Abstract

During the course of the Carboniferous to Permian, large parts of eastern Laurentia and northern Gondwana were affected by the Variscan Orogeny accompanying the assembly of Pangea. Here, we concentrate on the Appalachian belt of eastern Laurentia and the Mauritanide of western Gondwana. Owing to the irregular shapes of the craton margins, the collision between Laurentia and the West African Craton provides several conjugate promontories and embayments alongside both cratons. Among others, the coupled pair formed by the African Reguibat promontory and its counterpart in North America, the Pennsylvania embayment, is the principal subject of this study. The western movement of the Reguibat Shield had initially imprinted the West African belts but finally also affected the Appalachians. Acting as a “hallmark”, it produced two specific lobes (stacks of nappes) on both sides of the promontory. The southern NW-SW lobe (Akjoujt nappes) is long known. However, the northern lobe of the “Adrar Souttouf Massif” has not been identified previously, owing to being partially covered and also to its N-S alignment instead of an expected symmetrical SW-NE direction. Furthermore, the Adrar Souttouf Massif is partially covered by allochthonous terranes (Western Thrust Belt, TB, or Appalachians). This new discovery supports a classical impingement model for the deformation of the North American and African belts by westward displacement of the Reguibat Shield.

1. Introduction

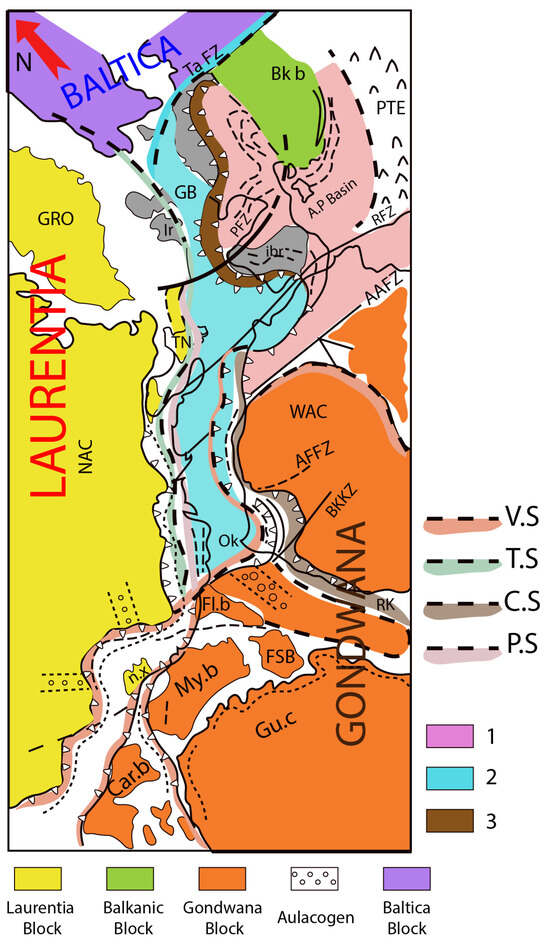

The various Variscan sutures between Laurussia and northern Gondwana wereformed during the assembly of Pangea and have an irregular, curved shape (Figure 1). This results in several promontories and embayments. The embayments on the Laurentian side correspond to promontories on the opposite West African Craton (WAC) and vice versa.

Figure 1.

Sketch map of the Variscan belts in the collision zone between Gondwana, Laurentia and Baltica blocks. 1—Southern European Variscan belts; 2—Appalachian and Northern European belts; 3—Anté-Variscan West Gondwana belts (Bassaride, Rokelides, Souttoufides, etc.); arrows are indicating the direction of thrusts and sutures; VS: Variscan suture (Alleghanian?); TS: Taconic; CS: Caledonian suture; PS: Panafrican suture; NAC: North American Craton; WAC: West African Craton; Bk b: Balkanic block; GB: Great Britain; TN: Newfoundland; GRO: Greenland; PTE: Peri-Thetys; Flb: Florida block; RK: Rokelide Belt; Car.b: Caribbean Block; My.b: Maya block; Gu.c: Guyana Shield; FSB: Florida Sea basin; TaFZ: Tornquist fault zone; PFZ: Pyrenean fault zone; AAFZ: Anti-Atlas Fault Zone; AFFZ: AoukerFault Zone; BKKF Bissau–KidiraFault Zone; Ir: Ireland; Ck: Conakry, Ibr: Iberia; nx: Mixteca.

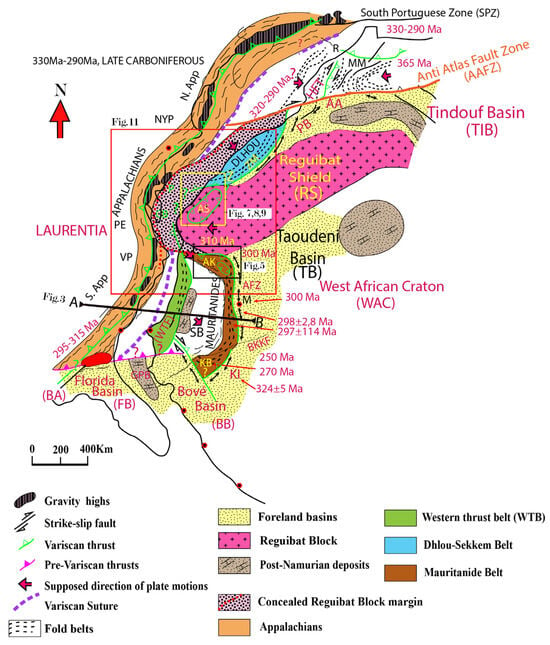

Here, we are focused on the interaction between the West African Reguibat promontory and the corresponding Pennsylvania embayment in Laurentia (Figure 2). These two regions are bordered by the Senegalese–Mauritanian embayment (SB) and the corresponding Virginia promontory (VP) to the south and by the Moroccan–Iberian embayment and corresponding New York or Avalonian promontory to the north (Figure 2). The southern limit of the Reguibat Shield is marked by the Aouker Fault Zone (AKFZ) to the south and by the Anti-Atlas Fault Zone to the north (AAFZ). While only the southern parts of the Reguibat Shield crop out, its northern parts are concealed underneath sedimentary rocks of the Tindouf Basin. The latter has often resulted in underestimations of the importance of the Reguibat Shield (northern outcrop of the WAC) in constraining reconstructions of Pangea.

