Abstract

The Pantanal, considered the world’s largest tropical wetland, is increasingly threatened by intensifying droughts driven by climate variability and climate change. Using Multi-Source Weather data (MSWX), and bias-corrected multi-model means from five Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) simulations for the years 1980–2100, we assessed historical and future drought conditions under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios for the Pantanal. Drought conditions were identified through the Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI) and the Standardised Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) across multiple timescales, and with different reference periods. A historical analysis revealed a significant drying trend, culminating in the extreme droughts of 2019/2020 and 2023/24. Future projections indicate a dual pressure of declining precipitation and rising temperatures, intensifying the severity of dry conditions. By the late 21st century, SSP5-8.5 shows persistent, severe multi-year droughts, while SSP2-4.5 projects more variable but still intensifying dry spells. The SPEI highlights stronger drying than the SPI, underscoring the growing role of evaporative demand, which was confirmed through risk ratios for drought occurrence across temperature anomaly bins. These results offer multi-scalar insights into drought dynamics across the Pantanal wetland, with critical implications for biodiversity, water resources, and wildfire risk. Thus, they emphasise the urgency of adaptive management strategies to preserve ecosystem integrity under a warmer, drier future climate.

1. Introduction

Drought represents one of the most devastating natural hazards globally. The complex interplay between meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and socioeconomic drought creates cascading impacts that can fundamentally alter ecosystem functioning, compromise water security, and threaten food production systems [1,2]. Drought develops slowly and persists for extended periods, but flash droughts can also occur, making this phenomenon a challenge to monitor and predict [3,4]. This is of particular concern under future scenarios of anthropogenic climate change, when the frequency, intensity, and duration of drought events are projected to increase substantially across many regions, with particularly severe implications for tropical and subtropical ecosystems [5,6].

The ecological functionality of wetlands depends fundamentally on specific hydrological regimes [7]. Droughts can force wetland ecosystems into altered functional states [8]. In the Pantanal, drought-induced disruptions to the hydrological cycle have profound ecological consequences: prolonged water deficits lower the groundwater table and delay or suppress the seasonal flood pulse, thereby disturbing the natural flood–dry rhythm that is essential for sustaining the region’s biodiversity. The reduction in both the extent and duration of inundation limits habitat availability for aquatic and semi-aquatic species, disrupts nutrient cycling, and accelerates the transformation of wetland areas into dry savannas [9,10,11,12]. These shifts also impact greenhouse gas emission/sequestration [13] and susceptibility to fire [14], thereby amplifying ecosystem degradation and threatening the socioecological resilience of the Pantanal [15]. Many physical and chemical changes occurring during droughts lead to severe, and sometimes irreversible, drying of wetland soils, making them highly vulnerable to the impacts of drought [16].

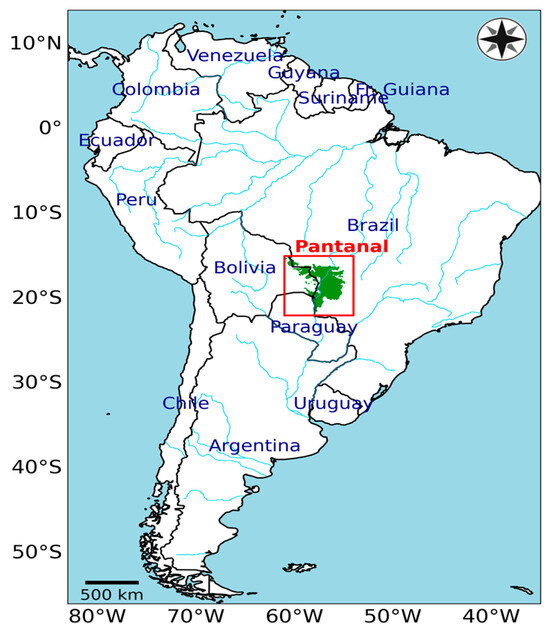

The Pantanal (Figure 1) is the world’s largest tropical wetland, spanning parts of Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay, and stands as one of the planet’s most significant biodiversity hotspots [17]. The Pantanal’s ecological functioning is governed by a marked seasonal flood pulse, with inundation during the wet season and subsequent drainage during the dry season, creating a dynamic mosaic of aquatic and terrestrial habitats [18,19]. A long-term (1926–2016) analysis of consecutive rainy days over the Pantanal based on observational data demonstrated a positive trend [20]. However, in recent years, the Pantanal has been affected by severe drought conditions [21]. The 2019–2020 drought was extreme on record, characterised by decreased moisture flow from the Amazon, high temperatures of 6 °C above normal, reduced rainfall, and water levels in the Paraguay River reaching their lowest point in 50 years [11,22]. This extreme event triggered catastrophic wildfires that consumed over 4 million hectares—approximately 23% of the Brazilian Pantanal—causing unprecedented wildlife mortality and habitat destruction [23,24]. The drought–fire nexus has emerged as a critical threat for the Pantanal, as reduced soil moisture and lower water tables create conditions that are conducive to fire spread.

Figure 1.

Geographical location and extension of the Pantanal wetland (green area) in South America. Region mask downloaded from https://www.oneearth.org/announcing-the-release-of-ecoregion-snapshots/, (accessed on 20 August 2025).

Drought patterns in the Pantanal exhibit significant interdecadal variability linked to large-scale oceanic–atmospheric teleconnections [12]. Thielen et al. [25] demonstrated that sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans explain up to 80% of precipitation variability in the region, with El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) playing crucial roles. The reduced precipitation, runoff, and wetland shrinkage observed in 2001–2021 resembled the previous dry period (1965–1975), confirming a decadal climatic variability [12]. Overall, existing evidence agrees that the Pantanal is experiencing a decline in water levels and more severe drought seasons than in the past. These changes could lead to biodiversity loss and decline of ecosystem services, both of which are intrinsically linked to the flood pulse [10].

Future projections of drought conditions in the Pantanal present alarming scenarios under continued greenhouse gas emissions. Marengo et al. [26] found that higher temperatures and reduced rainfall would likely increase the water deficit in the Pantanal, particularly in the central and eastern parts during spring and summer. However, these authors argue that although projections from Eta-HadGEM2 ES align with those of CMIP5 models for the same scenario, hydrological changes in the Pantanal remain uncertain, as some models predict increased rainfall and discharge, while others suggest increased rainfall, given uncertainties. The findings of Silva et al. [21] reveal that ETA model outputs and CORDEX simulations under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios also present uncertainties, but they agree that extreme droughts affecting the Pantanal will become more frequent towards the end of the century, with the Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI) [27] being more effective for detecting short-term droughts and the Standardised Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) [28] being more suitable for long-term assessments. Despite these important contributions, significant knowledge gaps remain in our understanding of future drought dynamics in the Pantanal. Previous studies have primarily relied on older climate model generations (CMIP3/CMIP5), potentially missing crucial local-scale processes that govern wetland hydrology. Moreover, most assessments have focused on single drought indices or limited time scales, failing to capture the multi-scalar nature of the impacts of droughts on wetland ecosystems. The recent availability of CMIP6 models considering Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), with improved representation of climate processes and higher spatial resolution through downscaling initiatives, such as NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 [29], provides an opportunity to reassess drought projections with enhanced accuracy and detail.

The complex nature of drought requires advanced characterisation approaches that extend beyond simple precipitation deficits, particularly considering the impacts of global warming and climate change. While traditional indices such as the SPI have offered valuable insights into meteorological drought, incorporating temperature-driven evapotranspiration through indices like the SPEI has become increasingly important in a warming world. This study aims to use both indices to explore historical (1980–2024) and probable future (2026–2100) drought conditions in the Pantanal, employing bias-corrected modelling data from the CMIP6 experiment, under two Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5). By providing comprehensive, high-resolution, and multi-scalar drought projection, the results will allow us to assess the implications for ecosystem conservation and water resource management, favouring planning strategies for preserving the ecological integrity of the Pantanal in an increasingly variable future climate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

To perform this study, we had no access to complete long-term records from stations located at the biome’s boundaries, and the only available automatic series at Nhumirim (https://bdmep.inmet.gov.br/, accessed on 27 August 2025) contained more than 50% missing values between 2006 and 2023. Given these limitations, we considered that characterising drought occurrence and a carry on a regional bias correction based on such incomplete data would not be appropriate. Instead, we relied on MSWX-PAST data [30] to obtain monthly values of total precipitation (Tp), mean values of 10 m air temperature (Tas), and maximum and minimum temperatures (Tmax, Tmin) with a resolution of 0.1° for the 1980–2024 period. MSWX-Past is derived from bias-correcting the ERA5 reanalysis (hourly with a horizontal resolution of 0.28° [31]) using the monthly 0.1° reference climatologies. ERA5 integrates diverse observations from surface stations, radiosondes, aircraft, ships, and satellites into the ECMWF Integrated Forecasting System using 4D-Var data assimilation, offering a reliable representation of climate variability and hydrological processes at a global scale, but particularly for South America [32] and the Pantanal [33].

