Simple Summary

The body temperature of female cattle increases when they become sexually receptive (i.e., in estrus). Because higher estrus-associated temperatures (HEAT) persist for hours in cattle, direct effects on fertility-important components (i.e., the oocyte and surrounding cumulus cells) are unavoidable and functionally impactful. To test the hypothesis, direct and delayed effects of the physiologically relevant, 41 °C exposure during the early stages of oocyte maturation was evaluated by examining the impact on 47 different targeted transcripts. Most transcripts examined were impacted in the first 2 to 4 h of oocyte maturation. Moreover, the use of multidimensional scaling plots to ‘visualize’ samples provided further evidence that oocytes exposed to an acute elevation in temperature are more advanced at the molecular level during the initial stages of maturation. The consequences and role of the described impacts on the oocyte and its surrounding cumulus cells during maturation are discussed.

Abstract

Elevated body temperature (HEAT) in sexually receptive females is a normal part of the periovulatory microenvironment. The objective was to identify direct (first 6 h) and delayed (4 h or 18 h of recovery) effects at 41 °C exposure during in vitro maturation (IVM) on transcripts involved in steroidogenesis, oocyte maturation, or previously impacted by elevated temperature using targeted RNA-sequencing. Most transcripts (72.3%) were impacted in the first 2 to 4 hIVM. Twelve of the fifteen transcripts first impacted at 4 hIVM had a higher abundance and three had a lower abundance. Direct exposure to 41 °C impacted the transcripts related to progesterone production and signaling, germinal vesicle breakdown, oocyte meiotic progression, transcriptional activity and/or alternative splicing, cell cycle, cumulus expansion, and/or ovulation. Three transcripts demonstrated a delayed impact; changes were not seen until the COCs recovered for 4 h. The use of multidimensional scaling plots to ‘visualize’ samples highlights that oocytes exposed to an acute elevation in temperature are more advanced at the molecular level during the initial stages of maturation. Described efforts represent important steps towards providing a novel insight into the dynamic physiology of the COC in the estrual female bovid, during HEAT and after body temperature returns to baseline.

Keywords:

cumulus–oocyte complex; oocyte maturation; estrus; elevated temperature; HEAT; transcripts 1. Introduction

Higher estrus-associated temperatures (HEATs) are a hallmark feature in sexually receptive females even when thermoneutral conditions predominate [1]. The maximum level of HEAT typically coincides with the peak of the pivotally important luteinizing hormone (LH) surge [2,3,4], which induces the meiotic resumption and progression of the oocyte resident within the preovulatory follicle (i.e., oocyte maturation) and signifies the end of estrogen dominance, setting the stage for not only the beginning of corpus luteum formation but also ovulation some 26 to 30 h thereafter [5,6]. Although the magnitude and duration of HEAT varies among individual animals, Mills et al. [1] reported that 94% of suckled beef cows at the onset of the breeding season met the clinical definition of hyperthermia (>39.5 °C; [7]). Approximately 49.0% of cows in that study had vaginal temperatures > 40 °C which in some cases persisted up to 6.5 to 10 h, respectively [1]. In some but fewer instances, maximum HEAT exceeded 41.0 °C persisting up to 3.6 h.

When thermoneutral ambient conditions predominate, the level of HEAT and rectal temperature immediately before fixed timed AI have been positively related to fertility. For instance, a higher pregnancy outcome was reported in estrual cows that had rectal temperatures ranging from 38.7 to 40.5 °C immediately before artificial insemination compared to those with rectal temperatures ranging from 37.1 to 38.6 °C (73.5% vs. 60.2%, respectively [8]). When insemination was performed at a fixed time after administration of prostaglandin-F2α, a 1 °C increase in rectal temperature at the time of artificial insemination increased pregnancy odds 1.9 times [9].

Although the thermogenic component of estrus is short (average of 15.5 h, ranging from 6.2 to 26.2 h [1]) and ends well before ovulation would be expected [5,6], it is beyond intuitive for ovarian and follicle temperatures to become elevated during this pivotal developmentally important time. The temperature of the reproductive tract increases progressively toward the uterine horns [10], where the ovaries lie in the curvature. In pigs, Hunter et al. [11] showed that in instances where ovarian stromal tissue temperature was elevated during proestrus/estrus, the temperature of mature follicles was also elevated.

Regarding the potential to impact the cumulus–oocyte complex directly, exposure to an acute bout of an elevated temperature in vitro affects meiotic progression. Exposure to 41 °C for as few as 4 h promoted germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD; [12]). The heat-induced hastening of GVBD compared to thermoneutral controls coincided with decreased gap junction permeability between the oocyte and associated cumulus cells [13]. Furthermore, exposure to an acute physiologically relevant temperature increases the progesterone production by COCs [13,14,15]. Interestingly, progesterone supplementation to the culture medium stimulates bovine GVBD [16] and meiotic progression [17].

Impactful outcomes related to elevated temperatures are not limited to in vitro studies. An acute in vivo bout of hyperthermia occurring after a pharmacologically induced surge of LH and induced by heat stress, resulted in changes in the periovulatory follicular fluid proteome (e.g., proinflammatory-mediator bradykinin, negative acute phase protein-transferrin, interleukin 6 [IL6]) [18]. These findings are intriguing because others have shown the ability of these components to potentiate ovulation, affect oocyte–meiotic progression, and are granulosa and or cumulus cell products [19,20,21,22]. The analysis of the transcriptome, via the bulk RNASeq of the cumulus cells [23] that enveloped oocytes while contained within periovulatory follicles of females exhibiting varying degrees of hyperthermia, identified 25 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that increased or decreased with each 1 °C change in rectal temperature. Cumulus DEGs involved in cell junctions, plasma membrane rafts, and cell-cycle regulation are consistent with marked changes in the interconnectedness and the function of cumulus after the LH surge. Depending on the extent to which impacts are occurring at the junctional level, temperature-related changes in the cumulus may have indirect but impactful consequences on the oocyte as it resumes and undergoes meiotic maturation [13]. However, findings limited to a single time point (individual COCs were aspirated ~16 h after pharmacological induction of the LH surge [23]) well beyond initial stages of meiotic maturation, preclude further inference.

Mindful of what was known but compelled by what remained unknown about shorter exposure times, the overarching aim of the study described herein was to test the hypothesis that an acute bout of a physiologically relevant elevated temperature directly impacts COC-derived transcripts where corresponding protein product(s) may be involved or promote oocyte maturation, cumulus cell connectivity, expansion, and function (e.g., progesterone production). Heat exposure was limited for up to the first 6 h of in vitro maturation (2, 4, or 6 hIVM). To determine the extent to which heat-related consequences during early maturation may be delayed, transcript abundance in COCs was evaluated later in maturation and after recovery at 38.5 °C for 4 h (10 hIVM) or 18 h (24 hIVM). Examining the potential for the delayed impacts of an elevated temperature is important because these may contribute to the normal microenvironment after HEAT dissipates, which is yet to be described.

Targeted RNAseq was utilized to evaluate the transcript abundance. Doing so provided benefits from the dynamic range associated with next-generation sequencing-based quantification while being limited technically and monetarily by bulk RNAseq. Because targeted RNAseq enables the simultaneous investigation of transcripts, 20 of the cumulus derived transcripts identified by Klabnik et al. [23] that increased or decreased per each 1 °C change in rectal temperature were prioritized. Twenty-seven other transcripts previously shown to be impacted after in vitro heat stress exposure but for longer time periods [13,14,15] and known to be involved in oocyte maturation [14,15,23], cumulus expansion [14,23], and cumulus function [13,14,15,23] were also included. Having the opportunity to do so is of utmost importance because HEAT is an expected part of the normal ovarian preovulatory follicle environment in estrual females. It surprising how little is known about the intrinsic components/factors affected in the cumulus oocyte complex as it undergoes meiotic resumption and progression to metaphase II.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and In Vitro Maturation of Bovine Cumulus–Oocyte Complexes

No animals were used for this work. This study was completed using an estimated 228 abattoir-derived ovaries provided by Southeastern Provision, LLC (Bean Station TN, USA) that followed humane slaughter practices per USDA guidelines and located within 50 min of campus. Prevalent Bos taurus cattle breeds included Angus, Hereford, Charolais and Holsteins. Ovaries were evaluated in pairs upon the removal of the reproductive tract. The presence of a corpus luteum was preferred but not always present. Ovaries with several antral follicles that were not visually atretic (e.g., clear follicle fluid) were used for this study. Reagents and chemicals were obtained from MilliporeSigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise noted. Cumulus–oocyte complexes from abattoir-derived ovaries were collected during January and February and matured as previously described [24]. Oocyte collection and maturation media were prepared as previously described [25].

