Abstract

The observed shortage of water resources in the western and southern regions of the Russian Federation may soon affect the territory of the Republic of Bashkortostan. An increase in the share of groundwaters can help to solve this problem. To provide the population of the republic with water resources, the groundwater of magnesium–bicarbonate-type from the Kraka ophiolite massifs can be used. The massifs occur on the western slope of the Southers Urals. In this work we studied ultramafic rocks and their influence on the formation of the chemical composition of water. The research area is located in the northern part of the Zilair synclinorium, which occurs within the Central Ural megazone. In terms of hydrogeology, of particular importance to the territory of the synclinorium is the Zilair basin of fracture waters of the second order, which is part of the Uralian hydrogeologic folded zone. The ultramafic rocks from the studied area have consistently high CaO/Al2O3 ratios (0.4–1.6), which indicates the widespread development of parageneses with participation of clinopyroxene and a low degree of depletion of the primitive mantle source. Because of the complex geological structure of the area, water samples collected from both water points in the Kraka massifs, and the surrounding Early–Middle Paleozoic rocks were analyzed for major ions using a laboratory method to identify possible hydro-geochemical zoning. A statistical analysis was then conducted based on the obtained anion–cation composition data. From the viewpoint of the hydrolytic concept, the formation of the chemical composition of groundwater takes place due to the removal of Mg2+ from the rock-forming minerals of ultramafic rocks (olivine and pyroxene) and the supply of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and SO42− Cl− from atmospheric precipitations. The bicarbonate anion has a complex nature, where both biochemical processes in the soil and atmospheric precipitation play a significant role. Magnesium–bicarbonate-type of waters, due to low mineralization (to 1 g/L) and the majority of other geochemical parameters (pH of the medium, and content of Na, K, Ca, SO4, and Cl), whose values that are within the limits set by the World Health Organization (WHO), can be used as drinking water. The increased values of total hardness (0.20–3.39 mmol/L) in accordance with the regulatory document SanPiN 1.2.3685–21, adopted by the Russian Federation, do not exceed the maximum permissible concentrations (up to 7.00 (10.00) mEq/L or 3.50 (5.00) mmol/L). The high magnesium content, in accordance with GOST (state standard) R 54316–2020, allows the magnesium–bicarbonate waters of the Kraka massifs to be classified as table mineral waters for the treatment of various diseases (including hypomagnesemia).

1. Introduction

Groundwater, being one of the most important natural resources as it serves as a source of drinking water for 2.5 billion people [1], is under threat due to such factors as climate change, natural and anthropogenic pollution, etc. [2,3,4]. Arsenic contamination affects over 200 million people in regions like Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam, and parts of Latin America, causing chronic health issues including cancer, skin lesions, and cardiovascular disease [5]. Groundwater salinization, driven by overexploitation, sea level rise, and irrigation return flows, impacts over 1 billion people in coastal aquifers (e.g., Mediterranean Basin and the North China Plain) and arid inland areas (e.g., the Middle East and Australia), elevating salinity beyond WHO limits (>1 g/L TDS) and rendering water undrinkable [6,7,8]. More than 2 billion people in the world live in the regions with a severe water shortage [9,10]. The problem of providing certain regions with high-quality drinking water is discussed in [11,12]. Magnesium–bicarbonate waters that occur in rocks of ultrabasic and basic composition can provide the population with drinking water resources. This type of groundwater is widely studied by researchers around the world [13,14,15,16,17,18]. The risks of possible contamination of aquifers with heavy metals (Cr, Ni, etc.) contained in the rock-forming and accessory minerals of ultrabasic and basic rocks are reported in [19,20,21,22,23].

These issues highlight the value of uncontaminated groundwater sources, such as magnesium–bicarbonate waters from ultramafic terrains, which offer low-salinity alter-natives with beneficial Mg content for regions facing salinization or metal pollution [13,14,15,16,17,18].

In connection with the impending global water crisis, water resources are becoming a strategic factor in the long-term development of the global economy, including that of Russia. A corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, V.I. Danilov-Danilyan, mentions that in the western and southern regions (the Republic of Kalmykia, some areas of the Lower Volga region, Stavropol, Krasnodar Territory, Kurgan, Chelyabinsk, Orenburg, Rostov, Moscow regions, etc.) there is a shortage of fresh water [24], and by 2030–2035, the problem will affect the territory of the Republic of Bashkortostan. The study of groundwater quality is one of the main hydrogeological tasks determining the possibility of using these waters for drinking purposes [25]. An increase in the share of groundwaters in the water supply, owing to their consistently high quality compared to surface water, will help solve the water shortage.

In the Republic of Bashkortostan (Russian Federation, Volga Federal District), fresh groundwater resources that can be used in economic activities are unevenly distributed [26]. As the population of the republic grows and the environmental situation in the region deteriorates, it is necessary to look for new sources of fresh groundwaters. Groundwater from the Zilair basin, which is part of the Ural complex hydrogeological folded region, can be used for supplying the eastern part of the region. The Zilair basin of fractured waters of the second order is located in the territory of the Zilair synclinorium, which is part of the Central Ural megazone on the western slope of the Southern Urals [27]. The magnesium–bicarbonate-type groundwater is extremely rare in the Southern Urals and typically occurs in the ultrabasic and basic rocks of the Kraka ophiolite massif [27]. The massifs consist of four separate bodies with a total area of more than 900 Km2: Northern, Middle, Uzyansky and Southern Kraka. In order to identify the interaction of the components of the “groundwater–rock” system in the formation of the chemical composition of water [28], as well as to assess its quality for use in economic purposes, during fieldwork in 2016–2024, both rock material and water samples from water points were collected from the territory of the Kraka massifs.

2. History of Geological and Hydrogeologic Studies

The history of the geological study of the Kraka massifs dates back to the second half of the 19th century. The ultramafic rocks of this territory were first mentioned in the works of N.F. Chernyshev, R.I. Murchison, and A. Shtukenberg. In the 1920–30s, when systematic geological survey works and searches for chrome ore and chrysotile asbestos started, the search teams of the “Bashchromite” Trust and other organizations worked in the territory of the massifs. In the 1960s, a geological survey (scale 1:50,000) supervised by A.V. Klochikhin was conducted at the massifs. The material composition of ultramafic rocks was analyzed by S.V. Moskaleva, G.N. Savelyeva, E.A. Denisova, S.G. Kovalev, V.I. Snachev, D.E. Saveliev, and E.N. Savelieva; microstructural studies were carried out by E.A. Denisova, G.N. Savelieva, and D.E. Saveliev [29,30,31,32,33]. Despite the two-century history, the massifs were studied to varying degrees. This is especially true for the Southern Kraka, the western and southwestern parts of which have been best studied. Most of the deposits and ore occurrences of chromitites (Apshakskaya and Malobashartovskaya areas) of the massif occur in these well-studied locations [31,34], while the eastern part has not been sufficiently studied.

The first information about the hydrogeology of the Zilair synclinorium was reported by M.O. Kler in his work in 1928. Later, researchers such as D.I. Itkin and N.N. Tostunov were engaged in hydrogeology. In 1962–1969, the Kagarmanov Party (supervised by A.V. Klochikhin) analyzed the chemical composition of water from water points both in the territory of the Kraka massifs and host rocks. R.F. Abdrakhmanov studied the geochemistry and the conditions of the formation of groundwater in the Southern Urals, including fracture waters of the second order in the Zilair basin [27].

