Abstract

The research employed Caenorhabditis elegans to compare the anti-infection and lifespan-extending properties of Bifidobacterium. The results demonstrated that BL-99 and YLGB-1496 intervention improved the nematodes’ resistance to Staphylococcus aureus infection, resulting in lifespan extensions of 5.90% and 14.38%, respectively, accompanied by the alleviation in the decline of pharyngeal pumping rate and locomotor capacity. Furthermore, both probiotic strains significantly extended the mean lifespan of nematodes by 10.96% and 12.14%, and significantly alleviated pharyngeal pumping and locomotion. Importantly, BL-99 and YLGB-1496 have different underlying mechanisms of action. Transcriptomic analyses indicated that the BL-99 strain enhanced nematode resistance to Gram-positive pathogens through the upregulation of lysozyme, saposin-like antimicrobial peptides, and c-type lectin family genes. Conversely, YLGB-1496 improved the epidermal permeability barrier by upregulating genes involved in collagen synthesis and assembly. Overall, this study provides novel insights into the species-specific effects of Bifidobacteria on pathogen resistance and lifespan extension.

1. Introduction

Bifidobacterium, a genus of bacteria prevalent in the human gut, has garnered increasing attention for its potential contributions to human health and longevity. Recent studies have indicated that a positive correlation between Bifidobacterium presence and lifespan [1,2,3]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that Bifidobacterium levels decline with age, potentially contributing to the onset of age-related diseases [4]. Additionally, the bifidogenic effect of 2-fucosyllactose, a prebiotic, has been shown to be age-specific, promoting the growth of different Bifidobacterium species depending on the age group [5]. These findings underscore the importance of considering age-related changes in the gut microbiome when developing targeted interventions.

Bifidobacterium has been recognized as a dominant constituent of the gut microbiota in both infants and centenarians, indicating its potential role in modulating immune responses and attenuating inflammation-related cytokines, which are essential for healthy aging [6]. This observation was consistent with research findings that Bifidobacterium species can enhance immune function and mitigate oxidative stress, both critical factors in delaying the aging process [7]. Additionally, Bifidobacterium can competitively inhibit the colonization of pathogenic bacteria, thereby reducing the proliferation of harmful microorganisms in the intestine [8]. Bifidobacterium can upregulate the expression of tight junction proteins, thereby enhancing the barrier integrity of intestinal epithelial cells [9]. It can also alleviate inflammation caused by infection by promoting the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibiting the expression of pro-inflammatory factors [10].

Research into the genomic diversity of Bifidobacterium species has unveiled substantial differences in their functional capabilities, which may play a crucial role in their health-promoting effects [11]. Ménard (2012) conducted a comparative analysis of the immunomodulatory functions of Bifidobacterium across four species and discovered that their capacity to stimulate the immune system is both species- and strain-specific [12]. Notably, species-specific variations are prevalent in the widely utilized strains of Bifidobacterium animalis and Bifidobacterium longum, particularly in the context of alleviating gastrointestinal, immune, and infectious diseases [13]. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis was distinguished by its extensive repertoire of genes associated with the utilization of human milk oligosaccharides, potentially conferring a competitive advantage within the gut microbiota and enhancing its probiotic efficacy [14]. Furthermore, the presence of bacteriocin gene clusters in Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis suggested a role in maintaining gut microbiota equilibrium and preventing pathogenic colonization, thereby supporting its potential in promoting longevity [15]. Bifidobacterium animalis was recognized for its high tolerance to acidic, bile, and oxygen-rich environments [16].This species-specific adaptation highlights the importance of understanding the ecological and metabolic strategies of different Bifidobacterium subspecies, as they may offer insights into their roles in promoting longevity [17].

Therefore, the differences in the efficacy and mechanism of action of bifidobacteria in prolonging lifespan and anti-infection have become an emerging research field. For this reason, we chose Caenorhabditis elegans as the model organism.

As a model organism, Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is well-suited for studies on anti-aging due to its advantages, including ease of cultivation, short life cycle, high reproducibility, and a fully sequenced genome [18]. Certain aging pathways and mechanisms have been shown to be conserved between C. elegans and humans. The genetic pathways involved in nematode aging, such as insulin signaling and the AMPK pathway, are highly conserved when compared to humans [19,20]. Research has demonstrated that mutations in the daf-2 gene can significantly extend the lifespan of nematodes by reducing insulin signal transduction through the daf-16/FOXO transcription factors, which are also considered to contribute to human longevity [21]. Consequently, C. elegans can serve as a model to investigate the anti-aging capabilities and mechanisms of probiotics.

Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BL-99 (BL-99) is a probiotic isolated from the gut of healthy infants [22], while Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis YLGB-1496 (YLGB-1496) was derived from human breast milk [23]. The objective of this study was to compare the lifespan-extending effects of Bifidobacterium strains in C. elegans and to elucidate the mechanistic differences underlying lifespan prolongation by distinct Bifidobacterium species through transcriptomic analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Nematodes Preparation

BL-99 and YLGB-1496 strains were procured from the National Technology Innovation Center for Dairy in Hohhot, China (Table S1). The bacterial cells were cultured in MRS broth at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. Following overnight incubation, the cells were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for three times, and resuspended in sterile PBS (pH 7.4) to achieve a concentration of 1 × 108 CFU/mL.

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923 (S. aureus) served as the Gram-positive pathogen and was cultured aerobically in LB broth at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacterial cells were then suspended in 0.25 mL of PBS buffer to a concentration of 1 × 108 CFU/mL, and 60 μL of this suspension was spread onto nematode growth medium (NGM) in 6.0 cm-diameter plates for nematode feeding.

