From Entrepreneurial Alertness to Commitment to Digital Startup Activities: A Mediation Model of Perceived Desirability, Feasibility, and Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Entrepreneurial Potential Model

2.2. Actual Behavior and Commitment to Startup Activities

2.3. Perceived Desirability and Feasibility

2.4. Digital Entrepreneurial Alertness

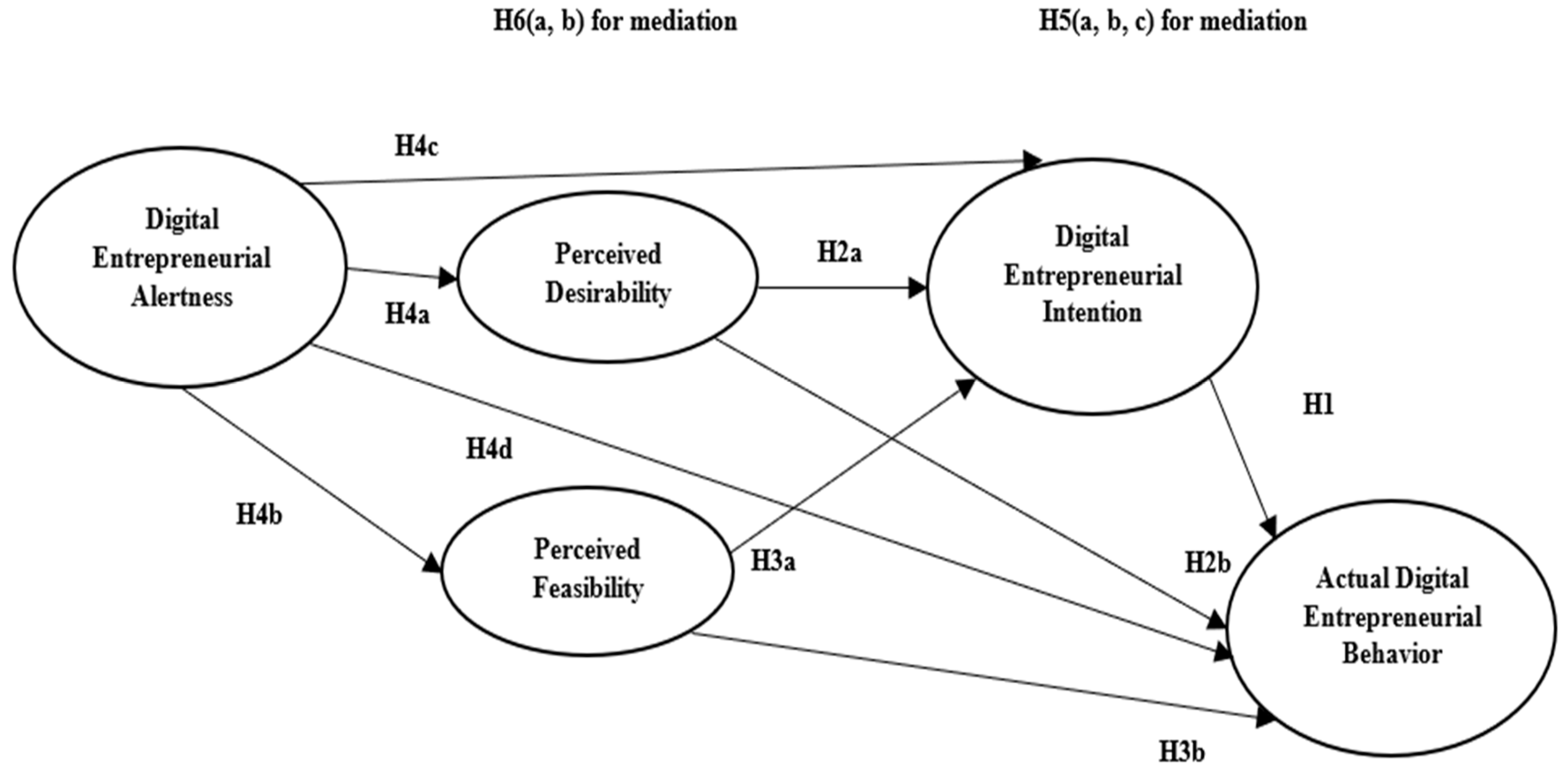

2.5. The Mediating Role of DEI

2.6. The Mediating Role of EPM Antecedents on the DEA and DEI Relationship

2.7. Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedures

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Strategy of Analysis

3.3.1. Reliability and Validity Assessment

3.3.2. Correlations Matrix and Discriminant Validity

3.3.3. Measurement Model and Model Fit

3.3.4. Common Methods Bias

3.3.5. Structural Model

4. Results

4.1. Structural Modeling and Hypotheses Testing

4.2. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPM | Entrepreneurial Event/Potential Model |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| ADEB | Actual Digital Entrepreneurial Behavior |

| DEI | Digital Entrepreneurial Intentions |

| DEA | Digital Entrepreneurial Alertness |

References

- Abaddi, S. (2024). Digital skills and entrepreneurial intentions for final-year undergraduates: Entrepreneurship education as a moderator and entrepreneurial alertness as a mediator. Management & Sustainability: An Arab Review, 3(3), 298–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alferaih, A. (2022). Starting a new business? Assessing university students’ intentions towards digital entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y. H. S., Abdulrab, M., Alwaheeb, M. A., & Alshammari, N. G. M. (2020). Factors impacting entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Saudi Arabia: Testing an integrated model of TPB and EO. Education and Training, 62(7–8), 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y. H. S., & Alraja, M. M. (2022). Understanding entrepreneurship intention and behavior in the light of TPB model from the digital entrepreneurship perspective. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, W. (2017). Investigating entrepreneurial intentions and behaviours of Saudi distance business learners: Main antecedents and mediators. Journal for International Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 10(3), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, W. (2022). The influence of institutional context on entrepreneurial intention: Evidence from the Saudi young community. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 16(5), 677–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, W., Ayadi, F., Ramadani, V., & Dana, L.-P. (2024). Dreaming digital or chasing new real pathways? Unveiling the determinants shaping Saudi youth’s digital entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(2/3), 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, S., & Bhunia, A. K. (2024). A serial mediation model of the relationship between digital entrepreneurial education, alertness, motivation, and intentions. Sustainability, 16(20), 8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliaeva, T., Ferasso, M., Kraus, S., & Damke, E. J. (2020). Dynamics of digital entrepreneurship