Simple Summary

Animal-assisted interventions (AAIs) include a wide range of activities aimed at improving the health and well-being of people with the help of pets. Although there have been many studies on the effects of these interventions on animal and human wellbeing and health, univocal data on the methodological aspects, regarding type and duration of intervention, operators, involved animal species, and so on, are still lacking. In this regard, several systematic reviews in the scientific literature have already explored and outlined some methodological aspects of animal-assisted interventions. Therefore, we developed an umbrella review (UR) which summarizes the data of a set of suitable systematic reviews (SRs), in order to clarify how these Interventions are carried out. From our results, it is shown that there is a widespread heterogeneity in the scientific literature concerning the study and implementation of these interventions. These results highlight the need for the development and, consequently, the diffusion of protocols (not only operational, but also research approaches) providing for a univocal use of globally recognized terminologies and facilitating comparison between the numerous experiences carried out and reported in the field.

Abstract

Recently, animal-assisted interventions (AAIs), which are defined as psychological, educational, and rehabilitation support activities, have become widespread in different contexts. For many years, they have been a subject of interest in the international scientific community and are at the center of an important discussion regarding their effectiveness and the most appropriate practices for their realization. We carried out an umbrella review (UR) of systematic reviews (SRs), created for the purpose of exploring the literature and aimed at deepening the terminological and methodological aspects of AAIs. It is created by exploring the online databases PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library. The SRs present in the high-impact indexed search engines Web of Sciences and Scopus are selected. After screening, we selected 15 SRs that met the inclusion criteria. All papers complained of the poor quality of AAIs; some considered articles containing interventions that did not always correspond to the terminology they have explored and whose operating practices were not always comparable. This stresses the need for the development and consequent diffusion of not only operational protocols, but also research protocols which provide for the homogeneous use of universally recognized terminologies, thus facilitating the study, deepening, and comparison between the numerous experiences described.

1. Introduction

Animal-assisted interventions (AAIs) have been considered by the International Association of Human–Animal Interaction Organizations (IAHAIO) [1] as recreational, educational, or rehabilitation/therapeutic activities which, due to the presence and mediation of domestic animals, aim to act on pathological situations and on social or educational problems. They have been a subject of interest and study in health disciplines for many years [2,3,4,5,6,7], according to the criteria provided by the “One Health–One Medicine Initiatives", promoting collaboration and communication between different disciplines to work together at local, national, and global levels, establishing an integrated approach [8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

More specifically, as reported by the IAHAIO White Paper ([1], p.5), “An animal-assisted intervention is a goal oriented and structured intervention that intentionally includes or incorporates animals in health, education and human services (e.g., social work) for the purpose of therapeutic gains in humans". These interventions incorporate human–animal teams in formal human services and, as such, these interventions should be developed and implemented using an interdisciplinary approach [1]. AAIs include animal-assisted activity (AAA), animal-assisted therapy (AAT), and animal-assisted education (AAE). AAAs are planned and goal-oriented informal interactions and visits conducted by the human–animal team for motivational, educational, and recreational purposes [1]. AAT is defined as a goal-oriented, planned, and structured therapeutic intervention directed and/or delivered by health, education, or human service professionals (e.g., psychologists) and focused on the socio-emotional functioning of the human recipient, either in a group or individual setting. The professional delivering AAT (...) must have adequate knowledge about the behavior, needs, health, and indicators and regulation of stress in the animals involved [1].

AAT can act as a support to psychotherapeutic activities, understood as a collection of rules or techniques used to conduct mental health treatment, having a relevant set of goals between a professional trained person (known as a therapist) and the recipient or subject of the therapy (known as the client or patient) [15]. In the scientific literature, moreover, it has been considered fundamental that the application of this type of intervention, aimed at the treatment of complex psychic conditions, refers to consolidated and structured theoretical reference models, which present precise indications concerning the theory of the technique to be implemented in the examination room; in order to ensure, as far as possible, the replicability of the intervention itself, its success, and the achievement of the proposed objectives [16,17].

AAE is described as goal-oriented, planned, and structured interventions directed and/or delivered by educational (and related) service professionals. AAE is conducted by qualified (i.e., with degree) general and special education teachers, either in a group or individual setting [1]. They act as support for educational interventions, defined in the literature as an action through which individuals develop or perfect intellectual, social, and physical faculties and attitudes [18].