3. Geological and Hydrogeological Characteristics

3.1. Stratigraphy of Host Rocks

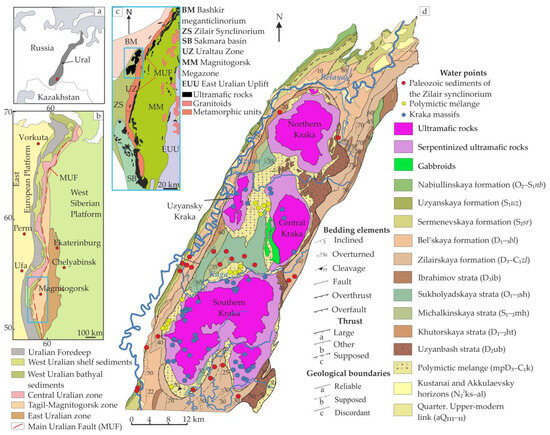

The framing of the Kraka massifs is made up of Paleozoic sediments forming two lithologically different sections:

- The carbonate–terrigenous section, represented by sediments from the Nabiullinskaya (O2–S1nb) to the Zilair formation (D3–C1zl), and located in the western part of the synclinorium;

- The terrigenous–siliceous section composed of rocks from the Sukholyadskaya strata (O1–3sh) to the Zilair formation (D3–C1zl) in the eastern part of the synclinorium (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of the study area in the northern Zilair synclinorium, Southern Urals. (a) Overview map; (b,c) schematic geological maps of the Southern Urals [35,36]; and (d) detailed geological map showing Kraka ophiolite massifs and host rocks [37,38,39,40,41].

Figure 1. Location of the study area in the northern Zilair synclinorium, Southern Urals. (a) Overview map; (b,c) schematic geological maps of the Southern Urals [35,36]; and (d) detailed geological map showing Kraka ophiolite massifs and host rocks [37,38,39,40,41].

Virtually all throughout the boundaries of the massifs, sedimentary strata are separated from ultramafic rocks by polymictic melange (mpD3–C1), which is made up of blocks of rocks of various ages and compositions. Moreover, the volcanic rocks of the Uzyanbash strata (D2ub (variolites and hyalobasalts)) are widespread along the eastern border of the massifs (Figure 1d).

3.2. Geologic Structure of the Kraka Massifs

The Kraka massifs cover an area of about 900 km2 and consist of four separate bodies of different sizes. The Northern Kraka is an isometric body 20 × 15 km in size and is composed mainly of lherzolites (65–70% olivine, 10–25% orthopyroxene, 5–10% clinopyroxene, and 0.5–3% Cr-spinel), and less often harzburgites, as well as striped, lenticular, or columnar dunite bodies [32,33].

The Central Kraka, covering an area of 180 km2, has the most diverse geological structure: ultramafic rocks (peridotites and, less frequently, dunites), which make up 80% of the territory; mafic rocks, forming a meridionally elongated body 0.5–1.5 km wide in the west of the massif, and rocks of the wehrlite–clinopyroxenite transitional complex, occupying an intermediate position. The central and eastern parts of the massif are represented by spinel lherzolites and clinopyroxene-bearing harzburgites. Dunite bodies and spinel-plagioclase peridotites also occur among the rocks [31,32]. The Uzyansky Kraka (45 km2) is composed of 75% rocks of the dunite–harzburgite complex (harzburgites, dunite–harzburgites, and dunites) and 20–25% marginal serpentinites [32,34]. The largest of the four massifs is the Southern Kraka, with an area of 450 km2. It is a virtually isometric body separated in the south into eastern and western branches. Spinel peridotites and dunites participate in the structure of the massif. The western part of the territory is composed of rocks of the dunite–harzburgite complex. In addition to harzburgites, spinel lherzolites are also present in the northern and central parts of the massif. Plagioclase-containing lherzolites with a low degree of serpentinization (15 vol.%) are sporadic [42]. Serpentinites are distributed along the periphery of all massifs, where the rock-forming minerals are either preserved as relics or completely replaced by mesh-textured serpentinite. The near-fault zones are dominated by fibrous chrysotile serpentinites, while in the rare outcrops at the Middle and Uzyansky Kraka massifs the presence of stubachites was detected [32].

3.3. Hydrogeological Characteristics of the Northern Part of Zilair Synclinorium

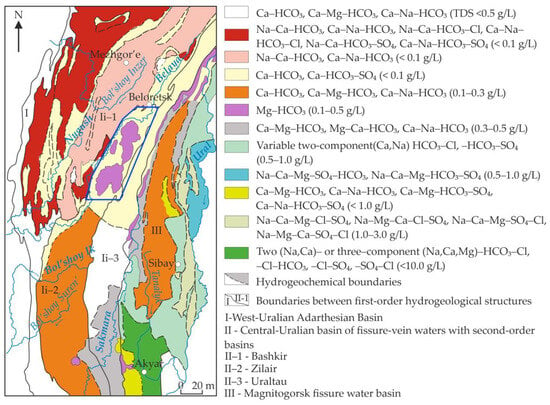

According to the modern concepts, in the territory of the Zilair synclinorium there is a basin of fracture waters of the second order, which is part of the Ural hydrogeological folded system (Figure 2) [27].

Figure 2.

Hydrogeochemical map of the Southern Urals, highlighting the Zilair basin of fracture waters [27].

The groundwater recharge in this territory comes from atmospheric precipitations. The aquifer rocks in the western part of the territory are represented by the carbonate–terrigenous rocks of the Nabiullinskaya (O3–S1nb), Uzyanskaya (S1uz), Sermenevskaya (S2sr), and Belskaya formations (D1–3bl). Clay rocks are confining beds. The Ordovician–Devonian aquifer complex (O–D) occurs as a narrow band in the western part of the Zilair synclinorium. The depth of groundwaters, coming to the surface in the form of springs in the areas of limestone outcrops in the Lower Devonian, frequently forming steep cliffs along the Belaya river, reaches 80–100 m, and within the area of development of other breeds it reaches 50–70 m. Groundwaters in the distributed territory of ultramafic rocks occur at a depth of <10–15 m. They appear in the marginal parts of the massifs in the form of numerous, mainly dispersed sources emerging from the debris of serpentinites. The groundwaters have a magnesium–bicarbonate composition (Figure 2). The rate of spring flows averages 0.1–0.3 L/s and mineralization is 0.1–0.5 g/L [27,38].

4. Materials and Methods

During fieldwork conducted from 2016 to 2023, ultramafic rocks were selected from the Northern and Southern Kraka massifs. Data on the petrochemistry of rocks from the Middle and Uzyansky Kraka massifs from [32,43] were also used. A total of 143 samples were analyzed (Tables S1–S4). To determine the bulk composition of the rocks, tablets (pressed powder pellets) were prepared, which were then analyzed for major oxides and some trace elements (X-ray fluorescence analysis) using a Xenemetrix X-Calibur energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer at the Institute of Geology, Ufa Federal Research Center, Russian Academy of Sciences, Ufa. The detection limit for petrogenic oxides and elements was set as 0.01–0.2 wt. %, and for trace elements it was 5–10 ppm. The samples were ground entirely (ca. 150 g), and then 5 g portions were mixed with binder (poly-vinyl alcohol) and pressed at 25–27 g/cm2 onto boric acid substrates. The loss on ignition (LOI) was determined gravimetrically. The standards for ultramafic rocks included SDU-1 (dunite, IGC SB RAS, Irkutsk, Russia), MU-2, MU-3, and MU-4 (serpentinized dunite, hornblendite, and kimberlite, respectively; IGEM RAS, Moscow, Russia).

As ophiolitic ultramafic rocks are prone to regressive serpentinization, chemical analyses were recalculated for anhydrous composition in order to restore their primary nature, and on this basis the normative mineral composition, including three main rock-forming minerals—olivine, enstatite and diopside—was calculated. The calculation method used in the work was developed by N.D. Sobolev (1952) [44] and automated with the use of Excel tools. To determine the amounts of olivine (Ol), orthopyroxene (Opx), and clinopyroxene (Cpx) in the ultramafic rocks using this method, three equations are solved: Di + En + Ol = MgO + 2Fe2O3 + FeO + CaO + MnO; Di + En + 1/2 Ol = SiO2; and Di = 2CaO.