Escherichia coli OP50 (OP50) and the Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) Bristol N2 strain were supplied by Professor Yanling Hao’s laboratory (Table S1). OP50 was cultured anaerobically in LB broth at 37 °C for 12 h and used as the standard feed for nematode cultivation. Nematodes were maintained and propagated on NGM following established protocols. Nematodes are synchronized before the experiment begins. After synchronization, L4 stage nematodes were transferred to modified NGM medium containing 50 mg/mL 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FUdR), which is utilized to inhibit nematode oviposition. After cell harvest, OP50 suspended in 0.25 mL PBS buffer (pH 7.4, sterile) to 1 × 108 CFU/mL, and 60 μL of suspension was then spread on NGM to feed the worms. In order to prevent pollution and maintain bacterial activity, OP50, S. aureus and probiotics are added to the plate in the form of concentrated solution, and the feeding solution and plate are renewed every 2–3 days. Nematodes eat fresh bacterial mixture every day.

2.2. Experimental Design

This experiment is mainly divided into two parts. The first part is about the protective effect of Bifidobacteria against S. aureus infection in nematode (Figure 1A). The young adult worms (0 days old) were assigned to either a control group that was fed OP50 or to a group that was fed BL-99 or YLGB-1496 for 10 days. The nematodes in the control group were only fed with OP50 for the first 10 days, and on the 11th day, OP50 and S. aureus were co-cultured without adding any probiotics. The concentration of Bifidobacterium BL-99 and YLGB-1496 bacterial solution is 1 × 108 CFU/mL, which is mixed with OP50 in a 1:1 ratio and evenly spread on an agar plate. The L4 synchronized worms were then transferred onto S. aureus lawns. The concentration of S. aureus (1 × 108 CFU/mL) was mixed with OP50 in a 1:1 ratio24. Each group was incubated at 20 °C, and their numbers were recorded daily until all worms died. The second component examines the impact of Bifidobacteria on the lifespan of nematodes. The nematodes in the control group were only fed with OP50 and no probiotics were added. Young adult worms, aged 0 days, were assigned to a control group fed with OP50, or to groups fed with BL-99 or YLGB-1496. L4 worms were then transferred onto OP50 lawns. The concentrations of BL-99 and YLGB-1496 were mixed with OP50 in a 1:1 ratio. Each group was incubated at 20 °C, with daily recordings of worm numbers until all worms had died. Sterility was kept during the co-culture of nematodes and bacteria.

2.3. Lifespan Measurement

For lifespan measurement, refer to the previously established method [24], where nematode eggs were retrieved from adult C. elegans following exposure to sodium hypochlorite/sodium hydroxide solution. The synchronized L4-stage nematodes were transferred to 35 mm NGM plates containing 50 mg/mL FUdR, and their numbers were recorded daily. In the BL-99 or YLGB-1496 treatment groups, C. elegans N2 were administered a diet of 1 × 108 CFU/mL BL-99 or YLGB-1496 for a duration of 10 days. Subsequently, each group was maintained at 20 °C until all nematodes had expired. In evaluating the condition of C. elegans, any nematode exhibiting no movement was classified as deceased. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

2.4. Pharyngeal Pumping Rate

The pharyngeal pumping rate assay was performed as described by Zhao et al. [25]. To evaluate the frequency in both the control and treatment groups (BL-99 and YLGB-1496), a total of 10 nematodes per biological replicate were placed onto their respective NGM plates seeded with OP50. The pharyngeal pumping rate, defined as the number of contractions per 10 s, was observed at specific time intervals using a stereo microscope.

2.5. Motility Assessment

The motility of C. elegans was assessed on days 11, 14, 17, and 20. The motility classification was determined according to previously established methods [26], with Class A assigned to nematodes that moved spontaneously and smoothly, leaving sinusoidal and symmetric tracks, and Class C designated for nematodes that only moved their head or tail when prodded with a soft wire. Class B was assigned when the behavioral class was intermediate between A and C. Class D was designated when nematodes dead.

2.6. Transcriptomic Analysis

Following 10 days treatment, the nematodes were cleaned three times using PBS, and then total RNA was extracted by QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, 79306). Each group has three replicates, and each replicate contains more than 1000 nematodes. Library establishment and RNA sequencing were performed by Majorbio (Shanghai, China). The library preparations were established by Illumina® Stranded mRNA Prep Ligation and were sequenced on NovaSeq Xplus (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Quality control of the sequencing data was conducted using fastp (Shifu Chen. fastp 1.0). Then, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between groups, and GO enrichment analyses of DEGs were conducted on a Majorbio Cloud Platform (https://www.majorbio.com/,accessed on 5 September 2025). DEGs were determined by p < 0.05, log2(fold change) > 1.5.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as mean ± standard error. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad 10.0 software. The percentage increase in lifespan is expressed as a percentage increase. All other data were analyzed for significance using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 indicates a significant difference, and a p-value < 0.01 indicates an extremely significant difference.

3. Results

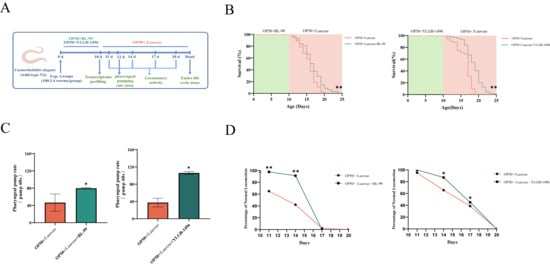

3.1. BL-99 and YLGB-1496 Enhanced the Tolerance of C. elegans to S. aureus Infection

In this study, we initially examined the protective effects of BL-99 and YLGB-1496 against S. aureus infection in nematodes. As illustrated in Figure 1B, nematodes fed with BL-99 and YLGB-1496 exhibited improved survival rates compared to those fed with OP50 following S. aureus infection. Specifically, BL-99 increased the mean lifespan of nematodes from 15.09 days to 15.98 days, representing a 5.9% enhancement, while YLGB-1496 extended the mean lifespan from 16.78 days to 19.19 days, indicating a 14.4% improvement .

Figure 1.

