Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a servant leadership development intervention. A one-group pre-test and post-test experimental design was applied to evaluate servant leadership behavior before and after a servant leadership intervention. A sample of 44 managers was drawn from a construction company in South Africa. The results showed that the servant leadership intervention significantly enhanced servant leadership behavior, particularly in terms of empowerment, stewardship, and forgiveness. Managers who participated in the servant leadership intervention exhibited more servant leadership behavior after the intervention, specifically in terms of empowerment, stewardship, and forgiveness. However, humility, courage, authenticity, standing back, and accountability appeared to remain stable, with no observed changes. The findings highlighted that servant leadership competencies, such as empowerment, stewardship, and forgiveness, could be enhanced by short-term and one-time interventions, whereas servant leadership traits, such as humility, courage, authenticity, standing back, and accountability, may require more continuous and alternative intervention approaches over the long term to improve. The servant leadership intervention evaluated in this study can be used as an effective method to enhance servant leadership behavior and cultivate servant leadership cultures within organizations. In return, organizations can benefit from the favorable individual and organizational outcomes that servant leadership offers. As one of the preliminary validation studies of a servant leadership intervention, this study makes a theoretical contribution to the existing body of knowledge on servant leadership by presenting empirical evidence that servant leadership behavior can be cultivated through targeted interventions. The findings endorse the theoretical premise that servant leadership is not exclusively a trait-based theory, but that it can be fostered through experiential and organizational development initiatives.

1. Introduction

Leadership plays a fundamental role in organizational performance and sustainability. Several frameworks highlight leadership as a key factor to sustain a high-performing organization (Blanchard, 2010; De Waal, 2007; Owen et al., 2001). Leaders not only direct organizations strategically and operationally but also influence employee behavior, such as work engagement, which ultimately affects levels of corporate citizenship behavior (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Saks, 2006; Sulea et al., 2012), productivity (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008; Harter et al., 2002; Hayward, 2010; Shuck, 2011; Simpson, 2009; Solomon & Sridevi, 2010), performance (Bakker, 2011; Bakker et al., 2008, 2014; Baron, 2013; Demerouti et al., 2015; Hayward, 2010; Kovjanic et al., 2013; Lorente et al., 2014; Shuck, 2011; Simpson, 2009; Yalabik et al., 2013), profitability (Shuck, 2011; Simpson, 2009; Solomon & Sridevi, 2010), safety behavior (Shuck, 2011; Solomon & Sridevi, 2010), and customer satisfaction (Bakker et al., 2011; Baron, 2013; Hayward, 2010; Simpson, 2009; Solomon & Sridevi, 2010).

Unfortunately, leadership development remains a significant challenge and priority in most organizations (Mallon et al., 2017). The decline in leadership trust (Development Dimensions International, 2025), the changing needs for different types of leadership capabilities due to technological advancements (Deloitte, 2025), and the insufficient leadership capacity in organizations continue to be global human capital challenges in organizations (SHRM, 2025; Mallon et al., 2017; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015). Even though leadership development initiatives claim the most significant percentage of learning and development budgets (O’Leonard, 2014), the leadership capability gap appears to widen over the years (Mallon et al., 2017). Hence, the need for more effective leadership development programs is evident.

In the construction industry, leadership plays a critical role in sustaining operational performance. The construction industry is a labor-intensive industry that formally employs approximately 8%, and informally about 17% of South Africans’ workforce, of which 70% are low-, semi-, and unskilled employees (Construction Industry Development Board, 2015). These figures emphasize the need for a people-oriented leadership approach in this industry to ensure sustainable operational performance. However, the construction industry faces challenges, including increased labor unrest, poor operational performance, low productivity, and health and safety issues (Naidoo et al., 2016). All these challenges can be linked to leadership either directly or indirectly. Leadership seems to influence productivity (Butt et al., 2014), performance (Kuria et al., 2016; Liphadzi et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2010), safety behavior (Skeepers & Mbohwa, 2015) and work engagement levels (Babcock-Roberson & Strickland, 2010; Breevaart et al., 2015; Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012; Ghadi et al., 2013; Mendes & Stander, 2011; Penger & Cerne, 2014; Schaufeli, 2015). Effective leadership development, therefore, plays a fundamental role in sustaining operational performance in the construction industry.

A leadership approach that could work well in the construction industry is servant leadership, because it focuses primarily on people, which is ideal in a labor-intensive industry. Servant leadership is a comprehensive leadership approach that focuses first on serving and empowering employees to ultimately achieve a higher purpose vision to the benefit of multiple stakeholders (Van Dierendonck, 2011; Coetzer, 2019). These multiple stakeholders include customers, employees, suppliers, shareholders, society, and the environment. Servant leadership is characterized by courage, authenticity, accountability (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011), altruism (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006), integrity (Page & Wong, 2000), humility, compassion (Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014), and listening (Spears, 2010). Servant leaders set compelling visions (Hale & Fields, 2007), build trustful relationships (Liden et al., 2008), empower employees (Dennis & Bocarnea, 2005), and produce a solid return-on-investment as good stewards of a company’s resources and assets (Russell & Stone, 2002).

Limited experiential-type research is, however, available on the application of servant leadership. Previous research on servant leadership has primarily focused on defining the concept, measuring its impact, and reporting the results of servant leadership. However, research on servant leadership interventions is scarce. The need to evaluate the application of servant leadership, using experiential or longitudinal study designs, is called for by several authors (Chen et al., 2015; De Clercq et al., 2014; Mehta & Pillay, 2011).

Servant leadership is different, but also similar, to other leadership theories. For example, servant leadership includes dimensions of transformational leadership (Stone et al., 2004), authentic leadership, level 5 leadership (Van Dierendonck, 2011), enterprise leadership (Liden et al., 2014), situational leadership (Blanchard & Hodges, 2008), spiritual leadership (Sendjaya et al., 2008), charismatic leadership, and leader-member exchange (Hanse et al., 2016). However, servant leadership is different from these leadership theories in the sense that it focuses on people first (Stone et al., 2004) and aims to achieve a higher purpose vision, beyond self-interest (Barbuto et al., 2014), to the benefit of multiple stakeholders (Coetzer, 2019). Servant leadership also encompasses additional leadership attributes that are not included in the leadership theories. Evaluating the effectiveness of servant leadership interventions could provide practitioners with the means to effectively develop servant leaders within organizations. In return, organizations can benefit from the favorable outcomes that servant leadership produces.

Research Objectives

The primary objective of this study was to introduce a servant leadership intervention in the construction industry and to assess its effectiveness at the within-subject level. The specific objectives of this study were to evaluate the effectiveness of a servant leadership intervention to enhance (a) empowerment, (b) standing back, (c) forgiveness, (d) courage, (e) authenticity, (f) humility, and (g) stewardship behavior when considering individual-level effectiveness of the intervention in the construction industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Defining Servant Leadership

The original teachings on servant leadership were introduced by Jesus Christ more than 2000 years ago and can be found in the Bible (Sendjaya, 2015). For example, Jesus taught His disciples in Luke 22: 26-26 (New International Version) that “the kings of the gentiles lord it over them and those who exercise authority over them call themselves benefactors. But you are not to be like that. Instead, the greatest among you should be like the youngest, and the one who rules like the one who serves.”

In the late 1970s, Robert Greenleaf applied the principles and practices of servant leadership in the business and education sectors. Greenleaf (1998) described servant leadership as a leadership practice that starts with a willingness to serve that flows into a motivation to lead others. Today, servant leadership has been researched internationally, and its impact on individuals and organizations has been reported in several scientific journals (Eva et al., 2019).