The water samples were taken in 2024 from the water points of both the territory of the Kraka massifs and their host sedimentary rocks. The work also uses water analyses from the stock report on reserves for 1962–1969, prepared by the Kagarmanov Party under supervision by A.V. Klochikhin (Tables S5–S7). A total of 89 samples were analyzed. The sampling was carried out both from springs and mine workings (holes, pits, and wells), as well as from streams fed by springs emerging from fracture magmatic and sedimentary rocks in the territory. The analysis of water with regard to anions and cations, hardness, mineralization, and pH was conducted using a laboratory ionomer I–160MI (Moscow, Russia) and a capillary electrophorese Kapel–105 M and Kapel–205 (Saint-Petersburg, Russia) according to regulatory documents (state standards (GOST 31867–2012 and GOST 31869–2012); methodology (M 01–58–2018); and environmental regulatory documents of the Russian Federation (ERD F 14.1:2:3:4.121–97, ERD F 14.1:2:3:98–97, ERD F 14.1:2:4.167–2000, and ERD F 14.1:2:4.261–2010)) [45,46,47,48,49,50,51] in the laboratory center of the Hygiene and Epidemiology Center in the Republic of Bashkortostan, Ufa. The obtained data on the chemical composition of water from the weight form (mg/L) were converted into molar (mmol/L) and percentage molar (mol.%). The analyzed and recalculated data on the anion and cation composition of water were shown on the diagrams by A.M. Piper (1944) [52] and G.A. Stiff (1951) [53]. Statistical data processing was carried out using Excel tools.

5. Results

5.1. Analysis of the Chemical Composition of Rocks from the Kraka Massifs

The chemical composition of ultramafic rocks from the Kraka massifs is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative analyses of ultramafic rocks from the Kraka massifs (wt.%).

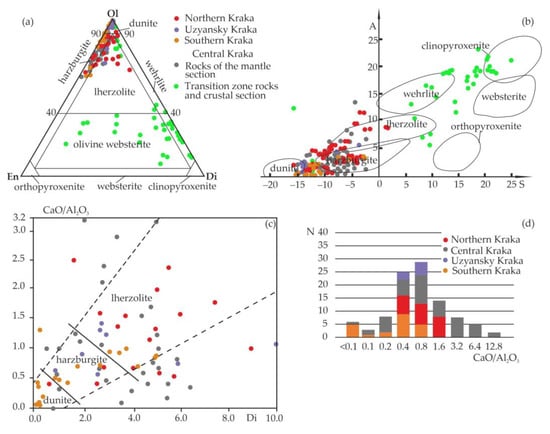

The recalculation of chemical analyses of rocks for the normative mineral composition shows that ultramafic massifs are mainly composed of dunites and harzburgites (Uzyansky and Southern Kraka) and to a lesser extent by lherzolites (Northern Kraka) (Figure 3a,b).

Figure 3.

Petrochemical characteristics of ultramafic rocks from Kraka massifs (data include samples from [32,43]). (a) Normative mineral composition; (b) A–S diagram [54] (A = Al2O3 + CaO + Na2O + K2O; S = SiO2 − Fe2O3 − FeO − MgO − MnO − TiO2); (c) diopside (Di,%) vs. CaO/Al2O3 diagram; and (d) histogram of CaO/Al2O3 ratios.

The Middle Kraka has a richer petrographic composition: in addition to the mantle section (peridotites and dunites), there are rocks of the transition zone and crustal section (clinopyroxene-bearing dunites, werlites, olivine websterites, and clinopyroxenites) (Figure 3a,b; Table 1 and Tables S1–S4). All studied ultramafic rock samples, to a greater or lesser degree, undergo serpentinization. The degree of serpentinization varies from 15 vol.% for plagioclase-bearing lherzolites up to 80 vol.% for dunites and harzburgites [42]. In all studied thin sections, serpentine is not accompanied by very fine-grained magnetite, which indicates that it belongs to early mesh-textured serpentine.

The content of SiO2 in peridotites and dunites varies by 30.50–46.00 wt.%, as does TiO2 by 0.01–0.4 wt.%, Al2O3 by 0.07–12.1 wt.%, Fe2O3 by 1.00–10.04 wt.%, FeO by 0.30–6.6 wt.%, MnO by 0.02–0.18 wt.%, CaO by 0.01–4.9 wt.%, MgO by 31.00–47.00 wt.%, Na2O by 0.01–2.51 wt.%, and K2O by 0.01–0.25 wt.%. The iron content (f) varies in the range of 5.28–15.63%. The increased values of low-melting components and iron content are typical of rocks from the transition zone and the crustal section of the Middle Kraka: SiO2—34.85–52.00 wt.%; TiO2—0.01–1.15 wt.%; Al2O3—1–16.6 wt.%; Fe2O3—1.00–14.81 wt.%; FeO—1.00–9.80 wt.%; MnO—0.07–0.23 wt.%; CaO—0.56–21.28 wt.%; MgO—11.60–42.00 wt.%; Na2O—0.06–4.05 wt.%; and K2O—0.01–0.75 wt.%; f = 7.47–37.66%.

The content of the three main rock-forming minerals varies significantly. Most of the studied samples contain diopside (Di) from 0.03(0.67)–1.53% in harzburgites to 10.00–16.97% in lherzolites. The most significant variations in these values are observed for the rocks of the Northern (0.55–16.97%) and Middle Kraka massifs (0.67–9.61%), which are more stable than the Southern (0.03–5.00%) and Uzyansky Kraka (0.84–10.00%). The concentration of normative enstatite (En) in ultramafic rocks ranges from 0.65 to 36.16% and increases from the dunites of the Uzyansky Kraka (0.65%) to the peridotites of the Southern Kraka (30.72–31.84%) and the harzburgites of the Middle Kraka (to 36.16%). Normative olivine (Ol) in all rocks in the massifs increases statistically regularly from lherzolites and harzburgites (62.82–88.89%) to dunites (90.41–99.02%). For clinopyroxene–containing dunites, werlites, and pyroxenites (olivine, clinopyroxenite, and websterite) in the Middle Kraka, the content of rock-forming minerals varies as follows: Di = 1.76–85.10%, En = 0.21–66.03%, and Ol = 7.87–97.92%. The analysis of variations in the CaO/Al2O3 ratio, as one of the empirical criteria for the residual origin of spinel peridotites [55], showed that consistently high values of this indicator are typical of peridotites from all four massifs. This indicates the widespread development of parageneses involving clinopyroxene (Figure 3c) and the low degree of depletion of rocks by low-melting components [32]. In the majority of analyses of ultramafic rocks, the CaO/Al2O3 ratio varies between 0.4 and 1.6 (Figure 3d). Increased values of this parameter (1.7–8.4 and higher) are typical of dunites and peridotites from the Northern and Middle Kraka, as well as of rocks from the transition zone and crustal section [32].

5.2. Analysis of the Chemical Composition of Groundwaters on the Territory

The groundwaters of the massifs and their host rocks have a diverse chemical composition. Because of the complex geological structure of the northern part of the Zilair synclinorium, composed of igneous and sedimentary rocks, and the observed patterns of changes in the anionic–cationic composition of groundwater, we decided to divide the analyses into three groups (Table 2, Table 3 and Tables S5–S7): waterpoints in the area of occurrence of the Paleozoic sediments (from Nabiullinskaya to Zilair formations O2–3nb–D3–C1zl), sediments of polymictic melange (mpD3–C1k) of the Upper Devonian–Lower Carboniferous, and ultramafic rocks from the Kraka massifs.

Table 2.

Water samples from water points in the northern part of the Zilair synclinorium.

Table 3.

Representative chemical analyses of groundwater from water points in the northern part of the Zilair synclinorium.