BL-99 and YLGB-1496 enhanced the tolerance of C. elegans to S. aureus infection. (A) Experimental flowcharts. (B) Survival curves of C. elegans that were fed OP50+BL-99, OP+YLGB-1496 or only OP50 for 10 days before infection with S. aureus. OP50+S. aureus worms, n = 93; OP50+BL-99+S. aureus worms, ** p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, n = 71; OP50+S. aureus worms, ** p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, n = 92, OP50+YLGB-1496+S. aureus worms, p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA, n = 88. (C) The pharyngeal pumping rate from 12th N2 worms grown on OP50+BL-99 or OP50+YLGB-1496 for 10 days before infection with S. aureus compared to OP50+S. aureus worms (* p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, n = 20). (D) The Class A of locomotory activity of different groups C. elegans on the 11th, 14th, 17th and 20th day (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, Chi-squared test, n ≥ 90 worms).

The pharyngeal pumping rate, a key indicator of nematode health during feeding, was significantly impacted by S. aureus infection, reducing to approximately 40 times per minute by day 12 (Figure 1C). In the BL-99 intervention group, the pharyngeal pumping frequency increased by 71.33% compared to the S. aureus group , whereas the YLGB-1496 intervention group exhibited an increase of 183.93%. Therefore, the YLGB-1496 intervention group showed better improvement in pharyngeal pumping ability than the BL-99 group.

Locomotory activity, another critical measure of nematode health, was evaluated on days 11, 14, 17, and 20. As illustrated in Figure 1D, infection with S. aureus resulted in a significant reduction in the locomotory activity of nematodes. In contrast, nematodes in the BL-99-fed group demonstrated markedly higher levels of coordinated sinusoidal locomotion (classified as class A) compared to the control group on days 11 and 14 . Concurrently, the intervention with YLGB-1496 improved nematode motility, with the effects persisting until day 17 . These findings suggested that both BL-99 and YLGB-1496 enhanced the tolerance of C. elegans to S. aureus infection, with YLGB-1496 exhibiting better efficacy. From the proportion of A-class motor ability on the 17th day, the YLGB-1496 group showed better improvement in nematode ability.

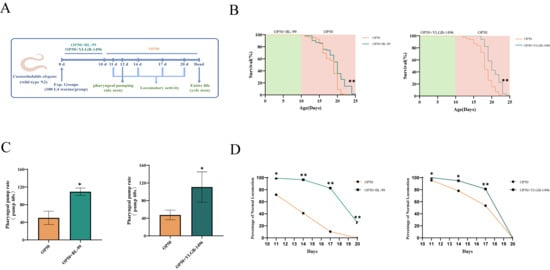

3.2. BL-99 and YLGB-1496 Prolonged the Lifespan of C. elegans

In the aforementioned study, we identified that the two bifidobacteria strains not only combated pathogenic bacterial infections but also potentially extended the lifespan of nematodes. To substantiate this observation, we conducted experiments using uninfected nematodes to assess the lifespan-prolonging effects of BL-99 and YLGB-1496 (Figure 2B). Compared to nematodes fed solely on OP50, those treated with BL-99 and YLGB-1496 exhibited a significant increase in lifespan (p < 0.05). Specifically, BL-99 extended the mean lifespan of nematodes from 16.73 days to 18.73 days, representing an increase of 10.96%, while YLGB-1496 extended the mean lifespan from 18.64 days to 20.90 days, corresponding to a 12.14% increase.

Figure 2.

BL-99 and YLGB-1496 prolonged the lifespan of C. elegans. (A) Experimental flowcharts. (B) Survival curves of C. elegans that were fed OP50+BL-99, OP+YLGB-1496 or only OP50 for 10 days. OP50 worms, n = 83, OP50+BL-99 worms, n = 71 and OP50 worms, n = 85, OP50+YLGB-1496 worms, n = 84, ** p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA. (C) The pharyngeal pumping rate from 12th N2 worms grown on OP50+BL-99 or OP50+YLGB-1496 for 10 days compared to OP50 worms (* p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, n = 20). (D) The Class A of locomotor activity from wild-type N2 worms grown on OP50 andOP50 BL-99, YLGB-1496 was measured on the 11th, 14th, 17th and 20th day (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, Chi-squared test, n ≥ 90).

We evaluated two common indicators of aging: pharyngeal pumping rates and locomotor abilities, under the interventions of BL-99 and YLGB-1496, to assess the overall health status of nematodes. As the nematodes aged naturally, a decline in pharyngeal pumping rates was observed in the OP50-fed group after 10 days. In contrast, nematodes fed with BL-99 and YLGB-1496 exhibited significantly higher pharyngeal pumping rates compared to the control group, with increases of 118.67% and 133.80%, respectively (p < 0.05, Figure 2C).

Locomotor activity was also assessed on days 11, 14, 17, and 20. As depicted in Figure 2D, the locomotor abilities of the nematodes diminished with natural aging. The BL-99-fed group demonstrated superior locomotor activity compared to the control group throughout the testing period . Additionally, the YLGB-1496 intervention improved nematode motility, with effects lasting until day 17 . These findings suggested that BL-99 and YLGB-1496 significantly delayed the natural aging process in nematodes and enhanced their feeding and motility capabilities.

