On the Occurrence of the Gar Obaichthys africanus Grande in the Cretaceous of Portugal: Palaeoecological and Palaeobiogeographical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological and Stratigraphic Settings

3. Materials and Methods

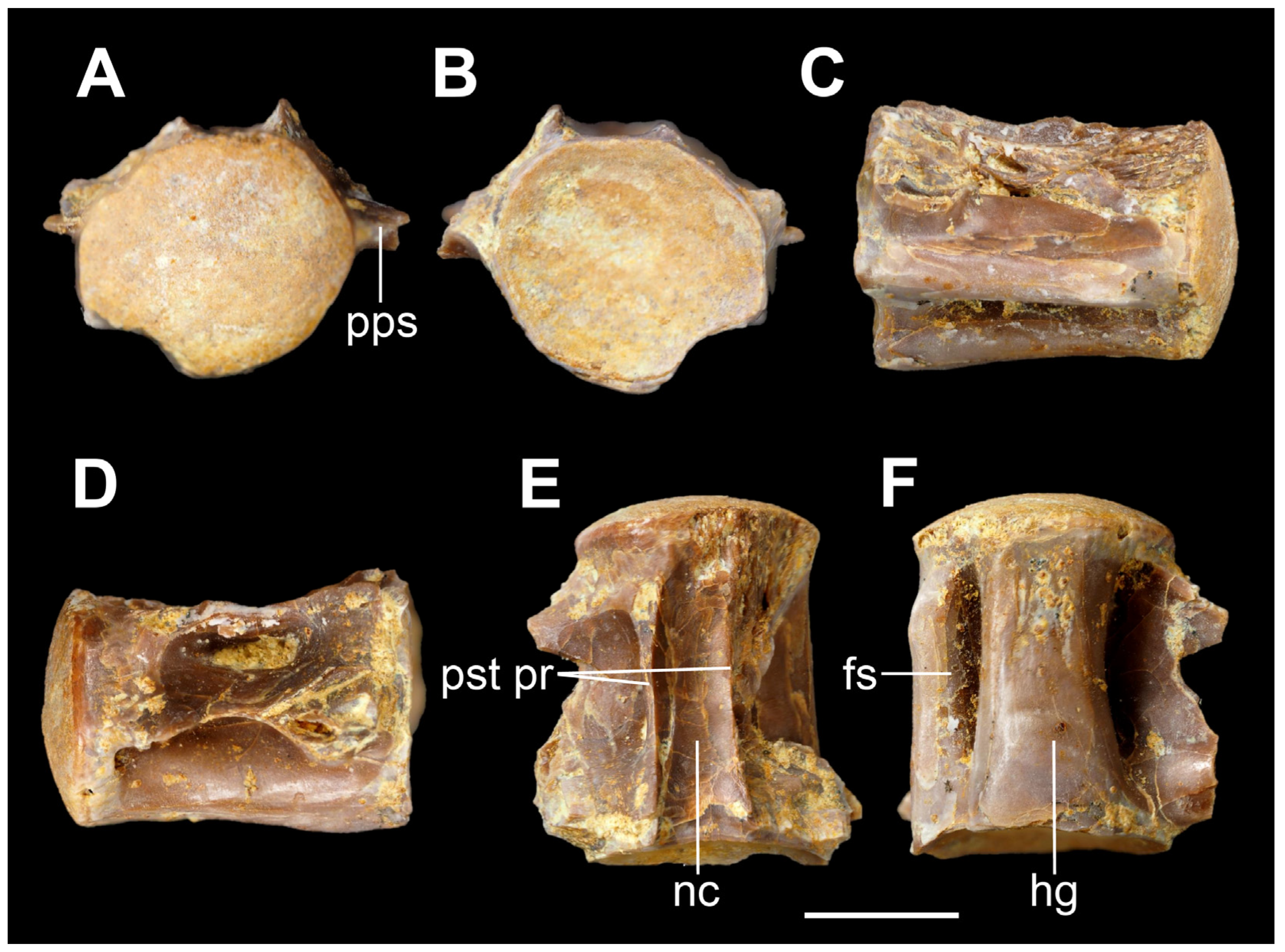

4. Material Description

5. Discussion

5.1. Taxonomic Remarks

5.2. Scales and Vertebral Centrum Position

5.3. Palaeoecology and Palaeogeography

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choffat, P.L. Recueil de Monographies Stratigraphiques sur le Système Crétacique da Portugal. Première étude, Contrées de Cintra, de Bellas et de Lisbonne; Section des Travaux Géologiques du Portugal: Lisbonne, Portugal, 1885; pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage, H.E. Vertébrés Fossiles du Portugal. Contributions à l’étude des Poissons et des Reptiles du Jurassique et du Crétacé; Direction des Travaux Géologiques du Portugal: Lisbonne, Portugal, 1897; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, J. Recherches géologiques sur le Crétacé inférieur de l’Estremadura (Portugal). Mem. Serv. Geol. Port. 1972, 21, 1–477. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, J. Le Crétacé inférieur de la marge atlantique portugaise: Biostratigraphie, organisation séquentielle, évolution paléogéographique. Ciências Da Terra 1979, 5, 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Berthou, P.Y. Le Cénomanien de l’Estrémadure portugaise. Mem. Serv. Geol. Port. N. S. 1973, 23, 1–169. [Google Scholar]

- Callapez, P.M.; Soares, A.F. Fósseis de Portugal: Amonóides do Cretácico Superior (Cenomaniano-Turoniano); Museu Mineralógico e Geológico da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2001; pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- Choffat, P.L. Recueil de Monographies Stratigraphiques sur le Système Crétacique du Portugal—Deuxième étude—Le Crétacé Supérieur au Nord du Tage; Direction des Services Géologiques du Portugal: Lisbonne, Portugal, 1900; pp. 1–287. [Google Scholar]

- Berthou, P.Y. Répartition stratigraphique actualisée des principaux foraminifères benthiques du Crétacé moyen et supérieur du Bassin Occidental Portugais. Benthos 1984, 83, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Berthou, P.Y. Résumé synthétique de la stratigraphie et de la paléogéographie du Crétacé moyen et supérieur du bassin occidental