Abstract

The article describes the premises and conditions for the implementation of a pro-landscape spatial policy in rural areas in Poland. It presents the erosion of spatial order in a large part of the country’s territory. Firstly, the state of protection of the rural landscape and the legal aspects of shaping the space of rural areas are described. Secondly, the location is depicted, and the main physiognomic and environmental threats in the rural areas are discussed. It is then questioned whether the statutory regulations that have been introduced into the spatial planning system and adapt the Polish law to the requirements of the European Landscape Convention will stop the degradation of the landscape. Deep systemic changes are needed, as they will lead to the involvement of public policy in shaping the landscape and the introduction of tools and procedures for the management of visual landscape resources. They would constitute a convenient space for mediation in the relations between actors operating in space and an open knowledge laboratory of the environment, which would be useful in the participatory planning process. The presented arguments and conclusions result from the review and analysis of research results, which are mainly in the field of landscape protection and rural area management.

1. Introduction

Rural areas are administratively 93.4% of Poland’s area. This area is usually inhabited by 39.7% of the country’s population. Demographic forecasts predict a steady, minor increase in the number of rural residents by 2035. This increase is mainly a result of the positive balance of internal migration. At the end of the 1990s, city residents began to move to the countryside, and particularly to suburban municipalities [1,2,3]. The suburbanization process is accompanied by the urbanization of economically stronger commune villages and villages that are located in areas that are attractive for tourists. At the same time, the acreage of crops is systematically decreasing, which results from the increased productivity of agricultural production and the conditions on the global market. The result of the changing situation of agriculture in the national economy is the inactivation of many family farms and deagrarization, which is defined as the decrease in the number of agriculture-related rural residents, the increase of forest cover, and fallow lands. At the same time, the number of large-scale farms is systematically increasing. The economic development of the country and clear striving to improve living conditions has led to the development of communication and energy infrastructure, as well as the multifunctionality of the village [4]. Socio-economic transformation is accompanied by the erosion of spatial order. Nowadays, the area of rural areas is an arena of opposing diverse influences and conflicting needs that are both institutional and individual. This translates into the degradation of both landscape and the environment, as well as the deterioration of living and farming conditions [5]. For example, the excessive dispersion of buildings makes it difficult for residents to access service infrastructure, which is a source of increased social exclusion. A significant increase in the distance to work places and services causes growth in the number of car trips, as well as higher air pollution and safety hazards in road traffic. New residential and road investments divide cultivated fields and disrupt rational farming. Systematic enlargement of the impermeable areas and expansion of rainwater drainage network limits the retention of rainwater and threatens hydrological balance and biodiversity [6,7,8,9]. However, the costs of spatial chaos are poorly researched, and society is not yet aware of them. The ignorance also concerns the importance of the area’s physiognomy and its degradation [10].

After the political transformation of 1989, the focus was on improving the living conditions of Poles, and especially rural residents, due to the backwardness of rural development. In the heat of economic and material reconstruction, it was forgotten that it was necessary to create a vision [11,12] that would keep spatial development on the trajectory of sustainability [13]. At crucial moments in history (and state system change was one of them), the collective vision is a prerequisite for preserving the continuity of spatial order and its evolutionary, not revolutionary, reconstruction [14,15]. Unfortunately, no effort has been made to popularize the spatial patterns that are characteristic for villages, and that could form new settlements and give them a distinguishing local expression [16,17,18]. The field of common-sense reasons of investors has been placed on the opposite pole regarding the political declarations and official spatial strategies [19]. As a result, pragmatic and law-abiding decisions increase spatial chaos. Too often, even legal regulations regarding nature or landscape protection are ineffective, as they contradict the interests, convictions, and habits of citizens [20].

Social, environmental, and economic threats that are related to chaotic spatial changes in rural areas need to be ceased. To achieve this, solutions should be applied to ensure consistency. They are provided by a pro-landscape spatial policy (landscape policy) of the state and municipalities, which aims at the comprehensive recognition of local spatial and social relations, and enables the creation of a merging local vision planning. Landscape policy is a stream of strategies, programs, projects, and actions initiated by the state. It is then implemented by the state institutions, state and local government administration bodies, non-governmental organizations, and the enterprise sector in order to protect and create new landscapes of high aesthetic value. It shapes knowledge and social attitudes within spatial planning, education, and market systems. The pillars of the integrated landscape policy are legal principles, procedures, and tools, as well as public support for their implementation. Landscape policy actively uses the tools of the visual assessment of areas, which facilitates the participation of citizens in the management of space and gives integrated policy to spatial policy [21,22,23].

Unlike in Poland, landscape management systems have been operating in many European countries [24], such as in the United States (USA), Canada, and Australia for years [25,26,27,28]. Landscape creation has been associated with spatial planning, and constitutes its skeleton. In addition to protecting historical landscapes, it is important to shape new ones. The inventory of landscape resources, analysis of the quality of views, landscape guidelines, or visual assessments of the impact of designed objects on the environment are a mandatory part of any pre-planning or pre-design analysis. Planning is based on the results of identification and the assessment of landscape units [29,30]. In the British model, the assessment is continuous and hierarchical [31]. Changes are monitored. The hierarchy of areas and types of landscapes allows analyzing them at every level: national, regional, local, and functional. The stakeholder process is involved in the assessment process, bringing in local knowledge, and thus accepting guidelines more easily [32].

The premise for creating a similar system in Poland is the scale of visual chaos, in particular in rural areas and its social and ecological costs. Two negative conditions for the introduction of a landscape management system are: an obligatory, dysfunctional legal model of space management, and widespread ignorance about the importance of the landscape [33]. These are strong arguments for developing a landscape policy that would help overcome these adversities.

2. Visual Transformation of Rural Areas in Poland after 1989

The issues of the visual shaping of protected landscapes are the subject of many publications and reports e.g., [34,35,36,37]. Their conclusions affect the spatial policy of communes, for example in the form of conservation rules. Nevertheless, the extent of the crisis in the visual quality of landscapes and spatial order in rural areas is constantly growing [37,38,39]. The following description of the main change zones outlines the visual destruction of the landscape (assessed by the observer) in the context of economic, ecological, or social costs (assessed by experts) [40,41]. (The content of this chapter comes from the author’s presentation Threats to the rural landscape in spatial-physiognomic terms at the seminar Landscape protection in environmental impact assessments in the light of contemporary legal and methodological conditions, which took place at Gdańsk University of Technology, Poland on 20 April 2018 [40].)

