Childhood Maltreatment and Adolescent Risky Behavior: Mediating the Effect of Parent–Adolescent Conflict and Violent Tendencies

Abstract

1. Childhood Maltreatment and Adolescent Risky Behavior

2. Parent–Adolescent Conflict

3. Violent Tendencies

4. The Present Study

5. Method

5.1. Participants

5.2. Measures

5.3. Data Analyses

6. Results

7. Discussion

8. Limitations and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Responding to Child Maltreatment: A Clinical Handbook for Health Professionals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, D.; Toth, S.L. Child maltreatment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 409–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruhn, M.A.; Compas, B.E. Effects of maltreatment on coping and emotion regulation in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Child Dev. 2020, 91, e51–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Cicchetti, D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.A.; Martire, L.M. Parental childhood maltreatment and the later-life relationship with parents. Psychol. Aging 2019, 34, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, Y.D.; Jang, S.; Shin, J.; Kim, J.W. Psychological aspects of child maltreatment. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2022, 65, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, K.L.; Myint, M.T.; Zeanah, C.H. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, R.E.; Byambaa, M.; De, R.; Butchart, A.; Scott, J.; Vos, T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, I.; Austin, J.L.; Gooding, P. Association of childhood maltreatment with suicide behavior among young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2012563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Dodge, K.A.; Pettit, G.S.; Bates, J.E.; Crozier, J.; Kaplow, J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.M.; Hunt, A.; Mathews, B.; Haslam, D.M.; Malacova, E.; Dunne, M.P.; Erskine, H.E.; Scott, J.G.; Higgins, D.J.; Finkelhor, D.; et al. The association between child maltreatment and health risk behavior and conditions throughout life in the Australian child maltreatment study. Med. J. Aust. 2023, 218, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, S. Analysis of deviant friends’ mediator effect on relationships between adolescent risk behavior and peer bullying, abuse experiences and psychological resilience. Eğitim Ve Bilim 2018, 43, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Hawke, L.D.; Sanches, M.R.; Henderson, J. The impact of child maltreatment on mental health and substance use trajectories among adolescents. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2023, 17, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimpop, R.M. The Psychology of Risk Taking Behavior; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor, R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J. Adolesc. Health 1991, 12, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogosch, F.; Oshri, A.; Cicchetti, D. From child maltreatment to adolescent cannabis abuse and dependence: A developmental cascade model. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, T.; Graña, J.; González-Cieza, L. Self-reported physical and emotional abuse among youth offenders and their association with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2013, 58, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duprey, E.B.; Oshri, A.; Liu, S. Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to adolescent suicide-related behaviors: The internalizing and externalizing comorbidity hypothesis. Dev. Psychopathol. 2020, 32, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobulsky, J.; Villodas, M.; Yoon, D.; Wildfeuer, R.; Steinberg, L.; Dubowitz, H. Adolescent neglect and health risk. Child Maltreat. 2021, 27, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, T.; Kotch, J.; Wiley, T.; Litrownik, A.; English, D.; Thompson, R.; Zolotor, A.J.; Block, S.D.; Dubowitz, H. Internalizing problems: A potential pathway from childhood maltreatment to adolescent smoking. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzun, M.; Sezgin, E.; Çakır, Z.; Şirin, H. Investigating emotional regulation, aggression and self-esteem in sexually abused adolescents. Eur. Res. J. 2023, 9, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Kobulsky, J.; Yoon, D.; Kim, W. Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to adolescent substance use: The roles of posttraumatic stress symptoms and mother-child relationships. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 82, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, E.; Rogosch, F.; Guild, D.; Cicchetti, D. Neighborhood disadvantage and adolescent substance use disorder. Child Maltreat. 2015, 20, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Zhen, R. How do physical and emotional abuse affect depression and problematic behavior in adolescents? The roles of emotional regulation and anger. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 129, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Building on the foundation of general strain theory: Specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. In Recent Developments in Criminological Theory; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 311–354. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana, J.G. Adolescents, Families, and Social Development: How Teens Construct Their Worlds; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Sinha, R.; Simmons, J.A.; Healy, S.M.; Mayes, L.C.; Hommer, R.E.; Crowley, M.J. Parent–adolescent conflict interactions and adolescent alcohol use. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. J. Res. Adolesc. 