Abstract

Detrital zircon U–Pb dating from the Muti Formation sheds light on sediment sources and foreland basin development along the northeastern Arabian margin during the Late Cretaceous. The siliciclastic-rich Muti Formation was deposited in a syn-obduction foreland basin that formed as the Semail Ophiolite advanced. Zircon age spectra from eastern (Nakhal and Sayga) and western (Murri) sections are dominated by Neoproterozoic–Cambrian ages (450–900 Ma), linked to the Pan-African orogeny and the Arabian–Nubian Shield, indicating these as the main sediment sources. The Murri section also contains older Mesoproterozoic to Archean zircons, likely recycled from the Nafun Group (part of the Huqf Supergroup), suggesting reworking of ancient Gondwanan cover sequences rather than direct input from the Indian craton. Additional Permian zircons reflect input from Arabian Plate magmatic rocks, while Jurassic–Cretaceous grains indicate material derived from the Semail Ophiolite and related arc terranes. Overall, the Muti Formation records a mixed sediment supply from the Arabian Shield, reworked Gondwanan sandstones, and ophiolitic detritus, marking the transition from a passive margin to a flexural foreland basin. The dominance of Pan-African zircon ages highlights continued recycling of Gondwanan sequences and refines models of Late Cretaceous basin evolution in northern Oman, underscoring the complex, multi-cycle nature of sedimentation in this tectonically active setting.

1. Introduction

Provenance studies play a crucial role in understanding the origin and evolution of sediments by identifying the petrographic and mineralogical characteristics that reflect different tectonic settings of the source areas. These studies not only reveal how sediments are produced and transported but also help predict spatial and temporal variations in sediment composition. Traditionally, provenance analysis has relied on the examination of mineralogy, texture, and composition through petrographic observations [1,2,3]. Such approaches provide valuable information about sediment source regions, dispersal pathways, tectonic environments, and depositional settings, ultimately improving our understanding of basin dynamics, paleogeographic reconstruction, and tectonic evolution.

Over the past three decades, detrital zircon U–Pb geochronology has emerged as a powerful tool for provenance research, offering an effective means of decoding the geological history preserved within sediments [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Zircon, being a chemically stable and mechanically robust mineral, is highly resistant to weathering and metamorphic alteration, making it a reliable chronometer for recording the age and evolution of source rocks [15,16,17,18,19]. Zircon occurs only sparsely in silica-undersaturated and many mafic to ultramafic rocks, which means that sediments derived from these sources can be poorly represented or even completely missing in detrital zircon datasets [20]. Moreover, while zircon’s exceptional physical and chemical toughness is often an advantage, it also makes the mineral prone to multiple episodes of sedimentary recycling [21]. Consequently, zircon grains may record several cycles of erosion, transport, and redeposition, weakening the direct connection to their most recent source rocks. This repeated recycling can cause zircon from older, zircon-rich terranes to be disproportionately represented, thereby complicating provenance interpretations by making it difficult to distinguish primary from recycled sediment sources [20,21]. Detrital zircons extracted from sedimentary rocks yield a spectrum of U–Pb ages that serve as chronological fingerprints of the contributing source terrains.

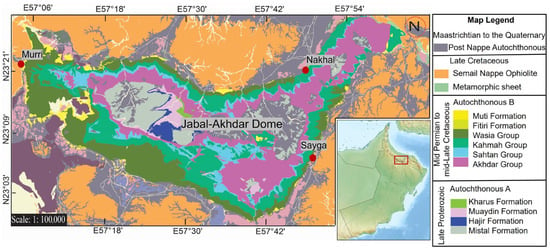

The Oman Foreland Basin, located along the southeastern margin of the Arabian Plate, offers an exceptional natural setting for provenance research in a marine foreland basin environment (Figure 1). The sedimentary succession of the basin, which includes deposits ranging from coarse-grained alluvial sediments to fine-grained marine facies, reflects the combined influence of tectonics, sea-level fluctuations, and climatic conditions [22,23]. Previous studies of the Oman Foreland Basin have emphasized the role of tectonic loading and flexural subsidence in driving the onset of foreland sedimentation [22,23,24,25,26,27]; however, the provenance of these earliest sediments has received little attention. These studies generally assumed that the sediment supply was derived from the obducted allochthon during the unroofing event, as well as from the peripheral bulge. Investigating the sediment provenance within this basin provides insights into the processes of erosion, transport, and deposition during major tectonic events, including the closure of the Tethys Ocean, ophiolite obduction, and subsequent uplift. Moreover, provenance data help to constrain the relative contributions from various source regions, such as the Arabian Shield, the Semail Ophiolite, and recycled materials derived from older stratigraphic units. The stratigraphic succession of the Oman Foreland Basin comprises the Aruma Group, a syn- to post-obduction sequence subdivided into the Muti, Fiqa, Qahlah, and Simsima formations [22,28,29,30].

Figure 1.

Geological map of the Jabal Akhdar Dome showing major geological formations and locations of the studied sections marked with a red-filled circle. The inset shows the geographic location of the northern Oman Mountains and Jabal Akhdar Dome (after [29]).

The Muti Formation represents the oldest foreland basin deposits, occurring in the proximal basin areas and gradually transitioning laterally into the Fiqa Formation toward the distal southwestern regions [22,31]. This study focuses on the Muti Formation, employing detrital zircon U–Pb geochronology to interpret sediment provenance. As the first detrital zircon-based provenance investigation within the Oman Foreland Basin, it aims to provide new insights into the provenance patterns and tectonic evolution of the basin during the Late Cretaceous. Fieldwork was conducted in the Jabal Akhdar Dome (Figure 1), with samples collected from the eastern sections at Nakhal and Sayga and from the western section at Murri (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

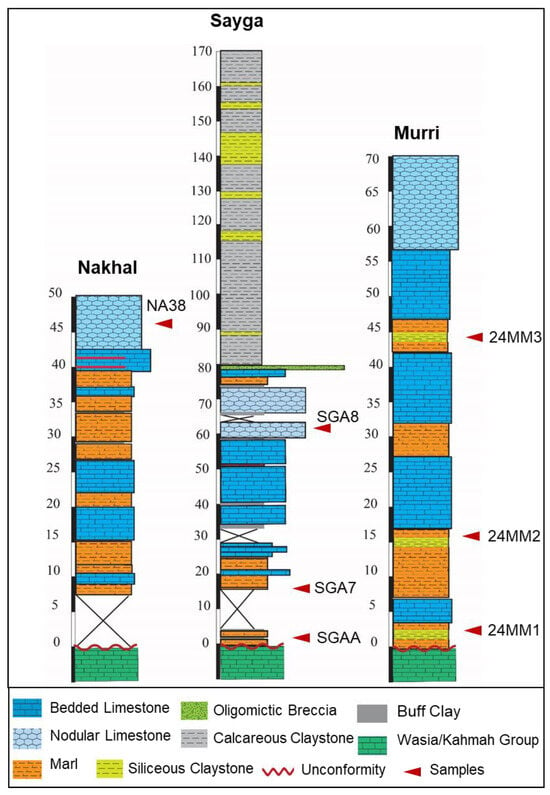

Figure 2.

Measured stratigraphic log of the Muti Formation at Nakal, Sayga, and Murri sections. Stratigraphic locations of the samples are marked on the logs.