Ovarian antral follicles 3 to ~12 mm in size were preferentially targeted/slashed using a sterile scalpel blade. The avoidance of larger follicles with larger fluid volumes obviated concerns with collection medium clotting. The selection of COCs having a tight and compacted cumulus with an evenly granulated ooplasm selects against COCs that may have resumed meiosis in larger follicles in response to an endogenous LH surge. Towards this end, 100% of the visually uniform COCs evaluated to date have an intact germinal vesicle (GV [12,26]; 500+ COCs fixed and stained soon after removal from antral follicles). Using maturation conditions previously described [24], >90% of GV-intact COCs would be expected to progress to metaphase II and undergo other important critical maturation events (e.g., cytoplasmic changes in the oocyte and cumulus expansion [12,13,14,26,27]).

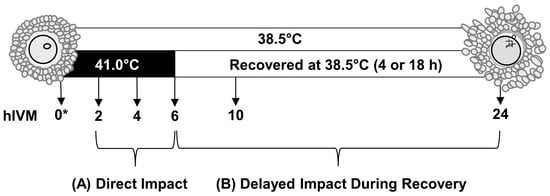

Cumulus–oocyte complexes with compact cumulus vestments and homogenous ooplasm underwent in vitro maturation in polystyrene tubes; Sarstedt AG and Co. Nümbrecht, Germany). Per each oocyte collection day (i.e., experimental replicate), COCs (n = 35 per 0.5 mL maturation medium; experimental unit) were cultured at 38.5 °C (thermoneutral) for 2, 4, 6, 10, or 24 hIVM (Figure 1). To examine the direct impact of a physiologically relevant elevated temperature, COCs were exposed to 41 °C for 2, 4, or 6 hIVM. To examine the possible delayed impacts, COCs were cultured at 41 °C for 6 hIVM and then transferred to 38.5 °C for an additional 4 h (10 hIVM total) or 18 h (24 hIVM total) of recovery. This ultimately resulted in a 2 × 5 factorial treatment arrangement. Whenever sufficient numbers were available (5 of the 6 days of COC collection), a subset of COCs was also processed soon after removal from antral follicles to provide a 0 hIVM group. Incubator temperatures were validated using internal mercury thermometers.

Figure 1.

Study schematic. To examine the direct impact of acute elevated temperature occurring in early maturation, subsets of cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs; n = 35 COCs per pool) were cultured for 2, 4, or 6 h of in vitro maturation (hIVM) at 41 °C. To examine how COCs recover from an acute exposure to elevated temperature occurring during early maturation (i.e., delayed impact), COCs were cultured at 41 °C for 6 hIVM and then allowed to recover at 38.5 °C for an additional 4 h (10 hIVM total) or 18 h (24 hIVM total). Subsets of COCs were cultured for 2, 4, 6, 10, or 24 hIVM at 38.5 °C for comparison. * Whenever sufficient numbers were present, a subset of COCs was also processed soon after removal from ovary to provide a 0 hIVM group.

Per each hIVM, COCs were removed from culture, washed in HEPES-TL containing 0.1% polyvinyl alcohol before lysis in extraction buffer (Quick-RNA Kit; Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Lysates were stored at −80 °C until RNA isolation [15]. This study was replicated on six different occasions and utilized a total of 2275 COCs.

2.2. Total RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was isolated using Quick-RNA Microprep kits (Zymo Research) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. DNAse treatment was performed on column with TURBO DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The concentration of RNA was determined using the Qubit RNA High Sensitivity assay (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Two COC pools were removed due to the low concentration of isolated RNA: one that was cultured at 38.5 °C for 4 hIVM and one that was processed at 0 hIVM. Isolated RNA was analyzed using RNA 6000 Nano kit on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer or a standard RNA Screen on an Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). RNA integrity number values ranged from 4.6 to 9.7 (mean ± standard deviation: 8.7 ± 0.1). Isolated total RNA (125 ng per pool of COCs) was converted to cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with oligo(dT)18 primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before storage at −80 °C.

2.3. Primer Design, Library Preparation, and Targeted Messenger RNA-Sequencing

Primers were designed using approximately 200 bp of sequence from the Bos taurus genome (Reference ARS-UCD1.2 Primary Assembly) with BatchPrimer3 to produce amplicons of 59 to 79 bp in length ([28]; Table 1). Only primer sets confirmed to span the exon–exon junction were utilized. Library preparation was performed on study cDNA in triplicate and sequenced using a Hi-Plex approach [29,30]. Targeted RNA sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq device using a 2 × 150 configuration [31] by Floodlight Genomics (Knoxville, TN, USA). Raw sequence reads were trimmed of identifiers using CLC Genomics Workbench version 9.5.3. The quality of the reads was assessed using FastQC software, Version 0.11.9 [32]. Trimming was performed with SeqPurge [33] and Trimmomatic [34]. The per sequence quality score measured in the Phred quality scale was above 25 on average for all the samples [32]. Reads were then aligned to the Bos taurus transcriptome (ARS-UCD1.2) and counted using Salmon [35]. The trimmed means of the M values method of data normalization was performed using the EdgeR package [36,37,38], resulting in counts per million (CPM). Transcripts were retained for further analysis only if there was >2200 CPM in a minimum of 24 of the technical triplicates. Raw counts were then normalized in EdgeR and RUVr (k = 4) as part of the RUVSeq package [39]. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plots of CPM reflecting either impacts of acute exposure to 41 °C in early maturation or subsequent recovery were generated with the Glimma package [40]. In the MDS plots, technical triplicates clustered closely together; therefore, the CPM of the technical triplicates for each transcript in each sample were averaged prior to statistical analyses.

Table 1.

Official gene symbols and nomenclature of the primer sequences used for targeted RNA sequencing.

2.4. Data and Statistical Analyses

In order to test hypotheses that each transcript may be directly impacted by an acute exposure to 41 °C in early maturation and may or may not recover later during later maturation, abundance (counts per million) of each transcript was analyzed individually as a randomized block design using generalized linear mixed models (PROC GLIMMIX, SAS 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), blocking on the day of COC collection. Fixed effects per each transcript model included IVM temperature (38.5 and 41.0 °C), hIVM, and the respective interaction (IVM temperature × hIVM). Using this approach allowed for alpha (i.e., Type I Error Rate) to be set at 0.05 [41]. The only transcript data that were not normally distributed per Shapiro Wilk’s was CAV1, which had a unique expression pattern related to hIVM, and shown in results. Therefore, CAV1 data were also analyzed as a 2 × 4 factorial treatment arrangement with eight treatment combinations (2, 4, 6, and 10 hIVM); in this arrangement, data were normal (W = 0.91). Per each transcript, treatment combination differences were determined using Fishers protected least significant differences [42] and are reported as least squares means ± standard error. Average abundance (counts per million) for each transcript in subsets of COCs evaluated at 0 hIVM are provided for visual comparison but were not included in statistical analyses.

