Abstract

This study examines employees’ subjective well-being (SWB) in large Japanese corporations using a single covariance-based SEM that integrates two sources of motivation: leadership and individual dispositions. We simultaneously test the indirect effects of transformational leadership (TFL) on SWB via three workplace resources—organizational esteem/recognition (OEM), decision-making discretion (DM), and workplace intrinsic motivation/meaning (WPIM)—and the direct effects of trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM). Survey data from 600 employees indicated good model fit. Mediation via OEM and DM (but not WPIM) was supported. Higher TLIM was associated with higher SWB even after accounting for leadership and mediators; TLIM was also positively related to OEM, DM, and WPIM. WPIM was negatively related to SWB, consistent with a suppression effect under concurrent controls. Practically, recognition and discretion are actionable levers, with OEM exerting larger effects than DM. Overall, leadership acts indirectly through resources, whereas dispositions act directly. Future work should employ longitudinal and multilevel designs to establish causal generalizability.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Objectives

Employee subjective well-being (SWB) and work–life balance have long been central themes in organizational research, with substantial cultural variation (Hofstede, 2001; Ollier-Malaterre et al., 2013). In Western contexts such as the United States and Northern Europe, autonomy, flexible work arrangements, and the reduction in work–family conflict are emphasized as key drivers of well-being (Grawitch et al., 2006; Eurofound, 2023). By contrast, Japanese workplaces have traditionally been characterized by long working hours, expectations of after-hours socializing, and strong organizational attachment, which are associated with overwork, poorer mental health, and lower productivity. In response, the Japanese government introduced Work Style Reform policies (e.g., legal overtime caps, mandatory annual leave), and recent statistics continue to update the landscape of working hours and labor–management practices (MHLW, 2019; JILPT, 2025).

Against this shifting institutional and cultural backdrop, leadership and the quality of motivation are increasingly salient determinants of SWB. Transformational leadership (TFL) can enhance positive psychological states and performance through vision articulation, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation (Choi et al., 2023). Recent integrative evidence, however, indicates that a nontrivial part of TFL’s influence operates indirectly via job resources—such as discretion, recognition/feedback, and enhanced work meaning—and that construct overlap with related leadership styles warrants attention (Xue et al., 2022). Consistently, meta-analytic work grounded in the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) model reaffirms the robustness of the resources–engagement–outcomes sequence, highlighting the practical importance of resource engineering in organizations (Mazzetti et al., 2023).

Concurrently, Self-Determination Theory (SDT) clarifies that the quality of motivation connects to SWB and performance through partly distinct pathways: meta-analytic evidence positions intrinsic motivation as a proximal driver of SWB, whereas identified regulation tends to relate more strongly to performance (Van den Broeck et al., 2021). Workplace-focused reviews further synthesize how the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, relatedness) underpins adaptive outcomes, while noting design limitations in the existing evidence base (McAnally & Hagger, 2024; Coxen et al., 2021). Classic theoretical grounding is provided by SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Operational definition (terminology guardrail). In this study, we operationalize recognition (OEM), discretion (DM), and workplace intrinsic motivation/meaning (WPIM) as motivational resources—that is, workplace conditions and proximal psychological states that evoke, sustain, or channel motivation toward adaptive outcomes. Within this umbrella, OEM and DM are treated as environmental resources, whereas WPIM serves as a proximal psychological resource closely aligned with intrinsic motivation and meaning.

Despite recent advances, few studies on large Japanese firms have jointly compared—within a single model—(a) the indirect, designable pathway whereby TFL fosters motivational resources (an externally scaffolded route) and thereby affects SWB, versus (b) the direct pathway from trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM) to SWB (a person-centric route). Moreover, it remains under-examined whether TLIM also spills over to higher levels of discretion and recognition.

Present study: Using survey data from 600 employees in large Japanese corporations, we estimate a covariance-based structural equation model (SEM) that contrasts: (a) the indirect paths in which TFL affects SWB through DM, OEM, and WPIM, and (b) the direct path from TLIM to SWB. We also test whether TLIM relates positively to DM and OEM. This design allows us to (i) evaluate the relative strength of leadership-driven resource mechanisms and intrinsic-motivation mechanisms under Japan’s institutional context (MHLW, 2019; JILPT, 2025), and (ii) derive actionable implications for resource engineering—formal discretion architecture and recognition protocols (Mazzetti et al., 2023)—and for autonomy-supportive management grounded in contemporary SDT/JD–R evidence (Van den Broeck et al., 2021; McAnally & Hagger, 2024).

1.2. Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership (TFL) is a leadership approach that elevates follow ers’ values and behavior beyond immediate self-interest through vision articulation, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Recent longitudinal and integrative evidence shows that TFL can foster positive psychological states and performance (Choi et al., 2023), yet also indicates that part of its influence is indirect—operating via job resources such as discretion/autonomy, recognition/feedback, and enhanced work meaning (Xue et al., 2022). This perspective aligns with the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) model, in which resources cultivate work engagement and downstream outcomes (Mazzetti et al., 2023). Accordingly, contemporary accounts of TFL emphasize not only inspirational communication but also resource engineering (e.g., formal discretion design and routinized recognition) that enables employees’ autonomous functioning—an emphasis especially salient in Japanese organizational settings.

