Abstract

This study focuses on the scale of wind and rainfall-induced soil erosion that is relevant to transportation infrastructure. To this end, an experimental approach was devised and carried out to assess the effectiveness of lignin, a biodegradable and non-toxic plant-derived biopolymer, in enhancing soil resistance to wind and rainfall-induced erosion. The experimental program included basic soil tests required for soil classification, wind and rainfall-induced erosion tests, pocket penetrometer tests to assess the near-surface soil strength, SEM, EDS scans, and FTIR spectroscopy to evaluate changes in the fabric and chemical composition of the soil treated with lignin. Additionally, the effect of lignin on the re-establishment of the vegetative cover after the construction completion was also investigated. It was found that an increased spraying rate of lignin solution increased both the near-surface strength and wind erosion resistance. Moreover, SEM scans showed that the presence of lignin provided abundant particle coating, which is a source of additional cohesive strength. However, the spraying rate had a minor effect on rainfall erosion resistance, which increased with an increase in lignin solution concentration. Finally, lignin treatment did not significantly affect the size of the vegetative cover and had a minor effect on soil nutrients.

1. Introduction

Soil erosion is one of the geological processes that contributes to shaping the Earth’s surface through the dislodging and transporting of soil particles by the action of wind and water. While erosion studies span scales from laboratory experiments to regional and global assessments, this study focuses on the scale of erosion relevant to transportation infrastructure. The existing vegetative cover, which provides protection against erosion, is typically cleared prior to road construction, thus leading to uncontrolled erosion and necessitating the development of erosion control methods such as rapid revegetation, planting of quick-growing grasses, manual placement of harvested straw and erosion control blankets, and the use of compost on embankments [1].

Biopolymers enhance stability and soil surface erosion resistance through multiple interactions, including bio-aggregation, bio-crusting, bio-coating, bio-clogging, and bio-cementation [2]. Lignin is a complex biopolymer, the primary component of the cell walls of vascular plants, which fills the spaces between cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin components, thereby enhancing the rigidity of the cell walls and facilitating the transport of water and nutrients. Lignin is a recalcitrant biopolymer that is biodegradable at a much slower rate than cellulose. Lignin, isolated from biomass, is the second most abundant natural polymer after cellulose [3]. It can regenerate naturally via photosynthesis, resulting in approximately 50 billion tons per year [4]. It is one of the most economically advantageous materials among all available biopolymers in geotechnical engineering [5].

Lignosulfonates are obtained from lignin by sulfite pulping of wood, which separates lignin from cellulose and hemicellulose. While lignosulfonates are also by-products of biofuel industries, the paper manufacturing and wood processing industries alone are estimated to have a global annual production of 50 million tons [6]. In addition to being renewable, lignosulfonates are also non-toxic and biodegradable, at a larger rate than lignin. Thus, they are a sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic polymers, which are ideally suited for protection against wind and rainfall-induced soil erosion.

The sand stabilization potential of lignin extracted from straw pulp black liquor waste was previously investigated in a field-scale experiment [7,8]. Results showed that a lignin solution concentration of 2%, applied at a spraying rate of 2.5 L/m2, effectively stabilized fugitive sand dunes in an arid climate. Lignosulfonate was found to be effective for soil stabilization and as a dust palliative material on unpaved roads [9,10]. By conducting mercury intrusion porosimetry, it was determined that the cumulative pore volume of a soil stabilized with lignin decreased compared to untreated soil [11]. Furthermore, the lignin-based bonding materials generated in a soil matrix after curing coated and bonded the solid particles, filling the pores and resulting in effective cementation that increased erosion resistance and strength. Composites of Dubb Humic Acid (DHA) and lignin, and DHA and lignosulfonate were found effective in nearly stopping the wind erosion of a sandy soil to a maximum of 1.11% weight loss, based on the tests conducted in the 1 m long wind tunnel at a wind speed of 25.2 km/h [12].

Adding lignin to soil was found to cause a significant increase in cohesion and a slight reduction in the friction angle based on undrained triaxial tests [13]. Although cohesion gain determined based on undrained triaxial tests conducted on silt stabilized with lignin was substantial, no significant differences in soil cohesion were found between the samples treated with 1% and 3% lignin [14]. The increase in cohesion was attributed to the adhesive action of lignin. Furthermore, the lignin concentrations of 1 and 3% were not effective in decreasing the rainfall erosion. Additionally, increased unconfined compression strength (UCS) has been reported for silty sand [15], clay stabilized with lignin [16,17], and sand stabilized with lignin, as determined by direct shear tests [18].

The need for this study arose from the increased vulnerability of Kansas roadsides to erosion during the construction period and prior to the re-establishment of a protective vegetative cover. Although lignosulfonates are more biodegradable than lignin, it is expected that they would not experience significant biodegradation during the relatively short construction period. However, if needed, they can be reapplied simply by spraying the soil surface.

The novelty of this study lies in the simultaneous evaluation of the treated soil’s resistance to rainfall and wind erosion, as well as in determining the corresponding roles of lignosulfonate solution concentration and spraying rate on both processes. Additional novelties include the experimental determination of the effect of lignosulfonate configuration on the wind speed at the onset of erosion and the use of a pocket penetrometer to assess the near-surface strength of the treated soil. Finally, the effects of lignosulfonate on soil nutrients and the development and size of vegetative cover, which is crucial for future protection against erosion, were also evaluated. While it is not necessary that the presence of lignosulfonate does not affect soil nutrients, it must not adversely affect the size of the vegetative cover.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

A soil from the Kansas State University Horticultural Research and Extension Center in Olathe, Kansas, was selected for this study. Based on sieve analysis [19], it was found that 60% of particles by weight were smaller than 0.075 mm, while plastic and liquid limits [20] were found to be 24 and 32, respectively, resulting in the classification as a silt of low plasticity (ML) according to the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS).

