1. Introduction

Globalisation and workforce internationalisation have made language a pivotal resource in organisational life. Building on the broader human capital literature, upward occupational mobility has long been linked to the accumulation of transferable skills and knowledge (

Wang, 2025). In multilingual organisations, language proficiency represents a parallel form of human capital that similarly facilitates mobility. Multinational corporations (MNCs), as well as increasingly diverse domestic firms, frequently adopt a single corporate language, most often English, as a means of ensuring coordination across dispersed sites, functions, and teams (

T. Neeley, 2012). However, MNCs are better understood as multilingual communities in which headquarters and subsidiary language systems coexist and are shaped by strategy and structure (

Luo & Shenkar, 2006). A uniform corporate language and identity also have external strategic importance, closely tied to employer branding and marketing initiatives aimed at attracting global talent, even though it is often framed internally for coordination. How multilingual organisations convey their culture and values to prospective employees is therefore strongly linked to the mechanics of creating a cohesive corporate brand identity, a process also evident in research on online branding and influencer marketing (

Djafarova & Trofimenko, 2019).

These policies are typically justified on grounds of efficiency, knowledge sharing, and the creation of a unified corporate identity. Yet, language is not merely a neutral medium of communication; it also operates as a mechanism of power and resource distribution (

Angouri, 2013;

Presbitero et al., 2023;

Sanden, 2015;

Piller, 2016). Decisions about which language dominates the workplace can reconfigure opportunity structures, shaping who is visible, trusted, promoted, and assigned to career-enhancing tasks. Corporate language shifts can trigger status loss for non-fluent employees and reconfigure achieved status distinctions within global organisations (

T. B. Neeley, 2013).

These dynamics are increasingly shaped by digitalisation and artificial intelligence (AI). Recent scholarship highlights how AI-mediated communication is altering workplace hierarchies and perceptions of competence, as digital tools can both empower non-native speakers and reinforce exclusionary practices (

Gerpott et al., 2022;

Kelly-Holmes, 2024). In some contexts, AI applications such as machine translation and explainable communication tools have been shown to improve inclusion and efficiency in multilingual teams (

Liu & Chen, 2024). These developments suggest that technology cannot be treated separately from language strategy but must be integrated into organisational policy design.

Language and digital literacy skills are frequently developed from an early age before entering employment. In education, the widespread use of digital platforms such as YouTube for professional knowledge management and skill acquisition reflects a cultural shift towards technology-mediated, self-directed learning that organisations can leverage (

Pires et al., 2022). Evidence from international business and organisational studies further demonstrates that language barriers affect fundamental workplace processes such as trust formation, knowledge transfer, and participation in teams (

Hinds et al., 2014;

Tenzer et al., 2014;

D. E. Welch & Welch, 2008). These processes are directly tied to career mobility. Employees with limited proficiency in the corporate language often face “glass ceilings” that block upward progression and “glass walls” that restrict lateral moves across departments, sites, or international postings (

Latukha et al., 2016). Conversely, proficiency and supportive policies can function as enablers of mobility, broadening access to assignments, networks, and promotions.

Parallel to this, research in English for Specific Purposes (ESP) has long focused on identifying the communication skills required for professional effectiveness. Needs analysis studies consistently highlight variation at the individual level (proficiency, role, and training background), organisational level (industry, site, and policy environment), and operational level (tasks, genres, and interlocutors) (

Lehtonen & Karjalainen, 2008). While such research provides valuable diagnostic tools for curriculum design, it has rarely been systematically connected to career outcomes.

This lack of integration creates a critical gap. Management and international business research often demonstrate that language proficiency and policy shape opportunities but typically treat “language” as a background factor without specifying concrete communicative requirements. In contrast, ESP scholarship offers detailed accounts of workplace needs but seldom links them to mobility pathways such as promotion or cross-functional movement. Bridging these literatures is essential to understand how language functions not only as a competence requirement but also as a form of career capital resource that can be strategically cultivated to support mobility (

Aimoldina & Akynova, 2025;

Bourdieu, 1991). This paper addresses that gap by conducting a framework-based systematic review of empirical studies on workplace language needs and employee mobility in multilingual organisations. Two conceptual lenses structure the review: a mobility model that depicts how proficiency and training determine whether employees experience advancement, delayed progression, or career stagnation; and the Language Needs Analysis (LANA) framework, which categorises needs across individual, organisational, and operational levels. By mapping empirical evidence onto these frameworks, the review consolidates findings across management, international business, and applied linguistics.

This study pursues three research questions:

How do language proficiency and corporate language policies shape employee career mobility, both vertical and horizontal?

What organisational policy mechanisms function as enablers or blockers of mobility?

What workplace language needs are reported at the individual, organisational, and operational levels, and how do these align with the LANA framework?

By addressing these questions, the review positions language as a central yet often overlooked dimension of talent management and career development in multilingual organisations.

2. Conceptual Framework

This review draws on two complementary frameworks to interpret empirical evidence on workplace language and career mobility.