1.3. Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being (SWB) captures individuals’ cognitive and affective evaluations of life, typically comprising life satisfaction, positive affect, and low negative affect (Diener et al., 1985). Beyond traditional job attitudes, SWB offers a broader lens on employees’ psychological functioning. Converging with Self-Determination Theory (SDT), recent meta-analytic and review work positions intrinsic motivation as a proximal driver of SWB, whereas identified regulation tends to relate more strongly to performance outcomes (Van den Broeck et al., 2021; McAnally & Hagger, 2024). Diary and review evidence further indicates that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—underpins adaptive functioning across contexts (Coxen et al., 2021). In sum, a motivation-quality perspective complements leadership accounts by clarifying why resource-rich and autonomy-supportive environments relate to higher SWB.

1.4. Review of Prior Research and Positioning of the Present Study

Despite growing interest in leadership, motivation, and SWB, few studies jointly compare within a single model the indirect, designable TFL routes (via discretion, recognition/feedback, and work meaning) against the direct route from trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM) to SWB in large Japanese firms. Prior work often focused on task performance and job satisfaction, leaving SWB comparatively under-examined, and rarely assessed whether TLIM also spills over to higher discretion and recognition. Addressing these gaps, the present study (a) contrasts TFL → resources → SWB with TLIM → SWB, (b) tests whether TLIM relates positively to discretion and recognition, and (c) discusses implications for resource engineering—formal discretion design and recognition protocols (Mazzetti et al., 2023)—and for autonomy-supportive management grounded in contemporary SDT/JD–R evidence (Van den Broeck et al., 2021; McAnally & Hagger, 2024).

Drawing on contemporary SDT–JD–R integrations, we test in a single first-order SEM a two-layer mechanism—TFL influencing SWB indirectly through OEM and DM, and TLIM relating directly to SWB—thereby updating the theoretical framing and linking resource engineering with autonomous motivation.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Focus and Theoretical Framework

The objective is to examine how two distinct sources of motivation—externally scaffolded mechanisms of transformational leadership (TFL) and stable internal dispositions of trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM)—contribute to employees’ subjective well-being (SWB). Grounded in the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) model and Self-Determination Theory (SDT), we expect TFL to operate indirectly by enriching job resources (e.g., decision-making discretion and recognition/esteem) and by enhancing work meaning/intrinsic motivation (Van den Broeck et al., 2021; McAnally & Hagger, 2024). We further expect these job-resource levers—particularly discretion design and recognition protocols—to function as actionable mechanisms (Mazzetti et al., 2023). By contrast, TLIM should exhibit a direct association with SWB (McAnally & Hagger, 2024). We test a covariance-based SEM on survey data from 600 employees in large Japanese corporations, estimating direct, indirect, and total effects with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals.

2.2. Hypotheses

This study specifies a single structural equation model (SEM) to examine how trans formational leadership (TFL) and trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM) relate to subjective well-being (SWB) via three job-motivational resources: organizational esteem/recognition (OEM), decision-making discretion (DM), and workplace intrinsic motivation/meaning (WPIM). In this specification, no direct path is set from TFL to SWB; the influence of TFL is evaluated solely through the motivational mediators, whereas TLIM—as an individual motivational disposition—retains a direct path to SWB. Accordingly, we hypothesize that TFL exerts a positive indirect effect on SWB through OEM, DM, and WPIM (H1), with the specific indirect effects TFL → OEM → SWB (H1a) and TFL → DM → SWB (H1b) expected to be positive, and the TFL → WPIM → SWB pathway tested on an exploratory basis without a directional constraint (H1c). We further expect TLIM to show a positive direct association with SWB (H2). To make the upstream links explicit, we posit that TFL positively predicts OEM, DM, and WPIM (H3a–H3c), and that TLIM likewise positively predicts OEM, DM, and WPIM (H4a–H4c). Finally, for the downstream relations we explore positive associations between OEM and SWB (H5a), between DM and SWB (H5b), and between WPIM and SWB (H5c).

All hypotheses are estimated simultaneously within a single SEM. We report standardized coefficients (β), significance levels, and key fit indices (e.g., CFI, TLI, RMSEA). Mediation is adjudicated using the joint-significance criterion—that is, mediation is supported when both the upstream (a) and downstream (b) paths are statistically significant—and non-significant paths are visually distinguished in the figure as needed. This design enables the status of H1–H5c to be read directly from a single SEM diagram.