Finally, as reported by the IAHAIO [1], there is also animal-assisted coaching/counseling (AAC), defined as goal-oriented interventions, which are planned, structured, and directed and/or provided by authorized professionals (e.g., coaches or consultants) and assisted by animals. The coach/consultant (...) must have adequate training on the behavior, needs, health, and indicators and stress regulation of the animals involved. They provide support for consultancy activities, interventions aimed at promoting the development and use of the client’s potential, helping them to overcome any personal difficulties in which one person supports another in achieving a specific goal [19].

As above, the various areas in which the AAIs apply (AATs, AAAs, AAE) have been defined with respect to the terminology (although sometimes they often overlap) and there exists various scientific evidence of their effectiveness. Given the complexity and the variety of these interventions, there is still a strong discussion with respect to the definitions (i.e., used terminology) and the corresponding applied methodologies [12,13]. In addition, on one hand, few studies have been carried out with regard to health protocols aimed at guaranteeing the safety of the setting and users/patients involved in the these interventions [12,20,21,22,23,24] and, on the other hand, there are no exact univocal and clear regulations regarding the applied methodologies, the most appropriate practices for their implementation, and the training of AAI operators [2,12]. In the literature, it has often been strongly highlighted that the described methodologies are not always clear and that terminologies are not always univocally used [25]. Furthermore, the presence of poor references to the operating protocols used, variables of interest, effects of the SRs on the scientific community, and results or limits of studies are often lamented [25]. Research designs are often described by anecdotal facts, referring to single cases with few links to theoretical frameworks [26].

This topic also provided motivation for the drafting of numerous systematic reviews (SRs) or Meta-Analyses [25,26]; for this reason, we consider umbrella reviews (URs) of systematic reviews (SRs) [27] to be a fast and effective way of exploring the orientation of the scientific community and getting an idea of the state-of-the-art regarding such a complex topic as this. As a study group aimed at deepening the good practices for these interventions, we have realized this paper with the intention of offering a “snapshot" of this topic to interested readers. For this purpose, we have explored the literature on the subject, consulting the SRs that deepened the methodological aspects of the studies examined, with attention to the characteristics of the settings implemented and the terminology used. We believe that this work can be useful in comparing the characteristics of the many AAIs described in the scientific literature and, for this reason, it is aimed at all operators involved in AAI research. Moreover, establishing consistency among the terminology and methodological approaches of these interventions could provide further useful support to clinical studies and researchers, as well as starting a new discussion in field of AAIs. Finally, there have been no URs with this objective, except for the work of Stern and Chur-Hansen [28] which aimed to explore SRs related to equine-assisted interventions (EAIs) specifically.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out following Aromataris and Munns [29] in the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual, to realize an umbrella review following the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)” guidelines [30]. Currently, URs are rapidly spreading as a fast and effective means of spreading and presenting evidence content in medical knowledge [28]. In the literature, however, it has been clearly indicated that, in order to carry out solid scientific works, it is necessary that the operating protocols are clearly specified, the variables of interest are clearly defined, the effects of the SRs on the scientific community are indicated, the results are clearly reported, that software is used appropriately, and the limits of the work done are underlined [27]. Therefore, the study procedures were defined first in an operational protocol that specified the research strategies, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusions Criteria

In this UR, although we also explored the possibility of a gray literature search, only SRs in the English language published in international peer-reviewed and high-impact indexed journals were included, in order to ensure a higher quality of results. The subject area and research domain were indicated.

Furthermore, only papers published during last six years (2013–2019) were selected, to ensure a more recent overview of the scientific literature.

In terms of content, both qualitative and quantitative SRs were included, but only those containing information about the terminology explored in SRs (e.g., AAI, AAA, or AAT), in which the terminology was considered eligible and the methodological aspects used to realize interventions were examined (e.g., frequencies and length of sessions; duration of treatment; users, animals, and operators involved).

2.2. Search Strategy

Our research was conducted following the three-phase search process recommended in the manual for umbrella reviews of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [29]. Papers were collected by searching on the PubMed [31], Cochrane [32], and Google Scholar [33] search engines (JBI First step).

