Abstract

Adaptive behaviour has been viewed broadly as an individual’s ability to meet the standards of social responsibilities and independence; however, this definition has been a source of debate amongst researchers and clinicians. Based on the rich history and the importance of the construct of adaptive behaviour, the current study aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of the application of adaptive behaviour models to assessment tools, through a systematic review. A plethora of assessment measures for adaptive behaviour have been developed in order to adequately assess the construct; however, it appears that the only definition on which authors seem to agree is that adaptive behaviour is what adaptive behaviour scales measure. The importance of the construct for diagnosis, intervention and planning has been highlighted throughout the literature. It is recommended that researchers and clinicians critically review what measures of adaptive behaviour they are utilising and it is suggested that the definition and theory is revisited.

1. Introduction

Adaptive behaviour has been viewed broadly as “the effectiveness and degrees to which the individual meets the standards of personal independence and social responsibilities” [1] (p. 11). The construct includes skills that an individual requires in order to meet personal needs and to be able to cope with the social and natural demands in their environment. Specifically, Ditterline et al. (2008) noted that these skills involve being able to independently care for one’s personal health and safety, dress and bathe, communicate, behave in a socially acceptable manner, effectively engage in academic skills, recreation and work, and to engage in a community lifestyle [2]. However, there are a number of studies indicating that the construct of adaptive behaviour is still emerging and the definition had therefore been source of debate [3,4,5,6]. In particular, Harris and Greenspan (2016) argue that one of the key issues with the construct of adaptive behaviour is that it lacks an underlying theoretical framework that has never been fully resolved [7]. Therefore, the current review aims to explore the current definitions and applications of the models of adaptive behaviour to assessment tools within the literature.

The earliest reference to adaptive behaviour emerged in the 1800s during the Renaissance and Reformation period, as an adjunct to defining intellectual disability (ID) [8]. Despite the rising interest in adaptive behaviour, the introduction of intelligence testing decreased the popularity of the construct. In 1910, Binet and Simon related their assessment of the intelligence quotient (or IQ) to a table of traits distinguishing between “idiot”, “imbecile”, and “moron” [9]. Following this movement to assess ID in terms of IQ and social adaptability, Goddard revised the levels of mental retardation in terms of industrial capacity [9]. In 1920, Doll (1953) stressed the importance of utilising an ability assessment in diagnosing and treating individuals with ID [10]. Doll argued that assessments of individuals with ID were incomplete without valid estimates of adaptive behaviour, in which he termed social competence and social maturity at the time. In 1936, Doll developed what can be considered the first assessment of the adaptive behaviour construct, the Vineland Social Maturity Scale (VSMS), which aided the diagnosis of ID through a formal assessment of social competence and maturity [11]. The scale consisted of 117 items that measured an individual’s abilities and growth in relation to everyday situations, which consisted of three separate categories: self-help, locomotion and socialisation.

Building on this concept, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), previously known as the American Association on Mental Retardation, formally included adaptive behaviour deficits as an integral part of the definition of ID in 1959. Their classification manual created a dual-criterion approach for the diagnosis of ID—intellectual functioning; and impairments in maturation, learning, and social adjustment. A review of the AAIDD’s manual took place in 1961, where the three initial impairments were altered to fall under an umbrella construct known as ‘adaptive behaviour’. The definition of adaptive behaviour comprised of two key elements:

- The degree to which an individual is able to function and maintain him or herself independently; and

- The degree to which he or she satisfactorily meets the culturally imposed demand of personal and social responsibility [12] (p. 61)

The origin of the modern conceptualisation of adaptive behaviour can be found in the diagnosis of ID. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fifth Edition (DSM-5) is a guide for the diagnosis of mental disorders [13]. It is imperative that a reliable diagnosis is made such that appropriate recommendations and treatments can be recommended. The construct of adaptive behaviour remains a vital component for the diagnosis of ID under diagnostic criteria B:

“Deficits in adaptive functioning that results in failure to meet developmental and sociocultural standards for personal independence and social responsibility. Without ongoing support, the adaptive deficits limit functioning in one or more activities of daily life, such as communication, social participation, and independent living, across multiple environments, such as home, school, work, and community”.[13] (p. 33)