2. Regional Setting

The Oman foreland basin developed as a flexural response to the tectonic loading of the Semail ophiolite and Hawasina Nappe onto the Arabian continental margin during the Late Cretaceous [28,32,33]. The allochthon obduction is referred to as the Alpine-I deformation [34]. The Oman foreland basin is situated in the eastern part of the Arabian Peninsula, extending from northern Oman into the United Arab Emirates, aligned parallel to the Oman Mountains, forming a north–south trending depression [35] (Figure 1). The Oman foreland basin serves as a key site for understanding the interplay between ophiolite obduction, plate flexure, and sedimentary processes in foreland settings [36,37]. The foreland basin received sediments both from the riding allochthon and the cratonic hinterland. The basin’s evolution reflects a transition from passive margin subsidence during the Neo-Tethys opening to active tectonic loading during ophiolite obduction. The basin is bordered to the south and west by the stable Arabian craton, composed primarily of Precambrian crystalline basement and Paleozoic–Mesozoic sedimentary cover [38,39]. To the north and east, the Saih Hatat and Jabal Akhdar domes expose high-grade metamorphic and lower-grade platformal sequences, respectively, both uplifted during ophiolite obduction and subsequent tectonic exhumation [38]. The Semail Ophiolite itself represents an obducted slice of Neo-Tethyan oceanic lithosphere, structurally overlying the passive-margin carbonate platform and forming a major topographic and structural high during basin development [32].

The basin hosts a thick sequence of mixed siliciclastic and carbonate sediments of Late Cretaceous to Paleogene age [40]. The earliest sediments deposited in the foreland basin belong to the Late Cretaceous Muti Formation of the Aruma Group [22,28,35], which is unconformably overlying the carbonate sequence of the Wasia Group. This unconformable contact is referred to as the Wasia–Aruma break [29,41]. The Wasia–Aruma break in the western part of the basin, such as in the Lekhwair area, marks the peripheral bulge of the foreland basin. The Aruma Group, a significant part of the basin’s stratigraphy, reflects the transition from compressional tectonics to post-obduction sedimentation. The Aruma Group in the Oman Mountains comprises an early syn-obduction mixed carbonate and siliciclastic sequence of the Muti Formation and its lateral equivalent, Fiqa Formation, representing deep to shallow marine environments. A post-obduction sequence of predominantly clastic Qahlah Formation and mainly carbonate Simsima Formation was deposited during the initial uplift of the allochthon and its subsequent subsidence and sea-level rise during the Maastrichtian [30,42,43,44,45,46]. Following obduction, shallow marine carbonate deposition dominated, with interruptions linked to regional tectonics such as the Arabian-Eurasian plate collision in the Miocene. The Aruma Group in the Oman Mountains is unconformably overlain by the shallow marine carbonate sediments of the Umm er Radhuma Group, comprising Jafnayn, Rusyal, and Seeb formations [42]. In the Miocene, during Alpine-II deformation, renewed tectonic activity associated with the Zagros orogeny led to additional flexural adjustments, cessation of basin sedimentation, and uplift of the Oman Mountains [34,47,48,49,50].

3. The Muti Formation

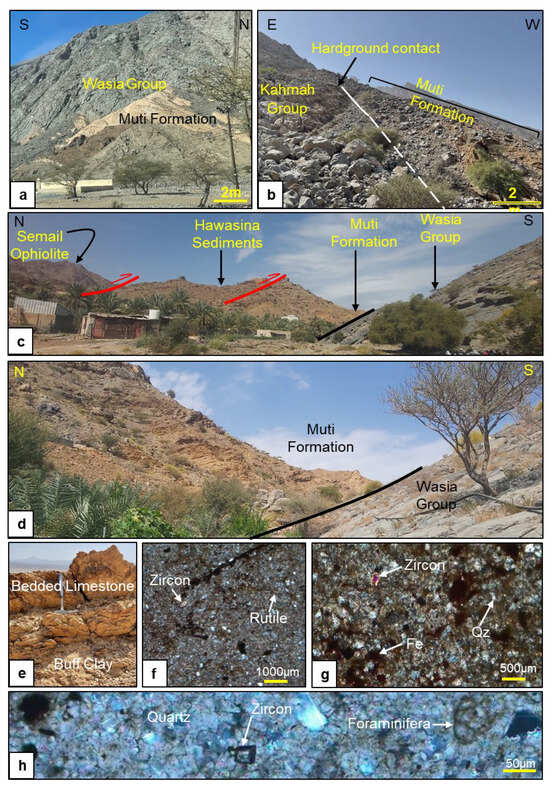

The Muti Formation is extensively exposed across the Oman Mountains, particularly within the Jabal Akhdar Dome (Figure 1). In the study area, the formation comprises a mixed carbonate–siliciclastic succession. A prominent basal hardground, characterized by encrustations and iron-rich nodules, delineates the unconformable contact between the Muti Formation and the underlying Natih Formation or the Kahmah Group rocks (Figure 3a–d). The formation exhibits a distinct vertical lithological transition, with carbonate sediments dominating the lower parts and siliciclastic deposits prevailing upward. Carbonate facies are more abundant in the northern and northeastern regions compared to the southern areas.

Figure 3.

(a–d) Field photographs of the Muti Formation showing contact relationship with the underlying Wasia/Kahmah groups. Photograph (a) is taken at the Sayga section, photographs (b,e) at the Nakhal section, and photographs (c,d) at the Murri section. (e) Field photograph showing buff clays and bedded limestone of the Muti Formation. (f–h) Photomicrographs showing the presence of zircon, rutile, and quartz in the samples of the Muti Formation. Red bold line shows the thrust faults and White solid line shows confirm contact, while dashed white line shows inferred contact.

The examined sections are situated within the Nakhal, Sayga, and Murri areas, corresponding to the northeastern, southeastern, and western sectors of the Jabal Akhdar region, respectively (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In the Nakhal area, the Muti Formation attains a thickness of approximately 50 m and consists mainly of limestone, marl, and calcareous clay. In the Sayga area, the formation is about 170 m thick, comprising limestone in the lower interval and calcareous clay in the upper part (Figure 2). In the Murri area, the formation reaches a thickness of around 70 m, consisting predominantly of calcareous clay and marl in the lower interval, with subordinate siliceous claystone, and becoming dominantly limestone toward the top (Figure 2).

Several lithofacies were identified within the Muti Formation, including bedded limestone, marl, nodular limestone, conglomerate, arenaceous claystone, calcareous claystone, and siliceous claystone. The bedded limestone lithofacies is compact and buff to gray in color, interbedded with marl and clay layers (Figure 2). It was deposited in a moderate-energy, warm-water setting and is fossiliferous, containing ammonites, brachiopods, bryozoans, bivalves, gastropods, crinoids, foraminifera, and fossil fragments. Subangular to angular millimeter-sized black chert clasts, iron-rich concretions, oxidation surfaces, and calcite veins are also common. The marl lithofacies is buff-colored, moderately to well compacted, and locally arenaceous. It is laminated to thin-bedded and occurs in all three sections (Figure 3a–e). The lithofacies contains very fine-grained white and black carbonate clasts and fossil fragments. The nodular limestone lithofacies constitutes a major portion of the formation, consisting of gray carbonate nodules set in a buff-colored carbonate matrix. The nodules are predominantly oriented parallel to the bedding planes, exhibiting smooth contacts and lacking any signs of internal grading. These textural and structural characteristics indicate an in situ origin, most likely resulting from differential compaction processes associated with the presence of thin clay interlayers within the limestone succession. In the Sayga section, the conglomerate lithofacies attains a thickness of approximately one meter. It is clast-supported, moderately sorted, and primarily composed of black chert clasts ranging in diameter from 0.4 to 4 cm.

The calcareous claystone lithofacies displays a buff coloration and is distinctly laminated, with frequent interbeds of softer buff clay. The uppermost portion of this unit is characterized by a green, fissile nature, readily splitting into thin plates parallel to the bedding planes, and presenting sharply defined surfaces. The siliceous claystone lithofacies occurs within the Sayga section as slumped beds; it is fine-grained and exhibits a color variation from dark red to buff, reflecting subtle differences in depositional and diagenetic conditions.

The sandstone facies is moderately sorted and dominated by subrounded quartz grains. The majority of the quartz is monocrystalline, with only a minor contribution from polycrystalline varieties. Grain contacts are predominantly concave–convex to tangential. Micritic mud occurs in minor amounts, occupying intergranular pore spaces. Accessory components include zircon grains with square to elongate morphologies, as well as rare chert, mica, and shell fragments.

