Abstract

This study presents stratigraphic and structure findings from the southeastern Bannu Basin, a structurally complex segment of the Sub-Himalayan foreland in Pakistan. Two dimensional seismic reflection data were integrated with well-log data from the Chonai-01 and Marwat-01 wells to reconstruct the subsurface basin architecture and to evaluate its hydrocarbon potential. In general, the deformation in the region is strongly controlled by the Neoproterozoic Salt Range Formation, with salt tectonics generating anticlines, deep salt detachment, and fault systems that form favorable structural traps. Seismic interpretation reveals both normal and reverse faulting, and multiple unconformities, indicating episodic tectonic activity linked to Himalayan orogeny. Well correlation of individual formations highlights lateral stratigraphic variations, including thick Siwalik Group deposits and key reservoir units such as the Datta and Lumshiwal formations. These findings demonstrate that mild salt-related deformation and stratigraphic discontinuities play a central role in hydrocarbon migration and entrapment. The structural and stratigraphic similarity of the Bannu Basin to the Potwar Plateau underscores its significant exploration potential within the Himalayan foreland system, while the integrated seismic–well workflow provides a robust framework for future exploration.

1. Introduction

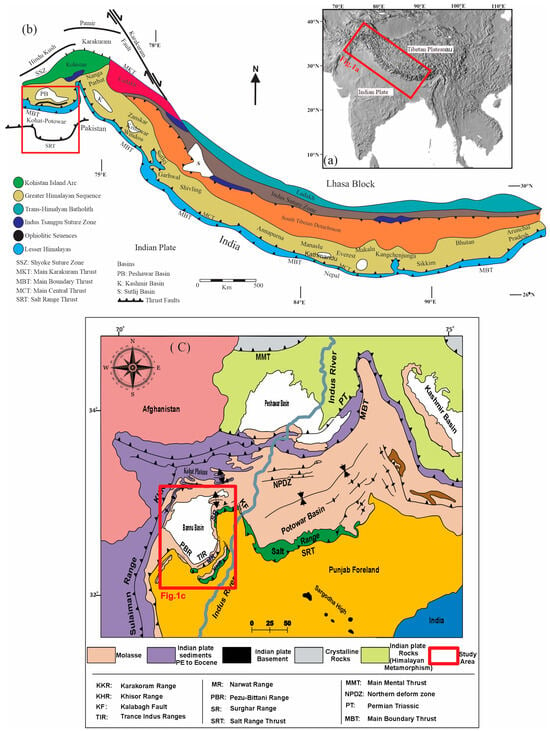

The term Himalaya, meaning “abode of snow”, refers to the world’s largest, highest, and youngest orogenic belt [1]. The Himalayan orogen is approximately 230–350 km wide and extends for more than 2300 km [2]. Its northwestern extent reaches the Nanga Parbat Syntaxis in Pakistan, while the southeastern termination lies at the Namche-Barwa Syntaxis in Tibet (Figure 1a) [3,4,5]. The Himalaya formed as a result of the continent–continent collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates during the Eocene, with collision ages estimated between ~70 and ~25 Ma. This tectonic convergence produced one of the largest known orogenic systems on Earth [6,7,8,9,10] (Figure 1b). Understanding the physical processes governing crustal deformation and the impact of this mountain-building event is fundamental for evaluating petroleum systems in Pakistan [8,11,12,13].

The Bannu Basin occupies the northwestern part of the Himalayan foreland basin system in Pakistan [14]. Together with the Marwat and Surghar Ranges and the Bannu Basin–Khisor Ranges, it forms part of the tectonically active fold-and-thrust belt known as the Trans-Indus Ranges (Figure 1c) [15,16]. Globally, foreland basins associated with fold-and-thrust belts are regarded as prime hydrocarbon provinces due to their complex structural traps and thick sedimentary successions [17,18]. The Bannu Basin has undergone intense thrust and strike-slip deformation and is filled with thick clastic molasse deposits, reaching an estimated thickness of ~5 km [19]. Structurally, the basin comprises three principal domains, bounded by thrust zones to the north and south and a central foredeep forming the basin core. The basin consists of a sedimentary wedge transported in a northwest–southeast direction along a mechanically weak salt detachment horizon. Structurally and stratigraphically, the Bannu Basin represents the western extension of the Potwar Basin and lies adjacent to the Kohat Basin [20]. Numerous hydrocarbon fields, including the Mela, Nashpa, and Chanda oil fields, have been discovered within these basins [21]. Despite extensive drilling in the Bannu Basin since the first Pezu-01 well in 1968, no major commercial discoveries were reported until 2021 [22].

Figure 1.

Regional tectonic setting of the Himalayan–Karakoram–Hindukush orogenic system showing (a) the location of the Himalayan belt within the India–Eurasia collision zone, (b) major tectonic blocks, thrust systems (MCT, MBT, HFT), and structural domains along the Himalayan arc, modified after [15] and (c) the regional structural framework of northwestern Pakistan highlighting the Bannu Basin, adjacent basins, major thrusts (MMT, SRT, NPDZ), and surrounding mountain ranges. The red box indicates the study area modified after [23].

