Abstract

Aging is associated with alterations in gut microbiota, yet the combined effects of geography and diet remain underexplored in elderly populations. This study investigated the gut microbiota of 227 healthy Vietnamese individuals aged ≥60 years, stratified by select urban and rural residence in both Hanoi and Thanh Hoa provinces, and across three age groups (60–69, 70–79, ≥80 years). Dietary patterns were collected and recorded for each participant. 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed significant differences in microbial diversity and composition associated with geographical location (urban, rural) and age. Urban participants in Hanoi exhibited higher richness and greater abundance of health-associated genera, including Bifidobacterium, Fusicatenibacter, and Blautia, likely reflecting more diverse plant-based diets. In contrast, rural participants in Thanh Hoa showed enrichment of beneficial butyrate-producing genera such as Fusicatenibacter, Roseburia, Lachnospira and Blautia, possibly linked to traditional diets rich in freshwater fish and fermented foods. Participants aged 70–79 years displayed reduced microbial richness compared to other age groups. Age-related reductions in Roseburia, Veillonella, and Prevotella were also observed. These findings highlight how geography, diet, and aging shape the gut microbiota and may guide microbiota-targeted dietary strategies to promote healthy aging.

Keywords:

gut microbiota; aging; diet; alpha diversity; beta diversity; 16S rRNA sequencing; healthy aging 1. Introduction

The human gut microbiome is a diverse and dynamic ecosystem consisting of trillions of microbial cells, primarily bacteria, that reside predominantly in the colon [1,2,3,4]. This complex community plays a vital role in regulating digestion, metabolism, immune function, and host defense [5,6]. Disruptions to this ecosystem—referred to as dysbiosis—have been implicated in a variety of conditions, including inflammatory, metabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases [7,8,9,10,11].

Multiple host and environmental factors influence gut microbial composition such as age, diet, medications (especially antibiotics), physical activity, socioeconomic factors, immune status and overall well-being [7,12,13,14,15]. Among these determinants, diet is consistently identified as one of the strongest modifiable drivers of gut microbiome composition [16], while medications such as antibiotics [17] and proton-pump inhibitors [18] can exert dominant short-term effects. Long-term geographic and lifestyle exposures also shape population-level microbial profiles, particularly in older adults [19]. These variables have complex, interrelated effects on microbiota structure and function. Notably, aging is often accompanied by a reduction in microbial diversity and the depletion of beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium, alongside an increase in opportunistic taxa, including Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Enterobacteriaceae [20]. These shifts may contribute to immunosenescence, frailty, chronic low-grade inflammation (“inflammaging”), and increased disease susceptibility [21,22,23,24]. However, some older individuals maintain microbiota profiles resembling those of younger adults, suggesting that diet and lifestyle may mitigate age-related microbial decline [25,26]. Recent evidence also shows that therapeutic interventions, such as direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), can reshape gut microbiota composition and diversity, reinforcing that environmental and lifestyle modifications, including diet, can modulate microbial recovery [27].

Centenarians are increasingly studied as models of healthy aging, having avoided many age-associated diseases [24,28,29]. Their gut microbiota often features beneficial taxa, particularly anti-inflammatory and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) producers, that support gut barrier integrity, immune balance, and systemic metabolic health [30,31]. However, not all elderly populations exhibit the same microbial features, and variation may reflect broader cultural, dietary, and environmental exposures.

Although interest in aging and the microbiome is growing, data from Southeast Asia remain limited. Vietnam is particularly suited for microbiome-longevity research due to its high life expectancy, pronounced urban–rural divide and enduring traditional dietary patterns. Vietnamese centenarians typically consume rice-based, plant-forward diets, moderate amounts of animal protein, and fermented foods rich in natural probiotics [32,33,34]. These diets, along with physically active rural lifestyles, create unique environmental exposures that likely shape the aging gut microbiome [35]. Importantly, Vietnamese dietary habits differ substantially from other Asian cohorts, particularly in the types of herbs, vegetables, seafood, and region-specific fermented foods consumed [36]. Furthermore, Vietnam is undergoing one of the fastest nutrition and lifestyle transitions in Southeast Asia, creating a sharper contrast between traditional rural diets and increasingly processed urban dietary patterns compared with neighboring countries [37,38]. While it is difficult to control for all potential confounders in population-based studies, our study focuses on three interlinked determinants—age, diet, and urban–rural residence—within a relatively healthy elderly Vietnamese population. This approach allows for targeted exploration of microbial shifts in a culturally distinct and underrepresented setting.

Urbanization has emerged as a critical factor influencing microbiota composition. Urban lifestyles are often associated with processed foods, reduced fiber intake, higher antibiotic exposure, and more sedentary behavior, while rural populations tend to maintain traditional dietary patterns and active routines [39,40,41]. Thus, cross-sectional comparisons between rural and urban elderly can reveal how lifestyle and environment intersect with microbial aging trajectories [42,43,44].

Despite advances in sequencing technologies and growing interest in aging microbiome, its characterization remains challenging due to inter-individual variability and confounding factors such as medications, comorbidities, genetics, physical activity, environment and diet [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. Moreover, reliance on Western cohorts limits the generalizability of findings to other regions. Observed differences in the microbiota among centenarians in Japan, Italy, and China suggest that cultural and dietary contexts play a critical role in shaping longevity-associated microbial signatures [30,54,55]. These insights may guide microbiome-targeted strategies, as recent evidence supports therapeutic modulation of gut microbiota to promote homeostasis in age-related conditions [56].

We hypothesized that elderly individuals living in rural Vietnamese settings, due to greater adherence to traditional diets and more natural environmental exposure, would exhibit higher microbial diversity and a greater abundance of health-associated taxa, including beneficial SCFA-producing genera [57], compared to their urban counterparts. However, the impact of rapid urbanization, dietary transitions, and evolving healthcare access may be reshaping these expected patterns.

This study aims to characterize the gut microbiome composition of healthy elderly Vietnamese individuals by comparing cohorts from urban and rural areas in two provinces (Hanoi and Thanh Hoa), and to investigate microbial differences associated with age and diet. Using 16S Ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene sequencing, we assess microbial diversity, community structure, and differential abundance to explore how dietary habits and demographic factors influence the microbiota of aging adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

This cross-sectional study was conducted across two provinces in Vietnam—Hanoi and Thanh Hoa, each comprising both urban and rural settings. A total of 227 self-reported healthy elderly participants aged 60 years or older were recruited through local community centers from four distinct cohorts: urban Hanoi (Thanh Xuan District, n = 47), rural Hanoi (Me Linh District, n = 69), urban Thanh Hoa (Dong Huong Ward, n = 56), and rural Thanh Hoa (Hoang Dai Ward, n = 55). Participants were stratified into three age groups: 60–69 years (n = 118), 70–79 years (n = 68), and ≥80 years (n = 41). In terms of gender distribution, 65 participants were male and 162 were female (Table 1). Inclusion criteria required participants to have regular bowel movements, no antibiotic use within four weeks prior to sample collection, and no use of medications that may affect gut microbiota, including antidiabetic drugs and proton pump inhibitors. Individuals with gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., chronic colitis, diarrhea, or constipation) or chronic diseases were excluded. Informed consent was obtained, and participants completed questionnaires detailing demographic information, diet (as described in Table 2 and Table 3) and general health. Stool samples were self-collected using sterile containers and stored on ice and transport to laboratory for processing. All samples were collected during the summer (June–August) to minimize seasonal variation in diet and microbiota composition. The study aimed to investigate differences in gut microbiota composition based on geographic location (urban vs. rural) and age group (60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years) among healthy elderly individuals. The study was approved by the Institute of Genome Research Institutional Review Board for Biomedical Research, and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Ethics approval number: 05-2-23/NCHG-HDDD).

