Abstract

This study presents an integrated geophysical–geomatic approach for the investigation of archaeological sites, combining low-frequency Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) and close-range photogrammetry at the Archaeological Park of Abellinum (southern Italy). Unlike conventional applications using high-frequency antennas, the low-frequency GPR system employed in this study enabled deep subsurface imaging, allowing reconstruction of buried stratigraphic and architectural features to depths of several metres. This enhanced penetration capacity facilitated a more comprehensive understanding of the investigated environments, by complementing rather than replacing high-frequency surveys and expanding the interpretable volume in complex urban and peri-urban contexts. GPR reflection data were integrated with high-resolution photogrammetric surface models, enabling direct comparison between visible structures and subsurface geometries. The combined dataset provided precise correlations between surface features and subsurface anomalies, demonstrating the potential of this integrated methodology for detailed archaeological interpretation. Overall, this approach offers a scalable, non-invasive framework applicable to other complex archaeological landscapes, supporting both research objectives and long-term heritage management. By systematically combining low-frequency GPR with high-resolution photogrammetry, the study introduces a methodological contribution that extends interpretative depth well beyond the limits of conventional surveys.

1. Introduction

Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) has become a cornerstone in archaeological prospection, enabling the detection and mapping of subsurface features without excavation. Since its first applications in the 1970s and 1980s [1,2,3,4,5], GPR has been widely employed to identify buried walls, foundations, roads, tombs, and other anthropogenic structures [6,7], as well as to investigate stratigraphic sequences and settlement organisation [8,9,10,11]. Archaeological GPR surveys have traditionally relied on medium-high frequency antennas (250–1000 MHz) [12,13,14,15], which provide high spatial resolution and allow precise imaging of shallow structures, generally within the first 1–2 m of the subsurface. At these frequencies, vertical resolutions in the order of a few centimetres can be achieved, allowing the delineation of fine architectural details such as wall thicknesses, flooring systems, and burial features [16,17].

High-frequency GPR has proven effective in a variety of archaeological contexts, including urban sites, cemeteries, and complex architectural remains, where the identification of walls, floors, and graves requires high resolution [18,19,20,21]. Applications have also extended to heritage conservation, where GPR can detect voids, cracks, and hidden cavities without disturbing structures [22,23]. Furthermore, time-slice analyses and three-dimensional reconstruction of radar data have enabled detailed spatial analysis of archaeological features, improving interpretation and site management [24,25,26,27,28,29]. These advances have progressively transformed GPR from a primarily exploratory technique into a quantitative tool for spatial modelling and volumetric characterisation of buried archaeological landscapes.

However, the main limitation of high-frequency systems lies in their low penetration depth, which is strongly influenced by soil composition, moisture, and heterogeneity [30,31]. In areas with thick alluvial deposits, colluvial layers, or buried urban stratigraphy, important subsurface structures often lie beyond the detection range of conventional antennas [32]. This limitation is especially critical in multi-layered archaeological contexts, where deep cultural accumulations can exceed the typical penetration capabilities of 250–1000 MHz systems. To overcome these limitations, low-frequency GPR systems (<100 MHz) have been increasingly considered in recent years [24,33,34,35,36,37]. Although less common in archaeological practice, these systems provide greater depth penetration, typically reaching several metres below the surface, allowing the detection of large architectural foundations, deep stratigraphic interfaces, and buried infrastructures [38]. Low-frequency antennas are particularly sensitive to large-scale dielectric contrasts and are therefore well suited for investigating deeply buried masonry, paleo-topographies, and major anthropogenic modifications of the subsoil [36].

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of low-frequency GPR in imaging deep structural features, the technique inherently provides limited resolution for fine architectural details due to its broader wavelength [4,39]. As a consequence, narrow walls, thin occupation layers, or small-scale installations may fall below the detection threshold and appear only as diffuse or amalgamated reflections [9,32]. This limitation underscores the complementary role of low- and high-frequency systems in achieving multi-scale archaeological prospection [40].

Despite the reduced spatial resolution associated with lower frequencies, low-frequency GPR has proven effective in several archaeological studies, particularly in urban and monumental sites, where subsurface complexity requires deep imaging. It should be noted that low-frequency impulsive GPR, as employed here, operates on a different principle than stepped-frequency continuous wave (SFCW) systems. While SFCW achieves higher resolution using the high-frequency portion of its spectrum, our impulsive approach prioritises penetration and large-scale feature detection. These methods are therefore not directly comparable in terms of depth-resolution trade-offs.

The combination of low-frequency GPR with complementary methods [41], such as photogrammetry or other geophysical techniques, enables a comprehensive reconstruction of both subsurface and exposed structures, providing insights into settlement organisation, construction techniques, and site evolution that would otherwise remain inaccessible [36]. Integrated multi-sensor approaches reduce interpretative ambiguity by allowing surface-derived geometric constraints to be directly compared with geophysical anomalies [42,43,44,45].

This technological shift is particularly relevant in archaeologically complex contexts such as Abellinum, where deep stratigraphy, multi-phase occupation, and extensive buried structures require survey methods capable of penetrating several metres below the ground while maintaining architectural-scale interpretability.

In this study, an integrated L.F.GPR–photogrammetry methodology is applied to the Archaeological Park of Abellinum (southern Italy). The research aims to reconstruct buried structures to several metres’ depth, compare them with visible remains, and provide a robust framework for subsurface–surface integration. The specific objectives include: (i) evaluating the effectiveness of low-frequency GPR in a volcanoclastic and alluvial geological setting, (ii) identifying the geometric relationships between emerging and buried architectural remains, (iii) assessing the potential of combined GPR and photogrammetric datasets for supporting archaeological interpretation and heritage management and (iv) establishing a reproducible workflow for integrating deep GPR imaging with high-resolution surface documentation in complex archaeological stratigraphies.

1.1. Geological and Geomorphological Setting

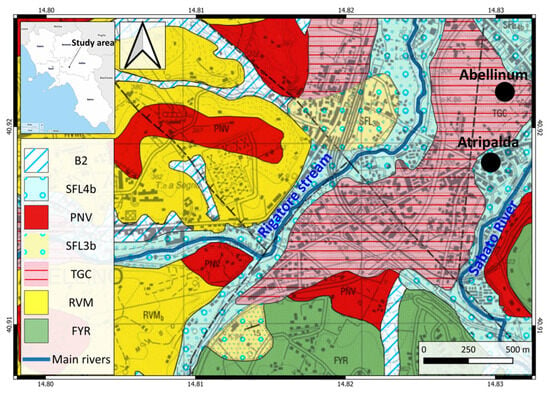

The Archaeological Park of Abellinum is located in the Campania region, southern Italy (Figure 1), within the modern municipality of Atripalda (province of Avellino).

Figure 1.

Location of the Archaeological Park of Abellinum (Campania, southern Italy) and geological setting of the study area within the Sabato River valley (modified from [46]). B2 (eluvial-colluvial deposits): alternation of sandy-arenaceous and weathered volcanoclastic deposits, with fall-out pyroclastic deposits, buried soils and isolated clasts of well-rounded limestones (Holocene-present); SLF4b (Calore River synthem, Ufita River sub-synthem): polygenic and heterometric gravels with a sandy-silty matrix of fluvial environments and intercalations of lenses of clayey silts, weathered volcanoclasts and fall-out pyroclastic deposits and paleosols (Holocene p.p.); PNV (Piano delle Selve unit): fall-out pyroclastic deposits, consisting of ash and pumiceous lapilli from Plinian eruptions of the Somma-Vesuvius and Campi Flegrei volcanoes (Holocene); SFL3b (Calore River synthem, Benevento sub-synthem: polygenic and heterometric gravels with a sandy-silty matrix, alternating with layers of silty sands and clayey silts, including also paleosols and fall-out deposits of the Somma-Vesuvius and Campi Flegrei volcanoes (Holocene); TGC (Campanian Grey Tuff): dark grey or yellowish scoriaceous cineritic tuff, generally lithified with composition from trachyte to hyperalkaline phonolitic trachyte (39 ka [47]); RVM (Ruvo del Monte synthem): layered conglomerates, lenses and banks with coarse sand intercalations, reddish yellow sandy matrix microconglomerates (Middle Pliocene); FYR (Flysch Rosso Fm.): alternating red-green limestones, marls and clays, greenish-grey calcarenites, lithoclastic calcirudites and calcareous breccioles (Upper Cretaceous-Lower Miocene).

The investigated site was strategically built on the top of the TGC terrace that is 20–25 m hanging over the Sabato river floodplain, offering a dominant position over the valley (Figure 1). Its topographical setting has historically favoured human settlement due to accessibility, defensive advantages, and wide availability of fertile soils.

Given the geological complexity of the Sabato valley and the superimposition of volcanic, colluvial, and anthropogenic deposits, a synthetic overview of the major stratigraphic units is essential for contextualising the behaviour of electromagnetic waves in this environment. The following stratigraphic description therefore provides the necessary framework for understanding both GPR penetration depth and the reflectivity contrasts observed in the processed data.

The Abellinum hill is shaped by a plate of cineritic tuff, part of the pyroclastic density current deposits associated with the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption of the Phlegraean Volcanic Area, dated to approximately 39.85 ± 0.14 ka [46,47,48]. The presence and mechanical behaviour of this volcanic rock favoured its use as a building material at various times; evidence of this exploitation is provided both by the material from which some walls found at the site are built and by the Ganci quarry, located near the site, operational until the beginning of the 20th century [49]. To the top of the Campania Ignimbrite terrace, a pedo-volcanic stratigraphic succession is present. From the bottom to the top, it is made up of a well-developed and thick palesol containing also weathered whitish and reddish volcanoclastic fall-deposits of the Pomici di Mercato eruption (8.9 ka [50]) from Vesuvius volcano and Agnano M. Spina eruption (4.4 ka [51]). This paleosol is buried by a 15–20 cm whitish pumiceous and cineritic fall deposit of the vesuvian eruption of the Pomici di Avellino (3.9 ka [52]). Within paleosol, some archaeological findings of the Early Bronze Age (cups, Appennine Culture, Middle Bronze age) were discovered several years ago [53,54]. The stratigraphy above of the Pomici di Avellino layer is strongly modified by man-made activities during the last millennia. Archaeological structures of Abellinum locally were found directly on pre Avellino paleosol and mainly on weathered and pedogenized volcaniclastic deposits of the eruption. The archaeological layers related to the Abellinum ancient cities were interfingered by the fall deposits (mainly mm pumices and greyish ashes) of the Pollena eruption from Vesuvius volcano (472 CE [55]). Also recent agricultural changes carried out during last centuries for nut cultivations strongly modified the upper part of the stratigraphy.

