Abstract

Urbanisation has resulted in habitat degradation and destruction for native bat species in Florida, USA, posing a continuing threat to bat populations and ecosystem health. Citizen science has been documented to fill population data gaps and outline bat responses to urbanisation, but an understanding of how this influences societal perceptions of bats and can shape and evolve urban planning initiatives are under-researched and poorly understood. This paper explores how citizen science could contribute to urban planning for bat conservation. A literature review of citizen science projects and native species’ responses to urbanisation mapped the current situation and was supplemented by an analysis of semi-structured interviews with three key informants in the field of bat conservation. Only four of Florida’s thirteen species were featured in the citizen science projects reported in the literature. There was a clear lack of attention to the impact of urbanisation on these species, demonstrating a need for reimagining how data collection and public participation can be improved. An analysis of interviews identified themes of evolving individual perspectives and complex societal connections whose interdependence and coevolution influences the success of both citizen science and urban planning. Understanding this coevolution of society and bat conservation alongside our current knowledge could provide future opportunities for bat-friendly urban planning in Florida with the potential for this to be framed in terms of healthy more-than-human cities.

1. Introduction

There are currently over 1300 species of bats worldwide registered with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), making up over twenty percent of mammalian species and providing crucial ecosystem services [1,2,3]. Despite this, almost twenty percent of the order is classified as data deficient worldwide with many others lacking accurate population counts [2]. Florida hosts thirteen species of native bats, including the endemic species E. floridanus; over half have no known population trend or estimate and are data deficient (Table 1). The state is projected to have a forty percent increase in the human population, with 36 million residents by 2070, accompanied by an anticipated loss of seven million acres of rural and natural areas due to urbanisation [4,5]. This level of population growth and urbanisation, coupled with the lack of data on native bats, is concerning. Failure to recognise and address this could result in unknown effects on bat populations and a loss of valuable ecosystem services that passes unrecognised until population numbers become critically low.

Table 1.

Scientific names and common names of the thirteen native bats in Florida, USA, and their current population estimates and population trends.

While challenges with data collection for this order have been attributed to their small size, nocturnal nature, need for advanced technology to hear calls, and negative public perceptions [8,9], improvements in technology along with reimagining how society and this order co-influence each other can help outline a path forward to improving current knowledge and conservation of bat populations. This could allow bat-friendly urban planning policies to emerge and develop. Data collection utilising citizen science has been shown to allow earlier detection of red-level alert declines, identification of important habitats, increased data collection speed, and improved public knowledge and understanding of conservation issues that can in turn influence policy and legislative change [10,11,12] in relation to urban planning. The Florida Bat Working Group (FBWG) is the only easily identifiable organisation in Florida providing an accessible means for members of the public to participate in citizen science through roost and emergence counts [13]. A better understanding of citizen science initiatives and how they interface with urban planning could help such organisations contribute to the emerging narrative surrounding bat-friendly urban planning. Florida’s lack of accessible citizen science opportunities, coupled with the threat of rampant urbanisation and the absence of published studies on native bat responses to such developments, make this a meaningful case study, representative of the challenges in urban planning for healthy more-than-human cities nationally and internationally.

This paper recognises the need to develop bat-friendly urban planning by enhancing the contribution made by citizen science to the development of a shared understanding of the effects of urbanisation and by further engaging communities in integrating bat conservation into urban planning policy and practice. This collaborative approach is fundamentally transdisciplinary and recognises the interdependence of environmental, human, and more-than-human health (please note that the more inclusive and equitable term “more-than-human” is used to encompass other-than-human animals, plants, and fungi) and thus aligns with the One Health approach [14].

We set out to better understand how this collaborative approach could influence bat conservation and outline a path forward by means of a literature review on how citizen science is currently being utilised to study bats and how they are impacted by urbanisation. This was supplemented by three semi-structured key informant interviews to explore the potential for citizen engagement and the integration of citizen contributions into a transdisciplinary, multi-stakeholder approach to urban planning. The underlying aim of this project was thus to explore how citizen science and engagement can contribute to a shift towards bat-friendly, nature-positive urban planning, informed by One Health principles.

2. Materials and Methods

To better conserve bats and preserve ecosystem health during an era of intense urbanisation in Florida, it is essential that we have a good understanding of their responses to urbanisation and the role that citizen science can play in both developing understanding and evolving sustainable ecological relationships. This section presents the approach taken to the literature review and to the key informant interviews.

2.1. Literature Review

A scoping literature review of citizen science projects involving members of the order Chiroptera native to Florida and their responses to urbanisation was performed by searching relevant key word combinations including Chiroptera, bats, and native species names together with citizen science, citizen led/citizen-led, volunteer, urban planning, and urbanisation in Science Direct and Web of Science databases between the years 2003 and 2024. Boolean operators AND QUOTATION MARKS were utilised to focus results [15]. Database searches were performed during the months of December 2023 and January 2024. The articles were then reviewed and included in this study if all the following criteria were met: focus on a member of Chiroptera, abstract or full paper available in English—only parts of the paper in English were reviewed—discussion of urban planning features, urbanisation effects, or citizen science. A pragmatic decision to exclude the literature focussed on zoonotic diseases was made due to the large volume of literature and focus surrounding this subject, especially after the emergence of COVID-19, which further contributed to negative public perceptions of bats and indirectly decreased the likelihood of citizen science project success and promotion of bat-friendly urban planning [16,17], informed by One Health principles.

The 352 articles identified were then assessed for data and internal references discussing native bat responses to urbanisation and urban planning, utilisation of citizen science for members of the order Chiroptera, and further discussion of native species in Florida. If specific citizen science projects focussed on bats were identified, links and official websites were explored to locate more detailed information about the project and provide insights into different approaches of citizen science for native bats. Websites were identified through internal references in papers or by using Google and searching the name of the project so that the project could be further explored.

2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews of key informants in the field of bat conservation and subsequent textual and thematic analysis were then performed to develop insights into how experience and knowledge of individuals involved in the fields of citizen science and urban planning are related. These interviews further helped to explore the latent potential for citizen science to engage community members and contribute to urban planning. Key informants were selected based on their official role(s) in citizen science projects and conservation organisations involving bats or because they had authored peer-reviewed scientific papers in the field [18,19]. Using publicly available contact information, interviewees were contacted and provided with a participant information sheet and consent sheet (Appendix A). The selection of final interviewees was based on their willingness to participate, with a total of three interviews completed.

Since interviewees were located across the country, remote interviews were conducted using Microsoft Teams. The interviews adopted a semi-structured format [20] with the topics of discussion developed using information obtained from the literature review and general information about native bats in Florida, alongside discussing interviewees’ background experience, involvement with bat conservation, and citizen science involvement. Interviewees were allowed to freely answer without interruption, allowing a natural conversation and increasing the chance of personal and anecdotal experiences and opinions. The interviews were recorded and transcribed using an automated programme in Microsoft Teams and then manually checked for errors by re-watching and listening to the audio to ensure accurate transcription. Notes regarding body language, intonation, and other non-verbal cues were also included.