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) is the diagnostic tool for “epidemiology, health management, and clinical purposes” [14]. Under Chapter V, classification code F70–F79, the ICD-10 includes the definition and criteria for a diagnosis of Mental Retardation (this term is under review for the ICD-11; due to be released 2018). The ICD-10 diagnosis bears similarities to that of the DSM-5; however, in terms of adaptive behaviour, the criteria clearly highlight a four-factor model: cognitive, language, motor, and social abilities. Specifically, the ICD-10 states that mental retardation is “a condition of arrested or incomplete development of the mind, which is especially characterised by impairment of skills manifested during the developmental period, skills which contribute to the overall level of intelligence, i.e., cognitive, language, motor, and social abilities. Retardation can occur with or without any other mental or physical condition” [14] (F70–F79).

Building on the AAIDD definition and the requirements for an adaptive behaviour measurement in the DSM and ICD, Nihira, Fosterm, Shellhaas and Leland (1968) were awarded funding to develop a tool that measured adaptive behaviour [15]. Nihira and his colleagues published the first standardised assessment instrument of adaptive behaviour, which they termed the Adaptive Behaviour Checklist (1968). This scale has since been revised twice and is now known as the AAMD Adaptive Behaviour Scale (1993). In 2000, Harrison and Oakland developed the Adaptive Behaviour Assessment System (ABAS) [16]. This assessment measure aligned with the three-factor structure outlined by the AAIDD. It was developed to assess the conceptual, social, and practical domains of adaptive functioning [17]. The original measure has since been reviewed and the third edition (2015) measures adaptive behaviour skills from birth to 89 years.

Similarly, the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales (VABS) defined the construct of adaptive behaviour as a three-factor structure, including the broad domains of communication, daily living skills, and socialisation, but also has an optional measurement of motor skills (>7 years old and <50 years old), and maladaptive functioning [18]. The most recent version of the VABS is the Vineland-3, published in 2016. Sparrow, Cicchetti and Saulnier (2016), describe the Vineland-3 as a multipurpose tool, which can be used to support diagnoses, determine eligibility or qualification for special services, plan rehabilitation or intervention programs, and track and report progress [19].

Adaptive behaviour remains an emerging construct in terms of both conceptualisation and measurement [6]. The DSM-5 and the ICD-10 highlight the requirement of a measurement of adaptive behaviour for diagnostic purposes; however, there is a lack of clarity regarding the definition of adaptive behaviour. Jenkinson (1996) eloquently stated, “the only definition on which authors seem to agree is that adaptive behaviour is what adaptive behaviour scales measure” [20] (p. 99). Arguably this is an issue for most psychological constructs—being defined by how they are measured. However, as can be seen with the history of intelligence theory and assessment, adaptive behaviour as a construct requires more attention to develop to the same extent as intelligence. This point can be emphasised with the Cattell–Horn–Carroll (CHC) theory of intelligence, which is considered the most comprehensive and empirically supported psychometric theory of the structure of cognitive and academic abilities to date [21]. By the late twentieth century, the tests of the time did not reflect the diversity of the substantial evidence for the eight or nine broad cognitive Gf-Gc abilities (for example, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised only measured two or three CHC abilities adequately). The CHC theory is the foundation on which many new and recently-revised intelligence batteries have been based [22].Therefore, as intelligence theory develops, the assessment tools that measure intelligence are revisited and reviewed. It is argued that the theory of adaptive behaviour has not undertaken the same level of attention and rigor as intelligence. Due to the extensive history and pivotal role of adaptive behaviour for diagnoses, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the application of adaptive behaviour models to assessment tools within the literature through systematic review.

2. Materials and Methods

Literature Search

The methodology applied for systematically identifying relevant adaptive behaviour models was based on the terminology used throughout history and the common definitions noted in the introduction. The first database utilised in the review was PsychINFO, given that the database contains more than four million records and upwards of over 4000 expertly-indexed records added each week [23]. Subsequently, the database was searched using the terms summarised in Table 1 for works that contain one of the keywords or keyword combinations in their title, abstract, or list of keywords.