The stratigraphy and sedimentary properties significantly influence GPR signal penetration and resolution, with low-frequency antennas particularly suited for imaging deeper buried structures within these heterogeneous deposits.

From a geomorphological perspective, the site lies in a transitional zone between alluvial plains and hill slopes, where fluvial incision, slope processes, and minor tectonic activity have shaped the landscape. In fact, the adjacent valley is composed of Holocene sedimentary sequences of the Sabato River and the Rigatore stream. These deposits consist of polygenic and heterometric gravels embedded in a sandy-silty matrix, interbedded with lenses and layers of silty sands and clayey silts [46]. Such heterogeneous near-surface setting induces a spatially variable electromagnetic attenuation, making low-frequency antennas particularly advantageous for stabilising penetration depth and allowing the detection of large-scale architectural features otherwise invisible to high-frequency systems. Although the primary archaeological area is located on the hilltop, the variable composition of nearby alluvial and fluvial deposits influences GPR signal propagation, reinforcing the choice of low-frequency antennas for maintaining penetration and reliable imaging of large-scale subsurface structures. In this sense, the geomorphological setting acts as a mediating factor between geological variability and the archaeological visibility of subsurface features, further reinforcing the need for a low-frequency approach capable of maintaining penetration in complex dielectric conditions. This heterogeneity influences both wave scattering and signal absorption, making the selection of antenna frequency a critical parameter for effective subsurface imaging. The combination of relatively stable terraces and fine sedimentation has contributed to the preservation of buried archaeological remains, while also presenting challenges for non-invasive investigation due to variable soil conductivity and heterogeneous layering.

The study area has been struck by some relevant strong historical earthquakes of Southern Italy, among the others, the Sannio 1688 (Imax 11), Sannio-Irpinia 1456 (Imax 11), Irpinia 1732 (Imax 10.5), Molise 1805 (Imax 10), 1980 Irpinia-Basilicata (Imax 10), 346 CE Sannio (Imax 9 [56,57]). This last represents a cardinal event for the Abellinum settlement as clued by the coseismic collapse of columns in the peristyle of a domus that can be associated with this earthquake occurrence [53,58,59].

1.2. Historical and Archaeological Background

The ancient settlement of Abellinum developed on the Civita plateau, between the left bank of the Sabato River and the Rigatore stream in a position that ensured a favourable location for controlling the territory and the road traffic between the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic coasts [49,60]. The plateau, frequented already in the Bronze Age [61], appears to have been stably occupied between the 4th and 3rd centuries BC; to this phase belong a sacred area, attested only by votive materials in the centre of the plateau, and a wall [62] built in opus quadratum of tuff blocks which defines a protected space in the form of an oppidum [53,63,64,65]. Between the end of the 2nd century BC and the beginning of the 1st century BC, the Civita consolidated its central role in the Sabato valley, thanks to its strategic position along the main natural routes; this settlement continuity favoured the probable establishment of a colony [66] during the Gracchan period [67,68], as suggested by the gromatic sources and the archaeological evidence, a prelude to the urban development clearly recognisable after the Social War [49].

In the 1st century BC, Abellinum was provided with a new city wall in opus reticulatum that enclosed approximately 25 hectares along a linear development of 2 km [62], the circuit being marked by circular towers distributed along the perimeter and by gates that ensured the connection with the external road network [54,65]. In this phase, Abellinum assumed a fully urban layout, as indicated by residential buildings, a bath complex and regular road axes distributed across the plateau. The construction of the aqueduct coming from Serino [54] dates to the Augustan period; in relation to this, research has identified several elements connected with water management, including a piezometric tower, fistulae, distribution channels and a fountain [69]: the urban layout remained substantially stable until the Imperial age; during the 3rd century AD, restoration works were carried out in the bath complex and in the domus.

Subsequently, in Late Antiquity, the city continued to be affected by restorations and functional reorganisations, particularly in the 4th century AD, perhaps following the earthquake of AD 346; evidence of damage and collapse is visible in the city wall and in some residential complexes, which were occupied only in certain rooms. From this moment and at least until the eruption of Pollena (late 5th–early 6th century AD), a contraction of the urban fabric occurred, with a progressive thinning of the settlement; the city, however, continued to be frequented [53,54], as shown by the voluntary removal of pumice in still-used rooms. Recent excavations document the functional continuity of the decumanus, which maintained its role as the main axis, and the continued use of the buildings facing the street, in which the pumice was removed or covered with new walking surfaces [49]. Additional evidence points to continued habitation, albeit in more modest units, attesting to occupation at least until the 6th century AD, together with the continued use of the eastern necropolis with Christian burials and the construction of the cemetery basilica of Capo la Torre (4th–6th centuries AD) [63].

Research activities focus particularly on the north-eastern sector of the Civita, corresponding to the current archaeological area; this sector is dominated by a series of residential complexes brought to light repeatedly over the last fifty years [49] (National Geoportal for Archaeology, GNA—https://data.d4science.net/GKAi, accessed on 9 December 2025), arranged across three different rectangular blocks separated by cardines and facing an E–W axis probably to be identified with the city’s decumanus maximus. Within this sector, notable for its size is the large Late Republican and Imperial domus known as that of M. Vipsanius Primigenius [54,70], identified thanks to the discovery of a bronze seal found along the western edge of the natatio [53], flanked by two additional residential complexes identified from 2021 onwards [49,60,71]. These complexes, although only partially excavated, provide essential morphological constraints for interpreting the GPR-detected architectural continuities. A series of structures facing south onto the decumanus indicates the presence of further blocks towards the south (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

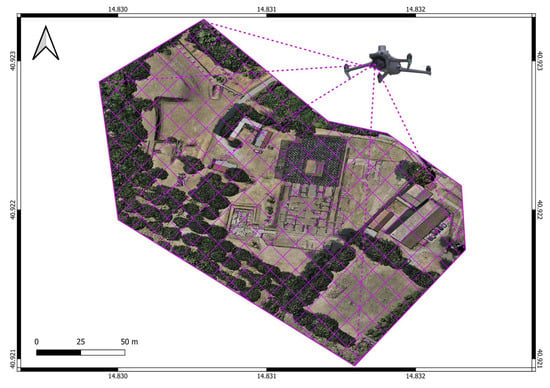

UAV photogrammetric survey layout showing the double-grid flight pattern used for image acquisition and the spatial coverage of the study area.

Within the archaeological area, west of the sector just described, the so-called baths sector [54] is also visible, characterised by complex substructures built to consolidate the slope of the depression, upon which, in the Late Republican period, the bath complex was constructed, incorporating earlier evidence. West of this zone, structural remains survive, such as a cryptoporticus and a cardo, known thanks to excavations carried out in the 1960s and 1970s but no longer visible today [70]; the so-called Guanci quarry is also present here, which damaged this part of the city and from which come finds attributable to important public buildings [72].

Recent identification of two consecutive street intersections, integrated with data from earlier excavations, through which the cardo east of the large domus and another axis located at the western extremity of the Civita were known [54], has made it possible to propose a reconstruction hypothesis of the urban layout as blocks organised according to rectangular modules measuring 35.52 m × 106.56 m, with some insulae, such as those in the north-eastern sector, reduced in length due to the morphological conditions of the plateau [49].

2. Materials and Methods

Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) and photogrammetric data were acquired and processed to reconstruct the three-dimensional geometry, spatial continuity, and architectural organisation of buried archaeological features and to integrate subsurface datasets with high-resolution surface models within a unified geodetic and cartographic reference framework. This integrated approach enabled the direct comparison between surface morphologies and subsurface geophysical anomalies, improving the reliability of archaeological and stratigraphical interpretation.

2.1. Photogrammetric Survey and Surface Modelling

Photogrammetric data were acquired with a DJI Mavic 3 Enterprise (Mavic 3E, https://www.dji.com) UAV equipped with an integrated RGB camera. Flight planning and acquisition were performed using UgCS Enterprise v.5.13 software, adopting an automated double-grid (cross-line) flight pattern to improve image network geometry, increase intersection angles between rays, and reduce directional bias in surface reconstruction (Figure 2).

Image acquisition was carried out with 80% forward overlap and 70% side overlap, ensuring high image redundancy, robust bundle adjustment stability, and a homogeneous spatial distribution of tie points across the entire survey area. Image georeferencing was performed exclusively using RTK-GNSS corrections in order to evaluate the intrinsic accuracy of direct georeferencing approaches in archaeological prospection contexts. Real-time kinematic positioning was provided by the INGV RING network, using the MTMR station (Montemarano, Avellino, Italy) as reference, ensuring centimetric horizontal and vertical positioning accuracy of the acquired imagery [73,74,75,76]. The UAV survey was conducted at a flight altitude of 50 m above ground level (AGL) with a flight speed of 4 m/s; the camera had a 24 mm equivalent focal length, resulting in a ground sampling distance (GSD) of approximately 1.5 cm/pixel.

Photogrammetric processing was performed in Agisoft Metashape Professional v.2.1.4, following a standard Structure-from-Motion (SfM) and Multi-View Stereo (MVS) workflow, including automatic feature extraction, image matching, sparse point cloud generation, bundle block adjustment, dense point cloud reconstruction, polygonal mesh generation, and texture mapping. The final products consisted of a high-resolution orthomosaic and a Digital Surface Model (DSM) (Figure 3), which were then used as the primary spatial reference for georeferencing and integrating GPR profiles, radargrams, and three-dimensional depth/time slices. The final 3D model was georeferenced entirely using RTK-based direct georeferencing, without ground control points. This approach, validated by [73,74] for low-slope, small-area archaeological surveys, ensures centimetric horizontal and vertical accuracy throughout the study area.

