Abstract

In 2009, the tropical cyclonic storm Aila hit 11 southwestern coastal districts in Bangladesh, which triggered migration. Many studies were conducted on the impact of Aila on southwestern coastal communities; however, no comparative study was done on migrant and non-migrant households. Therefore, this article set out to assess the impact of cyclone Aila on the socio-economic conditions of migrant and non-migrant households. The households that could not cope with the impact, resulting in at least one household member having to migrate to seek an alternative source of income, were considered migrant households. On the other hand, non-migrant households were considered as those where no one migrated. The unit of analysis was the households. The research was conducted in the Koyra and Shymnagar sub-districts of Khulna and Satkhira, respectively. Mixed-method analysis was carried out using quantitative data collected from 270 households through a survey and qualitative data through 2 focus group discussions, 12 key informant interviews, and informal discussions. Data were analyzed through a comparative analysis of the migrant and non-migrant households. The findings showed that migrant households were better equipped to recover from losses in terms of income, housing, food consumption, and loan repayments than non-migrant households. It can be argued that the options of migration or shifting livelihood are better strategies for households when dealing with climatic events. Furthermore, the outcome of this research could contribute to the growing body of knowledge in an area where there are evident gaps. The findings could support policymakers and researchers to understand the impacts of similar climatic events, as well as the necessary policy interventions to deal with similar kinds of climatic events in the future. The study could be useful for developing and refining policies to recover from losses as a result of the same types of climatic events.

1. Introduction

Climate change is responsible for catastrophic disasters such as droughts, storms, and floods that lead to human migration [1]. Over the last 30 years, the frequency of disasters such as cyclones, storm surges, floods, and droughts increased threefold, which led to human migration at an alarming rate [2]. It is predicted that, by 2050, between 250 million (which is one of every 45 people in the world) [3] and one billion [4] people will be forced to move permanently because of climatic disasters. Bangladesh is generally recognized as one of the most climate-vulnerable countries because of its vast low-lying areas [5,6,7]. The country is frequently affected by climatic events such as cyclones, floods, droughts, and storm surges, which represent approximately two-fifths of those faced globally [8,9]. In fact, a severe cyclone hits Bangladesh every three years on average [10,11,12]. Moreover, the coastal areas and the Bay of Bengal are located at the northern tip of the Indian Ocean, and are frequently hit by cyclonic storms, generating high tidal surges, floods, and storm surges, which lead to permanent or temporary human displacement [6,13,14,15,16,17]. It is forecasted that, by 2050, about 17% of coastal areas will be inundated [16].

Furthermore, global warming and sea-surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) are interlinked [18]. Coastal people face enormous coastal erosion due to climate change, which may accelerate the destructive wind–wave interaction faced by coastal seashores, subjecting them to a higher sea surface temperature [19]. It was observed that the sea-surface temperature (SST) increased over the last four decades in the northern Indian Ocean, as well as in the Bay of Bengal, which is one of the major factors leading to the formation of depressions and low-pressure systems in the area [8,16,18,20]. Furthermore, SST changes are responsible for various kinds of disasters; thus, climate change will increase the frequency of disasters in the future, especially in the Indian Ocean. Cyclone Aila in 2009 was one of the catastrophic events formed in the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, an increase in the number of disasters will destroy infrastructure, crop production, livelihoods, and the economy of the country [12].

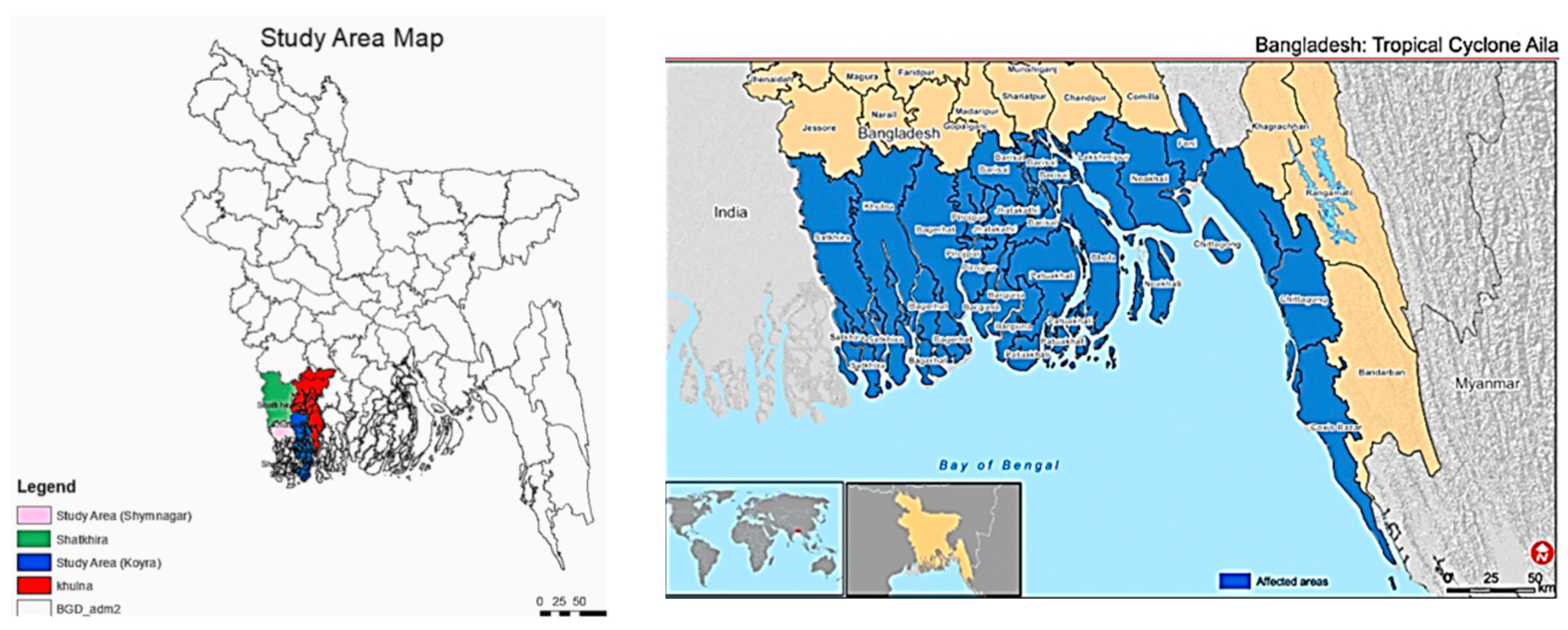

Cyclone Aila, a category-1 cyclonic storm, was the second tropical cyclone hit in 11 southwestern coastal districts in Bangladesh on 21 May 2009. Around 3,928,238 people and 948,621 households were affected by Cyclone Aila [21]. It formed in the northern Indian Ocean, about 350 km offshore and became a severe cyclonic storm within four days. Cyclone Aila struck the coastal districts during the spring tide. The cyclone’s effects lasted 15 h (approximately) with wind speeds up to 120 km/h (75 mph) and tidal surges up to 6.5 m [20]. Although the intensity of the cyclone was relatively low, it inundated 350,000 acres of cropland [21]. About 1742 km of coastal polders (embankments) were washed away by the tidal surge from the cyclone, and saline water inundated large parts of the southern districts of Khulna and Satkhira (46% of croplands) for up to two years [21,22]. The full moon worsened the effects of the cyclone. It was also reported that Cyclone Aila damaged around 38,885 hectares of shrimp fields (ghers), as well as sweet fishponds [20,23]. Fully damaged also were 445 educational institutions, 2233 km of road, and 157 km of bridges/culverts [24]. The cyclone struck at a time when people were trying to recover from the losses following Super Cyclone Sidr (Category 4), which battered the districts in 2007 (merely 18 months before). These two events illustrate both rapid and slow-onset climate events; however, the consequences of Cyclone Aila differed from those of Super Cyclone Sidr. While Aila was a Category 1 cyclone, the losses and damages it caused were widespread; in fact, the recovery after Sidr was much more rapid than that after Aila. The death toll from Cyclone Aila was 190 people, which was comparatively much lower than other major disasters that occurred in Bangladesh. However, the recovery from Cyclone Aila remained a challenge because the coastal people could not fully recover from the effects of Cyclone Sidr (2007) [21]. Almost two years after Aila (in 2011), many parts of Aila-affected areas remained underwater, where the land was unproductive and trees died due to saline intrusion in the soil, and people faced severe water and food shortage, as well as unemployment. Figure 1 provides a map of Cyclone Aila-affected areas.

Figure 1.

Cyclone Aila-affected areas.

The coastal people were mostly dependent on natural resources for their livelihood. The two major occupations of the coastal people, farming and fishing, were severely affected by Cyclone Aila [21]. Post Aila, prolonged waterlogging resulted in the increase in salinity in both water and soil [12,22,25]. Due to prolonged waterlogging, about 90% of the livelihood options of southwestern coastal communities were damaged [26]. It is a fact that the consequences of a disaster are not the same in the affected households even those from the same community. In general, vulnerable poor people have limited abilities in terms of socioeconomic condition, social network, and access to information, education and technology to adapt themselves to a severe situation, forcing them to migrate abruptly. In contrast, people in a comparatively better position in terms of human and social capital, migrated in a planned way, while relatively poor women and dependent members were trapped and stayed in affected areas [12,27].