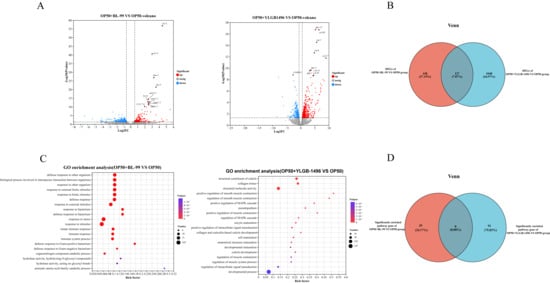

3.3. Transcriptional Analysis of C. elegans After Feeding with BL-99 and YLGB-1496

The aforementioned results demonstrated that nematodes subjected to a 10-day regimen of BL-99 and YLGB-1496 exhibited notable extensions in lifespan and increased resistance to pathogenic bacterial infections. To investigate the impact of these bifidobacterial supplements on nematodes, we utilized transcriptomic analysis to conduct a comprehensive assessment of gene expression following the 10-day feeding period with BL-99 and YLGB-1496. Differential gene expression (DGE) analysis was conducted to compare the Bifidobacteria groups with the OP50 group (p < 0.05, log2(fold change) > 1.5). As illustrated in Figure 3A, the BL-99 and YLGB-1496 groups exhibited 522 and 1138 differentially expressed genes, respectively, when compared to the OP50 group. Specifically, the BL-99 group showed 235 significantly upregulated and 287 significantly downregulated genes, while the YLGB-1496 group displayed 737 significantly upregulated and 401 significantly downregulated genes.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional analysis of C. elegans after feeding with BL-99 and YLGB-1496. (A) Gene expression profiles of OP50+BL-99 or OP50+YLGB-1496 C. elegans expression werecompared with OP50 worms. Volcano plot showing the up- and down-regulated genes in OP50+BL-99 or OP50+YLGB-1496 groups with OP50 C. elegans (p < 0.01 and Fold Change > 1.5). (B) The Venn plot of differential genes between OP50+BL-99 and OP50+YLGB-1496 C. elegans. (C) GO-BP enrichment of the up-regulated genes in OP50+BL-99 and OP50+YLGB-1496. Some GO terms were specified. (D) The Venn plot of the GO gene set: OP50+BL-99 groups enrichment pathway for defense response to Gram-positive bacterium. OP50+YLGB-1496 groups enrichment pathway for structural molecular activity. Each group has three replicates, n > 1000.

To elucidate the similarities and differences in the effects of BL-99 and YLGB-1496 on nematodes, a Venn diagram analysis was conducted to identify overlapping DEGs. As depicted in Figure 3B, only 127 DEGs were common to both treatment groups, representing 7.87% of the total. The BL-99 intervention group uniquely expressed 438 DEGs, whereas the YLGB-1496 intervention group uniquely expressed 1048 DEGs. This finding suggested that the beneficial mechanisms of BL-99 and YLGB-1496 against nematodes may differ.

To explore the mechanistic differences underlying the lifespan-prolonging effects of BL-99 and YLGB-1496, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was conducted. The GO functional enrichment analysis revealed that, in comparison to the OP50 group, the BL-99 treatment group was predominantly enriched in pathways related to response to bacterium, response to stimulus, response to stress, and immune response, all of which are closely associated with the innate defense system (Figure 3C). Notably, the defense response to Gram-positive bacterium pathway exhibited a high rich factor and included 29 DEGs.

In contrast, the YLGB-1496 intervention group showed significant enrichment in pathways such as collagen trimer, structural constituent of cuticle, and structural molecule activity (Figure 3C). Specifically, the structural molecule activity pathway included 91 DEGs. It is inferred that the YLGB-1496 intervention may enhance the integrity of the nematode cuticle, thereby providing increased protection against pathogenic bacteria.

The Venn diagram of the GO enrichment analysis was conducted to identify overlapping pathways between BL-99 and YLGB-1496 treatments. Notably, there were no shared pathways among the 29 pathways significantly enriched in the BL-99 group and the 91 pathways significantly enriched in the YLGB-1496 group. This observation further substantiated the hypothesis that the mechanisms through which these two probiotic strains exert beneficial effects on nematodes are likely distinct.

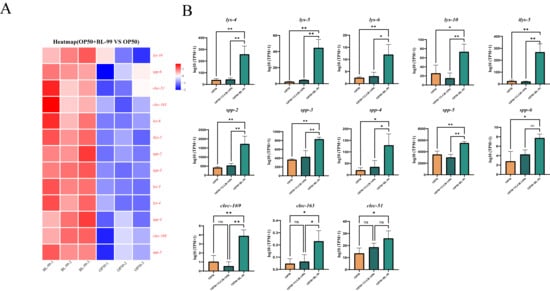

3.4. BL-99 Intervention Enhanced the Defense Response to Gram-Positive Bacteria of Nematode

The pathway related to the defense response to Gram-positive bacteria was enriched, highlighting genes activated in response to the presence of a Gram-positive bacterium, which function to protect the organism. Subsequently, we compared the major DEGs within this pathway between the BL-99-treated group and the control group. As illustrated in Figure 4A, relative to the OP50-treated group, 13 significantly upregulated genes (indicated in red) were identified in the BL-99-treated group (p < 0.05). These included five genes associated with lysozyme activity (lys-4, lys-5, lys-6, lys-10, and ilys-5), three genes associated with C-type lectin (clec-51, clec-163, and clec169), and five genes associated with saposin-like antimicrobial proteins (spp-2, spp-3, spp-4, spp-5, and spp-6). All these genes are implicated in mediating host defense and play a crucial role in the organism’s protective mechanisms.

Figure 4.

BL-99 intervention enhanced the defense response to Gram-positive bacteria of nematode. (A) Up regulation gene heat map in GO terminology of defense response of Gram-positive bacteria in BL-99 feeding group. (B) Bl-99 feeding group significantly increased gene expression in OP50, BL-99, YLGB-1496 feeding groups. Each group has three replicates, n > 1000, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

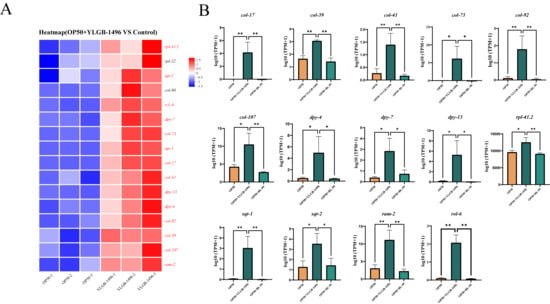

3.5. YLGB-1496 Intervention Enhanced the Structural Molecule Activity of Nematode

The structural molecule activity pathway, which is enriched with genes contributing to the structural integrity of complexes, was also analyzed. We compared the primary DEGs in this pathway between the YLGB-1496-treated group and the control group. As illustrated in Figure 5A, relative to the OP50 group, 14 genes were significantly upregulated in the YLGB-1496 group (p < 0.05), including 6 genes associated with cuticle development involved in collagen (col-17, col-39, col-41, col-73, col-92, and col-107), 7 genes associated with cuticle collagen coding (dyp-4, dyp-7, dyp-13, sqt-1, sqt-2, rol-6, and ram2), 1 genes associated with encoding ribosomal proteins (rpl41.2). Notably, the DEGs predominantly indicated that YLGB-1496 intervention enhances cuticle collagen synthesis in nematodes.