The universal rural areas of physiognomic changes include:

- new residential areas,

- areas of modernized farms and village buildings,

- areas of new network infrastructure investments: road, energy, etc.,

- areas of large-size service and industrial buildings,

- areas of industry agriculture, and

- areas of tourist activity.

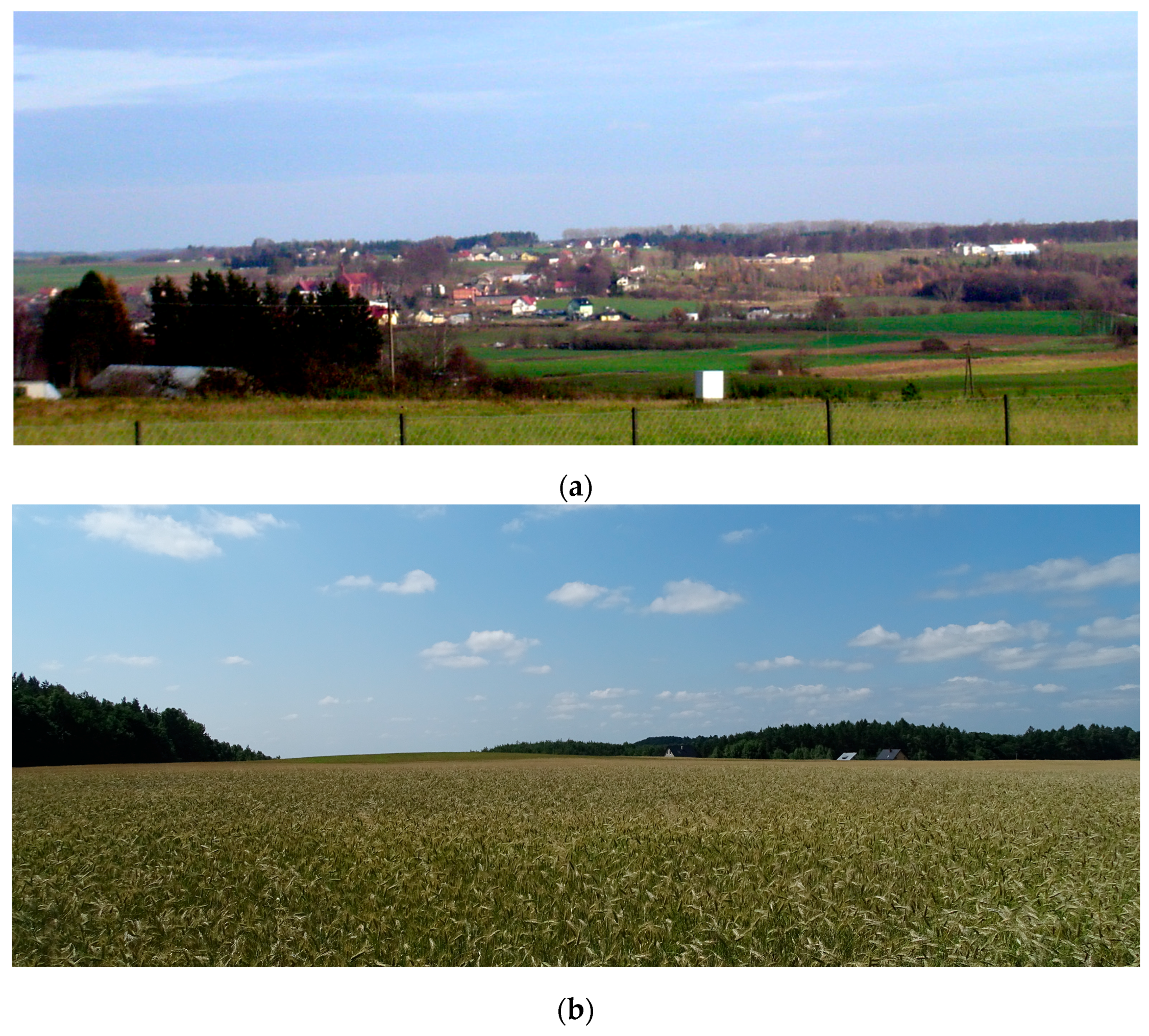

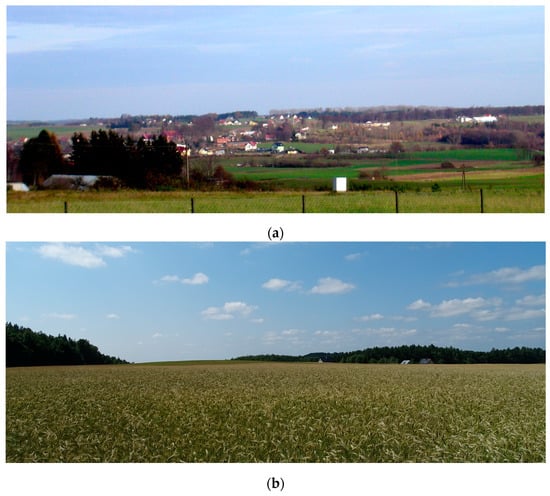

New residential areas usually take the form of a roadside or a so-called field-type development (Figure 1), whose layout is managed by the existing ownership division of agricultural land that is reclassified for building areas, excluding previous merger and subsequent parceling. Small, one-family plots of land, which are usually marked on flat plains in the arrangement of “chocolate bars”, are developed in different periods of time or remain empty, which gives the effect of a visual dispersion. It is aggravated by the absence of ordering elements in the form of dominants, and the lack of tall trees (excluded due to small plot areas) and shrubs as a binding background. As a result, a typical feature of the composition of the contemporary view is “noisy” disorder and an extreme dissimilarity of forms or, on the contrary, their excessive uniformity in the absence of a hierarchy of motives. Landscapes of transformed rural settlements have an amorphous character (Figure 2a). The forms of the traditional agricultural village, on the contrary, were spatially organized: the village had a clear boundary; buildings with low intensity focused on the street or square, and there was greenery on the border of the house; it was surrounded by agricultural lands, which constituted a vast foreground for the view exhibition (Figure 2b). The preserved rural image determines the cultural identity, legal protection, or tourist attractiveness of the places today [42,43].