and the innovation ecosystem: A multilevel perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(2), 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biclesanu, I., Savastano, M., Chinie, C., & Anagnoste, S. (2023). The role of business students’ entrepreneurial intention and technology preparedness in the digital age. Administrative Sciences, 13(8), 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A., & Verma, R. K. (2021). Attitude and alertness in personality traits: A pathway to building entrepreneurial intentions among university students. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 30(2), 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A., & Popovici, N. (2024). Social inclusion: A factor that influences the sustainable entrepreneurial behavior of generation Z. Administrative Sciences, 14(3), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps, C., Kraus, S., Thomas, A., Tiberius, V., & Jones, P. (2025). Digital entrepreneurship: A review, research synthesis, and development of a framework. Technology in Society, 84, 103124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A., Nguyen, V. H. A., & Delladio, S. (2025). Risk-taking, knowledge, and mindset: Unpacking the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 21(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavoushi, Z. H., Zali, M. R., Valliere, D., Faghih, N., Hejazi, R., & Dehkordi, A. M. (2021). Entrepreneurial alertness: A systematic literature review. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 33(2), 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.-P., Crocco, E., Culasso, F., & Giacosa, E. (2024). Mapping the field of digital entrepreneurship: A topic modeling approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20(2), 1011–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A. D., Adeel, S., & Botelho, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial alertness research: Past and future. Sage Open, 11(3), 21582440211031535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, G., Margherita, A., & Passiante, G. (2020). Digital entrepreneurship ecosystem: How digital technologies and collective intelligence are reshaping the entrepreneurial process. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 150, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnadi, M., & Gheith, M. H. (2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystem, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention in higher education: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A., & Liñán, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellnhofer, K., & Mueller, S. (2018). “I want to be like you!”: The influence of role models on entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 26(02), 113–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganefri, Waras, Trisno, B., Nordin, N. M., Hidayat, H., Rahmawati, Y., & Nurhidayatulloh. (2025). Cultivating digital entrepreneurs: Unravelling factors shaping digital entrepreneurship intention among engineering students in higher education. The International Journal of Management Education, 23(2), 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM. (2025). 2024/2025 global report: Entrepreneurship reality check. GEM. [Google Scholar]