Table 1.

Distribution of study participants (n = 227) by age group and gender across urban and rural areas in Hanoi and Thanh Hoa.

2.2. Survey of Food Intake of Participants

To gain insights into the dietary habits of study participants, a structured food frequency questionnaire was administered to each individual at the time of sample collection. The survey form was designed to capture the habitual intake of key food groups, including vegetables, fruits, meats, fish, and fried or fast foods.

Participants were asked how frequently they consumed each food category, with options ranging from “three times or more per day” to “rarely.”. Special attention was paid to the frequency of fast-food consumption (e.g., pizza, fried chicken, French fries), which was categorized as: more than three times per week, two to three times per week, one time per week, two to three times per month, once per month, or rarely.

This dietary data was used to contextualize microbial differences between participants and contributed to the analysis of diet-associated microbial signatures across different age groups and geographic locations.

2.3. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Amplification

Stool DNA was extracted using a validated protocol combining mechanical (bead beating), enzymatic (lysozyme, lysostaphin, mutanolysin), and chemical lysis with 4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 10% N-lauryl sarcosine, and 100 mg/mL polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP). DNA was precipitated with ethanol, treated with RNase A, and purified via sodium acetate. Reagents included EDTA, NaCl, sodium phosphate buffer, SDS, isopropanol, and ethanol, as described in previous work [58]. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

The bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified targeting the V3–V4 region using dual-index primers—pro341F (5′-CCTACGGGNBGCASCAG-3′) and pro805R (5′-GACTACNVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′), which incorporated index sequences, heterogeneity spacers, and Illumina adapter linkers (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) [59].

PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 µL using Q5 High-Fidelity 2× Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), 250 nM of each primer, and 1 µL of template DNA. Amplification was carried out on an Eppendorf Mastercycler Pro (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 1 min; 35 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 49 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s; followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Following amplification, PCR products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the presence and size of the expected amplicon bands prior to sequencing. Negative controls (nuclease-free water) were included and showed no amplification.

2.4. Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

Amplicon sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiSeq platform with 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads. Raw sequences were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.39 to remove low-quality reads and adapters [59]. Denoising, Quality filtering, chimera removal and feature inference were conducted using the Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 (DADA2) pipeline within Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME2) v2020.6 [60,61], producing high-resolution ASVs. Taxonomic classification was assigned using the SILVA rRNA Database (v138) [62].

2.5. Statistical and Diversity Analyses

Microbial community profiling and statistical analyses were performed using MicrobiomeAnalyst (https://www.microbiomeanalyst.ca/MicrobiomeAnalyst/home.xhtml, accessed on 2 December 2025) [60]. Alpha diversity (Chao1, Shannon) was calculated from rarefied ASV tables. Non-parametric tests were applied: Mann–Whitney for two-group and Kruskal–Wallis for multi-group comparisons, with post hoc pairwise testing and FDR correction (Benjamini–Hochberg). Beta diversity was assessed using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, visualized by PCoA, and tested with PERMANOVA. Differentially abundant taxa across groups were identified using LEfSe and single factor implemented in the MicrobiomeAnalyst software with FDR-adjusted p-values and an LDA score threshold of ±2.0. Prior to differential abundance testing, relative abundance values were log-transformed using base-10 logarithm (log10), following MicrobiomeAnalyst’s default settings.

To standardize abundance values prior to differential abundance analysis and visualization, MicrobiomeAnalyst applies total-sum scaling (TSS), converting counts to relative abundances and multiplying by the platform’s default scaling factor. These TSS-scaled abundances were subsequently log10(x + 1)-transformed following MicrobiomeAnalyst’s default settings. All reported p-values are FDR-corrected.

3. Results

3.1. Gut Microbiome Profiling: Sequencing Depth and Data Quality

Following quality control, a total of 2,178,830 high-quality paired-end reads were obtained, with an average of 9598 reads per sample. To reduce noise and minimize the influence of sequencing artifacts, the Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) table was filtered to exclude features present in only a single sample and those with a total abundance of less than 100 reads. The number of features that remained after the data filtering step is 5163 for further investigation. The raw sequence data generated in this study was submitted to the NCBI SRA database and are publicly available under accession number PRJNA1331965.

3.2. Diet Diversity and Regional Eating Patterns Among Elderly Vietnamese

Dietary data revealed notable regional and lifestyle-related differences. In Hanoi, vegetable intake was more frequent among urban participants, with 40.4% and 57.4% consuming vegetables three and twice daily, respectively, and none reporting rare consumption. In contrast, vegetable intake was lower in rural Hanoi, with only 18% consuming 3 times per day, 42.0% consuming twice daily, and 14.5% reporting rare intake. Similarly, fruit intake was more frequent in urban Hanoi (44.7% twice daily) compared to 27.5% in rural Hanoi, and rare consumption was much higher in rural Hanoi (30.4%) compared to urban areas (4.3%). Meat consumption patterns were broadly similar across groups, although rare intake was more common among rural participants (17.4%) than in urban participants (6.4%). Daily fish intake was more prevalent in urban Hanoi (42.6% vs. 17.4%, 2 twice daily), whereas more rural participants reported rarely consuming fish (42.0% vs. 6.4%). Fried food consumption showed little difference between the groups, with daily intake reported by 31.9% of urban and 27.5% of rural participants, and rare intake by 57.4% and 60.9%, respectively. Interestingly, fast food consumption showed the opposite trend—rare intake was more frequent in urban Hanoi (78.7%) compared to rural Hanoi (33.3%), and a greater proportion in rural Hanoi reported consumption ≥ 3 times/week (8.7% vs. 4.3%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency (%) of vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, and fried food and fast food consumption among elderly participants in urban and rural Hanoi.

Table 2.

Frequency (%) of vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, and fried food and fast food consumption among elderly participants in urban and rural Hanoi.

| Food Group | Frequency | Urban Hanoi (%) | Rural Hanoi (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | ≥3/day | 40.4 | 18.8 |

| 2/day | 57.4 | 42.0 | |

| 1/day | 2.1 | 24.6 | |

| Rarely | 0.0 | 14.5 | |

| Fruits | ≥3/day | 27.7 | 11.6 |

| 2/day | 44.7 | 27.5 | |

| 1/day | 23.4 | 30.4 | |

| Rarely | 4.3 | 30.4 | |

| Meat | ≥3/day | 10.6 | 13.0 |

| 2/day | 51.1 | 43.5 | |

| 1/day | 31.9 | 26.1 | |

| Rarely | 6.4 | 17.4 | |

| Fish | ≥3/day | 4.3 | 7.2 |

| 2/day | 46.8 | 17.4 | |

| 1/day | 42.6 | 33.3 | |

| Rarely | 6.4 | 42.0 | |

| Fried foods | ≥3/day | 2.1 | 4.3 |

| 2/day | 8.5 | 7.2 | |

| 1/day | 31.9 | 27.5 | |

| Rarely | 57.4 | 60.9 | |

| Fast food | ≥3 times/week | 4.3 | 8.7 |

| 2–3 times/week | 2.1 | 8.7 | |

| 1 time/week | 6.4 | 17.4 | |

| 2–3 times/month | 6.4 | 17.4 | |

| 1 time/month | 2.1 | 14.5 | |

| Rarely | 78.7 | 33.3 |

In Thanh Hoa province, dietary habits were more consistent between urban and rural groups. Nearly all participants consumed vegetables at least twice daily (89.3% urban vs. 96.4% rural), and none reported rare intake. Rare fruit consumption was notably higher in rural Thanh Hoa (30.9%) compared to none in urban areas. Daily fruit intake was also higher among urban participants (92.9%) than rural participants (69.1%). A quarter of rural Thanh Hoa participants rarely consume meat, compared with only 7.1% of urban Thanh Hoa participants. However, rural participants consume fish more frequently than the urban group, with 60.0% eating fish twice daily, compared to just 19.6% of urban participants. Both groups reported infrequent consumption of fried and fast food, with over 90% in each group indicating rare intake. No participants in either urban or rural Thanh Hoa reported fast food consumption two or more times per week (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency (%) of vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, fried food and fast food consumption among elderly participants in urban and rural Thanh Hoa.