Climate model data of Tp, Tas, Tmax, and Tmin from 5 climate models (Table 1) were utilised to assess probable dry conditions affecting the Pantanal. These outputs belong to the NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset [29], which comprises global downscaled climate scenarios derived from General Circulation Model (GCM) runs conducted under the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) and across all Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). These datasets are freely available at https://www.nccs.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 21 August 2025). Given the inherent uncertainty in climate modelling, a multi-model mean (MMM) was employed, comprising the models used in this study. By using the same ensemble member (r1i1p1f1, version 2.0) for all models, we avoided inconsistencies associated with differing initial conditions, thus enhancing the robustness of the ensemble average. In addition, the five selected models are from different leading modelling centres from different regions, thereby capturing a diversity of modelling strategies and reducing the risk of structural bias. Additionally, these models have been extensively evaluated in the literature and are included in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/, accessed on 21 August 2025) as part of the core set of CMIP6 simulations.

In this study, bias correction was applied directly to the MMM data. Although this ensures consistency in the MMM, it also smooths out part of the inter-model variability and limits the representation of individual model characteristics and the full spread of projections, which would be better preserved by correcting each model variable separately. Nevertheless, this choice is consistent with recent studies that adopted a similar procedure [34,35]. Moreover, Golian and Murphy [36] demonstrated that bias-correcting the MMM (MMM_BC) provides superior skill in reproducing extreme precipitation conditions, whereas correcting individual model outputs before averaging performs better for more frequent precipitation values. Given that our primary focus lies in the assessment of drought conditions in the Pantanal, we prioritised a methodology that enhances the reliability of extremes rather than the full representation of inter-model variability. Both approaches, however, have complementary strengths, and future work should consider hybrid or model-wise bias correction strategies to capture better both extremes and the spread of inter-model projections.

Table 1.

List, origin and characteristics of the five CMIP6 models used in this study. The resolution column refers to the horizontal resolution (°) at the number of vertical levels.

Table 1.

List, origin and characteristics of the five CMIP6 models used in this study. The resolution column refers to the horizontal resolution (°) at the number of vertical levels.

| Model | Institution | Reference | Resolution | Coupling Time Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CanESM5 | CCCma 1 | [37] | Atmosphere: ~2.8°/49 levels Ocean: ~1°/45 levels | 3 h |

| EC-Earth3 | EC-Earth-Consortium 2 | [38] | Atmosphere: ~0.9°/91 levels Ocean: ~1°/75 levels | 45 min |

| GFDL-ESM4 | NOAA-GFDL 3 | [39] | Atmosphere: ~1°/49 levels Ocean: ~0.5°/75 levels | 2 h |

| MPI-ESM1-2-HR | MPI-M 4 | [40] | Atmosphere: ~0.93°/95 levels Ocean: ~0.4°/40 levels | 1 h |

| NorESM2-MM | NCC 5 | [41] | Atmosphere: ~1°/32 levels Ocean: ~1°/53 levels | 30 min |

1 Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis, Victoria, BC, Canada. 2 AEMET, Spain; BSC, Spain; CNR-ISAC, Italy; FMI, Finland; KNMI, The Netherlands; Met Eireann, Ireland; SMHI, Sweden. 3 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, Princeton, USA. 4 Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany. 5 Norwegian Climate Centre and University of Bergen, Norway.

The quantile mapping (QM) approach [42] is used to bias-correct the MMM series of each variable. This method corrects each quantile of the modelled distribution to match the corresponding quantile of the reference dataset, thereby preserving the full distributional characteristics, including variability and extremes. Bias correction parameters were calibrated using the historical period, 1980–2014, with MSWX data as the reference. The calibrated correction function was then applied to future projections (2015–2100). The QM method is particularly suitable for precipitation-based indices, such as the SPI/SPEI, as it preserves the statistical distribution and accurately represents extreme events and has been used for similar purposes in previous studies [43,44]. The SPI/SPEI experiments were done respecting three reference periods (1980–2014, 1980–2100 and 2041–2100) to enable the assessment of how drought severity and frequency shift when viewed against past, present, and projected “normal” conditions.

2.2. Methodology

To determine historical and modelled dry conditions in the Pantanal, the Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI) [27] and the Standardised Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) [28] were calculated and examined. Trends and Pearson correlations (r-values) were assessed using linear least-squares regression. Their statistical significance was determined utilising the Wald test, with p-values derived from a two-sided t-distribution tested against the null hypothesis that the slope equals zero, and evaluated at the 99% confidence level (p-value < 0.01) [45]. Furthermore, the kernel density estimation for approximating the empirical probability density function (PDF) should be used to examine the changes in the SPEI and SPI for both scenarios in the future. Therefore, the bandwidth selection was carried out by a rule of thumb, using Scott’s rule [46] by default.

We used both the SPI [27] and SPEI [28] to assess past and expected dry conditions. Unlike traditional measures that rely solely on precipitation, the SPEI incorporates potential evapotranspiration (PET), making it a more comprehensive indicator of the effects of the hydrological cycle [28], particularly in tropical wetlands such as the Pantanal Biome. The SPEI’s multi-scale characteristics allow for the evaluation of various types of droughts, ranging from soil moisture anomalies at shorter time scales to meteorological and hydrological droughts at longer time scales. To calculate the SPEI at different scales, the difference D = Tp − PET is summed for the desired scale (period). The modified Hargreaves method [47] is used to determine PET, following Equation (1):

where Ra is the monthly extraterrestrial radiation per day in [MJ m−2 d−1], obtained for a fixed latitude of 18.5° S; Tasavg is the average daily temperature in [°C], calculated as the average of the monthly mean, daily maximum, and minimum temperatures. ΔTas is their temperature difference in °C, and Tp is the monthly total precipitation in mm month−1. Evaporation, in mm month−1, is obtained by multiplying the radiation by 0.408.

While the FAO-56 Penman–Monteith formulation is the reference approach for estimating PET, its application requires several datasets, like winds, which are often highly uncertain in long-term climate CMIP6 model simulations [48]. In contrast, modified Hargreaves only requires temperature, precipitation, and extraterrestrial radiation, which are consistently available and reliably simulated. McMahon et al. [49] demonstrated that this method provides reasonable and robust estimates of PET across a wide range of climates, captures the interannual variability of PET reasonably well, with moderate biases relative to Penman–Monteith, making it suitable for tropical regions.

The SPI was calculated using standard procedures by fitting a gamma distribution to the Tp. For the SPEI, a probability distribution (typically log-logistic) of D was fitted using unbiased probability-weighted moments for each grid point, with Tp and PET being expressed in mm month−1. The indices are standardised over a reference period, resulting in a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 during this timeframe. We used the reference periods of 1980–2014, 1980–2100, and 2041–2100 to assess dry spells in relation to the past, overall long-time, and future climate conditions, respectively. The 1980–2014 period represents the experienced climate baseline, 1980–2100 captures the full temporal context of the simulations, and 2041–2100 provides a future baseline for adaptation-oriented analysis. Using multiple reference periods allows a more nuanced interpretation of drought severity and frequency relative to both historical and projected climates, improving the robustness of impact and adaptation assessments. Consequently, positive values indicate wetter conditions, while negative values denote drier conditions. The SPI/SPEI values can be interpreted as follows: magnitudes greater (lower) than 0.84 (−0.84) indicate wet (dry) conditions, values greater (lower) than 1.28 (−1.28) suggest severe wet (dry) conditions, and magnitudes exceeding (less than) 1.65 (−1.65) are considered indicative of extreme wet (dry) conditions [50].

