Simple Summary

Tooth resorption is a common and painful dental condition in cats. Its causes, particularly in young brachycephalic cats, are not well understood. In this study of 166 cats, we evaluated the links between skull type, diet, and chronic oral inflammation and how they are related to disease severity. Brachycephalic cats (e.g., Persians) were younger but had already developed advanced lesions. In contrast, non-brachycephalic cats more frequently had chronic gingivostomatitis, which was not associated with increased tooth resorption. Cats fed premium diets showed a higher prevalence of severe lesions. Overall, these findings suggest that skull type and cat diet may have a stronger influence on tooth resorption. Although a direct cause cannot be proven, more research is needed to determine whether early dental checks and special diets can slow tooth resorption in cats.

Abstract

Tooth resorption (TR) is a common and painful dental disease in cats. The contributions of skull type, diet, and chronic gingivostomatitis (CGS) to its development remain unclear. We retrospectively reviewed 166 cats with TR confirmed radiographically to evaluate these associations. Brachycephalic cats (N = 33) were significantly younger than non-brachycephalic cats (7.1 ± 2.6 vs. 8.7 ± 3.8 years, p = 0.026) and had a higher prevalence of advanced Stage 4 TR lesions (p = 0.018). There was no significant difference between two groups of cats in sex distribution, diet type or wet food consumption. CGS occurred more often in non-brachycephalic cats (57.9% vs. 21.2%, p < 0.001) but was not associated with TR severity. In both skull groups, mandibular premolars and molars were most commonly affected (p < 0.01). Cats with owner-reported premium diets had more Stage 4 lesions (p = 0.013), particularly in non-brachycephalic cats but not in brachycephalic cats. These findings suggest that TR severity is associated with younger age and advanced lesions in brachycephalic breeds, as well as diet-related differences in non-brachycephalic cats. Further studies are warranted to evaluate early dental screening and targeted nutritional strategies to mitigate the progression of tooth resorption in cats.

1. Introduction

Feline oral diseases are common and clinically important in domestic cats. These include tooth resorption (TR), chronic gingivostomatitis (CGS), and periodontitis, with prevalence reported to vary across geographic areas and study populations [1,2,3,4,5]. TR is a progressive dental condition in which odontoclast-like cells resorb dental hard tissues. This process usually begins at the tooth roots and can extend into the crown [6]. The prevalence of TR increases with age in cats [2,6]. Archaeological evidence indicates that TR occurred in cats as early as the 13th and 14th centuries [7]. Accurate diagnosis is essential. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) provides greater accuracy than conventional dental radiography, which remains widely used due to its practicality and accessibility [8,9]. Emerging AI-assisted techniques may further enhance detection [10]. Affected teeth are classified into five stages and three radiographic types according to the American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC) system [11].

The pathogenesis of TR is multifactorial, involving cytokine-mediated odontoclastic activity [12], adhesion molecule expression [13], and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression [14]. Chronic oral inflammation and microbial imbalance also play important roles. Alterations in the oral microbiota can lead to dysbiosis and local inflammation, contributing to the development of feline TR (also known as FORL) [15]. Elevated inflammatory cytokines may contribute to odontoclast activation [16,17], and in cats with CGS, inflammation-driven shifts in the oral microbiota correlate with disease severity [18]. Breed-related craniofacial variations may predispose cats to TR [19], potentially interacting with local inflammatory mechanisms. These observations are further supported by studies showing that gingiva-derived mesenchymal stromal cells from cats with TR exhibit impaired proliferation, increased apoptosis and senescence, and altered cytokine expression, indicative of compromised tissue homeostasis [20]. Additionally, mast cell- and complement-mediated alveolar bone pathology may also contribute to disease progression [21]. Despite identified mechanism, the exact causes of TR remain unclear [22]. TR pathogenesis likely involves interaction among local inflammation, immune signaling, and cellular dysfunction.