Table 3.

Frequency (%) of vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, fried food and fast food consumption among elderly participants in urban and rural Thanh Hoa.

| Food Group | Frequency | Urban Thanh Hoa (%) | Rural Thanh Hoa (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | ≥3/day | 5.4 | 1.8 |

| 2/day | 89.3 | 96.4 | |

| 1/day | 5.4 | 1.8 | |

| Rarely | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Fruits | ≥3/day | 7.1 | 0.0 |

| 2/day | 37.5 | 30.9 | |

| 1/day | 55.4 | 38.2 | |

| Rarely | 0.0 | 30.9 | |

| Meat | ≥3/day | 5.4 | 0.0 |

| 2/day | 33.9 | 45.5 | |

| 1/day | 53.6 | 29.1 | |

| Rarely | 7.1 | 25.5 | |

| Fish | ≥3/day | 0.0 | 1.8 |

| 2/day | 19.6 | 60.0 | |

| 1/day | 48.2 | 18.2 | |

| Rarely | 32.1 | 20.0 | |

| Fried foods | ≥3/day | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| 2/day | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 1/day | 5.4 | 9.1 | |

| Rarely | 92.9 | 90.1 | |

| Fast food | ≥3 times/week | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2–3 times/week | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 1 time/week | 3.6 | 0.0 | |

| 2–3 times/month | 1.8 | 3.6 | |

| 1 time/month | 10.7 | 1.8 | |

| Rarely | 83.9 | 94.5 |

3.3. Alpha Diversity Patterns Differ by Region and Age in Vietnamese Elderly

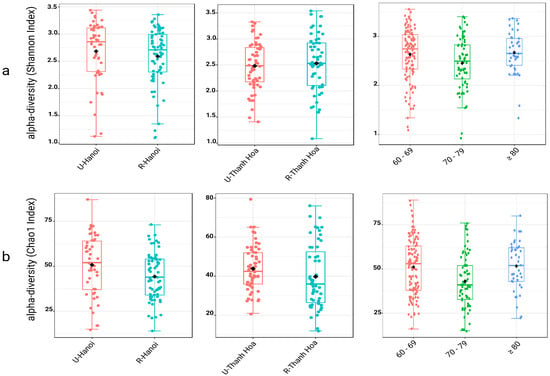

Alpha diversity was assessed using the Chao1 and Shannon indices at the genus level to compare microbial richness and diversity across urban and rural populations in both Hanoi and Thanh Hoa, as well as among different elderly age groups. In Hanoi, microbial richness (Chao1) was significantly higher in urban participants compared to rural counterparts (p = 0.019), while no significant difference was detected in diversity (Shannon index; p = 0.201). In Thanh Hoa, no significant differences were observed between urban and rural groups for either richness (Chao1; p = 0.052) or diversity (Shannon; p = 0.054).

When analyzed by age, a non-linear pattern emerged. Participants aged 70–79 exhibited significantly lower richness and diversity than both younger (60–69) and older (≥80) groups. The Chao1 index showed significantly reduced richness in the 70–79 group compared to 60–69 (p = 0.003) and ≥80 (p = 0.003), with no significant difference between the 60–69 and ≥80 groups (p = 0.670). Similarly, the Shannon index revealed significantly lower diversity in the 70–79 group relative to the 60–69 (p = 0.04) and ≥80 groups (p = 0.04), while the latter two did not differ significantly (p = 0.98). These results highlight a dip in gut microbial richness and diversity specifically in the 70–79 age cohort, indicating a transient reduction in microbiome complexity with advancing age (Figure 1, Table S1).

Figure 1.

Alpha diversity of gut microbiota across location and age groups, assessed using two indices. Alpha diversity was evaluated using the Shannon index (a) to represent microbial diversity and the Chao1 index (b) to reflect microbial richness, both at the genus level. Each set of boxplots compares diversity between urban (U) and rural (R) populations in Hanoi (U-Hanoi vs. R-Hanoi), Thanh Hoa (U-Thanh Hoa vs. R-Thanh Hoa), and among different age groups (60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years). Boxplots display the median, interquartile range, individual sample values. The black rhombuses represent the group means.

3.4. Beta Diversity Across Regions and Age Groups

Beta diversity was assessed using Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity to evaluate and visualize similarities/dissimilarities in the overall microbial community composition between urban and rural participants within each location and across age groups. In Hanoi, the PCoA plot demonstrated substantial overlap between U-Hanoi and R-Hanoi groups, and Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) analysis confirmed no statistically significant differences (R2 = 0.01, p = 0.197), indicating similar overall microbial structures. In contrast, microbial community composition in Thanh Hoa showed clearer separation between U-Thanh Hoa and R-Thanh Hoa participants. PERMANOVA analysis supported these observations, revealing significant differences in beta diversity (R2 = 0.0545, p = 0.001).

When analyzed by age, PCoA revealed partial separation among the three age groups (60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years). PERMANOVA analysis confirmed that overall community composition differed significantly across age groups (R2 = 0.0219, p = 0.003). Pairwise comparisons indicated significant differences between the 70–79 and ≥80 groups (R2 = 0.022, p = 0.01), between the ≥80 and 60–69 groups (R2 = 0.022, p = 0.003) and between the 70–79 and 60–69 groups (R2 = 0.008, p = 0.082) (Figure S1, Table S2).

3.5. Location- and Age-Associated Shifts in the Relative Abundance of Dominant Gut Microbial Genera

The relative abundance of the top 20 gut microbial genera revealed distinct patterns across location and age groups among elderly participants. In Hanoi, Bacteroides was the dominant genus in both urban (16%) and rural (17%) groups. Akkermansia was more abundant in urban participants (1.9%) compared to rural (0.8%), and Bifidobacterium also showed higher levels in the urban group (3.3%) than in the rural group (0.7%), highlighting location-related microbial variation. In Thanh Hoa, Bacteroides, Fusicatenibacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in rural participants (14.3%, 3.19%, and 1.9%, respectively) than in urban participants (5.5%, 0.5%, and 0.2%, respectively), while Collinsella showed higher levels in the urban group (6.1%) compared to the rural group (1.0%). No notable differences in Bifidobacterium were observed between groups (Supplementary Figure S2).

Age-associated trends were also evident, with Bacteroides increasing progressively with age, reaching the highest relative abundance in the ≥80 group (20.1%), while Prevotella declined from 12.8% in the 60–69 group to 8.9% in the ≥80 group. Collinsella exhibited a marked increase in the oldest group (4.1%). Agathobacter was more abundant in the 70–79 group. No notable differences in Bifidobacterium were observed across age groups (Figure S3, Tables S3–S5).