3. Results

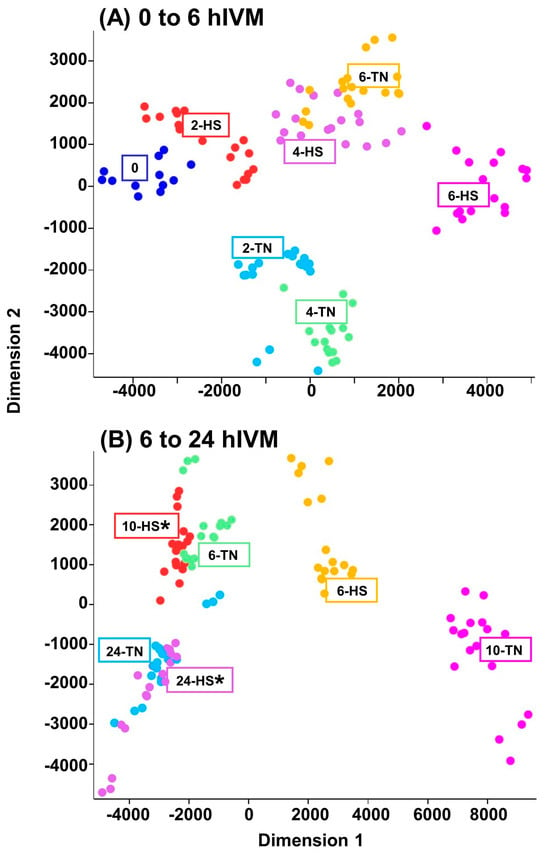

Multidimensional scaling plots representing each in vitro maturation time and temperature treatment combination and performed in triplicate are provided in Figure 2. Differences in clustering related to time and temperature in early maturation were apparent. Interestingly, and relevant for the first 6 hIVM, samples originating from COCs directly exposed to 41 °C for 4 hIVM overlapped with those matured at 38.5 °C for 6 hIVM (Figure 2A). When allowed to recover at 38.5 °C for 4 h, samples originating from COCs directly exposed to 41 °C for 6 hIVM (10-HS in Figure 2) began to overlap with those matured at 38.5 °C for 6 hIVM (Figure 2B). Samples from COCs directly exposed to 6 h of 41 °C but not allowed any recovery time clustered between those originating from COCs matured at 38.5 °C for 6 and 10 hIVM. By 24 hIVM, however, samples from COCs matured at 38.5 °C (24-TN in Figure 2) versus those that were directly exposed to 41.0 °C for the first 6 hIVM but allowed to recover for a total of 18 h at 38.5 °C (24-HS in Figure 2) clustered with the most overlap (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Multidimensional scaling plots highlighting differences in counts per million that resulted from efforts to examine abundance of 47 different targeted transcripts in cumulus–oocyte complexes. (A) COCs were cultured at 38.5 (Thermoneutral-TN) or 41 °C (Heat Shock-HS) for the first 2, 4 or 6 hIVM; 0 hIVM were included as a reference; (B) COCs were matured at 41 °C for 6 hIVM (6-HS) or allowed to recover at 38.5 °C for 4 h (10-HS*) or 18 h (24-HS*), thereafter in comparison to COCs cultured at 38.5 °C for 6, 10, and 24 hIVM (TN).

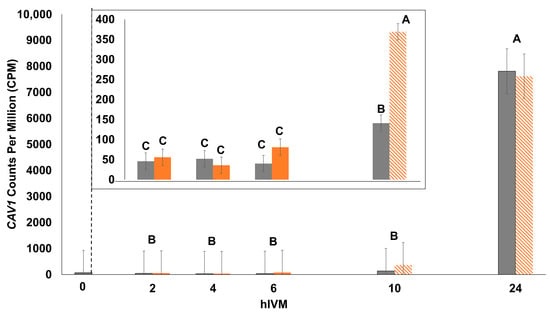

The abundance of the majority of individual transcripts (43 out of 47 total examined) differed depending on hIVM and IVM temperature (hIVM * IVM temperature interaction; p ≤ 0.05; Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). The first hIVM in which IVM temperature impacted transcripts with described roles in progesterone production and/or signaling, cellular signaling, the β-catenin complex, the cell cycle, or cumulus expansion is provided in Table 2. Table 3 includes the first hIVM where IVM temperature impacted abundance of Src Family Kinase transcripts. Whereas Table 4 lists the first hIVM where IVM temperature impacted the abundance of transcripts with less defined roles in the COC but they, or their gene products, were reported by others to have been impacted by heat in cumulus cells, the oocyte, and/or in the follicular fluid. Due to the range of counts per million, CAV1 data were not normally distributed when analyzed as a 2 × 5 factorial treatment arrangement and only hIVM was significant (p < 0.0001; Figure 3). When only the earlier hIVM were included in the model (i.e., 2, 4, 6, and 10 hIVM), data were normal and the interaction was significant (hIVM * IVM temperature p < 0.0001; Figure 3 Inset).

Table 2.

Impacts of IVM temperature (38.5 or 41.0 °C) by hIVM on abundance (counts per million) of COC transcripts involved in progesterone production/signaling, cellular signaling, β-catenin complex, cell cycle and cumulus cell expansion: Direct impact of 41.0 °C on first 6 hIVM versus delayed impact occurring after 4 (10 hIVM) or 18 (24 hIVM) h of recovery.

Table 3.

Impact of IVM temperature (38.5 or 41.0 °C) by hIVM on Src-Family Kinase transcript abundance (counts per million) in cumulus–oocyte complexes: Direct impact of 41.0 °C on first 6 hIVM versus delayed impact occurring after 4 (10h IVM) or 18 (24 hIVM) h of recovery.

Table 4.

Impacts of IVM temperature (38.5 or 41.0 °C) by hIVM on abundance (counts per million) of COC transcripts found to be significantly affected by temperature in cumulus, oocyte, and/or follicular fluid in other published studies: Direct impact of 41.0 °C on first 6 hIVM versus delayed impact occurring after 4 (10 hIVM) or 18 (24 hIVM) h of recovery.

Figure 3.

Impact of 41.0 °C exposure during the first 6 hIVM on CAV1 count per million (CPM) of cumulus–oocyte complex (COC). COCs were cultured at 41.0 °C for 2, 4, or 6 hIVM (orange bars), or allowed to recover at 38.5 °C for an additional 4 h (10 hIVM) or 18 h (24 hIVM; hashed bars as indicated by 41 °C). Thermoneutral COCs were cultured at 38.5 °C for 2, 4, 6, 10, or 24 hIVM (gray bars). Bars (least squares means ± SEM) with different letters differ significantly for hIVM. Temperature and the interaction of maturation temperature and hIVM was not significant. The inset reflects differences when data were analyzed with only the 2, 4, 6, and 10 hIVM timepoints. Bars with different letters (i.e., A through C) through differ significantly for the interaction of maturation temperature and hIVM. COCs at 0 hIVM were included as a reference.

Interestingly, 19 out of the 43 transcripts examined (44.1%) were impacted by 41 °C exposure after only 2 hIVM (6 were of higher abundance versus 13 of lower abundance; Table 5). Of the 15 transcripts with a first noticeable impact at 4 hIVM, 12 were of higher abundance whereas 3 were of lower abundance. Altogether, 34 (79.1%) and 40 (93.0%) out of 43 transcripts were first noticeably impacted by 4 and by 6 hIVM, respectively.

Table 5.

The earliest time period when 41 °C exposure for a maximum of 6 h first impacted the abundance of 43 different transcripts.

Pertaining to the four other transcripts examined (TFRC, CCDC80, SNAP91, and RAI14); TFRC was impacted by the IVM temperature (p = 0.004) and hIVM (p = 0.007). The only impact on CCDC80 was hIVM (p < 0.0001) but not IVM temperature (p = 0.5). Similarly, SNAP91 was impacted by hIVM (p = 0.0003) but not IVM temperature (p = 0.5). Although RAI14 was present (24,958 to 28,129 CPM), it was not impacted by hIVM (p = 0.4) or IVM temperature (p = 0.9).

4. Discussion

An overarching aim of the novel study described herein was to test the hypothesis that a short, acute bout of a physiologically relevant elevated temperature directly impacts COC-derived transcripts where corresponding protein product(s) may be involved in or affecting cumulus cell connectivity, expansion, and or function (e.g., progesterone production, cell signaling, cell cycle, β-catenin complex or other) which may indirectly or directly promote oocyte maturation. Allowing time for COCs to recover after heat exposure provided the additional opportunity to identify changes, if any, that may contribute to the normal microenvironment in the cow after HEAT dissipates. Deliberate effort to do this study during winter and abruptly expose naïve COCs to short bouts of heat “shock” in vitro, while not perfect, is necessary to gain new knowledge about possible intrinsic physiological events that may be occurring at the level of the cumulus to mediate meiotic resumption and progression of the oocyte, especially in circumstances where developmental outcomes are expected to be favorable.

