Abstract

Fluoxetine (FLX) is an antidepressant pertaining to the class of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. FLX use has increased in the past decade culminating in its discharge to surface waters. Owing to the limited knowledge about the toxicity of this drug to aquatic biota, this study aimed to evaluate potential toxic effects of FLX on green algae Chlorella vulgaris, cyanobacteria Microcystis novacekii, marine bacteria Aliivibrio fischeri, and mollusk Biomphalaria glabrata. Assays with C. vulgaris and M. novacekii followed OECD protocol 201 (2011) and NBR 12648 standard (2018), respectively. The assay with A. fischeri was carried out according to ISO/OIN 11348-3 (2007). Toxicity assays with B. glabrata were performed by exposing these organisms (newborn and embryos) in 24-well culture plates for 3 and 7 days, respectively. All test-organisms were exposed to at least 6 different concentrations of FLX, ranging from 0.1 to 20,000 µg/L, in triplicates. Effect concentrations (EC50) obtained for these assays showed that FLX is more toxic to M. novacekii (10.71 ± 1.67 µg/L), followed by C. vulgaris (13.01 ± 2.01 µg/L) and A. fischeri (3140 ± 1050 µg/L). Regarding B. glabrata, the 50% lethal concentration for newborns was 1770 ± 260 µg/L, while for embryos it was equivalent to 34.98 ± 3.66 µg/L. Considering recent reports of FLX occurrence in environmental matrices in the µg/L range, results reported in this study and the toxicity classification criteria by the Globally Harmonized System, FLX poses high risk to aquatic environments, its biodiversity, and ecosystems. Therefore, measures must be taken to prevent the disposal of waste containing FLX into the environment, especially in region lacking basic sanitation infrastructure.

1. Introduction

It is estimated that 5.7% of adults currently suffer from depression. In most cases, the treatment of moderate and severe depression is therapy sessions combined with antidepressant intake [1]. The increased rate of depression worldwide made antidepressants amongst the most prescribed classes of drugs. Fluoxetine (FLX) is one of the most prescribed antidepressants as it is a potent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) [2]. Nearly 10% of FLX is excreted from the human body mainly through the urinary system in its unchanged form, while the remaining is eliminated as norfluoxetine. Once eliminated, these compounds enter the sewage system, yet they are not eliminated in domestic sewage treatment plants and end up in the environment [3].

FLX is partially ionized as a cationic species in wastewater and surface water owing to its acid dissociation constant (pKa = 9.8). Its high lipophilicity (log Kow = 4.10) leads to adsorption, accumulation, and degradation by aquatic organisms, thus increasing its persistence in the environment [4]. Due to increased consumption of this drug by the population, coupled with inadequate popular disposal and lack of basic sanitation infrastructure or inefficient removal in wastewater treatment plants, FLX has been detected in environmental waters in Brazil [5], Portugal [6], Poland [7], USA [8,9,10] and Canada [11,12] (Table 1), at concentrations of up to 43 μg/L [13,14,15].

Table 1.

Environmental concentrations of fluoxetine reported in aquatic environments worldwide.

A study carried out on the Douro and Leça rivers (Portugal) on the occurrence of psychiatric drugs in environmental waters listed FLX as one of the most frequently detected in both rivers reaching environmental concentrations of up to 2 ng/L [6]. Furthermore, FLX was detected in drinking water intended for human consumption in the United Kingdom at a concentration of 0.27 ng/L [16]. Different studies confirmed the FLX occurrence in water reservoirs around the world, along with its potential for bioaccumulation in aquatic organisms [17].

The occurrence of FLX in environmental waters poses a significant threat to aquatic ecosystems due to its toxicity to aquatic fauna. Multiple studies have demonstrated that FLX can affect aquatic organisms even at environmentally relevant concentrations, ranging from 1 to 100 µg/L, with pronounced effects on low trophic level organisms [4,18,19,20,21,22]. As foundational components of the aquatic food chain, cyanobacteria and microalgae are both ubiquitous and highly sensitive, and are therefore commonly used as biological indicators to assess the ecological risks of pollutants [23]. Nevertheless, few studies have specifically investigated FLX toxicity in these primary producers compared to other taxonomic groups [24,25,26].

Beyond primary producers, the effects of antidepressants on shellfish have been studied for decades. Early work by Couper and Leise (1996) [27] showed that FLX significantly influenced larval metamorphosis in Ilyanassa obsoleta. Similarly, Nentwig (2007) [28] reported that FLX (EC10 = 0.81 μg/L) substantially reduced embryo production in the mollusk Potamopyrgus antipodarum. At higher FLX concentrations (69–100 μg/L), offspring production was significantly decreased, whereas lower concentrations (3.7 and 11.1 μg/L) appeared to stimulate embryo production [29]. Despite these insights, the effects of FLX on different life stages of Biomphalaria glabrata, an important water quality indicator in tropical regions, have not been investigated [30,31].

In this study, the selected model organisms represent key ecological roles and varying sensitivities within aquatic ecosystems. Chlorella vulgaris and Microcystis novacekii are primary producers and play a fundamental role at the base of the food web, making them sensitive indicators of pollutant effects at the ecosystem level. Aliivibrio fischeri is a widely used bacterial model for rapid toxicity screening due to its high sensitivity to a range of chemicals. Biomphalaria glabrata is an ecologically relevant mollusk, commonly found in tropical freshwater habitats, and serves as an indicator of water quality and potential impacts on higher trophic levels.

Based on these ecological roles, we hypothesized that FLX would elicit differential toxic effects among taxonomic groups and across life stages, with primary producers and early life stages of mollusks expected to be particularly sensitive. Given the gaps in understanding across multiple taxa, this study aimed to evaluate the ecotoxicity of FLX on Chlorella vulgaris, Microcystis novacekii, Aliivibrio fischeri, and Biomphalaria glabrata, and to estimate the environmental risk of this drug through ecotoxicological risk assessment on a global scale, providing a more comprehensive evaluation of environmental risks and allowing the comparison of sensitivity patterns that reflect the ecological complexity of natural aquatic communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ecotoxicological Assay Set-Up

Fluoxetine hydrochloride (CAS# 59333-67-4) was purchased from Sigma (Table S1). FLX was solubilized in the culture medium of each test organism to ensure osmotic balance between the organism and the test substance. For assays with cyanobacterium M. novacekii, FLX was solubilized in the ASM-1 culture medium [32]. For the bacterium A. fischeri, solubilization was performed in 2% sodium chloride saline solution (ISO/OIN 11348-3/2007) [33], while for the microalgae C. vulgaris it was carried out in BG-11 culture medium with nitrogen [34]. For B. glabrata, FLX was solubilized in chlorine-free filtered water [35].

Solubilization was conducted according to the following steps: FLX was weighed by using an analytical balance (Sartorius BL 210 S, Gottingen/Germany) and added to the culture medium to obtain a stock concentration of 50,000 µg/L. Stock solutions were prepared individually for each assay and homogenization occurred under heating (25 ± 1 °C) and stirring (500 ± 10 rpm) (IKA RT 15, Staufen/Germany) for 10 min.

Once prepared, solutions were diluted in culture medium to obtain final concentrations of 4000; 2000; 1000; 500; 250; 120; 60; 30 and 10 µg/L for A. fischeri; 1000; 100; 10; 1 and 0.1 µg/L for M. novacekii/C. vulgaris; 20,000; 10,000; 1000; 100, 10 and 1 µg/L for B. glabrata embryos and 50,000; 10,000; 5000; 1000; 500; 100 and 50 µg/L for B. glabrata newborns. These concentrations were defined according to a preliminary test carried out to determine concentrations ranges applicable to each of the biological models to provide for more accurate concentration of effect to 50% of test-organisms values (EC50).

Relatively high concentrations of FLX (up to 50,000 µg/L) were used in this study. Although these levels exceed those typically found in aquatic environments, they were employed solely to reach the upper plateau of the dose–response curve, allowing for full validation of the statistical model used. The inclusion of these extreme concentrations is essential to ensure the accuracy of the curve fitting and the reliable determination of the EC50 value, without implying that such levels represent realistic environmental exposure scenarios. Therefore, the results obtained from these concentrations serve only to robustly characterize the compound’s effect, clearly distinguishing hazard identification from environmental risk assessment.

2.2. Sensitivity Test

For the sensitivity test of the bioluminescent bacteria A. fischeri, 2% zinc sulfate (CAS# 7446-20-0), 2% phenol (CAS# 108-95-2) and 2% potassium dichromate (CAS# 7778-50-9) were used as reference substances. Four tests were carried out with the reference substances according to ISO/OIN 11348-3 (2007) [33] using the Microtox® LX equipment (Modern Water, London/UK). For sensitivity tests with the cyanobacterium M. novacekii and microalgae C. vulgaris, potassium dichromate (CAS# 7778-50-9) was used as reference substance at the following concentrations 5000; 2500; 1000; 500 and 100 µg/L, for 96 h and 14 days.

Four tests were carried out with the reference substance in accordance with protocol No. 201 OECD (2011) [36] and NBR 12648 (2018) [37]. Finally, sensitivity tests with B. glabrata were performed using copper sulfate (CAS# 7758-99-8) as reference substance (10,000; 5000; 1000; 500; 100; 50 and 10 µg/L), for 72 h (newborns) and 7 days (embryo) as an adaptation of methods described by Souza-Silva et al. (2023) [35] and Caixeta et al. (2022) [38].

2.3. Aliivibrio fischeri Bioluminescence Inhibition Assay

Acute toxicity assays with bioluminescent marine bacteria A. fischeri were performed by following the Microtox method in accordance with international standard procedure ISO/OIN 11348-3 (2007) [33] using the Microtox LX equipment (Modern Water, London/UK).

Freeze-dried (−20 °C) biomasses of A. fischeri (Biolux Lyo 5 kit, Umwelt—Santa Catarina/Brazil) were removed from the freezer and kept outside until they reached room temperature (25 °C). Then, the culture was resuspended, and bacteria was exposed to different dilutions of FLX, and luminescence was read at 5, 15 and, 30 min. Sodium chloride (CAS# 7647-14-5) (2% v/v), was used as negative control.

