Abstract

Cellulose has received significant attention, given its high demand for the transition to sustainable fuels and renewable energy, addressing the environmental challenges of fossil fuels. Fast pyrolysis is a process that can transform cellulose into bio-oil. Although the bio-oils produced contain considerable amounts of oxygen and water, they are highly corrosive and highly viscous, which limits their utility as biofuels. Pyrolysis bio-oils require upgrading to remove oxygen and corrosive components, thereby enhancing their stability for use as biofuels and their environmental sustainability. This study investigates the catalytic pyrolysis of cellulose without a catalyst and with Ga/HZSM-5 catalysts with various gallium loadings (0.3, 3 and 9 wt%) and bulk Ga2O3 catalysts using pyrolysis/gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Py/GC-MS). The catalytic influence of different gallium loadings on HZSM-5 in cellulose pyrolysis reactions is discussed using a range of characterisation techniques, including ICP, XRD, N2 porosimetry, DRIFTS, and TPRS. The main production of oxygenated compounds (furan, sugar, ketone and phenol) and hydrocarbon products, including total aromatic and monocyclic and polycyclic aromatics, as well as benzene, toluene, xylene (BTX) and naphthalene compounds, using a family of Ga-doped HZSM-5 catalysts for cellulose pyrolysis is investigated for making sustainable cellulose-derived fuel. Ga(3)/HZSM-5 formed the highest amount of aromatics, displaying that aromatic yield depends on the Brønsted-to-Lewis acid balance (2.3 ratio) and total acidity (1.03 mmol·g−1), rather than on gallium loading alone.

1. Introduction

As an alternative fuel source, given the high demand for fossil fuels, biomass- and cellulose-derived hydrocarbon fuels have received significant attention due to their potential to reduce environmental impacts. Fast pyrolysis is one of the main processes used to transform biomass into liquid hydrocarbons [1,2]. Fast pyrolysis is a reaction that pyrolyses biomass in an inert environment at atmospheric pressure in the absence of oxygen [3,4]. Cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin of biomass decompose into small oxygenated molecules as pyrolysis vapours when biomass is heated quickly at intermediate temperatures (400–600 °C) in the absence of oxygen [5,6]. These pyrolysis vapours can be cooled to yield a liquid fuel, normally denoted bio-oil or pyrolysis oil [7,8]. The bio-oil produced is a combination of oxygenated species that typically contain phenolics, furans, carboxylic acids, and other minor oxygenates that vary with different biomass sources and processes [9,10]. The derived bio-oil requires upgrading to obtain valuable products such as diesel, gasoline or valuable chemicals [11,12].

Zeolite catalysts can be used in the pyrolysis of biomass to convert pyrolysis vapours into aromatic hydrocarbons directly in a single step [13,14,15]. Catalytic fast pyrolysis can transform biomass into gasoline-range aromatics (C6–C12) in a single step [3,16]. Many researchers have examined various zeolites for biomass transformation into aromatic production [14,17,18,19]. HZSM-5, Zeolite Y, Zeolite Beta, Mordenite and numerous mesoporous catalysts (Al-MCM-41 and Al-MSU-F) have been evaluated on different feedstocks, such as sorbitol, glycerol, glucose and xylose. These findings reported that using zeolites increased the aromatic hydrocarbon production significantly. Furthermore, CO and coke were produced during this reaction. Most of these studies suggested that HZSM-5 produced the highest yields of aromatic hydrocarbons among zeolite catalysts [5,20,21].

Zeolite catalysts are desirable in fast pyrolysis reactions because of their shape selectivity [22,23]. Shape-selective catalyst for pyrolysis is described as being initiated by either transition state effects or transport phenomena [24,25]. Additionally, various zeolite pore volume sizes between 5 Å and 12 Å influence mass transfer by selectively preventing reactant molecules that are too large to fit within the pores. Hence, zeolites limit the formation of compounds to a size exceeding the pore size of zeolites. Shape selectivity arises from the restricted spaces found at the intersections of the pores. The confined spaces within zeolite pores restrict certain transition states, thereby influencing the reaction pathway. Additionally, the catalytic behaviour can be further complicated by reactions occurring on the external surface of the zeolite [20,26].

Small-pore zeolites (SAPO-34 and ZK-5), medium-pore zeolites (ZSM-5, ZSM-11, ZSM-23, Ferrierite and MCM-22) and large-pore zeolites (Zeolite Beta and Zeolite Y) were evaluated for catalytic fast pyrolysis of glucose to produce aromatic hydrocarbons [20,27]. It has been reported that most reactants and aromatic products can be accommodated within the medium- and large-sized pores of zeolites. Although small-pore zeolite catalysts produced the largest mass fraction of coke, they did not form any aromatic hydrocarbons with oxygenated products [20]. Medium-pore zeolites between 5.2 Å and 5.9 Å formed the maximum amount of aromatic hydrocarbons. Furthermore, large-pore zeolites produced an elevated quantity of coke and a small quantity of aromatics. Internal pore volume and steric hindrance play an essential part in pore window size in the production of aromatics. Medium-pore zeolites, such as ZSM-5 and ZSM-11, possessing moderate internal pore space and steric constraints produced the maximum amount of aromatics with the least coke formation [20].

Furthermore, the alumina content of zeolite particles plays an essential part in catalyst hydrophilicity [28] and Brønsted acid site density, which may impact aromatic production [29,30]. Foster et al. suggested that a silica-to-alumina ratio of 30 for HZSM-5 (SiO2/Al2O3 or SAR = 30) produced more aromatic products compared with SAR = 23, 50 and 80. This shows that the acid concentration of zeolite catalysts is an essential factor in producing the maximum amount of aromatic hydrocarbons [31]. Zeolite catalysts modified with transition metals such as Ce, Ni, Co and Ga produce a higher yield of aromatics and higher selectivity than commercial zeolite catalysts in bio-oil upgrading [32,33,34].

Several studies have investigated the effect of metal modification on HZSM-5 catalysts for catalytic pyrolysis. Islam et al. [35] compared HZSM-5 with various metal-modified forms, including Ga/ZSM-5, Ga/Ni/ZSM-5, Ga/Co/ZSM-5, and Ga/Cu/ZSM-5, and reported that Ga/ZSM-5 yielded the highest liquid oil production, approximately 41%. Dai et al. [36] further highlighted that gallium-modified HZSM-5 positively influenced aromatic hydrocarbon formation, whereas iron-modified HZSM-5 reduced the amount of aromatics but increased benzene, toluene, and xylene (BTX) selectivity from 51.1% to 58.1%. In studies focusing on monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (MAHs), it was observed [37] that 8Ni/HZSM-5 achieved a MAH yield of 53.5%, while 3 Ga/HZSM-5 produced an even higher MAH yield of 61.4%, demonstrating the superior performance of gallium in promoting aromatic selectivity. Therefore, gallium effectively promotes the conversion of biomass-derived olefins into aromatic hydrocarbons [38].

There are different methods to introduce gallium into zeolite catalysts, such as incipient wetness impregnation and ion exchange [39,40]. However, different preparation methods of Ga/zeolite do not seem to have a considerable effect on the catalytic behaviour of aromatisation [39,41].

Yung et al. [42] investigated biomass pyrolysis over Ga-modified HZSM-5 using a multi-scale reactor approach, including (i) a pyroprobe reactor with 10 mg of catalyst operated as a fixed bed at a WHSV of 36 h−1, (ii) a fixed-bed reactor with 500 mg of catalyst at a WHSV of 6 h−1, and (iii) a large-scale fluidised-bed reactor using 1 kg of catalyst at a WHSV of 7 h−1. Across reactor scales, Ga-doped HZSM-5 increased the yield of aromatic liquid-range hydrocarbons by approximately 30% compared with HZSM-5-derived oil. Furthermore, Mao et al. [43] found that compared with pure HZSM-5 after five catalytic biomass fast pyrolysis runs, gallium-modified HZSM-5 catalyst showed higher aromatic hydrocarbon selectivity (up to around 85% vs. 16%) and near-complete recovery upon regeneration (activity index of around 98%), indicating strong potential for industrial application.

Despite these promising results, the effects of varying gallium loadings on HZSM-5 surface acidity and their influence on cellulose fast pyrolysis remain poorly understood. In particular, direct comparisons with bulk Ga2O3 under identical conditions have received limited attention, and the relationships among catalyst composition, acidity, and pyrolysis product distribution have been systematically explored to a limited extent.

