Abstract

Most probiotics require separate administration from antibiotics due to sensitivity issues. Clostridium butyricum, however, exhibits intrinsic resistance, making it a promising candidate for combined therapy against diarrhea. In this study, a diarrhea model was established in mice induced by Escherichia coli, followed by treatment with azithromycin (AZM), C. butyricum (RH2), or their combination (COM) to assess therapeutic efficacy. The results demonstrated that mice in RH2 and COM groups achieved full body weight recovery and significant alleviation of diarrhea, accompanied by normalized fecal E. coli loads, preserved tissue integrity, reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α), and elevated anti-inflammatory IL-10. In contrast, AZM treatment led to sex-specific disparities in weight recovery and E. coli loads, and both sexes experienced relapse-prone diarrhea. Furthermore, the AZM group displayed shortened colons, sustained inflammatory infiltration, epithelial damage, and elevated IL-1β and male-specific IL-6. Gut microbiota analysis revealed that the COM group retained beneficial genera (e.g., Parabacteroides, Blautia) from the AZM group while uniquely enriching Lachnospiraceae taxa (e.g., NK4A136_group, FCS020_group). Untargeted metabolomics demonstrated the COM group activated GABA/arginine pathways, enhancing anti-inflammatory and barrier functions, whereas azithromycin disrupted butyrate synthesis and steroid metabolism. These findings highlight the advantage of combining C. butyricum with azithromycin for intestinal protection.

1. Introduction

Since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, antibiotics have been in use for nearly 100 years, saving countless lives. Antibiotics are effective and common drugs used in clinical practice to treat bacterial infections. The elimination of pathogenic bacteria also causes irreversible damage to beneficial bacteria, leading to a decrease in microbial diversity, proliferation of opportunistic pathogens, and impairment of metabolic functions [1,2,3]. Long-term antibiotic use disrupts the gut microbiota, resulting in side effects such as antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) and indigestion. Probiotics, recognized as one of the most effective interventions, are widely used to regulate gut microbiota balance, enhance immune function, and improve metabolic health [4]. However, traditional probiotics, such as lactic acid bacteria and Bifidobacterium, are susceptible to the antibiotics commonly used in clinical practice (β-lactam, aminoglycoside, and certain macrolide) [5], so co-administration with antibiotics may impair their viability. Therefore, it is generally recommended to space probiotic and antibiotic dosing by 2–3 h if used concurrently [6]. This staggered dosing approach not only complicates the treatment regimen but also increases the risk of patient confusion of administration timing, which potentially prolongs the course of therapy and increases the risk of antibiotic resistance [7].

Currently, it has been reported that Clostridium butyricum exhibits widespread intrinsic or acquired resistance to aminoglycoside and β-lactam antibiotics compared to conventional probiotics. Its spore form also confers broad tolerance to harsh gastrointestinal conditions. The resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics (e.g., gentamicin, kanamycin) is intrinsically linked to their highly conserved core genome architecture [8]. Due to their primary location in the chromosomal accessory regions, these resistance genes pose a low risk for horizontal transfer [9]. Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., penicillins and cephalosporins) is directly linked to the carriage of β-lactamase genes. Identification of linear megaplasmids has revealed that most clinical isolates encode a β-lactamase on these large plasmids, which can hydrolyze the β-lactam ring and thereby inactivate the antibiotic [10]. In its spore form, C. butyricum exhibits significant tolerance to a wide range of antibiotics. When spores were exposed to ten clinically common antibiotics (including β-lactams, macrolides, aminoglycosides, and tetracyclines), their survival rate exceeded 89% in intestinal fluid and remained above 60% under gastric acid conditions. This tolerance is attributed to the physical barrier function of the spore against antibiotic penetration [11]. The spores enter a dormant state upon antibiotic exposure and resume growth upon dilution. Experimental studies further confirmed that even when co-administered with clindamycin (a lincosamide antibiotic), the intestinal colonization level of C. butyricum MIYAIRI 588 (CBM 588) showed no significant reduction compared to the monotherapy group [12,13]. The protective spore structure shields the bacterium from antibiotic-induced damage, providing a foundation for combined therapeutic use. In contrast, genera such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are prone to carrying transferable resistance genes (e.g., tet(W), lnu(A)), posing a risk of plasmid-mediated dissemination. These resistance genes often share homology with clinically significant resistance determinants (e.g., the vanA gene in enterococci) [5,14]. Compared to these conventional probiotics, C. butyricum exhibits a more stable resistance profile and a lower risk of horizontal gene transfer, making it a promising candidate for development as a next-generation probiotic.

Beyond its favorable safety profile in terms of antibiotic resistance, the therapeutic potential of C. butyricum is primarily attributed to its direct functional contributions to gut health. As a key contributor to intestinal homeostasis, it competitively excludes opportunistic pathogens such as E. coli and Salmonella through niche occupation and nutrient competition, thereby promoting microbial ecological stability [15,16,17]. At the same time, it synthesizes vitamins and amino acids to facilitate the growth and colonization of beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which further enhance their resilience through cross-feeding interactions [18,19]. Furthermore, C. butyricum primarily produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, acetate, and small amounts of propionate in the animal intestine. Butyrate, as its core metabolic product, can promote cellular proliferation and repair, maintain mucosal integrity, and enhance barrier function [20,21]. Short-chain fatty acids can also lower the pH value of the intestinal tract, inhibit the proliferation of harmful bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella, and create an appropriate growth environment for acidophilic probiotics such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus [16,22]. Moreover, C. butyricum can stimulate the intestinal mucosal immune system, promote the proliferation and activation of immune cells such as macrophages and lymphocytes, and enhance their phagocytic ability and immune response [23,24]. At the same time, this bacterium can regulate the secretion of immune factors, promote the production of IL-10 and TGF-β, and inhibit the excessive secretion of pro-inflammatory factors (such as IL-6, TNF-α), thereby maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis and reducing inflammatory responses [15,20,25].

In this study, a mouse model of infectious diarrhea was successfully established through oral gavage of E. coli, with the primary objective of evaluating the potential interference of antibiotic co-administration on the therapeutic efficacy of C. butyricum. A comprehensive set of physiological and molecular parameters, including body weight changes, fecal consistency scores, fecal E. coli bacterial loads, colonic histomorphology, inflammatory cytokine levels, gut microbiota composition, and fecal metabolic profiles, was systematically monitored and compared following intervention with C. butyricum alone or in combination with azithromycin. The results provide critical experimental evidence and mechanistic insights that will inform the rational design of clinical regimens combining probiotics and antibiotics, ultimately contributing to improved therapeutic outcomes in the treatment of infectious diarrhea.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation and Preparation of Bacterial Strain

A single colony of strain E. coli SYP-B4131 (serotype O127:H6; EPEC, LEE+) was inoculated into 50 mL Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium and incubated at 37 °C at 200 rpm for 12 h. Then the culture was transferred into fresh LB medium with an inoculum ratio of 2:100 and continued to cultivate for 3 h. Afterwards, the bacterial strain was harvested by centrifugation at 8000× g for 10 min, and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer. Finally, the bacterial pellets were resuspended in PBS buffer and diluted to approximately 1 × 1010 CFU/mL. The Clostridium butyricum RH2 was provided by Hangzhou Grand Biologic Pharmaceutical Inc. (Hangzhou, China), demonstrated high spore survival rates (>89%) in simulated intestinal fluid across 10 antibiotics from four major classes (β-lactams, macrolides, aminoglycosides, and tetracyclines) [11]. A suspension of 1 × 109 CFU/mL was prepared by dissolving 0.5 g of a commercial spore powder (2.0 × 1010 CFU/g) in sterile PBS to a final volume of 10 mL.

2.2. Animals and Experimental Design

6~8-week-old BALB/c mice (half male and half female, 18–22 g) were obtained from Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shenyang, China). Laboratory Animal Use License No.: SYXK (Liao) 2021-0009. All animal procedures were conducted in strict compliance with the ethical standards established by the Laboratory Animal Management Committee of the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China (Approval Code: SYPU-IACUC-S2024-1016-114). Laboratory animals were maintained under a 12 h light/dark cycle in well-ventilated conditions at 24 ± 2 °C with 50–70% humidity. They were acclimatized for a week in individual cages with ad libitum access to sterile food and water.

50 BLAB/c mice were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 10 per group, with five males and five females): control (NC), model (MOD), azithromycin (AZM), C. butyricum (RH2), and azithromycin and C. butyricum combination therapy group (COM). During the modeling phase, mice in the NC group received daily oral gavage with 0.2 mL sterile PBS, whereas all other mice were administered 0.2 mL of E. coli SYP-B4131 bacterial suspension at approximately 1 × 1010 CFU/mL for three consecutive days.