Table 1.

Syntax used in the systematic literature search for PsychINFO.

The language of the papers was limited to English. The year of publication was not limited in the search; however, only papers that appeared in peer-reviewed academic journals were considered relevant (i.e., book chapters and conference papers were excluded). All papers identified in the search process were checked for relevance by reading the article in full (the deduction process is demonstrated in Table 2). Papers were considered relevant for this review if the following criteria were met:

Table 2.

Review protocol.

- The central focus of the paper must be adaptive behaviour/functioning

- The paper must discuss the model, theory or assessment tools that they have utilised for the study (e.g., whether they utilised the Vineland definition, or the Vineland scales for measurement of adaptive behaviour)

After the results were gathered and analysed from the initial search, a secondary search was conducted to analyse further assessment measures and tools of adaptive behaviour. Given the focus on psychological assessment measures, the secondary search utilised two databases: Health and Psychosocial Instruments (HPI), which provides information about behavioural measurement instruments, and Mental Measurements Yearbook and Tests in Print (MMYTP), which provides the most current descriptive test data. The search terms used in the secondary search were ‘adaptive behavior (with enabling multiple spellings of the word) or adaptive function * (with * = truncation), given that the narrow focus of the databases is already restricted to material containing psychological assessment measures.

3. Results

The results of the search and study selection are shown in Table 2. The original search process carried out in April–July 2017 produced 3974 articles, 107 of which were selected for full review. Of these, 75 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria, thus 32 studies were selected for review. The summary characteristics of the included studies are located in Table 3. The identified assessment tools and their factor structures are located in Table 4. The available psychometric properties of each assessment tool follow in Table 5 (the validity properties listed are adapted from Messick (1995) [24]).

Table 3.

Summary characteristics of included studies.

Table 4.

Factors from adaptive behaviour assessment scales mapped across themes.

Table 5.

Available psychometric properties for identified assessment scales.

