Abstract

Rain-on-snow (ROS) events significantly impact hydrological processes in snowy regions, yet their seasonal drivers remain poorly understood, particularly in low-elevation and low-gradient catchments. This study uses an XGBoost-SHAP explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) model to analyze meteorological and watershed controls on ROS runoff in the Laurentian Great Lakes region. We used daily discharge, precipitation, temperature, and snow depth data from 2000 to 2023, available from HYSETS, to identify ROS runoff. The XGBoost model’s performance for predicting ROS runoff was higher in winter (R2 = 0.65, Nash–Sutcliffe = 0.59) than in spring (R2 = 0.56, Nash–Sutcliffe = 0.49), indicating greater predictability in colder months. The results reveal that rainfall and temperature dominated ROS runoff generation, jointly explaining more than 60% of total model importance, while snow depth accounted for 8–12% depending on season. Winter runoff is predominantly governed by climatic factors—rainfall, air temperature, and their interactions—with soil permeability and slope orientation playing secondary roles. In contrast, spring runoff shows increased sensitivity to land cover characteristics, particularly agricultural and shrub cover, as vegetation-driven processes become more influential. Snow depth effects shift from predominantly negative in winter, where snow acts as storage, to positive contributions in spring at shallow to moderate depths. ROS runoff responded positively to air temperatures exceeding approximately 2.5 °C in both winter and spring. Land cover influences on ROS runoff differ by vegetation type and season. Agricultural areas consistently increase runoff in both seasons, likely due to limited infiltration, whereas shrub-dominated regions exhibit stronger runoff enhancement in spring. The seasonal shift in dominant controls underscores the importance of accounting for land–climate interactions in predicting ROS runoff under future climate scenarios. These insights are essential for improving flood forecasting, managing water resources, and developing adaptive strategies.

1. Introduction

Rain-on-snow (ROS) events, where rain falls on existing snowpack, are a critical hydrological phenomenon. ROS events are increasingly recognized as significant factors influencing water resources. These events can lead to rapid snowmelt, increased runoff, and subsequent changes in water quality. ROS events can have both positive and negative impacts on groundwater recharge. On one hand, ROS events can enhance groundwater recharge by increasing the amount of water available for infiltration, particularly in regions where the snowpack acts as a natural reservoir [1,2,3]. On the other hand, midwinter melt events followed by freezeback can reduce groundwater recharge by increasing soil water content and leaving the ground exposed to subsequent cold periods, which can lead to frozen ground and reduced infiltration [2]. ROS events are critical for understanding freshwater ecosystems, particularly in forested and agricultural regions. These events can lead to rapid snowmelt combined with rainfall leading to high runoff, which in turn affects water quality by mobilizing nutrients, sediments, and organic matter into surface waters [4,5,6]. These events can lead to the mobilization of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), which are essential nutrients but can cause eutrophication when present in excess. Studies have shown that ROS events contribute a substantial proportion of annual and seasonal nutrient export, particularly in forested catchments [7,8].

In the Great Lakes region and the eastern U.S., where ROS frequently contributes to rapid snowmelt, high runoff, and flooding [9,10], ROS events are particularly common in late winter and early spring when warm, moist air masses from the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean interact with persistent snowpack [11,12]. Studies indicate that ROS events in this region vary in frequency and intensity due to factors such as elevation, proximity to the Great Lakes (which enhance lake-effect snowfall), and synoptic-scale atmospheric patterns [10,13]. For instance, the Appalachian regions of Pennsylvania and New York experience more frequent ROS-induced flooding due to orographic precipitation and deep snowpack [10], while the Midwest sees variability linked to fluctuating winter temperatures and snow cover duration [11]. The frequency and intensity of ROS events are influenced by climate change, with warmer winters and altered precipitation patterns exacerbating their occurrence [14,15]. Climate projections indicate that ROS events may become more frequent, driven by increased rainfall occurrence but reduced intensity due to declining snowpack and diminished melt contributions [9,12,16,17]. In the Great Lakes Basin, ROS snowmelt in warmer, southern subbasins is projected to decrease by approximately 30% by the mid-21st century, while colder, northern subbasins will experience less than a 5% reduction [15].

ROS events often result in rapid increases in river discharge due to the combined effects of rainfall and snowmelt. The magnitude of ROS runoff depends on the meteorological variables such as the intensity and duration of rainfall, air temperature and condition of the snowpack [18,19,20]. For instance, in mountainous regions like the Sierra Nevada, the cold content of the existing snowpack influences how watersheds respond hydrologically to extreme ROS events [21]. Similarly, in coastal mountain regions, high-elevation rainfall during ROS events can lead to enhanced runoff due to the contribution of snowmelt [22].

In addition, the magnitude of ROS runoff is also influenced by watershed characteristics, including slope, forest cover, soil permeability, and aspect. Steeper slopes accelerate runoff by reducing infiltration time, leading to faster peak discharges [23]. Forest cover modulates snowmelt rates by intercepting rainfall and reducing wind-driven snow redistribution, while also influencing energy fluxes through canopy shading, longwave radiation, and reduced turbulence [24,25]. Similarly, agricultural catchments with impermeable soils and reduced infiltration capacity may experience higher runoff responses during ROS events [26]. Catchment size and drainage network characteristics also influence ROS runoff generation. Smaller catchments tend to respond more rapidly to ROS events, with shorter lag times between rainfall and runoff. For example, in the Sierra Nevada, small headwater catchments exhibited rapid runoff responses during ROS events due to their steep terrain and well-developed drainage networks [27]. In contrast, larger catchments may exhibit more attenuated runoff responses due to the greater opportunity for water to infiltrate or be stored in the landscape [28].

Most existing studies on snowmelt and runoff have focused on mountainous regions, where elevation and terrain dominate hydrologic responses [23,29]. Here, we examine how climate variables (rainfall, temperature, and snow depth) and watershed properties influence rain-on-snow runoff in low-elevation, low-gradient catchments across the Laurentian Great Lakes regions, where ROS events are frequent but the drivers of the ROS runoff remain understudied [9,12]. We examine how land cover modifies the effects of precipitation and temperature on ROS runoff variability. We also assess how this modulation changes from winter to spring, as shifts in snowpack and canopy conditions may alter the relative importance of land cover versus climate controls [30,31].