In general, servant leadership can be defined as a comprehensive leadership practice that starts with an intent to serve (Greenleaf, 1998), that flows into a set of principles and practices to empower people (Van Dierendonck, 2011), to build sustainable organizations, and to create humane societies (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006). Van Dierendonck and Nuijten (2011) characterize servant leadership by empowerment, standing back, accountability, forgiveness, courage, authenticity, humility, and stewardship. Other researchers included additional servant leadership traits such as compassion (Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014), integrity (Ehrhart, 2004; Liden et al., 2008; Page & Wong, 2000; Wong & Davey, 2007), listening (Spears, 2010), building relationships (Dennis & Bocarnea, 2005; Ehrhart, 2004; Page & Wong, 2000; Sendjaya et al., 2008; Wong & Davey, 2007), and setting a compelling vision (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006; Dennis & Bocarnea, 2005; Ehrhart, 2004; Hale & Fields, 2007; Laub, 1999; Page & Wong, 2000; Sendjaya et al., 2008). In this study, the eight servant leadership characteristics of Van Dierendonck and Nuijten (2011) were used to evaluate servant leadership. These characteristics are described in more detail below.

The first servant leader attribute, namely empowerment, refers to the consistent effort to grow and develop individuals personally and professionally (Berger, 2014; Carter & Baghurst, 2013; Crippen, 2005; Hu & Liden, 2011; Kincaid, 2012; Mehta & Pillay, 2011; Spears, 2010; Van Dierendonck, 2011) and to transfer accountability to individuals to make them more autonomous (Bobbio et al., 2012). Empowerment also includes the alignment and activation of individual talent (Bobbio et al., 2012; Flint & Grayce, 2013; Humphreys, 2005; Sendjaya & Sarros, 2002; Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014), creating an effective work environment in which people can flourish (Mittal & Dorfman, 2012), and promoting the confidence, wellness, and independent behavior of individuals (Mittal & Dorfman, 2012; Rai & Prakash, 2012; Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011).

The second servant leader attribute is standing back and can be described as putting the interests of others above one’s own, helping others perform better, and giving credit to others once a task has been completed (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). Collins (2001) describes this behavior as taking responsibility when problems occur and giving credit to others when a task is completed.

The third servant leader attribute, namely accountability, can be defined as setting clear objectives for oneself and others, being responsible (Van Dierendonck, 2011), and holding others accountable while continuously monitoring their performance (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). The fourth servant leader attribute is forgiveness. Forgiveness is the ability to forgive others for past mistakes without holding a grudge (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011).

Courage is a fifth servant leader trait and can be described as the willingness to stand up for what is right, despite hardships, and to take calculated risks for the benefit of others (Russell & Stone, 2002; Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). Another servant leader attribute is authenticity, which can be defined as showing genuine intentions and motivations to others (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) without hiding one’s true self (Pekerti & Sendjaya, 2010). Authenticity also includes having good ethical principles (Russell & Stone, 2002), behaving consistently, acknowledging one’s development areas, and learning from criticism (Sendjaya & Cooper, 2011).

Humility is a seventh servant leadership characteristic, defined as being modest and self-aware (De Sousa & Van Dierendonck, 2014; Klemich & Klemich, 2020; Patterson, 2003), with a focus on personal development (Van Dierendonck, 2011) and a proper perspective on one’s strengths (Patterson, 2003). Blanchard and Hodges (2008) describe humility as not thinking less of oneself, but thinking of oneself less.

The eighth servant leadership characteristic is stewardship. Stewardship can be defined as being a caretaker of the belongings or interests of others (Flint & Grayce, 2013; Melchar & Bosco, 2010; Ozyilmaz & Cicek, 2015; Searle & Barbuto, 2011; Sendjaya & Sarros, 2002; Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014) while protecting the common good in organizations and society (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006; Melchar & Bosco, 2010; Ozyilmaz & Cicek, 2015; Sun & Wang, 2009; Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014).

2.2. The Outcomes of Servant Leadership

2.2.1. Individual Outcomes

Previous studies have shown that servant leadership has a positive influence on work engagement levels (Carter & Baghurst, 2013; De Clercq et al., 2014). In one study, goal congruence and social interaction moderated the relationship between servant leadership and work engagement (De Clercq et al., 2014). In another study, this relationship was found to be mediated by organizational identification and psychological empowerment (De Sousa & Van Dierendonck, 2014).

Servant leadership has also been associated with increased individual levels of organizational citizenship behavior (Bobbio et al., 2012; Newman et al., 2015; Ozyilmaz & Cicek, 2015; Panaccio et al., 2014; Walumbwa et al., 2010). The relationship between servant leadership and organizational citizenship behavior is mediated by leader-member exchange (Hsiao et al., 2015; Newman et al., 2015), psychological capital (Wu et al., 2013), psychological contract (Panaccio et al., 2014), commitment to supervisor, self-efficacy, procedural justice climate, and service climate (Walumbwa et al., 2010).

Innovative behavior and individual trust are furthermore positively influenced by servant leadership. For example, Panaccio et al. (2014) reported that servant leadership enhanced innovative behavior, which was mediated by psychological contract. Other researchers also reported that servant leadership increases creative behavior (Liden et al., 2014; Neubert et al., 2008). Interpersonal trust (Chatbury et al., 2011), employee trust (Chinomona et al., 2013), affective trust (Miao et al., 2014), and organizational trust (Jones, 2012) were, in addition, all increased by servant leadership.

Other individual outcomes linked to servant leadership include higher job satisfaction (Chung et al., 2010; Jones, 2012; Mehta & Pillay, 2011; Ozyilmaz & Cicek, 2015; Sturm, 2009), organizational commitment (Bobbio et al., 2012; Chinomona et al., 2013), self-efficacy (Chen et al., 2015; Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011), person-job fit (Carter & Baghurst, 2013), and communication with leaders (Hanse et al., 2016; Newman et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2013). Servant leader also seems to lower burnout levels (Babakus et al., 2011; Bobbio et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2015) and turnover intention levels (Babakus et al., 2011; Hunter et al., 2013; Jaramillo et al., 2009b; Kashyap & Rangnekar, 2016) of employees.

2.2.2. Organizational Outcomes

Servant leadership has been shown to produce positive organizational outcomes such as higher customer service levels and better sales performance. In terms of customer service, various studies reported a positive relationship between servant leadership and customer service performance (Chen et al., 2015), service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior, customer value co-creation (Hsiao et al., 2015), customer trust in the firm, customer satisfaction (Hwang et al., 2014), customer orientation (Jaramillo et al., 2009a), customer serving behavior (Liden et al., 2014), and value-enhancing behavior (Schwepker & Schultz, 2015). A negative relationship was also found between servant leadership and customer turnover (Jones, 2012). In terms of sales performance, servant leadership directly influences sales performance positively (Jaramillo et al., 2015; Schwepker & Schultz, 2015) or indirectly via customer orientation (Jaramillo et al., 2009a) and a serving culture (Liden et al., 2014).

Other organizational benefits of servant leadership include enhanced levels of group identification (Chen et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012), group organizational citizenship behavior (Bakar & McCann, 2015; Hu & Liden, 2011), serving culture (Liden et al., 2014), serving climate (Walumbwa et al., 2010), and procedural justice (Chung et al., 2010; Walumbwa et al., 2010).

The literature synthesis by Eva et al. (2019) summarizes the outcomes of servant leadership in three broad categories: behavioral outcomes, attitudinal outcomes, leader-related outcomes, and performance outcomes. In terms of behavioral outcomes, servant leadership was found to have a positive influence on employee collaboration, organizational citizenship behavior, helping behavior, team effectiveness, and voice behavior, and a negative impact on employee deviance. Regarding attitudinal outcomes, servant leadership positively influenced work engagement, work–life balance, employee satisfaction, thriving, psychological well-being, empathy, volunteer and service motivation, person-environment fit, and identification, while negatively influencing employee turnover intention, cynicism, and work-family conflict. The leader-related outcomes that servant leadership positively influenced were trust in the leader, perceived leader effectiveness, integrity, and leader-member exchange. Furthermore, the literature synthesis by Eva et al. (2019) showed that servant leadership increases employee performance, team performance, organizational performance, innovative-related performance, customer-oriented performance, group social capital, knowledge sharing, service quality, and team efficacy.