3.1. Year of Publication

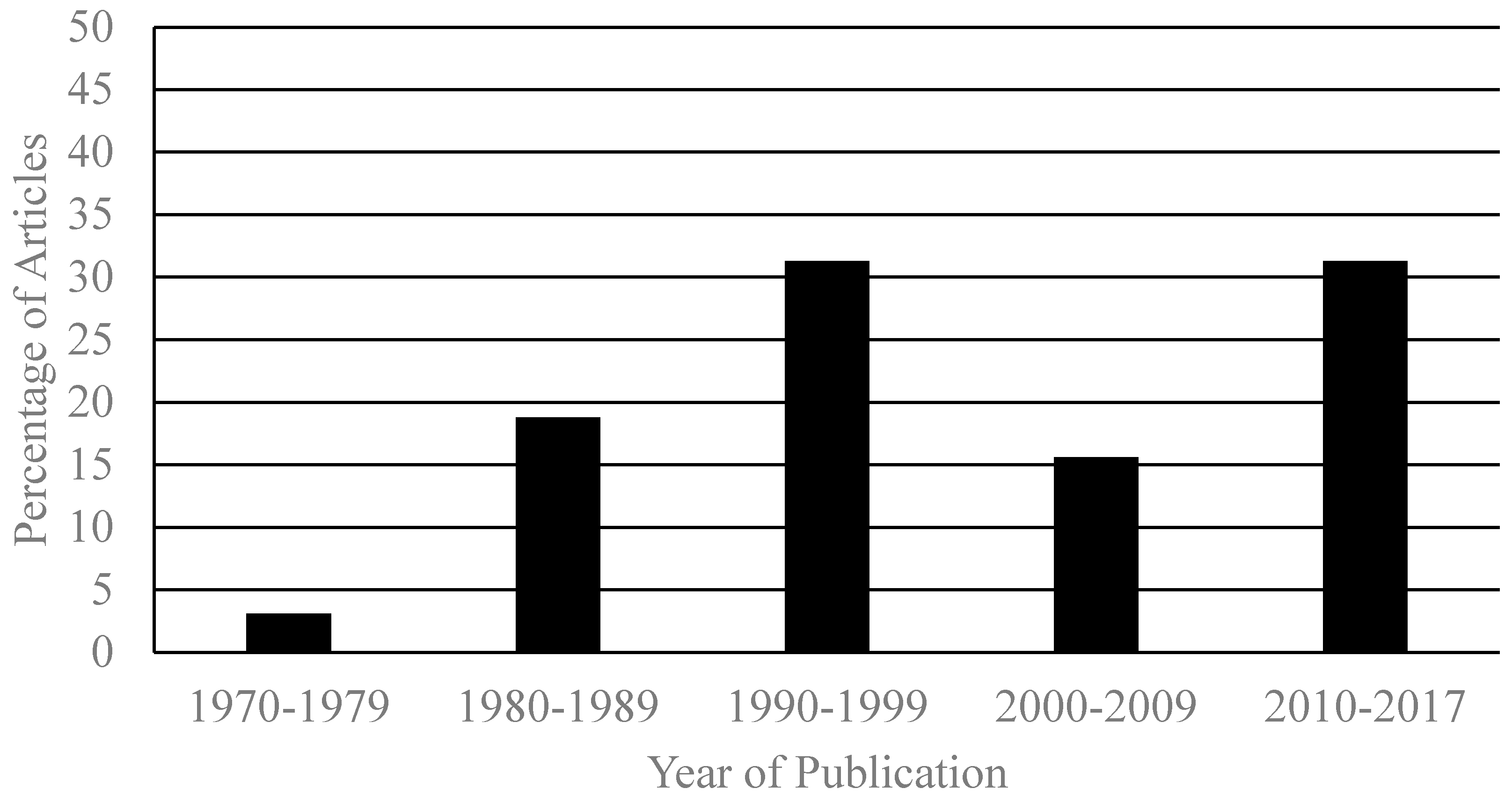

The year of publication for the included articles ranged from 1972 to 2016. See Figure 1 for graphical representation.

Figure 1.

Percentage of reviewed articles published in each year.

3.2. Location

Twenty-five of the 32 studies identified were carried out in the US (78%), two studies were carried out in Spain and one study was conducted each in Turkey, Canada, Israel, the UK and Australia.

Eighty-four percent of the target populations identified within the search were clinical samples. Ten of the 32 studies had participants with known or suspected ID, and seven of the studies had participants with known or suspected Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Of the remaining 15 studies, seven had normative samples and the remaining eight articles utilised clinical samples containing individuals with either developmental delay, cerebral palsy, William’s syndrome, hospital treatment for schizophrenia or depression, premature birth, learning and behavioural problems, high-risk populations and symptomatic HIV infection.

3.3. Adaptive Behaviour Assessment Tools

Twelve different adaptive behaviour assessment tools were identified within the review. While at face value some of the included scales (for example; PEDI-CAT, Coping Inventory and Role Functioning Scale) are not strictly measurements of adaptive behaviour, the studies have utilised these scales for this purpose and were therefore included [30,32,38]. The number of factors measuring adaptive behaviour ranged from two to six, with 33% highlighting a three-factor model. Table 4 below highlights the number of factors of each assessment measure and their associated subscales under overarching themes. The themes were determined through semantic and qualitative categorisation. The themes used within the table reflect the common definitions of the DSM-5: social, practical and conceptual; VABS: communication, socialisation, daily living skills; and AAIDD: social, practical and conceptual. Factors from each of the identified adaptive behaviour assessment scales were allocated to each of the themes based on qualitative categorisation. Furthermore, Table 5 highlights the psychometric properties available for the identified assessment scales. The results indicate that many of the aspects of construct validity are inadequate or not reported. The two most widely used assessment scales, ABAS-II and VABS-II, demonstrate the most psychometrically-sound properties.