portugais. Geonovas 1984, 7, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Berthou, P.Y. Albian-Turonian stage boundaries and subdivisions in the Western Portuguese Basin, with special emphasis on the Cenomanian-Turonian boundary in the Ammonite Facies and Rudist Facies. Bulletin Geol. Soc. Den. 1984, 33, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.; Dinis, J.L.; Callapez, P.M.; Cunha, P.P. Da Rotura Continental à Margem Passiva. Composição e Evolução do Cretácico de Portugal. Cadernos de Geologia de Portugal; INETI: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Stromer, E. Die Topographie und Geologie der Strecke Gharaq-Baharije nebst Ausführungen über die geologische Geschichte Ägyptens. Abh. Math. Phys. Kl. K. Bayer. Akad. Wiss. 1914, 26, 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, W. Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltierreste der Baharîje-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman). Neue Untersuchungen an den Fishresten. Abh. Bayer. Akad. Der Wiss. Math.-Naturwissenschaftliche Abt. Neue Folge 1935, 32, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jonet, S. Contribution à l’étude des vertébrés du Crétacé portugais et spécialement du Cénomanien de l’Estrémadure. Com. Serv. Geol. Port. 1981, 67, 191–300. [Google Scholar]

- Jonet, S. Contribution à la connaissance de la faune ichthyologique crétacée. I-Éléments de la faune cénomanienne. Boletim Soc. Geol. Port. 1963, 15, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Jonet, S. Présence du poisson ganoïde Stromerichthys aethiopicus Weiler dans le Cénomanien portugais. Boletim Soc. Port. Ciências Nat. 1970, 13, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jonet, S. Considérations préliminaires sur des vertébrés cénomaniens des environs de Lisbonne. Boletim Soc. Geol. Port. 1971, 17, 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Cavin, L.; Boudad, L.; Tong, H.; Läng, E.; Tabouelle, J.; Vullo, R. Taxonomic composition and trophic structure of the continental bony fish assemblage from the early Late Cretaceous of southeastern Morocco. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, L. An empirical synthetic pattern study of gars (Lepisosteiformes) and closely related species, based mostly on skeletal anatomy. The resurrection of Holostei. Copeia Am. Soc. Ichthyol. Herpetol. Spec. Publ. 2010, 6, 1–871. [Google Scholar]

