Institutional Trust as a Protective Factor during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis and Descriptive Statistics

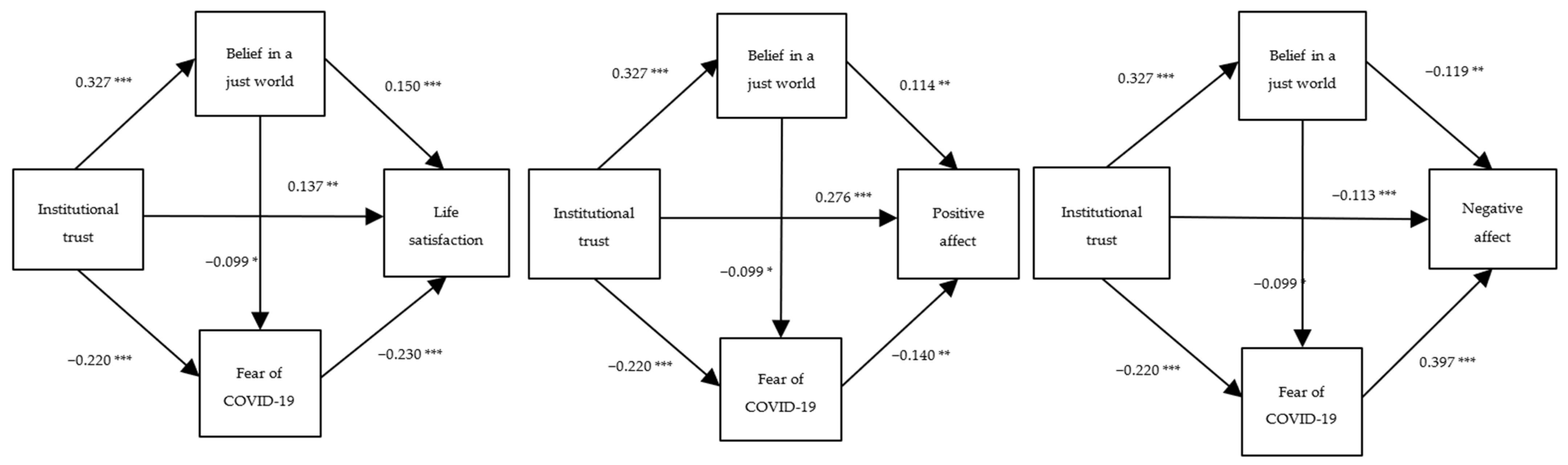

3.2. Serial Multiple Mediational Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duong, C.D. The impact of fear and anxiety of COVID-19 on life satisfaction: Psychological distress and sleep disturbance as mediators. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 178, 110869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Dong, Z.; Yan, R.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; Ma, J.; Zeng, Y. Psychological distress in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary development of an assessment scale. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Jobe, M.C.; Mathis, A.A.; Gibbons, J.A. Incremental validity of coronaphobia: Coronavirus anxiety explains depression, generalized anxiety, and death anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, M.; Tsuno, K.; Okawa, S.; Hori, A.; Tabuchi, T. Trust and well-being of postpartum women during the COVID-19 crisis: Depression and fear of COVID-19. SSM-Popul. Health. 2021, 15, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salfi, F.; Lauriola, M.; D’Atri, A.; Amicucci, G.; Viselli, L.; Tempesta, D.; Ferrara, M. Demographic, psychological, chronobiological, and work-related predictors of sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krautter, K.; Friese, M.; Hart, A.; Reis, D. No party no joy?—Changes in university students’ extraversion, neuroticism, and subjective well-being during two COVID-19 lockdowns. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reizer, A.; Geffen, L.; Koslowsky, M. Life under the COVID-19 lockdown: On the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and psychological distress. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy. 2021, 13, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotanda, H.; Miyawaki, A.; Tabuchi, T.; Tsugawa, Y. Association between trust in government and practice of preventive measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3471–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Subjective well-being and mental health during the pandemic outbreak: Exploring the role of institutional trust. Res. Aging 2022, 44, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciziceno, M.; Travaglino, G.A. Perceived corruption and individuals’ life satisfaction: The mediating role of institutional trust. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piumatti, G.; Magistro, D.; Zecca, M.; Esliger, D.W. The mediation effect of political interest on the connection between social trust and wellbeing among older adults. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 2376–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Belief in a just world mediates the relationship between institutional trust and life satisfaction among the elderly in China. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 83, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kim, D. Social Capital and Health; Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S.V., Kim, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, C. Social Capital and the Happiness of Nations: The Importance of Trust and Networks for Life Satisfaction in a Cross-National Perspective, 1st ed.; Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lindström, M. Social capital, anticipated ethnic discrimination and self-reported psychological health: A population-based study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Inoue, Y.; Shinozaki, T.; Saito, M.; Takagi, D.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N. Community social capital and depressive symptoms among older people in Japan: A multilevel longitudinal study. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Tang, N.; Zhen, D.; Wang, X.R.; Zhang, J.; Cheong, Y.; Zhu, Q. Need for cognitive closure and trust towards government predicting pandemic behavior and mental health: Comparing United States and China. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkus, I.M.; Dalbert, C.; Siegler, I.C. The importance of distinguishing the belief in a just world for self versus for others: Implications for psychological well-being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 22, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, I.; Vala, J. Belief in a Just World, Subjective Well-Being and Trust of Young Adult, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, K.; Glaser, D.; Dalbert, C. Mental health, occupational trust, and quality of working life: Does belief in a just world matter? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 1288–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.L.; Elder, T.; Gater, J.; Johnson, E. The association between adolescents’ beliefs in a just world and their attitudes to victims of bullying. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 80, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. Belief in a just world: Research progress over the past decade. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Yue, X.; Lu, S.; Yu, G.; Zhu, F. How belief in a just world benefits mental health: The effects of optimism and gatitude. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 126, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, M.L.K.; Harvey, A.J.; Callan, M.J. Beliefs in a just world, subjective well-being and attitudes towards refugees among refugee workers. Soc. Justice Res. 2014, 27, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.M.; Stoeber, J.; Kamble, S.V. Belief in a just world for oneself versus others, social goals, and subjective well-Being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 113, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, S. The effect of belief in a just world on adolescents’ subjective well-being: The chain mediating roles of resilience and self-esteem. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2016, 3, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Belief in a just world on psychological well-being among college students: The effect of trait empathy and altruistic behavior. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 25, 359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Zheng, M.; Bai, X. The impacts of a COVID-19 epidemic focus and general belief in a just world on individual emotions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-González, P.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Irurtia, M.J.; de Luis-García, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Asgari, N.; Teo, Y.Y.; Leung, G.M.; Oshitani, H.; Fukuda, K.; Cook, A.R.; Hsu, L.Y.; Shibuya, K.; Heymann, D. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020, 395, 848–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, H.; Long, Q.; Huang, G.; Huang, L.; Luo, S. Different roles of interpersonal trust and institutional trust in COVID-19 pandemic control. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 293, 114677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.; Wu, D.; Im, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Yang, Q. Stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences: The mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of psychological support. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liang, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhou, X.; Gao, R. The factor structure and rasch analysis of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) among Chinese students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 678979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Yu, W.; Guo, T.; Cao, Q.; Zheng, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Stubbs, B.; et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale among Chinese population. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, M.E. Self-compassion, intolerance of uncertainty, fear of COVID-19, and well-being: A serial mediation investigation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 177, 110824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, P.G.; Miller, M.K.; Kirshenbaum, J.M. Moral disengagement, locus of control, and belief in a just world: Individual differences relate to adherence to COVID-19 guidelines. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 182, 111069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, H.; Gan, Y. Belief in a just world when encountering the 5/12 Wenchuan earthquake. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.T.; Wang, L.; Zhou, M.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J. Belief in a just world and subjective well-being: Comparing disaster sites with normal areas. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 17, 579–587. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L. Seeking pleasure or growth? The mediating role of happiness motives in the longitudinal relationship between social mobility beliefs and well-being in college students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 184, 111170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Kong, F. Beneficial effects of hedonic and eudaimonic motivations on subjective well-being in adolescents: A two-wave cross-lagged analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, A.; Kaakinen, M.; Latikka, R.; Savolainen, I.; Savela, N.; Koivula, A. Regulation and trust: 3-month follow-up study on COVID-19 mortality in 25 European countries. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolini, D. COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: The role of social identification and social and political trust on well-being and distress. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.M.; Douglas, K.M.; Wilkin, K.; Elder, T.J.; Cole, J.M.; Stathi, S. Justice for whom, exactly? beliefs in justice for the self and various others. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Wu, Q.; Hao, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Alias, H.; Shen, M.; Hu, J.; Duan, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. The role of institutional trust in preventive practices and treatment-seeking intention during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak among residents in Hubei, China. Int. Health 2022, 14, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Institutional trust | 34.96 | 5.33 | −1.38 | 2.88 | |||||