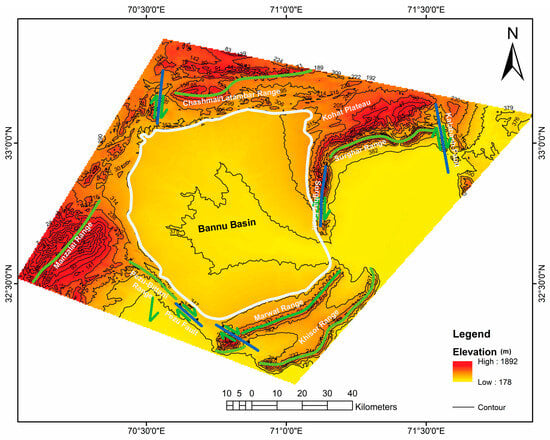

Seismic exploration plays a fundamental role in constructing geological models of subsurface formations, hydrocarbon migration pathways, and structural traps [24]. The primary objective of seismic interpretation is to characterize both the static and dynamic properties of subsurface reservoirs by resolving structural features such as horizon geometry, reservoir depth, fault distribution, and stratigraphic architecture, as well as petrophysical properties including porosity and permeability [25,26]. Seismic interpretation and geohistory modeling reveal enhanced sedimentation rates and episodic rapid deposition from the Miocene to the present, attributed primarily to Himalayan orogenic uplift [1,27,28]. Depth-domain horizon modeling is particularly effective for delineating the present-day basin architecture, including tectonic evolution, depositional systems, and the physical attributes of individual stratigraphic horizons [29]. In the Bannu Basin, prospective hydrocarbon traps are predominantly structural and are commonly associated with anticlines [15]. Quaternary sandy and alluvial deposits dominate the surface geology of the basin, while more extensive bedrock outcrops are exposed along the Surghar, Khisor, and Pezu–Bhittani Ranges (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Digital elevation model and structural map of the Bannu Basin showing the surrounding mountain ranges (Surghar, Marwat, Khisor, Chashmai-atambar, and Manzalai ranges), major fault systems, and basin outline. Elevation is represented by color shading with superimposed contour lines.

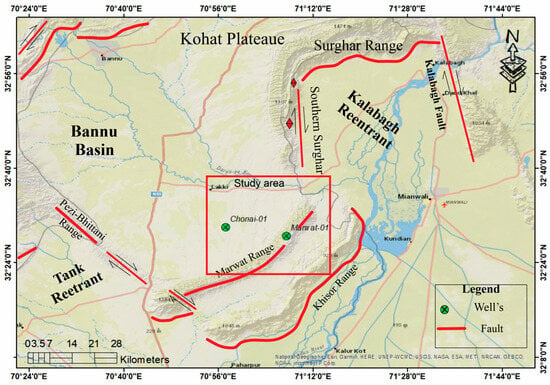

By integrating 2D seismic interpretation with well data analysis, this study addresses critical challenges in hydrocarbon exploration within the Bannu Basin. Incomplete structural characterization has been a major limitation of earlier investigations, restricting reliable delineation of prospective hydrocarbon pay zones. This limitation is overcome here by utilizing recently released seismic and well datasets covering the southeastern Bannu Basin and the adjacent Marwat and Khisor Ranges. Data from the Chonai-01 and Marwat-01 wells, drilled in 1990 and 1970, respectively, are incorporated to refine subsurface interpretation (Figure 3). This integrated approach provides new insights into the structural framework and deformation style of the fold-and-thrust belt, which play a key role in controlling petroleum system development.

Figure 3.

Location map of the study area within the southeastern Bannu Basin showing the major structural elements (Pezu–Bhittani, Marwat, Surghar, and Khisor ranges), regional thrusts and reentrants, the positions of the Chonai-01 and Marwat-01 wells.

2. Geological and Structural Framework

Prior to the India–Eurasia continental collision, the Bannu Basin evolved as a passive-margin basin underlain by the Precambrian Salt Range Formation [30,31]. The onset of compressional stresses associated with the Himalayan orogeny caused significant crustal uplift and triggered rapid deposition of fluvial sediments of the Rawalpindi Group and Siwalik formations, derived predominantly from the northern part of the basin. This accelerated sediment loading likely promoted the mobilization of the underlying salt, inducing its migration within the basin. Furthermore, the prevailing compressional tectonic regime is interpreted to have activated the main regional detachment horizon, represented by Precambrian Salt Range Formation at the base of the basin.

This phase of compressional tectonism led to the development of widespread folds and thrust faults, resulting in the deformation of the entire sedimentary succession within the basin [32]. At present, thick molasse deposits dominate the northern and central parts of the basin and gradually thin southward. Ongoing tectonic activity and salt diapirism have played a critical role in the vertical displacement of rock units in the southern part of the basin, shaping the present-day structural configuration [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

2.1. Stratigraphy

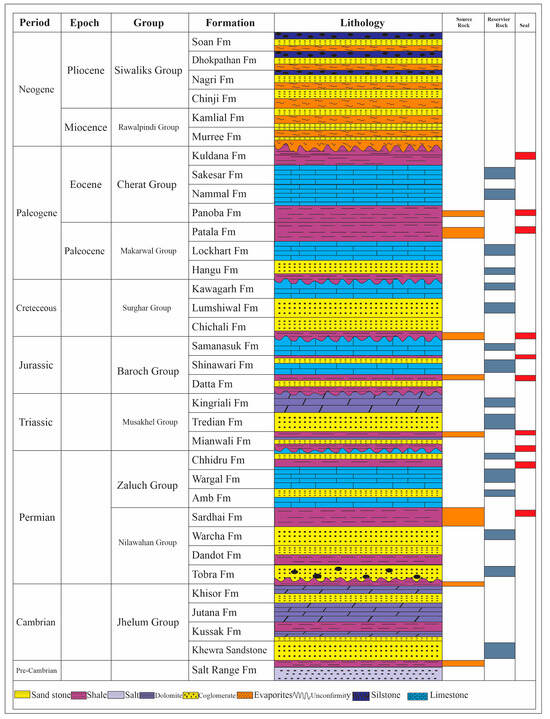

The stratigraphic succession of the Bannu Basin extends from the Neoproterozoic to the Pleistocene and records the transition from a stable cratonic margin to a flexural foreland basin related to Himalayan convergence [13]. The basin fill consists of a thick sedimentary package dominated by evaporites at the base, overlain by alternating siliciclastic and carbonate successions of Cambrian to Paleogene age, and capped by Neogene–Quaternary molasse. These units collectively provide the essential elements of the petroleum system, including regional detachment horizons, potential source intervals, reservoir packages, and effective seals (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Generalized stratigraphic column of the Bannu Basin from the Precambrian to the Neogene, showing major groups, formations, and representative lithologies. Key petroleum system elements (source, reservoir, and seal) are also indicated, with the Precambrian Salt Range Formation acting as the regional detachment horizon [21].