Systemic factors, reflected by altered creatinine and globulin levels, have been associated with TR [23]. Low serum 25-OH-D (vitamin D3) is associated with an increased prevalence of multiple lesions [24], whereas excess dietary vitamin D may be the long-sought cause of multiple TR in domestic cats [25], highlighting that both deficiency and excess may influence dental health. Probiotics, though not directly studied in TR, modulate the feline oral microbiota and may indirectly support oral health [26], whereas diet—particularly dry kibble—reduces plaque and gingival inflammation, supporting periodontal health and potentially lowering TR risk [27]. Clinically, tooth extraction remains the treatment of choice, particularly in cases of pain, severe lesions, or functional impairment [6,28]. However, understanding the mechanisms driving disease progression remains essential for improving long-term outcomes. Therefore, the objective of this study was to retrospectively determine how skull type, diet, and CGS are associated with the severity of TR in cats. Relevant demographic and clinical factors recorded from the hospital database were also analyzed to identify potential contributors to TR progression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

This retrospective observational study was conducted using clinical records from cat patients diagnosed with TR at the Kasetsart University Veterinary Teaching Hospital (KUVTH), Bangkok, Thailand. Clinical records from March 2021 to August 2025 were retrospectively reviewed. Ethical approval was obtained from the Kasetsart University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; approval number #ACKU68-VET-105) and the Ethical Review Board of the Office of the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT license U1-07457-2561). Written informed consent was obtained from all owners before inclusion. All procedures complied with institutional animal welfare regulations and were conducted in accordance with the Kasetsart University guidelines for animal care and use.

2.2. Study Population

A total of 166 domestic cats diagnosed with TR during dental evaluations were included in this study. Cats were classified into two groups according to skull morphology. The brachycephalic group (N = 33) consisted of breeds such as Persian, Exotic Shorthair, and British Shorthair, characterized by a shortened facial structure and a broad skull base. The non-brachycephalic group (N = 133) included domestic shorthairs, Siamese, and other breeds exhibiting either mesocephalic or dolichocephalic skull types. Inclusion required complete clinical and dental records (Figure 1), a documented dietary history, and high-quality diagnostic full-mouth intraoral radiographs. Exclusion criteria included incomplete records, poor-quality radiographs, the presence of systemic illnesses known to affect bone metabolism (such as primary hyperparathyroidism or chronic kidney disease), or a history of dental extractions that could interfere with lesion assessment.

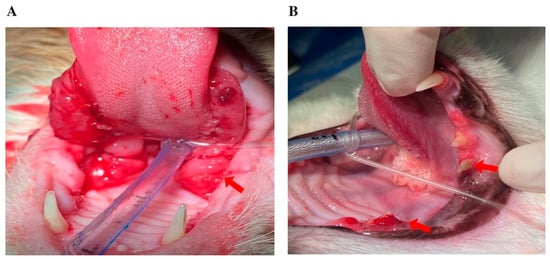

Figure 1.

Representative intraoral images of cats under general anesthesia, depicting: (A) severe, bilateral ulcerative lesions affecting the palatoglossal arches and caudal oral mucosa, consistent with chronic gingivostomatitis (arrows); (B) fractured and discolored teeth, with gingival inflammation suggestive of tooth resorption (arrows).

2.3. Data Collection and Radiographic Evaluation

Data were retrieved from the hospital’s electronic medical record system, including demographic information (age, sex, breed) and dental findings. Full-mouth intraoral radiographs were obtained under general anesthesia using the PORT-X IV Portable X-ray system (Genoray, Seongnam-si, South Korea) and the CR 7 Vet Image Plate Scanner (iM3 Dental Limited, Duleek, Ireland), following standardized hospital protocols. Lesions were classified by type (1–3) and stage (1–5) according to AVDC criteria [11]. The location of affected teeth was recorded, distinguishing maxillary versus mandibular involvement and identifying the specific tooth group (incisor, canine, premolar, or molar). The presence of CGS was determined from clinical examination and intraoral inspection (Figure 1). Representative clinical and radiographic images of CGS, periodontal disease, and TR lesions at different stages are presented in Figure 2. All radiographs were independently reviewed by three trained clinicians, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Formal inter-observer reliability testing was not performed and is acknowledged as a limitation. All evaluators followed standardized scoring criteria to ensure consistency and reduce variability in lesion classification.

