Abstract

Carnauba (Copernicia spp.) is a palm tree native to the Brazilian semi-arid region, valued for its significant economic, social, and environmental importance. This resilient species possesses adaptive mechanisms that enable it to endure prolonged periods of soil water scarcity and conditions of flooding and salinity. However, despite its relevance, there is a notable lack of scientometric data on this species in the literature, representing a significant research gap. This study aimed to analyze the state of research on carnauba palm from 2007 to 2022. Datasets were collected from the Web of Science central database, totaling 658 publications related to the terms “carnauba” or “copernicia”. The bibliometric software VOSviewer was used to create visual maps of keyword co-occurrence networks, providing deeper insights into the progress and research trends on the topic. Since 2014, the number of publications on carnauba has steadily increased, peaking between 2019 and 2021. The most prominent focus in these articles is on carnauba wax, with extensive research on its properties and applications in the food production chain. This significance is also reflected in the keyword co-occurrence networks. However, studies combining carnauba with soil sciences remain underexplored. Given carnauba’s importance in environmental and soil conservation, future research linking these areas could become a key avenue for advancing knowledge on the subject.

1. Introduction

Carnauba is a palm tree belonging to the genus Copernicia, a group of plants that occurs in various regions of the world, such as South America, Equatorial Africa, and South Asia. Copernicia prunifera is endemic to Brazil and occurs in the Northeast, Central-West, and North regions, in the Caatinga and Cerrado biomes [1].

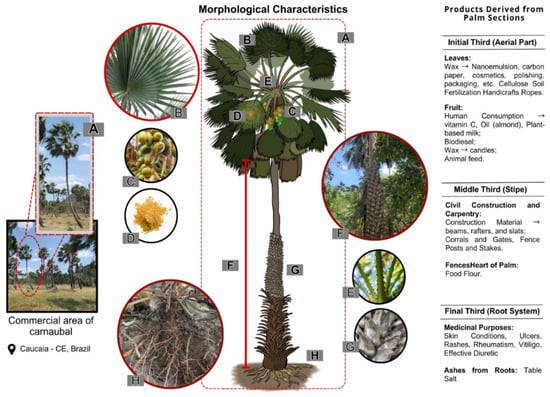

Due to its diverse uses, the carnauba palm has significant economic, social, and environmental relevance. Economically, the exploitation of this palm tree involves activities that utilize the leaves, stem, fiber, fruit, and roots to produce a wide range of products (Figure 1). The primary product of the carnauba palm is its wax, which is obtained through the extraction and processing of the wax powder that forms on the surface of the leaves. This wax plays a crucial role in preventing excessive water loss through evapotranspiration, especially during the dry season and in high temperatures [2]. In 2021, Brazil produced approximately 640 tons of carnauba wax, with a production value exceeding BRL 278 million [3].

Figure 1.

Morphological detailing, products, and by-products of carnauba (Copernicia prunifera (Mill.) H.E. Moore). A—Complete view of the carnauba palm tree; B—leaves; C—fruits; D—ceriferous layer that forms on the surface of the leaves in detail; E—petiole with thorns in detail; F—trunk without branches, in the upper part marked by scars left by leaves that have completely fallen, and in the lower part with leaf sheaths that have not yet fallen; G—detail of the trunk with dry hems that did not fall; H—roots.

Native carnauba palms are crucial for protecting and preserving the diversity and natural resources of the environment [4]. They contribute significantly to soil conservation by preventing erosion and the silting of rivers [5]. In the semi-arid region, carnauba grows in floodable areas with halomorphic soils and is considered a bioindicator of salinity. It can also be used for the recovery of degraded areas with high salt content [6]. However, despite its relevance to the semi-arid region and its widespread exploration in scientific studies worldwide, research focusing on carnauba in conjunction with soil sciences remains limited.

Bibliometric analyses are commonly employed to identify emerging trends in scientific publications and journals, examine collaboration patterns between authors and research institutions, and explore the intellectual structure of a specific subject within the existing literature [7]. These analyses are valuable for understanding and mapping the accumulated scientific knowledge and its evolution in well-established fields, enabling the systematic interpretation of large volumes of unstructured data. Consequently, bibliometric studies can provide a robust foundation for advancing a particular topic in innovative and meaningful ways [7]. Bibliometric methods have been successfully applied in environmental and ecological studies, including analyses of soil conservation [8], ecosystem services in Brazil [9], trends in microbial inoculants used in agriculture [10], and soil health [11]. Importantly, bibliometric studies require careful methodological choices, including database selection, precise search terms, and transparent inclusion/exclusion criteria, as these decisions directly affect the reliability of the results [7].

In this context, the objective of this study was to identify influential countries, institutions, authors, and journals, as well as citations, key authors, and high-frequency keywords, in studies involving carnauba. Additionally, the study aimed to provide a comprehensive and clear understanding of the characteristics of the current state of research, highlighting critical points and development trends in studies on the subject. This study provides the first bibliometric mapping of scientific research on Copernicia prunifera, identifying dominant themes, research gaps, and opportunities for future studies. We reveal that while carnauba wax applications are extensively explored, ecological and soil-related research remains scarce, highlighting a clear research gap. The data obtained are fundamental for supporting the conservation of these species, offering insights that can guide future research and management practices for carnauba and its ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

To understand the current state and to outline trends in research involving carnauba, scientific papers present in the Web of Science (WoS) database platform were considered, published in the last 15 years (period from 2007 to 2022). Based on the bibliometric indicators, it is possible to illustrate the distribution of publications, most cited publications, and keywords, among other things [12]. The bibliometric research retrieved publications from 2007 to 2022, which corresponds to the most recent 15-year period with consistent scientific output on Copernicia prunifera. To enable comparative analysis among time periods of the same length, the dataset was segmented into three uniform 5-year intervals (2007–2011, 2012–2016, and 2017–2022). Five-year windows are frequently used in bibliometric studies because they minimize yearly fluctuations and allow for the detection of medium-term trends in research dynamics. The segmentation was, therefore, not arbitrary but defined to ensure temporal homogeneity and allow for comparisons among periods that represent different developmental stages of the research field.