Figure 2.

Geological sketch map of the Variscan belts in West Africa and North America, modified from [1], with indication of local geological schemes of this study. AA—Anti-Atlas Belt; AS—Adrar Souttouf Massif; SB—Senegalese Block; MM—Moroccan Meseta; PB—Plage Blanche; ZM—Zemmour massif; TIB—Tindouf Basin; TB—Taoudeni Basin; KB—Koulountou Block; BB—Bové Basin; GPB—Guinean Paleozoic Basin; FL-SB—Florida or Suwanee Basin; SApp—Southern Appalachians; Napp—Northern Appalachians; VP—Virginia promontory; PE—Pennsylvania Embayment; NYP—New York Promontory; AK—Akjoujt. Numbers—Ages of deformations presented in Ma.

The Reguibat Shield is tripartite: (1) a concealed convex western element, (2) a more distal element, now preserved in the Appalachians and (3) the Souttoufide Belt, located between the Mauritanides and the Anti-Atlas Fault Zone, to the north. The latter includes, from the south to the north, the Adrar Souttouf Massif; the Zemmour Massif, including the adjacent Dhlou–(Sekkem Belt and finally, the “Plage Blanche” Belt [2]. The Reguibat promontory is the southwestern most part of the Reguibat Shield and is bounded to the south by the Mauritanide Belt and to the north by the Adrar Souttouf Massif. Thus, the northern and southern segments of this Reguibat Shield are not symmetric (Figure 2). This asymmetry is inconsistent with the traditional model and hence triggered contesting interpretations of the Adrar Souttouf Massif [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. This interpretation reconciles the idea of a central synform of sheets thrust on the Reguibat basement from the east [8,10] and the idea of a stack of nappes, thrust from the west to the east [2,9,11]. These elements, combined with the asymmetry in the orientation of structures, preclude direct application of the Lefort model [12,13] of impingement. The Lefort model is discussed in Section 3. Although the southern part of the Reguibat promontory can be observed in the field, its northern continuation is concealed under thick sedimentary sequences. The aim of this paper is to compare the model with field observations.

Our new interpretation reconciles the different points of view and allows us to propose a better “impingement” model for both sides of the Palaeozoic Rheic Ocean.

2. Geological Framework

The collision of West Africa and North America during the assembly of Pangaea resulted in the formation of the Variscan Orogen, the location of which is shown in Figure 2. The orogen has a mainly N-S trend and can be traced from Morocco to Senegal. Furthermore, the resultant suture is linked to the E-W-directed Brunswick magnetic anomaly, BA in Figure 2, which is located between the Appalachians and the Florida Basin. Furthermore, the North American orogenic segment includes large portions of basement and the Appalachians retain a capitalized version of the older Laurentian cratonic basement. The eastern part of the Variscan suture is more complex. It includes the WAC basement surrounded by two Variscan belts, the Adrar Souttouf and Dhlou–Sekkem belts, both representing parts of the Souttoufide Belt to the north and the Western Thrust Belt (WTB) and the Mauritanide Belt, which are separated by the Senegalese Block, including the foreland basins, to the south. The foreland basins associated with the Reguibat Shield and its bordering orogenic belts comprise the poorly deformed Tindouf, Taoudeni and Bové basins in Africa and the Guinean Palaeozoic Basin (GPB) and Suwannee basins (or Florida basin) in the subsurface of Florida. A geological cross-section from the Appalachians to the Mauritanidesis shown in Figure 3 shows a double vergence between the Appalachians and the WTB. We note a vergence to the east for the Mauritanide Belt that is separated from the WTB by the rigid Senegalese Block (SB in Figure 3). Given the absence of a magmatic arc in the WTB and some evidence of magmatic arc in the Appalachians [14,15,16,17], a westward slab vergence with a subduction zone to the west is considered [2] and has given rise to the Appalachian fold and thrust belt.

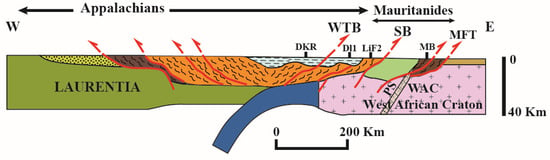

Figure 3.

Schematic cross-section along line A–B, in Figure 2. Legend: as in Figure 2. Slab in blue. DKR—Dakar; Dl1—Diourbel well; LiF2—Linguere well; WTB—Western Thrust Belt; SB—Senegalese Block; MB—Mauritanide Belt; MFT—Mauritanide Front thrust; PS—Precambrian suture associated with the Bassaride and Rokelide belts. External formations (in brown) correspond to a mixed formation with pre-Variscan and Variscan formations. Red arrow: direction of thrusts.