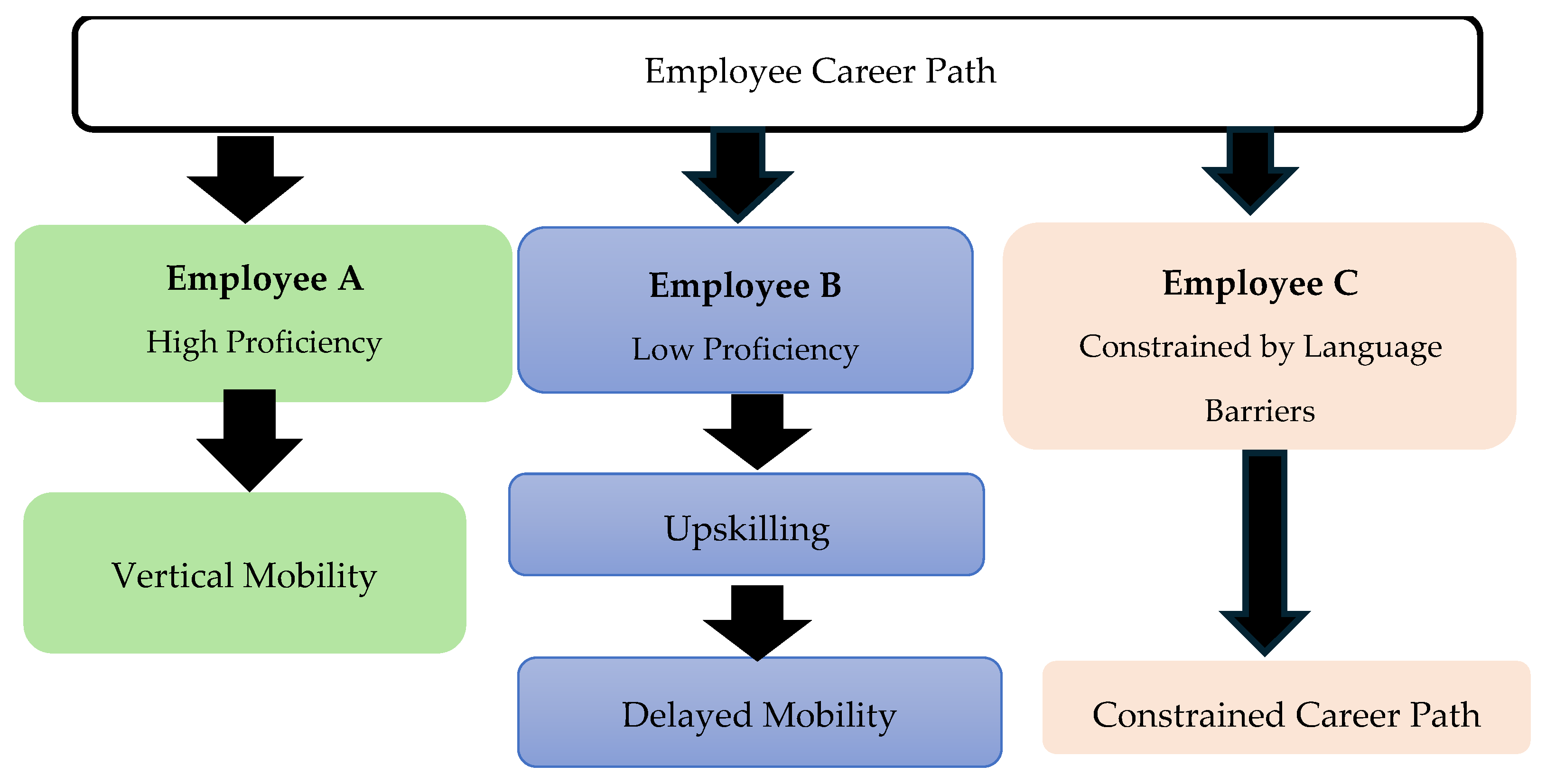

Figure 1 illustrates how language proficiency and policy create “ceilings” and “walls” that shape vertical and horizontal career mobility, while

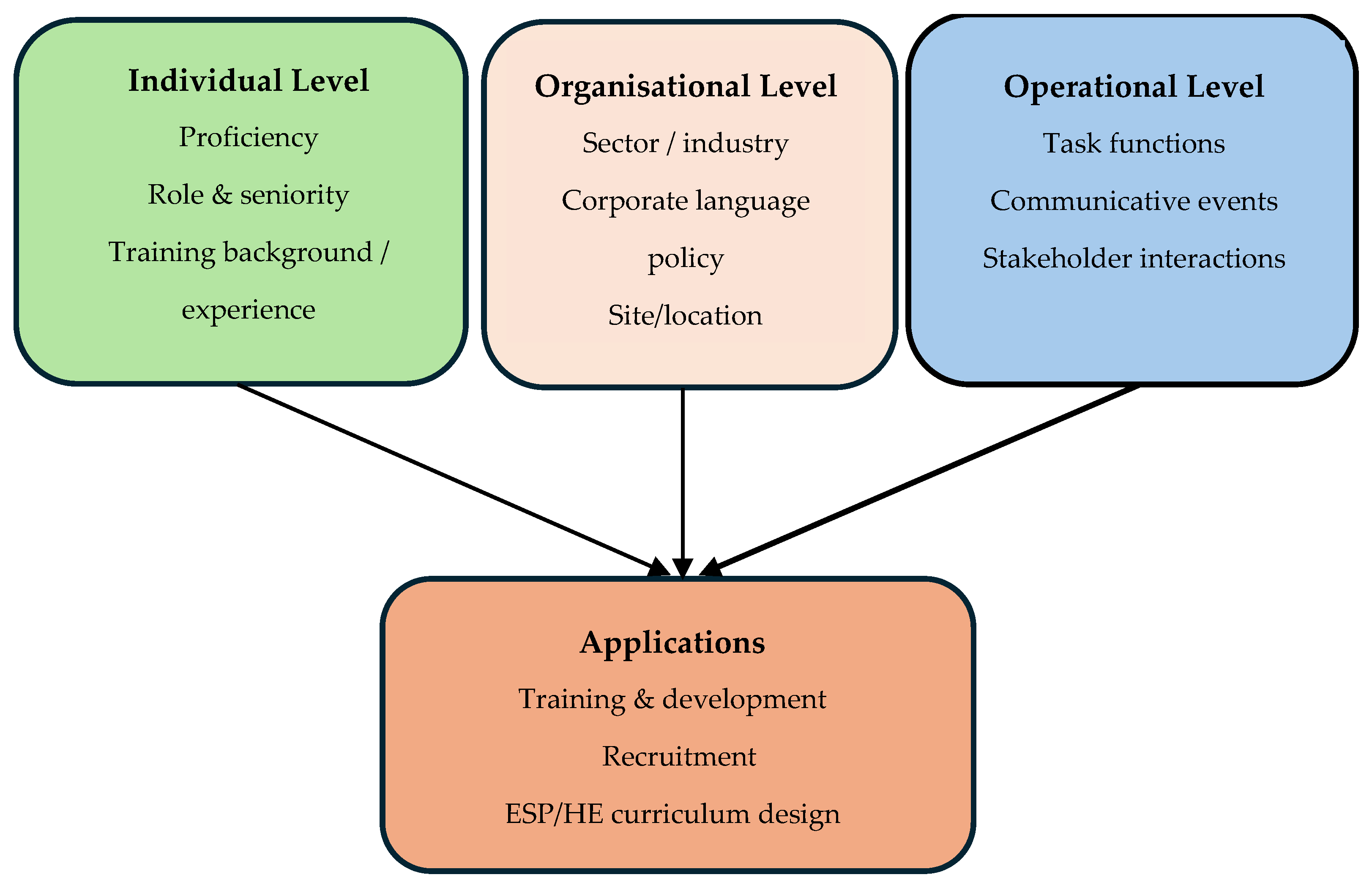

Figure 2 organises workplace language needs into individual, organisational, and operational levels. Together, these frameworks provide the scaffolding for synthesizing studies across management, international business, and English for Specific Purposes (ESP) scholarship.