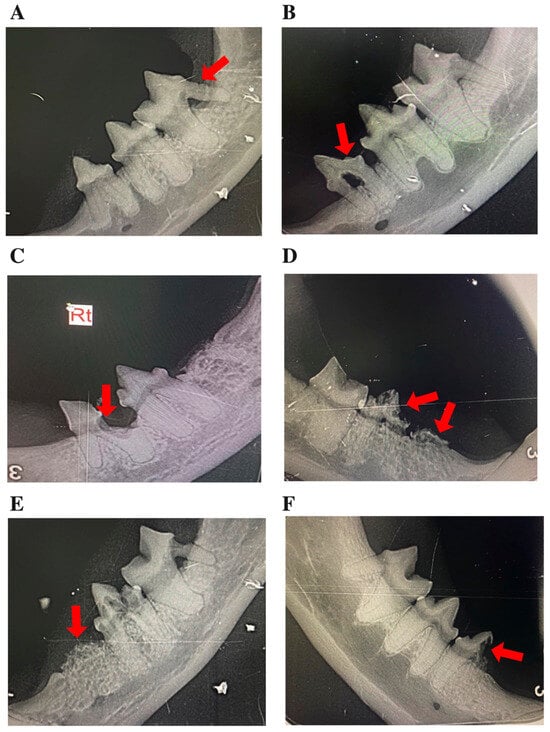

Figure 2.

Representative intraoral radiographs of mandibular premolars and molars in cats, depicting: (A–E) tooth resorption (TR) stages 1–5, illustrating the progressive loss of dental hard tissue, as indicated by arrows; and (F) a mixed lesion exhibiting features of both Type 1 and Type 2 TR (arrow). In panel C, “Rt” denotes the right side.

2.4. Dietary Assessment

Dietary histories were obtained from owners during admission interviews. Diets were classified into two categories premium and commercial based on a pragmatic distinction rather than detailed quantitative nutrient analysis. Premium diets were defined as well-known international brands containing higher-quality protein sources, whereas commercial diets comprised locally produced or OEM products with lower-quality protein sources and less established branding. Wet food consumption was recorded as a binary variable (yes/no).

For cats receiving mixed diets, classification was based on the predominant daily diet reported by owners when exact proportions were unavailable. This approach may have introduced recall bias, which is acknowledged as a limitation of the study.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA) and Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the clinical and demographic characteristics of feline patients. Number of teeth affected with different stages of TR was presented as the mean ± standard deviation and compared between two different skull types (brachycephalic vs. non-brachycephalic), two different diets (premium vs. commercial diets), and between cats with or without CGS using Student’s t-tests. Categorical variables (sex, CGS lesions, diet type, and wet food feeding) were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test, as appropriate. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In this retrospective study of 166 cats with TR, brachycephalic cats (N = 33) were significantly younger than non-brachycephalic cats (7.1 ± 2.6 vs. 8.7 ± 3.8 years, p = 0.026) (Table 1) and had more advanced Stage 4 TR lesions (p = 0.018). CGS was significantly more prevalent in non-brachycephalic cats (57.9% vs. 21.2%, p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed between the groups in sex distribution and lesion types. Other TR stages, diet type, and wet food consumption also did not differ significantly (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of brachycephalic and non-brachycephalic cats with tooth resorption (TR).

The distribution of teeth affected by TR was assessed in the brachycephalic and non-brachycephalic cats (Table 2). In brachycephalic cats, the mandibular molars were significantly more affected than maxillary molars (p < 0.01). In non-brachycephalic cats, the mandibular premolars and molars of mandible were more often affected than those in the maxilla (p < 0.01). No statistically significant differences were detected between skull types for individual tooth categories or jaw regions, indicating a consistent mandibular predominance regardless of craniofacial morphology.

Table 2.

Comparison of the number of teeth affected by tooth resorption (TR) in the maxilla and mandible of brachycephalic and non-brachycephalic cats.