2.3. Servant Leadership Interventions

Different types of servant leadership interventions are available. The Servant Leadership Institute, for example, offers a variety of servant leadership interventions such as workshops, coaching programs, webinars, and conferences. Their introductory course is a three-day workshop that focuses on defining servant leadership, its importance, the characteristics of servant leadership, the relationship between personal and organizational values, and the importance of business morale and culture (The Servant Leadership Institute, 2017a). Another workshop offered is a six-hour workshop that focuses on practices to enhance team effectiveness, resolve conflict, facilitate difficult conversations, and understand the role of human resources and formal leadership (The Servant Leadership Institute, 2017b). A third workshop provided by The Servant Leadership Institute (2017c) is three hours in duration and focuses on the definition of servant leadership, the difference between servant leadership and other leadership theories, the benefits of servant leadership, and the methods to become a servant leader. The Servant Leadership Institute (2017d) also offers a four- to twelve-month coaching program that aims to maximize personal and professional growth as a servant leader.

The Greenleaf Centre for Servant Leadership is another institution that offers different types of servant leadership interventions, such as short courses and conferences. The servant leadership course at this institution covers the fundamentals of servant leadership through four learning modules: (1) introduction to servant leadership, (2) characteristics and behaviors of servant leaders, (3) servant leader institutions and organizations, and (4) the case for servant leadership (The Greenleaf Centre for Servant Leadership, 2025). The content is delivered across four contact sessions, which include lectures, group discussions, and readings.

Another servant leadership intervention available is a short course developed by Blanchard et al. (2014), named the Lead Like Jesus encounter. This one-day course focuses on the heart, head, hands, and habits of a servant leader. The heart section of the course describes four heart types, namely pride, fear, humility, and God-grounded confidence. The head section explores the two parts of leadership, namely direction and implementation. It also emphasizes the importance of personal values. The hands section of the course describes four development stages of a servant leader, namely novice, apprentice, journeyman, and master. The habits section explains four habits of a servant leader, namely (1) accepting and abiding in God’s unconditional love, (2) experiencing solitude, (3) practicing prayer, (4) applying scripture, and (5) maintaining supportive relationships.

Even though servant leadership interventions are available in the market, few of them have been scientifically evaluated to determine their effectiveness in enhancing servant leadership behavior. Another problem with the abovementioned interventions is that none of them utilize blended learning methods, and few of them include experiential exercises and assessments. Lombardo and Eichinger (2006) suggest that 10% of leadership development programs should consist of theoretical training, 70% of experiential training, and 20% of personal training. Other researchers agree and suggest that leadership development programs should consist of classroom training, group activities, individual projects, mentorship (Ingraham & Getha-Taylor, 2004), self-reflection (Nesbit, 2012), coaching (Shuck & Herd, 2012), social networks (Gagnon & Collinson, 2014), storytelling (Janson, 2008), 360 surveys, individual job assignments (McCauley et al., 1998), and experiential learning (Bolden, 2010; Johnstal, 2013) such as workplace assignments, special projects, on-the-job training, job rotation, refresher training, leadership forums (Lancaster & Di Milia, 2015), and workplace case studies (Lee, 2010). A third challenge of the available interventions is the short duration of the workshops or courses. Behavioral change often occurs over a longer period of time.

It was thus decided to develop a new servant leadership intervention in this research using current servant leadership literature and multi-learning methods. The design of the intervention was based upon several learning theories, including experiential learning (Kolb, 2014; Morris, 2020), micro-learning (Hug, 2005), neuro-learning (Leaf, 2013), gamification (Landers, 2014), case studies (Nohria, 2021), self-reflection (Riley-Douchet & Wilson, 1997), and the 70-20-10 principles (Lombardo & Eichinger, 2006). The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the designed intervention to enhance servant leadership behavior. A validated servant leadership intervention could offer practitioners an effective way to cultivate servant leaders in the workplace, and in return, could offer organizations the benefits that servant leadership produces. This study also addressed the research need for experiential-type studies to evaluate the effective application of servant leadership (Chen et al., 2015; De Clercq et al., 2014; Mehta & Pillay, 2011).

The following hypotheses were made:

H1.

The servant leadership intervention significantly increases the levels of empowerment at the within-subject level.

H2.

The servant leadership intervention significantly increases the levels of standing back at the within-subject level.

H3.

The servant leadership intervention significantly increases the levels of forgiveness at the within-subject level.

H4.

The servant leadership intervention significantly increases the levels of courage at the within-subject level.

H5.

The servant leadership intervention significantly increases the levels of authenticity at the within-subject level.

H6.

The servant leadership intervention significantly increases the levels of humility at the within-subject level.

H7.

The servant leadership intervention significantly increases the levels of stewardship at the within-subject level.

H8.

The servant leadership intervention significantly increases the levels of accountability at the within-subject level.

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Approach

A one-group pre-test, post-test experimental design was used in this study (i.e., repeated measures analysis of variance). For this repeated measures design, the within-subject changes were evaluated, with each individual serving as their own control within an experiential group. Thus, no external control group was utilized. Data was collected using a quantitative cross-sectional survey before and after a leadership development program. Descriptive and inferential statistical methods were used to analyze the data.

3.2. Sample Framework

A non-probability sample of 44 managers was drawn from a construction company in South Africa. The 44 managers participated in a servant leadership development program and completed the Servant Leadership Survey (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011) both before and after the leadership program. Managers evaluated their own servant leadership behavior.

The majority of the sample consisted of men with a home language of either Afrikaans or English, and they were between the ages of 26 and 45 years. The race distribution of the sample was 73% White, 23% Black, 2% Indian, and 2% Coloured. Most participants held a 3-year Diploma or Bachelor’s Degree and had 3 to 10 years of work experience. The sample consisted of 9 senior managers (21%), 20 middle managers (46%), 9 junior managers (21%), 3 senior supervisors (7%), and 3 junior supervisors (7%).

3.3. Development and Structure of the Intervention

The servant leadership framework of Coetzer et al. (2017) served as the basis for developing the intervention. This framework consisted of four functions of a servant leader, namely (1) to set, translate, and execute a higher purpose vision, (2) to become a role model and ambassador, (3) to align, care, and grow talent, and (4) to monitor and improve continuously. A summary of this framework is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Functions, Objectives, Characteristics, and Competencies of a Servant Leader (Coetzer et al., 2017).