2.1.1. Lithostratigraphy of the Neoproterozoic Salt Range Formation

The stratigraphic column is underlain by the Neoproterozoic Salt Range Formation, which consists primarily of halite and other evaporitic facies, with subordinate dolomite, marl, and reddish clastics. This thick evaporite sequence forms the regional décollement level throughout the basin and exerts a first-order control on the style of deformation, facilitating detachment folding, thrusting, and salt diapirism. The Salt Range Formation also acts as an efficient seal and barrier to fluid flow, isolating the overlying Paleozoic–Mesozoic succession from the crystalline basement. An angular unconformity commonly separates the Salt Range Formation from the overlying Cambrian Jhelum Group, marking a major tectono-stratigraphic break.

2.1.2. Cambrian Lithostratigraphic Units

Overlying the Precambrian Salt Range Formation, the Cambrian Jhelum Group comprises the Khewra Sandstone, Kussak, Jutana, and Khisor formations. This succession is dominated by shallow-marine sandstones, siltstones, shales, and dolomitic limestones, reflecting deposition on a stable continental shelf. The Khewra Sandstone and Jutana Formation locally exhibit good reservoir properties due to their relatively high porosity and permeability, while associated shales and dolomites provide effective intra-formational seals.

2.1.3. Permian–Eocene Lithostratigraphic Units

The Permian succession in the Bannu Basin is represented by the Nilawahan and Zaluch groups, which together form an important part of the regional petroleum system (Figure 4). The Nilawahan Group is characterized by glacial to fluvial sandstones, shales, and coal-bearing intervals, reflecting a transition from glacio-fluvial to shallow-marine depositional environments. The overlying Zaluch Group is dominated by shallow-marine limestones, dolomites, and subordinate shales, representing a stable carbonate platform setting. Organic-rich shales within the Sardhai and Chhidru formations, together with porous carbonate units of the Wargal and Amb formations, provide important source and reservoir rock combinations within the Permian section.

The Triassic to Cretaceous succession in the Bannu Basin comprises the Musakhel, Baroch, and Surghar groups. The Triassic Musakhel Group consists of mixed carbonates, sandstones, and shales deposited in shallow-marine to marginal-marine settings. The Jurassic Baroch Group includes the Datta Sandstone, a major clastic reservoir unit, and the Samana Suk Formation, a regionally extensive carbonate reservoir. The Cretaceous Surghar Group is dominated by marine shales and sandstones, with the Chichali Formation acting as a potential secondary source rock and the Lumshiwal Formation providing local reservoir sandstones.

The Paleocene–Eocene succession is represented by the Makarwal and Cherat groups, recording a transition from restricted shallow-marine to open-marine depositional conditions. The Hangu Formation consists mainly of sandstones with good reservoir characteristics, while the Lockhart Formation is composed predominantly of limestones forming regionally extensive carbonate reservoirs. The Patala Formation is composed mainly of organic-rich shales with interbedded sandstones, functioning as both an important regional source rock and seal. The overlying Eocene Cherat Group is dominated by thick carbonate successions with intercalated shales, forming laterally continuous reservoir–seal couplets. Collectively, the Permian–Eocene stratigraphic interval constitutes the principal source, reservoir and seal framework for conventional hydrocarbon accumulations in the Bannu Basin and the adjacent Himalayan foreland basins.

2.1.4. Miocene–Pliocene Lithostratigraphic Units

The uppermost part of the stratigraphic succession in the Bannu Basin is represented by the Miocene–Pliocene molasse deposits associated with Himalayan uplift. This interval comprises the Rawalpindi Group and the overlying Siwalik Group, which consist predominantly of thick fluvial successions of sandstones, siltstones, conglomerates, and mudstones. These syn-orogenic clastics record phases of rapid hinterland erosion and progressive foreland basin subsidence during the late stages of Himalayan orogenesis.

Although these Miocene–Pliocene units primarily act as a cover sequence, they may locally host shallow gas accumulations or secondary reservoirs, particularly where sand-rich channel bodies are preserved and structurally or stratigraphically trapped. Their substantial thickness also plays a key role in basin loading, thereby influencing salt mobilization and the structural evolution of overlying sedimentary successions above the Precambrian Salt Range Formation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Work Flow

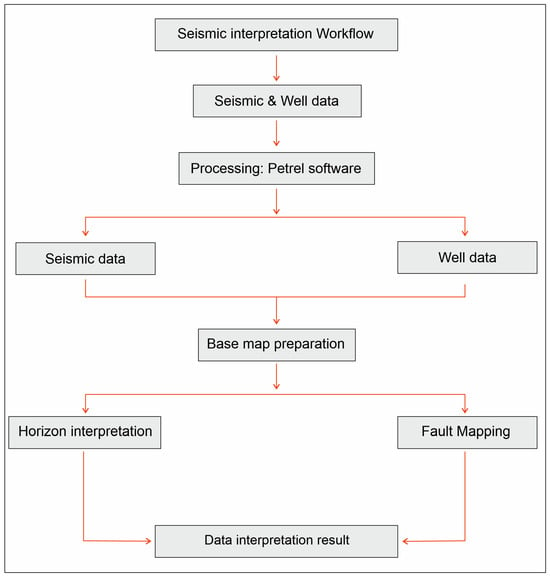

The seismic interpretation workflow adopted in this study is summarized in Figure 5 and involved a sequential process of data loading, quality control, seismic–well correlation, horizon interpretation, fault mapping, and structural integration. All seismic and well data were processed and interpreted using Petrel by Schlumberger software, licensed to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Oil and Gas Company Limited (KPOGCL). This platform was used for seismic visualization, horizon and fault picking, and structural modeling.

