Abstract

Viral infections including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) pose an ongoing threat to human health due to the lack of effective therapeutic agents. The re-emergence of old viral diseases such as the recent Ebola outbreaks in West Africa represents a global public health issue. Drug resistance and toxicity to target cells are the major challenges for the current antiviral agents. Therefore, there is a need for identifying agents with novel modes of action and improved efficacy. Viral-based illnesses are further aggravated by co-infections, such as an HIV patient co-infected with HBV or HCV. The drugs used to treat or manage HIV tend to increase the pathogenesis of HBV and HCV. Hence, novel antiviral drug candidates should ideally have broad-spectrum activity and no negative drug-drug interactions. Myxobacteria are in the focus of this review since they produce numerous structurally and functionally unique bioactive compounds, which have only recently been screened for antiviral effects. This research has already led to some interesting findings, including the discovery of several candidate compounds with broad-spectrum antiviral activity. The present review looks at myxobacteria-derived antiviral secondary metabolites.

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens the effective treatment, control and management of an increasing range of infections caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites and fungal pathogens [1]. Development of effective therapies to suppress human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) has been achieved with great success [2]. However, the medicines are not curative, and therefore more efforts in HIV and HBV drug discovery are directed toward longer-acting therapies or compounds with new mechanisms of action that could potentially lead to a cure or complete eradication of the viruses [2]. In 2010, an estimated 7–20% of people starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) globally had drug-resistant HIV [3]. Some countries have recently reported levels of 15% amongst those starting HIV treatment, and up to 40% among people re-starting therapy [3]. Of great concern are the high levels of viral resistance towards nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) as recently found in Kenyan children [4]. In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that everyone living with HIV should start on antiretroviral treatment. Hence, increased ART resistance is expected as more people start ART [3]. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved anti-HIV drugs are classified into eight classes according to modes of action [5]. The common side effects of Abacavir® and other NRTIs are that they can cause life-threatening side effects, including a serious allergic reaction, a build-up of lactic acid in the blood, and hepatotoxicity [6,7]. In fact, each drug class of the FDA approved anti-HIV drugs has side effects, and some are contra-indicated for co-infected patients with HIV and HBC or HCV [8]. On the other hand, all influenza A viruses circulating in humans were reported to be resistant to Amantadine® and Rimantadine®, two essential antivirals for treatment of epidemic and pandemic influenza A. However, the frequency of resistance to Oseltamivir® another antiviral with different mode of action for treating influenza A remains low at 1–2% [3]. Treatment failure of antivirals has been suggested to be caused by the emergence of recombinant viruses, drug resistance, and cell toxicity [9,10]. Compounds with a different mode of action can play an essential role in overcoming AMR. Viral disease such as influenza spreads fast and knows no borders, with the vast masses of people travelling all over the globe due to efficient transport systems. Hence, there is an urgent need for international collaboration to identify new antiviral agents with new modes of action and better efficacy.