While each framework offers valuable insights in isolation, the key analytical contribution of this review lies in bringing them together. By integrating the mobility model with the LANA framework, it becomes possible to connect the barriers and enablers of career progression with the concrete communicative requirements of the workplace.

2.1. Language, Mobility, and Invisible Barriers

Language has long been recognised as both an enabler and a barrier in international organisations (

Angouri, 2013;

T. Neeley, 2012). In international business contexts, effective participation often depends less on native-like proficiency and more on communicative competence within Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF) interactions (

Kankaanranta & Planken, 2010). Research shows that language influences not only communication but also career trajectories by shaping access to opportunities, visibility, and participation in decision-making (

Tenzer et al., 2014;

D. E. Welch & Welch, 2008).

Two key metaphors capture these dynamics:

- a.

Language ceilings: invisible barriers that restrict upward mobility. Employees may be denied promotions or leadership opportunities when their proficiency in the corporate language is deemed inadequate, regardless of technical expertise (

T. Neeley, 2012;

Latukha et al., 2016). Such ceilings often coincide with status demotion effects for non-fluent staff (

T. B. Neeley, 2013).

- b.

Language walls: constraints on horizontal mobility, such as lateral transfers across departments, functions, or international sites. Limited proficiency or rigid monolingual policies can prevent employees from moving into new roles or geographical markets (

Angouri, 2013;

Sanden, 2015). Earlier international management research similarly emphasised that language is central to organisational processes, coordination, and control in multinational contexts (

D. Welch et al., 2005).

This conceptualisation aligns with

Bourdieu’s (

1991) view of language as linguistic (cultural) and symbolic capital, conferring power and status within organisations. It also resonates with work showing how linguistic resources affect trust, knowledge transfer, and participation (

Back & Piekkari, 2024;

Tenzer et al., 2014).

Figure 1 operationalises these barriers by mapping three mobility trajectories:

Trajectory A: employees with strong proficiency and ongoing training experience smoother advancement.

Trajectory B: employees who upskill later achieve mobility, though often with delays.

Trajectory C: employees who neither upskill nor receive support remain “invisible,” with stalled careers due to ceilings and walls.

This model provides a structured way to interpret cross-organisational evidence on language and mobility.

2.2. Workplace Language Needs and the LANA Framework

Parallel to mobility research, ESP scholarship has long focused on identifying workplace language and communication requirements (

Lehtonen & Karjalainen, 2008). These needs can be systematically categorised using the Language Needs Analysis (LANA) framework (

Figure 2), which distinguishes three diagnostic levels:

Individual level: proficiency, role, seniority, and training background. Communicative competence varies by career stage, job function, and exposure to international tasks (

Angouri, 2013;

Lehtonen & Karjalainen, 2008).

Organisational level: sector, site, and corporate language policy. For instance, service technicians in industries such as pest control often require strong communicative competence for customer-facing tasks like handling inquiries, describing processes, and managing complaints (

Ching & Zainal, 2018). Meanwhile, in Korea, middle managers in the manufacturing sector, particularly in sales and marketing, tend to use business English more frequently for transactional and non-transactional communication tasks (

Kim, 2021).

Operational level: specific tasks, genres, and interlocutors. Studies consistently identify recurrent communicative events such as emails, meetings, client calls, and reports (

Angouri, 2013;

Lehtonen & Karjalainen, 2008).

Unlike earlier analyses that remained largely diagnostic, LANA links language requirements to organisational policy and career outcomes. This makes it a transferable tool for HR audits and ESP curriculum design (

Kankaanranta & Louhiala-Salminen, 2010).

2.3. Integrating Mobility and Needs Analysis

By combining the mobility lens (

Figure 1) with the needs lens (

Figure 2), this review advances a dual framework for analysing language as career capital. The mobility model explains how proficiency and policy shape opportunity structures through “ceilings” that block upward progression and “walls” that restrict lateral movement. The LANA framework, in turn, specifies the communicative competencies required at the individual, organisational, and operational levels of workplace practice.

Bringing these perspectives together allows mobility trajectories to be linked with specific language requirements. For example, identifying that employees face a “glass wall” in cross-departmental transfers can be systematically connected to LANA categories, such as insufficient mastery of genres (e.g., technical reporting, client negotiation) or organisational-level practices (e.g., policy-driven reliance on English). This integration therefore moves beyond treating language as a generic barrier or enabler and instead specifies which skills, policies, and tasks underpin mobility outcomes.

An illustration of this connection can be found in

Tenzer et al. (

2014)’s study of trust in multinational teams. They show how limited proficiency in the corporate language constrains participation in decision-making, which in mobility terms represents both a glass wall (restricted access to cross-functional roles) and a glass ceiling (barriers to promotion). Mapping this onto the LANA framework reveals the operational-level need for improved meeting interaction skills, alongside the organisational-level requirement for more inclusive language policies. Similarly,

Latukha et al. (

2016) demonstrate that career advancement in Russian MNCs was contingent not only on general English proficiency but also on the ability to manage policy-driven expectations for cross-border reporting. These examples show how the dual framework can specify the competencies that matter most for mobility in different organisational contexts.

From an implementation perspective, the dual framework can support both management and ESP audiences. For HRM and talent managers, it highlights where language-related ceilings and walls may be unintentionally produced by corporate policy, and suggests areas for intervention through training, mentoring, or inclusive policy design. For ESP educators, it provides a systematic way to align curriculum design with real career pathways, ensuring that training in workplace communication is tied directly to advancement opportunities rather than abstract proficiency benchmarks.

In this way, the integration of mobility and needs analysis enables a more comprehensive mapping of empirical studies to both career outcomes and workplace requirements, bridging the concerns of international business and human resource management with those of applied linguistics and ESP.