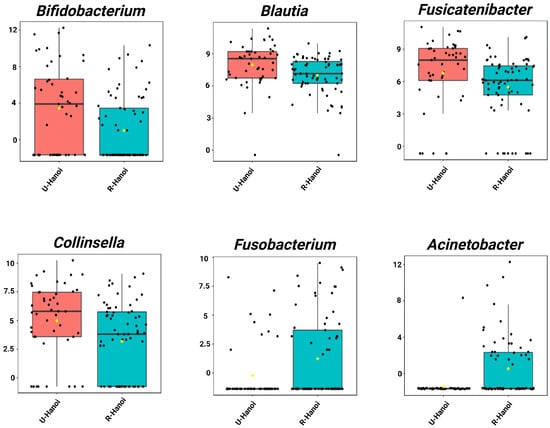

3.6. Univariate Analysis of Differentially Abundant Genera Between Urban and Rural Groups

Single-factor analysis revealed distinct genera with significantly different relative abundances between urban and rural elderly participants in both Hanoi and Thanh Hoa (LDA score > 2.0, p < 0.05). In Hanoi, eight genera were identified as significantly different. The urban group (U-Hanoi) showed higher abundances of Bifidobacterium, Fusicatenibacter, Collinsella, and Blautia. In contrast, the rural group (R-Hanoi) was enriched with Fusobacterium and Acinetobacter (Figure 2, Table S7).

Figure 2.

Single-factor analysis of differentially abundant genera between urban (U-Hanoi, red) and rural (R-Hanoi, blue) participants in Hanoi. Genera with LDA scores ± 2.0 and p < 0.05 are shown. Values represent TSS-scaled relative abundances log10(x + 1)-transformed. The yellow rhombuses represent the group means.

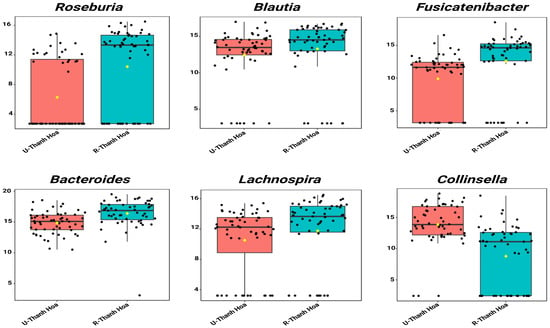

In Thanh Hoa, single-factor analysis identified 6 genera that differed significantly between urban (U-Thanh Hoa) and rural (R-Thanh Hoa) participants. Urban individuals had an increased abundance of Collinsella. Conversely, the rural group showed enrichment in Fusicatenibacte, Bacteroides, Lachnospira, Roseburia and Blautia (Figure 3, Table S8).

Figure 3.

Single-factor analysis of differentially abundant genera between urban (U-Thanh Hoa, red) and rural (R-Thanh Hoa, blue) participants in Thanh Hoa. Genera with LDA scores ± 2.0 and p < 0.05 are shown. Values represent TSS-scaled relative abundances log10(x + 1)-transformed. The yellow rhombuses represent the group means.

3.7. Univariate Analysis of Age-Associated Differences in Gut Microbial Genera

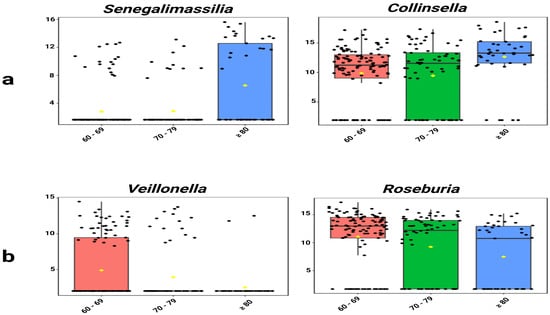

LEfSe analysis identified the top 15 genera with significantly different relative abundances across the three elderly age groups (60–69, 70–79, and ≥80 years). The ≥80 age group was characterized by a higher abundance of Collinsella, Butyrivibrio, Senegalimassilia, Bacteroides_pectinophilus_group, UCG_005, lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Bacillus and Cerasibacillus. In the 70–79 age group, Ruminococcus_gnavus_group was enriched. Meanwhile, the 60–69 group exhibited increased levels of Eubacterium eligens group, Roseburia, Butyricicoccus and Veillonella (Figure S4, Table S6).

Single-factor analysis revealed distinct age-specific enrichment patterns. Senegalimassilia (p = 0.001) and Collinsella (p = 0.014) showed significantly increasing abundance with age (Figure 4a). Conversely, Veillonella (p = 0.036) and Roseburia (p = 0.016) exhibited significantly decreasing trends (Figure 4b, Table S9).

Figure 4.

Age-associated trends in selected genera. (a) Senegalimassilia and Collinsella showed significantly increasing abundance with age. (b) Veillonella and Roseburia showed significantly decreasing abundance. Values represent TSS-scaled relative abundances log10(x + 1)-transformed. The yellow rhombuses represent the group means.

4. Discussion

We initially hypothesized that rural participants would exhibit higher gut microbial diversity due to greater environmental exposure and diets richer in fiber and fermented foods [63,64,65,66], factors previously linked to better physical capacity and lower biological age [67,68]. Contrary to this expectation, urban Hanoi participants displayed significantly greater microbial richness than their rural counterparts. This aligns with recent evidence showing no consistent association between diversity and chronological or biological age, nor with physical function [69].

In this study, urban Hanoi participants reported higher daily intake of vegetables (≥2/day: 97.8% vs. 60.8%) and fruits (≥2/day: 72.4% vs. 39.1%) than their rural counterparts, which is contrary to our initial assumption and may explain their greater microbial richness. These dietary patterns corresponded with a higher abundance of health-associated genera such as Bifidobacterium, Fusicatenibacter, and Blautia, which are known for their immunomodulatory effects, SCFA production and maintenance of gut barrier integrity [70,71,72,73,74,75,76]. Similar enrichment of Bacteroides and Blautia has also been observed in Japanese and Korean elderly cohorts residing in highly urbanized areas like Kyoto and Seoul [77,78,79]. In contrast, rural participants had lower intake of plant-based foods—evidenced by higher rates of rare vegetable (14.5% vs. 0%) and fruit intake (30.4% vs. 4.3%)— alongside reduced fish consumption (rarely: 42.0% vs. 6.4%) and greater fast-food intake (66.7% consuming fast food ≥ 1 time/month vs. 21.3% in urban Hanoi) (Table 2). These patterns corresponded with the enrichment of potentially pro-inflammatory and opportunistic pathogens like Fusobacterium and Acinetobacter [80,81,82,83,84]. This suggests that plant-based dietary diversity and fish intake support healthier gut microbiota, while low-fiber, processed-food-rich diets may promote harmful bacteria [85,86,87,88]. Despite our hypothesis anticipating the opposite, urban dwellers may benefit from increased exposure to health education, preventative care, and access to nutritional guidance, which could lead to dietary habits and lifestyles more conducive to maintaining microbial diversity and resilience.

In contrast, rural participants in Thanh Hoa exhibited a higher relative abundance of beneficial genera, including Fusicatenibacter, Lachnospira, Roseburia, and Blautia [74,75,89]. This profile may be partially attributed to the significantly greater consumption of fish in the rural cohort (≥2/day: 61.8% vs. 19.6%), which provides omega-3 fatty acids known to promote anti-inflammatory and butyrate-producing bacteria [88]. Additionally, rural participants reported lower fast-food intake (rarely: 94.5% vs. 83.9%), potentially limiting dietary sources of dysbiosis-associated taxa. Although a higher proportion of rural participants reported rare fruit consumption (30.9% vs. 0% in urban), this may reflect seasonal availability in rural areas rather than an absence of plant-based diversity. Traditional dietary practices likely persist in these communities, with a strong reliance on home-prepared meals based on rice, vegetables, freshwater fish, and fermented products such as soybean sauce paste (Tuong), shrimp paste (Tom chua), fermented rice (Com me) and fish-based condiments such as fermented fish paste (Mam chua) and sauce (Nuoc mam) [34]. These fermented foods are rich in lactic acid bacteria and microbial metabolites that may further support the growth of saccharolytic and butyrate-producing taxa such as Roseburia [90]. Notably, Roseburia and Lachnospira were also enriched in rural Japanese and Korean elderly populations from longevity villages [77,79], where fermentation-based diets are prevalent [91,92]. Collectively, these findings highlight how local dietary patterns and cultural traditions in rural Thanh Hoa can shape the gut microbiota in beneficial ways, underscoring the region-specific impact of urbanization on microbial ecology.