4. Petrographic Analysis

The samples studied were mainly collected from three sections located in the eastern and western parts of the Jabal Akhdar Dome. Four samples, NA-38, SGAA, SGA7, and SGA8, represented the Muti Formation exposed in the eastern part of the Jabal Akhdar Dome. The sample NA38 represents the Nakhal section, while the other three represent the Sayga section. Similarly, three samples from the western part of the Jabal Akhdar Dome represent the Muti Formation exposed in the Murri section. These three samples were labeled as 24MM1, 24MM2, and 24MM3. Standard thin sections were prepared at the rock cutting and thin section lab of the Department of Earth Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman. These thin sections were studied using transmitted light microscopy. Selection of the samples for U–Pb geochronology was based on the relative abundance of zircon grains identified during thin-section analysis using both transmitted light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Figure 3f–h). Petrographic observations indicate that these samples correspond to arenaceous bioclastic packstone, red clay arenaceous packstone, and mudstone microfacies.

The arenaceous bioclastic packstone microfacies is characterized by moderate compaction and sorting, with a predominantly grain-supported texture. The mineralogical composition consists of approximately 5% bioclasts, 20% clastic fragments, 5% authigenic iron-rich nodules, 3% iron-bearing mineral grains, and 2% carbonate fragments, with trace amounts of accessory minerals such as zircon (Table 1 and Table 2). The clastic component is dominated by quartz, accompanied by minor iron-rich and carbonate fragments. Accessory phases, including zircon, rutile, feldspar, and mica, occur in very low abundances. Quartz grains, which range from fine to medium sand size, exhibit angular to subangular morphologies and are randomly distributed throughout the matrix. In certain instances, quartz grains infill bioclastic burrow structures. Skeletal grains include crinoid arms, brachiopod shells, ostracods, bivalve shells, echinoid spines, uniserial foraminifera, large bryozoan fragments, and undefined crystalline bioclasts.

Table 1.

Microfacies summary of zircon-bearing samples in the Muti Formation in Nakhal, Sayga, and Murri sections.

Table 2.

A summary of the framework composition of zircon-bearing samples in Nakhal, Sayga, and Murri sections (tr-traces).

The arenaceous packstone microfacies displays a matrix-supported fabric with moderate compaction. It contains a notable proportion of quartz grains, comprising roughly 20% of the total composition. These grains are irregularly distributed within a micritic mud matrix and show size variations from very fine to medium silt. In terms of morphology, the quartz grains range from angular to subrounded in shape. Additionally, well-rounded iron-bearing mineral grains (3%) are present, along with trace amounts of mica, zircon, carbonate fragments, and organic matter. Bioclasts in this microfacies include planktonic foraminifera such as Globigerina and biserial forms, as well as echinoid spines and undefined fragments.

The mudstone microfacies is homogeneous, containing less than 10% grains. Quartz grains, ranging from medium to coarse silt size, make up approximately 5% of the composition, while peloids account for about 3%. Trace amounts of well-rounded iron oxide grains, zircon, chert, and authigenic iron oxides contribute roughly 1%. Bioclasts, comprising about 1% of the microfacies, include calcispheres, foraminifera, bivalve shells, and undefined bioclastic fragments.

5. Detrital Zircon U–Pb Geochronology

5.1. Sampling and Methods

Samples were collected from the Muti Formation, a unit widely regarded as representing a syn-obduction sequence, at three well-exposed stratigraphic sections in the Nakhal, Sayga, and Murri areas within the Jabal Akhdar Dome (Figure 2 and Figure 3a–e). A total of seven samples were analyzed from the studied sections (Figure 2 and Figure 3a–e). The samples were collected from arenaceous marl, limestone, and calystone/siltstone. In order to separate the detrital zircon grains, the samples with a weight of about 5–10 kg were crushed and further processed using heavy liquids and magnetic separation techniques. These grains were placed in epoxy resin, and then the surface of the grains was polished to make them smooth. Prior to the in situ laser U–Pb analyses, the sample surfaces were cleaned using a mixture of diluted nitric acid (HNO3) and pure ethanol to remove any potential lead contamination. Detrital zircon U–Pb analyses were conducted at the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, employing a laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA–ICP–MS) system. The analytical setup comprised a NewWave UP 193 nm ArF excimer laser coupled to an Agilent 7500a quadrupole ICP–MS. Cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging was performed on the zircon grains prior to analysis (Figure S1) to characterize their internal structures and assist in selecting an appropriate analytical spot. This approach enabled the selection of analytical spots on the outermost rims of zircons exhibiting complex core–rim structures. Additionally, several crystals displayed oscillatory zoning, a characteristic feature indicative of magmatic origin.

In this particular investigation, the zircon grains were subjected to ablation using a spot size of 35 μm and a repetition rate of 8 Hz. During the course of the analyses, the energy being utilized was around 8–10 J/cm2. The laser ablation pits had a depth of approximately 15–20 μm. Each analysis lasted for a total of one hundred seconds, which was broken down as follows: fifteen seconds were spent with the laser turned off, forty seconds were spent with laser ablation, and forty-five seconds were spent waiting for the washout to take place. During the final forty-five seconds of analysis, the sample was withdrawn from the system, causing the peak signal intensity to decline and return to background levels. Furthermore, the analytical methods applied in this study were previously described in publications [13,51].

A total of one hundred individual detrital zircon grains were analyzed from each sample except 24MM2, with a single analytical spot obtained from each grain. The Plesovice zircon standard was used to calibrate the U–Pb ages of the unknown detrital zircon grains. The Plesovice zircon standard exhibits a weighted mean age of 337 ± 0.37 Ma [52]. The ultimate ages of the individual zircon grains are determined using 207Pb/206Pb ages for those exceeding 1000 Ma and 206Pb/238U ages for those below 1000 Ma. The raw data were processed with Glitter 4.0 software to standardize the U–Pb ages in relation to the standard zircon Plesovice. Only zircon grains exhibiting less than 10% discordance were incorporated into the final analysis. The common Pb correction was applied to the processed data. The kernel density estimate (KDE) plots were created for the U–Pb ages of detrital zircon grains utilizing Density Plotter [53]. The comprehensive zircon U–Pb ages can be found in the Supporting Information Table S1.

5.2. Detrital Zircon U–Pb Results

5.2.1. Jabal Nakhal Section

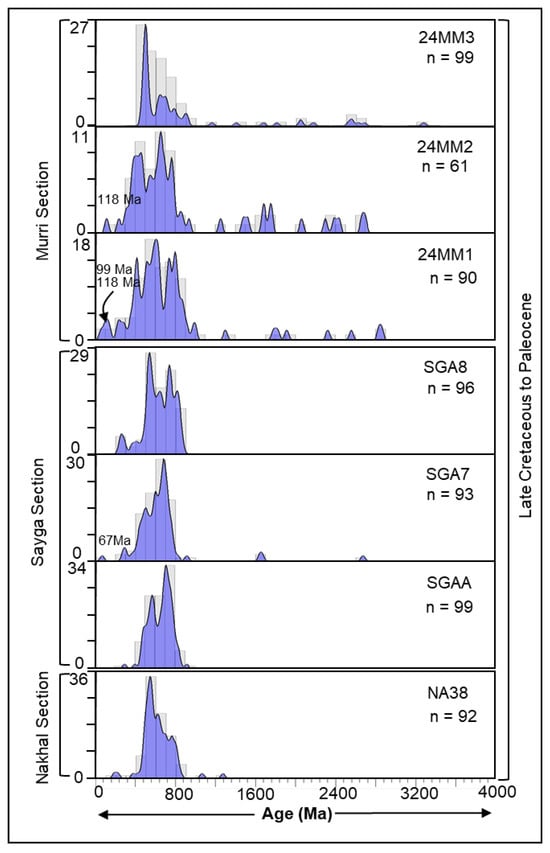

Zircon grains separated from sample NA38 exhibit considerable variation in size and morphology. Most grains display euhedral to subhedral forms, with a few occurring as elongate prismatic crystals. The majority of zircons are approximately 50 µm in length, although some prismatic grains reach up to ~100 µm. Internal textures show diverse zoning patterns (Figure S1), among which the core–rim structure is most common. A few grains display oscillatory or planar zoning. Sample NA38 was collected from the basal part of the Muti Formation and yielded 92 concordant ages out of 100 analyses. The detrital zircon age results show a significant age pattern between ~400 and ~900 Ma, which is 94% of the total ages (Figure 4). The significant peaks observed in this broad cluster are at ~500 Ma, ~550 Ma, ~620 Ma, ~700 Ma, and ~760 Ma. Two detrital zircons yielded Mesoproterozoic ages. The remaining three detrital zircons yielded Devonian, Permian, and Jurassic ages.