2001, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.A.; Jain, A.; Wilson, T.; Deros, D.E.; Jacobs, I.; Dunn, E.J.; Aldao, A.; Stadnik, R.; De Los Reyes, A. Moderated mediation of the link between parent-adolescent conflict and adolescent risk-taking: The role of physiological regulation and hostile behavior in an experimentally controlled investigation. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2019, 41, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.B.; Solmeyer, A.R.; McHale, S.M. Sibling differences in parent–child conflict and risky behavior: A three-wave longitudinal study. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, N.; Tian, L. The parent-adolescent relationship and risk-taking behaviors among Chinese adolescents: The moderating role of self-control. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T. Should parents’ physical punishment of children be considered a source of toxic stress that affects brain development? Fam. Relat. 2016, 65, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishion, T.J.; McMahon, R.J. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 1, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savla, J.; Roberto, K.A.; Jaramillo-Sierra, A.L.; Gambrel, L.E.; Karimi, H.A.; Butner, L.M. Childhood abuse affects emotional closeness with family in mid and later life. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J. Childhood maltreatment and psychological well-being in later life: The mediating effect of contemporary relationships with the abusive parent. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2018, 73, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, T. Causes of Delinquency; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Widom, C.S. The cycle of violence. Science 1989, 244, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Avcı, Ö.H.; Yıldırım, İ. Prevalence of violent tendency in adolescents. J. Theor. Educ. Sci. 2015, 8, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, L.; Yu, R.; Fazel, S. Childhood maltreatment and violent outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 21, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C. The effect of childhood maltreatment on violent behavior in adulthood. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 32, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İkiz, F.E.; Sağlam, A. Ortaokul öğrencilerinin şiddet eğilimleri ile okula bağlılık düzeyleri arasındaki ilişkinin incelenmesi. İlköğretim Online 2017, 16, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrenkohl, T.I.; Fedina, L.; Roberto, K.A.; Raquet, K.L.; Hu, R.X.; Rousson, A.N.; Mason, W.A. Child maltreatment, youth violence, intimate partner violence, and elder mistreatment: A review and theoretical analysis of research on violence across the life course. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, K.A.; Bates, J.E.; Pettit, G.S. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science 1990, 250, 1678–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xie, R.; Ding, W.; Jiang, M.; Kayani, S.; Li, W. You hurt me, so I hurt myself and others: How does childhood emotional maltreatment affect adolescent violent behavior and suicidal ideation? J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP22647–NP22672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Fink, L.; Handelsman, L.; Foote, J.; Lovejoy, M.; Wenzel, K.; Sapareto, E.; Ruggiero, J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, H.; Alparslan, N. The validity, reliability, and factor structure of the Childhood Maltreatment Scale in a university student sample. Turk. J. Psychiatry 1999, 10, 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Gençtanırım-Kuru, T. Predicting Risky Behavior in Adolescents. Ph.D. Dissertation, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haskan, Ö.; Yıldırım, İ. Development of the violent tendency scale. Educ. Sci. 2012, 37, 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Eryılmaz, A.; Mammadov, S. Examination of the psychometric properties of the Adolescent-Parent Conflict Scale. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2016, 23, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, M.S.; MacKinnon, D.P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedini, K.M.; Fagan, A.A. From child maltreatment to adolescent substance use: Different pathways for males and females? Fem. Criminol. 2020, 15, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, C.L.; Tyler, K.A.; Bersani, B.E. Child neglect and adolescent violence: Examining the effects of self-control and peer rejection. Violence Vict. 2005, 20, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.; Campbell, S.B. Developmental Psychopathology and Family Process: Theory, Research, and Clinical Implications; Cummings, E.M., Davies, P.T., Campbell, S.B., Eds.; Foreword by Dante Cicchetti; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, G.R.; DeBaryshe, B.D.; Ramsey, E.A. Developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, C.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Sousa, C. Review of research on child maltreatment and violence in youth. Trauma Violence Abus. 2008, 9, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arata, C.M.; Langhinrichsen Rohling, J.; Bowers, D.; O’Brien, N. Differential correlates of multitype maltreatment among urban youth. Child Abus. Negl. 2007, 31, 393415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brezina, T. General strain theory. In The Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Skewness | Kurtosis | Mean (Female) | SD (Female) | Mean (Male) | SD (Male) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risky behavior | 1.27 | 2.51 | 70.02 | 21.03 | 71.40 | 23.75 |