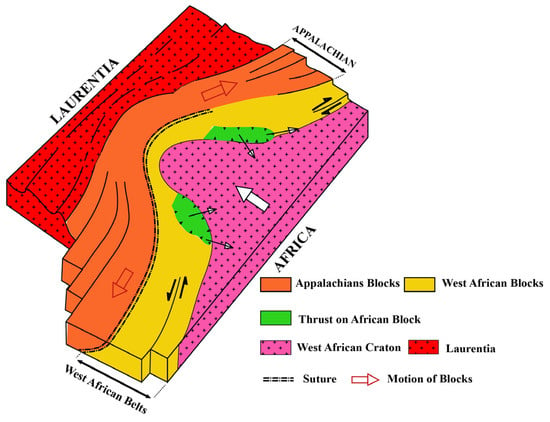

3. The Reguibat Promontory Model of Lefort

A model of the Reguibat impinging on Laurentia has been proposed by Lefort [12,13] and presented in Figure 4. This model only considers the southwestern part of the Reguibat Shield acting as a promontory. As shown in Figure 4, the westward motion of the southern part of the Reguibat Shield is compressed by the Appalachian and Mauritanide belts, giving rise to the “nappes”, comprising fragments of older continental crust and passive margin that are now stacked on both sides of the promontory (areas in green in Figure 4). These areas of tectonic escape are furthermore characterized by dextral strike-slip motions along the northern fault and sinistral strike-slip motions along the southern fault that can also be found in the Appalachians, where dextral shearing is predominant. The “nappes” motion is antithetic to the direction of plate convergence. The nonconformity of the shearing with respect to the theoretical model is likely linked to the geological history of the Appalachians, where several orogens are superimposed.

Figure 4.

Block diagram that illustrates the tectonic model for the imprint of the Reguibat shield onto the Southern and Central Appalachians (modified from [13]). West African Blocks include the Mauritanide belt, the Senegalese block and the WTB (Western Thrust Belt). The Appalachian bloc is an orange colour.

4. Field Observations

Field observations have been undertaken in the central Appalachians [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], in the Akjoujt area of the northern Mauritanides [22] and in the southern Souttoufides (Adrar Souttouf Massif) [2,10,23,24,25,26].

4.1. The Appalachians

The Reguibat promontory likely caused the distinction between the southern Appalachians (S.App) and the northern Appalachians (N.App) by the Pennsylvania embayment (PE in Figure 2). According to Hibbart et al. [14], the Appalachians can be divided into three parallel belts: the Laurentian terranes to the west, the Iapetian terranes in the middle and the peri-Gondwanan terranes to the east. In the southern Appalachians, there are several strike-slip faults parallel to the three zones. The strike-slip movements along these faults are dextral [15,16,17,18] and not in accordance with the theoretical model. In the Northern Appalachians, the geological structures are more complex, notably with the three peri-Gondwanan terranes of Ganderia, W-Avalonia and Meguma (not on the map). However, it is generally agreed that dextral strike-slip motion also occurred along the major faults which can also be ascribed to the last oblique collisional event between Laurentia and Gondwana [18,19,20,21].

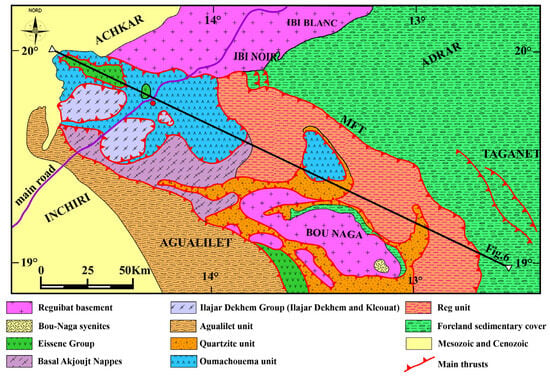

4.2. The Northern Mauritanides Wih Akjoujt Area (See Figure 5, Indicated in Figure 2)

This part of the Mauritanide Belt is located in the southern part of the Reguibat Shield between the Aouker Trough (AFZ in Figure 2) and the Reguibat Shield. The main tectonic event in the Akjoujt stratigraphic series previously ascribed to the Panafrican orogeny was finally ascribed to the Variscan Orogen by Teissier et al. [27] and Sougy [28] as well as Lecorché [22] and Bradley et al. [29]. Detailed mapping of these structural units is provided by Martyn and Strickland [30] as well as Pittfield et al. [31]. The geological map in Figure 5 shows a Reguibat basement (Archaean and Palaeoproterozoic) covered by Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks. These basal formations are tectonically capped by the Reg Unit, which contains various rocks similar to those of the Cambro-Ordovician foreland cover. This Reg Unit has been dismembered and thrust over the foreland units. The mainly allochthonous Akjoujt terrane is stratigraphically above them and includes a mix of thrust sheets composed of various rocks such as quartzite, siltstone, migmatite and porphyritic granite. The Akjoujt Unit is interpreted to be a thrust stack (Figure 5 and Figure 6) that was emplaced from the NW to the SE [32,33] and partially covered by the Agualilet Unit; it crops out in the southwestern part of this area and consists of siliciclastic and volcanic and magmatic rocks such as basalt, gabbro, prasinite (not interpreted by authors but likely related to panafrican ophiolitic remnants) and silicitic tuff thrusted over the previously mentioned units during a Carboniferous tectonic event.

Figure 5.

Geological map of the northern Mauritanide area (indicated in Figure 2). This Akjoujt area is surrounded by the Senegalese Block (to the south), the Taoudeni basin (to the east) and the Reguibat shield (to the north). (Modified from Lecorché et al. [33]). The different nappes (Reg unit, Quartzite unit, Basal Akjoujt unit, Oumachouema, Ajar Dherem and Eisenne groups) are indicated in the legends. MFT-Mauritanide Front Thrust.

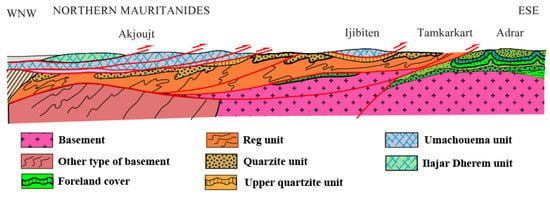

Figure 6.

Cross-section (located in Figure 5) interpreted after Lecorché [22] illustrating the structure from Akjoujt to the Taoudeni foreland (modified from Lecorché et al. [33]).