2.4. Microcystis novacekii and Chlorella vulgaris Growth Inhibition Assay

Cultures of M. novacekii and C. vulgaris (maintained at the Water Laboratory) were maintained in germination chambers at 23.0 °C ± 2 °C under a photoperiod of 12/12 h (light/dark, light intensity = 45 ± 5 μmol/m/s). The culture medium used for the cultivation and assays were ASM-1 (pH = 8.0 ± 0.2) [32] and BG-11 with nitrogen (pH = 7.5 ± 0.2) [34], respectively. Protocol No. 201 OECD (2011) [36] and NBR 12648 (2018) [37] were followed during tests with modifications.

Initially, 250 mL erlenmeyer flasks were prepared with test dilutions and cultures of M. novacekii or C. vulgaris were added to these flasks to obtain an initial cell density of 106 cells per milliliter. Then, flasks were incubated in triplicate at 22.0 °C ± 1.0 °C under a photoperiod of 12/12 h (light/dark) and constant agitation (140 rpm) for 72 h. Cell growth was evaluated on the first and last day of exposure by assessing optical densities by spectrometry (Spectroquant—Merck Millipore, Darmstadt/Germany) at wavelengths of 680 and 695 nm and cell concentration (cells per milliliter of the sample) by microscopy (Nikon Eclipse E200, Tokyo/Japan) using a Fuchs-Rosenthal Chamber.

Culture concentrations (cells per milliliter) (y) were calculated from the cell density based on previously established growth curves (X) using Equation (1) (R2 = 0.9986) and Equation (2) (R2 = 0.9978) for M. novacekii and C. vulgaris, respectively:

y = 1 × 107 X − 423,719

y = 8 × 106 X − 174,462

Then, average growth rates and growth inhibition curves were constructed as a function of concentrations resulting from exposure. The growth rate coefficient (µ) was calculated after 72 h of exposure. Culture medium ASM-1 and BG-11 (with nitrogen) were used as a negative controls and copper sulfate reagent (1000 µg/L) as positive control.

2.5. Microcystis novacekii and Chlorella vulgaris Recovery Assay

Recovery capacities of the cyanobacterium M. novacekii and microalgae C. vulgaris were evaluated by monitoring absorbance (680 and 695 nm, respectively) of cell cultures daily for 14 days following exposure. Initially, cells were exposed to FLX at concentrations of 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 µg/L in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 106 cells per milliliter of sample (final volume = 100 mL). Then, from the first day (time 0), 0.2 mL aliquots of cell suspension were transferred to 96-well culture plates and the absorbance was read using a Multiskan FC microplate reader (Termo Scientific, Massachusetts, EUA). The negative control was composed of cells without the presence of FLX and the blank was culture medium alone (ASM-1 and BG-11, respectively).

2.6. MTT—Metabolic Activity Assay

Metabolic activity assay was conducted using MTT (1-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-3,5-diphenylformazan, thiazolyl blue) (Sigma Aldrich) with cyanobacteria M. novacekii and the microalgae C. vulgaris by following the method described by Barmshuri et al. (2023) [39] with modifications [40]. MTT solutions (5 mg/mL) were prepared in ASM-1 or BG-11 culture medium for M. novacekii and C. vulgaris, respectively, with the aid of a vortex to solubilize the dye. The solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter.

Cells were exposed to FLX for 72 h under the same conditions applied for the growth inhibition assay, and 1 mL of each group were transferred to 1.5 mL microtubes in triplicate. In each well containing the sample, 50 μL of MTT were added and then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h in the dark. After incubation, the glass tube was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature and supernatants were discarded.

Then, 200 μL of Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solvent were added to the pellets present in the microtubes after incubation for 5 min at room temperature. After this time, microtubes were rigorously shaken using a vortex for 10 s. The microtubes were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature and supernatants were transferred to a 96-well plate reader to measure absorbance spectrophotometrically at 570 nm. Two blanks carried out in triplicate were prepared in this experiment and contained culture medium (ASM-1 or BG-11) and reagents (MTT or DMSO).

2.7. Biomphalaria glabrata (Embryo) Toxicity Assay

B. glabrata, Belo Horizonte lineage, obtained in Pampulha Lake (WGS84 19°51′09″ S; 43°58′42″ W) and maintained for successive generations in the Veterinary Helminthology Laboratory of the Institute of Biological Sciences (ICB) of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) were used in bioassays. Individuals were kept in tanks (0.75 × 0.75 × 0.65 m) containing 200 L of filtered water, free of chlorine, pH 7.1 ± 0.1 and at a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C. Cleaning took place weekly with total replacement of water. All mollusks kept under farming and were fed daily with pesticide-free Lactuca sativa and cleaned with 0.005% acetic acid solution, ad libitum. Once a week, mollusks diet was supplemented by the Pellegrino and Katz (1968) [41] recipe with approximately 200 mg of calcium carbonate per mollusk.

For the toxicity assay with newborns, eggs deposited on styrofoam sheets were gathered from the mollusk breeding aquarium and transferred to another aquarium until hatching. After hatching, 84 newborns (12 newborns per FLX concentration; up to 24 h old), were individually transferred to 24-well culture plates where they were exposed to FLX for 72 h. Newborns were monitored daily to assess mortality and avoidance behavior. Filtered, chlorine-free water was used as a negative control. This experiment was carried out in triplicates. The final volume of solution in each well was 2 mL [35].

For the embryotoxicity assay, eggs deposited on styrofoam sheets and aged up to 6 h, were gathered from the mollusk breeding aquarium, and gently transferred to 24-well culture plates, with one embryo mass per well, totaling approximately 100 embryos by concentration. Then, the embryos were exposed to FLX for 7 days and monitored to evaluate mortality and embryonic malformation. All embryos were observed daily under an optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse E200, Tokyo/Japan) using a 4× and 10× objective lens. Filtered, chlorine-free water was used as a negative control. This experiment was carried out in triplicates. The final volume of solution in each well was 2 mL [38].

2.8. Ecological Risk Assessment (ERA)

ERA is a potential tool to assess the ecological risk of chemicals in the aquatic environment. In this study, ERA was performed based on the calculation of Risk quotients (RQs) (Equation (3)).

RQs = MEC/PNEC

The relationship between measured environmental concentration (MEC) and FLX concentration which does not cause effect (Predicted No effect Concentration—PNEC) [42,43]. For environmental concentration data, reference values of 0.0032 μg/L [5,7] and 43 μg/L were used [13,14,15]. FLX ecological risk was classified in four grades according to the RQ value, as follows: RQ < 0.01, insignificant risk; 0.01 ≤ RQs < 0.1, low risk; 0.1 ≤ RQs < 1, medium risk; and RQs ≥ 1, high risk. PNEC was defined as EC50 values divided by an assessment factor of 1000, for each organism [42].

This conservative factor accounts for uncertainties related to interspecies variability, differences between laboratory and environmental conditions, extrapolation from acute to chronic effects, and the need to protect sensitive taxa, ensuring that the derived PNEC provides a protective threshold for most aquatic organisms [42].

In addition to estimating the environmental risk, starting from the minimum (0.0032 μg/L) or highest (43 μg/L) concentrations reported to occur in the environment, concentrations of FLX reported to occur in water for different locations in all continents were used to estimate the environmental risk under different concentrations and water matrices. The following keywords were used to search for FLX occurrence data: “fluoxetine AND water AND detection”.

Although acute EC50 values are widely applied in ERA as a conservative first-tier screening tool, their use presents important limitations when assessing pharmaceuticals in aquatic environments. Measured environmental concentrations of FLX are typically one to several orders of magnitude lower than acute EC50 values, and short-term toxicity assays may therefore underestimate chronic, sublethal, and life-stage-specific effects resulting from continuous environmental exposure. Despite these limitations, acute EC50-based approaches remain relevant for initial hazard characterization, particularly in the absence of standardized chronic toxicity data across multiple taxonomic groups and when combined with conservative assessment factors.

2.9. Quality Control

Control chart for toxicity assays were prepared based on results published (12 years of study) by the European Chemicals Agency involving 16 different laboratories according to the average values of EC50 obtained for the exposure of microalgae Scenedesmus subspicatus and Selenastrum capricornutum to potassium dichromate for 72 h of exposure [44]. Potassium dichromate is recommended as a reference substance in the inhibition test for microalgae and cyanobacteria [36].

The results obtained for the exposure of cyanobacterium M. novacekii and the microalgae C. vulgaris to potassium dichromate showed a coefficient of variation (CV) < 30%, 30 days prior to the end of experiments, thus validating the test. Considering B. glabrata, copper sulfate was selected as the reference substance for the control chart, as there is no standard method for its use as a biological model in ecotoxicity assays [31].

Regarding bioluminescent bacteria A. fischeri, bioluminescence inhibition observed after exposure to the of reference substances (2% v/v) were 13.6± 0.3, 2.4 ± 0.1 and 59.3 ± 1.2 mg/L for zinc sulfate, phenol, and potassium dichromate, respectively. For cyanobacterium M. novacekii and microalgae C. vulgaris, EC50 values estimated after exposure to reference substances were 890 ± 80 µg/L and 1180 ± 50 µg/L, respectively. For B. glabrata, exposure to copper sulfate for 72 h (newborns) and 7 days (embryos) resulted in a 50% lethal concentration (LC50) equivalent 920 ± 70 µg/L and 53 ± 4 µg/L, respectively.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the software R (version 4.2.1). Initially, a Shapiro–Wilk test was performed to verify the normality of the data. Then, results obtained in each treatment were statistically compared with the negative control group, using analysis of variance for non-parametric data (Kruskal–Wallis). Values of p < 0.05 (95% confidence) were considered as significant different. The log-logistic, log-normal and Weibull models were tested using the “drc” extension package in the statistical software R to estimate the best assembly function. Statistical dose–response regression models represent the relationship between the independent variable (dose or concentration) and the dependent variable (response or effect) [45].