Following transcription, a textual analysis to identify additional citizen science projects and reference to native bats was performed, followed by a thematic analysis using an interpretivist approach. An interpretivist approach was elected due to the inclusion of multiple social aspects involved in the research topic and the need to evaluate data containing human opinions and perspectives, which could not be analysed quantitatively [21]. To perform the textual analysis, the transcripts were searched using individual key words that were also used to perform the literature review, including common names of native species (Table 1), which were more likely to be utilised in casual conversations. If found, the surrounding transcription was then assessed for further information about urban planning responses of bats, with a focus on any native species mentioned and citizen science projects. To perform the thematic analysis, the transcriptions were reviewed multiple times, allowing familiarisation with the material and identification of any important concepts and topics, followed by the development of individual codes (Appendix B) and first-cycle coding [22,23,24,25]. It should be noted that this was an iterative process where once one transcription was reviewed and coded, the prior transcriptions were reassessed to ensure no relevant data was missed [26]. Once first-cycle coding was completed, the data was reviewed and the process of expanding and condensing ideas was performed until the identification of themes was finalised [22].

An ethical review of interview methods was completed by the University of Edinburgh Vet School’s Human Ethics Review Committee and was granted approval under reference number HERC_2023_161.

3. Results

In this section, we present the results of the literature review, followed by those of the interviews. These results provide a baseline account of the practices currently employed in citizen science projects and a more speculative consideration of future possibilities in which citizen science can contribute to the development of bat-friendly urban planning utilising One Health principles.

3.1. Documented Citizen Science Inclusion in Bat Research

The review identified forty-three citizen science projects directly involving research on bats, with thirty-six having official project names and seven being referenced in research papers with no official name or title (Appendix C). Citizen science projects were found on all continents except Antarctica with three global projects, twenty-five in Europe, seven in North America, two in Africa, two in Oceania, two in Asia, and one in South America. When these projects were further explored, they revealed six primary techniques utilised for data collection that should be considered when planning projects. Minimal inclusion of Florida native species was found.

3.1.1. Variation in Data Collection Techniques Outlined in the Published Literature

Further assessment of the forty-three citizen science projects identified six research techniques, with some studies implementing multiple techniques concurrently. The utilisation of multiple techniques has been linked with more complete data sets and the ability to detect additional species that would otherwise be missed if only one technique was utilised [27].

These six research techniques were defined as follows:

- Online databases reporting sporadic sightings of wildlife—visual observation of wildlife with or without photo documentation that is reported to an online database.

- Roost and emergence counts—visual monitoring of bat roost to complete population counts or visual monitoring of roost exits at dusk to perform emergence counts of individual bats as they leave the roost.

- Visual observations excluding roost and emergence counts—visual monitoring of features that are known to attract bats and documentation of bat activity.

- Acoustic monitoring—utilisation of acoustic devices or aural monitoring to document presence of bats.

- Capture and radio-tracking—utilisation of mist or harp traps to capture bats for data collection with or without subsequent radio-tracking to record movements and identify roost locations.

- Guano collection—collection of guano from identified roosts to be further analysed.

Each of the projects was assessed for techniques utilised based on these definitions and placed into a group, with some projects being listed under multiple groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grouping of identified citizen science projects by research technique.

The most common techniques utilised were sporadic visual observation and acoustic monitoring, which were utilised in 32.5% and 30% of projects, respectively. The least common technique was guano collection at 4%. Each of these techniques can provide different data about bats and involve amateur scientists in varying capacities.

Six of the databases reporting sporadic sightings of wildlife dealt with reporting of roadkill to an online database (California Roadkill Observation System, Dieren onder de wielen, Srážky se zvěří, Projekt Roadkill, The Road Lab, and Taiwan Roadkill Observation Network). This involvement of citizen scientists allowed for improved reporting on smaller species like bats, when compared to reporting by government agents, who often only report on animals that cause vehicular–animal collisions [34]. This reporting provides important data for urban planning on how roadways affect bats; impacts that might otherwise go unnoticed.

3.1.2. Inclusion of Native Bats in Florida Within Citizen Science Projects Identified

Only three named projects and one unnamed project were found to include native species found in Florida: (i) California Roadkill Observation System, (ii) Ohio bat working group, (iii) iNaturalist, (iv) Metcalfe et al., 2023 [31]. The Florida Bat Working Group was not mentioned in any of the published literature but can be assumed to include native species in their work.

3.2. Documented Responses of Native Bats in Florida to Urbanisation

Sixty articles were included in the review pertaining to urbanisation; this allowed documented responses to urbanisation by individual native bat species (Appendix D) to be identified. There was a lack of attention to C. rafinesquii, L. seminolus, M. austroriparius, and M. grisescens, which failed to have any published information regarding urbanisation responses. The identification of the published responses allowed further recognition of specific urban planning features (UPFs), defined as aspects within the natural and manmade environment that could be altered and effect changes on native bat populations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Natural and manmade urban planning features (UPFs) that can be altered to effect change on native bat populations identified through the literature review.

Since individual UPFs will affect multiple species at once, and multiple UPFs may be working simultaneously to effect change, care should be taken to understand how each factor is working both independently and with the other features surrounding it, on all species in the region. Urban changes could mean the inclusion of additional water sources through retention ponds on a golf course, while simultaneously planting more vegetation that increases canopy cover. T. brasiliensis, for example, would make use of arboreal roost sites following the creation of a nearby water feature; this species‘ activity would be negatively impacted by increased canopy cover however. By contrast, the same changes (increased water features and canopy cover) would result in increased activity for P. subflavus. The effects on T. brasiliensis could elicit no overall change in measured activity if the two changes cancel each other out. This could make impacts on this species invisible while increased measured activity of P. subflavus could be seen. This scenario displays the complicated interactions between multispecies bat communities when urbanisation alters multiple UPFs simultaneously. Understanding that an effect is still occurring is crucial but requires an appreciation of each species’ individual responses. This consideration of multiple species being affected by each UPF and the concurrent effects of multiple changes makes planning difficult, but it can be improved as knowledge gaps improve alongside increased data collection, displaying how bats are responding to environmental change.

While wind turbines were commonly cited to affect bats, there are currently no wind turbines in Florida, USA [35], so they are not currently considered in urban planning when looking at native bat species in the state.

3.3. Interviews of Individuals Involved in Bat Conservation and Research

Variations in experience and knowledge can alter how ideas are put into practice, creating an understanding of how experience and knowledge of individuals can influence how One Health principles can be integrated into the future of bat conservation and bat-friendly urban planning.

Three interviews were conducted (Table 4) and analysed using the previously described methods. Throughout the remainder of the paper, the interviewees will be referred to using the abbreviations noted after their name.

Table 4.

Interview information including date, interviewee identifier, and professional title.

3.3.1. Textual Analysis of Interview Transcriptions

A textual analysis of transcription material revealed specific references to native bats and citizen science projects that were not noted in the published literature alongside two additional challenges that bat data collection faces: (i) high workload for a single person in an organisation due to their responsibility to monitor and classify levels of concern for all species in an entire order or family; (ii) specific monitoring challenges for Florida bats.

The transcriptions made mention of native species E. floridanus, E. fuscus, M. grisescens, T. brasiliensis, L. cinerus, and P. subflavus by their common names and elaborated on some personal experiences with the species and recognised population gaps in the field due to inaccurate population counts associated with roosting behaviours and challenges with elusive and nocturnal behaviour, which is consistent with the previously published literature.

Delays in assessments of individual species due to high workload assignments to individuals were noted for the critically endangered endemic bonneted bat, E. floridanus, where Interviewee 1 noted that “The last time the bonneted bat was done was 2016 and it was just listed in 2013 because it hadn’t been seen for many years. It was thought to have been gone.” The lack of an assessment by the IUCN since 2015 [2] represents a significant data gap and is further supported by the fact that there are contradicting designations at the international, federal, and local levels. The IUCN designates three as vulnerable, whereas the federal government lists two as endangered; the state government meanwhile lists all but two as species of greatest conservation need (Table 5). This is of concern for E. floridanus, the only endemic bat species within the state, whose international threat status is lower than the local status, indicating a need for more comprehensive assessments and reporting. These contradictory status designations are concerning, given that urban planning policy and protections accorded to a species by the federal and local government are influenced by these status designations. When specific attention is given to the federal distinction, this allows the species to be protected by the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and further allows the authorisation of financial assistance [36].

