Visualized Analysis of Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Comorbidity Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

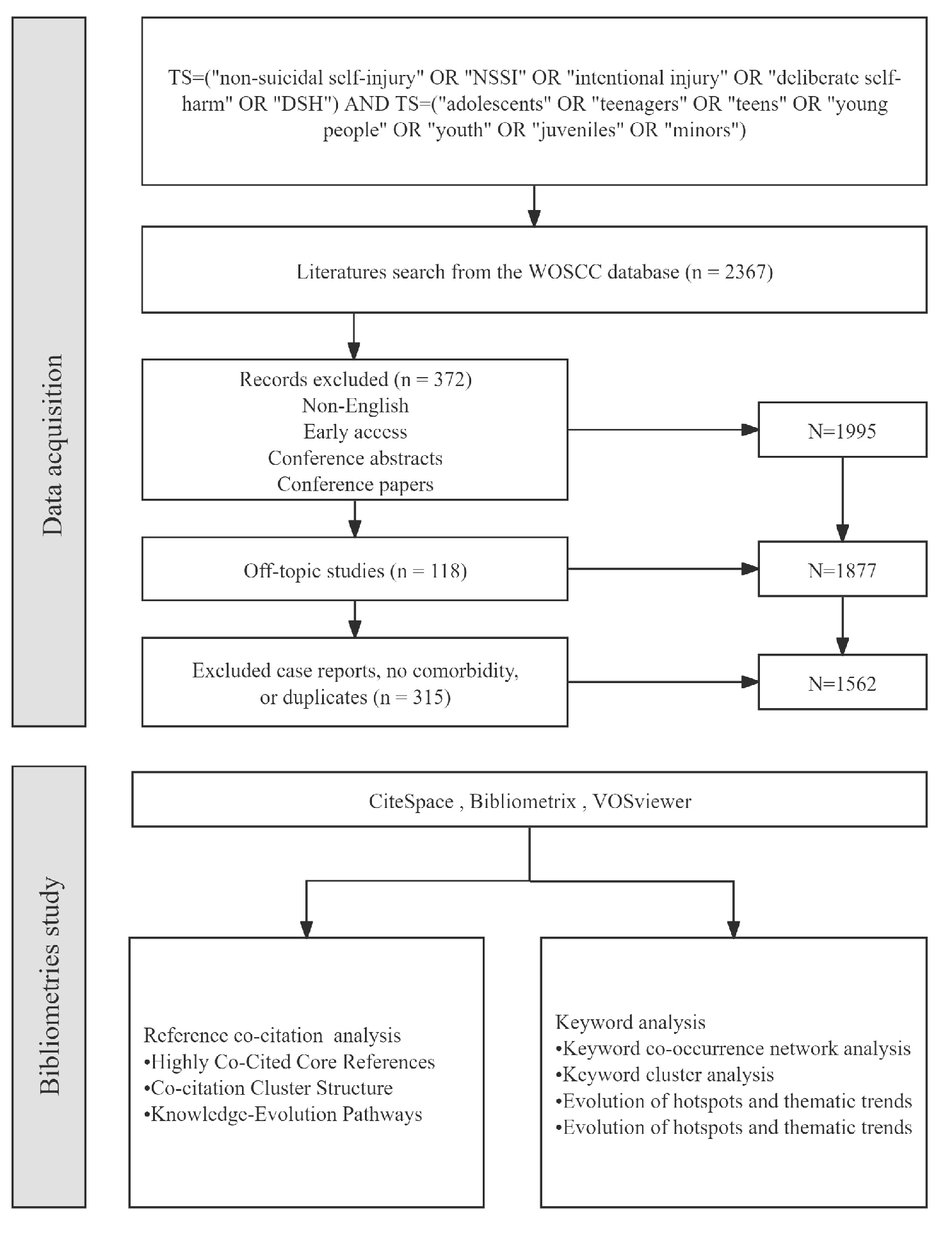

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Research Methods and Tools

3. Results

3.1. Annual Publication Trends

3.2. Hot Topics

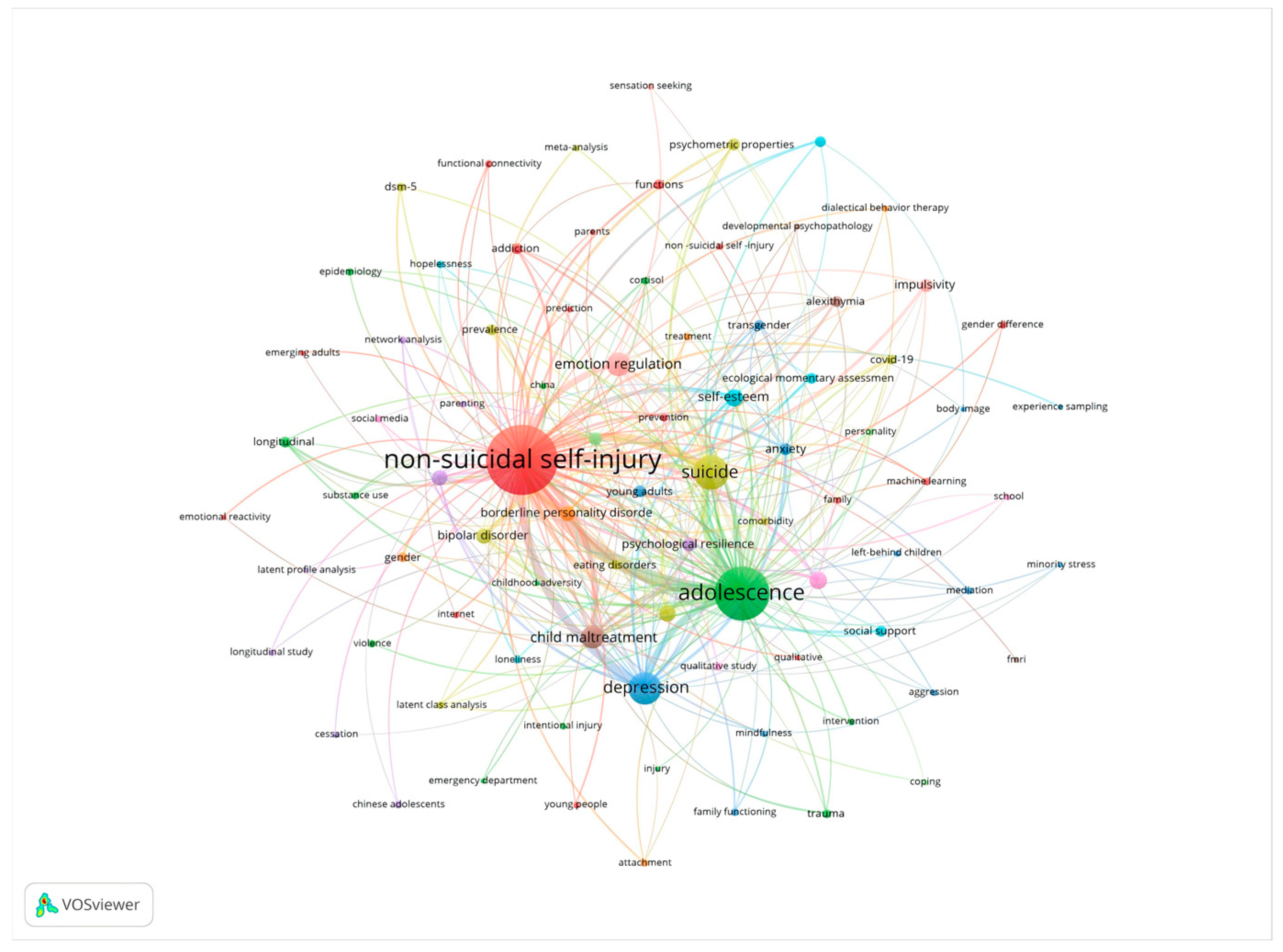

3.2.1. Keyword Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

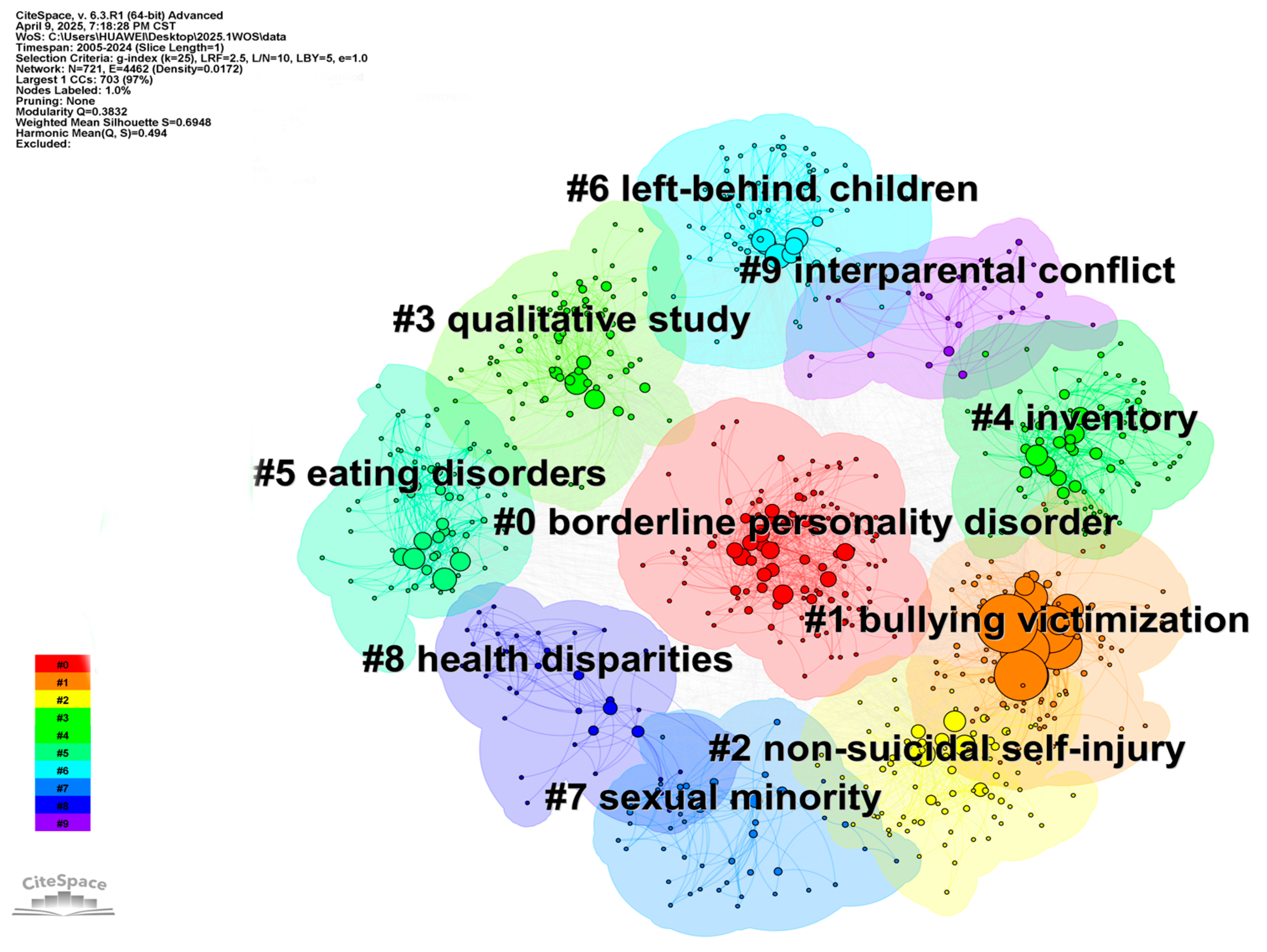

3.2.2. Keyword Cluster Analysis

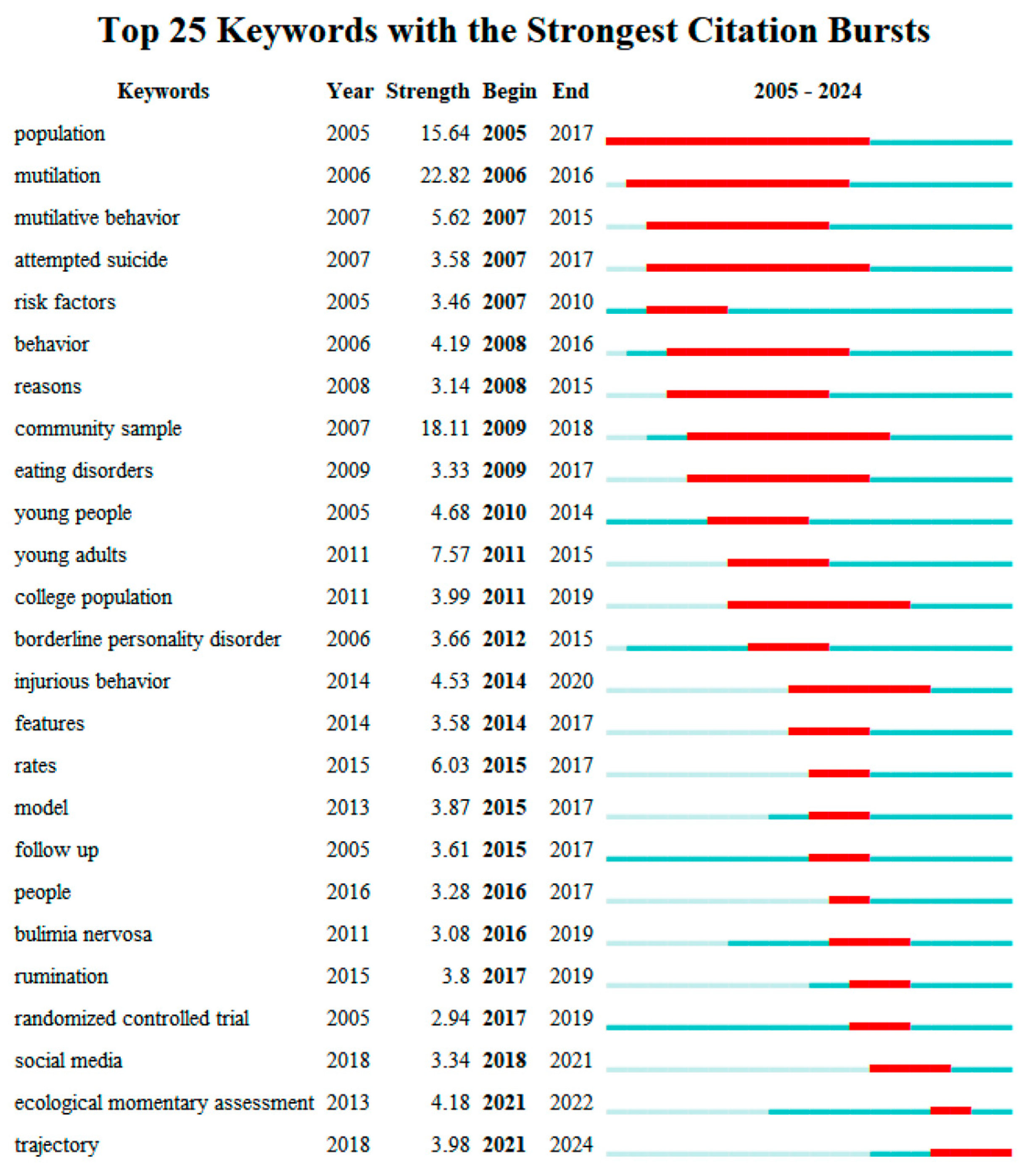

3.2.3. Evolution of Hotspots and Thematic Trends

- (1)

- Artificial intelligence methods are being introduced into NSSI prediction and risk modeling research;

- (2)

- Increasing attention is being paid to adolescents in China and other non–Western cultural contexts;

- (3)

- Researchers are shifting from single-variable analyses toward psychological network construction and dynamic evolutionary models based on complex systems.

