Abstract

Three cyanobacterial strains (CB-4, GQSK-2, and LHH-2) with thin, simple filaments were isolated from freshwater habitats in China. In this study, a polyphasic approach, integrating 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic analyses, p-distance calculation, 16S-23S ITS secondary structures, and morphological and ecological observations, was employed to resolve the taxonomic status of these strains. The results confirmed the existence of two new species within a novel genus (Neoleptolyngbya) and one additional new species of Pseudoleptolyngbya (Leptolyngbyaceae): Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis sp. nov. (strain GQSK-2), Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis sp. nov. (strain CB-4), and Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis sp. nov. (strain LHH-2). In the 16S rRNA phylogeny, strains GQSK-2 and CB-4 formed a well-supported, independent lineage sister to the Leptolyngbyopsis clade, while strain LHH-2 clustered with two recognized Pseudoleptolyngbya species in a distinct clade. Sequence similarity analyses revealed that the 16S rRNA gene sequences of GQSK-2 and CB-4 shared a maximum similarity of 94.2% with those of phylogenetically related established genera, and the 16S rRNA gene sequence of LHH-2 exhibited a maximum similarity of 95.7% with its closest Pseudoleptolyngbya relatives, both values below the threshold for cyanobacterial species/genus delineation. Furthermore, comparative analysis of the 16S–23S ITS secondary structures between the three strains and their respective reference strains revealed significant species-specific differences, providing additional evidence for their taxonomic novelty. The discovery of these novel taxa enriches the cyanobacterial diversity in China and lays a theoretical foundation for the conservation and sustainable utilization of algae resources.

1. Introduction

As one of the oldest prokaryotic lineages on Earth, cyanobacteria play crucial ecological roles in freshwater, marine, brackish, and terrestrial environments. They contribute to oxygenic photosynthesis, global carbon/nitrogen cycling, and the production of bioactive secondary metabolites [1,2,3]. Despite their ubiquitous presence across diverse environments, a large portion of cyanobacterial biodiversity remains poorly characterized [4,5]. Thus, comprehensive research and accurate taxonomic identification of cyanobacteria are of great significance [6,7]. The adoption of a polyphasic approach has greatly advanced cyanobacterial taxonomy, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional morphological classification [8,9]. This polyphasic approach establishes a framework for resolving the challenges of identifying cryptic species; many cyanobacteria that are morphologically identical exhibit significant genetic divergence [10,11,12]. This is particularly true for thin filamentous cyanobacteria (with cell diameter < 3.5 μm). In the early classical classification system, all filamentous cyanobacteria lacking heterocytes or akinetes were categorized under the order Oscillatoriales; within this taxon, thin filamentous cyanobacteria were placed in the family Pseudanabaenaceae and the genus Leptolyngbya Anagnostidis and Komárek [13]. However, the application of cell ultrastructure and 16S rRNA molecular sequence analysis to cyanobacterial classification revealed a more complex evolutionary relationship among these filamentous taxa [14]. For example, thylakoids in Oscillatoria-like groups are often radially arranged, whereas thin filamentous cyanobacteria typically have parietal thylakoids, a feature shared with the order Synechococcales [15]. In Hoffmann’s proposed system, the family Pseudanabaenaceae was elevated to the order Pseudanabaenales, which, together with Synechococcales, was classified under the subclass Synechococcophycideae [15]. In the subsequent eight-order classification system, Pseudanabaenales was subsumed under Synechococcales; this order included all small unicellular coccoid and thin filamentous cyanobacteria with simple morphologies, and thin filamentous cyanobacteria with sheaths were assigned to the family Leptolyngbyaceae [16]. Mai et al. conducted a taxonomic revision of the family Leptolyngbyaceae; the findings demonstrated that taxa previously classified under Leptolyngbyaceae can be further delineated into four distinct family-level clades, that is, Leptolyngbyaceae, Oculatellaceae, Prochlorotrichaceae, and Trichocoleaceae [17]. A groundbreaking revision of cyanobacterial taxonomy in 2023 proposed a 20-order system, in which the four previously recognized family-level lineages of thin filamentous cyanobacteria were elevated to the order rank: Leptolyngbyales, Oculatellales, Nodosilineales, and Prochlorotrichales [18].

According to the revised cyanobacterial order and family classification by Strunecký et al., the newly established order Leptolyngbyales Strunecký and Mareš comprises thin filamentous cyanobacteria (<3 μm in width) with simple morphology and facultative sheaths [18]. This order includes families such as Leptolyngbyaceae (containing genera Leptolyngbya and Phormidesmis Turicchia, Ventura, Komárková & Komárek), Trichocoleusaceae (containing only the genus Trichocoleus Anagnostidis), and Neosynechococcaceae (containing the single described genus Neosynechococcus Dvořák, Hindák, Hasler & Hindáková) [18]. Compared with other described cyanobacterial orders, members of Leptolyngbyales are more frequently found in soil and other non-aquatic/terrestrial environments [18]. Filaments of Leptolyngbyaceae typically range from 1.5 to 2.5 μm in width (with a maximum of up to 4.5 μm). Genera such as Leptolyngbya, Phormidesmis, Leptodesmis Raabová, Kovacik & Strunecký, Myxacorys Pietrasiak & Johansen, Alkalinema Vaz et al., and Chamaethrix Dvořák et al. have cylindrical cells that become isodiametric or wider than long after division [19,20,21,22], while Stenomitos Miscoe & Johansen, Onodrimia Jahodárová, Dvorák & Hašler, and Scytolyngbya Song & Li have cells that remain longer than wide [23,24,25].

The newly established genus Pseudoleptolyngbya Hentschke gen. nov. was isolated from freshwater environments in Figueira da Foz, Monchique, and Coimbra, Portugal [26]. This genus is characterized by homocytous, thin, cylindrical trichomes with distinct constrictions at cross-walls, enveloped by delicate colorless sheaths. Morphologically and ecologically indistinguishable from Leptolyngbya, Pseudoleptolyngbya can only be reliably differentiated through molecular characterization. Currently, this genus comprises two described species: Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis (type species) and Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis.