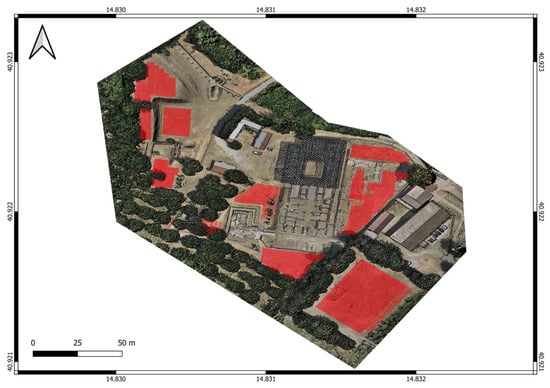

Figure 3.

High-resolution orthomosaic and Digital Surface Model (DSM) of the study area derived from UAV-based Structure-from-Motion photogrammetry.

2.2. GPR Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

The GPR survey was performed using a Radarteam COBRA Plug-in system (https://www.radarteam.se) equipped with a monostatic antenna with a central frequency of 80 MHz and an effective bandwidth of approximately 20–140 MHz. This configuration provided an optimal balance between penetration depth and vertical resolution, allowing the investigation of subsurface targets to depths suitable for archaeological detection under the local geological and soil conditions.

The 80 MHz central frequency was selected as an optimal compromise between penetration and resolution, given the expected depth of architectural remains (1–5 m) and the dielectric variability of the volcaniclastic–alluvial sediments. GPR data were acquired with a time window of 1000 ns, 512 samples per scan, a transmit rate of 160 kHz, and a scan density of 1024 scans/m, ensuring sufficient vertical and lateral resolution to detect buried architectural features down to ~5 m depth in the heterogeneous volcaniclastic–alluvial deposits typical of the site. Based on the estimated electromagnetic wave velocity of 0.10 m/ns in the volcaniclastic and alluvial deposits, the vertical resolution (≈λ/4) of the 80 MHz antenna is approximately 0.23 m. The horizontal resolution, approximated by the first Fresnel zone is ~0.28 m at 1 m depth and increases with depth. These values provide a quantitative basis for evaluating the detectability of buried structures and for defining appropriate survey line spacing.

Data were acquired following a regular, orthogonal grid geometry (Figure 4). GPR profiles were collected with a constant line spacing of 0.50 m in a crossed-grid configuration, with survey lines oriented along two perpendicular directions to enhance structural detectability, improve the azimuthal response of linear features, and minimise directional bias associated with preferential target orientation. A total of 150 profiles were acquired, providing dense spatial sampling, high lateral continuity of reflections, and sufficient redundancy for three-dimensional data reconstruction. The chosen 0.50 m line spacing is consistent with the lateral resolution of the 80 MHz antenna, as estimated from the first Fresnel zone. For a propagation velocity of ~0.10 m/ns, the wavelength at 80 MHz is ~1.25 m, yielding a first Fresnel zone radius of 0.8–1.8 m at the depths of interest. This ensures adequate sampling while avoiding unnecessary oversampling. This density is appropriate for low-frequency systems, where broader wavelength and footprint require tighter line spacing to preserve adequate lateral sampling.

Figure 4.

GPR survey grid and layout of radar transects (red lines), showing the orthogonal acquisition geometry and 0.50 m line spacing.

The antenna was manually towed at a constant speed along predefined survey lines. Positioning was performed using a high-precision GNSS system operating in RTK mode, ensuring centimetric horizontal accuracy. Corrections were provided by the INGV RING network using the MTMR station (Montemarano, Avellino, Italy) as reference. A vertical offset of 0.50 m was applied to account for the physical distance between the GNSS antenna phase centre and the GPR antenna. A topographic correction based on GNSS-derived elevation data was applied to reposition radar traces according to the true ground surface, thereby reducing geometric distortions caused by microtopographic variations [77,78].

2.3. GPR Data Processing

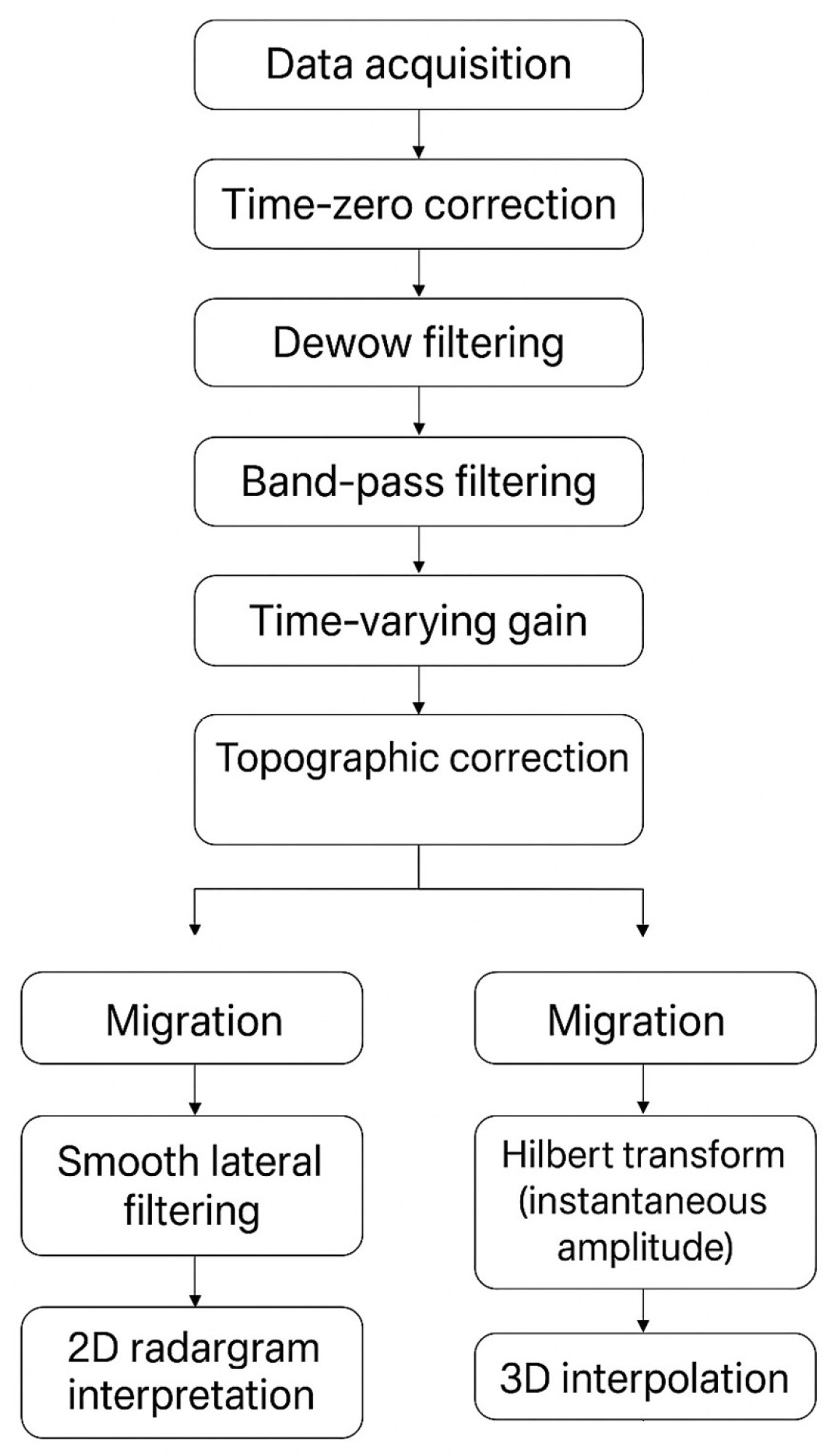

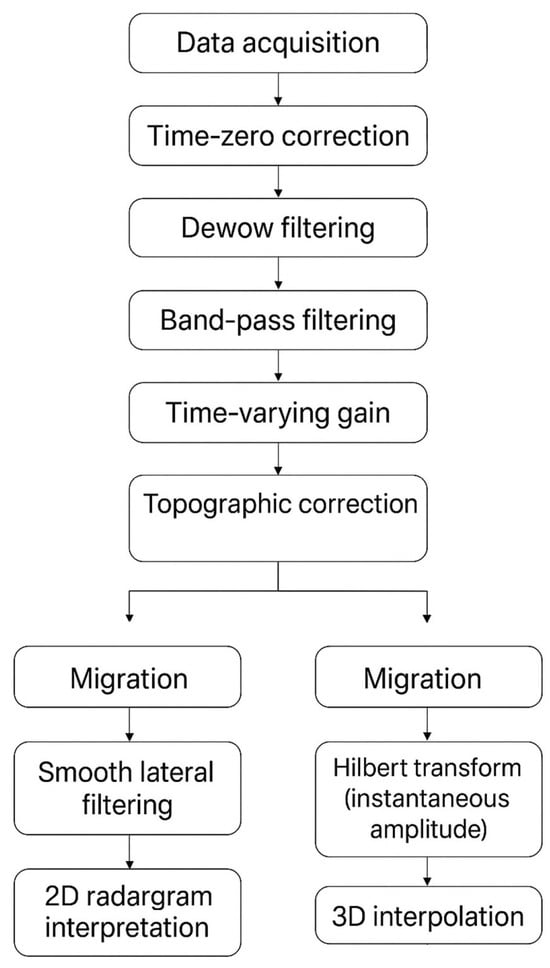

GPR data were processed using a standardised workflow aimed at enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio while preserving the original geometric characteristics of subsurface reflectors (Figure 5). Particular attention was paid to avoiding over-processing that could introduce artificial reflector geometries or distort true travel-time relationships.

Figure 5.

GPR data processing workflow illustrating the main steps applied to the raw radar data, including trace resampling, time-zero correction, filtering, background removal, gain control, migration, Hilbert transform, and preparation of time/depth slices.

Data were processed and analysed using the software platforms Prism-2 (https://www.radsys.lv) and Geolitix (https://www.geolitix.com).