In order to define the search query, we added (in the final strings) each of the following terminologies about the animals and the main animal species involved: Dog/Equine/Animal. We combined these with the following terms which refer to the kind of interventions and to related methodologies: Intervention/Activity/Therapy/Education/Coaching/Counseling. All terms were selected based on international reference guidelines [1]. In addition, terms relating to the involvement of Dog and Horses were included, considering that these species are the most involved in such interventions [1].

In the PubMed database, we inserted the term “Meta-Analysis [ptyp] OR Systematic [sb]”, to select only SRs. The same search strategy was adapted for the other databases examined, and is available from the authors upon request (JBI Second step).

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

The information was extracted from each SR included in the UR in order to achieve the goal. All data were entered into an Excel data set. Data relating to terminologies used, reference disciplines, animal species and operators involved, and variations of the settings were collected. Additional data were extracted to facilitate identification of the study (i.e., first name, year of publication, journal).

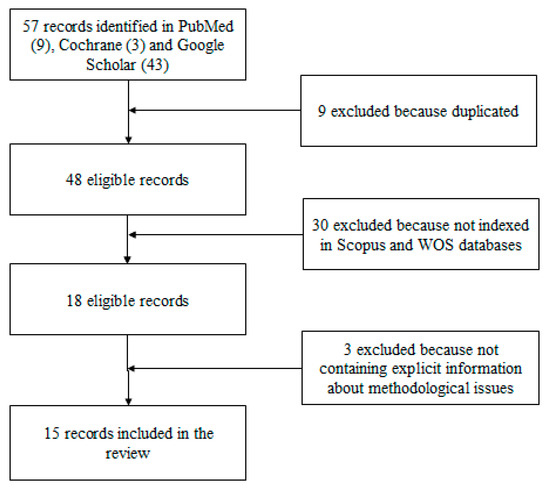

The search query identified 57 articles (11 in PubMed, 3 in Cochrane Library, and 43 in Google Scholar). After evaluating all articles for titles and abstracts, papers were selected and, after removing duplicates, only papers published in journals indexed on Web of Sciences [34] and Scopus [35] were included (JBI Third Step). Finally, a total of 15 SRs met the inclusion criteria, plus one that was found through a hand search. Figure 1 represents the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow-chart process [30] of study selection. Two researchers (A.S. and F.D.) examined the papers independently.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) process flowchart.

Moreover, the quality of the included reviews was evaluated using a score which was assigned according to the Health Evidence tool [36]. Each study was scored in the range from 0 to 10: Weak study quality if the score was four or less; medium quality, if the score ranged from 5–7; high quality, if it was in the range of 8–10. The score quantified the strength of the data in the studies included in each SR and was not an inclusion criterion. The inter-judge agreement was calculated (and independently identified by two judges) as a measure of reliability, assessed by Cohen’s kappa. Every disagreement was solved by intervention of the senior author (A.S.).

The 15 SRs included in the results are indicated by the name of the first author and the year and are listed in order of recency; the full references will be reported among those in the bibliography, indicated with an asterisk.

3. Search Results

3.1. Process of Selection and Inclusion of Studies

The following flowchart (Figure 1) shows the process and the criteria for inclusion of the final results.

3.2. Summary of Results

The results highlight how most of the SRs were published in journals belonging to the medical area and analyzed studies generally aimed at users with mental disorders. Nevertheless, in many cases, it was difficult to detect the correspondence between the terminologies explored, those used in the studies considered eligible, and the methodological aspects described (e.g., number and length of sessions, duration of treatment). This information often appeared to be interchangeable or superimposable. Furthermore, in most studies, the species involved were dogs and horses, but it was not always clear whether the operators involved were included in a specific AAIs training.

3.3. Description of Results

In this section, we explore these results in more detail. Table 1 shows the subject areas, indicated by the Scopus [35] and Web of Science [34] indexed engines, to which the journals that the included SRs were published in belong.

Table 1.

Indicated disciplinary areas in systematic reviews (SRs) included.

It is clear that all of the SRs were published in journals relating to scientific disciplinary areas related to the health sector and most (about 60%) of them [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] belonged to the medical and health sector, while the rest 40% [47,48,49,50,51] fell under other disciplines (i.e., psychology, veterinary medicine, nursing, and occupational therapy).

In Table 2, on the other hand, the users to whom the AAIs examined in the SRs were (mainly) addressed are indicated.