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area

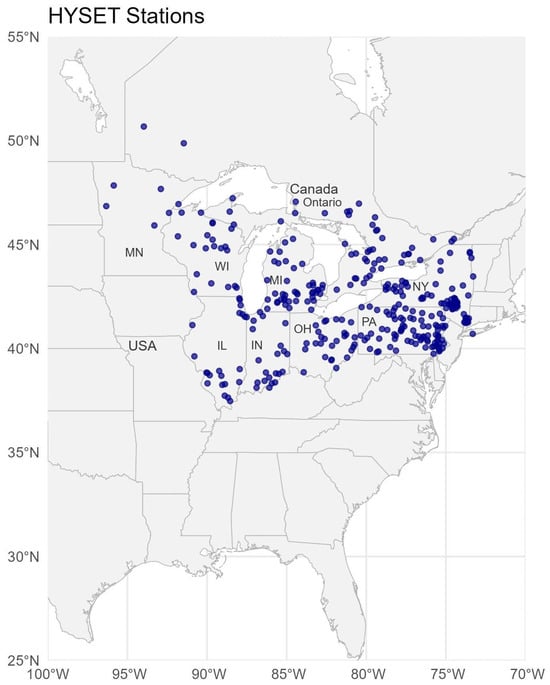

The study focuses on the US Midwest region, encompassing eight U.S. states: Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York, and the Canadian province of Ontario (Figure 1). This region is characterized by its proximity to the Great Lakes, which significantly influence local climate patterns, including snowfall and temperature regimes [10]. The area experiences frequent rain-on-snow (ROS) events, particularly during late winter and early spring, when warm, moist air masses from the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean interact with existing snowpack [10,11,32]. The terrain varies from flat plains in the Midwest to more rugged topography in the Appalachian regions of Pennsylvania and New York, which can exacerbate runoff and flooding during ROS events [10]. The Great Lakes also contribute to lake-effect snow, further complicating snowpack dynamics and runoff processes [9]. This region’s hydrology is critical for water resource management, flood forecasting, and understanding climate change impacts on winter precipitation and snowmelt patterns [12,15].

Figure 1.

Distribution of HYSET catchments used in this study. Blue dots represent the streamflow gauge of the study catchments (330 total) in the Laurentian Great Lakes region spanning the eight U.S. states—Minnesota (MN), Wisconsin (WI), Illinois (IL), Indiana (IN), Michigan (MI), Ohio (OH), Pennsylvania (PA), and New York (NY)—and Ontario, Canada.

2.2. Data

We defined rain-on-snow (ROS) events as days meeting two concurrent conditions: (1) liquid precipitation (rainfall) ≥ 1 mm, and (2) snow water equivalent (SWE) ≥ 1 mm on the ground [15,33]. Rainfall was partitioned from total precipitation when daily average air temperature exceeded 0 °C, following standard hydrometeorological practice [34]. ROS-induced runoff (Qr_ros) was quantified as the difference between discharge on the ROS-day and baseline discharge (taken as the discharge one day prior to the ROS event onset), isolating the ROS contribution to streamflow [35]. Only ROS events that generated measurable runoff increases (Qr_ros > 0) were retained for analysis, ensuring focus on hydrologically significant events [29].

Daily discharge data were obtained from the HYSETS database [36], which compiles quality-controlled streamflow records from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) National Water Information System (NWIS) [37] and the Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) Water Survey Canada (WSC) National Water Data Archive (HYDAT) [38]. Precipitation (mm/day) and maximum/minimum air temperature (°C) were also sourced from HYSETS, which integrates multiple data products including station observations, gridded datasets, and reanalysis data (e.g., ERA5-Land). Snow water equivalent (SWE; mm) was derived from the ERA5-Land reanalysis [39], a high-resolution (9 km) global dataset for snowpack dynamics. Watershed properties (e.g., elevation, slope, land cover) were extracted from HYSETS, which incorporates physiographic data from the North American Land Change Monitoring System (NALCMS, 2010) [40] and digital elevation models. To ensure data quality and representativeness, we selected watersheds with (1) ≥2 years of complete daily records (2000–2023) without missing values, (2) ≥10% forest cover, and (3) drainage areas between 10 and 1000 km2. All variables were spatially averaged at the watershed scale.

2.3. Meteorological and Watershed Controls on Rain-on-Snow (ROS) Runoff

To understand which factors control rain-on-snow runoff—and how they interact—I used Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), specifically combining Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) with Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP). This framework enables us to quantify the relative influence of climatic variables (rainfall, temperature, snow depth) and watershed properties (land cover, topography, soils) on ROS runoff generation. This approach aligns with recent ecological studies leveraging SHAP to disentangle driver interactions [41,42]. All analyses were conducted in R (R 4.5.2) using the XGBoost [43] and SHAPforxgboost [44] R packages.

XGBoost is a machine learning algorithm that builds an ensemble of decision trees to make predictions. The XGBoost learns patterns directly from data by sequentially building trees. Each tree splits the data based on predictor values, and the final prediction combines contributions from all trees. This allows the model to capture complex, nonlinear relationships and interactions between variables without requiring to pre-specify them and is widely used in ecological and hydrological studies [45,46]. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is a framework that explains individual predictions by quantifying each feature’s contribution. For any given prediction, SHAP values decompose the model output into additive effects (e.g., Prediction = baseline + SHAP (rainfall) + SHAP (temperature) + …). Positive SHAP values indicate that a feature increases the predicted runoff for that observation, while negative values indicate suppression [47]. The SHAP approach, borrowed from cooperative game theory (where it is used to fairly divide rewards among team members), ensures that each feature receives appropriate credit for its role in the prediction, whether it acts alone or in combination with other features. The key advantages of this approach for hydrological research are (1) Feature importance: By averaging absolute SHAP values across all predictions, we identify which variables most strongly influence ROS runoff across all catchments and events. (2) Relationship direction and nonlinearity: SHAP summary plots reveal not just importance, but how features affect runoff—whether effects are positive or negative, linear or nonlinear, and whether they vary with feature magnitude. (3) Marginal effects: Partial dependence plots show the isolated effect of a single feature (e.g., temperature) on runoff predictions while averaging out the influence of all other features, allowing us to identify thresholds and optimal ranges.