Nevertheless, the consequence of cyclone Aila was much different from other cyclones as Aila was a Category 1 type, cyclonic storm formed in the Indian Ocean, with a slow onset but long-term consequences. For instance, it induced the migration of around two million people [20]. Another main difference between cyclones Aila with other cycloneis that it led to three other extreme events or climatic events, flood, storm surge, salinity, and waterlogging, viewed as new forms of calamities in the southern coastal districts [28]. Although Cyclone Aila was a slow onset event that did not cause a significant loss of life or property, its impact was prolonged. It reduced land productivity, so households required external assistance to cope with loss of incomes. As Cyclone Aila continued to directly threaten the source of income of the coastal communities several years after it struck, many people migrated to reduce their hardship; in particular, male members of the affected households moved out to look for income opportunities [29,30].

The shock resulting from climatic events also affected the socio-economic conditions of coastal communities that were dependent on natural resources in various ways such as a loss of assets and livelihood options, reduced income, food shortage, and water scarcity [16]. Disaster preparedness response strategies such as an early warning system and the construction of a cyclone shelter reduced the death tolls in years, but the impacts on the socio-economic conditions of the affected people remained substantial. Cyclone Aila also adversely affected the socio-economic conditions of the coastal communities in terms of assets, incomes, livelihood options, and food consumption. However, though many research studies have been carried out with regard to the impact of Cyclone Aila on the socio-economic conditions of affected communities and the factors of climate-induced migration [2,12,16,20,25,31,32], comparative analyses on the socio-economic conditions of migrant and non-migrant households were neither carried out nor was there an analysis performed on the households’ strategy in dealing with similar climatic events such as migration or shifting livelihood options. Therefore, understanding the coastal people’s behavior toward coping with Cyclone Aila is necessary in order to deal appropriately with other climatic events in the future. This research, therefore, is aimed to assess to assess the impact of a climatic event i.e., Cyclone Aila, on the socio-economic conditions of migrant and non-migrant households in the southwestern coastal areas of Bangladesh. Thus, lessons from the Cyclone Aila can be applied to deal with similar future disasters.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Areas

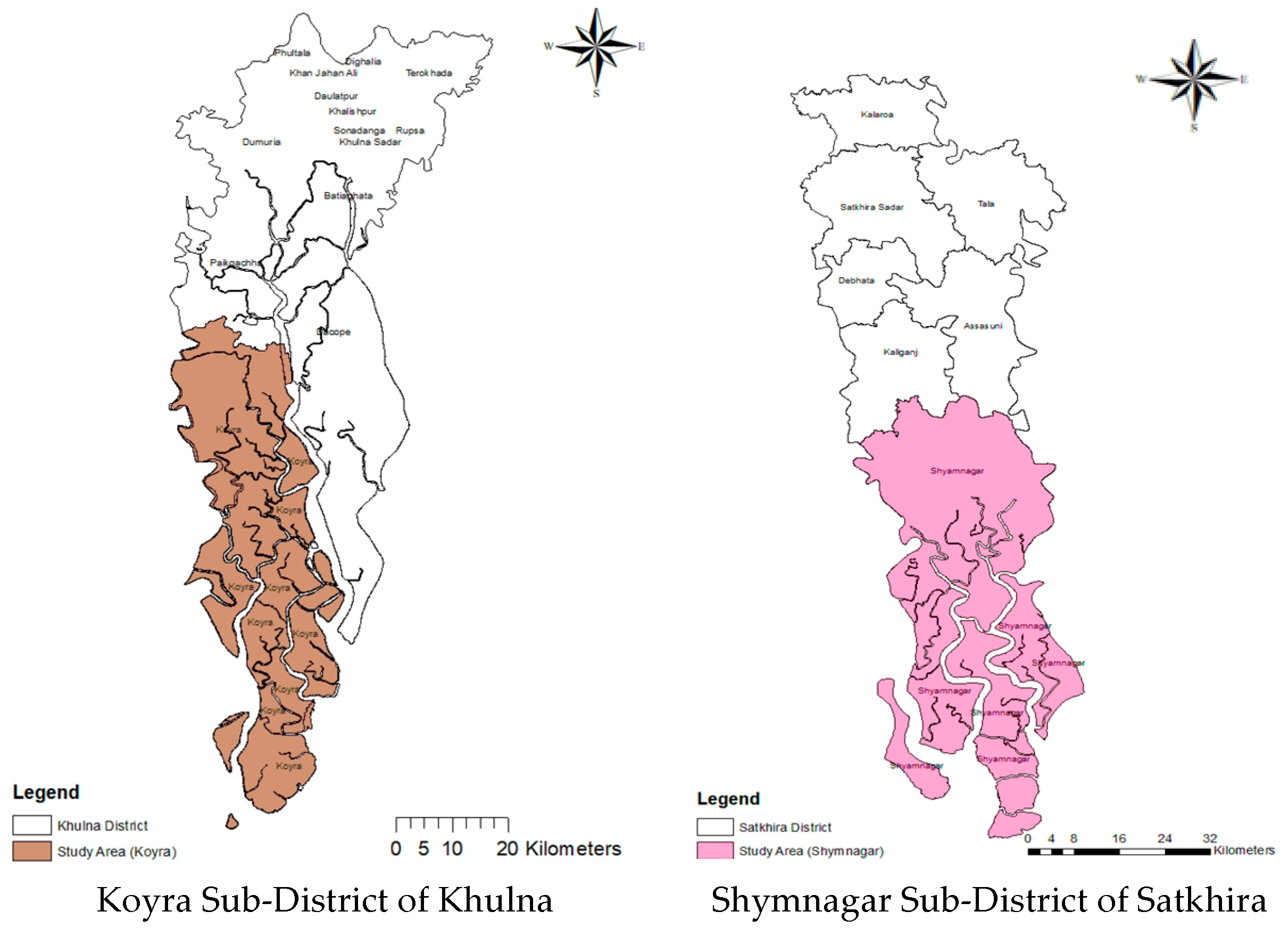

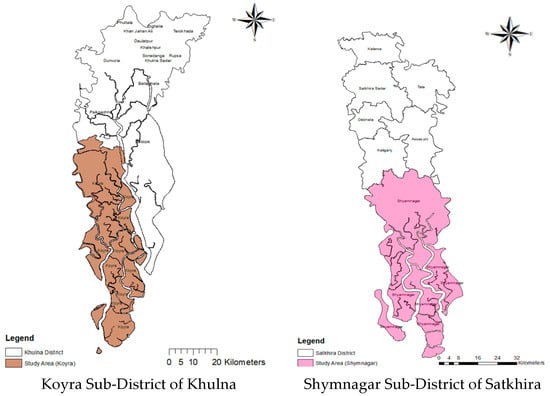

This study was conducted in Koyra and Shymnagar sub-districts in Khulna and Satkhira districts respectively. Koyra is the largest sub-district (upozila) of Khulna district, which is located at 22.3417° N 89.3000° E. Established in 1983, Koyra (upozila) occupies an area of about 1775 sq. km, including 951.66 sq. km of forest area. Economically, people mostly depend on agriculture, at 65 %; 44.30% on cropping, livestock, forestry, and fishery, and 22% on wage labor [33]. The largest mangrove forest nearby, Sundarban, provides different ecosystems to these coastal people. Koyra was affected by various hazards such as waterlogging, saline intrusion, storm surge, sea-level rise, and flood [34].

Shymnagar is a sub-district (upozila) of the Satkhira District in the southwestern part of the Division of Khulna in Bangladesh, located at 22.3306° N 89.1028° E. It was established in 1897 as a police station (thana), and in 1982 as a sub-district or upozila. Shymnagar has a total land area of about 1968.24 sq. km, which includes 1534.88 sq. km of forest reserves, and about 3.92 sq. km of land is considered riverine areas. In this sub-district, a total of 34,541 farms and around 65% of households depend on agriculture; 38% on cropping, livestock, forestry, and fishery, and 27% as wage laborers in agricultural fields [33]. Shymnagar is another hazard-prone upozila in terms of waterlogging, saline intrusion, storm surge, sea-level rise, and floods [34].

2.2. Criteria for the Selection of the Study Areas

The study areas were selected using two criteria: the area with the highest loss and damage from a disaster and the area with the highest migration compared with other disaster-affected areas. According to the District Damage Assessment Report published by the Government of Bangladesh (2009), around 154,206 households were affected in Khulna and Satkhira whereby, the highest number of affected households were from Koyra and from Shymnagar, with approximately 38,514 and 48,457 respectively [11,16,21]. In addition, around 123,000 people migrated from the two districts in the aftermath of the disaster, where approximately 42,000 people (34%) were from Koyra while about 36,000 (29%) were from Shymnagar. Based on this data, this research was conducted in Koyra Sub-District of Khulna and Shymnagar Sub-District of Satkhira. Table 1 shows Cyclone Aila-affected areas and the number of affected households.