When COCs were exposed to a short bout of heat in our study, the surrounding cumulus cells were intimately associated with the oocyte, projecting through the zona pellucida and into the oolemma via gap junctions [43]. Intimate connections with the oocyte permit bidirectional exchange of small molecules [44]. Cumulus presence is essential for meiotic resumption and the developmental progression thereafter [45,46]. Even after gap junctional connections breakdown, cumulus cells continue to envelop the oocyte providing critical support [47]. Thus, COCs remained intact before lysis.

Collectively, novel results described herein highlight direct and delayed effects on transcript abundance after short bouts of elevated temperature (i.e., 2, 4, or 6 h) were applied during the beginnings of oocyte maturation (i.e., meiotic resumption through GVBD). Of the 47 transcripts examined, 44 were impacted by heat with direct impacts noticed as early as 2 hIVM (majority of transcripts were affected after a 4 h exposure). Specific to impacts on the 20 in vivo-derived cumulus transcripts identified by Klabnik et al. [23] where abundance increased or decreased per each 1 °C change in rectal temperature of hyperthermic cows, 17 whose protein products are known to be involved in cell junctions, plasma membrane rafts, and cell-cycle regulation and other functions were directly impacted by heat as early as 2 and 4 hIVM.

Cumulus cells are transcriptionally active [48] and likely contribute much of the heat-related findings described herein. Despite having few to no LH receptors initially, cumulus begins to produce progesterone as oocyte maturation progresses [49,50]. In contrast, the transcriptionally quiescent oocyte relies on a depleting pool of maternal RNA and proteins after meiotic resumption [51,52]. Oligo-dT primers were used in our study to ascertain changes in transcript abundance likely to have a functional consequence [53]. The abundance patterns of certain transcripts (e.g., MMP9, CAV1, and IL6R) in COCs in our study were highly repeatable with patterns previously observed in COCs or cumulus cells alone after exposure for 12 h to 41 °C [14,15].

Interestingly, many of the targeted transcripts affected by heat exposure after 2 h were lower in abundance, whereas those affected by heat after 4 h were mostly higher in abundance. To gain a better perspective of these outcomes, COC samples were ‘visualized’ using multidimensional scaling. Remarkably, the targeted ‘transcriptome’ in COCs exposed to 41 °C for 4 h was more like the targeted transcriptome in COCs matured at 38.5 °C for 6 hIVM. The targeted transcriptome in COCs exposed to 41 °C for 6 h was in between that of COCs matured for 6 and 10 h at 38.5 °C. This finding is the first we are aware of to document a heat-induced shift at the transcriptomic level in the COC when considering numerous transcripts simultaneously within the same sample. Although the functional consequences of this molecular signature remain unclear, it is remarkable that the timing of the heat-induced shift in the targeted transcriptome overlaps/fits well with previous observations showing that the direct exposure of COCs to 41 °C for as few as 4 h promoted earlier germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD; i.e., heat shocked oocytes underwent GVBD sooner and mature faster than thermoneutral controls; [12]). The follow-on efforts of Campen et al. [13] confirmed that the heat-induced hastening of GVBD in vitro coincided with decreased gap junction permeability between the oocyte and associated cumulus cells. Relevant for meiotic progression and subsequent development, in vitro exposure to 41 °C for up to 6 hIVM directly promotes GVBD [12,13,26] without negative impacts on meiotic progression to metaphase II [12,26] or early embryo development after fertilization [15,54,55]. Mindful of this, it is unsurprising that the 24 hIVM samples (COCs exposed to 38.5 °C and 41 °C for the first 6 hIVM but recovered for 18 h) overlapped on the multidimensional scaling plot. Depending on the extent to which HEAT exposure in vivo may be shifting developmentally important processes, additional effort may be needed to investigate insemination timing in circumstances where body temperature elevations are more pronounced and persist for a longer time.

A member of the Src-family kinases, FYN, was differentially expressed in the in vivo-derived cumulus transcripts identified by Klabnik et al. [23] in cows exhibiting varying levels of hyperthermia. This finding was especially intriguing because members of the Src-family have a large degree of functional overlap [56] and may impact meiotic maturation. Follow-on efforts in our study identified four Src-family kinases that were directly impacted by exposure to 41 °C (SRC, FYN, LCK, and FGR). Greater abundance in SRC at 2 hIVM and LCK at 4 hIVM were particularly notable. Although the significance of these findings remain unclear, others have shown that non-specific Src-family kinase inhibitors reduce GVBD (rats: [57]; mice: [57,58]; porcine: [59]). Src induces GVBD by binding to the progesterone receptor in Xenopus oocytes [60], whereas FYN has been shown to promote GVBD in mice [61].

Progesterone production by the cumulus cells increases as in vitro oocyte maturation progresses [13,14] and levels are higher after heat exposure [13,14,62]. Heat-induced increases in progesterone production may be related to changes in transcript abundance [13,14,15]. Interestingly, samples exposed to heat had a lower abundance of FDX1 and FDXR but a higher abundance of HSD3B7 at 2 and 4 hIVM. FDX1 and FDXR encode enzymes that donate electrons, perpetuating catalytic activity, to cytochrome p450 enzymes such as p450scc, which convert cholesterol to pregnenolone in the process of steroidogenesis. Pregnenolone is converted to progesterone by 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3βHSD, [63]).

The consequences of exposure to elevated temperature on progesterone signaling remain unclear. Genomic pathways of progesterone signaling rely upon HSP90 protein chaperones [64] in which progesterone binds to its nuclear receptors (PRα and PRβ) to regulate the transcription [65]. Herein, heat exposure altered HSP90AB1 and HSP90B1 transcript abundance throughout maturation which may impact progesterone signaling via traditional pathways. It was recently reported that heifers with a negative fertility breeding value had an increased expression of HSP90B1 in COCs collected near estrus [66]. However, progesterone signaling may also occur through non-genomic, membrane-bound progesterone receptors (PGRMC1 and PGRMC2; [65]); PGRMC2 transcript levels were impacted throughout oocyte maturation by heat beginning at 2 hIVM. Collectively, results suggest a role of progesterone and its downstream events in changes to COC physiology observed during IVM and in vivo maturation after short-term heat exposure.

It is possible that MMP9 was impacted by increased progesterone production by COCs exposed to physiologically relevant elevated temperature [13,14,15] as transcript abundance was lower in recovering COCs despite an initial higher abundance at 4 hIVM at 41 °C. Progesterone was inversely related to MMP9 levels in COCs exposed to 41 °C for 12 h [62] and suppressed MMP9 secretion in other cell types (cervical fibroblasts: [67]; placental cells: [68]). Rispoli et al. [14] reported similar findings regarding COCs that recovered from a 12 h exposure to 41 °C in early maturation. Decreased MMP9 coincided with a decreased secretion of the proMMP9 enzyme, which negatively impacted embryo development in bovines [14] and humans [69]. However, developmental competence was not rescued by the supplementation of the human proMMP9 [62].

Interleukin 6 (IL6) is promoted by progesterone production and may regulate COC function, cumulus expansion, and oocyte developmental competence [21]. In the current study, IL6R decreased over time, consistent with the outcomes from Rowinski et al. [15]. The binding of IL6 to its receptor can induce the JAK-STAT pathways [21] and CCDC80 increases the phosphorylation of STAT3 [70]. Interestingly, CCDC80 had a similar pattern of expression to IL6R (i.e., decreased through the first 10 hIVM), despite not being affected by temperature. The decline in CCDC80 may be functionally important as CCDC80 is positively regulated by estrogen in the uterus and mammary gland [71], estrogen declines in the follicle after the LH surge [72], and the addition of estrogen during in vitro maturation inhibited bovine oocyte nuclear maturation [73].

Another pathway that can be induced by IL6 is ERK1/2 signaling [21], which may be involved in gap junction communication and progesterone production [74,75,76]. The proportion of active ERK1/2 in cumulus cells increased in early maturation [13]. This was not reflected in the levels of MAPK3 transcripts (i.e., the gene encoding ERK2) within COCs in the current study, which were relatively stable during early maturation with heat-induced reductions at 6 hIVM. Alternatively, AMPK may also affect gap junction communication through the control of protein synthesis and progesterone production [50,77]; the gene encoding AMPK (PRKAA1) had a lower abundance under the exposure to 41 °C at 6 hIVM in the current study. Campen et al. [13] reported that AMPK peaked at 6 hIVM in COCs under thermoneutral conditions and culture at 41 °C tended to a lower active AMPK. This further supports the notion that a decline in AMPK, which may have a role in accelerated meiotic progression [50], could be due to elevated temperature.