3. Methods

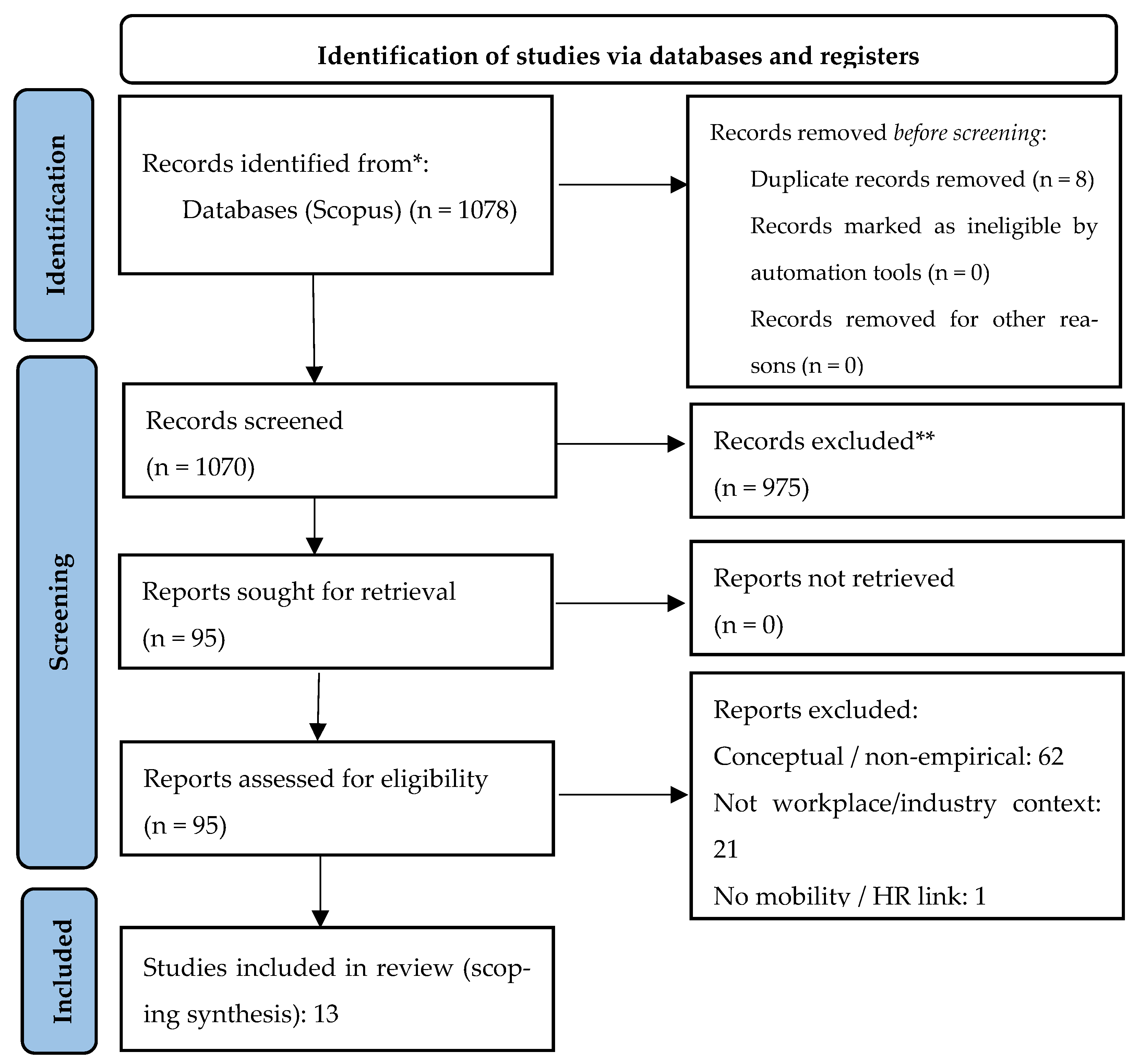

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines to ensure transparency and methodological rigour. A completed PRISMA-ScR checklist is provided, and the study selection process is illustrated in a PRISMA flow diagram. The review proceeded in five stages: (1) a comprehensive search of the Scopus database (2000–2025) using structured keyword combinations; (2) systematic screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts against predefined inclusion criteria; (3) data charting guided by the Language Needs Analysis (LANA) framework and the mobility model; (4) descriptive critical appraisal of methodological rigour using established tools appropriate to study design; and (5) synthesis of findings through framework synthesis, mapping results onto LANA levels and mobility trajectories. Each stage is described in detail in the subsections that follow.

3.1. Review Approach

This study employed a scoping review methodology guided by the PRISMA-ScR framework (

Tricco et al., 2018). It also follows best practices outlined by

Snyder (

2019), who emphasises that systematic literature reviews can provide a rigorous methodology for mapping fragmented evidence across disciplines. As demonstrated in other fields, including engineering and materials science, this methodological approach is now well established across multiple academic domains for identifying the scope and nature of available evidence (

Munn et al., 2018). A scoping review was therefore selected because research on workplace language policies, proficiency, and career mobility remains fragmented across disciplines (management, HRM, applied linguistics), with diverse study designs that preclude meta-analysis. The review aimed to map empirical evidence on how workplace language regimes affect employee mobility and organisational practices.

This scoping review was conducted in full accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines (

Tricco et al., 2018). A completed PRISMA-ScR checklist is provided in

Figure 3 and the study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 3). The review protocol was preregistered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) on 12 September 2025 (DOI:

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2NT8Q (12 September 2025); project link:

https://osf.io/ndmqa (12 September 2025)).

3.2. Search Strategy

Search was carried out in Scopus from January 2010 to April 2025, focusing on management, international business, and workplace communication outlets. Scopus was selected as the primary database because of its broad coverage of peer-reviewed journals across these fields and its strong indexing of business communication and multilingual management research.

To maximise sensitivity while maintaining relevance, titles, abstracts, and keywords were searched using Boolean logic, truncation, and proximity operators. The core strategy combined three concept blocks—(A) language & lingua franca, (B) policy/proficiency, and (C) mobility/employability/career outcomes—linked with AND.

Example Scopus query:

(“language” OR “lingua franca” OR “multilingual*”) AND (“policy” OR “proficiency” OR “corporate language”) AND (“mobility” OR “employability” OR “career capital” OR “career outcomes”).