2.11. Use of Artificial Intelligence for Language Assistance

In this study, artificial intelligence (AI), specifically ChatGPT (GPT-4o), was employed to assist with the translation of the manuscript from Portuguese to English. In addition to translation, the AI tool was used to improve grammar, and overall clarity of the English text. All scientific content, data interpretation, and conclusions were generated and verified by the authors, ensuring the intellectual integrity and accuracy of the manuscript.

3. Results

3.1. Fluoxetine Toxicity in Bacteria

At shorter time intervals, such as 5 and 15 min, the highest depleted concentration (4000 µg/L), was not able to inhibit the bioluminescence of this organism by 50%, making it impossible to estimate the EC50 value for these times. However, for the bioluminescence inhibition assay with A. fischeri, the EC50 value was estimated as 3140 ± 1050 (940; 5340) µg/L after 30 min of exposure.

3.2. Fluoxetine Toxicity in Microalgae and Cyanobacteria

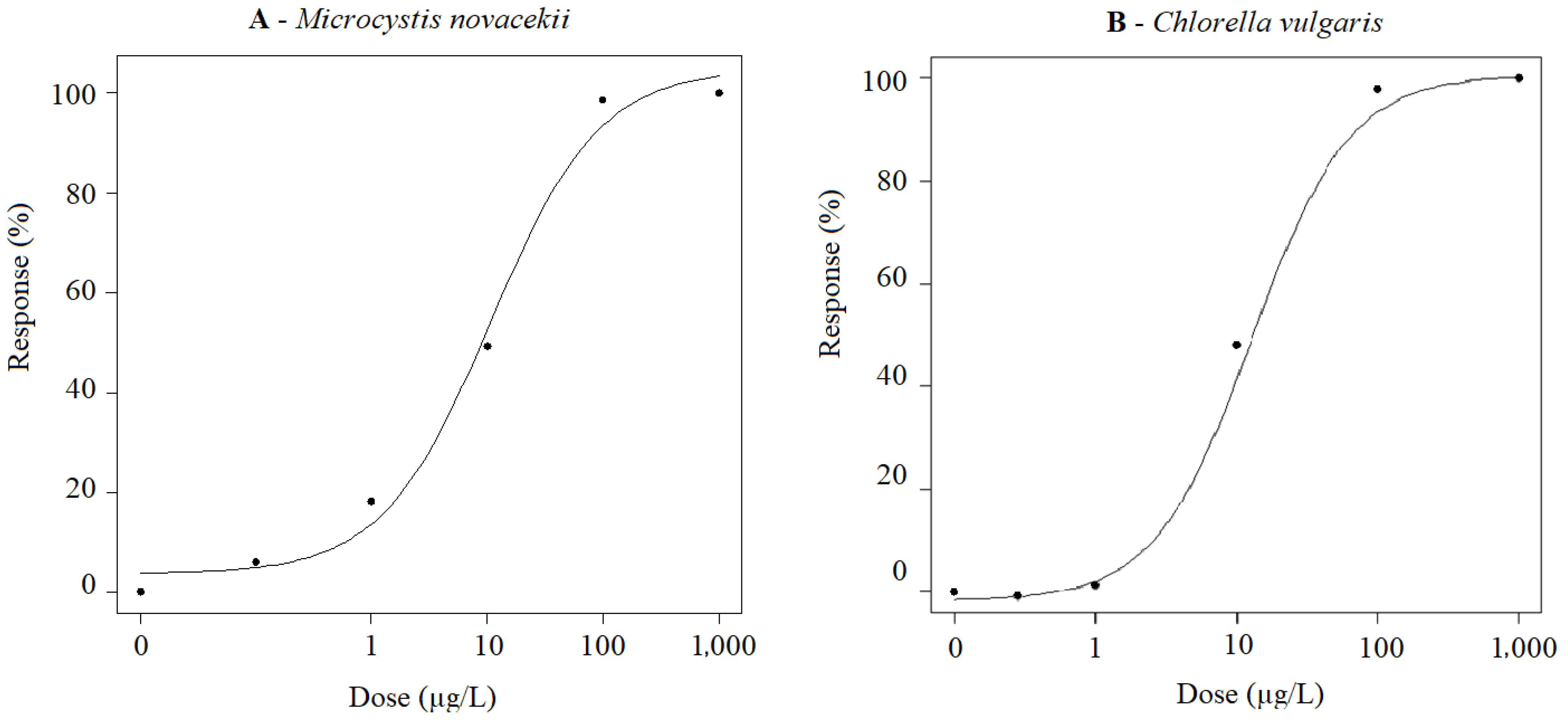

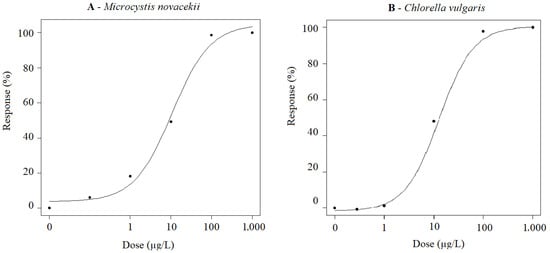

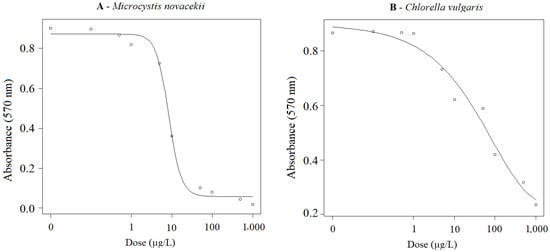

Dose–response curves of growth inhibition of cyanobacterium M. novacekii and microalgae C. vulgaris exposed to FLX are shown in Figure 1. Based on growth inhibition, EC50 values were estimated as 10.71 ± 1.67 (7.11; 14.30) µg/L FLX and 13.01 ± 2.01 (8.81; 17.20) µg/L FLX, respectively, after 72 h of exposure of M novacekii and C. vulgaris to different concentrations of the active ingredient. Concentrations above 1 µg/L showed a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in cell growth for both organisms.

Figure 1.

(A) Dose–response curves of M. novacekii; (B) Dose–response curves of C. vulgaris. Both organisms were exposed to FLX at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1000 µg/L for 72 h under controlled temperature (22.0 °C ± 1.0 °C), photoperiod (12/12 h light/dark) and continuous stirring (140 rpm).

Results indicated that FLX can influence the growth of M. novacekii and C. vulgaris at low concentrations (1 μg/L). Despite the growth inhibition effect, both organisms were able to recover from FLX poisoning, as indicated by the decreasing trend in inhibition rates after prolonged exposure times (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Effects of FLX on the growth of M. novacekii and inhibition rates during 14 days of exposure at concentrations from 1 to 1000 µg/L under controlled conditions of temperature (22.0 °C ± 1.0 °C), photoperiod (12/12 h light/dark) and stirring (140 rpm), incubated for 14 days.

Table 3.

Effects of FLX on the growth of C. vulgaris and inhibition rates during 14 days of exposure at concentrations from 1 to 1000 µg/L under controlled conditions of temperature (22.0 °C ± 1.0 °C), photoperiod (12/12 h light/dark) and stirring (140 rpm), incubated for 14 days.

As observed for the inhibition rate of both cells, EC50 values demonstrated a decreasing trend in inhibition rates with prolonged exposure time, since a smaller concentration of FLX was able to inhibit the growth of 50% of the cells in shorter exposure times compared to longer exposure times (Table 4). Thus, indicating an adaptation of cells to these drugs.

Table 4.

Effect concentration of FLX to 50% of aquatic organisms M. novacekii and C. vulgaris exposed at concentrations ranging from 1 to 1000 µg/L for 14 days under controlled conditions of temperature (22.0 °C ± 1.0 °C), photoperiod (12/12 h light/dark) and stirring (140 rpm).