We trained separate XGBoost models for winter and spring seasons, to predict ROS runoff using predictors including rainfall, temperature, forest cover, and watershed properties (e.g., slope, forest cover, soil permeability, soil porosity, and aspect). All predictor variables used in the XGBoost–SHAP model are defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of predictor variables used in XGBoost-SHAP models for rain-on-snow (ROS) runoff prediction.

The model hyperparameters were optimized using Bayesian optimization with k-fold cross-validation. Physical relationships between predictors and hydrological response were preserved by incorporating monotonicity constraints during the optimization process. The model enforced positive monotonic constraints on features where higher values are physically expected to increase runoff: slope (steeper terrain enhances flow), urban (impervious surfaces reduce infiltration), rainfall (greater precipitation amplifies runoff), and temperature (warmer conditions accelerate snowmelt). Conversely, negative constraints were applied where higher values suppress runoff: north_aspect (reduced solar exposure suppresses melt), soil_perm (higher permeability promotes infiltration), and soil_porosity (greater pore space increases water retention). These constraints ensured the model’s behavior aligned with hydrological principles. The model incorporated several key feature interactions to capture nonlinear hydrological processes: rain_temp (rainfall × temperature) to account for rain-on-snow events, forest_temp (forest cover × temperature) and forest_wind (forest cover × wind speed) to modulate melt dynamics under canopy effects, aspect_temp (north/east aspect × temperature) to represent slope-dependent solar radiation impacts, and temp_snow (temperature × snow depth) to capture melt-rate sensitivity to snowpack conditions. These interactions were included alongside base features to better represent complex watershed responses.

To evaluate the performance of the XGBoost models in predicting rain-on-snow (ROS) runoff, we used several widely accepted statistical metrics: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), coefficient of determination (R2), Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), and Spearman rank correlation. These metrics were computed for both training and testing datasets to assess model accuracy, robustness, and potential overfitting. RMSE quantifies the average magnitude of prediction errors in the original units (mm/day), with lower values indicating better model accuracy [48]. R2 measures the proportion of variance in observed runoff explained by the model, ranging from 0 (no predictive power) to 1 (perfect fit) [49]. The NSE evaluates hydrological model performance by normalizing prediction errors against the variance of observed data, where values >0 indicate model skill exceeding the mean benchmark [50]. These metrics were calculated for both training and validation datasets to assess potential overfitting, following best practices in hydrological machine learning [2,51].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance of the XGBoost Model in Predicting Rain-on-Snow Runoff

The performance of the XGBoost model in predicting rain-on-snow (ROS) runoff for winter and spring seasons is summarized in Table 2. The XGBoost model exhibits distinct seasonal performance in predicting runoff from rain-on-snow events across the US Great Lakes region. For winter, the model achieves moderate predictive accuracy with a test R2 of 0.65, RMSE of 4.21, and Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency of 0.59, supported by a strong Spearman correlation (0.74). In spring, the model shows slightly lower explanatory power (test R2 = 0.56, Nash–Sutcliffe = 0.49) but demonstrates improved generalization, as evidenced by a test RMSE (3.61) only marginally higher than training RMSE (3.44). The winter model’s higher R2 and Nash–Sutcliffe values suggest that runoff processes during colder months may be more predictable, possibly due to more stable snowpack dynamics. In contrast, spring runoff, influenced by rapid snowmelt and variable land–surface interactions, presents greater complexity, leading to reduced predictive performance. Consistent Spearman correlations (winter: 0.74; spring: 0.67) indicate that the model reliably ranks ROS events within both seasons. These differences highlight the importance of accounting for seasonal variability in hydrological modeling.

Table 2.

Performance metrics of the XGBoost model for predicting rain-on-snow (ROS) runoff in the US Great Lakes region (2000–2023), comparing winter and spring seasons for both training and testing datasets.

The model demonstrated acceptable predictive accuracy for both seasons, with winter (test R2 = 0.65, Nash–Sutcliffe = 0.59) outperforming spring (test R2 = 0.56, Nash–Sutcliffe = 0.49), suggesting greater predictability of ROS runoff processes during colder months. This aligns with findings from similar hydrological studies in snow-dominated regions, where winter ROS runoff is often more stable due to consistent snowpack dynamics, while spring runoff exhibits higher variability from rapid melt and heterogeneous land interactions [29,52]. However, temperature-driven snowmelt studies suggest spring snowmelt becomes more predictable as temperatures consistently exceed freezing, leading to uniform melt rates and higher model accuracy in spring compared to that in winter months [53,54].

Both winter and spring XGBoost models in this study struggled with very low runoff values, as evidenced by extremely high MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error) values (300–400%), highlighting the challenges of modeling near zero-inflated hydrological data even with transformation techniques [55,56]. Machine learning models, despite their flexibility, often fail to capture the physical constraints governing minimal runoff generation (e.g., infiltration capacity, residual storage), a weakness also observed in process-based models [57]. Recent work suggests that hybrid approaches or censored regression techniques may improve low-flow predictions [58].