When comparing TR severity between cats fed premium and commercial diets (Table 3), cats consuming premium diets had a significantly higher proportion of Stage 4 lesions (p = 0.013), whereas no significant differences were observed for Stages 1, 2, 3, or 5. This finding suggests that advanced TR tended to occur more frequently in cats fed premium diets, although overall lesion distribution remained similar between diet groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of the number of teeth affected by different stages of tooth resorption (TR) in the maxilla and mandible in cats fed commercial or premium diets.

The severity of TR was further analyzed in brachycephalic cats according to diet type (premium vs. commercial; Table 4). No statistically significant differences were observed at any lesion stage. There was a trend for Stage 3 lesions to be more frequent in cats fed commercial diets (7.8% vs. 4.2%, p = 0.077), whereas Stage 4 lesions tended to be slightly higher in cats fed premium diets (6.3% vs. 3.9%, p = 0.256). Overall, these trends did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that diet type was not strongly associated with TR severity in brachycephalic cats.

Table 4.

Comparison of the number of teeth affected by different stages of tooth resorption (TR) in the maxilla and mandible in brachycephalic cats fed premium or commercial diets. NS, not significant.

In contrast, within the non-brachycephalic group, cats fed premium diets exhibited a significantly higher number of Stage 4 lesions compared with those fed commercial diets (p = 0.020), suggesting a greater prevalence of advanced disease in this group (Table 5). No significant differences were observed between diet types for Stages 1, 2, 3, or 5, indicating that the earlier stages of TR were similarly distributed regardless of diet.

Table 5.

Comparison of the number of teeth affected by different stages of tooth resorption (TR) in the maxilla and mandible in non-brachycephalic cats fed premium or commercial diets.

Additionally, when comparing cats with and without CGS, no significant differences were observed in the number of teeth affected at any stage of TR (Table 6). Stage 1 lesions tended to be more common in cats without CGS (p = 0.053), but this trend did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that CGS was not associated with either the severity or prevalence of TR.

Table 6.

Comparison of the number of teeth affected by different stages of tooth resorption (TR) in the maxilla and mandible of cats with and without chronic gingivostomatitis (CGS).

4. Discussion

Skull morphology influenced TR severity in our study, with notable differences observed between brachycephalic and non-brachycephalic cats. While the prevalence of TR generally increases with age [2,6,29], we observed that even younger brachycephalic cats may develop disproportionately advanced (Stage 4) lesions. The brachycephalic conformation of Persian and Exotic cats is associated with unique oral and dental features that could predispose them to dental diseases, including tooth resorption [19]. However, other evidence indicates that the Exotic-Persian group may have a lower TR prevalence compared to house cats, whereas Cornish Rex, European, and Ragdoll cats show higher susceptibility [29]. These divergent findings indicate the variability in breed-related risk and emphasize the need for further research to elucidate the roles of craniofacial structure and genetics in TR progression. Regarding lesion distribution, mandibular premolars and molars were most frequently affected, consistent with previous reports identifying the mandibular fourth premolars as commonly involved [2,30].

CGS was more prevalent in non-brachycephalic cats in our cohort; however, it was not associated with greater TR severity, suggesting that oral inflammation alone does not fully account for lesion development. TR pathogenesis is multifactorial, with cytokine-mediated odontoclastic activity playing a central role [12], and dysbiosis of the oral microbiota potentially contributing to local inflammation [15]. In affected cats, pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated in saliva [16], while both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines are upregulated in gingival tissues [17], reflecting an inflammatory environment that may promote odontoclast activation. Locally produced 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, potentially enhanced by inflammation [31], likely drives odontoclast activity in TR, independent of serum vitamin D levels, as evidenced by upregulation of vitamin D receptor and target genes [32]. Abnormal blood parameters, including electrolyte imbalances, may reflect systemic effects associated with tooth resorption [33]. Overall, severe tooth resorption in cats arises from a complex interaction of microbial, immune, and systemic factors, with inflammation necessary but not sufficient on its own.