Table 1.

Cyclone Aila-affected areas and the number of affected households.

The maps of study areas Koyra Sub-District of Khulna and Shymnagar Sub-District of Satkhira Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Map of the study areas.

2.3. Sampling and Sample size

The primary unit of analysis was migrant and non-migrant households as they are considered as a social unit [35]. In addition, this paper considered migrant households who were also affected by Aila, but could not cope with their situation. Therefore, affected households with one member who migrated temporarily or permanently to other places to look for alternative income-generating sources and those where no one migrated were considered. A total of 86,971 households (38,514 in Koyra and 48,457 in Shymnagar) were affected by Aila [11,21]. The sample size was determined following the formula of Kothari (2004) [36].

N = 38,514 + 48,457 = 86,971; e = marginal error 0.05; z value = 1.64; n = 268 households.

Sample size: around 270 households.

A survey was conducted on 270 households, roughly 32% of the total households that were affected by cyclone Aila; of which, 18 (51%) of the surveyed households were migrant households while 132 (49%) were non-migrants.

2.4. Data Collection Method

Data were collected from both primary and secondary sources. The primary data were collected through household survey using a standardized, semi-structured questionnaire. However, a reconnaissance survey was also conducted in two upozilas, Koyra and Shymnagar, for the purpose of understanding the present physical conditions of the study areas, the settlement patterns, and the strategies and assets of the people. The information gathered through this technique was useful in revising the draft questionnaire. To formulate the final questionnaire, a pilot survey was carried out based on the revised draft questionnaire. After finalizing the questionnaire (attached in the supplementary materials), the household survey was conducted with 270 households (around 32% of total Aila affected areas); of which, 138 were migrant households and 132 were non-migrant households. The households were selected based on their similar socio-economic conditions prior to Cyclone Aila. Two focus group discussions (FGDs) were also performed in Koyra and Shymnagar, which enabled the researcher to understand the main issues in the sub-districts. Twelve key informant interviews (KIIs) were completed at different levels: national, district, sub-district, and the village level. Twenty participants from both migrant and non-migrant households participated in each FGD. An interview checklist was prepared for the discussion, which lasted between 60 to 90 minutes. The interview was conducted in the local language (Bangla).

2.5. Data Analysis and Technique

From the methodological aspect, the research used a mixed method. Various research studies [2,20,31,37,38,39,40] have used mixed method for similar kinds of study. The fundamental reason for using mixed method was to combine the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methods and to better understand the complex situation and investigate the different issues. Quantitative data were obtained through household survey while qualitative data were generated from the focus group discussions (FGDs), key informant interviews (KIIs), and informal discussions. A comparative analysis of migrant and non-migrant households was conducted based on the data collected using the different methods in this research. The qualitative information obtained through informal discussions, focus group discussions, and key informant interviews enabled the researcher to substantiate the quantitative findings. Through the qualitative data, some individual and household level information was examined in relation to the impacts of Cyclone Aila and people’s perception of the ways to deal with future disasters. Statistical techniques such as frequency, percentages, mean, cross-tabulation, chi-square, and t-tests were applied to analyze the data. Secondary data were also collected from several published relevant research papers, journal articles, maps, books, assessment reports, Non-Governmental Organizations, and Government reports to supplement the primary data obtained.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Profile of the Within-Household Respondents

Results from the research revealed that, among the 270 households, around 51% were migrant households, while 49% were non-migrant households (see Table 2 below). The average age of the within-household respondents was 33 years old. Among the respondents, around 33% were children (0–14 years), 59% were in the young/mid-age group (15–50 years), and the elderly/retired (51 years or above) comprised 9% of the total. Furthermore, Muslim within-household respondents consisted 91% of the total number of respondents, while 9% were Hindus. The household size was between two to 14 members. Around 49% of the surveyed households had 2–4 household members, while 40% had 5–7. Around 10% comprised 8–10 members. The households also differed in their educational attainment and literacy. The illiteracy rate among migrant households was lower compared to non-migrant households, at 32% and 39% respectively. In both households, around 40% of the respondents achieved a primary level of education (up to 5th grade). About 28% of the respondents from migrant households received their secondary level of education (up to 12th grade), which was higher than that of the non-migrant households, at 21%. Table 2 shows the demographic profile of the within- household respondents.

Table 2.

Demographic profile of the respondent households.

3.2. Impacts of Cyclone Aila on Migrant and Non-Migrant Households

The destruction caused by Cyclone Aila that occurred in 2009 was in the form of cyclone, storm surge, flood, waterlogging, and saline intrusion. These have affected the socio-economic conditions of the people such as those related to housing and other assets, income-generating activities, food consumption pattern, water supply, and sanitation in the coastal communities. As a result, people’s lives and livelihood options have also been threatened. Table 3 presents the financial loss of migrant and non-migrant households due to Cyclone Aila.

Table 3.

Financial loss of assets incurred by Aila among migrant and non-migrant households.

The table also shows that both migrant and non-migrant households suffered tremendous financial losses as a result of the cyclone. About 24% of migrant households faced economic loss in agriculture of about US$651, while 11% of the non-migrant households lost about US$272. Moreover, 8% of the migrant households’ experienced monetary losses in shrimp farming of around US$403 whereas 22% of the non-migrant households lost about US$720. The results imply that migrant households depended mainly on farming, while non-migrant households relied considerably on fishing or aquaculture (i.e., shrimp farming). Results from the FGDs also showed that agricultural land loss was caused by salinity intrusion resulting from the cyclone; thus, income and earning opportunities were also severely affected. The fishing sectors also faced tremendous losses. Compared with non-migrant households, it was observed that damage cost per migrant household was higher than that of non-migrant households. Migrant households’ average damage cost was also around US$345 per household, for non-migrant households, it was around US$288 per household.

3.3. Relief after Cyclone Aila

Shocks from disasters are often so severe that people generally need external assistance to cope with the impacts. Immediately after the devastation from Cyclone Aila, GoB, NGOs, and national and international humanitarian agencies offered assistance for the affected communities. They provided immediate relief like food, clothes, medicines, and other necessary materials for up to 2 years after Aila. The government also provided the communities with additional humanitarian support including food, emergency shelter, medicine, drinking water, and cash [21,39]. Around 47,810 families in the four upozilas (sub-districts) of Khulna and Satkhira received 20 kg of rice every month until November 2010 as part of the Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) and Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) programs, which lasted for two years.

In the study areas, Koyra and Shymnagar, both migrant and non-migrant households were also provided with relief in the form of food assistance, clothes, water and sanitation, emergency medicine, shelter, tent, and cash grants. The government also distributed 20 kg of rice per month for up to 14 months, from September 2009 to November 2010, under the VGF program to the affected communities [36]. Table 4 presents a list of relief items received by migrant and non-migrant households.

Table 4.

Relief received by migrant and non-migrant households.

Table 4 illustrates that both migrant and non-migrant households received relief in the form of food assistance, WASH, shelter, and agricultural support from various agencies; however, there was no significant difference in their receipt of grants. The distribution of relief items primarily depended on the severity of the damages to the households. However, results from the FGDs revealed that each affected household also received approximately US$215 to meet the immediate needs. However, the amount was inadequate to recover from the losses and damages as a result of the disaster. Thus, some household members were forced to migrate. Results further revealed that after providing emergency assistance, government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and donor agencies initiated some rehabilitation programs to improve the livelihoods of the affected communities such as the reconstruction of embankments and roads, tree planting. A daily allowance of US$2 for up to 7 to 10 days a month was also provided; however, it was also insufficient for the long-term needs of the households. The households expected to obtain long-term relief or recovery assistance such as wage employment rather than short-term recovery efforts. This might have influenced some household members to migrate. Nevertheless, it also important to assume that the relief assistance provided in the short term have addressed their immediate needs though in the long term, it might have created dependency.

3.4. Response Strategy

3.4.1. Immediate Response

In the aftermath of the cyclone Aila, displaced people made use of the rooftops, embankment, highways, relief camps, schools, mosques, and houses of relatives as temporary shelters. Participants in the FGDs stated that there was only one cyclone center in each upozila for the affected communities, which was about 2 kilometers away from the villages. The hazardous road conditions and the poor transportation system compelled some affected villagers to utilize the facilities in these shelters when Cyclone Aila struck [41]. Table 5 presents the immediate shelters available to those affected by the cyclone.

Table 5.

Immediate shelters of the Aila affected households.