3.2. Meteorological and Watershed Controls on Rain-on-Snow Runoff

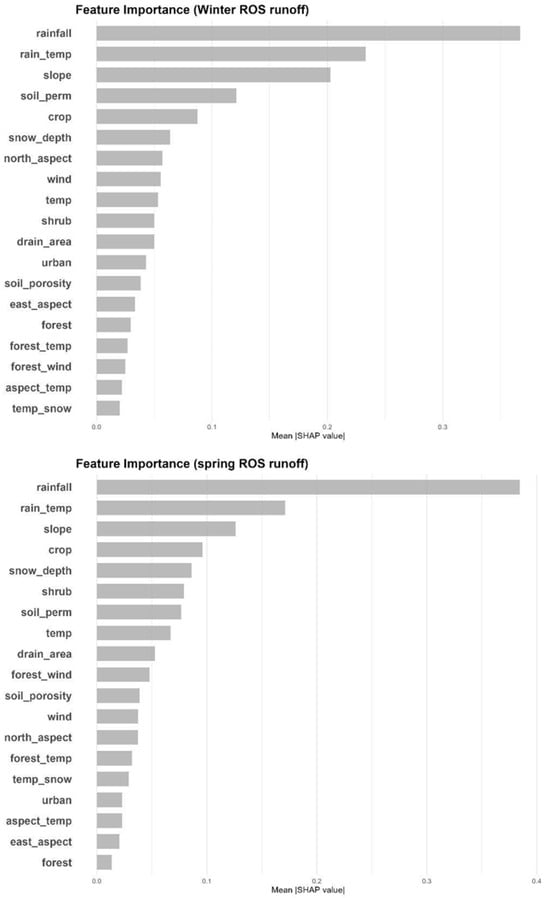

The feature importance plots reveal both consistent and seasonally distinct drivers of Rain-on-Snow (ROS) runoff in the US Great Lakes Basin, with rainfall and its interaction with temperature (rain_temp) emerging as the dominant predictors across both winter and spring, underscoring the fundamental role of precipitation intensity and thermal conditions in melt dynamics (Figure 2). Slope ranks highly in both seasons, reflecting the universal importance of terrain steepness in runoff generation, while snow_depth maintains moderate influence, though its relative significance diminishes slightly in spring as snowpack depletes. However, key seasonal differences emerge in secondary drivers: winter runoff is strongly shaped by soil permeability (soil_perm) and north_aspect, highlighting the importance of subsurface drainage and solar exposure during colder months when frozen or saturated soils dominate hydrologic response. In contrast, spring runoff shows increased sensitivity to land cover, with crop and shrub gaining prominence, suggesting that surface characteristics and vegetation-driven processes (e.g., albedo, interception) become more influential as temperatures rise. The temperature-linked interactions (forest_temp, temp_snow) and static features like urban or east_aspect remain consistently low in importance across seasons, indicating their secondary role compared to climatic and broader landscape controls. Together, these patterns illustrate a winter system governed by rain–snow transitions and infiltration capacity, while spring behavior shifts toward land-cover-mediated surface flow, with both seasons sharing a foundational dependence on precipitation and temperature synergies.

Figure 2.

Relative importance of predictor variables in XGBoost models for rain-on-snow (ROS) runoff prediction during winter (top) and spring (bottom) seasons. Bars represent mean SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values indicating the average contribution of each feature to model predictions. All predictor variables are defined in Table 1.

During winter, ROS events are predominantly governed by climatic factors such as rainfall intensity, air temperature, and the thermal state of the snowpack, which collectively determine the extent of rainwater infiltration and subsequent runoff generation [31,59]. The high cold content of the snowpack and potential presence of frozen soils during this period limit infiltration, enhancing surface runoff. In contrast, spring ROS events occur when the snowpack is typically warmer and more isothermal, allowing for greater percolation of rainwater, while progressing soil thaw increases subsurface water transmission capacity. Consequently, both climatic drivers and land surface characteristics, such as vegetation cover become more influential in modulating ROS runoff [60,61]. In addition, during winter, when vegetation is largely dormant, its role in ROS processes is minimal [62]. However, with the onset of spring, increased vegetation activity begins to significantly influence ROS runoff through multiple mechanisms. Emerging foliage intercepts rainfall, reducing direct snowpack saturation and altering melt dynamics [63].

Additionally, active root water uptake through transpiration enhances soil storage capacity during spring, which modulates surface runoff generation [25]. These insights are crucial for refining models and developing targeted management strategies to address ROS runoff under changing climate scenarios.

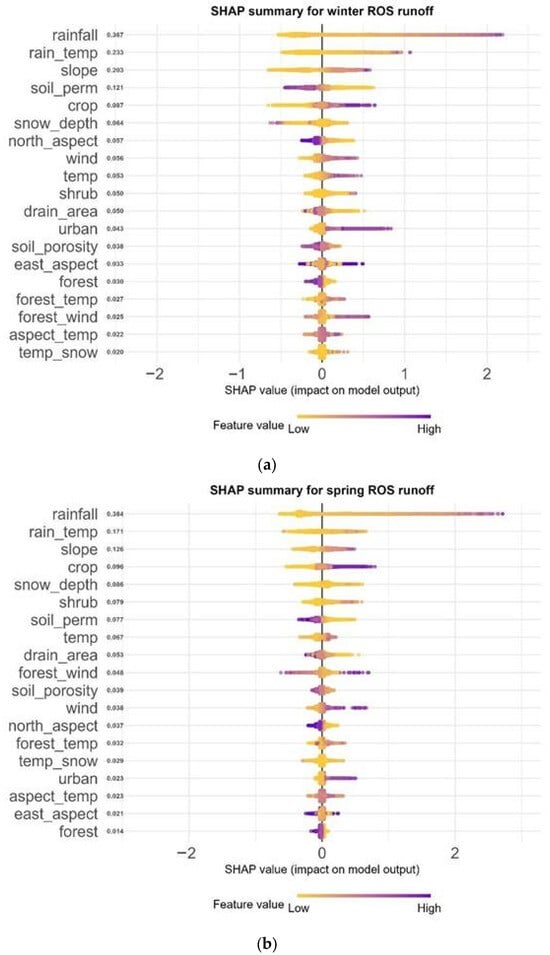

Figure 3 shows how meteorological, topographic, and land cover factors differentially influence ROS runoff across seasons. The SHAP summary plots provide insights into the nature of the impact of each feature on ROS runoff during winter and spring seasons. SHAP values represent the marginal contribution of each predictor to the model’s output, expressed in the same units as the predicted variable but standardized for comparison across features. In both seasons, rainfall consistently exhibits a strong positive impact on ROS runoff, with higher rainfall values leading to increased runoff. The interaction term rain_temp also shows a predominantly positive influence, indicating that warmer temperatures during rainfall events enhance ROS runoff by promoting snowmelt and surface water generation.

Figure 3.

SHAP summary plots illustrating the relative influence of predictor variables on rain-on-snow (ROS) runoff for (a) winter and (b) spring seasons. Each point represents a single catchment-event combination, where color indicates the magnitude of the predictor variable (yellow = low, purple = high). SHAP values are dimensionless and denote both the magnitude and direction of each variable’s contribution to predicted runoff. Higher positive SHAP values indicate features that enhance runoff, whereas negative values indicate features that suppress it.