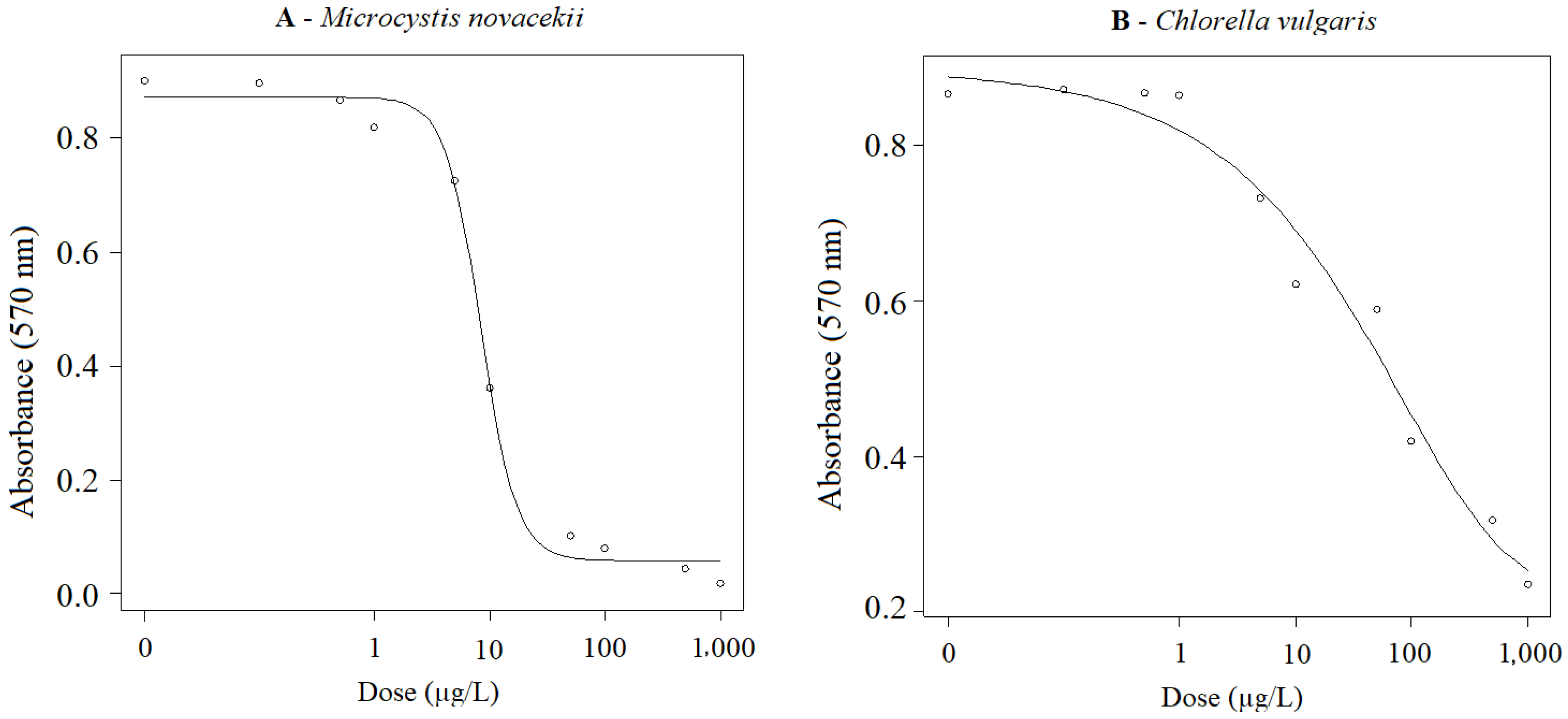

Before and after exposure of cells to FLX to perform the viability and metabolic activity assay, 3 mL aliquots were collected to determine the concentration of cells at the beginning (T0 = 0 h) and at the end (T3 = 72 h) of the exposure. The growth inhibition result in this experiment was like that found in the growth inhibition assay. EC50 values were estimated as 11.12 ± 0.87 (7.02; 14.32) µg/L FLX and 13.01 ± 2.01 (8.81; 17.20) µg/L FLX for M novacekii and C. vulgaris, respectively. In the MTT assay, significant changes in metabolic activity were observed when compared to the negative control group (cells not exposed to FLX). EC50 values were estimated to be 8.37 ± 0.27 (7.83; 8.93) µg/L FLX and 38.18 ± 10.15 (17.33; 59.03) µg/L FLX for M novacekii and C. vulgaris, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Dose–response curves of M. novacekii; (B) Dose–response curves of C. vulgaris. Both organisms were exposed to FLX at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1000 µg/L for 72 h under controlled conditions of temperature (22.0 °C ± 1.0 °C), photoperiod (12/12 h light/dark) and stirring (140 rpm), evaluating metabolic activity through the MTT (5 mg/mL) assay.

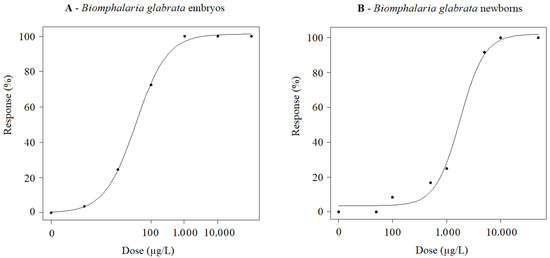

3.3. Fluoxetine Toxicity in Mollusks

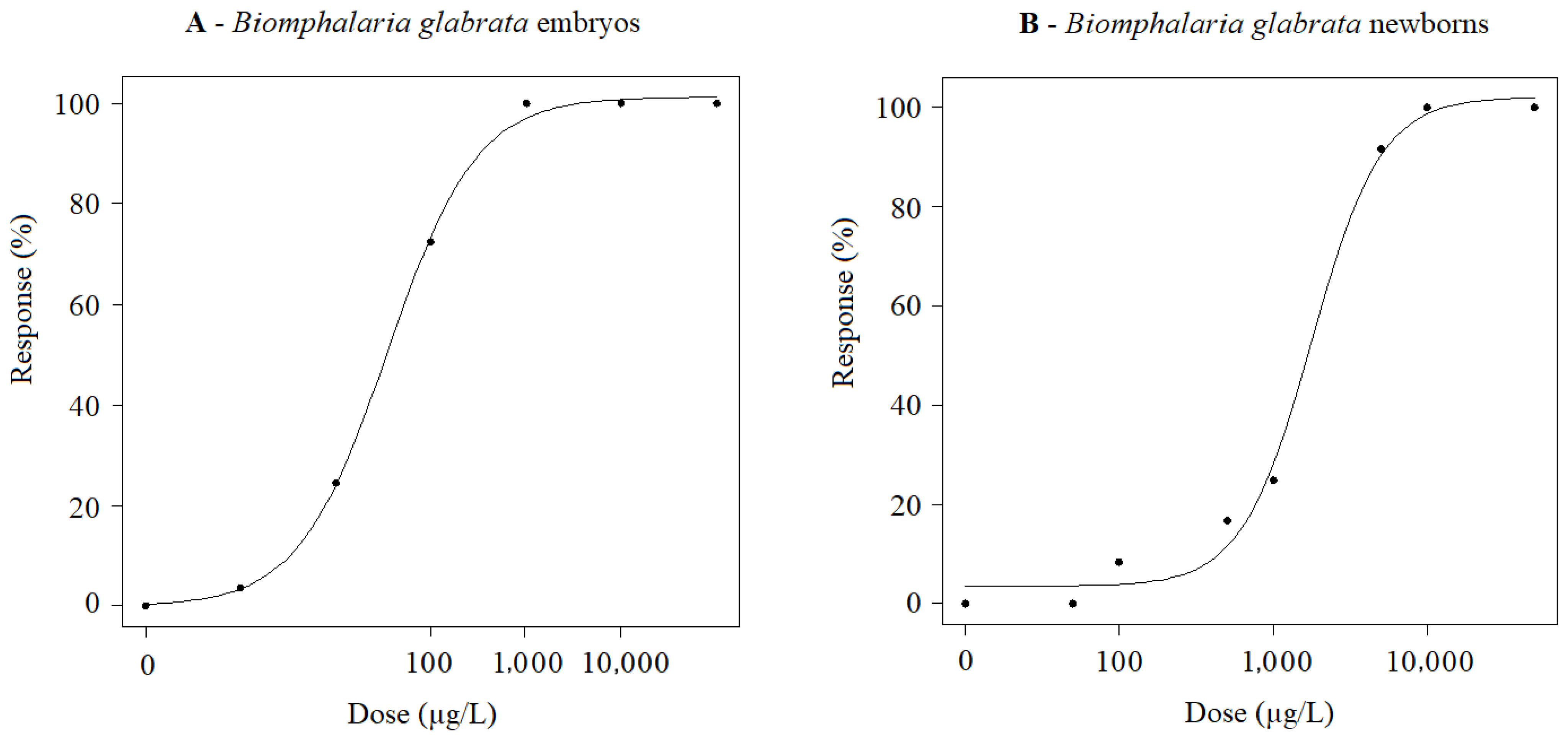

Dose–response curves concerning the lethality of B. glabrata exposed to FLX are shown in Figure 3. For newborn B. glabrata mollusks, exposure to FLX resulted in LC50 values of 1770 ± 260 (1050; 2490) µg/L FLX (Figure 3A). In addition to mortality, 83, 67 and 33% of mollusks were observed out of the water (avoidance behavior) when compared to the control group (8%) for the following FLX concentrations: 10,000, 1000 and 100 µg/L, respectively. As for B. glabrata embryos, the LC50 value was estimated at 34.98 ± 3.66 (23.32; 46.64) µg/L FLX (Figure 3B). It was not possible to observe morphological changes in development at the highest concentrations (10,000 and 1000 µg/L) as lethality reached 100% in less than 24 h of exposure. In contrast, for individuals exposed to 10 and 100 µg/L FLX, main embryonic morphological anomalies were the reduction in shell size, and a delay in embryo hatching time which was significantly higher compared to the negative control group (p-value < 0.05).

Figure 3.

(A) Dose–response curves of B. glabrata (embryos) exposed to FLX at concentrations ranging from 1 to 20,000 µg/L for 7 days under controlled conditions of temperature (25.0 °C ± 2.0 °C), photoperiod (12/12 h light/dark) and pH (7.1 ± 0.1). (B) Dose–response curves of B. glabrata (newborns) exposed to FLX at concentrations ranging from 50 to 50,000 µg/L for 72 h under controlled conditions of temperature (25.0 °C ± 2.0 °C), photoperiod (12/12 h light/dark) and pH (7.1 ± 0.1).

3.4. Ecological Risk Assessment

RQs values obtained for FLX considering EC50 values obtained in this study and the minimum and maximum environmental concentration reported in the scientific literature for FLX (MEC = 0.0032 or 43 μg/L, respectively) [15] are presented in Table 5. FLX represents high-risk for all taxonomic groups in aquatic ecosystems evaluated in this study and cyanobacteria is the group of greatest concern.

Table 5.

Ecological risk quotient (RQ) calculated for fluoxetine on aquatic organisms considering minimum and maximum measured environmental concentrations of 0.0032 and 43 µg/L, respectively, EC50 values obtained in this study as PNEC for each taxonomic group.

ERA commonly employs deterministic hazard quotients to estimate risk, evaluate the probability of adverse effects, and address uncertainties associated with aquatic organism risk assessments [46]. Table 6 presents the values of FLX detected in different types of water bodies around the world and predicted RQs considering EC50 values obtained for cyanobacteria in this study.

Table 6.

Ecological risks of fluoxetine on cyanobacteria considering measured environmental concentration in environmental waters around the world and PNEC as EC50 values obtained in this study for the most sensitive organism (M. novacekii) to FLX (EC50 = 10.71 µg/L).