The bibliometric search followed the PRISMA framework [13]. In the Identification stage, 1395 records were retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection using the keywords “carnauba” OR “copernicia” (topic search: title/abstract/keywords). During Screening, 584 records were removed because they belonged to unrelated subject categories (e.g., hotel industry, art, education, humanities). No duplicate records were detected. In the Eligibility stage, 811 records were screened by title and abstract, and 784 full texts were assessed. Finally, 658 studies met the inclusion criteria (articles, review articles, proceeding papers, data papers, written in English or Portuguese) and were included in the bibliometric dataset. The search strategy prioritized taxonomically validated descriptors to avoid retrieving documents referring to other palm species commonly also labeled as “wax palm”. A PRISMA flow diagram summarizing this process is shown in Figure S1, and a summary of the sources and selection of data can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the sources and selection of data obtained from the Web of Science database using the keywords “copernicia” and “carnauba”, from 2007 to 2022.

The data were exported into text document format (.txt) for further processing in the VOSviewer© platform. VOSviewer version 1.8.0 411 (accessed on 18 April 2023) is a JAVA-based software developed in 2009 by Van Eck and Waltman at the Center for Scientific and Technological Studies (CWTS) at Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands, that targets visual network analysis for literature data. Clustering in VOSviewer is calculated based on association strength, and its visualization mapping image is a method of presenting information in terms of co-occurrence weights and total connection strength between items, which can be used to understand the impact and strength of relationships between different article attributes [8]. In this study, keyword co-occurrence network and keyword co-occurrence network overtime analyses were used, dividing the years 2007 to 2022 into four different periods to observe trends. Finally, we performed a co-citation analysis, where only studies with at least five citations were retained in the network. Collaboration networks were generated using the organization-level co-authorship option.

Considering Brazil a leading nation in the exploration of carnauba, an analysis of keyword co-occurrence over time was also performed exclusively for studies conducted in the country. Still with the objective of analyzing the situation of publications that directly relate to carnauba and soil sciences, a search was also performed in the Web of Science database using the terms “copernicia”, “carnaúba”, and “soil” in the search field topics (title, abstract, and keywords). The keyword co-occurrence network was also generated in VOSviewer (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the sources and selection of data obtained from the Web of Science database using the keywords “copernicia”, “carnauba”, and “soil”, from 2007 to 2022.

3. Results and Discussion

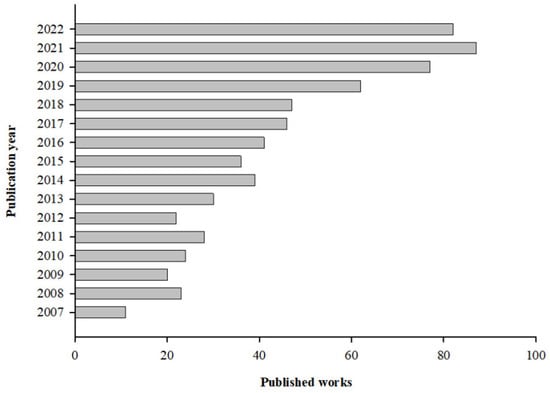

For at least 15 years, few studies involving carnauba were published, a trend that continued from the late 2000s to the early 2010s. Starting in 2014, the number of articles published on carnauba increased considerably. This increase continued in the following years, reaching its peak between 2019 and 2021 (Figure 2). All parts of the carnauba tree can be used to generate products, but the main one comes from the extraction of the wax that covers its leaves [14]. Considered the most important vegetable wax in economic terms and in terms of possible applications [15], many researchers are still looking for new applications for this raw material, seeking new products and new technologies, or trying to improve existing ones [14]. Thus, in recent years, the increase in the number of studies involving carnauba has mainly been due to studies directed at its wax in terms of its production, storage, and applications in food processing [14].

Figure 2.

Number of articles published in the Web of Science database using the keywords “copernicia” and “carnauba”, from 2007 to 2022.

The ten most cited publications are presented in Table 3. Overall, the most relevant publications on carnauba involve the chemical and physical properties of its wax. The first most cited article, “Food applications of emulsion-based edible films and coatings” [16], accounts for 309 citations. This review discussed the potential food applications of emulsified edible films and coatings. Materials such as natural carnauba wax, preparation methods, and physical properties are also presented. Carnauba wax has a high melting point, hardness, water insolubility, and stability and is widely used in foods as a food additive, performing various functions, according to specific legislation in different countries. The Codex Alimentarius allows for the use of carnauba wax [17] as a food additive with the functions of glazing agent, body or dough agent, acidity regulator, anti-caking agent, and carrier [18].

Table 3.

The 10 most important publications selected from the Web of Science database using the keywords “copernicia” and “carnauba”, from 2007 to 2022.

The second most cited work, “Total phenolics and antioxidant activity of five medicinal plants” [19], is a Brazilian article that describes the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity in the ethanolic extract of the leaves, bark, and roots of five different medicinal plants, including C. prunifera, which is popularly used as an elixir in the treatment of syphilis and skin infections. However, the results obtained in this work showed that, compared to other analyzed plants, the extract obtained from carnauba roots had the lowest percentage of antioxidant activity and is not recommended for further studies regarding its potential to protect against the risks of pathological processes. The third most cited article, “Structure and physical properties of plant wax crystal networks and their relationship to oil binding capacity,” evaluates the melting and crystallization behavior, rheological properties, and oil-binding capacity of plant-derived wax crystal networks in edible oil [20]. Developing functionally viable alternatives to fats rich in saturated and trans fatty acids is challenging, but vegetable waxes, including carnauba wax, have shown great potential in creating fat-like materials. Vegetable waxes form liquid oils at very low concentrations, which become edible oil organogels, also known as oleogels. Furthermore, these waxes are readily available and safe for consumption, making them an economically viable oil-structuring agent [20].