The SHAP summary plots reveal distinct seasonal patterns in how crop, shrub, snow depth, and drainage area influence ROS runoff. In winter, higher snow depth generally has a negative effect on runoff, indicating that deeper snowpack initially absorbs or delays the release of meltwater, reducing immediate runoff generation. However, in spring, this relationship shifts, with moderate snow depths contributing positively to runoff.

Crop cover shows a consistently positive influence across both seasons, suggesting that agricultural land tends to enhance runoff potential, possibly due to reduced infiltration capacity and faster overland flow compared to natural vegetation. Shrub exhibits a stronger positive impact in spring, implying that shrub-dominated landscapes may promote runoff through mechanisms likely due to altered snow accumulation patterns [64]. ROS runoff increases with increase in crop (agricultural) land fraction due to soil compaction and reduced infiltration capacity caused by agricultural practices. Compacted soils, particularly those with plow pans, have significantly lower porosity and hydraulic conductivity, leading to increased surface runoff [65].

The forest_wind interaction, which serves as a proxy for turbulence energy within forested areas, shows a positive contribution to ROS runoff, particularly during spring. This suggests that in the presence of forest cover, stronger winds enhance runoff generation, possibly by accelerating melt through microclimatic effects [66]. Soil frost in the forested catchments may alter the infiltration and flow of meltwater, enhancing the magnitude of runoff [67,68]. The forest_temp interaction, representing the influence of longwave radiation within forested canopies, exhibits a more nuanced pattern. During winter, this term tends to reduce ROS runoff, likely due to the insulating effect of dense canopy cover that limits snowmelt despite higher temperatures. However, in spring, the same interaction shifts toward a positive contribution, indicating that forest-modulated warming may enhance snowmelt and runoff. The forest canopy in snowy regions enhances longwave radiation transmission to the snowpack while reducing shortwave radiation due to shading [69].

3.3. Impact of Air Temperature and Snow Depth on Rain-on-Snow Runoff Generation

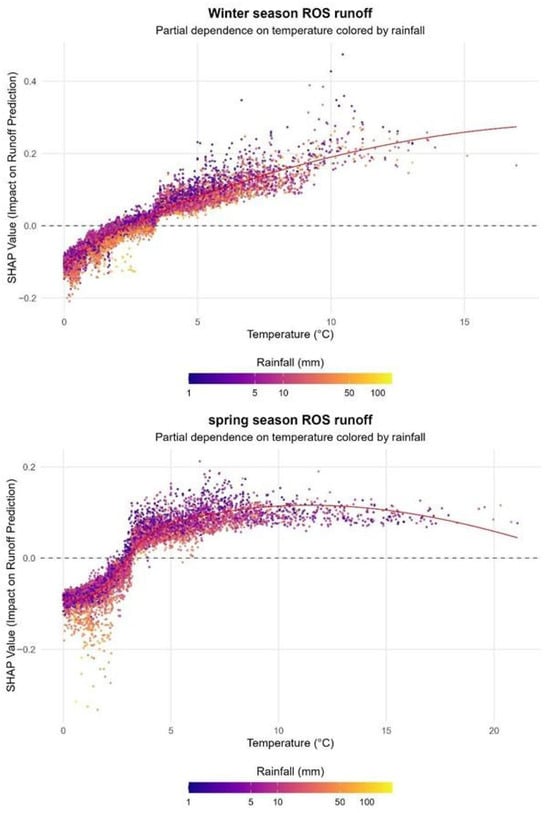

3.3.1. Air Temperature

The partial dependence plots (Figure 4) for ROS runoff in the winter and spring seasons illustrate the relationship between air temperature and its impact on runoff prediction, while also considering snow depth as a contributing factor. In the winter season plot, there is a clear positive trend in SHAP values (impact on runoff prediction) as air temperature increases from 0 to approximately 10 °C. However, at air temperatures below approximately 2.5 °C (on the x-axis), the SHAP values are negative. This observation indicates that very low temperatures suppress runoff generation because they prevent significant melting of the snowpack. In these cold conditions, even areas with deep snow (represented by darker colors in the color gradient) do not experience substantial runoff, as the snow remains frozen and does not contribute to liquid water flow. The negative SHAP values reflect the inhibitory effect of these low temperatures on runoff, emphasizing that such conditions reduce the likelihood or amount of runoff compared to higher temperatures. In spring, beyond approximately 5 °C, SHAP values plateau and then decline, suggesting that higher temperatures may reduce runoff as snowpack becomes depleted or melting accelerates, promoting infiltration or evapotranspiration rather than surface runoff. However, at air temperatures below approximately 2.5 °C, SHAP values are still negative, indicating that runoff is suppressed due to the lack of snowmelt. The transition to positive SHAP values occurs at around 2.5 °C in both spring and winter, reflecting the threshold temperature at which melting begins to occur and runoff generation becomes more likely.

Figure 4.

Partial dependence plots showing the relationship between temperature and rain-on-snow (ROS) runoff impact during winter and spring seasons. Points represent individual catchment-event combinations colored by rainfall amount (mm), with purple indicating low rainfall and yellow indicating high rainfall. The smooth curves (red lines) show the fitted relationships from generalized additive models.