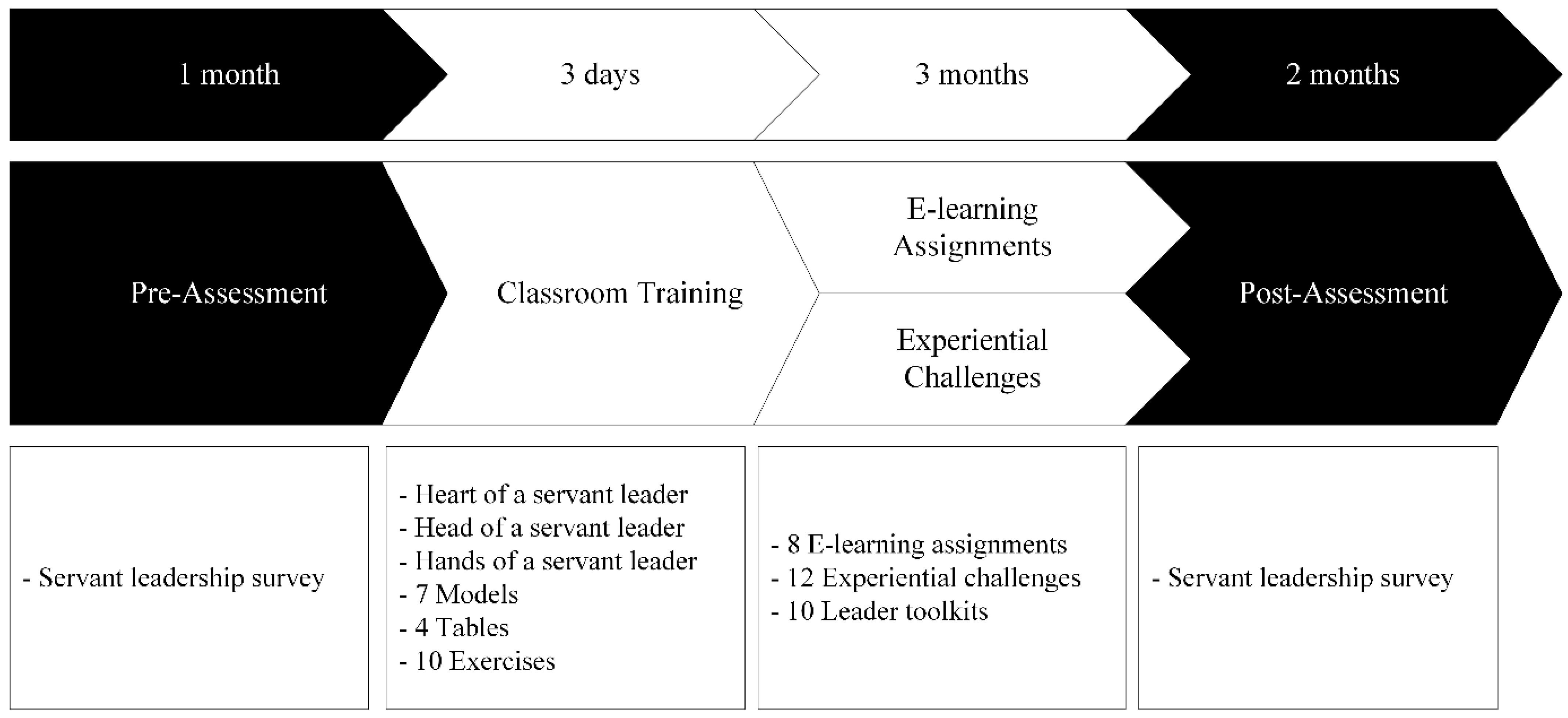

The types of learning methods included in this intervention were personal assessments, electronic learning, classroom training, gamification, experiential learning, application toolkits, and principles of neuro-learning. Coaching was initially included but was later removed due to insufficient resources. The learning program consisted of pre- and post-assessments, a three-day classroom training session, electronic assessments, and experiential assignments. The pre-assessments were conducted one month prior to the classroom training session, and the post-assessments were administered two months after completing the classroom training, electronic learning assignments, and experiential exercises. The pre- and post-tests assessed servant leadership behavior.

The classroom training was designed to be highly interactive, incorporating several individual and group exercises, as well as elements of gamification. The classroom session content was divided into three modules. The first module focused on the heart of a servant leader. This module explained the purpose of a leader, the difference between a self-serving and a servant leader, the definition of servant leadership, the dimensions of servant leadership, the different types of leadership intent, and the role of personal and organizational values in servant leadership. The second module focused on the head of servant leadership, which referred to strategic leadership. In this module, the first two functions of a servant leader were introduced, and the objectives, characteristics, and competencies of these functions were explained. The difference between strategic and operational servant leadership was also discussed. The third module focused on the hands of a servant leader. In this module, the third and fourth functions of a servant leader were introduced, and the objectives, characteristics, and competencies of these functions were explained. This module also introduced the talent wheel of servant leadership and described a servant leadership model. A general framework to implement servant leadership was also discussed.

The electronic exercises consisted of relevant reading material, videos, and questionnaires. The experiential challenges included several workplace assignments, individual assignments, mentorship sessions, video sessions, and case studies. Application toolkits were also designed to assist leaders in applying the knowledge gained during the classroom session in the workplace. The structure of the servant leadership intervention is provided in Figure 1. A full description of the intervention is also provided in Appendix A.

Figure 1.

The Structure of the Servant Leadership Intervention.

3.4. Measuring Battery

The Servant Leadership Survey of (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011) was used to collect data before and after the intervention. This survey consists of 30 items and measures eight servant leadership characteristics, namely (1) standing back, (2) forgiveness, (3) courage, (4) empowerment, (5) accountability, (6) authenticity, (7) humility, and (8) stewardship. A six-point Likert-type response scale is used in this survey, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Van Dierendonck and Nuijten (2011) reported Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients of 0.76 for standing back, 0.72 for forgiveness, 0.69 for courage, 0.89 for empowerment, 0.81 for accountability, 0.82 for authenticity, 0.91 for humility, and 0.74 for stewardship. The original version of the Servant Leadership Survey was adopted to enable participants to evaluate their own leadership behavior before and after the leadership development program.

3.5. Data Analysis

The central tendency and data distribution were analyzed using mean, median, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis (Collis & Hussey, 2009). Data normality was assessed by calculating the skewness and kurtosis scores, then dividing them by their standard errors, and by conducting Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality tests (Pallant, 2010). The reliability of the instrument, in terms of internal consistency, was, in addition, evaluated by computing the combined Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient value of the items. The SPSS statistical software, version 30.0.0.0 (171), was utilized to conduct the descriptive analysis.

A repeated measures t-test was used to evaluate the difference between pre- and post-test results. According to Collis and Hussey (2009), a repeated measures t-test is an effective method to compare two data sets of a single group. In this study, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used because the data were not normally distributed. The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test is the non-parametric alternative to a paired-sample t-test (Pallant, 2010). The SPSS statistical software was utilized to conduct the inferential statistical analysis. Furthermore, the repeated measures t-test was explicitly used for this study due to its benefits in considering individual-level differences that may impact how servant leadership manifests. With this in mind, each person acted as their own control, where natural variation (e.g., personality or preferences) within individuals is controlled for (Collis & Hussey, 2009; Maxwell & Delaney, 2004).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Results

The descriptive statistics indicated that the data were not normally distributed. After dividing the skewness and kurtosis scores by their standard errors, the results showed values larger than 1.96 for accountability, courage, stewardship, and forgiveness. This exceeded the general “rule of thumb” value of normally distributed data (Rose et al., 2015). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test was significant for all variables (p < 0.05), which confirmed non-normality (Pallant, 2010). A summary of the descriptive statistical results is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Servant Leadership.

4.2. Inferential Statistical Results

The first step in the inferential statistical analysis was to evaluate the reliability of the measuring instrument. The reliability coefficient of the Servant Leadership Survey was acceptable and showed a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.78. This indicated that the Servant Leadership Survey had acceptable values of internal consistency.

The second step in the inferential statistical analysis was to compare the pre- and post-test results of the sample to determine whether servant leadership behavior increased after the sample participated in the intervention. A Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test showed a significant increase in the total score for servant leadership behavior (z = −3.04, p = 0.002), with a medium effect size (r = 0.32), following the sample’s participation in the servant leadership development program. The median score of the total score for servant leadership behavior increased from Md = 146 (pre-test) to Md = 149 (post-test). A total of 30 participants demonstrated higher post-test scores (M = 22.15), whereas 11 participants exhibited higher pre-test scores (M = 17.86), indicating that improvements were more frequent and of greater magnitude in overall servant leadership.