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible if they met all the following criteria:

Empirical in design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods).

Published between 2010–2025 in peer-reviewed journals.

Explicitly focused on workplace or industry contexts (e.g., multinational corporations, SMEs, professional practice).

Addressed at least one of the following:

how language proficiency or policy affects career mobility (vertical or horizontal),

organisational mechanisms that enable or block mobility, or

workplace language needs aligned with the Language Needs Analysis (LA-NA) framework.

Studies were excluded if they focused solely on educational settings, prisons, healthcare, or other non-workplace contexts, or if they were purely conceptual/theoretical without empirical data.

However, one highly influential non-empirical work (

Presbitero et al., 2023) was retained in supporting capacity. These were not part of the core empirical dataset but are referenced in the synthesis to contextualise findings.

3.4. Study Selection

The database search yielded 1078 records in Scopus (2010–2025). After removing duplicates (n = 8), 1070 titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria, resulting in the exclusion of 975 records that were not directly relevant to workplace/industry contexts or employee mobility/HR mechanisms. Ninety-five full-text reports were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Of these, 83 were excluded for the following reasons: 62 were conceptual/theoretical, 21 were not situated in workplace/industry contexts, 1 lacked explicit mobility or career relevance, and 1 provided insufficient methodological detail. Twelve empirical studies met all criteria and formed the core dataset for analysis. In addition, one influential conceptual work was retained in a supporting capacity to provide theoretical and contextual framing. The final scoping synthesis therefore drew on 13 studies in total: 12 empirical and 1 conceptual.

PRISMA-ScR counts (n):

Records identified (Scopus): 1078

Records after duplicates removed: 1070

Records screened (title/abstract): 1070; excluded: 975

Full-text articles assessed: 95; excluded: 83

Studies included in final synthesis: 13 (12 empirical +1 contextual)

3.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

Key study characteristics were charted in an Excel matrix, including author(s), year, country, sector, sample, methodology, and relevance to each RQ. A two-stage coding process was applied:

For the main synthesis, only the twelve empirical studies were used to map evidence systematically to the three research questions. The single additional conceptual work was drawn upon selectively to provide theoretical and contextual framing but was not treated as part of the empirical evidence base.

Records identified in Scopus (n = 1,078); duplicates removed before screening (n = 8); titles/abstracts screened (n = 1,070); records excluded (n = 975); full texts assessed for eligibility (n = 95); full texts excluded for the following reasons: (1) conceptual/non-empirical (n = 62); (2) not workplace/industry context (n = 21); (3) no mobility/HR link (n = 1); (4) insufficient methodological detail (n = 1). Reports not retrieved (n = 0). Studies included in the scoping synthesis (n = 13: 12 empirical + 1 conceptual).

3.6. Data Charting

A structured extraction form guided the charting process, drawing on the Language Needs Analysis (LANA) framework and the mobility model. We extracted the following variables: author(s), year of publication, country/sector, organisational context, methodological approach, participant characteristics, reported workplace language needs, corporate language policies, and career-related outcomes. Full study characteristics are provided in

Appendix A, which summarises the 13 included studies (2010–2025). All are set in workplace/industry contexts and explicitly link language proficiency and/or policy to mobility or HR outcomes. Each entry lists author/year, title, source, DOI (where available), methodology, and a one-line summary mapped to the review questions.

3.7. Critical Appraisal

In line with scoping review methodology, no studies were excluded on quality grounds. Nevertheless, methodological rigour was assessed descriptively to provide an overview of strengths and limitations across the evidence base. Standard appraisal tools were applied according to study design: the CASP checklist for qualitative studies, the MMAT for mixed methods designs, and the JBI checklists for quantitative and case study research. These appraisals were not used as exclusion criteria but served to contextualise findings and guide interpretation in the synthesis.

3.8. Methodological Transparency

Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts and full texts. Disagreements were resolved through discussion; when consensus could not be achieved, a third reviewer acted as an independent arbitrator, and their decision was considered final. All arbitration decisions were documented and are reflected in the PRISMA flow diagram. This three-reviewer process ensured transparency and minimised potential bias in study selection.

4. Results

A total of thirteen studies published between 2010 and 2025 met the inclusion criteria. Twelve were empirical studies, and one influential conceptual work was retained in a supporting capacity to provide theoretical context. All were situated in workplace or industry settings and addressed at least one of the three research questions. The empirical studies comprised survey-based (n = 2), qualitative (n = 4), mixed-methods (n = 2), and quantitative (n = 3) designs, as well as one book-length, case-based qualitative study. The single non-empirical work was a conceptual article that offered theoretical framing for global language policy and workplace communication. Organisational contexts spanned Russian and other Asian multinationals, European corporate teams, expatriate assignments, and hybrid or virtual workplaces. Detailed study characteristics are presented in

Appendix A.

4.1. The Influence of Language Proficiency and Corporate Language Policies on Vertical and Horizontal Employee Career Mobility

Eight of the thirteen studies addressed how language proficiency and corporate language policies shape both vertical and horizontal career mobility. Survey evidence from Russian multinationals revealed that employees with lower levels of corporate language proficiency perceived reduced opportunities for promotion and lateral transfer, describing language as both a “glass ceiling” and a “glass wall” in their careers (

Latukha et al., 2016). Comparable dynamics were reported in Japanese multinationals, where ethnographic studies showed that English-only mandates often produced early-stage exclusion and status loss for non-fluent employees, though these effects could be mitigated when the policies were coupled with structured training and support (

T. Neeley, 2012,

2017;

T. B. Neeley, 2013). Evidence from European multinational teams demonstrated that language barriers also undermined trust and sponsorship, thereby limiting visibility and advancement opportunities (

Tenzer et al., 2014). Recent firm-level evidence shows that language barriers impede knowledge transfers within multinationals, with downstream effects on access to high-visibility tasks and advancement opportunities (

Guillouët et al., 2024). More recent qualitative research extended these findings to virtual workplaces, showing that employees with weaker proficiency were less likely to be entrusted with leadership roles in online meetings, even when they were otherwise competent contributors (

Back & Piekkari, 2024). These results highlight the value of digital resources that can facilitate language learning and collaboration in work settings. One possible approach to creating low-stakes, practical language training interventions for the workplace is the use of cloud-based collaborative platforms such as Google Docs, which have been demonstrated in educational settings to improve motivation and proficiency in second-language writing tasks (

Godwin-Jones, 2021).