In the article “Physical properties of rice bran wax in bulk and organogels”, the fourth most cited, the authors used differential scanning calorimetry, optical microscopy, and X-ray diffraction to evaluate the thermal behavior, structure, and crystalline morphology of rice bran wax in bulk and oil–wax mixtures and to compare them with those of carnauba wax and candelilla wax [21]. In fifth place in Table 3, the article “Preparation and characterization of ketoprofen-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles made from beeswax and carnauba wax” explores the use of carnauba wax and beeswax as components of solid lipid nanoparticles, which are used as colloidal carriers suitable for the administration of drugs with limited solubility [22]. In the sixth most cited work, “Evaluation of edible films and coatings formulated with cassava starch, glycerol, carnauba wax and stearic acid”, the researchers evaluated a series of chemical and physical characteristics of four formulations of edible coatings/films based on cassava starch, glycerol, carnauba wax, and stearic acid [23]. In the article “Fabrication of superhydrophobic paper surface via wax mixture coating”, ranked seventh, the researchers built microstructures using natural waxes to prepare the surface of superhydrophobic paper as an alternative to fluoride-based ones [24]. Reinforcing the theme of carnauba and the food industry, the work “Stability, solubility, mechanical and barrier properties of cassava starch—Carnauba wax edible coatings to preserve fresh-cut apples”, in eighth position (Table 3), evaluates edible coatings/films formulated with cassava starch, glycerol, carnauba wax, and stearic acid regarding the stability of the emulsion and the barrier properties when these coatings are applied to minimally processed apples [25].

In the penultimate position, the publication “Rhodamine B removal with activated carbons obtained from lignocellulosic waste” explores the use of activated carbons obtained from three little-explored lignocellulosic waste materials (from Copernicia prunifera, Acrocomia aculeata, and Pinus pinea) for the adsorption of contaminants in wastewater, taking Rhodamine-B (RhB) as an example [26]. In the tenth most cited article, “Evaluating the Oil-Gelling Properties of Natural Waxes in Rice Bran Oil: Rheological, Thermal, and Microstructural Study”, the authors conducted tests to evaluate natural waxes for their oil-gelling properties using various techniques such as rheology, differential scanning calorimetry, and polarized light microscopy [27]. According to [14], carnauba wax is a product with potential for use throughout the food production chain and can be used as a coating agent, bulking agent, acidity regulator, vehicle, and anti-caking agent in surface treatment, among other things. Several scientific studies have been conducted in recent years with the objective of increasing the possibilities of applications of this raw material, investigating innovations such as the use of this wax for microencapsulation of aromas and as a source of molecules that act in the prevention and treatment of dyslipidemias, diabetes, and other diseases [14]. Together, the most cited studies demonstrate that technological applications of carnauba wax, especially in edible coatings, encapsulation, and biomaterials, were the main drivers of scientific impact in this field.

Many researchers are focused on analyzing the seed germination, growth, and development of C. prunifera plants. Most palm trees have seeds that germinate slowly and irregularly, with a degree of dormancy that can vary between species [28]. Therefore, several studies have been carried out with the aim of overcoming seed dormancy in these plants by testing different techniques such as pre-germinative treatments, removal and scarification of the endocarp, use of gibberellic acid, and immersion of seeds in water [29]. For carnauba seeds, immersion in water is recommended until the protrusion of the cotyledonary petiole [30], which can vary from 13 to 32 days, depending on the imbibition temperature [31].

On the other hand, different initiatives have focused their research on carnauba wax on the encapsulation of various types of vegetable oils. For example, carnauba wax can be used as a binding agent in industrial metallurgical powder injection molding systems. Also, some studies have analyzed carnauba wax in the area of food technology—using this wax to structure various vegetable oils to develop solid oleogels, which in turn can be alternatives to deep-frying—mainly the potential of carnauba wax in the preservation of post-harvest vegetables, but this time exploring emulsion and nanoemulsion formulations. According to [32], the use of edible and active films and coatings is currently gaining popularity due to their efficiency in increasing the post-harvest shelf life of fruits and vegetables. Carnauba wax is part of the group of lipid food coatings and has been widely used to increase the shelf life of fruits and vegetables, acting to reduce water loss and maintain a shiny appearance [33].

In Brazil, studies involving this palm tree are quite relevant in semi-arid regions. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [34], Piauí was the Brazilian state with the largest production of carnauba wax powder, with around 10 thousand tons produced, followed by Ceará, which produced more than 7 thousand tons. Together, these states are responsible for 96% of national production.

Table 4 shows the 10 countries that stand out in the field of carnauba research. Brazil is the country with the greatest impact in the area (235 publications and 2575 citations), followed by the United States and China, which are in second and third place with 1347 and 813 citations, respectively.

Table 4.

Top 10 most important countries selected from the Web of Science database using the keywords “copernicia” and “carnauba”, from 2007 to 2022.

The United States is the largest importer of carnauba wax, and there, this material is classified as GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe), being permitted in various foods, without quantity limitations, as long as good manufacturing practices are followed. In this country, the wax is authorized as an anti-caking agent, formulation aid, lubricant, release agent, surface finishing agent in baked goods and bakery mixes, chewing gum, toppings, fresh fruits and fruit juices, sauces, processed fruits, and soft candies [14,18]. Therefore, Americans, as they are significant consumers of this carnauba derivative, also demonstrate great interest in developing research on the subject.

Like the US, China is also a leader in the carnauba wax trade. According to the Federation of Industries of the State of Ceará [35], in 2019, this country saw the highest growth in imports of wax of Brazilian origin, with an increase of almost 195% compared to the previous period. Carnauba wax has a variety of uses, so numerous studies on the subject have been carried out in this country.