Plastic and liquid limits were also determined on the soil treated with lignin at gravimetric lignin contents (χl) of 2, 4, and 6% whereby χl is defined as:

and Ml is the mass of lignin solids, while Ms is the mass of soil solids. The measured moisture content (w*) is defined as:

where Mw is the mass of water. A true water content w = Mw/Ms can be obtained from Equation (2) as follows:

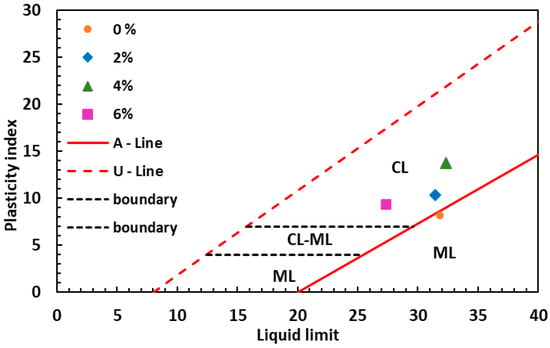

While both the plastic and liquid limits overall decreased with increased gravimetric lignin content, the plastic limit decreased at a slightly higher rate, thereby increasing the plasticity index and altering the soil classification from ML to CL, or clay of low plasticity, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Effect of gravimetric lignin content on USCS classification of the treated soil.

A neutral pH, purified calcium/sodium lignosulfonate-based product, known as Norlig G-58%, was used for near-surface stabilization in this study. It is a water-based solution that contains 58% of calcium/sodium lignosulfonate solids. The solution was further diluted in water to the concentrations used in the experiments. Chemical Abstract Service Registry Numbers (CAS RN) for calcium and sodium lignosulfonates are 8061-52-7 and 8061-51-6, respectively. For simplicity, Norlig G-58% is referred to simply as lignin from hereon.

2.2. Methods

An experimental program was devised to evaluate the effectiveness of lignin in preventing the wind and rainfall-induced erosion. It comprised laboratory pocket penetrometer tests, wind and rainfall erosion tests, and a field trial which assessed the effect of lignin’s presence on soil nutrients and the development of vegetative cover. Finally, Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), EDS (Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy) (TESCAN Mira 3, TESCAN Orsay Holdings (Brno, Czech Republic)) scans, and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) (Spectrum 400 FT-IR/FT-NIR, PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) spectroscopy were performed on treated and untreated soil samples to obtain further insight into differences in fabric, elemental composition, and to assess whether new compounds are formed when lignin is mixed with soil. Further details of the experimental program are provided below.

2.2.1. Pocket Penetrometer Tests

In the event of erosion, the near-surface soil is eroded first, and its strength is crucial for understanding the erosion processes. Pocket penetrometer tests were adopted to measure the near-surface strength as they provide direct access to this region. To simulate extreme field conditions, the soil for laboratory penetrometer tests was oven-dried, ground, and deposited from a height of 1 cm into 5.08 cm deep trays. Lignin powder was diluted in water to various concentrations, and the resulting lignin solution was applied to the soil at different rates. Near-surface unconfined compressive strength (UCS) was measured using a Gilson Soil Pocket Penetrometer HM 500 (Gilson Company, Inc., Lewis Center, OH, USA). Measurements were taken during the 24 h period following spraying. An optional adapter foot attachment, available for testing very soft soils, had an increased piston diameter of 2.54 cm, which increased the contact surface area 16 times. Lignin solution concentrations, along with the spraying rates for hand penetrometer tests, are listed in Table 1. Each test was repeated twice. The mean values of near-surface strengths along with 95% confidence intervals are presented in Section 3.1.

Table 1.

Experimental program for laboratory pocket penetrometer tests.

2.2.2. Wind Erosion Tests

The experimental configurations for wind erosion tests are presented in Table 2. For each test, the soil was oven-dried, ground, and deposited loosely to a depth of 2.54 cm and flush with the edge of the steel container using a funnel whose bottom was located approximately 1 cm above the soil surface. This method of preparation was selected to represent the conditions that are extremely susceptible to erosion. Wind erosion tests commenced four hours after spraying the soil with a lignin solution, at which time all tested configurations had reached the post-peak strength, as discussed later. The container, which measured 121.9 cm in length and 20 cm in width, was placed inside the 76.2 cm wide and 88.9 cm high wind tunnel, constructed from a PVC frame and transparent polyvinyl fabric (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Experimental program for wind erosion tests.

Figure 2.

Photo of the wind erosion test setup (anemometers not present).

Wind was generated for a total duration of 15 min by placing a fan (X-840HC-M Air mover, 1HP) in front of the 250 cm long wind tunnel. During the tests, the container end was placed 15 cm away from the fan and positioned either horizontally or inclined at an angle of 18.4° towards the horizontal direction. These two configurations are denoted by H and S, while N/A denotes non-applicable cases throughout this paper. Two anemometers were placed near the front and back ends of the container, and a third anemometer was placed at the mid-length of the container. All anemometers were placed at the soil surface level, and the reported wind speeds are the average value of the three measurements.