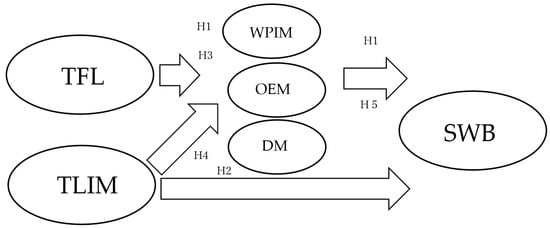

2.3. Research Model

Guided by the hypotheses, we specified a structural equation model (Figure 1). Transformational leadership (TFL) and trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM) were modeled as exogenous predictors of subjective well-being (SWB). Mediation was specified in parallel through three job-motivational resources: organizational esteem/recognition (OEM), decision-making discretion (DM), and workplace intrinsic motivation/meaning (WPIM). Accordingly, within a single SEM we estimated the indirect paths TFL → {OEM, DM, WPIM} → SWB and TLIM → {OEM, DM, WPIM} → SWB, as well as the direct path TLIM → SWB.

Figure 1.

Note. TFL = Transformational Leadership; TLIM = Trait-Level Intrinsic Motivation; OEM = Organizational Esteem/Recognition; DM = Decision-Making Discretion; WPIM = Workplace Intrinsic Motivation/Meaning; SWB = Subjective Well-Being.

2.4. Participants

This study targeted full-time employees in large corporations headquartered in Japan (300+ employees). Eligibility required respondents to be 20–49 years old with at least two years of tenure in their current organization. To enhance generalizability, no restrictions were placed on industry or job function. Data were collected via a nationwide online panel administered by a major survey research firm, using stratified random sampling to balance sex, age, and region. In total, 600 valid responses were obtained, with equal allocation by sex and age group (100 men and 100 women in each of the 20 s, 30 s, and 40 s strata).

Employment status. General employees, 66.3%; managers, 6.0%; company owners/executives, 0.7%; public servants/teachers/non-profit employees, 27.0%.

Industry (employer sector). Energy/Materials/Industrial Machinery, 13.7%; Food, 5.8%; Beverages/Tobacco, 1.0%; Pharmaceuticals/Medical Supplies, 6.5%; Cosmetics, 1.7%; Fashion/Accessories, 3.0%; Precision Machinery/Office Products, 4.2%; Consumer Electronics/AV Equipment, 4.8%; Automotive/Transport Equipment, 11.2%; Household Goods, 0.3%; Sporting Goods, 0.5%; Distribution/Retail, 10.3%; Government/Public Bodies, 21.8%; Education/Healthcare/Religious Services, 15.2%.

Firm size (employees). 300–499, 14.3%; 500–999, 20.7%; 1000–9999, 40.4%; 10,000+, 24.5%.

Tenure. 2–5 years, 27.0%; 6–10 years, 29.3%; 11–15 years, 17.8%; 16+ years, 25.8%.

2.5. Survey Period and Ethical Considerations

The survey was administered via a web-based questionnaire from November to December 2024. Before participation, all respondents received a clear explanation of the study objectives and data-handling procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. All responses were anonymous, and no personally identifiable information (PII) was collected at any stage. The university’s ethics review committee reviewed and approved the study protocol (Approval No. 2024-56).

2.6. Measurement Scales

All constructs were assessed with Japanese instruments that have established validity and reliability or with Japanese versions of established scales, using a five-point Likert format (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) (See Appendix). Transformational leadership (TFL) was measured with eight items corresponding to transformational characteristics drawn from the reorganized Japanese translation of the MLQ Form 6S (Nishio, 2008). Trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM) was captured with three items from the Vitality factor of the Vigor Scale, reflecting spontaneous energy and perseverance toward tasks (Akiyama et al., 2003). Workplace intrinsic motivation/meaning (WPIM)—the experienced enjoyment/interest in daily work and the perceived meaningfulness of work—was measured with five items from the Workplace Intrinsic Motivation Scale (Shiotsuki et al., 2019). Organizational esteem/recognition (OEM) was assessed with three items from the Other-Evaluation (recognition) Scale, indexing the perceived frequency and fairness of acknowledgment from supervisors and the organization (Morita, 2006). Decision-making discretion (DM) was measured with three items from the Workplace Discretion Scale, tapping freedom in method selection, scheduling, and decision authority within one’s role (Morita, 2006). Subjective well-being (SWB) was operationalized as the cognitive component of well-being (life satisfaction) using the Japanese version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale modeled as a single latent factor (Diener et al., 1985). All items were coded such that higher scores indicate higher levels of the corresponding construct.

2.7. Analytical Procedures

Before estimating the structural model, we conducted a multi-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS on the integrated measurement model to verify the measurement structure and to assess construct validity and internal consistency. Model fit was evaluated using χ2/df, GFI, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA against standard cutoffs (e.g., GFI ≥ 0.90; CFI/TLI ≥ 0.90–0.95; RMSEA ≤ 0.08, ideally ≤ 0.06). We report reliability (Cronbach’s α, composite reliability [CR]), convergent validity (average variance extracted [AVE]), and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT). We then estimated path coefficients with structural equation modeling (SEM) and tested both direct and mediated effects corresponding to Hypotheses 1–5.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model Results

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS indicated good fit to the data: χ2(237) = 559.687, p < 0.001; χ2/df = 2.362; CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.963, IFI = 0.968, NFI = 0.946; GFI = 0.925, AGFI = 0.905; RMSEA = 0.048 (90% CI [0.043, 0.053], PCLOSE = 0.768); RMR = 0.041. All standardized factor loadings were significant and exceeded 0.60. A full listing of fit indices appears in Supplementary Materials Table S1.