The Wilcoxon Signed Rank Tests results of the sub-scales however revealed a significant increase in only three servant leadership behaviors after the intervention, namely empowerment (z = −2.47, p = 0.014), stewardship (z = −3.29, p = 0.001), and forgiveness (z = −3.98, p = 0.000). Empowerment changed with a small effect (r = 0.26) and stewardship and forgiveness with a medium effect (r = 0.35, r = 0.42). The median scores of these variables increased from Md = 35.5 (pre-test) to Md = 36 (post-test) for empowerment, Md = 15 (pre-test) to Md = 16 (post-test) for stewardship, and Md = 12 (pre-test) to Md = 15 (post-test) for forgiveness. Most participants showed improved scores after the intervention (positive rank) in empowerment, with 22 increases (M = 21.11), compared to 13 decreases (M = 12.73). Similar trends were observed for stewardship (n = 24 increases, M = 18.00; n = 8 decreases, M = 12.00) and forgiveness (n = 33 increases, M = 20.41; n = 6 decreases, M = 17.75). The results validated hypotheses 1, 3, and 7 of the study, which anticipated that the servant leadership intervention would improve empowerment, forgiveness, and stewardship behavior.

The Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test results for standing back, accountability, courage, authenticity, and humility were insignificant, which indicated that these behaviors did not increase after the leadership program. The results therefore rejected hypotheses 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8 as no significant improvement in these behaviors was found after the intervention. A summary of the results is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Servant Leadership Results Pre- and Post the Intervention.

5. Discussion

The main objective of this research was to develop and evaluate a servant leadership intervention. Overall, the results indicated that servant leadership behavior increased following managers’ participation in the servant leadership development intervention. Further analysis revealed that the specific servant leadership behaviors of empowerment (H1), stewardship (H7), and forgiveness (H3) increased significantly after completing the servant leadership intervention. The remaining servant leadership behaviors, standing back (H2), courage (H4), authenticity (H5), humility (H6), and accountability (H8) did not show a significant increase after managers completed the servant leadership development program. Based on this result, a more nuanced approach is likely required to cultivate behavioral change. For example, using longer intervals between the intervention and assessment can help evaluate behavioral change. Alternatively, a broader program that includes ongoing development interventions for these behaviors could be beneficial.

5.1. Empowerment, Stewardship, and Forgiveness

The first significant finding of the study was that the servant leadership intervention increased empowerment behavior, supporting hypothesis 1. Empowerment is the ability to activate individual talent (Bobbio et al., 2012; Flint & Grayce, 2013; Humphreys, 2005; Sendjaya & Sarros, 2002; Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014), to make individuals more independent (Liden et al., 2008; Spears, 2010) by means of continuous development (Berger, 2014; Carter & Baghurst, 2013; Crippen, 2005; Hu & Liden, 2011; Kincaid, 2012; Mehta & Pillay, 2011; Spears, 2010; Van Dierendonck, 2011), and by creating an effective working climate and culture (Mittal & Dorfman, 2012) to ultimately transfer responsibility and authority to individuals (Bobbio et al., 2012). The servant leadership intervention used in this study was therefore successful in enhancing the empowerment behavior of managers. In other words, managers who participated in the servant leadership program were more able to (a) activate the talents of direct reports, (b) create effective working climates and cultures, (c) develop and support direct reports, and (e) transfer accountability and authority to direct reports after completing the development program. The first finding aligns with previous literature. For example, Van Dierendonck (2011) also believes that servant leadership training can help leaders activate prosocial values and align behavior with developmental intentions. Carter and Baghurst (2013) furthermore suggest that empowerment behaviors can be developed by fostering a growth mindset and challenging beliefs about power and control.

The second significant finding was that forgiveness behaviors increased after participation in the servant leadership development program, supporting hypothesis 3. Forgiveness is the practice of forgiving others for past mistakes without holding a grudge (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). The managers who participated in the servant leadership development program were thus more able to forgive others for past mistakes and were more able to let go of grudges towards others after completing the program. The ability to allow employees to take risks and make mistakes is a key component of building a high-performing organization (De Waal, 2007). Hence, managers who enable direct reports to learn from mistakes and forgive them without holding grudges will cultivate an organizational climate and culture of openness, trust, innovation, and support that will help build and sustain a high-performing organization.

The third and final significant finding was that stewardship behavior was increased by the intervention, supporting hypothesis 7. Stewardship is the ability to take accountability (Hwang et al., 2014; Sousa & Van Dierendonck, 2017) for the best interests of employees, organizations, and the society (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006; Melchar & Bosco, 2010; Ozyilmaz & Cicek, 2015; Sun & Wang, 2009; Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014), with a mental perspective of being a caretaker in life (and not an owner in life) (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006; Flint & Grayce, 2013; Melchar & Bosco, 2010; Ozyilmaz & Cicek, 2015; Searle & Barbuto, 2011; Sendjaya & Sarros, 2002; Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014) to ultimately produce a constructive legacy (Savage-Austin & Honeycutt, 2011) in people, organizations, and the society. The development program in this research study was therefore successful in transforming individuals into caretakers who take accountability for the interests of others and leave a positive legacy in people, organizations, and society.

5.2. Standing Back, Courage, Authenticity, Humility, and Accountability

The study found insignificant results for any improvement in standing back, courage, authenticity, humility, and accountability behaviors after the intervention. Hypotheses 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8 were thus rejected. Standing back means prioritizing others’ interests, recognizing their contributions, and helping employees become more effective (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). Potential explanations for this observation, within the scope of the study, include that these behaviors might be seen as a weakness by others, and leaders may then fear the judgment of others. Particularly within hierarchical environments, such as the construction industry, Schweiger et al. (2020) elucidate that leaders are often expected to be visible, decisive, and central to the delivery of performance. These authors further suggest that such perspectives may lead to certain assumptions about the expected style of leadership in these environments (Schweiger et al., 2020). Consequently, leaders might face some challenges when trying to adopt standing back behaviors in such situations that view effective leadership in a different way.

Another potential reason for the insignificant results is that certain traits, such as courage and humility, may require more time to mature. Courage is defined as the readiness to stand for justice and risk oneself to the benefit of others, despite adversity (Russell & Stone, 2002; Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). Humility is seen as being modest (De Sousa & Van Dierendonck, 2014; Patterson, 2003), focused on others (Blanchard & Hodges, 2008), and having an accurate view of one’s strengths (Patterson, 2003). Shifting from prideful to humble behavior, and from fearful to courageous behavior, may require more in-depth life experiences, intervention, or even hardships to change. Prideful and fearful behaviors are often rooted in deep neurostructural patterns, linked to past life voids and wounds (Klemich & Klemich, 2020), which may require longer and more complex change processes or alternative intervention approaches, such as coaching or cognitive behavioral therapy, to change.

Authenticity involves being truthful, consistent, and demonstrating high ethical standards (Pekerti & Sendjaya, 2010; Russell & Stone, 2002). It also includes self-awareness of personal weaknesses and learning from mistakes (Sendjaya & Cooper, 2011). The lack of observed change in this leadership behavior may be because it is difficult for individuals to be genuinely authentic at work. Research by Liu et al. (2015) suggests that social and organizational expectations can limit authenticity, with leaders only revealing parts of themselves. Additionally, developing authenticity usually takes time. Ilies et al. (2005) explain that authenticity usually evolves through continuous self-reflection, feedback, and experience. Longer-term interventions may be necessary to achieve more meaningful and sustainable growth in authenticity.

Overall, it appears that servant leadership competencies such as empowerment, stewardship, and forgiveness could be improved through shorter-term and one-time interventions, whereas behaviors such as humility, standing back, authenticity, accountability, and courage may require more persistent interventions over the long term to improve.