4.3. Souttoufide Belt

The Souttoufide Belt [2] includes three separate parts: the “Adrar Souttouf Massif”, the “Dhlou Belt and Zemmour Massif” and the “Plage Blanche” Belt (located in Figure 2).

4.3.1. Adrar Souttouf Massif

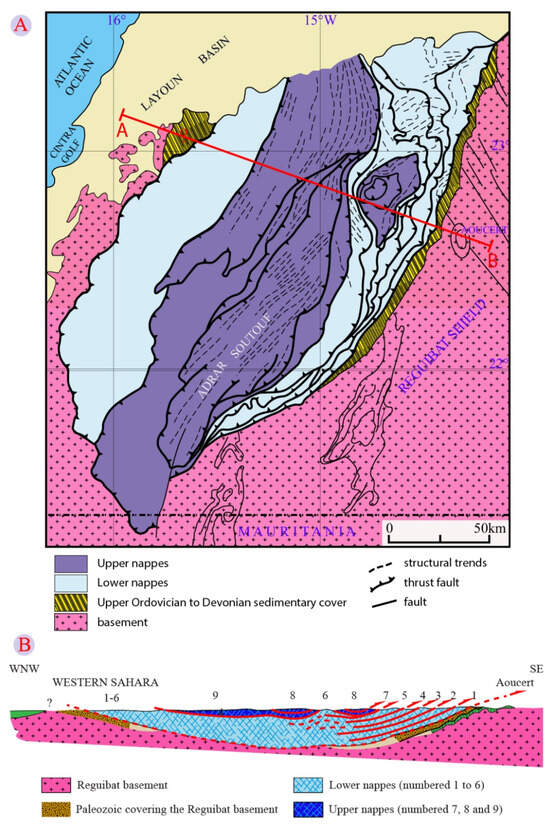

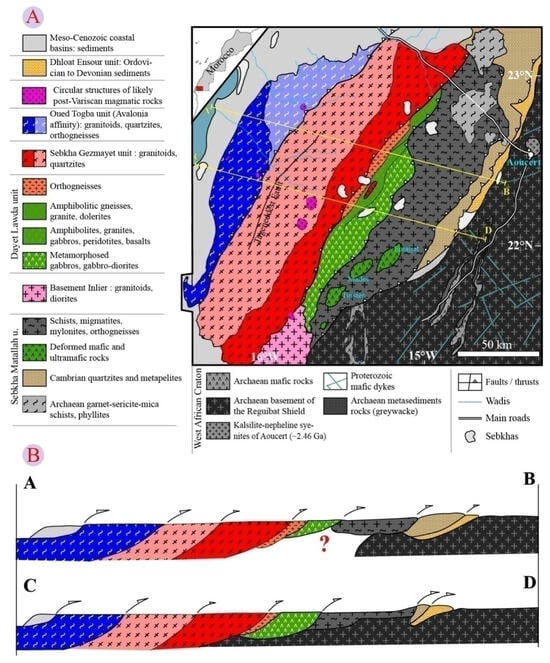

Shown in Figure 7 and identified in Figure 2, this large and controversial area has been studied by many geologists since 1949. Initial studies were conducted by the Spanish Geological Survey [3,4,5,6,7], which considered this massif as the western part of the Reguibat Shield, with remnants of Palaeozoic covers. Then, Sougy [34] proposed that this massif had been thrust over the Reguibat Shield and its thin Palaeozoic cover. Bronner et al. [8] interpreted aerial photographs and considered this metamorphic massif as a synformally folded stack of thrust sheets with gabbro thrust on top of the Reguibat basement and its Palaeozoic cover (Figure 7A,B). Le Goff et al. [35] discovered a Neoproterozoic basement associated with radiometric ages of Variscan metamorphic overprint. Villeneuve et al. [2,11] and Gärtner et al. [9,36] distinguished several units thought to have been stacked from the west to the east during the Carboniferous Variscan orogeny (Figure 8A,B) without evidence of “nappe synforms”. The eastern units (Sebkha Matallah and DayetLawda units, in Figure 8) are ascribed to the autochthonous Neoproterozoic belts reworked by the Variscan event [2]. Meanwhile, the western units (SebkaGezmayet and Oued Togba in Figure 8) are ascribed to exotic terranes likely related to the Appalachians or ophiolite fragments (with gabbros) or Rheic margin and thrusted over the previous autochthonous terranes [23,36,37]. U-Pb zircon ages and Ar-Armineral ages from successive stratigraphic units support this interpretation [23,37]. Bea et al. [10], according to new radiometric age determination, ascribed a part of the western units to the Reguibat Shield basement in contrast to Villeneuve et al. [2].

Figure 7.

(A) Sketch map of the Adrar Souttouf Massif after Bronner et al. [33]. (B) Geological section across the Adrar Souttouf Massif interpreted as a synform of “nappes” by Lecorché et al. [33]. Following this interpretation, eastern and western units shown in Figure 8 cannot be distinguished.

Figure 8.

(A) Geological scheme of the Adrar Souttouf Massif (modified from Gärtner et al. [9]) with location of cross-sections AB and CD in Figure 8A. (B) Schematic cross-sections AB and CD in the Adrar Souttouf Massif (modified from Gärtner et al. [36]). ?-in cross-section AB refer to a lack of information. This interpretation is strongly different from Figure 7.

Until now, there have been two end-member interpretations, but the study of the Landsat imagery (Figure 9a) shows that the two previous end-member interpretations are compatible (Figure 9b) if we consider the central black unit (of the Sebkha Matallah) as the thrusted “synform” of Bronner et al. [8], partially covered by thin and peculiar units. These units are related to those mapped in the field by Rjimati and Zemmouri [24] and Villeneuve et al. [11]. Thus, the outcrop of parts of the Reguibat basement in the fore-western units [10] is consistent with an incorporation of a basement sheet into the exotic pile during the course of the thrusting to the east during the late Variscan tectonic event. In other words, we are supposing that parts of the Reguibat basement are incorporated within the exotic units during their thrusting to the east.