Diet type, particularly the distinction between dry kibble and wet food, is thought to play an important role in feline dental health. Dry kibble can reduce plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation through a mechanical cleaning effect, thereby potentially lowering the risk of oral diseases, including tooth resorption [27]. In our study, the comparison focused on diet quality (premium vs. commercial) rather than form. Non-brachycephalic cats fed premium diets exhibited more advanced TR lesions (Figure 3). This suggests that dietary composition and nutrient profile, rather than food texture alone, may influence the progression of TR lesion. Previous studies have indicated that cats with multiple TR lesions may have lower serum vitamin D3 concentrations, potentially promoting odontoclastic activity, even when consuming lifelong premium dry diets [24].

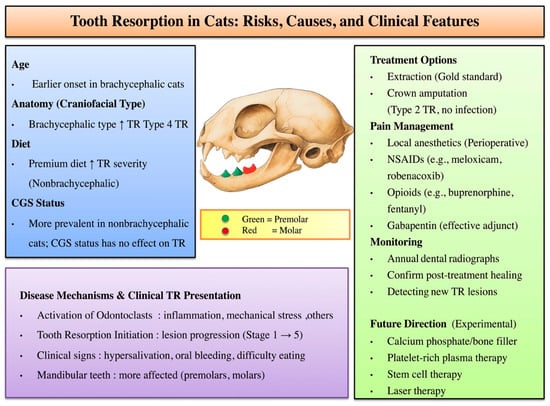

Figure 3.

Conceptual framework of TR illustrating major risk factors (age, skull type, and diet), lesion distribution, and clinical outcomes. Mandibular premolars (green) and molars (red) are most frequently affected. Proposed pathogenic pathways of TR development are presented, emphasizing odontoclast activation and the role of inflammatory mediators. Current treatment options and pain management strategies are outlined. Further development of targeted therapies and improved monitoring approaches is needed for TR. Upward arrows indicate an increase in risk or disease progression.

Many previous studies on TR have focused on cats from Western countries, whereas our study provides insights from an Asian cohort, where breed distributions and feeding practices may differ. These regional variations could influence the development and progression of TR through both genetic and environmental factors, highlighting the need for broader, population-based studies to better understand the disease’s multifactorial nature. In the present study, brachycephalic cats appear predisposed to faster TR progression, and diet may further exacerbate TR severity. Although CGS was more common in non-brachycephalic cats, it did not worsen TR. Figure 3 illustrates how inflammatory, dietary, and anatomical risk factors may converge to accelerate TR lesion development from Stage 1 through Stage 5. Current dental management focuses on extraction or crown amputation for Type 2 lesions, along with pain control using local anesthetics, NSAIDs, opioids, or gabapentin. Regular dental radiographs are essential to detect new TR lesions and confirm healing. Experimental treatments, such as calcium phosphate/bone fillers, platelet-rich plasma, stem cell therapy, and laser treatment, may offer future options for TR management (Figure 3).

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective design limits causal inference and control for confounding factors, including age, which was not adjusted for and may partially explain the higher prevalence of CGS in non-brachycephalic cats. Dietary assessment relied on owner reports and product labeling, precluding attribution of effects to specific nutrients such as vitamin D. Radiographic scoring lacked formal inter-observer reliability testing. Breed-specific genetic contributions to TR were not investigated, and outcomes were not compared between screened and unscreened cats. Moreover, the impact of home diet and home dental care were not evaluated. Despite these limitations, consistent trends across skull types and dietary groups support the robustness of our findings. Future prospective studies with larger, balanced cohorts should use age-adjusted, multivariable analyses. The effects of dental care, genetics, home diet, and systemic factors on severity of TR should also be evaluated.