This investigation will evaluate the effect of various gallium loadings (0.3, 3 and 9 wt%) on the surface acidity of HZSM-5 catalysts and compare them with bulk Ga2O3 to understand their behaviour in the fast pyrolysis of cellulose, using analytical pyrolysis/gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Py/GC-MS). Py/GC-MS of cellulose with Ga/HZSM-5 catalysts and bulk Ga2O3 is applied to simulate the heating rate and quantify the fast pyrolysis yield to investigate the primary light- and medium-volatile decomposition products generated from this feedstock.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Catalyst Preparation

HZSM-5 zeolite was first calcined in air at 550 °C for 4 h to remove surface impurities. The HZSM-5 used was an industrial sample (SiO2:Al2O3 = 30; Zeolyst International, CBV 3024E, Conshohocken, PA, USA). Gallium was introduced via wet impregnation by mixing 3 g of the calcined zeolite with 20 mL of aqueous gallium nitrate hydrate (Ga(NO3)3·xH2O; crystalline, ≥99.9% trace metals; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA) at concentrations of 0.005 M, 0.03 M, and 0.1 M to achieve the desired loadings. The resulting slurries were stirred at room temperature for 6 h, dried overnight at 90 °C, and subsequently calcined at 500 °C for 4 h under static conditions. The prepared catalysts are denoted by Ga(wt%)/HZSM-5, where Ga(wt%) indicates the actual gallium content. For comparison, bulk gallium oxide (Ga2O3; ≥99.99% trace metals; Sigma-Aldrich) was calcined at 500 °C for 4 h and used as a reference material. Therefore, catalysts were synthesised via incipient wetness impregnation, a well-established method that ensures uniform metal dispersion and precise control of gallium loading, thereby enhancing catalytic performance [44].

2.2. Catalyst Characterisation

Elemental analysis using a Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA) iCAP 7000 inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) instrument was done to measure the Ga loading. The crystalline phases of the catalysts were characterised by X-ray diffractometry (XRD) on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Billerica, MA, USA) with Cu Kα radiation, scanning 2θ from 10 to 60 ° at a step size of 0.04 °. Additionally, the Scherrer equation was used to measure average particle sizes from the peak width of the characteristic of the catalysts.

N2 porosimetry was done by a Quantasorb Nova 4000e porosimeter (Boynton Beach, FL, USA) to measure mesopore volumes, surface areas and pore size distributions. Before the analysis, the catalysts were outgassed under vacuum for around 20 h at 300 °C. Specific surface areas were measured from the adsorption isotherms using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) model at P/P0 = 0.02–0.07. Micropore volumes were measured via the t-plot technique by Lippens and de Boer at P/P0 = 0.2–0.5.

Lewis and Brønsted acid sites were assessed by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) following pyridine adsorption on catalysts diluted with KBr (10 wt%). Excess physisorbed pyridine was removed by drying the catalysts overnight under vacuum at 30 °C. DRIFTS characterisation was conducted by a Nicolet Avatar 370 MCT, incorporating a Smart Collector accessory and a liquid-nitrogen-cooled mercury cadmium telluride (MCT-A) detector. Background-subtracted spectra were applied to measure the relative amounts of Lewis and Brønsted acid sites from the proportion of absorbance intensity bands at 1444 cm−1 and 1545 cm−1.

Acid site strengths and loadings were evaluated by Sigma Aldrich n-propylamine (≥99%) temperature-programmed reaction spectroscopy (TPRS) via Hofmann elimination, which produces propene and ammonia. The experiments were conducted on a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC 2 STARe system (Columbus, FL, USA) coupled with a Pfeiffer Vacuum ThermoStar GSD 301 T3 benchtop mass spectrometer (Nashua, NH, USA). Approximately 20 mg of catalyst was placed in an alumina crucible, with a minimum amount of liquid n-propylamine (≥99%; Sigma-Aldrich) introduced in a controlled amount to ensure saturation of surface acid sites. The sample was allowed to equilibrate at 30 °C, after which excess physisorbed n-propylamine was removed under dynamic vacuum for 1 h to retain only chemisorbed species. After that, the catalysts were heated at a rate of 10 °C·min−1 from 40 °C to 800 °C under a nitrogen flow (40 mL·min−1) using a thermogravimetric analyser (TGA). The evolved gases were monitored by mass spectrometry (m/z = 41) to detect propene formation. The propene peak was used to calculate the acid site loading, assuming one mole of propene per site. Acid strength was measured from the desorption peak temperature (Tmax), with lower Tmax values indicating stronger acid sites.

2.3. Pyrolysis/Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (Py/GC-MS)

Systematic Py/GC-MS was applied to measure and simulate fast pyrolysis heating rates [45,46] and to investigate the primary light- and medium-volatile products formed during cellulose pyrolysis. For each test, about 3 mg of cellulose and 5 mg of catalyst were pyrolysed using a CDS 5200 pyrolyser coupled to a Varian 450-GC chromatograph and then a Varian 220-MS mass spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA, USA). An excess of catalyst relative to cellulose (5:3) is used in Py-GC/MS catalytic fast pyrolysis to maximise contact between the volatile pyrolysis products and the active sites on the catalyst [47,48].

Samples were pyrolysed at 550 °C with a residence time of 2 s at a heating rate of 20 °C·ms−1 (~2 × 104 °C·s−1), characteristic of micro-pyrolysis systems that simulate fast pyrolysis conditions [49]. Separation was achieved on a Varian factorFour column (30 m, 0.25 mm id, 0.25 µm df). The oven was initially held at 45 °C for 2.5 min, ramped to 250 °C at a rate of 5 °C·min−1, and maintained at 250 °C for 7.5 min. The devolatilised components were transferred to the GC column via a heated line kept at 310 °C, while the PTV1070 injection port was held at 275 °C.

Compound identification was performed tentatively using the NIST05 mass spectral library over m/z 45–300, with acceptable similarity scores (>75%), retention time consistency, and characteristic fragmentation patterns [50]. No explicit isomer verification or chromatographic deconvolution was applied. Potential coelution was addressed by assigning peaks based on dominant library matches and diagnostic fragment ions. No internal standard (IS) was used. Calibration standards (syringaldehyde, vanillin, creosol, furfuryl alcohol, furfural, 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol, phenol, guaiacol, catechol, p-cresol, and levoglucosan, 500–4000 µg·mL−1 in GC-grade ethanol) were prepared only to verify compound identification and detector response, not for quantitative calculations.

Pyrolysis products were quantified as relative peak areas (%), calculated as the individual peak area divided by the total chromatogram area. Total aromatic hydrocarbons were obtained by summing peaks assigned to benzene, toluene, xylene (BTX), monocyclic, and polycyclic aromatics, with classes defined based on ring structure and functional groups. All Py/GC–MS experiments were performed in duplicate, and reported values represent the mean relative peak areas. Error bars indicate the variability between the two replicate measurements. Data are therefore semi-quantitative, enabling comparison of catalyst performance without reporting absolute concentrations.