Figure 1.

“Field-type” urbanization of rural areas, Szpęgawa, Pomeranian voivodeship, from the Pomeranian Agricultural Advisory Centre (Pomorski Ośrodek Doradztwa Rolniczego) collection.

Figure 2.

The examples of village panoramas in the Pomeranian voivodeship, (a) the landscape of rural sprawl, (b) agricultural landscape; private collection.

Significant visual changes are also observed within the old habitats of the village (Figure 3). New buildings are developed with a suburban, universal style. The building modernization process is underway, and as a result, the old buildings lose their local character. The development of housing plots and farmsteads is also transformed, for example: courtyards, roadsides, walkways, and commuting roads are paved (mainly with colored paving stones). Colorful flower or ornamental gardens, local species of shrubs, or vegetable gardens give way to mowed lawns and popular artifacts (such as garden figurines or old farm equipment) and factory elements of small architecture (such as concrete fences and fountains or lighting elements). Thus, the identifying features in the form of local vegetation disappear from the village landscape. At the same time, the spread of impermeable surfaces causes an accelerated outflow of surface waters, which disturbs the hydrological balance.

Figure 3.

Two different kinds of the village public spaces, (a) traditional character of Ciechocin public space, (b) urban character of Koszwały public space, Pomeranian voivodeship; private collection.

The rural sprawl forces local governments to invest in network infrastructure. Even in areas that are unlikely to be completely developed in the foreseeable future, the law requires access roads, water and sewage systems, energy and internet connections, and the possibility of waste disposal. Roadside tree-cutting is justified by safety requirements. Along with the trees, the stunning views of green tunnels or leafy canopies disappear. The same happens to windbreaks, the biotopes of many animal species, and natural regulators of groundwater levels.

In the case of road and energy investments of supralocal importance, the visual effect of their scale is significant: sometimes, the multikilometer band of the acoustic screen overrides the horizon, the wide highway band crosses landscape interiors at the level of sight, or rows of high-voltage power poles or wind farms completely change the dynamics of the agricultural landscape. Large farm service buildings, silos, or large-scale industrial facilities also appear in agricultural areas. The linear forms of the new technical infrastructure divide the so-far homogenous meadows and agricultural crops, and new vertical forms become features or dominants that are different than the traditional ones such as church towers or the chimneys of old brickyards and distilleries (Figure 4). A new investment is often associated with, i.a. increasing air pollution and noise level, interrupting the continuity of ecological corridors, or reducing the biodiversity or productivity of agricultural land.

Figure 4.

The foreground feature and new dominant in the village panorama, Kamień Śląski, Opole voivodeship; private collection.

Monoculture is a system of industry agriculture. Intensive agricultural production usually enforces the removal of picturesque mid-field greenery, whose compositional function is based, for example, on defining the sequences of landscape interiors, or creating curtains, backstops, viewing closures, or accents in the form of individual trees. Cutting trees and shrubs causes a reduction of the positive aesthetic experiences of the observer (Figure 5). It also means the elimination of bird depots and ecological sites, which are valuable areas of biodiversity, as well as the reduction of wind power and the protection of soil from sterilization.

Figure 5.

Buildings in intensive agriculture, Koszwały, Pomeranian voivodeship, private collection.

Tourism is becoming an increasingly important element of the rural economy today. Therefore, the number and variety of attractions and accommodation bases are growing (Figure 6). The form of rural tourism playing a dual role, which was unknown in Poland before 1990, is the concept of so-called amusement parks or holiday villages that also offer many forms of mass recreation and hotel services. They usually have a main theme, which is similar to the so-called thematic villages. The latter represent a way to activate the local economy. Popular themes refer to local products or legends, reflect fantasies, and usually do not refer to the physiognomic features of the surroundings. This decides their visual distinction from the landscape background.

Figure 6.

Rural tourism attractions: (a) the thematic village, Gogolewko Sunflower Village, West Pomeranian voivodeship; (b) the amusement park in Szymbark, Pomeranian voivodeship; private collection.

Rural tourism infrastructure is permanently constituted by family farms in agrotourism, guest houses, large hotel and conference centers, second homes, and holiday cottages, which are usually of an architecture that is deprived of local features or with exaggerated regional forms, and restored manor park complexes. The hotel accommodation base is often complemented by substandard temporary buildings in the form of sheds, gazebos, and caravans (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Fixed substandard tourist development, Karwieńskie Błota II, Pomeranian voivodeship, (a) the view of a divided long meadow; (b) the present cadastral map, www.geoportal.gov.pl, readable division process of protected long meadows; private collection.

Their assumed, temporary nature sometimes becomes fixed. This process occurs when fields or meadows with building prohibition are irreversibly divided into small recreational plots, where the shanties are placed (Figure 7b). Mass tourism development in many of the most attractive areas has already led to their exceeded absorption, i.e., to the inability of the natural environment to regenerate as a result of an excessive usage load.

The presented description was directed to indicate only general relations between the destruction of visual and ecological environmental resources. However, it demonstrates the prevailing low culture of shaping rural areas clearly enough. Its increase is one of the most important tasks of the pro-landscape spatial policy in Poland. First of all, it depends on developing the research on local landscape units, and then on popularizing their results.

3. The Legal Status and Effectiveness of Landscape Protection

Landscape protection in Poland is not treated separately, yet it is implemented as a part of nature protection and cultural heritage (Table 1). The Act on Nature Conservation of 16 April 2004 established 10 forms of nature protection [44]. Next to the species protection of plants, animals, and fungi, these are national parks, nature reserves, landscape parks, protected landscape areas, Natura 2000 areas, ecological sites, natural monuments, documentary sites, and natural and landscape complexes. The basic legal act regulating the principles of monument protection and taking care of them is the Act of 23 July 2003 on the protection of monuments and the care of monuments (Journal of Laws of 2003, No. 162, item 1568 with further amendments) [45]. The Act introduced four forms of material heritage protection: entry into the register of monuments, historical monument recognition, creation of a cultural park, and establishing protection in a local spatial development plan or in a decision on development conditions. Areas under statutory protection in Poland, i.e., national parks, landscape parks, historical monuments, and relics cover about 10% of the country’s area. In the remaining 90% of the area, the landscape is shaped by local development plans, which are managed by territorial self-governments. The rules for their preparation and adoption are regulated by the Act on spatial planning and development of 27 March 2003, with further amendments [46]. Local plans, and in their absence, decisions on development conditions that are issued based on the principle of neighborliness, are the only legal and administrative tools for shaping space in the whole country. Local governments are not obliged to pass a plan for the whole commune. The rule is the temporal and territorial separation of various plans. Covering the country’s area with local development plans has been kept at a very low level for years, and currently does not exceed 30%, with the lowest in rural communes [47]. Studies of spatial development conditions and directions of communes are pictured by higher-level plans. They reflect principles that are established in the concept of the spatial development of the country, as well as in the development strategy and the voivodeship spatial development plan. The study of spatial development conditions and directions is binding for the commune authorities when drawing up local plans, but it is not a local law act. In 2001, the legislator introduced the obligation to prepare environmental impact assessments into the procedure of adopting local plans, and entrusted it to investors. By 2015, regardless of their competences, anyone could be the author of the assessment or report on the project impact on the environment.