- Callapez, P.M. Estratigrafia e Paleobiologia do Cenomaniano-Turoniano. O significado do eixo da Nazaré-Leiria-Pombal. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Callapez, P.M. Palaeobiogeographic evolution and marine faunas of the Mid-Cretaceous Western Portuguese Carbonate Platform. Thalassas 2008, 24, 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Callapez, P.M.; Dinis, J.L.; Soares, A.F.; Marques, J.F. O Cretácico Superior da Orla Meso-Cenozóica Ocidental de Portugal (Cenomaniano a Campaniano Inferior). In Ciências Geológicas—Ensino Investigação e sua História; Cotelo Neiva, J.M., Ribeiro, A., Mendes Victor, L., Noronha, F., Ramalho, M.M., Eds.; Associação Portuguesa de Geólogos & Sociedade Geológica de Portugal: Braga, Portugal, 2010; Volume I—Geologia Clássica, Capter III—Paleontologia e Estratigrafia; pp. 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Berthou, P.Y.; Ferreira Soares, A.; Lauvervat, J. Portugal, in Mid Cretaceous Events Iberian field Conference 77, guide, I. Cuadernos Geol. Iber. 1979, 5, 31–124. [Google Scholar]

- Callapez, P.M. The Cenomanian-Turonian central West Portuguese carbonate platform. In Cretaceous and Cenozoic Events in West Iberia Margins Field Trip Guidebook 2; Dinis, J., Proença Cunha, P., Eds.; FCTUC: Coimbra, Portugal, 2004; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Callapez, P.M.; Barroso-Barcenilla, F.; Segura, M.; Soares, A.F.; Dinis, P.M.; Marques, J.F. The West Iberian Continental Margin. In The Geology of Iberia: A Geodynamic Approach; Quesada, C., Oliveira, J.T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 3: The Alpine Cycle, pp. 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, B.; Soares, A.F.; Rocha, R.B.; Manuppella, G.; Henriques, M. Carta Geológica de Portugal, Escala 1:50000. Notícia Explicativa da Folha 19A—Cantanhede; Serviços Geológicos de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 1988; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dinis, J. Definição da Formação da Figueira da Foz—Aptiano a Cenomaniano do sector central da margem oeste ibérica. Comun. Inst. Geol. Min. 2001, 88, 127–160. [Google Scholar]

- Choffat, P.L. Recueil d’études Paléontologiques sur la Faune Crétacique du Portugal, vol. II—Les Ammonées du Bellasien, des Couches à Neolobites Vibrayeanus, du Turonien et du Sénonien; Section des Travaux Géologiques du Portugal: Lisbonne, Portugal, 1898; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, A.F. Estudo das formações pós-jurássicas das regiões de entre Sargento-Mor e Montemor-o-Velho (margem direita do Rio Mondego). Memórias E Notícias 1966, 62, 1–343. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, A.F. Contribuição para o estudo do Cretácico em Portugal (o Cretácico superior da Costa de Arnes). Memórias E Notícias 1972, 74, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, A.F. A “Formação Carbonatada” na região do Baixo-Mondego. Com. Serv. Geol. Portugal 1980, 66, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Lauverjat, J. Le Crétacé Supérieur dans le Nord du Bassin Occidental Portugais. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso-Barcenilla, F.; Callapez, P.; Soares, A.F.; Segura, M. Cephalopod assemblages and depositional sequences from the upper Cenomanian and lower Turonian of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). J. Iber. Geol. 2011, 37, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- López-Arbarello, A. Phylogenetic Interrelationships of Ginglymodian fishes (Actinopterygii: Neopterygii). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuvier, G. Recherches sur les Ossements Fossiles, où l’on Rétablit les Caractères de Plusieurs Animaux dont les Révolutions du Globe ont Détruit les Espèces; Tome 3; G. Dufour et E. d’Ocagne: Paris, France, 1825; pp. 1–412. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, E.S. On the scales of fish, living and extinct, and their importance in classification. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1907, 77, 751–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, P.; Meunier, F.; Gayet, M. The morphology and histology of the scales of the Cretaceous gar Obaichthys (Actinopterygii, Lepisosteidae): Phylogenetic implications. Compt. Rend. l’Académie Sci. Earth Planet. Sci. Ser. IIA 2000, 331, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, F.J.; Eustache, R.P.; Dutheil, D.; Cavin, L. Histology of ganoid scales from the early Late Cretaceous of the Kem Kem beds, SE Morocco: Systematic and evolutionary implications. Cybium 2016, 40, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, O.P. Second bibliography and catalogue of the fossil Vertebrata of North America. Publ. Carnegie Instit. Wash. 1929, 390, 1–916. [Google Scholar]