3.3. Co-Citation Analysis: Network Structure of Theoretical Foundations and Core Research Findings

3.3.1. Highly Co-Cited Core References

3.3.2. Co-Citation Cluster Structure

3.3.3. Knowledge Evolution Pathways

4. Discussion

4.1. Current Challenges

4.2. Future Research Characteristics

4.3. Comparison Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahrenholtz, M. S., Nicholas, J., Sacco, A., & Bresin, K. (2025). Sexual and gender minority stress in nonsuicidal self-injury engagement: A meta-analytic review. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 55(1), e13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ale Ebrahim, N., Salehi, H., Embi, M. A., Habibi, F., Gholizadeh, H., & Motahar, S. M. (2014). Visibility and citation impact. International Education Studies, 7(4), 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. C., Wallander, J. L., Elliott, M. N., & Schuster, M. A. (2023). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: A structural model with socioecological connectedness, bullying victimization, and depression. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(4), 1190–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, M. S., Starace, N. K., Black, V. P., & Avina, C. (2020). Implementation of dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal and self-harming adolescents in a community clinic. Archives of Suicide Research, 24(1), 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresin, K., & Schoenleber, M. (2015). Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickman, L. J., Ammerman, B. A., Look, A. E., Berman, M. E., & McCloskey, M. S. (2014). The relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and borderline personality disorder symptoms in a college sample. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R. C., & Plener, P. L. (2017). Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(3), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelens, T., Costantini, G., Luyckx, K., & Claes, L. (2020). Comorbidity between non-suicidal self-injury disorder and borderline personality disorder in adolescents: A graphical network approach. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 580922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelens, T., Luyckx, K., Gandhi, A., Kiekens, G., & Claes, L. (2019). Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: Longitudinal associations with psychological distress and rumination. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N., Lugo-Marín, J., Oriol, M., Pérez-Galbarro, C., Restoy, D., Ramos-Quiroga, J.-A., & Ferrer, M. (2024). Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 157, 107048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M. J. (2014). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 48(3), 275. [Google Scholar]