4. Discussion

4.1. Fluoxetine Toxicity to Microalgae C. vulgaris

The results obtained in this study demonstrate that FLX has a strong inhibitory effect on C. vulgaris growth at concentrations equal to or above 1 µg/L, indicating high sensitivity of this primary producer to pharmaceutical exposure. Based on the 72 h EC50 value below 1000 µg/L, FLX can be classified as “very toxic” to the aquatic environment according to European Union Directive (EUD) 93/67/EEC [47] and the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) [48]. This classification is consistent with previous studies reporting EC50 values below 1000 µg/L for different microalgal species, including Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Raphidocelis subcapitata, and Skeletonema marinoi [4,20,21], reinforcing the high susceptibility of microalgae to FLX exposure.

Although a wide range of EC50 values for microalgae has been reported in the literature, from 1600 to 18,000 µg/L FLX [22], several studies have also documented markedly lower toxicity thresholds, comparable to those observed in the present study. In particular, EC50 values below 1000 µg/L were reported for R. subcapitata and S. marinoi after 72 h of exposure [21], as well as for R. subcapitata [20] and C. pyrenoidosa after 96 h of exposure [4]. This variability highlights species-specific sensitivity and suggests that physiological and taxonomic differences among microalgae may strongly influence FLX toxicity.

When compared with other classes of pharmaceutical residues, including antiretrovirals [49], antibiotics [50], antihypertensives [51], antiepileptics [52], and hormones [53], FLX exhibits some of the lowest EC50 values reported for growth inhibition in microalgae [4,20,21,22]. This finding underscores the particular ecotoxicological concern associated with antidepressants, given their widespread use and continuous release into aquatic environments.

Despite the high acute toxicity observed, some microalgal species, such as C. pyrenoidosa, have demonstrated the ability to recover from FLX exposure over time, as evidenced by decreasing growth inhibition rates during prolonged exposure periods [4]. Similar recovery patterns have been described for microalgae exposed to other organic contaminants, including tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate [54], methylisothiazolinone [55], ciprofloxacin [56], sulfamethoxazole [57], and levofloxacin [58]. Such responses are closely linked to the physiological and biochemical status of the microalgae, including detoxification mechanisms and antioxidant activity [59,60].

The capacity of certain microalgal species to tolerate and recover from pharmaceutical exposure also suggests potential applications in wastewater treatment. Growth recovery and metabolic activity have been associated with effective FLX removal, with reported efficiencies exceeding 77.4% at concentrations up to 200 µg/L [4]. According to Xie et al. (2022) [4], biodegradation represents the primary mechanism of FLX removal by microalgae, surpassing bioadsorption and bioaccumulation. As biodegradation is considered an irreversible process [61], these findings highlight the potential role of microalgae-based systems in mitigating FLX contamination and reducing its environmental persistence.

4.2. Fluoxetine Toxicity to Cyanobacteria M. novacekii

Cell biomass is widely used as an endpoint to assess cyanobacterial growth, and previous studies have consistently shown that cyanobacteria tend to be more sensitive to pharmaceutical residues than eukaryotic primary producers such as green microalgae. Higher sensitivity of cyanobacteria has been reported for different classes of pharmaceuticals, including antibiotics [62,63,64], antiretrovirals [40], and antineoplastic drugs [65], which has been attributed to their prokaryotic cellular organization compared to the more structurally complex eukaryotic microalgal cells.

The findings of the present study corroborate this sensitivity pattern, as M. novacekii exhibited higher susceptibility to FLX than C. vulgaris. This trend was consistently observed not only for FLX exposure but also for the reference substance potassium dichromate, reinforcing the intrinsic vulnerability of cyanobacteria to chemical stressors. According to the classification criteria of the GHS [48] and the EUD [47], FLX can therefore be classified as very toxic to cyanobacteria, which is further supported by the high environmental risk indicated by the risk quotient (RQ) values obtained for M. novacekii (Table 5 and Table 6).

The elevated toxicity of FLX to cyanobacteria may be associated with oxidative stress mechanisms triggered by pharmaceutical exposure. FLX has been shown to interfere with antioxidant defense systems by affecting key enzymes such as glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase, leading to cellular redox imbalance [66]. Increased antioxidant enzyme activity following FLX exposure has been reported for cyanobacteria and microalgae [64], with FLX-induced reactive oxygen species promoting elevated superoxide dismutase activity as a compensatory response [67]. However, such enzymatic responses may be insufficient to counteract excessive intracellular reactive oxygen species, resulting in oxidative damage [68].

Oxidative stress may be further exacerbated by the unique photosynthetic architecture of cyanobacteria. Unlike green microalgae, which possess chloroplasts containing chlorophyll and carotenoids, cyanobacteria rely on phycobilisomes and cytoplasmic thylakoid membranes for photosynthesis [69]. Disruption of photosynthetic processes can promote additional reactive oxygen species formation, impair light harvesting and energy transfer, and ultimately inhibit cell growth [70]. These mechanisms highlight the ecological importance of evaluating the effects of pharmaceutical residues on photosynthetic pigments and physiological performance in cyanobacteria.

Although acute toxicity assays are widely applied, the assessment of chronic toxicity is particularly relevant from an environmental perspective, as it may reveal long-term ecosystem impacts or, conversely, the ability of organisms to recover following prolonged exposure. In the case of M. novacekii, recovery after FLX exposure may reflect adaptive cellular mechanisms and biodegradation capacity, as previously reported for other pharmaceutical residues such as antibiotics [71] and pesticides [72]. Such recovery processes, potentially linked to inherent or acquired cellular adaptation and biodegradation pathways [73], may be explored in biological treatment strategies aimed at mitigating pharmaceutical pollution in aquatic environments.

4.3. Microcystis novacekii and Chlorella vulgaris Poisoning Recovery

The capacity for growth recovery following FLX exposure represents an important aspect of the ecological response of primary producers to pharmaceutical contamination. In the present study, both M. novacekii and C. vulgaris exhibited pronounced growth inhibition during the early stages of exposure, particularly within the first 72 h, indicating high initial sensitivity to FLX. However, when growth inhibition was not complete, a gradual reduction in inhibitory effects was observed over time, suggesting the activation of recovery or adaptive mechanisms in both cyanobacteria and microalgae.

Recovery patterns differed markedly between the two taxa. Cyanobacteria showed a slower and more limited recovery, with reduced inhibition primarily observed at lower FLX concentrations and only after prolonged exposure periods. In contrast, C. vulgaris exhibited a faster and more pronounced recovery response, with growth rates comparable to the control at environmentally relevant concentrations within a shorter time frame. These differences highlight a higher tolerance of microalgae to FLX exposure when compared to cyanobacteria, which may be linked to their eukaryotic cellular organization and greater metabolic flexibility.

Notably, partial recovery was observed even at relatively high FLX concentrations, particularly in microalgae, indicating that growth inhibition induced by acute exposure does not necessarily translate into irreversible effects over longer time scales. Similar recovery responses following pharmaceutical exposure have been reported for C. vulgaris exposed to levofloxacin [58], C. pyrenoidosa exposed to tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate [54], Scenedesmus sp. exposed to methylisothiazolinone [55], Chlamydomonas mexicana exposed to ciprofloxacin [56], and C. pyrenoidosa exposed to FLX [4], suggesting that adaptive or detoxification mechanisms are common among microalgae.

Although both model organisms demonstrated high sensitivity to FLX during the initial exposure period, the greater recovery capacity observed in C. vulgaris indicates a higher tolerance to antidepressant contamination compared to M. novacekii. This differential recovery potential may have important ecological implications, as it can influence species composition, primary productivity, and resilience of aquatic ecosystems under continuous pharmaceutical input. Furthermore, the ability of microalgae to tolerate and partially recover from FLX exposure reinforces their potential application in biological treatment systems aimed at the removal of antidepressants from domestic and industrial effluents [74].

4.4. Microcystis novacekii and Chlorella vulgaris Metabolic Activity

Previous studies have shown that cyanobacteria generally exhibit higher sensitivity to chemical stressors than eukaryotic primary producers such as green microalgae [75,76]. The results of the present study are consistent with this pattern, as FLX affected the metabolic activity of M. novacekii at lower concentrations than those required to inhibit cell growth, whereas in C. vulgaris metabolic impairment occurred at substantially higher concentrations relative to growth inhibition. This divergence suggests taxon-specific differences in cellular metabolism and stress response pathways.

Differences observed in EC50 values derived from the MTT assay are likely related to the mechanisms underlying MTT reduction in photosynthetic organisms. Unlike animal cells, in which MTT reduction is primarily driven by mitochondrial enzymes, photosynthetic cells possess additional redox-active compounds capable of reducing MTT, including antioxidant molecules and photosynthetic pigments such as carotenoids [39]. As a result, metabolic activity estimated by MTT may remain relatively preserved even when growth is already impaired.

Supporting this interpretation, Barmshuri et al. (2023) [39] demonstrated that MTT reduction in Dunaliella spp. occurred throughout the chloroplasts, highlighting the strong influence of photosynthetic structures on this assay. Similarly, Xie et al. (2022) [4] reported that chlorophyll a content in C. pyrenoidosa was not significantly affected at low FLX concentrations, despite significant growth inhibition at comparable exposure levels. These findings are in agreement with the present study, in which growth inhibition occurred at lower concentrations than those affecting metabolic activity.

Together, these results indicate that FLX may initially compromise cell division and growth before causing pronounced impairment of photosynthetic and metabolic functions. The preservation of chlorophyll and redox activity may therefore support partial recovery following exposure, particularly in microalgae. Consequently, both growth-based endpoints and metabolic biomarkers such as chlorophyll content and the MTT assay represent complementary and sensitive tools for assessing microalgal responses to pharmaceutical-induced environmental stress [4,39].

4.5. Fluoxetine Toxicity to Bioluminescent Bacteria A. fischeri

Among the organisms evaluated in this study, the bioluminescent bacterium A. fischeri exhibited the highest tolerance to FLX exposure, as indicated by the comparatively high EC50 value obtained. Nevertheless, despite this apparent resistance, environmentally detected FLX concentrations may still pose ecological concern, as risk quotient values indicate potential risk to A. fischeri even at concentrations reported in surface waters.