3. Results

3.1. Catalyst Characterisation

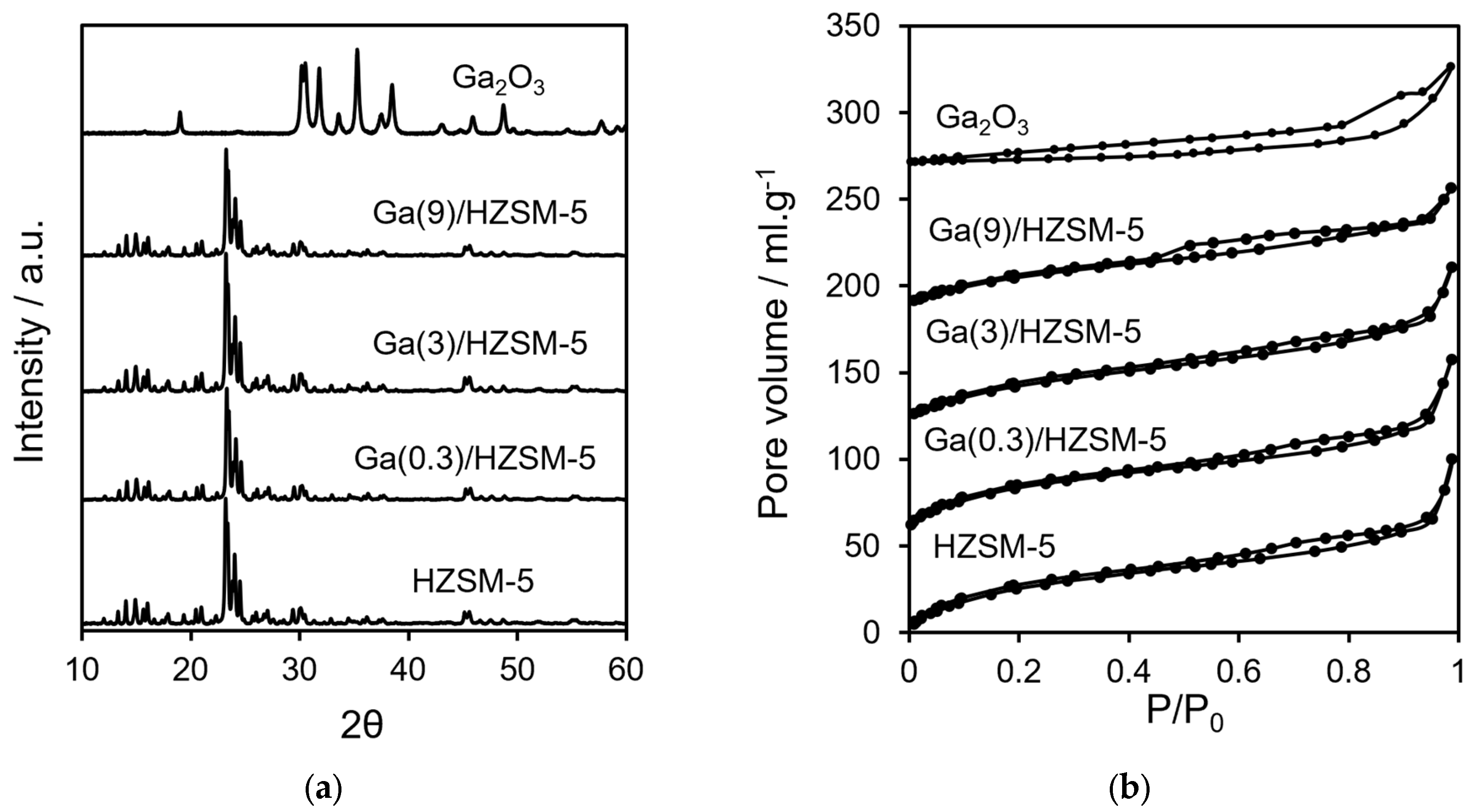

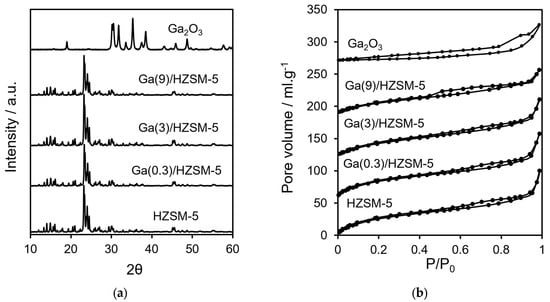

Table 1 shows ICP elemental analysis results for Ga(wt%)/HZSM-5 and Ga2O3. Figure 1a displays XRD profiles for HZSM-5 at various gallium loadings and for bulk Ga2O3. No reflections attributable to gallium oxide phases were observed at any loading, indicating either the formation of highly dispersed Ga2O3 nanoparticles within the HZSM-5 pores or the incorporation of Ga3+ ions into the framework in place of Al3+ (protons on the zeolite surface) [51].

Table 1.

ICP elemental analysis and XRD of catalysts.

Figure 1.

(a) XRD profiles and (b) nitrogen porosimetry of catalysts.