2.2.3. Rainfall Erosion Tests

Table 3 outlines the experimental configurations used in the rainfall erosion tests. For each test, the soil was oven-dried, ground, and loosely deposited using a funnel positioned about 1 cm above the soil surface. The soil was placed to a depth of 2.54 cm in a steel container with transparent side walls measuring 90.2 cm in length, 30.5 cm in width, and 12.7 cm in depth. Table 3 refers to horizontal and inclined (at 18.4°) positions of the container as H and S, respectively. A steel mesh was installed at one end of the container to allow soil and water to pass into an adjacent compartment measuring 12.7 cm by 30.5 cm. A plastic tube connected to this compartment enabled the collection of the runoff, which, along with the eroded soil, was oven-dried to determine both the total eroded mass and the percentage of dry soil loss.

Table 3.

Experimental program for rainfall erosion tests.

Rainfall erosion tests were conducted 6 h after the application of the lignin solution. The simulator consisted of a full-cone nozzle (50 WSQ, Spraying Systems Co., Wheaton, IL, USA) mounted on a PVC frame, positioned approximately 2.99 m above the soil surface (Figure 3). A regulated water pressure produced a uniform rainfall intensity of around 6.35 cm per hour over the soil surface. This setup replicates the configuration used in [21], where it was demonstrated that such a system closely mimics natural rainfall in terms of drop size, impact energy, intensity, and distribution. According to [22], a rainfall intensity of 6.35 cm per hour corresponds to a 10- to 25-year, one-hour storm event in various regions of Kansas. Each rainfall erosion test was conducted for a duration of one hour.

Figure 3.

Photo of the rainfall erosion test setup.

While lignin solution concentrations and spraying rates for pocket penetrometer, wind erosion, and field trial are in agreement, the concentrations and spraying rates for rainfall erosion tests are higher because it was discovered during these tests that the previously used lignin concentrations are not effective in preventing rainfall erosion. The rainfall erosion tests were performed last.

2.2.4. SEM, EDS, and FTIR Spectroscopy

Untreated and treated samples were subjected to SEM and EDS scans and FTIR spectroscopy. The TESCAN Mira 3, from TESCAN Orsay Holdings (Brno, Czech Republic), was used for SEM and EDS scans, and the Spectrum 400 FT-IR/FT-NIR Spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA) was used for FTIR. All samples were deposited from approximately 1 cm height into a can, and a 3% lignin solution was sprayed onto the surface at a rate of 5 L/m2. The samples for SEM, EDS, and FTIR spectroscopy were then taken from the surface of the sample prepared in the can. Both scans and FTIR spectroscopy were performed 24 h after spraying the soil with the lignin solution.

2.2.5. Field Trial

For the field trial assessing the effect of lignin on soil nutrients and vegetative cover, 1.52 m × 1.52 m plots shown in Figure 4 were arranged using a randomized complete block design with four replicates. Further details about lignin application for each plot type are provided in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Plot layout for field trial.

Table 4.

Details of lignin application for field trial.

A native grass mixture with wildflowers was seeded on 4 June 2021, at a rate of 50.4 kg pure live seed per hectare, in accordance with the recommendations of the Kansas Department of Transportation (KDOT). Contents of the mixture from Sharp Brothers Seed Company (Healy, KS, USA) included quickguard (22.4%), Sharps Improved Buffalo (18.8%), El Reno sideoats gram (15.9%), Barton western wheatgrass (8%), Aldous little bluestem (4.2%), Kaw big bluestem (4.2%), Cheyenne yellow indiangrass (4.1%), Illinois bundleflower (2.9%), blanket flower (2.1%), switchgrass blackwell (2.1%), Lovington blue grama (2%), pitcher sage (0.84%), purple prairie clover (0.81%), leadplant (0.76%), black-eyed susan (0.67%), butterfly milkweed (0.65%), lemon mint (0.63%), white prairie clover (0.6%), plains coreopsis (0.46%), maximilian sunflower (0.43%), western yarrow (0.42%), and prairie coneflower (0.41%). At the time of seeding, a 24-25-4 Scotts fertilizer was applied, equivalent to 50.4 kg N/ha, 54.9 kg P2O5/ha, and 37 kg K2O/ha. Lignin was sprayed over the soil the same day the seeding was performed, while irrigation was applied the following day. This was followed by application of additional irrigation as needed to keep the soil surface moist for the first few weeks after planting.

3. Results

3.1. Pocket Penetrometer Tests

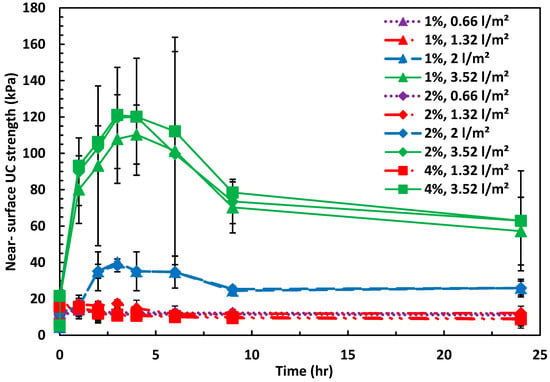

Figure 5 illustrates the development of near-surface UCS with time, obtained from pocket penetrometer tests. Data points at time zero represent the near-surface UCS of untreated soil. As shown, near-surface UC strength increases sharply immediately after lignin application, reaches a peak value, and decreases towards an early post-peak value culminating in the 24 h value. Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between UCS and spraying rate.

Figure 5.