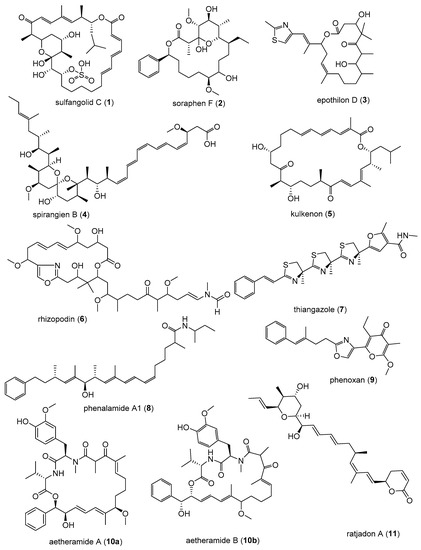

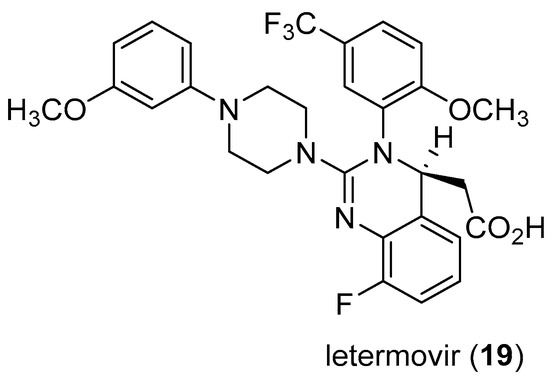

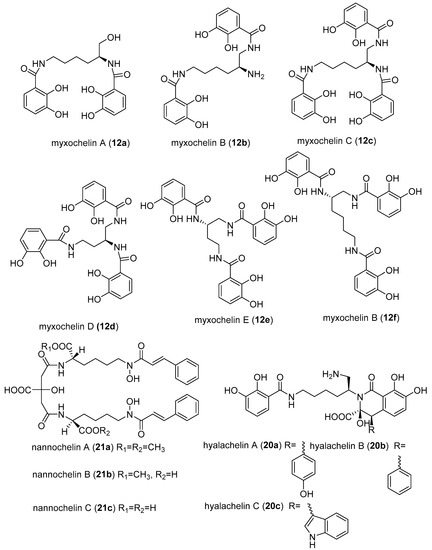

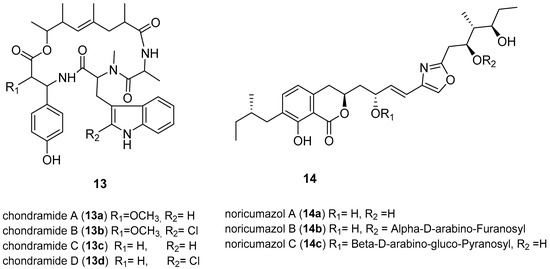

Myxobacteria are well-known to be producers of biologically active secondary metabolites with novel carbon skeletons and new modes of action [11,12,13]. Many compounds isolated from myxobacteria have recently been found to have impressive antiviral activity. More so, some have been found to have an unusual broad-spectrum antiviral activity [11,12,14].

2. Myxobacteria

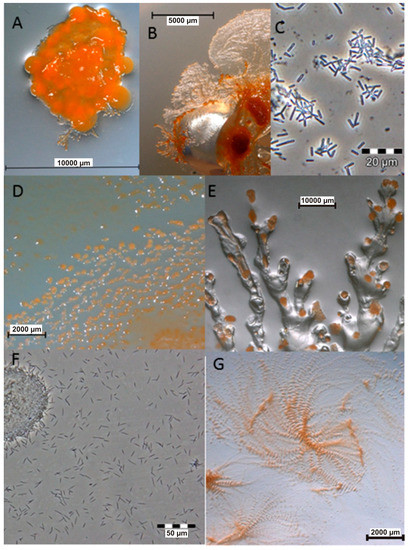

Myxobacteria are δ-proteobacteria belonging to the order Myxococcales. They are rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacteria that exhibit gliding motility and swarm on solid surfaces. Under nutrient-limiting conditions, they form species-specific fruiting bodies (Figure 1) [15]. Within these fruiting bodies, some vegetative cells convert to myxospores, which are desiccation-resistant and can survive over decades. Under appropriate conditions the spores germinate [16]. These soil-dwelling microorganisms have also been isolated from other habitats such as the bark of trees, oceans, freshwater lakes, and herbivore dung [15,17]. Myxobacteria have also been isolated from extreme environments such as desert soils [18]. Numerous unique classes of secondary metabolites have been isolated from myxobacteria, the majority of which are biogenetically derived from polyketide synthases (PKSs) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NPRSs) or a hybrid of PKSs and NPRSs [12,15,19,20]. PKSs and NPRSs are enzymatic “assembly lines” of complex multi-step biosynthetic pathways for making compounds by catalysing the stepwise condensation of a starter unit with small monomeric building blocks [19]. The ability to produce unique metabolites is conferred by the creative biosynthetic pathways and the large genome of 9–14 Mb [21], consistent with the strengthening correlation between genome size and the extent of secondary metabolites produced [21,22,23,24,25]. In fact, the sequenced genomes of myxobacteria are the largest yet known from any bacterium [20,21,22,23,25]. In the last 35 years, over 100 new carbon skeleton secondary metabolites, with over 600 analogues, have been isolated from over 9000 strains of myxobacteria [12]. The metabolites exhibited antifungal, antibacterial, antimalarial, antitumor, and anti-immunomodulatory properties some with novel modes of action and have been reviewed extensively [12,20,26]. Microorganisms are valuable as producers of bioactive metabolites because they can be cultivated in bioreactors from as little as below 5 mL to large scales of over 100,000 L, making the production of natural products independent of season, locality, or climate [15]. Furthermore, conditions in a bioreactor are controllable to optimise production of the desired outcome. Particularly important as illustrated by Zeeck et al., 2002 in the ‘OSMAC’ (One Strain-Many Compounds) approach, which revealed that microorganisms do not exhaust their potential for producing metabolites under standard laboratory conditions [27].