Table 5.

Native bats found in Florida and their associated extinction status designated by the IUCN, federal USA government, and Florida state government.

Difficulty in monitoring was referenced in many publications; interviewees also noted the inability to do accurate population counts for native species due to the challenges in locating, alongside the lack of manpower. Three native species that roost solitarily and/or in foliage were referenced, but this could be expanded to all native bat species with similar roosting patterns.

“Tricolors can roost in a little dead leaf clump and bonneted bats, the only reason we find roosts is through radio tagging them and following them to their roosts.”Interviewee 1.

“Even when we were radio-tracking evening bats, most of them are solitary entries.”Interviewee 2.

N. humeralis being a solitary rooster is also inconsistent with published knowledge. This is likely due to males commonly being solitary roosters during the summer months, with the larger colonies, mainly containing females, being the main roosts identified [37]. Distinctions between male and female roosting behaviour could lead to researchers gathering data preferentially on a specific gender, with urban planning changes eliciting greater or unknown effects on one gender if only colonies of females are being identified and protected.

Complications with roost monitoring were noted in geographically separate populations of bats, with E. floridanus specifically discussed.

“It’s that the bats in Miami are very genetically distinct from the bonneted bats on the West Coast, and we’re not sure to what level yet …. It could be that that’s why that bat takes bat houses a lot quicker and more readily or it could be that it’s just way more limited over there.”SS.

All of these statements reiterate the challenges associated with attempting to monitor an elusive species. Interviewee 3 outlined a previously unidentified citizen science programme, the Wisconsin Bat Program (https://wiatri.net/inventory/bats/, accessed on 30 October 2025), which produced “amazing information” focusing on acoustic monitoring, roost emergence, and community education, which now has “260 volunteers” with “150 roosts being counted last year” according to Interviewee 3. Links to yearly reports (https://wiatri.net/inventory/bats/news/WBPnews.cfm#RoostReports/, accessed on 30 October 2025) highlighted the programme’s ability to publish detailed population data for the area. This identification of new roosts and long-term data on existing roosts has provided the area with a good grasp of population numbers and the roosting activity of two local bats, including E. fuscus, making the programme a good example of successful inclusion of citizen science into population data gap improvement for local bat populations.

The mention of Zoo Miami by Interviewee 1 also led to the identification of an additional citizen science project in Florida, Miami Zoo Bat Lab, which allows reporting of sporadic sightings of E. floridanus through their website [38].

While Interviewee 2 was found to be highly involved in citizen science, including the publication of a paper in the literature review [29], many of the projects she described did not have official names or were associated with graduate research projects and community outreach but outlined significant training for the next generation of scientists, including roost monitoring, acoustic monitoring, and mist netting with subsequent radio-tracking, resulting in an improvement of knowledge and correction of misconceptions about bats that the local community previously held.

3.3.2. Thematic Analysis of Interview Transcriptions

The thematic analysis of interviews outlined two themes, (i) individual perspective and (ii) societal interconnections, which were found to affect change in the field of bat conservation. The idea that individual perspectives evolve from ongoing experiences/events and can influence knowledge and assumptions changes the current and possible future realities for bat conservation. This “waterfall” of events is based on the idea that the objects, processes, and details surrounding it are ontologically interdependent, and as events occur, there is a creation of a complex web of emotions, transitions, experiences, relationships, and events [39]. These complex weavings were outlined in every interview, with all participants constantly demonstrating them through their storytelling. Each individual, organisation, and element of society is interacting and evolving as a complex network of interrelated actors influencing how change can arise [40]. It should be noted that while the term individual is used, this may also be used to refer to an individual group or organisation, rather than an individual person.

Individual Perspective

Each stakeholder involved in bat conservation, whether through urban planning, citizen science, community activities, or just walking through a neighbourhood, will have unique perspectives that can evolve in response to their experiences and interactions [41].

All three interviewees identified experiences in bat conservation in the community, with some resulting in an improved perception of bats and others causing a worsened perception. Below, we discuss some examples of altered perceptions outlined in the interviews, followed by how we can support the evolution of individual perspectives that benefit and promote bat-friendly urban planning and the involvement of citizen science. These examples illustrate how improved knowledge and attitudes surrounding engagement in citizen science were linked to conservation behaviour, consistent with Knowledge–Attitude–Behaviour models (KAB models) [42].

Example 1: Interviewee 2 outlined how a family member’s perspective shifted when they were invited on a transact walk, even after having participated in them previously.

“So, he would be doing it all and it’s been in the last couple years; He’s like ‘don’t ask me to do the transact walks. I can’t do them’ and he is so unconfident with his eyes because he needs more light. You know, they get... He’s getting more and more worried about his footing and not being stable and if he falls. So he’s not putting himself in a position that does that.”Interviewee 2.

Acoustic surveys and mist netting require individuals to be able to navigate through nature, often in low lighting and on uneven terrain. This experience for the individual, despite being a familiar experience, was now met with worry and lack of confidence, altering his perspective of the activity and whether he would continue or recommend it to others. This example demonstrates how, in the push to involve individuals in bat conservation, we can inadvertently be shaping negative perspectives. The current and changing physical capacities of individuals were not discussed in the literature; this highlights the need for a more inclusive approach that is responsive to individual needs.

Example 2: Experiences between wildlife biologists and other actors in the community, especially when there was disruption or destruction of bat roosts, could leave a negative impression about community engagement. This is palpable in the following quotes:

“If they don’t know bats are roosting in their palm trees, and they... if they don’t know about it, that’s probably best because if they knew about it, they probably try to get rid of them. You know... I don’t know... but I tend to rule that way. Like, let’s just keep the lid on that.”Interviewee 1.

“But even in that instance, you know that hour of recording, one night we have footage of a woman going up and shaking the bat house to try and get them out... So yeah, it’s always been a struggle for us as to like, yeah, how much do we advertise the fact that there’s bats in, in these state parks and things like that.”Interviewee 3.

There is a constant fear that the negative perceptions that have plagued the species for years will give rise to disruption and destruction. These negative perceptions can be counteracted, however, and the interviewees emphasised the potential to improve perceptions through different modes of engagement. Interviewee 2 utilised the emotional connection individuals had to gardening and improving the success rates of bat box placement alongside concurrent community education to help individuals reframe their views and further deepen their knowledge and emotional connection to bats.

“So, I consulted with everybody and instead of lots of people going, I got a bat box and it didn’t work. We got lots of people like “It worked! We got bats in it”Interviewee 2.

“One of the simplest things, if you got bats in your loft, put a sheet out. That is great on your roses and the minute you say that, like you do, you realize how expensive this is? This fertilizer. This is excellent.”Interviewee 2.

Both of these statements represent the excitement that can be generated when community members are clearly engaged and enthused, deriving satisfaction from improving roosting opportunities for bats.

Interviewee 2’s focus was also on the exposure of community members, mainly students and their parents, to scientific conservation.

“They ended up doing field surveys for our grad students and turned out to be like the best. We got the rabies and by the time that they were eighteen, they were some of our best mist netters. They were out there radio tracking like and then they come to university and they do nothing but. The experience they got and in doing it was insane. It’s like proper science that they ended up doing.”Interviewee 2.

