Simple Summary

Feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) is a chronic disorder of the lower urinary tract in cats. At present, the disease is mainly excluded by evaluating the results of blood, urine, and imaging examinations of diseased animals. There is still a lack of clear and objective indicators for the diagnosis of FIC in clinical practice. In this study, the correlation between NLR and FIC was analyzed by collecting the complete blood count data of FIC cats and healthy cats. The results of the inter-group difference comparison showed that the NLR levels in the normal group were distinctly lower than that in the FIC group (p < 0.001). Spearman correlation analysis showed that there was a significant correlation between NLR and FIC (r = −0.8439, p < 0.0001). ROC analysis showed that NLR had high diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing healthy cats from FIC cats (AUC = 0.9872). Therefore, the NLR parameter holds the potential to serve as a non-invasive biomarker of FIC.

Abstract

Feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) is a common chronic cystitis disease in cats, accounting for 55–65% of feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD). The common clinical symptoms of FIC include pollakiuria, periuria, hematuria, and dysuria. At present, the disease is mainly excluded by evaluating the results of blood, urine, and imaging examinations of diseased animals. There is still a lack of clear and objective indicators for the diagnosis of FIC in clinical practice. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) can be used as an indicator to measure immune inflammatory response and neuroendocrine pressure. It is an economical, efficient, and simple calculation method. In this study, the correlation between NLR and FIC was analyzed by collecting the complete blood count data of FIC cats and healthy cats. The results of inter-group difference comparison showed that the LYMPH levels in the normal group were significantly higher than that in the FIC group (p < 0.001), and the NEUT levels and NLR levels were distinctly lower than those in the FIC group (p < 0.001). Spearman correlation analysis showed that there was a significant correlation between NLR and FIC (r = −0.8439, p < 0.0001). ROC analysis showed that NLR had high diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing healthy cats from FIC cats (AUC = 0.9872). In general, this study preliminarily confirmed that there was a significant correlation between NLR elevation and FIC, emphasizing the prospective utility of NLR as a promising biomarker for diagnosis in FIC. Because of the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria for FIC, NLR may provide important help in the diagnosis process.

1. Introduction

Feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) is a chronic cystitis disease commonly seen in cats, accounting for approximately 55% to 65% of feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) cases [1]. The exact cause of this condition is still unclear. Affected animals typically exhibit chronic irritative urinary symptoms, without evidence of bacteriuria and pyuria [2]. Research indicates FIC development is influenced by multiple factors, including genetics, obesity, diet, stress, and hormonal changes following neutering [3]. Additional research indicates that the primary pathophysiological manifestations of FIC result from central nervous system stimulation, chronic stress-induced adrenal insufficiency, or alterations in urinary bladder permeability [4,5]. Reports suggest that compared to other urinary tract diseases, FIC represents a more complex condition involving multiple organs and systems [6,7,8].

Common clinical symptoms of FIC include pollakiuria, periuria, hematuria and dysuria. Currently, diagnosis is primarily made through exclusionary methods: evaluating clinical signs and medical history, conducting a comprehensive physical examination, blood analysis, urinalysis, urine culture, and urinary tract imaging. FIC is typically confirmed after ruling out urinary tract infections, urolithiasis, anatomical abnormalities, behavioral issues, and neoplasms [7]. Unfortunately, there is still a lack of uniform diagnostic criteria for FIC.

Previous investigations indicate that urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) may be a potential biomarker for FIC [4]. The urothelium, which is a part of the bladder wall contains three layers: the basal, intermediate, and superficial apical layer. Superficial urothelial cells play a pivotal role in maintaining the bladder’s protective barrier, which primarily relies on a glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer covering the luminal surface of the urothelium [9]. Any factor that disrupts the structural or functional integrity of GAGs, or directly damages the urothelium, can compromise the barrier’s function [10]. Previous studies have shown that cats with feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) exhibit reduced urinary concentrations of total GAGs [11] and elevated urinary protein-to-creatinine (UPC) ratios compared with healthy cats [4]. N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) has been implicated in the degradation of circulating GAGs, and proteinuria is recognized as one of the characteristic features of FIC [12,13]. Accordingly, alterations in urinary NAG concentration may influence the GAG layer lining the bladder and reflect underlying pathological changes in affected cats [4].