The processing sequence included trace resampling to enforce equidistant spacing, followed by the application of a constant vertical scale to ensure consistent time–depth visualisation across all radargrams. A time-zero correction was applied to remove system-induced delays and correctly align the first arrivals with the ground surface [79,80].

Signal enhancement was achieved through the application of a 2D frequency filter and a frequency-domain band-pass filter, aimed at isolating the effective antenna bandwidth and suppressing incoherent and environmental noise [81,82]. Background subtraction was performed to remove horizontally coherent noise related to system ringing and ambient electromagnetic interference [83,84,85]. Finally, manual gain control was applied to compensate for depth-dependent signal attenuation and to improve the visibility of deeper reflectors, while preserving true relative amplitude variations where possible. Additionally, care was taken to avoid automatic gain equalisation, which could mask true amplitude variations relevant for distinguishing masonry from natural stratigraphic interfaces.

Migration and Hilbert transform were selectively applied only for the generation of time/depth slices, in order to improve reflector focusing and to enhance the amplitude envelope required for volumetric visualisation [86,87,88]. These processes were not applied to the 2D radargrams used for stratigraphic interpretation, thus preserving the original travel-time geometry and lateral continuity of reflections.

2.4. Time and Depth Slice Generation

Three-dimensional subsurface imaging was achieved through the generation of time and depth slices from interpolated GPR amplitude volumes. The workflow included trace positioning correction, regular gridding, and volumetric interpolation using a regularised spatial algorithm, designed to minimise artefacts caused by irregular acquisition geometry and variable trace density [9,37,89,90].

Time windows were defined according to the dominant wavelength and local velocity model, and were converted into depth slices using an electromagnetic wave velocity estimated from hyperbola fitting. For slice generation, migrated data and Hilbert-transformed traces were used to enhance reflector continuity and emphasise reflection amplitudes.

The resulting horizontal slices enabled plan-view visualisation of buried archaeological and stratigraphic features and were subsequently compared with surface models derived from photogrammetric surveys, allowing the assessment of spatial correspondence between surface expressions and subsurface anomalies and supporting the archaeological interpretation of detected structures. The adopted slice thickness ensured a balance between vertical resolution and noise suppression, allowing the recognition of subtle lateral continuities typical of anthropogenic structures.

3. Results

The interpretation of the GPR dataset is based on the systematic analysis of all acquired radargrams, from which subsurface anomalies were first identified and classified. Time/depth slices were subsequently generated to synthesise the information from hundreds of individual profiles into a coherent 3D and planimetric representation, allowing direct comparison with photogrammetric surface models.

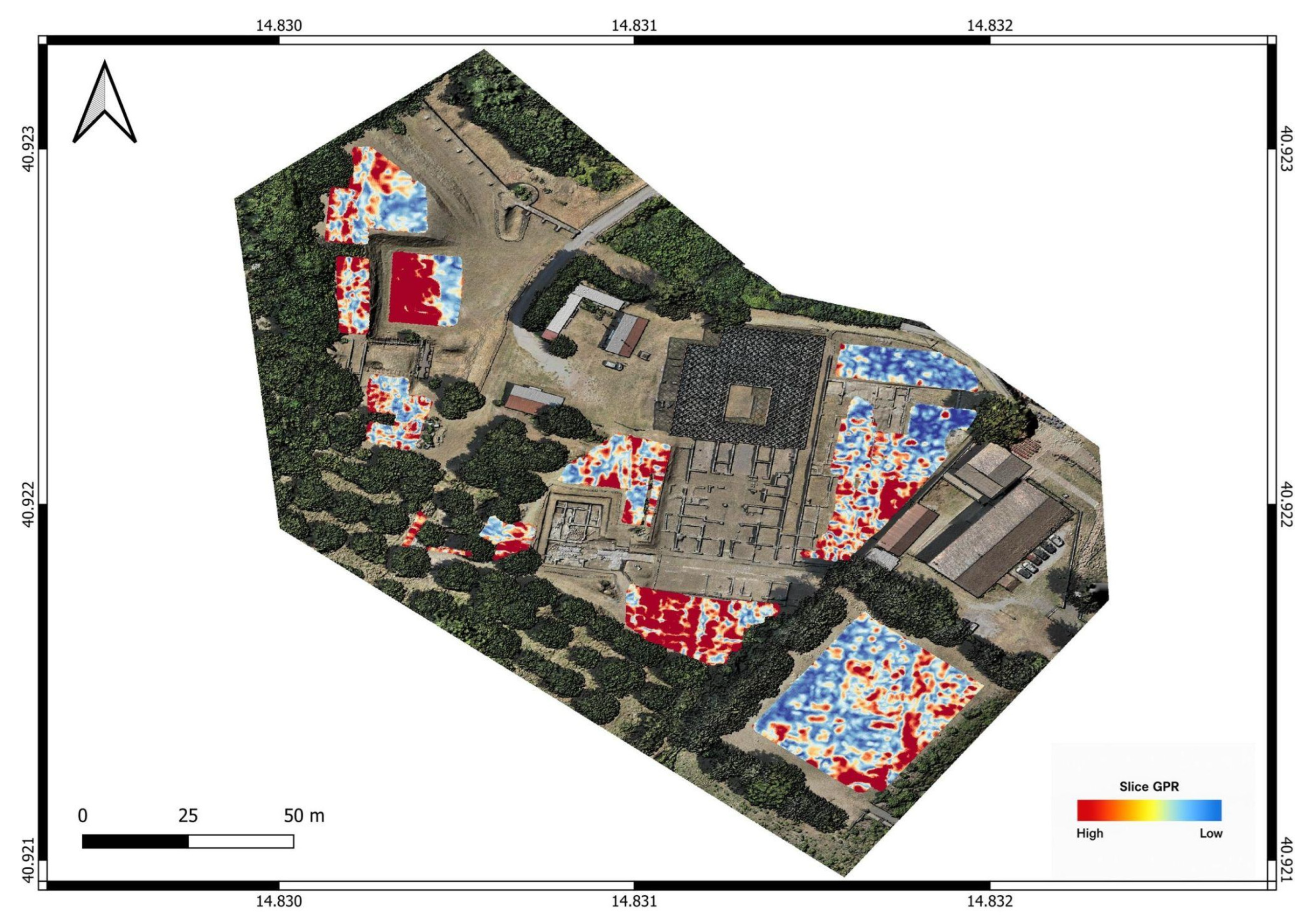

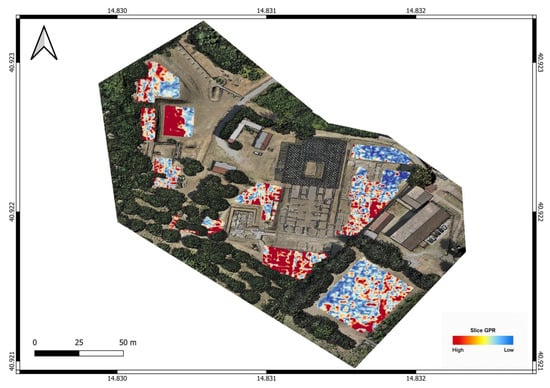

The integrated interpretation of low-frequency GPR data and photogrammetric products provides a coherent view of the spatial organisation of surface and subsurface geological and archaeological features. Figure 6 shows the high-resolution orthomosaic draped over the hillshade-enhanced Digital Surface Model (DSM) combined with the cumulative GPR amplitude depth slices covering the interval between 0 and 4.5 m below ground level.

Figure 6.

High-resolution orthomosaic draped over a hillshade-enhanced DSM, integrated with the cumulative low-frequency GPR amplitude depth slices covering 0–4.5 m. High-amplitude reflections (bright tones) indicate potential buried structures.

The cumulative slice volume highlights a complex distribution of electromagnetic anomalies characterised by variable amplitude, lateral continuity, and internal texture. Several areas are marked by coherent, high-amplitude responses forming elongated and sub-linear patterns. These anomalies are spatially persistent across multiple depth intervals, indicating stable subsurface impedance contrasts rather than isolated or noise-related effects. The spatial persistence and geometric regularity of these anomalies indicate stable subsurface impedance contrasts with characteristics compatible with large-scale buried structures.

Individual depth slices were also analysed to exploit the full 3D resolution of the dataset. Shallow slices (0–1.5 m) reveal laterally continuous, high-amplitude reflections consistent with wall foundations and structured habitation units. Intermediate slices (1.5–3 m) display more heterogeneous reflections, including truncated events and diffraction hyperbolas, interpreted as collapsed or reworked architectural elements and anthropogenic fills. Deeper slices (3–4.5 m) highlight the main lithostratigraphic boundary and possible foundational layers, showing lateral continuity and depth-specific variations that are obscured in the cumulative amplitude blocks. This stratigraphic differentiation supports the identification of multi-phase occupation and construction sequences within the Abellinum site.

The strongest reflections are concentrated in discrete zones, while surrounding areas are dominated by diffuse, low-amplitude responses attributed to more homogeneous fine-grained sediments. The anomalies exhibit a well-defined geometric organisation at the site scale, with recurrent alignments and sharp lateral transitions indicative of structured anthropogenic deposits. Archaeologically, these patterns may reflect building phases, internal spatial divisions, or the presence of collapsed architectural elements within an anthropogenic sedimentary unit. Many of the linear anomalies exhibit orientations consistent with the standing structures, reinforcing their interpretation as continuations of the architectural layout preserved at the surface.

