Variety of Bacterial Pathogens in Ticks Removed from Humans, Northeastern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction

2.3. PCR Assays and Sequencing

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Tick Sampling

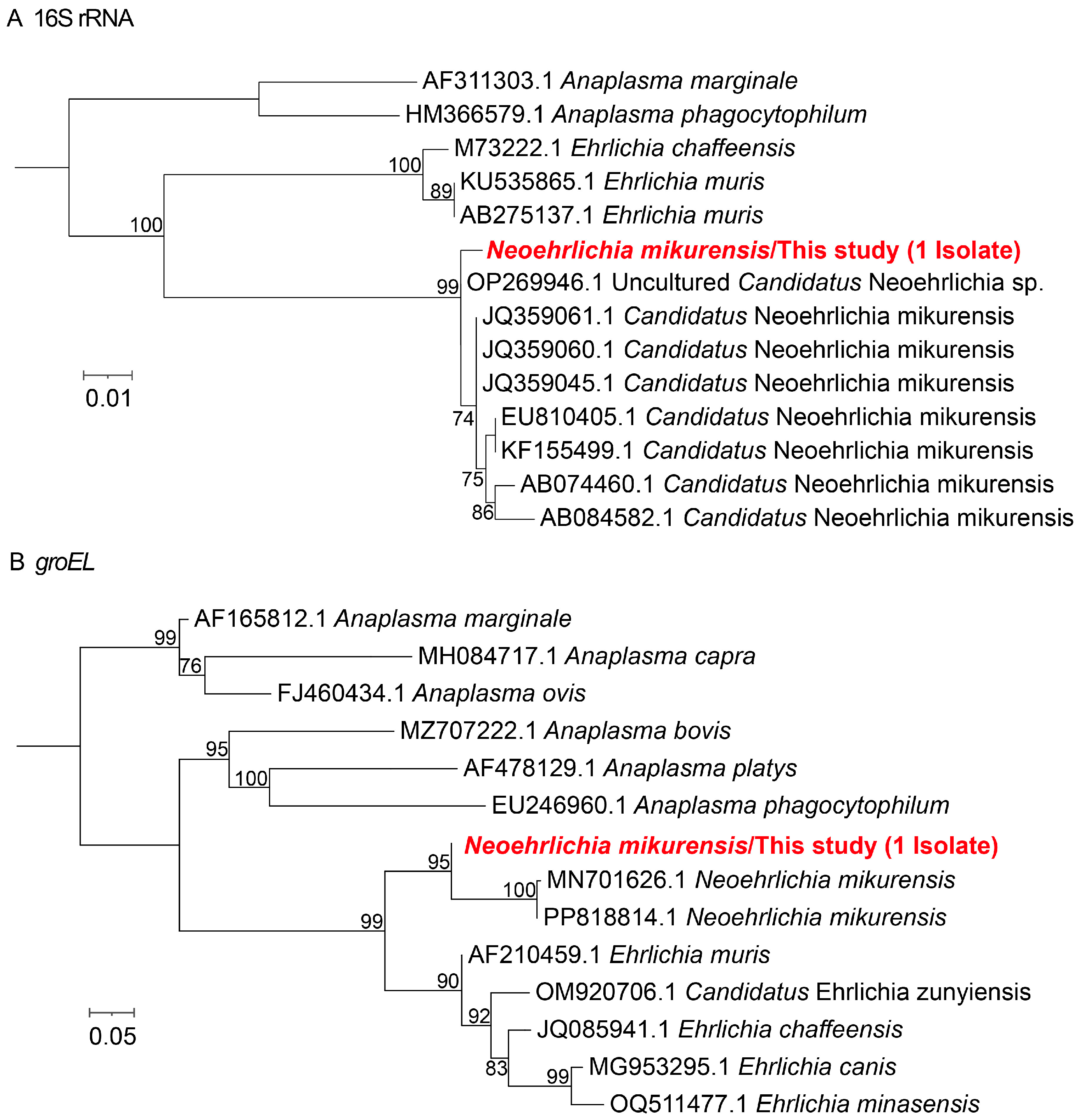

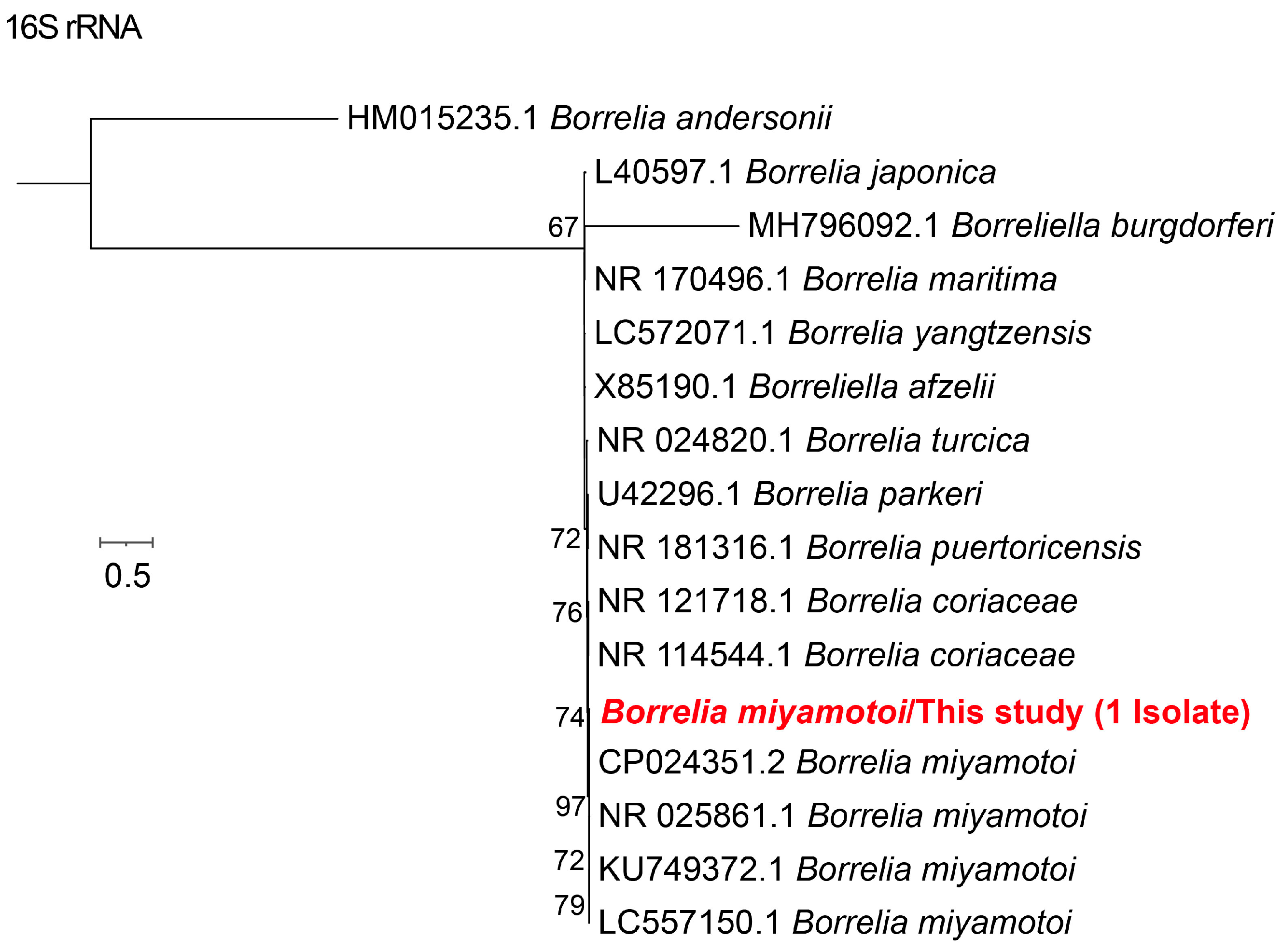

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of Different Tick-Borne Pathogens

3.3. Prevalence of Tick-Borne Pathogens

3.4. Coinfection of Tick-Borne Pathogens

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ML | Maximum Likelihood |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| s.l. | sensu lato |