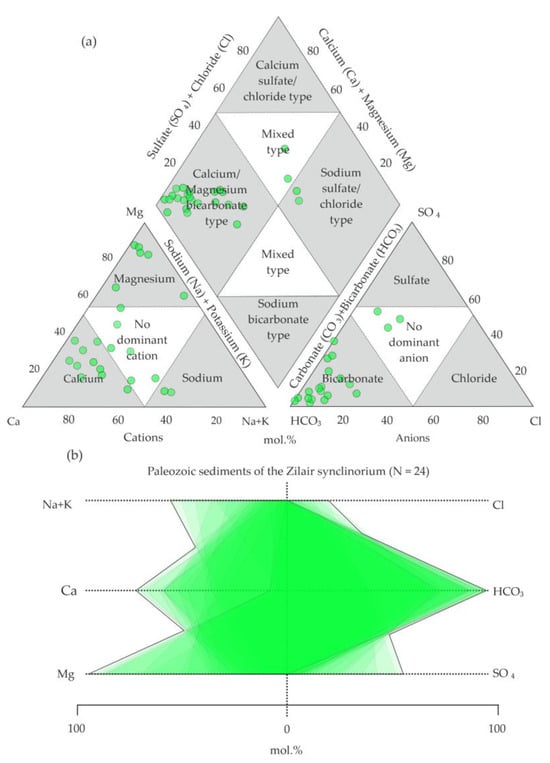

In the diagram by A.M. Piper [52,56], the analyses of the territory of the host rocks are localized in the field of calcium/magnesium–bicarbonate-type waters (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Water analyses from Paleozoic sediments (O2–3nb–D3–C1zl) on (a) Piper diagram (modified from Hatari Labs) [52,56] and (b) Stiff diagram [53].

Calcium cations are predominant (Figure 4b), while magnesium cations are less common. Single analyses show a more diverse chemical composition, where sulfate, chloride anions, and sodium cations become more significant. The analyses of the water from the polymictic melange area indicate magnesium–bicarbonate and complex (calcium–sodium–magnesium–bicarbonate–sulfate, calcium–sodium–bicarbonate–sulfate, sodium–calcium–sulfate–bicarbonate) compositions (Figure 5a).

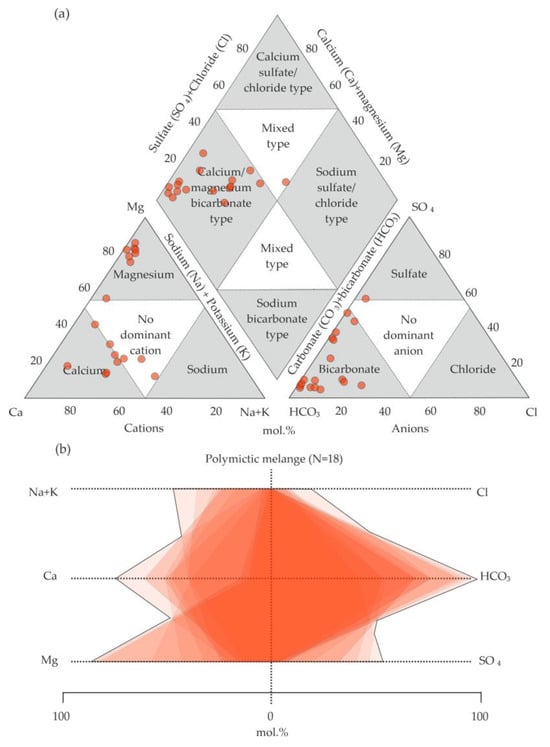

Figure 5.

Water analyses from polymictic melange (mpD3–C1k) on (a) Piper diagram (modified from Hatari Labs) [52,56] and (b) Stiff diagram [53].

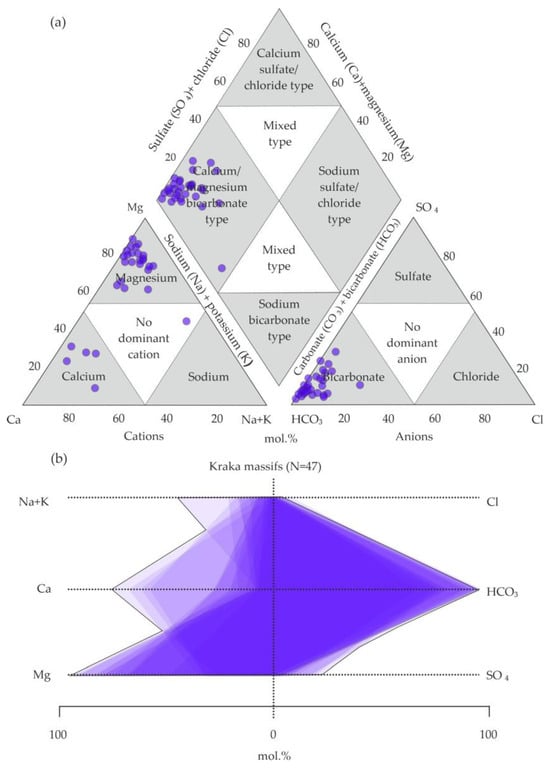

The calculated analyses show approximately equal amounts of calcium and magnesium, which does not imply the predominance of one cation in the chemical composition of water (Figure 5a,b). The water analyses of the Kraka massif demonstrate a more homogeneous chemical composition, with a predominance of bicarbonate anions and magnesium cations (Figure 6a,b).

Figure 6.

Water analyses from Kraka massifs on (a) Piper diagram (modified from Hatari Labs) [52,56] and (b) Stiff diagram [53].

The mineralization of groundwater on the territory of the host rocks is 0.04–0.50 g/L, the total hardness is 0.20–3.10 mmol/L, and the pH of the medium is 6.80–8.84 (Table S5). For streams and springs flowing through polymictic melange rocks, the water mineralization is 0.04–0.47 g/L, the total hardness is 0.45–1.25 mmol/L, and the pH of the medium is 6.80–8.76 (Table S6). In the analyses of water from water points on the territory of the Kraka massifs, the mineralization is 0.06–0.90 g/L, the total hardness is 1.05–3.39 mmol/L, and the pH of the medium is 7.0–8.88 (Table S7).

6. Discussion

6.1. Hydrogeochemical Zonation and Conditions of Formation of Magnesium–Bicarbonate Waters of the Kraka Massifs

A hydrogeochemical zonation is generally defined as a portion of a groundwater ba-sin (or aquifer) that is relatively homogeneous in water chemistry, within which the hydrogeochemical indicator (or sum of indicators) used to define the zones varies within relatively narrow, conventionally defined boundaries. It is through the identification of correlations that the hydrogeochemical zoning of specific territories can be performed.

The construction of the correlation diagrams of groundwaters from the northern part of the Zilair synclinorium, from the standpoint of the hydrolytic concept of formation of the chemical composition of groundwaters, showed dependencies between individual geochemical parameters. In spite of the virtually homogeneous magnesium–bicarbonate composition of groundwaters in the territory of the Kraka massifs, there are some correlations between ions (SO4−, Cl−, Na + +K+, and Ca2+), the content of which increases from the Kraka massifs to the host rocks (Tables S5–S7).