- Gieure, C., Benavides-Espinosa, M. d. M., & Roig-Dobón, S. (2020). The entrepreneurial process: The link between intentions and behavior. Journal of Business Research, 112, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M., Rialp, J., & Urbano, D. (2008). The impact of desirability and feasibility on entrepreneurial intentions: A structural equation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(1), 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaén, I., & Liñán, F. (2013). Work values in a changing economic environment: The role of entrepreneurial capital. International Journal of Manpower, 34(8), 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2013). Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of planned behaviour. Applied Economics, 45(6), 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoi, N. H., Tuu, H. H., Olsen, S. O., & Le, A. N.-H. (2023). Patterns of forming entrepreneurial intention: Evidence in Vietnam. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 13(2), 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, I. M. (1979). Perception, opportunity, and profit. Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S., Palmer, C., Kailer, N., Kallinger, F. L., & Spitzer, J. (2019). Digital entrepreneurship: A research agenda on new business models for the twenty-first century. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(2), 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., & Brazeal, D. V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Dinh, T., Vu, M., & Ayayi, A. (2018). Towards a living lab for promoting the digital entrepreneurship process. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 22(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., Bu, Y., Zhang, Z., & Huang, Y. (2024). Digital entrepreneurship intention and digital entrepreneurship behavior: The mediating role of managing learning and entrepreneurship education. Education + Training, 66(2/3), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. (2009). Development and Cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, J., & Castogiovanni, G. (2015). The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, M., Crowley, C., & Harrison, R. T. (2018). The emancipatory potential of female digital entrepreneurship: Institutional voids in Saudi Arabia. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2018(1), 10255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- MCIT. (2025). The strategy of the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. Available online: https://www.mcit.gov.sa/en/strategy-ministry-communications-and-information-technology (accessed on 10 August 2025).[Green Version]

- Mcmullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A. A., Hassan, S., & Khan, S. J. (2023). Understanding digital entrepreneurial intentions: A capital theory perspective. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(12), 6165–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S., Wright, M., & Feldman, M. (2019). The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Research Policy, 48(8), 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P. N.-D., & Nguyen, H. H. (2024). Examining the role of family in shaping digital entrepreneurial intentions in emerging markets. Sage Open, 14(1), 21582440241239493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomi, M. A., Grabiszewski, K., & AlMoamar, O. (2020). Intention to action: Bridging the gap in youth entrepreneurship. Prince Mohammad Bin Salman College. Available online: https://cdnhub.misk.org.sa/media/t4zpsnea/intention-to-action.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). Social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, & K. H. Vesper (Eds.), The encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 72–90). Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., Bogatyreva, K., Edelman, L. F., & Manolova, T. S. (2022). Moving from intentions to actions in youth entrepreneurship: An institutional perspective. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 12(1), 25–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaridis, I., & Kitsios, F. (2024). Digital entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(2/3), 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussan, F., & Acs, Z. J. (2017). The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B., Fidell, L., & Ullman, J. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 6). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L. P., Pham, L. X., & Bui, T. T. (2021). Personality traits and social entrepreneurial intention: The mediating effect of perceived desirability and perceived feasibility. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 30(1), 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J., Kacmar, K. M., & Busenitz, L. (2012). Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B. (2020). Entrepreneurial alertness, self-efficacy and social entrepreneurship intentions. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 27(3), 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A., Narmaditya, B. S., Saptono, A., Effendi, M. S., Mukhtar, S., & Mohd Shafiai, M. H. (2023). Does digital entrepreneurship education matter for students’ digital entrepreneurial intentions? The mediating role of entrepreneurial alertness. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2221164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, H., Breyer, Y., & Dumay, J. (2019). Digital entrepreneurship: An interdisciplinary structured literature review and research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 148, 119735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 145 | 25.4 |