Taken together, these findings illustrate three mobility trajectories: employees with strong proficiency and ongoing training advanced smoothly; late upskillers experienced delayed mobility; and those without support remained “invisible” behind language-related ceilings and walls.

4.2. Policy Mechanisms as Facilitators and/or Barriers to Career Mobility

Eight of the thirteen empirical studies examined the role of organisational policy mechanisms in shaping mobility outcomes. Across cases, a persistent gap emerged between formal policy and local practice. For example, research in European workplaces highlighted that while firms often enforced corporate “one language” rules, employees relied on multilingual repertoires in practice to complete tasks effectively (

Angouri, 2013). Some organisations adopted more flexible approaches, and evidence from Nordic workplaces demonstrated that Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF)—with its emphasis on clarity and sufficiency rather than native-like accuracy—reduced exclusion while maintaining communicative efficiency (

Kankaanranta & Louhiala-Salminen, 2010;

Kankaanranta et al., 2018).

Ethnographic and case-based research in Asia confirmed that corporate language mandates operated as double-edged swords: in the short term, they reduced participation and reinforced status hierarchies, but when accompanied by systematic training, they later fostered shared communicative platforms that enabled collaboration and mobility (

T. Neeley, 2012,

2017). At the team level, language barriers that were not addressed through flexible policy design reduced trust and inhibited knowledge sharing, undermining career advancement opportunities (

Tenzer et al., 2014). In virtual contexts, discriminatory dynamics were observed, as employees were frequently evaluated less on the adequacy of their contributions than on accent or perceived “nativeness,” disadvantaging otherwise competent staff in appraisals and promotions (

Back & Piekkari, 2024).

Recent quantitative evidence demonstrates that language barriers constrain intra-firm knowledge flows, while targeted policies can mitigate these frictions (

Guillouët et al., 2024). A study of multinationals in Asia found that language barriers directly constrained knowledge transfer and trust formation, but that targeted policy interventions could significantly improve collaboration (

Cho et al., 2025). Complementary evidence from large-scale firm data shows that tacit knowledge transfer in management roles is shaped by both language proficiency and organisational support, with implications for career mobility and cross-functional participation (

Astorne-Figari & Lee, 2025).

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that organisational policies can function as either enablers or blockers, depending on their design, flexibility, and degree of institutional support.

4.3. Workplace Language Needs and Alignment with the LANA Framework

Seven of the thirteen studies discussed workplace language needs, and their findings align closely with the three diagnostic levels of the Language Needs Analysis (LANA) framework.

At the individual level, research consistently indicated that functional proficiency, interactional competence, and persuasive communication were more highly valued than grammatical accuracy. For example, both case-based and ethnographic evidence demonstrated that managerial staff were often expected to display strong presentation and persuasive skills, while technical staff relied more heavily on reading comprehension and accurate documentation (

Kankaanranta & Planken, 2010;

T. Neeley, 2017).

At the organisational level, sector and site characteristics were decisive. Studies showed that service industries prioritised oral interaction and client communication, whereas manufacturing placed greater emphasis on safety communication and technical documentation (

Angouri, 2013;

Yao & Du-Babcock, 2020). Within multinational headquarters, high levels of written and spoken competence were required to contribute to global meetings and reporting processes (

T. Neeley, 2017). Quantitative evidence extends this perspective, demonstrating how language proficiency shapes knowledge transfer patterns and tacit communication in multinationals, thereby influencing both trust and career opportunities (

Astorne-Figari & Lee, 2025;

Cho et al., 2025).

At the operational level, common tasks included emails, reports, meetings, and virtual calls—each requiring flexibility in register and intercultural sensitivity (

Angouri, 2013;

Back & Piekkari, 2024;

Kankaanranta et al., 2018)). The distribution of findings across the three LANA levels underscores the framework’s diagnostic utility for linking language requirements directly to HR audits and ESP curriculum design.

Taken together, the findings from the thirteen included studies demonstrate that language functions simultaneously as both a career enabler and a career barrier in multilingual organisations. In relation to RQ1, evidence from diverse geographic and organisational contexts shows that language proficiency and corporate policy play central roles in shaping employee mobility. In relation to RQ2, organisational mechanisms such as flexible policy design, BELF practices, and training provision emerge as enablers, while rigid mandates and discriminatory practices reinforce language ceilings and walls. In relation to RQ3, studies consistently mapped workplace language needs onto the individual, organisational, and operational levels of the LANA framework, confirming its value as a tool for diagnosing communicative requirements. Overall, the synthesis highlights the importance of addressing language strategically in HR planning and ESP curriculum development, as it directly affects employability, inclusion, and the distribution of career opportunities in multilingual workplaces.

5. Discussion

Although the search spanned publications from 2010 to 2025, the final inclusion set comprised studies published primarily between 2010 and 2024, with the majority clustered in the first half of this period. This distribution reflects the nature of the evidence base rather than limitations in the search strategy. More recent work has tended to be conceptual, education-focused, or disconnected from career mobility outcomes, meaning that systematic empirical investigations remain scarce. The absence of sustained empirical engagement since 2015 is striking, given the accelerating attention to global HRM, employability, digital communication, and AI-mediated interaction.

Recent scholarship underscores the transformative role of digitalisation and artificial intelligence (AI) in reshaping workplace communication and employee visibility. AI-driven tools such as real-time translation, writing assistants, and automated meeting transcriptions are increasingly used to support multilingual collaboration. Emerging evidence suggests that these technologies can reduce language-related barriers and improve inclusion while simultaneously introducing new dependencies and inequalities (

Gerpott et al., 2022;

Van Quaquebeke & Gerpott, 2024).

In leadership and organisational communication contexts, AI is becoming deeply embedded in decision-making and competence signalling processes, reshaping how employees display credibility and trustworthiness (

Cascio & Montealegre, 2016;

Kellogg et al., 2020;

Van Quaquebeke & Gerpott, 2024). These developments highlight the importance of integrating AI literacy into human resource (HR) systems as a complementary form of career capital alongside linguistic proficiency and intercultural communication competence.