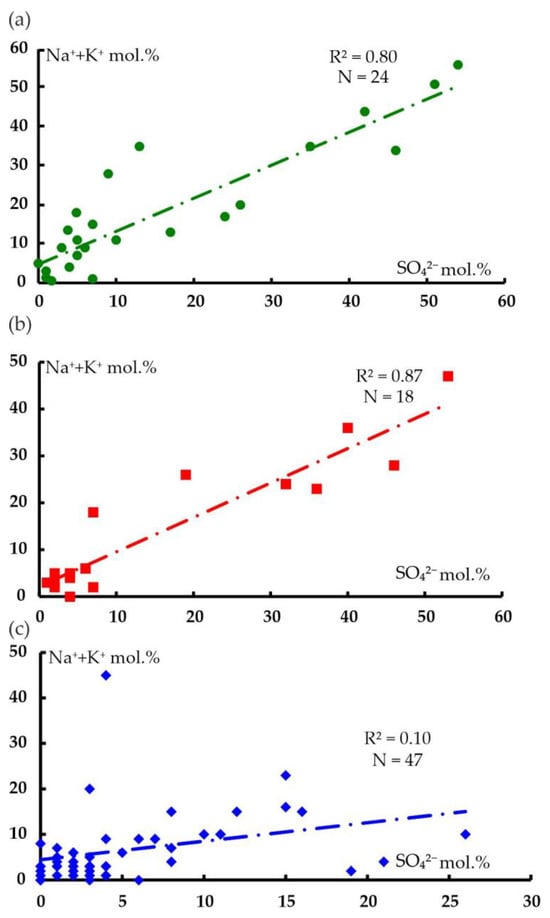

A close positive relationship in the groundwater of the Zilair synclinorium is common in sulfate anions and sodium and potassium cations (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Correlation diagrams for the contents of sulfate anions and sodium and potassium cations in the analyses for water points of the following distribution areas: (a) Paleozoic sediments (O2–3nb–D3–C1zl) (N = 24, R2min = 0.16); (b) polymictic melange (mpD3–C1k) (N = 18, R2min = 0.22); and (c) ultramafic rocks of the Kraka massifs (N = 47, R2min = 0.08).

A proportional increase in the average ion content from the Kraka massifs (Na + K 6.7%, SO4 5.6%) takes place from polymictic melange (Na + K 14.6%, SO4 16.8%) to host rocks (Na + K 18.2%, SO4 15.8%). Moreover, increased values of sodium, potassium cations (up to 51.0–56.0%), and sulfate anions (up to 51.0–54.0%) are typical of the analyses of water, with mineralization of no more than 0.16–0.17 g/L (less often 0.32–0.4 g/L). Such close relationships between sodium, potassium, and sulfate anions in the analysis of water from the territory of host rocks and polymictic melange can be explained by their joint supply from atmospheric precipitations, which serve as a significant source of dissolved substances. The average annual mineralization of precipitations in the Southern Urals is 20 mg/L. The precipitations have a mixed composition, mainly comprising sulfate (50.0–59.7%), bicarbonate (23.5–30.6%), and chloride anions (up to 26.5%). Among the cations, calcium (37.7–49.9%), magnesium (30.8–39.1%), and sodium (8.1–22.0%) play a significant role. [27].

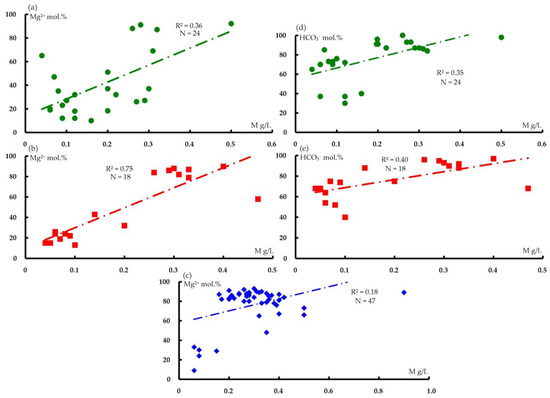

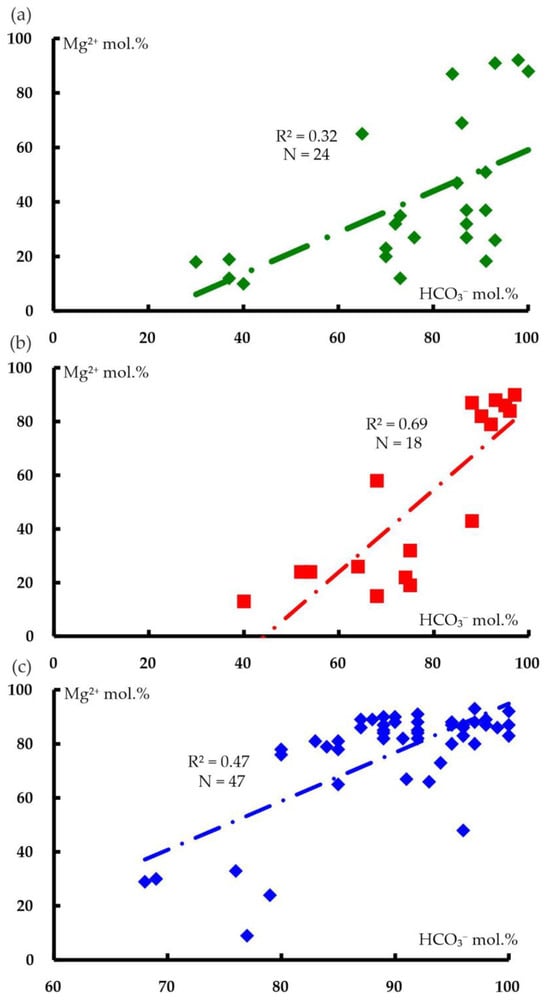

Medium-strength correlations are observed between magnesium cations and bicarbonate anions, and mineralization (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Correlation diagrams for mineralization and content of magnesium cations (a–c) and bicarbonate anions (d,e) in the analyses of water from water points in the following distribution areas: (a,d) Paleozoic sediments(O2–3nb–D3–C1zl) (N = 24, R2min = 0.16); (b,e) polymictic melange (mpD3–C1k)(N = 18, R2min = 0.22); and (c) ultramafic rocks of the Kraka massifs (N = 47, R2min = 0.08).

Figure 9.

Correlation diagrams for the contents of bicarbonate anions and magnesium cations in the analyses of water from water points in the following areas: (a) Paleozoic sediments (O2–3nb–D3–C1zl) (N = 24, R2min = 0.16); (b) polymictic melange (mpD3–C1k) (N = 18, R2min = 0.22); and (c) ultramafic rocks of the Kraka massifs (N = 47, R2min = 0.08).

An obvious inverse relationship exists between the contents of calcium and magnesium cations, with a gradual predominance of the latter in the host rocks (average values of Ca 41.1%, Mg 40.6%), followed by polymictic melange (Ca 36.2%, Mg 49.3%) and the Kraka massifs (Ca 16.7%, Mg 76.5%). Data on the chemical composition and correlations suggest that the formation of the anionic–cationic composition of the groundwater in the Kraka massifs is related to the removal of magnesium from rock-forming minerals (olivine and pyroxene), and that the supply of bicarbonate anions is associated with biochemical processes in the soil or atmospheric precipitation. The presence of magnesium cations in the analyses of water from the territory of host rocks and polymictic melange (Tables S5 and S6) is the result of its supply from ultramafic massifs.

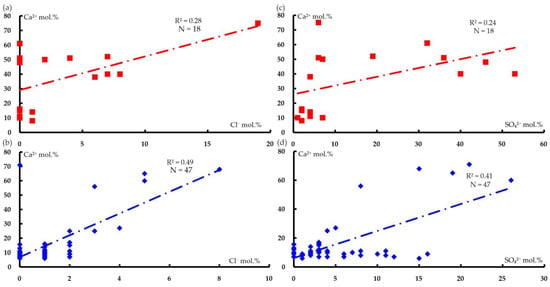

Less close relationships are observed between calcium cations, and chloride and sulfate anions (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Correlation diagrams for the contents of chloride anions and calcium cations (a,b) and contents of sulfate anions and calcium cations (c,d) in the analyses of water from water points the following areas: (a,c) polymictic melange (mpD3–C1k) (N = 18, R2min = 0.22) and (b,d) ultramafic rocks of the Kraka massifs (N = 47, R2min = 0.08).

The same was observed in the case of sulfate anions and sodium and potassium cations; they were supplied by atmospheric precipitations to the groundwaters of the Kraka and polymictic melange areas. Thus, the formation of the chemical composition of magnesium–bicarbonate groundwater in the Kraka massifs occurred due to the release of magnesium cations from the rock-forming minerals of ultramafic rocks and the introduction of bicarbonate anions from the soil, or, like other ions, from atmospheric precipitation.