5.3. Strengths and Limitations

Although this study makes essential contributions to the literature on servant leadership, it acknowledges certain limitations. This research intended to investigate changes in leadership behaviors at the within-person level and therefore did not include an external control group. Hence, it was not possible to control for any external factors that could have influenced servant leadership behavior, other than the intervention and individual-level natural factors, such as personality. A control group could have strengthened the causal validity of the findings. This study utilized self-report measures, with managers evaluating their own servant leadership behavior. It was thus possible that employees could have overestimated or underestimated their own scores on servant leadership behavior, a general limitation of self-assessments (Dunning et al., 2004). Social desirability could have also influenced managers’ responses, causing them to either overrate positive behaviors or underrate negative behaviors to appear socially acceptable rather than being truthful. A fourth limitation is that this study was conducted within the construction industry. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to other sectors. A final limitation of the study was its small sample size. A larger sample size could have produced more research insights.

5.4. Implications for Management

The servant leadership intervention presented in this research study can be utilized to enhance servant leadership behavior within organizations. Practitioners can use the servant leadership development intervention to train servant leadership, transform leaders into servant leaders, and cultivate a servant leadership culture within an organization, particularly in terms of empowerment, stewardship, and forgiveness. The servant leadership intervention can also be incorporated within talent management and learning and development practices to enhance servant leadership behavior in companies. In return, organizations can benefit from the positive outcomes that servant leadership produces.

Notably, the results of this research indicate that the servant leadership intervention had positive implications for increasing servant leadership behaviors such as empowerment, stewardship, and forgiveness. However, a more nuanced approach may be required for the development of other servant leadership behaviors such as humility, courage, standing back, authenticity, and accountability. Learning practitioners may consider including coaching or cognitive behavioral interventions (Richardson & Rothstein, 2008) to cultivate such behaviors. It is further recommended that learning practitioners consider continuous and longer-term interventions, as certain servant leadership behaviors may require consistent intervention and could take longer to mature.

5.5. Future Research Needs

The first research need is to evaluate the effectiveness of the servant leadership intervention used in this study across multiple groups, companies, industries, and countries. This could validate the effectiveness of the intervention in different contexts. Another research need is to assess various learning methods for developing servant leaders. This would provide researchers and practitioners with a set of best practices for developing servant leaders. A third research need is to determine the impact of servant leadership interventions on individual and organizational outcomes. This would provide substantial evidence of the return on investment that servant leadership interventions produce. Another future consideration could be to utilize 360-degree assessments in evaluating servant leadership behavior. This could bridge the limit of socially desirable responses in self-evaluations. A final research need is to study the transformational process of becoming a servant leader using longitudinal research designs. This would help researchers and practitioners to understand the development process individuals experience to become a servant leader.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that the servant leadership intervention significantly enhanced servant leadership behavior, particularly in terms of empowerment, stewardship, and forgiveness. Managers who participated in the servant leadership intervention exhibited more servant leadership behavior, as measured by empowerment, stewardship, and forgiveness, following the completion of the intervention. The results also revealed that the intervention did not improve servant leadership traits such as humility, standing back, authenticity, accountability, and courage. The study highlighted that once-off interventions may be effective in enhancing servant leadership competencies, while more continuous, persistent, and personal interventions may be required to enhance servant leadership behaviors that require deeper self-reflection and time to mature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.C., M.B. and M.G.; methodology, M.F.C., M.B. and M.G.; software, M.F.C. and M.G.; validation, M.F.C., M.B. and M.G.; formal analysis, M.F.C.; investigation, M.F.C.; resources, M.F.C. and M.G.; data curation, M.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.C.; writing—review and editing, M.B. and M.G.; visualization, M.F.C.; supervision, M.B. and M.G.; project administration, M.F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT-PROJECT PROPOSAL APPROVAL AND ETHICS CLEARANCE (protocol code: Student number 201475286 and date of approval: 14 August 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Description, Structure, and Content of the Servant Leadership Intervention

Appendix A.1. Intervention Aim

The general aim of the servant leadership intervention was to equip leaders with the capability to effectively apply strategic and operational servant leadership principles and practices in the workplace.

Appendix A.2. Intervention Content and Topics

The servant leadership intervention was divided into three modules that included the following topics:

Appendix A.2.1. Module 1: The Heart of a Servant Leader

- 1.1.

- The purpose of a leader.

- 1.2.

- Differentiating between a self-serving leader and a servant leader.

- 1.3.

- Defining leadership and servant leadership

- 1.4.

- Introducing the dimensions of servant leadership

- 1.5.

- Leadership intent: The role and importance of values

- 1.5.1.

- Leadership heartstyles

- 1.5.2.

- Seven levels of consciousness

- 1.5.3.

- Five levels of leadership

- 1.5.4.

- The leadership intent model

- 1.6.

- Personal values

- 1.7.

- Organizational values

Appendix A.2.2. Module 2: The Head of a Servant Leader

- 2.1.

- Introducing four roles of a servant leader: Principles and practices

- 2.2.

- The first function of a servant leader: Set, translate, and execute a higher purpose vision.

- 2.2.1.

- Create a higher purpose vision

- 2.2.2.

- Translate the vision into mission, strategy, and goals

- 2.2.3.

- Execute the vision by serving others

- 2.2.4.

- Stand up for what is right

- 2.2.5.

- Associated servant leadership characteristics and competencies

- 2.3.

- The second function of a servant leader: Become a role model and ambassador

- 2.3.1.

- Self-knowledge: Know your heart, head, and hands.

- 2.3.2.

- Self-management: Manage your mental, physical, and emotional state.

- 2.3.3.

- Self-improvement: Personal development plan.

- 2.3.4.

- Self-revealing: Reveal your authentic self

- 2.3.5.

- Stay within the rules: The essence of business ethics.

- 2.3.6.

- Associated servant leadership characteristics and competencies

- 2.4.

- Differentiating between strategic and operational servant leadership

Appendix A.2.3. Module 3: The Hands of a Servant Leader

- 3.1.

- The third function of a servant leader: Continuously monitor and improve

- 3.1.1.

- Applying good stewardship

- 3.1.2.

- Monitor performance and progress

- 3.1.3.

- Improve and simplify systems, policies, procedures, and products.

- 3.1.4.

- Associated servant leadership characteristics and competencies

- 3.2.

- The fourth function of a servant leader: Align, care, and grow talent.

- 3.2.1.

- Employee-position alignment

- 3.2.2.

- Care for and protect followers: Creating an effective organizational climate and culture to engage employees.

- 3.2.3.

- Grow and empower followers.

- 3.2.4.

- Associated servant leadership characteristics and competencies

- 3.3.

- The talent wheel: Creating a talent pipeline of servant leaders

- 3.4.

- The servant leadership model

- 3.5.

- A framework to apply the servant leadership model

Appendix A.3. Learning Methods

The course utilized the following learning methods and approaches:

- Assessments

- Electronic learning

- Experiential learning

- Micro-learning

- Neuro-learning

- Case studies

- Gamification

- Classroom facilitation

- Group discussions

- Learning videos

- Self-reflection

Appendix A.4. Intervention Structure

The structure and activities of the servant leadership intervention are outlined in Table A1 below.

Table A1.

Structure and Activities of the Servant Leadership Intervention.

Table A1.