Figure 5.

Workflow for seismic data and well data interpretation.

Following data loading, an initial data quality assessment was carried out to evaluate reflector continuity, signal-to-noise ratio, and structural clarity across all seismic profiles. A base map was constructed using the interpreted seismic line locations and well control to establish the regional structural framework (Figure 2). Seismic reflectors were then manually traced on each seismic line using a consistent picking strategy to ensure lateral continuity and stratigraphic consistency across intersecting profiles.

Fault interpretation was performed by identifying reflector terminations, offsets, and abrupt changes in dip. Fault surfaces were tracked along strike by correlating displacement patterns across intersecting seismic lines. Finally, interpreted horizons and faults were integrated to generate a coherent structural and stratigraphic model of the study area.

3.2. Seismic and Well Data Acquisition

This study utilized 2D time-migrated seismic reflection data acquired by the Oil and Gas Development Company Limited (OGDCL) in the southeastern Bannu Basin during 1978–1979. The dataset was obtained from LMKR Resources Pvt. Ltd. The seismic profiles, including lines 784-BU-01, 794-BU-13, 794-BU-14, and 794-BU-15, vary from poor to fair quality due to legacy acquisition parameters and surface conditions.

The seismic sections were interpreted in a two-way travel time (TWT) domain. No reprocessing was performed; thus, the study relied on post-stack time-migrated sections provided by the data vendor. Interpretation uncertainty related to data quality was accounted for by emphasizing only laterally continuous, high-confidence reflectors. Two exploratory wells, Chonai-01 and Marwat-01, were used for stratigraphic calibration. Available well datasets (GR, Porosity, Resistivity, Density log) were used to perform to identify subsurface faults and horizons within the study area, enabling the reconstruction of the reservoir geometry and structural configuration.

3.3. Seismic to Well Tie and Time to Depth Calibration

Seismic–well tie analysis was performed to correlate well stratigraphy with seismic reflection events. No checkshots or VSP data were available for the Chonai-01 and Marwat-01 wells; therefore, time to depth calibration was based on available sonic log data and standard regional velocity functions from the Bannu, Kohat and Potwar foreland basin. Interval velocities were obtained by integrating slowness values, while missing intervals were constrained using lithology and formation tops. Synthetic seismograms were generated from available sonic and density logs using a zero-phase Ricker wavelet and matched to nearby seismic traces through manual waveform matching and cross-correlation. Although the lack of checkshots data introduces uncertainty in absolute depth conversion, the method provides a geologically consistent relative calibration suitable for regional structural interpretation.

3.4. Seismic Horizon Interpretation

Key stratigraphic horizons were interpreted based on Seismic reflection continuity, amplitude characteristics, tied formation tops, and regional stratigraphic knowledge. Horizon picking was carried out manually at every 5–10 traces, depending on reflector continuity. Where signal quality deteriorated, horizon interpolation was constrained using adjacent intersecting seismic lines. Misties between intersecting profiles were minimized through repeated loop-tying and vertical time shifting. Only reflectors that could be confidently traced across multiple seismic lines were used to minimize interpretational uncertainty.

3.5. Fault Interpretation and Structural Mapping

Faults were identified based on vertical and lateral offsets of reflectors, Abrupt reflector terminations, Disrupted reflection continuity and systematic changes in dip along interpreted horizons. Fault interpretation was performed manually using vertical exaggeration and zoomed visualization to enhance subtle displacement detection. Fault planes were interpreted in the time domain. Only faults exhibiting consistent displacement across multiple horizons were included in the final structural model.

4. Results

4.1. Seismic Data

Moreover, syn-tectonic sediment thickening adjacent to major faults and salt-related uplifts indicates favorable conditions for hydrocarbon migration and trapping. The spatial coincidence of structural highs with established petroleum systems in adjacent basins (e.g., Kohat and Potwar basins) further strengthens the exploration potential of the area. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the southeastern Bannu Basin represents a highly prospective exploration target, with significant implications for future drilling and petroleum system development [15]. The seismic–well integration enabled the identification of gentle anticlines and fault geometries, which together control the development of potential structural traps and affect key elements of the petroleum system within the basin.

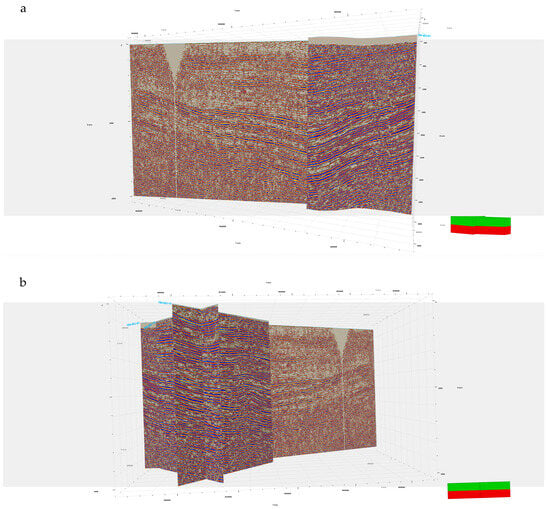

The fence diagram produced by utilizing seismic data in this study further reveals syn-tectonic thickness changes in strata adjacent to major faults and salt-related uplifts, expressed as progressive layer thickening, onlaps of the seismic reflectors and thinning and reflector divergence away from the structural highs (Figure 6). These geometries indicate that the sedimentation was active during the deformation phase, which reflected orogenic loading and formation of the foreland basin in front of the forming Himalaya mountain.

Figure 6.

(a,b) 2D seismic displayed from two different viewing directions to highlight the internal reflector geometry. Both views represent the same dataset, visualized from opposite perspectives to better illustrate the lateral continuity and gentle structural variations in the seismic reflections. For location, see (Figure 3).