Figure 4.

Kernel density estimate (KDE) plots showing the age populations of the detrital zircons of the Muti Formation. The kernel bandwidth used is 20 Ma.

5.2.2. Sayga Section

Detrital zircons from the Sayga section predominantly exhibit euhedral to subhedral morphologies, with a minor proportion forming elongate prismatic grains that display oscillatory zoning. Oscillatory zoning is also commonly observed in the euhedral grains. Additional internal textures include sectoral and core–rim zoning, as well as planar features. Grain lengths generally range from ~50 to 75 µm, although a few crystals exceed 100 µm.

Sample SGAA represents the lower part of the Muti Formation immediately above the contact. Ninety-nine (99) concordant ages were obtained from this sample, which are mainly clustered between ~400 and 900 Ma (Figure 4). This is the single significant cluster. Only one detrital zircon yielded a Permian age (297 Ma).

Sample SGA7 yielded 93 concordant ages out of 100 analyses. The significant cluster in this sample is between the ages of 400 and 900 Ma, which is 90% of the total ages (Figure 4). The significant age peaks in this cluster are at 500 Ma, 600 Ma, and 680 Ma. In addition to the main cluster, other ages recorded in this sample are one Archean age, two Paleoproterozoic ages, five Devonian to Permian ages, and one Cretaceous age. The youngest age reported in this sample is 67 ± 3 Ma, which is Late Cretaceous.

Sample SGA8 represents the upper part of the Muti Formation from the Sayga section. 100 detrital zircon grains yielded 96 concordant ages. The ages in this sample are also clustered mainly between 400 and 900 Ma, which is 93% of the total ages (Figure 4). The age peaks observed in this cluster were ~530 Ma, ~630 Ma, ~750 Ma, and ~820 Ma. Five detrital zircon grains yielded Permian ages, and two detrital zircons yielded Devonian ages.

5.2.3. Murri Section

Detrital zircons from sample 24MM1 are predominantly elongate, with a minor proportion of rounded grains. The grains typically measure ~50–100 µm in length and ~40–50 µm in width, although a few larger crystals are also present. Internal textures are diverse, with oscillatory zoning being the most common. In addition, several grains exhibit sectoral and xenocrystic zoning, while a few display planar structures. Sample 24MM1 yielded 91 concordant ages out of 100 analyses. The detrital zircons’ ages were mainly between 400 and 900 Ma (Figure 4). This age cluster constitutes approximately 74% of the total zircon population. A small number of detrital zircons yield Mesoproterozoic to Archean ages, representing about 10% of the population. Additionally, Carboniferous–Permian ages account for roughly 7% of the total. The youngest age group is dominated by Cretaceous zircons, with a single grain recording a Paleocene age of 59.4 Ma.

Zircon grains from sample 24MM2 are predominantly large, with euhedral to subhedral morphologies. Most grains measure approximately 50–70 µm in length or diameter. Internal textures are dominated by oscillatory and sectoral zoning, although a few grains display planar structures, and core–rim relationships are also observed. A total of 62 concordant U–Pb ages were obtained from this sample out of 69 analyses. The majority of detrital zircons (~66%) cluster between 400 and 900 Ma (Figure 4). Additional age populations include Mesoproterozoic (~5%), Paleoproterozoic (~13%), and Archean (~3%) grains. Middle to Late Devonian ages constitute ~7% of the dataset, whereas two grains yielded Carboniferous ages and one grain a Permian age. The youngest zircon age obtained from this sample is 118 Ma.

Zircons from sample 24MM3 display a more heterogeneous and texturally mature population, with abundant anhedral, rounded, and broken grains (Figure S1). CL images show patchy zoning, irregular resorbed cores, and uneven overgrowths, with some grains also showing signs of recrystallization. Sample 24MM3 yielded a total of 99 concordant zircon ages. The majority of detrital ages (~86% of the total) cluster between ~400 and 900 Ma (Figure 4). The remaining ages are dispersed between ~1000 and 3271 Ma and are predominantly Paleoproterozoic and Archean in origin. Only two grains record Mesoproterozoic ages.

6. Discussion

6.1. Provenance of the Muti Formation

The siliciclastic components of the Muti Formation were derived from multiple source regions and were mainly transported as suspended load during deposition [44,54,55,56]. Sediment supply during the early Turonian likely originated from western and southern sources, including the Batain Mélange and uplifted basement rocks in the Jalaan and Huqf regions [34,57]. Additional detrital input may have been contributed by the Arabian–Nubian Shield to the west, which represents an extensive assemblage of Neoproterozoic crustal rocks [12,58,59,60,61,62]. The conglomeratic lithofacies, characterized by abundant chert clasts, are interpreted to record sediment supply from the obducted Hawasina allochthon. Collectively, these observations suggest that the Muti Formation accumulated from a mixture of proximal and distal sources, reflecting complex sediment routing within a syn-obduction foreland basin system. The petrographic features of the Muti Formation indicate a predominantly quartz-rich siliciclastic input derived from nearby continental basement sources surrounding the Jabal Akhdar Dome [55]. Angular to subangular quartz, sparse feldspar and mica, and low proportions of lithic fragments suggest limited transport and moderate chemical weathering, consistent with a stable cratonic to metamorphic provenance [31]. The uniformly low but persistent occurrence of heavy minerals such as zircon and rutile supports a compositionally mature heavy-mineral suite that indicates prolonged transport and/or sediment recycling; source terranes are therefore evaluated primarily using detrital zircon U–Pb ages. Minor well-rounded iron-rich mineral grains point to some reworking within the shallow-marine depositional setting, but overall the clastic fraction reflects a proximal, low-volume siliciclastic supply diluted by carbonate production [22,23].

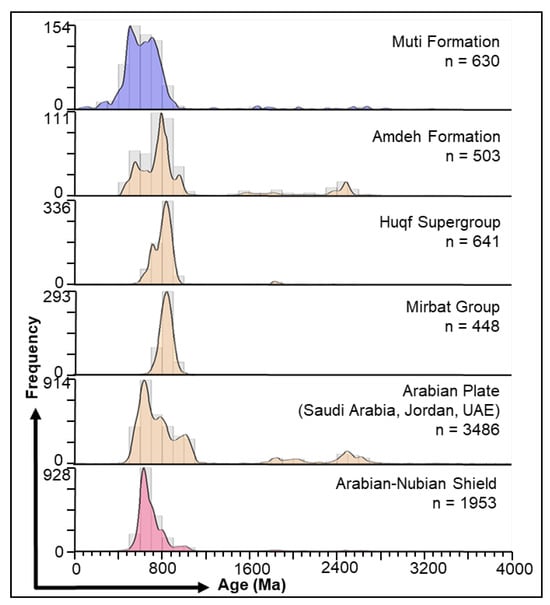

To establish robust constraints on sediment provenance, the U–Pb age spectra of the studied samples are compared with published zircon U–Pb datasets from potential source regions. These include the Huqf Supergroup, Mirbat Group, Amdeh Formation, the broader Arabian Plate, and the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Figure 5). Collectively, these source regions are characterized by a dominant Neoproterozoic zircon population, underscoring the Arabian–Nubian Shield (ANS) as the primary sediment source throughout much of Oman. Zircons from the Huqf Supergroup and Mirbat Group display prominent, narrow age peaks at ~750–820 Ma, corresponding to Cryogenian–Tonian magmatism related to the ANS arc and post-collisional tectonic activity [60,63,64]. These age patterns indicate derivation largely from nearby juvenile Neoproterozoic crust, with only limited input from older recycled sources. In contrast, detrital zircon populations from the Amdeh Formation and the broader Arabian Plate exhibit more heterogeneous age spectra, including substantial Mesoproterozoic–Paleoproterozoic components and minor Archean grains. This broader age distribution reflects mixed contributions from older Gondwanan basement terranes and recycled sedimentary successions, in agreement with regional provenance interpretations for Cambro–Ordovician sandstones across the Arabian Plate [65,66]. The Semail Ophiolite ages are mainly constrained between 104 and 90 Ma, which corresponds to initiation of obduction, crustal formation, and emplacement ages [67].