The upregulation of TNIK in samples exposed to 41 °C for 4 h in the current study coincides with the timing of the earlier expression of IL6 and its signal transducer [15]. Others have reported that IL6 promoted the interaction of the TNIK/β-catenin/TCF4 complex (multiple myeloma cells: [78]); transcriptional activity of the β-catenin/TCF4 complex is promoted by TNIK [79] and inhibited by SF1, which induces an alternative splicing activity [80]. The timing of TNIK’s higher abundance coincides with a lower level of SF1, suggesting a shift towards earlier transcription. The abundance of SF1 transcripts was higher at 6 h in samples exposed to 41 °C, which suggests changes in alternative splicing during maturation. Furthermore, the estrogen receptor ESR2 may be alternatively spliced by β-catenin to an isoform with dominant negative activity (HeLa cells: [81]). In the current study, ESR2 was present throughout maturation and was of higher abundance when exposed to 41 °C at various hIVM. Prior to the LH surge, estrogen signaling maintains the oocyte in meiotic arrest [82] and the addition of estrogen during in vitro maturation inhibited bovine oocyte nuclear maturation [73]. Altogether, it is possible that that exposure to elevated temperature increases progesterone production [13,15] to promote/accelerate IL6 production [15,21], resulting in altered regulation β-catenin/TCF4 complex activity (through TNIK and SF1) to stimulate transcription and subsequently the alternative splicing of ESR2. The potential alternative splicing of ESR2 to a dominant negative form could possibly then allow for the nuclear maturation of the oocyte, despite the presence of the receptor mRNA throughout maturation.

The unique cell type of the cumulus versus the oocyte when analyzed as a complex creates difficulty in concluding the impacts of exposure to 41 °C during maturation on cell cycle regulation. Transcripts that are generally thought to have a role in cell cycle regulation may be of importance because, while the oocyte is undergoing nuclear maturation (but not DNA replication), the cumulus cells may no longer be mitotically active [83]. The cumulus cell MDM2-p53-NR5A1 pathway was previously described to impact oocyte quality, ovulation, and fertilization [84], where the increased expression of MDM2 and NR5A1 were correlated with positive outcomes. In the current study, MDM2 had lower levels of abundance when exposed to directly elevated temperature at 2 and 4 hIVM which could possibly relate to higher levels of BANP, a stabilizer of p53 [85], at 4 and 6 hIVM. While this could indicate a negative impact on the oocyte, NR5A1 had higher abundance when exposed to 41 °C for the majority of pairwise comparisons, suggesting the opposite. Furthermore, TP53 was only impacted by elevated temperature at 4 hIVM. In contrast, bovine cumulus cell BANP expression was decreased in response to a 12 h heat exposure at 16 h maturation in vivo [23] and at 24 h maturation in vitro [14]. Differences may be attributed to the fact that RNA was extracted from the entire COC in the current study, compared to only cumulus cells in Haraguchi et al. [84], Klabnik et al. [23], and Rispoli et al. [14]. Lower levels of PAK2 when exposed to 41 °C at 2 hIVM in the current study could potentially contribute to the heat-induced hastening of GVBD and progesterone production [13]. PAK2 maintains Xenopus oocyte meiotic arrest [86] and inhibits progesterone production in human granulosa cells [87]. The elevated levels of ARHGAP6 and ARHGAP31 and lower levels of MCM6 in early maturation when exposed to 41 °C may indicate the cessation of cell cyclicity. ARHGAPs inactivate GTPases to halt mitosis and cytoskeletal rearrangement [88]. The helicase complex that contains MCM6 is critical to DNA replication [89]. The complexity of the relationship between cumulus and oocyte as maturation events occur requires further study, independently of the effect of heat.

Three transcripts analyzed in the current study have been reported to positively impact cumulus expansion: FSHR, INHBB, and PRDX2. At the majority of hIVM in the current study, the abundance of FSHR was lower in COCs exposed to 41 °C but INHBB had a higher abundance. Cumulus expansion in bovine oocytes was induced by FSH and higher levels of FSHR were present in better quality COCs [90]. INHBB enabled FSH-induced cumulus cell expansion (mouse: [91]) and its expression increased from GV to MII stage in bovine oocytes [92]. In the current study, when exposed to 41 °C, PRDX2 had a lower abundance at 2 hIVM and after 4 h of recovery (10 hIVM), but higher abundance at 6 hIVM. A cumulus expansion was promoted by PRDX2 in mice [93]. Previously, an acute hyperthermia decreased PRDX2 in bovine cumulus cells ~16 h after a pharmacologically induced LH surge [23]. The abundance of the sulfa-transporter SLC26A2 was higher after exposure to 41 °C in the current study and after acute hyperthermia in bovine cumulus cells [23]. Although a direct role in the COC is unknown, sulfonated proteoglycans are thought to be required for successful COC expansion [94]. While prolonged heat shock reduced cumulus expansion [95], effects of shorter durations of elevated temperature (positive or negative) have not been noted by our laboratory (Edwards, unpublished observation).

Since our study focused on early maturation, it is unsurprising that the majority of targeted transcripts were impacted in the first 6 h. Only three transcripts demonstrated a delayed impact (i.e., first affected during recovery from heat) from exposure to 41 °C in early maturation (LYN, YES1, and CAV1) with differences first noted at 10 hIVM. Our lab previously reported that the elevated temperature decreased CAV1 at 24 hIVM but not at 12 hIVM [14]. Differences may be due to the shorter length of exposure to 41 °C (i.e., 6 h compared to 12 h) or the presence of oocytes (i.e., COC versus cumulus only) in the current study. Nevertheless, both studies demonstrated a similar pattern of expression over time. Although CAV1 precipitates with FSHR [96], its delayed expression suggests that it is not crucial for FSHR signaling in early maturation. The drastic upregulation late in maturation appears to be quite unique and is intriguing, particularly as the role of CAV1 in late maturation or events occurring after ovulation is unknown. Of the 43 transcripts that had a significant temperature by time interaction, only one transcript remained affected by 18 h of recovery (MMP9).

5. Conclusions

Because higher estrus-associated temperatures (HEATs) persist for hours in cattle, direct effects on fertility-important components (i.e., the oocyte and surrounding cumulus cells) are unavoidable and likely functionally impactful. Building off a foundation of knowledge, novel findings described herein highlight both the direct and delayed effects of short bouts of a physiologically relevant elevated temperature (i.e., 2, 4, or 6 h) when applied during the beginnings of oocyte maturation (i.e., meiotic resumption through GVBD). Direct consequences on COCs were noted as early as 2 hIVM and included impacts on transcript abundance whose protein products are known to be involved in cell junctions, plasma membrane rafts, and cell-cycle regulation and other functions that may indirectly or directly impact meiotic resumption and progression. Novel findings documenting a heat-induced shift in targeted transcriptome provide additional support for the heat-shocked COC to be more advanced. Depending on the extent to which HEAT exposure in vivo may be shifting developmentally important processes, additional effort may be needed to investigate insemination timing under circumstances where body temperature elevations are more pronounced and persist for a longer time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.K., R.R.P., F.N.S. and J.L.E.; Data curation, J.L.K.; Formal analysis, J.L.K., J.E.B., R.R.P., K.H.L. and J.L.E.; Funding acquisition, J.L.E.; Investigation, J.L.K., J.E.B., R.R.P., K.H.L. and J.L.E.; Methodology, J.L.K., J.E.B., R.R.P., K.H.L. and J.L.E.; Project administration, J.L.E.; Resources, J.L.E.; Supervision, J.L.E.; Visualization, J.L.K. and J.L.E.; Writing—original draft, J.L.K.; Writing—review and editing, J.L.K., J.E.B., R.R.P., K.H.L., F.N.S. and J.L.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported in part by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant No. 2022-67015-36374 (Project Director: J. Lannett Edwards) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the state of Tennessee through University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, AgResearch and the Genomics Center for the Advancement of Agriculture, the Department of Animal Science, and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Multistate Project Accession No. 7003090; NE2227.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable—COCs abattoir-derived.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study may be available for viewing upon submission of a reasonable request from the co-corresponding author at jlk0066@auburn.edu.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are extended to James, Pam, and Kelsey Brantley for their generous contributions to our research efforts. We wish to thank Sujata Agarwal (UTIA Genomics Hub) for the use of the CLC Genomics Workbench, Taylor Seay and Matt Huff for technical assistance through their affiliation with the UTIA Genomics Center for Advancement of Agriculture and Joe May at the UT Genomics Core for assistance with RNA quality assessment. Appreciation is also extended to graduate students Megan Mills, Emma Horn, and Lisa Kirsten Senn for assistance with collection of COCs and undergraduate students Adella Lonas and Ella Pollock for assistance with electronic data verification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ARHGAP31 | Rho GTPase activating protein 31 |

