Obesogenic Dysregulation of Human Periprostatic Adipose Tissue Promotes the Viability of Prostate Cells and Reduces Their Sensitivity to Docetaxel and Cabazitaxel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Human Samples

2.3. Ex Vivo Culture of PPAT and TBT Treatment

2.4. Histological Analysis

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA)

2.6. Quantification of Extracellular Metabolites

2.7. Human Prostate Cell Lines

2.8. CM Assays and Chemotherapeutic Drug Treatments

2.9. Cell Viability Assays

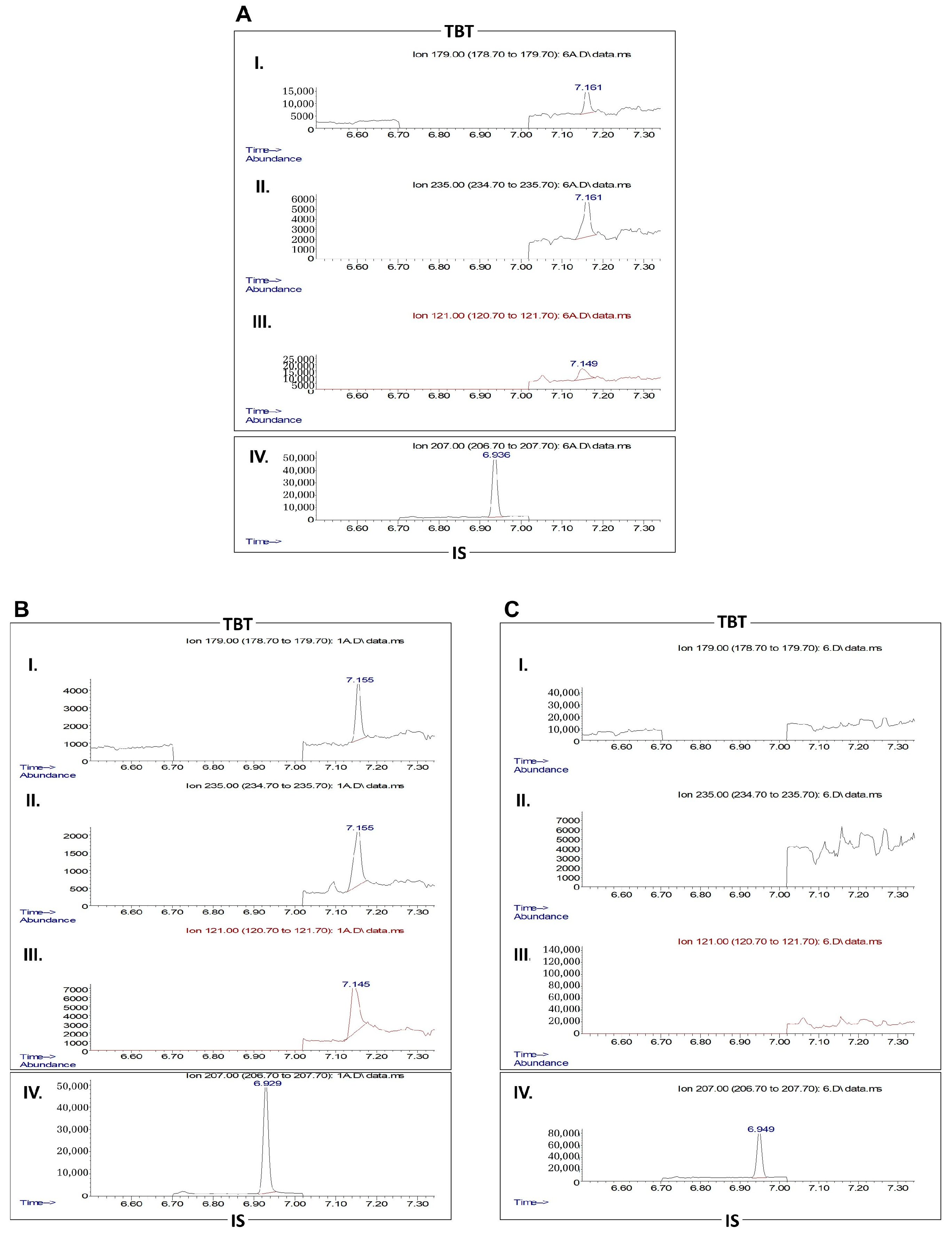

2.10. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

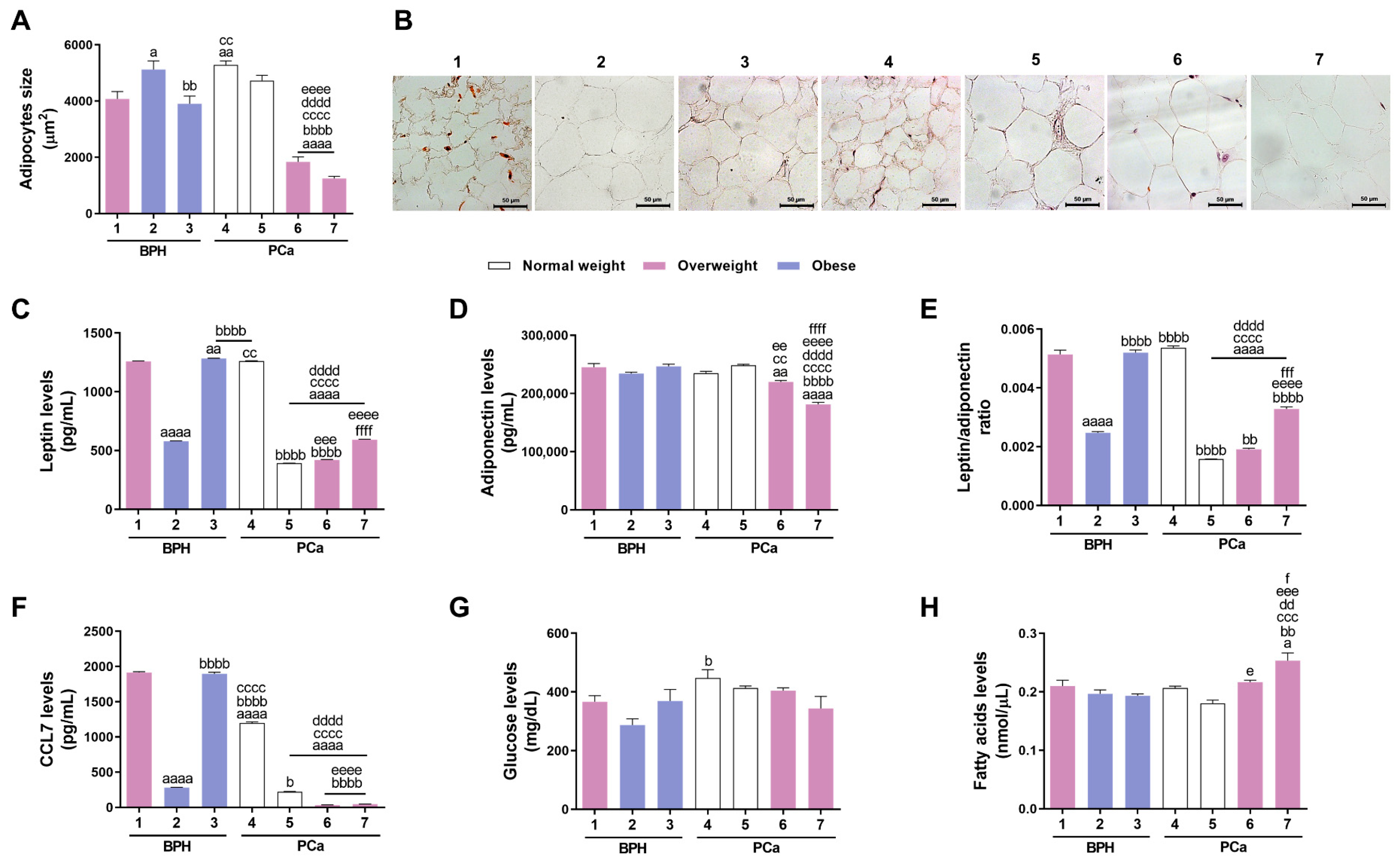

3.1. Characterisation of PPAT Morphology and Secretome

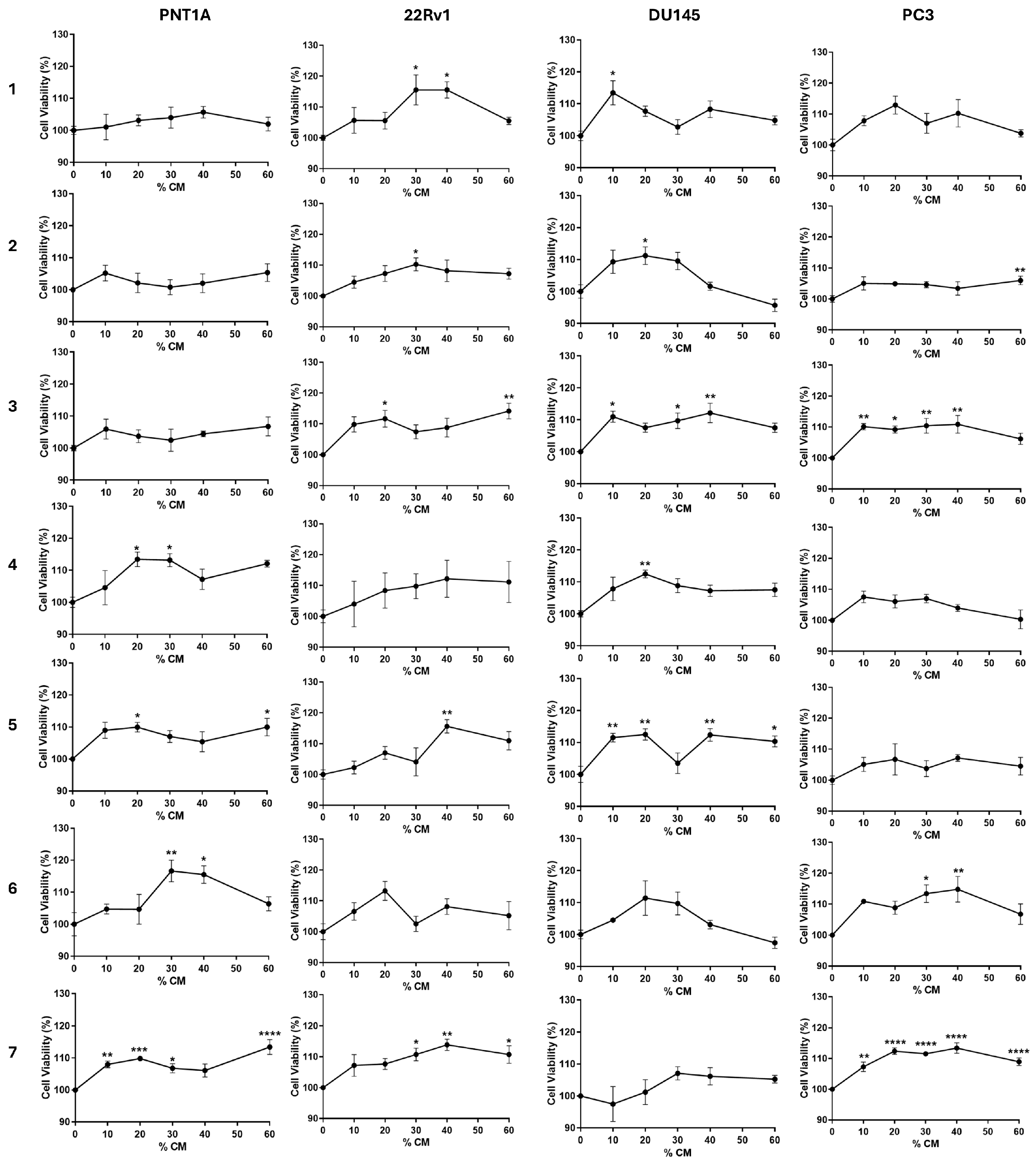

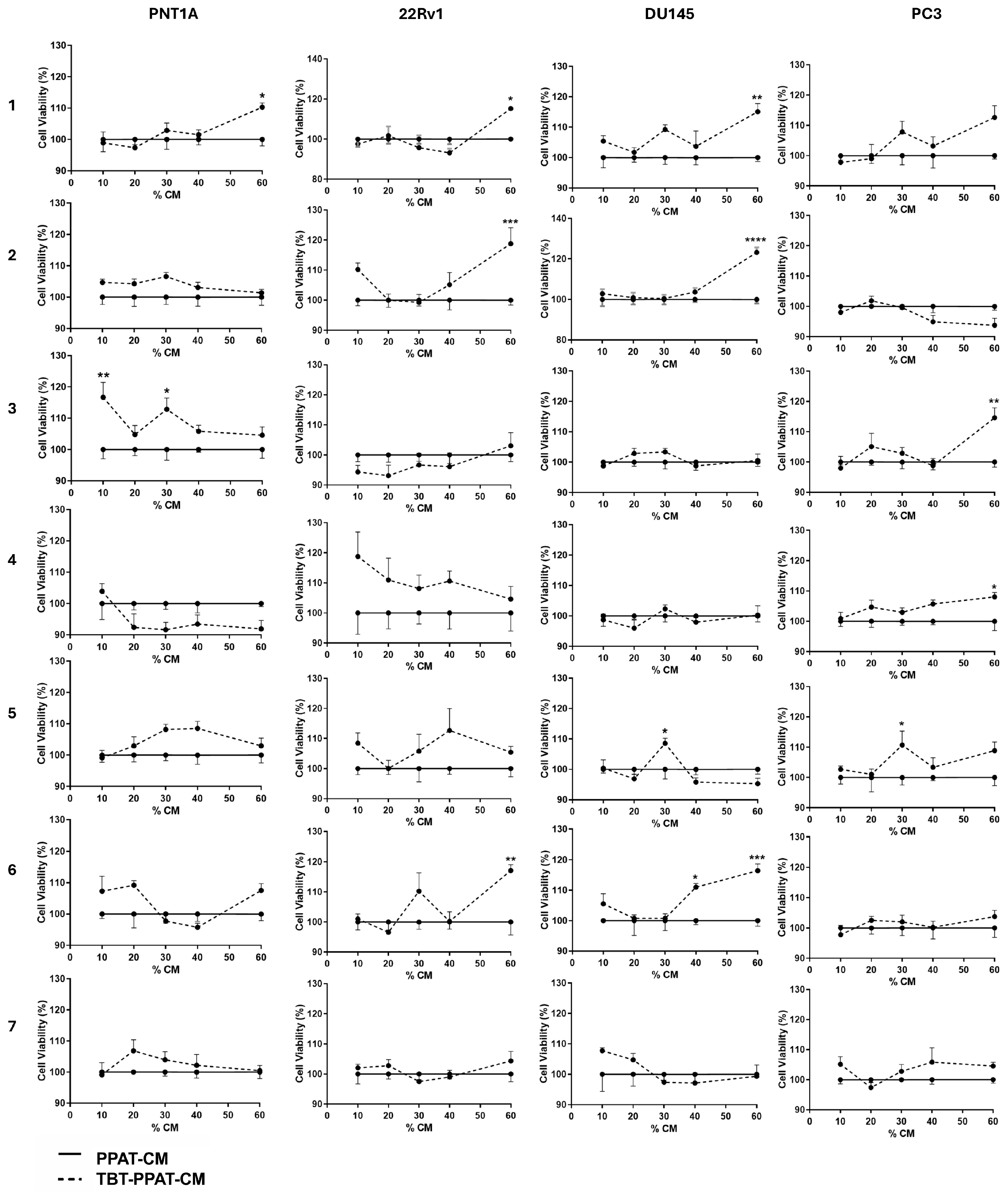

3.2. PPAT Secretome Slightly Increases Prostate Cell Viability

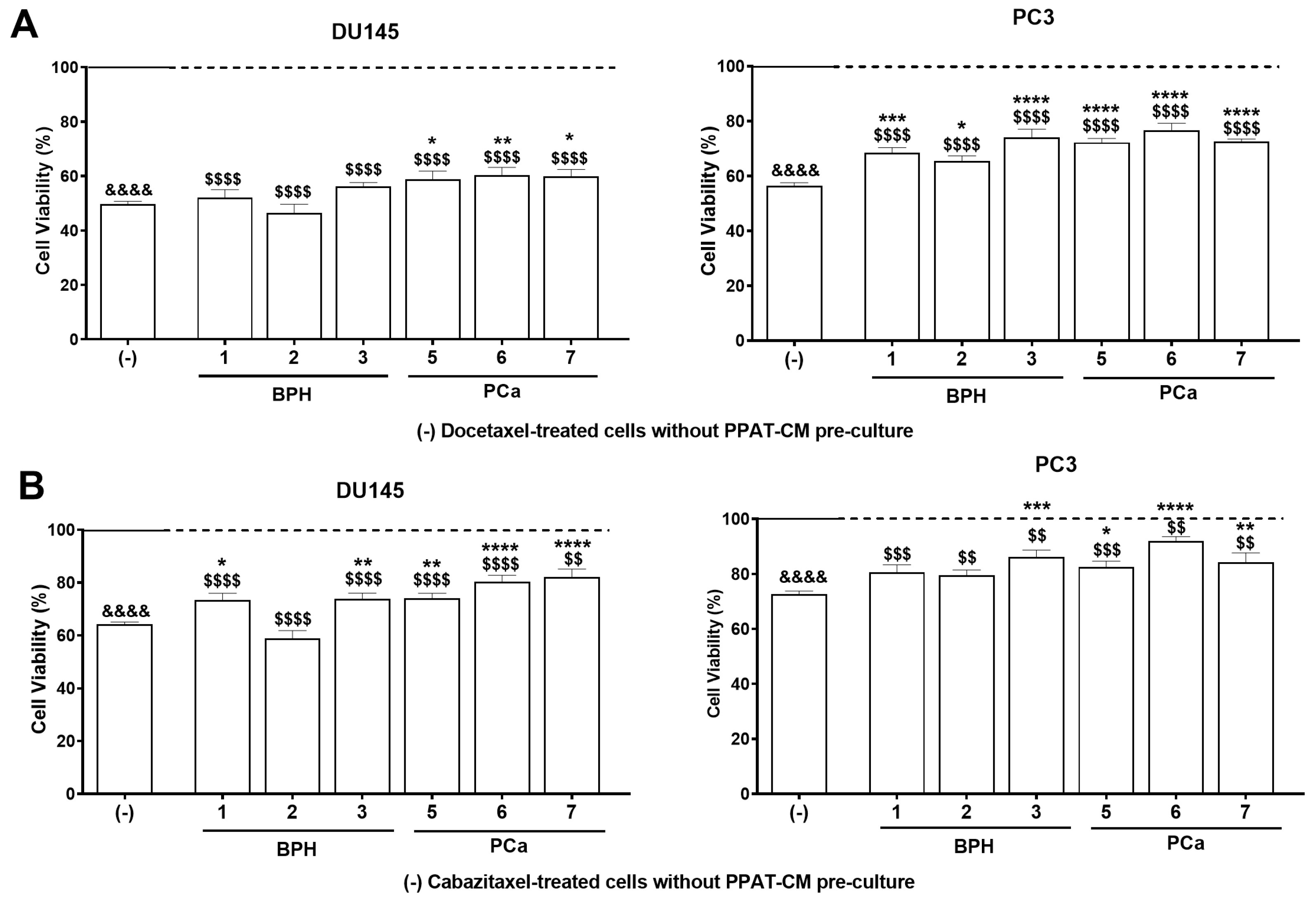

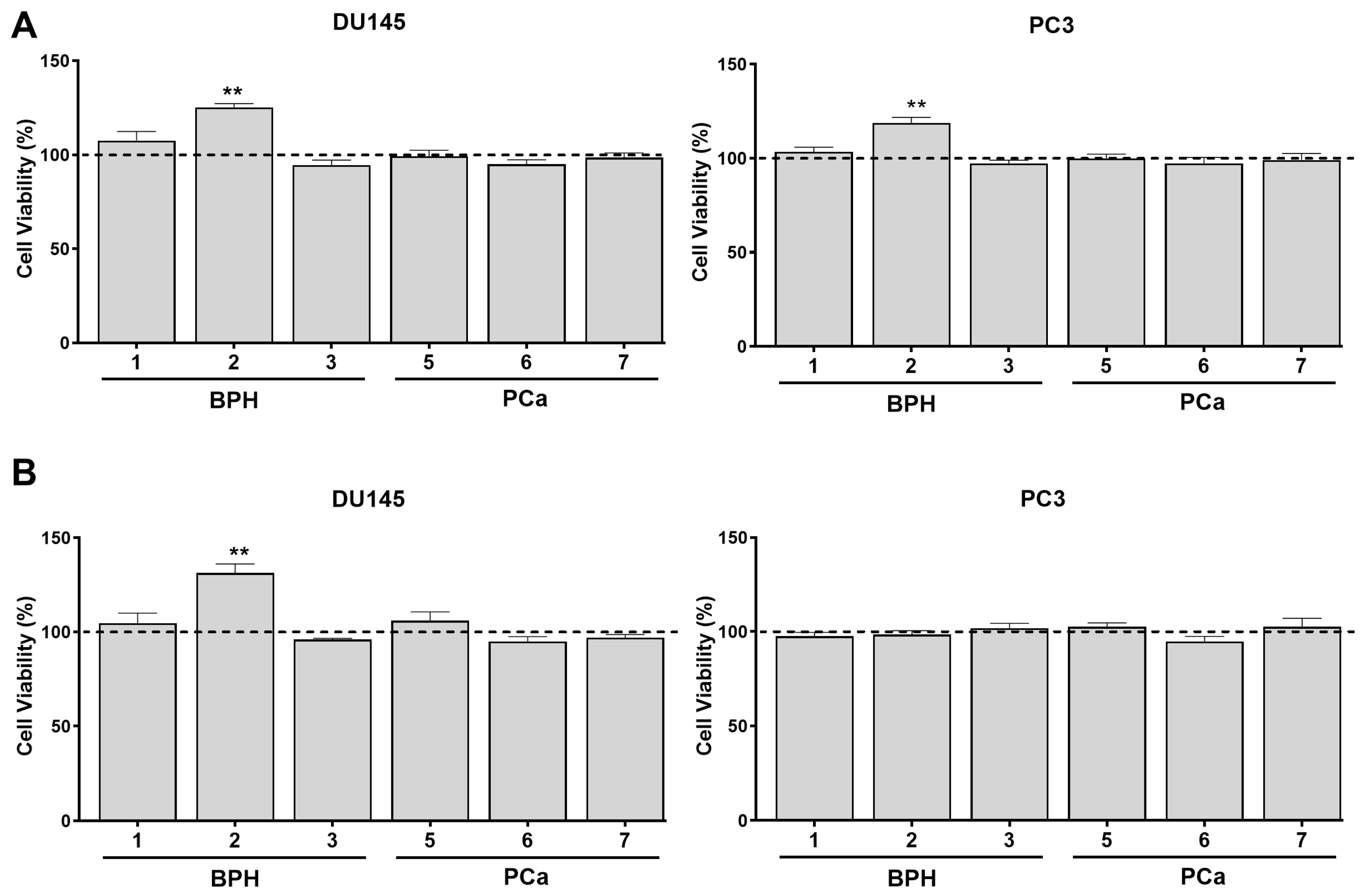

3.3. PPAT Secretome Reduced the Sensitivity of PCa Cells to Docetaxel and Cabazitaxel

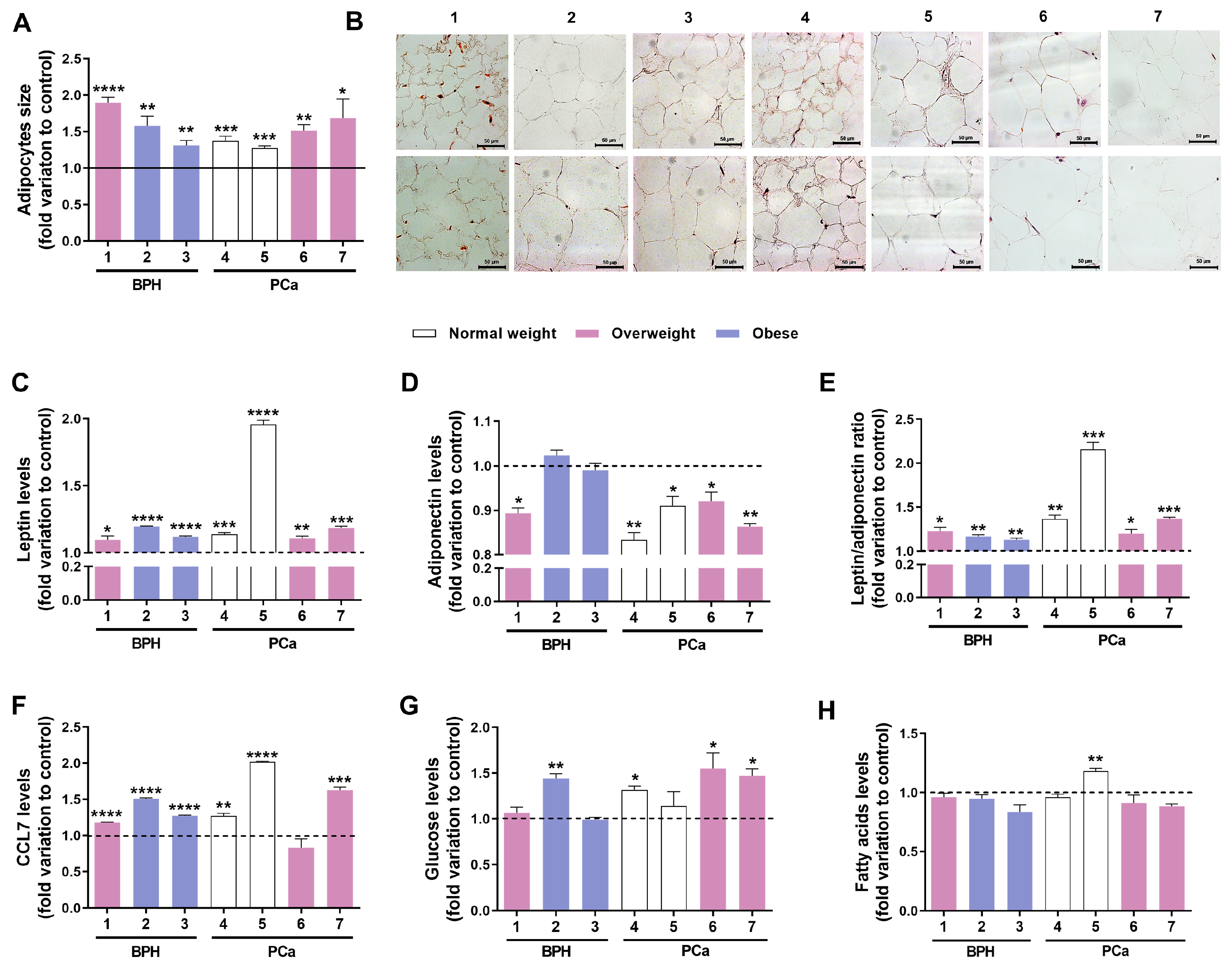

3.4. Exposure to TBT Alters PPAT Morphology and Secretome

3.5. Exposure to TBT Enhanced the Effect of PPAT Secretome in Increasing Prostate Cell Viability

3.6. TBT Effects on the Potential of PPAT Secretome in Reducing PCa Cells’ Sensitivity to Docetaxel and Cabazitaxel

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Estève, D.; Roumiguié, M.; Manceau, C.; Milhas, D.; Muller, C. Periprostatic adipose tissue: A heavy player in prostate cancer progression. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2020, 10, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, B.; Zhou, H.; Wang, S. Periprostatic Adipose Tissue: A New Perspective for Diagnosing and Treating Prostate Cancer. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Pereira, S.S.; Costa, M.; Morais, T.; Pinto, A.; Fernandes, R.; Monteiro, M.P. Adipocyte secreted factors enhance aggressiveness of prostate carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, R.; Monteiro, C.; Cunha, V.; Oliveira, M.; Freitas, M.; Fraga, A.; Príncipe, P.; Lobato, C.; Lobo, F.; Morais, A.; et al. Human periprostatic adipose tissue promotes prostate cancer aggressiveness in vitro. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 31, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzun, E.; Polat, M.E.; Ceviz, K.; Olcucuoglu, E.; Tastemur, S.; Kasap, Y.; Senel, S.; Ozdemir, O. The importance of periprostatic fat tissue thickness measured by preoperative multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in upstage prediction after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2023, 65, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, V.; Guerard, A.; Mazerolles, C.; Le Gonidec, S.; Toulet, A.; Nieto, L.; Zaidi, F.; Majed, B.; Garandeau, D.; Socrier, Y.; et al. Periprostatic adipocytes act as a driving force for prostate cancer progression in obesity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, A.; La Civita, E.; Cennamo, M.; Crocetto, F.; Ferro, M.; Guadagno, E.; Insabato, L.; Imbimbo, C.; Palmieri, A.; Mirone, V. Periprostatic adipose tissue promotes prostate cancer resistance to docetaxel by paracrine IGF-1 upregulation of TUBB2B beta-tubulin isoform. Prostate 2021, 81, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinello, J.; Carballido Rodríguez, J.; Antón Aparicio, L. Role of taxanes in advanced prostate cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2016, 18, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, L. Tumor microenvironment heterogeneity an important mediator of prostate cancer progression and therapeutic resistance. npj Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grün, F.; Blumberg, B. Environmental obesogens: Organotins and endocrine disruption via nuclear receptor signaling. Endocrinology 2006, 147, S50–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janesick, A.S.; Blumberg, B. Obesogens: An emerging threat to public health. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbre, P.D. Endocrine disruptors and obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, L.S. When environmental chemicals act like uncontrolled medicine. TEM 2013, 24, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.; Chappell, V.; Fenton, S.; Flaws, J.; Nadal, A.; Prins, G.; Toppari, J.; Zoeller, R. Executive summary to EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Bourguignon, J.P.; Giudice, L.C.; Hauser, R.; Prins, G.S.; Soto, A.M.; Zoeller, R.T.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: An Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 293–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trasande, L.; Sargis, R.M. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: Mainstream recognition of health effects and implications for the practicing internist. J. Int. Med. 2024, 295, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobstein, T.; Brownell, K.D. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and obesity risk: A review of recommendations for obesity prevention policies. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajer, N.; Du, C.Y.; Checkcinco, C.; Blumberg, B. Obesogens: How they are identified and molecular mechanisms underlying their action. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 780888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijó, M.; Casanova, C.R.; Fonseca, L.R.; Figueira, M.I.; Brás, L.A.; Catarro, G.; Gallardo, E.; Kiss-Toth, E.; Correia, S.; Socorro, S. Tributyltin-dysregulated periprostatic adipose tissue enhances prostate cell survival and migration, implicating the CC motif chemokine receptor 3. J. Environ. Sci. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijó, M.; Carvalho, T.; Fonseca, L.R.; Vaz, C.V.; Pereira, B.J.; Cavaco, J.E.B.; Maia, C.J.; Duarte, A.P.; Kiss-Toth, E.; Correia, S. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals as prostate carcinogens. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2025, 22, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Administração Central do Sistema de Saúde: Valores Laboratoriais de Referência. Available online: https://www.acss.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/tabela.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Normas de Prescrição e Determinação do Antigénio Específico da Próstata. Available online: https://normas.dgs.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/prescricao-e-determinacao-do-antigenio-especifico-da-prostata_psa.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Vaz, C.; Silva, G.; Carvalho, T.; Serra, C.; Brás, L.; Fonseca, L.; Figueira, M.; Cardoso, H.; Duarte, A.; Socorro, S. Human neoplastic and non-neoplastic prostate cells are sensitive to metabolic (de) regulation induced by endocrine disrupting chemicals and dietary factors. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2019, 18, e3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamabe, Y.; Hoshino, A.; Imura, N.; Suzuki, T.; Himeno, S. Enhancement of androgen-dependent transcription and cell proliferation by tributyltin and triphenyltin in human prostate cancer cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2000, 169, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Fernandes, A.; Vanparys, C.; Hectors, T.L.; Vergauwen, L.; Knapen, D.; Jorens, P.G.; Blust, R. Unraveling the mode of action of an obesogen: Mechanistic analysis of the model obesogen tributyltin in the 3T3-L1 cell line. Mol. Cell. Endrocinol. 