We assessed how the drought risk scales with warming using a thermal–counterfactual (CF) approach, following established practices in event attribution [51,52]. The years from 2026 to 2100 were grouped into four bins according to the annual mean temperature anomaly (ΔT) relative to 1980–2014: 0.5–1.5 °C (the counterfactual reference), 1.5–2.5 °C, 2.5–3.5 °C, and ≥3.5 °C. For each year, the hydrological year (October–September) minimum of SPI3 and SPEI3 was calculated, and an event was defined when this minimum was ≤τ, with τ ∈ {−0.84, −1.28, −1.65}. Within each ΔT bin (b), containing Nb years and Kb events, the probability of drought occurrence in bin b, denoted as pb, was estimated with a continuity correction to avoid zero probabilities or unity probabilities in finite samples, following Equation (2).

The uncertainty of pb was quantified using two-sided 95% binomial confidence intervals derived from the exact Clopper–Pearson method [53]. The risk ratio (RRb) compares the likelihood of drought in bin b relative to the counterfactual bin (CF). Specifically, pb represents the estimated probability of a drought event in warming bin b, while pCF represents the probability of a drought event in the counterfactual bin. The risk ratio RRb was then computed as follows:

Sampling uncertainty and interannual autocorrelation were addressed by applying a circular block bootstrap [54,55] with a block length of five years and 3000 replications, conducted independently for the counterfactual (CF) and each warming bin. We selected the 0.5–1.5 °C bin as the counterfactual bin because it reflects present-day warming (~1 °C above 1980–2014), offers adequate sampling coverage over the period of 2026–2100, and has sufficient width to stabilise probability estimates without blending with markedly warmer regimes. This framework renders the temperature effect explicit, facilitating the direct interpretation of risk ratios and their confidence intervals.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Historical Drought Assessment

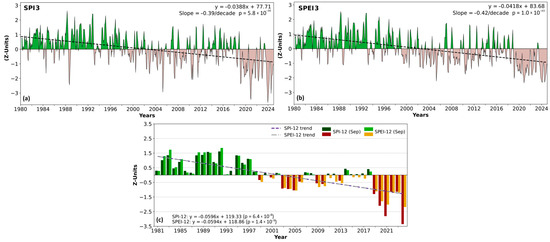

The combined analysis of the SPI3 and SPEI3 time series (Figure 2a,b) reveals a statistically significant (p-value < 0.01) trend towards drier conditions in the Pantanal since 1980, with negative slopes ranging from −0.39 to −0.42 units per decade. This pattern is consistent with previous research highlighting an intensification of aridity in the region, driven by changes in rainfall regimes and increased potential evapotranspiration demand in the context of rising mean temperatures and multi-scale climate variability [26,56]. The visual analysis reveals that, according to both indices, from 1980 to approximately the end of the 1990s, wet episodes predominated, but short dry periods can also be observed. However, from the early 2000s onwards, there has been an increase in the frequency, magnitude, and persistence of dry conditions, culminating in the drought beginning in 2019–2020, which has been documented as one of the most severe of the past four decades, with unprecedented hydrological, ecological, and socioeconomic impacts in the Pantanal wetland [22].

Figure 2.

Monthly series of the SPI3 (a) and SPEI3 (b) from the MSWX data, revealing wet (green) and dry (brown) conditions. The SPI12 and SPEI12 for September, showing interannual differences (c). Linear trends and p-values. Period of 1980–2024.

While extreme events such as the 2004–2005, 2019–2020, and 2023–2024 droughts strongly accentuate the negative trends in the SPI3 and SPEI3, the statistical significance of the long-term linear trends (p-value < 0.01) indicates that the signal is not solely driven by a few isolated episodes. Instead, the record reveals a cumulative shift toward drier conditions, with multiple dry episodes occurring in the last two decades. Nevertheless, single intense droughts act as inflection points that steepen the regression slope and highlight the vulnerability of the Pantanal system. This interplay between systematic drying and punctuated extremes reinforces the view that both gradual and episodic processes contribute to the observed negative trends.

The evolution of the SPI12 and SPEI12 for September (Figure 2c), the last month of the hydrological year, is also consistent with the three-month temporal scale of these indices. In addition, it reveals that the observed drought conditions from 2019 to 2024 were the most severe of the entire period, highlighting 2018/19, 2019/20, 2020/21, and 2023/24 due to the high severity of the SPI. This suggests that the balance of precipitation minus evapotranspiration tends to modulate dry conditions towards less severe conditions, as stated by Marengo et al. [11] in relation to the 2019/2020 drought.

Large-scale synoptic patterns and regional atmospheric mechanisms play a crucial role in moisture transport, precipitation, and evapotranspiration in South America [57,58]. Particularly important is the influence of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on the hydroclimate variability of South America [59]. A recent study revealed that under the influence of La Niña conditions, the number of days per year with concurring warm, dry, and flammable conditions increased in the regions of the Gran Chaco, which comprise the Pantanal [60]. However, previous findings have found no significant correlations between precipitation over the Pantanal and the signal of El Niño [12]. Indeed, as appreciated in Figure 2, some drought periods have occurred during both El Niño (e.g., 2003, 2010) and La Niña (e.g., 1999, 2021, 2022) years, highlighting the complexity of the ENSO influence over the Pantanal.

3.2. Climate Modelling Assessment

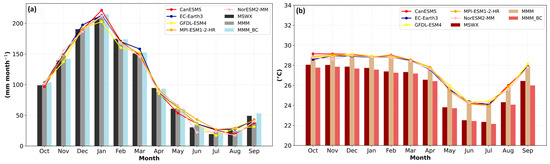

The annual cycle of precipitation and mean temperature for the Pantanal, represented by MSWX, each climate model, the MMM, and the bias-corrected MMM, hereafter labelled as MMM_BC, is shown in Figure 3. Precipitation increases across all datasets from October, peaking in January, then decreases, indicating a clear dry season during the Southern Hemisphere winter, with the lowest precipitation values being observed in July for all datasets (Figure 3a). This pattern is typical for tropical regions, influenced by the shifting of atmospheric circulation patterns and thermodynamic conditions [61]. The representation and magnitude of the annual precipitation cycle, especially during the rainiest (January) and driest (July) months, align with observational datasets used by Silva et al. [21] across several locations in the Pantanal, confirming the reliability of all datasets employed in this study.

Figure 3.

Annual cycle of precipitation (Tp, mm month−1) (a) and mean air temperature (Tas, °C) (b), from the five models listed in Table 1 (lines), MSWX, MMM, and MMM_BC (bars). Period of 1980–2014.

Notably, the bias correction substantially improved the representation of Tp by the MMM when compared with the MSWX reference dataset. The corrected seasonal cycle closely follows the observed monthly means, with a particularly large reduction in negative bias observed for September. In addition, the quantile–quantile (QQ) plot (Figure S1) shows that the distribution of corrected precipitation aligns much more closely with the 1:1 line, indicating a better match of both central tendencies and extremes. This also demonstrates that the method effectively adjusted the mean, variance, and tails of the distribution, enhancing the MMM_BC’s ability to reproduce observed precipitation characteristics. Similarly, temperature correction proves to be effective (Figure 3b). However, the temporal correlation between Tp from MSWX and the MMM of 0.86 decreases to 0.77 when the assessment is made with the MMM_BC (Figure S2a). This is also observed for the correlation values obtained for each model time series of Tp and mean Tas (Figure S2) and MSWX, although all r-values are positive, greater than or equal to 0.82 for Tp and 0.85 for Tas, and statistically significant (p-value < 0.01). In addition, the correlations for the Tp time series (Figure S2a) are slightly higher than those for the Tas time series (Figure S2b), except for MSWX and MMM_BC. Although the temporal correlation decreased slightly after bias correction, this did not affect the subsequent SPI/SPEI computations. Quantile mapping enhances the representation of precipitation’s statistical distribution, including mean, variance, and extremes [62], which is the primary requirement for robust SPI/SPEI estimation.