| ARHGAP6 | Rho GTPase activating protein 6 |

| BANP | BTG3 associated nuclear protein |

| BDKRB1 | Bradykinin receptor B1 |

| CAV1 | Caveolin 1 |

| CCDC25 | Coiled-coil domain containing 25 |

| CCDC80 | Coiled-coil domain containing 80 |

| COC | Cumulus–oocyte complex |

| CPM | Counts per million |

| CTSB | Cathepsin B |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| ESR2 | Estrogen receptor 2 |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ETFA | Electron transfer flavoprotein subunit alpha |

| FDX1 | Ferredoxin 1 |

| FDXR | Ferredoxin reductase |

| FGR | FGR proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase |

| FSHR | Follicle stimulating hormone receptor |

| FYN | FYN proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase |

| GVBD | Germinal vesicle breakdown |

| h | Hour(s) |

| HEAT | Higher estrus-associated temperature |

| hIVM | Hours of in vitro maturation |

| HS | Heat shock |

| HSD3B7 | Hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3-beta- and steroid delta-isomerase 7 |

| HSP90AB1 | Heat shock protein 90 alpha family class B member 1 |

| HSP90B1 | Heat shock protein 90 beta family member 1 |

| HTATIP2 | HIV-1 Tat interactive protein 2 |

| IL6R | Interleukin 6 receptor |

| INHBB | Inhibin subunit beta B |

| LCK | LCK proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase |

| LH | Luetinizing hormone |

| LYN | LYN proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase |

| MAPK3 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 |

| MCM6 | Minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 |

| MDM2 | MDM2 proto-oncogene |

| MMP9 | Matrix metallopeptidase 9 |

| NR5A1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 5 group A member 1 |

| PAK2 | p21 (RAC1) activated kinase 2 |

| PEAK1 | Pseudopodium enriched atypical kinase 1 |

| PGRMC2 | Progesterone receptor membrane component 2 |

| PRDX2 | Peroxiredoxin 2 |

| PRKAA1 | Protein kinase AMP-activated catalytic subunit alpha 1 |

| RAI14 | Retinoic acid induced 14 |

| RBM3 | RNA binding motif protein 3 |

| SCN7A | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 7 |

| SF1 | Splicing factor 1 |

| SLC26A2 | Solute carrier family 26 member 2 |

| SNAP91 | Synaptosome associated protein 91 |

| SNX22 | Sorting nexin 22 |

| SRC | SRC proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase |

| TANC1 | Tetratricopeptide repeat, ankyrin repeat and coiled-coil containing 1 |