The Microtox assay is widely applied in European ecotoxicological assessments due to its rapidity, cost-effectiveness, sensitivity, and reproducibility [77]. Previous studies assessing FLX toxicity to A. fischeri have reported EC50 values within a broad range [78,79], likely reflecting methodological differences such as bioluminescence detection systems and test kits. Despite this variability, all available data consistently confirm that FLX exerts toxic effects on this marine bacterium.

From an environmental management perspective, mitigation of FLX toxicity prior to environmental discharge is particularly relevant. Biodegradation and advanced treatment processes have been shown to reduce acute toxicity to A. fischeri, as demonstrated by the lower toxicity of FLX degradation by-products generated through irradiation [78]. However, although such transformation products exhibit reduced acute toxicity to bacteria, they may still induce chronic effects in higher trophic levels, as evidenced by long-term toxicity to Daphnia magna [78]. These findings emphasize that reductions in acute bacterial toxicity do not necessarily equate to ecological safety and highlight the importance of integrating multi-taxa and chronic endpoints when evaluating treatment efficiency and environmental risk.

4.6. Fluoxetine Toxicity to Mollusk B. glabrata

Mollusks such as B. glabrata are widely used as aquatic bioindicators in ecotoxicological studies due to their broad distribution, ecological relevance, low maintenance costs, and suitability for multiple biological endpoints, including toxicity, cytotoxicity, embryotoxicity, and genotoxicity [31]. In addition to their ecological importance, mollusks also present public health relevance, further supporting their use as model organisms for assessing the environmental risks of pharmaceutical residues.

FLX was among the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors evaluated for its effects on aquatic invertebrates, largely due to its frequent detection in domestic wastewater, industrial effluents, and receiving water bodies. Although numerous studies have assessed the toxicity of pharmaceutical residues in mollusks, comparatively few have focused on reproductive and embryotoxic effects [80], which represent critical endpoints for population sustainability.

In the present study, exposure to high FLX concentrations induced clear behavioral alterations in B. glabrata, characterized by avoidance responses such as emergence from the water column. Such behavioral changes are widely recognized as early indicators of environmental stress and degraded water quality, as they may precede more severe physiological impairment. The use of newborn individuals, however, limited the assessment of reproductive parameters such as fertility and fecundity, highlighting an important methodological constraint.

A marked difference in sensitivity was observed between life stages, with FLX exhibiting substantially higher toxicity to embryos than to newborns. Similar sensitivity patterns were observed for the reference substance, indicating that early developmental stages are inherently more vulnerable to chemical stressors. Increased embryonic sensitivity has been widely reported for plants [81] and for exposure to heavy metals [82], and is often attributed to higher metabolic rates and enhanced uptake of contaminants during early development. These findings emphasize the ecological relevance of including multiple life stages in ecotoxicological assessments, as early-life exposure to pharmaceuticals such as FLX may have disproportionate consequences for mollusk populations and aquatic ecosystem stability.

4.7. Ecological Risk Characterization for Fluoxetine

ERA procedures commonly rely on deterministic approaches, such as hazard or risk quotients, to characterize the likelihood of adverse effects on aquatic organisms and to address uncertainty in risk estimation [46]. Although widely applied as a first-tier screening tool, this approach is inherently limited by the scarcity of comprehensive environmental exposure data and standardized ecotoxicological information, which constrains the use of more refined probabilistic risk assessment frameworks. In this context, the ecotoxicological data generated in the present study contribute to reducing uncertainty and provide a basis for future probabilistic ERA of FLX.

FLX enters aquatic environments primarily through improper disposal of pharmaceutical waste and indirectly through human excretion, reaching wastewater treatment plants where conventional treatment processes are often inefficient at removing this compound [83]. Consequently, FLX has been frequently detected in diverse aquatic matrices, including rivers [5,6,7], surface waters [8,9], effluents and influents [10,11,12], and reservoirs [5]. The increasing availability of occurrence data, combined with ecotoxicological endpoints, allows the estimation of potential ecological risks through the calculation of risk quotients (RQ) [15].

In the present study, RQ calculations were based on the lowest and highest FLX concentrations reported in environmental waters, representing realistic exposure scenarios. Under low-concentration conditions, the potential ecological risk ranged from insignificant to medium depending on the organism and life stage, whereas exposure at the highest reported environmental concentration indicated high risk across all tested taxa. Notably, although the lowest EC50 value obtained for FLX was one order of magnitude higher than most reported environmental concentrations, RQ values frequently exceeded 0.1, indicating medium to high environmental risk. These findings suggest that environmentally detected FLX levels may pose ecological concern, particularly under continuous exposure scenarios.

Regulatory frameworks, such as those adopted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), require environmental risk assessments for new pharmaceuticals only when predicted environmental concentrations exceed 1 µg/L [84]. However, such thresholds do not account for mixture toxicity, additive or synergistic effects of compounds sharing similar modes of action, or interactions among pharmaceuticals with different mechanisms [85,86]. In addition, although multiple taxonomic groups were evaluated in this study, laboratory-based bioassays may not capture the sensitivity of the most vulnerable species or adequately represent complex environmental conditions [46,87]. Long-term and sublethal exposures, even at low concentrations, may therefore be necessary to fully evaluate ecological effects, as chronic exposure can result in physiological and population-level impacts not detected in acute assays [88].

4.8. Ecological Implications and Environmental Relevance

The results of this study demonstrate that FLX poses a potential ecological risk across multiple levels of aquatic biological organization, from microorganisms to invertebrates, with pronounced effects on primary producers and early life stages. The high sensitivity observed in cyanobacteria and microalgae highlights the vulnerability of the base of aquatic food webs to pharmaceutical contamination. Disruption of primary productivity may reduce energy transfer to higher trophic levels, potentially triggering cascading effects that affect community structure, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem functioning [89].

Differential sensitivity among taxonomic groups and life stages further emphasizes the ecological relevance of multi-taxa approaches in environmental risk assessment. Early developmental stages and primary producers responded at lower concentrations than heterotrophic organisms, suggesting that chronic exposure to environmentally relevant FLX concentrations may alter species composition and resilience of aquatic ecosystems even in the absence of acute lethality. Such shifts may have long-term implications for population dynamics and ecosystem stability [90].

From an environmental management perspective, the continuous release of FLX through domestic wastewater represents a significant challenge, particularly in regions where wastewater treatment is inefficient or absent. Conventional treatment processes are often unable to completely remove antidepressants, resulting in persistent low-level contamination of receiving waters [91]. These findings underscore the importance of improving wastewater treatment technologies, promoting proper pharmaceutical disposal, and integrating pharmaceutical residues into routine water quality monitoring programs.

Overall, the integration of ecotoxicological responses across taxa, life stages, and exposure scenarios reinforces the need for precautionary and holistic approaches to environmental management. The ecological effects observed in this study support the inclusion of pharmaceuticals such as FLX in regulatory frameworks and highlight the relevance of combining laboratory-based assessments with environmentally realistic exposure scenarios to better protect aquatic ecosystems.

4.9. Degradation Pathways of FLX

Previous studies [92,93] indicate that FLX exhibits considerable stability under typical aquatic conditions, with low rates of hydrolysis and slow photodegradation. For example, FLX has been reported to degrade less than 10% over 10 days under laboratory conditions simulating sunlight exposure, with half-life values on the order of several days, depending on light intensity, temperature, and water chemistry. Photochemical reactions, including direct photolysis and transformation via hydroxyl radicals, contribute to abiotic degradation but occur relatively slowly compared to the timescale of the experiments performed in this study.

In addition to the evidence of FLX stability discussed above, laboratory investigations of its persistence in aquatic systems have shown that, over a 30-day period, FLX is relatively resistant to both hydrolysis and photolysis in aqueous solutions under both light and dark conditions, except in the presence of humic substances where degradation rates increased modestly compared to buffered water. In water/sediment systems, the majority of FLX removal from the aqueous phase was attributed to adsorption to sediment rather than chemical breakdown, with similar dissipation rates observed under light and dark conditions, indicating a low contribution of abiotic photodegradation to overall FLX loss [94].

These findings confirm that fluoxetine has limited abiotic degradation over the timescales of typical laboratory exposures, corroborating the assumption that nominal concentrations remain close to true exposure levels in the absence of biological uptake or sorption processes. Consequently, although analytical verification in every test vessel was not performed in the present study, the documented persistence and slow rate of abiotic transformation support the reliability of nominal FLX concentrations as representative of actual exposure in our experimental conditions.

Taken together, the available literature indicates that abiotic degradation of FLX in aquatic systems is relatively slow under typical environmental conditions, with photolysis and hydrolysis contributing only modestly to its removal over timescales relevant to laboratory experiments and short-term environmental exposure. While microalgae may enhance FLX removal through biodegradation, the persistence of FLX due to limited abiotic transformation suggests that, in natural environments, compound accumulation could occur if inputs continue. Conversely, discontinuation or significant reduction in FLX inputs could allow for gradual natural attenuation, primarily through combined biotic and abiotic processes over longer periods. Therefore, evaluating both biological and chemical degradation pathways is essential for accurately assessing the environmental risk of FLX and for predicting the potential for natural remediation in aquatic ecosystems.

4.10. Limitations of the Study

This study has some inherent limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, analytical verification of FLX concentrations in all test vessels was not performed due to the unavailability of the required facilities. However, literature data and previous experience with similar experimental setups indicate that measured concentrations of FLX are typically very close to nominal values, with recovery rates often exceeding 90%. This supports the use of nominal concentrations as a reliable approximation of actual exposure in our experiments.

Second, while our study focused on the potential contribution of microalgae to FLX biodegradation, it did not experimentally address abiotic degradation processes such as photolysis, hydrolysis, and oxidation via natural radicals. Literature evidence indicates that these processes occur relatively slowly under typical environmental conditions, suggesting that FLX persistence may be primarily influenced by biotic processes over short-term exposures. Nevertheless, understanding both biotic and abiotic pathways is important for assessing long-term environmental fate, and future studies should integrate these aspects to further refine ecological risk assessments.