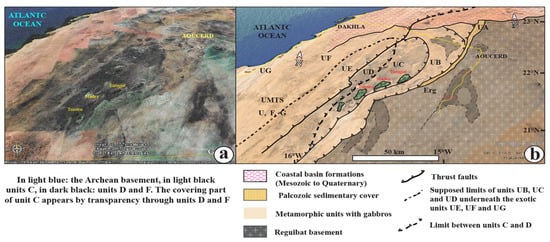

Figure 9.

(a) Adrar Souttouf Massif photographed from space (NASA photo). (b) New interpretation of the Adrar Souttouf Massif with the dark central gabbroic and metamorphic “nappe synforms” from African origin, which is covered by a thin grey unit of exotic origin (likely Appalachian). The African units (UB, UC and UD) which constitute the Adrar Souttouf lobe are covered by the allochthonous units (UE, UF and UG). These units are described in Villeneuve et al. [2].

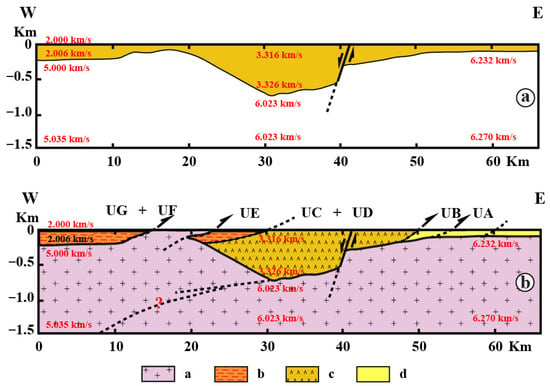

The seismic profile across the Adrar Souttouf Massif (Figure 10a) after Fateh [38] suggests that the central “gutter” (unit C in Figure 10b) could be interpreted as the stack of African units (“stacked nappe units”) partially buried beneath exotic units (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

(a): W-E seismic profile across the Adrar Souttouf Massif (Fateh [38]). (b) Geological interpretation of the seismic profile in Adrar Souttouf Massif. Legend: Allochthonous or exotic terranes (Units E, F and G), African terranes (Units B, C and D), Palaeozoic cover (Unit UA). a: Reguibat basement; b: allochthonous units; c: African units; d: Tindouf basin sediments.

The section displayed in Figure 10b could explain why some parts of the Reguibat basement could be matched with allochthonous units like UE, UF or UG during the Variscan tectonic event, in the western part of the massif, as hypothesized by Bea et al. [10].

4.3.2. Zemmour Massif and Dhlou–Sekkem Belt

The Zemmour area, located to the east of the Dhlou belt and studied by Sougy [25], corresponds to the western part of the Tindouf Basin and consists of a sedimentary succession ranging from Ediacaran limestones (Neoproterozoic to the Late Devonian), dated by their fossils. The Ghoul and Sekkem belts, located to the west, consist of parts of the Tindouf Basin sediments, folded, sheared and thrusted to the east over the western part of the Zemmour Massif. The DHLOU and Sekkem belts were studied by Dacheux [26], Rjimati and Zemmouri [24] and Belfoul [39]. The western part of these belts is concealed underneath the Palaeo- and Neogene sedimentary cover of the coastal basin.

4.3.3. Plage Blanche Belt (Located in Figure 2)

Recent works by Belfoul [39] and Soulaimani and Burkhard [40] extend the main Variscan Front Thrust (HFT), located in Figure 2 (in green line with triangular symbols), until “Plage Blanche” (northern Souttoufide), which is located to the west of the Anti-Atlas (AA in Figure 2). A W-E cross-section shows a succession of shales, quartzites and argillites (parts of the African margin) deformed and oriented from N-S to NE-SW with dipping to the West. These Ordovician sediments [2] exhibit many westward thrusts linked to the Variscan tectonic event [2]. According to Villeneuve et al. [2], this part belongs to an N-S Cadomian/Variscan belt, cross-cutting the E-W pan-African Anti-Atlas Belt in this area.

5. Structure of the Reguibat Impingement

5.1. Structure of the Mauritanian–Appalachian Fold Belts and the Reguibat Impingement

According to Figure 11, the main structural units are from east to west.

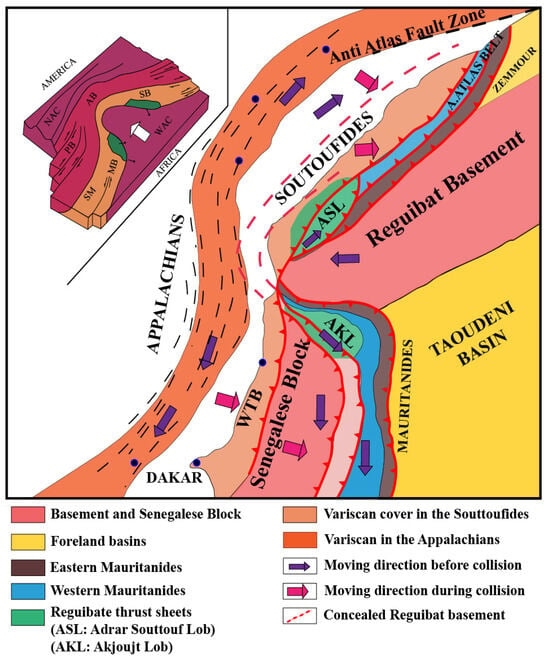

Figure 11.

Interpretation of the Reguibat Shield imprints within the Mauritanide (with central Mauritanides in blue) and Appalachian systems during the Variscan Orogeny and comparison with the impingement model of the craton (see in the cartoon, the comparison with the theoretical model shown in Figure 4). In light pink: the Agualilet and Wa-Wa belt. WTB- Western Thrust Belt which is an eastern counterpart of the Appalachians.