Figure 5.

YLGB-1496 intervention enhanced the structural molecule activity of nematode. (A) Up regulation gene heat map in GO terminology of structural molecule activity in YLGB-1496 feeding group. The colors in the figure represent the standardized expression levels of the gene in each sample, with red indicating higher expression levels and blue indicating lower expression levels. The numbers under the color bars indicate specific changes in expression levels. (B) YLGB-1496 feeding group significantly increased gene expression in OP50, BL-99, YLGB-1496 feeding groups. Each group has three replicates, n > 1000, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

This study utilized C. elegans as a model organism in conjunction with transcriptomic analysis to compare the anti-aging effects, anti-infective capabilities, and underlying mechanisms of the probiotic strains BL-99 and YLGB-1496. Experimental results demonstrated that feeding C. elegans with BL-99 and YLGB-1496 significantly extended the mean lifespan of wild-type nematodes by 10.96% and 12.14%, respectively, while also ameliorating age-related phenotypes and delaying the decline in pharyngeal pumping rate and locomotor capacity during aging. Furthermore, both strains enhanced nematode tolerance to Staphylococcus aureus infection, increasing lifespan by 5.90% and 14.38%, respectively, and significantly attenuating the age-associated deterioration in pharyngeal pumping and movement. In these assays, BL-99 and YLGB-1496 exhibited comparable anti-aging and anti-infective efficacies. However, transcriptomic analyses revealed that the molecular mechanisms underlying their effects were nearly distinct, with only 7.87% of differentially expressed genes overlapping between the two strains compared to the control group, and no shared pathways identified in GO enrichment analysis. Specifically, the BL-99 intervention uniquely augmented the nematode’s defense response against Gram-positive bacteria, whereas the YLGB-1496 intervention primarily enhanced the synthesis capacity of structural molecules, particularly collagen, in nematodes.

Numerous targets and pathways influence the lifespan of nematodes. Recent experimental evidence indicated that Bifidobacteria can extend nematode lifespan through various signaling pathways. For instance, B. longum strain BB68 enhanced nematode longevity by activating the TIR-1-JNK-1-DAF-16 signaling pathway [25]. B. infantis modulated nematode lifespan via the TOL-1/TLR pathway [27]. Additionally, B. animalis subsp. lactis BPL1™ prolonged longevity in C. elegans through its lipoteichoic acid by an insulin/IGF-1-dependent mechanism [28]. Furthermore, cell wall components of B. infantis BI increased the average lifespan of C. elegans by activating skn-1, regulated by the p38 MAPK pathway. Given the complexity of the targets and pathways involved, we employed transcriptomic analysis to compare the action pathways of two strains.

The efficacy of bifidobacteria varies across species. These effects have been validated in various models, including mice, Drosophila melanogaster, and C. elegans. For instance, B. adolescentis has been shown to regulate catalase activity and host metabolism, improve osteoporosis and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of premature aging, and increase both health span and lifespan in C. elegans [29]. B. longum subsp. longum YS108R has been demonstrated to alleviate DSS-induced colitis through its anti-inflammatory properties, by protecting mucosal barrier integrity and maintaining gut microbiota homeostasis [7]. B. animalis subsp. lactis LKM512 mitigated obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance by modifying gut microbiota in high-fat diet-induced obese mice and prolongs the lifespan of the host [30]. In previous studies, it has been found that BL-99 and YLGB-1496 belong to different species of Bifidobacterium, which are clearly different in taxonomy, and the reported efficacy is not the same [22,23]. Similarly, in our study, although BL-99 and YLGB-1496 exhibited comparable lifespan-extending effects, transcriptomic analyses indicated that their mechanisms were fundamentally different.

In this study, the BL-99 groups exhibited significant enrichment in defense responses against Gram-positive bacteria, including the upregulation of lysozyme, saposin-like antimicrobial peptides, and c-type lectin family genes. The defense response against Gram-positive bacteria is critical for responding to external stimuli and maintaining health. This response is particularly significant for the elderly [31]. As Gram-positive bacteria, such as S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, Listeria monocytogenes, etc. S. aureus can lead to pneumonia, thereby increasing the risk of respiratory failure and heart failure [32]. Listeria monocytogenes poses a significant threat to the elderly and immunocompromised individuals, as it can infiltrate the body via the digestive and respiratory tracts, as well as through skin lesions [33]. Consequently, bolstering resistance to bacterial and viral infections is crucial for the elderly demographic. Enhancing anti-infective measures can substantially improve recovery rates and reduce mortality in this population. Research by Jane M. Natividad et al. demonstrated that B. brevis NCC2950 can stimulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides, thereby augmenting the defense mechanisms in mice against Gram-positive bacteria [34]. Furthermore, Miroslav Dinić et al. found that Lactobacillus curvatus BGMK2-41 activated the PMK-1/p38 MAPK immunity pathway, which extended the survival of C. elegans when exposed to S. aureus in nematode [35].