Table 2.

Involved patients or users in animal-assisted interventions (AAIs), according to each SR.

The included SRs highlighted that most of the studies were aimed at patients with psychiatric conditions [37,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,47,50,51], while the others were aimed to patients with deterioration or cognitive delay [42,47,49]; in all cases, these were patients who needed or were involved in rehabilitation treatments.

In Table 3, the considerations of the methodological aspects relating to the studies examined in the SRs are indicated.

Table 3.

Indicated terminologies and methodologies.

It should be noted that, in many cases, although the research object of the SRs was a specific method of intervention, studies presenting other types were also considered eligible: For example, some SRs aimed at exploring the AATs had also included works relating to AAAs or, generically, AAIs [38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

The result, therefore, has an important variability in the settings described (where indicated), whose comparison appears very complex; in fact, the duration of the treatments indicated as “AATs” ranged from four consecutive days [48] to 18 months [49]; that of the “AAAs” from three weeks to two years [48]; that of the “AAIs” from 4 to 25 weeks [51]; and that of the other modalities from ten days [41] to a year [50].

The frequency indicated in the “AATs” ranged from daily [41] to once every two weeks [38]; in the “AAAs” from three sessions a week to one every two weeks [48]; in “AAIs" ranged from daily [41] to one session per week [51]; and, in the other modalities, once or twice a week [39].

Finally, the duration of the individual sessions, in the modalities indicated as “AATs”, varied from 6 min to one whole day [37]; in the “AAAs”, from 15 [41] to 120 min [37]; in the “AAIs", from 10 [37] to 180 min [40]; and, in the other modes, from the three [48] to 240 min [50]. Table 4. shows the animal species and the operators involved, as indicated by the SRs.

Table 4.

Involved interventionists/operators and animals.

The professional figures involved seem to be manifold. The most suitable were Dog/Animal Handlers [37,40,41,43,47,48,49,50] and psychologists [40,41,43,49,50]. In any case, they were not always described as having specific training in this regard, nor were the criteria by which they were chosen for the management of the interventions clear. As for the animals, however, dog was the main species involved (in all SRs, except for the one prepared by Mapes and Rosen [45]), followed by horse [37,38,42,45,46,48,49,50].

3.4. Quality Assessment of the Studies

Regarding the quality of the included studies (Table 5), based on the above-mentioned criteria, all chosen reviews had comprehensively good quality, as none of them had a quality score of less than 7 (moderate quality). Reliability as assessed by Cohen’s kappa was .91, indicating strong agreement between the judges.

Table 5.

General description and evaluation of included reviews’ characteristics.

4. Discussions

From the analysis of the included papers, it is possible to deduce that AAIs are widely recognized in the literature, as they are widespread in the medical sector and particularly useful in the rehabilitation field [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46]. Despite this, in the SRs considered, it can be highlighted that these descriptions do not always correspond to the implementation of suitably corresponding operating practices; or, at least, to the use of univocal procedures, standardized and recorded in theoretical models recognized as indispensable for health interventions [37,38,39,49]. The authors have highlighted the widespread lack of structured research designs, definitive objectives, criteria for choosing the animals involved and the operators involved, and health protocols aimed at ensuring the safety of the participants involved [37,38,39,49].

The SRs seemed to agree on two additional aspects: Firstly, the frequent involvement of dogs and horses [40,45,46], even the ways in which their presence can facilitate the trend of the activities. These preferences could be related, for dogs, to a long history of co-evolution with humans [2,52] and, for horses, to a greater predisposition by the patients involved [53]. Another aspect of concordance between the SRs is the urgent need to structure and implement AAIs characterized by specific qualitative and quantitative studies that highlight the methodological rigor and the effects of the interventions described; all, in fact, highlighted the vast heterogeneity of the analyzed works as being a limit and puts them at risk of not being useful as a resource for the scientific community.