In 2001, Zahorec and colleagues proposed a novel indicator for assessing immune-inflammatory responses and neuroendocrine stress, later termed the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [14]. This parameter is derived by dividing the neutrophil count (NEUT#) by the lymphocyte count (LYMPH#) and can be obtained through a simple and readily accessible complete blood count (CBC). Consequently, it represents an economical, efficient, and straightforward computational method. Studies have demonstrated that the NLR parameter serves as an inflammatory marker associated with chronic diseases [14], and it is considered a simple indicator for assessing an individual’s inflammatory status [15].

Neutrophilia and lymphopenia are recognized as fundamental indicators of innate immune activation in the context of systemic inflammation [16]. Retrospective findings have identified a close link between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and inflammatory pathophysiological processes in cats [17]. In felines affected by chronic kidney disease (CKD), a progressive condition marked by sustained inflammatory activity, NLR values tend to rise substantially in advanced stages when compared with both early CKD and healthy cohorts [18]. Investigations into systemic inflammatory disorders have demonstrated that NLR values are notably elevated in cats suffering from systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis relative to clinically normal counterparts. Elevated NLR has also been independently associated with higher mortality rates in these populations [19]. Furthermore, retrospective evidence indicates that cats experiencing blunt trauma often exhibit increased NLR, suggesting its potential utility as a marker for assessing injury severity [20]. Within the scope of feline neoplastic conditions, markedly greater preoperative NLR values have been observed in individuals diagnosed with infiltrative injection-site sarcomas, fibrosarcomas, and those presenting with local tumor recurrence following surgical removal [21]. In addition, heightened NLR levels have been correlated with a significantly increased likelihood of tumor-associated death [22].

Previous studies indicate that blood cortisol levels and neutrophil counts increase under stress conditions [23]. Elevated cortisol may result from physical and mental stresses and sympathetic nervous system activity [24], while increased neutrophils may correlate with higher blood cortisol levels [25]. Cortisol influences multiple cellular and physiological functions to maintain organismal homeostasis. During physical load, cortisol primarily functions as an effector of the general stress response. Concurrently, it suppresses inflammation and certain immune reactions while mobilizing neutrophils [23]. Therefore, an elevated NLR may be stress related. Furthermore, human medical studies indicate that NLR accurately predicts conditions such as sepsis and infectious diseases [26], as well as cancer [27]. Simultaneously, this indicator holds potential as a non-invasive diagnostic marker and symptom indicator for human interstitial cystitis (IC) [28]. FIC is a chronic cystitis disease similar to IC [29]. We speculated that the NLR parameter may also hold potential in the early prediction of FIC. Therefore, this study collected complete blood count data from cats with FIC and healthy cats to statistically analyze NLR, investigate the correlation between NLR and FIC, and preliminarily explore the feasibility of the NLR parameter as a promising non-invasive biomarker of FIC. This aims to provide data support for the correlation between NLR and FIC in veterinary clinical practice and evaluate the potential of NLR as a non-invasive indicator of potential FIC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Candidates

Data were collected from a randomly selected cohort of 100 cats treated at the China Agricultural University Veterinary Teaching Hospital and Zhe Jiang Zhangxu Veterinary Hospital from 2022 to 2025.

2.2. Methods

The basic information (including breed, age, gender, and body weight) and medical history of each cat were collected, and their physical examination, complete blood count, and blood biochemistry results were recorded. We also collected urinalysis, urine culture, X-ray examination, and ultrasound examination results from the cats with FIC. An outline of the case definitions and the criteria applied for their selection [2,4,29] is presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Case definitions.

Table 2.

Selection criteria.

In addition, all blood samples were collected in a quiet, cat-specific sampling room, equipped with pheromones to enhance emotional comfort. Blood was drawn using standardized techniques from either the cephalic or saphenous vein of each animal and promptly sent for analysis.