To further explore the diversity of thin filamentous cyanobacteria, this study used a polyphasic approach—incorporating morphological observation, ecological characterization, 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic analysis, and 16S–23S rRNA intergenic spacer (ITS) region analysis—to identify cyanobacterial isolates from subtropical and temperate regions of China. Three cyanobacterial strains, namely, CB-4, GQSK-2, and LHH-2, were successfully purified and cultivated. Therefore, we herein describe the new taxa in the Leptolyngbyaceae: a new genus, Neoleptolyngbya gen. nov., which encompasses two new species: Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis sp. nov. (GQSK-2) and Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis sp. nov. (CB-4); a new species in Pseudoleptolyngbya, Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis sp. nov. (LHH-2).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling, Isolation, and Cultivation

Cyanobacterial strain CB-4 was collected in May 2023 from a shallow freshwater lake in Chanba National Wetland Park, Xi’an City, Shanxi Province, China (34°26′31.61″ N, 108°56′00.24″ E). The strain LHH-2 was isolated from shallow freshwater in Lotus Lake (31°90′60.59″ N, 118°6′60.54″ E) in Wuhan, Hubei province, China, in 2022. The strain GQSK-2 was obtained from plankton sample collected in Gaoqiu Reservoir, Nanyang city (33°0′3.8″ N, 112°31′45.4″ E), Henan province, China, in September 2023. The three studied strains were isolated from a plankton net sample. Unialgal cultures were obtained through serial washing using sterile Pasteur pipettes under 40× magnification (Olympus IX73, Tokyo, Japan). The purified filaments were maintained in BG11 liquid medium at 25 °C under cool-white fluorescent illumination (30 μmol photons m−2 s−1) with a 12:12 h light/dark photoperiod for several weeks. Subsequently, the pure filamentous strains were isolated and transferred to glass tubes containing 10 mL of BG-11 medium. Living cultures of these cyanobacteria are preserved at Wuhan Polytechnic University (Wuhan, China), and the dry material of these strains was stored in the Freshwater Algal Culture Collection of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Wuhan, China).

2.2. Morphological and Ultrastructural Characterization

The morphological characteristics of these three isolated strains were observed using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Microscopic imaging of cultured filaments was performed using a Nikon Eclipse microscope equipped with NIS-Elements imaging software (version 3.2D; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Morphologically related parameters were obtained by measuring the width and length of vegetative cells and filaments in over 100 individuals per strain.

For ultrastructural analysis, the strains CB-4 and GQSK-2 were initially fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4 °C for 3 days. Subsequently, they were rinsed with the same buffer, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h, and rinsed again. Dehydration was carried out using a graded ethanol series (20%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%), followed by embedding in Spurr’s resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate prior to observation under a Hitachi HT-7700 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operating at 80 kV.

2.3. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

DNA extraction of the strains was performed using a modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method [27]. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene and the 16S–23S rRNA ITS region was achieved with primers PA [28] and B23S [29]. The PCR mixture included the following components: 25 μL of Premix Taq, 4 μL of template DNA, 1 μL of each primer, and 19 μL of ddH2O. Amplification was conducted under the following thermal profile: 95 °C for 3 min; 34 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 2 min; with a final 5 min at 72 °C. The resulting products were subsequently purified and recovered with an Omega kit (Omega, Norcross, GA, USA). The sequencing was conducted with an ABI 3730 automated sequencer system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA), and the obtained sequences have been submitted to the NCBI GenBank under accession numbers PV911207, PV911208, PV911209, PV911210, PV911211, PV911212, PV892732, PV892733, and PV892734.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

For phylogenetic placement, the obtained 16S rRNA gene sequences of the isolates were aligned with representative reference strains from Pseudanabaenales, Oculatellales, Nodosilineales, and Leptolyngbyales. Additional sequences were retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database using BLAST (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, accessed on 10 November 2025) algorithms to ensure robust comparative phylogenetic analysis. A total of 233 retrieved 16S rRNA gene sequences (The 16S rRNA gene sequences of all strains used for phylogenetic analysis are listed in Table S1) were subjected to pairwise alignment using MAFFT v7.312 [30] under the auto-selected FFT-NS-I strategy, and the resulting alignment (1084 nucleotides) was subsequently inspected visually using MEGA v7.0.14 [31]. Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using both Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods. The ML analysis was conducted with IQ-TREE v1.6.12 [32], with robustness assessed by 1000 bootstrap replicates. The BI analysis was performed using MrBayes v3.2.6 via the CIPRES Science Gateway platform [33]. For Bayesian analysis, two independent runs were performed, each with four Markov chains, for 5 million generations, with a burn-in fraction of 25% and sampling every 1000 generations. The Bayesian MCMC analyses were run until the average standard deviation of split frequencies fell below 0.01, which was set as the convergence criterion and indicates sufficient sampling of the posterior distribution. The phylogenetic trees were rooted using the outgroup Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421 and viewed by FigTree v1.4.4 [34]. The 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity was calculated as 100 × (1 − p-distance) in MEGA v7.0.14 [31].

2.5. 16S–23S ITS Secondary Structure Analysis

Prediction of the ITS secondary structures (D1–D1′, Box–B, and V3 helices) for the studied and related strains was performed with m-Fold webserver [35] and subsequently redrawn using Adobe Photoshop CS6 Version 13.0.

3. Results

3.1. Molecular and Phylogenetic Analysis

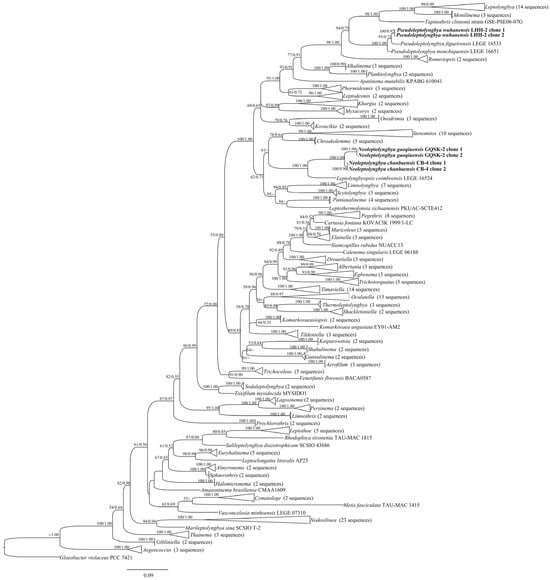

In the order Leptolyngbyales, all genera formed a monophyletic clade with strong support. Strains CB-4 and GQSK-2 clustered into a novel, well-supported clade (designated as Neoleptolyngbya), with a 100% ML bootstrap value and a 1.00 BI posterior probability (Figure 1). Neoleptolyngbya is closely related to Leptolyngbyopsis, a freshwater genus characterized by thin, cylindrical, constricted trichomes, and colorless and thin sheaths. The 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis showed that Neoleptolyngbya shares 93.5–94.2% similarity with Leptolyngbyopsis and <94% similarity with other closely related genera. Within the Neoleptolyngbya clade, the percentage similarity based on 16S rRNA genes between the strains CB-4 and GQSK-2 is 98.2% (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny of cyanobacterial 16S rRNA sequences, including the studied strains. Low-support nodes (ML < 50%; BI < 0.50) are collapsed. The novel filamentous strains characterized herein are shown in bold.