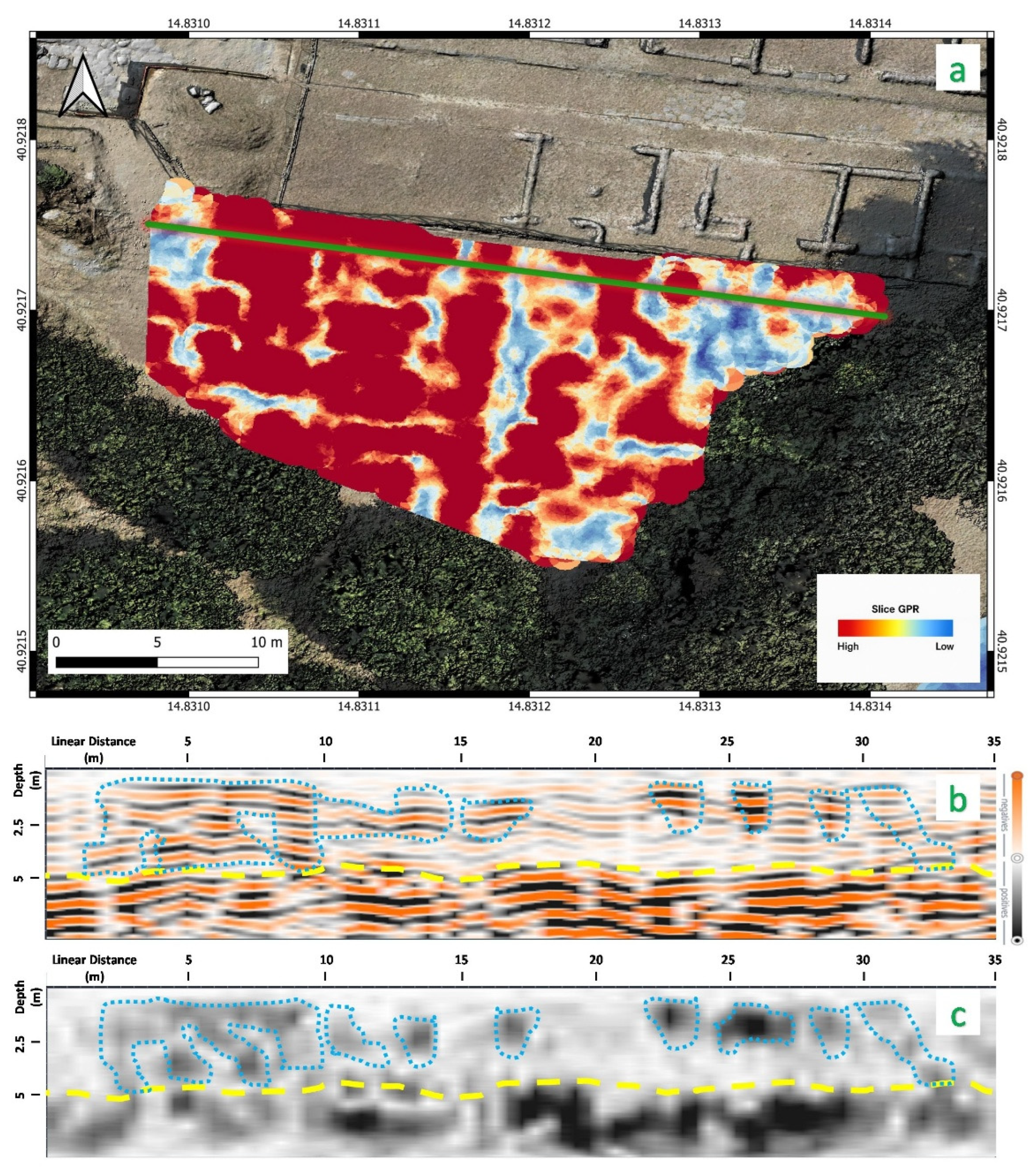

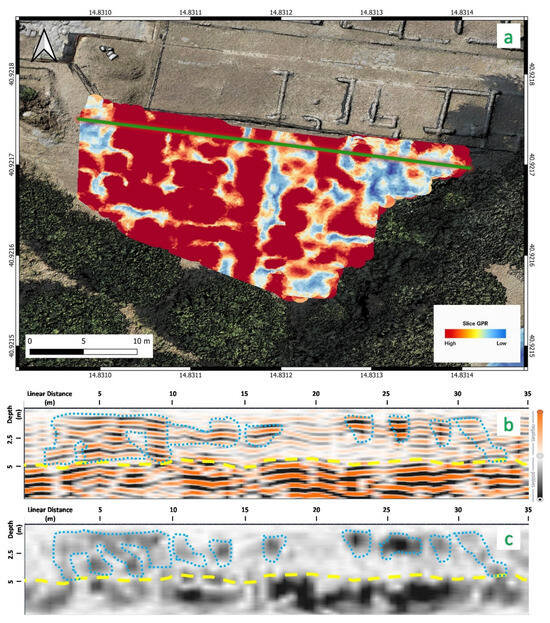

To better illustrate the vertical organisation of the subsurface reflections, Figure 7 shows representative radargrams providing a detailed vertical image of the subsurface reflection architecture. In Figure 7a, the green line indicates the exact GPR transect used for the extraction of the radar section illustrated in Figure 7b,c.

Figure 7.

Representative GPR radargrams showing the vertical reflection architecture of the subsurface. In panel (a), the transect position (green line) is indicated, while panels (b,c) show the conventionally processed radargram and the slice-optimised radargram, respectively. The yellow dashed line marks a reflector at ~5 m depth, while the blue dashed lines indicate shallower linear anomalies.

Only a single representative radargram is shown to illustrate how anomalies identified in the slices manifest in the vertical dimension. The interpretation is based on the full set of radargrams, which were condensed into the time/depth slices to provide a coherent planimetric and volumetric view of subsurface features.

Accordingly, the conclusions drawn in this study rely on the spatial coherence and persistence of anomalies observed across multiple consecutive depth slices, rather than on the interpretation of individual radar profiles.

In Figure 7b, the shallow portion of the radargram, covering the first metres below the surface, shows laterally continuous, high-amplitude reflectors. In addition to interfaces between stratigraphically distinct layers, some of these anomalies exhibit geometries and alignments consistent with walls and architectural units. These reflectors connect coherently with the broader pattern of subsurface anomalies observed across the site, indicating a spatial continuity between shallow architectural remains and deeper, more complex structural elements. Such coherence strongly suggests the presence of buried domestic or functional units aligned with the main building layouts detected in the cumulative depth slices.

At intermediate depths, the reflection pattern becomes more heterogeneous. Discontinuous reflectors, truncated events, and frequent diffraction hyperbolas indicate localised point reflectors or sharp lateral impedance contrasts. These features likely correspond to collapsed structural elements, debris layers, or complex sequences of anthropogenic fill, reflecting multi-phase construction, use, and abandonment.

These features are interpreted as possible reworked or collapsed architectural elements, based on reflection character, amplitude variability, and reduced continuity observed in both radargrams and depth slices.

Beneath these levels, the radargrams consistently reveal a laterally continuous, high-amplitude reflector at ~5 m depth, interpreted as the main lithostratigraphic discontinuity. Its marked signature can be related to a strong change in mechanical properties at the transition of the above-described filling layers and the Pomici di Avellino volcaniclastic deposits, locally used as founding substratum of Abellinum buildings and structures.

It should be noted that depth estimations are subject to uncertainties associated with the assumed electromagnetic wave velocity. Hyperbola fitting performed across multiple profiles yielded a consistent average velocity range of approximately 0.09–0.11 m/ns, which is coherent with the dielectric properties expected for the volcaniclastic and alluvial deposits in the area. Local dielectric variations related to moisture content, compaction, or lithological heterogeneity may nonetheless introduce a range error of approximately ±10–15%, without affecting the geometric consistency of the detected anomalies.

Figure 7c shows the slice-optimised radargram, processed for time/depth slice generation using migration and Hilbert transform, enhances reflector focusing and lateral localization of diffractive features. Shallow anomalies interpreted as walls and habitation units remain clearly defined, providing volumetric support for plan-view reconstruction and their stratigraphic relationships.