In all included cats, hematological analyses were performed with the ProCyte Dx Hematology Analyzer (IDEXX, Westbrook, ME, USA). Blood smear examinations were also performed to validate the results obtained from the instrument analysis. Moreover, urine samples were cultured on blood agar and MacConkey agar to assess bacterial growth. Routine urinalysis was conducted to measure key physicochemical and microscopic parameters, including color, specific gravity, occult blood, protein, potential of hydrogen (pH), epithelial cells, crystals, glucose, ketones, urobilinogen, and other parameters.

All samples were divided into FIC and normal groups, with 50 samples in each group. The age, body weight, LYMPH levels, and NEUT levels were counted, and NLR was calculated.

Continuous variables following a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas non-normally distributed variables were presented as median (IQR). The Shapiro–Wilk test (S-W test) was used to detect the normality of the data. The Mann–Whitney U test (U test) and Chi-square test were used to detect the differences between groups. Spearman correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between NLR and FIC. The ROC analysis was used to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of NLR in distinguishing FIC cats from healthy cats. SPSS27 software was used for analysis.

3. Results

Breeds of cats with FIC includes domestic shorthair or longhair (n = 14), British Shorthair (n = 12), American Shorthair (n = 10), Ragdoll (n = 7), Garfield (n = 2), Exotic Shorthair (n = 2), Scottish Fold (n = 2), and Bengal (n = 1). The breed of normal cats was shorthair or longhair (n = 20), British Shorthair (n = 10), American Shorthair (n = 5), Ragdoll (n = 7), Garfield (n = 2), Devon Rex (n = 3), Maine Coon (n = 2), and Siamese (n = 1). No significant breed predispositions were found (p = 0.127).

Of the cats with FIC, 49 (98%) were males and 1 (2%) was female. Corresponding values for the normal group were 18 (36%) and 32 (64%), demonstrating a significant sex-associated predisposition (p < 0.001).

The LYMPH levels were significantly higher in the normal group than the FIC group (p < 0.001). On the contrary, the NEUT levels and NLR levels were distinctly lower than those in the FIC group (p < 0.001). At the same time, the body weight of the FIC group [5.00 (1.30) vs. 3.40 (1.40)] was distinctly higher. No significant differences were found in age (p = 0.053) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics for each group.

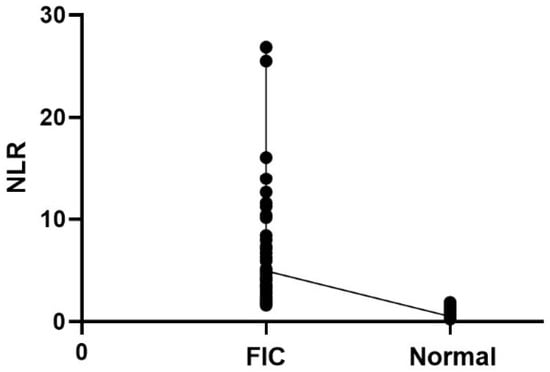

We also performed Spearman correlation analysis to assess the correlation between NLR and FIC (Table 4). The results showed that there was a significant correlation between NLR and FIC (r = −0.8439, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients between FIC with NLR.

Figure 1.

Correlation scatterplot of NLR with FIC.

