Social Connectedness in Schizotypy: The Role of Cognitive and Affective Empathy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Subtypes and Dimensions of Schizotypy

2.2. Psychopathology, Complex Cognition, and Social Connectedness

2.3. Gaps in Current Understanding of Empathy and Social Functioning

2.4. Developmental Factors: Alexithymia and Distress Tolerance

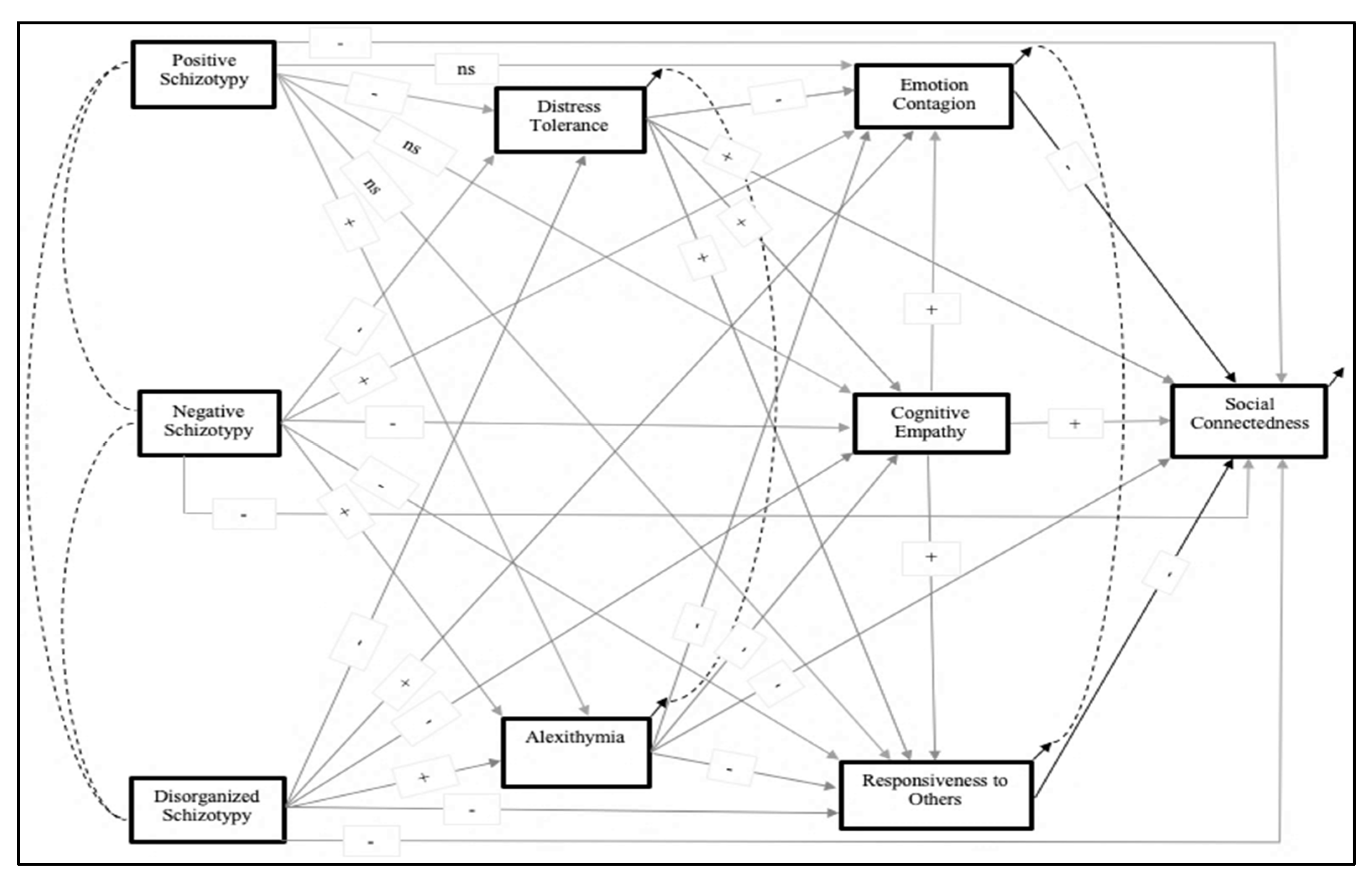

2.5. Study Aims and Hypotheses

- Higher positive, negative, and disorganized schizotypy are all associated with poorer social connectedness.

- Higher positive, negative, and disorganized schizotypy are all associated with poorer distress tolerance.

- A.

- Poorer distress tolerance is associated with poorer perspective taking and less responsiveness to others, but with higher emotion contagion.

- Higher positive, negative, and disorganized schizotypy are all associated with higher levels of alexithymia.

- A.

