The Dual Role of Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Context-Dependent Framework

Abstract

1. The Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

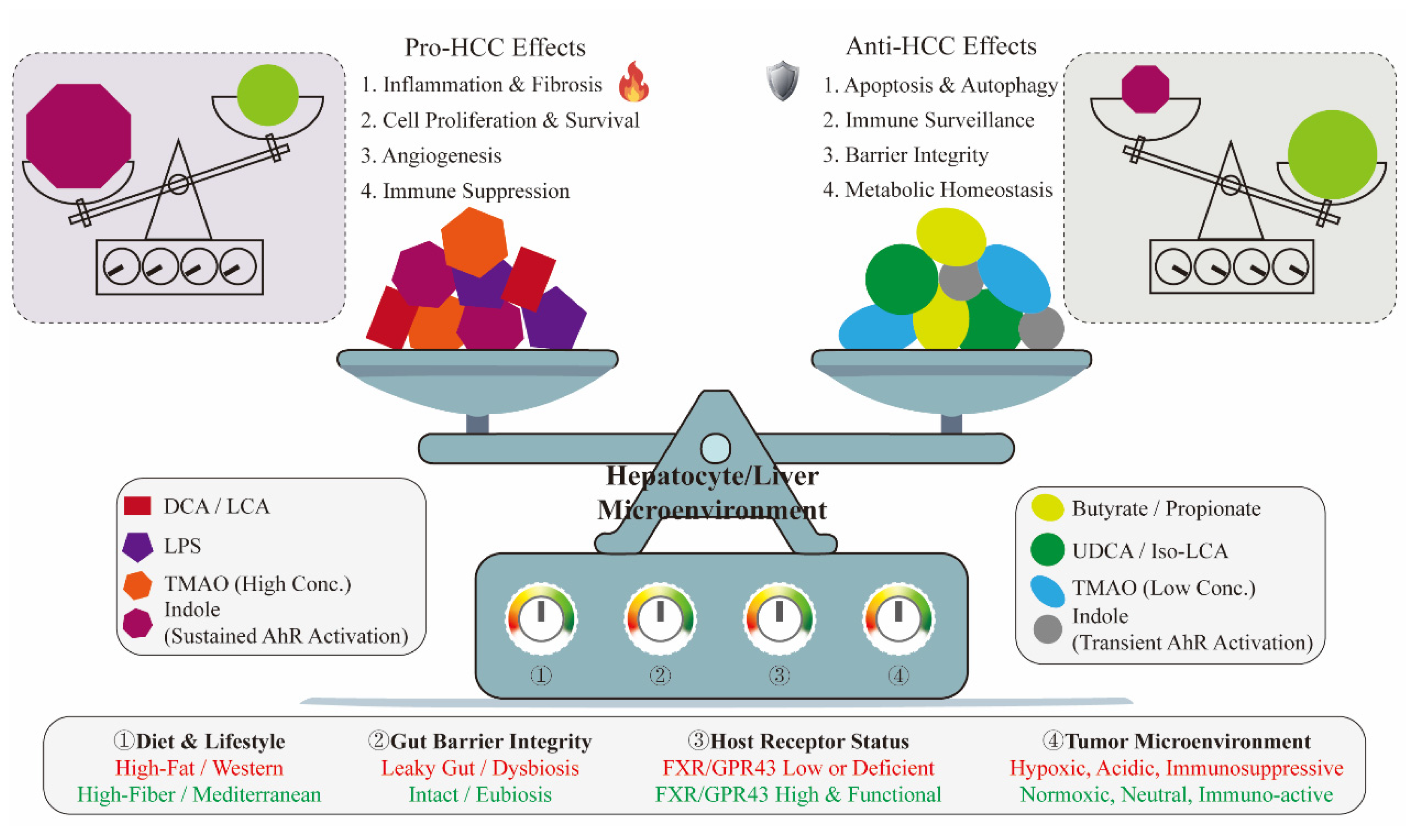

2. Association Between Gut Microbiota and HCC

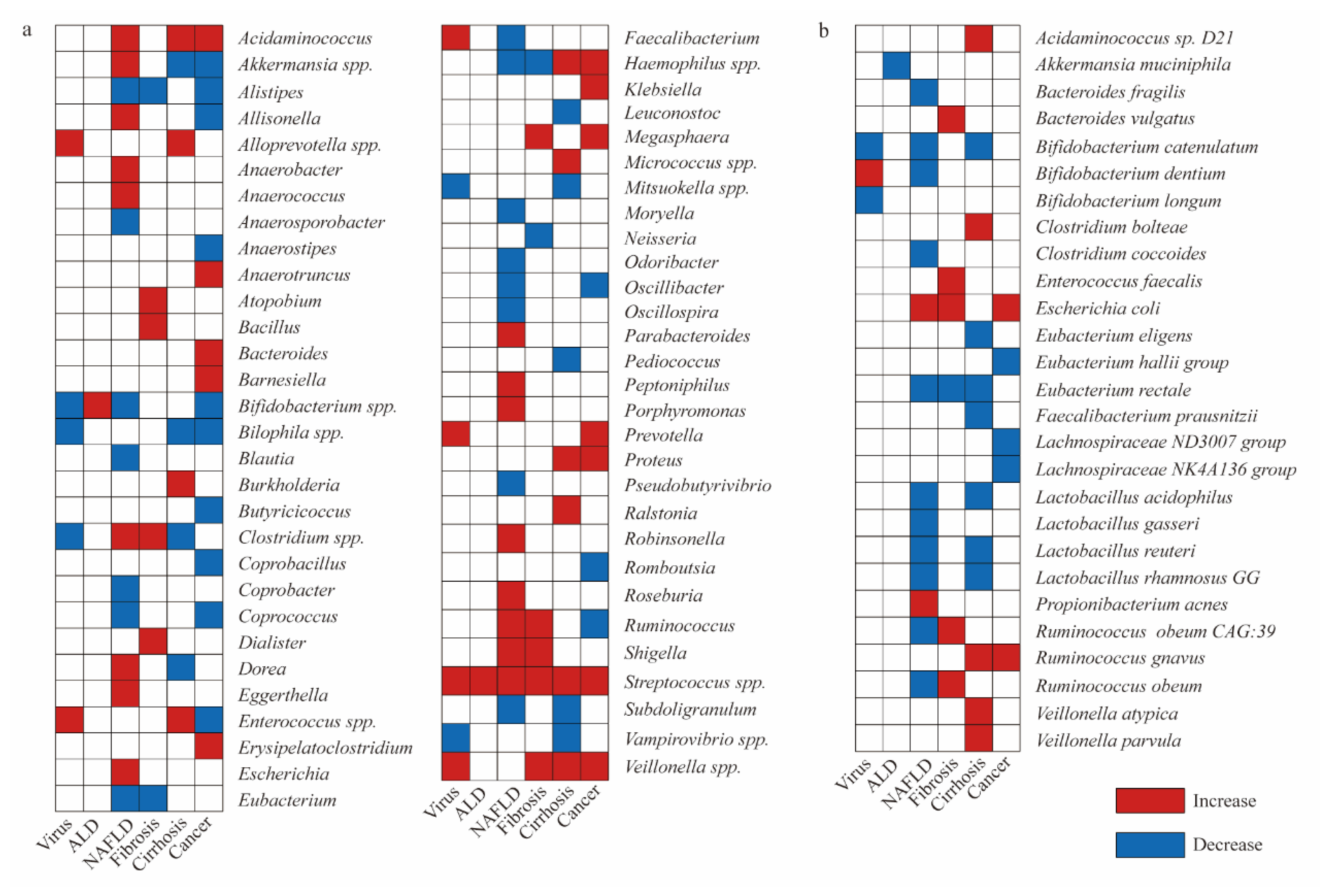

2.1. Landscape of HCC Microbiota

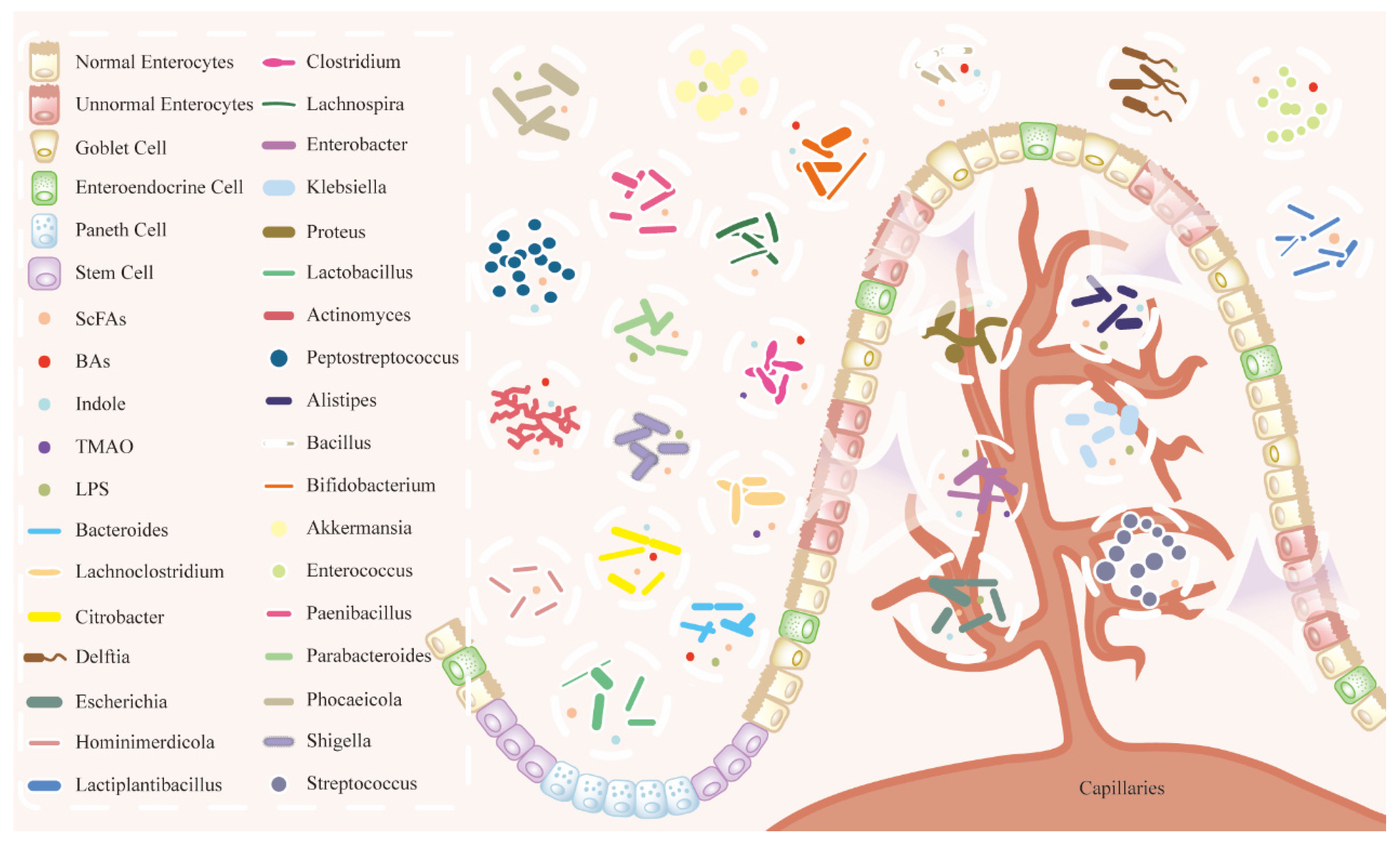

2.2. Interaction Between Gut Microbiota and HCC

Gut–Liver Axis

2.3. HCC-Promoting Bacterial Species

2.4. HCC-Protecting Bacterial Species

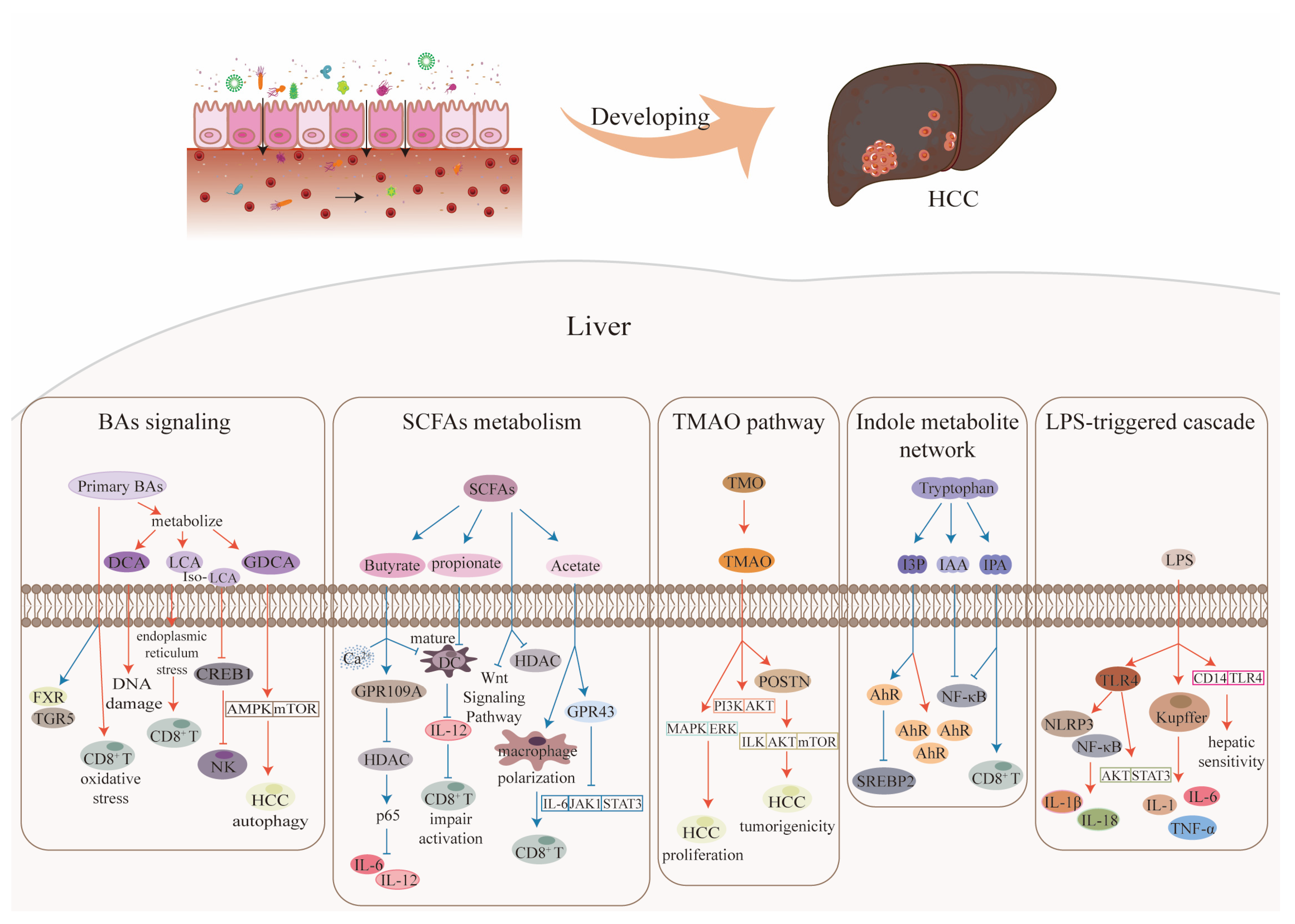

3. Gut Microbiota Metabolites and Their Effects on HCC

3.1. Bile Acids

3.2. Short-Chain Fatty Acids

3.3. Trimethylamine N-Oxide

3.4. Indole Metabolites

3.5. Lipopolysaccharide

3.6. Role of Diet in Gut Microbiota–Host Interactions

3.7. Beyond Single Molecules: The Synergistic and Antagonistic Network of Microbial Metabolites

4. Potential Roles of Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites in HCC Diagnosis and Treatment

4.1. Role in HCC Diagnosis

4.2. Role in HCC Treatment

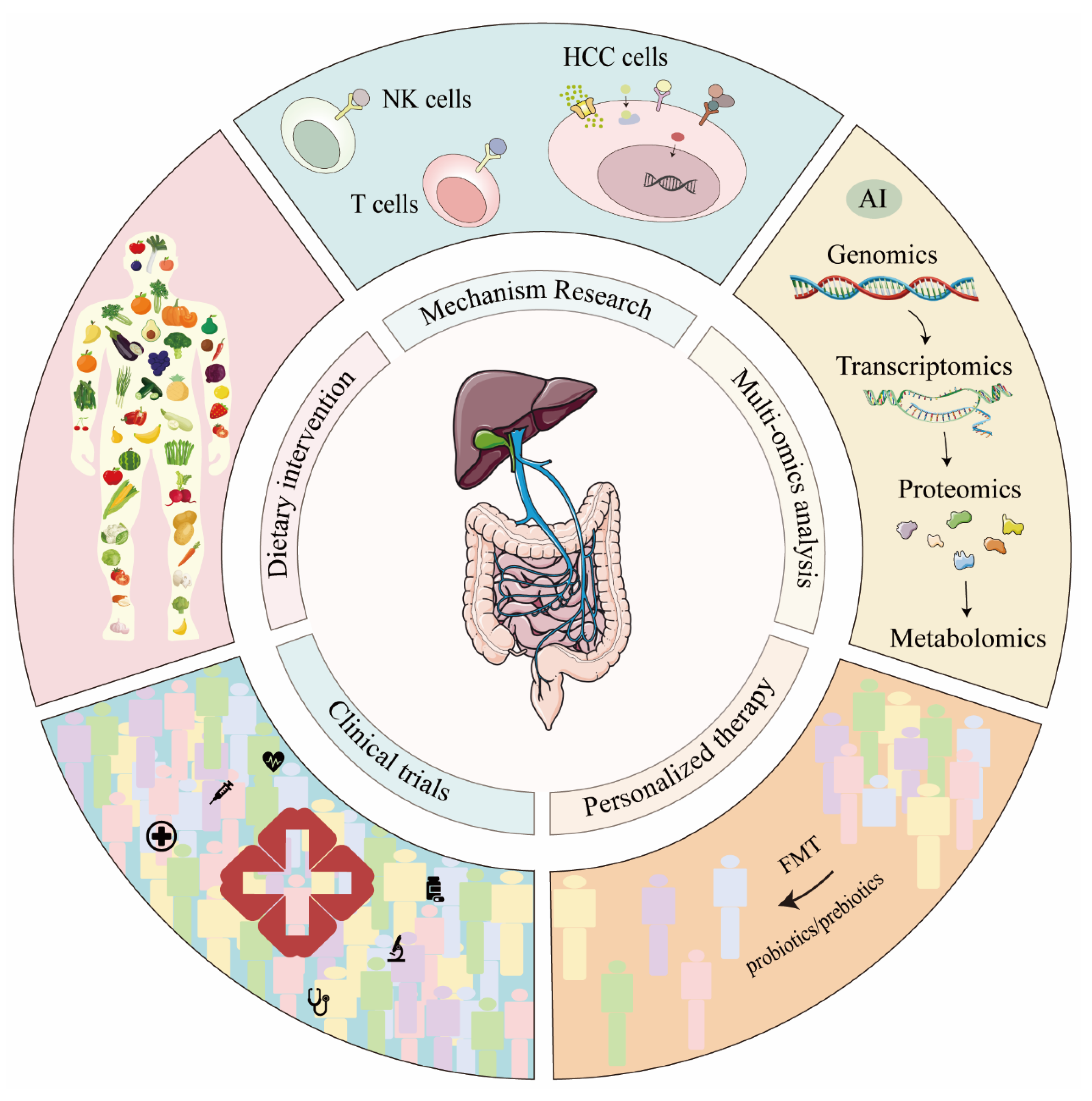

5. Discussion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rumgay, H.; Arnold, M.; Ferlay, J.; Lesi, O.; Cabasag, C.J.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; McGlynn, K.A.; Soerjomataram, I. Global Burden of Primary Liver Cancer in 2020 and Predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Ma, W. Biomarker Discovery in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) for Personalized Treatment and Enhanced Prognosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2024, 79, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Y.-T.; Zhang, C.; Wu, J.; Lu, P.; Xu, L.; Yuan, H.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Wang, N. Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Therapeutic Options in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Ni, Z.; Shi, W.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Yu, Z.; Gao, X.; et al. Nitrate Ameliorates Alcohol-Induced Cognitive Impairment via Oral Microbiota. J. Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.; Li, X.; Ji, L.; Chen, G.; Han, Z.; Su, L.; Wu, D. Characterization and Comparison of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Acute Pancreatitis by Metagenomics and Culturomics. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Guo, J.; Shi, W.; Tong, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Xiang, Z.; Qin, C. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals the Community Composition of the Microbiome in Different Segments of the Digestive Tract in Donkeys and Cows: Implications for Microbiome Research. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Shi, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Qin, C.; Su, L. Comparative Analysis of Gut Microbiomes in Laboratory Chinchillas, Ferrets, and Marmots: Implications for Pathogen Infection Research. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Shi, W.; Guo, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, L.; Su, L.; Qin, C. Comparative Metagenomics and Metabolomes Reveals Abnormal Metabolism Activity Is Associated with Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, S.C.; Kumar, N.; Anonye, B.O.; Almeida, A.; Viciani, E.; Stares, M.D.; Dunn, M.; Mkandawire, T.T.; Zhu, A.; Shao, Y.; et al. A Human Gut Bacterial Genome and Culture Collection for Improved Metagenomic Analyses. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, N.; Du, M.-X.; Sun, Y.-T.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y.-J.; Li, D.-H.; Yu, H.-Y.; Song, Y.; Bai, B.-B.; et al. The Mouse Gut Microbial Biobank Expands the Coverage of Cultured Bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Du, M.-X.; Abuduaini, R.; Yu, H.-Y.; Li, D.-H.; Wang, Y.-J.; Zhou, N.; Jiang, M.-Z.; Niu, P.-X.; Han, S.-S.; et al. Enlightening the Taxonomy Darkness of Human Gut Microbiomes with a Cultured Biobank. Microbiome 2021, 9, 119, Erratum in Microbiome 2022, 10, 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-022-01370-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.; Abuduaini, R.; Du, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, H.; Zhou, N.; Xin, Y.; Wu, L.; et al. The Monkey Microbial Biobank Brings Previously Uncultivated Bioresources for Nonhuman Primate and Human Gut Microbiomes. mLife 2022, 1, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, M.; Shi, W.; Li, X.; Xiang, Z.; Su, L. Clostridium lamae sp. nov., a Novel Bacterium Isolated from the Fresh Feces of Alpaca. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2024, 117, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Li, X.; Shi, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Su, L.; Qin, C. Lactococcus intestinalis sp. nov., a New Lactic Acid Bacterium Isolated from Intestinal Contents in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2023, 116, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, P.; Gong, L.; Shi, W.; Xiang, Z.; Li, M.; Su, L.; Qin, C. Bacteroides rhinocerotis sp. nov., Isolated from the Fresh Feces of Rhinoceros in Beijing Zoo. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zhu, H.; Sun, P.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Gao, H.; Xiang, Z.; Qin, C. Species Diversity in Penicillium and Acaulium from Herbivore Dung in China, and Description of Acaulium stericum sp. nov. Mycol. Prog. 2021, 20, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zhu, H.; Niu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Du, X.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C. Phylogeny and Taxonomic Revision of Kernia and Acaulium. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10302, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71842-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zhu, H.; Guo, Y.; Du, X.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C. Lecanicillium coprophilum (Cordycipitaceae, Hypocreales), a New Species of Fungus from the Feces of Marmota monax in China. Phytotaxa 2019, 387, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C.; Devkota, S.; Ghosh, T.S. Gut Microbiome: A Biomedical Revolution. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 830–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Du, M.-X.; Xie, L.-S.; Wang, W.-Z.; Chen, B.-S.; Yun, C.-Y.; Sun, X.-W.; Luo, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, K.; et al. Gut Commensal Christensenella Minuta Modulates Host Metabolism via Acylated Secondary Bile Acids. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhari, A.; Cheng, T.N.H.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Kochar, B.; Burke, K.E.; Shannon, K.; Lau, H.; Xavier, R.J.; Smillie, C.S. Discovery of Disease-Adapted Bacterial Lineages in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1147–1162.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmink, B.A.; Khan, M.A.W.; Hermann, A.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Wargo, J.A. The Microbiome, Cancer, and Cancer Therapy. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Z.; Wang, F.; Bhosle, A.; Dong, D.; Mehta, R.; Ghazi, A.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Rinott, E.; Ma, S.; et al. Strain-Specific Gut Microbial Signatures in Type 2 Diabetes Identified in a Cross-Cohort Analysis of 8117 Metagenomes. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2265–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, T.R.; Debelius, J.W.; Thron, T.; Janssen, S.; Shastri, G.G.; Ilhan, Z.E.; Challis, C.; Schretter, C.E.; Rocha, S.; Gradinaru, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell 2016, 167, 1469–1480.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakruddin, M.; Shishir, M.A.; Oyshe, I.I.; Amin, S.M.T.; Hossain, A.; Sarna, I.J.; Jerin, N.; Mitra, D.K. Microbial Architects of Malignancy: Exploring the Gut Microbiome’s Influence in Cancer Initiation and Progression. Cancer Plus 2023, 5, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Debelius, J.; Brenner, D.A.; Karin, M.; Loomba, R.; Schnabl, B.; Knight, R. The Gut-Liver Axis and the Intersection with the Microbiome. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 397–411, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 785. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-018-0031-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, B. Understanding Gut Dysbiosis for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Diagnosis and Treatment. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 35, 1006–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cai, C.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Z. Gut Microbiota-Mediated Gut-Liver Axis: A Breakthrough Point for Understanding and Treating Liver Cancer. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, 350–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Liang, W.; Cai, Y.; Wong, C.C.; Wang, J.; Wang, N.; Lau, H.C.-H.; Jiao, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Gut–Liver Translocation of Pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; D’Angelo, S. Gut Microbiota Modulation Through Mediterranean Diet Foods: Implications for Human Health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.M.; Mohs, A.; Gui, W.; Galvez, E.J.C.; Candels, L.S.; Hoenicke, L.; Muthukumarasamy, U.; Holland, C.H.; Elfers, C.; Kilic, K.; et al. Imbalanced Gut Microbiota Fuels Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development by Shaping the Hepatic Inflammatory Microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Cao, C.; Chen, D.; Huang, X.; Li, C.; Xu, H.; Lai, H.; Chen, H.; et al. Roles of the Gut Microbiota in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: From the Gut Dysbiosis to the Intratumoral Microbiota. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Ren, Z.; Gao, X.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, J.; Lu, H.; Yin, S.; Ji, J.; Zhou, L.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Microbiome and Host Transcriptome Reveals Correlations between Gut Microbiota and Clinical Outcomes in HBV-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Yang, Y. The Gut Microbiome and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Implications for Early Diagnostic Biomarkers and Novel Therapies. Liver Cancer 2022, 11, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Mande, S.S. Host-Microbiome Interactions: Gut-Liver Axis and Its Connection with Other Organs. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Zhang, X.; Cai, J. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Interplay between Microbiota, Barrier Function and Lymphatic System. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2387800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut Microbiota, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Coker, O.O.; Chu, E.S.; Fu, K.; Lau, H.C.H.; Wang, Y.-X.; Chan, A.W.H.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Dietary Cholesterol Drives Fatty Liver-Associated Liver Cancer by Modulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. Gut 2021, 70, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wen, L.; Bao, Y.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, T.; Zhang, J.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Gut Flora Disequilibrium Promotes the Initiation of Liver Cancer by Modulating Tryptophan Metabolism and Up-Regulating SREBP2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2203894119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Q.; Miao, C.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Fan, M.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Bile Acid Metabolism Dysregulation Associates with Cancer Cachexia: Roles of Liver and Gut Microbiome. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 1553–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Wei, H.; Liang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ji, F.; Ho-Kwan Cheung, A.; Wong, N.; et al. Bifidobacterium pseudolongum-Generated Acetate Suppresses Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Wan, W.-H.; Lu, J.; Kong, D.; Jin, Y.; You, W.; Sun, H.; Mu, X.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Regulate Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells in HCC. Hepatology 2023, 77, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhu, P.; Shi, L.; Gao, N.; Li, Y.; Shu, C.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y.; He, J.; Guo, D.; et al. Bifidobacterium Longum Promotes Postoperative Liver Function Recovery in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 131–144.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, R.; Kamachi, F.; Nakamura, M.; Yamazaki, S.; Kamiya, T.; Takasugi, M.; Cheng, Y.; Nonaka, Y.; Yukawa-Muto, Y.; Thuy, L.T.T.; et al. Gasdermin D-Mediated Release of IL-33 from Senescent Hepatic Stellate Cells Promotes Obesity-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabl7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Wei, R.; Chen, W.; Rajani, C.; Hernandez, B.Y.; Alegado, R.; Dong, B.; Li, D.; et al. Distinctly Altered Gut Microbiota in the Progression of Liver Disease. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 19355–19366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-L.; Yu, L.-X.; Yang, W.; Tang, L.; Lin, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhai, B.; Tan, Y.-X.; Shan, L.; Liu, Q.; et al. Profound Impact of Gut Homeostasis on Chemically-Induced pro-Tumorigenic Inflammation and Hepatocarcinogenesis in Rats. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, A.; Fu, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, W.; Lv, W. Gut Microbiota Changes and Biological Mechanism in Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Transarterial Chemoembolization Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1002589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, S.; Loo, T.M.; Atarashi, K.; Kanda, H.; Sato, S.; Oyadomari, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Oshima, K.; Morita, H.; Hattori, M.; et al. Obesity-Induced Gut Microbial Metabolite Promotes Liver Cancer through Senescence Secretome. Nature 2013, 499, 97–101, Erratum in Nature 2014, 506, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Han, M.; Heinrich, B.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Sandhu, M.; Agdashian, D.; Terabe, M.; Berzofsky, J.A.; Fako, V.; et al. Gut Microbiome-Mediated Bile Acid Metabolism Regulates Liver Cancer via NKT Cells. Science 2018, 360, eaan5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, T.M.; Kamachi, F.; Watanabe, Y.; Yoshimoto, S.; Kanda, H.; Arai, Y.; Nakajima-Takagi, Y.; Iwama, A.; Koga, T.; Sugimoto, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota Promotes Obesity-Associated Liver Cancer through PGE2-Mediated Suppression of Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponziani, F.R.; Bhoori, S.; Castelli, C.; Putignani, L.; Rivoltini, L.; Del Chierico, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Morelli, D.; Paroni Sterbini, F.; Petito, V.