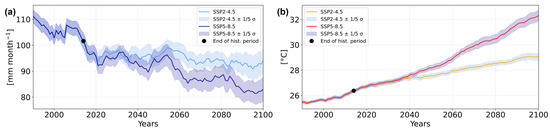

Precipitation is projected to decrease by more than 15 mm month−1 under the SSP2-4.5 scenario and by more than 25 mm month−1 under the SSP5-8.5 scenario from 1980 to 2100. This would result in annual Tp means of approximately 85 (95) mm month−1 under SSP5-8.5 (SSP2-4.5) by the end of the century (Figure 4a). This decrease is accompanied by a rise in near-surface temperature. MMM_BC indicates a Tas increase of over 3 °C under SSP2-4.5 and more than 6 °C under SSP5-8.5 (Figure 4b), reaching mean temperatures of 29 and 32 °C, respectively, by the end of the century. Warming of this magnitude will intensify evapotranspiration and lower water availability [12]. In conjunction with the Tp decrease, this creates a dual pressure on the regional water balance. Such evolutions are in line with an identified drying trend for central South America [63] and indicate potentially large-scale changes in atmospheric moisture transport and convective activity across the Amazon and the Pantanal regions [64]. These changes are expected to affect not only ecological functioning but also fire frequency, groundwater recharge, and river flows [20,65,66].

Figure 4.

Projected evolution of the bias-corrected multi-model mean (MMM_BC) total precipitation (a) and near-surface air temperature (b) for the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. Period: 1980–2100. Time series are smoothed using a 10-year rolling mean, with shaded areas indicating ±1/5σ inter-model variability and black dots marking the end of the historical period. Non-smoothed time series are shown in the Supplementary Material (Figure S3).

The individual trends for Tp and Tas from each model, MMM, and MMM_BC are shown in Table 2. The monthly Tp trends are generally negative under SSP2-4.5; however, two of the five models, namely, CanESM3 and MPI-ESM1-2-HR, show positive trends. In contrast, under SSP5-8.5, the monthly Tp trends are negative for all models, although they remain nearly zero for the two previously mentioned models. Except for CanESM3 and MPI-ESM1-2-HR, all monthly Tp trends are statistically significant for both SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5. Regarding the Tas trends, they are statistically significant and positive across all models in our multi-model ensemble under both future scenarios.

Table 2.

Linear trends of the projected evolution of Tp and Tas for the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 for each climate model series, the MMM, and the MMM_BC. The trend values are expressed per year; asterisks (*) denote statistically significant trends (p-value < 0.01).

A comparison of the expected annual precipitation cycle, representative for the mid-century (2041–2071) and end-century (2071–2100) according to the MMM_BC (Figure S4a,b), confirms that Tp generally decreases in both periods compared with the historical period. The most significant decrease is expected in August, September, and October. For October, the onset of the rainy season, Tp drops from 100 mm month−1 to less than 50 mm month−1 on average during the last 30 years of this century under SSP5-8.5 (Figure S4b). This weakening in the magnitude of Tp could be associated with a shortening of the growing season and, consequently, would affect the timing of river floods, which are vital for the floodplain ecology of the Pantanal [20,67]. Concerning the future annual cycle of the mean near-surface temperature, an increase is expected for every month (Figure S4c,d). The mean Tas is projected to rise more from May to November than during other months in both periods. The greater rise in temperature during these months may be attributed to decreasing soil moisture due to less precipitation, which enhances surface heat absorption and reduces evaporative cooling [68,69]. These changes may increase the likelihood of evapotranspiration-driven droughts, intensifying water stress before the onset of the wet season.

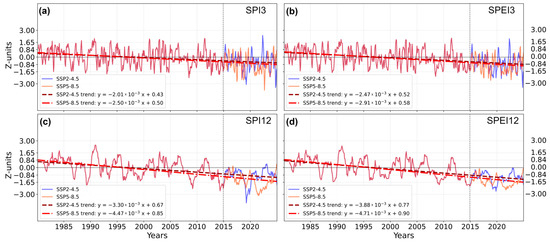

3.2.1. Historical Representation of Drought Conditions by MMM_BC

The reduction in Tp, combined with the rise in Tas, alters the hydrological balance (Tp–PET), thereby modifying the occurrence and persistence of extreme events, such as dry and wet spells. To further assess these dynamics, the modelled SPI and SPEI across the past and future periods are examined. Particularly important is the ability of the drought indices from the MMM_BC data to accurately reproduce the occurrence of dry periods, as previously discussed in Section 3.1. The historical series and associated linear trends of the SPI/SPEI, computed from the MMM_BC at 3-month and 12-month timescales, for the modelling reference period of 1980–2014 are shown in Figure 5. The plots are extended until 2024, but considering the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 individually. This allows us to evaluate the performance of the data in representing the persistent drying of the Pantanal in recent years. All indices display statistically significant negative trends (p-value < 0.01), which is consistent with a progressive shift towards drier conditions. Notably, the SPEI3 and SPEI12 series (Figure 5b,d) show a more pronounced decline than the SPI3 and SPI12, respectively. This reflects the role of increasing temperatures (Figure 4b) in intensifying atmospheric evaporative demand and thereby amplifying the severity of droughts.

Figure 5.

Projected temporal evolution of monthly SPI and SPEI, calculated from the MMM_BC for the reference period of 1980–2014. (a) SPI3, (b) SPEI3, (c) SPI12, and (d) SPEI12 for 1980–2024, with SSP2-4.5 marked in blue and SSP5-8.5 in orange-red from 2015 onwards, along with their linear trends (maroon and red, respectively). Dark red lines indicate the historical period until 2014 of the overlapping values for the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. All linear trends are statistically significant, with a p-value < 0.01; × of trend equations have units [month].

Overall, the SPI and SPEI time series from MMM_BC align well with the SPI and SPEI obtained from the MSWX (Figure 2), yet some discrepancies emerge. The sustained drought signal that is evident in the SPI/SPEI series from MSWX data from the early 2000s onwards is less clearly represented in drought indices calculated with the simulations. Notably, the severe 2019/20 drought captured in the MSWX data is accurately reproduced by SPI12/SPEI12 under the SSP2-4.5 simulations, whereas the SSP5-8.5 simulations exhibit a slight temporal offset (Figure 5c,d). Under SSP2-4.5, the SPI12/SPEI12 values suggest a recovery followed by another dry phase in 2023/24, although this event appears less intense than in the MSWX record.

These findings contrast with findings of Silva et al. [21], who reported that neither the ETA-Ensemble nor the CORDEX-Ensemble was able to capture the 2019/20 extreme under RCP4.5 or RCP8.5 when using SPEI12. Moreover, those ensembles did not represent the extended dry period from 2018/19 to 2023/24. Although SPI12 from the CORDEX-Ensemble indicates variable dry conditions around those years, it does not emphasise either the 2019/20 or 2023/24 events, while the Eta-Ensemble shows a temporal offset. Taken together, this suggests that MMM_BC simulations may provide a more realistic representation of recent drought extremes than previous ensemble-based approaches.

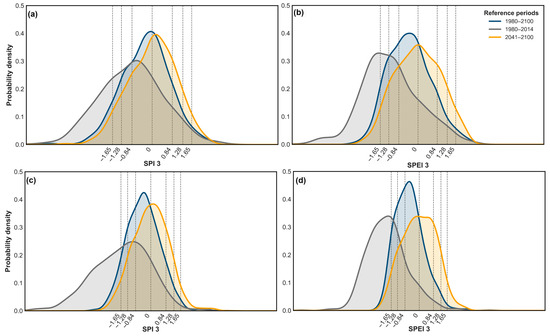

3.2.2. Future Drought Assessment by MMM_BC

The kernel densities of SPI3 and SPEI3 for 2041–2100 (SSP2-4.5; SSP5-8.5) in the Pantanal, using three reference periods (1980–2014, 1980–2100, and 2041–2100; dashed lines mark standard drought thresholds), appear in Figure 6. Against the historical baseline (1980–2014), both indices are shifted to the left in both scenarios, but more drastically for the SSP5-8.5, implying more frequent dry conditions. The larger shift is also observed for the SPEI3, which is consistent with additional drying once PET is considered. Using the complete period (1980–2100) as a baseline visibly damps this displacement, as values are smoothed over the entire model period. Finally, the future baseline (2041–2100) re-centres the curves near zero by construction, effectively classifying droughts within the new climatological regime rather than relative to past conditions. Hence, the interpretation hinges on the baseline: a fixed historical frame is suited for detecting climate-driven drying, whereas a future baseline classifies drought within the future regime.