In our study, the intervention with BL-99 significantly upregulated the expression of lys-4, lys-5, lys-6, and ilys-5, thereby contributing to pathogen resistance. Lysozyme plays a crucial role in various physiological processes, including the elimination of pathogenic organisms, the processing of endocytosed nutrients, and antigen presentation [36]. The genes encoding lysozyme, specifically lys-6, lys-4, lys-5, and ilys-5, have demonstrated responsiveness to both pathogenic and non-pathogenic microorganisms, with a sequential decrease in sensitivity. Lysozyme exerts its antibacterial activity by degrading bacterial peptidoglycan through its enzymatic action [37]. Lysozyme can degrade bacterial peptidoglycan, enhancing antibacterial activity.

In our study, the BL-99 intervention significantly increased the expression of spp-2 and spp-3, thereby playing a crucial role in combating pathogenic organisms. Saposin-like antimicrobial peptides constitute a group of polypeptides that play a significant role as antimicrobial agents in the innate immunity of C. elegans [38]. Among the genes encoding these peptides, spp-2 and spp-3 have been shown to enhance the organism’s resistance to infections [39]. These peptides can form pores in phospholipid vesicles, potentially facilitating interactions between the worms and microorganisms [40].

In our investigation, BL-99 intervention significantly elevated the expression levels of clec-51, clec-163, and clec-169, which are members of the C-type lectin gene family. According to existing literature, it is hypothesized that these genes play a pivotal role in enhancing immune function. The C-type lectin family constitutes a critical element of innate immunity in eukaryotic organisms [41]. An upregulation in the expression of C-type lectin family genes indicates that C. elegans may sustain their anti-aging phenotype by augmenting immune surveillance and maintaining protein homeostasis [42]. The secretion of C-type lectins can bolster resistance against pathogenic bacterial infections [43].

In this study, the YLGB-1496 treatment groups demonstrated significant enrichment in the enhancement of the stratum corneum and collagen structure, including the development of the collagen stratum corneum, as well as the synthesis and assembly of collagen. Collagen is integral to human health, particularly in the context of aging. Research by Yao Zhu et al. has demonstrated that the structural components of the stratum corneum may significantly influence developmental and aging processes [44]. A reduction in collagen can compromise the skin barrier function in elderly individuals, leading to thinning of the epidermis and dermis and diminished antibacterial capacity of the skin [45]. The epidermis and eggshell of C. elegans are abundant in collagen, keratin, and chitin, which confer resistance against the virulence factors of fungal hydrolytic enzymes [46]. The ability to enhance collagen synthesis can contribute to the increased longevity of nematodes [20].

In our research, intervention with YLGB-1496 markedly upregulated the expression of the col-92 gene, thereby enhancing the epidermal barrier. Collagen is crucial for maintaining the permeability barrier of the stratum corneum, thereby preventing the invasion of bacteria such as S. aureus through the epidermis. As the primary physical defense mechanism in nematodes, the stratum corneum is instrumental in preventing the invasion, accumulation, and dissemination of pathogens to internal tissues such as the intestine or epidermis, thus mitigating cell damage and mortality due to infection. Valentina Taverniti et al. found that multiple strains of probiotics can improve intestinal barrier function and reduce inflammation in mice [47]. The collagen-encoding gene col-92 has been identified as playing a significant role in the defense against Bacillus thuringiensis [48].

The synthesis of collagen, which constitutes the epidermis, is a complex process that spans the entire life cycle of C. elegans [49]. The regulation of collagen synthesis by these genes may induce alterations in the exoskeleton, thereby influencing the growth and development of C. elegans [50]. The dpy-13 gene, which encodes epidermal collagen, is extensively utilized as a marker for aging in the evaluation of tissue integrity and lifespan in nematodes. Research by Nidhi Thakkar et al. demonstrated that the root extract of Withania somnifera can significantly upregulate the expression of collagen-related genes, such as dpy-13 in senescent nematodes [51], corroborating the upregulation findings of the dpy-13 gene in this study.

The maintenance of the epidermal permeability barrier through collagen is crucial for the anti-infective defense of nematodes. Increased infiltration of morphologically abnormal cells renders nematodes more vulnerable to infection by S. aureus, conversely, enhancing the barrier can improve survival rates. Collagen encoded by the rol family genes is essential for maintaining the penetration barrier of the cuticle, thereby preventing bacterial invasion, such as by S. aureus, through the epidermis.

Collectively, our results demonstrate that the intervention with YLGB-1496 significantly upregulated the expression of the gene rol-6, playing a crucial role in maintaining the epidermal permeability barrier through collagen synthesis. Research has demonstrated that the downregulation of certain genes can result in morphological abnormalities and increased infiltration of the cuticle, rendering nematodes more susceptible to S. aureus. Conversely, upregulation of these genes enhances survival rates by fortifying the barrier [52].

5. Conclusions

This study compared the effects of two Bifidobacterium strains on pathogen resistance and lifespan extension in C. elegans. Although both Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BL-99 and Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis YLGB-1496 demonstrated similar capabilities in combating infections and extending lifespan, their mechanisms of action were notably distinct. The BL-99 strain enhanced nematode resistance to Gram-positive pathogens by upregulating the expression of lysozyme, saposin-like antimicrobial peptides, and c-type lectin family genes, thus enhancing the anti-infection ability and prolonging the life span. In contrast, the YLGB-1496 strain improved the epidermal permeability barrier by upregulating genes associated with collagen synthesis and assembly, thereby contributing to pathogen resistance and anti-aging effect. This study provides new evidence for the species-specific effects of bifidobacteria in pathogen resistance and lifespan extension.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms13122861/s1, Table S1: All strains used in this study.

Author Contributions

Methodology, investigation and writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; investigation and writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; project administration, W.Z. and Z.Z.; conceptualization and funding acquisition, J.H.; conceptualization and funding acquisition, H.L.; data curation, B.F., H.G., Y.L. and J.L.; conceptualization, funding acquisition and project administration, W.H.; conceptualization, investigation, writing—review and editing and funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFD2100903, 2023YFF1104501), National Center of Technology Innovation for Dairy (No. 2024-JSGG-027), R&D Program of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (23JF0006).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our research did not include any human subjects and higher animal experiments. We used the Caenorhabditis elegans as an in vivo model, which belongs to multicellular organisms, and we strictly abided by the relevant regulations during the experiments.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that they have no known financial conflicts or personal relationships that could have influenced the work presented in this paper.