Collinsella showed consistent enrichment in urban populations of both provinces, echoing findings from urban Makassar, Indonesia [93], but contrasting with its rural dominance in China [94], suggesting a context-dependent distribution. Its abundance has been associated with low fiber intake [95,96], omnivorous diets [97], and ghee consumption [98], while decreasing under low-carbohydrate diets [48]. Although reduced in IBD [94], Collinsella has also been implicated in rheumatoid arthritis, hypercholesterolemia [98], symptomatic atherosclerosis [50], and certain cancers [99], indicating potential pathogenic roles in some contexts. The elevated levels of Collinsella observed among urban participants may be partially attributable to dietary patterns [95,100], particularly higher meat consumption, which was notably more frequent in urban cohorts across both Hanoi and Thanh Hoa (≥2/day) (Table 2 and Table 3). This suggests that urban dietary habits may contribute to the enrichment of Collinsella.

The long-standing view that gut microbial diversity declines progressively with age [101,102] has been increasingly contested. In our study, although alpha diversity—measured by Chao1 and Shannon indices—was reduced in individuals aged 70–79, it was notably higher in the oldest group (≥80 years). Similar trends have been reported in nonagenarians and centenarians, who often display greater microbial richness than younger elderly cohorts [103]. Kong et al. (2019) similarly observed elevated diversity in long-lived individuals from Jiangsu and Sichuan provinces in China [43]. Furthermore, no significant difference was found between the youngest elderly group (60–69 years) and the ≥80 cohort, aligning with a large Chinese population-based study showing that elderly microbiota profiles often resemble those of younger adults [26]. These findings suggest that gut microbial diversity does not decline in a linear trajectory with age; rather, a stabilization or even recovery of diversity may occur in longevity-associated populations. However, our data cannot conclusively rule on age-related decline, given the restricted age range studied (aged ≥60 years).

Roseburia and Veillonella were among the most frequently reported genera associated with age-related microbial changes. In our study, both genera declined significantly with increasing age. The reduction in Roseburia aligns with findings from Italian, Irish, and Thai cohorts [25,54,104,105], though opposite trends have been observed in Russian, Chinese, and Korean populations [106,107,108,109]. As a key butyrate producer, Roseburia supports gut homeostasis by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-8 (IL-8), upregulating anti-inflammatory mediators Interleukin-10 (IL-10) and Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β), and strengthening barrier integrity through mucin 2 and tight junction proteins [110]. Notably, both Roseburia and Prevotella are reduced in frail older adults, suggesting a link between their depletion and aging-related frailty [110,111,112,113]. Similarly, Veillonella abundance declined with age, consistent with findings in adults ≥ 75 years [114], though not replicated in all cohorts [108,115,116]. Veillonella metabolizes exercise-derived lactate into propionate and is enriched in physically active individuals, including marathon runners [117]. Its decline may therefore reflect reduced physical activity and lactate availability in older adults, supporting its potential as a biomarker of physical decline [114].

In this study, the genus Senegalimassilia exhibited a significant increase across age cohorts. This pattern may be partially influenced by gender distribution (Table 1). A previous study reported slightly higher Senegalimassilia abundance in females and also suggested a potential link with body weight [118]. Thus, the age-related increase observed in our cohorts may reflect, at least in part, the higher proportion of females in our cohorts. Future studies should adjust for sex and body mass index when examining microbial trends across aging populations to better disentangle age-specific effects from potential confounders.

This study offers new insights into the gut microbiota of elderly populations in Vietnam, demonstrating that both geographical location and age significantly influence microbial diversity and composition. Urban residents, particularly those in Hanoi, exhibited greater microbial richness and higher abundance of health-associated genera, likely shaped by diverse plant-based diets and better access to healthcare and nutritional education. In contrast, the opposite trend was observed in rural Thanh Hoa, were enriched in butyrate-producing genera such as Fusicatenibacter, Roseburia, and Blautia, reflecting traditional dietary patterns rich in freshwater fish and fermented foods. Age-stratified analysis revealed that microbial diversity does not decline uniformly with age; notably, individuals aged ≥80 years exhibited signs of diversity stabilization or recovery, accompanied by compositional shifts in key taxa including Roseburia and Veillonella.

Importantly, these findings also suggest translational potential, as microbiome-informed dietary strategies, such as increasing the intake of fiber-rich and fermented foods, could support gut health and improve aging outcomes among the Vietnamese elderly. Although some dietary differences were observed, overall dietary patterns aligned closely with regional residence, and the single-season sampling limited our ability to analyze diet as an independent factor. This study is also constrained by the absence of metabolomic data and longitudinal follow-up, which restricts functional interpretation. Future studies incorporating multi-season sampling, diverse dietary profiles, and long-term metagenomics are needed to clarify mechanisms and identify microbial markers that support healthy aging.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microorganisms13122803/s1. Figure S1: Beta diversity of gut microbiota across location and age groups, visualized using PCoA; Figure S2: Relative abundance of the top 20 bacterial genera in urban and rural elderly populations from two Vietnamese provinces; Figure S3: Genus-level composition of gut microbiota across different elderly age groups in both provinces; Figure S4: LEfSe analysis of differentially abundant genera across age groups (60–69 years, 70–79 years, and ≥80 years). Table S1: Statistical results for alpha diversity (Chao1 and Shannon indices) across regions and age groups. Table S2: Statistical results for beta diversity (Bray–Curtis distances and PERMANOVA) across regions and age groups. Table S3: Genus-level relative abundance (%) of dominant taxa in urban and rural Hanoi. Table S4: Genus-level relative abundance (%) of dominant taxa in urban and rural Thanh Hoa. Table S5: Genus-level relative abundance (%) of dominant taxa across age groups (60–69, 70–79, and ≥79 years). Table S6: LEfSe-identified discriminative genera across age groups with corresponding LDA scores and relative abundance values. Table S7: Significant genus-level features from single-factor analysis comparing urban and rural Hanoi. Table S8: Significant genus-level features from single-factor analysis comparing urban and rural Thanh Hoa. Table S9: Significant genus-level trends from single-factor analysis across age groups (60–69, 70–79, and ≥79 years).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T.H.V., A.H., L.V.T. and D.V.Q.; methodology, A.H., T.T.H.V., D.S., L.V.T., D.V.Q., V.T.H., P.A.N., T.B.D.H., R.E. and C.L.; software, D.S. and T.T.H.V.; validation, T.T.H.V., A.H., L.V.T. and D.V.Q.; formal analysis, A.H. and T.T.H.V.; investigation, A.H., T.T.H.V., L.V.T. and D.V.Q.; resources, T.T.H.V., L.V.T. and D.V.Q.; data curation, T.T.H.V. and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.; writing—review and editing, T.T.H.V., D.S., R.E., C.L., L.V.T., D.V.Q., V.T.H., P.A.N. and T.B.D.H.; visualization, A.H.; supervision, T.T.H.V., L.V.T., D.V.Q., R.E., C.L. and D.S.; project administration, T.T.H.V.; funding acquisition, T.T.H.V., L.V.T. and D.V.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the RMIT Vice Chancellor Senior Research Fellow (2022 round) and the Institute of Biology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (grant number CSCL08.01/24-25).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institute of Genome Research Institutional Review Board for Biomedical Research on 20 September 2023 (approval number 05-2-23/NCHG-HDDD).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in NCBI SRA database at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=PRJNA1331965 with accession number PRJNA1331965.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Thi Bach Duong Hoang is employed by New Horizon Palliative Care Company Limited, Hanoi, Vietnam. The company was not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCFA | Short-Chain Fatty acid |