On the second day of the modeling period, a 15-day therapeutic intervention was initiated. Mice in the NC and MOD groups received daily oral gavage of 0.3 mL sterile PBS. The AZM group was administered 65 mg/kg azithromycin plus 0.2 mL sterile PBS daily, whereas the RH2 group received 0.2 mL of a fresh C. butyricum suspension (1 × 109 CFU/mL, a dose of 2 × 108 CFU) [26,27] with 0.1 mL sterile PBS. The COM group was treated with a combination of 0.2 mL fresh C. butyricum suspension (1 × 109 CFU/mL) and 65 mg/kg azithromycin solution via daily intragastric gavage.

2.3. Sample Collection and Processing

Serum collection: Following a 15-day treatment period and a 12-h fasting period (with free access to water), mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) cocktail. Blood sampling via retro-orbital puncture using glass capillaries commenced only after the absence of a pedal withdrawal reflex was confirmed, ensuring the animals did not experience pain or distress. Whole blood samples were maintained in sterile 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes for 60 min, followed by centrifugation at 3500× g for 10 min. The resulting serum supernatant was carefully aliquoted for subsequent analysis.

Collection of feces samples: The mouse was gently restrained with the left hand while the right index finger performed a clockwise circular massage along the abdominal midline to stimulate defecation. Fresh fecal pellets were collected directly into sterile Eppendorf tubes for subsequent E. coli quantification. For other analyses, fecal samples were obtained by housing mice individually in sterile, bedding-free cages to allow for natural excretion.

Organ and luminal content collection: At the end of the treatment, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The colorectum was carefully excised, flushed with sterile 0.85% NaCl to remove luminal contents. One quarter was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for histology, and the remainder was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis. The cecal contents were aseptically collected into sterile Eppendorf tubes following dissection.

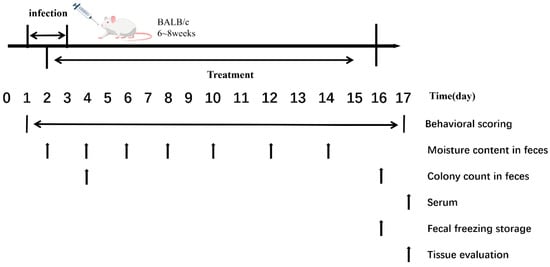

The experimental procedures and sampling time points are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental Procedures and Sampling Time Points.

2.4. Measurement of Body Weight and Fecal Moisture Content

Body weight was recorded daily for all mice. Concurrently, general activity and mental state were monitored, with observations focused on signs such as reduced spontaneous activity, a hunched posture, lethargic behavior, and a coat that was either piloerected or dull and ruffled. Behavioral and mental status were assessed every two days using the scoring criteria provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Behavioral Scoring Criteria.

Fecal samples were collected at fixed intervals every 48 h and assessed for consistency using the scoring criteria detailed in Table 2. The wet weight of fecal samples was measured immediately after collection, followed by oven drying at 70 °C for 20 h to determine the dry weight. The fecal moisture content was calculated as follows:

Moisture Content (%) = [(Wet Weight − Dry Weight)/Wet Weight] × 100%

Table 2.

Fecal Status Score.

2.5. Determination of E. coli Counts in Feces

Fecal samples were collected from all experimental groups at pre-modeling, post-modeling, and post-treatment stages, immediately transferred to sterile 1.5 mL tubes, and weighed. Each sample was homogenized in 1 mL of sterile PBS by vigorous vortexing. After serial 10-fold dilutions, 100 μL aliquots from appropriate dilutions were plated on MacConkey agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Pink colonies (indicating lactose-fermenting E. coli) were counted, and the results were expressed as colony-forming units per gram of fecal sample (CFU/g).

2.6. Observation of Colorectal Tissue Morphology

Following euthanasia, the entire colorectum was carefully excised, and its length was measured using a sterile ruler. Histological processing, including paraffin sectioning, H&E staining, and slide scanning, was performed by ServiceBio Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Colon tissue pathology was evaluated according to established scoring criteria [28], with three random non-continuous fields captured per sample at 200× magnification for microscopic assessment.

2.7. Assessment of Immune Factors

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 were quantified using commercial ELISA kits (TNF-α, Cat. No. KS10484; IL-1β, Cat. No. KS11646; IL-6, Cat. No. KS18212; IL-10, Cat. No. KS10138; Shanghai Keshun Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Samples were appropriately diluted to ensure OD values were within the linear range of the standard curve, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

2.8. Microbial Composition Analysis of Gut Microbiota

Fecal samples were randomly selected from two male and two female mice for microbial composition analysis of gut microbiota. Total microbial genomic DNA was then extracted from these samples using the Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit (Omega, Norcross, GA, USA). The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with barcoded primers under the following conditions: 98 °C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 98 °C/10 s, 50 °C/30 s, 72 °C/30 s; final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products (400–450 bp) were purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Library preparation was conducted using the TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Following successful quality assessment via Qubit quantification and library validation, the libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with a PE250 read length configuration.

Alpha Diversity Analysis: Alpha diversity was assessed to evaluate species composition variation across samples. Clean reads from all samples were processed in QIIME 2 for clustering and taxonomic annotation using the Silva 138 database (https://www.arb-silva.de/, accessed on 28 November 2024) for 16S/18S rRNA gene annotation and the UNITE database (https://unite.ut.ee/, accessed on 28 November 2024) for ITS region annotation. All samples were rarefied to the minimum sequence count to ensure even sequencing depth. Species richness was measured by the Chao1 indices, and community diversity was quantified using the Shannon indices. Rarefaction curves were generated for each index to verify sequencing depth adequacy and microbial community profiling saturation.

Beta Diversity Analysis: To visualize the abundance profiles of each sample across different taxonomic levels, Krona (version 2.8.1) (https://github.com/marbl/Krona/wiki, accessed on 28 November 2024) was used to generate interactive visualizations based on species annotation results and abundance data per sample. Venn diagrams, bar plots, and heatmaps were used to compare species composition across samples and groups. Similarity and dissimilarity in community structure were further examined using dimensionality reduction methods, including Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS). Statistical significance of group differences in microbial composition was assessed using ANOSIM and PERMANOVA (Adonis) tests.

STAMP was employed to identify statistically significant differences in taxonomic abundance across sample groups. LEfSe analysis was conducted to determine microbial biomarkers exhibiting differential abundance among experimental conditions.

2.9. Metabolite Analysis of Feces

Samples were randomly selected from two male and two female mice, and thawed at 4 °C, and mixed with pre-chilled methanol/acetonitrile/water (2:2:1, v/v). After vortexing, the mixtures were sonicated in an ice-water bath for 30 min and subsequently incubated at −20 °C for 10 min, and then centrifuged at 14,000× g, 4 °C for 20 min. The resulting supernatant was vacuum-dried and reconstituted in 100 μL of acetonitrile/water (1:1, v/v) followed by vigorous vortexing for 1 min. After a final centrifugation at 14,000× g, 4 °C for 15 min, the clear supernatant was taken for subsequent analysis.

Samples were separated on an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system equipped with a HILIC column (ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm Column, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) (25 °C, 0.5 mL min−1, 2 µL injection). The chromatographic method employed a binary mobile phase system with water containing 25 mM ammonium acetate and 25 mM ammonia (Mobile Phase A) and acetonitrile (Mobile Phase B), coupled with a multi-step gradient profile. The gradient elution program was set as follows: an isocratic elution with 95% B was maintained from 0 to 0.5 min; followed by a linear gradient from 95% to 65% B over 0.5 to 7 min; then a further linear decrease to 40% B from 7 to 8 min; subsequently, an isocratic elution at 40% B was held from 8 to 9 min; thereafter, a rapid linear increase to 95% B was performed from 9 to 9.1 min; and finally, 95% B was maintained from 9.1 to 12 min for column re-equilibration. Samples were kept at 4 °C in the autosampler and analyzed in random order to minimize signal drift; QC samples were interspersed to monitor system stability.