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Associated with Gut Microbiota Profile and Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2019, 69, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinato, T.; Anuntakarun, S.; Satthawiwat, N.; Chuaypen, N.; Tangkijvanich, P. Distinct Alterations of Gut Microbiota between Viral- and Non-Viral-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, J.; Jin, C.; Yang, J.; Zheng, C.; Chen, K.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Y.; Bo, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Association of Gut Microbiome and Primary Liver Cancer: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization and Case-Control Study. Liver Int. 2023, 43, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Li, A.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, L.; Yu, Z.; Lu, H.; Xie, H.; Chen, X.; Shao, L.; Zhang, R.; et al. Gut Microbiome Analysis as a Tool towards Targeted Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut 2019, 68, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Li, J.; Chen, B.; Zhao, J.; Hu, L.; Huang, K.; Chen, Q.; Yao, J.; Lin, G.; Bao, L.; et al. The Enrichment of the Gut Microbiota Lachnoclostridium Is Associated with the Presence of Intratumoral Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1289753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grąt, M.; Wronka, K.M.; Krasnodębski, M.; Masior, Ł.; Lewandowski, Z.; Kosińska, I.; Grąt, K.; Stypułkowski, J.; Rejowski, S.; Wasilewicz, M.; et al. Profile of Gut Microbiota Associated with the Presence of Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 1687–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Huang, R.; Zhou, H.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Cao, P.; Zhong, K.; Ge, M.; Chen, X.; Hou, B.; et al. Analysis of the Relationship Between the Degree of Dysbiosis in Gut Microbiota and Prognosis at Different Stages of Primary Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.-N.; Chen, T.; Ren, C.-H.; Li, X.; Liu, G.-X. Relationship between Intestinal Microbial Dysbiosis and Primary Liver Cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2019, 18, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-Y.; Tan, X.-Y.; Li, Q.-J.; Liao, G.-C.; Fang, A.-P.; Zhang, D.-M.; Chen, P.-Y.; Wang, X.-Y.; Luo, Y.; Long, J.-A.; et al. Trimethylamine N-Oxide, a Gut Microbiota-Dependent Metabolite of Choline, Is Positively Associated with the Risk of Primary Liver Cancer: A Case-Control Study. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 15, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, G.; Pang, Z.; Ran, N.; Gu, Y.; Guan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zuo, X.; Pan, H.; Zheng, J.; et al. Liver Cirrhosis Contributes to the Disorder of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 4232–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behary, J.; Amorim, N.; Jiang, X.-T.; Raposo, A.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Ibrahim, R.; Chu, F.; Stephens, C.; Jebeili, H.; et al. Gut Microbiota Impact on the Peripheral Immune Response in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, B.O.; Bäckhed, F. Signals from the Gut Microbiota to Distant Organs in Physiology and Disease. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, X.; Cai, L.; Cai, X. Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiome in Elderly Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Mei, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Zou, B.; Dai, J.; Mao, K.; Li, Q.; Guo, Q.; et al. Dysregulation of Gut Microbiota Stimulates NETs-Driven HCC Intrahepatic Metastasis: Therapeutic Implications of Healthy Faecal Microbiota Transplantation. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2476561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, L.; Tang, W.; Li, D.; Ma, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Dong, L.; Shen, X.; et al. Hepatic NOD2 Promotes Hepatocarcinogenesis via a RIP2-Mediated Proinflammatory Response and a Novel Nuclear Autophagy-Mediated DNA Damage Mechanism. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, B.; Zheng, Q.; Li, H.; Meng, X.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, L. A Review of Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Tumor Progression and Cancer Therapy. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2207366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, I.; Vujovic, A.; Barac, A.; Djelic, M.; Korac, M.; Radovanovic Spurnic, A.; Gmizic, I.; Stevanovic, O.; Djordjevic, V.; Lekic, N.; et al. Gut-Liver Axis, Gut Microbiota, and Its Modulation in the Management of Liver Diseases: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S. Alcohol, Liver Disease and the Gut Microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neag, M.A.; Mitre, A.O.; Catinean, A.; Buzoianu, A.D. Overview of the Microbiota in the Gut-Liver Axis in Viral B and C Hepatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 7446–7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Vigliotti, C.; Witjes, J.; Le, P.; Holleboom, A.G.; Verheij, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Clément, K. Gut Microbiota and Human NAFLD: Disentangling Microbial Signatures from Metabolic Disorders. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, Z.; Gérard, P. The Links between the Gut Microbiome and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, T.G.; Kim, S.M.; Caussy, C.; Fu, T.; Guo, J.; Bassirian, S.; Singh, S.; Madamba, E.V.; Bettencourt, R.; Richards, L.; et al. A Universal Gut-Microbiome-Derived Signature Predicts Cirrhosis. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 878–888.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Kuang, Z.; Li, C.; Guo, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Hu, Y.; Song, B.; Jiang, Z.; Ge, Z.; et al. Gut Akkermansia muciniphila Ameliorates Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease by Regulating the Metabolism of L-Aspartate via Gut-Liver Axis. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1927633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zheng, X.; Ji, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Guo, L.; Ye, K.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Y.-J.; et al. The Carotenoid Torularhodin Alleviates NAFLD by Promoting Akkermanisa muniniphila-Mediated Adenosylcobalamin Metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguri, N.; Miyoshi, J.; Nishinarita, Y.; Wada, H.; Nemoto, N.; Hibi, N.; Kawamura, N.; Miyoshi, S.; Lee, S.T.M.; Matsuura, M.; et al. Akkermansia muciniphila in the Small Intestine Improves Liver Fibrosis in a Murine Liver Cirrhosis Model. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; You, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, X.; He, X.; Liu, J.; Ma, N. Improving Fatty Liver Hemorrhagic Syndrome in Laying Hens through Gut Microbiota and Oxylipin Metabolism by Bacteroides fragilis: A Potential Involvement of Arachidonic Acid. Anim. Nutr. 2025, 20, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Lan, R.; Qiao, L.; Lin, X.; Hu, D.