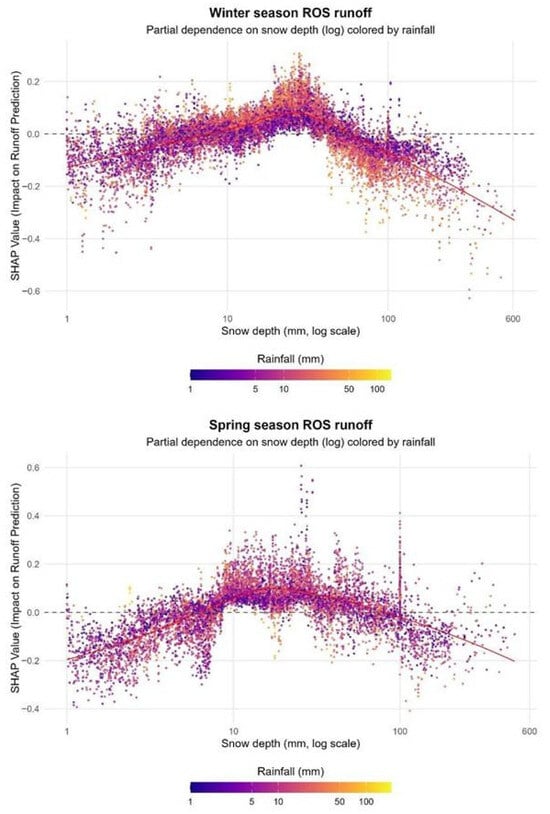

3.3.2. Snow Depth (SWE)

The partial dependence plots for ROS runoff in the winter and spring seasons are shown in Figure 5. The x-axis represents snow depth (in millimeters, plotted on a log scale), while the y-axis shows the SHAP value, which quantifies the marginal effect of snow depth on the predicted runoff. In the winter season plot, SHAP values (impact on runoff prediction) are predominantly negative across most snow depth ranges. This indicates that, during winter, snow accumulation generally suppresses ROS runoff rather than enhancing it. At low snow depths (below approximately 10 mm), SHAP values remain negative, suggesting that shallow snowpacks do not contribute significantly to runoff. As snow depth increases from 5 mm to around 50–60 mm, SHAP values become slightly positive, implying that moderate snow depths have a positive effect on runoff generation. Beyond this range, SHAP values continue to decline, indicating that very deep snowpacks further suppress runoff. The color gradient representing total ROS rainfall shows that larger rain (darker colors) tends to mitigate the negative impact of snow depth on runoff, but at higher snowpack the overall trend remains negative. This suggests that during winter, snow acts more as a storage medium rather than a direct source of runoff due to the cold conditions inhibiting melting.

Figure 5.

Partial dependence plots showing the relationship between snow depth and rain-on-snow (ROS) runoff impact during winter and spring seasons. Points represent individual catchment-event combinations colored by rainfall amount (mm), with purple indicating low rainfall and yellow indicating high rainfall. The smooth curves (red lines) show the fitted relationships from generalized additive models. Snow depth is displayed on a log scale (x-axis), while the y-axis shows the standardized impact on ROS runoff prediction.

The spring season plot reveals a distinct pattern compared to winter. In spring, SHAP values become positive at relatively low snow depths, specifically, below approximately 5 mm, whereas in winter, SHAP values do not turn positive until snow depths reach around 10 mm. This suggests that even shallow snowpacks in spring can contribute positively to runoff prediction, likely due to the presence of warmer temperatures and increased melt potential. Additionally, the spring plot shows a more pronounced peak in SHAP values between 20 and 30 mm of snow depth, indicating that this range has the strongest positive influence on runoff generation. This enhanced response may be attributed to optimal conditions for snowmelt and rain infiltration, highlighting the seasonal differences in how snow depth influences ROS runoff processes. Beyond this point, SHAP values decline again as in winter, showing diminishing returns or suppression of runoff with very deep snowpacks. The color gradient for air temperature indicates that larger rainfall conditions (darker colors) play a less pronounced role in enhancing runoff compared to winter, reflecting the transition toward more dynamic melt processes typical of spring. The plots highlight the nuanced interaction between snow depth and runoff prediction, while snow depth generally suppresses runoff in winter due to cold conditions, it begins to play a more positive role in spring as temperatures rise.

4. Summary

This study investigated how climate variables (rainfall, temperature, snow depth) and watershed properties influence rain-on-snow runoff variability in the U.S. Great Lakes Basin, examining how land cover modifies the effects of precipitation and temperature on ROS runoff and how these relationships change seasonally from winter to spring. We employed an explainable machine learning approach using Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) combined with Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) to predict and interpret ROS runoff patterns across watersheds in eight U.S. States (Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York) and Ontario, Canada, using daily data from 2000 to 2023. The data were sourced from the HYSETS database and ERA5-Land reanalysis.

- The XGBoost models demonstrated acceptable predictive accuracy with notable seasonal differences. The winter model achieved higher predictive performance (R2 = 0.65, Nash–Sutcliffe = 0.59) compared to spring (R2 = 0.56, Nash–Sutcliffe = 0.49), indicating greater predictability of ROS runoff processes during colder months when snowpack dynamics are more stable. Both models struggled with very low runoff values, highlighting the inherent challenges in modeling near-zero hydrological data even with advanced machine learning techniques.

- During winter, runoff is predominantly governed by climatic factors including rainfall intensity, air temperature, and their interactions, with soil permeability and north-facing slopes playing important secondary roles. In contrast, spring ROS events show increased sensitivity to land cover characteristics, particularly crop and shrub cover, as vegetation-driven processes become more influential with rising temperatures.

- Snow depth and temperature effects vary markedly between seasons. Snow depth effects shift from predominantly negative in winter, where snow acts as a storage medium, to positive contributions in spring at shallow to moderate depths as melting potential increases. Air temperature below approximately 2.5 °C tends to suppress ROS runoff in both winter and spring seasons.

- Land cover effects on ROS runoff vary by vegetation type and season. Agricultural areas consistently enhance runoff across both seasons due to reduced infiltration capacity, while shrub-dominated landscapes show stronger positive effects in spring, likely through altered snow distribution patterns.