In addition, localized angular discordances between older deformed reflectors and overlying sub-horizontal strata are observed, marking angular unconformities that bracket distinct deformation episodes. These relationships allow the timing of deformation to be constrained between the deposition of older tilted successions and younger undeformed units.

Interpretation of the 2D seismic profiles 794-BU-13 and 784-BU-01, tied to the Marwat-01 and Chonai-01 wells, respectively, reveals a set of laterally continuous but structurally deformed reflectors affected by faulting and folding. Despite the fair-to-poor quality of the legacy seismic data (acquired during 1978–1979), the profiles provide sufficient structural control for regional interpretation.

Seismic well integration enabled reliable horizon positioning and the identification of fault-bounded folds and folded structures that form potential hydrocarbon traps. Although 3D seismic data would offer higher resolution, the available 2D lines adequately delineate the major subsurface structural framework and prospective drilling targets across the study area.

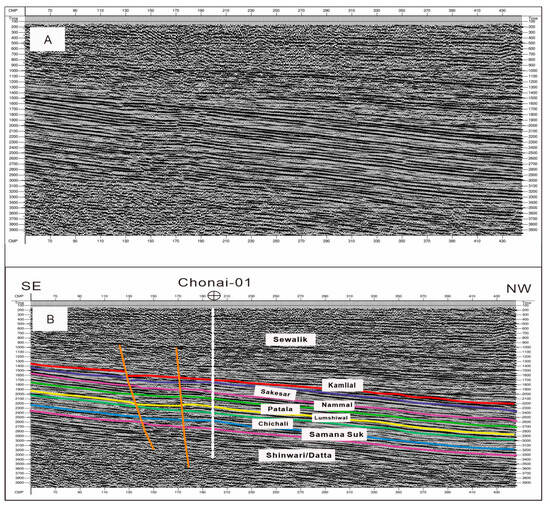

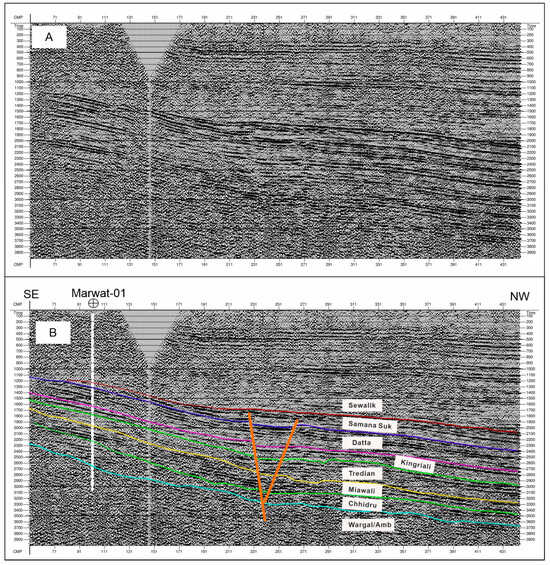

In general, seismic interpretation focuses on the identification of folds, faults, anticlines, and synclines, which play a key role in hydrocarbon migration and trapping. Structural trap geometry depends on the prevailing tectonic regime, with compressional settings dominated by thrust and reverse faults and extensional settings characterized by normal faults and tilted blocks. In this study, normal faults were identified near the Chonai-01 well on seismic lines 784-BU-01 (Figure 7) and 794-BU-13 (Figure 8), while both normal and reverse faults occur on line 794-BU-14 (Figure 9). No significant faults were observed on line 794-BU-15 (Figure 10). These structures define the main migration pathways and folding configurations in the study area.

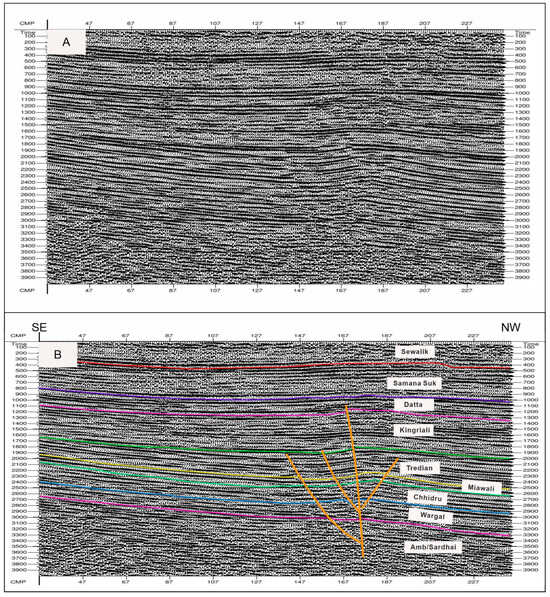

Figure 7.

Shows the uninterpreted (A) and interpreted (B) SE–NW trending seismic profile crossing the Chonai-01 well. The seismic reflections are mostly sub-parallel and laterally continuous, indicating gentle deformation and a structurally stable basin center. No evidence of salt diapirism or chaotic reflection patterns is observed along this line. The interpreted section outlines the major stratigraphic units, including the Siwalik, Kamlial, Sakesar, Patala, Chichali, Lumshiwal, Samana Suk, and Shinwari/Datta formations, which show a gentle regional dip toward the northwest. A set of minor normal faults is observed near the Chonai-01 well, indicating localized extensional deformation with limited structural impact.