Development of near-surface UCS with time obtained from pocket penetrometer tests. Lignin contents are provided in the legend. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

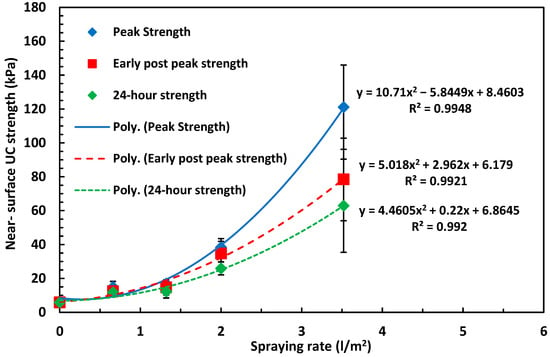

Figure 6.

Near-surface UCS from pocket penetrometer vs. lignin spraying rate. Error bars show 90% confidence intervals.

Figure 5 also shows that a spraying rate of 3.52 L/m2 consistently yields higher strengths, regardless of the lignin solution concentration. For example, there is no difference between the peak and 24 h strengths of soils sprayed with 2% and 4% lignin concentrations at a spraying rate of 3.52 L/m2. Thus, the spraying rate has a more pronounced effect on the UCS than the solution concentration. A similar finding, i.e., that lignin concentration does not significantly affect cohesive strength, was mentioned in the introductory section [14]. Based on these findings, near-surface strength data are grouped by spraying rates and shown in Figure 6. This provides a sufficient number of data points for fitting a quadratic curve, which shows a quadratic growth of near-surface strength with the spraying rate.

3.2. Wind Erosion Tests

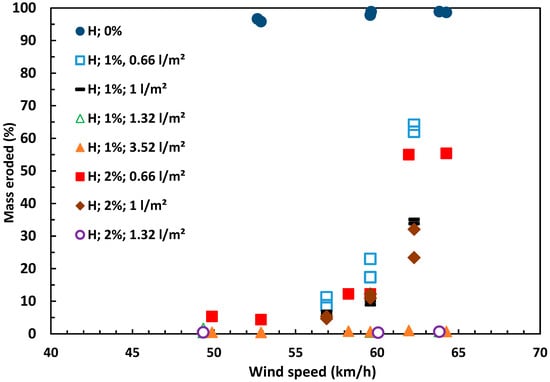

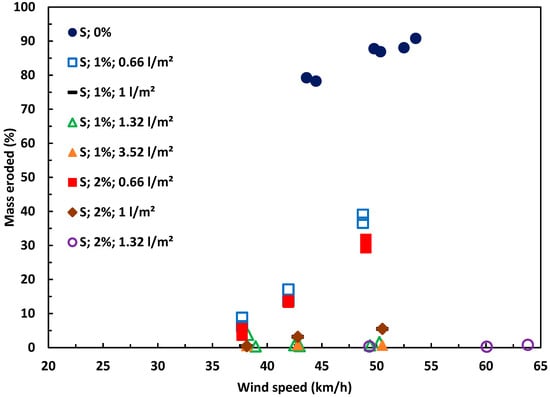

Raw experimental data showing the percentage of eroded dry soil mass versus the average wind speed for horizontal and sloped test configurations are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively.

Figure 7.

Percentage of eroded soil mass vs. wind speed for horizontal container.

Figure 8.

Percentage of eroded soil mass vs. wind speed for tilted container.

A common behavioral pattern is observed in Figure 7 and Figure 8, where wind erosion is completely prevented at a spraying rate of 1.32 L/m2 for both lignin solution concentrations, 1% and 2%. Among the selected spraying rates, the threshold for initiating erosion was a spraying rate of 1 L/m2 at a 2% solution concentration, which was closely followed by a spraying rate of 1 L/m2 at a 1% solution concentration. The next more susceptible configuration corresponds to a spraying rate of 0.66 L/m2 at a 2% concentration, closely followed by 1%, which culminates in extremely high erosion rates of the unprotected soil.

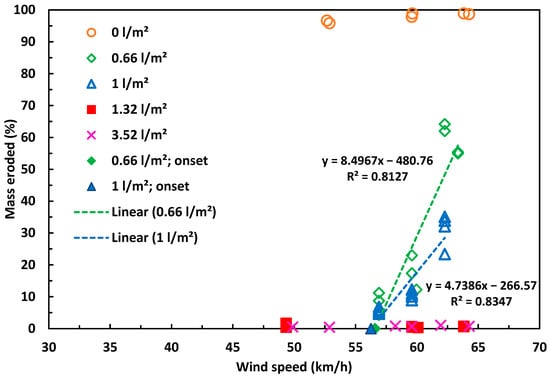

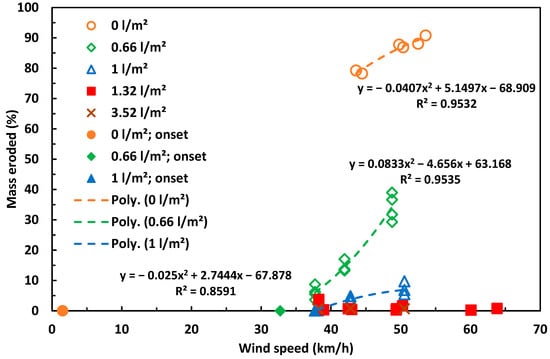

Similar to near-surface strength, wind erosion tests are grouped according to the spraying rates, as both behaviors are influenced by cohesion, which is primarily affected by the spraying rate. This has resulted in twelve data points per given spraying rate, except for the zero-spraying rate, with six data points (Figure 9 and Figure 10). The number of data points justifies the fitting of quadratic curves covering the observed range of wind speeds. These curves enable the assessment of the effect of lignin configuration on wind speed at the onset of erosion. It is noted that a significant extrapolation is not required as the measured wind speeds are in the vicinity of the estimated wind speeds at the onset of erosion, except for the configurations without lignin. In spite of that, the extrapolation of the fitted curve to zero eroded solids for the sloped configuration gives a wind speed of 1.52 km/h. This is a reasonable estimate because the erosion amounts of the unprotected soil range from 79.2% at a wind speed of 27.1 km/h for the sloped soil configuration to 98.6% at 64.2 km/h for the horizontal soil configuration. Thus, the onset of erosion of unprotected soil at 1.52 km/h, or as soon as there is any wind, is reasonable, especially since the soil was oven-dried, ground, and loosely deposited in the container.