Virtual and hybrid work environments add further complexity. Studies of multilingual and migrant professionals indicate that language-based discrimination can be amplified in digital settings, where accent, fluency, and online presence become decisive markers of credibility (

Back & Piekkari, 2024). At the same time, virtual collaboration platforms enable asynchronous participation, for instance, through shared documents and written discussion threads, which may provide non-native speakers with more equitable avenues for contribution (

Glikson & Woolley, 2020). This dual impact underscores the need for more nuanced language and technology policies that address both the risks of exclusion and the opportunities for enhanced participation in AI-mediated, multilingual workplaces.

A comparative perspective is also critical. Much of the foundational literature on language and mobility derives from European and North American contexts, where English is often assumed to be the uncontested lingua franca. However, emerging evidence from Asia and transitional economies shows that language policies have different stakes: in developed contexts, corporate English policies often serve efficiency and branding purposes, whereas in emerging economies they can determine access to entire sectors of employment and upward mobility (

Aimoldina & Akynova, 2025). Comparative HRM research therefore needs to examine how Global South and Global North organisations differ in balancing efficiency, equity, and identity when implementing language and digital policies.

In summary, the discussion of language as career capital must increasingly account for digitalisation and AI, virtual modes of collaboration, and the comparative diversity of global workplaces. By embedding these factors into HRM debates, scholars and practitioners can move beyond static understandings of language policy toward dynamic frameworks that reflect the realities of twenty-first-century work.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This review affirms that language functions not only as a communicative tool but also as a form of career capital in multilingual organisations. At the individual level, proficiency and interactional competence emerge as prerequisites for visibility and access to high-value assignments. Employees who upskill late face slower, less predictable trajectories, while those without support risk professional “invisibility.” These findings resonate with

Bourdieu’s (

1991) theorisation of symbolic capital and extend it into the domain of linguistic competence. They also align with the Graduate Capital Model, which conceptualises employability as comprising human, social, and cultural capitals. In this perspective, language proficiency represents a form of career capital that underpins graduates’ long-term employability and mobility (

Nguyen & Ngo, 2023).

At the organisational level, language policies appear as decisive mechanisms. Rigid monolingual mandates exacerbate inequalities by restricting participation and limiting cross-functional exposure (

T. Neeley, 2012). In contrast, policies that institutionalise Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF), valuing clarity and adequacy over native-like accuracy, broaden opportunities and mitigate discrimination (

Kankaanranta & Louhiala-Salminen, 2010). These findings contribute to international business scholarship by framing language policy not as an operational detail but as a strategic lever of diversity, equity, and inclusion (

Back & Piekkari, 2024;

Tenzer et al., 2014). They also connect with the Resource-Based View (RBV), under which language competencies and inclusive policies can be seen as intangible, hard-to-imitate organisational resources that provide sustained competitive advantage in global labour markets.

At the operational level, the evidence reinforces the robustness of the LANA framework as a diagnostic lens. Recurrent communicative events across industries such as emails, meetings, reports, and client interactions demonstrate that workplace communication needs are multi-layered and task-specific (

Angouri, 2013;

Lehtonen & Karjalainen, 2008). By mapping these needs directly to career outcomes, the review bridges two historically separate strands of scholarship: international business research on corporate language policy, trust, and participation, and applied linguistics research on workplace communication needs. This integration advances theoretical understanding by showing that needs and policies must be analysed together to explain how language translates into career capital.

Context also matters. Much of the foundational literature on language and mobility has been based in European and North American settings, where English is often treated as the uncontested lingua franca. Recent studies in Asia and transitional economies, however, reveal that language policies can determine access not only to promotions but also to entire sectors of employment (

Harzing & Pudelko, 2013;

Tenzer et al., 2021). Moreover, digitalisation and AI-mediated communication are reshaping symbolic capital. Tools such as real-time translation, AI writing assistants, and hybrid communication platforms influence how competence and credibility are evaluated, creating opportunities for inclusion while also introducing risks of dependency or exclusion. This suggests that theorisation of language as career capital must now integrate technological mediation alongside linguistic and cultural dimensions.

5.2. Practical Contributions

Beyond its theoretical implications, this review also generates several practical contributions for both organisational policy makers and educators.

For Human Resource Management and organisational leaders, the dual framework of mobility and needs analysis provides a diagnostic tool for identifying how language policies shape talent management outcomes. The mobility model illustrates where employees may encounter “ceilings” and “walls,” while the LANA framework specifies the underlying competencies and tasks associated with those barriers. Taken together, the frameworks enable managers to pinpoint where organisational policies inadvertently restrict access to career-enhancing opportunities and to design targeted interventions. These may include more inclusive language policies, mentorship programs for non-native speakers, or tailored training initiatives that address operational-level skills such as technical reporting or client negotiation. In multilingual workplaces increasingly mediated by digital tools, AI literacy and digital communication competence also function as complementary forms of career capital. Integrating these into HR systems can help organisations reduce barriers, broaden access to mobility pathways, and future-proof their workforce.

For English for Specific Purposes (ESP) educators and curriculum designers, the integration of mobility and needs analysis provides guidance on how professional communication training can be more closely aligned with actual career trajectories. Rather than focusing solely on generic language proficiency, ESP curricula can target the genres, tasks, and policies that directly enable mobility across departments and organisational levels. In this way, language instruction can be reframed as the cultivation of career capital, preparing learners not just to meet immediate workplace demands but also to navigate long-term mobility pathways.

Finally, these interventions must be tailored to global diversity. In developed economies, corporate English policies often serve efficiency and branding purposes, while in emerging economies they can determine access to entire sectors of employment and promotion. Practical contributions must therefore be designed with sensitivity to comparative contexts, ensuring that language and digital policies enhance inclusion rather than reinforce inequality.

Together, these practical contributions highlight how organisations and educators can strategically cultivate language as a resource for inclusion, performance, and advancement. By explicitly linking communicative competencies with career mobility outcomes, the review offers actionable insights for creating more equitable and future-oriented workplaces.

6. Practical Implications

The findings of this review have direct implications for both organisational practice and educational design. By linking mobility trajectories with concrete communicative requirements, this study highlights how language functions not only as a medium of coordination but also as a form of career capital that shapes access to opportunities. This section outlines the implications for Human Resource Management (HRM) and for English for Specific Purposes (ESP) and Higher Education (HE), emphasising how organisations and educators can translate the dual framework of mobility and needs analysis into actionable strategies.