- Cavelti, M., Blaha, Y., Lerch, S., Hertel, C., Berger, T., Reichl, C., Koenig, J., & Kaess, M. (2024). The evaluation of a stepped care approach for early intervention of borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 11(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D., Ying, J., Zhou, X., Wu, H., Shen, Y., & You, J. (2022). Sexual minority stigma and nonsuicidal self-injury among sexual minorities: The mediating roles of sexual orientation concealment, self-criticism, and depression. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(4), 1690–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X., Zhou, Y., Li, L., Hou, Y., Liu, D., Yang, X., & Zhang, X. (2021). Influential factors of non-suicidal self-injury in an eastern cultural context: A qualitative study from the perspective of school mental health professionals. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 681985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Fu, W., Ji, S., Zhang, W., Sun, L., Yang, T., He, K., & Zhou, Y. (2023). Relationship between borderline personality features, emotion regulation, and non-suicidal self-injury in depressed adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y. T. D., Wong, P. W. C., Lee, A. M., Lam, T. H., Fan, Y. S. S., & Yip, P. S. F. (2013). Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: Prevalence, co-occurrence, and correlates of suicide among adolescents in Hong Kong. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(7), 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, A., Cella, S., & Cotrufo, P. (2017). Nonsuicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. B., Lawlor, M. P., Hiroeh, U., Kapur, N., & Appleby, L. (2003). Factors that influence emergency department doctors’ assessment of suicide risk in deliberate self-harm patients. European Journal of Emergency Medicine, 10(4), 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L., Pastore, M., Palladino, B. E., Reime, B., Warth, P., & Menesini, E. (2023). The development of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) during adolescence: A systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 339, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, E. C., Duan, A. M., Kearns, J. C., Kleiman, E. M., Conwell, Y., & Glenn, C. R. (2022). Measuring adolescents’ self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: Comparing ecological momentary assessment to a traditional interview. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50(8), 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, G., Wilson, M. S., Garisch, J. A., Robinson, K., Brocklesby, M., Kingi, T., O’Connell, A., & Russell, L. (2018). Non-suicidal self-injury, sexuality concerns, and emotion regulation among sexually diverse adolescents: A multiple mediation analysis. Archives of Suicide Research, 22(3), 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Y., Kuang, L., Xu, X.-M., Ai, M., He, J.-L., Wang, W., Hong, S., Chen, J. M., Cao, J., & Zhang, Q. (2025). Research on prediction model of adolescent suicide and self-injury behavior based on machine learning algorithm. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1521025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, A., Luyckx, K., Baetens, I., Kiekens, G., Sleuwaegen, E., Berens, A., Maitra, S., & Claes, L. (2018). Age of onset of non-suicidal self-injury in Dutch-speaking adolescents and emerging adults: An event history analysis of pooled data. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 80, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y., Zhu, R., & Maimaituerxun, M. (2022). Bibliometric review of carbon neutrality with CiteSpace: Evolution, trends, and framework. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(51), 76668–76686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, D., Christou, M. A., Dixon, A. C., Featherston, O. J., Rapti, I., Garcia-Anguita, A., Villasis-Keever, M., Reebye, P., Christou, E., & Al Kabir, N. (2018). Prevalence and characteristics of self-harm in adolescents: Meta-analyses of community-based studies 1990–2015. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(10), 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, C. R., & Klonsky, E. D. (2009). Social context during non-suicidal self-injury indicates suicide risk. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(1), 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goreis, A., Chang, D., Klinger, D., Zesch, H.-E., Pfeffer, B., Oehlke, S.-M., Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Claes, L., Plener, P. L., & Kothgassner, O. D. (2025). Impact of social media on triggering nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: A comparative ambulatory assessment study. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 12(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, C. A., Stewart, S. L., & Willoughby, T. (2012). Examining the link between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature and an integrated model. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasking, P., Boyes, M. E., Finlay-Jones, A., McEvoy, P. M., & Rees, C. S. (2019). Common pathways to NSSI and suicide ideation: The roles of rumination and self-compassion. Archives of Suicide Research, 23(2), 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, S., Choo, T.-H., Galfalvy, H., Mann, J. J., & Stanley, B. H. (2022). Effect of non-suicidal self-injury on suicidal ideation: Real-time monitoring study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 221(2), 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelscher, E. C., Victor, S. E., Kiekens, G., & Ammerman, B. (2025). Ethical considerations for the use of ecological momentary assessment in non-suicidal self-injury research. Ethics & Behavior, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooley, J. M., & Franklin, J. C. (2018). Why do people hurt themselves? A new conceptual model of nonsuicidal self-injury. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(3), 428–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Hou, Y., Li, C., & Ren, P. (2025). The risk factors for the comorbidity of depression and self-injury in adolescents: A machine learning study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In-Albon, T. (2015). Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents. European Psychologist, 20(3), 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M., Edinger, A., Fischer-Waldschmidt, G., Parzer, P., Brunner, R., & Resch, F. (2020). Effectiveness of a brief psychotherapeutic intervention compared with treatment as usual for adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: A single-centre, randomised controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M., Koenig, J., Bauer, S., Moessner, M., Fischer-Waldschmidt, G., Mattern, M., Herpertz, S. C., Resch, F., Brown, R., & In-Albon, T. (2019). Self-injury: Treatment, Assessment, Recovery (STAR): Online intervention for adolescent non-suicidal self-injury-study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelada, L., Hasking, P., & Melvin, G. (2018). Adolescent NSSI and recovery: The role of family functioning and emotion regulation. Youth & Society, 50(8), 1056–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Kiekens, G., Hasking, P., Boyes, M., Claes, L., Mortier, P., Auerbach, R. P., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Green, J. G., Kessler, R. C., Myin-Germeys, I., Nock, M. K., & Bruffaerts, R. (2018). The associations between non-suicidal self-injury and first onset suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, G., Robinson, K., Tatnell, R., & Kirtley, O. J. (2021). Opening the black box of daily life in nonsuicidal self-injury research: With great opportunity comes great responsibility. JMIR Mental Health, 8(11), e30915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(2), 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E. D., & Glenn, C. R. (2008). Psychosocial risk and protective factors. In Self-injury in youth (pp. 45–58). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., & Glenn, C. R. (2013). The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: Converging evidence from four samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(1), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J., Klier, J., Parzer, P., Santangelo, P., Resch, F., Ebner-Priemer, U., & Kaess, M. (2021). High-frequency ecological momentary assessment of emotional and interpersonal states preceding and following self-injury in female adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothgassner, O. D., Goreis, A., Robinson, K., Huscsava, M. M., Schmahl, C., & Plener, P. L. (2021). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescent self-harm and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 51(7), 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudinova, A. Y., Brick, L. A., Armey, M., & Nugent, N. R. (2024). Micro-sequences of anger and shame and non-suicidal self-injury in youth: An ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 65(2), 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H., Yang, Y., Zhu, T., Zhang, X., & Dang, J. (2024). Network analysis of the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury, depression, and childhood trauma in adolescents. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, K., Yu, R., Chen, Y., Chen, X., Wu, X., Huang, X., & Liu, N. (2024). Alterations of regional brain activity and corresponding brain circuits in drug-naïve adolescents with nonsuicidal self-injury. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 24997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.-S., Wong, C. H., McIntyre, R. S., Wang, J., Zhang, Z., Tran, B. X., Tan, W., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2019). Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lorabi, S., Sánchez-Teruel, D., Robles-Bello, M. A., & Ruiz-García, A. (2023). Variables that enhance the development of resilience in young gay people affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 17(11), 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, E., Berk, M. S., Asarnow, J. R., Adrian, M., Cohen, J., Korslund, K., Avina, C., Hughes, J., Harned, M., Gallop, R., & Linehan, M. M. (2018). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menderes, A. S. Y., & Çuhadaroğlu, F. (2025). Impact of mentalization, identity diffusion and psychopathology on nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 97(2), 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, F., Amini, J., Sinyor, M., Schaffer, A., Lanctôt, K. L., & Mitchell, R. H. (2024). Sex differences in the global prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: A meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 7(6), e2415436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlenkamp, J. J., Claes, L., Havertape, L., & Plener, P. L. (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J., Burke, T. A., Bettis, A. H., Kudinova, A. Y., Thompson, E. C., MacPherson, H. A., Fox, K. A., Lawrence, H. R., Thomas, S. A., & Wolff, J. C. (2021). Social media use and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 87, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaou, S., Pascual, J. C., Soler, J., Ortega, G., Marco-Pallarés, J., & Vega, D. (2025). Mapping punishment avoidance learning deficits in non-suicidal self-injury in young adults with and without borderline personality disorder: An fMRI study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 370, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, S., Yin, X., Pan, B., Chen, H., Dai, C., Tong, C., Chen, F., & Feng, X. (2024). Understanding comorbidity between non-suicidal self-injury and depressive symptoms in a clinical sample of adolescents: A network analysis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M. K., & Favazza, A. R. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Definition and classification. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 9–18). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M. K., Joiner, T. E., Jr., Gordon, K. H., Lloyd-Richardson, E., & Prinstein, M. J. (2006). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research, 144(1), 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M. K., & Kessler, R. C. (2006). Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts versus suicide gestures: Analysis of the national comorbidity survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(3), 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, M., Gameroff, M. J., Marcus, S. C., Greenberg, T., & Shaffer, D. (2005). Emergency treatment of young people following deliberate self-harm. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(10), 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, O., Kocaman, R., & Kanbach, D. K. (2024). How to design bibliometric research: An overview and a framework proposal. Review of Managerial Science, 18(11), 3333–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J. R., Mereish, E. H., Krek, M. A., Chuong, A., Ranney, M. L., Solomon, J., Spirito, A., & Yen, S. (2020). Sexual orientation differences in non-suicidal self-injury, suicidality, and psychosocial factors among an inpatient psychiatric sample of adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plener, P. L., Schumacher, T. S., Munz, L. M., & Groschwitz, R. C. (2015). The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: A systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.-N., & Gan, X. (2024). Parental emotional warmth and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effect of bullying involvement and moderating effect of the dark triad. Children and Youth Services Review, 161, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, C., Heyer, A., Brunner, R., Parzer, P., Völker, J. M., Resch, F., & Kaess, M. (2016). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, childhood adversity and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 74, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, C., & Kaess, M. (2021). Self-harm in the context of borderline personality disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology, 37, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, C., Rockstroh, F., Lerch, S., Fischer-Waldschmidt, G., Koenig, J., & Kaess, M. (2023). Frequency and predictors of individual treatment outcomes (response, remission, exacerbation, and relapse) in clinical adolescents with nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychological Medicine, 53(16), 7636–7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A. F., Kosciow, B. A., Listerud, L., Clifford, B., & Meanley, S. (2025). Toward a social ecological understanding of nonsuicidal self-injury in sexual and gender minority individuals: A scoping review. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G., Aguglia, A., Amerio, A., Canepa, G., Adavastro, G., Conigliaro, C., Nebbia, J., Franchi, L., Flouri, E., & Amore, M. (2023). The relationship between bullying victimization and perpetration and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(1), 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T., Liu, J., Wang, H., Yang, B. X., Liu, Z., Liu, J., Wan, Z., Li, Y., Xie, X., & Li, X. (2024). Risk prediction model for non-suicidal self-injury in chinese adolescents with major depressive disorder based on machine learning. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swannell, S. V., Martin, G. E., Page, A., Hasking, P., & St John, N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(3), 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J., Shu, Y., Li, Q., Liang, L., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Wu, G., & Luo, Y. (2025). Global, regional, and national burden of self-harm among adolescents aged 10-24 years from 1990 to 2021, temporal trends, health inequities and projection to 2041. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1564537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J., Li, G., Chen, B., Huang, Z., Zhang, Y., Chang, H., Wu, C., Ma, X., Wang, J., & Yu, Y. (2018). Prevalence of and risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury in rural China: Results from a nationwide survey in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P. J., Jomar, K., Dhingra, K., Forrester, R., Shahmalak, U., & Dickson, J. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsypes, A., Lane, R., Paul, E., & Whitlock, J. (2016). Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in heterosexual and sexual minority young adults. Comprehensive Psychiatry 65, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B. J., Dixon-Gordon, K. L., Austin, S. B., Rodriguez, M. A., Rosenthal, M. Z., & Chapman, A. L. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury with and without borderline personality disorder: Differences in self-injury and diagnostic comorbidity. Psychiatry Research, 230(1), 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmani, S. S., Mehendale, M., Shaikh, M. Y., Sudan, S., Guntipalli, P., Ouellette, L., Malik, A. S., Siddiqi, N., Walia, N., & Shah, K. (2024). Understanding the impact of adverse childhood experiences on non-suicidal self-injury in youth: A systematic review. Alpha Psychiatry, 25(2), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldmeijer, L., Terlouw, G., Boonstra, N., & van Os, J. (2025). Opening doors or building cages? The adverse consequences of psychiatric diagnostic labels. Current Opinion in Psychology, 65, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, S. E., Hipwell, A. E., Stepp, S. D., & Scott, L. N. (2019). Parent and peer relationships as longitudinal predictors of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury onset. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Luo, B., Hong, B., Yang, M., Zhao, L., & Jia, P. (2022). The relationship between family functioning and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: A structural equation modeling analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 309, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. J., Li, X., Ng, C. H., Xu, D.-W., Hu, S., & Yuan, T. F. (2022). Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 46, 3916132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedig, M. M., & Nock, M. K. (2007). Parental expressed emotion and adolescent self-injury. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(9), 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westers, N. J. (2024). Cultural interpretations of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide: Insights from around the world. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 29(4), 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitlock, J. L. (2006). Youth perceptions of life at school: Contextual correlates of school connectedness in adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 10(1), 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J. C., Thompson, E., Thomas, S. A., Nesi, J., Bettis, A. H., Ransford, B., Scopelliti, K., Frazier, E. A., & Liu, R. T. (2019). Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 59, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q., Song, X., Huang, L., Hou, D., & Huang, X. (2022). Global prevalence and characteristics of non-suicidal self-injury between 2010 and 2021 among a non-clinical sample of adolescents: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 912441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q., Song, X., Huang, L., Hou, D., & Huang, X. (2023). Association between life events, anxiety, depression and non-suicidal self-injury behavior in Chinese psychiatric adolescent inpatients: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1140597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., Li, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, L., Sun, T., Zhang, C., Liu, Z., Liu, J., Wen, L., & Gong, X. (2024). The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents with depressive disorders. Psychiatry Research, 331, 115638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterqvist, M. (2015). The DSM-5 diagnosis of nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: A review of the empirical literature. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental health, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterqvist, M., Lundh, L. G., Dahlström, O., & Svedin, C. G. (2013). Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(5), 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., & Zhou, A. (2024). Longitudinal relations between non-suicidal self-injury and both depression and anxiety among senior high school adolescents: A cross-lagged panel network analysis. PeerJ, 12, e18134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T., Zhong, Y., Wei, Y., Su, Y., Dang, Y., & Wu, X. (2021). Emotion regulation strategies and family function in non-suicidal self-injury adolescents. Chinese Journal of Child Health Care, 29(9), 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q., Gu, H., & Cheng, Y. (2024). Interparental conflict and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: The roles of harsh parenting, identity confusion, and friendship quality. Current Psychology, 43(25), 21557–21567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ranking | Frequency | Centrality | Year | Keyword |