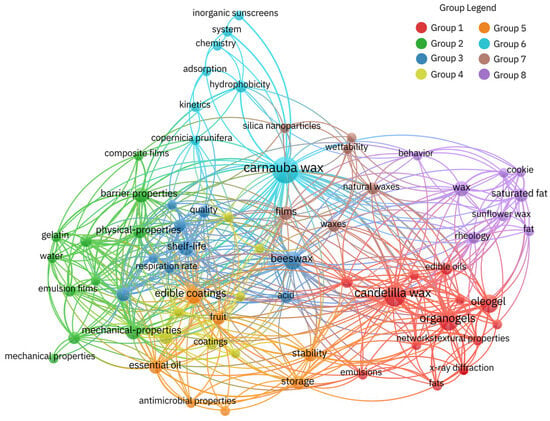

The VOSviewer program analyzes the input file, generates the network map, and finally provides map visualization and exploration functions. In turn, the visualization map shows the keywords or terms in the data file based on the clustering techniques available in VOSViewer [36]. To explore the current topics and possible future topics on carnauba, a keyword co-occurrence analysis was performed using VOSviewer, from which eight groups represented by eight different colors were formed (Figure 3). The colors represent groups of terms that have a stronger relationship with each other [37].

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence network of keywords for the research field “carnauba” and “copernicia”, from 2007 to 2022.

Group 1, in red, is composed of 13 words and the most representative ones, which point out the most important subjects within the group, include “candelilla wax”, “organogels”, “oleogel”, and “edible oils”. Importantly, this cluster accounted for ~20% of all co-occurring terms, confirming the dominance of wax-related technological research. Some studies study and compare the physical properties of different waxes and oils of vegetable origin, such as carnauba and candelilla, so it is not very rare to find research involving these two plants (Figure 3). Unlike carnauba, candelilla (Euphorbia antisyphilitica Zucc) is a plant of the genus Euphorbia, native to the southcentral United States and Mexico. However, it also grows in stressful environments, occurring in semi-desert regions, mainly on slopes with limestone soil or slopes associated with rocky material formations.

According to [38], candelilla and carnauba waxes form stable and consistent organogels and can be applied in the preparation of margarines, sorbents, cream cheeses, butters, confectionery fillings, and cookies.

Group 2, in green, is composed of nine words, the most representative of which are “barrier properties” and “physical properties”. In this group, the research topics focus on the use of biofilms from carnauba. In group 3 (dark blue), the words “beewax” and “shelf-life” stand out, referring to studies involving different types of waxes in the development of technologies and products that increase the shelf life of various products (Figure 3). The wax derived from this palm tree has the greatest hardness and the highest melting point among all commercial natural waxes, has low solubility, and is composed mainly of aliphatic esters and cinnamic acid diesters, which gives it a certain stability [14]. However, despite having good properties, carnauba wax is not commonly used for manufacturing films due to its low mechanical strength and is, therefore, often used in the manufacturing of composite films with other biopolymers [32].

Groups 4 and 5, in yellow and orange, respectively, appear closely linked in the network, meaning that the relationships between their keywords are more intense (Figure 3). Thus, the main words in these groups, such as “edible coatings”, “antioxidant activity”, and “packaging materials”, are related to studies that study carnauba by-products in the composition of materials for packaging and edible coatings that extend the post-harvest life of fruits. Several studies have already elucidated the efficiency of carnauba wax in increasing the shelf life and maintaining the post-harvest quality of several fruits, such as lemon [39], papaya [40], tomato [41], and orange [42], among others.

The highlight of group 6 (light blue) is the keyword “carnauba wax”, which establishes a connection with all groups in the network, demonstrating that the main focus of studies on carnauba is the use and chemical characterization of its wax (Figure 3). In addition, certain characteristics of the wax, such as its hydrophobicity, are widely explored in research. According to [43], the distance between two terms provides an approximate indication of the relationship between the terms. Thus, the greater the number of publications in which two terms were found, the closer and more strongly related the terms are.

The term “carnauba wax” is also closely linked to group 7 (in brown), which highlights the words “waxes”, “natural waxes”, “films”, and “superhydrophobic”. In group 8, in lilac, we have the words “wax”, “saturated fat”, and “rheology” highlighted. Rheology is the branch of physics that studies the deformation and flow of materials, essential in quality control and verification of the shelf life of products (Figure 3). In brief, smaller clusters correspond to edible films and coatings (~16%), physicochemical and barrier properties (~13%), fat/oil structuring (~12%), chemistry and surface properties (~12%), antimicrobial/antioxidant functions (~10%), controlled release and nanostructures (~10%), and hydrophobic/superhydrophobic functional surfaces (~9%). These proportions demonstrate that, while wax-based technological applications prevail, ecological, agronomic, and conservation-related topics remain fragmented or absent from the clusters.