- The Reguibat basement (in red) covered by the sedimentary Tindouf (here represented by the Zemmour massif) and Taoudeni foreland basins with Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic formations (in yellow).

- The Variscan front thrust in the Mauritanides and Souttoufides with remnants of the Precambrian Belt (in brown).

- A central Unit (in blue) with remnants of Neoproterozoic and Early Palaeozoic belts with parts of ancient oceans.

- Two lobes of nappes on both sides of the Reguibat promontory: Adrar Souttouf lobe (ASL) and Akjoujt lobe (AKL) in green. AKL is partially covered by the early Palaeozoic Agualilet Belt (in light pink).

- The Senegalese Block (in dark pink).

- The exotic terranes (allochthonous units), which partially cover the northern lobe and are linked to the Western Thrust belt (WTB) to the west of the Senegalese Block (light orange).

- The Appalachian domain (dark orange).

5.2. Comparisons with the Previous Model

In summary, the evidence of a “lobe of nappes” in the Adrar Souttouf Massif and the movement of terranes in the Appalachians, as well as in the African belts, shows that the inferred Reguibat imprint model (Figure 11), which corresponds to the previous theoretical model of Lefort [12,13],has never been found in the field until now. The main difference between the two models lies in the asymmetry in the orientation of the lobes which are oriented NW-SE in the northern Mauritanides (to the south of the Reguibat promontory) and SSW-NNE to N-S in the Adrar Souttouf Massif (to the north of the Reguibat promontory). Meanwhile, they are symmetric in the model of Lefort (Figure 4). This discrepancy could be explained by the N-S-oriented shape of the western margin of the Reguibat Shield and the NNE-SSW orientation of the gutter in which the northern lobe (ASL) is infilled. The covering of the Adrar Souttouf lobe by the allochthonous units prevented the validation of similarities between the field observations and the theoretical model. Thus, the previous geological scheme of the Variscan assemblage between the Appalachians on the West African fold belts presented in Figure 2 (Villeneuve et al. [1]) should be modified.

6. Evolution of the Southern Variscan Belts During the Assembly of Pangea

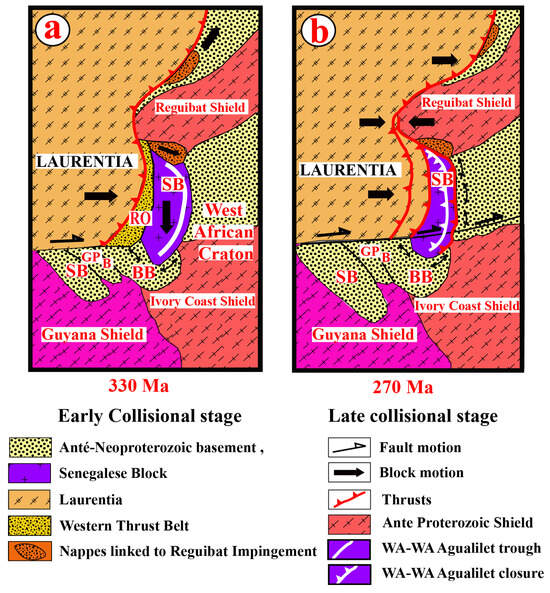

According to Figure 12, three main stages have been distinguished in this assembly process: a pre-collisional stage, a collisional stage and a post-collisional stage.

Figure 12.

(a,b) Two different stages of the collision between the Laurentia and the West African Craton during the last period of the Variscan Orogeny and after the tectonic escapes (modified from Villeneuve et al. [41]). SB—Suwannee (or Florida) Basin; GPB—Guinean Palaeozoic Basin; BB—Bové Basin; SB—Senegalese Block; RO—Rheic Ocean.

In a previous paper (Villeneuve et al. [41]), three stages were published instead of the two mentioned here.

6.1. The Main Collisional Stage (Figure 12a)

In this Early Carboniferous stage, the Rheic Ocean was already closed. To the north, the exotic terranes that are of WTB or peri-Gondwana origin are thrust over the western parts of the Adrar Souttouf “lobe”. Meanwhile, to the south, the Appalachian belts and the WTB were reunited according to the radiometric data on the samples from the Senegalese wells [42]. At this stage, the main strike-slip faults in the Appalachians may have been active.

6.2. The Post- (Or Late) Collisional Stage (Figure 12b)

At this stage (Early Permian), the WTB is thrust over the Senegalese Block, which, itself, is thrust onto the Mauritanide units and Taoudeni Basin. The Wa-Wa and the Agualilet Units were folded, and the Agualilet Unit already covered the southern part of the Akjoujt “lobe”. The southern Bissau–Kidira Fault Zone (BKKF in Figure 2) is extended from the Brunswick Fault (BF in Figure 2) to the Bissau–Kayes fault BKKF). This dextral strike-slip has separated the southern Koulountou part from the northern Wa-Wa/Agualilet belts. This stage could be related to a late collisional event.

The whole collisional process, which has a temporal range of more than 74 Ma (at least between 324 and 250 Ma according to radiometric dating in Villeneuve et al. [42]), is likely simplified at the current stage of knowledge and deserves to be enhanced by new geochronological and tectonic investigations.