References

- Dantas-Torres, F.; Chomel, B.B.; Otranto, D. Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases: A One Health Perspective. Trends Parasitol. 2012, 28, 437–446, Erratum in Trends Parasitol. 2013, 29, 516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2012.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paules, C.I.; Marston, H.D.; Bloom, M.E.; Fauci, A.S. Tickborne Diseases—Confronting a Growing Threat. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Zhang, M.-Z.; Su, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-F.; Du, L.-F.; Cui, X.-M.; Shi, W.; Zhu, D.-Y.; Zhao, L.; Xia, L.-Y.; et al. Emerging Tick-Borne Diseases in Mainland China over the Past Decade: A Systematic Review and Mapping Analysis. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2025, 59, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpertz, M.; Sevestre, J.; Luciani, L.; Houhamdi, L.; Fournier, P.-E.; Parola, P. Bacterial Agents Detected in 418 Ticks Removed from Humans during 2014–2021, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Ma, L.; Jia, N.; Jiang, B.-G.; Jiang, R.-R.; Huo, Q.-B.; Wang, Y.-W.; Liu, H.-B.; Chu, Y.-L.; et al. Human Infection with a Novel Tick-Borne Anaplasma Species in China: A Surveillance Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-Z.; Bian, C.; Ye, R.-Z.; Cui, X.-M.; Yao, N.-N.; Yang, J.-H.; Chu, Y.-L.; Su, X.-L.; Wu, Y.-F.; Ye, J.-L.; et al. A Series of Patients Infected with the Emerging Tick-Borne Yezo Virus in China: An Active Surveillance and Genomic Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, N.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Jiang, J.-F.; Ma, L.; Cao, W.-C. Human Infection with Candidatus Rickettsia Tarasevichiae. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1178–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, N.; Jiang, J.-F.; Huo, Q.-B.; Jiang, B.-G.; Cao, W.-C. Rickettsia Sibirica Subspecies Sibirica BJ-90 as a Cause of Human Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1176–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, N.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Ma, L.; Huo, Q.-B.; Ni, X.-B.; Jiang, B.-G.; Chu, Y.-L.; Jiang, R.-R.; Jiang, J.-F.; Cao, W.-C. Human Infections with Rickettsia Raoultii, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 866–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, J.-F.; Liu, W.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Huo, Q.-B.; Tang, K.; Zuo, S.-Y.; Liu, K.; Jiang, B.-G.; Yang, H.; et al. Human Infection with Candidatus Neoehrlichia Mikurensis, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1636–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-Z.; Bian, C.; Ye, R.-Z.; Cui, X.-M.; Chu, Y.-L.; Yao, N.-N.; Xu, X.-W.; Ye, J.-L.; Chen, L.; Yang, J.-H.; et al. Human Infection with a Novel Tickborne Orthonairovirus Species in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.-T.; Qiu, J.-H.; Chang, Q.-C.; Wang, C.-R. Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Dermacentor Silvarum and Comparative Analyses with Another Hard Tick Dermacentor Nitens. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 169, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battur, B.; Enkhtaivan, B.; Otgonsuren, D.; Davkharbayar, B.; Munkhgerel, D.; Amgalanbaatar, T.; Narantsatsral, S.; Davaasuren, B.; Zoljargal, M.; Myagmarsuren, P.; et al. First Record of Haemaphysalis Concinna (Acari: Ixodidae) Tick in the Khalkh Numrug Basin of Eastern Mongolia. Ticks Tick. Borne Dis. 2025, 16, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, C.M.; Newson, H.D.; Blakeslee, T.E. Insecticide Resistance in Houseflies of Japan, Korea, and the Ryukyu Islands. U S Armed Forces Med. J. 1958, 9, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bugmyrin, S.V.; Belova, O.A.; Bespyatova, L.A.; Ieshko, E.P.; Karganova, G.G. Morphological Features of Ixodes Persulcatus and I. Ricinus Hybrids: Nymphs and Adults. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2016, 69, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.-B.; Shi, W.-Q.; Wang, Q.; Pan, Y.-S.; Chang, Q.-C.; Jiang, B.-G.; Cheng, J.-X.; Cui, X.-M.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Wei, J.-T.; et al. Distribution of Dermacentor Silvarum and Associated Pathogens: Meta-Analysis of Global Published Data and a Field Survey in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunova, E.K.; Liapunova, N.A.; Tuul, D.; Otgonsuren, G.; Nomin, D.; Erdenebat, N.; Abmed, D.; Danchinova, G.A.; Sato, K.; Kawabata, H.; et al. Co-Infections with Multiple Pathogens in Natural Populations of Ixodes Persulcatus Ticks in Mongolia. Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Peña, A.; Jongejan, F. Ticks Feeding on Humans: A Review of Records on Human-Biting Ixodoidea with Special Reference to Pathogen Transmission. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1999, 23, 685–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; Du, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhan, W.; Jiang, J.-F.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Ji, P.; et al. Large-Scale Comparative Analyses of Tick Genomes Elucidate Their Genetic Diversity and Vector Capacities. Cell 2020, 182, 1328–1340.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.-Q.; Liu, K.; Li, X.-L.; Liang, S.; Yang, Y.; Yao, H.-W.; Sun, R.-X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, W.-J.; Zuo, S.-Q.; et al. Emerging Tick-Borne Infections in Mainland China: An Increasing Public Health Threat. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, H.; Lu, Q.