- Wenz, S.; Brito, P. Découverte de Lepisosteidae (Pisces, Actinopterygii) dans le Crétacé Inférieur de la Chapada do Araripe (NE du Brésil): Systématique et phylogénie. Compt. Rend. l’Académie Sci. Paris Série II 1992, 314, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar]

- López-Arbarello, A.; Sferco, E. Neopterygian phylogeny: The merger assay. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 72337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, P.; Lindoso, R.; Carvalho, I.; Machado, P. Discovery of Obaichthyidae gars (Holostei, Ginglymodi, Lepisosteiformes) in the Aptian Codo Formation of the Parnaíba Basin: Remarks on paleobiogeographical and temporal range. Cret. Res. 2016, 59, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaste, N. Étude de restes de poissons du Crétacé saharien. Mémoire IFAN Mélanges Ichthyol. Tusin 1963, 68, 438–484. [Google Scholar]

- Cavin, L.; Tong, H.; Boudad, L.; Meister, C.; Piuz, A.; Tabouelle, J.; Aarab, M.; Amiot, R.; Buffetaut, E.; Dyke, G.; et al. Vertebrate assemblages from the early Late Cretaceous of southeastern Morocco: An overview. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2010, 57, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vullo, R. Les vertébrés du Crétacé Supérieur des Charentes (Sud-Ouest de la France): Biodiversité, taphonomie, paléoécologie et paléobiogéographie. Mémoires Géosci. Rennes 2007, 125, 1–302. [Google Scholar]

- Vullo, R.; Néraudeau, D. Cenomanian vertebrate assemblages from southwestern France: A new insight into the European mid-Cretaceous continental fauna. Cret. Res. 2008, 29, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torices, A.; Barroso-Barcenilla, F.; Cambra-Moo, O.; Pérez-García, A.; Segura, M. Palaeontological and palaeobiogeographical implications of the new Cenomanian vertebrate site of Algora, Guadalajara, Spain. Cret. Res. 2012, 37, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyoucef, M.; Läng, E.; Cavin, L.; Mebarki, K.; Adaci, M.; Bensalah, M. Overabundance of piscivorous dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) in the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa: The Algerian dilemma. Cret. Res. 2015, 55, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyoucef, M.; Pérez-García, A.; Bendella, M.; Ortega, F.; Vullo, R.; Bouchemla, I.; Ferré, B. The “mid”-Cretaceous (Lower Cenomanian) Continental Vertebrates of Gara Samani, Algeria. Sedimentological Framework and Palaeodiversity. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 927059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Sereno, P.; Varricchio, D.; Martill, D.; Dutheil, D.; Unwin, D.; Baidder, L.; Larsson, H.; Zouhri, S.; Kaoukaya, A. Geology and paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of eastern Morocco. ZooKeys 2020, 928, 1–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, A.; Bardet, N.; Fregenal-Martínez, M.A.; Martín-Jiménez, M.; Mocho, P.; Narváez, I.; Torices, A.; Vullo, R.; Ortega, F. Cenomanian vertebrates from Algora (central Spain): New data on the establishment of the European Upper Cretaceous continental faunas. Cret. Res. 2020, 115, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrocal-Casero, M. Ecosistemas del Cretácico de Guadalajara: De la Costa al mar; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Diputación Provincial de Guadalajara: Guadalajara, España, 2022; pp. 1–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaparte, C.L. Prodromus systematis ichthyologiae. Nuovi Ann. Delle Sci. Nat. Bologna 1835, 2, 181–196, 272–277. [Google Scholar]