The inclusion of high school students in these studies not only improved data collection but also students’ knowledge of bats, proficiency in capture surveys and radio-tracking, and knowledge of scientific practice. Sustained engagement in a project allowed students to become more knowledgeable and proficient and for their appreciation of and respect for bats to deepen. These positive effects were also noted to affect family members, who became involved and continued after students had graduated.

Each individual experience and success described fostered excitement and satisfaction, which may be paramount to continued individual and community involvement, along with continued positive evolution of individual perceptions [43,44].

To widen potential participation pools and increase participation numbers without perpetuating negative perceptions, existing barriers to participation must be identified and addressed. This can be incorporated into the planning of citizen science projects. The unique need for bat monitoring to mainly occur at night needs further consideration when planning projects, as many participants in these projects tend to be in their 50s or 60s [45]. Projects that do not require higher levels of physical activity, like roost counts, monitoring of anthropogenic structures like swimming pools, or involvement in improved urban planning features and community outreach, might be more appropriate for such demographics. Demographics will not only influence physical abilities but can also influence time commitments, geographic location, safety to perform data collection, financial support abilities, and overall ability to participate. While older demographics and retirees may have more flexible time availabilities and be able to invest in higher time commitments, their physical abilities may preclude them from participation, while younger demographics may have limited time and ability to participate independently but may be more physically capable. Evolution of individual perspectives due to emotional, mental, and physical responses to exposure to a new piece of information can be highly influential in the success of citizen science and urban planning, since their investment in conservation of this order is directly related to their attitudes. Improvement in the perspectives of individuals has the power to influence involvement in citizen science and support of bat-friendly urban planning and its subsequent success or failure [46].

Societal Interconnections

The study of the complex relationships between society and the environment provides insight into how bat conservation can better fit into an evolving world with growing urbanisation while applying One Health principles [47]. The inclusion of social sciences and the evaluation of societal relationships requires a more adaptable and open mindset and the acceptance that it is a dynamic [48] and continuously evolving field. All three interviewees discussed how the progression of projects and the field of bat conservation revolved around a network of societal relationships, with references to numerous actors (organisations and individuals) who played a role in its success or failure. Although the discussion surrounding these relationships is the focus of this section, the exclusion of additional organisations or groups does not indicate that they are not involved in this field, but rather that they were not mentioned in the interviews or the literature.

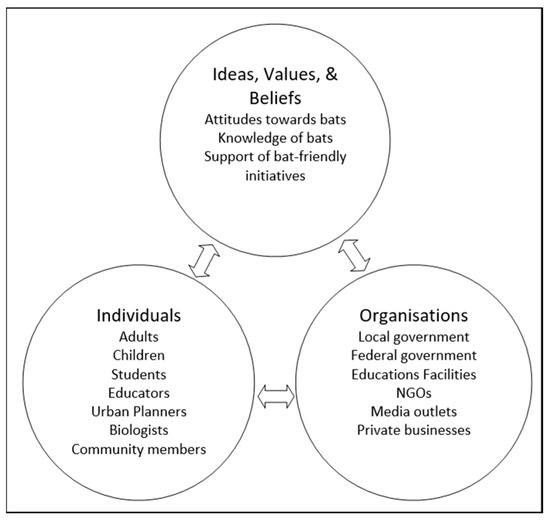

Utilising the data identified in interviews and information garnered in the literature reviews, a large number of interconnected actors were identified, allowing us to speculate about how they might fit into citizen science and nature-positive urban planning. This requires understanding the development of values governing society. Societal values, beliefs, and attitudes can be considered part of a closed cyclic loop as described by Salem and Rauterberg [49], with an altered understanding of how these effects are felt bidirectionally, as depicted and outlined in relation to bats (Figure 1). This figure serves to identify the individuals whose unique perspectives contribute to the governing pieces of society and the development of cultural ideas, values, and beliefs. This figure is only a representation of connections discussed in interviews, not all connections possible, as this is not available without a larger review.

Figure 1.

Cyclic representation of the three components of society and the bidirectional influence they have on each other in relation to bats. This figure was produced through the amending of a related figure developed by Salem and Rauterberg [49] to help outline the relationship between society components in relation to bats.

Individuals can not only interact with other individuals within their sphere but are also part of larger pieces of society that interact with other spheres, with both levels being involved in urban planning and citizen science. Interactions between individuals and larger organisations can influence how we approach urban planning and citizen science. Identifying these larger connections can show where influence in these fields can be enacted.

Approaching bat conservation through One Health is transdisciplinary and requires the involvement of many individuals, especially those involved in the management and alteration of UPFs. While the government is primarily responsible for this, private property owners can also effect change with the addition or removal of water sources or vegetation on their property [29]. In multiple interviews, interviewees discussed individual cooperation with other organisations for successful conservation initiatives.

“Just before the holidays started, we were working with Florida wildlife corridor to try to weave in Florida bonneted bat into some of that work that’s more like panther and bear related.”Interviewee 1.

“I got together with Boy Scouts of America who need their woodworking badge or whatever it is and said basically, if any of you want do this as woodworking, make me these bat boxes and then I’ll have a bat box blitz every year or so depending on how many bat boxes you guys make me.”Interviewee 2.

“We had bats wanted posters that we would put up at libraries and, you know, gas stations and things like that. So, that was a way we tried to reach, you know, state-wide being like, hey, we need, you know, report your roost site if you’re interested, but we continue to get not only new roost sites, you know, new land owners, but also interested volunteers who don’t have, you know roost sites of their own.”Interviewee 3.

The connections that people have with one another and both their role in society and how they interact with the other parts of it can have deep-reaching effects on citizen science and urban planning through the evolution of our values, beliefs, and attitudes surrounding a field. This variable can change depending on individual perspectives and may be highly dynamic and variable in individual geographic regions. Consideration of this development and evolution may require constant review and amendment of approaches used for this field at the local, regional, and national levels.

3.4. Limitations of the Literature Review and Interview Analysis

The results produced from this review, while providing a baseline, should not be considered a comprehensive review of citizen science projects or a complete analysis of how societal relations and perspectives are influencing bat-friendly urban planning. Further assessments of additional databases and engagement with the grey literature sources would provide details of unreported work/initiatives. The three key informant interviews explored insights into the potential for citizen science to contribute to improvements in urban planning for bats and humans. Whilst this number of interviews is limited, it was focussed on quality insights from experienced professionals able to speculate about the need for humans and bats to learn to co-exist. As more people working in this field consider how these potentials might be realised, it is possible that insights into collaboration between citizens, volunteers, scientists, and conservation professionals may evolve. A deeper understanding of underlying themes could also be achieved through interviews with other stakeholders, including members of the public, urban planners, ecologists, pest management companies involved with wildlife exclusion of urban buildings, government officials, and lawmakers. By repeating interviews as the field evolves, shifting perspectives may also surface.

There should also be an acknowledgement of the utilisation of the researcher as an instrument in qualitative interviews, which recognises that the researcher’s positionality and reflection can influence data collection, interpretation, and analysis despite attempts to remain unbiased.