Table 1.

The most important current legal acts related to the landscape protection.

Over the last 30 years of nature protection functioning, many landscape parks and areas of protected landscape have gradually lost the values that were their foundation. At the same time, the quality of common landscapes is threatened by the ongoing process of development scattering. Both phenomena are favored by the spatial planning system, and its rigor is apparent [48]. With low respect for law in Poland and the low prestige of spatial values, the applicable regulations favor discretion and abuse. Commune officials are easily influenced by investors. Increasing the ground rent income to the municipal budget or raised funds are sufficient arguments to designate new land for development. The pretext for such decisions could be unreliable studies of spatial development conditions and directions, which are based on unrealistic demographic assumptions. The quality of developing local plans is often equally low, and building conditions are created with violation of the studies. The texts of plans refer to the “neighborliness” principle, which is to imitate neighborhood forms, even in undeveloped areas.

Poland ratified the European Landscape Convention (ELC) on 27 September 2004 (Journal of Laws No. 14, item 98), i.e., only four years after it was drawn up in Florence [49]. The ELC provisions were incorporated into national law through the so-called landscape law, whose full name is the Act of 24 April 2015 on the amendment of certain acts regarding the enhancement of landscape protection tools [50]. It defined the landscape on the basis of the ELC record as “space perceived by people, containing natural elements or products of civilization, established as a result of natural factors or human activity”. The Act introduced two completely new solutions. Communes obtained the right to pass the so-called advertising codes, which aimed to determine the principles of location and forms of advertising, as well as elements of small architecture. The second novelty is the landscape audit procedure. The obligation of audit implementation is the realization of the ELC postulates regarding the identification, description, and assessment of landscapes. The audit procedure will be carried out once every 20 years by the voivodeship board. Its purpose is to identify landscapes and highlight the so-called priority landscapes, i.e., landscapes that are “especially valuable for society due to their natural, cultural, historical, or aesthetic and scenic values, and as such requiring preservation” [50]. The recommendations and conclusions that have been included in the audit must be taken into consideration when drawing up voivodeship spatial development plans; however, they do not translate directly into legal and administrative decisions in the Polish planning system. The legislator provided three years for the adoption of a regulation that would define audit rules, and the next three years for its preparation (such regulation had not been published by the time the author finished the article). At the request of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, in 2014, a team of geographers developed methodological assumptions and instructions for conducting a landscape audit [51]. In 2017, the Association of Polish Landscape Architects listed recommendations for landscape analyses that aimed to determine the landscape protection zones [52]. None of these studies proposed a comprehensive, coherent, and uncomplicated method of assessing visual values of the landscape, which would be easy to apply in the spatial planning of rural communes. The landscape law does not deeply rebuild the legal system of spatial management. However, the requirement to identify landscapes is an appropriate starting point for its further changes. The act does not propose tools that could include the results of landscapes identification and an assessment of spatial planning. Furthermore, its current regulations will make it difficult to introduce them in the future.

A landscape audit is to be carried out top–down. Audit conclusions, confirmed at the level of regional planning, are not binding for local planning. The announced statutory identification and description of local landscape areas, including priority landscapes, are not of a continuous and participatory nature. The legislator does not predict the specification at the local level. In addition, the 20-year period of the audit in the era of accelerated changes and without a monitoring procedure means that its content becomes quickly outdated. Another disadvantage of the audit is the combination of the identification and description of landscapes with their valorization. The only practical task of the audit indicated by the legislator is to protect the identified landscapes of unique values. The act does not define other landscape management tools except for the advertising code. Due to the indicated systemic defects, in conditions of a low level of respect for the law, citizenship, and awareness of threats, the effect of the landscape law will not be an increase in the effectiveness of the protection of high landscape values; instead, it will deepen local contradictions and preserve irregularities in space planning and management, as well as further degrade the spatial order and consolidate attitudes ignoring the social value of common landscapes. Therefore, it is necessary to further reform the spatial planning system by extending landscape management procedures.

4. Assumptions and Tools of the Landscape Policy. Recommendations

The landscape policy is of fundamental importance for the restoration of the spatial order in rural areas, as it leads to the social readability of dispersed environmental and cultural threats. From the perspective of landscape policy, spatial planning is a communication process, where different actors strive to agree on solutions. Mediation is carried by the language, but it is also represented by the view and image of the area. Visual perception and imaginations affect individual spatial decisions [56,57,58]. Their universality determines the strength of its impact on the environment and landscape. Therefore, the inclusion of landscape’s visual dimension in spatial planning is necessary to sustainable space managing.

The acquired knowledge and imaginations of the place allow assessing its view. Critical observation resulting from the strong sense of territorial identity allows individuals to recognize the threat and get involved in the process of its liquidation. Perception, and in particular visual perception, gives the landscape the rank of a specific interface: a switch between the environment and the activity of its users [59]. It is primarily the viewed image that saves the connection between the elements and relations of the environment and their social value in memory and imagination. The view and vision of the surroundings constitute a space for mediation between the real surroundings and the importance given by its users. This is why managing the visual dimension of the landscape is important for the shaping of spatial order [60,61].