| Female | 426 | 74.6 |

| Age | ||

| 23 years and less | 441 | 77.2 |

| Between 24 and 33 years | 113 | 19.8 |

| Between 34 and 43 years | 12 | 2.1 |

| 44 years and more | 5 | 0.9 |

| Educational level | ||

| 0 (before university level) | 67 | 11.7 |

| 1st year | 69 | 12.1 |

| 2nd year | 132 | 23.1 |

| 3rd year | 127 | 22.2 |

| 4th year | 151 | 26.4 |

| 5th (Master student) | 8 | 1.4 |

| 6th (Master graduate) | 10 | 1.8 |

| 7th (PhD student) | 5 | 0.9 |

| 8th (PhD holder) | 2 | 0.4 |

| Specialization | ||

| Business administration (all specializations) | 143 | 25.0 |

| Financial economics (all specializations) | 93 | 16.3 |

| Computer sciences (all specializations) | 43 | 7.5 |

| Engineering (all specializations) | 19 | 3.3 |

| Applied Sciences (all specializations) | 29 | 5.1 |

| Social Sciences (all specializations) | 39 | 6.8 |

| Humanities (all specializations) | 40 | 7.0 |

| Others (sharia, languages, sports…) | 165 | 28.9 |

| University | ||

| University in Riyadh city | 470 | 80 |

| University outside Riyadh city | 114 | 20 |

| Variable | Item Codings | Factor Loadings | % Variance | KMO | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital entrepreneurial alertness | DEA1 | 0.767 | 59.876 | 0.933 | 0.925 | 0.937 | 0.599 |

| DEA2 | 0.763 | ||||||

| DEA3 | 0.765 | ||||||

| DEA4 | 0.730 | ||||||

| DEA5 | 0.727 | ||||||

| DEA6 | 0.730 | ||||||

| DEA7 | 0.802 | ||||||

| DEA8 | 0.824 | ||||||

| DEA9 | 0.830 | ||||||

| DEA10 | 0.791 | ||||||

| Perceived desirability | PerDesir1 | 0.827 | 59.948 | 0.869 | 0.865 | 0.899 | 0.600 |

| PerDesir2 | 0.774 | ||||||

| PerDesir3 | 0.838 | ||||||

| PerDesir4 | 0.684 | ||||||

| PerDesir5 | 0.748 | ||||||

| PerDesir6 | 0.765 | ||||||

| Perceived feasibility | PerFeas1 | 0.770 | 63.732 | 0.895 | 0.885 | 0.913 | 0.637 |

| PerFeas2 | 0.818 | ||||||

| PerFeas3 | 0.770 | ||||||

| PerFeas4 | 0.818 | ||||||

| PerFeas5 | 0.780 | ||||||

| PerFeas6 | 0.831 | ||||||

| Digital entrepreneurial intention | DEI1 | 0.813 | 70.155 | 0.828 | 0.893 | 0.922 | 0.702 |