4. Discussion

This project has set out to explore the current citizen science projects involved in bat conservation, the documented effects of urbanisation on native bats in Florida, and the potential for citizen science to contribute to bat-friendly urban planning through understanding the connections between them and society. Bat conservation is unique in that the creatures we are aiming to protect are difficult to study and have suffered from decades of persecution and negative public perceptions; such attitudes towards bats can significantly hamper efforts to encourage bat-friendly urban planning. Ecosystem health and critical ecosystem services influenced by these species are all at risk without a better understanding and intervention. Florida serves as an example location where the urgent threat of urbanisation alongside numerous data gaps and a lack of understanding of how society and bats are interconnected hinders our ability to preserve this and to create and maintain healthy cities. As all bats in Florida are insectivorous, the loss of their ecosystem services could not only impact our ability to limit emerging infectious disease threats but would also impact our agricultural productivity [3].

Interviews helped to exemplify the connection that citizen science has to the success of bat-friendly urban planning initiatives by outlining how shifts in attitudes and perceptions can stimulate change. The idea of shifting our perspectives and embracing new and innovative citizen science projects centres around the idea that as urbanisation continues, society must account for how we are connected to the ecosystems around us. This understanding can help us to create and sustain healthy cities through a more-than-human, multispecies approach [50].

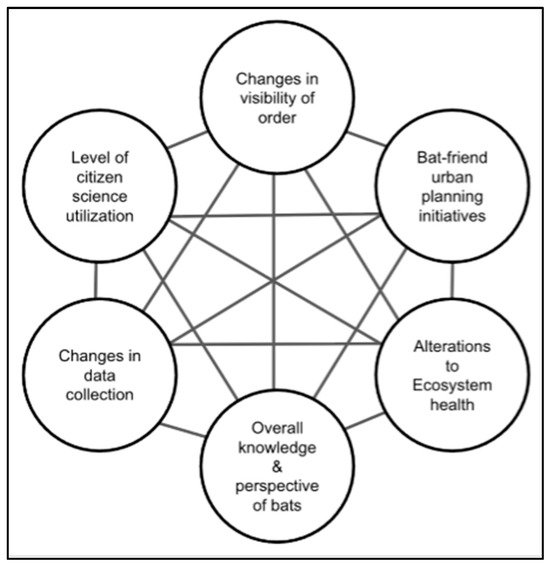

Citizen science can facilitate how individuals in society and society as a whole recognise and understand the importance of bats in the ecosystem and evolve their perspectives and relationships. The ability to make bats visible to society while also improving individual perspectives can lead to further inclusion of citizen science for data collection and community support of bat-friendly urban planning. This is not a single connection but rather a complex web of interconnected multi-directional factors influencing their evolution and contributing to the success of bat-friendly urban planning (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Multi-directional connections between factors influencing urban planning, citizen science, and ecosystem health that feedback on each other, resulting in continuous evolution.

Improvements in urban planning to promote bat-friendly neighbourhoods not only require increased knowledge of bats but also the willingness of individuals, communities, local and national government, and various stakeholders to support bat conservation. As more people move to urban areas and urbanisation occurs, the idea that human needs and satisfaction will shape these changes [51] can play a role in how we approach bat-friendly urban planning and the changes and connections that we want to effect to facilitate it.

By understanding how opportunities are provided through citizen science and its connections to urban planning, it becomes possible to envisage a more ecological approach to bat-friendly urban planning. This inclusion of citizen science also allows communities to move beyond factual knowledge and misconceptions, bringing deeper conservation challenges to light with more respect for and appreciation of species that live in the dark and have been much maligned. Without such mutual respect and participatory involvement, urban planning initiatives will remain biassed towards a narrow unecological view of what it is to be human.

What might more ecological and therefore bat-friendly urban planning look like? Such an approach would integrate knowledge of how urban planning features (UPFs) impact bats. Currently, the lack of published responses for C. rafinesquii, L. seminolus, M. austroriparius, and M. grisescens in Florida represents a significant data gap, impacting the preservation of ecosystem health and services where these species are present.

The data from the literature review, knowledge of data gaps, and known variations in how individual species utilise the environment helps us understand what is needed to support local populations. Differences in habitat preference, diet composition, roost preference, and responses to urbanisation can vary widely. Grouping of bats by functional guilds provides better insight into tolerance to urbanisation and which data collection approaches and urban planning practices would be beneficial. This organisation into guilds has been outlined by Denzinger and Schnitzler (2013) [52] and allowed us to organise bats based on foraging habitats and foraging modes, but the inclusion of additional guilds based on roosting structure preference and roosting behaviour can further help direct project focus (Appendix E). While caution should be used when placing bats into guilds due to some inconsistent responses within genera [53] and geographically, as discussed by interviewees, it can still provide insight into what approaches will benefit individual species.

Citizen science has many definitions but centres around the inclusion of highly skilled amateur scientists with significant training and extends to members of the public with limited scientific background to conduct scientific research in a wide range of capacities [54]. The research techniques outlined here provide numerous ways that data can be collected on members of this order. Urban planners may be well positioned to create opportunities for wider, more inclusive participation, recognising that individuals may have different contributions depending on their evolving perspectives and physical, mental, and emotional capabilities. Building on existing citizen science projects and UPFs, we can start to reimagine what projects could help to positively evolve urban planning policies for Florida’s native bats and human–bat relationships.

Drawing on the citizen science projects identified and interview discussion alongside the known responses to urbanisation and known behaviours of native species, we have developed proposals for new projects (Table 6). These examples are not exhaustive and can be expanded on depending on the demographics of an area and new information. GIS data outlining roads, buildings, and known water sources can complement this work and may already be readily available through local municipalities.

Table 6.

Proposed projects based on UPFs identified, documented responses by native species, and documented citizen science projects currently being utilised.

Species that utilise human structures and bat houses could benefit from roost emergence counts and roost monitoring where this is linked to improving roost availability within urban environments. Bat box installation in areas with limited roosting options within the range of C. rafinesquii, E. floridanus, E. fuscus, M. austroriparius, M. molossus, N. humeralis, and T. brasiliensis could foster human–bat relationships. Tree-roosting species, including L borealis, L. cinereus, L. intermedius, and L. seminolus, are less visible and require the use of acoustic monitoring or capture and radio-tracking to monitor efficiently. The utilisation of different techniques that do not centre around direct data collection for these bats (e.g., habitat mapping) could allow habitat quality and connectivity to be improved. Projects focussed on environmental features could provide better information regarding water sources, vegetation, and anthropogenic features affecting bat activity, as demonstrated by other projects [55,56]. Promoting opportunities for outdoor activities can cultivate an improved perception of nature and support learning about bats [57].

Over thirty percent of the projects identified utilised online databases for reporting wildlife sightings. With over half the global population having a smartphone, with some high-income countries like the USA reaching over 80% [58], there are growing opportunities for citizen participation. Technological development will continue to impact how data is collected, with opportunities for this to become automated and easier to contribute to and learn from. While iNaturalist already allows sporadic wildlife sightings, the inclusion of bats was minimal, with only 1778 bat observations since 2013 [59], and no other publications referenced online databases for natural features pertaining to bats in Florida. The addition of a roadkill monitoring database in the state could aid in understanding how our roadways are affecting bats. By increasing the accessibility of data reporting in Florida through additional databases, we could expose thousands of individuals to bat conservation and bring more conservation issues to light. An emerging technological device referenced in interviews and a project in Mexico City [32], EchoMeter Touch 2 (Wildlife Acoustics Inc., Maynard, MA, USA), already provides a more accessible path to involvement for community members.

E. floridanus is the only endemic bat and has an echolocation call that can be perceived by the human ear, making them a good candidate for implementation of an aural acoustic citizen science project, allowing the identification of activity without any additional monitoring equipment. This, alongside some populations’ willingness to utilise bat houses, could greatly increase their visibility and monitoring opportunities.