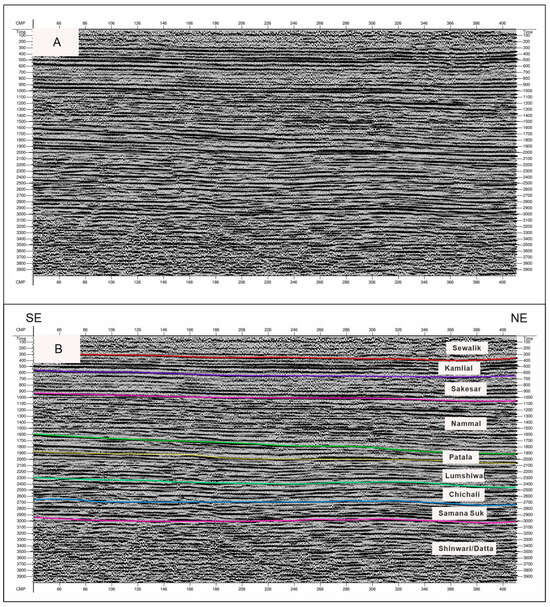

Figure 8.

Presents the uninterpreted (A) and interpreted (B) SE–NW seismic profile crossing the Marwat-01 well. The Siwalik Formation shows clear onlap geometry toward the southeast, indicating progressive uplift of the Marwat Range during late-stage deposition. The Samana Suk Formation thins toward the SE (Marwat Range) and thickens toward the NW, consistent with the basinward deepening described in the introduction. A very gentle anticline is observed at the location of the Marwat Range, and the Marwat-01 well penetrates the crest of this structural ridge. The overall deformation is mild; however, the structural style suggests that the core of the ridge may be influenced by deep-seated ductile material, possibly salt, although no direct salt diapir is imaged on the seismic section.

Figure 9.

Shows the uninterpreted (A) and interpreted (B) SE–NW seismic profile. The stratigraphic units, including the Siwalik, Samana Suk, Datta, Kingriali, Tredian, Miawali, Chhidru, Wargal, and Amb/Sardhai formations, display generally continuous reflectors with gentle regional dip. A set of normal faults is observed in the central part of the profile. Importantly, the thicknesses of individual stratigraphic units remain nearly uniform across the faulted blocks, indicating that these faults developed after sediment deposition. This geometric relationship suggests that the observed deformation is post-depositional in nature, likely related to later tectonic reactivation rather than syn-depositional growth faulting.

Figure 10.

Shows the uninterpreted (A) and interpreted (B) SE–NE seismic profile. The stratigraphic units from Siwalik to Shinwari/Datta formations are laterally continuous and display mostly flat-lying reflectors, indicating a tectonically stable setting. A gentle undulation is observed within the Patala Formation, suggesting mild post-depositional deformation at this level. In contrast, the overlying formations exhibit completely flat and undeformed strata, indicating that no significant tectonic activity affected the upper sedimentary sequence after deposition. The overall geometry confirms very low structural deformation along this seismic line.

4.2. Well Data

One of the key outcomes of this study is the integration of well data (Table 1 and Table 2) with 2D seismic data, which constrains the regional structural framework, structural development and hydrocarbon migration pathways (Figure 11).

Table 1.

Table showing complete stratigraphy of Chonai-01 Well.

Table 2.

Table showing complete stratigraphy of Marwat-01 Well.

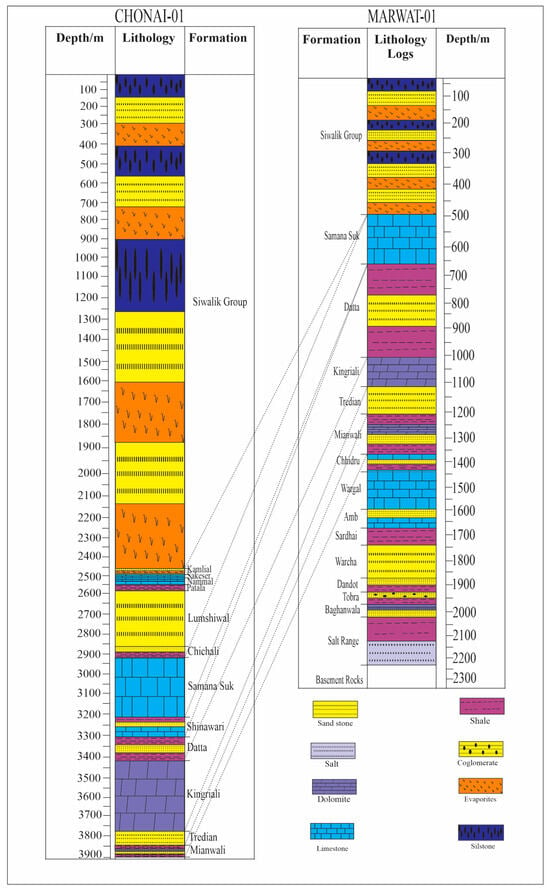

Figure 11.

Correlation between the Chonai-01 and Marwat-01 wells illustrating the lateral continuity of key stratigraphic horizons and lithological variations across the study area.

Furthermore, this provides insight into the broader tectono-stratigraphic evolution of the Himalayan foreland basin system and highlights the value of integrated geophysical and geological studies in regions affected by complex deformation histories. Overall, the findings of this work contribute to the geological and geophysical understanding of the Bannu Basin and provide a regional-scale framework relevant to future hydrocarbon exploration and resource assessment.

5. Discussion

The integrated interpretation of legacy 2D seismic profiles and well data provides new insight into the structural configuration and petroleum prospectivity of the southeastern Bannu Basin, although the analysis is necessarily constrained by the fair-to-poor quality of the seismic data and the absence of dense spatial coverage. The interpreted seismic sections indicate a structural framework dominated by fault-related folding and salt-controlled deformation, with the Precambrian Salt Range Formation acting as a regional detachment horizon that decouples basement and cover sequences. However, the seismic evidence suggests that salt-influenced deformation in the study area is generally mild to moderate, expressed mainly through gentle folding, localized faulting, and subtle reflector warping, rather than large, fully developed diapiric structures. This implies that halokinesis in the southeastern Bannu Basin is more likely incipient or subdued, in contrast to the strongly developed salt tectonics observed farther southeast within the Potwar Plateau.