6.2. Comparison of the Magnesium–Bicarbonate Waters of the Kraka Massifs with Other Objects

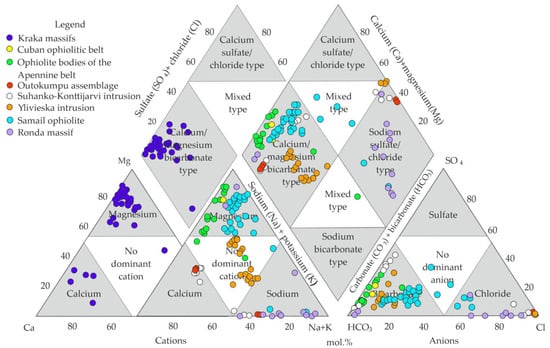

Figure 11 and Table 4 demonstrate comparison of magnesium–bicarbonate waters of the Kraka massifs, with the analyses of water collected by researchers [13,14,15,17,18] from the ultramafic rocks of ophiolite and intrusive massifs.

Figure 11.

Comparison of magnesium–bicarbonate waters of the Kraka massifs with groundwaters from other ophiolite and intrusive massifs in the world [13,14,15,17,18].

Table 4.

Comparison of the chemical compositions of groundwater in various ophiolite and intrusive massifs [13,14,15,17,18].

As compared to other objects, the Kraka massifs have a more homogeneous water composition, with a predominance of magnesium cations and bicarbonate anions. The analyses of the water points from the Semail ophiolite complex (Oman), the Apennine (Italy), and the Cuban (Cuba) ophiolite belts showed that they are similar in chemical composition, but vary significantly in terms of anion–cation composition (Figure 11).

The ultramafic–mafic intrusive massifs (Suhanko–Konttijarvi, Ylivieska) and the Outokumpu association, which includes serpentinites, tremolite–chlorite–albite rocks, and black shales located in Finland, have calcium-bicarbonate, sodium–chloride, and mixed (two- and three-component cation) compositions (Figure 11 and Table 4).

The Ronda massif (Spain) is characterized by a drastically different highly alkaline water composition compared to the majority of the other studied ophiolite massifs (Figure 11). The composition is determined by low-temperature serpentinization during the infiltration of meteoric magnesium–bicarbonate water into serpentinite aquifers below the aeration zone [57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. An alternative model of formation is the hydration of olivine and pyroxene by fresh water in a closed system with atmospheric CO2 [61]. Similar waters exist on the territory of the Semail ophiolite complex [15,63]. In terms of the chemical composition, these are sodium chloride waters. The mineralization of these waters reaches 2.9–5.54 g/L and the pH of the medium is 11.5–12.0 (Table 4). This type of highly alkaline water has not been detected within the Kraka massif. Groundwater in the ultramafic zone occurs at depths of less than 10–15 m, making the formation of highly alkaline waters in the aeration zone impossible. Highly mineralized sodium–chloridewaters are generally not common within the Zilair fissure basin (Figure 2).

6.3. Assessment of the Quality of Groundwaters on the Territory of the Kraka Massifs and the Host Rocks for Drinking Purposes

The data on the chemical composition obtained from the analyses of water in the Kraka massifs and the Paleozoic sediments containing them were compared with the standards of the World Health Organization [64] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Assessment of the geochemical parameters of groundwater in the northern part of the Zilair synclinorium with standards established by the World Health Organization [64,65].

In terms of mineralization and the content of basic ions, the groundwater in the northern part of the Zilair synclinorium (both the territories of the Kraka massifs and their host rocks) does not exceed the maximum permissible values [64]. At the same time, the pH value of the medium and the Mg content for both groups of analyses exceed the established upper limit.

According to the regulatory document SanPiN (sanitary rules and regulations) 1.2.3685–21 [66] approved in the Russian Federation, the values of mineralization, the pH of the medium, and the total hardness do not exceed the maximum permissible concentrations (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of geochemical parameters of groundwater analyses in the northern part of the Zilair synclinorium with standards given in SanPiN 1.2.3685–21 [66].

Magnesium–bicarbonate waters in the territory of the Kraka massifs and their host rocks, in terms of the Mg content and mineralization, with respect to GOST R 54316–2020 [67] standards (Table 7), can be used as table mineral waters.

Table 7.

Representatives of groups of hydrochemical types of table mineral waters according to GOST R 54316-2020 [67].

Magnesium–bicarbonate waters found in the territory of the Russian Federation with a mineralization of up to 1 g/L are actively used as table minerals to strengthen bone tissue, teeth, normalize heart function, restore water balance, improve the digestive tract, and strengthen the nervous system. The deficiency of magnesium in the body leads to heart failure, the slowing of the conduction of nerve tissues, and the development of hypomagnesemia.

7. Conclusions

The comparative study of the compositional features of ultramafic rock samples from the Kraka massifs showed that the rocks are characterized by a varying degree of depletion, increasing from thespinel–plagioclase peridotites of the Northern Kraka to the spinel peridotites of the Southern Kraka.

The observed correlation between the chemical compositions of water from the water points and underlying ultramafic rocks indicates the interaction of the components of the groundwater–rock system during the formation of the anionic–cationic composition. This is confirmed in the correlation diagrams. There is also a distinct regularity in the change in the groundwater composition from the territory of Paleozoic sediments to the Kraka massifs. An inverse correlation is observed between the contents of calcium and magnesium cations, with a gradual increase in the latter closer to ultramafic rocks.

The comparison of the groundwater from the Kraka massifs with that from other ophiolitic and intrusive massifs showed that the magnesium–bicarbonate waters of these objects are low-mineralized, rarely exceeding 1 g/L, with the pH of the medium being lower than nine. The exception is the highly alkaline groundwater found by the researchers in Spain (Ronda massif) and Oman (Samali ophiolite), with a mineralization of 5.54 g/L and a pH to 11–12.

The comparison of the obtained values of mineralization, the pH of the medium, the total hardness and the anionic–cationic composition of groundwater in the territory of the Zilair synclinorium with the standards approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the regulatory documents SanPiN 1.2.3685–21 and GOST R 54316–2020 showed that these waters can be used as table mineral waters.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/geosciences16010008/s1. Table S1: Analyses of ultramafic rocks from the Northern Kraka massif; Table S2: Analyses of ultramafic rocks from the Central Kraka massif; Table S3: Analyses of ultramafic rocks from the Uzyansky Kraka massif; Table S4: Analyses of ultramafic rocks from the Southern Kraka massif; Table S5: Analyses of the chemical composition of water of Paleozoic sediments of the Zilair synclinorium; Table S6: Analyses of the chemical composition of water of polymictic melange; and Table S7: Analyses of the chemical composition of water of Kraka massifs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and writing, T.D.S., R.F.A., D.E.S., and E.A.M.; investigation, field work, and sample preparation, T.D.S., D.E.S., A.A.S., and R.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.D.S.; writing—review and editing, A.O.P., D.E.S., V.N.D., E.A.M., A.V.S., and R.A.G.; visualization, T.D.S., A.O.P., A.V.S., V.N.D., E.A.M., R.A.G., and A.A.S.; and project administration, T.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out using federal budget funds on the topics of the state assignment FMRS 2025-0016 “Geodynamics of the formation of structural–material complexes of the Southern Urals taking into account new data on their composition, structure, paleomagnetism, and hydrogeology” and FMRS-2025-0014 “Geological and genetic models of VMS, Cu- and Au-porphyry, orogenic gold, and chromite deposits of the Southern Urals”, approved by the conclusion of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "Russian Academy of Sciences".