- Higher levels of alexithymia are associated with worse performance on perspective taking, less responsiveness to others, and less emotion contagion.

- Higher negative and disorganized schizotypy are associated with poorer self-reported cognitive empathy (when cognitive empathy is comprised of both perspective taking and efforts to represent others’ mental states).

- A.

- The relationship between high negative/disorganized schizotypy and lower cognitive empathy is mediated by decreased levels of distress tolerance and increased levels of alexithymia.

- Higher negative and disorganized schizotypy are associated with greater emotion contagion.

- A.

- The relationship between high negative/disorganized schizotypy and greater emotion contagion is mediated by distress tolerance, alexithymia, and cognitive empathy.

- Higher negative and disorganized schizotypy is associated with deficits in general responsiveness to others’ feelings.

- A.

- The relationship between high negative/disorganized schizotypy and lower emotional responsivity is mediated by distress tolerance, alexithymia, and cognitive empathy.

- The relationship between negative/disorganized schizotypy and social connectedness is mediated by abnormalities in cognitive empathy, emotion contagion, and responsiveness to others’ feelings.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedures

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Segrin, C.; Domschke, T. Social support, loneliness, recuperative processes, and their direct and indirect effects on health. Health Commun. 2011, 26, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drapalski, A.L.; Lucksted, A.; Perrin, P.B.; Aakre, J.M.; Brown, C.H.; DeForge, B.R.; Boyd, J.E. A model of internalized stigma and its effects on people with mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, A.; Bowen, L.; Gustavsson, E.; Håkansson, S.; Littleton, N.; McCormick, J.; Mulligan, H. Maintenance and development of social connection by people with long-term conditions: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkema, K.J.; Kalichman, S.C.; Hoffmann, R.; Koob, J.J.; Kelly, J.A.; Heckman, T.G. Coping strategies and emotional wellbeing among HIV-infected men and women experiencing AIDS-related bereavement. Aids Care 2000, 12, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.; Choi, S.W.; Victorson, D.; Bode, R.; Peterman, A.; Heinemann, A.; Cella, D. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: The development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. The major health implications of social connection. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 30, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Draper, M.; Lee, S. Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: Testing a mediator model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2001, 48, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzenweger, M.F. Schizotypy: An Organizing Framework for Schizophrenia Research. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, D.R.; Futterman, S.E.; McMaster, A.; Siever, L.J. Schizotypal personality disorder: A current review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrantes-Vidal, N.; Grant, P.; Kwapil, T.R. The role of schizotypy in the study of the etiology of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41 (Suppl. 2), S408–S416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.S.; Mohr, C.; Ettinger, U.; Chan, R.C.; Park, S. Schizotypy as an organizing framework for social and affective sciences. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41 (Suppl. 2), S427–S435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghvinian, M.; Sergi, M.J. Social functioning impairments in schizotypy when social cognition and neurocognition are not impaired. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2018, 14, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellack, A.S.; Morrison, R.L.; Wixted, J.T.; Mueser, K.T. An analysis of social competence in schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 1990, 156, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addington, J. The prodromal stage of psychotic illness: Observation, detection or intervention? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003, 28, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johns, L.C.; van Os, J. The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 1125–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, D.L.; Waldheter, E.J.; Perkins, D.O.; Mueser, K.T.; Lieberman, J.A. Psychosocial treatment for first-episode psychosis: A research update. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 2220–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Galling, B.; Pawar, A.; Krivko, A.; Bonetto, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Craig, T.J.; Nordentoft, M.; Srihari, V.H.; Guloksuz, S.; et al. Comparison of Early Intervention Services vs Treatment as Usual for Early-Phase Psychosis: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.A.; Hoffman, L.; Spaulding, W.D. Schizotypal personality questionnaire—Brief revised (updated): An update of norms, factor structure, and item content in a large non-clinical young adult sample. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 238, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwapil, T.; Gross, G.; Silvia, P.; Raulin, M.; Barrantes-Vidal, N. Development and psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Schizotypy Scale: A new measure for assessing positive, negative, and disorganized schizotypy. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 193, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwapil, T.R.; Barrantes-Vidal, N. Schizotypy: Looking back and moving forward. Schizophr. Bull. 2015, 41 (Suppl. 2), S366–S373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decety, J.; Moriguchi, Y. The empathic brain and its dysfunction in psychiatric populations: Implications for intervention across different clinical conditions. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2007, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfils, K.A.; Lysaker, P.H.; Minor, K.S.; Salyers, M.P. Affective empathy in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 175, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, C.H. Empathy, warmth, and genuineness in psychotherapy: A review of reviews. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1984, 21, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.; Barley, D. Research summary of the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2001, 38, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, K.; Segal, E. Importance of empathy for social work practice: Integrating new science. Soc. Work 2011, 56, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, H.; Kraft-Todd, G. EMPATHY: A tool to enhance nonverbal communication between clinicians and their patients. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.; Bailey, P.; Rendell, P. Empathy, social functioning and schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 160, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Neumann, D.L.; Shum, D.H.; Liu, W.H.; Shi, H.S.; Yan, C.; Lui, S.S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Cheung, E.F.; et al. Cognitive empathy partially mediates the association between negative schizotypy traits and social functioning. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedwell, J.S.; Compton, M.T.; Jentsch, F.G.; Deptula, A.E.; Goulding, S.M.; Tone, E.B. Latent factor modeling of four schizotypy dimensions with theory of mind and empathy. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakkar, K.N.; Park, S. Empathy, schizotypy, and visuospatial transformations. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 2010, 15, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kállai, J.; Rózsa, S.; Hupuczi, E.; Hargitai, R.; Birkás, B.; Hartung, I.; Martin, L.; Herold, R.; Simon, M. Cognitive fusion and affective isolation: Blurred self-concept and empathy deficits in schizotypy. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, F.; Madle, R.A. Empathy: Historic and current conceptualizations, measurement, and a cognitive theoretical perspective. Hum. Dev. 1975, 18, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S. The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Cognitive empathy and emotional empathy in human behavior and evolution. Psychol. Rec. 2006, 56, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Jackson, P.L. A social-neuroscience perspective on empathy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.J. Responding to the emotions of others: Dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Conscious. Cogn. 2005, 14, 698–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinella, M. Prefrontal substrates of empathy: Psychometric evidence in a community sample. Biol. Psychol. 2005, 70, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat. Sel. Doc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reniers, R.; Corcoran, R.; Drake, R.; Shryane, N.; Völlm, B. The QCAE: A Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. J. Personal. Assess. 2011, 93, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuler, M.; Mohnke, S.; Walter, H. Emotional Mimicry in Social Context; Hess, U., Fischer, A.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Decety, J.; Jackson, P.L. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 2004, 3, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derntl, B.; Finkelmeyer, A.; Toygar, T.K.; Hülsmann, A.; Schneider, F.; Falkenberg, D.I.; Habel, U. Generalized deficit in all core components of empathy in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 108, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premack, D.; Woodruff, G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav. Brain Sci. 1978, 1, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byom, L.J.; Mutlu, B. Theory of mind: Mechanisms, methods, and new directions. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, M.D.; Farrar, M.J. Conflicting emotions: The connection between affective perspective taking and theory of mind. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 24, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, E.; Yucel, M.; Pantelis, C. Theory of mind impairment in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derntl, B.; Finkelmeyer, A.; Voss, B.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Kellermann, T.; Schneider, F.; Habel, U. Neural correlates of the core facets of empathy in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 136, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbera, S.; Wexler, B.E.; Ikezawa, S.; Bell, M.D. Factor structure of social cognition in schizophrenia: Is empathy preserved? Schizophr. Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 409205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savla, G.N.; Vella, L.; Armstrong, C.C.; Penn, D.L.; Twamley, E.W. Deficits in domains of social cognition in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Schizophr. Bull. 2013, 39, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.J.; Horan, W.P.; Cobia, D.J.; Karpouzian, T.M.; Fox, J.M.; Reilly, J.L.; Breiter, H.C. Performance-based empathy mediates the influence of working memory on social competence in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2014, 40, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, W.P.; Reise, S.P.; Kern, R.S.; Lee, J.; Penn, D.L.; Green, M.F. Structure and correlates of self-reported empathy in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 66, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Modi, S.; Goyal, S.; Kaur, P.; Singh, N.; Bhatia, T.; Deshpande, S.N.; Khushu, S. Functional and structural abnormalities associated with empathy in patients with schizophrenia: An fMRI and VBM study. J. Biosci. 2015, 40, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peveretou, F.; Radke, S.; Derntl, B.; Habel, U. A Short Empathy Paradigm to Assess Empathic Deficits in Schizophrenia. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, T.; Horan, W.; Ginger, E.; Martinovich, Z.; Pinkham, A.; Smith, M. Cognitive empathy contributes to poor social functioning in schizophrenia: Evidence from a new self-report measure of cognitive and affective empathy. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondra, J.D.; Ellsworth, P.C. An appraisal theory of empathy and other vicarious emotional experiences. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 122, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Rapson, R.L. Emotional contagion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1993, 2, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englis, B.G.; Vaughan, K.B.; Lanzetta, J.T. Conditioning of counter-empathetic emotional responses. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 18, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnby-Borgström, M.; Jönsson, P.; Svensson, O. Emotional empathy as related to mimicry reactions at different levels of information processing. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2003, 27, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, S. A perception-action model for empathy. In Empathy in Mental Illness; Farrow, T., Woodruff, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 428–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, F.B.M. Putting the altruism back into altruism: The evolution of empathy. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.J.; Horan, W.P.; Karpouzian, T.M.; Abram, S.V.; Cobia, D.J.; Csernansky, J.G. Self-reported empathy deficits are uniquely associated with poor functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 137, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappelli, J.; Pocivavsek, A.; Nugent, K.L.; Notarangelo, F.M.; Kochunov, P.; Rowland, L.M.; Schwarcz, R.; Hong, L.E. Stress-induced increase in kynurenic acid as a potential biomarker for patients with schizophrenia and distress intolerance. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugent, K.L.; Chiappelli, J.; Rowland, L.M.; Daughters, S.B.; Hong, L.E. Distress intolerance and clinical functioning in persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoid, D.; Pan, D.N.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Implicit emotion regulation deficits in individuals with high schizotypal traits: An ERP study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, R.V.; Benson, T.L.; Park, S. Investigating the role of alexithymia on the empathic deficits found in schizotypy and autism spectrum traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 77, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, C.; Siebel-Jurges, U.; Barnow, S.; Grabe, H.J.; Freyberger, H.J. Alexithymia and interpersonal problems. Psychother. Psychosom. 