| 16S rRNA ASV | 16S Ribosomal RNA Amplicon Sequence Variant |

| OTUs | Operational Taxonomic Units |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| LEfSe | Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| V3–V4 | Variable Regions 3 and 4 of the 16S rRNA Gene |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| MiSeq | Illumina MiSeq Sequencing Platform |

| DADA2 | Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 |

| QIIME2 | Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 |

| SILVA | SILVA rRNA Database |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| DAAs | Direct-acting antivirals |

| PVPP | polyvinylpolypyrrolidone |

References

- Ley, R.E.; Lozupone, C.A.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. Worlds within Worlds: Evolution of the Vertebrate Gut Microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A Human Gut Microbial Gene Catalogue Established by Metagenomic Sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, R.W.; Arhire, L.; Covasa, M. Gut Microbiota: From Microorganisms to Metabolic Organ Influencing Obesity. Obesity 2018, 26, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekirov, I.; Russell, S.L.; Antunes, L.C.; Finlay, B.B. Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 859–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Holmes, E.; Kinross, J.; Burcelin, R.; Gibson, G.; Jia, W.; Pettersson, S. Host-Gut Microbiota Metabolic Interactions. Science 2012, 336, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Nair, G.B. Homeostasis and Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease. J. Biosci. 2019, 44, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, M.; Biagi, E.; Turroni, S.; Maccaferri, S.; Figini, P.; Brigidi, P. Dynamic Efficiency of the Human Intestinal Microbiota. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 41, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joossens, M.; Huys, G.; Cnockaert, M.; De Preter, V.; Verbeke, K.; Rutgeerts, P.; Vandamme, P.; Vermeire, S. Dysbiosis of the Faecal Microbiota in Patients with Crohn’s Disease and Their Unaffected Relatives. Gut 2011, 60, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, X.C.; Tickle, T.L.; Sokol, H.; Gevers, D.; Devaney, K.L.; Ward, D.V.; Reyes, J.A.; Shah, S.A.; LeLeiko, N.; Snapper, S.B.; et al. Dysfunction of the Intestinal Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Treatment. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kootte, R.S.; Levin, E.; Salojärvi, J.; Smits, L.P.; Hartstra, A.V.; Udayappan, S.D.; Hermes, G.; Bouter, K.E.; Koopen, A.M.; Holst, J.J.; et al. Improvement of Insulin Sensitivity after Lean Donor Feces in Metabolic Syndrome Is Driven by Baseline Intestinal Microbiota Composition. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 611–619.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Santisteban, M.M.; Rodriguez, V.; Li, E.; Ahmari, N.; Carvajal, J.M.; Zadeh, M.; Gong, M.; Qi, Y.; Zubcevic, J.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis Is Linked to Hypertension. Hypertension 2015, 65, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, M.; Biagi, E.; Maccaferri, S.; Turroni, S.; Brigidi, P. Intestinal Microbiota Is a Plastic Factor Responding to Environmental Changes. Trends Microbiol. 2012, 20, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, S.; Rao, S.; Khattak, A.; Zamir, F.; Chaari, A. Physical Exercise and the Gut Microbiome: A Bidirectional Relationship Influencing Health and Performance. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobre, J.G.; Alpuim Costa, D. Sociobiome: How Do Socioeconomic Factors Influence Gut Microbiota and Enhance Pathology Susceptibility?—A Mini-Review. Front. Gastroenterol. 2022, 1, 1020190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisinha, S. The Potential Impact of Gut Microbiota on Your Health: Current Status and Future Challenges. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 34, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeming, E.R.; Johnson, A.J.; Spector, T.D.; Le Roy, C.I. Effect of Diet on the Gut Microbiota: Rethinking Intervention Duration. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.; Guarner, F.; Bustos Fernandez, L.; Maruy, A.; Sdepanian, V.L.; Cohen, H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 572912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, L.; Chen, W.; Xue, Y.; Zhai, Q. Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors on the Human Gut Microbiota. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-H.; Sim, M.; Lee, J.-Y.; Shin, D.-M. Lifestyle and Geographic Insights into the Distinct Gut Microbiota in Elderly Women from Two Different Geographic Locations. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2016, 35, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Palva, A.M.; de Vos, W.M.; Satokari, R. Contribution of the Intestinal Microbiota to Human Health: From Birth to 100 Years of Age. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 358, 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Guigoz, Y.; Doré, J.; Schiffrin, E.J. The Inflammatory Status of Old Age Can Be Nurtured from the Intestinal Environment. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2008, 11, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwielehner, J.; Liszt, K.; Handschur, M.; Lassl, C.; Lapin, A.; Haslberger, A.G. Combined Pcr-Dgge Fingerprinting and Quantitative-Pcr Indicates Shifts in Fecal Population Sizes and Diversity of Bacteroides, Bifidobacteria and Clostridium Cluster IV in Institutionalized Elderly. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Thuret, S. Gut Microbiota: A Modulator of Brain Plasticity and Cognitive Function in Ageing. Healthcare 2015, 3, 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic Inflammation in Ageing, Cardiovascular Disease, And frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claesson, M.J.; Jeffery, I.B.; Conde, S.; Power, S.E.; O’Connor, E.M.; Cusack, S.; Harris, H.M.; Coakley, M.; Lakshminarayanan, B.; O’Sullivan, O.; et al. Gut Microbiota Composition Correlates with Diet and Health in the Elderly. Nature 2012, 488, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, G.; Gloor, G.B.; Gong, A.; Jia, C.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. The Gut Microbiota of Healthy Aged Chinese Is Similar to That of the Healthy Young. mSphere 2017, 2, e00327-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherbiny, N.M.; Kamal El-Din, O.M.; Hassan, E.A.; Hetta, H.F.; Alatawy, R.; Sayed Ali, M.A.; Alanazi, F.E.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.S.; Aljohani, H.M.; Badary, M.S.; et al. Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment Significantly Shaped the Gut Microbiota in Chronic Hepatitis C Patients: A Pilot Study. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1664447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberg, H.; Oksuzyan, A.; Jeune, B.; Vaupel, J.W.; Christensen, K. Centenarians—A Useful Model for Healthy Aging? A 29-Year Follow-up of Hospitalizations among 40,000 Danes Born in 1905. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, L.; Ostan, R.; Cevenini, E.; Pini, E.; Scurti, M.; Vitale, G.; Mari, D.; Caruso, C.; Sansoni, P.; Fanelli, F.; et al. Centenarians’ Offspring as a Model of Healthy Aging: A Reappraisal of the Data on Italian Subjects and a Comprehensive Overview. Aging 2016, 8, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odamaki, T.; Kato, K.; Sugahara, H.; Hashikura, N.; Takahashi, S.; Xiao, J.-Z.; Abe, F.; Osawa, R. Age-Related Changes in Gut Microbiota Composition from Newborn to Centenarian: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarino, L.; Granchi, D.; Ciapetti, G.; Cenni, E.; Ravaglia, G.; Forti, P.; Maioli, F.; Mattioli, R. Serum Concentrations of Zinc and Selenium in Elderly People: Results in Healthy Nonagenarians/Centenarians. Exp. Gerontol. 2001, 36, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quoc, L.P.T.; Ngoc, N.T.B. Comparison of the Vietnamese Diet with Diets from Other Countries for Sarcopenia. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 30, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thi, T.N.; Bui, N.