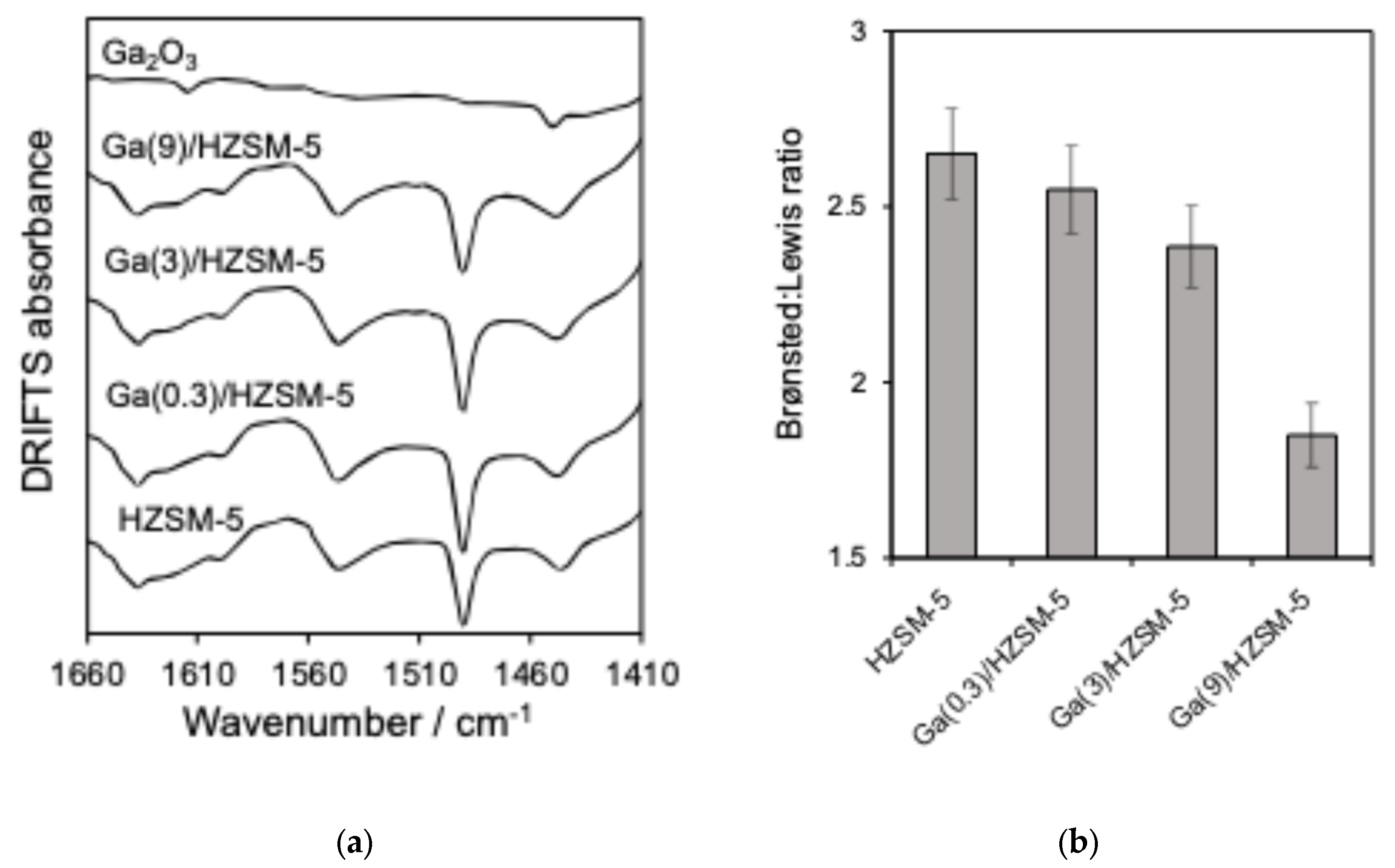

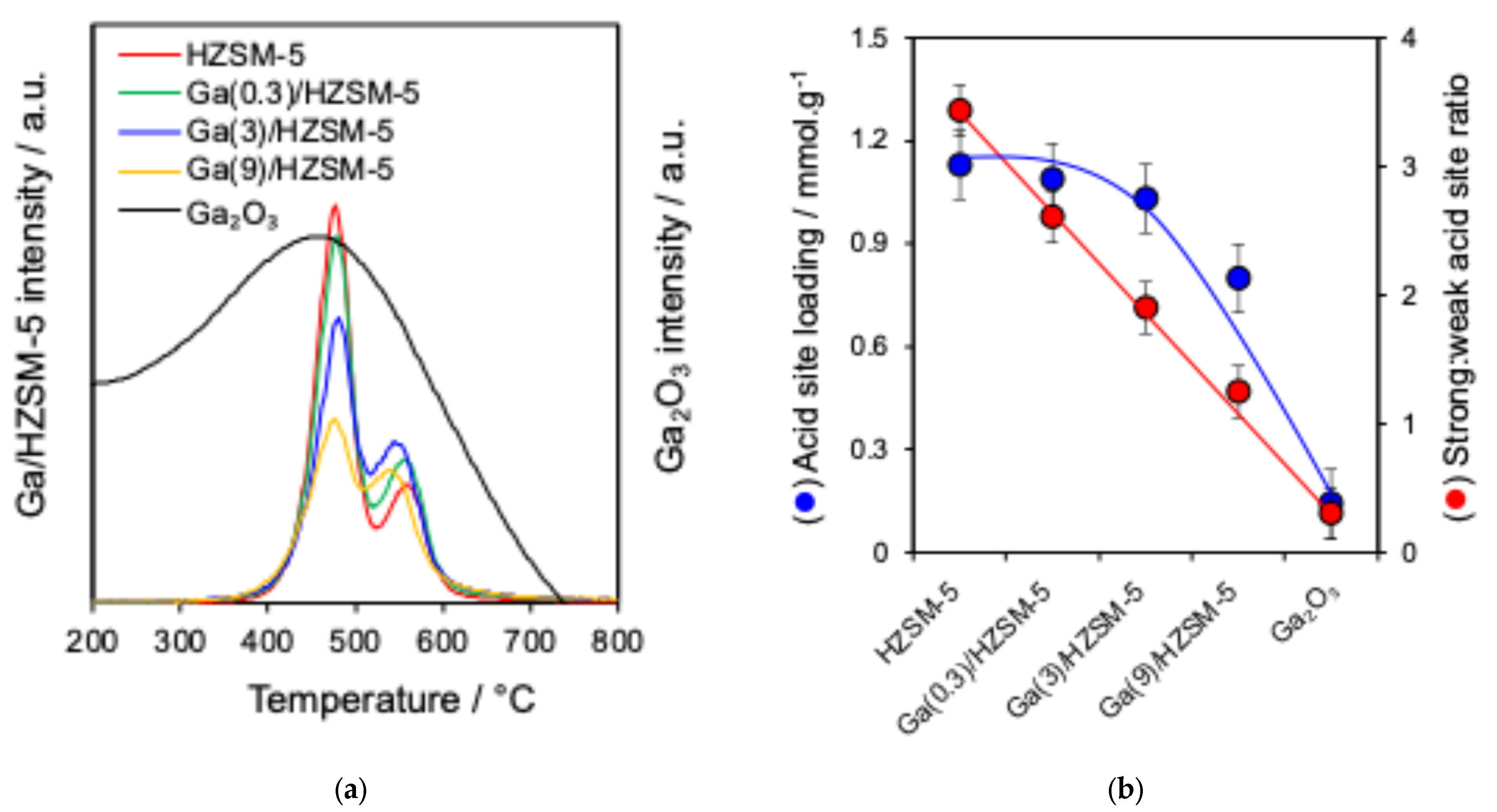

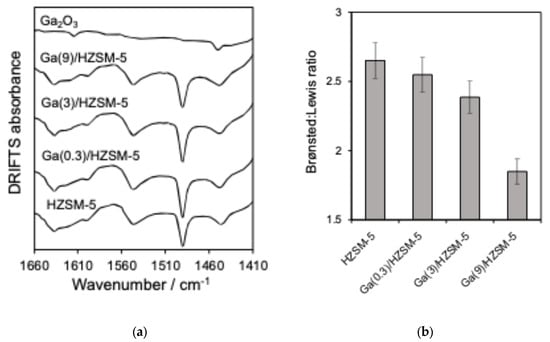

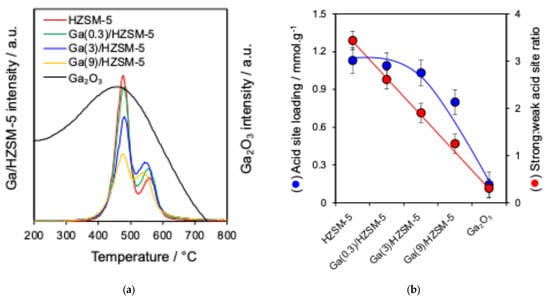

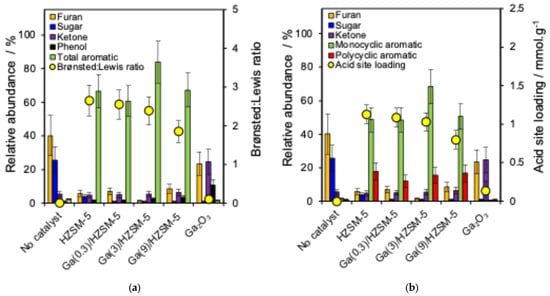

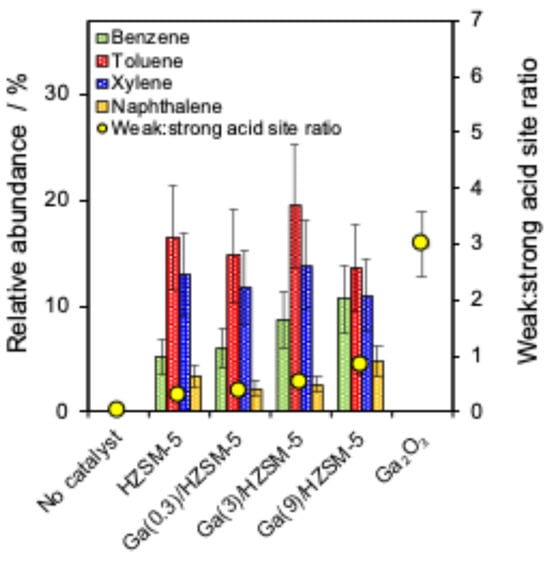

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms are displayed in Figure 1b. BET surface area and pore volume analysis are reported in Table 2. The acid characteristics of Ga(wt%)/HZSM-5 and Ga2O3 are investigated by pyridine-adsorbed DRIFTS (Figure 2a). The ratio of Brønsted to Lewis acid sites is determined by comparing the intensities of the 1545 cm−1 and 1444 cm−1 infrared bands (Figure 2b). Propylamine TPRS is employed to assess acid strength (Figure 3a). Additionally, Figure 3b presents the acid site concentrations and the ratio of strong to weak acid sites for HZSM-5 catalysts with varying gallium loadings.

Table 2.

Nitrogen porosimetry analysis of catalysts.

Figure 2.

(a) DRIFTS of pyridine-saturated and (b) ratio of Brønsted to Lewis acid sites (1545 cm−1: 1444 cm−1 bands) for catalysts.

Figure 3.

(a) Propene formation from propylamine TPRS and (b) acid site analysis of catalysts.

3.2. Analytical Pyrolysis

It should be considered that the pyroprobe reactor exhibits substantial differences compared with large-scale reactors used for the production of liquid hydrocarbons via catalytic pyrolysis, such as heat and mass transfer, and catalyst substrate ratio [52]. Therefore, these results may only partially reflect the composition of fast pyrolysis products in larger-scale reactors. The pyroprobe technique is very useful for comparing the efficiency of reactant–catalyst combinations and for catalyst screening and the identification of reaction intermediates [52].

Figure S1 shows the Py/GC-MS peaks for cellulose pyrolysis in the absence of a catalyst and over different gallium loadings on HZSM-5 as well as Ga2O3 catalysts. Significant differences can be observed in cellulose decomposition in both the absence and presence of various catalysts. Table S1a,b list the numbered compounds from Figure S1, which were observed by Py-GC/MS.