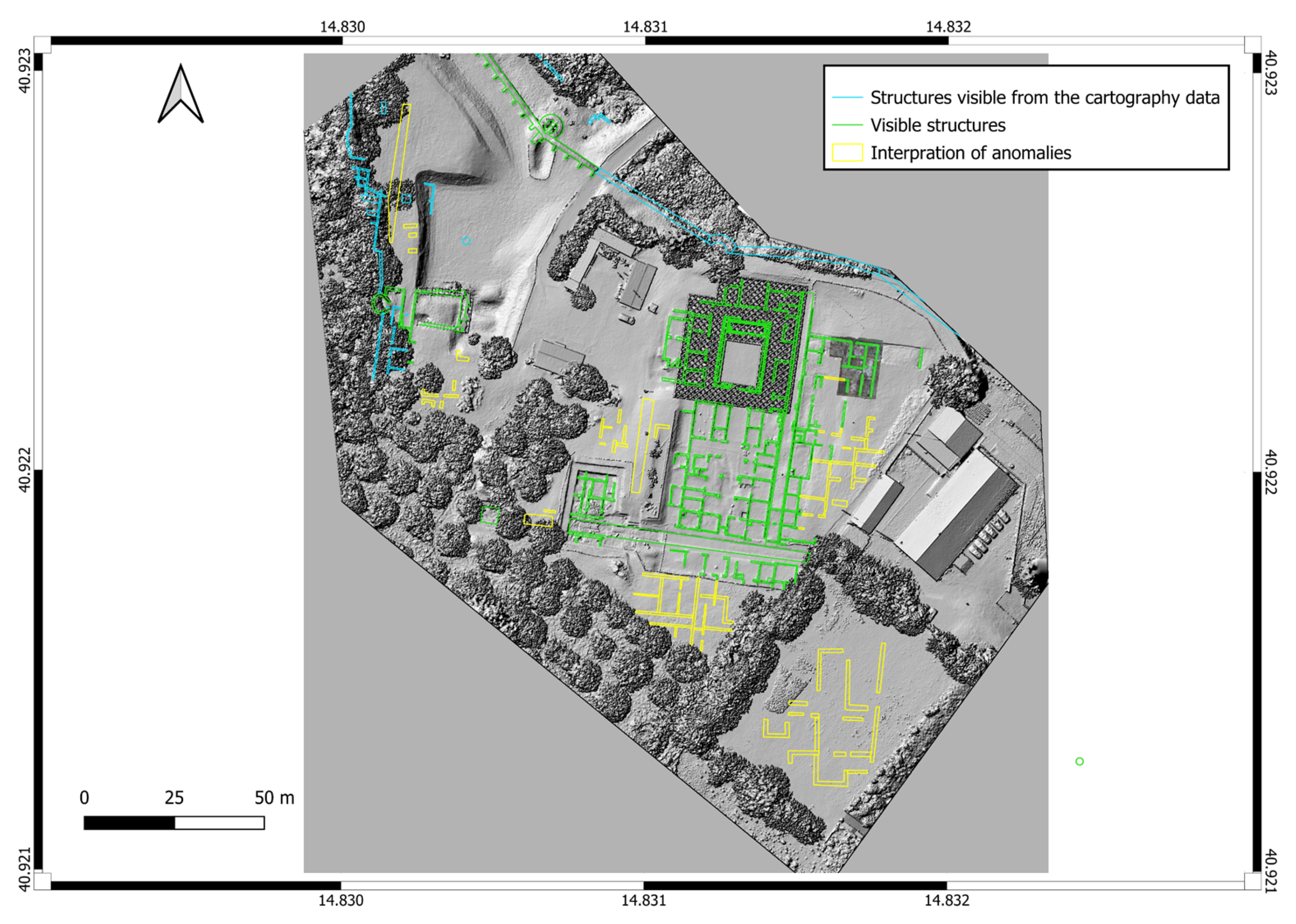

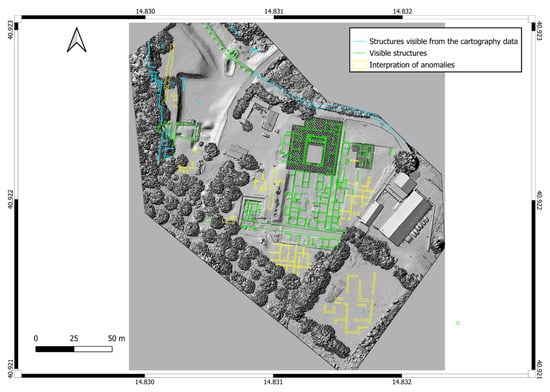

Figure 8 shows the integrated vector model combining photogrammetric and GPR-derived features. The outlines of visible structures, extracted from the orthomosaic and DSM, are combined with planimetric geometries of subsurface anomalies. This vector-based output enables seamless integration into GIS and BIM/HBIM platforms.

Figure 8.

Integrated vector reconstruction combining visible architectural remains extracted from photogrammetric products and buried features interpreted from GPR time/depth slices, showing the spatial continuity between exposed and subsurface structures.

The inferred continuity between exposed and buried structures is supported by the repeated occurrence of aligned reflections in multiple adjacent radargrams, subsequently confirmed by their persistence and geometric coherence across consecutive depth slices.

The combined dataset shows a clear spatial correspondence between the extant architectural remains and the geometrical patterns detected in the subsurface. The vectorized GPR-derived features show systematic alignments, orthogonal intersections, and spatial organisation consistent with the visible structural framework, suggesting that the buried anomalies represent the continuation and extension of the exposed architectural layout.

The superposition of surface-derived and subsurface-derived vector layers allows the identification of previously unrecognised architectural units, possible expansions of known buildings, and the continuity of structural axes beyond the currently visible remains. This approach provides a synthetic and scalable representation of the archaeological layout, transforming geophysical evidence into interpretable architectural hypotheses.

4. Discussion

These observations provide the basis for interpreting the detected anomalies within a broader archaeological and stratigraphic framework.

The geometry and spatial organisation of the detected subsurface anomalies are consistent with typical Roman urban architectural elements, such as wall foundations and associated structural spaces. Linear and rectilinear features are interpreted as probable wall-like structures, while broader and less coherent anomalies may reflect reworked or collapsed architectural remains.

The cumulative GPR amplitude slices and radargrams show consistent spatial persistence, organised geometries, and multi-depth coherence, confirming that the anomalies correspond to structured anthropogenic deposits rather than natural heterogeneities.

The radargrams differentiate three main depth domains. In the shallow levels, laterally continuous high-amplitude reflections define coherent architectural elements, including wall segments and construction interfaces. Intermediate-depth anomalies are interpreted cautiously as possible reworked or collapsed architectural elements, based on their reflection characteristics, amplitude variability, and limited lateral continuity in the depth slices.

Beneath these levels, the radargrams consistently reveal a laterally continuous, high-amplitude reflector at ~5 m depth. This boundary reflects the main lithostratigraphical discontinuity between the undisturbed Pomici di Avellino volcaniclastic deposits and the shallow loose sediments (colluvial, buried soils, volcaniclastic and anthropogenic deposits) of late Holocene age. In several outcrops of the Archaeological Park, the pedo-sedimentary succession at the top of the TGC deposits reaches ca. 4–5 m. Its strong and pervasive signature, visible across all radar transects, motivated the choice to limit the depth-slice visualisation to the 0–4.5 m interval. This methodological choice prevents amplitude saturation in the lower slices and preserves the interpretability of shallower archaeological features, ensuring that the most pronounced linear anomalies (interpreted as possible wall alignments) are clearly resolved within the upper interval.

The comparison between standard-processed radargrams and slice-optimised sections demonstrates the value of advanced processing workflows. Migration and Hilbert-based processing improve reflector localization for shallow features while preserving the volumetric context of deeper deposits, providing robust support for interpreting multi-phase construction sequences.

Building upon the geometric consistency observed across depth levels, the vector-based integration of photogrammetric and GPR-derived data enables a clear comparison between surface and subsurface architectural patterns. This integration confirms the alignment of shallow and deep anomalies with known urban grids and structured settlement layouts.

From an archaeological perspective, the spatial organisation of the detected subsurface anomalies is consistent with planned Roman urban layouts, where buildings and infrastructural elements follow preferential orientations and orthogonal arrangements. The persistence of linear anomalies aligned with exposed structures suggests the presence of organised architectural blocks rather than isolated constructions.

The integration of GPR-derived geometries with surface photogrammetry allows the identification of potential continuations of known structures, internal divisions within building complexes, and coherent structural axes extending beyond the currently visible remains. These patterns are compatible with multi-phase urban development; however, due to the non-invasive nature of the survey, these interpretations remain hypothetical and should be considered cautiously.

While specific functional attributions are intentionally avoided, the detected geometries provide a robust framework for hypothesising urban organisation and spatial hierarchies, demonstrating the archaeological value of the integrated geophysical–geomatic approach.

The strong geometric coherence observed between visible walls and subsurface linear anomalies supports the hypothesis that the buried features represent the continuation of architectural systems currently only partially preserved. When combined with plan-view anomalies, this coherence confirms planned architectural layouts rather than casual depositional or geological processes.

The method also enables the identification of architectural discontinuities, areas of structural collapse, and possible zones of rebuilding or functional reorganisation. In this sense, the vector reconstruction acts as a bridge between geophysical prospection and archaeological interpretation, allowing testable hypotheses on building phases, spatial hierarchies, and site organisation without invasive excavation.

Furthermore, the production of a unified vector model represents an important methodological step toward georeferenced archaeological information systems, facilitating predictive and management-oriented frameworks for the conservation and monitoring of buried heritage.

In summary, the integrated results provide a coherent archaeological and stratigraphic interpretation, where shallow and deep anomalies, structural coherence, and plan-view geometries combine to outline a structured settlement layout with identifiable functional areas, internal divisions, and multi-phase construction dynamics.

Specific functional attributions (e.g., domus, bath complexes, or other building types) are intentionally avoided, as such interpretations would require stratigraphic excavation for validation. The proposed interpretations are therefore limited to morphological and spatial categories, in line with the non-invasive nature of the investigation.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an integrated application of low-frequency GPR and UAV-based photogrammetry for a non-invasive investigation of complex archaeological contexts, with particular emphasis on deep subsurface imaging and surface–subsurface data integration.

The combined analysis highlights the capability of low-frequency GPR to detect laterally persistent subsurface anomalies down to several metres depth in volcaniclastic and anthropogenically modified environments, where conventional high-frequency GPR systems are often limited. When integrated with high-resolution photogrammetric surface models, these datasets allow for a coherent volumetric visualisation of exposed and buried features within a unified spatial framework.

The detected subsurface anomalies display recurring linear geometries, spatial persistence across multiple depth slices, and geometric relationships with visible architectural remains. These characteristics are compatible with the presence of organised anthropogenic structures, such as wall foundations and associated construction levels. However, given the non-invasive nature of the investigation and the intrinsic limitations of low-frequency GPR resolution, such interpretations should be regarded as morphological and spatial reliable hypotheses rather than definitive archaeological identifications.

In detail, the observed alignments between subsurface anomalies and surface structures are interpreted as suggestive of architectural continuity, but they cannot be considered conclusively demonstrated without stratigraphic excavation or independent validation. The results therefore emphasise geometric coherence and spatial consistency, rather than functional attribution or urban reconstruction. Regarding the geological setting, the high-amplitude reflector at ~5 m depth can be confidentially associated with the main lithostratigraphical discontinuity hosted in the stratigraphycal record of the study area: the boundary between the undisturbed Pomici di Avellino volcaniclastic deposits and the shallow loose and reworked sediments of late Holocene age.

Beyond site-specific interpretations, the main contribution of this work lies in the proposed methodological workflow. The integration of deep GPR imaging with precise geomatic documentation reduces interpretative ambiguity, supports hypothesis-driven archaeological reasoning, and provides a transferable framework for investigating buried cultural heritage in complex geological settings.