Detrital zircon U–Pb age spectra from the Muti Formation display dominant clusters between ~450 and ~900 Ma in both the eastern and western outcrops of the Jabal Akhdar Dome (Figure 5). This prominent age population corresponds to the Pan-African orogenic cycle and is characteristic of granitic and metamorphic rocks of the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Figure 5) [59,61,62,68]. Hence, this age component is interpreted to reflect derivation primarily from Arabian Shield source terrains, which supplied detritus to the evolving Cretaceous foreland basin.

In addition to the dominant Neoproterozoic component, minor Mesoproterozoic to Archean zircon ages were recorded, particularly in samples from the western Murri section. These older age components are not represented in the exposed Arabian Plate basement and are more consistent with sources on the Indian Plate [18,69]. Although direct sediment transport from India is unlikely during the Cretaceous, such grains may have been recycled from older sedimentary successions. Similar Proterozoic signatures have been reported from the Nafun Group (part of the Huqf Supergroup) of Oman, which is interpreted to record an earlier connection between the Arabian and Indian cratons [10,69]. Consequently, these Mesoproterozoic–Archean zircons in the Muti Formation were likely reworked from exposed Nafun Group strata during Cretaceous uplift and erosion.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the detrital zircon U–Pb ages of the source groups and terranes. The kernel bandwidth used for analyses is 20 Ma. The compilation data is taken from Sun and Chen [62]. The Amdeh Formation data is taken from Moss, et al. [70]. The Huqf Supergroup consisted of Abu-Mahara, Nafun, and Ara groups. The Amdeh Formation and Huqf Supergroup are geographically exposed in the Central Oman, and the Mirbat Group in the southwestern Oman. Arabian–Nubian shield rocks are mostly exposed in Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt.

Permian zircon ages are also present in most samples, suggesting contributions from Permian igneous and volcaniclastic rocks exposed within the Arabian Plate [71,72,73,74]. In addition, a few Cretaceous zircon ages (99 Ma and 118 Ma) are recorded, which overlap and/or slightly predate the ophiolite crystallization age and likely represent derivation from the obducted Semail Ophiolite and related arc sequences emplaced during obduction [75,76,77,78,79,80]. While the ages 59.4 Ma and 67 Ma are postdated to the ophiolitic crystallization and emplacement ages, they may reasonably be attributed to Pb loss due to later metamorphism and fluid-related events, which are well documented from the Oman Mountains [67,81] and further supported by the zircon internal structure (Figure S1).

Overall, the detrital zircon age spectra, in conjunction with sedimentological and lithological evidence, indicate that the Muti Formation was sourced from a mixed provenance comprising the Arabian–Nubian Shield, reworked older sedimentary successions (such as the Nafun Group), Permian magmatic rocks, and the obducted ophiolitic complexes. This provenance assemblage reflects the complex tectonic evolution and dynamic sediment routing associated with foreland basin development along the northeastern Arabian margin during the Late Cretaceous.

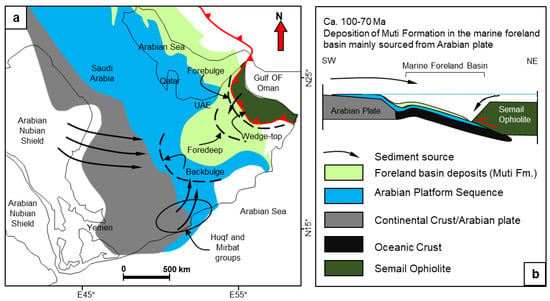

6.2. Tectonic Implication and Foreland Basin Evolution

The detrital zircon U–Pb age spectra obtained from the Muti Formation across the Jabal Akhdar Dome provide important constraints on the tectonic and depositional evolution of northern Oman during the Late Cretaceous. All samples from both the eastern (Nakhal and Sayga) and western (Murri) sections are dominated by zircon populations between ~400 and 900 Ma, with consistent peaks around 500–750 Ma (Figure 5). These ages correspond to widespread Pan-African granitoid sources of the Arabian–Nubian Shield, which represent the dominant sediment contributors to the evolving foreland basin [22,61,62,68,82]. The dominance of Pan-African signals in the Muti Formation is consistent with regional zircon compilations that identify a strong Cambrian–Neoproterozoic signature in clastic successions of the Arabian Plate [62,64,83,84].

The presence of scattered Mesoproterozoic and Archean grains in the Murri section suggests recycling of older sedimentary cover sequences, most likely from the Nafun Group, which contains similar ancient components and was exhumed during the Cretaceous [10,69,85,86,87]. Such reworked signals argue against direct input from India, since paleogeographic reconstructions indicate no Arabian–Indian connection at this time [22,62]. Permian zircon populations recorded in most samples are best explained by contributions from Permian volcanic and intrusive complexes on the Arabian Plate [22,28,71,74]. The youngest detrital zircon populations—spanning Jurassic to Cretaceous, and locally extending into Paleocene ages—indicate syn-tectonic sediment derivation from the obducted Semail Ophiolite and its related volcanic assemblages. These signatures record rapid uplift and erosion associated with thrust emplacement [22,56,88,89].

The resulting provenance patterns correspond closely with established models of passive-margin collapse and foreland basin formation during ophiolite obduction [22,69,90]. The Muti Formation represents the earliest sedimentary record of a flexural foredeep that evolved ahead of the advancing Semail Ophiolite thrust load [22,28]. Deposition within this basin was sustained by a mixed sediment supply, combining shield-derived siliciclastics, reworked Gondwanan sandstones, and ophiolite-derived detritus. Evidence for syn-tectonic olistostrome emplacement within the Aruma Basin [56] further supports a model of progressive thrust propagation, slope instability, and sediment remobilization into the developing foredeep (Figure 6a,b). Consequently, the foreland system evolved diachronously—initial flexural uplift and erosion along the Arabian margin were succeeded by gradual downwarping and deep-marine sedimentation beneath the advancing nappes [22,29,31,91].

Figure 6.

Tectonic model (a) map view and (b) sectional view (not to scale) explaining the formation of the Oman foreland basin in response to Semail ophiolite emplacement. The major sediment contribution is from the Arabian plate source. Semail Ophiolites were not aerially exposed to provide a major contribution. However, a minor contribution is reflected by a few younger grains.

At the regional scale, the detrital zircon record attests to the long-term recycling of Pan-African sand systems that persisted from the Cambrian to the Cretaceous [63,64,82,84,92]. Their recurrence within the Muti Formation demonstrates the enduring influence of Gondwanan sediment-routing systems across successive Phanerozoic basins. This multi-cycle sedimentary history refines earlier models focused primarily on local source contributions and emphasizes the broad paleogeographic connectivity of Oman along the northern Gondwanan margin [62].