7. Conclusions

After several decades of research and controversial debates, we are proposing a new hypothesis reconciling most of the previous interpretations by a superposition in the Adrar Souttouf lobes of African origin by a sheet of allochtonous (exotic) terranes (from Africa and America, including passive margins of the Rheic ocean). The thrusting of exotic terranes over the northern “lobe” hampers the recognition and correlation of features similar to the hitherto applied hypothetical model of imprinting. New geological and geochronological data (at least 45 new geochronological data) from the parts of the Adrar Souttouf lobe which are covering the Reguibat Shield allow us to reconstruct the promontory imprint. Our hypothesis is consistent with the currently available data. The total process of amalgamation of Laurentia with the West African Craton has lasted more than 74 Ma, perhaps 100 Ma. Owing to complex geometries of the West African and Laurentia margins with marginal blocks like the Senegalese Block and owing to the covering of the WTB by the Palaeogene to Neogene sedimentary successions in the Senegalo-Mauritanian basin, a complete reconstruction of the proposed processes is quite complicated. The main driver of these processes was the westward movement of the Reguibat Shield driven by plate tectonics, which imprinted the belt’s setting on the western tip of the craton.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.; Methodology, H.B. and N.Y.; Software, O.G.; Validation, A.G., A.E.A., A.A., H.B., P.A.M., P.M.N., N.Y., U.L. and M.C.; Formal analysis, N.Y. and U.L.; Investigation, M.V., O.G., A.G. and A.A.; Resources, O.G., A.G., A.E.A., A.A., H.B., P.A.M. and M.C.; Data curation, A.E.A. and H.B.; Writing—review & editing, M.V.; Visualization, P.M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the different geological surveys that supported our field investigations, such as the French BRGM, the Moroccan Geological Survey, the Mauritanian Geological Survey and the Senegalese Geological Survey. We also acknowledge the laboratories that provided a lot of consistent geochronological data, such as the Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden (Germany), Florida University (USA) and Brest University (France). The three reviewers are thanked for their recommendations, which have improved this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Villeneuve, M.; Cornée, J.; Muller, J. Orogenic belts, sutures and blocks faulting on the northwestern Gondwana margin. In Proceedings of the Gondwana Eight, Hobart, Australia, 24–28 June 1991; Findlay, R.H., Unrug, R., Banks, M.R., Veevers, J.J., Eds.; A. A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, M.; Gärtner, A.; Youbi, N.; El Archi, A.; Vernhet, E.; Rjimati, E.-C.; Linnemann, U.; Bellon, H.; Gerdes, A.; Guillou, O.; et al. The southern and central parts of the “Souttoufide” belt, Northwest Africa. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2015, 112, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alia Médina, M. El Sahara Español, 2epart: Estudio Geologicó; Instituto de Estudios Africanos: Madrid, Spain, 1949; pp. 201–404. [Google Scholar]

- Alía Medina, M. Esquema Geológico del Sahara Español; Instituto de Estudios Africanos: Madrid, Spain, 1958; 52p. [Google Scholar]

- De La Vina, D.J.; Cabezon, D.C. Mapa Geológicodel Sahara Español y Zonas Limotrofes; Scale 1:500,000; Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Madrid, Spain, 1958; 15p. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas, A. Las formaciones metamórficas del Sahara español y sus relaciones con el Precámbrico de otras regions africanas. In Proceedings of the Report 21th International Geological Congress Norden (1959), Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–25 August 1960; Volume 9, pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas, A. El Precámbricodel Sahara español y sus relaciones con las seriessedimentariasmás modernas. Bolet. Geol. Minero Madrid 1968, 79, 445–480. [Google Scholar]

- Bronner, G.; Marchand, J.; Sougy, J. Structure en synclinal de nappes des Mauritanides septentrionales (Adrar Souttouf, Sahara occidental) Abstract 12th Colloquium on African Geology; Musée Royal d’Afrique centrale (MRAC): Bruxelles, Belgium, 1983; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner, A.; Villeneuve, M.; Linnemann, U.; El Archi, A.; Bellon, H. An exotic terrane of Laurussian affinity in the Mauritanides and Souttoufides (Moroccan Sahara). Gondwana Res. 2013, 24, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bea, F.; Montero, B.; Haissen, F.; Molina, J.F.; Lodeiro, F.G.; Mouttaqui, A.; Kuiper, Y.D.; Chaib, M. The Archean to Late-Paleozoic architecture of OuladDlim Massif, the main Gondwanan indenter during the collision with Laurentia. Earth Sci. Rev. 2020, 208, 150–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, M.; Bellon, H.; El Archi, A.; Sahabi, M.; Rehault, J.P.; Olivet, J.L.; Aghzer, A.M. Evènements panafricains dans l’Adrar Souttouf (Sahara Marocain). CR Géosci. 2006, 338, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, J.P. Imprint of the Reguibat Uplift (Mauritania) onto the central and southern Appalachians of the U.S.A. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 1988, 7, 433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Lefort, J.P. Basement Correlation Across the North Atlantic; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1989; 148p. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, J.P.; Van Staal, C.R.; Rankin, D.W.; Williams, H. Lithotectonic Map of the Appalachian Orogen, Canada and United States of America; GSA: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, L., III; Speer, J.A.; Russel, G.S.; Ferrar, S.S. Ages of regional metamorphism and ductile deformation in the central and southern Appalachians. Lithos 1983, 16, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Hatcher, R.D., Jr.; Hatcher, R.D., Jr. Appalachian Suspect Terranes. In Contributions to the Tectonics and Geophysics of Mountain Chains; Hatcher, R.D., Jr., Williams, H., Zietz, I., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1983; Volume 158, pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, R.D. Tectonics of the Southern and Central Appalachian Internides. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1987, 15, 337–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.C. Late Paleozoic Strike-Slip Tectonics of the Northern Appalachians. Ph.D. Thesis, State University of New-York, New York, NY, USA, 1984; 231p. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.B.; Keppie, J.D.; Nance, R.D. Fault reactivation within Avalonia: Plate margin to continental interior deformation. Tectonophysics 1999, 305, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, J.W.F.; Barr, S.M.; Park, A.F.; White, C.E.; Hibbard, J. Late Paleozoic strike-slip faults in Maritime Canada and their role in the reconfiguration of the northern Appalachian orogen. Tectonics 2015, 34, 1661–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppie, J.; Keppie, D.F.; Dostal, J. The northern Appalachian terrane wreck model. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2021, 58, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecorché, J.P. Structure of the Mauritanides. In Regional Trends in the Geology of the Appalachian-Caledonian-Hercynian-Mauritanide Orogen; Schenk, P.E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 347–353. [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner, A.; Youbi, N.; Villeneuve, M.; Linnemann, U.; Sagawe, A.; Hofmann, M.; Zieger, J.; Mahmoudi, A.; Boumehdi, M.A. Palaeogeographic implications from the sediments of the Sebkha Gezmayet unit of the Adrar Souttouf Massif (Moroccan Sahara). CR Geosci. 2018, 350, 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Rjimati, E.; Zemmouri, A. Carte Géologique du Maroc au 1/100,000. Feuille de Smara, Notice Explicative. In Notes Mémoires du Service Géologique Maroc; Le Service Géologique du Maroc: Rabat, Maroc, 2020; Volume 438 bis, 52p. [Google Scholar]