Although the specific mechanisms of FLX biodegradation were not deeply investigated in this study, our work was designed with the primary objective of evaluating the ecotoxicity of FLX on Chlorella vulgaris, Microcystis novacekii, Aliivibrio fischeri, and Biomphalaria glabrata, and to estimate the environmental risk of this drug through ecotoxicological risk assessment on a global scale. As a result, significant toxicity was observed, including sub-lethal effects and damage across different life stages and taxonomic groups, providing robust evidence of FLX’s potential ecological impact.

Overall, despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the effects of FLX on aquatic primary producers and contributes to understanding the role of microalgae in pharmaceutical biodegradation, offering a robust basis for further environmental risk evaluations.

5. Conclusions

The study evaluated ecotoxicity of FLX to the aquatic organisms A. fischeri, C. vulgaris, M. novacekii and B. glabrata (newborns and embryos). Considering EC50 values obtained for all test organisms and concentrations of FLX reported for different water bodies around the world, high toxicity and ecological risk were detected for different taxonomic groups in this study. Therefore, it is critical to prevent the discharge of this pollutant to the environment. According to the criteria of European Union Directive 93/67/EEC (47) and Annex 2.28(b) of the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals, FLX is “toxic” or “very toxic” for the environment. The use of biochemical, immunological and/or genetic biomarkers should be considered to allow for early detection of effects promoted by FLX and other antidepressants in the environment, thus improving response time and effectiveness. As a solution to prevent the FLX discharge into the environment, microalgae, such as C. vulgaris, can be used in biological reactors to remove the drug, as this organism was more resistant and showed a better poisoning recovery rate than cyanobacteria. Finally, the assessment of the metabolic activity of cells (biochemical biomarkers), using the MTT dye, demonstrated to be viable and sensitive for environmental assessments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13010010/s1, Table S1: Physicochemical properties of fluoxetine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.-S.; methodology, G.S.-S., C.R.d.S. and D.d.C.; software, G.S.-S. and M.P.G.M.; validation, G.S.-S., M.D.A. and C.A.d.J.P.; formal analysis, G.S.-S.; investigation, M.P.G.M.; data curation, M.D.A. and F.R.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S.-S. and M.C.V.M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.R.S., D.d.C., F.R.-S. and M.P.G.M.; supervision, G.S.-S. and M.C.V.M.S.; project administration, M.R.S.; funding acquisition, M.R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), grant number 403853/2023-0, and the Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG), grant numbers APQ-03069-23 and BIP-00012-24.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to their association with ongoing research projects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank undergraduate students Vieira J.M.A. and Soares I.V. for their technical support in carrying out the tests in this study. We also thank the Postgraduate Program in Medicines and Pharmaceutical Assistance and the Water Analysis Laboratory—UFMG for the financial support to carry out this project. We acknowledge ChatGPT (GPT-4o) for assistance in translating the manuscript from Portuguese to English.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Depression. Depressive Disorder (Depression). 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Wisner, K.L.; Schaefer, C. Psychotropic Drugs. In Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 293–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, K.F.O.; de Almeida, G.L.M.; Henriques, M.B.; Barbieri, E. Effect of Fluoxetine Hydrochloride on Routine Metabolism of Lambari (Deuterodon iguape, Eigenmann, 1907) and Phantom Shrimp (Palaemon pandaliformis, Stimpson, 1871). Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2021, 64, e21200262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, X.; Gan, Y.; Cheng, H.; Fan, S.; Li, X.; Tang, J. Ecotoxicological effects of the antidepressant fluoxetine and its removal by the typical freshwater microalgae Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 244, 114045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, R.C.; Godoy, A.A.; Kummrow, F.; dos Santos, T.L.; Brandão, C.J.; Pinto, E. Occurrence of caffeine, fluoxetine, bezafibrate and levothyroxine in surface freshwater of São Paulo State (Brazil) and risk assessment for aquatic life protection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 20751–20761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.J.; Paíga, P.; Silva, A.; Llaguno, C.P.; Carvalho, M.; Vázquez, F.M.; Delerue-Matos, C. Antibiotics and antidepressants occurrence in surface waters and sediments collected in the north of Portugal. Chemosphere 2020, 239, 124729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giebułtowicz, J.; Nałęcz-Jawecki, G. Occurrence of antidepressant residues in the sewage-impacted Vistula and Utrata rivers and in tap water in Warsaw (Poland). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 104, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I.; Thurman, E.M. Analysis of 100 pharmaceuticals and their degradates in water samples by liquid chromatography/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1259, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpin, D.W.; Furlong, E.T.; Meyer, M.T.; Thurman, E.M.; Zaugg, S.D.; Barber, L.B.; Buxton, H.T. Pharmaceuticals, Hormones, and Other Organic Wastewater Contaminants in U.S. Streams, 1999−2000: A National Reconnaissance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringolf, R.B.; Heltsley, R.M.; Newton, T.J.; Eads, C.B.; Fraley, S.J.; Shea, D.; Cope, W.G. Environmental occurrence and reproductive effects of the pharmaceutical fluoxetine in native freshwater mussels. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, M.; Cologgi, D.L.; Lu, W.; Smith, D.W.; Ulrich, A.C. Pharmaceuticals in Canadian sewage treatment plant effluents and surface waters: Occurrence and environmental risk assessment. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2013, 2, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajeunesse, A.; Smyth, S.A.; Barclay, K.; Sauvé, S.; Gagnon, C. Distribution of antidepressant residues in wastewater and biosolids following different treatment processes by municipal wastewater treatment plants in Canada. Water Res. 2012, 46, 5600–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aus der Beek, T.; Weber, F.A.; Bergmann, A.; Hickmann, S.; Ebert, I.; Hein, A.; Küster, A. Pharmaceuticals in the environment—Global occurrences and perspectives. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Ruan, Y.; Lin, H.; Yuen, C.N.T.; Feng, H.; Lam, P.K.S. Occurrence and Fate of Psychiatric Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Treatment Plants in Hong Kong: Enantiomeric Profiling and Preliminary Risk Assessment. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, I.A.; Fick, J.; Cabral, H.N.; Fonseca, V.F. Bioconcentration of neuroactive pharmaceuticals in fish: Relation to lipophilicity, experimental design and toxicity in the aquatic environment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 812, 152543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Gautam, L.; Hall, S.W. The detection of drugs of abuse and pharmaceuticals in drinking water using solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Zacarías, C.; Barocio, M.E.; Hidalgo-Vázquez, E.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Parra-Arroyo, L.; López-Pacheco, I.Y.; Barceló, D.; Iqbal, H.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Antidepressant drugs as emerging contaminants: Occurrence in urban and non-urban waters and analytical methods for their detection. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.M.; Bertram, M.G.; Saaristo, M.; Fursdon, J.B.; Hannington, S.L.; Brooks, B.W.; Burket, S.R.; Mole, R.A.; Deal, N.D.S.; Wong, B.B.M. Antidepressants in Surface Waters: Fluoxetine Influences Mosquitofish Anxiety-Related Behavior at Environmentally Relevant Levels. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6035–6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.M.; Nagarajan-Radha, V.; Tan, H.; Bertram, M.G.; Brand, J.A.; Saaristo, M.; Dowling, D.K.; Wong, B.B. Antidepressant exposure causes a nonmonotonic reduction in anxiety-related behaviour in female mosquitofish. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 2020, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villain, J.; Minguez, L.; Halm-Lemeille, M.P.; Durrieu, G.; Bureau, R. Acute toxicities of pharmaceuticals toward green algae. mode of action, biopharmaceutical drug disposition classification system and quantile regression models. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 124, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minguez, L.; Pedelucq, J.; Farcy, E.; Ballandonne, C.; Budzinski, H.; Halm-Lemeille, M.P. Toxicities of 48 pharmaceuticals and their freshwater and marine environmental assessment in northwestern France. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 4992–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miazek, K.; Brozek-Pluska, B. Effect of PHRs and PCPs on Microalgal Growth, Metabolism and Microalgae-Based Bioremediation Processes: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Huang, G.; Zhang, B. Review of aquatic toxicity of pharmaceuticals and personal care products to algae. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 410, 124619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.J.; Sanderson, H.; Brain, R.A.; Wilson, C.J.; Solomon, K.R. Toxicity and hazard of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and sertraline to algae. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2007, 67, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minguez, L.; Bureau, R.; Halm-Lemeille, M.P. Joint effects of nine antidepressants on Raphidocelis subcapitata and Skeletonema marinoi: A matter of amine functional groups. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 196, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuwoehner, J.; Escher, B.I. The pH-dependent toxicity of basic pharmaceuticals in the green algae Scenedesmus vacuolatus can be explained with a toxicokinetic ion-trapping model. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 101, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couper, J.M.; Leise, E.M. Serotonin Injections Induce Metamorphosis in Larvae of the Gastropod Mollusc Ilyanassa obsoleta. Biol. Bull. 1996, 191, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nentwig, G. Effects of Pharmaceuticals on Aquatic Invertebrates. Part II: Antidepressant Drug Fluoxetine. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 52, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gust, M.; Buronfosse, T.; Giamberini, L.; Ramil, M.; Mons, R.; Garric, J. Effects of fluoxetine on the reproduction of two prosobranch mollusks: Potamopyrgus antipodarum and Valvata piscinalis. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, V.H.T.; de Luna Filho, R.L.C.; dos Santos Júnior, J.A.; Siqueira, W.N.; Pereira, D.R.; Lima, M.V.; Fagundes Silva, H.A.M.; Joacir de França, E.; Amaral, R.d.S.; de Albuquerque Melo, A.M.M. Use of Biomphalaria glabrata as a bioindicator of groundwater quality under the influence of NORM. J. Environ. Radioact. 2022, 242, 106791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Silva, G.; de Souza, C.R.; Pereira, C.A.D.J.; dos Santos Lima, W.; Mol, M.P.G.; Silveira, M.R. Using freshwater snail Biomphalaria glabrata (Say, 1818) as a biological model for ecotoxicology studies: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 28506–28524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, W.W.; Gorham, P.R. An Improved Method for Obtaining Axenic Clones of Planktonic Blue-Green Algae1,2. J. Phycol. 1974, 10, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Quality—Determination of the Inhibitory Effect of Water Samples on the Light Emission of Vibrio Fischeri (Luminescent Bacteria Test)—Part 3: Method Using Freeze-Dried Bacteria (ISO11348-3:2007) 14:00-17:00. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/73342.html (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Rippka, R.; Deruelles, J.; Waterbury, J.B.; Herdman, M.; Stanier, R.Y. Generic Assignments, Strain Histories and Properties of Pure Cultures of Cyanobacteria. Microbiology 1979, 111, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Silva, G.; Souza, C.R.; Pereira, C.A.d.J.; Lima, W.d.S.; Mol, M.P.G.; Silveira, M.R. Toxicological evaluation of antiretroviral Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate on the mollusk Biomphalaria glabrata and its hemocytes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Test No. 201: Freshwater Alga and Cyanobacteria, Growth Inhibition Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (ABNT). Norma Técnica nº 12648: Ecotoxicologia Aquática—Toxicidade Crônica—Método de Ensaio com Algas (Chlorophyceae); ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Caixeta, M.B.; Araújo, P.S.; Pereira, A.C.; Tallarico, L.d.F.; Rocha, T.L. Biomphalaria embryotoxicity test (BET): 60 years of research crossing boundaries for developing standard protocols. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barmshuri, M.; Kholdebarin, B.; Sadeghi, S. Applications of comet and MTT assays in studying Dunaliella algae species. Algal Res. 2023, 70, 103018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Silva, G.; Alcantara, M.D.; Souza, C.R.d.; Moreira, C.P.d.S.; Nunes, K.P.; Pereira, C.A.d.J.; Mol, M.P.G.; Silveira, M.R. Toxicity of the Antiretrovirals Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate, Lamivudine, and Dolutegravir on Cyanobacterium Microcystis novacekii. Water 2025, 17, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, J.; Katz, N. Experimental chemoterapy of Schistosomiasis mansoni. Adv. Parasitol. 1968, 6, 233–290. [Google Scholar]