| 1 | 949 | 0.03 | 2005 | non-suicidal self-injury |

| 2 | 725 | 0.02 | 2005 | adolescence |

| 3 | 650 | 0.01 | 2006 | suicide |

| 4 | 592 | 0.02 | 2005 | prevalence |

| 5 | 589 | 0.02 | 2007 | harm |

| 6 | 471 | 0.01 | 2005 | risk factors |

| 7 | 359 | 0.02 | 2007 | depression |

| 8 | 341 | 0.01 | 2006 | behavior |

| 9 | 270 | 0.05 | 2010 | emotion regulation |

| 10 | 252 | 0 | 2009 | meta-analysis |

| 11 | 164 | 0.06 | 2010 | mental health |

| 12 | 163 | 0.04 | 2010 | child maltreatment |

| 13 | 163 | 0.05 | 2007 | community sample |

| 14 | 146 | 0.04 | 2011 | behaviors |

| 15 | 141 | 0.06 | 2006 | borderline personality disorder |

| 16 | 126 | 0.03 | 2013 | validity |

| 17 | 125 | 0.04 | 2010 | reliability |

| 18 | 116 | 0.02 | 2015 | symptoms |

| 19 | 112 | 0.05 | 2014 | stress |

| 20 | 109 | 0.02 | 2014 | psychometric properties |

| Ranking | Count | Year | Reference |

| 1 | 135 | 2014 | (Swannell et al., 2014) |

| 2 | 123 | 2018 | (Linehan, 1993) |

| 3 | 103 | 2018 | (Taylor et al., 2018) |

| 4 | 100 | 2012 | (Muehlenkamp et al., 2012) |

| 5 | 98 | 2014 | (Carter, 2014) |

| 6 | 89 | 2019 | (Lim et al., 2019) |

| 7 | 80 | 2019 | (Wolff et al., 2019) |

| 8 | 72 | 2018 | (Kiekens et al., 2018) |

| 9 | 64 | 2015 | (Bresin & Schoenleber, 2015) |

| 10 | 63 | 2013 | (Zetterqvist et al., 2013) |

| 11 | 58 | 2019 | (Victor et al., 2019) |

| 12 | 57 | 2018 | (Hooley & Franklin, 2018) |

| 13 | 56 | 2018 | (Gandhi et al., 2018) |

| 14 | 54 | 2017 | (Brown & Plener, 2017) |

| 15 | 53 | 2018 | (Tang et al., 2018) |

| 16 | 52 | 2013 | (Klonsky et al., 2013) |

| 17 | 52 | 2015 | (Plener et al., 2015) |

| 18 | 51 | 2017 | (Cipriano et al., 2017) |

| 19 | 51 | 2012 | (Hamza et al., 2012) |

| 20 | 50 | 2022 | (Y. J. Wang et al., 2022) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Qi, C. Visualized Analysis of Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Comorbidity Networks. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111513

Zhang Z, Guo J, Zhao Y, Li X, Qi C. Visualized Analysis of Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Comorbidity Networks. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111513

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhen, Juan Guo, Yali Zhao, Xiangyan Li, and Chunhui Qi. 2025. "Visualized Analysis of Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Comorbidity Networks" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111513

APA StyleZhang, Z., Guo, J., Zhao, Y., Li, X., & Qi, C. (2025). Visualized Analysis of Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Comorbidity Networks. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111513