Figure 1.

Images of myxobacteria. (A–C): Sorangium cellulosum; (A): Fruiting bodies; (B): Swarming on agar plate; (C): Cells from the liquid medium under the light microscope. (D–E): Images of the producers ofthiangazole (7), phenalamide A1 (8) and phenoxan (9), from agar plates; (D): Myxococcus stipitatus; (E): Polyangium species; (F–G): Angiococcus disciformis (strain An d30) producer of myxochelins; (F): culture under the light microscope from liquid media; (G): culture on agar plate. Images provided by Joachim Wink (HZI Braunschweig).

4. Conclusions

The reported antivirals discoveries call for more screening of myxobacterial-derived compounds, especially against other medically important viruses. Myxobacteria have demonstrated to be creative producers of molecules that can have valuable applications as possible lead structures for the development of antiviral drugs. Some broad-spectrum antivirals such as soraphen A could be of interest for the possibility of treating co-infection cases. Further, the possibility of using these myxobacteria derived secondary metabolites for treating both opportunistic infections and the HIV could be explored. The challenge of some compounds being toxic can be approached by structure modification for possibility of reducing toxicity while maintaining efficacy, as observed with the analogues of soraphen and noricumazoles. Moreover, some metabolites found to have potent antiviral activity may not be used as drugs themselves, due to toxicity, but they can serve as excellent tools to study and understand the viral invasion. This valuable information can be used to select other metabolites with similar mechanisms of action or structural modification of the compounds, to reduce their toxicity without substantially altering the activity. This ability of myxobacteria to produce such a vast number of secondary metabolites is most likely brought about by many years of evolution to adapt to survival in an ecological condition of competitive existence in the presence of competitors and invaders such as fungi, bacteriophages, and other bacteria. A recent comprehensive study involving molecular phylogeny with HPLC-MS profiling has revealed an unparalleled diversity of metabolites, along with strong correlations of the metabolite production to the phylogenetic position of the corresponding producer organisms [81]. Therefore, it appears promising to isolate more myxobacteria that represent novel genera and species from unexplored environments and screen them systematically for the production of further unique compounds with antiviral activities.

Author Contributions

Draft Preparation, L.S.M.; Editing of manuscript, M.S.

Funding

L.S.M. was supported by a Ph.D. grant from the DAAD-NACOSTI Scholarship funding program number (2014) 57139945 (91530969).

Acknowledgments

L.S.M. is highly indebted to DAAD-NACOSTI for the PhD Scholarship and TSC-Kenya for study leave. We are grateful to Joachim Wink and the technical staff of the HZI, Wera Collisi, Aileen Gollasch, Stephanie Schulz, Birte Trunkwalter and Klaus-Peter Conrad for the images of myxobacteria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nübel, U. Emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance: Recent insights from bacterial population genomics. In How to Overcome the Antibiotic Crisis—Facts, Challenges, Technologies & Future Perspective; Stadler, M., Dersch, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Volume 398, pp. 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, W.; Cox, C. Current Landscape of Antiviral Drug Discovery. F1000 Rev. 2016, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance. Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- Dziuban, E.J.; DeVos, J.; Ngeno, B.; Ngugi, E.; Zhang, G.; Sabatier, J.; Wagar, N.; Diallo, K.; Nganga, L.; Katana, A.; et al. High prevalence of Abacavir-associated L74V/I mutations in Kenyan children failing antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017, 36, 758–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Antiretroviral Drugs Used in the Treatment of HIV Infection. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/Illness/HIVAIDS/Treatment/ucm118915.htm (accessed on 22 May 2018).