Figure 9.

Percentage of eroded mass vs. wind speed for horizontal container. Experimental data are grouped by spraying rate.

Figure 10.

Percentage of eroded soil mass vs. wind speed for tilted container. Experimental data are grouped by spraying rate.

In the case of a horizontally positioned container, the wind speed at the onset of erosion is approximately 56.4 km/h for spraying rates of 0.66 and 1 L/m2. For spraying rates 1.32 and 3.52 L/m2, virtually no erosion was observed in the range of the employed wind speeds. In the case of a tilted container, the onset of erosion occurred at wind speeds of 32.7 and 38.1 km/h for spraying rates of 0.66 and 1 L/m2, respectively. Virtually no erosion was observed at higher spraying rates of 1.32 and 3.52 L/m2 within the employed range of wind speeds.

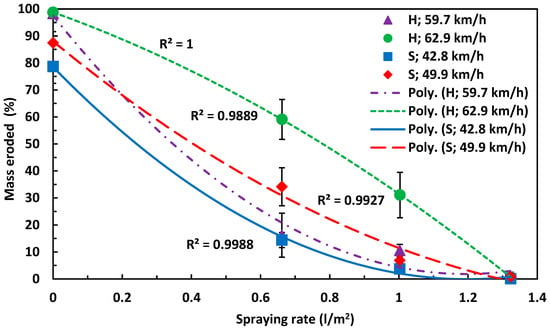

Next, the percent of eroded soil mass is plotted against the spraying rate for selected constant wind speeds (Figure 11). The data are grouped by spraying rates. Overall, the mass eroded shows a quadratic decay with increasing spraying rate.

Figure 11.

Mass of eroded soil vs. spraying rate for selected wind speeds. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

3.3. Rainfall Erosion Tests

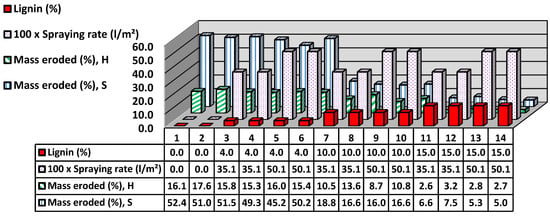

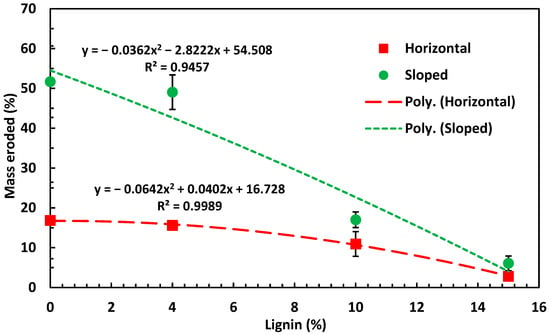

Results of all rainfall erosion tests are summarized in Figure 12 and Figure 13. The spraying rates are magnified ten times in Figure 12 for clarity, while experimental data are grouped by spraying rate in Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Summary of all rainfall erosion tests.

Figure 13.

Eroded soil mass vs. lignin solution concentration for rainfall erosion. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals.

It is observed that, unlike in the case of wind erosion, lignin solution concentration is the primary factor controlling the amount of erosion for both horizontal and sloping soil configurations, with larger amounts of erosion observed in the latter case (Figure 11). Both figures indicate that a 10% lignin solution concentration was necessary to observe a noticeable decrease in erosion, which was more pronounced for the sloping configuration. A further decrease in erosion was achieved by increasing the lignin concentration to 15%.