Florida is home to more golf courses than any other state, with 1250 golf courses covering an estimated 200,000 acres of land [60,61]. These can be an important foraging and roosting site for native bats, including the endemic E. floridanus, which is currently endangered. Golf courses and other green spaces offer significant opportunities for citizen engagement and science, given the numbers accessing such spaces [62,63].

Given the diverse behaviours and responses of native bats and human stakeholders, and the various ways citizen science can be practised, there is no singular approach that would result in a complete assessment of native bats and no singular urban planning initiative that would help all native species. Interviews further revealed that additional challenges in monitoring include evolving knowledge of different geographic groups, limited manpower, and the inability to find roosts for many species. They further outlined that varying experiences influence individual perspectives and how societal connections play a role in successful bat conservation. The relationship between citizen science and urban planning is highly dynamic and coevolves based on a complex web of individual and societal perspectives and connections alongside our knowledge of native species. By understanding this coevolution, along with utilising current knowledge of native species, we can better understand how citizen science can influence urban planning in Florida.

To fully understand what projects could be implemented to improve data gaps and how to improve citizen science involvement that supports the bat community and can move us toward a more-than-human approach to urban planning, more detailed studies focussed on smaller geographic bat communities in the state, the public’s current demographics and perspectives surrounding bat conservation, and which stakeholders are influencing urban planning policy would be needed. This approach could change the way the community views bat conservation and lead to the preservation of valuable ecosystem services while improving both the health of the bat and human community alike.

5. Conclusions

Florida represents an important case study documenting data gaps of native bats, limited citizen science, a lack of a published review of endemic bat responses to urbanisation, and the urgent need for outlining a path forward during an era of large-scale urbanisation. This study demonstrated that the coevolution of citizen science alongside bat-friendly urban planning could contribute to bat conservation and the stewarding of complex urban ecosystems. This review of published efforts outlined the many possible approaches to involving the public; the key finding here, however, highlights the role played by individual perspectives and societal connections in evolving human–bat relations and in building the case for bat-friendly urban planning. There is therefore a need for a strategic change in how citizen science is practised, with attention being paid to promoting citizen engagement, both individually and collectively, across society. Individual perspectives and assumptions regarding bats and the beneficial ecosystem services they provide evolve through the learning arising from active participation in bat conservation. Attention to the quality of individual experiences is important as individuals (whether volunteers or citizen scientists) can present with particular needs. Attention to how individuals are matched to an activity and to how these activities are facilitated and supported is therefore likely to be important. An assessment of where these contributions fit into the wider planning picture is also needed so that contributions feed meaningfully into the planning ecosystem.

The coevolution between bat-friendly urban planning and citizen science will be complicated by the large number of stakeholders and associated interests. Emphasising ecological interests over narrow self-interest will be essential. These complex societal–bat interrelations can be improved by providing additional opportunities for citizens to study, learn to understand, and appreciate bats and the contributions made by bats to ecological health. This complexity is both biological and social but is also emergent, reflecting the emerging intelligence of a responsive coevolving multispecies system. At a granular level, society’s overall understanding of citizen science involvement and urban planning and development hinges on society’s emotional, mental, and psychological views surrounding the liveable future we aspire to and the critical role bats play in such a future [47]. Improving societal understanding can thus allow human knowledge of, and attitudes towards, bats to evolve beyond mere stereotypes derived from popular fiction; this shift can potentially play a key role in supporting bat-friendly urban planning.

Urbanisation is going to continue throughout Florida, with continued habitat degradation and destruction for native species of bats. Implementing more bat-friendly urban planning will be critical for local bat populations, thereby also preserving ecosystem services and health. This study has speculatively explored the potential for these informal and formal projects to meaningfully contribute to evolving human–bat relations and, on a wider scale, to improve urban planning policies in relation to bats. This will benefit from the development of a transdisciplinary One Health approach where citizens, scientists, conservation professionals, urban planners, and other stakeholders come together to form Communities of Practice committed to ecologically sustainable ways of planning for a future where ecosystem services, such as insect predation, can be maintained during periods of urbanisation.

The coevolution of citizen science and urban planning may be key to the success or failure of bat conservation and the ability to maintain the health and ecosystem services bats are providing in Florida. It is hoped that the integration of citizen science into urban planning will benefit ecosystem health, wildlife conservation, and a more considered approach to stewarding urban blue and green spaces for human health and wellbeing. Ultimately, this may support a more collaborative, biophilic approach to urban planning for healthy more-than-human cities [64,65].

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, analysis, writing—original draft preparation: N.S.; supervision, review, and editing: G.C. and P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the R(D)SVS Human Ethics Research Council (HERC) reference number HERC_2023_161 on 30 November 2023. The University is a signatory to both the Universities UK (UUK) Concordat to Support Research Integrity and the UK Research Integrity Office’s Code of Practice for Research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. The raw data from interview transcription is not available due to privacy restrictions set forth in ethical approval. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge those who participated in interviews, allowing the identification of key themes in the area of bat conservation. We also gratefully recognise Alice Hovorka for introducing us to the concept of “healthy more-than-human cities” through the keynote lecture delivered at the Multispecies Health in the City Workshop, held in Edinburgh 29–30 April 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALAN | Artificial light at night |

| FBWG | Florida Bat Working Group |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| NGO | non-profit organisation |

| SGCN | species of greatest conservation need |

| UPF | urban planning features |

| USA | United States of America |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Key Informant Information Sheet

PRELIMINARY PROJECT TITLE

Examination of how citizen science and volunteer-led projects can fill data gaps for endemic bats of Florida, USA, to assist in urban planning: a review.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT?

The goal of this project is to provide evidence that citizen science can provide an additional source of data acquisition for endemic bats in Florida that contain numerous data gaps due to their elusive nature. This data can then be practically utilised in urban planning to help better conserve ecosystems and ecosystem services provided by bats.

A systematic literature review will be completed of available evidence over the last twenty years for areas of urban planning that can influence bats and what citizen science projects have been or are being performed currently. This will then be used in conjunction with interviews of key informants in the field to help support citizen science and volunteer-led projects and identify how they can be utilised in Florida, USA.

WHY HAVE I BEEN INVITED TO PARTICIPATE?

You have been invited to participate in this study as a key informant because you are involved in bat conservation through one or more of the following ways:

- –

- Research and/or data collection

- –

- Citizen science

- –

- Environmental consulting

- –

- Urban planning

WHAT DOES TAKING PART INVOLVE?

If you agree to participate in the project, a 1–2 h interview using Teams or University Zoom will be scheduled at a time that is convenient for you to discuss a number of topics and questions pertaining to bat conservation, your participation in research and/or data collection, your participation in citizen science, and any other areas of bat conservation that you feel is important to consider. This will be audio-recorded/video-recorded. At the start of the recording, you will be asked your name and title. If you would prefer to use a pseudonym or different title you can indicate so at this time. The name and title you provide will be utilised in the transcript and final project. The recording will then be transcribed into a written copy that will be included as an appendix in the final project. You will be provided with a copy of this transcription within 1 month of the interview.

ARE THERE ANY POSSIBLE RISKS OR DISADVANTAGES IN TAKING PART?

The main risk in participating in the project is personal identification. While your name and/or title may not be used, anonymity is not guaranteed due to the small number of people in the associated community.

WHAT ARE THE POSSIBLE BENEFITS OF TAKING PART?

By sharing your experiences and knowledge with us, you will be helping the project team gain additional insights into the current data collection practices and concerns surrounding bat conservation.