Future research could apply complementary machine learning frameworks (e.g., Random Forests or physics-informed hybrid models) to test the generalizability of ROS runoff drivers identified here and validate whether the dominant controls on ROS runoff remain consistent across different modeling approaches. Incorporating process-based snowmelt models within hybrid frameworks could improve predictions by explicitly representing energy balance dynamics and cold content evolution, which are critical during the transition from winter to spring. Additionally, extending this analysis to include projected climate scenarios would help quantify how shifts in temperature and precipitation patterns may alter the relative importance of climatic versus landscape controls on ROS runoff under future warming. Investigating sub-daily temporal resolution data could also reveal finer-scale processes, such as diurnal melt–freeze cycles and rainfall intensity effects, which are not captured in daily aggregated data. Finally, applying this framework to other snow-dominated regions with different climatic and physiographic characteristics would test the transferability of our findings and help identify region-specific versus universal controls on ROS runoff generation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used in this study are publicly available from open-access databases. The R code and AI model are available on HydroShare: https://www.hydroshare.org/resource/37df609c57564cb9a48406f1d315d286/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Barnhart, T.B.; Molotch, N.P.; Livneh, B.; Harpold, A.A.; Knowles, J.F.; Schneider, D. Snowmelt rate dictates streamflow. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 8006–8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman-Rabeler, K.A.; Loheide, S.P. Drivers of variation in winter and spring groundwater recharge: Impacts of midwinter melt events and subsequent freezeback. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 59, e2022WR032733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubilowicz, J.W.; Moore, R.D. Quantifying the role of the snowpack in generating water available for run-off during rain-on-snow events from snow pillow records. Hydrol. Process. 2017, 31, 4136–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, R.T.; Singley, J.G.; Gooseff, M.N. Pulses within pulses: Concentration-discharge relationships across temporal scales in a snowmelt-dominated Rocky Mountain catchment. Hydrol. Process. 2022, 36, e14700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimers, M.C.; Buttle, J.M.; Watmough, S.A. The contribution of rain-on-snow events to annual NO3- N export from a forested catchment in south-central Ontario, Canada. Appl. Geochem. 2007, 22, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, N.J.; Eimers, M.C.; Buttle, J.M. The contribution of rain-on-snow events to nitrate export in the forested landscape of south-central Ontario, Canada. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, J.; Eimers, M.C.; Casson, N.J.; Burns, D.A.; Campbell, J.; Likens, G.E.; Mitchell, M.J.; Nelson, S.J.; Shanley, J.B.; Watmough, S.A.; et al. Regional meteorological drivers and long term trends of winter-spring nitrate dynamics across watersheds in northeastern North America. Biogeochemistry 2016, 130, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, N.J.; Eimers, M.C.; Watmough, S.A. Sources of nitrate export during rain-on-snow events at forested catchments. Biogeochemistry 2014, 120, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surfleet, C.G.; Tullos, D. Variability in effect of climate change on rain-on-snow peak flow events in a temperate climate. J. Hydrol. 2013, 479, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, T. A synoptic climatology of rain-on-snow flooding in the Mid-Atlantic region using NCEP/NCAR Re-Analysis. Phys. Geogr. 2020, 42, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Ye, H.; Jones, J. Trends and variability in rain-on-snow events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 7115–7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.I.; Sushama, L. Rain-on-snow events over North America based on two Canadian regional climate models. Clim. Dyn. 2018, 50, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachowicz, L.J.; Mote, T.L.; Henderson, G.R. A rain-on-snow climatology and temporal analysis for the eastern United States. Phys. Geogr. 2019, 41, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seybold, E.C.; Dwivedi, R.S.; Musselman, K.N.; Kincaid, D.W.; Schroth, A.W.; Classen, A.T.; Perdrial, J.; Adair, E.C. Winter runoff events pose an unquantified continental-scale risk of high wintertime nutrient export. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.T.; Ficklin, D.L.; Robeson, S.M. Hydrologic implications of projected changes in rain-on- snow melt for Great Lakes Basin watersheds. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 1755–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, Y.; Ficklin, D.L.; Myers, D.T. Projected changes in rain-on-snow events and their impacts on summer low streamflow in the Great lakes basin. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 193, 106612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, Y.; Ficklin, D.L.; Myers, D.T.; Qi, J.; Knouft, J.H.; Murchie, K.J.; Day, S. Climate-Driven Shifts in Stream Thermal Regimes of the Laurentian Great Lakes Basin: The Role of Rain-on-Snow Events. ESS Open Arch. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroczynski, S. A Comparison of Two Rain-on-Snow Events and the Subsequent Hydrologic Responses in Three Small River Basins in Central Pennsylvania. 2004. Available online: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/6656 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Maclean, R.A.; English, M.C.; Schiff, S.L. Hydrological and hydrochemical response of a small Canadian shield catchment to late winter rain-on-snow events. Hydrol. Process. 1995, 9, 845–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. The impact of rain-on-snow events on the snowmelt process: A field study. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e15019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L.; Lewis, G.; Krogh, S.A.; Drake, S.; Hanan, E.; Hatchett, B.J.; Harpold, A.A. Antecedent snowpack cold content alters the hydrologic response to extreme rain-on-snow events. J. Hydrometeorol. 2023, 24, 1825–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubilowicz, J.W. Hydrometeorology and Streamflow Response During Rain-on-Snow Events in a Coastal Mountain Region. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, J.W.; Gray, D.M.; Hedstrom, N.R. Prediction of snowmelt derived streamflow in a wetland dominated prairie basin. Hydrol. Res. 2012, 43, 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Storck, P.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Bolton, S.M. Measurement of snow interception and canopy effects on snow accumulation and melt in a mountainous maritime climate, Oregon, United States. Water Resour. Res. 2002, 38, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R.D.; Spittlehouse, D.L.; Golding, D.L. Measured differences in snow accumulation and melt among clearcut, juvenile, and mature forests in southern British Columbia. Hydrol. Process. 2005, 19, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygün, O.; Kinnard, C.; Campeau, S.; Pomeroy, J.W. Landscape and climate conditions influence the hydrological sensitivity to climate change in eastern Canada. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleakala, K.; Brandt, W.T.; Hatchett, B.J.; Li, D.; Lettenmaier, D.P.; Gebremichael, M. Watershed memory amplified the Oroville rain-on-snow flood of February 2017. PNAS Nexus 2022, 2, pgac295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, T.B.; Tague, C.L.; Molotch, N.P. The counteracting effects of snowmelt rate and timing on runoff. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhanang, S.M.; Frei, A.; Zion, M.; Schneiderman, E.M.; Steenhuis, T.S.; Pierson, D. Rain-on- snow runoff events in New York. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 3035–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, J.P.; Chandler, D.; Seyfried, M.; Achet, S. Soil moisture states, lateral flow, and streamflow generation in a semi-arid, snowmelt-driven catchment. Hydrol. Process. 2005, 19, 4023–4038. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, W.T.; Haleakala, K.; Hatchett, B.J.; Pan, M. A review of the hydrologic response mechanisms during mountain rain-on-snow. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 791760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Bisht, G.; Xu, D.; Kumar, M.; Leung, L.R. Divergent responses of historic rain-on-snow flood extremes to a warmer climate. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriano, Z.J. North American rain-on-snow ablation climatology. Clim. Res. 2022, 87, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, D.; Winstral, A.; Reba, M.; Pomeroy, J.; Kumar, M. Comparing spatial interpolation methods for snow water equivalent. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 3635–3644. [Google Scholar]