Reliability and convergent validity. Composite reliability was adequate across con structs (CR = 0.817–0.942), and average variance extracted met the 0.50 benchmark for all constructs except WPIM (AVE = 0.496), which we judge as marginally acceptable given its CR (0.831) and theoretically coherent item content. See Supplementary Materials Table S2 for CR/AVE values and loading ranges.

Discriminant validity. HTMT ratios were below 0.85 for all construct pairs (maximum = 0.681 between TFL and OEM), supporting discriminant validity. The full HTMT matrix is provided in Supplementary Materials Table S3.

3.2. Hypothesis-Testing Results

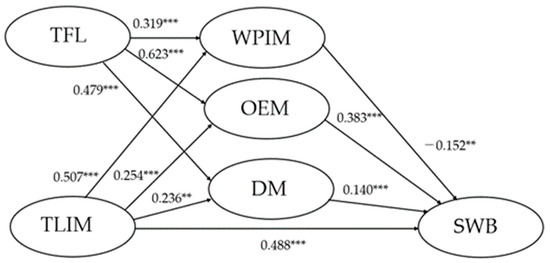

Based on the proposed hypotheses, we estimated a structural equation model (SEM); results for H1–H5 are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Note. Reported coefficients are standardized. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

- Model fit. The structural model exhibited good fit to the data, χ2(242) = 769.27, χ2/df = 3.18, CFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.940, RMSEA = 0.060. The SEM model fit is provided in the Supplementary Materials as Table S4.

H1 (Mediating effects of TFL).

Using the joint-significance criterion, mediation via OEM and DM was supported: TFL → OEM → SWB (TFL → OEM: β = 0.623 ***; OEM → SWB: β = 0.383 ***) and TFL → DM → SWB (TFL → DM: β = 0.479 ***; DM → SWB: β = 0.140 **). An exploratory test of TFL → WPIM → SWB (TFL → WPIM: β = 0.319 ***; WPIM → SWB: β = −0.152 **) was not supported as hypothesized because the WPIM → SWB path was negative (contrary to the expected positive sign).

H2 (Direct effect of TLIM).

TLIM showed a strong positive direct association with SWB (β = 0.488 ***); thus, H2 was supported.

H3 (Upstream effects of TFL on motivation).

TFL positively predicted all three motiva tional constructs—OEM (β = 0.623 ***), DM (β = 0.479***), and WPIM (β = 0.319 ***)—supporting H3a–H3c.

H4 (Upstream effects of TLIM on motivation).

TLIM positively predicted WPIM (β = 0.507 ***; H4c), OEM (β = 0.254 ***; H4a), and DM (β = 0.236 ***; H4b), supporting H4a–H4c.

H5 (Downstream paths to SWB).

OEM (β = 0.383 ***) and DM (β = 0.140 **) were posi tively related to SWB, supporting H5a–H5b. By contrast, WPIM showed a significant negative association with SWB (β = −0.152 **), contrary to H5c.

The results indicate that transformational leadership (TFL) influences employees’ subjective well-being (SWB) primarily indirectly, with the principal routes running through organizational esteem/recognition (OEM) and decision-making discretion (DM) as workplace motivational resources. Concretely, hallmark TFL behaviors—articulating vision, providing individualized consideration, and offering intellectual stimulation—heighten employees’ sense of being fairly recognized by supervisors and the organization and expand discretion over how work is conducted and distributed; these, in turn, spill over to the cognitive facet of SWB (life satisfaction). By contrast, trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM) exhibited a strong direct effect on SWB and positively predicted OEM, DM, and workplace intrinsic motivation/meaning (WPIM), suggesting that TLIM supplies foundational motivational resources into the downstream mediation network. In short, individuals’ spontaneous energy, interests, and curiosity appear to elevate well-being independently of leadership while also contributing to motivational activation at work.

At the same time, the association between WPIM and SWB was negative. Given that the measurement model fit was adequate overall and that OEM and DM were entered concurrently, the unique (residual) component of WPIM may have manifested as a suppression effect, yielding a negative coefficient. Theoretically, stronger meaning or immersion can raise role demands and personal standards; in some situations—e.g., when heightened meaning is accompanied by excessive self-imposed demands or fatigue—this may exert a neutral to negative influence on life satisfaction. In any case, the WPIM finding warrants caution. Future research should (i) incorporate affective well-being indicators, (ii) adopt panel/longitudinal designs, and (iii) explicitly introduce controls and moderators such as job demands, workload, and role conflict to determine whether the negative sign is structural or context dependent.

Taken together, the model supports a complementary mechanism whereby leadership acts indirectly via workplace motivational resources (OEM, DM), whereas individual dispositions (TLIM) act directly. In practice, a two-pronged approach is indicated: (a) develop TFL by making recognition more visible, frequent, and fair and by redesigning discretion, and (b) build an autonomy-supportive environment that sustains TLIM (e.g., self-determination–oriented goal setting, learning opportunities, and alignment between discretion and expectations). These implications are consistent with the structural estimates in Figure 2 (good fit and significant paths) and set up the next section’s policy proposals linked to Japan’s institutional context (e.g., work-style reforms and curbing long working hours).