| TFRC | Transferrin receptor |

| TN | Thermoneutral |

| TNIK | TRAF2 and NCK interacting kinase |

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 |

| TTYH1 | Tweety family member 1 |

| YES1 | YES proto-oncogene 1, Src family tyrosine kinase |

References

- Mills, M.D.; Pollock, A.B.; Batey, I.E.; O’Neil, M.A.; Schrick, F.N.; Payton, R.R.; Moorey, S.E.; Fioravanti, P.; Hipsher, W.; Zoca, S.M.; et al. Magnitude and persistence of higher estrus-associated temperatures in beef heifers and suckled cows. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higaki, S.; Miura, R.; Suda, T.; Andersson, L.M.; Okada, H.; Zhang, Y.; Itoh, T.; Miwakeichi, F.; Yoshioka, K. Estrous detection by continuous measurements of vaginal temperature and conductivity with supervised machine learning in cattle. Theriogenology 2019, 123, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamahendran, R.; Robinson, J.; Desbottes, S.; Walton, J.S. Temporal relationships among estrus, body temperature, milk yield, progesterone and luteinizing hormone levels, and ovulation in dairy cows. Theriogenology 1989, 31, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamahendran, R.; Taylor, C. Follicular dynamics and temporal relationships among body temperature, oestrus, the surge of luteinizing hormone and ovulation in Holstein heifers treated with norgestomet. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1991, 92, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.O.; Edwards, J.L.; Di Croce, F.A.; Roper, D.; Rohrbach, N.R.; Saxton, A.M.; Schuenemann, G.M.; Prado, T.M.; Schrick, F.N. Ovulatory follicle dysfunction in lactating dairy cows after treatment with Folltropin-V at the onset of luteolysis. Theriogenology 2013, 79, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saumande, J.; Humblot, P. The variability in the interval between estrus and ovulation in cattle and its determinants. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2005, 85, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constable, P.D.; Hinchcliff, K.W.; Done, S.H.; Grünberg, W. Clinical Examination and Making a Diagnosis. In Veterinary Medicine, 11th ed.; Constable, P.D., Hinchcliff, K.W., Done, S.H., Grünberg, W., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, G.R. Body temperature and fertilization in the cow. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1962, 3, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liles, H.L.; Schneider, L.G.; Pohler, K.G.; Oliveira Filho, R.V.; Schrick, F.N.; Payton, R.R.; Rhinehart, J.D.; Thompson, K.W.; McLean, K.; Edwards, J.L. Positive relationship of rectal temperature at fixed timed artificial insemination on pregnancy outcomes in beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh Ali, H.; Kitahara, G.; Tamura, Y.; Kobayashi, I.; Hemmi, K.; Torisu, S.; Sameshima, H.; Horii, Y.; Zaabel, S.; Kamimura, S. Presence of a temperature gradient among genital tract portions and the thermal changes within these portions over the estrous cycle in beef cows. J. Reprod. Dev. 2013, 59, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hunter, R.H.; Bogh, I.B.; Einer-Jensen, N.; Muller, S.; Greve, T. Pre-ovulatory graafian follicles are cooler than neighbouring stroma in pig ovaries. Hum. Reprod. 2000, 15, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hooper, L.M.; Payton, R.R.; Rispoli, L.A.; Saxton, A.M.; Edwards, J.L. Impact of heat stress on germinal vesicle breakdown and lipolytic changes during in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes. J. Reprod. Dev. 2015, 61, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campen, K.A.; Abbott, C.R.; Rispoli, L.A.; Payton, R.R.; Saxton, A.M.; Edwards, J.L. Heat stress impairs gap junction communication and cumulus function of bovine oocytes. J. Reprod. Dev. 2018, 64, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rispoli, L.A.; Payton, R.R.; Gondro, C.; Saxton, A.M.; Nagle, K.A.; Jenkins, B.W.; Schrick, F.N.; Edwards, J.L. Heat stress effects on the cumulus cells surrounding the bovine oocyte during maturation: Altered matrix metallopeptidase 9 and progesterone production. Reproduction 2013, 146, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowinski, J.R.; Rispoli, L.A.; Payton, R.R.; Schneider, L.G.; Schrick, F.N.; McLean, K.J.; Edwards, J.L. Impact of an acute heat shock during in vitro maturation on interleukin 6 and its associated receptor component transcripts in bovine cumulus-oocyte complexes. Anim. Reprod. 2020, 17, e20200221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, L.C.; Barreta, M.H.; Gasperin, B.; Bohrer, R.; Santos, J.T.; Buratini, J., Jr.; Oliveira, J.F.; Goncalves, P.B. Angiotensin II, progesterone, and prostaglandins are sequential steps in the pathway to bovine oocyte nuclear maturation. Theriogenology 2012, 77, 1779–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sirotkin, A.V. Involvement of steroid hormones in bovine oocytes maturation in vitro. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1992, 41, 855–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, L.A.; Edwards, J.L.; Pohler, K.G.; Russell, S.; Somiari, R.I.; Payton, R.R.; Schrick, F.N. Heat-induced hyperthermia impacts the follicular fluid proteome of the periovulatory follicle in lactating dairy cows. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0227095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Espey, L.; Hosoi, Y.; Adachi, T.; Atlas, S.J.; Ghodgaonkar, R.B.; Dubin, N.H.; Wallach, E.E. The effects of bradykinin on ovulation and prostaglandin production by the perfused rabbit ovary. Endocrinology 1988, 122, 2540–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellberg, P.; Larson, L.; Olofsson, J.; Hedin, L.; Brännström, M. Stimulatory effects of bradykinin on the ovulatory process in the in vitro-perfused rat ovary. Biol. Reprod. 1991, 44, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; de Matos, D.G.; Fan, H.Y.; Shimada, M.; Palmer, S.; Richards, J.S. Interleukin-6: An autocrine regulator of the mouse cumulus cell-oocyte complex expansion process. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3360–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromfield, J.J.; Sheldon, I.M. Lipopolysaccharide initiates inflammation in bovine granulosa cells via the TLR4 pathway and perturbs oocyte meiotic progression in vitro. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 5029–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klabnik, J.L.; Christenson, L.K.; Gunewardena, S.S.; Pohler, K.G.; Rispoli, L.A.; Payton, R.R.; Moorey, S.E.; Schrick, F.N.; Edwards, J.L. Heat-induced increases in body temperature in lactating dairy cows: Impact on the cumulus and granulosa cell transcriptome of the periovulatory follicle. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.L.; Payton, R.R.; Godkin, J.D.; Saxton, A.M.; Schrick, F.N.; Edwards, J.L. Retinol improves development of bovine oocytes compromised by heat stress during maturation. J. Dairy. Sci. 2004, 87, 2449–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rispoli, L.A.; Lawrence, J.L.; Payton, R.R.; Saxton, A.M.; Schrock, G.E.; Schrick, F.N.; Middlebrooks, B.W.; Dunlap, J.R.; Parrish, J.J.; Edwards, J.L. Disparate consequences of heat stress exposure during meiotic maturation: Embryo development after chemical activation vs fertilization of bovine oocytes. Reproduction 2011, 142, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.L.; Saxton, A.M.; Lawrence, J.L.; Payton, R.R.; Dunlap, J.R. Exposure to a physiologically relevant elevated temperature hastens in vitro maturation in bovine oocytes. J. Dairy. Sci. 2005, 88, 4326–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payton, R.R.; Rispoli, L.A.; Nagle, K.A.; Gondro, C.; Saxton, A.M.; Voy, B.H.; Edwards, J.L. Mitochondrial-related consequences of heat stress exposure during bovine oocyte maturation persist in early embryo development. J. Reprod. Dev. 2018, 64, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, F.M.; Huo, N.; Gu, Y.Q.; Luo, M.-C.; Ma, Y.; Hane, D.; Lazo, G.R.; Dvorak, J.; Anderson, O.D. BatchPrimer3: A high throughput web application for PCR and sequencing primer design. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelic, R.; Winter, H.; Powers, J.B.; Das, S.; Lamour, K.; Campagna, S.R.; Voy, B.H. Genes controlling polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis are developmentally regulated in broiler chicks. Br. Poult. Sci. 2020, 61, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, J.; Lamour, K.; Frost, K.; Dwyer, J.; Huseth, A.; Groves, R.L. Targeted RNA sequencing reveals differential patterns of transcript expression in geographically discrete, insecticide resistant populations of Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 3436–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Dumont, T.; Pope, B.J.; Hammet, F.; Southey, M.C.; Park, D.J. A high-plex PCR approach for massively parallel sequencing. BioTechniques 2013, 55, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Sturm, M.; Schroeder, C.; Bauer, P. SeqPurge: Highly-sensitive adapter trimming for paired-end NGS data. BMC Bioinform. 2016, 17, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lun, A.T.; Smyth, G.K. From reads to genes to pathways: Differential expression analysis of RNA-Seq experiments using Rsubread and the edgeR quasi-likelihood pipeline. F1000Research 2016, 5, 1438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Smyth, G.K. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4288–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2009, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risso, D.; Ngai, J.; Speed, T.P.; Dudoit, S. Normalization of RNA-seq data using factor analysis of control genes or samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Law, C.W.; Ah-Cann, C.; Asselin-Labat, M.-L.; Blewitt, M.E.; Ritchie, M.E. Glimma: Interactive graphics for gene expression analysis. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2050–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.C.; Lane, D.; Scott, D.; Hebl, M.; Guerra, R.; Osherson, D.; Zimmer, H. An Introduction to Psychological Statistics; University of Missouri: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, U. A note on the power of Fisher’s least significant difference procedure. Pharm. Stat. 2006, 5, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbon, S.; Hirao, Y.; Miyano, T. Interactions between the oocyte and surrounding somatic cells in follicular development: Lessons from in vitro culture. J. Reprod. Dev. 2003, 49, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidder, G.M.; Vanderhyden, B.C. Bidirectional communication between oocytes and follicle cells: Ensuring oocyte developmental competence. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 88, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, S.; Wozniak, P.J.; Yang, X.; Godke, R.A. Cumulus cell function during bovine oocyte maturation, fertilization, and embryo development in vitro. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1995, 40, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geshi, M.; Takenouchi, N.; Yamauchi, N.; Nagai, T. Effects of sodium pyruvate in nonserum maturation medium on maturation, fertilization, and subsequent development of bovine oocytes with or without cumulus cells. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 63, 1730–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyttel, P.; Xu, K.P.; Smith, S.; Greve, T. Ultrastructure of in-vitro oocyte maturation in cattle. Reproduction 1986, 78, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regassa, A.; Rings, F.; Hoelker, M.; Cinar, U.; Tholen, E.; Looft, C.; Schellander, K.; Tesfaye, D. Transcriptome dynamics and molecular cross-talk between bovine oocyte and its companion cumulus cells. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfelder, M.; Schams, D.; Einspanier, R. Steroidogenesis during in vitro maturation of bovine cumulus oocyte complexes and possible effects of tri-butyltin on granulosa cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003, 84, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosca, L.; Uzbekova, S.; Chabrolle, C.; Dupont, J. Possible role of 5′AMP-activated protein kinase in the metformin-mediated arrest of bovine oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage during in vitro maturation. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 77, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyttel, P.; Fair, T.; Callesen, H.; Greve, T. Oocyte growth, capacitation and final maturation in cattle. Theriogenology 1997, 47, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirard, M.-A. Factors affecting oocyte and embryo transcriptomes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krischek, C.; Meinecke, B. In vitro maturation of bovine oocytes requires polyadenylation of mRNAs coding proteins for chromatin condensation, spindle assembly, MPF and MAP kinase activation. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2002, 73, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez, F.; Camargo, Á.; Reyes, A.L.; Márquez, A.; Paula-Lopes, F.; Viñoles, C. Time-dependent effects of heat shock on the zona pellucida ultrastructure and in vitro developmental competence of bovine oocytes. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 19, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, J.C.; Parks, J.E.; Yang, X. Thermotolerance of IVM-derived bovine oocytes and embryos after short-term heat shock. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1999, 53, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, P.L.; Vogel, H.; Soriano, P. Combined deficiencies of Src, Fyn, and Yes tyrosine kinases in mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, M.; Maro, B.; Shalgi, R. The involvement of Fyn kinase in resumption of the first meiotic division in mouse oocytes. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 1577–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zheng, K.G.; Meng, X.Q.; Yang, Y.; Yu, Y.S.; Liu, D.C.; Li, Y.L. Requirements of Src family kinase during meiotic maturation in mouse oocyte. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2007, 74, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheilova, K.; Petr, J.; Zalmanova, T.; Kucerova-Chrpova, V.; Rehak, D. Src family kinases are involved in the meiotic maturation of porcine oocytes. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2015, 27, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonyaratanakornkit, V.; Scott, M.P.; Ribon, V.; Sherman, L.; Anderson, S.M.; Maller, J.L.; Miller, W.T.; Edwards, D.P. Progesterone receptor contains a proline-rich motif that directly interacts with SH3 domains and activates c-Src family tyrosine kinases. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, H.; Har-Paz, E.; Gindi, N.; Levi, M.; Miller, I.; Nevo, N.; Galiani, D.; Dekel, N.; Shalgi, R. Regulation of GVBD in mouse oocytes by miR-125a-3p and Fyn kinase through modulation of actin filaments. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, M.R.; Rispoli, L.A.; Payton, R.R.; Saxton, A.M.; Edwards, J.L. Developmental consequences of supplementing with matrix metallopeptidase-9 during in vitro maturation of heat-stressed bovine oocytes. J. Reprod. Dev. 2016, 62, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.L. Steroidogenesis: Unanswered questions. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 771–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, W.B. The role of the hsp90-based chaperone system in signal transduction by nuclear receptors and receptors signaling via MAP kinase. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997, 37, 297–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, D.M.; Ko, C.; Jo, M.; Brannstrom, M.; Curry, T.E., Jr. Ovulation: Parallels with inflammatory processes. Endocr. Rev. 2019, 40, 369–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, C.B.; Meier, S.; Murray, L.A.; Burke, C.R.; Pitman, J.L. The microenvironment of ovarian follicles in fertile dairy cows is associated with high oocyte quality. Theriogenology 2022, 177, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imada, K.; Ito, A.; Sato, T.; Namiki, M.; Nagase, H.; Mori, Y. Hormonal regulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9/gelatinase B gene expression in rabbit uterine cervical fibroblasts. Biol. Reprod. 1997, 56, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimonovitz, S.; Hurwitz, A.; Hochner-Celnikier, D.; Dushnik, M.; Anteby, E.; Yagel, S. Expression of gelatinase B by trophoblast cells: Down-regulation by progesterone. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 178, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-M.; Lee, T.-K.; Song, H.-B.; Kim, C.-H. The expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in human follicular fluid is associated with in vitro fertilisation pregnancy. BJOG 2005, 112, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, E.E.; Mazurkiewicz-Muñoz, A.M.; Argetsinger, L.S.; Maures, T.J.; Huynh, H.T.; Carter-Su, C. Identification of steroid-sensitive gene-1/Ccdc80 as a JAK2-binding protein. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcantonio, D.; Chalifour, L.E.; Alaoui-Jamali, M.A.; Alpert, L.; Huynh, H.T. Cloning and characterization of a novel gene that is regulated by estrogen and is associated with mammary gland carcinogenesis. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 2409–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortune, J.E.; Hansel, W. Concentrations of steroids and gonadotropins in follicular fluid from normal heifers and heifers primed for superovulation. Biol. Reprod. 1985, 32, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beker, A.R.C.L.; Colenbrander, B.; Bevers, M.M. Effect of 17β-estradiol on the in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes. Theriogenology 2002, 58, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, M.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, I.; Gonzalez-Robayna, I.; Richards, J.S. Paracrine and autocrine regulation of epidermal growth factor-like factors in cumulus oocyte complexes and granulosa cells: Key roles for prostaglandin synthase 2 and progesterone receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.-Q.; Nyegaard, M.; Overgaard, M.T.; Qiao, J.; Giudice, L.C. Participation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in luteinizing hormone-induced differential regulation of steroidogenesis and steroidogenic gene expression in mural and cumulus granulosa cells of mouse preovulatory follicles. Biol. Reprod. 2006, 75, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, R.P.; Freudzon, M.; Mehlmann, L.M.; Cowan, A.E.; Simon, A.M.; Paul, D.L.; Lampe, P.D.; Jaffe, L.A. Luteinizing hormone causes MAP kinase-dependent phosphorylation and closure of connexin 43 gap junctions in mouse ovarian follicles: One of two paths to meiotic resumption. Development 2008, 135, 3229–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiquet, N.; Sasseville, M.; Laforest, M.; Guillemette, C.; Gilchrist, R.B.; Richard, F.J. Activation of 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase blocks cumulus cell expansion through inhibition of protein synthesis during in vitro maturation in swine. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 91, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Jung, J.I.; Park, K.Y.; Kim, S.A.; Kim, J. Synergistic inhibition effect of TNIK inhibitor KY-05009 and receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor dovitinib on IL-6-induced proliferation and Wnt signaling pathway in human multiple myeloma cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 41091–41101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, T.; Li, V.S.W.; Ng, S.S.; Taouatas, N.; Vries, R.G.J.; Mohammed, S.; Heck, A.J.; Clevers, H. The kinase TNIK is an essential activator of Wnt target genes. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 3329–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shitashige, M.; Naishiro, Y.; Idogawa, M.; Honda, K.; Ono, M.; Hirohashi, S.; Yamada, T. Involvement of splicing factor-1 in beta-catenin/T-cell factor-4-mediated gene transactivation and pre-mRNA splicing. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1039–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S.; Idogawa, M.; Honda, K.; Fujii, G.; Kawashima, H.; Takekuma, K.; Hoshika, A.; Hirohashi, S.; Yamada, T. Beta-catenin interacts with the FUS proto-oncogene product and regulates pre-mRNA splicing. Gastroenterology 2005, 129, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xin, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. Estrogen receptors in granulosa cells govern meiotic resumption of pre-ovulatory oocytes in mammals. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderfiyden, B.C.; Telfer, E.E.; Eppig, J.J. Mouse oocytes promote proliferation of granulosa cells from preantral and antral follicles in vitro. Biol. Reprod. 1992, 46, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraguchi, H.; Hirota, Y.; Saito-Fujita, T.; Tanaka, T.; Shimizu-Hirota, R.; Harada, M.; Akaeda, S.; Hiraoka, T.; Matsuo, M.; Matsumoto, L.; et al. Mdm2-p53-SF1 pathway in ovarian granulosa cells directs ovulation and fertilization by conditioning oocyte quality. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 2610–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Ahmed, F.; Bhat, M.K.; Chhipa, R.; Galande, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. Direct interaction with and activation of p53 by SMAR1 retards cell-cycle progression at G2/M phase and delays tumor growth in mice. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 103, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cau, J.; Faure, S.; Vigneron, S.; Labbé, J.C.; Delsert, C.; Morin, N. Regulation of Xenopus p21-activated kinase (X-PAK2) by Cdc42 and maturation-promoting factor controls Xenopus oocyte maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirotkin, A.V. Effect of two types of stress (heat shock/high temperature and malnutrition/serum deprivation) on porcine ovarian cell functions and their response to hormones. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 2125–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustelo, X.R.; Sauzeau, V.; Berenjeno, I.M. GTP-binding proteins of the Rho/Rac family: Regulation, effectors and functions in vivo. BioEssays 2007, 29, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochman, M.L.; Schwacha, A. The Mcm complex: Unwinding the mechanism of a replicative helicase. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 652–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, M.D.; Caveney, A.N.; Smith, L.C.; Watson, A.J. Responsiveness of bovine cumulus-oocyte-complexes (COC) to porcine and recombinant human FSH, and the effect of COC quality on gonadotropin receptor and Cx43 marker gene mRNAs during maturation in vitro. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2003, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragovic, R.A.; Ritter, L.J.; Schulz, S.J.; Amato, F.; Thompson, J.G.; Armstrong, D.T.; Gilchrist, R.B. Oocyte-secreted factor activation of SMAD 2/3 signaling enables initiation of mouse cumulus cell expansion. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 76, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, C.L.V.; Mamo, S.; Fair, T.; Lonergan, P. Gene expression in bovine oocytes and cumulus cells after meiotic inhibition with the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor butyrolactone I. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.-J.; Kim, J.-S.; Yun, P.-R.; Seo, Y.-W.; Lee, T.-H.; Park, J.-I.; Chun, S.-Y. Involvement of peroxiredoxin 2 in cumulus expansion and oocyte maturation in mice. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2020, 32, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaioni, A.; Salustri, A.; Yanagishita, M.; Hascall, V.C. Proteoglycans and proteins in the extracellular matrix of mouse cumulus cell–oocyte complexes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996, 325, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, R.; Ball, G.; Leibfried, M.; Ax, R.; First, N. In vitro maturation and fertilization of bovine oocytes are temperature-dependent processes. Biol. Reprod. 1983, 29, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, K.A.; Dias, J.A.; Cohen, B.D. Investigation of human follicle stimulating hormone residency in membrane microdomains. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 880.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).