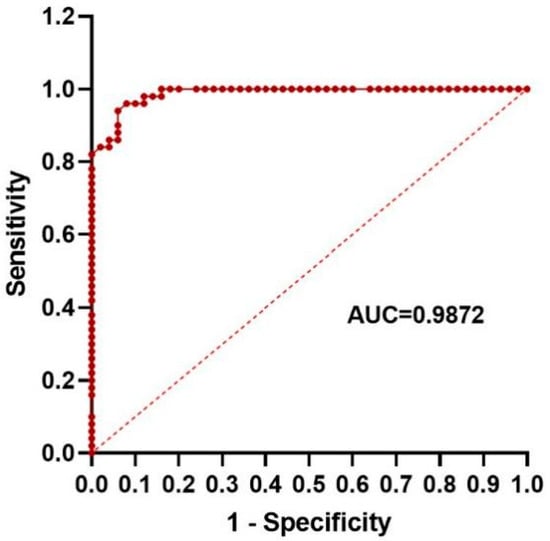

We also used ROC analysis to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of NLR in distinguishing FIC cats from healthy cats (Table S1). The results showed that when distinguishing FIC cats from healthy cats, the AUC value of NLR was 0.9872 (Figure 2), and the diagnostic accuracy was high. The maximum Youden index was 0.88, and the corresponding cutoff value was 1.785 and 1.795 (Table S1). As an early diagnostic indicator, 1.795 with higher sensitivity can be selected as the diagnostic cutoff value. This further suggests that the NLR parameter has a good potential to become a biomarker for diagnosis of FIC.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of NLR.

4. Discussion

This study showed that compared with healthy cats, FIC cats showed a significant increase in NLR and body weight. And there is a significant sex-associated predisposition in FIC. Through Spearman analysis, we determined that NLR was significantly correlated with FIC. Through ROC analysis, we determined that NLR has a good diagnostic utility in distinguishing FIC cats from healthy cats. These findings suggest that an elevated NLR holds a great potential to be a non-invasive biomarker of possible FIC.

Neutrophils play a crucial role in innate immune responses, performing fundamental functions such as phagocytosis and releasing various cytokines. They also release reactive oxygen species and a series of peptides that aid in forming extracellular traps, but these can adversely affect the bladder [30]. Inflammatory responses can cause neutrophilia, and tumor necrosis factor triggers lymphocyte apoptosis during the early stages of inflammation [31]. Numerous studies indicate that stress may contribute to FIC development. Short- or long-term exposure to abnormal external events and unpredictable stressors can induce tension and fear in cats, leading to FIC [8,32,33]. Concurrently, lymphopenia with neutrophilia is a symbol of stress [24]. Therefore, stressed animals exhibiting reduced neutrophil percentages and increased lymphocyte percentages [34]. Consequently, NLR serves as an inexpensive, simple, rapid-response, and readily accessible indicator of stress and inflammation. With high sensitivity and low specificity, it effectively captures the complex interplay between stress and inflammation, reflecting the equilibrium between innate and adaptive immune responses [35]. The increase in NLR values is directly associated with diseases characterized by severe inflammation, stress, injury, trauma, or cancer. Our findings followed the same trend as previous studies, which reported that there is a significant association between FIC incidence and overweight status [8,32,36]. This phenomenon may be linked to the reduced activity commonly observed in overweight cats. Similarly, cats with cystitis often exhibit decreased mobility [37]. Such inactivity may be indicative of stress, as cats subjected to prolonged stress frequently show a reduction in exploratory and playful behaviors, along with an increased tendency to hide [38].

Overall, compared with currently utilized biomarkers, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) represents a cost-effective, easily accessible, and readily calculable parameter, making its incorporation into clinical practice both practical and promising. The findings of this study indicate that NLR has the potential to serve as a non-invasive biomarker for feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC).

Despite these encouraging results, several limitations should be acknowledged. Although an association between FIC and elevated NLR was observed, a causal relationship cannot be firmly established. Future investigations employing prospective designs and incorporating serial NLR measurements may provide more definitive evidence regarding the diagnostic utility of NLR in FIC. Additionally, this study did not include cats diagnosed with urinary tract infections (UTIs); therefore, the ability of NLR to differentiate between FIC and UTI remains undetermined.