Structure and Activities of the Servant Leadership Intervention.

| Activity | Type | Description | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre assessment | Assessment | Personal values assessment | Week 1 |

| E-learning assignment 1 | Video | Five levels of leadership—John Maxwell | Week 1 |

| E-learning assignment 2 | Article | The importance of values in building a high-performance culture | Week 1 |

| Classroom training (Session 1) | Training | Module 1 | Week 1 |

| Pre-assessment | Survey | Servant leadership survey (self) | Week 3 |

| Survey | Servant leadership survey (followers) | Week 3 | |

| Assessment | Personality (15FQ+) | Week 3 | |

| Assessment | Emotional intelligence (EQ-i 2.0) | Week 3 | |

| Experiential challenge 1 | Video Case | Frozen OR Undercover boss | Week 5 |

| Experiential challenge 2 | Workplace | Share your values with your team | Week 5 |

| E-learning assignment 3 | Video | Conscious capitalism | Week 5 |

| E-learning assignment 4 | Policy | Code of ethics | Week 5 |

| E-learning assignment 5 | Article | Managing your energy, not your time. | Week 5 |

| Classroom training (Session 2) | Training | Module 2 | Week 5 |

| Experiential challenge 3 | Workplace Application | Translate the company’s vision, mission, and strategy | Week 6 |

| Experiential challenge 4 | Workplace Application | Compile an individual purpose and development plan | Week 7 |

| E-learning assignment 6 | Video Case | Nokia case study. The Rise and Fall of Nokia (Part 1) | Week 8 |

| Video Case | Nokia case study. The Rise and Fall of Nokia (Part 2) | Week 9 | |

| Video Case | Nokia case study. The Rise and Fall of Nokia (Part 3) | Week 10 | |

| E-learning assignment 7 | Article | The importance of employee engagement | Week 11 |

| Classroom training (Session 3) | Training | Module 3 | Week 12 |

| Experiential challenge 5 | Workplace Application | Conduct improvement analysis: Action plan | Week 13 |

| Conduct improvement analysis: Impact report | Week 28 | ||

| Experiential challenge 6 | Workplace Application | Develop stewardship plans | Week 13 |

| Experiential challenge 7 | Workplace Application | Optimize your working culture: Action plan | Week 14 |

| Optimize your working culture: Impact report | Week 28 | ||

| Experiential challenge 8 | Workplace Application | Implement the recovery, develop, and support model | Week 14 |

| Post-assessment | Survey | Servant leadership survey (self) | Week 15 |

| Survey | Servant leadership survey (followers) | Week 15 |

References

- Babakus, E., Yavas, U., & Ashill, N. J. (2011). Service worker burnout and turnover intentions: Roles of person-job fit, servant leadership, and customer orientation. Services Marketing Quarterly, 32(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock-Roberson, M. E., & Strickland, O. J. (2010). The relationship between charismatic leadership, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Journal of Psychology, 144(3), 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, H. A., & McCann, R. M. (2015). The mediating effect of leader–member dyadic communication style agreement on the relationship between servant leadership and group-level organizational citizenship behavior. Management Communication Quarterly, 30(1), 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B. (2011). An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Albrecht, S. L., & Leiter, M. P. (2011). Key questions regarding work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22(3), 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, J. E., Gottfredson, R. K., & Searle, T. P. (2014). An examination of emotional intelligence as an antecedent of servant leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(3), 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, J. E., & Wheeler, D. W. (2006). Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group & Organization Management, 31(3), 300–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, A. (2013). What do engagement measures really mean? Strategic HR Review, 12(1), 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T. A. (2014). Servant leadership 2.0: A call for strong theory. Sociological Viewpoints, 30(1), 146–167. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, K. (2010). Leading at a higher level: Blanchard on leadership and creating high-performing organizations. FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, K., & Hodges, P. (2008). Lead like Jesus: Lessons for everyone from the greatest leadership role model of all time. Thomas Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, K., Hodges, P., & Hendry, P. (2014). Lead like Jesus encounter: Follow the leader. The Centre for Faithwalk Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbio, A., Van Dierendonck, D., & Manganelli, A. M. (2012). Servant leadership in Italy and its relation to organizational variables. Leadership, 8(3), 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolden, R. (2010). Leadership, management and organizational development. In J. Gold, R. Thorpe, & A. Mumford (Eds.), Handbook of leadership and management development (pp. 1–12). Gower. [Google Scholar]

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Van Den Heuvel, M. (2015). Leader-member exchange, work engagement, and job performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(7), 754–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, F. S., Waseem, M., Rafiq, T., Nawab, S., Khilji, B. A., & Cantt, W. (2014). The impact of leadership on the productivity of employees: An evidence from Pakistan. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, 7(24), 5221–5226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D., & Baghurst, T. (2013). The influence of servant leadership on restaurant employee engagement. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(3), 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatbury, A., Beaty, D., & Kriek, H. S. (2011). Servant leadership, trust and implications for the “base-of-the-pyramid” segment in South Africa. South African Journal of Business Management, 42(4), 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Zhu, J., & Zhou, M. (2015). How does a servant leader fuel the service fire? A multilevel model of servant leadership, individual self identity, group competition climate, and customer service performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinomona, R., Mashiloane, M., & Pooe, D. (2013). The influence of servant leadership on employee trust in a leader and commitment to the organization. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(14), 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J. Y., Jung, C. S., Kyle, G. T., & Petrick, J. F. (2010). Servant leadership and procedural justice in the U.S. National Park service: The antecedents of job satisfaction. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration, 28(3), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzer, M. F. (2019). Leading business beyond profit: A practical guide to leading business to profit and significance. Westbow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzer, M. F., Bussin, M., & Geldenhuys, M. (2017). The functions of a servant leader. Administrative Sciences, 7(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J. (2001). Level 5 leadership: The triumph of humility and fierce resolve. Harvard Business Review, 79(1), 66–76, 175. Available online: https://hbr.org/2005/07/level-5-leadership-the-triumph-of-humility-and-fierce-resolve (accessed on 31 August 2017). [PubMed]