4. General Discussion

4.1. Summary: Concurrent Evidence for a Two-Layer Mechanism

This study concurrently estimated, within a single SEM, the pathways through which two layers of influence—transformational leadership (TFL) as environmental resource engineering and trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM) as personal intrinsic vitality—reach subjective well-being (SWB) via organizational esteem/recognition (OEM), decision-making discretion (DM), and workplace intrinsic motivation/meaning (WPIM). The results reveal the coexistence of (a) indirect effects of TFL on SWB via OEM and DM and (b) a strong direct effect of TLIM on SWB. Taken together, the pattern bridges the JD–R model’s resource pathway and SDT’s health advantages of autonomous motivation, aligning with recent integrative accounts (e.g., Hoch et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Van den Broeck et al., 2021; Hagger & Hamilton, 2021).

4.2. Consistency with Recent Evidence

Direct effect of TLIM. The direct effect of TLIM is consistent with SDT’s claim that the quality of autonomous motivation shapes well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and with recent meta-analytic evidence incorporating general causality orientations (Hagger & Hamilton, 2021). It also supports an individual-level effect whereby life satisfaction—the cognitive facet of SWB—is elevated regardless of workplace conditions.

Resource pathway of TFL. The finding that TFL operates through job-motivational resources—organizational esteem/recognition (OEM) and decision-making discretion (DM)—aligns with the JD–R view that resources activate and promote health and performance (Van den Broeck et al., 2021) and with integrative reviews documenting TFL’s relative utility (Hoch et al., 2018).

Practical direction. The implications converge with recent intervention research emphasizing the design of recognition (quality, frequency, fairness of feedback) and the architecture of discretion (scope of authority, information access, skill training) as core levers (Mazzetti et al., 2023).

4.3. Consistency and Divergence with Theory

The observed association between WPIM and SWB was negative and significant, which diverges from SDT’s positive link between autonomous motivation and well-being, the JD–R “resource pathway,” and meta-analytic evidence on meaningful work and happiness (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Van den Broeck et al., 2021; Allan et al., 2019; Allan & Blustein, 2022). Because OEM and DM were entered concurrently, the residual component of WPIM (after shared variance is partialed out) may function as a suppressor on life satisfaction. Overinternalization, role expansion, or self-sacrificial commitment could, under certain conditions, depress private-life satisfaction—especially in Japan, where long hours and conformity pressures persist. Accordingly, enhancing “meaning” should be recommended only in tandem with demand management (workload and role clarity) and with motivational resources.

OEM exerted a larger effect on SWB than DM. In large Japanese firms, high-quality, fair, and timely recognition can more directly elevate psychological safety and perceived internal status; interventions that institutionalize recognition that is specific, frequent, and peer-based are effective (Mazzetti et al., 2023). DM remained positive but smaller; when the quality of discretion (clear authority boundaries, access to information, skill supports) is weak, delegation can increase strain. Stage-gated allocation of discretion and targeted skill training are therefore recommended.

TLIM (trait) and TFL (context) act as complements, not substitutes: TLIM sets the baseline of vitality, while TFL improves the environment through resource design. Autonomy-supportive management bridges these routes, enabling synergistic effects (Ryan & Deci, 2017; McAnally & Hagger, 2024).

4.4. Connection to Institutional and Cultural Contexts

Japan’s ongoing “Work Style Reform” has accelerated institutional demands for mak ing discretion visible and recognition transparent. In practice, organizations are increasingly expected to clarify the scope within which employees may decide autonomously, and to specify the frequency, content, and procedural fairness of feedback. In light of the present findings, it is effective to retrain transformational leadership (TFL) not as compliance-oriented supervision but as a capability to support subordinates’ autonomy and to engineer workplace resources. Concretely, this entails sustaining autonomy by offering choices and explaining the rationale for directions; administering recognition that is immediate, specific, and procedurally fair to both behavior and process; and designing discretion through explicit decision rights, information access, and decision-skill development. Aligned with these institutional trends, such practices enable a sustained virtuous cycle from TFL to enhanced organizational esteem/recognition (OEM) and decision-making discretion (DM), and ultimately to higher subjective well-being (SWB) (Hoch et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Van den Broeck et al., 2021).

4.5. Practical Implications

This study indicates that transformational leadership (TFL) enhances two job-motivational resources—recognition (OEM) and discretion (DM)—which, in turn, spill over to subjective well-being (SWB), while trait-level intrinsic motivation (TLIM) exerts a strong direct effect on SWB. Practically, three prescriptions follow. First, improve both the quality and perceived fairness of recognition by delivering specific, timely feedback supported by transparent evaluation criteria and processes. Second, (re)design discretion by clarifying decision rights and boundaries and by providing access to relevant information and decision-making supports. Third, institutionalize autonomy-supportive management in day-to-day operations—for example, by presenting options and rationales, scaffolding employees’ sense of competence, and cultivating high-quality relationships (Mazzetti et al., 2023).