WILL I BE REIMBURSED FOR ANY EXPENSES OR FOR MY TIME?

No reimbursement will be provided for participation in the project.

WHAT IF I WANT TO WITHDRAW FROM THE PROJECT?

Agreeing to participate in this project does not oblige you to remain in the study or to have any further obligations to the research project or team. If at any stage you no longer want to be part of the project, you can withdraw from the project by contacting Nicole Sarver at s2136914@ed.ac.uk prior to 30 April 2024.

HOW WILL MY DATA BE LOOKED AFTER DURING THE PROJECT?

All personal details are not available publicly. This will include contact details, addresses, phone numbers, and raw video/audio footage. These will be kept strictly confidential within the research team (myself and project supervisors). Data will be stored on university secure servers, in accordance with the UK GDPR and Data Protection Act 2018, any local Data Protection legislation (if applicable), and the latest University of Edinburgh data security protocols.

WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO MY DATA AFTER THE END OF THE PROJECT?

The original video-recording/audio-recording will be destroyed after submission of the project on 30 June 2024. After the project has been accepted and finalised, all personal data will also be destroyed. The appendix containing the transcriptions from the interviews will remain with the final project. The information included in the final project may be considered for presentation at conferences, publication, and additional projects.

WHAT WILL HAPPEN WITH THE RESULTS OF THE RESEARCH PROJECT?

The data obtained from these interviews will be utilised in a student dissertation for completion of degree. The University of Edinburgh will retain this dissertation.

WHO HAS APPROVED THIS PROJECT?

This research project has been approved through the ethical review process at the University of Edinburgh.

CONTACT FOR FURTHER INFORMATION

If you have any further questions about this project, please contact Nicole Sarver ats2136914@ed.ac.uk.

THANK YOU

Thank you for taking the time to read this Participant Information Sheet. If you would like to participate, please sign the following form and return to Nicole Sarver at s2136914@ed.ac.uk.

Appendix A.2. Key Informant Consent Form for Audio- or Video Recording and Transcription

CONSENT TO PROJECT PARTICIPATION, AUDIO- OR VIDEO RECORDING & TRANSCRIPTION

By signing below, you are agreeing that (1) you have read and understood the Participant Information Sheet, (2) questions about your participation in this study have been answered satisfactorily, (3) you are aware of the potential risks (if any), and (4) you are taking part in this research study voluntarily (without coercion).

This study involves the audio or video recording of your interview with the researcher. Only the research team will be able to listen to and/or view the recordings.

The tapes will be transcribed by the automated transcription function and checked for accuracy by the researcher. Transcripts of your interview may be reproduced in whole or in part for use in presentations, publications, or further products that result from this study. Only your indicated name and title will be included in the final transcription but anonymity will not be guaranteed due to geographic identifiers that may be included in the interview.

By signing this form, I am agreeing to participate in the project and allowing the researcher to audio or video record me as part of this research. I also understand that this consent for recording is effective until the following date: 30 June 2024. On or before that date, the recordings and associated transcriptions will be destroyed.

Participant’s Signature: ______________________________________Date:__________

Appendix B

Table A1.

List of first-cycle codes.

Table A1.

List of first-cycle codes.

| Anthropogenic Beauty Communication Community involvement Data gap Destruction Distrust Education Excitement Experience Fear Financial | Green space Hope Human activity Improvement Inequality Influence Inspiration Learning Legislation Misinformation Negative perceptions Obstacle | Opportunity Outreach Partnership Passion Pessimism Storytelling Success Teamwork Technology Unknown Urbanisation Urban planning |

Appendix C

Table A2.

Named citizen science projects directly involving data collection on bats, geographic location, the literature citations, and identified websites.

Table A2.

Named citizen science projects directly involving data collection on bats, geographic location, the literature citations, and identified websites.

| Project Name | Location | Citation | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akaya | Japan | [66] | https://www.nacsj.or.jp/akaya (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Akustika | Malta | [67] | None found |

| Art Data Banken | Sweden | [68] | https://www.artportalen.se (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Backyard Bats Project | USA | [69,70] | https://www.azgfd.com/wildlife-conservation/living-with-wildlife/backyard-bats-project (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Baobab Blitz | South Africa Zimbabwe | [71] | None found |

| Bat Detective | Global | [72] | https://www.batdetective.org (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Bat Tree Habitat Key | UK | [57] | http://battreehabitatkey.co.uk (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Programa de seguimiento de Murciélagos (Eng: Bat Monitoring Program) | Spain | [73,74,75,76] | https://www.batmonitoring.org (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Bechstein’s Bat Survey | UK | [77] | https://www.bats.org.uk/our-work/national-bat-monitoring-programme/past-projects/bechsteins-bat-project (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| California Roadkill Observation System | USA | [78,79] | https://wildlifecrossing.net/california (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Climbers for Bat Conservation | Global | [80] | https://climbersforbats.colostate.edu (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Danish Mammal Atlas | Denmark | [81] | None found |

| Darwin Initiative | Bosnia Bulgaria Hungary Moldova Romania Russia Serbia Slovenia Ukraine | [82] | https://www.darwininitiative.org (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Devon Greater Horseshoe Project | UK | [83] | https://devonbatproject.org (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Dieren onder de wielen (English: Animals Under Wheels) | Belgium | [79] | https://old.waarnemingen.be/vs/start (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| eFlurikkus | Estonia | [84] | https://elurikkus.ee (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Eidolon Monitoring Network | Africa | [85] | https://www.eidolonmonitoring.com (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Finnish Biodiversity Information Facility | Finland | [86] | https://laji.fi/en (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Fledermausforscher in Berlin (English: Bat researchers in Berlin) | Germany | [87] | https://www.fledermausforscher-berlin.devigi (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Indicator bats program | Bulgaria Hungary Romania Russia Ukraine UK | [76,88] | https://ibats.org.uk 1 (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| iNaturalist | Global | [89] | https://www.inaturalist.org (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| iRecord | UK | [90] | https://irecord.org.uk (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Irish Bat Monitoring Program | Ireland | [89] | https://www.batconservationireland.org/what-we-do/monitoring-distribution-projects (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| MEGA Murray-Darling Microbat Project | Australia | [91] | https://megamicrobat.org.au (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| National Bat Monitoring Program | UK | [76,88,92,93,94,95] | https://www.bats.org.uk/our-work/national-bat-monitoring-programme (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Nature Mapr | Australia | [96] | https://naturemapr.org (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Norfolk Bat Survey | UK | [97,98,99] | https://www.batsurvey.org (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Ohio Bat Working Group | USA | [100] | https://u.osu.edu/obwg/get-involved (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Papanapanki | Finland | [101] | https://blogs.helsinki.fi/batscience/papanapankki (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Projekt Roadkill (English: Project Roadkill) | Austria | [78] | https://roadkill.at/en (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Southern Scotland Bat Survey | Scotland | [102] | None found |

| Srážky se zvěří (English: Animal-Vehicle Collisions) | Czech Republic | [78] | Srazenazver.cz |

| Taiwan Roadkill Observation Network | Taiwan | [78] | https://roadkill.tw/eng/about (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| The Road Lab (previously Project Splatter) | UK | [78] | https://www.theroadlab.co.uk (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Vigie-Chiro | France | [103] * | https://www.vigienature.fr/fr/chauves-souris (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

| Waarneming.nl | Netherland | [104] | https://waarneming.nl/ (accessed on 30 October 2025) |

* This project was mentioned in 38 different publications with data collected utilised to discuss ALAN. The first publication from alphabetical order of the results is included here as it allowed initial identification of this project. 1 The only website able to be identified through references in the literature and internet searching was the indicator bats program for the United Kingdom despite being active in multiple other countries.