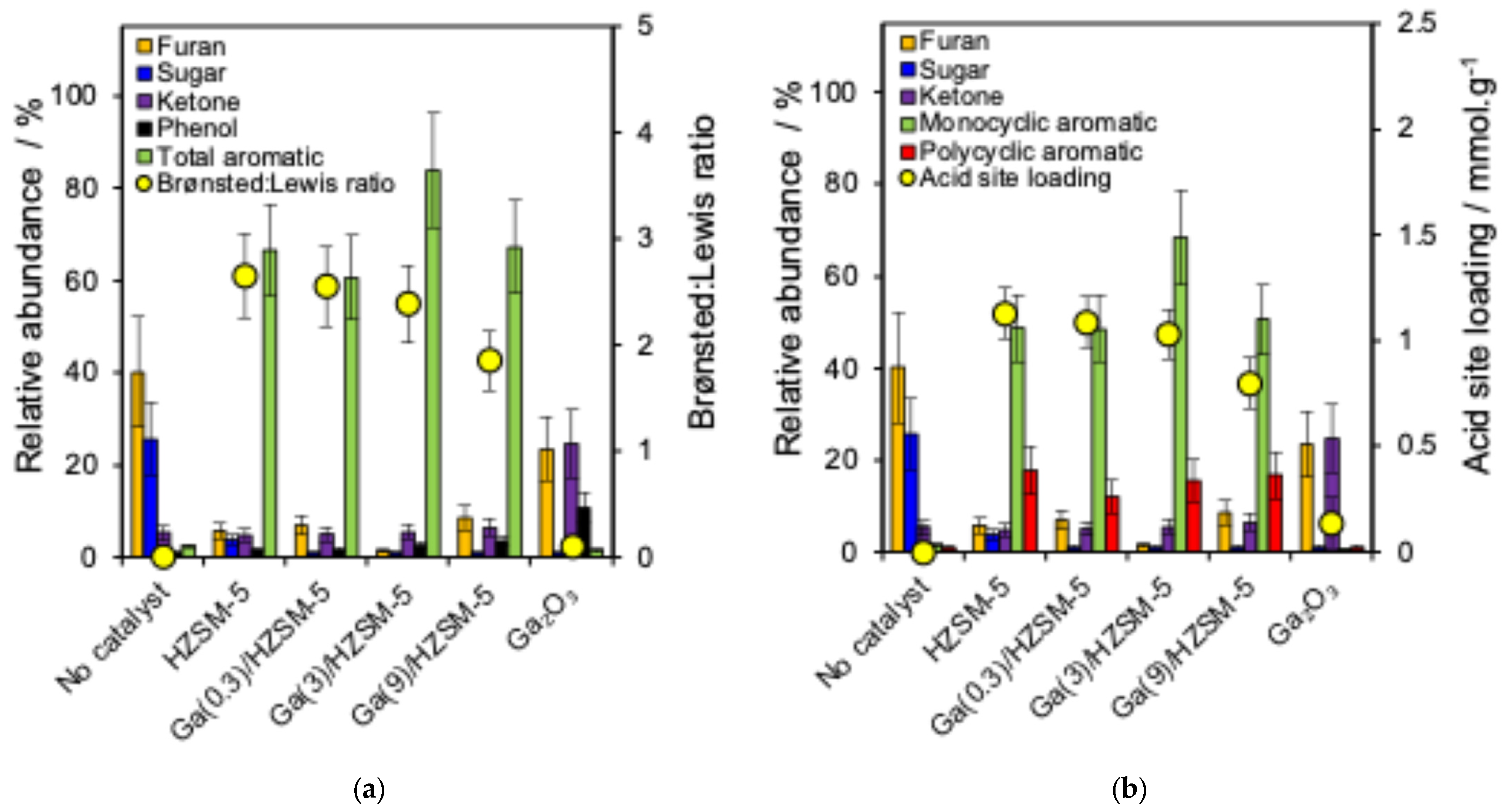

3.3. Catalytic Activity in Pyrolysis

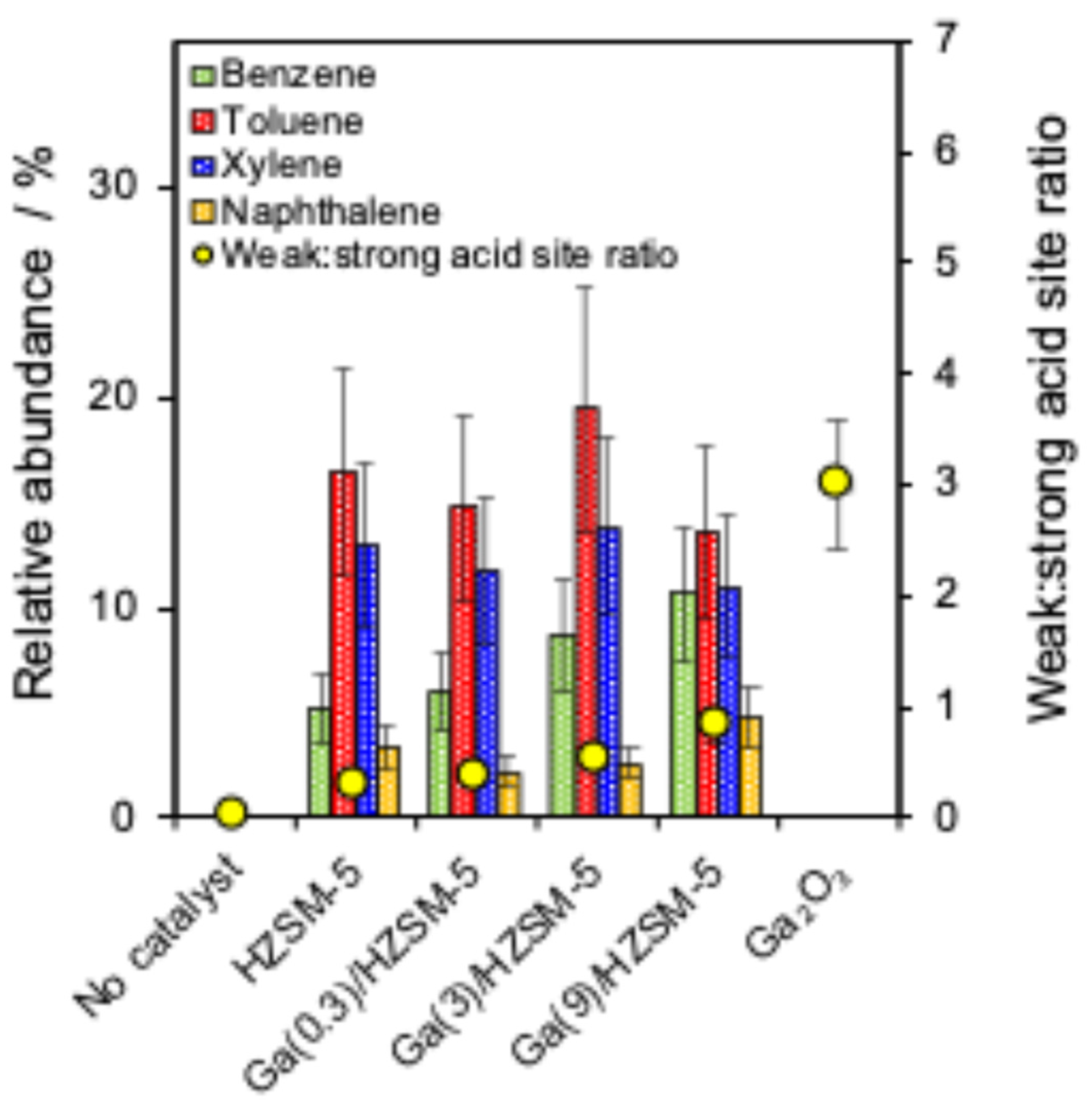

A series of Ga-doped HZSM-5 catalysts was applied to study the catalyst framework effect on the cellulose pyrolysis reaction. Figure 4a shows the relative abundance of the main produced chemical groups (furan, sugar, ketone, phenol and total aromatics) and correlation with the Brønsted:Lewis acid ratio. Figure 4b represents the main compounds, as well as monocyclic and polycyclic aromatics, and their correlation with the acid site loading of different catalysts. Figure 5 shows that BTX and naphthalene are produced with a series of catalysts.

Figure 4.

(a) Relationship between the relative abundance of major compound groups and Brønsted: Lewis ratio and (b) relationship between the relative abundance of major compound groups and the acid site loading of catalysts.

Figure 5.

Correlation between BTX and weak:strong acid site ratio of catalysts.

4. Discussion

4.1. Catalyst Characterisation

ICP elemental analysis (Table 1) showed that Ga at different loadings is impregnated with the HZSM-5 catalyst. Crystalline phases were analysed using XRD (Figure 1a). It has been reported that impregnation promotes the formation of Ga2O3 and the trace surface GaO+ species on HZSM-5, resulting in the introduction of weak Lewis acidity [53]. However, ion exchange through refluxing HZSM-5 in aqueous Ga(NO3)3 at 70–100 °C favours framework dealumination in Ga/HZSM-5 [41,54,55]. Despite the similarity between the reported synthesis procedures and the current study’s impregnation conditions, it remains unclear whether Ga is present as surface GaO+ clusters or incorporated into the zeolite framework. Protons are well known to play an essential part in governing interactions between metal oxides and zeolite surfaces [56,57]. XRD analysis confirmed that the reference gallium oxide was monoclinic Ga2O3, showing characteristic reflections at 2θ values around 19°, 30–32°, 33–35.5°, 37–39°, 42.8°, 46–49°, and 57.5° [58,59]. Additionally, the parent HZSM-5 crystallite sizes showed no significant changes with varying Ga loading (Table 1).

Nitrogen porosimetry showed type IV isotherms for different gallium loadings on HZSM-5 (Figure 1b), where the mesoporosity is due to interparticle voids [51,60]. Increasing Ga loading on HZSM-5 led to progressive decreases in micropore volume, total pore volume and BET surface area (Table 2), suggesting that extra-framework gallium deposition partially blocked the micropores [61]. Bulk Ga2O3 exhibited an extremely low surface area (<9 m2·g−1).

Following pyridine adsorption, Figure 2b revealed bands at 1545 cm−1 and 1444 cm−1, corresponding to Brønsted and Lewis acid sites, respectively, while the band at 1490 cm−1 indicates adsorption on both types of acid sites [61]. The Brønsted:Lewis ratio showed a more significant decrease for Ga(9)/HZSM-5, consistent with previous literature reports [61,62,63]. DRIFTS investigation of pyridine on Ga2O3 revealed two weak bands at 1452 cm−1 and 1614 cm−1, indicating the presence of Lewis acid sites, as noted in previous studies [51,64,65].

Reactively formed propene (Figure 3a), produced from the breakdown of propylamine at active sites, was identified in two desorption peaks at approximately 480 °C and 540–555 °C, corresponding to strong and weak acid sites, respectively, for various gallium loadings on HZSM-5. The former may be attributed to high-index facets or defects [66,67]. The temperature of the weak desorption peak shifted slightly with the increase in Ga loading. However, bulk G2O3 is dominated by weak Lewis acid sites with negligible strong acidity [68]. Additionally, acid site loadings and the strong:weak acid site ratio for Ga/HZSM-5 catalysts decreased with the increase in Ga loading (Figure 3b). With the increase in gallium content, the strong-to-weak acid site ratio declined monotonically, attaining a value of about 1.0 for Ga(9)/HZSM-5. This decline in acid strength is attributed to the substitution of less electronegative Ga3+ ions for Al3+ in the zeolite framework, which reduces hydroxyl polarisation and, consequently, weakens the Brønsted acid sites [51,62].

4.2. Analytical Pyrolysis

Table S1a,b show the variation among products across various compound classes as the catalyst is varied. It is clear that the non-catalytic pyrolysis of the cellulose sample produced a large amount of sugars and furans, whereas the use of gallium on HZSM-5 catalysts formed a large amount of aromatic hydrocarbons. Furthermore, the bulk Ga2O3 catalyst did not produce any significant amount of aromatic hydrocarbons.