Nevertheless, several uncertainties persist. The available zircon U–Pb dataset encompasses only a limited number of stratigraphic levels, and the youngest age populations are in some cases represented by single grains, introducing uncertainty in constraining maximum depositional ages. In summary, the Muti Formation summarizes a pivotal stage in the tectono-sedimentary evolution of the Arabian Plate—from passive-margin conditions to a flexural foreland basin established during Late Cretaceous ophiolite emplacement (Figure 6a,b). Its detrital zircon record reveals a polygenetic provenance linking Arabian Shield sources, recycled Gondwanan sandstones, and syn-tectonic ophiolitic detritus. Collectively, these results strengthen models of foreland basin evolution governed by thrust loading and highlight the persistent imprint of Pan-African source terrains on sediment routing across the Arabian margin.

7. Conclusions

This study resulted in the following conclusions;

- Detrital zircon U–Pb data from the Muti Formation indicate a mixed sediment supply sourced from the Arabian–Nubian Shield, reworked Nafun Group strata, Permian magmatic terranes, and syn-obduction ophiolites. Predominant Pan-African ages reflect sustained input from Arabian Shield rocks, while the sparse older zircons most likely record recycling of Gondwanan cover.

- The Cretaceous zircons reflect syn-tectonic erosion during emplacement of the Semail Ophiolite and early foreland basin subsidence; however, their sparse occurrence indicates only minor ophiolite contribution. Provenance variations in the Muti Formation are therefore dominated by recycled continental sources, with limited and localized input from obducted ophiolitic material during foredeep evolution.

- Regionally, the continuing Pan-African zircon signature reflects long-term recycling of Gondwana sand systems and reactivated sediment pathways, with the Muti Formation recording the Late Cretaceous shift from passive margin to foreland basin conditions driven by thrust loading, sediment recycling, and flexural subsidence.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/geosciences16010015/s1, Figure S1: Cathodoluminescence (CL) images of the analyzed detrital zircons showing internal structures of the grains; Table S1: U–Pb detrital zircon ages of the samples from the Late Cretaceous Muti Formation, Oman Foreland Basin.

Author Contributions

I.A.A.: Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition; M.Q.: Analyses, Writing—Review and Editing; J.A.A.: Sample collection; M.A.K.E.-G.: Review and Project administration; M.S.H.M.: Review and Editing; and L.D.: Funding and Review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the research grant RC/RG-SCI/ETHS/21/01 and IG/--/SCI/ES/25/059.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of the study are available in the article as a Supplementary File.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hamdan Al-Zidi for the preparation of thin sections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dickinson, W.R. Interpreting provenance relations from detrital modes of sandstones. In Provenance of Arenites; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 333–361. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, W.R.; Suczek, C.A. Plate tectonics and sandstone compositions. AAPG Bull. 1979, 63, 2164–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzanti, E. From static to dynamic provenance analysis—Sedimentary petrology upgraded. Sediment. Geol. 2016, 336, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husseini, M. Infra-Cambrian Wajid Graben and the Mozambique Suture, Saudi Arabia. Int. Geol. Rev. 2023, 65, 3168–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khirbash, S.; Heikal, M.T.S.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Windley, B.F.; Al Selwi, K. Evolution and mineralization of the Precambrian basement of Yemen. In The Geology of the Arabian-Nubian Shield; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 633–657. [Google Scholar]

- Arboit, F.; Ceriani, A.; Collins, A.; Hennhoefer, D.; Pilia, S.; Decarlis, A. The tectonic setting of the late Ediacaran eastern Arabian basement (ca. 550 Ma): New geochronological and geochemical constraints from the basements of Oman and the United Arab Emirates. Gondwana Res. 2024, 130, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blades, M.; Alessio, B.; Collins, A.; Foden, J.; Payne, J.; Glorie, S.; Holden, P.; Thorpe, B.; Al-Khirbash, S. Unravelling the Neoproterozoic accretionary history of Oman, using an array of isotopic systems in zircon. J. Geol. Soc. 2020, 177, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessouky, O.K.; Ali, K.A.; Hassan, M.M. Hf Isotopes and Detrital Zircon Geochronology of the Silasia Formation, Midyan Terrane, Northwestern Arabian Shield: An Investigation of the Provenance History. Geol. J. 2024, 59, 3092–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzanti, E.; Andò, S.; Vezzoli, G.; Dell’era, D. From rifted margins to foreland basins: Investigating provenance and sediment dispersal across desert Arabia (Oman, UAE). J. Sediment. Res. 2003, 73, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pérez, I.; Morton, A. Neoproterozoic–early Paleozoic tectonic evolution of Oman revisited: Implications for the consolidation of Gondwana. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2025, 550, 27–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J.; Ellison, R.A.; Goodenough, K.M.; Roberts, N.M.; Allen, P.A. Salt domes of the UAE and Oman: Probing eastern Arabia. Precambrian Res. 2015, 256, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, M.J.; Pease, V.; Al-Khirbash, S. Neoproterozoic crustal growth at the margin of the East Gondwana continent–age and isotopic constraints from the easternmost inliers of Oman. Int. Geol. Rev. 2016, 58, 2046–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Ding, L.; Khan, M.A.; Jadoon, I.A.K.; Haneef, M.; Baral, U.; Cai, F.; Wang, H.; Yue, Y. Tectonic Implications of Detrital Zircon Ages From Lesser Himalayan Mesozoic-Cenozoic Strata, Pakistan. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2018, 19, 1636–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M.N.A.; Baral, U.; Qasim, M.; Tanoli, J.I.; Rehman, Q.U.; Ding, L.; Scharf, A. Uplift and Erosion in the Western Himalaya: Insight from U–Pb Ages of Detrital Zircon Recovered from the Miocene Foreland Basin Deposits, Pakistan. Geol. J. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCelles, P.G.; Gehrels, G.E.; Quade, J.; Ojha, T.P.; Kapp, P.A.; Upreti, B.N. Neogene foreland basin deposits, erosional unroofing, and the kinematic history of the Himalayan fold-thrust belt, western Nepal. GSA Bull. 1998, 110, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moecher, D.P.; Samson, S.D. Differential zircon fertility of source terranes and natural bias in the detrital zircon record: Implications for sedimentary provenance analysis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 247, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Qasim, M.; Tanoli, J.I.; Ding, L.; Sattar, M.; Baig, M.S.; Pervaiz, S. Detrital Zircon Provenance of the Cenozoic Sequence, Kotli, Northwestern Himalaya, Pakistan; Implications for India–Asia Collision. Minerals 2021, 11, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Ding, L.; Khan, M.A.; Umar, M.; Jadoon, I.A.; Haneef, M.; Baral, U.; Cai, F.; Shah, A.; Yao, W. Late Neoproterozoic–Early Palaeozoic stratigraphic succession, western Himalaya, north Pakistan: Detrital zircon provenance and tectonic implications. Geol. J. 2018, 53, 2258–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Ashraf, J.; Ding, L.; Tanoli, J.I.; Khan, I.; Rehman, M.U.; Awais, M.; Ahmad, J.; Tayyab, O.; Jadoon, I.A. The Early Paleocene Ranikot Formation, Sulaiman Fold-Thrust Belt, Pakistan: Detrital Zircon Provenance and Tectonic Implications. Minerals 2023, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, D.; O’Sullivan, G.; Caracciolo, L.; Mark, C.; Tyrrell, S. Sourcing the sand: Accessory mineral fertility, analytical and other biases in detrital U-Pb provenance analysis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 202, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T. Detrital zircons as tracers of sedimentary provenance: Limiting conditions from statistics and numerical simulation. Chem. Geol. 2005, 216, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A. The transition from a passive margin to an Upper Cretaceous foreland basin related to ophiolite emplacement in the Oman Mountains. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1987, 99, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.H.F.; Searle, M.P. The northern Oman Tethyan continental margin: Stratigraphy, structure, concepts and controversies. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1990, 49, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Y.; Aidarbayev, S.; Searle, M.P.; Watts, A.B. Subsidence History and Seismic Stratigraphy of the Western Musandam Peninsula, Oman–United Arab Emirates Mountains. Tectonics 2018, 37, 154–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.W.; Ali, M.Y.; Searle, M.P. Structure of the northern Oman Mountains from the Semail Ophiolite to the Foreland Basin. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2014, 392, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennie, K.; Reinhardt, B. Late Cretaceous nappes in Oman Mountains and their geologic evolution: Reply to JD Moody. AAPG Bull. 1974, 58, 895–898. [Google Scholar]