- Sougy, J. Les formations paléozoïques du Zemmour noir (Mauritanie septentrionale): Étude stratigraphique, pétrographique et paléontologique. Ann. Fac Sci. Univ. Dakar 1964, 12, 695. [Google Scholar]

- Dacheux, A. Etude Photogéologique de la Chaine du Dhlou (Zemmour-Mauritanie Septentrionale); Laboratoire de Géologie, Université de Dakar: Dakar, Senegal, 1967; Volume 22, pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Teissier, F.; Dars, R.; Sougy, J. Mise en évidence de charriages dans la série d’Akjoujt (RIM). CR Acad. Sci. Paris 1961, 252, 1186–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Sougy, J. West African fold belt. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1962, 73, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.C.; O’Sullivan, P.; Cosca, M.A.; Motts, H.A.; Horton, J.D.; Taylor, C.D.; Beaudoin, G.; Lee, G.K.; Ramezani, J.; Bradley, D.B.; et al. Synthesis of geological, structural, and geochronologic data (Phase V, Deliverable 53). Chapter A. In Second Projet de Renforcement Institutionnel du Secteur Minier de la République Islamique de Mauritanie (PRISM-II); Taylor, C.D., Ed.; U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report: Denver, CO, USA, 2015; 328p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, J.; Strikland, C. Stratigraphy, structure and mineralisation of the Akjoujt area (Mauritania). J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2004, 38, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitfield, P.E.J.; Key, R.M.; Waters, C.N.; Hawkins, M.P.H.; Schofield, D.I.; Loughlin, S.; Barnes, R.P. Notice explicative des cartes géologiques et gîtologiques à 1/200 000 et 1/500 000 du Sud de la Mauritanie. In Volume 1—Géologie: DMG; Ministère des Mines et de l’Industrie: Nouakchott, Mauritania, 2004; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mattauer, M. Réflexions sur l’excursion en Mauritanie de Décembre 1963. Inédit 1964, 1, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lecorché, J.P.; Bronner, G.; Dallmeyer, R.D.; Rocci, G.; Roussel, J. The Mauritanide Orogen and Its Northern extensions (Western Sahara and Zemmour), West Africa. In The West African Orogens and Circum-Atlantic Correlatives; Springer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1991; pp. 187–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sougy, J. Les Formations Paléozoïques du Zemmour noir (Mauritanie Septentrionale): Étude Stratigraphique, Pétrographique et Paléontologique. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Nancy, Nancy, France, 1961; 680p. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff, C.; Guerrot, C.; Maurin, G.; Johan, V.; Tegyey, M.; Ben Zarga, M. Découverte d’éclogites hercyniennes dans la chaîne septentrionale des Mauritanides (Afrique de l’Ouest). Comptes Rendus Acad. Sci. Ser. IIA-Earth Planet. Sci. 2001, 333, 711–718. [Google Scholar]

- ärtner, A.; Villeneuve, M.; Linnemann, U.; Gerdes, A.; Youbi, N.; Guillou, O.; Rjimati, E.C. History of the West African Neoproterozoic Ocean: Key to the geotectonic history of circum-Atlantic Peri-Gondwana (Adrar Souttouf Massif, Moroccan Sahara). Gondwana Res. 2016, 29, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ärtner, A. Geologic Evolution of the Adrar Souttouf Massif (Moroccan Sahara) and its Significance for Continental-Scaled Plate Reconstructions Since the Mid Neoproterozoic. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany, 2017; 310p. [Google Scholar]

- Fateh, B. Modélisation de la Propagation des Ondes Sismiques dans les Milieux Visco-Elastiques: Application a la Détermination de L’atténuation des Milieux Sédimentaires. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, French, 2008; p. 181. [Google Scholar]

- Belfoul, M.A. Cinématique de la Deformation Hercynienne et Geodynamique Paleozoique dans l’Anti-Atlas sud Occidental et le Sahara Marocain. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Ibn Zor, Agadir, Maroc, 2005; 379p. [Google Scholar]

- Soulaimani, A.; Burkhard, M. The Anti-Atlas chain (Morocco): The southern margin of the Variscan belt along the edge of the West African craton. In The Boundaries of the West African Craton; Ennih, N., Liégeois, J.P., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2008; Volume 297, pp. 433–452. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, M.; Gärtner, A.; Mueller, P.A.; Guillou, O.; Linnemann, U. Colliding cratons: Linking the Variscan orogeny in West Africa and North America. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2024, 542, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, M.; Bellon, H.; Guillou, O.; Gärtner, A.; Mueller, P.A.; Heatherington, A.L.; Ndiaye, P.M.; Theveniaut, H.; Corsini, M.; Linnemann, U.; et al. Evolution of the West African Belts: Review, new geochronological data, new correlations and new geodynamic hypothesis. J. Afr. Earth. Sci. 2025, 223, 105484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.