Survey results revealed that around 26% of the non-migrant households and 33% of the migrant households lived on the embankments after being displaced from their homes. These percentages were higher compared to those who were on the roadsides, at 15% for non-migrant households, and 22% for migrant households (see Table 5). From the FGDs, it can also be established that the affected households moved to the embankments and highways, wherein some households stayed there for 3–4 days while others lived up to two years. During the disaster, temporary housing turned into permanent housing for many households despite the fact that it was not considered suitable for long-term habitation [42]. The government also failed to repair the collapsed embankments due to the high tides in the river. The FGDs also showed that, on average, the victims waited for six months before they were able to return to their homes while in some cases, the waiting time was one year due to waterlogging. In the aftermath of the cyclone Aila, the affected households received relief or assistance in various forms from the government, different NGOs, national and international donor agencies, and from the general population.

3.4.2. Short to Mid-Term Response Strategies

The affected migrant and non-migrant households in Koyra and Shymnagar adopted various response strategies to deal with the challenges resulting from the losses caused by the cyclone Aila. Some strategies included obtaining credit, selling durable assets, changing cropping patterns, livestock rearing, reducing expenditure, changed food consumption patterns, and migration. These were effective in the short-term, but for the long term, it may not work [43]. Table 6 shows the response strategies taken by Aila-affected households.

Table 6.

Response strategies taken by Aila affected people.

Borrowing cash was the most common strategy adopted by the victims [10]. As shown in Table 6, around 41% of the migrant households and 45% of the non-migrant households obtained credit from formal and informal financial sources such as mahajans (moneylenders), neighbors, and relatives who were financially affluent. Households with very few opportunities to recover from the disaster mostly relied on informal sources to obtain cash. Moreover, some households sold their properties and belongings such as land, jewelry, etc. 31% of migrant households and 25% of non-migrant households). This shows that selling durable assets in a post-disaster situation was a common strategy for affected households [10].

Agricultural farm-based households often adopted various disaster-response strategies to reduce the impact of climate change on them such as diversifying their income sources, changing cropping practices, and crop diversification [40]. Aila-affected coastal communities were also encouraged to diversify crops by applying saline water-tolerant crops, and vegetables such as pumpkin, ladyfinger, eggplant, and spinach, which require a minor irrigation system [44]. This strategy was very effective for long-term planning but not in the short-term. In fact, only 10% of the migrant households and 7% of the non-migrant households tried to change the cropping pattern after the cyclone Aila. On the other hand, households relied on savings or self-insurance; 3% of the migrant households and 9% of the non-migrant households. Results also showed that close to 14% of both migrant and non-migrant households reduced their expenditures on health and education. The possible reasons could be that the affected households sent their children to work; thus, disasters decreased children’s schooling. This strategy may result in other problems related to skills (education) and labor. Previous studies [45,46] also found that in both in rural and urban households, children’s school attainment decreased after a disaster.

Nevertheless, these short-term strategies were generally not adequate in minimizing the impacts on people. Short-term strategies and insufficient external assistance failed to reduce the hardships of those affected, which led to out-migration [19,47]. Migration is a response to climate variability and extreme weather events, and could be a successful adaptation strategy [48]. Furthermore, migration enhances household resilience and reduces the suffering of households who are mainly dependent on natural resources while other strategies (coping or adaptation) failed [49]. Although migration could reduce the losses from previous disasters, it may not improve the resilience of households to deal with future climate shocks [50].

3.5. Impacts on the Socio-Economic Conditions of Migrant and Non-Migrant Households

3.5.1. Economic Impacts

This section analyzed the economic impacts of the affected households in the aftermath of the cyclone Aila (2009). A comparison was made between migrant and non-migrant households with regard to their economic conditions in terms of impacts on occupation, income, and loan status.

Occupation

As Bangladesh is an agriculture-based country, it is evident that around 36% of households were engaged in agriculture including forestry, animal husbandry, and fisheries [51]. People living in coastal areas are mostly small and marginal farmers who mostly relied on rain-fed agriculture, cultivating a single crop of Aman paddy. Moreover, fisheries or aquaculture was dominated by shrimp farming with a small part of other fishes, and forest resource-dependent communities [10,16,52]. Climatic events affect the productivity of agricultural land [53]; thus, smallholders, marginal farmers are affected more [44]. Data from the field survey shows the occupation of migrant and non-migrant households before and after Aila (Table 7).

Table 7.

Occupation before and after Aila.

Data (Table 7) shows that around 66% of migrant and 17% of non-migrant household members were engaged in agriculture before Aila, but the number drastically fell to 12% and 9% respectively for both the groups after the disaster. Results also show that in the aftermath of the cyclone, off-farm wage labor involvement increased between migrant and non-migrant households to 57% and 31%. In contrast, the proportion of non-migrant households involved in fishing reduced to approximately 20% while in migrant households, it rose to 6%.

Salinity in water and soil were one of the adverse impacts of climate change hazards such as cyclone, flood, storm surge, drought, and changing temperature pattern, which affected the productivity of agricultural land in coastal areas [7,44,53]. During Cyclone Aila, a severe storm, and 10 to 13 meters of tidal surge pressure had broken the embankment resulting in the intrusion of saline water into agricultural land and shrimp farms and prolonged waterlogging. This resulted in increased salinity in both water and soil [39]. Agricultural land also became unproductive [22], which adversely affected crop production. Thus, farmers faced enormous crop failure in crop products like rice, jute, and sugarcane [23]. Moreover, farmers tried to produce boro rice, but long-term waterlogging has led to land degradation [6,22,39,54]. Furthermore, to produce boro rice, pulse, or other crops, farmers had to borrow, which created additional financial burden on smallholders, marginal farmers, labors, and sharecroppers, triggering migration. Some of them also changed their occupation, from farm to non-farm or fishing jobs to survive. Changes in occupation were a common phenomenon in any short- or long-term calamity. People usually change their source of income when primary sources could not meet their basic needs such as farm on to off-farm sectors [54,55]. Results from the FGDs show that affected households changed from farm to off-farm wage employment after the cyclone as a day laborer, rickshaw puller, or shopkeeper. Besides these, some people were also involved in different kinds of occupations such as business and service.

Another major occupation of the coastal people is fishing particularly shrimp fry collection in ghers (shrimp ponds). During the cyclone Aila, the polders that protected shrimp farms collapsed because of the high tide; therefore, waterlogging and salinity affected the shrimp farms. At the time of the cyclone, the shrimp farmers were also getting ready for harvesting; thus, the monetary losses in shrimp farming were massive. Their limited capability to recover from the losses in income increased to about ten times more as a result [10]. Moreover, lingering reconstruction of the embankment also increased soil salinity for two years after Aila; thus, the recovery of shrimp farms was impossible for few farmers [56], which induced migration. Affected people were also forest dependent. They used to collect fuelwood, honey, fish, and crab from mangrove forest (Sundarban). However, because of another cyclone, Sidr in 2007, GoB restricted entry to the area from March to May [21], which also initiated out-migration. Apart from this, other occupations were also hindered because of the devastation caused by Aila; long-term inundation and high tide in rivers obstructed homestead gardening as well as resource collection from the mangrove forest. The livelihood options of the coastal communities became very limited; thus, they had to look for alternative income sources, which influenced people to change their sources of income from farm to non-farm forcing some people to move. In addition, the employment opportunities and income of coastal people in the southwest reduced after Cyclone Aila. At Shymnagar upozila, the unemployment rate increased from 11% to 60% between 2009–2010 while per capita income decreased [57]. Table 8 shows the average monthly income of migrant and non-migrant households before and after the cyclone.

Table 8.

Average monthly income of migrant and non-migrant households (before and after Aila).

The above table presents the monthly income (average per household in US dollars) for both migrant and non-migrant households. As seen from the table, average monthly income reduced as a result of the damage caused by the cyclone. It can also be seen that the migrant households’ monthly income was significantly higher than that of non-migrant households. Survey data also revealed that that prior to the disaster, migrant households’ average monthly income was higher than that of non-migrant households, but the difference was US$23 after Aila struck the communities (see Table 8). Based on the 2017 inflation rate, the average monthly income of migrant households was US$109 while non-migrant households earned US$86, which was also statistically significantly higher. The Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) (2011) report mentioned that, the average monthly household income of rural Bangladesh was US$115. From the FGDs, it was found that after the cyclone Aila in 2009, daily wages from off-farm employment also decreased to US$1–2. Their total working days also reduced to 7–10 days per month from 20–25 days. Thus, household income reduced primarily because of lack of employment opportunities [26].

Some respondents also claimed that their income increased after the cyclone as confirmed by 39 within-migrant household respondents and 21 respondents from non-migrant households. However, household expenses were enormous as a result of resource scarcity. Therefore, the increase in income did not cover adequately their necessities such as medicines, food, and children’s schooling, which resulted in their inability to recover fully from the losses caused by the Cyclone Aila. In some cases, they were compelled to sell household items to survive although FGDs revealed that migrants sent US$25–42 per month to their families.

Loan status

The loss and damage as a result of the cyclone Aila were so severe that the government, national and international donor agencies provided cash grants and other types of humanitarian support to affected communities to assist them in the recovery process. However, relief efforts were not adequate to recover from their losses, so vulnerable households had to loan from formal and informal institutions such as microfinance institutions (MFIs), friends/relatives, moneylenders, or from other sources [25]. Obtaining loans is considered one of the coping mechanisms after a disaster [10]. Table 9 presents the loan status of migrant and non-migrant households.