Table 1.

Sequence similarity comparison of the 16S rRNA gene between the studied strains and closely related taxa. Similarity = [1 − (p-distance)] × 100.

The genus Pseudoleptolyngbya also formed a monophyletic clade. Two clone sequences of strain LHH-2 clustered with two Pseudoleptolyngbya species, with a 100% ML bootstrap value and a 1.00 BI posterior probability (Figure 1), and formed a distinct independent branch within the clade. The strain LHH-2 is closely related to Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis. The 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis revealed that LHH-2 shares 94.7% similarity with Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis LEGE 16651 and 95.7% similarity with Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis LEGE 16533 (Table 1).

3.2. Taxonomic Descriptions

Neoleptolyngbya J.X. Chen & F.F. Cai gen. nov.

Diagnosis: Phylogenetically, Neoleptolyngbya is most closely related to Leptolyngbyopsis but can be morphologically distinguished from this sister genus by its wider cell width. Additionally, Neoleptolyngbya exhibits low 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity (Table 1) and distinct 16S–23S ITS secondary structures compared to other genera in Leptolyngbyaceae, supporting its recognition as a novel genus-level lineage.

Description: Thallus blue-green. Filaments solitary or in clusters, straight or curved, without false branching. Sheaths firm, transparent, colorless, tightly adherent to cells. Trichomes isodiametric, slightly constricted at cross-walls. Cells cylindrical, isodiametric, or slightly longer/shorter than wide. Parietal thylakoids. Apical cells elliptical to obtusely rounded. Gas vesicle absent. Reproducing via trichome fragmentation with or without necridia.

Etymology: The genus name “Neoleptolyngbya” refers to its morphological similarity to Leptolyngbya, despite their distant evolutionary relationship.

Type species: Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis.

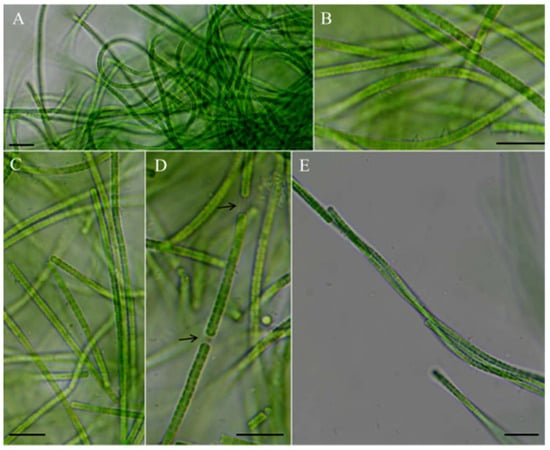

Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis J.X. Chen & F.F. Cai sp. nov. (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Micrographs of Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2: (A) general view of microcolonies; (B,C,E) trichomes without sheath; (D) trichomes with sheath. Arrows indicate sheath. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Diagnosis: Morphologically and phylogenetically, Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis is the most similar to Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis but differs in low 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity, as well as the composition and secondary structure of the ITS region.

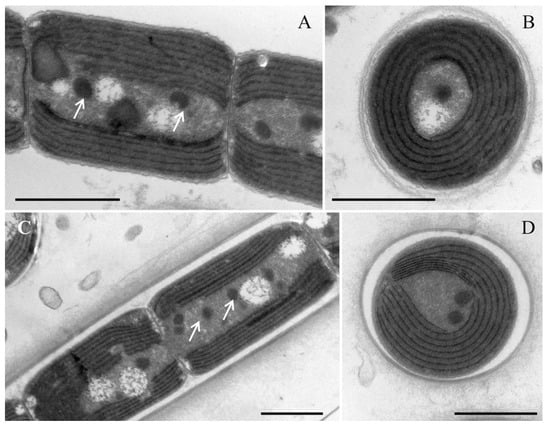

Description: Thallus bright blue-green, floating or attached to the substrate. Filaments solitary or in clusters, straight, or curved. Sheaths often invisible, occasionally with firm, transparent, colorless sheaths. Trichomes with indistinct cross-wall constrictions and an isopolar organization. Cell cylindrical, longer or shorter than wide, 1.3–4.1 μm long, 2.0–3.6 μm wide. Parietal thylakoids (7–8 per cell, Figure 3A,B). Granules occasionally present in the cells (Figure 3A,B). Gas vesicle absent. Necridia present (Figure 2D). Apical cells elliptical to obtusely rounded. Reproduction by trichome fragmentation.

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrograph of the strain Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2 and Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4: (A) longitudinal section of a trichome in Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2; (B) cross section of the cell in Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2; (C) longitudinal section of a filament in Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4; (D) cross section of the cell in Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4. Arrows indicate granule. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Holotype here designated: The dry specimen of strain GQSK-2 was deposited in the Freshwater Algal Herbarium (HBI), Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Science, Wuhan, China, as specimen No. GQSK202208.

Type locality: The strain GQSK-2 was collected in September 2023 by Chen Jiaxin from a water body near Gaoqiu Reservoir—a freshwater reservoir located in Nanyang City, Henan Province, China (coordinates: 33°0′3.8″ N, 112°31′45.4″ E). The strain exhibited a free-floating growth habit on the water surface.

Habitat: Freshwater.

Reference strain: GQSK-2 (Freshwater Algal Herbarium (HBI), Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Science).

Etymology: The name of new species “gaoqiuensis” refers to the locality where the strain was isolated.

Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis J. X. Chen & F. F. Cai sp. nov. (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Micrographs of Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4: (A–D) filaments. Arrows indicate sheath. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Diagnosis: Phylogenetically, Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis forms a well-supported clade with Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis (sister species) within the novel genus Neoleptolyngbya. It differs from N. gaoqiuensis in 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity, 16S–23S ITS secondary structure (D1–D1′ and Box–B helices). The two species, N. chanbaensis and N. gaoqiuensis, exhibit a sequence dissimilarity of 9.3% in the ITS region (Table 2), exceeding the species delineation threshold of >7%.

Table 2.

Percent dissimilarity based on 16S–23S ITS sequence among the studied strains and the closest sister taxa.

Description: Thallus blue-green, or brownish green, free-living in water. Filaments in clusters or solitary, curved, or straight. Sheaths distinct, firm, transparent, colorless, often extending beyond the terminal cells. Trichomes with indistinct cross-wall constrictions and an isopolar morphology. Cell isodiametric, longer or shorter than wide, 1.5–4.0 μm long, 2.1–3.5 μm wide. Parietal thylakoids (7–8 per cell, Figure 3C,D). Granules occasionally present in the cells (Figure 3C,D). Necridia absent. Gas vesicle absent. Apical cells elliptical to obtusely rounded. Reproduction by trichome fragmentation.

Holotype here designated: Dried material of strain CB-4, stored at the Freshwater Algal Herbarium (HBI), Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Wuhan, China), under specimen number CB202210.

Type locality: The strain CB-4 was collected from freshwater in Chanba National Wetland Park, Xi’an City, Shanxi Province (34°26′31.61″ N, 108°94′80.24″ E), China.

Habitat: Freshwater.

Reference strain: CB-4 (Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Wuhan, China), which houses the Freshwater Algal Herbarium).

Etymology: The name of new species “chanbaensis” refers to the locality where the strain was isolated.

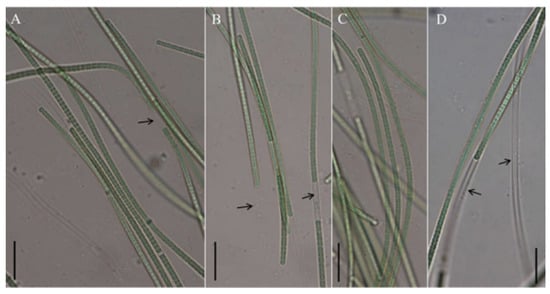

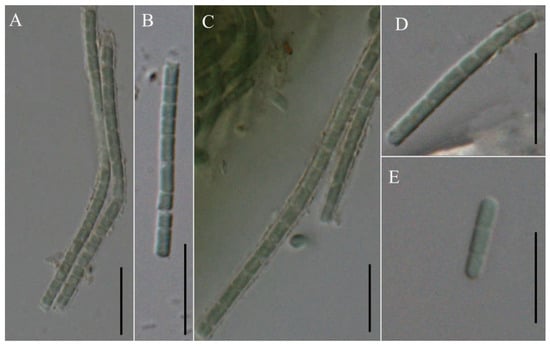

Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis J.X. Chen & F.F. Cai sp. nov. (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Micrographs of Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2: (A–D) single trichome; (E) hormogonium. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Diagnosis: Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis was phylogenetically closest to Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis; however, it differed from this sister species by low 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity and a distinct ITS secondary structure, supporting its recognition as a novel species. In addition, the ITS region of this species shows a notable sequence divergence, exceeding 18% when compared to the other two species (Table 2).

Description: Thallus blue-green. Filaments solitary, straight, unbranched. Sheaths not obvious, mucilaginous diffluent, irregular in outline, colorless, slightly distant to trichomes. Trichomes isopolar, lightly constricted at cross-walls. Cell cylindrical, isodiametric to longer than the width, 1.79–3.40 μm long, 1.84–2.30 μm wide. Apical cells obtuse rounded. Reproduction by trichome fragmentation or hormogonia.

Holotype here designated: Dry material of the strain LHH-2, stored at the HBI, Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Science, Wuhan, China, as specimen No. WH202211.

Type locality: The strain LHH-2 was collected from freshwater in Wuhan City, Hubei province (31°90′60.59″ N, 118°6′60.54″ E), China.

Habitat: Free-floating in freshwater.

Reference strain: LHH-2 (Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Wuhan, China), which houses the Freshwater Algal Herbarium).

Etymology: The term “wuhanensis” refers to the locality where the strain was isolated.