The extensive history surrounding the emergence of adaptive behaviour highlights its importance for diagnoses and treatment planning. However, the term adaptive behaviour lacks clarity and a clear theoretical framework. The aim of this systematic review was to provide a narrative synthesis of the current frameworks and theoretical models within the literature. Searching across three electronic databases, 32 articles were identified which met the inclusion criteria. Despite the rigour of the review, it is difficult to provide conclusive results with regards to a common framework of adaptive behaviour. In fact, the current study further highlights the ambiguity and lack of agreement with regards to what the construct actually is.

Much of the research conducted on adaptive behaviour has focussed centrally on its measurement, rather than on theoretical aspects. The current study identified 12 different adaptive behaviour assessment tools that each measure the construct in alternative ways. The number of factors range from two to six depending on the assessment measure. A thematic analysis of each of the factors identified that all 12 assessment tools analysed social and practical components of adaptive behaviour; whereas, only half assessed communication or conceptual components. The two most prominent conceptual frameworks of adaptive behaviour (the AAIDD and the VABS) have some shared theoretical underpinnings, there are also clear differences; for example, the addition of motor skills and maladaptive behaviour domains within the VABS. Furthermore, there are clear differences amongst the reviewed assessment tools (albeit not equal contributors).This finding resonates with the same opinion of Jenkinson (1996) over 20 years ago, where he stated that the only definition of adaptive behaviour that authors agree upon is “that adaptive behaviour is what adaptive behaviour scales measure” [20] (p. 99). It is difficult to separate the construct of adaptive behaviour from the commercially-available adaptive behaviour scales. Therefore, it is apparent that the measurement of adaptive behaviour is driving policy and thereby becoming accepted as “theory”, rather than theory informing assessment. It is therefore important that the theoretical underpinnings of adaptive behaviour are challenged and explored further, given the widespread use and importance of adaptive behaviour as a diagnostic framework.

Furthermore, the articles analysed within this review indicate that many of the adaptive behaviour assessment scales available lack in many areas of construct validity. Despite having evidence for reliability and model-fit estimates, the six areas of construct validity identified by Messick (1995) are not adequately assessed nor have been made readily available [24]. According to a systematic review conducted by Floyd et al. (2017), the Vineland II scales demonstrate good content and external validity, adequate consequential validity and inadequate structural validity, in comparison to the ABAS-II scale, where evidence of content validity is considered good and structural and consequential validity are considered inadequate [54]. These findings highlight that even the most widely-used adaptive behaviour scales lack important aspects of construct validity. This indicates that it is difficult to determine the validity of research and assessment of current adaptive behaviour practices in Australia.

The results of the review suggested that although adaptive behaviour was of international interest, there was a strong western influence. Of the articles identified within this review, 78% were published by authors within the US. This finding suggests that the understanding of adaptive behaviour is shaped and influenced by the US. Furthermore, when taking into consideration that the definition of adaptive behaviour is primarily via assessment, a plausible conclusion is that adaptive behaviour is best understood as a reflection of typical behaviour within an American (or at least western) context, despite having clinical utility worldwide. Arguably this is problematic for many psychological constructs; however, the construct of intelligence has undertaken significant research to provide a sound theoretical underpinning and has been normed to apply to assessments cross-culturally. Some key assessments for adaptive behaviour have not been normed in different cultures, despite the cultural context required of an individual influencing what is considered ‘adaptive’. This finding resonates with the critical message highlighted by Jones (2010), where he suggested that psychology research is predominantly WEIRD—measures of western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic cultures [56]. Jones cautioned that WEIRDos are not representative of other cultures and understanding human nature from a US perspective limits the generalisability of the research. When reflecting on this message and the findings from the current review, it can be argued that current research pertaining to the definition of adaptive behaviour may not be representative of all populations and consequently, requires a theoretical understanding from different cultural perspectives.

Specifically, within Australia, the measurement of the construct is required for diagnosis, practical applications and within legislative contexts. Given the importance of adaptive behaviour, it was unexpected that only one out of 32 articles had been published by an Australian author [20]. The study conducted by Jenkinson (1996) [20] aimed to explore the difficulties associated with the psychometric concepts and measurements to identify individuals with ID. After a review of the available assessment measures, he concluded that the introduction of adaptive behaviour measures has confounded the short-comings of standardised intelligence tests and that the construct needs a theoretical base in order to remain a psychological construct. Of the remaining articles, two were published in Spain and one article was published each in the United Kingdom, Israel, Canada and Turkey. Despite the studies being conducted in different countries, they all use existing western adaptive behaviour measurement tools to analyse adaptive behaviour. The findings of the current review highlight the need for a theoretical understanding of adaptive behaviour globally, and more specifically for different cultures and populations.