-B.; Cui, N.; Yang, Z.-D.; Hu, J.-G.; Fan, Y.-D.; Guo, C.-T.; Li, X.-K.; Wang, Y.-W.; et al. Candidatus Rickettsia Tarasevichiae Infection in Eastern Central China: A Case Series. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 164, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediannikov, O.; Matsumoto, K.; Samoylenko, I.; Drancourt, M.; Roux, V.; Rydkina, E.; Davoust, B.; Tarasevich, I.; Brouqui, P.; Fournier, P.-E. Rickettsia Raoultii Sp. Nov., a Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia Associated with Dermacentor Ticks in Europe and Russia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 1635–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, P.; Rovery, C.; Rolain, J.M.; Brouqui, P.; Davoust, B.; Raoult, D. Rickettsia Slovaca and R. Raoultii in Tick-Borne Rickettsioses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Peña, A.; Ortega, C.; Sánchez, N.; Desimone, L.; Sudre, B.; Suk, J.E.; Semenza, J.C. Correlation of Borrelia Burgdorferi Sensu Lato Prevalence in Questing Ixodes Ricinus Ticks with Specific Abiotic Traits in the Western Palearctic. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3838–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steere, A.C.; Strle, F.; Wormser, G.P.; Hu, L.T.; Branda, J.A.; Hovius, J.W.R.; Li, X.; Mead, P.S. Lyme Borreliosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tijsse-Klasen, E.; Pandak, N.; Hengeveld, P.; Takumi, K.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Sprong, H. Ability to Cause Erythema Migrans Differs between Borrelia Burgdorferi Sensu Lato Isolates. Parasit. Vectors 2013, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritt, B.S.; Sloan, L.M.; Johnson, D.K.H.; Munderloh, U.G.; Paskewitz, S.M.; McElroy, K.M.; McFadden, J.D.; Binnicker, M.J.; Neitzel, D.F.; Liu, G.; et al. Emergence of a New Pathogenic Ehrlichia Species, Wisconsin and Minnesota, 2009. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, C.; Cote, M.; Paul, R.E.L.; Bonnet, S. Questing Ticks in Suburban Forest Are Infected by at Least Six Tick-Borne Pathogens. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011, 11, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutailler, S.; Valiente Moro, C.; Vaumourin, E.; Michelet, L.; Tran, F.H.; Devillers, E.; Cosson, J.-F.; Gasqui, P.; Van, V.T.; Mavingui, P.; et al. Co-Infection of Ticks: The Rule Rather Than the Exception. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igolkina, Y.P.; Rar, V.A.; Yakimenko, V.V.; Malkova, M.G.; Tancev, A.K.; Tikunov, A.Y.; Epikhina, T.I.; Tikunova, N.V. Genetic Variability of Rickettsia Spp. in Ixodes Persulcatus/Ixodes Trianguliceps Sympatric Areas from Western Siberia, Russia: Identification of a New Candidatus Rickettsia Species. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 34, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoylenko, I.; Shpynov, S.; Raoult, D.; Rudakov, N.; Fournier, P.-E. Evaluation of Dermacentor Species Naturally Infected with Rickettsia raoultii. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-S.; Liu, J.-Y.; Wang, B.-Y.; Wang, W.-J.; Cui, X.-M.; Jiang, J.-F.; Sun, Y.; Guo, W.-B.; Pan, Y.-S.; Zhou, Y.-H.; et al. Geographical Distribution of Ixodes Persulcatus and Associated Pathogens: Analysis of Integrated Data from a China Field Survey and Global Published Data. One Health 2023, 16, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Jiao, D.; Wang, J.-H.; Yao, D.-H.; Liu, Z.-X.; Zhao, G.; Ju, W.-D.; Cheng, C.; Li, Y.-J.; Sun, Y. Rickettsia Raoultii, the Predominant Rickettsia Found in Dermacentor Silvarum Ticks in China-Russia Border Areas. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2014, 63, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, D.; Hao, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J. Seasonal Abundance and Activity of the Tick Dermacentor Silvarum in Northern China. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2011, 25, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labruna, M.B.; McBride, J.W.; Bouyer, D.H.; Camargo, L.M.; Camargo, E.P.; Walker, D.H. Molecular evidence for a spotted fever group Rickettsia species in the tick Amblyomma longirostre in Brazil. J. Med. Entomol. 2004, 41, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Sun, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Han, H.; Tong, Z.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y.; et al. Detection of a novel Ehrlichia species in Haemaphysalis longicornis tick from China. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2016, 16, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, H.I. Molecular detection of Anaplasma, Ehrlichia and Rickettsia pathogens in ticks collected from humans in the Republic of Korea, 2021. Pathogens 2023, 12, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platonov, A.E.; Karan, L.S.; Kolyasnikova, N.M.; Makhneva, N.A.; Toporkova, M.G.; Maleev, V.V.; Fish, D.; Krause, P.J. Humans infected with relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia miyamotoi, Russia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1816–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karan, L.; Makenov, M.; Kolyasnikova, N.; Stukolova, O.; Toporkova, M.; Olenkova, O. Dynamics of spirochetemia and early PCR detection of Borrelia miyamotoi. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathogens | No. of Positive (%, 95%CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. persulcatus (n = 204) | D. silvarum (n = 16) | H. concinna (n = 8) | H. japonica (n = 4) | Total (n = 232) | |