- Collis, J., & Hussey, R. (2009). Business research: A practical guide for undergraduate and postgraduate students (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Construction Industry Development Board. (2015). Labour and work conditions in the South African construction industry: Status and recommendations. Available online: https://share.google/qxVutyClUzKTs9wmj (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Crippen, C. (2005). Servant-leadership as an effective model for educational leadership and management: First to serve, then to lead. Management in Education, 18(5), 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., Bouckenooghe, D., Raja, U., & Matsyborska, G. (2014). Servant leadership and work engagement: The contingency effects of leader-follower social capital. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. (2025). 2025 Global human capital trends. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/talent/human-capital-trends.html#introduction (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Gevers, J. M. P. (2015). Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2012). Work engagement and machiavellianism in the ethical leadership process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(1), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, R. S., & Bocarnea, M. (2005). Development of the servant leadership assessment instrument. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(8), 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, M. J. C., & Van Dierendonck, D. (2014). Servant leadership and engagement in a merge process under high uncertainty. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27(6), 877–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Dimensions International. (2025). Global leadership forecast 2025. Available online: https://www.ddiworld.com/research/global-leadership-forecast-2025 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- De Waal, A. (2007). The characteristics of a high performance organization. Business Strategy Series, 8(3), 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D., Heath, C., & Suls, J. M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: Implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 106–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 57(1), 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., van Direndonck, D., & Liden, R. (2019). Servant leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. The Leadership Quarterly, 30, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, B., & Grayce, M. (2013). Servant leadership: History, a conceptual model, multicultural fit, and the servant leadership solution for continuous improvement. Collective Efficacy: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on International Leadership, 20, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, S., & Collinson, D. (2014). Rethinking global leadership development programs: The interrelated significance of power, context and identity. Organization Studies, 35(5), 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadi, M. Y., Fernando, M., & Caputi, P. (2013). Transformational leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of meaning in work. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 34(6), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R. K. (1998). The power of servant-leadership. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, J. R., & Fields, D. L. (2007). Exploring servant leadership across cultures: A study of followers in Ghana and the USA. Leadership, 3(4), 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanse, J. J., Harlin, U., Jarebrant, C., Ulin, K., & Winkel, J. (2016). The impact of servant leadership dimensions on leader-member exchange among health care professionals. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(2), 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, S. (2010). Engaging employees through whole leadership. Strategic HR Review, 9(3), 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C., Lee, Y., & Chen, W. (2015). The effect of servant leadership on customer value co-creation: A cross-level analysis of key mediating roles. Tourism Management, 49, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., & Liden, R. C. (2011). Antecedents of team potency and team effectiveness: An examination of goal and process clarity and servant leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, T. (2005). Microlearning: A new pedagogical challenge. In T. Hug (Ed.), Microlearning: Emerging concepts, practices and technologies after e-learning (pp. 13–18). Innsbruck University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, H. J. (2005). Contextual implications for transformational and servant leadership: A historical investigation. Management Decision, 43(10), 1410–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E. M., Neubert, M. J., Perry, S. J., Witt, L. A., Penney, L. M., & Weinberger, E. (2013). Servant leaders inspire servant followers: Antecedents and outcomes for employees and the organization. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(2), 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H. J., Kang, M., & Youn, M. (2014). The influence of a leader’s servant leadership on employees’ perception of customers’ satisfaction with the service and employees’ perception of customers’ trust in the service firm: The moderating role of employees’ trust in the leader. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 24(1), 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R., Morgeson, F. P., & Nahrgang, J. D. (2005). Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader–follower outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingraham, P. W., & Getha-Taylor, H. (2004). Leadership in the public sector: Models and assumptions for leadership development in the federal government. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 24(2), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, A. (2008). Extracting leadership knowledge from formative experiences. Leadership, 4(1), 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F., Bande, B., & Varela, J. (2015). Servant leadership and ethics: A dyadic examination of supervisor behaviors and salesperson perceptions. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 35(2), 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009a). Examining the impact of servant leadership on sales force performance. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29(3), 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009b). Examining the impact of servant leadership on salesperson’s turnover intention. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29(4), 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstal, S. P. (2013). Successful strategies for transfer of learned leadership. Performance Improvement, 52(7), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. (2012). Does servant leadership lead to greater customer focus and employee satisfaction? Business Studies Journal, 4(2), 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap, V., & Rangnekar, S. (2016). Servant leadership, employer brand perception, trust in leaders and turnover intentions: A sequential mediation model. Review of Managerial Science, 10(3), 437–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincaid, M. (2012). Building corporate social responsibility through servant-leadership. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(2), 151–171. Available online: https://www.regent.edu/acad/global/publications/ijls/new/vol7iss2/IJLS_Vol7Iss2_Kincaid_pp151-171.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2015).

- Klemich, S., & Klemich, M. (2020). Above the line: Living and leading with heart. Harper Business. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., & Jonas, K. (2013). Transformational leadership and performance: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(4), 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuria, L. K., Namusonge, G. S., & Iravo, M. (2016). Effect of leadership on organizational performance in the health sector in Kenya. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 6(7), 658–663. Available online: http://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-0716.php?rp=P555655 (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Lancaster, S., & Di Milia, L. (2015). Developing a supportive learning environment in a newly formed organization. Journal of Workplace Learning, 27(6), 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R. N. (2014). Developing a Theory of Gamified Learning: Linking Serious Games and Gamification of Learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laub, J. A. (1999). Assessing the servant organization: Development of the organizational leadership assessment (OLA) instrument [Doctoral thesis, Florida Atlantic University]. Available online: https://olagroup.com/Images/mmDocument/Laub%20Dissertation%20Complete%2099.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Leaf, C. (2013). Switch on your brain: The key to peak happiness, thinking, and health. Baker Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. (2010). Design of blended training for transfer into the workplace. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(2), 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liphadzi, M., Aigbavboa, C., & Thwala, W. (2015, June 23–26). An investigation of leadership characteristics of project and construction managers in the South African construction industry. The Eighth International Conference on Construction in the 21st Century, Ljubljana, Slovenia. Available online: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Repository/uj:18432 (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Liu, H., Cutcher, L., & Grant, D. (2015). Doing authenticity: The gendered construction of authentic leadership. Gender, Work & Organization, 22(3), 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, M. M., & Eichinger, R. W. (2006). The career architect development planner (4th ed.). Lominger Limited Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lorente, L., Salanova, M., Martínez, I. M., & Vera, M. (2014). How personal resources predict work engagement and self-rated performance among construction workers: A social cognitive perspective. International Journal of Psychology, 49(3), 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallon, D., Atamanik, C., Chakrabarti, M., Choudhury, V. D., Clarey, J., Derler, A., Erickson, R., Sherman, S., Johnson, D., Manning, C., Mike, J., & Moulton, D. (2017). Rewriting the rules for the digital age: 2017 Deloitte global human capital trends. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/content/dam/assets-shared/legacy/docs/industry/technology-media-telecommunications/2022/DUP_Global-Human-capital-trends_2017.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Maxwell, S. E., & Delaney, H. D. (2004). Designing experiments and analyzing data: A model comparison perspective (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, C. D., Moxley, R. S., & Van Velsor, E. (Eds.). (1998). The Centre for Creative Leadership handbook of leadership development (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S., & Pillay, R. (2011). Revisiting servant leadership: An empirical in Indian context. The Journal Contemporary Management Research, 5(2), 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Melchar, D. E., & Bosco, S. M. (2010). Achieving high organization performance through servant leadership. The Journal of Business Inquiry, 9(1), 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, F., & Stander, M. W. (2011). Positive organization: The role of leader behavior in work engagement and retention. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miao, Q., Newman, A., Schwarz, G., & Xu, L. (2014). Servant leadership, trust, and the organizational commitment of public sector employees in China. Public Administration, 92(3), 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R., & Dorfman, P. W. (2012). Servant leadership across cultures. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T. H. (2020). Experiential learning: A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(8), 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, D., Brand, A., Raghuber, B., Suburaman, F., Beukes, S., & Serepong, T. (2016). SA construction: Highligting trends in the South African construction industry. Available online: https://www.pwc.co.za/en/assets/pdf/sa-construction-2016.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Nesbit, P. L. (2012). The role of self-reflection, emotional management of feedback, and self-regulation processes in self-directed leadership development. Human Resource Development Review, 11(2), 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. J., Kacmar, K. M., Carlson, D. S., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2008). Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on employee behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A., Schwarz, G., Cooper, B., & Sendjaya, S. (2015). How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohria, N. (2021, December 21). What the case study method really teaches. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/12/what-the-case-study-method-really-teaches (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- O’Leonard, K. (2014). The corporate learning factbook 2014: Benchmarks, trends and analysis of the U.S. training market. Available online: https://www.cedma-europe.org/newsletter%20articles/Brandon%20Hall/The%20Corporate%20Learning%20Factbook%202014%20(Jan%2014).pdf (accessed on 18 November 2016).

- Owen, K., Mundy, R., Guild, W., & Guild, R. (2001). Creating and sustaining the high performance organization. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 11(1), 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyilmaz, A., & Cicek, S. S. (2015). How does servant leadership affect employee attitudes, behaviors, and psychological climates in a for-profit organizational context? Journal of Management & Organization, 21(3), 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D., & Wong, T. P. T. (2000). A conceptual framework for measuring servant leadership. In S. Adjibol (Ed.), The human factor in shaping the course of history and development (pp. 69–110). American University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant. (2010). SPSS survival manual: A step-by-step guide for data analysis using SPSS (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Panaccio, A., Henderson, D. J., Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Cao, X. (2014). Toward an understanding of when and why servant leadership accounts for employee extra-role behaviors. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(3), 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]