Table 9.

Loan status.

As shown in the table, approximately 47% of affected households obtained loans from different MFIs to recover from their losses at an average amount of US$39 migrant households and US$35 for non-migrant households. Post-Aila (2009), however, 36% of migrant households and 23% of non-migrant households were able to repay their loans while the remaining households remained in debt and struggling to repay the loans by installments. Participants in the FGDs revealed that some people borrowed money to rebuild their houses or invest in off-farm income-generating activities such as buying a vehicle, a rickshaw or van, or purchasing agricultural equipment i.e., boat, net, power tiller, and livestock. The Table 10 below presents the different ways loans were used by migrant and non-migrant households.

Table 10.

Uses of loan and proportion wise distribution.

Results from the survey (Table 10) illustrated that around 18% of the migrant households and 12% of the non-migrant households obtained loans to repair or maintain their assets like houses and vehicles. On the other hand, around 33% of migrant households invested their money on agricultural activities, while 48% of the non-migrant household invested on fish farming. Investments in agriculture and fish farming are significantly different. Furthermore, investments on off-farm activities were significantly higher among migrant households than non-migrant households, at around 34% and 24% respectively. Disaster loans certainly reduce the financial loss and create income-generating opportunities for affected households [58], but the loan repayment process can sometimes become a burden for the borrowers. As shown in this research, the affected coastal people faced problems in repaying their loans for various reasons as shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Problems of loan repayment.

As depicted in the table, the affected households were unable to repay their loan because of unemployment or limited employment opportunities, asset loss, and increased expenditure. The FGD participants also stated that their lack of skills in off-farm activities and less work opportunities led to their inability to repay the loans. Around 24% of the households surveyed claimed that the increasing household expenditure was another factor for not being able to pay the loan on time. Based on the household’s loan repayment status, it can be said that migration is a better strategy for reducing their financial liability.

3.5.2. Social Impacts

This section discussed the social impacts of Cyclone Aila on the migrant and non-migrant households with regard to their housing condition, water and sanitation issues, food consumption pattern, farmland holding, and source of fuel based on the findings from the field survey.

Housing Condition

Satkhira and Khulna suffered significantly from the tidal surge and waterlogging. As a result, thousands of the affected people were forced to relocate along the embankment or increased the level of land to protect their shelters [21,56]. According to the The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Joint Assessment Team (2010), around 243,191 houses were fully damaged while 370,587 were partially damaged. The study also found [59] that the houses were mostly damaged due to the breaches of the embankments and damages to the polder. After Aila struck the communities, around 18,421 houses were reconstructed with the assistance of the government, NGOs, and national and international organizations [26].

However, houses in the coastal areas were mostly constructed with mud, leaves, wood, and bamboo [8]. The traditional houses in the coastal areas were mostly Kacha (non-brick) houses constructed by the earthen wall with golpata plant (Nypa palm or mangrove palm), timber or bamboo roof, tin shaded wall and roof, and pucca houses built by bricks and wooden by tin and wood; wood collected from the nearby mangrove forest, Sundarban. Table 12 shows the housing conditions of migrant and non-migrant households before and after Aila.

Table 12.

Housing condition (before and after Aila).

The above table (Table 12) also revealed that, after Aila, both migrant and non-migrant households experienced a reduction in the number of Kacha houses while the number of semi-pucca and wooden houses increased. It can also be seen that, in non-migrant households, wooden and semi-pucca houses rose by 10% while kacha houses declined by around 23%. On the other hand, among the migrant households, the number of semi-pucca houses increased from 25% to around 57%, while kacha houses reduced by 36%. This illustrates that kacha houses were converted into wooden houses and semi-pucca. The tidal surge caused by the cyclone Aila broke the polders and collapsed around 90% of Kacha houses in the study areas; therefore, the affected people reconstructed their houses with wood or bamboo to prevent them from collapsing [60].

Furthermore, the FGDs showed that the villages and the households near Sundarban, the largest mangrove forest, were mostly forest dependent [10]. In the aftermath of the cyclone, the Forest Department informally permitted the affected people to cut trees and collect wood from Sundarban to rebuild their houses [10]. Since wood was easily available for the villagers, the number of wooden houses increased. Moreover, the government, NGOs, and national and international agencies supported the Aila-affected people in rebuilding their houses. A study conducted between 2010–2015 showed that around 90% of the households rebuilt their houses [60].

Water and Sanitation

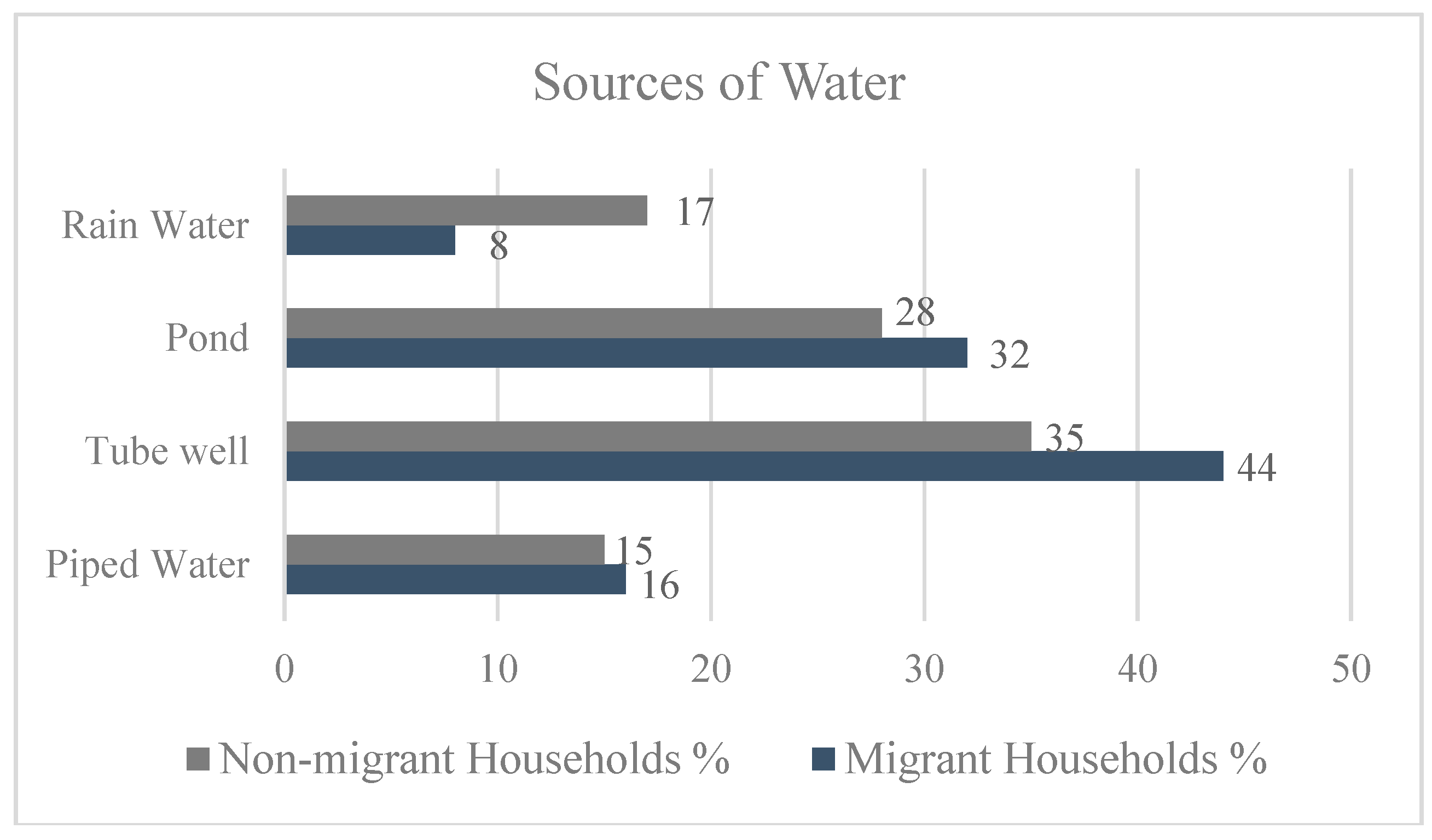

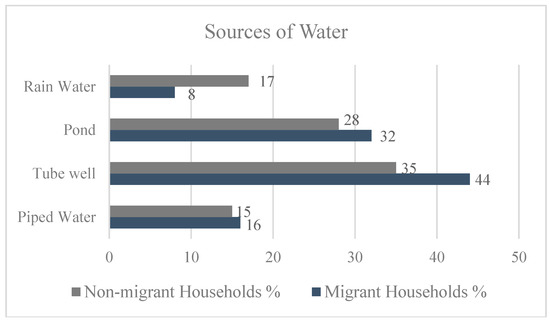

During the cyclone Aila (2009), water scarcity and salinity intrusion of groundwater increased. The people of the southwestern coastal zone are mostly dependent on surface water for their daily lives [20]. As the results from the field survey illustrate tube wells and small, isolated water tanks (ponds) were the major sources of water for both migrant and non-migrant households.