Following chromatographic separation, the samples were analyzed by mass spectrometry on an AB SCIEX Triple TOF 6600 system (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). Data acquisition was carried out in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All data were tested for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test). Parametric data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test, while non-parametric data were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s test or PERMANOVA. p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multiple comparisons were carried out using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test. The Benjamini-Hochberg FDR procedure controlled for multiple comparisons in high-throughput analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Diarrhea Symptoms

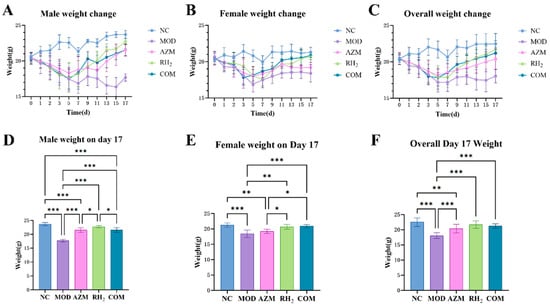

Three days post-infection, a progressive decline in body weight was observed, reaching its nadir on days 5–7, followed by gradual recovery. As shown in Figure 2A,B, male mice exhibited more pronounced weight fluctuations than females. The MOD group showed a fluctuating decline, with the lowest weight on day 15 (19.73% reduction from baseline), ultimately stabilizing at a 13.25% decrease. In contrast, the RH2, AZM, and COM groups reached their lowest weight on day 5 and then began to recover. The RH2 group recovered rapidly, with a final weight of 11.70% above initial weight, while the AZM and COM groups recovered more slowly, finishing at 5.08% and 6.42% above baseline, respectively (Figure 2A,D).

Figure 2.

Body weight changes in mice. (A) Body weight changes in male mice; (B) Body weight changes in female mice; (C) Overall body weight changes; (D) Body weight of male mice on day 17; (E) Body weight of female mice on day 17; (F) Overall body weight on day 17. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, For males and females, n = 5 respectively; for the overall group, n = 10).

While female mice showed relatively smaller weight fluctuations. The MOD group reached the lowest weight on day 5 (18.10% decrease), gradually recovering to a final 10.94% reduction (Figure 2B). The RH2 group began rapid recovery after day 7, ultimately achieving a 0.68% increase relative to initial weight. The COM group showed no significant difference from the RH2 group at the endpoint, with a final weight of 2.25% above baseline (Figure 2E). Notably, the AZM group initially recovered well but slowed later, ultimately resulting in a 6.25% decrease from the initial body weight.

Overall, the MOD group exhibited the slowest weight recovery, followed by the AZM group, while the RH2 group showed the most favorable recovery (Figure 2C). Post-treatment, the COM group demonstrated no significant difference in body weight compared to the RH2 group (Figure 2F).

Additionally, after model establishment, the MOD group exhibited hunched posture, reduced activity and lethargy, huddling and shivering, and dull fur with significant hair loss, which were milder in other groups (Figure S1). The AZM group exhibited fluctuating behavioral and mental states, while the RH2 and COM groups maintained stable recovery.

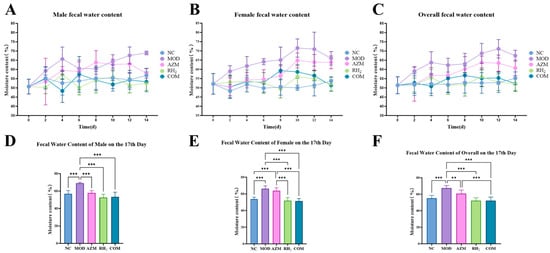

3.2. Changes in Fecal Water Content

Fecal consistency scores and water content analysis (Figure 3 and Figure S2) indicated persistent diarrhea in the MOD group, with maximum scores of 4 and fecal water content of 67.49% (males) and 66.00% (females). The AZM group exhibited recurrent diarrhea, with scores fluctuating between 2–3 points and water content of 57.85% (males) and 63.79% (females). In contrast, the RH2 and COM groups showed significant improvement, with scores reduced to 0–1 by the endpoint and water content of 52.49% (male) and 51.90% (female) in RH2, and 53.33% (male) and 51.34% (female) in COM. Although the COM group initially recovered more slowly, its ultimate fecal water content at the study endpoint was comparable to that of the RH2 group, with no significant difference detected.

Figure 3.

Changes in fecal water content of mice. (A) Male fecal moisture content; (B) Female fecal moisture content; (C) Overall fecal moisture content; (D) Male fecal moisture content on day 17; (E) Female fecal moisture content on day 17; (F) Overall fecal moisture content on day 17. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, For males and females, n = 5 respectively; for the overall group, n = 10).

3.3. Changes in E. coli Counts

After modeling, the MOD group showed a significant increase in fecal E. coli counts. Post-treatment, all three treatments (AZM, RH2, and COM) significantly reduced E. coli load compared to the MOD group. Although the efficacy of the treatments exhibited sex-specific variation, with the most pronounced reduction observed in AZM-treated male mice, the interventions were uniformly effective in suppressing E. coli, as final bacterial loads dropped to sub-normal levels across all groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fecal E. coli counts in mice. (A) Male; (B) Female; (C) Overall mean. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, For males and females, n = 5 respectively; for the overall group, n = 10).

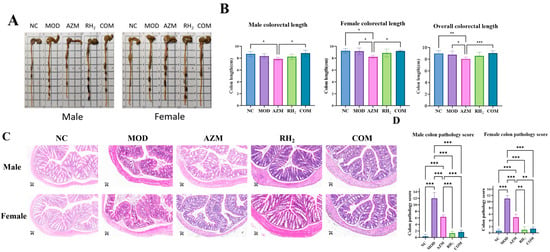

3.4. Analysis of Rectal Pathological Tissues

To evaluate the impact of C. butyricum on colon tissue, colorectal length and histology were assessed to examine mucosal integrity, inflammatory infiltration, and epithelial damage. Measurement of colorectal length showed that long-term azithromycin administration significantly shortened the colorectum, while supplementation with C. butyricum in the COM group effectively mitigated this effect (Figure 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Evaluation of colorectal tissue in mice after treatment. (A) Colorectum length of Mouse; (B) Mean colorectal length. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, For males and females, n = 5 respectively; for the overall group, n = 10); (C) Histology of colon tissue (H&E staining, ×200; Scale bars: 50 μm); (D) Colon pathology score. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, For males and females, n = 5 respectively; for the overall group, n = 10).

Histological analysis revealed that the NC group exhibited intact architecture with densely arranged crypts and abundant goblet cells in the lamina propria. In contrast, the MOD group showed severe disruption: disorganized and irregular crypts, focal erosions, extensive epithelial sloughing, crypt loss replaced by connective tissue, and focal inflammatory aggregates, which confirmed successful establishment of the model. The AZM group displayed inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria with focal organization, along with extensive epithelial detachment and erosion (Figure 5C).

In comparison, both the RH2 and COM groups showed minimal structural damage and mild inflammatory infiltration. As shown in Figure 5D, all treatment groups exhibited significant recovery in colonic injury compared to the MOD group. Notably, C. butyricum intervention in the COM group enhanced epithelial integrity and goblet cell numbers while reducing inflammatory areas relative to the AZM group, highlighting the therapeutic efficacy of the probiotic.

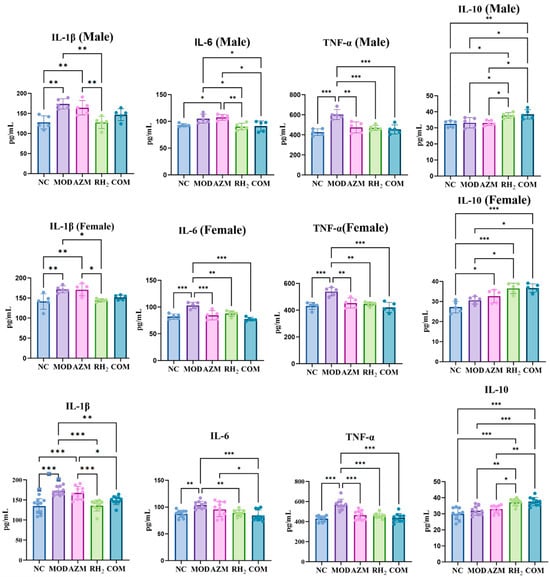

3.5. Measurement of Inflammatory Factor

To evaluate the effects of C. butyricum on cytokine regulation, serum levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines were measured. After treatment, pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) remained elevated in the MOD group, indicating inflammation still persisted in the mice (Figure 6). The AZM group showed partial and sex-dependent cytokine suppression. Specifically, IL-1β in females and IL-6 in males showed no significant changes relative to the MOD group, whereas IL-1β in males, IL-6 in females, and TNF-α were downregulated to varying degrees. In contrast, the COM groups achieved near-complete normalization of pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and a moderate increase in IL-10, which was consistent with the RH2 group. These findings indicate that azithromycin did not compromise the immunomodulatory benefits of C. butyricum in the combination therapy, underscoring the compatibility of this combinatorial approach.

Figure 6.

Serum cytokine levels. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, For males and females, n = 5 respectively; for the overall group, n = 10).