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. Drugs That Fight HIV-1. Available online: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/upload/HIV_Pill_Brochure.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2018).

- DailyMed. Drug Listing Certification. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/index.cfm (accessed on 22 May 2018).

- Reust, C.E. Common adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy for HIV disease. Am. Fam. Phys. 2011, 83, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar]

- Tantillo, C.; Ding, J.; Jacobo-Molina, A.; Nanni, R.G.; Boyer, P.; Hughes, S.H.; Pauwels, R.; Andries, K.; Jansen, P.A.; Arnold, E. Locations of anti-AIDS drug binding sites and resistance mutations in the three-dimensional structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: Implications for mechanisms of drug inhibition and resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 243, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlotsky, J. Treatment failure and resistance with direct-acting antiviral drugs against Hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsoudakis, G.; Romero-Brey, I.; Berger, C.; Pérez-Vilaró, G.; Monteiro, P.P.; Vondran, F.W.R.; Kalesse, M.; Harmrolfs, K.; Müller, R.; Martinez, J.P.; et al. Soraphen A: A broad-spectrum antiviral natural product with potent anti-hepatitis C virus activity. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, J.; Fayad, A.A.; Müller, R. Natural products from myxobacteria: Novel metabolites and bioactivities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüttel, S.; Testolin, G.; Herrmann, J.; Planke, T.; Gille, F.; Moreno, M.; Stadler, M.; Brönstrup, M.; Kirschning, A.; Müller, R. Discovery and total synthesis of natural cystobactamid derivatives with superior activity against Gram-negative pathogens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 12760–12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerth, K.; Bedorf, N.; Irschik, H.; Höfle, G.; Reichenbach, H. The soraphens: A family of novel antifungal compounds from Sorangium cellulosum (Myxobacteria). J. Antibiot. 1994, 47, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichenbach, H. Myxobacteria, producers of novel bioactive substances. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 27, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerth, K.; Pradella, S.; Perlova, O.; Beyer, S.; Müller, R. Myxobacteria: Proficient producers of novel natural products with various biological activities—Past and future biotechnological aspects with the focus on the genus Sorangium. J. Biotechnol. 2003, 106, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawid, W. Biology and global distribution of myxobacteria in soils. FEMS Microbiol. 2000, 24, 403–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, K.I.; Moradi, A.; Glaeser, S.P.; Kämpfer, P.; Gemperlein, K.; Nübel, U.; Schumann, P.; Müller, R.; Wink, J. Nannocystis konarekensis sp. nov., a novel myxobacterium from an Iranian desert. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, S.C.; Müller, R. Myxobacteria—‘Microbial factories’ for the production of bioactive secondary metabolites. Mol. BioSyst. 2009, 5, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, K.J.; Müller, R. Myxobacterial secondary metabolites: Bioactivities and modes-of-action. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 1276–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korp, J.; Gurovic, M.S.V.; Nett, M. Antibiotics from predatory bacteria. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, B.S.; Nierman, W.C.; Kaiser, D.; Slater, S.C.; Durkin, A.S.; Eisen, J.A.; Ronning, C.M.; Barbazuk, W.B.; Blanchard, M.; Field, C.; et al. Evolution of sensory complexity recorded in a myxobacterial genome. Prod. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15200–15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, S.C.; Müller, R. The impact of genomics on the exploitation of the myxobacterial secondary metabolome. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 1385–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Céspedes, A.D.; Hufendiek, P.; Crüsemann, M.; Schäberle, T.F.; König, G.M. Marine-derived myxobacteria of the suborder Nannocystineae: An underexplored source of structurally intriguing and biologically active metabolites. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneiker, S.; Perlova, O.; Kaiser, O.; Gerth, K.; Alici, A.; Altmeyer, M.O.; Bartels, D.; Bekel, T.; Beyer, S.; Bode, E.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the myxobacterium Sorangium cellulosum. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäberle, T.F.; Lohr, F.; Schmitz, A.; König, G.M. Antibiotics from myxobacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 953–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, H.B.; Bethe, B.; Höfs, R.; Zeeck, A. Big effects from small changes: Possible ways to explore nature’s chemical diversity. ChemBioChem 2002, 3, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, R. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2016, 43, 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Curreli, F.; Kwon, Y.D.; Zhang, H.; Scacalossi, D.; Belov, D.S.; Tikhonov, A.A.; Andreev, A.I.; Altieri, A.; Kurkin, A.V.; Kwong, P.D.; et al. Structure-based design of a small molecule CD4-antagonist with broad spectrum anti-HIV-1 activity. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 6909–6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asim, K.D.; Lin, R.; Shibo, J. Structure-based identification of small molecule antiviral compounds targeted to the gp41 core structure of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 3203–3209. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J.P.; Hinkelmann, B.; Fleta-Soriano, E.; Steinmetz, H.; Jansen, R.; Diez, J.; Frank, R.; Sasse, F.; Meyerhans, A. Identification of myxobacteria-derived HIV inhibitors by a high-throughput two-step infectivity assay. Microb. Cell Fact. 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zander, W.; Irschik, H.; Augustiniak, H.; Herrmann, M.; Jansen, R.; Steinmetz, H.; Gerth, K.; Kessler, W.; Kalesse, M.; Höfle, G.; et al. Sulfangolids, macrolide sulfate esters from Sorangium cellulosum. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6264–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://scifinder.cas.org/scifinder/view/scifinder/scifinderExplore.jsf (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Shen, Y.; Volrath, S.L.; Weatherly, S.C.; Elich, T.D.; Tong, L. A mechanism for the potent inhibition of eukaryotic acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase by soraphen A, a macrocyclic polyketide natural product. Mol. Cell 2004, 16, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlradt, P.F.; Sasse, F. Epothilone B stabilizes microtubuli of macrophages like taxol without showing taxol-like endotoxin activity. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 3344–3346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goodin, S.; Kane, M.P.; Rubin, E.H. Epothilones: Mechanism of action and biologic activity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, J.K.; Tucker, C.; Favours, E.; Cheshire, P.J.; Creech, J.; Billups, C.A.; Smykla, R.; Lee, F.Y.F.; Houghton, P.J. In vivo evaluation of Ixabepilone (BMS247550), A novel epothilone B derivative, against pediatric cancer models. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 6950–6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reboll, M.R.; Ritter, B.; Sasse, F.; Niggemann, J.; Frank, R.; Nourbakhsh, M. The myxobacterial compounds spirangien A and spirangien M522 are potent inhibitors of IL-8 expression. ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurkliewicz, E.; Jansen, R.; Kunze, B.; Trowitzsch-Klenast, W.; Porche, E.; Reichenbach, H.; Höfle, G.; Hunsmann, G. Three new potent HIV-1 inhibitors from myxobacteria. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1992, 3, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowitzsch-Kienast, W.; Forche, E.; Wray, V.; Reichenbach, H.; Jurkiewicz, E.; Hunsmann, G.; Höfle, G. Phenalamide, neue HIV-1-Inhibitoren aus Myxococcus stipitatus Mx s40. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1992, 1992, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Stadler, M.; Gemperlein, K.; Müller, R. Aetherobacter fasciculatus gen. nov., sp. nov. and Aetherobacter rufus sp. nov., novel myxobacteria with promising biotechnological applications. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza, A.; Garcia, R.; Bifulco, G.; Martinez, J.P.; Hüttel, S.; Sasse, F.; Meyerhans, A.; Stadler, M.; Müller, R. Aetheramides A and B, potent HIV-inhibitory depsipeptides from a Myxobacterium of the new genus “Aetherobacter”. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2854–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerth, K.; Schummer, D.; Höfle, G.; Irschik, H.; Reichenbach, H. Ratjadon: A new antifungal compound from Sorangium cellulosum (Myxobacteria) Production, physico-chemical and biological properties. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleta-Soriano, E.; Martinez, J.P.; Hinkelmann, B.; Gerth, K.; Washausen, P.; Diez, J.; Frank, R.; Sasse, F.; Meyerhans, A. The myxobacterial metabolite ratjadone A inhibits HIV infection by blocking the Rev/CRM1-mediated nuclear export pathway. Microb. Cell Fact. 2014, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICTV. Taxonomy. Available online: https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy/ (accessed on 30 April 2018).