Notably, in our model the path from workplace intrinsic motivation/meaning (WPIM) to SWB was negative. Accordingly, initiatives to strengthen “meaning” should always be paired with workload management and the reduction in role ambiguity. Promoting a sense of purpose without concurrent demand management can backfire—especially for the cognitive component of SWB (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Van den Broeck et al., 2021).

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Because this study relies on cross-sectional data, causal inferences should be drawn with caution. Future work should employ longitudinal surveys or experience sampling to test the temporal ordering and lagged effects whereby TFL and TLIM influence OEM, DM, and WPIM, and in turn SWB. The current unit of analysis is restricted to individuals; to disentangle the effects of departmental and team practices, multilevel SEM that treats recognition and discretion at the division/section level as higher-level contextual factors would be informative. Our outcomes also focused on the cognitive facet of SWB; extending the criterion space to affective well-being, health indicators, turnover intention, and performance would help assess the breadth and practical significance of the effects.

In addition, introducing moderators—such as job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014), perceived justice (Colquitt et al., 2013), leader–member exchange (LMX) (Dulebohn et al., 2012), and the proportion of remote work (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007)—would clarify the conditions under which the signs and magnitudes of the structural paths vary. To refine measurement, WPIM could be decomposed into lower-order dimensions (e.g., meaning, enjoyment, flow) to probe multicollinearity and suppression effects, accompanied, where appropriate, by abbreviated or reconfigured scales. Finally, testing measurement invariance (by gender, age, and occupation), implementing common-method variance (CMV) reduction procedures, preregistering analyses, and reporting robustness checks would strengthen both the external and causal validity of a resource-design model that integrates SDT and JD–R (Hagger & Hamilton, 2021; McAnally & Hagger, 2024).

4.7. Conclusions

In summary, the evidence supports a two-layer mechanism that is theoretically contemporary and contextually consistent with Japan’s institutional environment: individual autonomous vitality (TLIM) directly elevates SWB, whereas leadership (TFL) exerts its influence indirectly through motivational resources—organizational esteem/recognition (OEM) and decision-making discretion (DM)—with implications consistent with recent reviews and meta-analyses (Hoch et al., 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Van den Broeck et al., 2021). The negative WPIM → SWB association indicates that “meaning” should be designed inseparably from demand management (workload and role clarity; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Van den Broeck et al., 2021). Practically, an implementation core built on autonomy support, recognition, and discretion is well positioned to deliver sustained improvements in employee well-being (Mazzetti et al., 2023; see also Hagger & Hamilton, 2021).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/admsci15110431/s1, Table S1: CFA Model Fit Indices; Table S2: Summary of Measurement Model Reliability and Convergent Validity; Table S3: Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) Ratio Matrix; Table S4: SEM fit indices (primary and parsimony-adjusted).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and N.K.; methodology, M.S., R.L. and N.K.; validation, M.S., R.L. and N.K.; formal analysis, M.S. and R.L.; investigation, M.S. and N.K.; resources, N.K.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft, M.S.; writing—review & editing, M.S.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, N.K.; project administration, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Research Ethics Committee for Studies Involving Human Subjects, Kyoto Institute of Technology, protocol code: 2024-56; approval date: 20 August 2024; notification date: 4 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality considerations, but they may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used AI-assisted tools for language polishing and formatting (e.g., ChatGPT 5). The authors reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. If applicable: The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

See Appendix for the full list of survey items.

Please indicate the extent to which each statement applies to you (or to your supervisor) over the past year.

(Example scale: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree.)

| Q1. About Your Immediate Supervisor in the Past Year |

| Please think of the supervisor with whom you had the most contact over the past year, and respond to the following statements about that supervisor’s behaviors and activities. |

| Q1_1 Does your supervisor strive to improve the atmosphere around you (including you and your coworkers)? |

| Q1_2 Do you feel proud to be able to work with your supervisor? |

| Q1_3 Does your supervisor clearly express what needs to be done in easy-to-understand terms? |

| Q1_4 Does your supervisor provide inspiring images or visions that raise your motivation? |

| Q1_5 Does your supervisor help you find meaning in your work? |

| Q1_6 Do you trust your supervisor enough to defend and justify their decisions even when they are not present? |

| Q1_7 Even in difficult situations, can you trust that your supervisor’s policy or direction is the right one? |

| Q1_8 Does your supervisor show concern even for those around you who may be disliked by others? |

| Q1_9 Does your supervisor offer new ways of looking at difficult matters from different perspectives? |

| Q1_10 Does your supervisor encourage you to reconsider things that you previously took for granted? |

| Q1_11 Does your supervisor encourage you to try new methods for solving problems? |

| Q1_12 Does your supervisor support your self-development for personal growth? |

| Q1_13 Does your supervisor help you solve work problems regardless of formal authority boundaries? |

| Q1_14 Does your supervisor appropriately communicate how they feel about your behavior? |

| Q1_15 Regardless of formal authority, does your supervisor make personal sacrifices to help you? |