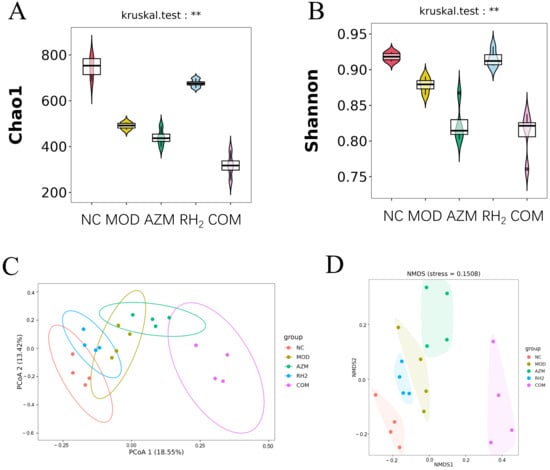

3.6. Analysis of Microbial Community Structure

Alpha and Beta diversity Analysis: To evaluate the effect of C. butyricumin on the gut microbiota of E. coli-induced diarrhea, high-throughput sequencing was performed to assess microbial diversity. As shown in Figure 7A,B, the Chao1 index and Shannon indices were significantly decreased in the MOD, AZM, and COM groups compared to the NC group (p < 0.05, n = 4), indicating that both diarrheal infection and long-term antibiotics use disrupted the microbial diversity. In contrast, the RH2 group exhibited no significant difference from the NC group (p > 0.05, n = 4), suggesting that C. butyricum intervention can effectively restore the alpha diversity to a level similar to healthy controls. In summary, E. coli-induced diarrhea led to gut microbiota dysbiosis and reduced alpha diversity. Treatment with C. butyricum successfully reversed these changes, whereas prolonged antibiotic use decreased species richness and evenness, an effect that was partially mitigated by concurrent C. butyricum supplementation.

Figure 7.

Microbial diversity analysis. (A) Chao 1 index; (B) Shannon index; (C) PCoA; (D) NMDS (** p < 0.01, For males and females, n = 2 respectively; for the overall group, n = 4).

A β-diversity analysis was performed to compare microbial community structure across groups, revealing compositional shifts under different experimental conditions. The Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) plot, based on Bray-Curtis distances, shows clear separation among groups along the first two principal coordinates. The NC and RH2 groups clustered closely in the left section of the plot, indicating that the microbial community in the RH2 group shifted towards a state resembling that of the healthy controls. In contrast, the MOD and AZM groups formed a separate cluster in the upper-right section, demonstrating that both infection and antibiotic treatment significantly disrupted the gut microbiota. Notably, the COM group shifted away from the AZM cluster, suggesting that co-administration of C. butyricum partially counteracted the dysbiotic effects of azithromycin (Figure 7C).

The Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) analysis yielded a consistent grouping pattern with the PCoA results. The spatial distribution of samples in the NMDS plot confirms the same ecological relationships: NC and RH2 groups showed high similarity, MOD and AZM groups formed a distinct dysbiotic cluster, and the COM group exhibited a transitional state toward a healthier microbiota (Figure 7D). The beta diversity analyses consistently demonstrate that C. butyricum intervention effectively promotes a shift towards a healthy gut microbiota structure in mice with infectious diarrhea. While azithromycin treatment resulted in significant dysbiosis similar to the model group, the concurrent administration of C. butyricum in the COM group partially mitigated these adverse effects, supporting the potential of probiotic-antibiotic combination therapy in managing antibiotic-associated microbial imbalances.

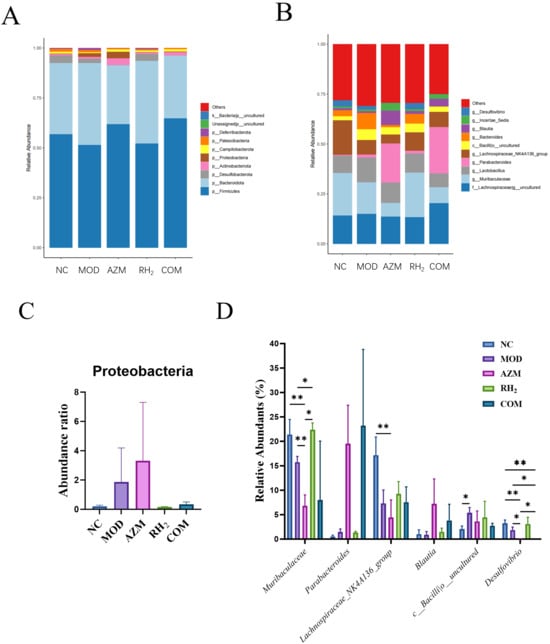

Species analysis of the intestinal microbiota: Based on taxonomic annotation, the top 10 most abundant species per group were selected to generate stacked bar charts of relative species abundance. At the phylum level, the eight most abundant taxa across all groups were p_Firmicutes, p_Bacteroidota, p_Desulfobacterota, p_Actinobacteriota, p_Proteobacteria, p_Campilobacterota, p_Patescibacteria, and p_Deferribacterota. p_Firmicutes, p_Bacteroidota, and p_Desulfobacterota constituted the dominant phyla, collectively accounting for over 90% of total abundance (Figure 8). The MOD and AZM groups showed increased relative abundance of p_Proteobacteria, a phylum containing numerous opportunistic pathogens, suggesting that E. coli colonization disrupted gut microbial structure and promoted expansion of harmful bacteria. Similarly, prolonged azithromycin use induced dysbiosis and favored pathogenic proliferation. In contrast, the COM group exhibited no increase in p_Proteobacteria, indicating that C. butyricum intervention effectively suppressed pathogenic growth. Compared to other groups, the AZM and COM groups had higher abundance of p_Actinobacteriota but lower proportions of p_Desulfobacterota and p_Deferribacterota. The MOD group showed reduced p_Desulfobacterota and elevated p_Deferribacterota relative to the NC group. Overall, the RH2 group displayed a microbial composition closest to the NC group, underscoring the efficacy of C. butyricum in restoring gut microbiota balance.

Figure 8.

Changes in abundance of mouse gut microbiota. (A) Phylum-level relative abundance; (B) Genus-level relative abundance; (C) Proteobacteria relative abundance; (D) Abundance of specific genera. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

At the genus level, the dominant bacterial taxa included g__uncultured_f__Lachnospiraceae, g_Muribaculaceae, g_Lactobacillus, g_Parabacteroides, and g_Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group (Figure 8). Compared to the MOD group, the RH2 group showed a significant increase in the abundance of g_Muribaculaceae (p < 0.05, n = 4), reaching levels comparable to the NC group, while the AZM (p < 0.01, n = 4) and COM groups exhibited reductions. g_Muribaculaceae, a family within the Bacteroidota, ferments complex polysaccharides to produce acetate and propionate, providing energy to the host [29]. It also supports gut barrier function and competitively inhibits pathogens, contributing to microecological balance [30]. The RH2 and COM groups showed increased abundance of g_Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group compared to the MOD group, whereas the AZM group showed a decrease. Lachnospiraceae produce butyrate, which is critical for maintaining barrier integrity, anti-inflammatory responses, and immune regulation [31]. They also inhibit pathogens such as E. coli and Salmonella through niche competition and nutrient exclusion. In addition, g_Bacteroides abundance was reduced in the RH2, AZM, and COM groups relative to the MOD group. Notably, the AZM and COM groups displayed higher abundances of g_Parabacteroides and g_Blautia, along with reduced levels of uncultured Bacilli (c_Bacilli_uncultured) and g_Desulfovibrio (p < 0.05, n = 4). Both g_Blautia and g_Parabacteroides have been reported to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines and maintain intestinal immune homeostasis [32,33], whereas low g_Desulfovibrio levels help mitigate inflammation, modulate immunity, and protect barrier function [34].

Overall, treatment with C. butyricum promoted the proliferation of beneficial bacteria in mice with E. coli-induced infectious diarrhea, resulting in a microbial composition similar to that of healthy mice. Although long-term antibiotic use significantly altered microbiota abundance, co-administration of C. butyricum positively influenced the structure of dominant intestinal flora.

Analysis of Gut Microbiota Species Differences: To further identify microbial taxa contributing to community differences, LEfSe (Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size) was employed to analyze significantly differential microbial biomarkers across comparison groups. As shown in Figure S3, the MOD group was characterized by microbial biomarkers predominantly associated with pro-inflammatory functions, including genera such as g_Alistipes, g_Mucispirillum, and g_Gemella. The AZM group exhibited significant gut microbiota dysbiosis, marked by substantial enrichment of opportunistic pathogens such as g_Enterorhabdus, g_Escherichia-Shigella, and g_Erysipelatoclostridium. The co-occurrence of facultative anaerobes (e.g., g_Enterococcus, g_Streptococcus) and strict anaerobes (e.g., g_Anaerorhabdus, g_Anaerosporomusa) suggests potential intestinal hypoxia or mucosal injury. In contrast, the RH2 group exhibited a significant enrichment of butyrate-producing bacteria, including g_Roseburia, g_Lachnospiraceae_UCG-001, and g_Ruminococcaceae, which, together with g_Muribaculaceae, established a symbiotic microbial network primarily composed of short-chain fatty acid-producing and dietary fiber-degrading taxa. Following C. butyricum intervention, the COM group exhibited a markedly shifted biomarker profile. The community was dominated by probiotics conferring metabolic and barrier-protective functions, such as g_Parabacteroides and g_Lachnospiraceae_FCS020_group. The detection of genera such as g_Staphylococcus and g_Erysipelatoclostridium is noted; however, considering the community dominated by beneficial bacteria and a marked antidiarrheal effect, their presence likely reflects a constrained ecological niche within a therapeutically restructured and functionally resilient gut microbiome.