Figure 3 also revealed that around 35% of the non-migrant households and 44% of the migrant households were dependent on water from tube wells. In contrast, some households relied on water from ponds; about 28% for non-migrant households and 32% migrant households. Due to high tidal surges during the cyclone, most of the low-lying areas were submerged, contaminating the soil and water with salinity that caused massive water shortage [16,20,41]. The two main sources of water (i.e., tube wells and ponds) were unsuitable for consumption and for other domestic household work such as cooking, bathing, washing, etc. [19].

Figure 3.

Sources of water.

Under these circumstances, ‘rainwater harvesting’ was one of the alternative sources to access safe drinking water. This became an important strategy for coastal people while also reducing their dependency on other sources [44]. As a result, about 8% of migrant households and 17% non-migrant households adopted this technique through NGOs. However, harvesting rainwater was only possible for three or four months. This required people in some areas to travel far distances of 15–20 km or 2–3 hours a day in order to obtain safe drinking water. To address the water problem, the government, NGOs, national, and international organizations provided affected areas with drinking water for a certain period and helped rebuild the number of tube wells. Nevertheless, water supply was inadequate when compared with the demand. As a result, people had to find other sources of water.

In the study areas, sanitation coverage was around 80% before the cyclone struck the communities, and people used hygienic toilets [61]. However, Aila severely damaged all the toilets as they were made of mud, straw or plastic papers except the pacca (brick-built) latrines, which were, in the end, also inundated. The NGOs provided some temporary pit latrines (one latrine allocated to 15 households on an average), but the number was not adequate for the affected people such as [59] thus they used river or brushwood. FGDs also showed that acute drinking water shortage worsened the sanitation system, as well as salinity of water, increased skin and water-borne diseases such as diarrhea, cholera, food poisoning, etc. particularly among women and children. Data shows around 40% of people were affected by water-borne diseases, but not a single person died.

Food Consumption Pattern

Food scarcity has been a very common phenomenon in any post-disaster situation. Cyclone Aila, for instance, had a long-term impact on crop production, fisheries, and pure water supply [39]. Long-term inundation resulting in saline intrusion due to the cyclone had affected much of the agricultural land, which caused serious problems like loss of crops and vegetable production. Consequently, a considerable area of crop fields was converted into fish farms after Aila, which affected the food production and consumption pattern of the affected coastal people. Table 13 reflects the food consumption pattern of migrant and non-migrant households.

Table 13.

Food consumption pattern (weekly).

The above table displays the weekly food consumption pattern of the households in the aftermath of the cyclone as represented by the number of weekly meal intakes of migrant and non-migrant households. The percentages also illustrate that there were far more non-migrant households that consumed only two meals a day, at approximately 42%, compared to only 23% for migrant households When comparing the two groups of households, it can be seen from the table that 40% of the non-migrant households 17% of the non-migrant households could afford three full-daily meals. In contrast, there were more migrant households who had three half-daily meals and three full-daily meals, at 48% and 29% respectively and the results were found to be statistically significant. Thus, there was clear evidence that shifting occupations through migration had enormous impacts on food consumption patterns of households.

Food consumption patterns also depend on the availability of natural resources and productivity [62]. During Aila, around 90% of the affected people shortened their meal intakes; for instance, those we were affected skipped meals once or twice a day [23]. The main reasons could be low income and crop loss, but there might be other factors like agricultural losses and change in soil pattern that affected productivity. Insufficient food intake or daily calories caused serious malnutrition especially the children and elderly people [12]. However, reducing food consumption is considered a coping strategy after a disaster [63].

Food scarcity also increased after the cyclone, which affected food prices; thereby, increasing the food expenditures of people. Moreover, participants in the FGDs claimed that the calamities were so severe that the affected households sometimes had to sell their labor in advance at a very cheap price. Some households were also compelled to mortgage whatever remaining assets they had to middlemen at very low prices to buy food [30].

The main limitation of the research was the absence of data related to the amount of food consumed by household members per meal/per day. The research could not estimate the calorie intake by the household members. The link between climatic events, migration, and food insecurity already has been established [31]. The UNDP (2010) reported that the increase in food insecurity after the cyclone might have been another reason for human migration [21]. This research also found that food insecurity and low consumption patterns due to the climatic event (i.e., Cyclone Aila) induced human migration.

Farmland Holding

Climatic events severely affected agricultural land, which may have changed the land use pattern [64]. Research study [65] revealed that due to long-term waterlogging and saline intrusion during the cyclonic storm Aila, agricultural croplands became unproductive in the southwestern part of the coastal areas. Table 14 displays the effects of farmland ownership on migrants and non-migrant households before and after the cyclone.

Table 14.

Farmland ownership of the households—before and after Aila.

Table 14 shows that after the cyclone, the number of smallholders (or owners of 1.5 or more acres of farmland) in migrant households decreased, while the functionally landless (with 0–0.49 acres of land) and marginal farmers (acquired 0.50–1.49 acres of farmland) rose significantly. Results from the FGDs also showed that long-term coastal flooding and waterlogging increased soil salinity in the degraded agricultural lands after the cyclone. Therefore, farmers were compelled to change their sources of income to alternative income-generating activities such as off-farm activities. The loss of agricultural lands also threatened their livelihood opportunities, which triggered migration.

Although shrimp cultures were profitable businesses, smaller plots were not appropriate for shrimp cultivation; thus, farmers with large farmlands sold or leased out their lands for shrimp culture and became medium and small-scale farm holders. As a result, huge amounts of agricultural lands were transformed into shrimp farming within a few years in the coastal areas of southwest Bangladesh. The research also found that due to the disparity in land ownership, migrant households leased out or sold their lands before leaving the study areas.

Climate change also affected the land use pattern in the study areas, Koyra and Shymnagar, which led to the reduction in the average land size. In 2008, prior to the Cyclone Aila, the average land size was 157.02 hectares. This reduced to 99.89 hectares the following year, after the cyclone [65]. The loss of agricultural lands also threatened the livelihood opportunities of the farmers, which considerably affected their living standard. Gray (2011) examined the decline in soil quality of agricultural land, which negatively affected production and may have led to diversification in income sources and induced human migration [49].

Sources of Fuel

The affected households were highly dependent on natural resources for their livelihood especially the poor households [10]. However, kerosene and fuelwood were the key sources of fuel for the households living in the southwestern coastal zone. Table 15 presents the sources of fuel of the affected households after the cyclone Aila.

Table 15.

Sources of fuel.

The survey results showed that approximately 61% of the migrant households and 50% of the non-migrant households used kerosene as a source of fuel after the cyclone. On the other hand, some households used solar energy, at 32% for migrant households and 42% for non-migrant households. Findings from the FGDs depicted that the government, NGOs and other donor agencies provided and installed solar panels for the affected households.

The results also demonstrated that close to 86% of the total households were dependent on the natural resources as a source of fuel for cooking, from where they collected fuel in the form of biogas, cow dung, and fuel wood particularly from the village and nearby mangrove forest. In contrast, around 14% of the households purchased fuel (e.g., kerosene, LPG) from the market. During the recovery process, the forest department formally allowed the affected households to collect fuelwood from Sundarban due to scarcity of resources [10]. Field data showed that there was a marginal difference between migrants and non-migrant households’ use of fuel for cooking.

3.6. Migration

The factors that induced migration after the cyclone were also analyzed. Using the logistic regression model (Appendix A), the results show that factors like households who were functionally landless (0.1–0.49 acres); more interested to migrate. The statistical results also revealed that the probability of getting migrated due to changing occupation was about two times more than without changing one’s occupation. Moreover, households who consumed could not afford three meals a day were pushed to migrate. The analysis also showed that age of the migrant and educational attainment was significantly positively correlated with migration; they were more likely to migrate. The capability to acquire knowledge about adaptation strategies, awareness, and opportunity for alternative sources of income, fearless of taking challenges influenced them to take the decision to migrate [15]. Moreover, more economically active household members were 2.5 times more likely to be influenced to migrate. Their strong skills, willingness to take risks, social network, and access to information and job opportunities were the main factors that increased the likelihood of migrating. The analysis depicted that the type of house was also positively correlated with migration. Households who belong better housing (semi-pacca or pacca) infrastructure were more likely to migrate. Results from the logistic regression analysis showed that households who obtained loans and failed to repay their debts were also more likely to migrate or induced more migration.