Future investigations should aim to validate these hypotheses through targeted excavation, complementary geophysical techniques, or multi-frequency GPR surveys. In this perspective, the approach presented here represents a robust preparatory tool for guiding archaeological research and heritage management (e.g., a reliable estimation of excavation volumes, predicting target depths accurately), rather than a substitute for direct archaeological verification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.F.; methodology, N.A.F.; software, N.A.F.; validation, All; investigation, All; data curation, N.A.F. and A.A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, All; writing—review and editing, All; visualisation, N.A.F., A.A.V. and G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the Direzione Regionale Musei Nazionali della Campania (DRMC), in particular previous and actual Director, Luana Toniolo and Luigina Tomay and the Municipality of Atripalda for granting access and research authorizations (MIC_DG-ABAP_SERV II|27/05/2025|0018208-PDG-ABAP|26/05/2025|DECRETO 812) and for their institutional support throughout the activities. Special thanks are extended to the staff of the Archaeological Park of Abellinum for their logistical assistance, collaboration, and valuable support during the fieldwork and survey phases. Their availability and professionalism were fundamental to the successful completion of this study. Gratitude is also expressed to the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the provinces of Salerno and Avellino for their valuable collaboration. We thank Laura De Girolamo, Antonio Chiumento and Valentina Caroccia for their valuable contributions, offered through their archival research, field investigations and reconstructions concerning the urban landscape of Abellinum.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vickers, R.; Bollen, R.; Johnson, D.; Tanzi, J.; Bevan, B. Ground-Penetrating Radar at Chaco Canyon, USA, 1974–1976; Stanford Research Institute: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Conyers, L.B. Ground-Penetrating Radar: An Introduction for Archaeologists; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, B.W. Geophysical Exploration for Archaeology: An Introduction to Geophysical Exploration; Midwest Archeological Center: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1998.

- Daniels, D.J. Ground Penetrating Radar; IET: Stevenage, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Verdonck, L. Ground-Penetrating Radar for Archaeology (3rd Edn) Lawrence B. Conyers, Series Editors: Lawrence, B. Conyers and Kenneth, L. Kvamme, Geophysical Methods for Archaeology No. 4, AltaMira Press, Lanham, MD, 2013, Xv + 241 Pp., £22.95, ISBN 978-0-7591-2349-6 (Paperback). Archaeol. Prospect. 2016, 23, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, D. Ground-Penetrating Radar Simulation in Engineering and Archaeology. Geophysics 1994, 59, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strapazzon, G. Nuove Tecnologie a Supporto della Ricerca Archeologica: Applicazioni e Sviluppi Possibili su Sistemi Complessi. Ph.D. Thesis, Università di Padova, Padua, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Conyers, L.B. Discovery, Mapping and Interpretation of Buried Cultural Resources Non-Invasively with Ground-Penetrating Radar. J. Geophys. Eng. 2011, 8, S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, D.; Piro, S. GPR Image Construction and Image Processing. In GPR Remote Sensing in Archaeology; Goodman, D., Piro, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 63–100. [Google Scholar]

- Piro, S.; Campana, S. GPR Investigation in Different Archaeological Sites in Tuscany (Italy). Analysis and Comparison of the Obtained Results. Near Surf. Geophys. 2012, 10, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manataki, M.; Vafidis, A.; Sarris, A. GPR Data Interpretation Approaches in Archaeological Prospection. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.L.; Kind, T.; Wiggenhauser, H. Frequency-Dependent Dispersion of High-Frequency Ground Penetrating Radar Wave in Concrete. NDT E Int. 2011, 44, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.A.; Heinson, G.; Munday, T.; Thiel, S.; Lawrie, K.; Clarke, J.D.A.; Mill, P. The Importance of Including Conductivity and Dielectric Permittivity Information When Processing Low-Frequency GPR and High-Frequency EMI Data Sets. J. Appl. Geophys. 2013, 96, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.W.L.; Chang, R.K.W.; Sham, J.F.C.; Pang, K. Perturbation Mapping of Water Leak in Buried Water Pipes via Laboratory Validation Experiments with High-Frequency Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR). Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 52, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, S.; Grote, K.; Rubin, Y. Mapping the Volumetric Soil Water Content of a California Vineyard Using High-Frequency GPR Ground Wave Data. Lead. Edge 2002, 21, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukyanov, S.P.; Stukach, O.V. Archeological Researches of the Ancient Fortress by GPR. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Siberian Conference on Control and Communications, Tomsk, Russia, 27–28 March 2009; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ribolini, A.; Bini, M.; Isola, I.; Coschino, F.; Baroni, C.; Salvatore, M.C.; Zanchetta, G.; Fornaciari, A. GPR versus Geoarchaeological Findings in a Complex Archaeological Site (Badia Pozzeveri, Italy). Archaeol. Prospect. 2017, 24, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, V.; Carrozzo, M.T.; Negri, S.; Nuzzo, L.; Quarta, T.; Villani, A.V. A Ground-Penetrating Radar Survey for Archaeological Investigations in an Urban Area (Lecce, Italy). J. Appl. Geophys. 2000, 44, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucci, G.; Negri, S. Use of Ground Penetrating Radar to Map Subsurface Archaeological Features in an Urban Area. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2006, 33, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, R.; Garcia, E.; Tamba, R.; Sala, R.; Garcia, E.; Tamba, R. Archaeological Geophysics—From Basics to New Perspectives. In Archaeology, New Approaches in Theory and Techniques; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Irving, J.; Holliger, K. High-Resolution Velocity Estimation from Surface-Based Common-Offset GPR Reflection Data. Geophys. J. Int. 2022, 230, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, N.; Persico, R.; Rizzo, E. Some Examples of GPR Prospecting for Monitoring of the Monumental Heritage. J. Geophys. Eng. 2010, 7, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, P.M.; Ferrara, C. The Past Beneath the Present: Gpr as a Scientific Investigation for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Preservation. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 8, 581. [Google Scholar]

- Malagodi, S.; Orlando, L.; Piro, S.; Rosso, F. Location of Archaeological Structures Using GPR Method: Three-Dimensional Data Acquisition and Radar Signal Processing. Archaeol. Prospect. 1996, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Nieto, X.; Solla, M.; Novo, A.; Lorenzo, H. Three-Dimensional Ground-Penetrating Radar Methodologies for the Characterization and Volumetric Reconstruction of Underground Tunneling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 71, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzo, L.; Leucci, G.; Negri, S.; Carrozzo, M.; Quarta, T. Application of 3D Visualization Techniques in the Analysis of GPR Data for Archaeology. Ann. Geophys. 2002, 45, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasmueck, M.; Weger, R.; Horstmeyer, H. Full-Resolution 3D GPR Imaging. In Seismic Diffraction; Klem-Musatov, K., Hoeber, H., Pelissier, M., Moser, T.J., Eds.; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Houston, TX, USA, 2016; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Gravey, M.; Mariéthoz, G.; Irving, J. Reconstruction of High-Resolution 3D GPR Data from 2D Profiles: A Multiple-Point Statistical Approach. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornik, A.; Neubauer, W. 3D Visualization Techniques for Analysis and Archaeological Interpretation of GPR Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinta-Ferreira, M. Ground Penetration Radar in Geotechnics. Advantages and Limitations. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 221, 012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, J.-Y.; Park, K.-T.; Cho, J.-W.; Lee, S.-Y. A Study of the Application and the Limitations of GPR Investigation on Underground Survey of the Korean Expressways. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, N.J. Electrical and Magnetic Properties of Rocks, Soils and Fluids. In Ground Penetrating Radar Theory and Applications; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Huang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, F.; Sun, J. The Very Low-Frequency Step-Frequency GPR System and Its Application to Active Fault Detection. Near Surf. Geophys. 2008, 6, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, L.; Persico, R.; Geraldi, E.; Sileo, M.; Piro, S. GPR and IRT Tests in Two Historical Buildings in Gravina in Puglia. Geosci. Instrum. Methods Data Syst. 2016, 5, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, F.; Podd, F.; Solla, M. From Its Core to the Niche: Insights from GPR Applications. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, N.A.; Pilato, S.L.; Massa, B.; Memmolo, A.; Migliazza, R.; Osanna, M.; Toniolo, L.; Manco, A.; Vicari, A. Low-Frequency GPR as a Gateway to Archaeological Investigations: The Aeclanum’s Buried Roman-Age Forum (Southern Italy). In Proceedings of the Copernicus Meetings, Vienna, Austria, 27 April–2 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, D.; Nishimura, Y.; Rogers, J.D. GPR Time Slices in Archaeological Prospection. Archaeol. Prospect. 1995, 2, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.C.; Ambekar, A.S. Application of Stepped Frequency GPR Survey in Investigating Potential Archaeological Sites. J. Multidiscip. Stud. Archaeol. 2024, 12, 1357–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Conyers, L.B. Ground-Penetrating Radar for Archaeology; Bloomsbury Publishing PLC: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jol, H.M. Ground Penetrating Radar Theory and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, L. GPR to Constrain ERT Data Inversion in Cavity Searching: Theoretical and Practical Applications in Archeology. J. Appl. Geophys. 2013, 89, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arato, A.; Piro, S.; Sambuelli, L. 3D Inversion of ERT Data on an Archaeological Site Using GPR Reflection and 3D Inverted Magnetic Data as a Priori Information. Near Surf. Geophys. 2015, 13, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucci, G.; Miccoli, I.; Barbolla, D.F.; De Giorgi, L.; Ferrari, I.; Giuri, F.; Scardozzi, G. Integrated GPR and ERT Surveys for the Investigation of the External Sectors of the Castle of Melfi (Potenza, Italy). Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piga, C.; Piroddi, L.; Pompianu, E.; Ranieri, G.; Stocco, S.; Trogu, A. Integrated Geophysical and Aerial Sensing Methods for Archaeology: A Case History in the Punic Site of Villamar (Sardinia, Italy). Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 10986–11012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, D.; Limongiello, M.; Demetrescu, E.; Ferdani, D. Multispectral UAV Data and GPR Survey for Archeological Anomaly Detection Supporting 3D Reconstruction. Sensors 2023, 23, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescatore, T.S.; Pinto, F.; Guadagno, F.; Lupo, G.; Giano, S.; Ornella, A.; Parente, M. Note Illustrative della Carta Geologica d’Italia Alla Scala 1:50.000, Foglio 449 Avellino; Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale: Rome, Italy, 2017.