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to T.S. Votentseva for preparing the manuscript in English.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yadav, P.; Sreekesh, S.; Nandimandalam, J.R. Groundwater Quality and Its Suitability in the Semi-Arid River Basin in India: An Analysis of Hydrogeochemical Processes Using Multivariate Statistics. Environ. Model. Assess. 2025, 30, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapworth, D.J.; Boving, T.B.; Kreamer, D.K.; Kebede, S.; Smedley, P.L. Groundwater Quality: Global Threats, Opportunities and Realising the Potential of Groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, I.; Singh, U.K. Hydrogeochemical Characterizations and Quality Evaluation of Groundwater in the Major River Basins of a Geologically and Anthropogenically Driven Semi-Arid Tract of India. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, S.; Surendran, S.; Roy, P.D.; Kamaraj, J. Groundwater Geochemistry and Irrigation Suitability in the Semi-Arid Melur Block of Madurai District, South India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhi, S.; Choudhury, R. Elevated groundwater arsenic in deeper aquifers of the Brahmaputra floodplains in Assam, India. J. Environ. Sci. Health Sustain. 2025, 1, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, A.D.; Bakker, M.; Post, V.E.A.; Vandenbohede, A.; Lu, C.; Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Simmons, C.T.; Barry, D.A. Seawater intrusion processes, investigation and management: Recent advances and future challenges. Adv. Water Resour. 2013, 51, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.; Sunkari, E.D.; Mickus, K.; Okyere, M.B. Groundwater salinization in inland basins of arid and semiarid climates: An overview. J. Environ. Sci. Health Sustain. 2025, 1, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörösmarty, C.; McIntyre, P.; Gessner, M.; Dudgeon, D.; Prusevich, A.; Green, P.; Glidden, S.; Bunn, S.E.; Sullivan, C.A.; Liermann, C.R.; et al. Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 2010, 467, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanakakis, V.A.; Paranychianakis, N.V.; Angelakis, A.N. Water Supply and Water Scarcity. Water 2020, 12, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Rijneveld, R.; Beier, F.; Bak, M.P.; Batool, M.; Droppers, B.; Popp, A.; van Vliet, M.T.H.; Strokal, M.A. Triple Increase in Global River Basins with Water Scarcity Due to Future Pollution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, S.R. Quality assessment of groundwater for drinking and irrigation use in semi-urban area of Tripura, India. Eco. Env. Cons. 2015, 21, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, K.; Mohammad, N.; Ali, W.; Muhammad, S.; Raziq, A. Geogenic Contamination of Groundwater in a Highland Watershed: Hydrogeochemical Assessment, Source Apportionment, and Health Risk Evaluation of Fluoride and Nitrate. Hydrology 2025, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskeeniemi, T.; Blomqvist, R.; Lindberg, A.; Ahonen, L.; Frape, S.; Posiva, O. Hydrogeochemistry of Deep Groundwaters of Mafic and Ultramafic Rocks in Finland; Posiva Oy: Helsinki, Finland, 1996; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, R.R. Hydrology of ultramafic rocks in Moa (Cuba). In Proceedings of the XXXIII Congress IAH&7 Congress ALHSUD ”Groundwater Flow Understanding from Regional and Local Scales”, Zacatecas City, Mexico, 11–15 October 2004; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Dewandel, B.; Lachassagne, P.; Bouldier, F.; Al-Hattali, S.; Ladouche, B.; Pinault, J.-L.; Al-Suleimani, Z. A conceptual hydrogeological model of ophiolite hard-rock aquifers in Oman based on a multiscale and a multidisciplinary approach. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S.; Shah, M.T.; Muhammad, S.; Khan, S. Role of mafic and ultramafic rocks in drinking water quality and its potential health risk assessment, Northern Pakistan. J. Water Health 2015, 13, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segadelli, S.; Vescovi, P.; Ogata, K.; Chelli, A.; Zanini, A.; Boschetti, T.; Petrella, E.; Toscani, L.; Gargini, A.; Celico, F. A conceptual hydrogeological model of ophiolitic aquifers (serpentinised peridotite): The test example of Mt. Prinzera (Northern Italy). Hydrol. Process. 2016, 31, 1058–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampouras, M.; Garrido, C.J.; Zwicker, J.; Vadillo, I.; Smrzka, D.; Bach, W.; Peckmann, J.; Jimenez, P.; Benavente, J.; Garcia-Ruiz, J.M. Geochemistry and mineralogy of serpentinization-driven hyperalkaline springs in the Ronda peridotites. Lithos 2019, 350–351, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.T.; Ara, A.; Muhammad, S.; Khan, S.; Tariq, S. Health risk assessment via surface water and sub-surface water consumption in the mafic and ultramafic terrain, Mohmand agency, northern Pakistan. J. Geochem. Explor. 2012, 118, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.T.; Ara, J.; Muhammad, S.; Khan, S.; Asad, S.A.; Ali, L. Potential heavy metal accumulation of indigenous plant species along the mafic and ultramafic terrain in the Mohmand agency, Pakistan. Clean-Soil Air Water 2014, 42, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Lu, Y.; Khan, H.; Zakir, S.; Ihsanullah, S.; Khan, A.A.; Wei, L.; Wang, T. Health risks associated with heavy metals in the drinking water of Swat, northern Pakistan. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25, 2003–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.; Muhammad, S.; Malik, R.N.; Khan, M.U.; Farooq, U. Status of heavy metal residues in fish species of Pakistan. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 230, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.C.; Vieira, L.C.G.; Bernardi, J.V.E.; Pereira, T.A.M.; Walkimar, A.C.J.; Silva, W.P.; Santos, L.A.G.; Goncalves, J.F., Jr.; Nabout, J.C.; Diniz-Filho, J.A.F.; et al. Combined effects of land use and geology on potentially toxic elements contamination in lacustrine sediments from the Araguaia River floodplain, Brazilian Savanna. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov-Danilyan, V.I.; Katsov, V.M.; Porfiryev, B.N. Ecology and climate: Where we are now and where we will be in two to three decades. The situation in Russia. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2023, 93, 1032–1046. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakutin, V.P.; Golitsyn, M.S.; Shvets, V.M. Current problems of studying and assessing the quality of underground drinking waters. Water Resour. 2012, 39, 485–495. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Abdrakhmanov, R.F.; Poleva, A.O.; Nosareva, S.P.; Durnaeva, V.N. Technogenesis and its impact on fresh groundwater resources of the Southern Urals and the Cis-Urals. Geol. Bull. 2025, 144–158. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdrakhmanov, R.F.; Popov, V.G. Geochemistry and Formation of Groundwater in the Southern Urals; Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Bashkortostan, Gilem: Ufa, Russia, 2010; p. 420. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Krainov, S.R.; Ryzhenko, B.N.; Shvets, V.M. Geochemistry of Groundwater: Theoretical, Applied, and Environmental Aspects; TsentrLitNefteGaz: Moscow, Russia, 2012; p. 213. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Moskaleva, S.V. Hyperbasites and Their Chromite-Bearing Potential; Nedra: Leningrad, Russia, 1974; p. 279. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Savelieva, G.N. Gabbro–Ultrabasic Complexes of Ural Ophiolites and Their Analogues in Modern Oceanic Crust; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1987; p. 246. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Snachev, V.I.; Saveliev, D.E.; Rykus, M.V. Petrogeochemical Features of Rocks and Ores of the Kraka Gabbro–Hyperbasite Massifs; Bashkir State University: Ufa, Russia, 2001; p. 212. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Saveliev, D.E.; Snachev, V.I.; Savelieva, E.N.; Bazhin, E.A. Geology, Petrochemistry, and Chromite-Bearing Capacity of Gabbro–Hyperbasite Massifs of the Southern Urals; DesignPolygraphService: Ufa, Russia, 2008; p. 320. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Saveliev, D.E.; Gataullin, R.A. Lherzolites of the Aznagulov area (Southern Urals): Composition and P–T–fO2 formation conditions. Bull. Acad. Sci. Repub. Bashkortostan 2021, 40, 15–25. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveliev, D.E. Ultramafic Massifs of Kraka (Southern Urals): Structure and Composition of Peridotite–Dunite–Chromite Associations; Bashkir Encyclopedia: Ufa, Russia, 2018; p. 204. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Puchkov, V.N. Structure and geodynamics of the Uralian orogen. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1997, 121, 201–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveliev, D.E.; Shilovskikh, V.V.; Makatov, D.K.; Gataullin, R.A. Accessory Cr-spinel from peridotite massifs of the South Urals: Morphology, composition and origin. Miner. Petrol. 2022, 116, 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazev, Y.G.; Knyazeva, O.Y. State Geological Map of the Russian Federation. Scale 1:200,000, 2nd ed.; South Ural Series; Sheet N-40-XXIII Beloretsk. Explanatory Note; Bashkirgeologiya: Ufa, Russia, 2006; p. 194. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Larionov, N.N.; Bergazov, I.R. State Geological Map of the Russian Federation. Scale 1:200,000, 2nd ed.; South Ural Series; Sheet N-40-XXP (Tukan); Explanatory Note; VSEGEI: Moscow, Russia, 2015; p. 247. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev, Y.G.; Knyazeva, O.Y. State Geological Map of the Russian Federation. Scale 1:200,000, 2nd ed.; South Ural Series; Sheet N-40-XXVIII; Explanatory Note; VSEGEI: Moscow, Russia, 2015; p. 237. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Yakupov, R.R.; Mavrinskaya, T.M.; Abramova, A.N. Paleontological Justification of the Paleozoic Stratigraphy Scheme of the Northern Part of the Zilair Megasynclinorium; Institute of Geology, Ufa Scientific Center, RAS: Ufa, Russia, 2002; p. 160. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Mavrinskaya, T.M.; Yakupov, R.R. Ordovician sediments of the western slope of the Southern Urals and their correlation based on conodonts and chitinozoans. Geol. Geophys. 2016, 57, 333–352. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveliev, D.E.; Biembetov, A.I.; Shabutdinov, T.D.; Samigullin, A.A.; Gataullin, R.A. Mineralogical and geochemical features of ultramafic rocks in the eastern part of the Southern Kraka massif (Southern Urals). Georesources 2024, 26, 248–259. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveliev, D.E.; Nugumanova, Y.N.; Gataullin, R.A.; Sergeev, S.N. Ultramafites of the Uzyansky Kraka massif (Southern Urals). Geol. Bull. 2018, 3, 79–97. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, N.D. Ultrabasic Rocks of the Greater Caucasus; Gosgeolizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1952; p. 240. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- GOST 31867–2012; Drinking Water. Determination of Anion Content by Chromatography and Capillary Electrophoresis. Interstate Council for Standardization, Metrology and Certification (ISC): Moscow, Russia, 2019; p. 19. (In Russian)