- Berghuijs, W.R.; Woods, R.A.; Hrachowitz, M. Rainfed snowpack dominates river runoff. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 3947–3967. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault, R.; Brissette, F.; Martel, J.L.; Troin, M.; Lévesque, G.; Davidson-Chaput, J.; Castañeda-Gonzalez, M.; Nachbaur, A.; Poulin, A. A comprehensive, multisource database for hydrometeorological modeling of 14,425 North American watersheds. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Geological Survey. National Water Information System (NWIS). 2023. Available online: https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. HYDAT: National Water Data Archive. 2023. Available online: https://collaboration.cmc.ec.gc.ca/cmc/hydrometrics/www/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North American Land Change Monitoring System. Commission for Environmental Cooperation. 2010. Available online: http://www.cec.org/tools-and-resources/north-american-environmental-atlas (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Wang, H.; Prentice, I.C.; Keenan, T.F.; Davis, T.W.; Wright, I.J.; Cornwell, W.K.; Evans, B.J.; Peng, C. Exploring complex water stress–GPP relationships: Impact of climatic drivers and interactive effects. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4110–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardina, F.; Konings, A.G.; Kennedy, D.; Alemohammad, S.H.; Oliveira, R.S.; Uriarte, M.; Gentine, P. Groundwater Rivals Aridity in Determining Global Photosynthesis. Research Square. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3793488/v1 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Just, A.C.; Liu, Y.; Sorek-Hamer, M.; Rush, J.; Dorman, M.; Chatfield, R.; Wang, Y.; Lyapustin, A.; Kloog, I. Gradient Boosting Machine Learning to Improve Satellite-Derived Column Water Vapor Measurement Error. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 13, 4669–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Just, A.; Mayer, M. SHAPforxgboost: SHAP Plots for “XGBoost”. 2023. Available online: https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.SHAPforxgboost (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, L.; Breuer, L.; Bach, M. Reproducibility of hydrological model performance: Should we expect more? Hydrol. Sci. J. 2019, 64, 1175–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Freudiger, D.; Kohn, I.; Stahl, K.; Weiler, M. Large-scale analysis of changing frequencies of rain-on-snow events with flood-generation potential. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 2695–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, J.D.; Dettinger, M.D.; Stewart, I.T.; Cayan, D.R. Variability and trends in spring runoff in the western United States. In Climate Warming in Western North America—Evidence and Environmental Effects; University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2009; pp. 63–76. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:37678150 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Þorsteinsson, R.Ó. Improving Spring Melt Calculations of Surface Runoff in the Upper Þjórsá River Using Measured Snow Accumulation. Master’s Thesis, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2015. Available online: https://skemman.is/bitstream/1946/23089/1/MS%20ritger%c3%b0-Reynir%20%c3%93li%20%c3%9eorsteinsson-loka.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Seybold, E.C.; Bergstrom, A.; Jones, C.N.; Burgin, A.J.; Zipper, S.; Godsey, S.E.; Dodds, W.K.; Zimmer, M.A.; Shanafield, M.; Datry, T.; et al. How low can you go? Widespread challenges in measuring low stream discharge and a path forward. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2023, 8, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Shanafield, M.; Kennard, M.J. Assessing the influence of zero-flow threshold choice for characterising intermittent stream hydrology. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, e15300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addor, N.; Melsen, L.A. Legacy, rather than adequacy, drives the selection of hydrological models. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Beck, H.E.; Lawson, K.; Shen, C. The suitability of differentiable, physics-informed machine learning hydrologic models for ungauged regions and climate change impact assessment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 2357–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, B.; Nadeau, D.F.; Dominé, F.; Wever, N.; Michel, A.; Lehning, M.; Isabelle, P. Impact of intercepted and sub-canopy snow microstructure on snowpack response to rain-on-snow events under a boreal canopy. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 2783–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juras, R.; Pavlásek, J.; Vitvar, T.; Šanda, M.; Hotový, O.; Kulasová, B.; Adamec, M. Isotopic tracing of the outflow during artificial rain-on-snow event. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, K.; Kittel, T.G.F.; Molotch, N.P. Observations and simulations of the seasonal evolution of snowpack cold content and its relation to snowmelt and the snowpack energy budget. Cryosphere 2017, 12, 1595–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselman, K.N.; Molotch, N.P.; Brooks, P.D. Effects of vegetation on snow accumulation and ablation in a mid-latitude sub-alpine forest. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 2767–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, J.W.; Gray, D.M.; Hedstrom, N.R.; Janowicz, J.R. Prediction of seasonal snow accumulation in cold climate forests. Hydrol. Process. 2002, 16, 3543–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würzer, S.; Jonas, T. Spatio-temporal aspects of snowpack runoff formation during rain on snow. Hydrol. Process. 2018, 32, 3434–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, T.; Slattery, M.C. Land use and land cover effects on runoff processes: Agricultural effects. In Encyclopedia of Hydrological Sciences; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, C.B.; Driscoll, C.T.; Green, M.B.; Groffman, P.M. Hydrologic flowpaths during snowmelt in forested headwater catchments under differing winter climatic and soil frost regimes. Hydrol. Process. 2016, 30, 4617–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R.; Biederman, J.A.; Broxton, P.D.; Pearl, J.K.; Lee, K.; Svoma, B.M.; van Leeuwen, W.J.D.; Robles, M.D. How three-dimensional forest structure regulates the amount and timing of snowmelt across a climatic gradient of snow persistence. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1374961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G.; Pomeroy, J.W. Early spring snowmelt in a small boreal forest watershed: Influence of concrete frost on the hydrology and chemical composition of streamwaters during rain-on-snow events. In Proceedings of the Eastern Snow Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 14–17 May 2001; Volume 58, pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Essery, R.; Pomeroy, J.W.; Ellis, C.; Link, T.E. Modelling longwave radiation to snow beneath forest canopies using hemispherical photography or linear regression. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 2788–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).