4.3. Catalytic Activity in Pyrolysis

Non-catalytic pyrolysis (Figure 4a) of the cellulose sample formed only a trace amount of aromatic compounds but a more significant amount of sugar and furan [69]. However, the aromatic hydrocarbons increased when using the HZSM-5 catalyst [17,70]. Lin et al. reported that anhydrosugars produced from cellulose undergo dehydration to form furans [69]. Over HZSM-5, furans subsequently undergo acid-catalysed reactions, including cracking, dehydration, oligomerisation, cyclisation, and aromatisation. These pathways lead to the formation of olefins and aromatic hydrocarbons, with CO, CO2, and H2O generated as secondary products through decarbonylation and decarboxylation reactions [71,72]. These transformations are facilitated because of the structure, pore size, internal pore volume and acid properties of the zeolite catalyst [71,72].

Different gallium loadings over HZSM-5 formed high aromatic hydrocarbons because of the total pore volume of HZSM-5 in the range of 0.210–0.295 mL·g−1 (Table 2), which is consistent with the literature [20,73]. Wang et al. reported that in the methanol-to-olefins (MTO) reaction, the hydrocarbon pool intermediates could not form in H-ZSM-22 with a smaller channel diameter of 5.7 Å, while the reaction proceeded in H-ZSM-12 with a channel diameter of 5.7–6 Å, indicating that the key reactive intermediates require channels larger than 5.7 Å [74]. In this study, the total pore volume of HZSM-5 (0.294 mL·g−1; Table 2) could provide sufficient space for the adsorption and diffusion of furan and other small intermediates, thereby supporting efficient catalytic conversion.

Cellulose pyrolysis over bulk Ga2O3 catalysts did not produce any aromatic hydrocarbon (Figure 4a), while it formed a high abundance of furan, ketone and phenol because Ga2O3 does not have the structure of zeolite catalysts to produce any hydrocarbon, and it acts just as a Lewis acid site. The conversion of furan into aromatic products is significantly limited when Brønsted acid sites are absent [41].

Figure 4a,b show that Ga(3)/HZSM-5 produced the highest levels of total and monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. The Ga(0.3)/HZSM-5 and Ga(9)/HZSM-5 catalysts generated similar amounts of monocyclic and polycyclic aromatics, but both produced lower total aromatics than Ga(3)/HZSM-5.

One possibility could be that increasing the gallium loading on HZSM-5 catalysts affects both framework and extra-framework Ga species. It is reported that at low Ga/Al ratios (<2.0), Ga predominantly forms extra-framework GaO+ species, enhancing Lewis acidity, while at higher Ga/Al ratios (>2.0), Ga3+ partially incorporates into the zeolite framework via Ga–O–Si bonds, generating weaker Brønsted sites and limiting space for extra-framework species [62]. Therefore, this shift in the Brønsted/Lewis balance reduces Brønsted-driven cracking and influences aromatisation, as shown in Figure 4a.

As a result, Ga(3)/HZSM-5 provides a balance of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites, accelerating the aromatisation reaction [75]. Park et al. reported that 1 wt% Ga on Meso-MFI zeolite increased the monocyclic aromatic yield from 20% to 38%, while 5 wt% Ga decreased it to 18% due to a reduction in Brønsted acidity [76]. Kwak et al. studied Ga/HZSM-5 catalysts for propane aromatisation, finding that propane undergoes dehydrogenation over Lewis acidic gallium sites to form propene, with aromatisation occurring over HZSM-5 sites [77].

Also, another possibility for the maximum total aromatic production for Ga(3)/HZSM-5 is that the excessive Ga (above 3 wt% Ga) could block active acid sites more extensively, thereby decreasing the number of active sites (Figure 4b) and decreasing the BET surface area from 425 m2·g−1 for HZSM-5 to 310 m2·g−1 for Ga(9)/HZSM-5 (Table 2), which diminishes catalytic efficiency and inhibits aromatisation reactions [76]. Kelkar et al. reported that the loading of 2.5 wt% gallium on HZSM-5 decreased the aromatic yield by 5% in comparison to pure HZSM-5 [78]. Furthermore, Schulz et al. reported that maximum aromatic selectivity was obtained for 3 wt% Ga on HZSM-5 catalyst with gallium contents ranging from 1.5 wt% to 6 wt%, while using above 3 wt% gallium on HZSM-5 did not increase the aromatic yield for the aromatisation of ethane [79]. Therefore, the selectivity of aromatic production is not necessarily improved by adding more gallium to HZSM-5 catalysts [62,75,78].

No BTX and naphthalene are produced in the absence of a catalyst and in the presence of a Ga2O3 catalyst for cellulose pyrolysis (Figure 5). Pure HZSM-5 produced toluene, xylene and naphthalene with no significant changes compared to Ga(0.3)/HZSM-5, Ga(3)/HZSM-5, and Ga(9)/HZSM-5 catalysts. However, adding more gallium to HZSM-5 gradually increased the benzene aromatic [62,80], accompanied by elevated Lewis acidity and an increased weak-to-strong acid site ratio (Figure 5). Adjaye et al. reported that light organics from cellulose can be deoxygenated and cracked with zeolite catalysts into C2-C6 olefins, which then aromatise them into benzene, toluene, xylene, and other aromatics [81]. Cheng et al. studied that HZSM-5 formed more toluene and xylene than Ga/HZSM-5, while Ga/HZSM-5 increased benzene yield compared with HZSM-5 [41]. Thus, HZSM-5 is a selective catalyst for BTX formation [82], but the selectivity toward benzene on Ga/HZSM-5 increased with the weak-to-strong acid site ratio, indicating a preference for weak Lewis acid sites. While environmental fuel standards limit aromatic content in finished fuels, increasing aromatics during catalytic pyrolysis remains valuable. Ga-modified HZSM-5 enhances deoxygenation and energy density of bio-oil, producing mainly monocyclic aromatics that can be further upgraded or refined to meet fuel regulations [38,83]. Therefore, Ga-modified catalysts can be justified as an intermediate step toward higher-quality bio-oil production or the production of valuable chemicals.

5. Conclusions

Cellulose pyrolysis was investigated using Py/GC-MS analysis, both uncatalysed and in the presence of HZSM-5, Ga(0.3)/HZSM-5, Ga(3)/HZSM-5, Ga(9)/HZSM-5, and bulk Ga2O3 catalysts. XRD indicated no separate crystalline Ga2O3 phase, and Ga may be highly dispersed and/or present as extra-framework species across loadings from 0.3 wt% to 9 wt%. Increasing Ga loading on HZSM-5 has no significant impact on the zeolite’s crystallite size but decreases Brønsted acidity and BET surface area. Non-catalytic cellulose pyrolysis yielded trace amounts of aromatics but significant amounts of oxygenated compounds, including furans and sugars, which are associated with limited bio-oil applicability and low fuel stability. However, catalytic Py/GC-MS with Ga/HZSM-5 produced abundant aromatics, showing the importance of Lewis and Brønsted acidity as well as shape selectivity for cellulose upgrading. Bulk Ga2O3 failed to generate aromatics due to its lack of Brønsted acidity and shape selectivity, which are crucial to aromatic production. Furthermore, adding more gallium to HZSM-5 did not necessarily increase total aromatic production for cellulose pyrolysis, which could be related to the balance between Brønsted and Lewis acid sites, as well as the overall acid site loading, showing that Ga(3)/HZSM-5 produced the maximum total aromatics. Pure HZSM-5 is a selective catalyst promoting BTX production; however, benzene production from cellulose pyrolysis was proportional to the weak:strong acid site ratio, demonstrating that benzene production with Ga/HZSM-5 catalysts favourably occurs at weak acid sites. Therefore, Ga(3)/HZSM-5 can be a promising catalyst for industrial cellulose upgrading and bio-oil pre-treatment, providing guidance on designing catalysts with optimised Ga loading, acid site balance, and shape selectivity. Finally, Py/GC-MS provides an effective method for quantifying and simulating fast pyrolysis, enabling the investigation of major light- and medium-volatile decomposition products formed in the presence of the catalysts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13020113/s1, Figure S1. Py/GC-MS chromatograms for cellulose: (a) no catalyst and with (b) HZSM-5, (c) Ga(0.3)/HZSM-5, (d) Ga(3)/HZSM-5, (e) Ga(9)/HZSM-5 and (f) Ga2O3; Table S1a. Cellulose pyrolysis compounds in the absence of catalyst and with HZSM-5 and Ga(0.3)/HZSM-5 (continued); Table S1b. Cellulose pyrolysis compounds in the presence of Ga(3)/HZSM-5, Ga(9)/HZSM-5 and bulk Ga2O3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.J. and K.K.; methodology, H.J.; software, H.J.; validation, H.J., and O.D.; formal analysis, H.J., K.K., M.G., K.A., A.M.A.-Q. and O.D.; investigation, H.J., K.A., A.M.A.-Q. and O.D.; resources, H.J.; data curation, H.J. and O.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J.; writing—review and editing, H.J., K.K., M.G. and O.D.; visualization, H.J. and O.D.; supervision, H.J., K.K., M.G. and O.D.; project administration, H.J.; funding acquisition, H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Sheffield Hallam University, Cranfield University, University of Tehran, Jubail Industrial College and the University of Birmingham. The authors used generative AI tools for language editing and to improve the Graphical Abstract. All content, data, and interpretations were reviewed and approved by the authors, who take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Py/GC-MS | Pyrolysis/gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analyser |