2005, 74, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, G.; Semerari, A.; Lysaker, P.H.; Dimaggio, G.; Conti, L.; D’Angerio, S.; Procacci, M.; Popolo, R.; Carcione, A. Alexithymia in personality disorders: Correlations with symptoms and interpersonal functioning. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 190, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghers, J.P.; McCleery, A.; Docherty, N.M. Schizotypy, alexithymia, and socioemotional outcomes. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2011, 199, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedro, A.; Kokoszka, A.; Popiel, A.; Narkiewicz-Jodko, W. Alexithymia in schizophrenia: An exploratory study. Psychol. Rep. 2001, 89, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van’t Wout, M.; Aleman, A.; Bermond, B.; Kahn, R.S. No words for feelings: Alexithymia in schizophrenia patients and first-degree relatives. Compr. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.X.; Shi, H.S.; Ni, K.; Wang, Y.; Cheung, E.; Chan, R. Exploring the links between alexithymia, empathy and schizotypy in college students using network analysis. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 1–9, advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonason, P.K.; Krause, L. The emotional deficits associated with the dark triad traits: Cognitive empathy, affective empathy, and alexithymia. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, Y.; Decety, J.; Ohnishi, T.; Maeda, M.; Mori, T.; Nemoto, K.; Matsuda, H.; Komaki, G. Empathy and judging other’s pain: An fMRI study of alexithymia. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 17, 2223–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, M.; Sailer, M.; Fischer, F. Knowledge as a formative construct: A good alpha is not always better. New Ideas Psychol. 2021, 60, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, D.; Farrington, D.P. Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré, A.; Stefaniak, N.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Bensalah, L.; Besche-Richard, C. The Basic Empathy Scale in adults (BES-A): Factor structure of a revised form. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, D.L.; Chan, R.C.K.; Boyle, G.J.; Wang, Y.; Westbury, H.R. Measures of empathy: Self-report, behavioral, and neuroscientific approaches. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Constructs; Boyle, G.J., Saklofske, D.H., Matthews, G., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 257–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, J.; Gaher, R. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motiv. Emot. 2005, 29, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, R.M.; Taylor, G.J.; Parker, J.D. The Twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale—II. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, W. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlow-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 38, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Agler, R.; DeBoeck, P. On the interpretation and use of mediation: Multiple perspectives on mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhomba, M.; Chugani, C.D.; Uliaszek, A.A.; Kannan, D. Distress tolerance skills for college students: A pilot investigation of a brief DBT group skills training program. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2017, 31, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeifman, R.J.; Boritz, T.; Barnhart, R.; Labrish, C.; McMain, S.F. The independent roles of mindfulness and distress tolerance in treatment outcomes in dialectical behavior therapy skills training. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 2020, 11, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, L.; Nguyen, Q.A.; Roettger, C.; Dixon, K.; Offenbächer, M.; Kohls, N.; Hirsch, J.; Sirois, F. Effectiveness of progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing, and guided imagery in promoting psychological and physiological states of relaxation. Evid.-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2021, eCAM2021, 5924040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.; Franklin, J. Skills-based treatment for alexithymia: An exploratory case series. Behav. Change 2002, 19, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, R.F.; Hayden, E.W.; Halter, M.J.; Williams, C.M. The efficacy of alexithymia reduction treatment: A pilot study. J. Men’s Stud. 2009, 17, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Grossman, P.; Hinton, D.E. Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Cella, M.; Csipke, E.; Heriot-Maitland, C.; Gibbs, C.; Wykes, T. Tackling Social Cognition in Schizophrenia: A Randomized Feasibility Trial. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2016, 44, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, H.; Stice, E.; Kazdin, A.; Offord, D.; Kupfer, D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, Moderators, and Independent, Overlapping, and Proxy Risk Factors. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E. Commentary: Mediation analysis, causal process, and cross-sectional data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cave, L.; Cooper, M.; Zubrick, S.; Shepherd, C. Racial discrimination and child and adolescent health in longitudinal studies: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 250, 112864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, P.A.; Walker, E.F. Vulnerability to schizophrenia in childhood and adolescence. In Vulnerability to psychopathology: Risk across the lifespan; Ingram, R.E., Price, J.M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 363–388. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, I.E.; Bearden, C.E.; van Dellen, E.; Breetvelt, E.J.; Duijff, S.N.; Maijer, K.; van Amelsvoort, T.; de Haan, L.; Gur, R.E.; Arango, C.; et al. Early interventions in risk groups for schizophrenia: What are we waiting for? NPJ Schizophr. 2016, 2, 16003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlati, S.; Deste, G.; De Peri, L.; Ariu, C.; Vita, A. Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: Current status and future perspectives. Schizophr. Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 156084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehl, P.E. Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. Am. Psychol. 1962, 17, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N. The dimensional view of personality disorders: A review of the taxometric evidence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 23, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, E.A.; Epifani, A. From schizotypal personality to schizotypal dimensions: A two-step taxometric study. Clin. Neuropsychiatry J. Treat. Eval. 2012, 9, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, O.J. The duality of schizotypy: Is it both dimensional and categorical? Front. Psychiatry 2014, 5, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, P.; Green, M.J.; Mason, O.J. Models of schizotypy: The importance of conceptual clarity. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44 (Suppl. 2), S556–S563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex at Birth | ||