6.1. Human Resource Management (HRM)

Organisations should treat language as a strategic resource embedded in recruitment, training, and promotion systems. Recruitment processes need to reference LANA levels to ensure that criteria reflect actual role demands rather than idealised native-speaker standards. Innovative assessment techniques such as video résumés and AI-driven screening tools can better evaluate communicative and presentation skills in global recruitment (

Chamorro-Premuzic et al., 2021;

Hiemstra et al., 2012). Learning Management Systems (LMS) like Blackboard and Moodle enable scalable workplace communication training (

Martin et al., 2020). Role-specific training combined with mentoring enhances interactional competence and facilitates visibility and promotion (

Guillouët et al., 2024). However, pressure to master new languages and technologies may induce stress and affect work–life balance (

Presbitero et al., 2023); thus, supportive policy design is essential. Organisations adopting an “English-plus” approach—combining a corporate lingua franca with local language use—promote stronger knowledge flows and inclusivity (

T. Neeley, 2017;

Sanden, 2015). AI-driven tools such as real-time translation and automated transcription further reduce barriers but demand new competencies. HR systems should embed AI literacy and digital communication competence in training frameworks (

Cascio & Montealegre, 2016;

Van Quaquebeke & Gerpott, 2024).

6.2. English for Specific Purposes (ESP) and Higher Education (HE)

ESP and HE programmes must align curricula with workplace communicative demands. English for Occupational Purposes (EOP) training enhances communication, teamwork, and intercultural competence, improving graduate employability (

Basturkmen, 2019;

Evans & Morrison, 2018). Integrating needs analysis and employer collaboration yields more industry-relevant competencies (

Ding & Bruce, 2017). Incorporating Business English as a Lingua Franca (BELF) fosters adaptive, linguaculturally sensitive communication (

Kankaanranta & Louhiala-Salminen, 2010). Universities can act as strategic HR partners by co-developing ESP- and BELF-informed programmes with industry. Embedding AI-supported translation tools and collaborative cloud platforms in tasks prepares students for hybrid communication environments (

Glikson & Woolley, 2020;

Godwin-Jones, 2021). Such initiatives not only strengthen linguistic proficiency but also cultivate hybrid human–AI communication competence valued

in global industries.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Although the search retrieved a substantial number of studies, twelve empirical works ultimately met the inclusion criteria. Of these, only a subset directly examined career mobility outcomes, while others addressed workplace language policies or communicative practices more broadly. Rather than weakening the synthesis, this imbalance highlights the underdeveloped state of research at the intersection of workplace language, corporate policy, and employee mobility. The contribution of this review therefore lies not only in consolidating existing findings but also in identifying the contours of a field where systematic and contemporary work is urgently required.

Second, the search was restricted to Scopus-indexed and English-language publications. Scopus was chosen because of its extensive coverage of management, international business, and applied linguistics journals, and because it indexes many of the high-impact outlets most relevant to this review. While databases such as Web of Science or LLBA could also have been consulted, overlap in coverage and resource constraints led to the prioritisation of Scopus. Nevertheless, this reliance raises the possibility of single-database bias, and the restriction to English-language sources introduces an Anglophone bias that sits uneasily with the critique of monolingual dominance advanced in this review. Although backward and forward citation chasing mitigated some risks, relevant non-English and non-Scopus studies may have been missed. This limitation reflects not only methodological choices but also broader structural patterns, as non-Anglophone research in this domain remains systematically under-represented.

Third, in line with scoping review methodology, the appraisal of methodological quality was descriptive and non-exclusionary. This approach was appropriate for mapping a diverse evidence base but means that the findings should be interpreted as indicative rather than definitive.

Future research can build on these limitations in several directions. Longitudinal and mixed-methods studies are needed to capture how language proficiency and policy interventions shape career mobility over time. Comparative and cross-sectoral analyses are also required to link organisational policy perspectives with individual-level outcomes, especially in underrepresented contexts such as emerging economies where global languages function simultaneously as enablers of opportunity and as sources of inequality. Finally, the implications of digitalisation and AI-mediated communication, including virtual collaboration, machine translation, and AI writing support—remain largely unexplored. Addressing these gaps would move the field beyond fragmented evidence toward a more comprehensive account of language as career capital, and would help to clarify how language, technology, and policy intersect to shape talent management and mobility in multilingual organisations.

In summary, this review consolidates evidence across management, international business, and applied linguistics to demonstrate how language functions as both a barrier and a resource in shaping career mobility. By integrating the mobility and LANA frameworks, it provides a dual lens that is valuable to theory, practice, and policy. These contributions, alongside the identified limitations and future research agenda, set the stage for the concluding reflections presented in the next section.

8. Conclusions

This review has demonstrated that language is more than a communicative tool: it is a form of career capital that shapes promotion, lateral transfer, and long-term progression in multilingual organisations. Corporate language policies and individual proficiency levels often act as invisible ceilings and walls, while supportive training programmes and hybrid language regimes function as enablers of mobility. By applying both the mobility model and the LANA framework, the review consolidates evidence across HRM, international business, and ESP, showing how communicative needs at the individual, organisational, and operational levels connect directly to career outcomes.

The originality of this review lies in bridging language needs analysis with career mobility outcomes—two strands of scholarship that have typically evolved in parallel rather than in dialogue. By integrating these perspectives, this study reframes language not merely as a communicative skill but as a strategic organisational resource with direct implications for equity, inclusion, and performance in global workplaces.

For HRM, the findings highlight the importance of inclusive language policies, BELF-oriented assessments, and tiered training initiatives in supporting equity and retention. For ESP and higher education, they underscore the need to align curricula with workplace communicative demands and to position competence as a driver of career advancement rather than simply entry-level employability. Ultimately, treating language as career capital allows organisations to transform multilingualism from a source of friction into a source of opportunity.

At the same time, the absence of recent empirical studies signals that this field remains underdeveloped. Addressing this gap through longitudinal, comparative, and digitally oriented research will be critical for understanding how language continues to shape mobility in an era of virtual collaboration, AI-mediated communication, and global workforce diversity. By doing so, organisations can not only strengthen employee mobility but also unlock the full potential of diverse workforces in an increasingly interconnected economy.