The collective imagination, which consists of the popular knowledge of citizens, as well as their views, convictions, and associations, is a no less important prerequisite for maintaining spatial order than legal norms or expert knowledge [62]. The collective imagination is an important tool for the social shaping of reality, because imaginations have the power to modernize views and expectations, and thus initiate changes in space. Thus, the effective protection of environmental resources requires creating opinions, behaviors, and collective ideas that will give meaning to observations. This process takes place during the discourse in the public field: in the press, in traditional television, in digital media, in the education process, and represents the mission of the landscape policy. Currently, the problem of the landscape in Poland has been limited to the issue of visual noise caused by excess and the disorder of advertisements in public space [63]. Moreover, the concept of the landscape appears in tourist offers and food advertisements. Outside the university walls, the landscape that reflects the quality of the environment and life is not spotted at all. There has been no scientific basis for creating landscape discourse in Poland yet. It is necessary to indicate the actors of public dialogue, as well as determine their knowledge, and the “field of visibility” [23] of the arguments. This type of analysis would allow assessing the real potential of the public field in the field of shaping opinions about the landscape and identifying the channels of communication that would have made it possible to change the collective beliefs that are currently destructive to the spatial order.

Collective knowledge on the relationship between the visual quality of the landscape and the quality of life, as well as the social commitment to protect the aesthetic value of the surroundings, constitutes the superstructure of landscape policy. Its operating base is represented by the visual landscape management procedures that have been developed for local landscape units. The municipal agenda of the local landscape management should be a basic legal instrument. It would define problems and indicate how to combine visual landscape qualities with the protection of environment and cultural resources. The municipal landscape plan would be another tool. It would ensure the coherence of all of the local development plans and help create the spatial order. It could also introduce prohibition zones due to visual values and indicate the implementation of corrective or compensatory treatments. Building permits should depend on the assessment of the visual impact of the object on the landscape. Each commune should have a report on the visual quality assessment of the area, which would clearly indicate the relationship between local landscape forms and features of the cultural and natural environment. The report would also play an educational and promotional role; hence, it is important to be legible and richly illustrated. The landscape report could provide guidance for communal strategies and programs, as well as landscape design plans.

The selection of operating indicators and methods of assessing the visual impact of local landscapes are of fundamental importance to the effectiveness of the landscape policy [64,65]. We are still at the beginning of the process: landscapes have been not defined yet, and studies on the visual criteria of cohesion in spatial planning and management are dispersed [66,67,68,69]. What methods should be used? Should one of the foreign methods be adapted, or would it be better to develop known Polish ones? What indicators should be chosen? How do we assess complex indicators such as homeliness or identity? How do we assess visibility? Should the landscape assessment be descriptive, or should relative measures be used for indicators of comparability? Is it appropriate to limit the landscape evaluation to an expert opinion? How do we ensure participation in landscape assessment? The creation of a methodological framework for landscape impact assessment in Poland requires many decisions that have to take into account the results of future local landscape surveys.

5. Conclusions

Sustainable development is the declared mission of the spatial policy strategy in Poland at all levels of planning and management [70]. However, the official goal is defeated by the pragmatic decisions of local governments and residents, who perceive economic and technological growth as the synonym for development (such as setting new investment areas, their utilities, road construction, or intensive agricultural production). They are often accompanied by ecological imbalance or cultural heritage degradation, and are always followed by visual changes that are not yet perceived as threatening by the local community.

In Poland, spatial planning does not have a strong landscape component, and the socialization of the planning system is usually formal and sketchy. Landscape issues, and rural landscape ones in particular, are located on the periphery of spatial planning. The interdependence of changes in the physiognomy of the environment and the quality of its objective parameters and living conditions is currently not obvious to neither creators of local law nor space users. The exploration of these compounds is fundamental in conditions of spatial order erosion. The explanation of the environmental, economic, and cultural sense of visual transformations would contribute to harmonizing social contradictions. This process should be completed within landscape policy, whose mission is to create a high value of landscapes and result in spatial order. A landscape-oriented policy, operating within public education and the market, as well as the planning system, would support the effectiveness of future local landscape management tools and procedures. Only their reliability will lead to the restoration of spatial order in a large part of the rural territory of Poland. The poor knowledge of the visual quality of local landscapes and binding law are the main obstacles to be overcome on the path to change.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Population. Condition, Structure and Natural Movement in the Territorial Profile in 2017. Central Statistical Office: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-stan-i-struktura-oraz-ruch-naturalny-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-w-2017-r-stan-w-dniu-31-xii,6,23.html (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Bański, J. Polish Coutryside in a 2050 Perspective. Rural Studies, t. 33; PTG; PAN IGiPZ: Warszawa, Poland, 2013; Available online: http://rcin.org.pl/igipz/dlibra/docmetadata?id=33921&from=publication (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Population Forecast for 2014–2050. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/.../pl/.../prognoza_ludnosci_na_lata____2014_-_2050.pgf (accessed on 2 May 2018).

- Wilkin, J.; Nurzyńska, I. (Eds.) Polish Counryside 2018. The Report on Coutryside Condition (Polska Wieś 2018. Raport o Stanie Wsi), 1st ed.; Scientific Publishers Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-983-7383-953-3. Available online: http://www.fdpa.org.pl/uploads/downloader/Wies2018.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2018).

- Kowalewski, A.; Markowski, T.; Śleszyński, P. (Eds.) Studies of the Spatial Development Committee of the Country Polish Academy of Sciences No. 182; Studies on Spatial Chaos Vol. II. Costs of Spatial Chaos; Polska Akademia Nauk Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; ISSN 0079-3493. Available online: http://journals.pan.pl/dlibra/journal/123401 (accessed on 26 June 2018).

- Hałasiewicz, A. Rural Development in the Context of Spatial Diversity in Poland and Building Territorial Cohesion of the Country (Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich w Kontekście Zróżnicowań Przestrzennych w Polscei Budowania Spójności Terytorialnej Kraju); MRR: Warszawa, Poland; Ministry of Agricultural Development: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; Available online: http://www.mrr.pl/rozwoj_regionalny/Ewolucja_i_analizy/Raporty_o_rozwoju/Raporty_krajowe/Documents/Ekspertyza_Rozwoj_%20obszarow_wiejskich_09082011.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2013).

- Heffner, K. Space as a Determinant of Rural Development in Poland. Countrys. Agric. 2015, 2, 83–101. Available online: http://kwartalnik.irwirpan.waw.pl/dir_upload/photo/552694791a9d165a36793dd62e27.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2016).