The identification of both normal and reverse faults indicates a polyphase tectonic history, where earlier extensional structures were later reactivated under compressional and transpressional stress regimes associated with Himalayan orogeny. The coexistence of these structures supports a model of progressive foreland basin evolution, in which tectonic loading, flexural subsidence, and salt mobility jointly controlled sedimentation and structural development. Lateral stratigraphic variations derived from well correlation-particularly the thick accumulation of the Siwalik Group and the preservation of key reservoir units such as the Datta and Lumshiwal formations-reflect spatial differences in accommodation space and uplift along the basin margin.

When compared with the neighboring Potwar and Kohat basins, the Bannu Basin exhibits broadly similar salt-detached fold-and-thrust architecture, but with weaker structural expression and less pronounced deformation. This difference is likely related to variations in shortening magnitude, sediment loading, and mechanical stratigraphy across the Sub-Himalayan foreland system. While the Potwar Basin contains well-developed salt diapirs and large hydrocarbon accumulations, the Bannu Basin appears to be characterized by smaller fault-bounded closures and low-amplitude folds, which still represent valid exploration targets but with potentially higher structural and stratigraphic risk.

From a petroleum system perspective, the presence of proven source rocks, multiple reservoir intervals, regional shale-evaporite seals, and salt-related structural traps confirms that the essential elements for hydrocarbon accumulation are present. Migration is likely controlled by fault-related pathways and salt-induced structural highs, while trap integrity is enhanced by both shale and evaporitic sealing units. However, basin-margin uplift and possible erosion, particularly toward the Marwat Range, introduce uncertainty regarding local source rock preservation and reservoir continuity.

6. Conclusions

- This work validates that an integrated approach combining 2D seismic interpretation with well-log analysis is critical for accurately characterizing basin style, identifying structural traps, and assessing petroleum potential in the foreland basin.

- The study methodology and results offer a framework for comparable investigations in other tectonically active regions and highlight the interplay between sedimentation, tectonics, and salt-related distortion in controlling hydrocarbon systems.

- By providing detailed insights into the structural and stratigraphic evolution of the southeastern Bannu Basin, this research lays the foundation for future exploration efforts and enriches the broader understanding of foreland basin development in the Himalayan context.

- We confirm from well tops that the Siwalik group is significantly thicker (2462 m) at the plain area of the southeastern part of the Bannu Basin, while much thinner (492 m) at the Marwat range.

- There is an unconformity between the Siwalik and Samana Suk Formation and also between the Samana Suk and Datta Formation. The Datta formation is thicker at Marwat Range (339 m), while only 105 m thick further northwest in the Bannu Basin plain area.

- Subsurface stratigraphy from the well data indicates the absence of Paleocene, Eocene, and Miocene deposits in the eastern and southern regions, as confirmed by data from the Marwat-01 well.

- The strata shown on the seismic lines exhibit generally mild deformation, likely to be related to the salt movement. Additionally, the thickness variations can also be attributed to the halokinesis in the studied area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.; Methodology, A.A.; Software, A.A.; Formal analysis, Z.M.; Investigation, R.Q. and N.J.; Data curation, A.A. and Z.M.; Writing—original draft, A.A.; Writing—review and editing, A.A. and N.J.; Visualization, R.Q.; Supervision, R.Q.; Funding acquisition, R.Q. We declare that this manuscript is original, has not been previously published, and is not currently under consideration for publication elsewhere. All co-authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript, and the order of authorship has been agreed upon by all parties involved. This research was carried out as part of a Master’s thesis under the supervision of R.Q. While R.Q. served as the main academic advisor, Z.M. provided guidance during the process. N.J. played active role in reviewing and finalizing the manuscript. The core tasks of data acquisition, selection, interpretation, and analysis were conducted independently by the first author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under (Grant No.42274193). Without their generous financial support, this work would not have been possible.

Informed Consent Statement

The authors certify that any third-party content featured in this article was reproduced with the original rights holders’ consent. The figure legends and captions fully credit these sources, and the relevant author can give copies of the permission documents upon request.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Rongyi Qian for their unwavering guidance, support, and valuable feedback throughout this research. My sincere thanks also go to Zhenning Ma who assist me and OGDCL (Oil and Gas development company Limited) for providing me the relative data was invaluable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in relation to this article.