6. Conclusions

This retrospective study revealed that brachycephalic cats develop more advanced TR at a relatively younger age compared to non-brachycephalic cats. The mandibular premolars and molars are the teeth most frequently affected, suggesting mandibular teeth as particularly susceptible sites for TR development. Although chronic gingivostomatitis was more prevalent in non-brachycephalic cats, it was not associated with TR severity, suggesting that CGS may not play a major role in TR progression. Premium diets were associated with greater TR severity in non-brachycephalic cats, although this relationship should be interpreted with caution given the retrospective design and reliance on owner-reported dietary information. Overall, the present findings support the roles of skull type, tooth location, and diet as potential contributors to TR development and progression in cats. Further studies are needed to evaluate the benefits of early dental screening in at-risk cats, as well as the potential role of specific nutritional interventions in reducing TR progression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization P.A. and N.T.; sample collection and data curation P.A., C.S. and P.J.; anesthesia monitoring and radiographic preparation E.M. and D.O.; writing—original draft preparation P.A.; software and statistical analysis P.A. and N.T.; review and editing P.A. and N.T.; supervision N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work did not receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures were approved by the Kasetsart University IACUC (ACKU68-VET-105) and conducted in accordance with NRCT ethical guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the owner of the animals.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of the cat’s owners and staffs at the Surgery Unit, Kasetsart University Veterinary Teaching Hospital (Bangkhen campus).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TR | Tooth Resorption |

| CGS | Chronic Gingivostomatitis |

| FORL | Feline Odontoclastic Resorptive Lesion |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

| MMP-9 | Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 |

| AVDC | American Veterinary Dental College |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