- Kowalewski, A.; Mordasewicz, J.; Osiatyński, J.; Regulski, J.; Stępień, J.; Śleszyński, P. Report about Economic Losses and Social Costs of Uncontrolled Urbanization in Poland—Working Project on Manuscript Rights Version of 1 October 2013 (Raport o Ekonomicznych Stratach i Społecznych Kosztach Niekontrolowanej Urbanizacji w Polsce). Unpublished. Available online: http://odpowiedzialnybiznes.pl/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Raport-Ekonomiczny-29.10.2013-calosc.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2015).

- Kistowski, M. Problems of Sustainable Development of Rural Areas—Between Flourishing, Periferisation and Degradation. In How to Ensure Sustainable Development of Open Areas? 1st ed.; Kamieniecka, J., Jacki, F., Wójcik, B., Eds.; Instytut na rzecz Ekorozwoju: Warsaw, Poland, 2009; pp. 6–17. ISBN 978-983-7556-216-3. Available online: http://www.kgfiks.oig.ug.edu.pl/mk/kistowski_b_3_7.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2011).

- Górka, A. Local Development Strategies in Shaping Rural Landscape. In Contemporary Rural Landscapes, 1st ed.; Cielątkowska, R., Poczobut, J., Eds.; University of Environmental Management in Tuchola: Tuchola, Poland, 2011; pp. 65–71. ISBN 978-83-924457-6-0. [Google Scholar]

- Leder, A. Prześniona Rewolucja. Ćwiczenia z Logiki Historycznej, 1st ed.; Publishing House of Krytyka Polityczna: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; ISBN 9788363855611. [Google Scholar]

- Król, M. Byliśmy Głupi, 1st ed.; Czerwone&Czarne Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; ISBN 9788377001929. [Google Scholar]

- The Constitution of the Republic of Poland Art. 5. Available online: www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/polski/kon1.htm (accessed on 26 January 2017).

- Assmann, A. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-521-16587-7. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory, 1st ed.; Polish Scientific Publishing PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2008; ISBN 9788301155117. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin, J. On the Need and Principles of Creating a Vision for the Development of the Polish Countryside (O Potrzebie i Zasadach Tworzenia Wizji Rozwoju Polskiej Wsi). In Polish Countryside 2025. Vision of Development (Polska Wieś 2025. Wizja Rozwoju), 1st ed.; Wilkin, J., Ed.; Fundusz Współpracy: Warszawa, Poland, 2005; pp. 9–14. ISBN 83-89793-95-4. Available online: http://witrynawiejska.org.pl/data/Polska%20wies%202025.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Górka, A. Rural Landscape as Collective Project (Krajobraz WiejskiJako Projekt Zbiorowy). Studia Obszarów Wiejskich, No 48; Determinants of Rural Renewal and Revitalization Processes in Poland (Uwarunkowania Procesów Odnowy i Rewitalizacji Wsi w Polsce); PAN IGiPZ; PTG: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; pp. 21–30. ISSN 1642-4689. Available online: http://rcin.org.pl/Content/65998/WA51_85006_r2017-t48_SOW-Gorka.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2018).

- Górka, A. About Useful Vision of the Village (O Użytecznej Wizji Wsi). In In the Countryside, or Where? Architecture. Environment. Society. Economics of the Contemporary Village. Region. City. Village. (Na Wsi, Czyli Gdzie? Architektura. Środowisko. Społeczeństwo. Ekonomia Współczesnej Wsi. Region. Miasto. Wieś), 1st ed.; Gasidło, K., Twardoch, A., Eds.; The Silesian Technical University Publishing House: Gliwice, Poland, 2017; pp. 84–97. ISBN 978-983-7880-495-6. Available online: http://repolis.bg.polsl.pl/Content/44423/BCPS_48722_2017_Na-wsi-czyli-gdzie--_0000.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- De Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life, 1st ed.; Jagiellonian University Press: Cracow, Poland, 2008; ISBN 978-983-233-2597-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sztompka, P. Social Capital. Theory of Interpersonal Space (Kapitał Społeczny. Teoria Przestrzeni Międzyludzkiej), 1st ed.; Znak Publishing House: Cracow, Poland, 2016; pp. 279–331. ISBN 978-983-240-3460-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nacher, A. Lacating Media: The Hidden Life of Images (Media Lokacyjne: Ukryte Życie Obrazów), 1st ed.; Jagiellonian University Press: Cracow, Poland, 2016; ISBN 978-983-233-4074-4. [Google Scholar]

- Różak, J. Energy policy in the context of the New Public Management. Proposals for Poland. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie Sklodowska 2011, 18, 37–51. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269868757_Energy_policy_in_the_context_of_the_New_Public_Management_Proposals_for_Poland (accessed on 25 April 2018). [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. Media energy discourse as an object of sociological reflection (Medialny dyskurs energetyczny jako przedmiot refleksji socjologicznej). In Visible and Invisible: Atom, Shale, Wind in Media Discourses around the Energy Sector (Widocznei Niewidoczne: Atom, Łupki, Wiatr w Dyskursach Medialnych Wokół Energetyki), 1st ed.; Wagner, A., Ed.; Jagiellonian University Press: Cracow, Poland, 2016; pp. 11–28. ISBN 978-983-233-4115-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski, K.H. Pro-Landcsape Tools of Planning in France, Belgium, Spain and Portugal (Pro-Krajobrazowe Instrumenty Planistyczne We Francji, Belgii, Hiszpanii i Portugalii). Tech. J. Archit. 2008, 171–179. Available online: http://suw.biblos.pk.edu.pl/search&query=Wojciechowski%20Krzysztof&termId=1,2,7 (accessed on 8 July 2018).