This concern is highly acceptable. For example, we highlight the case of interventions indicated as therapies/psychotherapies, for which, as processes for the treatment of complex clinical conditions, the importance of theoretical and methodological rigor has been widely underlined [2,16]. In fact, theoretical constructs or models are rarely indicated or, if there is a diversity of approach, it is with reference to the different clinical conditions of the patients indicated. Furthermore, in the SRs, their descriptions (where present) often appeared superimposable to those of interventions indicated as another type; in terms of number of meetings, their frequency, set objectives, and training of the operators involved. For example, therapies/psychotherapies have also been considered as interventions carried out by operators whose training is not always specified or whose duration is very short, whereas it is considered essential that they are carried out by adequately trained personnel [2,12,16] and who take time to establish a therapeutic relationship that can promote the treatment of the clinical condition involved [17].

However, it must also be said that, in some cases, although the SRs strongly emphasized how this confusion is limiting for the study of AAI, the results of many were equally heterogeneous. In several SRs, in fact, a frequent incongruity between the terminologies explored by the researchers (among the most frequent: AAIs and AATs) and the papers considered eligible was evident, describing interventions in which the terms used were often juxtaposed and whose practices did not always appear to be comparable, being very varied both in terms of organization of the setting (i.e., the frequency of the sessions varies from daily to monthly, the duration of the sessions from a few minutes to many hours) and the involvement of professional figures [38,39,40,41,42,43,51].

Furthermore, this aspect is to be considered as an important limit for the exploration of these interventions, as it makes the deepening of the scientific literature and the study of the specific AAI protocols complex, creating further difficulties in the analysis of their characteristics, their replicability and, most importantly, the effects of the techniques used on the clinical conditions treated [11,12,54].

Limits of Our Study

This study has several limitations. First, the heterogeneity of the data collected did not allow for a meta-analysis. In fact, many SRs presented only qualitative data or did not present important information that would allow us to carry out statistical comparisons between the various studies described (e.g., divide studies according to the ages of the users). However, another limitation is that we did not include meta-analyses among our results: This corresponded to an important lack of quantitative data, which did not allow us to conduct all of the analyses proposed by the JBI guidelines (e.g., estimating a common effect size or performing a stratification of evidence) [29]. On one hand, these limitations can be considered an important index of the heterogeneity that characterizes the literature on AAIs and, on the other hand, they can provide a stimulating starting point for the realization of new research.

5. Conclusions

The results of this UR highlight that, within the high-impact scientific literature, bibliographic research on AAIs consider them as interventions belonging to the health area, which are particularly aimed at the rehabilitation field. However, despite their wide diffusion, the effects of such interventions on the clinical conditions examined do not seem to be univocally defined, as well as their functioning in the clinical and therapeutic setting. AAIs are mainly dealt with in the health sector (i.e., AAT), concerning the treatment of mental disorders with the particular involvement of dogs and horses, and with operators at different levels of training (although specific training for AAIs is not always indicated). Nevertheless, in this field of study, there is not always a univocal use of the terminologies used to indicate the different types of interventions carried out, despite the indications recognized at an international level [1]. At the methodological level, in particular relating to the structuring of the described settings (i.e., number and length of sessions, duration of treatment), the characteristics described in the various studies appear superimposable and there was no unequivocal correspondence with the typology of intervention indicated. These results are in agreement with the literature on the subject, in which there have been complaints of how, in AAT and AAA in the healthcare facilities, it is desirable that the animal (particularly for dogs) could be handled by a trained professional in an interspecific relationship and according to interdisciplinary principles, who is able to take charge of the animal’s health and evaluate the zoonotic risk in real-time (e.g., a veterinarian) [12,55].