References

- Anderson, J.G.; Rojas, C.A.; Scarsella, E.; Entrolezo, Z.; Jospin, G.; Hoffman, S.L.; Force, J.; MacLellan, R.H.; Peak, M.; Shope, B.H.; et al. The oral microbiome across oral sites in cats with chronic gingivostomatitis, periodontal disease, and tooth resorption compared with healthy cats. Animals 2023, 13, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mivtach, E. Prevalence of tooth resorptive lesions in 120 feline dental patients in Israel. J. Vet. Dent. 2025, 42, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, P.; Yang, M.; Du, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, R.; Feng, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X. Epidemiological investigation of feline chronic gingivostomatitis and its relationship with oral microbiota in Xi’an, China. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1418101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Blenkarn, A.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Church, D.B.; Freeman, A. Periodontal disease in cats under primary veterinary care in the UK: Frequency and risk factors. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2023, 25, 1098612X231158154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Vallejo, M.; Vélez-Velásquez, P.; Correa-Valencia, N.M. Feline chronic gingivostomatitis: A thorough systematic review of associated factors. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2025, 27, 1098612X241310590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrel, C. Tooth resorption in cats: Pathophysiology and treatment options. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2015, 17, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Stich, H.; Hüster, H.; Roux, P.; Schawalder, P. Feline dental resorptive lesions in the 13th to 14th centuries. J. Vet. Dent. 2004, 21, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heney, C.M.; Arzi, B.; Kass, P.H.; Hatcher, D.C.; Verstraete, F.J.M. The diagnostic yield of dental radiography and cone-beam computed tomography for the identification of dentoalveolar lesions in cats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, J.; Denwood, M.; Nielsen, S.S.; McEvoy, F.; Allberg, C.; Thuesen, I.S.; Kortegaard, H. Accuracy of three diagnostic tests to detect tooth resorption in unowned unsocialised cats in Denmark. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2024, 65, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyquist, M.L.; Fink, L.A.; Mauldin, G.E.; Coffman, C.R. Evaluation of a novel veterinary dental radiography artificial intelligence software program. J. Vet. Dent. 2025, 42, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Veterinary Dental College. AVDC Nomenclature: Teeth Abnormalities and Related Procedures. Available online: https://avdc.org/avdc-nomenclature/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- DeLaurier, A.; Allen, S.; deFlandre, C.; Horton, M.A.; Price, J.S. Cytokine expression in feline osteoclastic resorptive lesions. J. Comp. Pathol. 2002, 127, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeyama, Y.; Grove, T.K.; Strayhorn, C.; Somerman, M.J. Expression of adhesion molecules during tooth resorption in feline teeth: A model system for aggressive osteoclastic activity. J. Dent. Res. 1996, 75, 1650–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Bush, S.J.; Thorne, S.; Mawson, N.; Farquharson, C.; Bergkvist, G.T. Transcriptomic profiling of feline teeth highlights the role of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) in tooth resorption. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Lappin, D.F.; Nile, C.J.; Spears, J.; Bennett, D.; Brandt, B.W.; Riggio, M.P. Microbiome analysis of feline odontoclastic resorptive lesion (FORL) and feline oral health. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 001353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Lappin, D.F.; Bennett, D.; Nile, C.; Riggio, M.P. Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in saliva of cats with feline odontoclastic resorptive lesion. Res. Vet. Sci. 2024, 166, 105092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Lappin, D.F.; Spears, J.; Bennett, D.; Nile, C.; Riggio, M.P. Expression of toll-like receptor and cytokine mRNAs in feline odontoclastic resorptive lesion (FORL) and feline oral health. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.A.; Soltero-Rivera, M.; Profeta, R.; Weimer, B.C. Case report: Inflammation-driven species-level shifts in the oral microbiome of refractory feline chronic gingivostomatitis. Bacteria 2025, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestrinho, L.A.; Louro, J.M.; Gordo, I.S.; Niza, M.M.R.E.; Requicha, J.F.; Force, J.G.; Gawor, J.P. Oral and dental anomalies in purebred, brachycephalic Persian and Exotic cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2018, 253, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltero-Rivera, M.; Groborz, S.; Janeczek, M.; Kornicka, J.; Wierzgon, M.; Arzi, B.; Marycz, K. Gingiva-derived stromal cells isolated from cats affected with tooth resorption exhibit increased apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress while experiencing deteriorated expansion and anti-oxidative defense. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2023, 19, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luntzer, K.; Lackner, I.; Weber, B.; Mödinger, Y.; Ignatius, A.; Gebhard, F.; Mihaljevic, S.-Y.; Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Kalbitz, M. Increased presence of complement factors and mast cells in alveolar bone and tooth resorption. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, A.M.; Mendoza, K.A. Feline odontoclastic resorptive lesions: An unsolved enigma in veterinary dentistry. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2002, 32, 791–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, A.; Tejedor, M.T.; Whyte, J.; Monteagudo, L.V.; Bonastre, C. Blood parameters and feline tooth resorption: A retrospective case control study from a Spanish university hospital. Animals 2021, 11, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, N.; Servet, E.; Hennet, P.; Biourge, V. Tooth resorption and vitamin D3 status in cats fed premium dry diets. J. Vet. Dent. 2010, 27, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, A.M.; Lewis, J.R.; Okuda, A. Update on the etiology of tooth resorption in domestic cats. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2005, 35, 913–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, Y.; Mei, X.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y. Effect of dietary composite probiotic supplementation on the microbiota of different oral sites in cats. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E. Comparative analysis of dental diseases in domestic cats fed different diets in Canada. J. Anim. Health 2024, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.G.; Kwon, D.; Lee, K.; Kim, S.E.; Jo, H.M. The prevalence of reasons for tooth extraction in cats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1626701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapalahti, K.; Neittaanmäki, H.; Lohi, H.; Virtala, A.-M. A large case-control study indicates a breed-specific predisposition to feline tooth resorption. Vet. J. 2024, 305, 106133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistor, P.; Janus, I.; Janeczek, M.; Dobrzyński, M. Feline tooth resorption: A description of the severity of the disease in regard to animal’s age, sex, breed and clinical presentation. Animals 2023, 13, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij-Vrieling, H.E. Tooth Resorption in Cats: Contribution of Vitamin D and Inflammation. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Booij-Vrieling, H.E.; Ferbus, D.; Tryfonidou, M.A.; Riemers, F.M.; Penning, L.C.; Berdal, A.; Everts, V.; Hazewinkel, H.A.W. Increased vitamin D-driven signalling and expression of the vitamin D receptor, MSX2, and RANKL in tooth resorption in cats. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2010, 118, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulat, S.; Parlak, K. Clinical, radiological and hematological evaluation in cats with tooth resorption. Dicle Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2025, 18, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.