- Riva, F.; Zuccato, E.; Davoli, E.; Fattore, E.; Castiglioni, S. Risk assessment of a mixture of emerging contaminants in surface water in a highly urbanized area in Italy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 361, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, T.; Faust, M. Predictive Environmental Risk Assessment of Chemical Mixtures: A Conceptual Framework. Environ. Sci Technol. 2012, 46, 2564–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECHA; European Chemicals Bureau. European Union Risk Assessment Report: Chromium Trioxide, Sodium Chromate, Sodium Dichromate, Ammonium Dichromate and Potassium Dichromate. 3rd. Priority List; 2005; Volume 53. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/registration-dossier/-/registered-dossier/15102/6/2/6 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Ritz, C.; Baty, F.; Streibig, J.C.; Gerhard, D. Dose-Response Analysis Using R. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0146021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.W.; Foran, C.M.; Richards, S.M.; Weston, J.; Turner, P.K.; Stanley, J.K.; Solomon, K.R.; Slattery, M.; La Point, T.W. Aquatic ecotoxicology of fluoxetine. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 142, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Technical Guidance Document in support of Commission Directive 93/67/EEC on Risk Assessment for New Notified Substances and Commission Regulation (EC) No. 1488/94 on Risk Assessment for Existing Substances. Part II: Environmental Risk Assessment. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. 1996; ISBN 92-827-8012-0. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC23785 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- United Nations. Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), 8th ed.; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, K.; Renuka, N.; Kumari, S.; Ratha, S.K.; Moodley, B.; Pillay, K.; Bux, F. Assessing the potential for nevirapine removal and its ecotoxicological effects on Coelastrella tenuitheca and Tetradesmus obliquus in aqueous environment. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, H.T.; Hou, J.H.; Su, C.I.; Chen, C.L. Effects of chloramphenicol, florfenicol, and thiamphenicol on growth of algae Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Isochrysis galbana, and Tetraselmis chui. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009, 72, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodowska, J.; Wilczok, A.; Tam, I.; Cwalina, B.; Swiatkowska, L.; Wilczok, T. Alteration of growth and metabolic activity of cells in the presence of propranolol and metoprolol. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2003, 60, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Lin, K.; Sun, W.; Xiong, B.; Guo, M.; Cui, X.; Fu, R. Eco-toxicological effect of Carbamazepine on Scenedesmus obliquus and Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 33, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarny, K.; Szczukocki, D.; Krawczyk, B.; Skrzypek, S.; Zieliński, M.; Gadzała-Kopciuch, R. Toxic effects of single animal hormones and their mixtures on the growth of Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus armatus. Chemosphere 2019, 224, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Chang, F.; Yi, M.; Ge, H.; Fu, J.; Dang, C. The distinct resistance mechanisms of cyanobacteria and green algae to sulfamethoxazole and its implications for environmental risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Zhang, T.Y.; Dao, G.H.; Hu, H.Y. Tolerance and resistance characteristics of microalgae Scenedesmus sp. LX1 to methylisothiazolinone. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.Q.; Kurade, M.B.; Kim, J.R.; Roh, H.S.; Jeon, B.H. Ciprofloxacin toxicity and its co-metabolic removal by a freshwater microalga Chlamydomonas mexicana. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 323, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Liu, Y.S.; Hu, L.X.; Shi, Z.Q.; Cai, W.W.; He, L.Y.; Ying, G.-G. Co-metabolism of sulfamethoxazole by a freshwater microalga Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Water Res. 2020, 175, 115656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.Q.; Kurade, M.B.; Jeon, B.H. Biodegradation of levofloxacin by an acclimated freshwater microalga, Chlorella vulgaris. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 313, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, K.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, P.; Han, J. Removal mechanisms of erythromycin by microalgae Chlorella pyrenoidosa and toxicity assessment during the treatment process. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.X.; Dao, G.H.; Zhuang, L.L.; Zhang, T.Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Hu, H.Y. Enhanced simultaneous removal of nitrogen, phosphorous, hardness, and methylisothiazolinone from reverse osmosis concentrate by suspended-solid phase cultivation of Scenedesmus sp. LX1. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, D.L.; Ralph, P.J. Microalgal bioremediation of emerging contaminants—Opportunities and challenges. Water Res. 2019, 164, 114921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de-Bashan, L.E.; Bashan, Y. Immobilized microalgae for removing pollutants: Review of practical aspects. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1611–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, M.; Rioboo, C.; Herrero, C.; Cid, Á. Toxicity induced by three antibiotics commonly used in aquaculture on the marine microalga Tetraselmis suecica (Kylin) Butch. Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 101, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; Xu, F.; Xu, H.; Zheng, X.; Wang, L. Ecotoxicological effects of sulfonamides and fluoroquinolones and their removal by a green alga (Chlorella vulgaris) and a cyanobacterium (Chrysosporum ovalisporum). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezovšek, P.; Eleršek, T.; Filipič, M. Toxicities of four anti-neoplastic drugs and their binary mixtures tested on the green alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata and the cyanobacterium Synechococcus leopoliensis. Water Res. 2014, 52, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, B.N.; Mehta, S.K.; Amar, A.; Gaur, J.P. Oxidative stress in Scenedesmus sp. during short- and long-term exposure to Cu2+ and Zn2+. Chemosphere 2006, 62, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijão, E.; Cruz de Carvalho, R.; Duarte, I.A.; Matos, A.R.; Cabrita, M.T.; Novais, S.C.; Lemos, M.F.L.; Caçador, I.; Marques, J.C.; Reis-Santos, P.; et al. Fluoxetine Arrests Growth of the Model Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum by Increasing Oxidative Stress and Altering Energetic and Lipid Metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Li, Z.; Juneau, P.; Xiao, F.; Lian, Y.; Zhang, W.; Shu, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, C.; et al. Toxic and protective mechanisms of cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. in response to titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 274, 116508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.; Hurry, V.; Clarke, A.K.; Gustafsson, P.; Öquist, G. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analysis of Cyanobacterial Photosynthesis and Acclimation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Sabu, S.; Sangela, V.; Meena, M.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Vinayak, V.; Harish. The mechanism of nanoparticle toxicity to cyanobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 2022, 205, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, F.C.R.; Vaz, I.C.D.; Barbosa, F.A.R.; Magalhães, S.M.S. Toxicological effects of ciprofloxacin and chlorhexidine on growth and chlorophyll a synthesis of freshwater cyanobacteria. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 55, e17661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, B.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Qian, H. Pollutant toxicology with respect to microalgae and cyanobacteria. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 99, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckellar, Q.A.; Sanchez Bruni, S.F.; Jones, D.G. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships of antimicrobial drugs used in veterinary medicine. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 27, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, H.; Sousa, C.A.; Simões, L.C.; Simões, M. Microalgal-based removal of contaminants of emerging concern. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Ke, M.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, T.; Chen, J.; Qian, H. Evaluation of the taxonomic and functional variation of freshwater plankton communities induced by trace amounts of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Li, J.; Pan, X.; Sun, Z.; Ye, C.; Jin, G.; Fu, Z. Effects of streptomycin on growth of algae Chlorella vulgaris and Microcystis aeruginosa. Environ. Toxicol. 2012, 27, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalbán, M.G.; Hidalgo, J.M.; Collado-González, M.; Díaz Baños, F.G.; Víllora, G. Assessing chemical toxicity of ionic liquids on Vibrio fischeri: Correlation with structure and composition. Chemosphere 2016, 155, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.R.A.; Garcia, V.S.G.; Vilarrubia, A.C.S.; Borrely, S.I. Reduction of Acute Toxicity of the Pharmaceutical Fluoxetine (Prozac) Submitted to Ionizing Radiation to Vibrio fischeri; Associação Brasileira de Energia Nuclear: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]