & Sadowski, M. (2021). How does the appeal of environmental values influence sustainable entrepreneurial intention? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Fernández, H., Martín-Cruz, N., Delgado-García, J. B., & Rodríguez-Escudero, A. I. (2020). Online and face-to-face social networks and dispositional affectivity. How to promote entrepreneurial intention in higher education environments to achieve disruptive innovations? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 588634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Macías, N., Fernández-Fernández, J. L., & Vieites, A. R. (2018, March 5–6). Relational social capital dimension and entrepreneurial intentions in online environments. International Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, C. C., Bostan, I., Robu, I.-B., & Maxim, A. (2016). An analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among students: A Romanian case study. Sustainability, 8(8), 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashantham, S. (2021). New ventures as value co-creators in digital ecosystems. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(1), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijman, R. (2001). Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions: Mexican immigrants in Chicago. Journal of Socio-Economics, 30(5), 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, M., Bullough, A., & Saeed, S. (2021). How do resilience and self-efficacy relate to entrepreneurial intentions in countries with varying degrees of fragility? A six-country study. International Small Business Journal-Researching Entrepreneurship, 39(2), 130–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamzadeh, Y., Sangosanya, T. A., Salamzadeh, A., & Braga, V. (2022). Entrepreneurial universities and social capital: The moderating role of entrepreneurial intention in the Malaysian context. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(1), 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, G., Ughetto, E., & Landoni, P. (2021). Entrepreneurial intention: An analysis of the role of Student-Led Entrepreneurial Organizations. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 19(3), 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, A. S., Soh, P.-H., Larso, D., & Chen, J. (2020). Strategic entrepreneurship in a VUCA environment: Perspectives from Asian emerging economies. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 12(4), 343. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M. S., & Ahsen, S. R. (2021). Linking entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: An interactive effect of social and personal factors. International Journal of Learning and Change, 13(1), 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, A., Abbas, A., Mazhar, S., & Lin, G. (2020). Fostering sustainable ventures: Drivers of sustainable start-up intentions among aspiring university students in Pakistan. Journal of Cleaner Production, 262, 121269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L. F., & Manolova, T. S. (2020). Moving from intentions to actions in youth entrepreneurship: An institutional perspective. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 12(1), 25–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slogar, H., Stanic, N., & Jerin, K. (2021). Self-assessment of entrepreneurial competencies of students of higher education. Zbornik Veleucilista U Rijeci-Journal of the Polytechnics of Rijeka, 9(1), 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K., & Beasley, M. (2011). Graduate entrepreneurs: Intentions, barriers and solutions. Education and Training, 53(8), 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, S., Fan, M., Soomro, S., Shaikh, S. N., Kherazi, F. Z., & Akhtar, S. (2024). Unraveling the entrepreneurial journey: The role of education, personality, and gender. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 6(2), 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniewski, M., & Awruk, K. (2016). Start-up intentions of potential entrepreneurs—The contribution of hope to success. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 29(1), 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, M., Subramanian, K., Al-Haziazi, M., & Sherimon, P. C. S. (2017, September 21–22). Entrepreneurial intent of prospective graduates in the sultanate of Oman. 12th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, ECIE 2017, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, R., Im, I., & Im, K. S. (2019). Do IT freelancers increase their entrepreneurial behavior and performance by using IT self-efficacy and social capital? Evidence from Bangladesh. Information & Management, 56(6), 103133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchokoté, I. D., Bawack, R., & Nana, A. (2025). Attitude over norms: Reevaluating the dominance of attitude in shaping entrepreneurial intentions among higher education students in global south countries. The International Journal of Management Education, 23(2), 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C. L. W., Mohd Rosdi, S. A., & Abidin, R. (2020). The influence of personal attributes and family support towards intention to start-up online business. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(6), 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D. G. T., Bui, T. Q., Nguyen, H. T., & Mai, M. T. T. (2018, June 27–29). The antecedents of entrepreneurial intention: A study among graduate students in Ho Chi Minh City. 6th International Conference on the Development of Biomedical Engineering in Vietnam, BME 2016, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, R. (2016). Does university play a significant role in shaping entrepreneurial intention? A cross-country comparative analysis. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(3), 790–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, T., & Goyayi, M. J. (2020). The influence of technology on the development of entrepreneurial self-efficacy for online business start-ups in developing nations. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 21(3), 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S. K., Gupta, S., Nagar, N., & Goel, P. (2025). Diverse perspectives on entrepreneurship: Analyzing gender and age-related differences in perceptions. Multidisciplinary Reviews, 8(2), 2025049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vracheva, V. P., Abu-Rahma, A., & Jacques, P. (2019). Effects of context on the entrepreneurial intent of female students from the United Arab Emirates. Education and Training, 61(6), 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D., Thomas, E., Teixeira, E. K., & Maehler, A. E. (2020). University entrepreneurial push strategy and students’ entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 26(2), 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, C. M. K., Meister, A., Van De Sandt, N., & Mauer, R. (2024). An emotional learning process? The role of socially induced and regulated emotions for the development of an entrepreneurial mindset. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 31(8), 2137–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., & Wang, H. P. (2024). Entrepreneurial education affects entrepreneurial intentions from the perspective of the positive emotion theory. Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences, 22(2), 5646–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H., Li, D., Wu, J., & Xu, Y. (2014). The role of multidimensional social capital in crowdfunding: A comparative study in China and the US. Information & Management, 51(4), 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F., Fan, S. X. J., & Zhao, L. (2019). Having entrepreneurial friends and following them? The role of friends’ displayed emotions in students’ career choice intentions. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 27(4), 445–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, L., Rialti, R., Tron, A., & Ciappei, C. (2021). Entrepreneurial passion, orientation and behavior: The moderating role of linear and nonlinear thinking styles. Management Decision, 59(5), 973–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).