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Zhou, J.; Ren, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Bacteroides vulgatus Ameliorates Lipid Metabolic Disorders and Modulates Gut Microbial Composition in Hyperlipidemic Rats. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0251722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Shi, D.; Lv, L.; Gu, S.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, A.; Hu, X.; Guo, F.; et al. Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum LI09 and Bifidobacterium catenulatum LI10 Attenuate D-Galactosamine-Induced Liver Injury by Modifying the Gut Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lv, L.; Yan, R.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, L.; et al. Bifidobacterium longum R0175 Protects Rats against D-Galactosamine-Induced Acute Liver Failure. mSphere 2020, 5, e00791-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizo, G.H.; Rampelotto, P.H. The Impact of Probiotic Bifidobacterium on Liver Diseases and the Microbiota. Life 2024, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Choi, Y.-J.; Wedamulla, N.E.; Tang, Y.; Han, K.I.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Kim, E.-K. Heat-Killed Enterococcus faecalis EF-2001 Attenuate Lipid Accumulation in Diet-Induced Obese (DIO) Mice by Activating AMPK Signaling in Liver. Foods 2022, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, B.G.; Duan, Y.; Schnabl, B. Immune Response of an Oral Enterococcus faecalis Phage Cocktail in a Mouse Model of Ethanol-Induced Liver Disease. Viruses 2022, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-H.; Woo, K.-J.; Hong, J.; Han, K.-I.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, T.-J. Heat-Killed Enterococcus faecalis Inhibit FL83B Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and High Fat Diet-Induced Fatty Liver Damage in Rats by Activating Lipolysis through the Regulation the AMPK Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullahalli, K.; Dailey, K.G.; Hasegawa, Y.; Torres, E.; Suzuki, M.; Zhang, H.; Threadgill, D.W.; Navarro, V.M.; Waldor, M.K. Genetic and Immune Determinants of E. coli Liver Abscess Formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2310053120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-H.; Lee, Y.; Song, E.-J.; Lee, D.; Jang, S.-Y.; Byeon, H.R.; Hong, M.-G.; Lee, S.-N.; Kim, H.-J.; Seo, J.-G.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Prevents Hepatic Damage in a Mouse Model of NASH Induced by a High-Fructose High-Fat Diet. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1123547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.Y.; Shin, M.J.; Youn, G.S.; Yoon, S.J.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.S.; Gupta, H.; Han, S.H.; Kim, B.K.; Lee, D.Y.; et al. Lactobacillus Attenuates Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Lowering Cholesterol and Steatosis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2021, 27, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Lykov, N.; Luo, X.; Wang, H.; Du, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Tzeng, C. Protective Effects of Lactobacillus gasseri against High-Cholesterol Diet-Induced Fatty Liver and Regulation of Host Gene Expression Profiles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werlinger, P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Gu, M.; Cho, J.-H.; Cheng, J.; Suh, J.-W. Lactobacillus reuteri MJM60668 Prevent Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through Anti-Adipogenesis and Anti-Inflammatory Pathway. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-J.; Park, H.J.; Cha, M.G.; Park, E.; Won, S.-M.; Ganesan, R.; Gupta, H.; Gebru, Y.A.; Sharma, S.P.; Lee, S.B.; et al. The Lactobacillus as a Probiotic: Focusing on Liver Diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sung, C.Y.J.; Lee, N.; Ni, Y.; Pihlajamäki, J.; Panagiotou, G.; El-Nezami, H. Probiotics Modulated Gut Microbiota Suppresses Hepatocellular Carcinoma Growth in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1306–E1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arellano-García, L.I.; Milton-Laskibar, I.; Martínez, J.A.; Arán-González, M.; Portillo, M.P. Comparative Effects of Viable Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Its Heat-Inactivated Paraprobiotic in the Prevention of High-Fat High-Fructose Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Rats. Biofactors 2025, 51, e2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Shi, M.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, B.; Li, Q.; Yu, L.; Lu, Z. Splenectomy Ameliorates Liver Cirrhosis by Restoring the Gut Microbiota Balance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.Y.L. Bile Acid Metabolism and Signaling. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Xie, G.; Jia, W. Bile Acid-Microbiota Crosstalk in Gastrointestinal Inflammation and Carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Jin, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Y. Disrupting Bile Acid Metabolism by Suppressing Fxr Causes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Induced by YAP Activation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ding, M.; Ji, L.; Yao, J.; Guo, Y.; Yan, W.; Yu, S.; Shen, Q.; Huang, M.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Bile Acids Promote the Development of HCC by Activating Inflammasome. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Suo, C.; Gu, X.; Shen, S.; Lin, K.; Zhu, C.; Yan, K.; Bian, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; et al. AKR1D1 Suppresses Liver Cancer Progression by Promoting Bile Acid Metabolism-Mediated NK Cell Cytotoxicity. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 1103–1118.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varanasi, S.K.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Johnson, M.A.; Miller, C.M.; Ganguly, S.; Lande, K.; LaPorta, M.A.; Hoffmann, F.A.; Mann, T.H.; et al. Bile Acid Synthesis Impedes Tumor-Specific T Cell Responses during Liver Cancer. Science 2025, 387, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, T.H.; Arifuzzaman, M.; Parkhurst, C.N.; Miranda, I.C.; Zhang, B.; Hu, E.; Kashyap, S.; Letourneau, J.; Jin, W.-B.; Fu, Y.; et al. Host Metabolism Balances Microbial Regulation of Bile Acid Signalling. Nature 2025, 638, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Coulter, S.; Yoshihara, E.; Oh, T.G.; Fang, S.; Cayabyab, F.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Leblanc, M.; Liu, S.; et al. FXR Regulates Intestinal Cancer Stem Cell Proliferation. Cell 2019, 176, 1098–1112.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Cai, J.; Gonzalez, F.J. The Role of Farnesoid X Receptor in Metabolic Diseases, and Gastrointestinal and Liver Cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Kang, D.-J.; Hylemon, P.B. Bile Salt Biotransformations by Human Intestinal Bacteria. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Harris, S.C.; Bhowmik, S.; Kang, D.-J.; Hylemon, P.B. Consequences of Bile Salt Biotransformations by Intestinal Bacteria. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 22–39, Erratum in Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 262. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1191920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, J.C.; Flynn, C.R. Bile Acids, Their Receptors, and the Gut Microbiota. Physiology 2021, 36, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.M.; Gayer, C.P. The Pathophysiology of Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) in the GI Tract: Inflammation, Barrier Function and Innate Immunity. Cells 2021, 10, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, L.; Lu, X.; Zheng, W.; Shi, J.; Yu, S.; Feng, H.; Yu, Z. Bile Acids and Liver Cancer: Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Prospects. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.-Y.; Chen, S.-M.; Pan, C.-X.; Li, Y. FXR: Structures, Biology, and Drug Development for NASH and Fibrosis Diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022, 43, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Wu, L.; Zang, Y. Development and Validation of a Metabolic-Related Prognostic Model for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2021, 9, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Yang, W.-X.; Cai, J.-Y.; Wang, F.-F.; You, C.-G. Comprehensive Molecular Characteristics of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Based on Multi-Omics Analysis. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, E.; Wang, Y.; Sun, S.; Yang, Y.; Tian, T.; Ju, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Notoginsenoside Ft1 Acts as a TGR5 Agonist but FXR Antagonist to Alleviate High Fat Diet-Induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Fan, M.; Huang, W. Pleiotropic Roles of FXR in Liver and Colorectal Cancers. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2022, 543, 111543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, E.R.; Lam, Y.K.; Uhlig, H.H. Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Linking Diet, the Microbiome and Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Mitra, P.; Lahiri, A.; Das, T.; Sarkar, J.; Paul, S.; Chakrabarti, P. Butyrate Limits Inflammatory Macrophage Niche in NASH. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBrearty, N.; Arzumanyan, A.; Bichenkov, E.; Merali, S.; Merali, C.; Feitelson, M. Short Chain Fatty Acids Delay the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in HBx Transgenic Mice. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.P.; Denu, J.M. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Activate Acetyltransferase P300. Elife 2021, 10, e72171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; Ozawa, K.; Inoue, D.; Imamura, T.; Kimura, K.; Maeda, T.; Terasawa, K.; Kashihara, D.; Hirano, K.; Tani, T.; et al. The Gut Microbiota Suppresses Insulin-Mediated Fat Accumulation via the Short-Chain Fatty Acid Receptor GPR43. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boedtkjer, E.; Pedersen, S.F. The Acidic Tumor Microenvironment as a Driver of Cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2020, 82, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yang, L.; Liang, Y.; Liu, F.; Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Yuan, L.; Feng, F.B. Thetaiotaomicron-Derived Acetic Acid Modulate Immune Microenvironment and Tumor Growth in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2297846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.M. Immunomodulatory Mechanisms of Lactobacilli. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Chen, G.; Guo, Q.; Duan, Y.; Feng, H.; Xia, Q. Gut Microbial Metabolite Butyrate Improves Anticancer Therapy by Regulating Intracellular Calcium Homeostasis. Hepatology 2023, 78, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papandreou, C.; Moré, M.; Bellamine, A. Trimethylamine N-Oxide in Relation to Cardiometabolic Health—Cause or Effect? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, E.S.; Lloyd, T.S.; Tessem, J.S. The Accumulation and Molecular Effects of Trimethylamine N-Oxide on Metabolic Tissues: It’s Not All Bad. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Basnet, R.; Zhen, C.; Ma, S.; Guo, X.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Promotes the Proliferation and Migration of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell through the MAPK Pathway. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Rong, X.; Pan, M.; Wang, T.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, C. Integrated Analysis Reveals the Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Promotes Inflammatory Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Upregulating POSTN. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 840171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Tian, X.; Li, H.; et al. Bie Jia Jian Pill Ameliorates BDL-Induced Cholestatic Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats by Regulating Intestinal Microbial Composition and TMAO-Mediated PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Mimila, P.; Villamil-Ramírez, H.; Li, X.S.; Shih, D.M.; Hui, S.T.; Ocampo-Medina, E.; López-Contreras, B.; Morán-Ramos, S.; Olivares-Arevalo, M.; Grandini-Rosales, P.; et al. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Levels Are Associated with NASH in Obese Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2021, 47, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Weng, J.; Yan, J.; Zeng, Y.-H.; Hao, Q.-Y.; Sheng, H.-F.; Hua, Y.-Q. Puerarin Alleviates Atherosclerosis via the Inhibition of Prevotella copri and Its Trimethylamine Production. Gut 2024, 73, 1934–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Li, G.; Zheng, Q.; Gu, X.; Shi, Q.; Su, Y.; Chu, Q.; Yuan, X.; Bao, Z.; Lu, J.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1304–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Mu, C.; Farzi, A.; Zhu, W. Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platten, M.; Nollen, E.A.A.; Röhrig, U.F.; Fallarino, F.; Opitz, C.A. Tryptophan Metabolism as a Common Therapeutic Target in Cancer, Neurodegeneration and Beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chen, H.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, W. Indole-3-Acetic Acid Alleviates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice via Attenuation of Hepatic Lipogenesis, and Oxidative and Inflammatory Stress. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.-H.; Xin, F.-Z.; Xue, Y.; Hu, Z.; Han, Y.; Ma, F.; Zhou, D.; Liu, X.-L.; Cui, A.; Liu, Z.; et al. Indole-3-Propionic Acid Inhibits Gut Dysbiosis and Endotoxin Leakage to Attenuate Steatohepatitis in Rats. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, D.; Wang, Q.; Qi, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, J.; Lin, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, W.; Fan, L.; et al. Microbial Metabolite Enhances Immunotherapy Efficacy by Modulating T Cell Stemness in Pan-Cancer. Cell 2024, 187, 1651–1665.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik, A.; Somarribas Patterson, L.F.; Öztürk, S.; Mohapatra, S.R.; Panitz, V.; Secker, P.F.; Pfänder, P.; Loth, S.; Salem, H.; Prentzell, M.T.; et al. IL4I1 Is a Metabolic Immune Checkpoint That Activates the AHR and Promotes Tumor Progression. Cell 2020, 182, 1252–1270.e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezaveh, K.; Shinde, R.S.; Klötgen, A.; Halaby, M.J.; Lamorte, S.; Ciudad, M.T.; Quevedo, R.; Neufeld, L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Jin, R.; et al. Tryptophan-Derived Microbial Metabolites Activate the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Tumor-Associated Macrophages to Suppress Anti-Tumor Immunity. Immunity 2022, 55, 324–340.