References

- Luan, Z.; Sun, G.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.S.; Yang, R.F.; Li, C.Y.; Wang, T.T.; Tan, D.; Qi, S.R.; Jun, C.; et al. Metagenomics study reveals changes in gut microbiota in centenarians: A cohort study of hainan centenarians. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepp, E.; Smidt, I.; Rööp, T.; Stsepetova, J.; Koljalg, S.; Mikelsaar, M.; Soidla, I.; Ainsaar, M.; Kolk, H.; Vallas, M.; et al. Comparative analysis of gut microbiota in centenarians and young people: Impact of eating habits and childhood living environment. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 851404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleya, S.; Watkins, C.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. Gut Bifidobacteria populations in human health and aging. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G.H.; Li, H.Y.; Xie, L.J.; Fan, J.Y.; Li, S.Y.; Yu, W.Q.; Xu, Y.T.; He, M.L.; Jiang, Y.; Bai, X.; et al. Intestinal flora was associated with occurrence risk of chronic non-communicable diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firrman, J.; Deyaert, S.; Mahalak, K.K.; Liu, L.S.; Baudot, A.; Joossens, M.; Poppe, J.; Cameron, S.J.S.; van den Abbeele, P. The bifidogenic Effect of 2′fucosyllactose is driven by age-specific Bifidobacterium species, demonstrating age as an important factor for gut microbiome targeted precision medicine. Nutrients 2025, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, G.; Lugli, G.A.; Bianchi, M.G.; Rizzo, S.M.; Tarracchini, C.; Mancabelli, L.; Vergna, L.M.; Alessandri, G.; Fontana, F.; Taurino, G.; et al. Highly conserved bifidobacteria in the human gut: Subsp. longum as a potential modulator of elderly innate immunity. Benef. Microbes 2024, 15, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, J.; Baca, A.; Taboada, L.; alvarez-Calatayud, G.; de la Fuente, M. Consumption of a probiotic blend with Vitamin D improves immunity, redox, and inflammatory state, decreasing the rate of aging-a pilot study. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, S.; Toh, H.; Hase, K.; Oshima, K.; Nakanishi, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Tobe, T.; Clarke, J.M.; Topping, D.L.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature 2011, 469, 543–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, K.R.; Liu, S.X.L.; Tian, R.L.; Kushnir, A.; Turner, J.R.; Li, H.L.; Chou, P.M.; Weber, C.R.; De Plaen, I.G. Bifidobacterial stabilize claudins at tight junctions and prevent intestinal barrier dysfunction in mouse necrotizing enterocolitis. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, S.; Hall, L.J.; Cronin, M.; Zomer, A.; MacSharry, J.; Goulding, D.; Motherway, M.O.; Shanahan, F.; Nally, K.; Dougan, G.; et al. Bifidobacterial surface-exopolysaccharide facilitates commensal-host interaction through immune modulation and pathogen protection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2108–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasolli, E.; Mauriello, I.E.; Avagliano, M.; Cavaliere, S.; De Filippis, F.; Ercolini, D. Bifidobacteriaceae diversity in the human microbiome from a large-scale genome-wide analysis. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ménard, O.; Butel, M.J.; Gaboriau-Routhiau, V.; Waligora-Dupriet, A.J. Gnotobiotic mouse immune response induced by Bifidobacterium sp strains isolated from infants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Wasan, A.; Sharma, R.K. Recent developments in probiotics: An emphasis on Bifidobacterium. Food Biosci. 2021, 41, 100993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liang, H.; He, W.; Gao, X.; Wu, Z.; Hu, T.; Lin, X.; Wang, M.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Genomic and functional diversity of cultivated Bifidobacterium from human gut microbiota. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Pei, Z.M.; Chen, Y.T.; Wang, H.C.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Lu, W.W. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis as widespread bacteriocin gene clusters carrier stands out among the Bifidobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0097923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriantsoanirina, V.; Allano, S.; Butel, M.J.; Aires, J. Tolerance of Bifidobacterium human isolates to bile, acid and oxygen. Anaerobe 2013, 21, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, N.; Ujcic-Voortman, J.; Verhoeff, A.P.; Mende, D.R. Priority effects, nutrition and milk glycan-metabolic potential drive Bifidobacterium longum subspecies dynamics in the infant gut microbiome. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.G.; Lin, C.X.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.J. Caenorhabditis elegans as an in vivo model for the identification of natural antioxidants with anti-aging actions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Artan, M.; Han, S.H.; Park, H.E.H.; Jung, Y.; Hwang, A.B.; Shin, W.S.; Kim, K.T.; Lee, S.J.V. VRK-1 extends life span by activation of AMPK via phosphorylation. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaw7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Pigatto, L.; Pocock, R.; Gopal, S. Functions of the extracellular matrix in development: Lessons from Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell. Signal. 2021, 84, 110006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.J.; Chen, W.D.; Wang, Y.D. DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor in aging and longevity. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, M.; Lan, H.; Wang, R.; Hung, W.-L.; He, J.; Fang, B. Modulation of intestinal smooth muscle cell function by bl-99 Postbiotics in functional constipation. Foods 2025, 14, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, W.; Sun, P.; Zhao, J.; Yan, S.; Wang, R.; Han, Y.; Liu, W.H.; Tan, S.; et al. Bifidobacterium infantis strain YLGB-1496 possesses excellent antioxidant and skin barrier-enhancing efficacy in vitro. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komura, T.; Ikeda, T.; Yasui, C.; Saeki, S.; Nishikawa, Y. Mechanism underlying prolongevity induced by bifidobacteria in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biogerontology 2013, 14, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, R.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, M.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H.; Ren, F. The transcription factor DAF-16 is essential for increased longevity in C. elegans exposed to Bifidobacterium longum BB68. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.L.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Liu, R.H. Blueberry extract promotes longevity and stress tolerance via DAF-16 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 5273–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Mizuno, Y.; Komura, T.; Nishikawa, Y.; Kage-Nakadai, E. Toll-like receptor homolog TOL-1 regulates Bifidobacterium infantis-elicited longevity and behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2019, 38, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, F.; Barrena, M.; Enrique, M.; Maicas, M.; Álvarez, B.; Tortajada, M.; Chenoll, E.; Ramón, D.; Martorell, P. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BPL1™ and its lipoteichoic acid modulate longevity and improve age/stress-related behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Chen, L.; Qi, Y.; Xu, J.; Ge, Q.; Fan, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Hou, T.; et al. Bifidobacterium adolescentis regulates catalase activity and host metabolism and improves healthspan and lifespan in multiple species. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zheng, A.; Ni, L.; Wu, L.; Hu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, Z.; Ni, Y. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis lkm512 attenuates obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance through the modification of gut microbiota in high-fat diet-Induced obese mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, e2100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, M.; Sun, J.; Wu, F.; Gao, H.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Tian, Q.; et al. PMN-MDSC: A culprit behind immunosenescence and increased susceptibility to clostridioides difficile infection during aging. Engineering 2024, 42, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Solh, A.A.; Sikka, P.; Ramadan, F.; Davies, J. Etiology of severe pneumonia in the very elderly. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 163, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, B.J.; Mahon, B.E.; Griffin, P.M.; Gould, L.H.; Tauxe, R.V.; Crim, S.M.; Jackson, K.A.; Gerner-Smidt, P.; Herman, K.M.; Henao, O.L. Vital signs: Listeria illnesses, deaths, and outbreaks--United States, 2009-2011. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2013, 62, 448–452. [Google Scholar]