Figure 6.

Empirical probability density distribution of the SPI3 (a,c) and SPEI3 (b,d) from MMM_BC for the period of 2041–2100 under the SSP2-4.5 (top panels) and SSP5-8.5 (bottom panels), considering the reference baselines: 1980–2100 (blue), 1980–2014 (grey), and 2041–2100 (orange). The vertical dotted lines display moderate, severe and extreme dry and wet thresholds of the SPI/SPEI.

This analysis demonstrates that the choice of reference period can significantly influence drought assessments, even reversing projected change, and should therefore be analysed explicitly, as outlined in previous studies (e.g., [70]). In addition, the contrast between the SPI and SPEI underscores that the choice of PET formulation also affects the conclusions. Physically based PET and a transparent baseline strategy strengthen this study’s robustness. In practical terms, the results point to more frequent and intense dry conditions relative to the late-20th-century climate, with implications for wetland hydrology, navigation and fisheries, biodiversity, wildfire management, and air quality risks. These impacts are likely to be amplified when temperature effects are considered, emphasising the need for integrated drought early-warning and water-allocation strategies that are tailored to a warmer (Figure 4 and Figure S4) and more evaporative Pantanal.

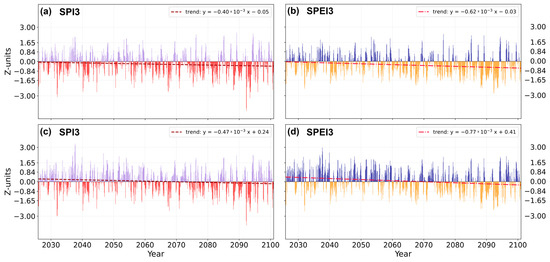

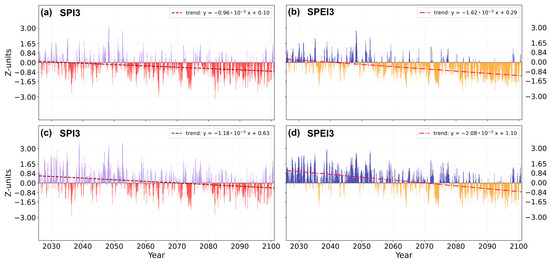

Concerning future drought assessments, the time series and trends of the SPI3/SPEI3 for the reference periods of 1980–2100 and 2041–2100 are presented in Figure 7 (SSP2-4.5) and Figure 8 (SSP5-8.5), spanning from 2026 to 2100. Like the analysis of historical data, a statistically significant negative trend in the SPI3/SPEI3 indicators persists until 2100, which indicates a drier climate with more prolonged and extreme drought events, particularly under the SSP5-8.5 scenario (Figure 8). This shift towards a drier climate may be attributed to the warming of the Northern Hemisphere SST, particularly in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, combined with anthropogenic land cover changes such as deforestation, as explored in previous studies [25,71,72].

Figure 7.

Temporal evolution of monthly SPI3 (a,c) and SPEI3 (b,d) values, with their trends calculated from MMM_BC, 2026–2100 for the SSP2-4.5. (a,b) show results for the reference period of 1980–2100 and (c,d) for the reference period of 2041–2100. Medium purple (dark blue) and red (dark orange) lines represent wetter- and drier-than-normal conditions, respectively, for SPI3 and SPEI3. All linear trends are statistically significant, with a p-value < 0.01; xof trend equations have units [month].

Figure 8.

Temporal evolution of monthly SPI3 (a,c) and SPEI3 (b,d) values, with their trends calculated from MMM_BC, 2026–2100 for the SSP5-8.5. (a,b) show results for the reference period of 1980–2100 and (c,d) for the reference period of 2041–2100. Medium purple (dark blue) and red (dark orange) lines represent wetter- and drier-than-normal conditions, respectively, for SPI3 and SPEI3. All linear trends are statistically significant, with a p-value < 0.01; × of trend equations have units [month].

In the drought analysis based on the 1980–2100 reference period (Figure 7a,b and Figure 8a,b), dry spells significantly outnumber wet spells, particularly in the second half of the century and for the SSP5-8.5 scenario. In this worst-case greenhouse gas emissions scenario, multi-year drought events become prevalent from 2060 onwards, surpassing moderate, severe, and even extreme drought thresholds. This trend suggests an increased frequency of long-lasting extreme droughts, such as the 2019/20 event [21,25]. The implications of these findings are particularly significant for wetland ecosystems, where prolonged water deficits can disrupt essential flood pulse regimes that support biodiversity and ecosystem services [20,25,67]. While SPI3/SPEI3 values under the SSP5-8.5 scenario tend to stabilise around the severe drought threshold of −1.28 toward the end of the study period, the SSP2-4.5 scenario projects a greater occurrence of extreme dry and wet events.

For the SPI3/SPEI3 with a reference period of 2041–2100, stronger negative trends are observed compared with the previous longer reference period (Figure 7c,d and Figure 8c,d). Under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, values shift from predominantly positive to predominantly negative from 2026 to 2100 (Figure 8c,d). In contrast, the SSP2-4.5 scenario is expected to show more variability, with notably stronger individual dry and wet spells. For both reference periods under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, it is anticipated that three extreme droughts will occur around 2090, with the last being the most severe in the early 2090s (Figure 7). However, under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, a long-lasting extreme drought is forecasted for the mid-2070s (Figure 8).

3.2.3. Warming-Linked Changes in Drought Risk

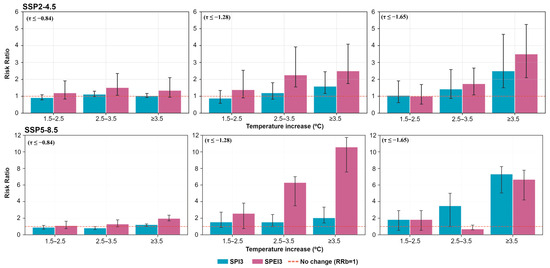

In the final stage of the analysis, we applied a temperature-binned attribution framework, which quantifies how drought risk scales with warming, considering the SPI3 and SPEI3 under the SSP2-4.5 (Figure 9, top panel) and SSP5-8.5 (Figure 9, bottom panel). Under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, droughts defined by the moderate threshold (τ ≤ −0.84) show only modest changes, with RRb being generally between 1.1 and 1.5 and confidence intervals overlapping with each other, suggesting limited warming influence. In contrast, risk amplification is more evident for severe and extreme droughts (τ ≤ −1.28), with RRb rising to ~1.1–1.5 for SPI3 and reaching ~2.2 for SPEI3. The largest increases occur for extreme droughts (τ ≤ −1.65), where RRb approaches ~2.5 for SPI3 and ~3.4 for SPEI3, highlighting the intensification of compound temperature–precipitation stress. Notably, SPEI-based estimates systematically exceed SPI values, underlining the critical role of atmospheric evaporative demand in modulating drought severity under warming. Under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, amplification is far stronger and less linear. Moderate droughts (τ ≤ −0.84) remain close to RRb ≈ 1–2, which is consistent with weak sensitivity. However, severe and extreme droughts (τ ≤ −1.28) show an abrupt rise, reaching ~2.5 for the SPI3 and exceeding 10 in the ≥3.5 °C bin for the SPEI3. For extreme droughts (τ ≤ −1.65), the effect is dramatic, with RRb climbing to ~7.5 for SPI3 and ~7 for SPEI3, implying a greater occurrence probability relative to present-day warming levels. Despite wider bootstrap confidence intervals in the warmest bin, the monotonic escalation across temperature classes indicates a robust signal of risk intensification.

Figure 9.

Risk ratio (RRb) for drought occurrence across temperature anomaly bins (relative to the 0.5–1.5 °C counterfactual) during 2026–2100 under (top row) SSP2-4.5 and (bottom row) SSP5-8.5. Bars represent point estimates for SPI3 (blue) and SPEI3 (magenta), with vertical lines indicating 95% confidence intervals derived from a 5-year circular block bootstrap (3000 replications). The dashed horizontal line denotes RRb = 1, corresponding to no change in risk relative to the counterfactual.