This study offers several notable strengths. To our knowledge, it represents the first investigation exploring the relationship between NLR and FIC, and the use of validated and widely accepted analytical methods in veterinary research enhances the robustness and reliability of the results.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study identified an association between NLR elevation and FIC, emphasizing the potential of NLR as a biomarker for FIC. Given the current lack of definitive objective indicators for diagnosing FIC in veterinary practice, NLR may offer significant assistance in the diagnostic process.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ani15223307/s1, Table S1: The analysis of ROC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.; data collection, J.Y., X.Z., W.Z., Y.Z., and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y. and X.Z.; writing— review and editing, H.S., L.Z., and M.Q.; supervision, H.S. and X.Z.; funding acquisition, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by The Talent Fund of China Agricultural University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, grant number 2223001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The work described in this manuscript involved the use of non-experimental (owned) animals. Established internationally recognized high standards (‘best practice’) of veterinary clinical care for the individual patient were always followed. No cadavers were used in this study. Ethical approval from a committee was therefore not specifically required for publication in Animals journal.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the owner of the animal involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sparkes, A. Understanding feline idiopathic cystitis. Vet. Rec. 2018, 182, 486–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caudron, M.; Laroche, P.; Bazin, I.; Desmarchelier, M. Association between behavioral factors and recurrence rate in cats with feline “idiopathic” cystitis. J. Vet. Behav. 2025, 78, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morar, D.; Ciulan, V.; Simiz, F.; Petruse, C.; Ciupercă, M.A.; Moț, T. Clinical and epidemiological study in cats with idiopathic cystitis. Lucr. Științifice 2015, 48, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Panboon, I.; Asawakarn, S.; Pusoonthornthum, R. Urine protein, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase index in cats with idiopathic cystitis vs healthy control cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2017, 19, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffington, C.A.; Chew, D.J. Management of non-obstructive idiopathic/interstitial cystitis in cats. In BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Nephrology and Urology, 2nd ed.; Elliott, J., Grauer, G.F., Eds.; Replika Press: Haryana, India, 2007; pp. 264–281. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD): An overview. Vet. Nurs. J. 2009, 24, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.D.; Towell, T.L. Feline idiopathic cystitis. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2015, 45, 783–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.S.; Sævik, B.K.; Finstad, Ø.W.; Grøntvedt, E.T.; Vatne, T.; Eggertsdóttir, A.V. Risk factors for idiopathic cystitis in Norwegian cats: A matched case–control study. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, P.J.; VanGordon, S.B.; Seavey, J.; Sofinowski, T.M.; Ramadan, M.; Abdullah, S.; Buffington, C.T.; Hurst, R.E. Abnormalities in expression of structural, barrier and differentiation related proteins, and chondroitin sulfate in feline and human interstitial cystitis. J. Urol. 2015, 194, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, J.M.; Osborne, C.A.; Lulich, J.P. Changing paradigms of feline idiopathic cystitis. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 39, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchaphanpong, J.; Asawakarn, T.; Pusoonthornthum, R. Effects of oral administration of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine on plasma and urine concentrations of glycosaminoglycans in cats with idiopathic cystitis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2011, 72, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komosińska-Vassev, K.; Olczyk, K.; Koźma, E.M.; Olczyk, P.; Wisowski, G.; Winsz-Szczotka, K. Alterations of glycosaminoglycan metabolism in the development of diabetic complications in relation to metabolic control. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2005, 43, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosomworth, M.P.; Aparicio, S.R.; Hay, A.W. Urine N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase: A marker of tubular damage? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1999, 14, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahorec, R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts—Rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl. Lekárske Listy 2001, 102, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Imtiaz, F.; Shafique, K.; Mirza, S.S.; Ayoob, Z.; Vart, P.; Rao, S. Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio as a measure of systemic inflammation in prevalent chronic diseases in Asian population. Int. Arch. Med. 2012, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, E.A.; Pizarro Del Valle, C.; Waugh, E.M.; French, A.; Ridyard, A.E. Retrospective investigation of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in dogs with pneumonia: 49 cases (2011–2016). J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2021, 31, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, G.; Pennisi, M.G.; Maria, F.P.; Archer, J.; Masucci, M. A retrospective comparative evaluation of selected blood cell ratios, acute phase proteins, and leukocyte changes suggestive of inflammation in cats. Animals 2023, 13, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žel, M.K.; Alenka, N.S.; Tozon, N.; Pavlin, D. Hemogram-derived inflammatory markers in cats with chronic kidney disease. Animals 2024, 14, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, E.; Pierini, A.; Lippi, I.; Lubas, G.; Marchetti, V. Leukocytes ratios in feline systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis: A retrospective analysis of 209 cases. Animals 2021, 11, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doulidis, P.G.; Vali, Y.; Frizzo Ramos, C.; Guija-de-Arespacochaga, A. Retrospective evaluation of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in cats with blunt trauma (2018–2021): 177 cases. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2024, 34, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, L.E.; Martano, M.; Ferrari, R.; Boracchi, P.; Giordano, A.; Grieco, V.; Buracco, P.; Iussich, S.; Giudice, C.; Miniscalco, B.; et al. Evaluation of leukocyte counts and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as predictors of local recurrence of feline injection site sarcoma after curative-intent surgery. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2020, 18, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, G.N.; Lobo, L.; Queiroga, F.; Martins, J.; Prada, J.; Pires, I.; Henriques, J. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic marker for feline mammary carcinomas. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2021, 19, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozaki, S.; Tanaka, M.; Mizuno, K.; Ataka, S.; Mizuma, H.; Tahara, T.; Sugino, T.; Shirai, T.; Eguchi, A.; Okuyama, K.; et al. Mental and physical fatigue-related biochemical alterations. Nutrition 2009, 25, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Deguchi, M.; Miyazaki, Y. The effects of exercise in forest and urban environments on sympathetic nervous activity of normal young adults. J. Int. Med. Res. 2006, 34, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, M.; Pyne, D.B.; Callister, R. Infection in athletes. Sports Med. 1994, 17, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, C.P.; van Wijk, P.T.; Mathoera, R.B.; de Jongh-Leuvenink, J.; van der Poll, T.; Wever, P.C. Lymphocytopenia and neutrophil–lymphocyte count ratio predict bacteremia better than conventional infection markers in an emergency care unit. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, A.J.; McNamara, M.G.; Šeruga, B.; Vera-Badillo, F.E.; Aneja, P.; Ocaña, A.; Leibowitz-Amit, R.; Sonpavde, G.; Knox, J.J.; Tran, B.; et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Q.; Xu, K. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a promising non-invasive biomarker for symptom assessment and diagnosis of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. BMC Urol. 2023, 23, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, A.; Franzo, G.; Bano, L.; Urbani, L.; Segatore, S.; Rizzardi, A.; Cordioli, B.; Cornaggia, M.; Terrusi, A.; Vasylyeva, K.; et al. No viable bacterial communities reside in the urinary bladder of cats with feline idiopathic cystitis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2024, 168, 105137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermosilla, C.; Caro, T.M.; Silva, L.M.R.; Ruiz, A.; Taubert, A. The intriguing host innate immune response: Novel anti-parasitic defence by neutrophil extracellular traps. Parasitology 2014, 141, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Lomas, J.L.; Grutkoski, P.S.; Chung, C.-S. Fas-ligand mediated apoptosis in severe sepsis and shock. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 35, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defauw, P.A.; van de Maele, I.; Duchateau, L.; Polis, I.E.; Saunders, J.H.; Daminet, S. Risk factors and clinical presentation of cats with feline idiopathic cystitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2011, 13, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, J.L.; Lord, L.K.; Buffington, C.A.T. Sickness behaviors in response to unusual external events in healthy cats and cats with feline interstitial cystitis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2011, 238, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembulingam, K.; Sembulingam, P.; Namasivayam, A. Effect of chronic noise stress on some selected stress indices in albino rats. J. Environ. Biol. 1998, 19, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zahorec, R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratisl. Lekárske Listy 2021, 122, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, M.E.; Casey, R.A.; Bradshaw, J.W.S.; Waran, N.K.; Gunn-Moore, D.A. A study of environmental and behavioural factors that may be associated with feline idiopathic cystitis. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2004, 45, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.R.; Sanson, R.L.; Morris, R.S. Elucidating the risk factors of feline lower urinary tract disease. N. Z. Vet. J. 1997, 45, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlstead, K.; Brown, J.L.; Strawn, W. Behavioral and physiological correlates of stress in laboratory cats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 38, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).