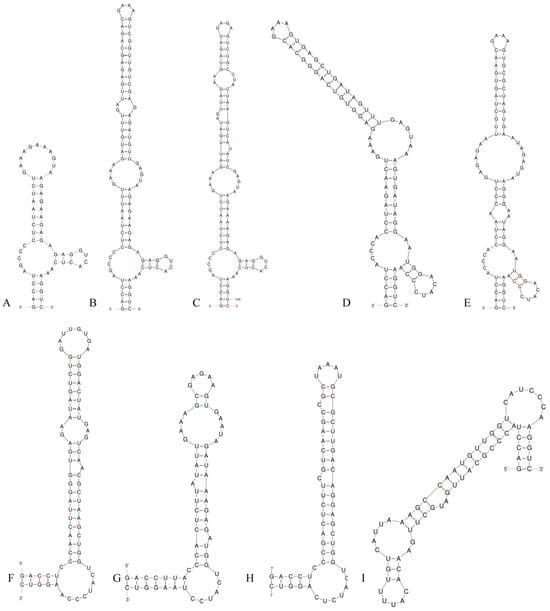

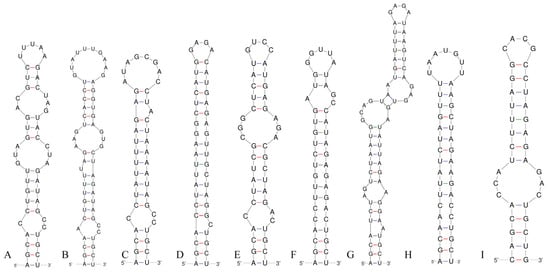

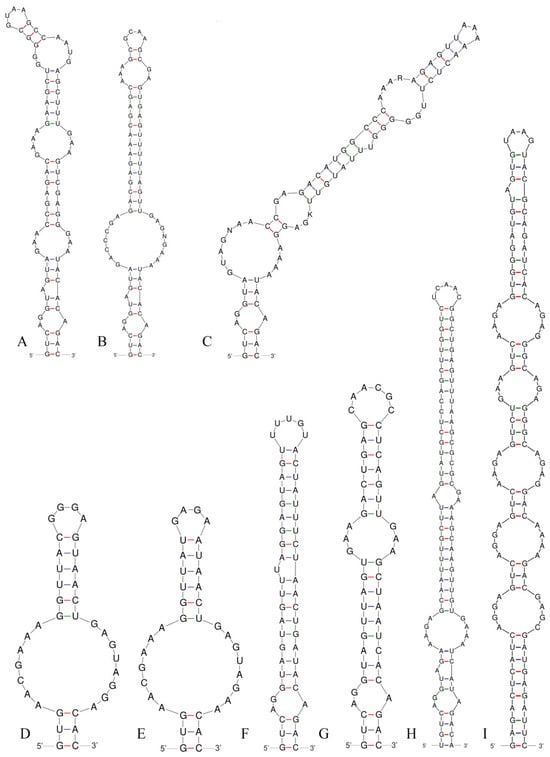

3.3. 16S–23S ITS Region

The 16S–23S ITS sequences of the studied strains were analyzed, and the percent dissimilarity of ITS sequence (including both tRNA genes) between the studied strains and their closely related species was calculated. Three conserved regions (the D1–D1′, Box–B, and the V3 helices) were selected for secondary structure construction.

Analysis of the secondary structure of the D1–D1′ helix revealed unique structural features in Neoleptolyngbya (Figure 6). The D1–D1′ helix of Neoleptolyngbya is unique among these genera, with a stem (5′UGGACAUCCCA′3) originating from the first lateral bulge (5:2) and opposing a sequence of five free residues (5′ACCCA′3) (Figure 6D,E). Beyond the first lateral bulge, the D1–D1′ helix structures of the two Neoleptolyngbya species exhibit entirely different configurations. In Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4, the first lateral bulge leads through a 9 bp stem and a 4:6 bp bilateral bulge, terminating in a 15 bp stem region (Figure 6D). In contrast, Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2 features a 1:2 bp bilateral bulge and a 7:8 bp bilateral bulge after the first lateral bulge, followed by a 12 bp stem region (Figure 6E). The closely related genus Leptolyngbyopsis has a 1:8 bp bilateral bulge, followed by an unpaired 3′ nucleotide, and a 2:3 bp bilateral bulge, which is closed by an 8 bp terminal loop (5′GAUUGUGA′3) (Figure 6F). The Box–B helix in Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2 comprises a 4 bp (AGCA) basal stem, a 1:2 nucleotide asymmetry, a 3:3 bilateral bulge, and ends in a 4 bp terminal loop (GUCC) (Figure 7E). The Box–B helix of Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4 also consists of a 4 bp (AGCA) helix in the base of the stem, followed by an unpaired single nucleotide on the 3′ side, and ends in a 4 bp terminal loop (GAGA) (Figure 7D). In contrast, the Box–B structure of the closely related genus Leptolyngbyopsis exhibits variations in both length and structural features. Specifically, it is characterized by an extended 15 bp basal stem, which extends into a 1:2 bp bilateral bulge and culminates in a 5 bp terminal loop (GGUUA) (Figure 7F). The V3 helix comparison between Neoleptolyngbya and closely related genus Leptolyngbyopsis revealed significant structural variations (Figure 8). The V3 helix in Neoleptolyngbya comprises a 3 bp basal stem, a 7:8 bp bilateral bulge, and ends in a 4 bp terminal loop (Figure 8D,E). In contrast, the V3 structure of Leptolyngbyopsis showed a 3 bp basal stem, a 2:1 bp bilateral bulge, an unpaired single nucleotide on the 5′ side, and a 5 bp terminal loop (Figure 8F). The V3 helix structures of the two Neoleptolyngbya species exhibit a similar pattern, differing only in their nucleotide sequences. The percent dissimilarity of ITS between Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2 and Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4 is 9.3% (Table 2).

Figure 6.

D1–D1′ helices of the 16S–23S ITS for the studied strains and comparison taxa: (A) Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2; (B) Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis LEGE 16533; (C) Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis LEGE 16651; (D) Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4; (E) Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2; (F) Leptolyngbyopsis coimbrensis LEGE 16524; (G) Limnolyngbya circumcreta CHAB4449; (H) Chroakolemma opacum strain 701; (I) Stenomitos rutilans HA7619-LM2.

Figure 7.

Box–B helices of the 16S–23S ITS for the studied strains and comparison taxa: (A) Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2; (B) Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis LEGE 16533; (C) Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis LEGE 16651; (D) Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4; (E) Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2; (F) Leptolyngbyopsis coimbrensis LEGE 16524; (G) Limnolyngbya circumcreta CHAB4449; (H) Chroakolemma opacum strain 701; (I) Stenomitos rutilans HA7619-LM2.

Figure 8.

V3 helices of the 16S–23S ITS for the studied strains and comparison taxa: (A) Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2; (B) Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis LEGE 16533; (C) Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis LEGE 16651; (D) Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis CB-4; (E) Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2; (F) Leptolyngbyopsis coimbrensis LEGE 16524; (G) Chroakolemma opacum strain 701; (H) Stenomitos rutilans HA7619-LM2; (I) Limnolyngbya circumcreta CHAB4449.