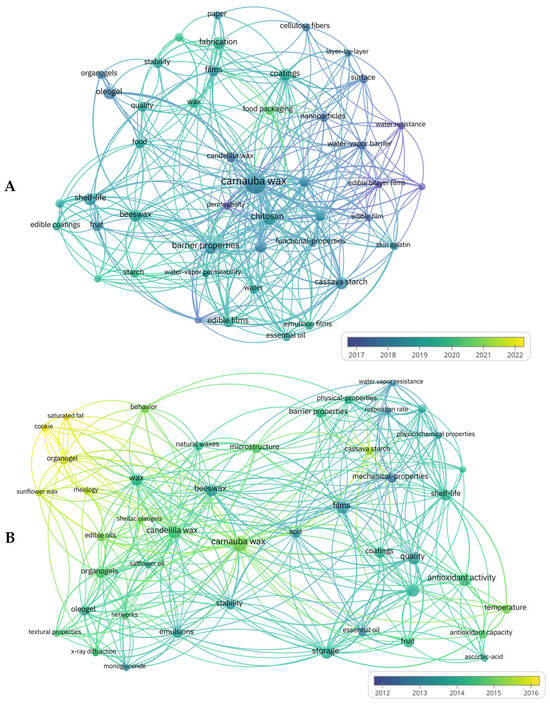

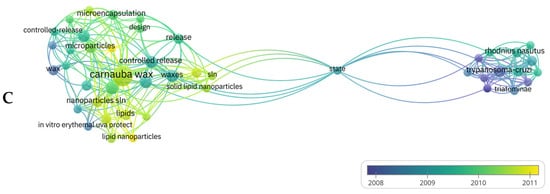

To analyze the variations in the most studied points about carnauba, the keywords were distributed by period during the years analyzed. Thus, we have three periods: from 2007 to 2011, from 2012 to 2016, and from 2017 to 2022. (Figure 4). In the first period, from 2007 to 2011, the focal themes were carnauba wax, chemical and physical properties of the wax, and carnauba trees as a shelter for insects that carry serious infections (Figure 4A). From 2012 to 2016 (Figure 4B), themes related to carnauba wax and its physical and chemical characteristics remained prominent throughout most of the period. Only in mid-2015 and 2016 did studies related to the use of carnauba wax as an ingredient in processed foods become prominent. From 2017 to 2022, the theme of studies involving carnauba remains centered on the wax and its various applications, revealing that this will be the trend for future studies on this plant (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Co-occurrence network of keywords for the research field “carnauba” and “copernicia” in four different periods. (A) 2007 to 2011. (B) 2012 to 2016. (C) 2017 to 2022.

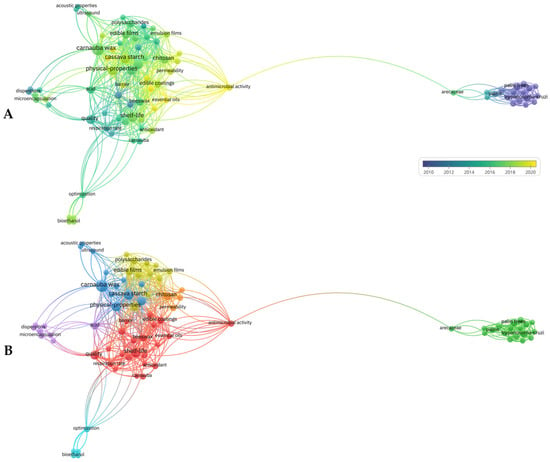

As seen previously, Brazil stands out in the production of works on carnauba (Table 4). Therefore, in order to analyze which are the main points addressed by Brazilian researchers, a co-occurrence analysis of keywords was carried out using VOSviewer, only with research from this country from 2007 to 2022 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(A) Co-occurrence network of keywords for the research field “carnauba” and “copernicia” of Brazilian works from 2007 to 2022. (B) Keyword co-occurrence network for the research field “carnaúba” and “copernicia” of Brazilian works, divided by periods from 2007 to 2022.

In Brazil, research is also mainly related to points about carnauba wax, which is evidenced by the fact that six of the seven groups formed in the network are closely linked to the term “carnauba wax”. The most peripheral group of words (in green) includes works related to botanical aspects of carnauba and also works on the life cycle of disease vectors that shelter in palm trees, such as the kissing bug, which transmits the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, which causes Chagas disease (Figure 5A).

In rural areas of northeastern Brazil, the construction of homes near carnauba palms is a very relevant factor in the process of intra-household infestation of bedbugs, which are vectors of Chagas disease, such as R. nasutus. In addition, the trunk of the carnauba palm is often used in the construction of roofs, an action that promotes the passive transport of this insect from its habitat to homes [44].

Analyzing the same word network over the period from 2007 to 2022 (Figure 5B), we can see that in recent years, the trend of Brazilian studies on carnauba has also focused on the properties and uses of its wax. Studies on C. prunifera and its environmental importance are still little explored in the country.

Although carnauba is a highly relevant plant in several environmental aspects, the number of studies involving this palm tree and soil sciences is still incipient: only 33 studies were obtained on this topic. Soil cover from plant residues contributes to carbon (C) sequestration in the soil, providing organic matter and increasing the concentration of organic C in the soil, improving soil fertility and structure [45].

The article “Effect of different tannery sludge compost amendment rates on growth, biomass accumulation and yield responses of Capsicum plants” investigated the potential effect of tannery sludge composted with cattle manure and carnauba straw on the ornamental growth of Capsicum. The research revealed that the combination of tannery sludge compost increased the different chemical parameters of the soil and the nutrient contents in the soil. This greater availability of essential nutrients led to significant increases in biomass accumulation, chlorophyll content, and yield in Capsicum grown under compost [46].

Seeking to develop sustainable packaging, the article “All-Natural Sustainable Packaging Materials Inspired by Plant Cuticles” observed that the addition of carnauba wax to the polyaleuritate matrix (a material of biological origin) resulted in improved water and oxygen barrier properties [47]. The third most cited article, “Effect of cover plants on soil C and N dynamics in different soil management systems in dwarf cashew culture”, evaluated the changes in soil C and N dynamics caused by different cover plant management systems (including carnauba mulch) in dwarf cashew crops in northeastern Brazil [48]. In this work, the authors highlighted the environmental benefits that soil cover management with plant remains provides to cashew crops. While contributing to the cycling of organic matter and nutrients in the soil, they also promote the maintenance of soil moisture and temperature, configuring themselves as a good strategy for dealing with water stress in the Brazilian northeast, a common occurrence that contributes to low productivity levels in this region [48].

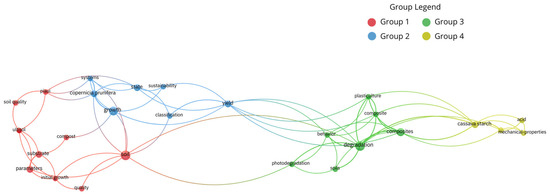

Keywords in the literature on carnauba and soil research were analyzed using the VOSviewer tool. In this analysis, the minimum number of occurrences of a keyword in titles, abstracts, and keywords was set at three. The results identified “soil”, “degradation”, and “growth” as the most common keywords (Figure 6). A total of 27 keywords were identified and classified into four groups. Group 1 (red) has “soil” as the main word and concentrates the works on the use of carnauba straw in soil cover. Group 2 (blue) highlights the word “growth” and presents studies on the use of carnauba plant residues for the development of sustainable cultivation systems.