2013, 370, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussenot, O.; Berthon, P.; Berger, R.; Mowszowicz, I.; Faille, A.; Hojman, F.; Teillac, P.; Le Duc, A.; Calvo, F. Immortalization of human adult normal prostatic epithelial cells by liposomes containing large T-SV40 gene. J. Urol. 1991, 146, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, H.J.; Figueira, M.I.; Carvalho, T.M.; Serra, C.D.; Vaz, C.V.; Madureira, P.A.; Socorro, S. Androgens and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol interplay in modulating prostate cancer cell fate and metabolism. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022, 240, 154181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.R.; Vaz, C.V.; Catalão, B.; Ferreira, S.; Cardoso, H.J.; Duarte, A.P.; Socorro, S. Sweet cherry extract targets the hallmarks of cancer in prostate cells: Diminished viability, increased apoptosis and suppressed glycolytic metabolism. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avancès, C.; Georget, V.; Térouanne, B.; Orio, F., Jr.; Cussenot, O.; Mottet, N.; Costa, P.; Sultan, C. Human prostatic cell line PNT1A, a useful tool for studying androgen receptor transcriptional activity and its differential subnuclear localization in the presence of androgens and antiandrogens. Mol. Cell. Endrocinol. 2001, 184, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamarindo, G.H.; Ribeiro, D.L.; Gobbo, M.G.; Guerra, L.H.; Rahal, P.; Taboga, S.R.; Gadelha, F.R.; Góes, R.M. Melatonin and docosahexaenoic acid decrease proliferation of PNT1A prostate benign cells via modulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics and ROS production. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 5080798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sramkoski, R.M.; Pretlow, T.G.; Giaconia, J.M.; Pretlow, T.P.; Schwartz, S.; Sy, M.-S.; Marengo, S.R.; Rhim, J.S.; Zhang, D.; Jacobberger, J.W. A new human prostate carcinoma cell line, 22Rv1. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 1999, 35, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, K.R.; Mickey, D.D.; Wunderli, H.; Mickey, G.H.; Paulson, D.F. Isolation of a human prostate carcinoma cell line (DU 145). Int. J. Cancer 1978, 21, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaighn, M.; Narayan, K.S.; Ohnuki, Y.; Lechner, J.F.; Jones, L. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3). Investig. Urol. 1979, 17, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariadis, G.; Rosenberg, E. Speciation of organotin compounds in urine by GC–MIP-AED and GC–MS after ethylation and liquid–liquid extraction. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 2009, 877, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yáñez, J.; Riffo, P.; Santander, P.; Mansilla, H.D.; Mondaca, M.A.; Campos, V.; Amarasiriwardena, D. Biodegradation of tributyltin (TBT) by extremophile bacteria from Atacama Desert and speciation of tin by-products. BECT 2015, 95, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamodi, Z.; Al-Habori, M.; Al-Meeri, A.; Saif-Ali, R. Association of adipokines, leptin/adiponectin ratio and C-reactive protein with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2014, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.; Frank, B.; Cuthbertson, D.; Hanna, S.; Eichler, D. Correlates of adiponectin and the leptin/adiponectin ratio in obese and non-obese children. JPEM 2004, 17, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Zheng, J. Adiponectin-induced antitumor activity on prostatic cancers through inhibiting proliferation. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 70, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.J.; Jang, I.H.; Myung, S.C.; Kim, T.H. The effects of adiponectin and leptin in the proliferation of prostate cancer cells. Korean J. Urol. 2009, 50, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberry, K.A.; Somasundar, P.; McFadden, D.W.; Vona-Davis, L.C. Leptin induces cell migration and the expression of growth factors in human prostate cancer cells. Am. J. Surg. 2004, 188, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrab, A.; Pagano, A.; Ayed, K.; Chebil, M.; Derouiche, A.; Kovacic, H.; Gati, A. Leptin promotes prostate cancer proliferation and migration by stimulating STAT3 pathway. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.-J.; Dong, L.-L.; Kang, X.-L.; Li, Z.-M.; Zhang, H.-Y. Leptin promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of prostate cancer cells by regulating ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 8341–8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelito, G.; Watt, M.J.; Taylor, R.A. Personalized medicine for prostate cancer: Is targeting metabolism a reality? Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 778761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, E.; Arranz, J.