| Ca. R. tarasevichiae | 82 (40.2, 33.7–47.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 82 (35.3, 29.5–41.7) |

| R. conorii subsp. raoultii | 1 (0.5, 0.1–2.7) | 4 (25.0, 10.2–49.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (2.2, 0.9–4.9) |

| E. muris | 20 (9.8, 6.4–14.7) | 2 (12.5, 3.5–36.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0, 4.56–69.9) | 23 (9.9, 6.7–14.4) |

| N.mikurensis | 1 (0.5, 0.1–2.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4, 0.1–2.4) |

| B. garinii | 38 (18.6, 13.9–24.5) | 2 (12.5, 3.5–36.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 40 (17.2, 12.9–22.6) |

| B. afzelii | 2 (1, 0.3–3.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.9, 0.2–3.1) |

| B. miyamotoi | 1 (0.5, 0.1–2.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4, 0.1–2.4) |

| Overall | 107 (52.5, 45.3–59.5) | 7 (43.8, 21.1–68.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0, 1.3–73.8) | 115 (49.6, 43.1–56.1) |

| Pathogens Coinfection | No. of Positive (%, 95%CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. persulcatus (n = 204) | D. silvarum (n = 16) | H. concinna (n = 8) | H. japonica (n = 4) | Total (n = 232) | |

| Ca. R. tarasevichiae + E. muris | 8 (3.92, 2~7.55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (3.45, 1.76~6.66) |

| Ca. R. tarasevichiae + B. garinii | 12 (5.88, 3.4~10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (5.17, 2.98~8.82) |

| Ca. R. tarasevichiae + B. afzelii | 1 (0.49, 0.09~2.72) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.43, 0.08~2.4) |

| Ca. R. tarasevichiae + B. miyamotoi | 1 (0.49, 0.09~2.72) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.43, 0.08~2.4) |

| B. garinii + E. muris | 1 (0.49, 0.09~2.72) | 1 (6.25, 1.11~28.33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.86, 0.24~3.09) |

| Ca. R. tarasevichiae + E. muris + B. garinii | 6 (2.94, 1.35~6.27) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.59, 1.19~5.53) |

| Ca. R. tarasevichiae + E. muris + B.afzelii | 1 (0.49, 0.09~2.72) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.43, 0.08~2.4) |

| E. muris + B. garinii + N. mikurensis | 1 (0.49, 0.09~2.72) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.43, 0.08~2.4) |

| Total | 31 (15.2, 10.92~20.76) | 1 (6.25, 1.11~28.33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 32 (13.79, 9.94~18.82) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, X.-L.; Ye, J.-L.; Zhang, M.-Z.; Wang, Y.-F.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.-F.; Bian, C.; Yao, N.-N.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Jiang, J.-F.; et al. Variety of Bacterial Pathogens in Ticks Removed from Humans, Northeastern China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122862

Su X-L, Ye J-L, Zhang M-Z, Wang Y-F, Sun Y, Wu Y-F, Bian C, Yao N-N, Zheng Y-C, Jiang J-F, et al. Variety of Bacterial Pathogens in Ticks Removed from Humans, Northeastern China. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122862

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Xiao-Ling, Jin-Ling Ye, Ming-Zhu Zhang, Yi-Fei Wang, Yi Sun, Ya-Fei Wu, Cai Bian, Nan-Nan Yao, Yuan-Chun Zheng, Jia-Fu Jiang, and et al. 2025. "Variety of Bacterial Pathogens in Ticks Removed from Humans, Northeastern China" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122862

APA StyleSu, X.-L., Ye, J.-L., Zhang, M.-Z., Wang, Y.-F., Sun, Y., Wu, Y.-F., Bian, C., Yao, N.-N., Zheng, Y.-C., Jiang, J.-F., Zheng, X.-M., & Cao, W.-C. (2025). Variety of Bacterial Pathogens in Ticks Removed from Humans, Northeastern China. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2862. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122862