| Male | 158 | 19.2 |

| Female | 664 | 80.6 |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Male | 155 | 18.8 |

| Female | 654 | 79.4 |

| Genderfluid | 6 | 0.7 |

| Transgender (Female to Male) | 3 | 0.4 |

| Other | 6 | 0.7 |

| Race | ||

| White | 641 | 77.8 |

| Black | 42 | 5.1 |

| Asian | 73 | 8.9 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 5 | 0.6 |

| Pacific Islander | 2 | 0.2 |

| Multiracial | 36 | 4.4 |

| Other | 22 | 2.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx/Spanish | 89 | 10.8 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married or Domestic Partnership | 10 | 1.2 |

| Single/Unmarried | 812 | 98.5 |

| M | SD | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSS | |||

| Positive | 3.16 | 4.252 | 824 |

| Negative | 3.25 | 3.945 | 824 |

| Disorganized | 3.66 | 5.461 | 824 |

| QCAE | |||

| Cognitive Empathy | 61.39 | 8.284 | 824 |

| Emotion Contagion | 12.26 | 2.280 | 824 |

| Responsiveness to Others | 21.068 | 3.468 | 824 |

| DTS | 48.98 | 12.297 | 823 |

| TAS-20 | 47.23 | 12.046 | 822 |

| SCS-R | 87.04 | 16.908 | 822 |

| MCSD-SF-C | 6.49 | 2.747 | 822 |

| CECQ | 8.57 | 4.874 | 822 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MSS-Positive | ||||||||

| 2. MSS-Negative | 0.431 * | |||||||

| 3. MSS-Disorganized | 0.610 * | 0.490 * | ||||||

| 4. QCAE-Cognitive Empathy | −0.112 * | −0.322 * | −0.184 * | |||||

| 5. QCAE-Emotion Contagion | 0.114 * | −0.140 * | 0.132 * | 0.162 * | ||||

| 6. QCAE-Responsiveness to Others | 0.046 | −0.232 * | 0.038 | 0.308 * | 0.418 * | |||