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothhammer, V.; Quintana, F.J. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: An Environmental Sensor Integrating Immune Responses in Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswaran, N.; Garcia, R.; Lafita-Navarro, M.C.; Hao, Y.-H.; Perez-Castro, L.; Nogueira, P.A.S.; Solmonson, A.; Mender, I.; Kilgore, J.A.; Fang, S.; et al. Tryptophan Fuels MYC-Dependent Liver Tumorigenesis through Indole 3-Pyruvate Synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Geng, W.; Sun, H.; Liu, C.; Huang, F.; Cao, J.; Xia, L.; Zhao, H.; Zhai, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Integrative Metabolomic Characterisation Identifies Altered Portal Vein Serum Metabolome Contributing to Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut 2022, 71, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.C.; Sakurai, T.; Kaneko, H.; Horigome, A.; Mitsuyama, E.; Nakajima, A.; Katoh, T.; Sakanaka, M.; Abe, T.; Xiao, J.-Z.; et al. Human Gut-Associated Bifidobacterium Species Salvage Exogenous Indole, a Uremic Toxin Precursor, to Synthesize Indole-3-Lactic Acid via Tryptophan. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2347728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.H.; Devi, S.; Kwon, G.H.; Gupta, H.; Jeong, J.-J.; Sharma, S.P.; Won, S.-M.; Oh, K.-K.; Yoon, S.J.; Park, H.J.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Indole Compounds Attenuate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease by Improving Fat Metabolism and Inflammation. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2307568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisseleva, T.; Brenner, D. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Liver Fibrosis and Its Regression. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenkel, O.; Tacke, F. Liver Macrophages in Tissue Homeostasis and Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, B.; Cao, H.; Hu, Y.; Gong, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Peng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, X. Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in HCC Cell Progression. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wei, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Sun, M.; Lai, W.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; et al. STING Signaling Sensing of DRP1-Dependent mtDNA Release in Kupffer Cells Contributes to Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. Redox Biol. 2022, 54, 102367, Erratum in Redox Biol. 2023, 62, 102664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, H.; Osawa, Y.; Matsuda, M.; Tsunoda, T.; Yanagida, K.; Hishikawa, D.; Okawara, M.; Sakamoto, Y.; Shimagaki, T.; Tsutsui, Y.; et al. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Promotes Tumor Development and Liver Fibrosis in Mouse Model of Congestive Hepatopathy. Hepatology 2022, 76, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Kaji, K.; Kitade, M.; Kubo, T.; Furukawa, M.; Saikawa, S.; Shimozato, N.; Sato, S.; Seki, K.; Kawaratani, H.; et al. Exogenous Administration of Low-Dose Lipopolysaccharide Potentiates Liver Fibrosis in a Choline-Deficient l-Amino-Acid-Defined Diet-Induced Murine Steatohepatitis Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Collazo, E.; del Fresno, C. Pathophysiology of Endotoxin Tolerance: Mechanisms and Clinical Consequences. Crit. Care 2013, 17, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplutz, M.; Levikova, M.; Lüscher-Firzlaff, J.; Lesina, M.; Algül, H.; Lüscher, B.; Huber, M. Endotoxin Tolerance in Mast Cells, Its Consequences for IgE-Mediated Signalling, and the Effects of BCL3 Deficiency. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, M.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, H. ATG2B Upregulated in LPS-Stimulated BMSCs-Derived Exosomes Attenuates Septic Liver Injury by Inhibiting Macrophage STING Signaling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 117, 109931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R.F.; Tabas, I.; Pajvani, U.B. Mechanisms of Fibrosis Development in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1913–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Bu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Su, W.; Li, L.; Zhou, H.; Lu, L. XBP1 Deficiency Promotes Hepatocyte Pyroptosis by Impairing Mitophagy to Activate mtDNA-cGAS-STING Signaling in Macrophages during Acute Liver Injury. Redox Biol. 2022, 52, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Rajani, C.; Xu, H.; Zheng, X. Gut Microbiota Alterations Are Distinct for Primary Colorectal Cancer and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Chang, W.-Y.; Gong, D.-A.; Xia, J.; Chen, W.; Huang, L.-Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, K.; et al. High Dietary Fructose Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression by Enhancing O-GlcNAcylation via Microbiota-Derived Acetate. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1961–1975.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyoğlu, D.; Idle, J.R. The Gut Microbiota—A Vehicle for the Prevention and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 204, 115225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.S.; Sood, S.; Broughton, A.; Cogan, G.; Hickey, M.; Chan, W.S.; Sudan, S.; Nicoll, A.J. The Association between Diet and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Ge, X.; Lu, J.; Xu, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, Q.; Song, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C. Diet and Risk of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Cirrhosis, and Liver Cancer: A Large Prospective Cohort Study in UK Biobank. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-T.; Cheng, A.-C.; Liu, Y.-T.; Yan, C.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-F.; Tseng, P.-H. Persistent TLR4 Activation Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Growth through Positive Feedback Regulation by LIN28A/Let-7g miRNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Xu, D.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xiao, Q.; Peng, W.; Chen, B. A Multi-Omic Analysis Reveals That Gamabufotalin Exerts Anti-Hepatocellular Carcinoma Effects by Regulating Amino Acid Metabolism through Targeting STAMBPL1. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yi, Y.; Wu, T.; Chen, N.; Gu, X.; Xiang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Li, J.; Jin, H. Integrated Microbiome and Metabolome Analysis Reveals the Interaction between Intestinal Flora and Serum Metabolites as Potential Biomarkers in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1170748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Tan, Y.; Li, H.; Huang, J.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, M.; Zhu, L.; Hui, S.; Yang, J.; et al. Fecal 16S rRNA Sequencing and Multi-Compartment Metabolomics Revealed Gut Microbiota and Metabolites Interactions in APP/PS1 Mice. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 151, 106312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.; Jiang, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, P.; Song, R.; et al. Gut Microbiome Affects the Response to Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Xun, Z.; Zhang, D.; Lan, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chao, J.; Liang, Y.; Pu, Z.; et al. Characterizations of Multi-Kingdom Gut Microbiota in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Treated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e008686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.-Y.; Mei, J.-X.; Yu, G.; Lei, L.; Zhang, W.-H.; Liu, K.; Chen, X.-L.; Kołat, D.; Yang, K.; Hu, J.-K. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Anticancer Therapy: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, W. Drug-Microbiota Interactions: An Emerging Priority for Precision Medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhou, J.; Fan, J.; Zeng, Z.; Du, S. Gut Microbiota Modulate Radiotherapy-Associated Antitumor Immune Responses against Hepatocellular Carcinoma Via STING Signaling. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2119055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, P.; Ding, J. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2023, 555, 216038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Deng, Y.; Hao, Q.; Yan, H.; Wang, Q.-L.; Dong, C.; Wu, J.; He, Y.; Huang, L.-B.; Xia, X.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Gut Microbiota-Immunotherapy Synergy through Modulating Tumor Microenvironment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-C.; Wu, C.-J.; Hung, Y.-W.; Lee, C.J.; Chi, C.-T.; Lee, I.-C.; Yu-Lun, K.; Chou, S.-H.; Luo, J.-C.; Hou, M.-C.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Metabolites Associate with Outcomes of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Treated Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, X.; Zhang, S.; Guo, W. Overview of Microbial Profiles in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Adjacent Nontumor Tissues. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hou, Y.; Mu, L.; Yang, M.; Ai, X. Gut Microbiota Contributes to the Intestinal and Extraintestinal Immune Homeostasis by Balancing Th17/Treg Cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zheng, X.; Pan, T.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Peng, L.; Xie, C. Dynamic Microbiome and Metabolome Analyses Reveal the Interaction between Gut Microbiota and Anti-PD-1 Based Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 151, 1321–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.H.; Nguyen, V.H.; Jiang, S.-N.; Park, S.-H.; Tan, W.; Hong, S.H.; Shin, M.G.; Chung, I.-J.; Hong, Y.; Bom, H.-S.; et al. Two-Step Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy with Engineered Salmonella typhimurium Secreting Heterologous Flagellin. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaak9537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, W.; Sultonova, R.D.; Nguyen, D.-H.; Zheng, J.H.; You, S.-H.; Rhee, J.H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Khim, K.; Hong, Y.; et al. Synergistic Cancer Immunotherapy Utilizing Programmed Salmonella typhimurium Secreting Heterologous Flagellin B Conjugated to Interleukin-15 Proteins. Biomaterials 2023, 298, 122135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedi, M.H.; Yao, M.S.; Mittelstein, D.R.; Bar-Zion, A.; Swift, M.B.; Lee-Gosselin, A.; Barturen-Larrea, P.; Buss, M.T.; Shapiro, M.G. Ultrasound-Controllable Engineered Bacteria for Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, L.; Han, W.; Liang, Y.; Dong, J.; Ding, Y.; Li, W.; Lei, Q.; Li, J.; et al. Synergistic Genetic and Chemical Engineering of Probiotics for Enhanced Intestinal Microbiota Regulation and Ulcerative Colitis Treatment. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2417050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Nor, M.H.; Ayob, N.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Raja Ali, R.A.; Tan, G.C.; Wong, Z.; Shafiee, N.H.; Wong, Y.P.; Mustangin, M.; Nawawi, K.N.M. The Effect of Probiotics (MCP® BCMC® Strains) on Hepatic Steatosis, Small Intestinal Mucosal Immune Function, and Intestinal Barrier in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, R.Z.; Barbalho, S.M.; Sloan, K.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Gonzaga, H.F.; Grippa, P.C.; Zutin, T.L.M.; Girio, R.J.S.; Repetti, C.S.F.; Detregiachi, C.R.P.; et al. The Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics in Non-Alcoholic Fat Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciernikova, S.; Sevcikova, A.; Drgona, L.; Mego, M. Modulating the Gut Microbiota by Probiotics, Prebiotics, Postbiotics, and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: An Emerging Trend in Cancer Patient Care. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2023, 1878, 188990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Shi, J.; Peng, H.; Tong, R.; Hu, Y.; Yu, D. Probiotics and Liver Fibrosis: An Evidence-Based Review of the Latest Research. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 109, 105773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A.; Mohkam, M.; Soleimanian, S.; Sadraeian, M.; Lauto, A. Bacterial Nanotechnology as a Paradigm in Targeted Cancer Therapeutic Delivery and Immunotherapy. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, D.; Bi, D.; Li, L.; Tian, H.; Yin, F.; Zuo, T.; Ianiro, G.; Han, Y.W.; Li, N.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Transitioning from Chaos and Controversial Realm to Scientific Precision Era. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 970–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Cho, B.; Kim, S.-Y.; Do, E.-J.; Bae, D.-J.; Kim, S.; Kweon, M.-N.; Song, J.S.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Improves Anti-PD-1 Inhibitor Efficacy in Unresectable or Metastatic Solid Cancers Refractory to Anti-PD-1 Inhibitor. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1380–1393.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Ma, K. Microecological Regulation in HCC Therapy: Gut Microbiome Enhances ICI Treatment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegar, A.; Bar-Yoseph, H.; Monaghan, T.M.; Pakpour, S.; Severino, A.; Kuijper, E.J.; Smits, W.K.; Terveer, E.M.; Neupane, S.; Nabavi-Rad, A.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Current Challenges and Future Landscapes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e0006022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Ratziu, V.; Loomba, R.; Rinella, M.; Anstee, Q.M.; Goodman, Z.; Bedossa, P.; Geier, A.; Beckebaum, S.; Newsome, P.N.; et al. Obeticholic Acid for the Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis: Interim Analysis from a Multicentre, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 2184–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirolamo, C.; Modica, S.; Vacca, M.; Di Tullio, G.; Morgano, A.; D’Orazio, A.; Kannisto, K.; Parini, P.; Moschetta, A. Prevention of Spontaneous Hepatocarcinogenesis in Farnesoid X Receptor-Null Mice by Intestinal-Specific Farnesoid X Receptor Reactivation. Hepatology 2015, 61, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Disease | Increase | Decrease | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mice | NAFLD-HCC | Mucispirillum, Desulfovibrio, Anaerotruncus | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides | feces | [39] |