This information is indicative of the widespread heterogeneity present in the literature concerning the study and implementation of AAIs. Therefore, there is a need for the development, and consequent diffusion, of protocols (not only operational, but also for study and research), which provide for a univocal use of globally recognized terminologies which facilitate comparison between the numerous experiences carried out and reported in the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and L.F.M.; data curation, F.D., R.C.C., A.A., and A.S.; investigation, A.S. and F.D.; methodology, F.D., R.C.C., and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., F.D. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.S., A.F. and L.F.M.; supervision, L.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- International Association of Human Animal Interaction Organizations (IAHAIO) IAHAIO White Paper 2014, Updated for 2018. The IAHAIO Definitions for Animal Assisted Intervention and Guidelines for Wellness of Animals Involved in AAI. 2018. Available online: http://iahaio.org/wp/wpcontent/uploads/2018/04/iahaio_wp_updated-2018-final.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Menna, L.F. The Scientific Approach to Pet. Therapy. The Method and Training According to the Federician Model; University of Naples Federico II: Naples, Italy, 2016; ISBN 9791229939918. [Google Scholar]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Gerardi, F.; Di Maggio, A.; Milan, G. Evaluation of the efficacy of animal-assisted therapy based on the reality orientation therapy protocol in Alzheimer’s disease patients: A pilot study. Psychogeriatrics 2016, 16, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Gerardi, F.; Sansone, M.; Di Maggio, A.; Di Palma, A.; Perruolo, G.; D’Esposito, V.; Formisano, P. Efficacy of animal-assisted therapy adapted to reality orientation therapy: Measurement of salivary cortisol. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 19, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, A.H.; Weaver, J.S. The human-animal bond and animal assisted intervention. In Oxford Textbook of Nature and Public Health. The Role of Nature in Improving the Health of a Population; van den Bosch, M., Bird, W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780198725916. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.I.; Lewis, S.; Marcham, L.; Palicka, A. Treatment of dog phobia in young people with autism and severe intellectual disabilities: An extended case series. Contemp. Behav. Health Care 2018, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, C.; Tucha, L.; Talarovicova, A.; Fuermaier, A.; Lewis Evans, B.; Tucha, O. Animal-Assisted Interventions for Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Theoretical Review and Consideration of Future Research Directions. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 118, 292–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsstag, J.; Schelling, E.; Waltner-Toews, T.M. From “one medicine” to “one health” and systemic approaches to health and well-being. Prev. Vet. Med. 2011, 101, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurer, J.M.; Mosites, E.; Li, C.; Meschke, S.; Rabinowitz, P. Community-based surveillance of zoonotic parasites in a “One Health” world: A systematic review. One Health 2016, 2, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, P.A.; Mazet, J.A.; Clifford, D.; Scott, C.; Wilkes, M. Evolution of a transdisciplinary “One Medicine-One Health” approach to global health education at University of California, Davis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 92, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchcliffe, S. More than one world, more than one health: Re-configuring interspecies health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 129, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Todisco, M.; Amato, A.; Borrelli, L.; Scandurra, C.; Fioretti, A. The human-animal relationship as the focus of animal-assisted interventions: A one-health approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hediger, K.; Meisser, A.; Zinsstag, J. A One Healtth Research Framework for Animal Assisted Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res.Public Health 2019, 16, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinette, C.; Saffran, L.; Ruple, A.; Deem, S.L. Zoos and public health: A partnership on the One Health frontier. One Health 2017, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novalis, P.N.; Singer, V.; Peele, R. Clinical Manual of Supportive Psychotherapy, 2nd ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781615371655. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbard, G.O.; Del Corno, F.; Lingiardi, V. Le Psicoterapie. Teorie e Modelli d’Intervento. Psychotherapies. Theories and Intervention Models; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Roma, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-8860303523. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D.N. The Present Moment in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life; WW Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0393704297. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, I.R.; Mills, G.E.; Airasian, P.W. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications, 12nd ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780132613170. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, S.; Whybrow, A. Handbook of Coaching Psychology: A Guide for Practitioners; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1583917077. [Google Scholar]