- Esin, D. The scale cover of Amblypterina costata (Eichwald) and the palaeoniscid taxonomy based on isolated scales. Paleontol. J. 1990, 2, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus, C. Systema Naturæ: Per Regna tria Naturaæ, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis; Tomus 1; Editio Decima Reformata; Impensis Direct Laurentii Salvii: Holmi, Sweden, 1758; pp. 1–824. [Google Scholar]

- de Lacépède, B. Histoire Naturelle des Poisons; Tome 5; Plassan: Paris, France, 1803; pp. 1–392. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, M.E.; Schneider, J.G. Systema Ichthyologiae Iconibus CX Illustratum; Sumtibus Auctoris Impressum et Bibliopolio Sanderiano Commissum: Berolini, Germany, 1801; pp. 1–584. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, P.; Yabumoto, Y. An updated review of the fish faunas from the Crato and Santana formations in Brazil, a close relationship to the Tethys fauna. Bull. Kitakyushu Mus. Nat. Hist. Hum. Soc. Série A 2011, 9, 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga Ferreira, O. Fauna ictiológica do Cretácico de Portugal. Com. Serv. Geol. Port. 1961, 45, 251–278. [Google Scholar]

- Vullo, R.; Bernárdez, E.; Buscalioni, A. Vertebrates from the middle?-late Cenomanian La Cabaña Formation (Asturias, northern Spain): Palaeoenvironmental and palaeobiogeographic implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2009, 276, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutheil, D.B. An overview of the freshwater fish fauna from the Kem Kem beds (Late Cretaceous: Cenomanian) of southeastern Morocco. In A Mesozoic Fishes 2—Systematics and Fossil Record; Arratia, G., Tintori, A., Eds.; Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: Munich, Germany, 1999; pp. 553–563. [Google Scholar]

- Casier, E. Matériaux pour la Faune Ichthyologique Eocrétacique du Congo. Annales du Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale-Tervuren, Belgique, série 8. Sci. Géol. 1961, 39, 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, J.; Floquet, M. Late Cenomanian. In Atlas Peri-Tethys, Map 14; Dercourt, J., Gaetani, M., Vrielynck, B., Barrier, E., Biju-Duval, B., Brunet, M.F., Cadet, J.P., Crasquin, S., Sandulescu, M., Eds.; CVGM/CGMV: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stampfli, G.; Borel, G.; Cavazza, W.; Mosar, J.; Ziegler, P.A. The Paleotectonic Atlas of the Peritethyan Domain; European Geophysical Society: Munich, Germany, 2001; CD ROM ISBN 3-9804862-6-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gelabert, B.; Sàbat, F.; Rodríguez-Perea, A. A new proposal for the Late Cenozoic geodynamic evolution of the western Mediterranean. Terra Nova 2002, 14, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pimentel, R.; Barroso-Barcenilla, F.; Berrocal-Casero, M.; Callapez, P.M.; Ozkaya de Juanas, S.; dos Santos, V.F. On the Occurrence of the Gar Obaichthys africanus Grande in the Cretaceous of Portugal: Palaeoecological and Palaeobiogeographical Implications. Geosciences 2023, 13, 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences13120372

Pimentel R, Barroso-Barcenilla F, Berrocal-Casero M, Callapez PM, Ozkaya de Juanas S, dos Santos VF. On the Occurrence of the Gar Obaichthys africanus Grande in the Cretaceous of Portugal: Palaeoecological and Palaeobiogeographical Implications. Geosciences. 2023; 13(12):372. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences13120372

Chicago/Turabian StylePimentel, Ricardo, Fernando Barroso-Barcenilla, Mélani Berrocal-Casero, Pedro Miguel Callapez, Senay Ozkaya de Juanas, and Vanda F. dos Santos. 2023. "On the Occurrence of the Gar Obaichthys africanus Grande in the Cretaceous of Portugal: Palaeoecological and Palaeobiogeographical Implications" Geosciences 13, no. 12: 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences13120372

APA StylePimentel, R., Barroso-Barcenilla, F., Berrocal-Casero, M., Callapez, P. M., Ozkaya de Juanas, S., & dos Santos, V. F. (2023). On the Occurrence of the Gar Obaichthys africanus Grande in the Cretaceous of Portugal: Palaeoecological and Palaeobiogeographical Implications. Geosciences, 13(12), 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences13120372