The analysis of the ITS secondary structures of Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2 in comparison to the other two Pseudoleptolyngbya species revealed unique features for Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2 (Figure 6A–C). The D1–D1′ helix of three Pseudoleptolyngbya species has a stem (5′GAGGUCACUC3′) originating from the first lateral bulge (5:3) and opposing a sequence of five free residues (5′AGCCC3′), and followed by a large terminal loop containing 11 bp bases in Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2 (but two bilateral bulges in Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis LEGE 16533, and two bilateral bulges and two unpaired single nucleotides in Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis LEGE 16651). The Box–B helices in Pseudoleptolyngbya were conserved at the basal stem regions while demonstrating divergence in both sequences and structural features. The Box–B helix of Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2 has three bilateral bulges of 1:2, 3:3 and 2:3 nt, and the terminal loop contains 5 bp bases (UUUAA) (Figure 7A). The Box–B helix of Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis LEGE 16533 has a 1:2 bilateral bulge, an unpaired single nucleotide on the 5′ side, a 3:3 bilateral bulge, and a large terminal loop containing 10 bp bases (Figure 7B). The Box–B helix of Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis LEGE 16651 consists a 1:2 bilateral bulge, an unpaired 3′ nucleotide, and an 8 bp terminal loop (Figure 6C). The V3 helices of Pseudoleptolyngbya varied in sequence, structure, and length. The V3 helix of Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2 was completely different from that of the other two Pseudoleptolyngbya species (Figure 8A–C). The base stem of Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2 was made up of a 3 bp helix, a 2:1 bp bilateral bulge, an unpaired single nucleotide on the 5′ side, three bilateral bulges of 3:3, 4:3 and 2:4 nt, and a 4 bp terminal loop (GUAA) (Figure 8A). The V3 helix of Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis LEGE 16533 has a 2:1 bilateral bulge, an unpaired 5′ nucleotide, a 7:8 bilateral bulge, a 3:2 bilateral bulge, and a 4 bp terminal loop (GCAA) (Figure 8B). The V3 helix of Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis LEGE 16651 consists of four bilateral bulges of 2:1, 7:4, 2:3, and 4:3 nt, an unpaired single nucleotide on the 3′ side, and a terminal loop containing 3 bp bases (AAA) (Figure 8C). The percent dissimilarity of ITS of Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis LHH-2 to the other two Pseudoleptolyngbya species is in the range of 18.8–21.8% (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Morphological characteristics alone are insufficient to delineate genus and species boundaries in certain cyanobacterial taxa, particularly the thin filamentous cyanobacteria. Thus, molecular approaches have become the primary method for cyanobacterial identification [17,36]. In modern classification systems, the description of a novel cyanobacterial genus requires evidence of a well-supported monophyletic phylogenetic position, along with clear evolutionary discontinuity from the nearest sister clade [15,17,26,37,38,39].

Using a polyphasic taxonomic approach, we describe strains GQSK-2 and CB-4 as two new species, Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis and Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis, within the novel genus Neoleptolyngbya (family Leptolyngbyaceae). Phylogenetically, Neoleptolyngbya is closely related to Leptolyngbyopsis (with strong support; Figure 1) within Leptolyngbyaceae. Leptolyngbyopsis is a cryptic genus with diverse filament morphologies; Neoleptolyngbya can be morphologically distinguished from Leptolyngbyopsis only by its wider cell width: Leptolyngbyopsis has a cell width of 1.7–2 μm, while Neoleptolyngbya has a cell width of 2.0–3.6 μm (Table 3). Additionally, Neoleptolyngbya can also be distinguished from Leptolyngbyopsis and other closely related genera by its high 16S rRNA p-distance (above the 5.8% threshold), which falls below the 95% genus delineation threshold proposed by Yarza et al. [40]. These results further support the establishment of Neoleptolyngbya as a new genus. Variations in the length of conserved domains in the 16S–23S rDNA ITS region and differences in ITS secondary structures (e.g., D1–D1′, Box–B, and V3 helices) have been used as autapomorphies to characterize and support novel cryptic genera or species [17,26,38,39,41,42,43,44]. Comparative analyses of predicted ITS secondary structures further confirms genus-level divergence among phylogenetically related taxa. The D1–D1′ helix, which was considered to be highly conservative, was significantly different between Neoleptolyngbya and related taxa. The two A bases and the stem-loop region (UGGACAUCCCA) in opposition to the first lateral bulge can serve as a diagnostic feature distinguishing Neoleptolyngbya from other genera within the family. Additionally, the large 7:8 bp bilateral bulge in the V3 helix of Neoleptolyngbya is a unique feature not observed in other closely related genera of Leptolyngbyaceae.

Table 3.

Comparison of the characteristics of the studied species with closely related species.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity among Neoleptolyngbya species does not meet the 98.7% species delineation threshold defined by Yarza et al. [40], providing molecular evidence for their taxonomic distinction. Moreover, the D1–D1′ and Box–B helices of Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis exhibit pronounced differences from those of N. chanbaensis. The V3 helix structures of the two Neoleptolyngbya species display similar configurations while differing in their nucleotide sequences. Furthermore, the percent dissimilarity in the 16S–23S ITS region is valuable for cyanobacterial species delimitation. The 16S–23S ITS region shows a 9.3% dissimilarity between Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis GQSK-2 and N. chanbaensis CB-4, exceeding >7% threshold for species separation [17,21,41,45,46].

Pseudoleptolyngbya is a newly established genus presently known to contain two species, namely, Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis and Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis, both isolated from artificial freshwater fountains in Portugal [26]. The new Pseudoleptolyngbya species, Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis, here described was also found living in a freshwater habitat similar to the previously described species. From a genetic perspective, Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis is clearly distinct from its sister species: it exhibits a >4.4% difference in 16S rRNA gene sequence and a >18% difference in the 16S–23S rRNA ITS region compared to the other Pseudoleptolyngbya species. Moreover, when the new species in this study is compared with its closely related species Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis, the difference in 16S rRNA is greater than 5.3%, and the difference in ITS is greater than 21%.

The ITS secondary structure exhibits distinct structural differences among the three species. Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis shares a similar basal lateral bulge in the D1–D1′ helix with the other two Pseudoleptolyngbya species. However, the structures posterior to the base are entirely different, manifested in the following details: Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis has no bilateral bulge in the central region and only has a 11 bp terminal loop, whereas Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis possesses two bilateral bulges and a 4 bp terminal loop, and Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis exhibits two bilateral bulges, one unpaired single nucleotide, one 2 bp unilateral bulge, and a 4 bp terminal loop. Additionally, the Box–B helix of the three species exhibit differences, apart from the shared 1:2 bp bilateral bulge at the base, Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis possesses two additional bilateral bulges and a 5 bp terminal loop. Pseudoleptolyngbya figueirensis has one unilateral bulge, an unpaired single nucleotide on the 5′ side, and a 10 bp terminal loop, while Pseudoleptolyngbya monchiquensis contains one unpaired single nucleotide on the 3′ side and a 8 bp terminal loop. The V3 helix structures of the three species are completely distinct, with each species representing a distinct type. Despite morphological similarities between Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis and the other Pseudoleptolyngbya species, genetic analyses of the 16S rRNA and ITS regions confirm its status as a novel taxon.