| 7. DTS | −0.267 * | −0.155 * | −0.353 * | 0.152 * | −0.384 * | −0.205 * | ||

| 8. TAS-20 | 0.372 * | 0.404 * | 0.455 * | −0.381 * | 0.060 | −0.154 * | −0.436 * | |

| 9. SCS-R | −0.389 * | −0.614 * | −0.501 * | 0.419 * | −0.046 | 0.106 * | 0.408 * | −0.588 * |

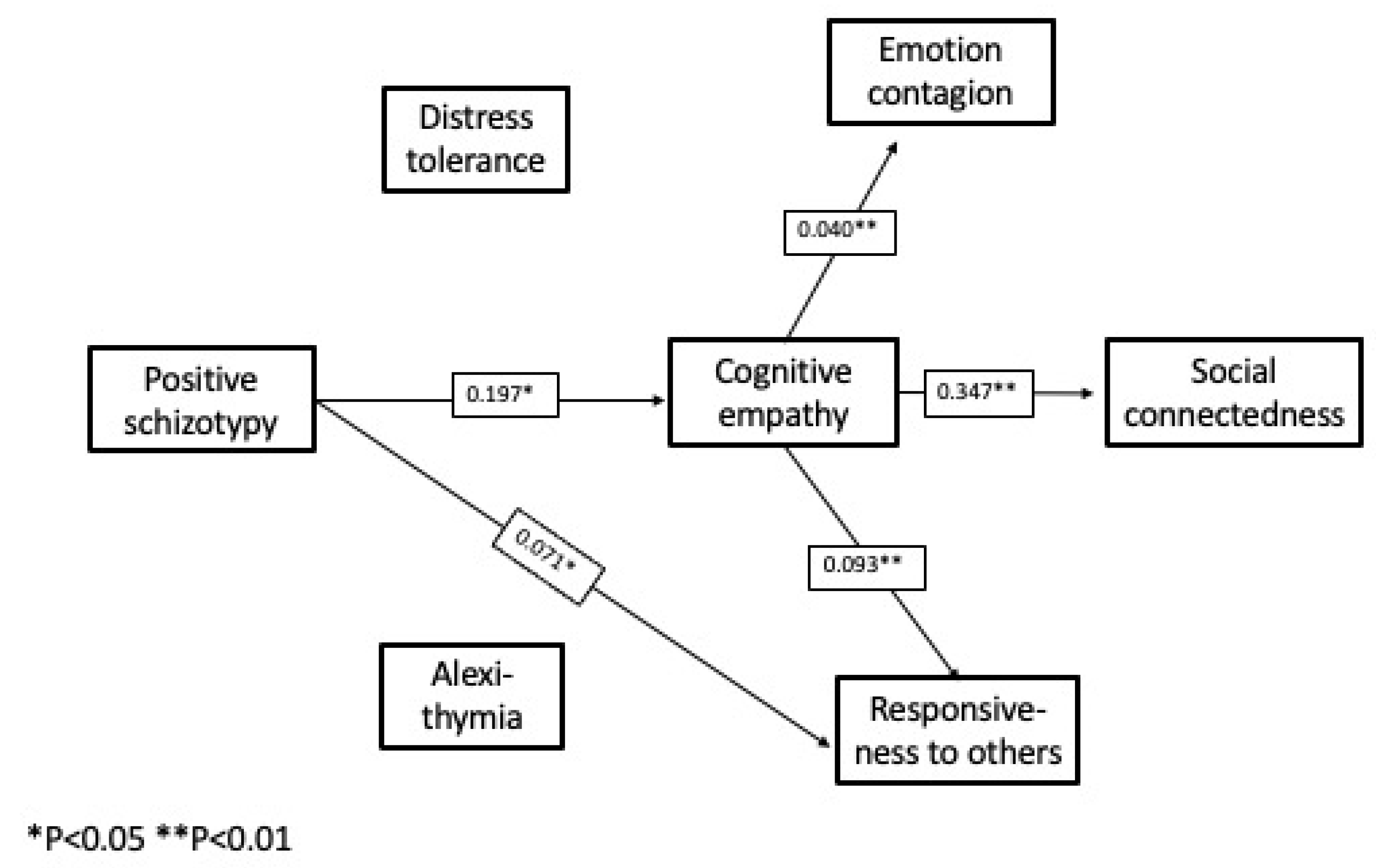

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Mediating Variable(s) | Path Coefficient | 95% CI * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive schizotypy | Emotion contagion | Cognitive empathy | 0.008 | 0.002, 0.018 |

| Positive schizotypy | Responsiveness to others | Cognitive empathy | 0.018 | 0.004, 0.037 |

| Positive schizotypy | Social connectedness | Cognitive empathy | 0.068 | 0.015, 0.136 |