| ICP | Inductively coupled plasma |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| DRIFTS | Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy |

| TPRS | Temperature-programmed reaction spectroscopy |

| BTX | Benzene, toluene, xylene |

References

- Pinard, L.; Jia, L.; Pichot, N.; Astafan, A.; Dufour, A. Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass over Hierarchical Zeolites: Comparison of Mordenite, Beta, and ZSM-5. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 14351–14364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xin, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Zou, R.; Liang, J. Hollow ZSM-5 encapsulated with single Ga-atoms for the catalytic fast pyrolysis of biomass waste. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 84, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, T.R.; Vispute, T.R.; Huber, G.W. Green gasoline by catalytic fast pyrolysis of solid biomass derived compounds. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.T.; Menezes, A.L.d.; Cardoso, C.R.; Cerqueira, D.A. Analytical Pyrolysis of Sunflower Seed Husks: Influence of Hydrogen or Helium Atmosphere and Ex Situ Zeolite (HZSM-5) Catalysis on Vapor Generation. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 3851–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Review of fast pyrolysis of biomass and product upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 38, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, C.; Di Blasi, C. Analysis of component interaction in beech wood pyrolysis by native mixing with mildly invasive pretreatments. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 187, 106988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Renewable fuels and chemicals by thermal processing of biomass. Chem. Eng. J. 2003, 91, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.R.; Araujo, D.R.; Rodrigues, M.A. Strategic techniques for upgrading bio-oil from fast pyrolysis: A critical review. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2025, 19, 2457–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V. Upgrading Biomass Fast Pyrolysis Liquids. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2012, 31, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Kumar, D.J.P.; Sankannavar, R.; Binnal, P.; Mohanty, K. Hydro-deoxygenation of pyrolytic oil derived from pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass: A review. Fuel 2024, 360, 130473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, D.M.; Bond, J.Q.; Dumesic, J.A. Catalytic conversion of biomass to biofuels. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1493–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonsupap, S.; Pattiya, A. Effect of partial catalyst regeneration on the production of deeply deoxygenated bio-oil by catalytic fast pyrolysis of biomass using HZSM-5 in a bench-scale fluidized-bed reactor. Fuel 2026, 405, 136467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattiya, A.; Titiloye, J.O.; Bridgwater, A.V. Fast pyrolysis of cassava rhizome in the presence of catalysts. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2008, 81, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattiya, A.; Titiloye, J.O.; Bridgwater, A.V. Evaluation of catalytic pyrolysis of cassava rhizome by principal component analysis. Fuel 2010, 89, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, T.R.; Tompsett, G.A.; Conner, W.C.; Huber, G.W. Aromatic Production from Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass-Derived Feedstocks. Top. Catal. 2009, 52, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fawal, E.M.; El Naggar, A.M.; El-Zahhar, A.A.; Alghandi, M.M.; Morshedy, A.S.; El Sayed, H.A. Biofuel production from waste residuals: Comprehensive insights into biomass conversion technologies and engineered biochar applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 11942–11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, T.R.; Jae, J.; Huber, G.W. Mechanistic Insights from Isotopic Studies of Glucose Conversion to Aromatics Over ZSM-5. ChemCatChem 2009, 1, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olazar, M.; Aguado, R.; Bilbao, J.; Barona, A. Pyrolysis of sawdust in a conical spouted-bed reactor with a HZSM-5 catalyst. AIChE J. 2000, 46, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.Q.; Zhu, X.L.; Danuthai, T.; Lobban, L.L.; Resasco, D.E.; Mallinson, R.G. Conversion of Glycerol to Alkyl-aromatics over Zeolites. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 3804–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jae, J.; Tompsett, G.A.; Foster, A.J.; Hammond, K.D.; Auerbach, S.M.; Lobo, R.F.; Huber, G.W. Investigation into the shape selectivity of zeolite catalysts for biomass conversion. J. Catal. 2011, 279, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aho, A.; Kumar, N.; Eranen, K.; Salmi, T.; Hupa, M.; Murzin, D.Y. Catalytic pyrolysis of woody biomass in a fluidized bed reactor: Influence of the zeolite structure. Fuel 2008, 87, 2493–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancedo, J.; Li, H.; Walz, J.S.; Faba, L.; Ordoñez, S.; Huber, G.W. Investigation into the shape selectivity of zeolites for conversion of polyolefin plastic pyrolysis oil model compound. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2024, 669, 119484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Xing, P.-Y.; Yi, L.; Qiao, D.-W.; Fang, Z.-M.; Luo, Z.-J.; Zheng, S.; Li, K.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Lu, Q. Effects of pretreatment on aromatic production from catalytic pyrolysis of soy sauce residue for organic liquid hydrogen carriers. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2026, 194, 107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Liu, Z.; Huang, P.; Fu, W.; Ren, J.; Fan, L.; Chen, W.; Tang, T. Shape-selective zeolite catalysis for the tandem reaction of aromatic alcohol dehydration isomerization to internal alkene. J. Catal. 2025, 449, 116221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Maesen, T.L. Molecular simulations of zeolites: Adsorption, diffusion, and shape selectivity. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4125–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yang, M.; Yu, J.; Dyballa, M.; Yang, P.; Li, M.; Hou, G.; Hunger, M.; Dai, W. The role of adsorption and diffusion in improving the selectivity and reactivity of zeolite catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 9192–9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Han, S.; Xie, J.; He, H.; Lin, W.; Mondal, A.K.; Huang, F. Study on the quality improvement of bio-oil prepared by catalytic pyrolysis of kraft lignin: The role of micropore/mesopore beta zeolites. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, C.M.; Cai, R.; Yan, Y.S. Zeolite Thin Films: From Computer Chips to Space Stations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, L.; Hermes, F.; Bertmer, M.; Rodriguez-Castellon, E.; Jimenez-Lopez, A.; Simon, U. The acid properties of H-ZSM-5 as studied by NH3-TPD and Al-27-MAS-NMR spectroscopy. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2007, 328, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sultani, S.H.; Al-Shathr, A.; Al-Zaidi, B.Y. Aromatics Alkylated with Olefins Utilizing Zeolites as Heterogeneous Catalysts: A Review. Reactions 2024, 5, 900–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.J.; Jae, J.; Cheng, Y.T.; Huber, G.W.; Lobo, R.F. Optimizing the aromatic yield and distribution from catalytic fast pyrolysis of biomass over ZSM-5. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2012, 423, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulou, E.F.; Stefanidis, S.D.; Kalogiannis, K.G.; Delimitis, A.; Lappas, A.A.; Triantafyllidis, K.S. Catalytic upgrading of biomass pyrolysis vapors using transition metal-modified ZSM-5 zeolite. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 127, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, R.; Czernik, S. Catalytic pyrolysis of biomass for biofuels production. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grams, J.; Jankowska, A.; Goscianska, J. Advances in design of heterogeneous catalysts for pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass and bio-oil upgrading. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 362, 112761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.O.; Ahmad, N.; Ahmed, U.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Ummer, A.C.; Abdul Jameel, A.G. Producing aromatic-rich oil through microwave-assisted catalytic pyrolysis of low-density polyethylene over Ni/Co/Cu-doped Ga/ZSM-5 catalysts. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin 2025, 19, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Wang, S.; Zou, Q.; Huang, S. Improvement of aromatics production from catalytic pyrolysis of cellulose over metal-modified hierarchical HZSM-5. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 179, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Mao, H.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y. Ga-Ni modified MCM-41@HZSM-5 core-shell zeolite for catalytic fast pyrolysis of wheat straw to produce monocyclic aromatics. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 510, 161707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, L.; Hua, D.; Lu, X.; Yang, D.; Wu, Z. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Cellulose Biomass to Aromatic Hydrocarbons Using Modified HZSM-5 Zeolite. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Miao, Q.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Dong, M.; Wang, P.; Qin, Z.; Fan, W. Controllable synthesis of gallium-containing MFI zeolite for bifunctionally catalyzing methanol aromatization. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 364, 112877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Tian, H.; Zhou, Z.; Xuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S. Catalytic study of metal-modified HZSM-5 core–shell molecular sieves on pyrolysis products of wheat straw after acid washing and torrefaction. Fuel 2026, 405, 136639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.T.; Jae, J.; Shi, J.; Fan, W.; Huber, G.W. Production of Renewable Aromatic Compounds by Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass with Bifunctional Ga/ZSM-5 Catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, M.M.; Stanton, A.R.; Iisa, K.; French, R.J.; Orton, K.A.; Magrini, K.A. Multiscale Evaluation of Catalytic Upgrading of Biomass Pyrolysis Vapors on Ni- and Ga-Modified ZSM-5. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 9471–9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Tian, H.; Lv, D.; Xuan, Y.; Cheng, S.; Liu, L. Deactivation mechanism and regeneration performance of Ga-Ni modified HZSM-5@MCM-41 Core–Shell catalyst during catalytic fast pyrolysis of wheat straw. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 122, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, H.; Han, Y.; Tan, Y. A highly efficient Ga/ZSM-5 catalyst prepared by formic acid impregnation and in situ treatment for propane aromatization. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 4081–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picó, Y.; Barceló, D. Pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in environmental analysis: Focus on organic matter and microplastics. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 130, 115964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-X.; Hao, L.-T.; Wang, H.-Y.-Z.; Li, Y.-J.; Liu, J.-F. Cloud-point extraction combined with thermal degradation for nanoplastic analysis using pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2018, 91, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.S.; Iskakova, Z.B.; Afroze, S.; Kuterbekov, K.; Kabyshev, A.; Bekmyrza, K.Z.; Kubenova, M.M.; Bakar, M.S.A.; Azad, A.K.; Roy, H.; et al. Influence of Catalyst on the Yield and Quality of Bio-Oil for the Catalytic Pyrolysis of Biomass: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2023, 16, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, X.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, H. One-step flame-synthesized catalysts enable high-value sugar production from cellulose fast pyrolysis. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 24, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Chinnam, S.; Dwivedi, N.; Acharya, B. Pyrolysis of waste pinewood sawdust using Py-GC-MS: Effect of temperature and catalysts on the pyrolytic product composition. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 5314–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, A.A.; Lincoln, C.; Miscall, J.; Stanley, L.M.; Maurya, A.K.; Asundi, A.S.; Tassone, C.J.; Rorrer, N.A.; Beckham, G.T. Characterization of polymer properties and identification of additives in commercially available research plastics. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 7067–7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, H.; Osatiashtiani, A.; Ouadi, M.; Hornung, A.; Lee, A.F.; Wilson, K. Ga/HZSM-5 catalysed acetic acid ketonisation for upgrading of biomass pyrolysis vapours. Catalysts 2019, 9, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, C.A.; Boateng, A.A. Catalytic pyrolysis-GC/MS of lignin from several sources. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 1446–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Su, X.; Bai, X.; Wu, W.; Wang, G.; Xiao, L.; Yu, A. Aromatization over nanosized Ga-containing ZSM-5 zeolites prepared by different methods: Effect of acidity of active Ga species on the catalytic performance. J. Energy Chem. 2017, 26, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yassir, N.; Akhtar, M.; Al-Khattaf, S. Physicochemical properties and catalytic performance of galloaluminosilicate in aromatization of lower alkanes: a comparative study with Ga/HZSM-5. J. Porous Mater. 2012, 19, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.A.S.; Ali, A. Characterization of Modified HZSM–5 with Gallium and its Reactivity in Direct Conversion of Methane to Liquid Hydrocarbons. J. Teknol. 2001, 35, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tessonnier, J.-P.; Louis, B.; Walspurger, S.; Sommer, J.; Ledoux, M.-J.; Pham-Huu, C. Quantitative Measurement of the Brönsted Acid Sites in Solid Acids: Toward a Single-Site Design of Mo-Modified ZSM-5 Zeolite. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 10390–10395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, S.; Li, N.; Chen, H.; Zhang, W.; Bao, X.; Lin, B. Structure and acidity of Mo/ZSM-5 synthesized by solid state reaction for methane dehydrogenation and aromatization. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 88, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Chen, X.L.; Qiao, Z.Y.; He, M.; Li, H. Large-scale synthesis of single-crystalline beta-Ga2O3 nanoribbons, nanosheets and nanowires. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2001, 13, L937–L941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Yeh, C.-S. GaOOH, and [small beta]- and [gamma]-Ga2O3 nanowires: Preparation and photoluminescence. New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yin, Q.; Guo, J.; Ru, B.; Zhu, L. Improved Fischer–Tropsch synthesis for gasoline over Ru, Ni promoted Co/HZSM-5 catalysts. Fuel 2013, 108, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, V.D.; Eon, J.G.; Faro, A.C. Correlations between Dispersion, Acidity, Reducibility, and Propane Aromatization Activity of Gallium Species Supported on HZSM5 Zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 4557–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, N.; Ma, C.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Ling, L. Influence of Ga content on the acidic characteristics and methanol to aromatics performance of Ga-ZSM-5 zeolites. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 316, 121929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, C.; Zhang, R.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Ling, L. Propane dehydroaromatization on Ga-modified HZSM-5 catalyst: Brønsted/Lewis acid synergistic effect. J. Catal. 2025, 447, 116147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavalley, J.C.; Daturi, M.; Montouillout, V.; Clet, G.; Arean, C.O.; Delgado, M.R.; Sahibed-dine, A. Unexpected similarities between the surface chemistry of cubic and hexagonal gallia polymorphs. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 1301–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimont, A.; Lavalley, J.C.; Sahibed-Dine, A.; Arean, C.O.; Delgado, M.R.; Daturi, M. Infrared spectroscopic study on the surface properties of gamma-gallium oxide as compared to those of gamma-alumina. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 9656–9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumman, P.; Niamlang, S.; Sirivat, A. Fabrication of Poly(p-Phenylene)/Zeolite Composites and Their Responses Towards Ammonia. Sensors 2009, 9, 8031–8046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morterra, C.; Cerrato, G.; Ferroni, L.; Negro, A.; Montanaro, L. Surface characterization of tetragonal ZrO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1993, 65, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Fernández, P.; Mance, D.; Liu, C.; Moroz, I.B.; Abdala, P.M.; Pidko, E.A.; Copéret, C.; Fedorov, A.; Müller, C.R. Propane Dehydrogenation on Ga2O3-Based Catalysts: Contrasting Performance with Coordination Environment and Acidity of Surface Sites. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 907–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Cho, J.; Tompsett, G.A.; Westmoreland, P.R.; Huber, G.W. Kinetics and Mechanism of Cellulose Pyrolysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 20097–20107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Dai, S.; Kang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q. Understanding the enhanced preparation of aromatic hydrocarbons in pyrolysis of individual lignocellulosic biomass components over a (Ca-Fe)/HZSM-5 catalyst. Fuel 2025, 386, 134228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Hei, J.; Huang, S.; Gao, D. Production of aromatic hydrocarbons from catalytic fast pyrolysis of microalgae over Fe-modified HZSM-5 catalysts. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 36970–36979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Han, T.; Yang, W.; Sandström, L.; Jönsson, P.G. Influence of the porosity and acidic properties of aluminosilicate catalysts on coke formation during the catalytic pyrolysis of lignin. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 165, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Lei, X.; Xu, G.; Chen, H.; Hu, J. Catalytic fast pyrolysis of kraft lignin over hierarchical HZSM-5 and Hβ zeolites. Catalysts 2018, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Cui, Z.M.; Cao, C.Y.; Song, W.G. 0.3 angstrom Makes the Difference: Dramatic Changes in Methanol-to-Olefin Activities between H-ZSM-12 and H-ZSM-22 Zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 24987–24992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Pyo, S.; Kumar, A.; Khani, Y.; Choi, S.Q.; Cho, K.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.-K. Improvement in the production of aromatics from pyrolysis of plastic waste over Ga-modified ZSM-5 catalyst under C1-gas environment. Chin. J. Catal. 2025, 73, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Heo, H.S.; Jeon, J.K.; Kim, J.; Ryoo, R.; Jeong, K.E.; Park, Y.K. Highly valuable chemicals production from catalytic upgrading of radiata pine sawdust-derived pyrolytic vapors over mesoporous MFI zeolites. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 95, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, B.S.; Sachtler, W.M.H. Effect of Ga/Proton Balance in Ga/Hzsm-5 Catalysts on C-3 Conversion to Aromatics. J. Catal. 1994, 145, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, S.; Saffron, C.M.; Li, Z.L.; Kim, S.S.; Pinnavaia, T.J.; Miller, D.J.; Kriegel, R. Aromatics from biomass pyrolysis vapour using a bifunctional mesoporous catalyst. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, P.; Baerns, M. Aromatization of Ethane over Gallium-Promoted H-Zsm-5 Catalysts. Appl. Catal. 1991, 78, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Ding, M. Production of Jet Fuel Range Aromatics by Alkylation of Benzene with Olefins over Bifunctional Ga/ZSM-5 Catalyst. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202401279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjaye, J.D.; Bakhshi, N.N. Production of Hydrocarbons by Catalytic Upgrading of a Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oil. Part II: Comparative Catalyst Performance and Reaction Pathways. Fuel Process. Technol. 1995, 45, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murciano, R.; Navarro, M.T.; Martínez, A. One-pass conversion of syngas to BTX/para-xylene aromatics over tandem oxide-zeolite catalysts based on large crystal size HZSM-5. Catal. Today 2025, 456, 115340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, W.; Cabello, J.H.; Hedlund, J.; Shafaghat, H. Structure-Modified Zeolites for an Enhanced Production of Bio Jet Fuel Components via Catalytic Pyrolysis of Forestry Residues. Catal. Lett. 2025, 155, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.