The descriptions of all novel taxa were conducted using a polyphasic approach, encompassing morphological characterization and comparisons with phylogenetically related taxa, genetic analyses based on 16S rRNA and 16S–23S rRNA, 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis, and ecological characteristics. In summary, the strains GQSK-2 and CB-4 were described as two new species, Neoleptolyngbya gaoqiuensis sp. nov. and Neoleptolyngbya chanbaensis sp. nov., in a new genus, Neoleptolyngbya gen. nov.; the strain LHH-2 was described as one new species, Pseudoleptolyngbya wuhanensis sp. nov. Significant gaps remain in our understanding of global cyanobacterial diversity, with numerous species awaiting discovery and formal description. The taxonomy of cyanobacteria will undoubtedly be refined in the future. China, with its vast territory, is one of the world’s most biodiverse countries, and a large number of cyanobacterial resources remain unexplored. Given the substantial proportion of undiscovered cyanobacterial diversity, we will continue to conduct systematic surveys across various regions to identify novel taxa, thereby enriching our knowledge of cyanobacterial biodiversity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms14010072/s1, Table S1: 16S rRNA gene for phylogeny.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C. and X.L.; methodology, F.C.; software, F.C. and S.L.; formal analysis, F.C. and J.C.; investigation, F.C.; data curation, F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C.; writing—review and editing, F.C. and R.L.; visualization, F.C.; funding acquisition, F.C. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant No. 42177230.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Whitton, B.A.; Potts, M. Introduction to the Cyanobacteria. In The Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time; Whitton, B.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, T.W.; Reinhard, C.T.; Planavsky, N.J. The Rise of Oxygen in Earth’s Early Ocean and Atmosphere. Nature 2014, 506, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demay, J.; Bernard, C.; Reinhardt, A.; Marie, B. Natural Products from Cyanobacteria: Focus on Beneficial Activities. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvořák, P.; Hašler, P.; Casamatta, D.A.; Poulíčková, A. Underestimated Cyanobacterial Diversity: Trends and Perspectives of Research in Tropical Environments. Fottea 2021, 21, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, J.A.; Berthold, D.E.; Lefler, F.W.; Huang, I.S.; Laughinghouse, H.D., IV. Floridanema gen. nov. (Aerosakkonemataceae, Aerosakkonematales ord. nov., Cyanobacteria) from Benthic Tropical and Subtropical Fresh Waters, with the Description of Four New Species. J. Phycol. 2025, 61, 91–107, Erratum in J. Phycol. 2025, 61, 393. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, S.A.; Kelly, L.T.; Bouma-Gregson, K.; Humbert, J.F.; Laughinghouse, H.D., IV; Lazorchak, J.; McAllister, T.G.; McQueen, A.; Pokrzywinski, K.; Puddick, J.; et al. Toxic Benthic Freshwater Cyanobacterial Proliferations: Challenges and Solutions for Enhancing Knowledge and Improving Monitoring and Mitigation. Freshw. Biol. 2020, 65, 1824–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.; Wolfschlaeger, I.; Geist, J.; Fastner, J.; Schmalz, C.W.; Raeder, U. Occurrence, Distribution and Toxins of Benthic Cyanobacteria in German Lakes. Toxics 2023, 11, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefler, F.W.; Berthold, D.E.; Laughinghouse, H.D., IV. CyanoSeq: A Database of Cyanobacterial 16S rRNA Sequences with Curated Taxonomy. J. Phycol. 2023, 59, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, R.; Kang, J.; Hii, K.S.; Mohamed, H.F.; Xu, X.; Luo, Z. Okeanomitos corallinicola gen. and sp. nov. (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria), a New Toxic Marine Heterocyte-forming Cyanobacterium from a Coral Reef. J. Phycol. 2024, 60, 908–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkerson, R.B., III; Perkerson, E.A.; Casamatta, D.A. Phylogenetic Examination of the Cyanobacterial Genera Geitlerinema and Limnothrix (Pseudanabaenaceae) using 16S rDNA Gene Sequence Data. Algol. Stud. 2010, 134, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunecký, O.; Elster, J.; Komárek, J. Molecular Clock Evidence for Survival of Antarctic Cyanobacteria (Oscillatoriales, Phormidium autumnale) from Paleozoic Times. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 82, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciuto, K.; Moschin, E.; Moro, I. Cryptic cyanobacterial diversity in the Giant Cave (Trieste, Italy): The new genus Timaviella (Leptolyngbyaceae). Cryptogam. Algol. 2017, 38, 285–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostidis, K.; Komárek, J. Modern Approach to the Classification System of the Cyanophytes 3: Oscillatoriales. Algol. Stud. Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. 1988, 50–53, 327–472. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota 2. In Teil: Oscillatoriales; Elsevier/Spektrum: Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; p. 759. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, L.; Kaštovský, J.; Komárek, J. System of Cyanoprokaryotes (Cyanobacteria)—State in 2004. Algol. Stud. Arch. Hydrobiol. Suppl. 2005, 117, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, J.; Kaštovský, J.; Mareš, J.; Johansen, J.R. Taxonomic Classification of Cyanoprokaryotes (Cyanobacterial Genera) 2014, Using a Polyphasic Approach. Preslia 2014, 86, 295–335. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, T.; Johansen, J.R.; Nicole, P.; Markéta, B.; Martin, M.P. Revision of the Synechococcales (Cyanobacteria) through Recognition of Four Families including Oculatellaceae fam. nov. and Trichocoleaceae fam. nov. and Six New Genera Containing 14 Species. Phytotaxa 2018, 365, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunecký, O.; Ivanova, A.P.; Mareš, J. An Updated Classification of Cyanobacterial Orders and Families Based on Phylogenomic and Polyphasic Analysis. J. Phycol. 2023, 59, 12–51, Erratum in J. Phycol. 2023, 59, 635. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpy.13355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, M.G.; Genuário, D.B.; Andreote, A.P.; Malone, C.F.; Sant’Anna, C.L.; Barbiero, L.; Fiore, M.F. Pantanalinema gen. nov. and Alkalinema gen. nov.: Novel Pseudanabaenacean Genera (Cyanobacteria) Isolated from Saline-Alkaline Lakes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvořák, P.; Hašler, P.; Pitelková, P.; Tabáková, P.; Casamatta, D.A.; Poulíčková, A. A New Cyanobacterium from the Everglades, Florida—Chamaethrix gen. nov. Fottea 2017, 17, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrasiak, N.; Osorio-Santos, K.; Shalygin, S.; Martin, M.P.; Johansen, J.R. When is a Lineage a Species? A Case Study in Myxacorys gen. nov. (Synechococcales: Cyanobacteria) with the Description of Two New Species from the Americas. J. Phycol. 