| 2. Belief in a just world | 25.48 | 5.50 | −0.30 | 0.84 | 0.33 *** | ||||

| 3. Fear of COVID-19 | 20.03 | 7.30 | 0.21 | −0.62 | −0.26 *** | −0.16 *** | |||

| 4. Life satisfaction | 21.78 | 6.15 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.24 *** | 0.24 *** | −0.27 *** | ||

| 5. Positive affect | 32.46 | 6.58 | −0.27 | 1.37 | 0.34 *** | 0.23 *** | −0.22 *** | 0.47 *** | |

| 6. Negative affect | 27.50 | 8.62 | −0.01 | −0.23 | −0.26 *** | −0.22 *** | 0.44 *** | −0.09 ** | 0.011 |

| Path | Standardized Coefficient | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||

| Model 1 | |||

| Institutional trust → BJW → Life satisfaction | 0.049 | 0.022 | 0.080 |

| Institutional trust→ Fear of COVID-19 → Life satisfaction | 0.051 | 0.025 | 0.081 |

| Institutional trust → BJW → Fear of COVID-19 → Life satisfaction | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.014 |

| Total effect | 0.244 | 0.176 | 0.309 |

| Direct effect | 0.137 | 0.055 | 0.220 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.107 | 0.067 | 0.150 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Institutional trust → BJW → Positive affect | 0.037 | 0.012 | 0.066 |

| Institutional trust → Fear of COVID-19 → Positive affect | 0.031 | 0.011 | 0.057 |

| Institutional trust → BJW → Fear of COVID-19→ Positive affect | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.010 |

| Total effect | 0.349 | 0.277 | 0.422 |

| Direct effect | 0.276 | 0.187 | 0.365 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.073 | 0.040 | 0.111 |

| Model 3 | |||

| Institutional trust → BJW → Negative affect | −0.039 | −0.065 | −0.014 |

| Institutional trust → Fear of COVID-19 → Negative affect | −0.087 | −0.121 | −0.055 |

| Institutional trust → BJW → Fear of COVID-19 → Negative affect | −0.013 | −0.023 | −0.003 |

| Total effect | −0.252 | −0.326 | −0.172 |

| Direct effect | −0.113 | −0.185 | −0.048 |

| Total indirect effect | −0.139 | −0.180 | −0.098 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Jing, J.; Wang, E. Institutional Trust as a Protective Factor during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080252

Li S, Sun Y, Jing J, Wang E. Institutional Trust as a Protective Factor during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(8):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080252

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shuangshuang, Yijia Sun, Jiaqi Jing, and Enna Wang. 2022. "Institutional Trust as a Protective Factor during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 8: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080252

APA StyleLi, S., Sun, Y., Jing, J., & Wang, E. (2022). Institutional Trust as a Protective Factor during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Behavioral Sciences, 12(8), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080252