References

- Craig, J.; Hakhoo, N.; Bhat, G.M.; Hafiz, M.; Khan, M.R.; Misra, R.; Pandita, S.K.; Raina, B.K.; Thurow, J.; Thusu, B.; et al. Petroleum systems and hydrocarbon potential of the North-West Himalaya of India and Pakistan. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 187, 109–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, F.; Zhang, J.; Khanal, G.; Yang, L. The Himalayan Collisional Orogeny: A Metamorphic Perspective. Acta Geol. Sin. Eng. 2022, 96, 1842–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pêcher, A.; Seeber, L.; Guillot, S.; Jouanne, F.; Kausar, A.; Latif, M.; Majid, A.; Mahéo, G.; Mugnier, J.L.; Rolland, Y.; et al. Stress field evolution in the northwest Himalayan syntaxis, northern Pakistan. Tectonics 2008, 27, 2007TC002252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, J.-P.; Nievergelt, P.; Oberli, F.; Seward, D.; Davy, P.; Maurin, J.-C.; Diao, Z.; Meier, M. The Namche Barwa syntaxis: Evidence for exhumation related to compressional crustal folding. J. Asian Earth Sci. 1998, 16, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najman, Y.; Appel, E.; Boudagher-Fadel, M.; Bown, P.; Carter, A.; Garzanti, E.; Godin, L.; Han, J.; Liebke, U.; Oliver, G.; et al. Timing of India-Asia collision: Geological, biostratigraphic, and palaeomagnetic constraints. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, 2010JB007673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Ding, L.; Khan, M.A.; Jadoon, I.A.K.; Haneef, M.; Baral, U.; Cai, F.; Wang, H.; Yue, Y. Tectonic Implications of Detrital Zircon Ages From Lesser Himalayan Mesozoic-Cenozoic Strata, Pakistan. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2018, 19, 1636–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouilhol, P.; Jagoutz, O.; Hanchar, J.M.; Dudas, F.O. Dating the India–Eurasia collision through arc magmatic records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 366, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hinsbergen, D.J.J.; Lippert, P.C.; Dupont-Nivet, G.; McQuarrie, N.; Doubrovine, P.V.; Spakman, W.; Torsvik, T.H. Greater India Basin hypothesis and a two-stage Cenozoic collision between India and Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7659–7664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A.; Harrison, T.M. Geologic Evolution of the Himalayan-Tibetan Orogen. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2000, 28, 211–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pichon, X.; Fournier, M.; Jolivet, L. Kinematics, topography, shortening, and extrusion in the India-Eurasia collision. Tectonics 1992, 11, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.; Copley, A.; Hussain, E. Evolution and dynamics of a fold-thrust belt: The Sulaiman Range of Pakistan. Geophys. J. Int. 2015, 201, 683–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royden, L.H.; Burchfiel, B.C.; Van Der Hilst, R.D. The Geological Evolution of the Tibetan Plateau. Science 2008, 321, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, A.; Khan, M.R.; Wahid, A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Rezaee, R.; Ali, S.H.; Erdal, Y.D. Petroleum System Modeling of a Fold and Thrust Belt: A Case Study from the Bannu Basin, Pakistan. Energies 2023, 16, 4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abir, I.A.; Khan, S.D.; Aziz, G.M.; Tariq, S. Bannu Basin, fold-and-thrust belt of northern Pakistan: Subsurface imaging and its implications for hydrocarbon exploration. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 85, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, A.; Khalid, P.; Jadoon, K.Z.; Jouini, M.S. The depositional setting of the Late Quaternary sedimentary fill in southern Bannu basin, Northwest Himalayan fold and thrust belt, Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 6587–6604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordi, M. Sedimentary basin analysis of the Neo-Tethys and its hydrocarbon systems in the Southern Zagros fold-thrust belt and foreland basin. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 191, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, O.; Mazzoli, S.; Von Hagke, C.; Rosenau, M.; Fillon, C.; Granado, P. Style of deformation and tectono-sedimentary evolution of fold-and-thrust belts and foreland basins: From nature to models. Tectonophysics 2019, 767, 228163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Khan, R.; Madayipu, N.; Zhong, Y.; Khan, A. Structural and Stratigraphic Study of Hazara-Kashmir Syntaxis with the Aid of Geographic Information System and Field Data Approach. J. Geol. Soc. India 2024, 100, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ahmed, R.; Raza, H.A.; Kemal, A. Geology of Petroleum in Kohat-Potwar Depression, Pakistan. AAPG Bull. 1986, 70, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, S.F.; Zafar, M.; Jehandad, S.; Khan, T.; Siyar, S.M.; Qadir, A. Integrated geochemical study of Chichali Formation from Kohat sub-basin, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2020, 10, 2737–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, K.; Wahid, S.; Yaseen, M.; Hanif, M.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, J.; Mehmood, M. Analysis of subsurface structural trend and stratigraphic architecture using 2D seismic data: A case study from Bannu Basin, Pakistan. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2021, 11, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, P.P.G. Seismic Exploration Methods for Structural Studies and for Active Fault Characterization: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caineng, Z.; Guangya, Z.; Shizhen, T.; Suyun, H.; Xiaodi, L.; Jianzhong, L.; Dazhong, D.; Rukai, Z.; Xuanjun, Y.; Lianhua, H.; et al. Geological features, major discoveries and unconventional petroleum geology in the global petroleum exploration. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2010, 37, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, N.C. Seismic Stratigraphy and Seismo-Tectonics in Petroleum Exploration. In Seismic Data Interpretation and Evaluation for Hydrocarbon Exploration and Production; Advances in Oil and Gas Exploration & Production; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 101–115. ISBN 978-3-030-75300-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, T.; Taral, S.; More, S.; Bera, S. Cenozoic Himalayan Foreland Basin: An Overview and Regional Perspective of the Evolving Sedimentary Succession. In Geodynamics of the Indian Plate; Gupta, N., Tandon, S.K., Eds.; Springer Geology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 395–437. ISBN 978-3-030-15988-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, A.; Roohi, R.; Naz, R.; Mustafa, N. Monitoring cryosphere and associated flood hazards in high mountain ranges of Pakistan using remote sensing technique. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 933–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Salim, A.M.A.; Gaafar, G.R.; Yusoff, A.W.I.W. Tectonic development of the Northwest Bonaparte Basin, Australia by using Digital Elevation Model (DEM). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 30, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miall, A.D.; Catuneanu, O.; Eriksson, P.G.; Mazumder, R. Chapter 23 A brief synthesis of Indian Precambrian basins: Classification and genesis of basin-fills. Memoirs 2015, 43, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.M.; Craig, J.; Hafiz, M.; Hakhoo, N.; Thurow, J.W.; Thusu, B.; Cozzi, A. Geology and hydrocarbon potential of Neoproterozoic–Cambrian Basins in Asia: An introduction. SP 2012, 366, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloetingh, S.; Burov, E. Lithospheric folding and sedimentary basin evolution: A review and analysis of formation mechanisms: Lithospheric folding and sedimentary basin evolution. Basin Res. 2011, 23, 257–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, M.G. Passive-margin salt basins: Hyperextension, evaporite deposition, and salt tectonics. Basin Res. 2014, 26, 154–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D. Latest developments in seismic texture analysis for subsurface structure, facies, and reservoir characterization: A review. Geophysics 2011, 76, W1–W13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.