- Natividad, J.M.; Hayes, C.L.; Motta, J.P.; Jury, J.; Galipeau, H.J.; Philip, V.; Garcia-Rodenas, C.L.; Kiyama, H.; Bercik, P.; Verdu, E.F. Differential induction of antimicrobial REGIII by the intestinal microbiota and Bifidobacterium breve NCC2950. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7745–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinić, M.; Jakovljević, S.; Đokić, J.; Popović, N.; Radojević, D.; Strahinić, I.; Golić, N. Probiotic-mediated p38 MAPK immune signaling prolongs the survival of Caenorhabditis elegans exposed to pathogenic bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, K.; Zamora, D.; Horm, T.; George, L.; Upchurch, C.; Randall, J.; Weaver, C.; Sanford, C.; Miller, A.; Hernandez, S.; et al. Regulators of lysosome function and dynamics in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda) 2017, 7, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Eng, S.A.; Lim, M.P.; Nathan, S. Beyond traditional antimicrobials: A Caenorhabditis elegans model for discovery of novel anti-infectives. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortjohann, M.; Leippe, M. Molecular characterization of ancient prosaposin-like proteins from the protist dictyostelium discoideum. Biochemistry 2024, 63, 2768–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierking, K.; Yang, W.; Schulenburg, H. Antimicrobial effectors in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: An outgroup to the arthropoda. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeckendorf, A.; Leippe, M. SPP-3, a saposin-like protein of Caenorhabditis elegans, displays antimicrobial and pore-forming activity and is located in the intestine and in one head neuron. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012, 38, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martorell, P.; Llopis, S.; Gonzalez, N.; Ramón, D.; Serrano, G.; Torrens, A.; Serrano, J.M.; Navarro, M.; Genovés, S. A nutritional supplement containing lactoferrin stimulates the immune system, extends lifespan, and reduces amyloid β peptide toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, C.L.; Tan, M.W. Regulation of aging and innate immunity in C. elegans. Aging Cell 2004, 3, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labed, S.A.; Wani, K.A.; Jagadeesan, S.; Hakkim, A.; Najibi, M.; Irazoqui, J.E. Intestinal epithelial wnt signaling mediates acetylcholine-triggered host defense against Infection. Immunity 2018, 48, 963–978.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, P.; Du, X.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Z. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms in cox-1 affect the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans through nuclear gene dct-15. Gene 2022, 845, 146776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, R.N.; Ghoreschi, K. Herpes zoster-prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Hautarzt 2022, 73, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Wanderley, L.F.; Costa Junior, L.M. The potential of plant and fungal proteins in the control of gastrointestinal nematodes from animals. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2019, 28, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverniti, V.; Cesari, V.; Gargari, G.; Rossi, U.; Biddau, C.; Lecchi, C.; Fiore, W.; Arioli, S.; Toschi, I.; Guglielmetti, S. Probiotics Modulate Mouse Gut Microbiota and Influence Intestinal Immune and Serotonergic Gene Expression in a Site-Specific Fashion. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 706135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatsenko, I.; Sinha, A.; Rödelsperger, C.; Sommer, R.J. New role for DCR-1/dicer in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity against the highly virulent bacterium bacillus thuringiensis DB27. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3942–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, I.L. Cuticle collagen genes. expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Genet. 2000, 16, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, A.D.; Kramer, J.M. Identification, sequence and expression patterns of the Caenorhabditis elegans col-36 and col-40 collagen-encoding genes. Gene 1993, 137, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, N.; Gajera, G.; Mehta, D.; Nair, S.; Kothari, V. Withania somnifera root extract (LongeFera(™)) confers beneficial effects on health and lifespan of the model worm Caenorhabditis elegans. Drug Target. Insights 2025, 19, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuru, A.; Hamazaki, Y.; Tomida, S.; Ali, M.S.; Komura, T.; Nishikawa, Y.; Kage-Nakadai, E. Nonpathogenic cutibacterium acnes confers host resistance against Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0056221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).