2019, 55, 976–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabová, L.; Kovácik, L.; Elster, J.; Strunecký, O. Review of the Genus Phormidesmis (Cyanobacteria) Based on Environmental, Morphological, and Molecular Data with Description of a New Genus Leptodesmis. Phytotaxa 2019, 395, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miscoe, L.H.; Johansen, J.; Vaccarino, M.A.; Pietrasiak, N.; Sherwood, A.R. The Diatom Flora and Cyanobacteria from Caves on Kauai, Hawaii. II. Novel Cyanobacteria from Caves on Kauai, Hawaii. In Bibliotheca Phycologica; Schweizerbart Science Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016; Volume 120, pp. 1–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jahodářová, E.; Dvořák, P.; Hašler, P.; Poulíčková, A. Revealing Hidden Diversity among Tropical Cyanobacteria: The New Genus Onodrimia (Synechococcales, Cyanobacteria) Described Using the Polyphasic Approach. Phytotaxa 2017, 326, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Jiang, Y.; Li, R. Scytolyngbya timoleontis, gen. et sp. nov. (Leptolyngbyaceae, Cyanobacteria): A Novel False Branching Cyanobacteria from China. Phytotaxa 2015, 224, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschke, G.S.; Morais, J.; de Oliveira, F.L.; Silva, R.; Cruz, P.; Vasconcelos, V. Taxonomic Updates in the Family Leptolyngbyaceae (Leptolyngbyales, Cyanobacteria): The Description of Pseudoleptolyngbya gen. nov, Leptolyngbyopsis gen. nov., and the Replacement of Arthronema. Eur. J. Phycol. 2025, 60, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.D. Cetyltrimethyl Ammonium Bromide (CTAB) DNA Miniprep for Plant DNA Isolation. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, 2009, pdb.prot5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, U.; Rogall, T.; Blöcker, H.; Emde, M.; Böttger, E.C. Isolation and direct complete nucleotide determination of entire genes. Characterization of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 7843–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkelis, S.; Rajaniemi, P.; Vardaka, E.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Lanaras, T.; Sivonen, K. Limnothrix redekei (Van Goor) Meffert (cyanobacteria) strains from Lake Kastoria, Greece form a separate phylogenetic group. Microb. Ecol. 2005, 49, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L.T.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. W-IQ-TREE: A Fast Online Phylogenetic Tool for Maximum Likelihood Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W232–W235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Schwartz, T.; Pickett, B.E.; He, S.; Klem, E.B.; Scheuermann, R.H.; Passarotti, M.; Kaufman, S.; O’Leary, M.A. A RESTful API for Access to Phylogenetic Tools via the CIPRES Science Gateway. Evol. Bioinform. 2015, 11, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. FigTree, version 1.4.4. Tree Figure Drawing Tool. Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2018. Available online: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Zuker, M. Mfold Web Server for Nucleic Acid Folding and Hybridization Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3406–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komárek, J. Several Problems of the Polyphasic Approach in the Modern Cyanobacterial System. Hydrobiologia 2018, 811, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Yu, G.; Li, R. Description of two new species of Pseudoaliinostoc (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria) from China based on the polyphasic approach. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2022, 40, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawong, W.; Pongcharoen, P.; Nishimura, T.; Saijuntha, W. Siamcapillus rubidus gen. et sp. nov. (Oculatellaceae), a Novel Filamentous Cyanobacterium from Thailand Based on Molecular and Morphological Analyses. Phytotaxa 2022, 558, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Li, R. Gansulinema gen. nov. and Komarkovaeasiopsis gen. nov.: Novel Oculatellacean Genera (Cyanobacteria) Isolated from Desert Soils and Hot Spring. J. Phycol. 2024, 60, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarza, P.; Yilmaz, P.; Pruesse, E.; Glöckner, F.O.; Ludwig, W.; Schleifer, K.H.; Whitman, W.B.; Euzéby, J.; Amann, R.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Uniting the Classification of Cultured and Uncultured Bacteria and Archaea Using 16S rRNA Gene Sequences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareš, J.; Johansen, J.R.; Hauer, T.; Zima, J.; Ventura, S.; Cuzman, O.; Tiribilli, B.; Kaštovský, J. Taxonomic Resolution of the Genus Cyanothece (Chroococcales, Cyanobacteria), with a Treatment on Gloeothece and Three New Genera, Crocosphaera, Rippkaea, and Zehria. J. Phycol. 2019, 55, 578–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, C.F.D.S.; Genuário, D.B.; Vaz, M.G.M.V.; Fiore, M.F.; Sant’Anna, C.L. Monilinema gen. nov., a Homocytous Genus (Cyanobacteria, Leptolyngbyaceae) from Saline–Alkaline Lakes of Pantanal Wetlands, Brazil. J. Phycol. 2021, 57, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, D.E.; Lefler, F.W.; Laughinghouse, H.D., IV. Untangling Filamentous Marine Cyanobacterial Diversity from the Coast of South Florida with the Description of Vermifilaceae fam. nov. and Three New Genera: Leptochromothrix gen. nov., Ophiophycus gen. nov., and Vermifilum gen. nov. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 160, 107010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Maruthanayagam, V.; Achari, A.; Pramanik, A.; Jaisankar, P.; Mukherjee, J. Aerofilum fasciculatum gen. nov., sp. nov. (Oculatellaceae) and Euryhalinema pallustris sp. nov. (Prochlorotrichaceae) Isolated from an Indian Mangrove Forest. Phytotaxa 2021, 522, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, P.; Mikhailyuk, T.; Emrich, D.; Baumann, K.; Dultz, S.; Büdel, B. Shifting Boundaries: Ecological and Geographical Range Extension Based on Three New Species in the Cyanobacterial Genera Cyanocohniella, Oculatella, and Aliterella. J. Phycol. 2020, 56, 1216–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusko, B.M.; Johansen, J.R.; Mehda, S.; Perona, E.; Muñoz-Martín, M.Á. Four Novel Species of Kastovskya (Coleofasciculaceae, Cyanobacteriota) from Three Continents with a Taxonomic Revision of Symplocastrum. Diversity 2024, 16, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.