3.7. Fecal Metabolomic Analysis in Mice

To further compare the effects of antibiotics on the metabolic function of C. butyricum, untargeted metabolomics was performed on mouse fecal samples. A total of 66, 38, and 77 differential metabolites were identified in the AZM, RH2, and COM groups, respectively (Figure S4). Comparative analysis revealed that the COM group shared 15 differential metabolites with the RH2 group and 33 with the AZM group (Figure S5). Eight metabolites were common to all three groups, namely 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate, cholesteryl sulfate, DL-normetanephrine, hydrocortisone, indoxyl sulfate, phenyllactic acid, sarcosine, and taurochenodeoxycholate (Figure S6), suggesting their potential association with the pathogenesis of infectious diarrhea. Butyrate, a primary metabolite of C. butyricum, is fundamental to gut health, influencing epithelial barrier function, immune regulation, and energy metabolism. As a key energy source for colonic epithelial cells, fecal butyrate levels reflect a dynamic balance between microbial production and host utilization, which may result in a non-significant net change in fecal concentration. Given the central role of butyrate as the primary functional metabolite of C. butyricum, its levels were analyzed as a pre-specified target. The relative abundance of butyric acid and shared differential metabolites is shown in Figure S6.

Metabolic pathway enrichment analysis of differential metabolites from the AZM, RH2, and COM groups was performed using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 to compare alterations in key metabolic pathways across therapeutic interventions. Pathways with p < 0.05 and the highest enrichment ratios were prioritized for analysis. Results revealed that the AZM group was primarily associated with steroid hormone biosynthesis and butanoate metabolism. The RH2 group exhibited significant enrichment in vitamin B6 metabolism and lysine degradation. In contrast, the COM group showed concurrent enrichment in butanoate metabolism, vitamin B6 metabolism, and arginine and proline metabolism (Figure S7), reflecting a broader metabolic restoration profile.

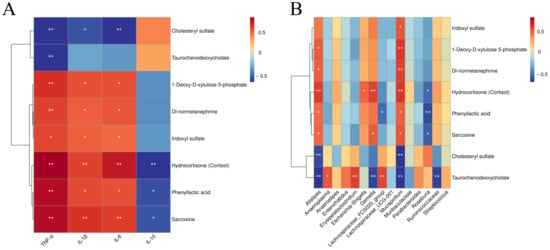

Cluster-based correlation analysis was performed between shared differential metabolites of the AZM, RH2, and COM groups and serum inflammatory cytokine levels or biomarker microbiota. As shown in Figure 9, metabolites including 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate, DL-normetanephrine, indoxyl sulfate, hydrocortisone, phenyllactic acid, and sarcosine showed positive correlations with pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α), with hydrocortisone, phenyllactic acid, and sarcosine also negatively correlated with the anti-inflammatory IL-10. These metabolites were positively associated with pathogenic genera such as Alistipes, Mucispirillum, Gemella, and Escherichia-Shigella, and negatively correlated with beneficial bacteria, including Roseburia and Lachnospiraceae_FCS020_group. In contrast, cholesteryl sulfate was negatively correlated with all three pro-inflammatory cytokines and pathogenic genera (Alistipes and Mucispirillum). Taurochenodeoxycholate showed negative correlations with TNF-α and several pathogens (Alistipes, Gemella, Mucispirillum, and Ruminococcaceae), but positive correlations with beneficial taxa such as Anaerosporomusa, Erysipelatoclostridium, and Lachnospiraceae_FCS020_group. Consequently, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate, DL-normetanephrine, indoxyl sulfate, hydrocortisone, phenyllactic acid, sarcosine, cholesteryl sulfate, and taurochenodeoxycholic acid were identified as key differential metabolites in infectious diarrhea. Their regulation patterns (up/down) were associated with gut microbiota such as Alistipes, Mucispirillum, and Roseburia.

Figure 9.

Heatmap of fecal metabolite correlations with serum cytokines and signature microbiota. (A) Correlation between metabolites and cytokines; (B) Correlation between metabolites and microbiota. Strength (Spearman’s ρ value) and significance of correlations are shown as colors in shades (red, positive correlation; blue, negative correlation). The values above/below zero represent positive/negative correlations. Significant correlations are noted by * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The human gut harbors over a thousand microbial species, forming a complex ecological community [35]. Through interactions with the neural, endocrine, and immune systems, gut microbiota significantly influences host health [36]. Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms that confer a health benefit on the host when administered in adequate amounts [37], improve health by restoring intestinal microbial balance or exerting other functional properties [38].

In this study, a diarrhea model was established by infection with E. coli to evaluate the impact of azithromycin on the therapeutic efficacy of C. butyricum. The results demonstrated that while azithromycin alleviated diarrheal symptoms in mice, the recovery was unstable and accompanied by shortened colorectal length, persistent inflammatory infiltration, and significant epithelial cell damage and shedding in the mucosal layer. After co-administration with C. butyricum, although azithromycin caused intermittent fluctuations in the diarrheal recovery process, the ultimate therapeutic outcomes at the study endpoint were comparable to those of C. butyricum monotherapy. These findings indicated that C. butyricum can alleviate the side effects caused by long-term use of antibiotics, such as weight loss and shortened colon length, which was consistent with the results reported by Hagihara et al. [39]. Comparative treatment of male and female mice showed that sex-based differences were largely restricted to weight response under C. butyricum and combination therapy, with no other significant sex-specific variations observed. In contrast, azithromycin monotherapy caused marked sexual dimorphism in fecal E. coli loads and inflammatory cytokine expression, likely due to sex-specific drug metabolism and hormone-mediated immunomodulation. Ultimately, however, the final therapeutic outcome was not sex-dependent.

High-throughput sequencing of the intestinal microbiota of mice showed that diarrhea caused by E. coli infection resulted in a decrease in diversity. The MOD group exhibited a distinct microbial profile characterized by significant enrichment of Alistipes, Mucispirillum, and Gemella as indicator genera. Alistipes drives disease variability in DSS colitis models by promoting weight loss, intestinal inflammation, and reduced survival [40]. Mucispirillum serves as a key indicator of dysbiosis, reflecting a detrimental feedback loop between mucus layer degradation and microbial disruption [41]. Gemella, an opportunistic pathogen, exacerbates inflammation through biofilm formation under immune impairment or dysbiosis [42]. In concert with E. coli, these genera collectively impair the intestinal barrier integrity and mucosa homeostasis, thereby accelerating inflammatory processes.

The broad-spectrum antibacterial action of azithromycin in the AZM group severely suppressed Gram-positive bacteria, intensifying competition for colonization niches between opportunistic pathogens and antibiotic-resistant strains. Erysipelatoclostridium and Escherichia are markedly enriched in the gut of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients and serve as marker bacteria for IBD-associated dysbiosis. Escherichia species can produce pro-inflammatory polysaccharides and mucin-degrading trans-sialidases that disrupt the intestinal mucosal barrier and exacerbate inflammation [43]. Ning et al. [44] demonstrated that increased gut abundance of Streptococcus correlated with elevated systemic inflammatory markers (hs-CRP, neutrophil count, and white blood cell count), suggesting a role in chronic inflammation. Tang et al. further showed that heightened levels of lysophosphatidylcholine, which promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine release and epithelial barrier damage, in colitis mice feces were positively associated with the abundance of Escherichia and Enterorhabdus [45]. In contrast, while opportunistic pathogens competed for colonization sites, anaerobic gut bacteria such as Anaerostipes and Anaeroplasma actively counteracted inflammation. Anaerostipes, encompassing key butyrate-producing species, synthesizes butyrate by metabolizing sugars, acetate, and lactate, thereby fortifying the intestinal mucosal barrier, modulating immune responses, and suppressing inflammatory pathways [46]. Anaeroplasma in turn, exerts anti-inflammatory effects through TGF-β induction, which enhances gut barrier integrity by promoting mucosal IgA production [47].