- GOST 31869–2012; Water. Methods for Determination of Cation Content (Ammonium, Barium, Potassium, Calcium, Lithium, Magnesium, Sodium, Strontium) Using Capillary Electrophoresis. Interstate Council for Standardization, Metrology and Certification (ISC): Moscow, Russia, 2019; p. 23. (In Russian)

- M 01-58–2018; Quantitative Chemical Analysis of Water. Measurement of Mass Concentration of Chloride, Nitrite, Sulfate, Nitrate, Fluoride, and Phosphate Ions in Samples of Natural, Drinking, and Wastewater Using the “Kapel” Capillary Electrophoresis System. Federal Service for Accreditation of Measurement Procedures: Moscow, Russia, 2018. Available online: https://meganorm.ru/mega_doc/norm/metodika/3/pnd_f_14_1_2_4_157-99_kolichestvennyy_khimicheskiy_analiz.html (accessed on 14 December 2025). (In Russian)

- (ERD F) 14.1:2:3:4.121–97; Method for Measuring pH of Water Samples by Potentiometric Method (2018 Edition). Federal State Budgetary Institution “Federal Center for Analysis and Assessment of Technogenic Impact”: Moscow, Russia, 2018; p. 25. (In Russian)

- (ERD F) 14.1:2:3:98–97; Method for Measuring Total Hardness in Natural and Wastewater Samples by Titrimetric Method. Federal Center for Analysis and Assessment of Technogenic Impact: Moscow, Russia, 2016; p. 24. (In Russian)

- (ERD F) 14.1:2:4.167–2000; Method for Determining the Mass Concentration of Cations (Ammonium, Potassium, Sodium, Lithium, Magnesium, Strontium, Barium, and Calcium) in Drinking, Natural (Including Mineral), and Wastewater by Capillary Electrophoresis “Kapel”. Federal Center for Analysis and Assessment of Technogenic Impact: Moscow, Russia, 2000; p. 16. (In Russian)

- (ERD F) 14.1:2:4.261–2010; Method for determining the mass concentration of dry and calcined residues in drinking, natural, and wastewater by gravimetric method. Federal Center for Analysis and Assessment of Technogenic Impact: Moscow, Russia, 2015; p. 14. (In Russian)

- Piper, A.M. A graphic procedure in geochemical interpretation of water analyses. Am. Geophys. Union Trans. 1944, 25, 914–923. [Google Scholar]

- Stiff, H.A., Jr. The interpretation of chemical water analysis by means of patterns. J. Pet. Technol. 1951, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, L.V.; Ukhanov, A.V.; Sharaskin, L.Y. On the composition of upper mantle material. Geochemistry 1972, 10, 1155–1167. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bazylev, B.A. Petrological and Geochemical Evolution of Mantle Material in the Lithosphere: Comparative Study of Oceanic and Alpine-Type Spinel Peridotites. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Geochemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia, 26 November 2003; p. 371. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Hatari Labs. What Is a Piper Diagram for Water Chemistry Analysis and How to Create one? Available online: https://hatarilabs.com/ih-en/what-is-a-piper-diagram-and-how-to-create-one (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Barnes, I.; O’Neil, J.R. The relationship between fluids in some fresh alpinetype ultramafics and possible modern serpentinization, western United States. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1969, 80, 1947–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, C.; Stanger, G. Past And Present Serpentinisation of Ultramafic Rocks; An Example from the Semail Ophiolite Nappe of Northern Oman. In The Chemistry of Weathering. Nato ASI Series; Drever, J.I., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985; Volume 149, pp. 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, J.; Canepa, M.; Chiodini, G.; Cioni, R.; Cipolli, F.; Longinelli, A.; Marini, L.; Ottonello, G.; Zuccolini, M.V. Irreversible watererock mass transfer accompanying the generation of the neutral, Mg-HCO3 and high-pH, Ca-OH spring waters of the Genova province, Italy. Appl. Geochem. 2002, 17, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, T.; Toscani, L. Springs and streams of the Taro-Ceno Valleys (Northern Apennine, Italy): Reaction path modeling of waters interacting with serpentinized ultramafic rocks. Chem. Geol. 2008, 257, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palandri, J.L.; Reed, M.H. Geochemical models of metasomatism in ultramafic systems: Serpentinization, rodingitization, and sea floor carbonate chimney precipitation. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 2004, 68, 1115–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B.; Matter, J. In situ carbonation of peridotite for CO2 storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17295–17300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paukert, A.N.; Matter, J.M.; Kelemen, P.B.; Shock, E.L.; Havig, J.R. Reaction path modeling of enhanced in situ CO2 mineralization for carbon sequestration in the peridotite of the Samail Ophiolite, Sultanate of Oman. Chem. Geol. 2012, 330, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 2, p. 541.

- Boudibi, S. Modeling the Impact of Irrigation Water Quality on Soil Salinization in an Arid Region, Case of Biskra. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Mohamed Khider – Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SanPiN 1.2.3685–21; Hygienic Standards and Requirements for Ensuring Safety and/or Harmlessness to Humans of Environmental Factors. Chief State Sanitary Doctor of the Russian Federation, Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Well-Being (Rospotrebnadzor): Moscow, Russia, 2021; p. 1025. (In Russian)

- GOST R 54316–2020; Natural Mineral Drinking Waters. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 2020; pp. 32–33. (In Russian)

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.