- Tetlow, R.J.; Sheppard, S.R.J. Visual Unit Analysis: A Descriptive Approach to Landscape Assessment. In Proceedings of the Our National Landscape: A Conference on Applied Techniques for Analysis and Management of the Visual Resource, Incline Village, NV, USA, 23–25 April 1979; Elsner, G.H., Smardon, R.C., Eds.; Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-35; Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Exp. Stn., Forest Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture: Incline Village, NV, USA, 1979; pp. 117–124. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/27565 (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Fairhirst, K. Visual Landscape System for Planning and Managing Aesthetic Resource; Cumulative Environmental Management Associations: Fort McMurray, AB, Canada, 2002; Available online: http://library.cemaonline.ca/ckan/dataset/2002-0008 (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Visual Landscape Planning in Western Australia. A Manual for Evaluation, Assessment, Siting and Design; Western Australian Planning Commission, Albert Facey House: Pert, Australia, 2007; ISBN 0-7309-9637-9. Available online: https://www.planning.wa.gov.au/publications/1205.aspx (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Orzechowska-Szajda, I. Landscape Protection Systems in Environmental Impact Assessments in Different Countries. Methodological Approach. Similarities and Differences (Systemy Ochrony Krajobrazu w Ocenach Oddziaływania na Środowisko w Różnych Krajach. Ujęcie Metodologiczne. Podobieństwa i różnice). Proceedings 20.04.2018, Project of Provincial Environmental Protection and Water Management Fund in Gdansk No. RV-4/2018: Landscape Protection in Environmental Impact Assessments in the Light of Contemporary Legal and Methodological Conditions (Ochrona Krajobrazu w Ocenach Oddziaływania na Środowisko w Świetle Współczesnych Uwarunkowań Prawno-Metodologicznych). Available online: https://arch.pg.edu.pl/ochrona-krajobrazu-w-ocenach-oddzialywania-na-srodowisko-w-swietle-wspolczesnych-uwarunkowan-prawno-metodologicznych (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- European Landscape Character Areas. Typologies, Cartography and Indicators for the Assessment of Sustainable Landscapes, Final Project Report Project: FP5 EU Accompanying Measure Contract: ELCAI-EVK2-CT-2002-80021, Co-Ordinator: Wascher, D. Available online: www.library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/1778 (accessed on 3 February 2018).

- Majchrowska, A. Systematisation of Landscapes in Selected European Countries (Systematyzacja Krajobrazów w Wybranych Krajach Europejskich). Probl. Landsc. Ecol. 2008, 127–134. Available online: http://www.paek.ukw.edu.pl/wydaw/vol20/majchrowska_systematyzacja_krajobrazow.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Swanwick, C. Landscape Character Assessment: Guidance for England and Scotland; Countryside Agency, Scottish Natural Heritage: Cheltenham/Edinburgh, UK, 2002; Available online: http://www.snh.org.uk/pdfs/publications/LCA/LCA.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Bishop, K.; Phillips, A. (Eds.) Countryside Planning: New Approaches to Management and Conservation; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 109–122. ISBN 1136568697. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski, T.J.; Śleszyński, P.; Chmielewski, S.Z.; Kułak, A. Aesthetic Costs of Spatial Chaos (Estetyczne Koszty Chaosu Przestrzennego); Studies of the Spatial Development Committee of the Country Polish Academy of Sciences 2018 No 182, Studies on Spatial Chaos Vol. II. Costs of Spatial Chaos; Polska Akademia Nauk Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 365–403. Available online: http://journals.pan.pl/dlibra/publication/123415/edition/107644/content (accessed on 26 June 2018).

- Lipińska, B. Protection of Cultural Heritage: Landscape Approach (Ochrona Dziedzictwa Kulturowego: Ujęcie Krajobrazowe), 1st ed.; Department of Gdańsk University of Technology: Gdańsk, Poland, 2011; ISBN 978-983-928905-6-0. [Google Scholar]

- Raszeja, E. Landscape Protection in the Process of Rural Areas Transformation (Ochrona Krajobrazu w Procesie Przekształceń Obszarów Wiejskich), 1st ed.; Publishing House of Poznań University of Life Science: Poznań, Poland, 2013; ISBN 978-983-7160-820-9. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiecka-Filipiak, I. Distinctions of the Landscape and Architecture of the Villages of South-Western Poland (Wyróżniki Krajobrazu i Architektury wsi Polski Południowo-Zachodniej), 1st ed.; Publishin House of the University of Life Sciences in Wrocław: Wrocław, Poland, 2009; ISBN 978-83-60574-71-3. Available online: https://fbc.pionier.net.pl/details/nnf9pX5 (accessed on 1 May 2018).

- Kistowski, M.; Lipińska, B.; Korwel-Lejkowska, B. Values, Threats and Proposals for the Protection of Landscape Resources of the Pomeranian Voivodeship. Part 2. (Walory, Zagrożenia i Propozycje Ochrony Zasobów Krajobrazowych Województwa Pomorskiego); Project of the Pomeranian Voivodeship Government No. UM/DRRP/114/05/D; The Pomeranian Voivodeship Government: Gdańsk, Poland, 2005; Available online: http://www.kgfiks.oig.ug.edu.pl/mk/kistowski_lipinska_korwel_b_4_9.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Górka, A.; Lipińska, B.; Rayss, J. Guide of Landscaping for Pomerania. Vol. I. Landscapes of the Vistula Valley and Delta (Przewodnik Kształtowania Pomorskich Krajobrazów. Cz. I. Krajobrazy Doliny i Delty Wisły), 1st ed.; Pomeranian Marshal Office: Gdańsk, Poland, 2012; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joanna_Rayss/publication/265422041 (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- Górka, A.; Rayss, J. Guide of Landscaping for Pomerania. Vol. II. Seaside Landscapes (Przewodnik Kształtowania Pomorskich Krajobrazów. Cz. II. Krajobrazy Nadmorskie), 1st ed.; Pomeranian Marshal Office: Gdańsk, Poland, 2012; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joanna_Rayss/publication/265422217 (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- Górka, A. Threats to the Rural Landscape in Spatial-Physiognomic Terms (Zagrożenia Krajobrazu Wiejskiego w Ujęciu Przestrzenno-Fizjonomicznym). Proceedings 20.04.2018, Project of Provincial Environmental Protection and Water Management Fund in Gdansk No. RV-4/2018: Landscape Protection in Environmental Impact Assessments in the Light of Contemporary Legal and Methodological Conditions (Ochrona Krajobrazu w Ocenach Oddziaływania na Środowisko w Świetle Współczesnych Uwarunkowań Prawno-Metodologicznych). Available online: https://arch.pg.edu.pl/ochrona-krajobrazu-w-ocenach-oddzialywania-na-srodowisko-w-swietle-wspolczesnych-uwarunkowan-prawno-metodologicznych (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Chmielewski, T.J.; Chmielewski, S.Z.; Kułak, A. The Influence of Spatial Disorder on Landscape Ecological Systems (Wpływ Bezładu Przestrzennego na Krajobrazowe Systemy Ekologiczne). Studies of the Spatial Development Committee of the Country Polish Academy of Sciences 2018, No. 182, Studies on Spatial Chaos Vol. II. Costs of Spatial Chaos; Polska Akademia Nauk Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 317–340. Available online: http://journals.pan.pl/dlibra/publication/123413/edition/107642/content (accessed on 26 May 2018).