| Parent–adolescent conflict | 1.30 | 1.70 | 18.50 | 6.29 | 18.74 | 6.07 |

| Violent tendency | 0.691 | 0.701 | 32.22 | 6.77 | 35.41 | 8.53 |

| Childhood maltreatment | 0.869 | −0.415 | 67.06 | 22.35 | 74.30 | 22.22 |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |||

| 1. Risky behavior | - | 0.54 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.20 ** | ||

| 2. Parent–adolescent conflict | - | 0.49 ** | 0.27 ** | |||

| 3. Violent tendency | - | 0.22 ** | ||||

| 4. Childhood maltreatment | - | |||||

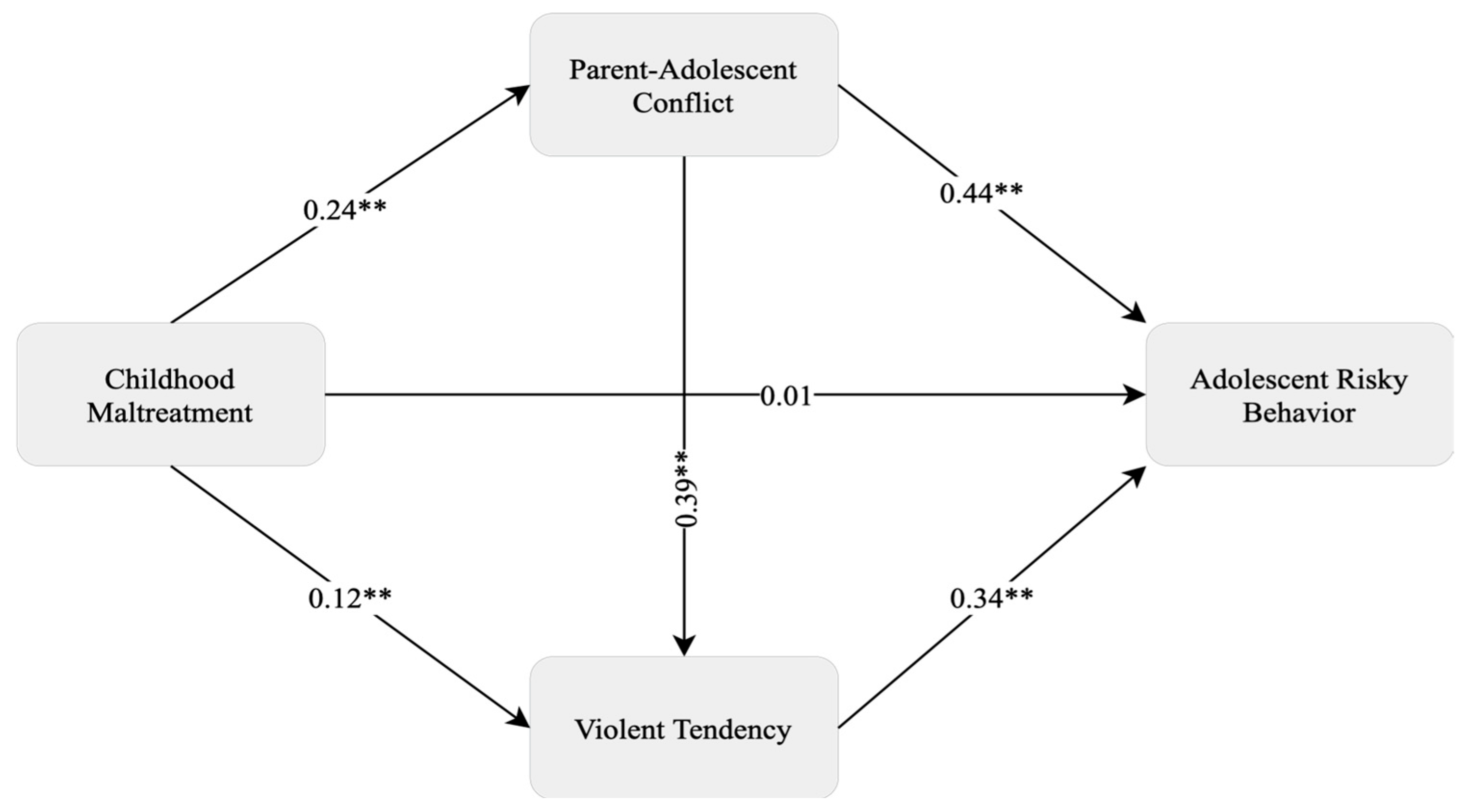

| Antecedent | Consequent | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | t | p | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

| M1 (Parent–Adolescent Conflict) | ||||||

| X (Childhood Maltreatment) | 0.24 | 0.05 | 4.90 | 0.000 | 0.14 | 0.33 |

| Constant | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.50 | 0.619 | −0.12 | 0.07 |

| R2 = 0.07 | ||||||

| F = 24.02; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| M2 (Violent Tendency) | ||||||

| X (Childhood Maltreatment) | 0.12 | 0.05 | 2.27 | 0.023 | 0.01 | 0.22 |

| M1 (Parent–Adolescent Conflict) | 0.39 | 0.06 | 6.61 | 0.000 | 0.28 | 0.51 |

| Constant | 0.00 | 0.05 | 001 | 0.990 | −0.10 | 0.10 |

| R2 = 0.17 | ||||||

| F = 30.85; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Y (Adolescent Risky Behavior) | ||||||

| X (Childhood Maltreatment) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.761 | −0.07 | 0.10 |

| M1 (Parent–Adolescent Conflict) | 0.44 | 0.05 | 8.20 | 0.000 | 0.33 | 0.55 |

| M2 (Violent Tendency) | 0.34 | 0.05 | 7.08 | 0.000 | 0.25 | 0.44 |

| Constant | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.956 | −0.08 | 0.09 |

| R2 = 0.40 | ||||||

| F = 67.42; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Path | Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.29 |

| Direct effect | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.10 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.26 |

| CM → PAC → ARB | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| CM → VT → ARB | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| CM → PAC → VT→ ARB | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özdemir Bişkin, S. Childhood Maltreatment and Adolescent Risky Behavior: Mediating the Effect of Parent–Adolescent Conflict and Violent Tendencies. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111058

Özdemir Bişkin S. Childhood Maltreatment and Adolescent Risky Behavior: Mediating the Effect of Parent–Adolescent Conflict and Violent Tendencies. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(11):1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111058

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzdemir Bişkin, Serap. 2024. "Childhood Maltreatment and Adolescent Risky Behavior: Mediating the Effect of Parent–Adolescent Conflict and Violent Tendencies" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 11: 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111058

APA StyleÖzdemir Bişkin, S. (2024). Childhood Maltreatment and Adolescent Risky Behavior: Mediating the Effect of Parent–Adolescent Conflict and Violent Tendencies. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111058