In the RH2 group, C. butyricum promoted the colonization of diverse butyrate-producing bacteria. Butyrate enhanced immune regulation by facilitating regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation, suppressing Th17 cells and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-17, IFN-γ), and activating G protein-coupled receptors to modulate energy metabolism and strengthen intestinal barrier function [48]. Among these bacteria, Butyricimonas functioned as a protective agent through its production of butyrate and isobutyrate [49], while Roseburia species served as major butyrate producers via the butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase pathway, aided by efficient dietary fiber utilization [48]. Ruminococcaceae primarily degraded inulin, pectin derivatives, and uronic acids, whereas Lachnospiraceae metabolized starch, arabinoxylan, and inulin—both families generated butyrate through the butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase pathway [50]. Muribaculaceae, which colonize the mucus layer via mucin glycan symbiosis, produced short-chain fatty acids from dietary fiber. Their abundance declined in IBD animal models due to mucosal damage, but rebounded following effective intervention [29]; the elevated Muribaculaceae levels in the RH2 group thus reflected successful mucosal recovery. Similarly, intervention with C. butyricum in the COM group promoted the colonization of Lachnospiraceae and Parabacteroides. As crucial butyrate producers, Lachnospiraceae exert anti-inflammatory effects and nourish colonic epithelial cells by producing butyrate, thereby promoting the expression of tight junction proteins and maintaining the intestinal barrier [51].

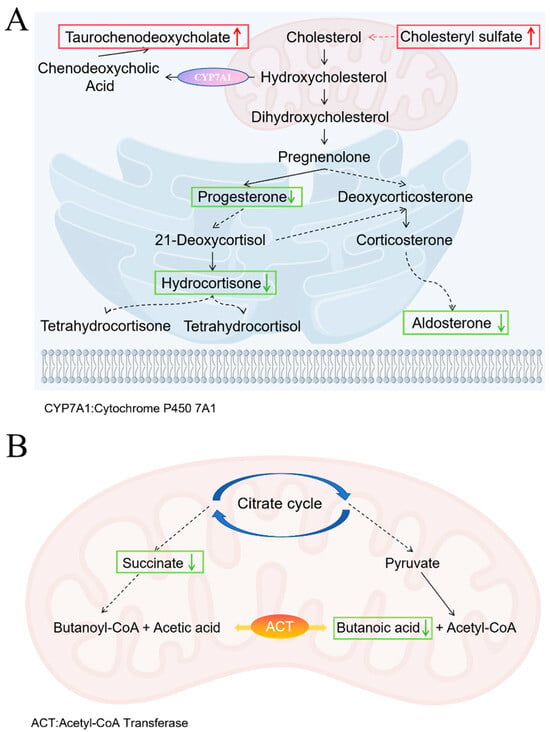

Untargeted metabolomics analysis revealed that after azithromycin treatment, differential metabolites identified in mouse fecal samples were enriched in the steroid hormone biosynthesis and butyrate metabolic pathways. Within the steroid hormone biosynthesis pathway, upstream metabolites (including cholesteryl sulfate and taurochenodeoxycholic acid) showed significant upregulation, while key intermediate and terminal products (such as progesterone, aldosterone, hydrocortisone) were consistently downregulated (Figure 10A). This metabolic profile suggests a potential impairment at a critical step in steroidogenesis. Consequently, the downstream biosynthesis pathways are suppressed. Under intestinal inflammatory conditions, hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase 2B1 (SULT2B1) expression is upregulated, catalyzing cholesterol conversion to cholesteryl sulfate. Elevated cholesteryl sulfate binds to the lysosomal protein NPC2 and competitively inhibits cholesterol transport from lysosomes to the cytoplasm, leading to the endoplasmic reticulum cholesterol levels decereased. This depletion triggers a cellular “cholesterol hunger” signal, which activates the SREBP2-mediated de novo cholesterol synthesis pathway. The accelerated cholesterol production supplies substrates for cell membrane formation, thereby maintaining cellular and tight junction integrity, promoting proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, and facilitating tissue repair [52]. Meanwhile, cholesterol is converted in the liver by the enzyme CYP7A1 into primary bile acids such as chenodeoxycholic acid. These primary bile acids then conjugate with glycine or taurine to form conjugated bile acids. Under normal conditions, the ileal reabsorption of bile acids is highly efficient; however, when ileal absorption is impaired, they spill into the colon, inhibit water and electrolyte uptake, stimulate secretion, and thereby trigger diarrhea [53]. Thus, although the rise in cholesterol sulfate in the AZM group could promote barrier repair, the disturbed bile-acid metabolism still sustains diarrheal symptoms. In butyrate metabolism, both succinate and butyrate were markedly down-regulated (Figure 10B), because azithromycin broadly suppresses Gram-positive bacteria and thereby weakens the acetyl-CoA transferase-dependent pathway [54]. The resulting butyrate deficiency further compromises barrier function [55], mirroring the metabolic profile observed in ulcerative colitis [56]. These results indicate that, while exerting its antibacterial effect, azithromycin severely disrupts microbial community structure and metabolic homeostasis.

Figure 10.

Metabolic Pathway Changes in AZM group. (A) Steroid hormone biosynthesis pathway; (B) Butyrate metabolic pathways. Upward red arrows indicate upregulation, and downward green arrows indicate downregulation. The dashed arrow indicates a multi-step pathway.

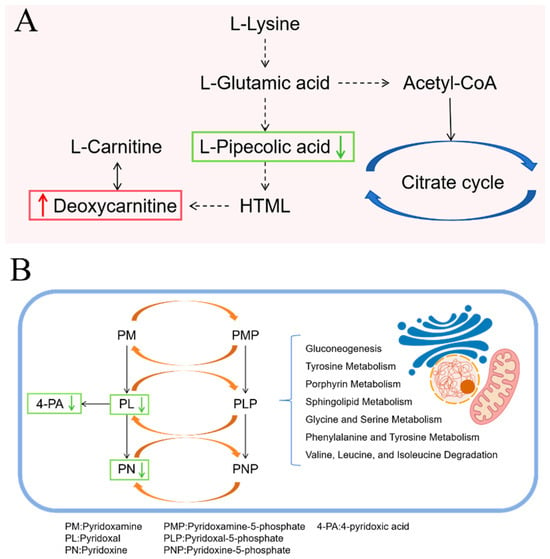

In the RH2 group treated with C. butyricum, differential metabolites from mouse feces were enriched in the lysine degradation and vitamin B6 metabolic pathways. In lysine degradation, upstream L-pipecolic acid was downregulated while deoxycarnitine increased, indicating a shift toward enhanced carnitine synthesis (Figure 11A). Carnitine plays a key role in cellular energy balance and tissue metabolism by promoting fatty acid oxidation to meet elevated energy demands during wound healing. This metabolic shift reduces reliance on glucose, prevents lactate-induced acidification, stabilizes cellular function, and supports energy-intensive processes such as cell proliferation, collagen synthesis, and angiogenesis. Additionally, carnitine downregulates pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), promotes anti-inflammatory IL-10 release, and reduces oxidative stress to mitigate tissue damage and accelerate repair [57]. In the vitamin B6 metabolism pathway, levels of pyridoxal, pyridoxine, and 4-pyridoxic acid decreased (Figure 11B). Vitamin B6 serves as an essential cofactor in numerous enzymatic reactions. While vitamin B6 deficiency has been shown to impair lysine degradation and arginine synthesis [58], the well-functioning lysine pathway observed in this study, together with reduced levels of inactive vitamin B6 metabolites, suggests that C. butyricum promotes the conversion of inactive forms into active pyridoxal-5′-phosphate. This enhancement likely supports metabolic and functional recovery of damaged intestinal mucosal cells [59].

Figure 11.

Metabolic Pathway Changes in RH2 group. (A) Lysine degradation pathway; (B) Vitamin B6 metabolic pathways. Upward red arrows indicate upregulation, and downward green arrows indicate downregulation.