4. Concluding Remarks

This paper focused on the impacts of the cyclone Aila in 2009 on the socio-economic conditions of migrant and non-migrant households in the southern part of the coastal areas of Bangladesh. The research was conducted in Koyra sub-district in Khulna and in Shymnagar in Satkhira district. The devastation of the cyclone had considerably affected the coastal communities, economically and socially. Furthermore, some people decided to migrate to look for alternative solutions to their problems as a result of the cyclone, while some stayed behind. The unit of analysis was migrant and non-migrant households. A comparative analysis on the socioeconomic conditions post Aila between migrant and non-migrant households.

Results from the study revealed that the cyclone adversely people’s income, occupation, housing, food consumption, and croplands. Although the affected communities received external assistance and adopted various responsive strategies to recover their losses, the strategies may not be effective in the long term [43]. Evidence showed that the short-term strategies and insufficient external assistance failed to reduce the hardships of the cyclone-affected households, which induced out-migration [19,47].

As discussed in the previous sections, the findings revealed that during the cyclone, the severe storm and prolonged water logging resulted in increased salinity in both water and soil, which had a considerable impact on agriculture and fishing or aquaculture; shrimp farming [10,39]. Therefore, agricultural land became unproductive, and the enormous crop failure and reduced crop production threatened their livelihood opportunities, which forced some households to diversify their sources of income [22]. Moreover, the cyclone devastated the farmers just before harvesting, leaving them with massive financial losses inducing migration. From the survey, it was found that the number of small landholders in migrant households decreased, while functionally landless and marginal farmers significantly rose. The FGDs participants argued that migrant households with farmland holders sold or leased out their lands before leaving and became medium and small landholders. On the other hand, the polders that protected shrimp farms have collapsed due to the high pressure of tide; thus, waterlogging and salinity affected the shrimp farms drastically. Moreover, the lingering reconstruction of the embankment also increased soil salinity two years after Aila; thus, the recovery of shrimp farms was impossible for some farmers [56], which may have influenced them to diversify from farm to non-farm or off-farm activities, which also triggered migration.

The findings of this paper also revealed that affected households took loans from informal and formal institutions; however, the repayment status of loans among migrant households was statistically significantly higher than that of non-migrant households. The outcome also showed that the average monthly income of migrant households was higher than that of non-migrant households. Based on these findings, it can be said that migration is a better strategy in terms of increasing income or reducing liability due to loans. Furthermore, the number of houses (Kacha houses) reduced migrant households while semi-pucca and wooden houses increased, showing that a higher income also impacts a household’s housing conditions.

According to the field survey, tube wells and ponds were the major sources of water for the households. Post cyclone Aila high tidal surges contaminated soil and water by salinity. Therefore, rainwater harvesting becomes another option for the affected households. Moreover, post-Aila food insecurity increased affected the food consumption pattern of coastal people. The crisis became so severe that affected people were forced starvation two or three times a day during Aila. Findings show post-Aila food intake among migrant households was significantly higher than non-migrant households. This was clear evidence that shifting occupation through migration had an enormous impact on food consumption patterns.

The outcome of this research reveals that migrating households were better equipped to recover from their losses and their socio-economic conditions in terms of income, housing, food consumption, and repayment of the loan than non-migrant households. Considering these aspects, it can be argued that migration or shifting livelihood options could be a better strategy for affected households dealing with climatic events (for example cyclone Aila). Thus, the experiences from the cyclone Aila can be helpful for coastal people for preparing the vulnerable population for future climatic events like Aila.

Using the logistic regression model (Appendix A), the results show that factors like household land ownership after Aila, change in occupation, food consumption pattern, age of migrant, educational attainment of migrant, economically active member, type of house, and debt were significantly associated with migration.

These findings of this research could be useful considering the limitation i.e., health (physical, mental, social, and psychological), gender role, culture, marriage, family reunion, and education, which did not cover. During the survey, only the households that experienced internal migration were considered although international migration also occurred post-Aila because the time, the cost for internal and international migration was different.

Furthermore, the outcome of this research could be a contribution to a growing body of knowledge in an area where there are evident gaps. It could give direction for policymakers, researchers to understand the impacts of climatic events (i.e., cyclone Aila) and how migration affects households. The study could be useful to develop and refine policies to recover from a similar kind of climatic events in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3263/9/11/482/s1, Table S1: Climate Change and Migration: A Case study of Coastal area in Bangladesh, Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and M.M.A.; methodology, R.S. and M.M.A.; software, R.S.; validation, R.S. and M.M.A.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, R.S. and M.M.A.; resources, R.S. and M.M.A.; data curation, R.S. and M.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.; writing—review and editing, R.S. and M.M.A.; visualization, R.S. and M.M.A.; supervision, M.M.A.; project administration R.S. and M.M.A.; funding acquisition, R.S.

Funding

This research was funded by Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Ref: 5256-11/IPCC/SCO.

Acknowledgments

“This document was produced with the financial help of the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation. The contents of this document are solely the liability of Ms. Rizwana Subhani and under no circumstances may be considered as a reflection of the position of the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation and the IPCC”. We would like to thanks to Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) for partial funding support for this research and indebted to Rajendra P. Shrestha, Soparth Pongquan, Sylvia Szabo, Indrajit Pal, Abha Mishra for their generous support throughout the research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Variables with their units of measurement and coding.

Table A1.

Variables with their units of measurement and coding.

| Socio Economic Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Land Ownership After Aila (Dummy) | Dummy, takes the value of 1 if the household obtained own land and 0 otherwise |

| Change in Occupation (Dummy) | Dummy, takes the value of 1 if the head of the household changed his/her occupation due to Aila and 0 otherwise |

| Food Consumption Pattern (Dummy) | Dummy, takes the value of 0 if households consume less than three meals a day and 1 otherwise |

| Age of Migrant (Dummy) | Dummy, takes the value of 1 if migrant person is below 50 years old and 0 otherwise. |

| Educational Attainment of Migrant (Dummy) | Dummy, takes the value of 1 if the migrant person is literate and 0 otherwise |

| Economically Active Member (Dummy) | Dummy, takes the value of 1 if households where more than 1 member involved in economic activities and 0 otherwise |

| Type of House (Dummy) | Dummy, takes the value of 1 if the house better (not kacha) and 0 otherwise |

| Debt (Dummy) | Dummy, takes the value of 1 if the household is under debt and 0 otherwise |

Table A2.

Logistic regression.

Table A2.

Logistic regression.

| Socio Economic Variables | B | S.E. | Sig. | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Ownership after Aila | −1.768 | 0.322 | 0.000 | 0.171 |