| mice | Liver cancer | Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides | feces | [40] | |

| mice | Cancer cachexia | Enterobacteriaceae | Lachnospiraceae | feces | [41] |

| mice | NAFLD-HCC | B. pseudolongum | feces | [42] | |

| mice | HCC | Lactobacillus reuteri | feces | [43] | |

| mice | HCC | Akkermansia muciniphila | feces | [32] | |

| mice | HCC | Bifidobacterium longum | feces | [44] | |

| mice | Obesity induced HCC | dysbiosis | Feces and intestinal contents | [45] | |

| mice | NASH-HCC | Atopobium spp., Bacteroides spp., Bacteroides vulgatus, B. acidifaciens, B. uniformis, Clostridium cocleatum, C. xylanolyticum, Desulfovibrio spp. | Bifidobacterium longum | feces | [46] |

| rat | DEN induced HCC | Enterobacteriaceae | Bifidobacterium spp. | feces | [47] |

| rabbit | VX2 HCC | Bacteroidaceae, Prevotellaceae, Flavobacteriaceae, Flavobacteriales, Alistipes, Marseille | Ruminiclostridium, Christensenellaceae, Enterorhabdus, Christensenellaceae, Mucispirillumgenera | feces | [48] |

| mice | HCC | dysbiosis | feces and intestinal contents | [49] | |

| mice | MYC transgenic spontaneous HCC | Gram-positive bacteria, Bacteria mediating primary-to-secondary bile acid conversion, Clostridium scindens | feces | [50] | |

| mice | HCC | Gram-positive bacteria | feces | [51] | |

| Model | Disease | Increase | Decrease | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| human | HCC | Bacteroides, Ruminococcaceae | Bifidobacterium | feces | [52] |

| human | NBNC-HCC | Bacteroides, Streptococcus, Ruminococcus gnavus group, Veillonella, Erysipelatoclostridium | Romboutsia, UCG-002, Lachnospiraceae NK4A-136, Eubacterium hallii group, Lachnospiraceae ND-3007 group, Erysipelotrichaceae UCG-003, Bilophila | feces | [53] |

| human | HCC | Bifidobacterium longum | feces | [44] | |

| human | HCC and ICC | Ruminococcaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, Bacteroidetes | feces | [54] | |

| human | HCC | Klebsiella, Haemophilus, Clostridium sensu stricto, Megasphaera, Acidaminococcus, Lactobacillus | Alistipes, Phascolarctobacterium, Ruminococcus, Oscillibacter, Coprococcus, Bilophila, ClostridiumIV, Butyricicoccus, Anaerostipes, Akkermansia, Allisonella, Coprobacillus | feces | [55] |

| human | HCC | Lachnoclostridium | feces | [56] | |

| human | HCC | Escherichia coli | feces | [57] | |

| human | HCC | Proteobacteria, Desulfococcus, Enterobacter, Prevotella, Veillonella | Cetobacterium | feces | [58] |

| human | PLC | Enterobacter ludwigii, Enterococcaceae, Lactobacillales, Bacilli, Gammaproteobacteria, Veillonella | firmicutes, bacteroidetes, Clostridia | feces | [59] |

| human | PLC | dysbiosis | feces | [60] | |

| human | HCC | Neisseria, Enterobacteriaceae, Veillonella, Limnobacter | Enterococcus, Phyllobacterium, Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Coprococcus | feces | [61] |

| human | HCC | Proteobacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, B. xylanisolvens, B. caecimuris, Ruminococcus gnavus, Clostridium bolteae, Veillonella parvula | Oscillospiraceae, Erysipelotrichacea | feces | [62] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zuo, S.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Luo, Y.; Su, L. The Dual Role of Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Context-Dependent Framework. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010073

Zuo S, Ma J, Li X, Fan Z, Li X, Luo Y, Su L. The Dual Role of Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Context-Dependent Framework. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuo, Shuyu, Junhui Ma, Xue Li, Zhengyang Fan, Xiao Li, Yingen Luo, and Lei Su. 2026. "The Dual Role of Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Context-Dependent Framework" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010073

APA StyleZuo, S., Ma, J., Li, X., Fan, Z., Li, X., Luo, Y., & Su, L. (2026). The Dual Role of Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Context-Dependent Framework. Microorganisms, 14(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010073