- Britt, W.J.; Vugler, L.; Butfiloski, E.D.; Stevens, E.B. Cell surface expression of Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV): Use of HCMV-recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells in analysis of the human neutralizing antibody response. J. Virol. 1990, 64, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arvin, A.M.; Alford, C.A. Chronic Intrauterine and Perinatal Infections. In Antiviral Agents and Viral Diseases of Man; Galassov, G.J., Whitley, R.J., Merigan, T.C., Eds.; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 3, pp. 497–580. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A.K. Human cytomegalovirus: Challenges opportunities and new drug development. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1999, 10, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.; Martinez, A. Novel agents for the treatment of human cytomegalovirus infection. Exp. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2000, 10, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Smith, J.L.; Chen, M.S. Effect of incorporation of Cidofovir into DNA by Human Cytomegalovirus DNA polymerase on DNA elongation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997, 24, 594–599. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, G.; Chou, S.; Quirk, M.R.; Alejo, E.; Jordan, M.C. Detection of ganciclovir resistance mutations and quantitation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA in leucocytes of patients with fatal disseminated CMV disease. J. Infect. Dis. 1996, 173, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassir, M.R.; Emerson, S.G.; Devivar, R.V.; Townsend, L.B.; Drach, J.C.; Taichman, R. Comparison of benzimidazole nucleosides ganciclovir on the in vitro proliferation and colony formation of human marrow progenitor cells. Br. J. Haematol. 1996, 93, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, D.R.; Stoelben, S.; Cober, E.; Ojo, T.; Sandusky, E.; Lischka, P.; Zimmermann, H.; Rübsamen-Schaeff, H. First report of successful treatment of multidrug-resistant cytomegalovirus disease with the novel anti-CMV compound AIC246. Am. J. Transpl. 2011, 11, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NEJM Journal Watch. Letermovir Approved to Prevent CMV Infection and Disease in Transplant Patients. Available online: https://www.jwatch.org/na45554/2017/12/07/letermovir-approved-prevent-cmv-infection-and-disease (accessed on 17 June 2018).

- Schieferdecker, S.; König, S.; Koeberle, A.; Dahse, H.M.; Werz, O.; Nett, M. Myxochelins Target Human 5-Lipoxygenase. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagoba, B.; Vedpathak, D. Medical applications of siderophores. Eur. J. Gen. Med. 2011, 8, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanaga, S.; Obata, T.; Onaka, H.; Fujita, T.; Saito, N.; Sakurai, H.; Saiki, I.; Furumai, T.; Igarashi, Y. Absolute configuration and antitumor activity of myxochelin a produced by Nonomuraea pusilla TP-A0861. J. Antibiot. 2006, 59, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korp, J.; König, S.; Schieferdecker, S.; Dahse, H.M.; König, G.M.; Werz, O.; Nett, M. Harnessing enzymatic promiscuity in myxochelins biosynthesis for the production of 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors. ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 2445–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schieferdecker, S.; König, S.; Simona Pace, S.; Werz, O.; Nett, M. Myxochelin-inspired 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors: Synthesis and biological evaluation. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyanga, S.; Sakurai, H.; Saiki, I.; Onaka, H.; Igarashi, Y. Synthesis and evaluation of myxochelins analogues as antimetastatic agents. Biol. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2724–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosi, H.D.; Hartmann, V.; Pistorius, D.; Reissbrodt, R.; Trowitzsch-Kienast, W. Myxochelins B, C, D, E and F: A new structural principle for powerful siderophores imitating Nature. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitatzis, N.; Kunze, B.; Müller, R. Novel insights into siderophore formation in myxobacteria. Chembiochem 2005, 6, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadmid, S.; Plaza, A.; Lauro, G.; Garcia, R.; Bifulco, G.; Müller, R. Hyalachelins A–C, Unusual Siderophores Isolated from the terrestrial Myxobacterium Hyalangium minutum. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4130–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunze, B.; Trowitzsch-Kienast, W.; Hofle, G.; Reichenbach, H. Nannochelins A, B and C, new iron-chelating compounds from Nannocystis exedens (myxobacteria) production, isolation, physico-chemical and biological properties. J. Antibiot. 1991, 45, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Sarkar, S.; Sarkar, B.; Sharma, B.K.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Prosun, T. Microbial siderophores and their potential applications: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 3984–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Ebola virus Disease. Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ebola-virus-disease (accessed on 5 May 2018).