| Change in Occupation | 0.754 | 0.347 | 0.030 | 2.126 |

| Food Consumption Pattern | 1.261 | 0.350 | 0.000 | 3.527 |

| Age of Migrant | 1.058 | 0.392 | 0.007 | 2.882 |

| Educational Attainment of Migrant | 0.837 | 0.315 | 0.008 | 2.309 |

| Economically Active Member | 0.923 | 0.341 | 0.007 | 2.518 |

| Type of House | 0.983 | 0.321 | 0.002 | 2.673 |

| Debt | 1.077 | 0.320 | 0.001 | 2.937 |

| Constant | −3.210 | 0.698 | 0.000 | 0.040 |

References

- Brown, O. Climate Change and Forced Migration: Observations, Projections and Implications (No. HDOCPA-2007-17); Human Development Report Office (HDRO), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, R.; Karuppannan, S.; Kellett, J. Climate Migration and Urban Planning System: A Study of Bangladesh. Environ. Justice 2011, 4, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N. Environmental Refugees: An Emergent Security Issue. In Proceedings of the 13th Economic Forum, Prague, Czech Republic, 23–27 May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Aid. Human Tide: The Real Migration Crisis; Christian Aid: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank. Adapting to Climate Change, Strengthening the Climate Resilience of the Water Sector Infrastructure in Khulna, Bangladesh; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyon, Phillippines, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, R.; Khan, H.T.; Ball, E.; Caldwell, K. Climate Change Impact: The Experience of the Coastal Areas of Bangladesh Affected by Cyclones Sidr and Aila. J. Environ. Public Health 2016, 2016, 9654753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, M.G.; Rahman, A.A.; Islam, N. Climate Change and Sea Level Rise: Issues and Challenges for Coastal Communities in the Indian Ocean Region. In Coastal Zones and Climate Change; Michael, D., Pandya, A., Eds.; The Henry L. Stimson Centre: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.U. Assessment of Vulnerability to Climate Change and Adaptation Options for the Coastal People of Bangladesh; Practical Action: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huq, M.; Khan, M.F.; Pandey, K.; Ahmed, M.M.Z.; Khan, Z.H.; Dasgupta, S.; Mukherjee, N. Vulnerability of Bangladesh to Cyclones in a Changing Climate: Potential Damages and Adaptation Cost; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, A.N.M.; Zander, K.K.; Myers, B.; Stacey, N.; Garnett, S.T. A short-term Decrease in Household Income Inequality in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh, following cyclone Aila. Nat. Disaster Springer 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan 2009. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/content/bangladesh-climate-change-strategy-and-action-plan-2009 (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Shamsuddoha, M.; Khan, S.M.M.H.; Raihan, S.; Hossain, T. Displacement and Migration from the Climate Hotspots: Causes and Consequences; Center for Participatory Research and Development and ActionAid: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, T.K.; Kabir, A.E.; Ghosh, G.C. Impact and Adaptation to Cyclone Aila: Focus on Water Supply, Sanitation and Health of Rural Coastal Community in the South West Coastal Region of Bangladesh. J. Health Environ. Res. 2016, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameem, M.I.M.; Momtaz, S.; Rauscher, R. Vulnerability of rural livelihoods to multiple stressors: A case study from the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 102,, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, C.K.; Gupta, V.; Chattopadhyay, U.; Amarayil Sreeraman, B. Migration as adaptation strategy to cope with climate change: A study of farmers’ migration in rural India. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 10, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehedi, H.; Nag, A.K.; Farhana, S. Climate Induced Displacement; Case Study of Cyclone Aila in the Southwest Coastal Region of Bangladesh; Coastal Livelihood and Environmental Action Network: Khulna, Bangladesh, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Torresan, S.; Zabeo, A.; Rizzi, J.; Critto, A.; Pizzol, L.; Giove, S.; Marcomini, A. Risk Assessment and Decision Support Tools for the Integrated Evaluation of Climate Change Impacts on Coastal Zones. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software, Ottawa, Canada, 1 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Khole, M. Inter-annual and Decadal Variability of Sea Surface Temperature (SST) Over Indian Ocean. Mausam 2005, 56, 803. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.U.; Neelormi, S. Climate Change, Loss of Livelihoods and Forced Displacements in Bangladesh: Whither Facilitated International Migration; Campaign for Sustainable Rural Livelihoods and Centre for Global Change: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.R.; Hasan, M. Climate-induced Human Displacement: A Case Study of Cyclone Aila in the South-west Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards 2016, 81, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint, U.N. Multi Sector Assessment & Response Framework. 2010.“Cyclone Aila.”; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nishat, A.; Mukherjee, N.; Hasemann, A.; Roberts, E. Loss and Damage from the Local Perspective in the Context of a Slow Onset Process. Cent. Clim. Chang. Environ. Res. 2013, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, K.M.N. A Study of the Principal Marketed Value Chains Derived from the Sundarbans Reserved Forest; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DMIC. Summary of Cyclonic Storm Aila. Disaster Management Information Centre; Disaster Management Bureau (DMB), Ministry of Food and Disaster Management: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, B. 2014, Cyclone-INDUCED Migration in Southwest Coastal Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262184884 (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Jahan, I. 2012: Cyclone Aila and the Southwestern Coastal Zone of Bangladesh: In the Context of Vulnerability. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Akter, S. Climate Change Pattern in Bangladesh and Impact on Water Cycle; ITN-BUET, Centre for Water Supply and Waste Management: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2011; ISBN 978-984-33-4357-4. [Google Scholar]

- Neelormi, S.; Adri, N.; Ahsan, A.U. Adaptation to Water Logging Induced Vulnerability to Women in Bangladesh, CGC 003; Centre for Global Change (CGC): Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, B. Population Displacement after Cyclone and its Consequences: Empirical Evidence from Coastal Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Kumar, U.; Mehedi, H.; Sultana, T.; Ershad, D.M. Initial Damage Assessment Report of Cyclone Aila with focus on Khulna District. Unna. Onneshan-Humanit. Watch-Nijera Kori Khulna Bangladesh 2009, 31, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.R. Climate Change, Natural Disasters and Socioeconomic Livelihood Vulnerabilities: Migration Decision Among the Char Land People in Bangladesh. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 136, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartiki, K. Climate Change and Migration: A Case Study from Rural Bangladesh. Gend. Dev. 2011, 19, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBS. Population Census; Government of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halcrow-WARPO. National Water Management Plan Project, Draft Development Strategy, AnnexO: Regional Environmental Profile; Halcrow and Partners, and Water Resources Planning Organization (WARPO): Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2001; Volume 11, pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R.; Walkerden, G. How do links between households and NGOs promote disaster resilience and recovery? A case study of linking social networks on the Bangladeshi coast. Nat. Hazards 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, C.R. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques; New Age International: New Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.R.; Hossain, D. Island Char Resources Mobilization (ICRM): Changes of Livelihoods of Vulnerable People in Bangladesh. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 117, 1033–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Islam, M.R. Ultra-poor Char People’s Rights to Development and Accessibility to Public Services: A Case of Bangladesh. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddoha, M.; Islam, M.; Haque, M.A.; Rahman, M.F.; Roberts, E.; Hasemann, A.; Roddick, S. Local Perspective on Loss and Damage in the Context of Extreme Events. Insights from Cyclone-affected Communities in Coastal Bangladesh. Loss and Damage in Vulnerable Countries Initiative. 2013. Available online: https://www.lossanddamage.net/download/7105.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- McLeman, R.A. Climate and Human Migration: Past Experiences, Future Challenges; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, U.; Baten, M.A.; Al-Masud, A.; Osman, K.S.; Rahman, M.M. Cyclone Aila: One Year on Natural Disaster to Human Sufferings; Unnayan Onneshan: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, J.N.; Esnard, M.A.; Sapat, A. Population Displacement and Housing Dilemmas Due to Catastrophic Disasters. J. Plan. Lit. 2007, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.; Van der Geest, K.; Huq, S.; Harmeling, S.; Kusters, K.; de Sherbinin, A.; Kreft, S. Evidence from the Frontlines of Climate Change: Loss and Damage to Communities Despite Coping and Adaptation; United Nations University-Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS): Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani, G.; Rahman, S.H.; Faulkner, L. Impacts of Climatic Hazards on the Small Wetland Ecosystems (Ponds): Evidence from Some Selected Areas of Coastal Bangladesh. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1510–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, H.; Skoufias, E. Risk, Financial Markets, and Human Capital in a Developing Country. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1997, 64, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoufias, E.; Parker, S.W. Labor Market Shocks and their Impacts on Works and Schooling; Evidence from Urban Mexico, IFPRI-FCND discussion paper; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, O. Migration and Climate Change IOM Migration, Research Series 31; International Organization for Migration: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Report of Working Groups II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, C.L. Soil Quality and Human Migration in Kenya and Uganda. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S. Adaptable Livelihoods: Coping with Food Insecurity in the Malian Sahel; Macmillan: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- BBS. Report of the Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2010; Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Division, Ministry of Planning: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S.; Rahman, H.; Shahid, S.; Khan, R.U.; Jahan, N.; Ahmed, Z.U.; Khanum, R.; Ahmed, M.F.; Mohsenipour, M. The Impact of Cyclone Aila on the Sundarban Forest Ecosystem. Int. J. Ecol. Dev. 2017, 32, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, R.; Kellett, J.; Karuppannan, S. The International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses Volume 5. 2014. Available online: https://on-climate.com/journal (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Hussein, K.; Nelson, J. Sustainable Livelihoods and Diversification. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/66529?show=full (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Mallick, B.; Rahaman, K.R.; Vogt, J. Coastal Livelihood and Physical Infrastructure in Bangladesh after Cyclone Aila. Mitig. Adapt. Strategy Glob. Chang. 2011, 16, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiba, U.; Md Anwarul, A.; Rajib, S.; Abu Wali, R.H. Salinity-induced Livelihood Stress in Coastal Region of Bangladesh. In Water Insecurity: A Social Dilemma; Anwarul, A., Habiba, U., Rajib, S., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S.; Mallick, B. The Poverty Vulnerability Resilience Nexus: Evidence from Bangladesh. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 96, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.S.; Ratner, B.D.; Hall, S.J.; Pimoljinda, J.; Vivekanandan, V. Coping with Disaster: Rehabilitating Coastal Livelihoods and Communities. Mar. Policy 2006, 30, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsham, M. Assessing the Evidence: Environment, Climate Change and Migration in Bangladesh; International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Office for South Asia: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik, M.S.; Nakagawa, H.; Rahman, M.R.; Shaw, R.; Kawaike, K.; Parvin, G.A.; Fujita, K. Humanitarian Aid Driven Recovery of Housing after Cyclone Aila in Koyra, Bangladesh: Characterization and Assessment of Outcome. J. JSNDS 2018, 37, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cluste, W. Learning and Knowledge Sharing Workshop on Response to Cyclone Aila; WaterAid and UNICEF: Khulna, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The Future Food and Agriculture-Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.K.; Routray, J.K. Flood Proneness and Coping Strategies: The Experiences of Two Villages in Bangladesh. Disasters 2010, 34, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasneem, S.; Shindaini, A.J.M. The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture and Poverty in Coastal Bangladesh. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 3, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, M.A.; Shamsuddoha, M.; Islam, M.; Haque, M.A.; Rahman, M.F.; Roberts, E.; Hasemann, A.; Roddick, S. Qualitative Survey Assessing Impacts from Cyclone Sidr and Aila on the Communities of Koyra and Gabura, Bangladesh; Center for Participatory Research and Development (CRPD): Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).