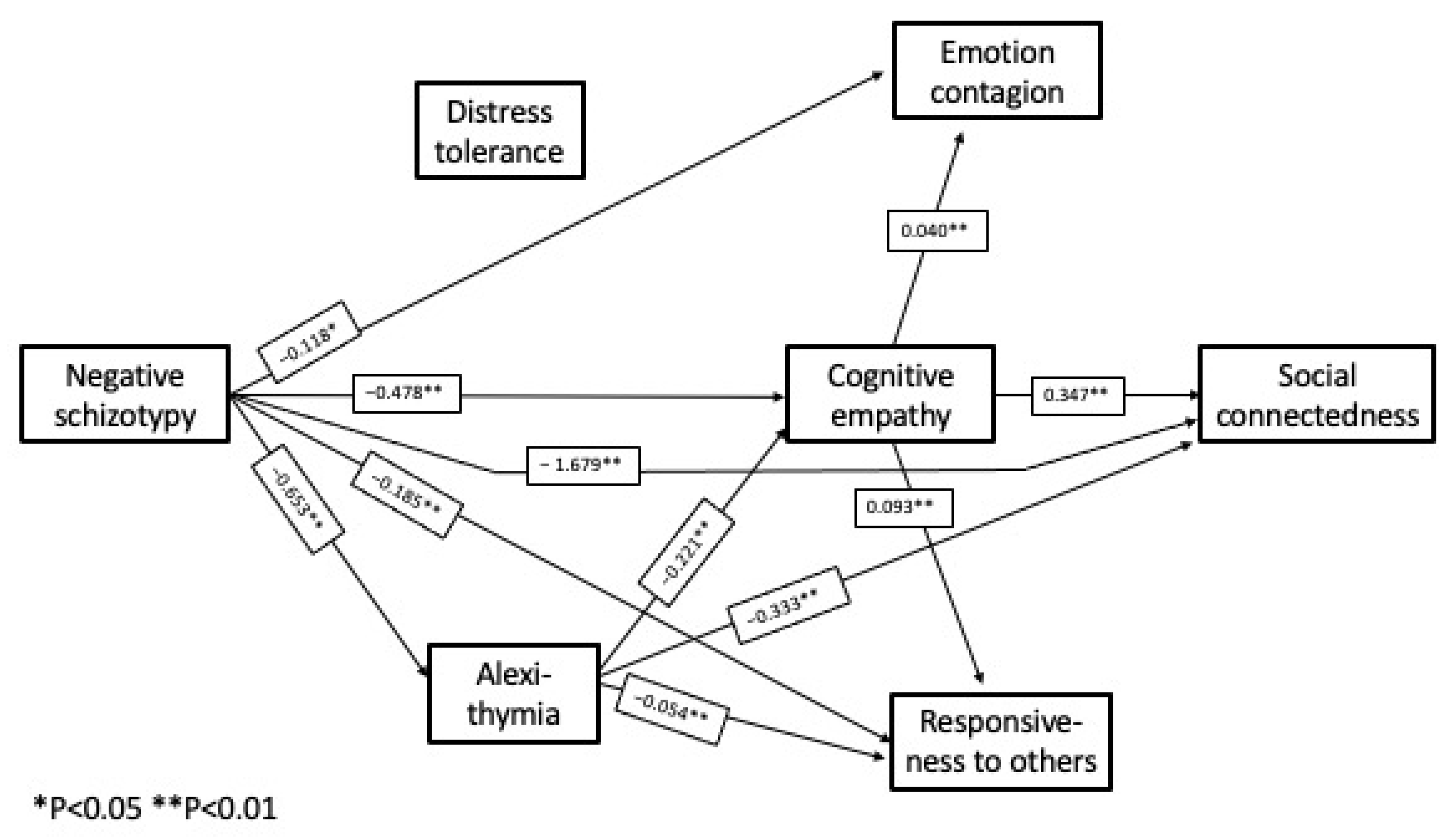

| Negative schizotypy | Cognitive empathy | Alexithymia | −0.144 | −0.212, −0.091 |

| Negative schizotypy | Emotion contagion | Cognitive empathy | −0.019 | −0.036, −0.008 |

| Negative schizotypy | Emotion contagion | Alexithymia, Cognitive empathy | −0.006 | −0.011, −0.003 |

| Negative schizotypy | Responsiveness to others | Alexithymia | −0.035 | −0.059, −0.018 |

| Negative schizotypy | Responsiveness to others | Cognitive empathy | −0.044 | −0.070, −0.025 |

| Negative schizotypy | Responsiveness to others | Alexithymia, Cognitive empathy | −0.013 | −0.022, −0.008 |

| Negative schizotypy | Social connectedness | Alexithymia | −0.217 | −0.338, −0.128 |

| Negative schizotypy | Social connectedness | Cognitive empathy | −0.166 | −0.259, −0.099 |

| Negative schizotypy | Social connectedness | Alexithymia, Cognitive empathy | −0.050 | −0.084, −0.029 |