These results are consistent with previous attribution and projection studies across South America. Miranda et al. [56] documented that drought conditions reached their maximum intensity in the 2019–2020 period due to the combination of low soil moisture levels and high surface temperature amplitude, associated with a low Evaporative Fraction, leading to thermal and water stress and affecting the ecosystem’s capacity to recover from environmental disturbances. Other findings have also documented that in climate change projections derived from the Eta-HadGEM2 ES models with a horizontal resolution of 20 km, for the RCP8.5 for 2071–2100, it is expected that there will be an annual mean warming of up to or above 5–7 °C and a 30% reduction in rainfall by the end of the 21st century [26].

3.2.4. Implications of Regional Climate Forcings and Anthropogenic Drivers for the Pantanal Ecosystem Functioning

Our findings reveal a progressive increase in drought probability, in line with recent assessments for the Southern Amazon and Central South America [60], where anthropogenic warming and circulation anomalies have increasingly promoted precipitation deficits and enhanced evaporative demand [73]. The severe 2019–2020 Pantanal drought exemplified the compound nature of these risks; large-scale ocean–atmosphere drivers, including Pacific and Atlantic SST anomalies and a weakened South American Monsoon System (SAMS), coincided with regional-scale land–atmosphere feedbacks, leading to unprecedented hydrological deficits and extreme fire conditions [11,66]. Fire activity during November 2023 was also related to extreme drought driven by the influence of a strong El Niño, causing a record of forest loss in the Pantanal, underscoring the emerging drought–fire nexus [74].

The role of land-use and anthropogenic change is also increasingly critical. Deforestation and pasture expansion in the Pantanal have reduced forest and savanna cover from ~57% in 1985 to ~40% in 2021, while pasture increased to ~34% and soybean from 1 to 4% [12]. These transformations have contributed to reducing evapotranspiration [75], which in turn weakens convective recycling and amplifies surface warming, thereby preconditioning the dry season to intensify. Such mechanisms mirror those reported in the Southern Amazon and the Cerrado, affecting the length of the dry season and interacting non-linearly with greenhouse-gas-driven warming [75,76,77]. Our results, therefore, reinforce the view that climate change and anthropogenic land transformation act jointly rather than independently. The first establishes a warmer, drier baseline (higher temperatures, elevated vapour-pressure deficit, longer dry season), while land-use change amplifies hydroclimatic stress by reducing soil moisture recharge, decreasing runoff efficiency, and increasing landscape flammability. These conditions have far-reaching ecological and socio-economic consequences in the Pantanal, as they disrupt the natural flood–dry cycle that underpins the region’s biodiversity and ecosystem services [78,79]. Previous assessments show that prolonged droughts reduce aquatic habitats, increase tree mortality, alter vegetation structure, and constrain fish and bird reproduction, while also stressing large mammals such as capybaras and marsh deer [80]. Additionally, extreme droughts and floods alter greenhouse gas emissions and sequestration across the Pantanal Biome [13], which can result in a positive feedback effect of enhanced greenhouse gas concentrations. The projections of increased drought frequency and intensity in the Pantanal, therefore, imply not only a hydroclimatic shift but also profound ecological and livelihood impacts in the world’s largest tropical wetland.

4. Conclusions

Convergent evidence from the trends in drought indices in the historical and future projections under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 indicates an ongoing and future transition towards a drier hydroclimate in the Pantanal. The historical SPI and SPEI series indicate persistent drought conditions from the 2018/19 hydrological year, relative to the 1980–2014 period. Projections suggest that continued warming, alongside stable to declining precipitation, will raise the frequency, duration, and severity of droughts across the wetland, with the drying signal being more pronounced when evaporative demand is represented (the SPEI is more negative than the SPI). Scenario and baseline choices materially influence drought classification. When referenced to a fixed historical climate (1980–2014), SPI3/SPEI3 point to a clear shift towards moderate-to-extreme droughts by 2041–2100 under SSP2-4.5 and frequent extreme conditions under SSP5-8.5. Using a future baseline (1980–2100 or 2041–2100) attenuates the apparent drying yet still yields predominantly negative anomalies from 2026 onwards, which are again stronger for the SPEI than the SPI. A temperature-binned attribution analysis shows a progressive amplification of the drought risk in the Pantanal as warming increases, with stronger effects for more severe thresholds and the SPEI, which is consistent with trends and confirms the role of temperature in atmospheric evaporative demand.

These results highlight that assessments based on historical vs. future conditions offer a relevant perspective on emerging risks that have already been observed in the Pantanal. In the context of the Pantanal, these findings imply that an increase in the frequency and severity of drought under intermediate mitigation (SSP2-4.5) is projected to become substantially more common under both scenarios and potentially catastrophic under SSP5-8.5. The implications for the Pantanal’s water resources, wildfire risk, and consequently its biodiversity are both immediate and expected to intensify, highlighting the urgent need for adaptation and mitigation strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded from https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments12110413/s1: Figure S1. Quantile–quantile (QQ) plots comparing annual values of precipitation (Tp), mean air temperature (Tmean), maximum temperature (Tmax), and minimum temperature (Tmin) from the bias-corrected multi-model mean (MMM_BC) against the reference MSWX dataset. The black line denotes the 1:1 relationship, while deviations from the line indicate departures of the multi-model mean (MMM) and MMM_BC distribution from observations. Period: 1980–2014. Figure S2. Pearson correlation matrices of monthly series of (a) total precipitation (Tp) and (b) 10 m air temperature (Tas) averaged over the Pantanal region for the period 1980–2014. The matrices display pairwise correlations among the five climate models (Table 1), the multi-model mean (MMM), the bias-corrected multi-model mean (MMM_BC), and the MSWX reference dataset. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant correlations (p < 0.01). Period: 1980–2014. Figure S3. Unsmoothed monthly projections of (a) total precipitation (Tp) and (b) 10 m air temperature (Tas) from the bias-corrected multi-model mean (MMM_BC) under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios for the period 1980–2100. Shaded areas represent ±(1/5)σ inter-model variability, and black dots indicate the end of the historical period. Figure S4. Mean annual cycles of (a,b) total precipitation (Tp) and (c,d) 10 m air temperature (Tas) from the bias-corrected multi-model mean (MMM_BC) for the Pantanal region. Panels (a,c) correspond to the mid-century period (2041–2070), and panels (b,d) to the end-century period (2071–2100), compared with the historical period (1980–2014). The SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios are shown together with the historical simulations. Error bars represent inter-period standard deviations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: M.S. and R.S.; methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, and writing: all authors; review and editing: J.E. and R.S.; supervision: M.S. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Xunta de Galicia under the project Excelencia-ED431F-2024/0; the grant RYC2021-034044-I funded by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Spain (MICIU/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033); and the European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR.

Data Availability Statement

The data used can be made available by request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

All authors acknowledge the support from the projects Excelencia-ED431F-2024/03 and ED431C2021/44 (Programa de Consolidación e Estructuración de Unidades de Investigación Competitivas (Grupos de Referencia Competitiva) and Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Universidade), both funded by the Xunta de Galicia. M. Stojanovic acknowledges the support from the Xunta de Galicia (Consellería de Cultura, Educación, Formación Profesional e Universidades) under the Postdoctoral Grant No. ED481D − 2024/017. R. Sorí acknowledges the grant RYC2021 − 034044-I, funded by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Spain (MICIU/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033), and the European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR. This work has also been possible thanks to the computing resources provided by CESGA (Centro de Supercomputación de Galicia) and RES (Red Española de Super-computación).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMO | Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation |

| CMIP6 | Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 |

| ENSO | El Niño Southern Oscillation |

| GCM | Global Circulation Model |

| MMM_BC | Bias-corrected multi-model mean |

| MSWX | Multi-Source Weather data |

| MMM | Multi-model mean |

| PDO | Pacific Decadal Oscillation |

| PET | Potential evapotranspiration |

| QM | Quantil mapping |

| RR | Risk ratio |

| SPI | Standardised Precipitation Index |

| SPEI | Standardised Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index |