- Levell, B.; Searle, M.; White, A.; Kedar, L.; Droste, H.; Van Steenwinkel, M. Geological and seismic evidence for the tectonic evolution of the NE Oman continental margin and Gulf of Oman. Geosphere 2021, 17, 1472–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennie, K.W.; Clarke, M.W.H. Late Cretaceous Nappes in Oman Mountains and Their Geologic Evolution: REPLY1. AAPG Bull. 1973, 57, 2287–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, J.A.; Ahmed Abbasi, I.; Moustafa, M.; El-Ghali, M.A.; Qasim, M. Chemostratigraphic Signature Variations in the Upper Cretaceous Marine Foreland Basin Sediments: An Example From the Muti Formation Outcrops, Jabal Akhdar Dome, North Oman. Geol. J. 2025, 60, 3079–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabri, M.S.; Abbasi, I.A.; Hanif, M.; El-Ghali, M.A.; Al Sayigh, A. Integrated facies analysis of the Late Cretaceous Simsima Formation in northwestern Oman mountain, Jabel Al-Rawdah, Hatta area, Oman. Arab. J. Geosci. 2024, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, J.A.; Abbasi, I.A.; El-Ghali, M.; Al-Harthi, A.R.; Al-Sayigh, A. Lithofacies Associations and Depositional System of the Muti Formation, Oman Mountains. In Proceedings of International Conference on Mediterranean Geosciences Union, Marrakech, Morocco, 27–30 November 2022; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, M.; Cox, J. Tectonic setting, origin, and obduction of the Oman ophiolite. GSA Bull. 1999, 111, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollinson, H.R.; Searle, M.P.; Abbasi, I.A.; Al-Lazki, A.I.; Al Kindi, M.H. Tectonic evolution of the Oman Mountains: An introduction. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2014, 392, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosveld, R.J.; Bell, A.; Terken, J.J. The tectonic evolution of interior Oman. GeoArabia 1996, 1, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, J.; Burnhill, T.J.; Graham, R.H.; Isaac, K.P. The evolution of the Oman Mountains Foreland Basin. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1990, 49, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Watts, A. Subsidence history, crustal structure, and evolution of the Somaliland-Yemen conjugate margin. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Y.; Watts, A. Subsidence history, gravity anomalies and flexure of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) foreland basin. GeoArabia 2009, 14, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Mattern, F.; Al-Wardi, M.; Frijia, G.; Moraetis, D.; Pracejus, B.; Bauer, W.; Callegari, I. The Geology and Tectonics of the Jabal Akhdar and Saih Hatat Domes, Oman Mountains; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2021; Volume 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Al-Kindi, M.; Racey, A. An introduction to geology, tectonics and natural resources of Arabia and its surroundings. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2025, 550, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghali, M.A.K.; Moustafa, M.S.H.; Al-Mahrouqi, B.; Al-Harthi, A.R.; Al-Sayigh, A.; Siddiqui, N.A. Lithofacies and microfacies of Paleogene deep marine slope carbonate system of the Ruwaydah Formation in the southern Arabian Peninsula: Implications for hydrocarbon exploration and development. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2025, 290, 106656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J.; Borgomano, J.; Al-Maskiry, S. Cenomanian-Early Turonian carbonate platform of Northern Oman: Stratigraphy and palaeo-environments. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1995, 119, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, S.; Skelton, P.; Clissold, B.; Smewing, J. Maastrichtian to early Tertiary stratigraphy and palaeogeography of the central and northern Oman Mountains. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1990, 49, 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, M.P. Structural geometry, style and timing of deformation in the Hawasina Window, Al Jabal al Akhdar and Saih Hatat culminations, Oman Mountains. GeoArabia 2007, 12, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I.A.; Hersi, O.S.; Al-Harthy, A. Late cretaceous conglomerates of the qahlah formation, north Oman. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2014, 392, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, E.; Abbasi, İ.A.; Yücel, A.O.; Aşcı, S.Y.; Erkızan, L.S.; El-Ghali, M.A.; Çalışkan, D.; Gültekin, M.N.; Kayğılı, S. First record of the foraminiferal genera Clypeorbis Douvillé and Ilgazina Erdoğan from the Maastrichtian of the Arabian Peninsula (Simsima Formation, North Oman): Paleobiogeographic implications. Cretac. Res. 2022, 138, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayğılı, S.; Yücel, A.O.; Abbasi, İ.A.; Catanzariti, R.; Özcan, E. A new species of Omphalocyclus Bronn, O. omanensis sp. nov., from the upper Campanian of Oman: Phylogenetic and stratigraphic implications. Cretac. Res. 2021, 124, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberian, M. Master “blind” thrust faults hidden under the Zagros folds: Active basement tectonics and surface morphotectonics. Tectonophysics 1995, 241, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouthereau, F.; Lacombe, O.; Vergés, J. Building the Zagros collisional orogen: Timing, strain distribution and the dynamics of Arabia/Eurasia plate convergence. Tectonophysics 2012, 532, 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebari, M.; Preusser, F.; Grützner, C.; Navabpour, P.; Ustaszewski, K. Late Pleistocene-Holocene Slip Rates in the Northwestern Zagros Mountains (Kurdistan Region of Iraq) Derived From Luminescence Dating of River Terraces and Structural Modeling. Tectonics 2021, 40, e2020TC006565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Callegari, I.; Bailey, C.M.; Mattern, F.; Zack, T.; Hansman, R.; Qasim, M.; Ring, U. Tectonic setting of naturally carbonated ultramafic rocks from the Samail Ophiolite (Sultanate of Oman). GSA Bull. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Ding, L.; Leary, R.J.; Wang, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yue, Y. Tectonostratigraphy and provenance of an accretionary complex within the Yarlung–Zangpo suture zone, southern Tibet: Insights into subduction–accretion processes in the Neo-Tethys. Tectonophysics 2012, 574, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sláma, J.; Košler, J.; Condon, D.J.; Crowley, J.L.; Gerdes, A.; Hanchar, J.M.; Horstwood, M.S.; Morris, G.A.; Nasdala, L.; Norberg, N. Plešovice zircon—A new natural reference material for U–Pb and Hf isotopic microanalysis. Chem. Geol. 2008, 249, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeesch, P. On the visualisation of detrital age distributions. Chem. Geol. 2012, 312–313, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I.; Friend, P. Exotic conglomerates of the Neogene Siwalik succession and their implications for the tectonic and topographic evolution of the Western Himalaya. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2000, 170, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, F.; Pracejus, B.; Scharf, A.; Frijia, G.; Al-Salmani, M. Microfacies and composition of ferruginous beds at the platform-foreland basin transition (Late Albian to Turonian Natih Formation, Oman Mountains): Forebulge dynamics and regional to global tectono-geochemical framework. Sediment. Geol. 2022, 429, 106074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, F.; Scharf, A.; Pracejus, B.; Al Shibli, I.S.; Al Kabani, B.M.; Al Qasmi, W.Y.; Kiessling, W.; Callegari, I. Origin of the Cretaceous olistostromes in the Oman mountains (Sultanate of Oman): Evidence from clay minerals. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2022, 191, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, J.-P.; Béchennec, F.; Le Métour, J.; Moen-Maurel, L.; Razin, P. Eoalpine (Cretaceous) evolution of the Oman Tethyan continental margin: Insights from a structural field study in Jabal Akhdar (Oman Mountains). GeoArabia 2004, 9, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowring, S.A.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Condon, D.J.; Ramezani, J.; Newall, M.J.; Allen, P.A. Geochronologic constraints on the chronostratigraphic framework of the Neoproterozoic Huqf Supergroup, Sultanate of Oman. Am. J. Sci. 2007, 307, 1097–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.; Andresen, A.; Collins, A.; Fowler, A.; Fritz, H.; Ghebreab, W.; Kusky, T.; Stern, R. Late Cryogenian–Ediacaran history of the Arabian–Nubian Shield: A review of depositional, plutonic, structural, and tectonic events in the closing stages of the northern East African Orogen. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2011, 61, 167–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieu, R.; Allen, P.A.; Cozzi, A.; Kosler, J.; Bussy, F. A composite stratigraphy for the Neoproterozoic Huqf Supergroup of Oman: Integrating new litho-, chemo-and chronostratigraphic data of the Mirbat area, southern Oman. J. Geol. Soc. 2007, 164, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.J. Arc assembly and continental collision in the Neoproterozoic African Orogen: Implications for the consolidation of Gondwanaland. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1994, 22, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Chen, J. A database of detrital zircon U–Pb ages and Hf isotopes for the Middle East (Iranian and Arabian plates). Geosci. Data J. 2024, 11, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avigad, D.; Kolodner, K.; McWilliams, M.; Persing, H.; Weissbrod, T. Origin of northern Gondwana Cambrian sandstone revealed by detrital zircon SHRIMP dating. Geology 2003, 31, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodner, K.; Avigad, D.; Ireland, T.R.; Garfunkel, Z. Origin of Lower Cretaceous (‘Nubian’) sandstones of North-east Africa and Arabia from detrital zircon U-Pb SHRIMP dating. Sedimentology 2009, 56, 2010–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morag, N.; Avigad, D.; Gerdes, A.; Belousova, E.; Harlavan, Y. Long-distance transport of North Gondwana Cambro-Ordovician sandstones: Evidence from detrital zircon Hf isotopic composition. Mineral. Mag. 2011, 75, 1497. [Google Scholar]