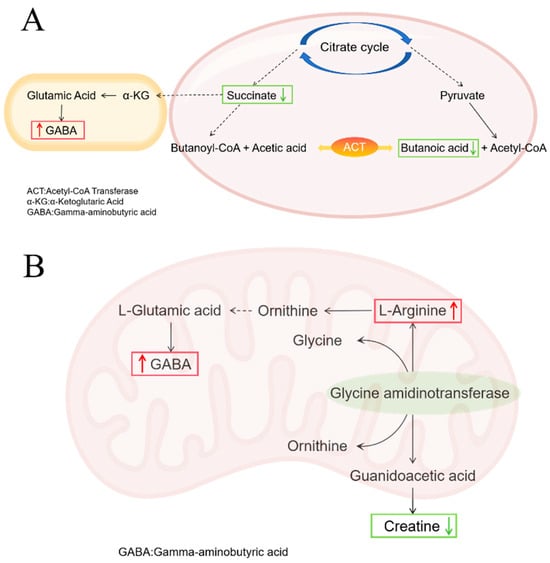

In the COM group, the relative abundance of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) within the butyrate metabolism pathway was upregulated compared to the MOD group (Figure S4C). This suggests that C. butyricum supplementation may have partially shifted this pathway towards activation. Notably, the GABA biosynthesis branch was significantly promoted despite low overall butyrate levels. The concurrent increase in arginine and GABA in the arginine and proline metabolism pathway, alongside a decrease in creatine, points to a potential synergistic support for GABA production (Figure 12B). Given the well-documented role of GABA in reducing intestinal oxidative damage and inflammation [60], its upregulation is a plausible contributor to the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6). Furthermore, GABA’s ability to enhance tight junction protein expression and alleviate oxidative stress probably underlies the improved intestinal barrier integrity observed in our study. Arginine, as a precursor for nitric oxide and polyamines, plays a pivotal role in enhancing mucosal blood flow, promoting epithelial cell proliferation, and facilitating tissue repair [61]. Its immunomodulatory functions likely contributed to the resolution of inflammation [62,63]. The co-upregulation of arginine and GABA suggests a coordinated metabolic response: while GABA provides anti-inflammatory and neuromodulatory benefits, arginine drives the structural regeneration of the damaged intestinal epithelium. This synergistic action effectively addresses both the inflammatory response and the physical barrier damage caused by the infection. The vitamin B6 metabolic pathway in the COM group remained consistent with that observed in the RH2 group.

Figure 12.

Metabolic Pathway Changes in COM Group. (A) Butyric acid metabolic pathway; (B) Arginine and proline metabolism pathway. Upward red arrows indicate upregulation, and downward green arrows indicate downregulation.

Furthermore, correlation analysis indicated that two differential metabolites, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate and indoxyl sulfate, which play key roles in infectious diarrhea, are derived from pathogenic bacterial metabolism. Their elevated levels were directly linked to increased abundance of Alistipes and Mucispirillum. 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate is a metabolic intermediate synthesized by pathogens such as E. coli and Mycobacterium tuberculosis via the methylerythritol phosphate pathway. By supporting pathogen proliferation, it indirectly compromises intestinal health and exacerbates infection [64]. Indoxyl sulfate production relies on the microbial metabolism of tryptophan by pathogens including E. coli. The expansion of these toxin-producing bacteria leads to accumulation of uremic toxins, resulting in tissue injury through pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative mechanisms [65]. Prolonged elevation of hydrocortisone may heighten infection risk by suppressing Th1 immune responses and impairing gut health [66]. In contrast, Roseburia has been shown to effectively attenuate abnormal hydrocortisone increases.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that C. butyricum exhibits a strong therapeutic effect in a mouse model of E. coli-induced infectious diarrhea. While azithromycin effectively suppressed pathogenic E. coli, its use was associated with significant disruptions to intestinal microbiota composition and metabolic homeostasis, potentially delaying symptomatic and histological recovery. Notably, when administered in combination with azithromycin, C. butyricum retained considerable efficacy, ameliorating dysbiosis and promoting recovery, though its regulatory impact on the gut homeostasis appeared partially attenuated compared to monotherapy. These findings suggest that C. butyricum can remain functionally active even during antibiotic exposure. Future studies should focus on directly quantifying C. butyricum colonization dynamics using strain-specific approaches to validate its survival and activity in vivo. These results support the potential clinical value of supplementing with C. butyricum during antibiotic treatment to mitigate microbiota-related side effects. Further investigation is needed to determine whether continuing probiotic administration after antibiotic cessation could enhance long-term microbial stability and clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms13122812/s1, Figure S1: Scoring of Behavioral States; Figure S2: Fecal Status Scoring of Mice; Figure S3: LEfSe and STAMP analysis results; Figure S4: Heatmap of Differential Metabolite Abundance in Mouse Feces; Figure S5: Differential Metabolite Venn Diagram; Figure S6: Relative abundance of shared differential metabolites and Butanoic acid; Figure S7: Pathway enrichment analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z., C.-Y.W. and Y.-X.Z.; methodology, Y.-X.Z., C.-Y.W., M.-Y.Z. and H.-Y.Z.; investigation, Y.-M.Y. and Y.-X.Z.; data curation, Y.-M.Y. and M.-Y.Z.; writing—original draft, C.-Y.W. and Y.-X.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.-Y.W. and Y.-X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Shenyang Pharmaceutical University Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol code SYPU-IACUC-S2024-1016-114, 16 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Lu Zhang was employed by the company Hangzhou Grand Biologic Pharmaceutical Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ramirez:, J.; Guarner, F.; Bustos Fernandez, L.; Maruy, A.; Sdepanian, V.L.; Cohen, H. Antibiotics as major disruptors of gut microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 572912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Feng, S.; Huo, F.; Liu, H. Effects of four antibiotics on the diversity of the intestinal microbiota. Microbiol. Spectrum 2022, 10, e01904-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, S.R.; Mahmud, B.; Dantas, G. Antibiotic perturbations to the gut microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Bian, H.; Yu, S.; Huang, L.; Ma, W. Complex probiotics alleviate ampicillin-induced antibiotic-associated diarrhea in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1156058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Paek, J.J.; Lee, Y. Antimicrobial resistance of seventy lactic acid bacteria isolated from commercial probiotics in Korea. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.-L.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Fang, Y.; Wang, J.; Tang, L.-L. Effect of the short-term use of fluoroquinolone and β-lactam antibiotics on mouse gut microbiota. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 4547–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianiro, G.; Tilg, H.; Gasbarrini, A.J.G. Antibiotics as deep modulators of gut microbiota: Between good and evil. Gut 2016, 65, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yi, Z.; Liao, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Diversity within the species Clostridium butyricum: Pan-genome, phylogeny, prophage, carbohydrate utilization, and antibiotic resistance. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Pei, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Feng, L.; Li, G.; Li, K. Pangenome analyses of Clostridium butyricum provide insights into its genetic characteristics and industrial application. Genomics 2024, 116, 110855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosa, G.; Scalfaro, C.; Di Bonito, P.; Vitale, M.; Aureli, P. Identification of novel linear megaplasmids carrying a ß-lactamase gene in neurotoxigenic Clostridium butyricum type E strains. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-M.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.-X. Survival and Morphological Changes of Clostridium butyricum Spores Co-Exposed to Antibiotics and Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids: Implications for Antibiotic Stewardship. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, M.; Yamashita, R.; Matsumoto, A.; Mori, T.; Kuroki, Y.; Kudo, H.; Oka, K.; Takahashi, M.; Nonogaki, T.; Yamagishi, Y. The impact of Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI 588 on the murine gut microbiome and colonic tissue. Anaerobe 2018, 54, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, M.; Yamashita, R.; Matsumoto, A.; Mori, T.; Inagaki, T.; Nonogaki, T.; Kuroki, Y.; Higashi, S.; Oka, K.; Takahashi, M. The impact of probiotic Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI 588 on murine gut metabolic alterations. J. Infect. Chemother. 2019, 25, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.; Kaur, P. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms in bacteria: Relationships between resistance determinants of antibiotic producers, environmental bacteria, and clinical pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Ju, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Sun, S. Clostridium butyricum ameliorates Salmonella enteritis induced inflammation by enhancing and improving immunity of the intestinal epithelial barrier at the intestinal mucosal level. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Song, M.; Lv, P.; Hao, G.; Sun, S. Effects of Clostridium butyricum on intestinal environment and gut microbiome under Salmonella infection. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Peng, X.-Y.; Gao, B.; Wei, Q.-L.; Xiang, R.; Yuan, M.-G.; Xu, Z.-H. The effect of Clostridium butyricum on gut microbiota, immune response and intestinal barrier function during the development of necrotic enteritis in chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Xu, B.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q.; Deng, W.; Wei, F.; Ma, H.; Fu, C.; Wang, G.; Li, S. Effects of Clostridium butyricum on growth performance, gut microbiota and intestinal barrier function of broilers. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 777456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Ma, X. Clostridium butyricum alleviates weaned stress of piglets by improving intestinal immune function and gut microbiota. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 135014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Sui, X.; Liu, Y.; Wei, X.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Ye, W.; Gao, B. The anti-inflammatory effect and mucosal barrier protection of Clostridium butyricum RH2 in ceftriaxone-induced intestinal dysbacteriosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 647048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, H.; Chen, M.; Ni, M.; Guo, C.; Wan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cai, H. Novel mechanism of Clostridium butyricum alleviated coprophagy prevention-induced intestinal inflammation in rabbit. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 130, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Qian, Y.; Peng, X.; Qin, C.; Ren, H.; Du, J.; Huang, C.; Pan, M.; Ou, W. Effects of Dietary Clostridium butyricum on Growth and Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Functions of Juvenile Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Jiang, L.; He, W.; Han, D.; Yang, X.; Wu, L.; Zhong, H. Clostridium butyricum, a future star in sepsis treatment. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1484371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Xie, J.; Guo, Q.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Leng, T.; Li, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, W.; Su, X. Clostridium butyricum isolated from giant panda can attenuate dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1361945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xu, H.; Li, J.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhu, M.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Nie, Y. Clostridium butyricum-induced balance in colonic retinol metabolism and short-chain fatty acid levels inhibit IgA-related mucosal immunity and relieve colitis developments. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 298, 128203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Shen, Q.; Lyu, W.; Lv, L.; Wang, W.; Yu, M.; Yang, H.; Tao, S.; Xiao, Y. Clostridium butyricum and its derived extracellular vesicles modulate gut homeostasis and ameliorate acute experimental colitis. Microbiol. Spectrum 2022, 10, e0136822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, D.; Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, X. The combination of Clostridium butyricum and Akkermansia muciniphila mitigates DSS-induced colitis and attenuates colitis-associated tumorigenesis by modulating gut microbiota and reducing CD8+ T cells in mice. mSystems 2025, 10, e01567-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlen, S.; Ramming, I.; Pils, M.C.; Koeppel, M.; Glaser, J.; Leong, J.; Flieger, A.; Stecher, B.; Dersch, P. Identification of antibiotics that diminish disease in a murine model of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Akbar, M.T.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhi, L.; Shen, Q. Exploration of the muribaculaceae family in the gut microbiota: Diversity, metabolism, and function. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C.; Nagarajan, N.; Gan, Y.-H. Short-chain fatty acids of various lengths differentially inhibit Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacteriaceae species. mSphere 2024, 9, e00781-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, Y.; Liu, P.; Mo, R.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y. Oat β-(1 → 3, 1 → 4)-d-glucan alleviates food allergy-induced colonic injury in mice by increasing Lachnospiraceae abundance and butyrate production. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 344, 122535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Páez, A.; Gomez del Pugar, E.M.; López-Almela, I.; Moya-Pérez, Á.; Codoñer-Franch, P.; Sanz, Y. Depletion of Blautia species in the microbiota of obese children relates to intestinal inflammation and metabolic phenotype worsening. mSystems 2020, 5, e00857-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Yi, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Lü, X. Roles of intestinal Parabacteroides in human health and diseases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Huang, D.; Sun, Z.; Chen, X. Effects of intestinal Desulfovibrio bacteria on host health and its potential regulatory strategies: A review. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 284, 127725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajewska, H.; Scott, K.P.; de Meij, T.; Forslund-Startceva, S.K.; Knight, R.; Koren, O.; Little, P.; Johnston, B.C.; Łukasik, J.; Suez, J.; et al. Antibiotic-perturbed microbiota and the role of probiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagihara, M.; Kuroki, Y.; Ariyoshi, T.; Higashi, S.; Fukuda, K.; Yamashita, R.; Matsumoto, A.; Mori, T.; Mimura, K.; Yamaguchi, N. Clostridium butyricum modulates the microbiome to protect intestinal barrier function in mice with antibiotic-induced dysbiosis. iScience 2020, 23, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, S.C.; Clare, S.; Beresford-Jones, B.S.; Harcourt, K.; Notley, G.; Stares, M.D.; Kumar, N.; Soderholm, A.T.; Adoum, A.; Wong, H. Identification of gut microbial species linked with disease variability in a widely used mouse model of colitis. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, D.; Schwab, C.; Milinovich, G.; Reichert, J.; Ben Mahfoudh, K.; Decker, T.; Engel, M.; Hai, B.; Hainzl, E.; Heider, S. Phylotype-level 16S rRNA analysis reveals new bacterial indicators of health state in acute murine colitis. ISME J. 2012, 6, 2091–2106. [Google Scholar]