The data gathered within this review highlighted a pattern regarding the target populations used within the studies. Of the identified articles, 84.4% of the studies investigated clinical samples, with 21.8% focusing on individuals with ASD and 32.3% focusing on individuals with ID. Given that the diagnoses for ASD and ID require a measurement of adaptive behaviour to meet the criterion, this finding is not unexpected. However, it does stimulate suspicion of the validity of the construct of adaptive behaviour outside of these populations. The results indicated that 15.6% of the studies provided normative data for the ABAS. This highlights a particular strength of the ABAS and the paucity of normative data of comparative assessment tools. This review has highlighted that the construct of adaptive behaviour is basically defined by the measurements that assess the construct. The findings suggest that by continuing to focus on clinical samples, the construct of adaptive behaviour may be defined by the presentation of adaptive behaviour within these populations. The importance of investigating adaptive behaviour within clinical samples should not be undermined; however, the construct should also be defined within a typically-developing population.

4. Limitations

Given the nature of a systematic literature review, the current study is subject to its own intrinsic limitations. The current review may have been influenced by publication bias and time lag bias, where the identified articles may have been limited by studies that are accepted for publication and the rapid or delayed publication of research findings. In addition, the current study excluded studies that were not published in English. This exclusion criteria may have limited the number of identified studies published in other countries. However, given the review did return articles published in countries other than the US, but still utilised western adaptive behaviour assessment tools, it can be argued that studies published in other languages may follow the same westernised trend of adaptive behaviour.

5. Conclusions

The current study systematically reviewed the current frameworks and models of the construct of adaptive behaviour. The findings indicate that currently there is no universal definition of adaptive behaviour and that the definition is based predominantly on what the assessment tools measure. Specifically, the measurements are driving the theory, whereby US clinical populations are the central source of research. Whilst acknowledging the requirement of an adaptive behaviour measurement for funding access and diagnoses, it is advised that future researchers and clinicians critically review which definitions and measurements of adaptive behaviour they are utilising in their studies and practice, particularly given the lack of evidence for construct validity amongst scales. The major concern highlighted by the current review is that researchers are considering adaptive behaviour through one cultural lens, without having a robust theory underpinning its definition and understanding. This is problematic when the rating of adaptive behaviour may well depend on what the cultural context requires of an individual at different ages/stages. The possible consequences of taking such a narrow view of a critical construct are numerous, particularly given the strong reliance on adaptive behaviour in the DSM-5 and ICD-10 for diagnostic purposes. It is strongly recommended that the definition and theory of adaptive behaviour is revisited and increased evaluation is encouraged to ensure our research is current and valid to inform practice.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this article was based on the program requirements for the first author’s PhD. Gratitude is expressed to the time and dedication provided by the second authors for their supervision and guidance. This research has been supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Author Contributions