Á.; Maroto, J.P.; León, L.Á.; Bellmunt, J. Expert opinion on chemotherapy use in castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013, 88, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, A.; Pfister, D. Cabazitaxel in the Management of Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Progressing After Docetaxel-based Chemotherapy. Eur. Oncol. Haematol. 2012, 13, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino-Marentes, M.E.; Hernández-Flores, G.; Ortiz-Lazareno, P.C.; Villaseñor-García, M.M.; Orozco-Alonso, E.; Sierra-Díaz, E.; Solís-Martínez, R.A.; Cruz-Gálvez, C.C.; Bravo-Cuellar, A. Sensitizing the cytotoxic action of Docetaxel induced by Pentoxifylline in a PC3 prostate cancer cell line. BMC Urol. 2021, 21, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, J.; Sabzichi, M.; Molavi, O.; Shanehbandi, D.; Samadi, N. Combined treatment with stattic and docetaxel alters the Bax/Bcl-2 gene expression ratio in human prostate cancer cells. APJCP 2016, 17, 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevik, O.; Acidereli, H.; Turut, F.A.; Yildirim, S.; Acilan, C. Cabazitaxel exhibits more favorable molecular changes compared to other taxanes in androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2020, 34, e22542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Guo, F.; Zhou, L.; Stahl, R.; Grams, J. The cell size and distribution of adipocytes from subcutaneous and visceral fat is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in humans. Adipocyte 2015, 4, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.M.; Lee, E.-S.; Son, D.-S. Chemokine network during adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells: Differential response between growth and proinflammatory factor in preadipocytes vs. adipocytes. Adipocyte 2014, 3, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessie, G.; Ayelign, B.; Akalu, Y.; Shibabaw, T.; Molla, M.D. Effect of leptin on chronic inflammatory disorders: Insights to therapeutic target to prevent further cardiovascular complication. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 3307–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilariño-García, T.; Polonio-González, M.L.; Pérez-Pérez, A.; Ribalta, J.; Arrieta, F.; Aguilar, M.; Obaya, J.C.; Gimeno-Orna, J.A.; Iglesias, P.; Navarro, J. Role of leptin in obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.J.; Monteiro, C.P.; Cunha, V.F.; Azevedo, A.S.; Oliveira, M.J.; Monteiro, R.; Fraga, A.M.; Príncipe, P.; Lobato, C.; Lobo, F. Tumor cell-educated periprostatic adipose tissue acquires an aggressive cancer-promoting secretory profile. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 29, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Pan, Y.; Hu, D.; Peng, J.; Hao, Y.; Pan, M.; Yuan, L.; Yu, Y.; Qian, Z. Recent progress in nanoformulations of cabazitaxel. Biomed. Mat. 2021, 16, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertuloso, B.D.; Podratz, P.L.; Merlo, E.; de Araújo, J.F.; Lima, L.C.; de Miguel, E.C.; de Souza, L.N.; Gava, A.L.; de Oliveira, M.; Miranda-Alves, L. Tributyltin chloride leads to adiposity and impairs metabolic functions in the rat liver and pancreas. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 235, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, T.; Kikugawa, T.; Tanji, N.; Miura, N.; Asai, S.; Higashiyama, S.; Yokoyama, M. Long-term exposure to leptin enhances the growth of prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philp, L.K.; Rockstroh, A.; Sadowski, M.C.; Fard, A.T.; Lehman, M.; Tevz, G.; Libério, M.S.; Bidgood, C.L.; Gunter, J.H.; McPherson, S. Leptin antagonism inhibits prostate cancer xenograft growth and progression. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2021, 28, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, H.J.; Carvalho, T.M.; Fonseca, L.R.; Figueira, M.I.; Vaz, C.V.; Socorro, S. Revisiting prostate cancer metabolism: From metabolites to disease and therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 1499–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Cho, Y.B. CCL7 Signaling in the Tumor Microenvironment in Tumor Microenvironment; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1231, pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bub, J.D.; Miyazaki, T.; Iwamoto, Y. Adiponectin as a growth inhibitor in prostate cancer cells. BBRC 2006, 340, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakikhani, M.; Dowling, R.J.; Sonenberg, N.; Pollak, M.N. The effects of adiponectin and metformin on prostate and colon neoplasia involve activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Cancer Prev. Res. 2008, 1, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient No. | Histopathological Diagnosis | Disease Stage | Age | BMI (kg/m2) | Classification | Diabetes Type | Anti- Cholesterol or -Diabetic Medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BPH | N.A. | 69 | 28.7 | Overweight | N.A. | Rosuvastatin |