| Q1_16 Does your supervisor prompt people in the workplace to stay focused on achieving goals? |

| Q1_17 Does your supervisor emphasize goal attainment and recognize you when goals are achieved? |

| Q1_18 Does your supervisor indicate the standards that should be met in performing work? |

| Q1_19 Is your supervisor satisfied when you at least meet the pre-set minimum performance level? |

| Q1_20 Does your supervisor clearly explain what you need to do to receive rewards commensurate with your work? |

| Q2. Your Work Situation in the Past Year (Competitive/Relational/Growth Persistence) |

| Q2_1 Achieving superior results (performance, evaluations) compared to your coworkers is a major source of joy for you. |

| Q2_2 You persist in your duties without giving up until you achieve results superior to your coworkers. |

| Q2_3 You work very hard so as not to lose to your coworkers. |

| Q2_4 You make ongoing efforts to get along well with others. |

| Q2_5 You continuously engage in efforts to build good relationships with coworkers. |

| Q2_6 You pay close attention to being cooperative with coworkers and supervisors. |

| Q2_7 You think about how you can further develop yourself. |

| Q2_8 You work with the view that you should acquire more advanced knowledge and skills. |

| Q2_9 You devote energy to growing beyond your current level. |

| Q2_10 You persist until you complete your tasks. |

| Q2_11 You engage in your duties with a strong sense of purpose in completing assigned tasks. |

| Q2_12 You never give up until you fully carry out your assigned duties. |

| Q3. Your Job Characteristics and Work Engagement in the Past Year |

| Q3_1 Even away from the workplace, you often think about how to proceed with your work. |

| Q3_2 In your private time, you study things that you can use for your work. |

| Q3_3 Outside the workplace, you often jot down ideas related to your work. |

| Q3_4 You habitually work harder than what is expected of you. |

| Q3_5 When you talk about work, time seems to pass quickly. |

| Q3_6 Through your work, you feel you are contributing to what your company aims to achieve. |

| Q3_7 Your job always has things to do; you are seldom left idle. |

| Q3_8 Through your work, you feel you are being useful to others in society. |

| Q3_9 Your job is not monotonous; it allows you to do various things. |

| Q3_10 Your job allows you to direct or mobilize other employees. |

| Q3_11 Thanks to your work, you are recognized as a respectable person in society. |

| Q3_12 When you do good work, people in your company acknowledge or praise you. |

| Q3_13 You think your pay is appropriate for your work. |

| Q3_14 In your job, if you work hard, there is a possibility of promotion. |

| Q3_15 You can make work-related decisions freely by yourself. |

| Q3_16 You can try your own ways of doing things in your work. |

| Q3_17 Your job allows you to proceed at your own pace. |

| Q4. Your Own Leadership toward Subordinates/Coworkers in the Past Year |

| Please respond regarding your own behaviors toward subordinates and coworkers over the past year. |

| Q4_1 You strive to improve the atmosphere around your subordinates and coworkers. |

| Q4_2 You feel proud to be able to work with your subordinates and coworkers. |

| Q4_3 You express what needs to be done to your subordinates and coworkers in clear, understandable terms. |

| Q4_4 You provide inspiring images or visions that raise subordinates’ and coworkers’ motivation. |

| Q4_5 You help subordinates and coworkers find meaning in their work. |

| Q4_6 Even when you are absent, your subordinates and coworkers trust you enough to defend and justify your decisions. |

| Q4_7 Even in difficult situations, your subordinates and coworkers believe your policy or direction is the right one. |

| Q4_8 You show concern for people who may be disliked by others around your subordinates and coworkers. |

| Q4_9 You offer new ways of looking at difficult matters from different perspectives to your subordinates and coworkers. |

| Q4_10 You ask your subordinates and coworkers to reconsider things they previously took for granted. |

| Q4_11 You encourage your subordinates and coworkers to try new methods of problem solving. |

| Q4_12 You support your subordinates’ and coworkers’ self-development for their growth. |

| Q4_13 You help solve work problems for subordinates and coworkers regardless of formal authority boundaries. |

| Q4_14 You appropriately communicate how you feel about your subordinates’ and coworkers’ behaviors. |

| Q4_15 Regardless of formal authority, you make personal sacrifices to help subordinates and coworkers. |

| Q4_16 You prompt people in the workplace to stay focused on achieving goals. |

| Q4_17 You emphasize goal attainment and recognize subordinates and coworkers when goals are achieved. |

| Q4_18 You indicate the standards that should be met in performing work. |

| Q4_19 You are satisfied when people at least meet the pre-set minimum performance level. |

| Q4_20 You clearly explain what subordinates and coworkers need to do to obtain rewards commensurate with their work. |

| Q5. Your Current Behaviors, Feelings, and Life Satisfaction |

| Q5_1 You make an effort in whatever you do. |

| Q5_2 You never give up on anything until the very end. |

| Q5_3 You do not give up on your goals. |

| Q5_4 You always feel highly motivated. |

| Q5_5 You are always fired up (highly energized). |

| Q5_6 You consistently feel brimming with energy. |

| Q5_7 You can maintain concentration on a single task. |

| Q5_8 You can immerse yourself in a single task. |

| Q5_9 Even in difficult situations, you intend to somehow work things out in the end. |

| Q5_10 You can bring out your strength even when you are under pressure. |

| Q5_11 You can concentrate at critical moments. |

| Q5_12 You never give up on anything. |

| Q5_13 In most respects, your life is close to your ideal. |

| Q5_14 You think your life is going very well. |

| Q5_15 You are satisfied with your life. |

| Q5_16 So far, you have obtained the important things you want in life. |

| Q5_17 If you could live your life over, you would change very little. |

Appendix B. Survey Items (Summary)