Figure 6.

Co-occurrence network of keywords for the research field “carnauba”, “copernicia”, and “soil” between 2007 and 2022.

Gonçalves et al. conducted experimental trials to evaluate the effectiveness of carnauba bagana mulch in the establishment of 32 Caatinga plant species. The use of this mulch improved the growth or survival of eight evaluated species (Pseudobombax marginatum, Peltophorum dubium, Anadenanthera colubrina, Bauhinia cheilantha, Copernicia prunifera, Hymenaea courbaril, Mimosa caesalpiniifolia, and Senna spectabilis), demonstrating that carnauba-based mulch can be used in species that respond positively, with the aim of improving establishment and growth in degraded areas of the region [49].

Groups 3 and 4 (green and yellow, respectively) show studies on the use of wax in plastic mulching coatings in agriculture. Most plastic mulch films used in agriculture are composed of low-density polyethylene, which is considered unsuitable for sustainable agricultural management. These plastic films have limited and undesirable disposal options, and their residual plastic fragments can cause damage when discarded and accumulated in the soil, causing negative effects such as the release of toxic substances and fragmentation into microplastics [50]. Some more environmentally friendly alternatives have been explored, such as the development of coating films reinforced with natural coatings, which are low-cost, biodegradable, low-abrasive for thermoplastic processing equipment, and non-toxic. Among the materials that can be used for this type of coating is carnauba wax [50].

Oliveira et al. evaluated the performance of mulch films composed of biodegradable polymer (polyn (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)) (PBAT), sugarcane, and carnauba wax during soil application for 60 days under real-world conditions. The results showed that in high-temperature environments, PBAT mulch films containing carnauba wax are the best option [51].

Importantly, the co-citation analysis revealed three research fronts. The largest cluster grouped wax, edible coatings, and oleogel-related studies (38% of connections). Brazil was the main institutional hub, followed by the United States. Thus, as mentioned, the predominance of wax-based research suggests a strong industrial and technological focus. Conversely, ecological and conservation studies remain fragmented, indicating an opportunity for future multidisciplinary work.

When it comes to work involving carnauba and soil sciences, it is clear that this plant is only a supporting theme; the situation is even worse when it comes to research on carnauba and associated microbiomes. The microorganisms that colonize the internal and external tissues of plants, combined with the diversity of microorganisms in the soil rhizosphere, make up the plant microbiome, which is closely related to plant health, acting as a reservoir of additional genes that plants can access when necessary, such as in the face of biotic and abiotic stresses. Understanding the regulation of the expression of plant traits, and, therefore, plant performance, and how this directly affects ecosystem function, brings the need for research on the impacts of the microbiome associated with plants [52].

In heterogeneous environments, complex interactions between the plant’s immune system and its associated microbiome increase the plant’s abilities and flexibility in dealing with adversities [53]. Carnauba grows in places with high temperatures and periodically flooded soils, often with high salt concentrations. The role of the associated microbiome in the performance of carnauba in these environments has not yet been elucidated. Therefore, efficient and appropriate study methods are needed to identify the communities of microorganisms and their functionalities in the carnauba–microbiome–environment system.

Bioprospecting of microorganisms associated with plants in stressful environments can also be a potential source of inocula for the development of biotechnological products. This approach is mainly focused on isolation, colonization capacity, the type of formulation, and understanding the interaction mechanisms of growth-promoting bacteria under stress conditions, which can be used as bioinoculants [54].

Despite the vast economic and ecological importance of carnauba, there are no records in the main international bibliographic databases of studies exploring the microorganisms associated with these plants, making carnauba palms a rich hotspot of microbial biodiversity still unexplored by academia, with microbial groups, genes, and biotechnological processes that may have high potential for use in biotechnologies applicable to crop plants. The predominance of wax-related research reveals a strong industrial and technological bias in carnauba studies, while ecologically strategic themes, such as population genetics, plant–soil interactions, carbon sequestration, and microbiome-assisted stress tolerance, form small or isolated clusters. Thus, the bibliometric structure not only shows research volume but also exposes a scientific gap: Copernicia prunifera is ecologically important, yet ecologically understudied.

4. Conclusions

This study provides the first comprehensive bibliometric mapping of scientific research involving Copernicia prunifera. By analyzing 658 publications over the past 15 years, the study identified the countries, institutions, and authors leading research on the species, as well as the thematic evolution and dominant research trends. The most recurrent and influential studies have focused on the technological applications of carnauba wax, particularly in food science, coatings, and biomaterials, while research integrating carnauba with soil science, ecology, and plant–microbiome interactions remains scarce. These findings advance the scientific body of knowledge by revealing not only what is known but also the thematic gaps that remain unexplored. Thus, the main conclusions of the study are as follows:

- The number of published articles on carnauba showed significant growth from 2014 onward, reaching its peak between 2019 and 2021.

- Bibliometric analyses of publications, journals, and authors show that research related to the physical and chemical properties of carnauba wax is the most explored topic in the most relevant works.

- Brazil stands out in publications on carnauba, followed by the United States.

- Co-occurrence networks of keywords show that carnauba wax is the most explored and most relevant topic when it comes to studies involving this palm tree.

- Research relating to carnauba and soil sciences is still little explored, which may reveal an excellent topic for future research.

In summary, the bibliometric evidence indicates that research on Copernicia prunifera remains strongly concentrated on wax-related applications, while ecological, agronomic, and conservation-focused studies are still incipient. By uncovering these asymmetries, this work not only consolidates existing knowledge but also points to strategic research opportunities, particularly in plant–soil–microbiome interactions and sustainable management of native carnauba landscapes. As with any bibliometric study, the analysis depends on metadata and the chosen database (Web of Science), meaning that non-indexed or regionally distributed publications may not be captured. Thus, we expect that these insights will support decision-makers, researchers, and funding agencies in expanding the scientific agenda toward the ecological and socio-environmental dimensions of this emblematic palm species. Finally, research opportunities include exploring carnauba–soil interactions, microbiome ecology, and conservation genetics, areas currently underrepresented in the literature.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments12110437/s1, Figure S1. PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the selection process of studies included in the review. The diagram summarizes the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion stages of the systematic review following the PRISMA 2020 framework.