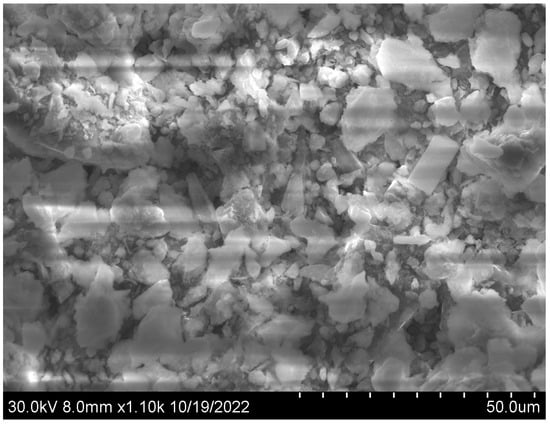

3.4. SEM, EDS, and FTIR Spectroscopy Results

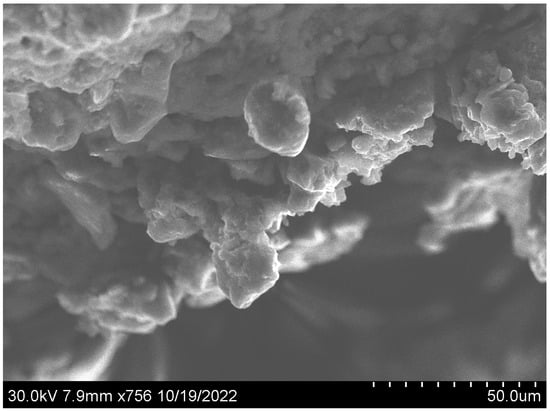

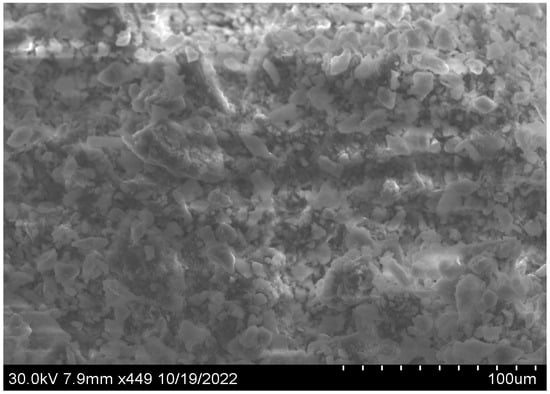

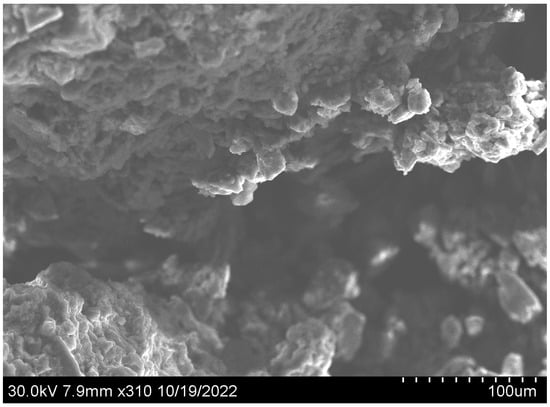

SEM and EDS scans of treated and untreated soils are presented in Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18. In SEM scans of untreated soil (Figure 14 and Figure 16), the edges of soil particles are clearly discernible, while that is not the case in SEM scans of treated soil (Figure 15 and Figure 17). Clearly, the addition of lignin fills the pores and provides a thick, abundant coating of particles.

Figure 14.

SEM scan of untreated soil, scale bar 50 μm.

Figure 15.

SEM scan of treated soil, scale bar 50 μm.

Figure 16.

SEM scan of untreated soil, scale bar 100 μm.

Figure 17.

SEM scan of treated soil, scale bar 100 μm.

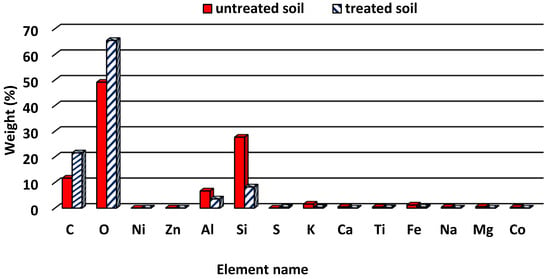

Figure 18.

EDS of untreated and treated soil, scale bar 100 μm.

A comparison of EDS scans of treated and untreated soil indicates that the presence of lignin increases the amounts of carbon and oxygen (Figure 18), which are the most abundant elements in lignosulfonate. The increase is compensated for by decreased amounts of silicon and aluminum.

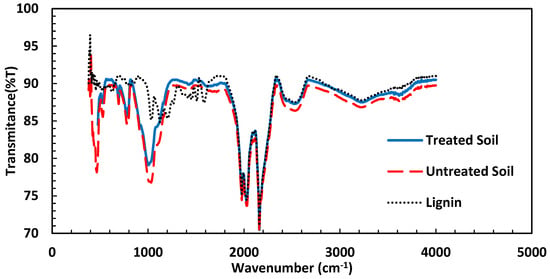

Finally, FTIR spectroscopy results (Figure 19) show that no new peaks are observed in the soil treated with lignin compared to the soil and lignin alone, indicating that no new compounds are formed. Thus, the strength gain mechanism is due to adhesion between lignin and soil, which is effective as long as the treated soil remains dry.

Figure 19.

FTIR spectroscopy of soil, lignin, and soil treated with lignin.

3.5. Results of Field Trial

Table 5 presents the measured vegetative cover, along with concentrations of iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn), with all values representing the average of four separate measurements. The counts of monocots and dicots, as well as the corresponding vegetative cover, indicate that lignin application did not significantly influence these parameters. Soil analysis revealed that plots treated with 1% lignin had reduced zinc (Zn) levels, while those treated with 2% lignin exhibited lower concentrations of both iron (Fe) and zinc compared to untreated plots. However, no statistically significant differences in Fe and Zn levels were observed between untreated soil and soil treated with 4% lignin. The grass was seeded in June 2021, and a pre-emergence herbicide was applied uniformly across all plots in early spring 2022 to control annual grassy weeds, resulting in the consistent presence of grasses and broadleaf plants throughout the study area. The vegetative cover counts were conducted in late 2022 and were not affected by the herbicide. According to Table 5, means followed by the same letter are not significantly different based on Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test (p < 0.05). The mean value of the percent of vegetative green cover for treated plots is 34.5%, which is slightly larger than 33% for untreated plots.

Table 5.

Vegetative cover and amount of soil nutrients from the field trial.

4. Discussion

The experimental program was initially designed to investigate lignin concentrations in the range of 1 to 4% and spraying rates in the range of 0.66 to 3.52 L/m2. Pocket penetrometer and wind erosion tests were simpler than the rainfall erosion tests, and thus, they were completed first. Once the rainfall erosion tests began, it became clear that the planned lignin concentrations were ineffective in significantly reducing or stopping the erosion. As a last resort, lignin concentrations were increased beyond the planned values, and the rainfall erosion was nearly stopped.