- Myczkowski, Z. Landscape as the Expression of Identity in Selected Areas under Protection in Poland (Krajobraz Wyrazem Tożsamości w Wybranych Obszarach Chronionych w Polsce), 2nd ed.; Monographs of Cracov University of Technology, Architecture Series 2003, No. 285; Cracov University of Technoloy: Cracov, Poland, 2003; ISSN 0860-097X. [Google Scholar]

- Mika, M. Tourism as a Factor in the Transformation of the Natural Environment—The State of Research (Turystyka Jako Czynnik Przemian Środowiska Przyrodniczego—Stan Badań). Prace i Studia Geograficzne (Jagiellonian University) 2000, 73–98. Available online: http://www.pg.geo.uj.edu.pl/documents/3189230/4676052/2000_106_73-98.pdf/c06cee5d-f4cc-425f-be55-c1b5141e143d (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- The Act on Nature Conservation of 16 April 2004. Available online: http://www.prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20040920880 (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- The Act on the Protection of Monuments and the Care of Monuments of 23 July 2003. Available online: www.isap.sejm.gov.pl/Download?id=WDU20031621568&type=3 (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- The Act on Spatial Development of 27 March 2003. Available online: www.prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20030800717 (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- Prus, B. Local Planning in Poland—Comparative Study. Infrastructure and Ecology of Rural Areas 2012, 2/II. pp. 123–135. Available online: http://www.infraeco.pl/pl/art/a_16825.htm (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Böhm, A. Effectiveness of Legal Instruments Existing in Poland. Tech. J. Archit. 2008, 105, 137–146. Available online: http://suw.biblos.pk.edu.pl/resourceDetails&rId=829 (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- European Landscape Convention. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680080621/ (accessed on 5 March 2010).

- Act on Amendment of Certain Acts Regarding the Enhancement of Landscape Protection Tools of 24 April 2015. Available online: www.prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20150000774 (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- Solon, J.; Plit, J.; Kistowski, M.; Milewski, P. (Eds.) Methodology of Landscape Identification and Assessment. PAN IGiPZK: 5 December 2014 Version. Available online: http://www.gdos.gov.pl/metodyka-identyfikacji-i-oceny-krajobrazu (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Niedźwiecka-Filipiak, I.; Ozimek, P.; Akincza, M.; Kochel, L.; Krug, D.; Sobota, M.; Tokarczyk-Dorociak, K. Recommendations in the field of landscape analysis for the purposes of designating landscape protection zones commissioned by the General Directorate for Environmental Protection. 2017. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- The Act on Sharing Information about the Environment and its Protection, Public Participation in Environmental Protection, and Environmental Impact Assessments of 3 October 2008. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20081991227 (accessed on 25 September 2008).

- The Act on Revitalization of 9 October 2015. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20150001777 (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- The Act on Facilitating of the Preparation and Implementation of Housing and Accompanying Investments. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180001496 (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- Arnheim, R. Art and Visual Perception. The Psychology of Creative Eye. New Version, 50th ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-520-2483-8. [Google Scholar]

- Berleant, A. Aesthetics and Environment, 1st ed.; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; ISBN 1566393345. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, A. Aesthetics and the Environment. The Appreciation of Nature, Art and Architecture, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 041530105X. [Google Scholar]

- Palang, H.; Fry, G. Landscape interfaces. In Landscape Interfaces: Cultural Heritage in Changing Landscape, 1st ed.; Palang, H., Fry, G., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–13. ISBN 1-4020-1437-6. [Google Scholar]

- Berleant, A. Living in the Landscape: Toward an Aesthetics of Environment, 1st ed.; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1997; ISBN 0700608117. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment, 1st ed.; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125. ISBN 978-1-4613-3541-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1991; ISBN 978-0-631-18177-4. [Google Scholar]

- Visual Chaos. MPGA 11. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JhG2e1BOyrA (accessed on 10 February 2018).

- Ode, A.; Tveit, M.S.; Fry, G. Capturing Landscape Visual Character Using Indicators: Touching Base with Landscape Aesthetic Theory. Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 89–117. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01426390701773854?needAccess=true (accessed on 17 August 2018). [CrossRef]

- Simensen, T.; Halvorsen, R.; Eriksad, L. Methods for landscape characterisation and mapping: A systematic review. Land Use Policy 2008, 75, 557–569. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837717314072?via%3Dihub (accessed on 17 August 2018). [CrossRef]

- Balon, J.; Jodłowski, M. (Eds.) The Landscape Ecology—Research and Usage Aspects; Polska Asocjacja Ekologii Krajobrazu, Jagiellonian University: Cracov, Poland, 2009; Volume 23, ISBN 978-983-88424-30-4. Available online: http://www.paek.ukw.edu.pl/wydaw/vol23/vol_23.htm (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- Myga-Piątek, U.; Chmielewski, T.J.; Solon, J. The Role of Characteristic Features, Landmarks and Determinants in Classification and Audit of the Current Landscapes (Rola Cech Charakterystycznych, Wyróżników i Wyznaczników Krajobrazu w Klasyfikacji i Audycie Krajobrazów Aktualnych). Probl. Landsc. Ecol. 2015, 40, 177–185. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292655966 (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Chmielewski, T.J.; Butler, A.; Kułak, A.; Chmielewski, S.Z. Landscape’s physiognomic structure: Conceptual development and practical applications. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 410–427, Pre-Print Version Published in April 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316445637_Landscape’s_physiognomic_structure_conceptual_development_and_practical_applications (accessed on 17 August 2018). [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiecka-Filipiak, I. Walory Miejscowości—Tworzywem Sieci Najciekawszych wsi, 1st ed.; Marshal Office of Opole Voivodeship: Opole, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-983-64950-68-1. [Google Scholar]

- The Concept of the Spatial Development of the Country until 2030. Resolution No. 239 of the Council of Ministers of December 13, 2011 Regarding the Adoption of the National Spatial Development Concept 2030. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WMP20120000252 (accessed on 21 March 2017).

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).