Author Contributions

Data curation, E.B.d.S.; investigation, E.B.d.S. and F.M.M.d.F.; writing—original draft, E.B.d.S. and F.M.M.d.F.; conceptualization, A.P.d.A.P.; supervision, writing—review and editing, A.P.d.A.P., A.J.d.S. and V.N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank FUNCAP (grant nº UNI-00210-00504.01.00/23, FUNCAP UNIVERSAL Call -Nº 06/2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Rodrigues, L.C.; Silva, A.A.D.; Silva, R.B.D.; Oliveira, A.F.M.D.; Andrade, L.D.H.C. Conhecimento e uso da carnaúba e da algaroba em comunidades do Sertão do Rio Grande do Norte, Nordeste do Brasil. Rev. Árvore 2013, 37, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.N.F.; Gomes, J.M.A. Pobreza, emprego e renda na economia da carnaúba. Rev. Econômica Do Nordeste 2009, 40, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Produção da Extração Vegetal e da Silvicultura 2021; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2021. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/74/pevs_2021_v36_informativo.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Silva, C.M.; Souza, R.; Cunha, L.; Val, A.; Mendes, M.R. Aspectos da fenologia de Copernicia prunifera (Mill.) HE Moore no litoral do Piauí, Brasil. Enciclopédia Biosf. 2019, 16, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Paula, E.A.; Costa, C.Y.M.; Silva, L.E.S.; Souza, F.M.; Melo, R.R. Propriedades mecânicas do talo de carnaúba (Copernicia prunifera) obtidas através de ensaios de tração. Agropecuária Científica No Semiárido 2020, 16, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda, S.J.; Araújo, F.S.D.; Gallão, M.I.; Medeiros Filho, S. Impacto da salinidade no desenvolvimento e crescimento de mudas de carnaúba (Copernicia prunifera (Miller) HE Moore). Rev. Bras. De Eng. Agrícola E Ambient. 2011, 15, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Liu, H.; Xue, Y. A bibliometric and visualized analysis of the global literature on black soil conservation from 1983–2022 based on CiteSpace and VOSviewer. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parron, L.M.; Fidalgo, E.C.C.; Luz, A.P.; Campanha, M.M.; Turetta, A.P.D.; Pedreira, B.C.C.G.; Prado, R.B. Research on ecosystem services in Brazil: A systematic review. Rev. Ambiente Água 2019, 14, e2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, L.; Costa, C.; Pallottino, F.; Mocali, S. Trends in soil microbial inoculants research: A science mapping approach to unravel strengths and weaknesses of their application. Agriculture 2021, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.Y.V.; Cherubin, M.R.; Greschuk, L.T.; Muniz, G.D.A.M.; Cavalcante, D.M.; Pereira, A.P.A. Mapping soil health research in the Brazilian Semiarid region: A bibliometric approach. Exp. Agric. 2024, 60, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Yang, Z. Knowledge mapping of platform research: A visual analysis using VOSviewer and CiteSpace. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 22, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.A.S.; Sousa, P.H.M.; Soares, D.J.; Silva, J.Y.G.; Benjamin, S.R.; Guedes, M.I.F. Carnauba wax uses in food–A review. Food Chem. 2019, 291, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojaković, D.; Bugarski, B.; Rajić, N. A kinetic study of the release of vanillin encapsulated in Carnauba wax microcapsules. J. Food Eng. 2012, 109, 640–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galus, S.; Kadzińska, J. Food applications of emulsion-based edible films and coatings. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Codex Alimentarius: General Standard for Food Additives; INS 903; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1995; pp. 124–478. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B192-1995%252FCXS_192e.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, Chapter II—Definitions, Section 321. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21; U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2021-title21/html/USCODE-2021-title21-chap9-subchapII-sec321.htm (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Sousa, C.M.M.; Silva, H.R.; Ayres, M.C.C.; Costa, C.L.S.; Araújo, D.S.; Cavalcante, L.C.D.; Barros, E.D.S.; Araújo, P.B.M.; Brandão, M.S.; Chaves, M.H. Total phenolics and antioxidant activity of five medicinal plants. Química Nova 2007, 30, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, A.I.; Co, E.D.; Marangoni, A.G. Structure and physical properties of plant wax crystal networks and their relationship to oil binding capacity. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 885–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassanayake, L.S.K.; Kodali, D.R.; Ueno, S.; Sato, K. Physical properties of rice bran wax in bulk and organogels. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheradmandnia, S.; Vasheghani-Farahani, E.; Nosrati, M.; Atyabi, F. Preparation and characterization of ketoprofen-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles made from beeswax and carnauba wax. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2010, 6, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumarelli, M.; Hubinger, M.D. Evaluation of edible films and coatings formulated with cassava starch, glycerol, carnauba wax and stearic acid. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 38, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, P.; Qian, L.; Xiao, H. Fabrication of superhydrophobic paper surface via wax mixture coating. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 250, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumarelli, M.; Hubinger, M.D. Stability, solubility, mechanical and barrier properties of cassava starch–Carnauba wax edible coatings to preserve fresh-cut apples. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 28, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, V.S.; López-Sotelo, J.B.; Correa-Guimarães, A.; Hernández-Navarro, S.; Sánchez-Báscones, M.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Martín-Gil, J. Rhodamine B removal with activated carbons obtained from lignocellulosic waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 155, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, C.D.; Van de Walle, D.; Dewettinck, K.; Patel, A.R. Evaluating the oil-gelling properties of natural waxes in rice bran oil: Rheological, thermal, and microstructural study. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2015, 92, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, K.B.; Souza, A.M.B.D.; Muniz, A.C.C.; Pivetta, K.F.L. Germinação de sementes de palmeiras sob períodos de reidratação. Ornam. Hortic. 2021, 27, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, R.D.O.; Meireles, V.M.; Sena, W.D.L.; Costa, B.O.D.; Camargo, R.N.C.; Pivetta, K.F.L. Methods for overcoming seed dormancy in blue palm. Ornam. Hortic. 2024, 30, e242702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.D.B.; Medeiros Filho, S.; Bezerra, A.M.E.; Freitas, J.B.S.; Assunção, M.V. Pré-embebição e profundidade de semeadura na emergência de Copernicia prunifera (Miller) H. E Moore. Rev. Ciência Agronômica 2009, 40, 272–278. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283400377 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Reis, R.G.E.; Bezerra, A.M.E.; Gonçalves, N.R.; Pereira, M.D.S.; Freitas, J.B.S. Biometria e efeito da temperatura e tamanho das sementes na protrusão do pecíolo cotiledonar de carnaúba. Rev. Ciência Agronômica 2010, 41, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.S.; Kalita, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Kumar, S. Carnauba wax-based composite films and coatings: Recent advancement in prolonging postharvest shelf-life of fruits and vegetables. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 129, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhir, S.S.S.; Priti Khemariya, P.K.; Ashutosh Rai, A.R.; Rai, A.C.; Koley, T.K.; Bijendra Singh, B.S. Carnauba wax-based edible coating enhances shelf-life and retain quality of eggplant (Solanum melongena) fruits. LWT 2016, 74, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Produção da Extração Vegetal e da Silvicultura 2023; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/9105-producao-da-extracao-vegetal-e-da-silvicultura.html (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Federation of Industries of the State of Ceará—FIEC. Setorial em Comex Cera de Carnaúba Edição Maio. 2019. Centro Internacional de Negócios, Fortaleza–Ceará. Available online: https://arquivos.sfiec.org.br/sfiec/files/files/05%20MAI%202019%20-%20Cera%20de%20Carnauba.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Bukar, U.A.; Sayeed, M.S.; Razak, S.F.A.; Yogarayan, S.; Amodu, O.A.; Mahmood, R.A.R. A method for analyzing text using VOSviewer. MethodsX 2023, 11, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forezi, L.S.M.; Hüther, C.M.; Ferreira, P.G.; Portella, D.P.; Gonzaga, D.T.G.; Silva, F.D.C.; Ferreira, V.F. Aqui tem Química: Parte V: Ceras Naturais. Rev. Virtual De Química 2022, 14, 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Follett, P.; Shu, C.; Yusufali, Z.; Bai, J.; Wall, M. Effect of X-ray Irradiation and Carnauba Wax Coating on Quality of Lime (Citrus latifolia Tan.) Fruit. HortScience 2024, 59, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Silva, G.C.; Oldoni, F.C.A.; Miranda, M.; Florencio, C.; Oliveira, R.M.D.D.; Gomes, M.P.; Ferreira, M.D. Edible coating based on carnauba wax nanoemulsion and Cymbopogon martinii essential oil on papaya postharvest preservation. Coatings 2022, 12, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Mori, M.R.; Spricigo, P.C.; Pilon, L.; Mitsuyuki, M.C.; Correa, D.S.; Ferreira, M.D. Carnauba wax nanoemulsion applied as an edible coating on fresh tomato for postharvest quality evaluation. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, E.; Nasiri, J.; Malidarreh, T.R.; Kalantari, S.; Naghavi, M.R.; Safari, M. Performance of carnauba wax-nanoclay emulsion coatings on postharvest quality of ‘Valencia’ orange fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.C.P. Epidemiologia. In Trypanosoma cruzi e Doença de Chagas, 2nd ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2000; pp. 48–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Heiling, M.; Resch, C.; Mbaye, M.; Gruber, R.; Dercon, G. Does maize and legume crop residue mulch matter in soil organic carbon sequestration? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.D.; Leal, T.T.; Araújo, A.S.; Araujo, R.M.; Gomes, R.L.; Melo, W.J.; Singh, R.P. Effect of different tannery sludge compost amendment rates on growth, biomass accumulation and yield responses of Capsicum plants. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1976–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Benítez, J.J.; Cataldi, P.; Paul, U.C.; Contardi, M.; Cingolani, R.; Bayer, I.S.; Heredia, A.; Athanassiou, A. All-natural sustainable packaging materials inspired by plant cuticles. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2017, 1, 1600024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, F.A.D.S.; Maia, S.M.F.; Ribeiro, K.A.; Mendonça, E.S.; Oliveira, T.S. Effect of cover plants on soil C and N dynamics in different soil management systems in dwarf cashew culture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 165, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.; Aximoff, I.; Resende, A.S.D.; Chaer, G.M. Effect of Carnaúba Bagana Mulching on Tree Species Planted in Degraded Areas in Caatinga. Floresta E Ambiente 2023, 30, e20220091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.A.; Oliveira, I.M.; Mousinho, F.E.P.; Barbosa, R.; Carvalho, L.H.; Alves, T.S. Biodegradation of mulch films from poly (butylene adipate co-terephthalate), carnauba wax, and sugarcane residue. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 48240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.A.D.; Mousinho, F.E.P.; Barbosa, R.; Carvalho, L.H.D.; Alves, T.S. Mulch films based on poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/carnauba wax/sugar cane residue: Effects on soil temperature and moisture. J. Compos. Mater. 2021, 55, 3175–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, M.E. The plant microbiome. In Advances in Botanical Research; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.P.; Colaianni, N.R.; Fitzpatrick, C.R.; Dangl, J.L. Beyond pathogens: Microbiota interactions with the plant immune system. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 49, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, M.; Wani, S.P. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria: Drought stress alleviators to ameliorate crop production in drylands. Ann. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).