Since the lignin spraying rate was found to be the primary factor influencing the near-surface strength gain, the spraying rate also played a crucial role in reducing wind erosion. These two groups of experiments employed the same range of lignin configurations and spraying rates, except that the wind erosion experiments did not use high lignin concentrations, as erosion had already stopped at lower concentrations.

Largely different lignin configurations for rainfall tests did not adversely affect the results because the mechanisms of resistance of soil treated by lignin, i.e., calcium/sodium lignosulfonate, to wind and rainfall erosion are different. Specifically, the near-surface strength that controls wind erosion is irrelevant for rainfall erosion. This is due to calcium/sodium lignosulfonate being soluble in water. Thus, adhesion between the soil and lignin is destroyed during the rainfall, and the strength degrades rapidly. The primary mechanism of resistance to rainfall erosion appears to be the increased viscosity of the pore fluid, which is achieved at high lignin concentrations, thereby slowing down the rate of rainfall erosion. For example, a 58% lignin solution has a dynamic viscosity of 300 mPa-s at 25 °C, compared to the water’s viscosity of only 0.89 mPa-s at the same temperature. As lignin concentration increases, the viscosity of the pore fluid rises, resulting in decreased hydraulic conductivity, thus offering resistance to rainfall erosion. In contrast, during wind erosion events where the soil remains dry, pore fluid viscosity is irrelevant, which explains why lignin concentration has little effect on wind erosion.

A full assessment of near-surface strength increase, followed by a decrease over time, would require a separate investigation. The oven-dried soil was sprayed with a water solution of lignin, which likely initially generated suction, thereby increasing the near-surface strength. However, over time, the solution dried out and solidified, likely resulting in a loss of suction and a reduction in strength. At no point during the 24 h period after spraying did the strength decrease to a value smaller than that of the untreated soil.

Although wind speeds for horizontal and sloping configurations differed, the wind erosion data could still be used to determine the effect of lignin configurations on the onset of wind erosion. Some lignin configurations, as explained earlier, provided full protection against erosion for the tested range of wind speeds. The experimental procedure would most probably have been very similar if a wind tunnel with a controlled wind speed had been available. For example, the wind speed in the wind tunnel was increased until erosion was initiated in the study of compost-treated soil [23].

Lignin configurations for SEM, EDS, and FTIR spectroscopy bridged the gap in configurations used in wind and rainfall erosion tests. The effect of lignin on Zn and Fe levels appears to be erratic. This may have been affected by the sampling procedure. However, the amount of vegetative cover was not affected by the presence of lignin, which ensures the future establishment of vegetation.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effectiveness of calcium/sodium lignosulfonate, referred to as lignin herein, in protecting silty soil from wind and rainfall erosion. Pocket penetrometer tests were performed to assess the gain in the near-surface strength for different lignin configurations. Additionally, laboratory-scale wind and rainfall erosion tests were conducted on horizontal and sloping (18.44°) soil configurations. To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of increased erosion resistance and near-surface strength, SEM and EDS scans, and FTIR spectroscopy were conducted on treated and untreated soils. Finally, a field trial with a randomized complete block design was conducted to assess the effect of lignin on the size of vegetative cover and the composition of soil nutrients. The findings are summarized below:

(1) Near-surface strength measured by the pocket penetrometer increased immediately and reached a peak value shortly after the lignin application. This was followed by a decrease to the post-peak value, which remained nearly constant up to 24 h after spraying. All near-surface strengths, including peak, early post-peak, and 24 h strength, were larger than the near-surface strength of untreated soil.

(2) The spraying rate of lignin solution was the primary factor affecting the near-surface strength. The larger the spraying rate, the more efficient pore filling and particle coating develop.

(3) The primary factor affecting wind erosion was the spraying rate. The onset of wind erosion occurred at wind speeds of 32.7 and 38.1 km/h for spraying rates of 0.66 and 1 L/m2, respectively, and a sloped soil configuration. These wind speeds correspond to 6 Beaufort, i.e., a strong breeze that produces large sea waves and motion of large branches on land. In the case of horizontal configuration, the onset of wind erosion occurred at 56.7 km/h, essentially for both spraying rates, 0.66 and 1 L/m2. This wind speed corresponds to 7 Beaufort, i.e., a moderate gale, a near gale that heaps up the sea and puts whole trees in motion on land. Lignin application stopped erosion at spraying rates of 1.32 L/m2 and higher, regardless of the lignin concentration within the tested wind speed range.

(4) A comparison of SEM scans of treated and untreated soil shows abundant particle coating that generated adhesion between soil and lignin, and it is the main source of increased near-surface strength.

(5) A comparison of EDS scans of treated and untreated soils shows an increase in amounts of carbon and oxygen, which are abundant in lignin. The increase is compensated for by a decrease in silicon and aluminum.

(6) FTIR spectroscopy shows that no new compounds have formed due to adding lignin to soil, thus once again confirming that the main mechanism of strength gain is adhesion between lignin and soil.

(7) The primary factor governing rainfall erosion is lignin concentration. A large increase in concentration to 15% was required to nearly stop the rainfall erosion. As lignin dissolves in water, the increased viscosity of pore fluid due to the presence of lignin solids is likely a mechanism that decreases rainfall erosion.

(8) The field trial revealed no significant impact of lignin on the amount of vegetative cover, though iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) levels were lower at 1% and 2% lignin concentrations, but not at 4%.