Jessica A. Price, Zoe A. Morris and Shane Costello all contributed to the discussion and initial review plan. Jessica A. Price conducted the systematic review and completed the manuscript. Zoe A. Morris and Shane Costello contributed equally to many revisions to arrive at the final product, as equal supervisors of Jessica A. Price. Therefore, the author’s agree that Jessica A. Price is first author, followed by Zoe A. Morris and Shane Costello as equal second authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no reportable conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Grossman, H. Manual on Terminology and Classification in Mental Retardation; American Association on Mental Deficiency: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ditterline, J.; Banner, D.; Oakland, T.; Bexton, D. Adaptive behavior profiles of students with disabilities. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2008, 24, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.Z.; Fehrmann, P.G.; Harrison, P.L.; Pottebaum, S.M. The relation between adaptive behavior and intelligence: Testing alternative explanations. J. Sch. Psychol. 1987, 25, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, P.; Verdugo, M.A.; Arias, B.; Gomez, L.E. Development of an instrument for diagnosing significant limitations in adaptive behavior in early childhood. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinnett, T.A.; Fuqua, D.R.; Coombs, W.T. Construct validity of the AAMR adaptive behavior scale-school: 2. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 28, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tasse, M.J.; Schalock, R.L.; Balboni, G.; Berasni, H.; Borthwick-Duffy, S.A.; Spreat, S.; Thissen, D.; Widamen, K.F.; Zhang, D. The construct of adaptive behavior: Its conceptualization, measurement, and use in the field of intellectual disability. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 117, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.C.; Greenspan, S. Definition and Nature of Intellectual Disability; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerenberger, R. A History of Mental Retardation: A Quarter Century of Progress; Bookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, H.H. Psychology of the Normal and Abnormal; Dodd, Mead: New York, NY, USA, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Doll, E.A. Measurement of Social Competence: A Manual for the Vineland Social Maturity Scale; Educational Publishers, Inc.: Vineland, NJ, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Doll, E.A. The Vineland Social Maturity Scale: Revised Condensed Manual of Directions; The Vineland Training School: Vineland, NJ, USA, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Heber, R. A Manual on Terminology and Classification in Mental Retardation, 2nd ed.; American Association on Mental Deficiency: Springfield, IL, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nihira, K.; Foster, R.; Shellhaas, M.; Leland, H. Adaptive Behavior Checklist; American Association on Mental Deficiency: Washington, DC, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, P.; Oakland, T. Adaptive Behaviour Assessment System (ABAS-II); The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luckasson, R.; Borthwick-Duffy, S.; Buntinx, W.H.E.; Coulter, D.L.; Craig, E.M.; Schalock, R.L.; Snell, M.E.; Spitalnik, D.M.; Spreat, S.; Tasse, M.J. Mental Retardation: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports, 10th ed.; American Association on Mental Retardation: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, S.; Balla, D.; Cicchetti, D. Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales (Survey Form); American Guidance Service: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.V.; Saulnier, C.A. Vineland-3: Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 3rd ed.; Pearson Assessments: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, J.C. Identifying intellectual disability: Some problems in the measurement of intelligence and adaptive behaviour. Aust. Psychol. 1996, 31, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, D.P.; Harrison, P.L. Contemporary Intellectual Assessment, Second Edition: Theories, Tests, and Issues; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, V.C.; Flanagan, D.P.; Radwan, S. Contemporary Intellectual Assessment, Second Edition: Theories, Tests, and Issues: The Impact of the Cattell-Horn-Carroll Theory on Test Developmental and Interpretation of Cognitive and Academic Abilities; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. 2017. Available online: http://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/psycinfo-printable-fact-sheet (accessed on 28 April 2017).