| SSP | Shared Socioeconomic Pathways |

| Tas | Air temperature |

| Tp | Total precipitation |

References

- Wilhite, D.A.; Sivakumar, M.V.K.; Pulvarty, R. Managing drought risk in a changing climate: The role of national drought policy. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2014, 3, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, A.F. Hydrological drought explained. WIREs Water 2015, 2, 359–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeparvathy, V.; Debdut, S.; Mishra, A. A review of advances in flash drought research: Challenges and future directions. Earth’s Futur. 2025, 13, e2025EF006603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.I.; Mankin, J.S.; Marvel, K.; Williams, A.P.; Smerdon, J.E.; Anchukaitis, K.J. Twenty-first century drought projections in the CMIP6 forcing scenarios. Earth’s Futur. 2020, 8, e2019EF001461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, B.; Liang, X.; Cui, L.; Li, H.; Qu, Y.; Luo, C. Hydrological dynamics and its impact on wetland ecological functions in the Sanjiang Plain, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P.; Moore, J.N.; Kimball, J.S.; Jencso, K.; Petrie, M.; Naugle, D.E. Going, going, gone: Landscape drying reduces wetland function across the American West. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alho, C.J.R.; Mamede, S.B.; Benites, M.; Andrade, B.S.; Sepúlveda, J.J.O. Threats to the Biodiversity of the Brazilian Pantanal Due to Land Use and Occupation. Ambient. Soc. 2019, 22, e01891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, W.L.; Oliveira-Júnior, E.S.; da Silva, C.J.; Castrillon, S.K.I.; Muniz, C.C. Climate change reflected in one of the largest wetlands in the world: An overview of the Northern Pantanal water regime. Acta Limnol. Bras. 2020, 32, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Cunha, A.P.; Cuartas, L.A.; Deusdará Leal, K.R.; Broedel, E.; Seluchi, M.E.; Michelin, C.M.; De Praga Baião, C.F.; Chuchón Angulo, E.; Almeida, E.K.; et al. Extreme Drought in the Brazilian Pantanal in 2019–2020: Characterization, Causes, and Impacts. Front. Water 2021, 3, 639204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, C.B.; Biggs, T.W.; Vergopolan, N.; Camelo, L.G.G.; Comini de Andrade, B.; Laipelt, L.; Ruhoff, A.L. Decadal hydroclimatic changes in the Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetland. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrinetti, T.A.; Cotta, S.R.; Feitosa, Y.B.; Melo, P.L.A.; Bieluczyk, W.; Silva, A.M.M.; Mendes, L.W.; Sarmento, H.; Camargo, P.B.; Tsai, S.M.; et al. The role of microbial communities in biogeochemical cycles and greenhouse gas emissions within tropical soda lakes. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 947, 174646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinck, C.N.; Lima, L.H.A.; Pereira, A.M.M.; Carvalho, E.A.R., Jr.; Paula, R.C.; Thomas, W.M.; Morato, R.G. The Pantanal is on fire and only a sustainable agenda can save the largest wetland in the world. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, e244200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchiano, M.; Ikeda Castrillon, S.K.; de Figueiredo, D.M.; Xavier, F.; Daher, F.; Lenzi, Í.; Silgueiro, V.; Spanholi, M.; Nunes, J.; da Silva, C.J. Climate emergency: A proposal for a socio-participatory conservation unit for water restoration in the Pantanal. In Proceedings of the Conference: 1st Seven Global Congress of Multidisciplinary Studies, Online, 4 September 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, E.; Fitzpatrick, R.W.; Mosley, L.M. Drought effects on wet soils in inland wetlands and peatlands. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 210, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.J.; da Cunha, C.N.; Wantzen, K.M.; Petermann, P.; Strüssmann, C.; Marques, M.I.; Adis, J. Biodiversity and its conservation in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Aquat. Sci. 2006, 68, 278–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.K.; Sippel, S.J.; Melack, J.M. Inundation patterns in the Pantanal wetland of South America determined from passive microwave remote sensing. Arch. Hydrobiol. 1996, 137, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alho, C.J.R. Biodiversity of the Pantanal: Response to seasonal flooding regime and to environmental degradation. Braz. J. Biol. 2008, 68, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergier, I.; Assine, M.L.; McGlue, M.M.; Alho, C.J.R.; Silva, A.; Guerreiro, R.L.; Carvalho, J.C. Amazon rainforest modulation of water security in the Pantanal wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.O.; de Mello, C.R.; Chou, S.C.; Guo, L.; Viola, M.R. Characteristics of extreme meteorological droughts over the Brazilian Pantanal throughout the 21st century. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1385077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libonati, R.; Geirinhas, J.L.; Silva, P.S.; Russo, A.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Belém, L.B.C.; Nogueira, J.; Roque, F.O.; DaCamara, C.C.; Nunes, A.M.B. Assessing the role of compound drought and heatwave events on unprecedented 2020 wildfires in the Pantanal. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libonati, R.; DaCamara, C.C.; Peres, L.F.; Sander de Carvalho, L.A.; Garcia, L.C. Rescue Brazil’s burning Pantanal wetlands. Nature 2020, 588, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto Garcia, L.; Szabo, J.K.; de Oliveira Roque, F.; de Matos Martins Pereira, A.; Nunes da Cunha, C.; Alves Damasceno-Júnior, G.; Gonçalves Morato, R.; Moraes Tomas, W.; Libonati, R.; Bandini Ribeiro, D. Record-breaking wildfires in the world’s largest continuous tropical wetland: Integrative fire management is urgently needed for both biodiversity and humans. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielen, D.; Ramoni-Perazzi, P.; Puche, M.L.; Márquez, M.; Quintero, J.I.; Rojas, W.; Soto-Werschitz, A.; Thielen, K.; Nunes, A.; Libonati, R. The Pantanal under Siege—On the Origin, Dynamics and Forecast of the Megadrought Severely Affecting the Largest Wetland in the World. Water 2021, 13, 3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Alves, L.M.; Torres, R.R. Regional climate change scenarios in the Brazilian Pantanal watershed. Clim. Res. 2016, 68, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, T.B.; Desken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Applied Climatology, Boston, MA, USA, 17–22 January 1993; pp. 179–184. Available online: https://climate.colostate.edu/pdfs/relationshipofdroughtfrequency.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Climate 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, B.; Wang, W.; Michaelis, A.; Melton, F.; Lee, T.; Nemani, R. NASA Global Daily Downscaled Projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Larraondo, P.R.; McVicar, T.R.; Pan, M.; Dutra, E.; Miralles, D.G. MSWX: Global 3-Hourly 0.1° Bias-Corrected Meteorological Data Including Near-Real-Time Updates and Forecast Ensembles. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2022, 103, E710–E732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soci, C.; Hersbach, H.; Simmons, A.; Poli, P.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Poli, P.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Horányi, A.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis from 1940 to 2022. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2024, 150, 4014–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavers, D.A.; Simmons, A.; Vamborg, F.; Rodwell, M.J. An evaluation of ERA5 precipitation for climate monitoring. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 148, 3124–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Han, Y.; Tam, C.Y.; Yang, Z.L.; Fu, C. Bias-corrected CMIP6 global dataset for dynamical downscaling of the historical and future climate (1979–2100). Sci. Data 2021, 8, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouatadid, S.; Orenstein, P.; Flaspohler, G.; Cohen, J.; Oprescu, M.; Fraenkel, E.; Mackey, L. Adaptive bias correction for improved subseasonal forecasting. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golian, S.; Murphy, C. Evaluating Bias-Correction Methods for Seasonal Dynamical Precipitation Forecasts. J. Hydrometeor. 2022, 23, 1350–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, N.C.; Cole, J.N.S.; Kharin, V.V.; Lazare, M.; Scinocca, J.F.; Gillett, N.P.; Anstey, J.; Arora, V.; Christian, J.R.; Hanna, S.; et al. The Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5.0.3). Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 4823–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döscher, R.; Acosta, M.; Alessandri, A.; Anthoni, P.; Arsouze, T.; Bergman, T.; Bernardello, R.; Boussetta, S.; Caron, L.-P.; Carver, G.; et al. The EC-Earth3 Earth system model for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 2973–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, J.P.; Horowitz, L.W.; Adcroft, A.J.; Ginoux, P.; Held, I.M.; John, J.G.; Krasting, J.P.; Malyshev, S.; Naik, V.; Paulot, F.; et al. The GFDL Earth System Model Version 4.1 (GFDL-ESM 4.1): Overall coupled model description and simulation characteristics. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2020, 12, e2019MS002015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutjahr, O.; Putrasahan, D.; Lohmann, K.; Jungclaus, J.H.; von Storch, J.-S.; Brüggemann, N.; Haak, H.; Stössel, A. Max Planck Institute Earth System Model (MPI-ESM1.2) for the High-Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP). Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 3241–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seland, Ø.; Bentsen, M.; Olivié, D.; Toniazzo, T.; Gjermundsen, A.; Graff, L.S.; Debernard, J.B.; Gupta, A.K.; He, Y.