Table A3.

Unnamed projects with description of citizen science inclusion for bat data collection, geographic location, and literature citation.

Table A3.

Unnamed projects with description of citizen science inclusion for bat data collection, geographic location, and literature citation.

| Project Description | Location | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Acoustic monitoring performed by commercial river guides | USA | [31] |

| Acoustic monitoring and mist netting in Manatí, Puerto Rico | Puerto Rico | [27] |

| Analysis of museum pieces containing notes from Matses Indians in Amazonia | Amazon 1 | [105] |

| Collection of guano from roost sites in New Hampshire, USA | USA | [33] |

| Counting of grounded bats during mass mortality event at Durham Cathedral | UK | [28] |

| Mexico City residents utilise EchoMeter Touch2 to collect acoustic data in city | Mexico | [32] |

| Observing bats utilising swimming pools as water source | USA | [29,30] |

1 Geographic location is limited to a region, due to description of a retroactive assessment of museum specimens from indigenous people located in the Amazon region.

Appendix D

Table A4.

Documented effects of urbanisation on native bats of Florida, USA with citations of literature citations.

Table A4.

Documented effects of urbanisation on native bats of Florida, USA with citations of literature citations.

| Species | Urbanisation Effects | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Eptesicus fuscus |

| [106] |

| [107] | |

| [108] | |

| [109] | |

| [110] | |

| [111] | |

| Eumops floridanus |

| [112] |

| [107] | |

| Lasiurus borealis |

| [106] |

| [107] | |

| [113] | |

| [110] | |

| [114] | |

| [115] | |

| [116] | |

| [117] | |

| Lasiurus cinereus |

| [106] |

| [107] | |

| [108] | |

| [110] | |

| [116] | |

| [111] | |

| Lasiurus intermedius |

| [118] |

| Molossus molossus |

| [119] |

| [120] | |

| Nycticeius humeralis |

| [109] |

| [116] | |

| [114] | |

| Perimyotis subflavus |

| [106] |

| [108] | |

| [110] | |

| [114] | |

| [115] | |

| [118] | |

| Tadarida brasiliensis |

| [112] |

| [52] | |

| [121] |

Appendix E

Table A5.

Foraging habitat, associated physical characteristics, and native Florida species found utilising this space.

Table A5.

Foraging habitat, associated physical characteristics, and native Florida species found utilising this space.

| Foraging Habitat | Characteristics | Species Included |

|---|---|---|

| Open-space | Fast, energetically inexpensive flight type High wing-loading and aspect ratio (narrow long wings) Long, narrowband, and low-frequency calls Pointed wing tips | Eptesicus fuscus Eumops floridanus Lasiurus borealis Lasiurus cinerus Molossus molossus Tadarida brasiliensis |

| Edge | Slow, energetically inexpensive flight type Average wing loading and aspect ratio Echolocate through short pulses with both broad and narrowband components Rounded wing tips | Eptesicus fuscus Lasiurus intermedius Lasiurus seminolus |

| Closed-space | Low wing loading and aspect ratio Energetically expensive but very manoeuvrable Low-intensity, broadband calls Very rounded wing tips | Corynorhinus rafinesquii Lasiurus borealis Lasiurus seminolus Myotis austroriparius Nycticeius humeralis Perimyotis subflavus |

Foraging habitat groupings were made through data accumulated from [122,123].

Table A6.

Structures associated with roosting for native bats in Florida, USA.

Table A6.

Structures associated with roosting for native bats in Florida, USA.

| Scientific Name | Human Structure | Bat House | Caves | Tree Cavity | Foliage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eumops floridanus | x | x | x | ||

| Molossus molossus | x | x | |||

| Tadarida brasiliensis | x | x | x | ||

| Corynorhinus rafinesquii | x | x | x | x | |

| Eptesicus fuscus | x | x | x | ||

| Lasiurus borealis | x | ||||

| Lasiurus cinereus | x | ||||

| Lasiurus intermedius | x | ||||

| Lasiurus seminolus | x | ||||

| Myotis austroriparius | x | x | x | x | |

| Myotis grisescens | x | ||||

| Nycticeius humeralis | x | x | x | ||

| Perimyotis subflavus | x | x | x | x |

Information sourced from [6,124]. x indicates a positive association.

Table A7.

Roosting community structure for native bats in Florida, USA.

Table A7.

Roosting community structure for native bats in Florida, USA.

| Roosting Community Structure | Bat Included |

|---|---|

| Colonial | Corynorhinus rafinesquii * Eptesicus fuscus Eumops floridanus Lasiurus intermedius Molossus molossus Myotis austroriparius Myotis grisescens Nycticeius humeralis Tadarida brasiliensis |

| Solitary | Lasiurus borealis Lasiurus cinereus Lasiurus seminolus |

| Colonial/Solitary | Perimyotis subflavus |

* will roost in pairs or small groups. Information sourced from [6,124].

References

- Ducummon, S.L. Bat Conservation International Incorporation (BCI). Ecological and Economic Importance of Bats. 2000. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/financial/values/g-ecobats.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Riccucci, M.; Lanza, B. Bats and insect pest control: A review. Vespertillio 2014, 17, 161–169. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marco-Riccucci-2/publication/328133405_Bats_and_insect_pest_control_a_review/links/5bba24ba299bf1049b748168/Bats-and-insect-pest-control-a-review.pdf. (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Chen, F.; Zhu, M.; Yuan, L. Urban planning in response to sea level rise and future urbanization in southern Florida. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Green Energy and Applications (ICGEA), Singapore, 4–6 March 2022; pp. 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildlife 2060: What’s at Stake for Florida? Available online: https://myfwc.com/media/5478/fwc2060.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Field Guide to Florida Bats. Available online: https://myfwc.com/conservation/you-conserve/wildlife/bats/field-guide/ (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Loeb, S.C.; Rodhouse, T.J.; Ellison, L.E.; Lausen, C.L.; Reichard, J.D.; Irvine, K.M.; Ingersoll, T.E.; Coleman, J.T.H.; Thogmartin, W.E.; Sauer, J.R.; et al. A Plan for the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat). 2015. Available online: https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr_srs208.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Frick, W.F.; Kingston, T.; Flanders, J. A review of the major threats and challenges to global bat conservation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1469, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, C.L.; Collen, A.; Lucas, T.; Mroz, K.; Sayer, C.A.; Jones, K.E. Challenges of Using Bioacoustics to Globally Monitor Bats. In Bat Evolution, Ecology, and Conservation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, K.E.; Briggs, P.A.; Haysom, K.A.; Hutson, A.M.; Lechiara, N.L.; Racey, P.A.; Walsh, A.L.; Langton, S.D. Citizen science reveals trends in bat populations: The National Bat Monitoring Programme in Great Britain. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 182, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greving, H.; Bruckermann, T.; Schumann, A.; Straka, T.; Lewanzik, D.; Voigt-Heucke, S.; Marggraf, L.; Lorenz, J.; Brandt, M.; Voigt, C.; et al. Improving attitudes and knowledge in a citizen science project about urban bat ecology. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonne, C.; Alstrup, A.K.O. Using citizen science to speed up plastic collection and mapping of urban noise: Lessons learned from Denmark. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, e110591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida Bat Working Group: Citizen Science. Available online: https://www.flbwg.net/citizen-science.html (accessed on 25 April 2024).