- Giaccio, B.; Hajdas, I.; Isaia, R.; Deino, A.; Nomade, S. High-Precision 14C and 40Ar/39Ar Dating of the Campanian Ignimbrite (Y-5) Reconciles the Time-Scales of Climatic-Cultural Processes at 40 Ka. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, S.; Germinario, C.; Alberghina, M.F.; Covolan, M.; Mercurio, M.; Musmeci, D.; Piovesan, R.; Santoriello, A.; Schiavone, S.; Grifa, C. Multilayer Technology of Decorated Plasters from the Domus of Marcus Vipsanus Primigenius at Abellinum (Campania Region, Southern Italy): An Analytical Approach. Minerals 2022, 12, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musmeci, D. Abellinum, la vita di una città. Note di sintesi e nuovi dati. Ann. Archeol. Stor. Antica 2023, 29, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mele, D.; Sulpizio, R.; Dellino, P.; La Volpe, L. Stratigraphy and Eruptive Dynamics of a Pulsating Plinian Eruption of Somma-Vesuvius: The Pomici Di Mercato (8900 Years B.P.). Bull. Volcanol. 2011, 73, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vito, M.A.; Aurino, P.; Boenzi, G.; Laforgia, E.; Rucco, I. Human Communities Living in the Central Campania Plain during Eruptions of Vesuvius and Campi Flegrei. Ann. Geophys. 2021, 64, V0546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passariello, I.; Albore Livadie, C.; Talamo, P.; Lubritto, C.; D’Onofrio, A.; Terrasi, F. 14 C Chronology of Avellino Pumices Eruption and Timing of Human Reoccupation of the Devastated Region. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci Pescatori, G. Osservazioni su Abellinum tardo-antica e sull’eruzione del 472 D.C. In Tremblements de Terre, Éruptions Volcaniques et vie des Hommes Dans la Campanie Antique; Albore Livadie, C., Ed.; Collection du Centre Jean Bérard; Publications du Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 1986; pp. 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Colucci Pescatori, G. Evidenze archeologiche in Irpinia. In La Romanisation du Samnium Aux iie et ier s. av. J.-C.: Actes du Colloque International (Naples 1988); Bérard, C.J., Ed.; Collection du Centre Jean Bérard; Publications du Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 1991; pp. 85–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sulpizio, R.; Mele, D.; Dellino, P.; Volpe, L.L. A Complex, Subplinian-Type Eruption from Low-Viscosity, Phonolitic to Tephri-Phonolitic Magma: The AD 472 (Pollena) Eruption of Somma-Vesuvius, Italy. Bull. Volcanol. 2005, 67, 743–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidoboni, E.; Ferrari, G.; Mariotti, D.; Comastri, A.; Tarabusi, G.; Sgattoni, G.; Valensise, G. Historical Earthquake Data from the CFTI5Med Catalogue—Epicenter Details. PANGAEA 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidoboni, E.; Ferrari, G.; Tarabusi, G.; Sgattoni, G.; Comastri, A.; Mariotti, D.; Ciuccarelli, C.; Bianchi, M.G.; Valensise, G. CFTI5Med, the New Release of the Catalogue of Strong Earthquakes in Italy and in the Mediterranean Area. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galadini, F.; Galli, P. The 346 A.D. Earthquake(Central-Southern Italy): An Archaeoseismological Approach. Ann. Geophys. 2004, 47, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soricelli, G. La Provincia del Samnium e Il Terremoto del 346 dC; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Santoriello, A. Abellinum, ricerche e studi sull’antico centro dell’Irpinia. Un quadro di sintesi per nuove prospettive di ricerca. Ann. Archeol. Stor. Antica 2022, 29, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Storia dell’Irpinia antica|Giampiero Galasso|De Angelis. 2006. Available online: https://www.unilibro.it/libro/galasso-giampiero/storia-dell-irpinia-antica/9788886218863 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Musmeci, D. Sui sistemi difensivi in Irpinia (IV-I sec. a.C.). Un quadro di sintesi tra dati archeologici e «architettura rappresentata». Otium. Archeol. Cult. Mondo Antico 2024, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atripalda, F.M. Gli Eubei in Occidente. In Proceedings of the XVIII Convegno di Studi Sulla Magna Grecia, Taranto, Italy, 8–12 October 1978; Istituto per la Storia: Roma, Italy, 1978; pp. 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Johannowsky, W. Note Di Archeologia e Topografia Dell’Irpinia Antica. In L’Irpinia Nella Società Meridionale, ‘Annali Centro Dorso 1985-86’; Centro di ricerca “Guido Dorso”: Avellino, Italy, 1987; pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pescatori, C.C. Storia Illustrata di Avellino e dell’Irpinia; Sellino & Barra: Avellino, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Camodeca, G. Note Sull’Irpinia in Età Romana. In Studi Sull’Irpinia Antica; Tiotinx: Naples, Italy, 2021; pp. 89–130. [Google Scholar]

- Camodeca, G. Istituzioni e Società Di Abellinum Romana. In Storia Illustrata di Avellino e dell’Irpinia, I. L’Irpinia Antica; Pescatori, G.C., Ed.; Sellino & Barra: Pratola Serra, Italy, 1996; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Camodeca, G. Note Sull’Hirpinia in Età Romana. In Appellati Nomine Lupi: Giornata Internazionale di Studi Sull’Hirpinia e Gli Hirpini; Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa: Naples, Italy, 2014; pp. 97–128. [Google Scholar]

- Covolan, M.; Musmeci, D.; Santoriello, A. Abellinum and Its Water Distribution System: New Evidences for a Wider Comprehension of the Hydraulic Infranstructures. Constr. Oper. 2025, 131, 202–215. [Google Scholar]

- Fariello Sarno, M.R. Abellinum Romana II. In Stor Illus di Avellino e dell’Irpinia L’Irpinia Antica; Colucci Pescatori, G., Ed.; Sellino & Barra: Salerno, Italy, 1996; pp. 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Limongiello, M.; Musmeci, D.; Radaelli, L.; Chiumiento, A.; di Filippo, A.; Limongiello, I. Parametric GIS and HBIM for Archaeological Site Management and Historic Reconstruction Through 3D Survey Integration. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo Muscettola, S. Appunti sulla cultura figurativa in area Irpina. In La Romanisation du Samnium Aux iie et ier s. av. J.-C.: Actes du Colloque International (Naples 1988); Bérard, C.J., Ed.; Collection du Centre Jean Bérard; Publications du Centre Jean Bérard: Naples, Italy, 1991; pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti, N.A.; Cecere, G.; Grasso, C.; Memmolo, A.; Vicari, A. A Test on the Potential of a Low Cost Unmanned Aerial Vehicle RTK/PPK Solution for Precision Positioning. Sensors 2021, 21, 3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, N.A.; Miele, P.; Memmolo, A.; Falco, L.; Castagnozzi, A.; Moschillo, R.; Grasso, C.; Migliazza, R.; Selvaggi, G.; Vicari, A. New Concept of Smart UAS-GCP: A Tool for Precise Positioning in Remote-Sensing Applications. Drones 2024, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmolo, A.; Famiglietti, N.A.; Moschillo, R.; Grasso, C.; Vicari, A. UAS-LC-GNSS: Precision Surveying with a Low-Cost GNSS System for Commercial Drones. Rend. Online Soc. Geol. Ital. 2023, 60, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV). Rete Integrata Nazionale GPS (RING) 2016, More Than 250 Continuous GNSS Stations; Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV): Rome, Italy, 2016.

- Famiglietti, N.A.; Memmolo, G.; Memmolo, A.; Migliazza, R.; Gagliarde, N.; Di Bucci, D.; Cheloni, D.; Vicari, A.; Massa, B. Low-Frequency Ground Penetrating Radar for Active Fault Characterization: Insights from the Southern Apennines (Italy). Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, N.A.; Miele, P.; Massa, B.; Memmolo, A.; Moschillo, R.; Zarrilli, L.; Vicari, A. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) Investigations in Urban Areas Affected by Gravity-Driven Deformations. Geosciences 2024, 14, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbeck, L.; Mester, A.; Zimmermann, E.; Klotzsche, A.; van Waasen, S. In Situ Time-Zero Correction for a Ground Penetrating Radar Monitoring System with 3000 Antennas. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 075904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadhoush, H.; Giannopoulos, A. Optimizing GPR Time-zero Adjustment and Two-way Travel Time Wavelet Measurements Using a Realistic Three-dimensional Numerical Model. Near Surf. Geophys. 2022, 20, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, N. Time-varying Band-pass Filtering GPR Data by Self-inverse Filtering. Near Surf. Geophys. 2016, 14, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Assuncao, S.; Wong, T.-W.P.; Lai, W.W.L. Optimising Thresholding of Bandpass Filter through GPR Wavelet Transform in Time-Frequency Domain. In Proceedings of the 2021 11th International Workshop on Advanced Ground Penetrating Radar (IWAGPR), Valletta, Malta, 1–4 December 2021; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, B.; Singh, D.; Gaba, S.P. Critical Analysis of Background Subtraction Techniques on Real GPR Data. Def. Sci. J. 2017, 67, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayordomo, A.M.; Yarovoy, A. Optimal Background Subtraction in GPR for Humanitarian Demining. In Proceedings of the 2008 European Radar Conference, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 30–31 October 2008; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Gaba, S.P.; Singh, D. Study of Background Subtraction for Ground Penetrating Radar. In Proceedings of the 2015 National Conference on Recent Advances in Electronics & Computer Engineering (RAECE), Roorkee, India, 13–15 February 2015; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T.; Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z. Analysis of Direction-Decomposed and Vector-Based Elastic Reverse Time Migration Using the Hilbert Transform. Geophysics 2019, 84, S599–S617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Gao, J.; Gao, Z.; Jiang, X.; Sun, W. A Causal Imaging Condition for Reverse Time Migration Using the Discrete Hilbert Transform and Its Efficient Implementation on GPU. J. Geophys. Eng. 2019, 16, 894–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.E.; Wu, Z. A Review on Hilbert-Huang Transform: Method and Its Applications to Geophysical Studies. Rev. Geophys. 2008, 46, RG2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shayea, Q.; Bahia, I. Ground Penetrating Radar Slice Reconstruction for Embedded Object in Media with Target Follow. WSEAS Trans. Comput. 2010, 9, 496–505. [Google Scholar]

- De Angeli, S.; Serpetti, M.; Battistin, F. A Newly Developed Tool for the Post-Processing of GPR Time-Slices in A GIS Environment. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.