- García López, E.; Martín-Galiano, A.J. The versatility of opportunistic infections caused by Gemella isolates is supported by the carriage of virulence factors from multiple origins. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawki, A.; McCole, D.F. Mechanisms of intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by adherent-invasive Escherichia coli. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 3, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, C.; Wang, Z.; Xuan, B.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yan, Y. Microbiome and metabolome features in inflammatory bowel disease via multi-omics integration analyses across cohorts. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, W.; Hong, G.; Duan, C.; Zhu, S.; Tian, Y.; Han, C.; Qian, W.; Lin, R.; Hou, X. Gut microbiota-mediated lysophosphatidylcholine generation promotes colitis in intestinal epithelium-specific Fut2 deficiency. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021, 28, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Xie, L.-S.; Lian, S.; Li, K.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.-Z.; Hu, S.; Liu, S.-J.; Liu, C.; He, Z. Anaerostipes hadrus, a butyrate-producing bacterium capable of metabolizing 5-fluorouracil. mSphere 2024, 9, e00816-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Davelaar, N.; Otten-Mus, A.; Asmawidjaja, P.; Hazes, J.; Baeten, D.; Vis, M.; Bisoendial, R.; Lubberts, E. P103/O14 Interleukin-17 is produced by CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells after TCR activation in synovial fluid of psoriatic arthritis patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019, 78, A45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, K.; Ma, K.; Luo, W.; Shen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, M.; Tong, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Roseburia intestinalis: A beneficial gut organism from the discoveries in genus and species. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 757718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Fu, Y.; Cao, W.-T.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, Z.; Jia, X.; Liu, C.-Y.; Lin, H.-R.; Zhong, H. Gut microbiome, cognitive function and brain structure: A multi-omics integration analysis. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Li, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, W.; Liu, H.; Li, F. Therapeutic potential of Parabacteroides distasonis in gastrointestinal and hepatic disease. MedComm 2024, 5, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ma, R.; Ju, Y.; Song, X.; Niu, B.; Hong, W.; Wang, R.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Cholesterol sulfate alleviates ulcerative colitis by promoting cholesterol biosynthesis in colonic epithelial cells. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.S.; Wong, B.S.; Camilleri, M.; Odunsi–Shiyanbade, S.T.; McKinzie, S.; Ryks, M.; Burton, D.; Carlson, P.; Lamsam, J.; Singh, R. Chenodeoxycholate in females with irritable bowel syndrome-constipation: A pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenetic analysis. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 1549–1558.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, K.E.; Pfaffinger, J.M.; Ryznar, R. The interplay between gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and implications for host health and disease. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2393270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, P.; Ma, J.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Dong, W. Exploring the butyrate metabolism-related shared genes in metabolic associated steatohepatitis and ulcerative colitis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzosa, E.A.; Sirota-Madi, A.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Fornelos, N.; Haiser, H.J.; Reinker, S.; Vatanen, T.; Hall, A.B.; Mallick, H.; McIver, L.J. Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 293–305, Correction in Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.L.; Simmons, P.A.; Vehige, J.; Willcox, M.D.; Garrett, Q. Role of carnitine in disease. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayengbam, S.; Chleilat, F.; Reimer, R.A. Dietary vitamin B6 deficiency impairs gut microbiota and host and microbial metabolites in rats. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueland, P.M.; McCann, A.; Midttun, Ø.; Ulvik, A. Inflammation, vitamin B6 and related pathways. Mol. Asp. Med. 2017, 53, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Li, D.; Wang, L.; Lan, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y. Activation of GABABR attenuates intestinal inflammation by reducing oxidative stress through modulating the TLR4/MyD88/NLRP3 pathway and gut microbiota abundance. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhaluk, N.; Tkaczenko, H. L-Arginine and Nitric Oxide in Vascular Regulation—Experimental Findings in the Context of Blood Donation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, G.; Shahid, M.S.; Gan, L.; Fan, H.; Lv, Z.; Yan, S.; Guo, Y. Dietary l-arginine supplementation ameliorates inflammatory response and alters gut microbiota composition in broiler chickens infected with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 1862–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Peng, A.; Yu, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, H. L-arginine protects ovine intestinal epithelial cells from lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis through alleviating oxidative stress. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 67, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierse, R.M.; Oerlemans, R.; Reddem, E.R.; Gawriljuk, V.O.; Alhayek, A.; Baitinger, D.; Jakobi, H.; Laber, B.; Lange, G.; Hirsch, A.K. First crystal structures of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXPS) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis indicate a distinct mechanism of intermediate stabilization. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, S.C.; Kuo, K.L.; Wu, C.C.; Tarng, D.C. Indoxyl sulfate: A novel cardiovascular risk factor in chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran-Pinedo, A.E.; Solbiati, J.; Frias-Lopez, J. The effect of the stress hormone cortisol on the metatranscriptome of the oral microbiome. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2018, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).