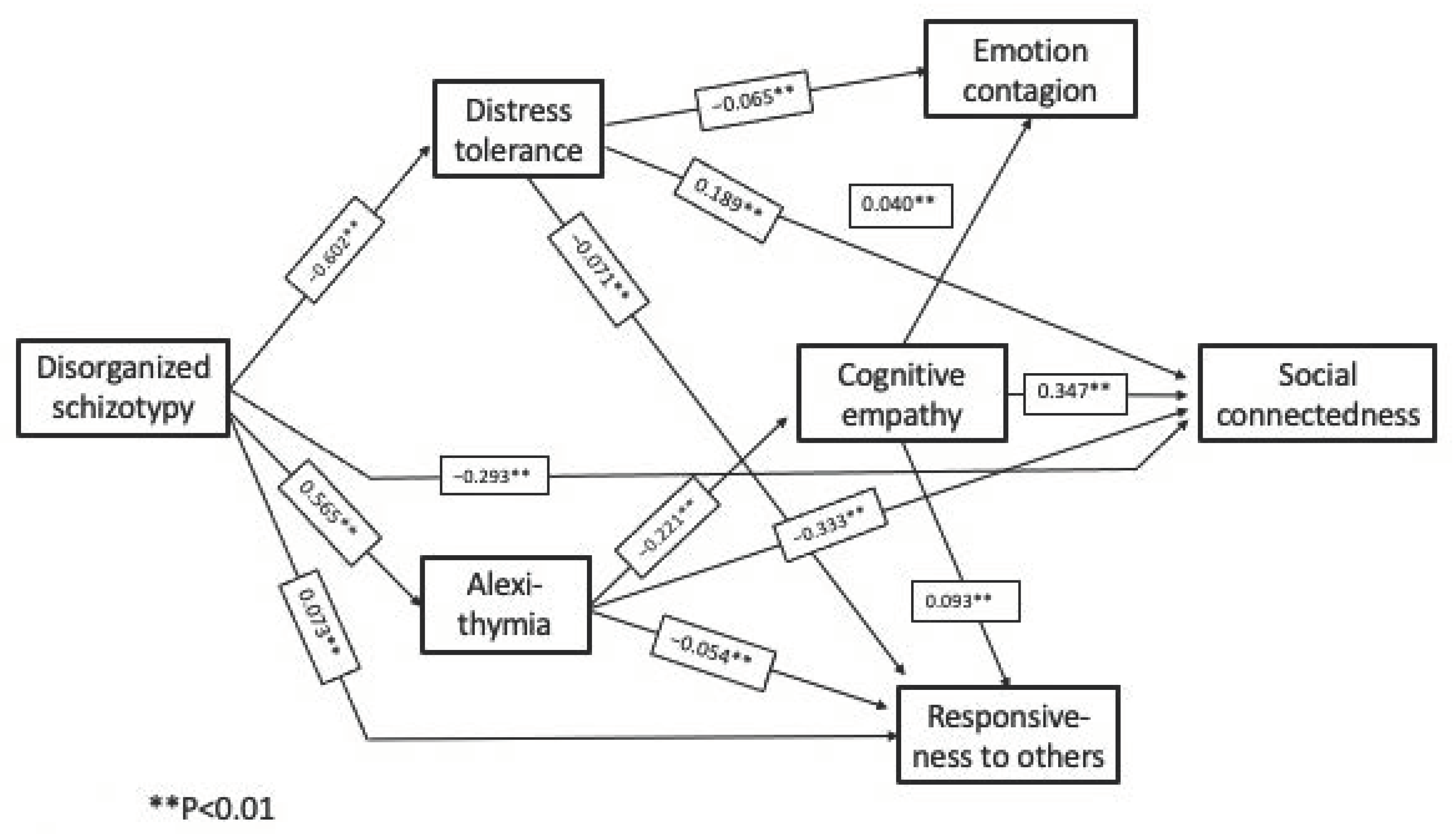

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Cognitive empathy | Alexithymia | −0.125 | −0.177, −0.085 |

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Emotion contagion | Distress tolerance | 0.039 | 0.026, 0.055 |

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Emotion contagion | Alexithymia, Cognitive empathy | −0.005 | −0.009, −0.002 |

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Responsiveness to others | Distress tolerance | 0.043 | 0.027, 0.063 |

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Responsiveness to others | Alexithymia | −0.030 | −0.049, −0.016 |

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Responsiveness to others | Alexithymia, Cognitive empathy | −0.012 | −0.018, −0.007 |

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Social connectedness | Alexithymia | −0.188 | −0.271, −0.121 |

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Social connectedness | Distress tolerance | −0.114 | −0.184, −0.063 |

| Disorganized Schizotypy | Social connectedness | Alexithymia, Cognitive empathy | −0.043 | −0.070, −0.026 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stinson, J.; Wolfe, R.; Spaulding, W. Social Connectedness in Schizotypy: The Role of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080253

Stinson J, Wolfe R, Spaulding W. Social Connectedness in Schizotypy: The Role of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(8):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080253

Chicago/Turabian StyleStinson, Jessica, Rebecca Wolfe, and Will Spaulding. 2022. "Social Connectedness in Schizotypy: The Role of Cognitive and Affective Empathy" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 8: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080253

APA StyleStinson, J., Wolfe, R., & Spaulding, W. (2022). Social Connectedness in Schizotypy: The Role of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. Behavioral Sciences, 12(8), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080253