- Messick, S. Standards of validity and the validity of standards in performance assessment. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 1995, 14, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Meares, P.; Lane, B.A. Assessing the Adaptive Behavior of Children and Youths; National Association of Social Workers, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, B.; Verdugo, M.A.; Navas, P.; Gomez, L.E. Factor structure of the construct of adaptive behavior in children with and without intellectual disability. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2012, 13, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aricak, O.T.; Oakland, T. Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis for the teacher form, ages 5 to 21, of the adaptive behavior assessment system-II. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2010, 28, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.S.; Zelko, F.A. Variability in adaptive behavior in children with developmental delay. J. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 50, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, S.; Morgan, S.B. Adaptive and intellectual functioning in Autistic and nonautistic retarded children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1996, 26, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarello, L.A.; Almasri, N.; Palisano, R.J. Factors related to adaptive behavior in children with cerebral Palsy. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2009, 30, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, R. A study of the adaptive behavior of retarded children and the resultant effects of this use in the diagnosis of mental retardation. J. Educ. Train. Ment. Retard. 1982, 17, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Coster, W.J.; Kramer, J.M.; Tian, F.; Dooley, M.; Liljenquist, K.; Kao, Y.; Ni, P. Evaluating the appropriateness of a new computer-administered measure of adaptive function for children and youth with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2016, 20, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvdevany, I. Self-concept and adaptive behaviour of people with intellectual disability in integrated and segregated recreation activities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2002, 46, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.H.; Lense, M.D.; Dykens, E.M. Longitudinal trajectories of intellectual and adaptive functioning in adolescents and adults with Williams syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2016, 60, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fombonne, E.; Siddons, F.; Achard, S.; Frith, U.; Happe, F. Adaptive behaviour and theory of mind in Autism. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1994, 3, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.J.; Del’Homme, M.; Guthrie, D.; Zhang, F. Vineland adaptive behavior scale scores as a function of age and initial IQ in 210 Autistic Children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1999, 29, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillham, J.E.; Carter, A.S.; Volkmar, F.R.; Sparrow, S.S. Toward a developmental operational definition of Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000, 20, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.H.; Sewell, D.R.; Cooley, E.L.; Leavitt, N. Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: The role functioning scale. Community Ment. Health J. 1993, 29, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.A.; Carter, A.S. Predictors and course of daily living skills development in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, A.E.; Scott, K.G.; Bauer, C.R. The adaptive behaviour inventory (ASBI): A new assessment of social competence in high-risk three-year-olds. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1992, 10, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberty, T.J. Relationship of the WISC_R factors to the adaptive behavior scale—School edition in a referral sample. J. Sch. Psychol. 1986, 24, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsucker, P.F.; Nelson, R.O.; Clark, R.P. Standardization and evaluation of the classroom adaptive behavior checklist for school use. Except. Child. 1986, 53, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, H.; Oakland, T.D. The differentiation of adaptive behaviours: Evidence from high and low performers. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 35, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, M.; Harel, B.; Fein, D.; Allen, D.; Dunn, M.; Feinstein, C.; Morris, R.; Waterhouse, L.; Rapin, I. Predictors and correlates of adaptive functioning in children with developmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakland, T.D.; Algina, J. Adaptive behavior assessment system-II parent/primary caregiver form: Ages 0–5: Its factor structure and other implications for practice. J. Appl. Sch. Psyhol. 2011, 27, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakland, T.D.; Iliescu, D.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.H. Cross-national assessment of adaptive behavior in three countries. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2013, 31, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perozzi, J.A. Language acquisition as adaptive behavior. J. Ment. Retard. 1972, 10, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz, J.; Hamdan-Allen, G. Effects of age and IQ on adaptive behavior domains for children with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1995, 25, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifer, R.; Sameroff, A.J.; Jones, F. Adaptive behavior in young children of emotionally disturbed women. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 1981, 1, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasse, M.J.; Schalock, R.L.; Thissen, D.; Balboni, G.; Bersani, H.; Borthwick-Duffy, S.A.; Spreat, S.; Widamen, K.F.; Zhang, D.; Navas, P. Development and standardization of the diagnostic adaptive behavior scale: Application of item respone theory to the assessment of adaptive behavior. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 121, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolters, P.L.; Brouwers, P.; Moss, H.A.; Pizzo, P.A. Adaptive behavior of children with symptomatic HIV infection before and after zidovudine therapy. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1994, 19, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, H.R. Children’s adaptive behaviors: Measure and source generalizability. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1988, 6, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, G.R.; Shands, E.I.; Alfonso, V.C.; Phillips, J.F.; Autry, B.K.; Mosteller, J.A.; Skinner, M.; Irby, S. A systematic review and psychometric evaluation of adaptive behavior scales and recommendations for practice. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2015, 31, 83–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glascoe, F.P.; Byrne, K.E. The usefulness of the DP-II in developmental screening. Clin. Pediatr. 1993, 32, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboni, G.; Tasse, M.J.; Schalock, R.L.; Brotherwick-Duffy, S.A.; Spreat, S.; Thissen, D.; Widamen, K.F.; Zhang, D.; Navas, P. The diagnostic adaptive behavior scale: Evaluating its diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 2884–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D. A WEIRD view of human nature skews psychologists’ studies. Science 2010, 328, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).