| 2 | BPH | N.A. | 79 | 31.0 | Obese | N.A. | Simvastatin |

| 3 | BPH | N.A. | 65 | 30.7 | Obese | N.A. | N.A. |

| 4 | Carcinoma (GS 6, 3 + 3, ISUP 1) | I | 74 | 24.5 | Normal weight | N.A. | Atorvastatin |

| 5 | Carcinoma (GS 7, 3 + 4, ISUP 2) | I | 60 | 24.2 | Normal weight | N.A. | Atorvastatin Ezetimibe |

| 6 | Carcinoma (GS 6, 3 + 3, ISUP 1) | I | 82 | 25.3 | Overweight | 2 | Metformin Dapagliflozin |

| 7 | Carcinoma (GS 7, 4 + 3, ISUP 3) | I | 68 | 28.4 | Overweight | 2 | Metformin |

| Patient No. | Total Cholesterol (mg/dL, RV < 200) | LDL (mg/dL, RV < 160) | Triglycerides (mg/dL, RV < 160) | Glucose (mg/dL, RV 70–110) | Total PSA (ng/mL, RV < 4) | Free/ Total PSA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 144 | 78 | 97 | 105 | 3.30 | 14.8 |

| 2 | 177 | 83 | 141 | 98 | 4.45 (*) | N.P. |

| 3 | 201 (*) | 112 | 190 (*) | 97 | 4.63 (*) | N.P. |

| 4 | 134 | 82 | 140 | 90 | 11.06 (*) | 29.8 |

| 5 | 135 | 57 | 132 | 94 | 8.37 (*) | 19 |

| 6 | 154 | 107 | 84 | 102 | 6.34 (*) | 18 |

| 7 | 157 | 101 | 105 | 137 (*) | 3.59 | N.P. |

| Patient No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Cell viability (% relative to DMEM control) | |||||||

| PNT1A | NS | NS | NS | 13 | 10 | 17 | 13 |

| 22Rv1 | 16 | 10 | 14 | NS | 16 | NS | 14 |

| DU145 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 | NS | NS |

| PC3 | NS | 6 | 11 | NS | NS | 15 | 13 |

| Patient No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Cell viability (% relative to PPAT-CM) | |||||||

| PNT1A | 10 | NS | 17 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 22Rv1 | 15 | 19 | NS | NS | NS | 17 | NS |

| DU145 | 15 | 23 | NS | NS | 9 | 16 | NS |

| PC3 | NS | NS | 15 | 8 | 11 | NS | NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feijó, M.; Fonseca, L.R.S.; Catarro, G.; Vaz, C.V.; Rabaça, C.; Pereira, B.J.; Gallardo, E.; Kiss-Toth, E.; Correia, S.; Socorro, S. Obesogenic Dysregulation of Human Periprostatic Adipose Tissue Promotes the Viability of Prostate Cells and Reduces Their Sensitivity to Docetaxel and Cabazitaxel. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040322

Feijó M, Fonseca LRS, Catarro G, Vaz CV, Rabaça C, Pereira BJ, Gallardo E, Kiss-Toth E, Correia S, Socorro S. Obesogenic Dysregulation of Human Periprostatic Adipose Tissue Promotes the Viability of Prostate Cells and Reduces Their Sensitivity to Docetaxel and Cabazitaxel. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(4):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040322

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeijó, Mariana, Lara R. S. Fonseca, Gonçalo Catarro, Cátia V. Vaz, Carlos Rabaça, Bruno J. Pereira, Eugenia Gallardo, Endre Kiss-Toth, Sara Correia, and Sílvia Socorro. 2025. "Obesogenic Dysregulation of Human Periprostatic Adipose Tissue Promotes the Viability of Prostate Cells and Reduces Their Sensitivity to Docetaxel and Cabazitaxel" Medical Sciences 13, no. 4: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040322

APA StyleFeijó, M., Fonseca, L. R. S., Catarro, G., Vaz, C. V., Rabaça, C., Pereira, B. J., Gallardo, E., Kiss-Toth, E., Correia, S., & Socorro, S. (2025). Obesogenic Dysregulation of Human Periprostatic Adipose Tissue Promotes the Viability of Prostate Cells and Reduces Their Sensitivity to Docetaxel and Cabazitaxel. Medical Sciences, 13(4), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040322