- Maurelli, M.P.; Santaniello, A.; Fioretti, A.; Cringoli, G.; Rinaldi, L.; Menna, L.F. The Presence of Toxocara Eggs on Dog’s Fur as Potential Zoonotic Risk in Animal-Assisted Interventions: A Systematic Review. Animals 2019, 19, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerardi, F.; Santaniello, A.; Del Prete, L.; Maurelli, M.P.; Menna, L.F.; Rinaldi, L. Parasitic infections in dogs involved in animal-assisted interventions. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 17, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, D.E.; Siebens, H.C.; Mueller, M.K.; Gibbs, D.M.; Freeman, L.M. Animal-assisted interventions: A national survey of health and safety policies in hospitals, eldercare facilities, and therapy animal organizations. Am. J. Infect. Control 2017, 45, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardin, P.; Brown, J.; Wright, M.E. Prevention of transmitted infections in a pet therapy program: An exemplar. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, R.; Bearman, G.; Brown, S.; Bryant, K.; Chinn, R.; Hewlett, R.; George, G.; Goldstein, E.; Holzmann-Pazgal, G.; Rupp, M.; et al. Animals in Healthcare Facilities: Recommendations to Minimize Potential Risks. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 36, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A. (Ed.) Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice; Academic Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-12-801292-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dicé, F.; Santaniello, A.; Gerardi, F.; Paoletti, A.; Valerio, P.; Freda, M.F.; Menna, L.F. Gli interventi assistiti dagli animali come processi di promozione della salute. Una review sistematica. (Animal assisted interventions as processes for health promotion. A systematic review). Psicol. Della Salut. 2018, 3, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, P.; Radua, J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.; Chur-Hansen, A. An umbrella review of the evidence for equine-assisted interventions. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. (Eds.) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available online: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubMed. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Cochrane Library. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/about-cochrane-library (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.it/ (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Web of Science. Available online: https://clarivate.com/products/web-of-science/ (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Scopus. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/ (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Health Evidence. Quality Assessment Tool-Review Articles. Available online: https://www.healthevidence.org/documents/our-appraisal-tools/quality-assessment-tool-dictionary-en.pdf (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Bert, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Camussi, E.; Pieve, G.; Voglino, G.; Siliquini, R. Animal Assisted Intervention: A systematic review of benefits and risks. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 8, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charry-Sánchez, J.D.; Pradilla, I.; Talero-Gutiérrez, C. Animal-assisted therapy in adults: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018, 32, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, E.L.; Hawkins, R.D.; Dennis, M.; Williams, J.M.; Laurie, S.M. Animal-assisted therapy for schizophrenia and related disorders: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 115, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.G.; Rice, S.M.; Cotton, S.M. Incorporating animal-assisted therapy in mental health treatments for adolescents: A systematic review of canine assisted psychotherapy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamioka, H.; Okada, S.; Tsutani, K.; Park, H.; Okuizumi, H.; Handa, S.; Oshio, T.; Park, S.J.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Abe, T.; et al. Effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2014, 22, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimova, B.; Toman, J.; Kuca, K. Effectiveness of the dog therapy for patients with dementia—A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrá, P.P.; da Freiria Moretti, T.C.; Avezum, L.A.; Sadako Kuroishi, R.C. Animal assisted therapy: Systematic review of literature. CoDAS 2019, 31, e20180243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brelsford, V.L.; Meints, K.; Gee, N.R.; Pfeffer, K. Animal-Assisted Interventions in the Classroom—A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapes, A.L.; Rosen, L.A. Equine-Assisted Therapy for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive Literature Review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 3, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.Z.Z.; Xiong, P.; Chou, U.I.; Hall, B.J. “We need them as much as they need us”: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence for possible mechanisms of effectiveness of animal-assisted intervention (AAI). Compl. Ther. Med. 2018, 41, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagwood, K.E.; Acri, M.; Morrissey, M.; Peth-Pierce, R. Animal-assisted therapies for youth with or at risk for mental health problems: A systematic review. Appl. Develop. Sci. 2017, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakimicki, M.L.; Edwards, N.E.; Richards, E. Animal-Assisted Intervention and Dementia: A Systematic Review. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2018, 28, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maber-Aleksandrowicz, S.; Avent, C.; Hassiotis, A. A Systematic Review of Animal-Assisted Therapy on Psychosocial Outcomes in People with Intellectual Disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 49–50, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Haire, M.E.; Guérin, N.A.; Kirkham, A.C. Animal-Assisted Intervention for trauma: A systematic literature view. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maujean, A.; Pepping, C.A.; Kendall, E. A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials of Animal-Assisted Therapy on Psychosocial Outcomes. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, M.; Mitsui, S.; En, S.; Ohtani, N.; Ohta, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Onaka, T.; Mogi, K.; Kikusui, T. Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds. Science 2015, 348, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausberger, M.; Roche, H.; Henry, S.; Visser, E.K. A review of the human-horse relationship. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 109, 11–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Amato, A.; Ceparano, G.; Di Maggio, A.; Sansone, M.; Formisano, P.; Cimmino, I.; Perruolo, G.; Fioretti, A. Changes of Oxytocin and Serotonin Values in Dialysis Patients after Animal Assisted Activities (AAAs) with a Dog—A Preliminary Study. Animals 2019, 9, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A. Human and Veterinary medicine: The priority for public health synergies. Vet. Ital. 2008, 44, 577–582. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).