- Yeshanew, F.G.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Pease, V.; Badenszki, E.; Daly, J.S. Continental-scale sediment mixing and dispersal across northern Gondwana: Detrital zircon U-Pb-O-Hf isotopic evidence from the Cambro-Ordovician sandstones overlying the Arabian Shield. Int. Geol. Rev. 2025, 67, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, M.P.; Garber, J.M.; Rioux, M. Structure of the NE Oman Mountains: A Review of Robust Geochronological Constraints for Tectonic Models of Ophiolite Obduction and Continental Subduction. Tectonics 2025, 44, e2025TC008834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.J.; Johnson, P. Continental lithosphere of the Arabian Plate: A geologic, petrologic, and geophysical synthesis. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2010, 101, 29–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pérez, I.; Morton, A.; Rawahi, H.A.; Frei, D. Oman as a fragment of Ediacaran eastern Gondwana. Geology 2024, 52, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.; Tansell, C.; Gómez-Pérez, I.; McCabe, R.; Fairey, B.; al Thohli, B. Chemostratigraphic characterization of the Lower Paleozoic Amdeh Formation outcrops and correlation to the subsurface Haima Supergroup and Nimr Group, Sultanate of Oman. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2025, 550, 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, W.; Callegari, I.; Al Balushi, N.; Al Busaidi, G.; Al Barumi, M.; Al Shoukri, Y. Tectonic observations in the northern Saih Hatat, Sultanate of Oman. Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, W.; Qasim, M.; Jacobs, J.; Callegari, I.; Scharf, A. Timing of Permian rifting in the Saih Hatat Dome (Sultanate of Oman). In Proceedings of EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vienna, Austria, 27 April–2 May 2025; p. EGU25-22. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet, F.; Dumont, T.; Basile, C. Structures and timing of Permian rifting in the central Oman Mountains (Saih Hatat). Tectonophysics 2009, 475, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Qasim, M.; Callegari, I.; Bauer, W. Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology of the basal Saiq siliclastics–A complete magmatic record from the Archean to the Permian/Triassic of NE Sultanate of Oman. In Proceedings of EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vienna, Austria, 27 April–2 May 2025; p. EGU25-3424. [Google Scholar]

- Gnos, E.; Peters, T. K-Ar ages of the metamorphic sole of the Semail Ophiolite: Implications for ophiolite cooling history. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1993, 113, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.M.; Thomas, R.J.; Jacobs, J. Geochronological constraints on the metamorphic sole of the Semail ophiolite in the United Arab Emirates. Geosci. Front. 2016, 7, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.J.; Parrish, R.R.; Searle, M.P.; Waters, D.J. Dating the subduction of the Arabian continental margin beneath the Semail ophiolite, Oman. Geology 2003, 31, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.J.; Parrish, R.R.; Waters, D.J.; Searle, M.P. Dating the geologic history of Oman’s Semail ophiolite: Insights from U-Pb geochronology. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2005, 150, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, M.; Bowring, S.; Kelemen, P.; Gordon, S.; Dudás, F.; Miller, R. Rapid crustal accretion and magma assimilation in the Oman-U.A.E. ophiolite: High precision U-Pb zircon geochronology of the gabbroic crust. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2012, 117, B07201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, M.; Bowring, S.; Kelemen, P.; Gordon, S.; Miller, R.; Dudás, F. Tectonic development of the Samail ophiolite: High-precision U-Pb zircon geochronology and Sm-Nd isotopic constraints on crustal growth and emplacement. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 2085–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, B.R.; Mosenfelder, J.L.; Gnos, E. Rapid emplacement of the Oman ophiolite: Thermal and geochronologic constraints. Tectonics 1996, 15, 1230–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avigad, D.; Gerdes, A.; Morag, N.; Bechstädt, T. Coupled U–Pb–Hf of detrital zircons of Cambrian sandstones from Morocco and Sardinia: Implications for provenance and Precambrian crustal evolution of North Africa. Gondwana Res. 2012, 21, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, G.; Bassis, A.; Hinderer, M.; Lewin, A.; Berndt, J. Detrital zircon provenance of north Gondwana Palaeozoic sandstones from Saudi Arabia. Geol. Mag. 2021, 158, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, G.; Morton, A.C.; Avigad, D. New insights into peri-Gondwana paleogeography and the Gondwana super-fan system from detrital zircon U–Pb ages. Gondwana Res. 2013, 23, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.S.; Blades, M.L.; Merdith, A.S.; Foden, J.D. Closure of the Proterozoic Mozambique Ocean was instigated by a late Tonian plate reorganization event. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.R. The Arabian–Nubian Shield, an introduction: Historic overview, concepts, interpretations, and future issues. In The Geology of the Arabian-Nubian Shield; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kröner, A. Ophiolites and the evolution of tectonic boundaries in the late proterozoic Arabian—Nubian shield of northeast Africa and Arabia. Precambrian Res. 1985, 27, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaii Moghadam, H.; Corfu, F.; Stern, R.J. U–Pb zircon ages of Late Cretaceous Nain–Dehshir ophiolites, central Iran. J. Geol. Soc. 2013, 170, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Ashraf, J.; Ding, L.; Tanoli, J.I.; Cai, F.; Ahmed Abbasi, I.; Jadoon, S.-U.-R.K. Rapid India–Asia Initial Collision Between 50 and 48 Ma Along the Western Margin of the Indian Plate: Detrital Zircon Provenance Evidence. Geosciences 2024, 14, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, M.; Warren, C.; Waters, D.; Parrish, R. Structural evolution, metamorphism and restoration of the Arabian continental margin, Saih Hatat region, Oman Mountains. J. Struct. Geol. 2004, 26, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, M.; Graham, G. “Oman Exotics”—Oceanic carbonate build-ups associated with the early stages of continental rifting. Geology 1982, 10, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, G.; Morton, A.C.; Fanning, C.M.; Frei, D.; Howard, J.P.; Phillips, R.J.; Strogen, D.; Whitham, A.G. Evidence from detrital zircons for recycling of Mesoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic crust recorded in Paleozoic and Mesozoic sandstones of southern Libya. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 312, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.