-C.; Kirkevåg, A.; et al. Overview of the Norwegian Earth System Model (NorESM2) and key climate response of CMIP6 DECK, historical, and scenario simulations. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 6165–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, L.; Bremnes, J.B.; Haugen, J.E.; Engen-Skaugen, T. Technical Note: Downscaling RCM precipitation to the station scale using statistical transformations—A comparison of methods. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 3383–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.; Kim, S. Future drought analysis using SPI and EDDI to consider climate change in South Korea. Water Supply 2020, 20, 3266–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathbout, S.; Martin-Vide, J.; Lopez-Bustins, J.A. Drought characteristics projections based on CMIP6 climate change scenarios in Syria. J. Hydrol.-Reg. Stud. 2023, 50, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Perterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0 Contributors. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.W. Multivariate Density Estimation: Theory, Practice and Visualization; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droogers, P.; Allen, R.G. Estimating Reference Evapotranspiration Under Inaccurate Data Conditions. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2002, 16, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, K. Quantify uncertainty in historical simulation and future projection of surface wind speed over global land and ocean. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 054029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.A.; Peel, M.C.; Lowe, L.; Srikanthan, R.; McVicar, T.R. Estimating actual, potential, reference crop and pan evaporation using standard meteorological data: A pragmatic synthesis. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 1331–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, C.T. Using the SPI to identify drought. Drought Netw. News 2000, 12, 6–12. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtnetnews/1 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Allen, M.R. Liability for climate change. Nature 2003, 421, 891–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, P.A.; Christidis, N.; Otto, F.E.L.; Sun, Y.; Vanderlinden, J.-P.; van Oldenborgh, G.J.; Vautard, R.; von Storch, H.; Walton, P.; Yiou, P.; et al. Attribution of extreme weather and climate-related events. WIREs Clim. Change 2016, 7, e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopper, C.J.; Pearson, E.S. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika 1934, 26, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künsch, H.R. The Jackknife and the Bootstrap for General Stationary Observations. Ann. Stat. 1989, 17, 1217–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, D.; Romano, J.P. A Circular Block Resampling Procedure for Stationary Data. In Exploring the Limits of Bootstrap; Lepage, R., Billard, L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, V.F.V.V.; Jiménez, J.C.; Trigo, I. Evapotranspiration anomalies over the Pantanal region during the droughts 2018–2020. Remote Sens. 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulizia, C.; Camilloni, I.; Doyle, M. Identification of the principal patterns of summer moisture transport in South America and their representation by WCRP/CMIP3 global climate models. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2013, 112, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, I.F.A.; Silveira, V.P.; Figueroa, S.N.; Kubota, P.Y.; Bonatti, J.P.; de Souza, D.C. Climate variability over South America-regional and large scale features simulated by the Brazilian Atmospheric Model (BAM-v0). Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 2845–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, R.V.; de Oliveira, S.S.; Kayano, M.T.; Viegas, J.; de Souza, R.A.F.; Candido, L.A. The influence of different El Niño types on the South American rainfall. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 1374–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, S.; Cordero, R.R.; Damiani, A.; MacDonell, S.; Pizarro, J.; Goubanova, K.; Valenzuela, R.; Wang, C.; Rester, L.; Beaulieu, A. South America is becoming warmer, drier, and more flammable. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Leung, L.R.; Lu, J.; Zhou, T.; Huang, P. Advances in understanding the changes of tropical rainfall annual cycle: A review. Environ. Res. Clim. 2023, 2, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holthuijzen, M.; Beckage, B.; Clemins, P.J.; Higdon, D.; Winter, J.M. Robust bias-correction of precipitation extremes using a novel hybrid empirical quantile-mapping method. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 149, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Diaz, A.; Torres, R.R.; Zuluaga, C.F.; Cerón, W.L.; Oliveira, L.; Benezoli, V.; Rivera, I.A.; Marengo, J.A.; Wilson, A.B.; Medeiros, F. Current and Future Climate Extremes Over Latin America and Caribbean: Assessing Earth System Models from High Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP). Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 7, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, P.A.; Rendón, M.L.; Martínez, J.A.; Allan, R.P. Changes in atmospheric moisture transport over tropical South America: An analysis under a climate change scenario. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 61, 4949–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergier, I. Effects of highland land-use over lowlands of the Brazilian Pantanal. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 463–464, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.F.; Bevilacqua Alves, M.; Ferrari Silveira, C.; Amaral e Silva, A.; Abrantes Silva, T.; Juste dos Santos, V.; Calijuri, M.L. Fires dynamics in the Pantanal: Impacts of anthropogenic activities and climate change. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silio-Calzada, A.; Barquín, J.; Huszar, V.L.M.; Mazzeo, N.; Méndez, F.; Álvarez-Martínez, J.M. Long-term dynamics of a floodplain shallow lake in the Pantanal wetland: Is it all about climate? Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Roderick, M.L.; Leech, G.; Sun, F.; Huang, Y. The contribution of reduction in evaporative cooling to higher surface air temperatures during drought. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 7891–7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.O.; Dirmeyer, P.A. Characterizing the Relationship between Temperature and Soil Moisture Extremes and Their Role in the Exacerbation of Heat Waves over the Contiguous United States. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 2175–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Romanowicz, R. Uncertainty in SPI Calculation and Its Impact on Drought Assessment in Different Climate Regions over China. J. Hydrometeor. 2021, 22, 1369–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Lintner, B.R.; Boyce, C.K.; Lawrence, P.J. Land use change exacerbates tropical South American drought by sea surface temperature variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L19706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielen, D.; Schuchmann, K.L.; Ramoni-Perazzi, P.; Marquez, M.; Rojas, W.; Quintero, J.I.; Marques, M.I. Quo vadis Pantanal? Expected precipitation extremes and drought dynamics from changing sea surface temperature. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Souza, C.M.; Thonicke, K.; Burton, C.; Halladay, K.; Betts, R.A.; Lincoln, M.A.; Wagner, R.S. Changes in Climate and Land Use Over the Amazon Region: Current and Future Variability and Trends. Front. Earth Sci. 2018, 6, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF-Brasil. Pantanal Has Record Number of Fire Outbreaks in the First 20 Days of November. WWF-Brasil, 22 November 2023. Available online: https://www.wwf.org.br/?87282 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- D’Acunha, B.; Dalmagro, H.J.; Zanella de Arruda, P.H.; Biudes, M.S.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Uribe, M.; Couto, E.G.; Brando, P.M.; Vourlitis, G.; Johnson, M.S. Changes in evapotranspiration, transpiration and evaporation across natural and managed landscapes in the Amazon, Cerrado and Pantanal biomes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 346, 109875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Yin, L.; Li, W.; Arias, P.A.; Dickinson, R.E.; Huang, L.; Chakraborty, S.; Fernandes, K.; Liebmann, B.; Fisher, R.; et al. Increased dry-season length over southern Amazonia in recent decades and its implication for future climate projection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 110, 18110–18115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, J.; Arias, P.A.; Vieira, S.C.; Martínez, J.A. Influence of longer dry seasons in the Southern Amazon on patterns of water vapor transport over northern South America and the Caribbean. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 52, 2647–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alho, C.J.R.; Sabino, J. Seasonal Pantanal Flood Pulse: Implications for Biodiversity Conservation—A Review. Oecologia Aust. 2012, 16, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, M.; Aguiar Abdo, M.S.; dos Santos, C.; Leal Sander, N.; da Silva Nunes, J.R.; Lopes Lázaro, W.; da Silva, C.J. Long-term analysis of aquatic macrophyte diversity and structure in the Paraguay river ecological corridor, Brazilian Pantanal wetland. Aquat. Bot. 2022, 178, 103500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alho, C.J.R.; Silva, J.S.V. Effects of Severe Floods and Droughts on Wildlife of the Pantanal Wetland (Brazil)—A Review. Animals 2012, 2, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).