In summary, spraying of lignin solutions over the soil surface provides an excellent protection against wind erosion, especially in dry climates. This finding aligns with previous larger-scale experiments [7,8] that demonstrated the application of lignin provided protection against wind erosion in the sand dune area and facilitated the establishment of arenaceous plants. Furthermore, lignin can also provide very good resistance against rainfall erosion when applied at high solution concentrations. The decision about the lignin configurations to be employed for erosion prevention would also depend on the relevant climate, particularly the amount of rainfall.

Finally, the experimental program in this study was designed to capture the main features of wind and rainfall-induced erosion of lignin-enhanced silty soil. Future studies should generate larger databases, based on which wider and deeper insights can be gained.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P. and J.F.; methodology, D.P., A.O., J.F. and J.Y.; investigation, D.P., A.O., J.F. and J.Y.; formal analysis: D.P. and J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P., J.F. and C.D.B.A.; writing—review and editing: D.P. and C.D.B.A., supervision: D.P.; project administration, D.P.; funding acquisition, D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Kansas Department of Transportation through KTRAN program. The contract number is KSU 20-2.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request, as the Kansas Department of Transportation has not yet published the final project report.

Acknowledgments

The first three authors acknowledge the funding provided by the Kansas Department of Transportation that made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Arash Olia was employed by the company Kiewit Engineering. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Barkley, T. Erosion Control with Recycled Materials. In Public Roads; Superintendent of Documents: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, I.; Lee, M.; Tran, A.T.P.; Lee, S.; Kwon, Y.-M.; Im, J.; Cho, G.-C. Review on Biopolymer-Based Soil Treatment (BPST) Technology in Geotechnical Engineering Practices. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 24, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganewatta, M.S.; Lokupitiya, H.N.; Tang, C. Lignin Biopolymers in the Age of Controlled Polymerization. Polymers 2019, 11, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Jin, W.; Hu, J.; Xiao, R.; Luo, K. An Overview on Fast Pyrolysis of the Main Constituents in Lignocellulosic Biomass to Valued-Added Chemicals: Structures, Pathways and Interactions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cai, G.; Liu, S. Application of Lignin-Stabilized Silty Soil in Highway Subgrade: A Macroscale Laboratory Study. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsha, B.; Moghal, A.A.B.; Rehman, A.U.; Chittoori, B.C.S. Shear, Consolidation Characteristics and Carbon Footprint Analysis of Clayey Soil Blended with Calcium Lignosulphonate and Granite Sand for Earthen Dam Application. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Li, J.; Lu, X.-Z.; Jin, Y.-C. A Field Experimental Study of Lignin Sand Stabilizing Material (LSSM) Extracted from Spent-Liquor of Straw Pulping Paper Mills. J. Environ. Sci. 2005, 17, 650–654. [Google Scholar]

- Hanjie, W.; Frits, P.d.V.; Yongcan, J. A Win-Win Technique of Stabilizing Sand Dune and Purifying Paper Mill Black-Liquor. J. Environ. Sci. 2009, 21, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surdahl, R.; Woll, J.H.; Marquez, R. Road Stabilizer Product Performance: Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Woll, J.H.; Sundahl, R.W.; Everett, R.; Andreson, R. Road Stabilizer Product Performance. Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge; Central Federal Lands Highway Division, U.S. Department of Transportation: Lakewood, CO, USA; Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge: Green River, WY, USA, 2008.

- Zhang, T.; Cai, G.; Liu, S.; Puppala, A.J. Engineering Properties and Microstructural Characteristics of Foundation Silt Stabilized by Lignin-Based Industrial by-Product. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 2725–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoosefat, O.; Shariatinia, Z.; Mair, F.S.; Paghaleh, A.S. Efficient soil Stabilizers Against Wind Erosion Based on Lignin and Lignosulfonate Composites of Dubb Humic Acid as a Value-Added Material Extracted from a Natural Waste. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, P.; Gratchev, I.; Son, S.; Rybachuk, M. Durability, Strength, and Erosion Resistance Assessment of Lignin Biopolymer Treated Soil. Polymers 2023, 15, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, P.; Gratchev, I.; Zolghadr, M.; Son, S.; Kim, J.M. Mitigation of Soil Erosion and Enhancement of Slope Stability D through the Utilization of Lignin Biopolymer. Polymers 2024, 16, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoni, R.L.; Tingle, J.S.; Webster, S.L. Stabilization of Silty Sand with Nontraditional Additives. Transp. Res. Rec. 2002, 1787, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingle, J.S.; Santoni, R.L. Stabilization of Clay Soils with Nontraditional Additives. Transp. Res. Rec. 2003, 1819, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, H.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Kim, S. Soil Stabilization with Bioenergy Coproduct. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2186, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, D.; Bartley, P.A.; Davis, L.; Uzer, A.U.; Gürer, C. Assessment of Sand Stabilization Potential of a Plant-Derived Biomass. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2016, 23, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D422-63(2007); Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Analysis of Soils. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d0422-63r07.html (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- ASTM D4318-17e1; Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://store.astm.org/d4318-17e01.html (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Humphry, J.B.; Daniel, T.C.; Edwards, D.R.; Sharpley, A.N. A Portable Rainfall Simulator for Plot-Scale Runoff Studies. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2002, 18, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershfield, D.M. Rainfall Frequency Atlas of the United States for Durations from 30 Minutes to 24 Hours and Return Periods from I to 100 Years; Weather Bureau, U.S.: Silver Spring, MD, USA; Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 1961.

- Xiao, M.; Reddi, L.N.; Howard, J. Erosion Control on Roadside Embankment Using Compost. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2010, 26, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.