- Beck, S.; Henß, L.; Weidner, T.; Herrmann, J.; Müller, R.; Chao, Y.; Weber, C.; Sliva, K.; Schnierle, S. Identification of inhibitors of Ebola virus pseudotyped vectors from a myxobacterial compound library. Antivir. Res. 2016, 132, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunze, B.; Jansen, R.; Sasse, F.; Höflen, G.; Reichenbach, H.; Chondramides, A.D. New antifungal and cytostatic depsipeptides from Chondromyces crocatus (Myxobacteria). Production, physico-chemical and biological Properties. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 1262–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichenbach, H. Myxobacteria: A source of new antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 1988, 6, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, J.; Jansen, R.; Irschik, H.; Benson, S.; Gerth, K.; Böhlendorf, B.; Höfle, G.; Reichenbach, H.; Wegner, J.; Zeilinger, C.; et al. Isolation and total synthesis of icumazoles and noricumazoles—Antifungal antibiotics and cation-channel blockers from Sorangium cellulosum. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1256–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasse, F.; Steinmetz, H.; Heil, J.; Höfle, G.; Reichenbach, H. Tubulysins, new cytostatic peptides from Myxobacteria acting on microtubuli. Production, isolation, physico-chemical and biological properties. J. Antibiot. 2000, 53, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Shepard, C.W.; Finelli, L.; Alter, M.J. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

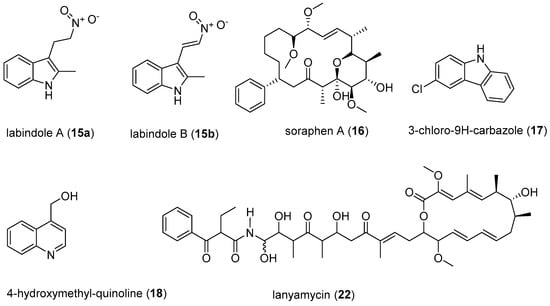

- Mulwa, L.; Jansen, R.; Praditya, D.; Mohr, K.; Wink, J.; Steinmann, E.; Stadler, M. Six heterocyclic metabolites from the Myxobacterium Labilithrix luteola. Molecules 2018, 23, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedorf, N.; Schomburg, D.; Gerth, K.; Reichenbach, H.; Höfle, G.; Bedorf, N.; Schomburg, D.; Gerth, K.; Reichenbach, H.; Höfle, G. Isolation and structure elucidation of soraphen A1α, a novel antifungal macrolide from Sorangium cellulosum. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1993, 1993, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singaravelu, R.; Desrochers, G.F.; Srinivasan, P.; O’Hara, S.; Lyn, R.; Müller, R.; Jones, D.M.; Russell, R.; Pezacki, J.P. Soraphen A: A probe for investigating the role of de novo lipogenesis during viral infection. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015, 1, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentzsch, J.; Hinkelmann, B.; Kaderali, L.; Irschik, H.; Jansen, R.; Sasse, F.; Frank, R.; Pietschmann, T. Hepatitis C virus complete life cycle screen for identification of small molecules with pro- or antiviral activity. Antiviral Res. 2011, 89, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulwa, L.S.; Jansen, R.; Praditya, D.F.; Mohr, K.I.; Okanya, P.W.; Wink, J.; Steinmann, E.; Stadler, M. Lanyamycin, a macrolide antibiotic from Sorangium cellulosum, strain Soce 481 (Myxobacteria). Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 1554–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeganeh, B.; Ghavami, S.; Kroeker, A.L.; Mahood, T.H.; Stelmack, G.L.; Klonisch, T.; Coombs, K.M.; Halayko, A.J. Suppression of influenza A virus replication in human lung epithelial cells by noncytotoxic concentrations bafilomycin A1. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2015, 308, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, T.; Krug, D.; Bozkurt, N.; Duddela, S.; Jansen, R.; Garcia, R.; Gerth, K.; Steinmetz, H.; Müller, R. Correlating chemical diversity with taxonomic distance for discovery of natural products in myxobacteria. Nat. Commum. 2018, 9, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).