| DEI2 | 0.848 | ||||||

| DEI3 | - | ||||||

| DEI4 | 0.843 | ||||||

| DEI5 | 0.835 | ||||||

| DEI6 | 0.849 | ||||||

| Actual digital entrepreneurial behavior | - |

| Mean | S.D. | Gender | Age | DEA | PD | PF | DEI | ADEB | #Startup Activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.250 | 0.436 | - | |||||||

| Age | 1.270 | 0.539 | −0.005 | - | ||||||

| DEA | 3.787 | 0.757 | −0.087 * | 0.124 ** | 0.770 | |||||

| PD | 3.911 | 0.765 | −0.073 | 0.130 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.775 | ||||

| PF | 3.799 | 0.777 | −0.089 * | 0.090 * | 0.690 ** | 0.566 ** | 0.798 | |||

| DEI | 3.755 | 0.871 | −0.036 | 0.078 | 0.639 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.605 ** | 0.838 | ||

| ADEB | 2.140 | 0.796 | 0.076 | 0.032 | 0.215 ** | 0.111 ** | 0.148 ** | 0.211 ** | - | |

| #Startup Activities | 1.600 | 1.910 | 0.021 | 0.015 | 0.170 ** | 0.020 | 0.121 ** | 0.145 ** | 0.471 ** | - |

| Estimate | S_Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Label | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADEB | <--- | DEI | 0.187 | 0.193 | 0.085 | 2.207 | 0.027 | H1 |

| DEI | <--- | PD | 0.217 | 0.183 | 0.062 | 3.503 | *** | H2a |

| ADEB | <--- | PD | −0.138 | −0.121 | 0.093 | −1.494 | 0.135 | H2b |

| DEI | <--- | PF | 0.413 | 0.374 | 0.074 | 5.593 | *** | H3a |

| ADEB | <--- | PF | −0.025 | −0.023 | 0.109 | −0.226 | 0.821 | H3b |

| PD | <--- | DEA | 0.726 | 0.709 | 0.056 | 13.039 | *** | H4a |

| PF | <--- | DEA | 0.874 | 0.794 | 0.059 | 14.701 | *** | H4b |

| DEI | <--- | DEA | 0.409 | 0.338 | 0.071 | 5.764 | *** | H4c |

| ADEB | <--- | DEA | 0.157 | 0.134 | 0.104 | 1.504 | 0.132 | H4d |

| Hypothesis | From IV | Mediation | To DV | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | Mediation Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5a | DEA | DEI | ADEB | 0.134 | 0.044 | 0.177 * | Full mediation |

| H5b | PD | DEI | ADEB | −0.023 | 0.072 | 0.049 | Full mediation |

| H5c | PF | DEI | ADEB | −0.121 | 0.035 | −0.085 | Full mediation |

| H6a | DEA | PD | DEI | 0.338 *** | 0.154 | 0.492 ** | Partial mediation |

| H6b | DEA | PF | DEI | 0.338 *** | 0.327 ** | 0.666 ** | Partial mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhajri, A.F.; Aloulou, W.J.; Althowaini, N.A. From Entrepreneurial Alertness to Commitment to Digital Startup Activities: A Mediation Model of Perceived Desirability, Feasibility, and Intentions. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110432

Alhajri AF, Aloulou WJ, Althowaini NA. From Entrepreneurial Alertness to Commitment to Digital Startup Activities: A Mediation Model of Perceived Desirability, Feasibility, and Intentions. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(11):432. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110432

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhajri, Abrar F., Wassim J. Aloulou, and Norah A. Althowaini. 2025. "From Entrepreneurial Alertness to Commitment to Digital Startup Activities: A Mediation Model of Perceived Desirability, Feasibility, and Intentions" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 11: 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110432

APA StyleAlhajri, A. F., Aloulou, W. J., & Althowaini, N. A. (2025). From Entrepreneurial Alertness to Commitment to Digital Startup Activities: A Mediation Model of Perceived Desirability, Feasibility, and Intentions. Administrative Sciences, 15(11), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15110432