In the present study, survey items were drawn from five sections (Q1–Q5), but only Q1, Q3, and Q5 were employed in the analysis:

| Q1. Transformational leadership (supervisor-focused behaviors): |

| Items assessing inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, and contingent reward/standards, adapted to the Japanese workplace context. |

| Q3. Job characteristics and workplace motivation (extrinsic and intrinsic contexts): |

| Items covering cognitive engagement beyond work, task variety, meaning of contribution, recognition, pay/promotion, and autonomy/discretion. |

| Q5. Trait-level vitality and life satisfaction: |

| Items derived from the Kiryoku (vitality) scale (Akiyama et al., 2003) assessing energy, persistence, and effort, along with items adapted from the Satisfaction with Life Scale |

References

- Akiyama, Y., Kinoshita, A., & Sugimura, M. (2003). Kiryo-ku shakudo no sakusei oyobi kiryo-ku to shoyōin to no kanren ni tsuite [The development of “Kiryoku” scale: The scale for psychological energy of college students]. Rinshō Shiseigaku Nenpō (Annals of Clinical Thanatology), 8, 50–64. Available online: https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/repo/ouka/all/4115/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Allan, B. A., Batz-Barbarich, C., Sterling, H. M., & Tay, L. (2019). Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B. A., & Blustein, D. L. (2022). Precarious work and workplace dignity during COVID-19: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 136, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. In P. Y. Chen, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (Vol. 3, pp. 37–64). Wiley-Blackwell. Work and wellbeing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-E., Zeike, S., Lindert, L., & Pfaff, H. (2023). Transformational leadership and employee mental health: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Rodell, J. B., Long, D. M., Zapata, C. P., Conlon, D. E., & Wesson, M. J. (2013). Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coxen, L., Van der Vaart, L., & Van den Broeck, A. (2021). Basic psychological needs in the work context: A systematic literature review of diary studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 698526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of ante cedents and consequences of LMX. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. (2023). Living and working in Europe 2023. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grawitch, M. J., Gottschalk, M., & Munz, D. C. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 58(3), 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2021). General causality orientations in self-determination theory: Meta-analysis and test of a process model. European Journal of Personality, 35(5), 710–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., & Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 44(2), 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JILPT). (2025). Databook of international labour statistics 2025. Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/english/estatis/databook/index2025.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Mazzetti, G., Schaufeli, W. B., & Guglielmi, D. (2023). Are work engagement and burnout opposite states? A critical review and meta-analysis. Psychological Reports, 126(3), 1218–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnally, K. A., & Hagger, M. S. (2024). The psychological need to work: A theory of motivation at work grounded in self-determination theory. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). (2019). Rōdō keizai no bunseki (2019) [Labor economy analysis 2019]. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/wp/hakusyo/roudou/19/19-1.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Morita, S. (2006). Nihon no kaishain ni okeru teichaku shikō to shokumu manzokukan to no kanren [Intention to serve the same company for long years and job satisfaction in Japanese workers]. Shinrigaku Kenkyū (The Japanese Journal of Psychology), 76(6), 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nishio, K. (2008). Kigyō henkaku ni shisuru jinteki shigen kanri: Forowā no shutaisei hakkī no katei ni rīdāshippu ga oyobosu eikyō [Human resource management for corporate transformation: The influence of leadership on developing proactive followers]. Rikkyo Business Design Review, 5, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollier-Malaterre, A., Valcour, M., den Dulk, L., & Kossek, E. E. (2013). Theorizing national context to develop comparative work–life research: A review and research agenda. European Management Journal, 31(5), 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press. Available online: https://www.guilford.com/books/Self-Determination-Theory/Ryan-Deci/9781462538966 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Shiotsuki, A., Mihara, Y., Furuya, J., Atsu, K., & Hirakimoto, H. (2019). Mokuhyō kanri seido no un’yō to jūgyōin no naihatsu-teki mōtibēshon no kankei [The impact of MBO on employees’ intrinsic motivation]. The Japanese Journal of Labour Studies, 61(8), 86–100. Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/institute/zassi/backnumber/2019/08/pdf/086-100.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Van den Broeck, A., Howard, J. L., Van Vaerenbergh, Y., Leroy, H., & Gagné, M. (2021). Beyond intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis on self-determination theory’s multidimensional conceptualization of work motivation. Organizational Psychology Review, 11(3), 240–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y., Li, X., & Wang, Y. (2022). Transformational leadership and employees’ well-being: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 941161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).