-L.; Vu Thi, H.; Vu Ngoc, S.M.; Ngo, A.D.; Truong, T.N.; Nguyen, K.-H.; Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, N.M.; Trinh, K.; et al. Nutritional Status and Related Factors in Vietnamese Students in 2022. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci. 2024, 54, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Anh, N. Health-Promoting Microbes in Traditional Vietnamese Fermented Foods: A Review. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2015, 4, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.D.; Biesbroek, S.; Le, T.D.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Brouwer, I.D.; Talsma, E.F. Environmental Impact and Nutrient Adequacy of Derived Dietary Patterns in Vietnam. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 986241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, S.F.; Zhou, K.; Dai, S.X. Comparison and Recommendation of Dietary Patterns Based on Nutrients for Eastern and Western Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1066252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Nguyen, P.H.; Tran, L.M.; Huynh, P.N. Nutrition Transition in Vietnam: Changing Food Supply, Food Prices, Household Expenditure, Diet and Nutrition Outcomes. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 1141–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Bi, A.Z.; Medina-Lara, A.; Morrish, N.; Veettil, P.C. The Rural Food Environment and Its Association with Diet, Nutrition Status, and Health Outcomes in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries (Lmics): A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raneri, J.; Kennedy, G.; Nguyen, T.; Wertheim-Heck, S.; Do, H.; Haan, S.; Phuong, N.; Huong, L.; Mai, T.; Duong, T.; et al. Determining Key Research Areas for Healthier Diets and Sustainable Food Systems in Viet Nam; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, J.P.; Thakur, J.S.; Jeet, G.; Chawla, S.; Jain, S.; Prasad, R. Urban Rural Differences in Diet, Physical Activity and Obesity in India: Are We Witnessing the Great Indian Equalisation? Results from a Cross-Sectional Steps Survey. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, L.; Wey, H.; Meendering, J.; Specker, B. Differences in Physical Activity and Diet Patterns between Non-Rural and Rural Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Abu-Ali, G.; Huttenhower, C. The Healthy Human Microbiome. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Deng, F.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J. Identification of Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated with Longevity Provides a Promising Modulation Target for Healthy Aging. Gut Microbes 2019, 10, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdill, R.J.; Graham, S.P.; Rubinetti, V.; Ahmadian, M.; Hicks, P.; Chetty, A.; McDonald, D.; Ferretti, P.; Gibbons, E.; Rossi, M.; et al. Integration of 168,000 Samples Reveals Global Patterns of the Human Gut Microbiome. Cell 2025, 188, 1100–1118.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.A.; Boyle, K. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease in the Elderly. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2024, 26, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, L.; Spinewine, A.; Huang, A. The Challenge of Managing Drug Interactions in Elderly People. Lancet 2007, 370, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tap, J.; Lejzerowicz, F.; Cotillard, A.; Pichaud, M.; McDonald, D.; Song, S.J.; Knight, R.; Veiga, P.; Derrien, M. Global Branches and Local States of the Human Gut Microbiome Define Associations with Environmental and Intrinsic Factors. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.V. Gut Microbiome Composition and Diversity Are Related to Human Personality Traits. Hum. Microb. J. 2020, 15, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttenhower, C.; Gevers, D.; Knight, R.; Abubucker, S.; Badger, J.H.; Chinwalla, A.T.; Creasy, H.H.; Earl, A.M.; FitzGerald, M.G.; Fulton, R.S.; et al. Structure, Function and Diversity of the Healthy Human Microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, F.H.; Fåk, F.; Nookaew, I.; Tremaroli, V.; Fagerberg, B.; Petranovic, D.; Bäckhed, F.; Nielsen, J. Symptomatic Atherosclerosis Is Associated with an Altered Gut Metagenome. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Chatelier, E.; Nielsen, T.; Qin, J.; Prifti, E.; Hildebrand, F.; Falony, G.; Almeida, M.; Arumugam, M.; Batto, J.M.; Kennedy, S.; et al. Richness of Human Gut Microbiome Correlates with Metabolic Markers. Nature 2013, 500, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, N.W.; Ahern, P.P.; Cheng, J.; Heath, A.C.; Ilkayeva, O.; Newgard, C.B.; Fontana, L.; Gordon, J.I. Prior Dietary Practices and Connections to a Human Gut Microbial Metacommunity Alter Responses to Diet Interventions. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.D.; Chen, E.Z.; Baldassano, R.N.; Otley, A.R.; Griffiths, A.M.; Lee, D.; Bittinger, K.; Bailey, A.; Friedman, E.S.; Hoffmann, C.; et al. Inflammation, Antibiotics, and Diet as Environmental Stressors of the Gut Microbiome in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, E.; Franceschi, C.; Rampelli, S.; Severgnini, M.; Ostan, R.; Turroni, S.; Consolandi, C.; Quercia, S.; Scurti, M.; Monti, D.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Extreme Longevity. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokudome, S.; Ichikawa, Y.; Okuyama, H.; Tokudome, Y.; Goto, C.; Imaeda, N.; Kuriki, K.; Suzuki, S.; Shibata, K.; Jiang, J.; et al. The Mediterranean vs. the Japanese Diet. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetta, H.F.; Ramadan, Y.N.; Alharbi, A.A.; Alsharef, S.; Alkindy, T.T.; Alkhamali, A.; Albalawi, A.S.; El Amin, H. Gut Microbiome as a Target of Intervention in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pathogenesis and Therapy. Immuno 2024, 4, 400–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; D’Angelo, S. Gut Microbiota Modulation through Mediterranean Diet Foods: Implications for Human Health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Saha, B.; Mehta, O.; Anbumani, D.; Kumar, N.; Dayal, M.; Pant, A.; Kumar, P.; Saxena, S.; Allin, K.H.; et al. An Improved Method for High Quality Metagenomics DNA Extraction from Human and Environmental Samples. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadrosh, D.W.; Ma, B.; Gajer, P.; Sengamalay, N.; Ott, S.; Brotman, R.M.; Ravel, J. An Improved Dual-Indexing Approach for Multiplexed 16s Rrna Gene Sequencing on the Illumina Miseq Platform. Microbiome 2014, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhariwal, A.; Chong, J.; Habib, S.; King, I.L.; Agellon, L.B.; Xia, J. Microbiomeanalyst: A Web-Based Tool for Comprehensive Statistical, Visual and Meta-Analysis of Microbiome Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W180–W188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.J.; Morris, A.; Kayal, A.; Milošević, I.; Van, T.T.H.; Bajagai, Y.S.; Stanley, D. Pioneering Gut Health Improvements in Piglets with Phytogenic Feed Additives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The Silva Ribosomal Rna Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabwe, M.H.; Vikram, S.; Mulaudzi, K.; Jansson, J.K.; Makhalanyane, T.P. The Gut Mycobiota of Rural and Urban Individuals Is Shaped by Geography. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayeni, F.A.; Biagi, E.; Rampelli, S.; Fiori, J.; Soverini, M.; Audu, H.J.; Cristino, S.; Caporali, L.; Schnorr, S.L.; Carelli, V.; et al. Infant and Adult Gut Microbiome and Metabolome in Rural Bassa and Urban Settlers from Nigeria. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 3056–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, M.; Fridman, S.; Atamna-Ismaeel, N.; Izhaki, I. Rosenbergiella nectarea gen. nov., sp. nov., in the Family Enterobacteriaceae, Isolated from Floral Nectar. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63 Pt 11, 4259–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.G.; Fusieger, A.; Milião, G.L.; Martins, E.; Drider, D.; Nero, L.A.; de Carvalho, A.F. Weissella: An Emerging Bacterium with Promising Health Benefits. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2021, 13, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Alvarez, L.; Xu, H.; Martinez-Tellez, B. Influence of Exercise on the Human Gut Microbiota of Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, e00126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, V.D.; Vaccariello, E.D.; Murray, E.R.; Yu, K.E.; Knight, R.; Jeste, D.V.; Nguyen, T.T. The Gut Microbiome, Aging, and Longevity: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzemah-Shahar, R.; Turjeman, S.; Sharon, E.; Gamliel, G.; Hochner, H.; Koren, O.; Agmon, M. Signs of Aging in Midlife: Physical Function and Sex Differences in Microbiota. Geroscience 2024, 46, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C.; Donat, E.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Calabuig, M.; Sanz, Y. Imbalances in Faecal and Duodenal Bifidobacterium Species Composition in Active and Non-Active Coeliac Disease. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whorwell, P.J.; Altringer, L.; Morel, J.; Bond, Y.; Charbonneau, D.; O’Mahony, L.; Kiely, B.; Shanahan, F.; Quigley, E.M. Efficacy of an Encapsulated Probiotic Bifidobacterium Infantis 35624 in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeger, D.; O’Mahony, L.; Murphy, E.F.; Bourke, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Kiely, B.; Shanahan, F.; Quigley, E.M. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 Modulates Host Inflammatory Processes Beyond the Gut. Gut Microbes 2013, 4, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, J.L.; Ley, R.E. The Human Gut Bacteria Christensenellaceae Are Widespread, Heritable, and Associated with Health. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihelgas, S.; Ehala-Aleksejev, K.; Adamberg, S.; Kazantseva, J.; Adamberg, K. The Gut Microbiota of Healthy Individuals Remains Resilient in Response to the Consumption of Various Dietary Fibers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Mao, B.; Gu, J.; Wu, J.; Cui, S.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Blautia—A New Functional Genus with Potential Probiotic Properties? Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1875796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdi, A.; Lloyd, C.; Eri, R.; Van, T.T. Postbiotics: A Promising Approach to Combat Age-Related Diseases. Life 2025, 15, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Kim, K.-A.; Ahn, Y.-T.; Jeong, J.-J.; Huh, C.-S.; Kim, D.-H. Comparative Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Elderly People of Urbanized Towns and Longevity Villages. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Choi, C.W.; Shin, H.; Jin, S.P.; Bae, J.S.; Han, M.; Seo, E.Y.; Chun, J.; Chung, J.H. Comparison of the Gut Microbiota of Centenarians in Longevity Villages of South Korea with Those of Other Age Groups. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Takagi, T.; Inoue, R.; Kashiwagi, S.; Mizushima, K.; Tsuchiya, S.; Itoh, Y.; Okuda, K.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Adachi, A.; et al. Gut Microbiota Differences in Elderly Subjects between Rural City Kyotango and Urban City Kyoto: An Age-Gender-Matched Study. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2019, 65, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium Nucleatum: A Commensal-Turned Pathogen. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015, 23, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolstad, A.I.; Jensen, H.B.; Bakken, V. Taxonomy, Biology, and Periodontal Aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 9, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, J.; Yao, H.; Hu, H. Fusobacterium and Colorectal Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visca, P.; Seifert, H.; Towner, K.J. Acinetobacter Infection—An Emerging Threat to Human Health. IUBMB Life 2011, 63, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.K.; Hospenthal, D.R. Acinetobacter Infection in the Icu. Crit. Care Clin. 2008, 24, 237–248, vii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondinella, D.; Raoul, P.C.; Valeriani, E.; Venturini, I.; Cintoni, M.; Severino, A.; Galli, F.S.; Mora, V.; Mele, M.C.; Cammarota, G.; et al. The Detrimental Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on the Human Gut Microbiome and Gut Barrier. Nutrients 2025, 17, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, A.; Ostan, R.; Candela, M.; Biagi, E.; Brigidi, P.; Capri, M.; Franceschi, C. Gut Microbiota Changes in the Extreme Decades of Human Life: A Focus on Centenarians. Cell. Mol. Life 2017, 75, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, B.B.; Pettersson, S.; Melby, M.K.; Bosch, T.C.G. The Microbiome Mediates Environmental Effects on Aging. Bioessays 2019, 41, 1800257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, S.; Kang, J.X.; Wang, B. Insight into the Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Gut Microbiota: Impact of a Balanced Tissue Omega-6/Omega-3 Ratio. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1575323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, K.; Ma, K.; Luo, W.; Shen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, M.; Tong, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Roseburia Intestinalis: A Beneficial Gut Organism from the Discoveries in Genus and Species. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 757718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanai-Shacoori, Z.; Smida, I.; Bousarghin, L.; Loreal, O.; Meuric, V.; Fong, S.B.; Bonnaure-Mallet, M.; Jolivet-Gougeon, A. Roseburia spp.: A Marker of Health? Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, L.M.; Genthner, B.R.; Bryant, M.P. Syntrophic Association by Cocultures of the Methanol- and CO2-H2-Utilizing Species Eubacterium Limosum and Pectin-Fermenting Lachnospira Multiparus during Growth in a Pectin Medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1981, 42, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marounek, M.; Dušková, D. Metabolism of Pectin in Rumen Bacteria Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens and Prevotella ruminicola. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 29, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaruddin, A.I.; Hamid, F.; Koopman, J.P.R.; Muhammad, M.; Brienen, E.A.T.; van Lieshout, L.; Geelen, A.R.; Wahyuni, S.; Kuijper, E.J.; Sartono, E.; et al. The Bacterial Gut Microbiota of Schoolchildren from High and Low Socioeconomic Status: A Study in an Urban Area of Makassar, Indonesia. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Park, S.; Jun, Y.K.; Choi, Y.; Shin, C.M.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, N.; Lee, D.H. Evaluation of Bacterial and Fungal Biomarkers for Differentiation and Prognosis of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Arango, L.F.; Barrett, H.L.; Wilkinson, S.A.; Callaway, L.K.; McIntyre, H.D.; Morrison, M.; Dekker Nitert, M. Low Dietary Fiber Intake Increases Collinsella Abundance in the Gut Microbiota of Overweight and Obese Pregnant Women. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma Ashok, K.; Petrzelkova, K.; Pafco, B.; Jost Robinson Carolyn, A.; Fuh, T.; Wilson Brenda, A.; Stumpf Rebecca, M.; Torralba Manolito, G.; Blekhman, R.; White, B.; et al. Traditional Human Populations and Nonhuman Primates Show Parallel Gut Microbiome Adaptations to Analogous Ecological Conditions. mSystems 2020, 5, e00815-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.C.; Muzny, D.M.; McCormick, J.B.; Gibbs, R.A.; Fisher-Hoch, S.P.; Petrosino, J.F. 16s Gut Community of the Cameron County Hispanic Cohort. Microbiome 2015, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Ghosh, T.S.; Kedia, S.; Rampal, R.; Saxena, S.; Bag, S.; Mitra, R.; Dayal, M.; Mehta, O.; Surendranath, A.; et al. Analysis of the Gut Microbiome of Rural and Urban Healthy Indians Living in Sea Level and High Altitude Areas. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Wang, D.; Golzato, D.; Manghi, P.; Heidrich, V.; Fackelmann, G.; Zhernakova, D.V.; Kurilshikov, A.; Valles-Colomer, M.; et al. Global Genetic Diversity of Human Gut Microbiome Species Is Related to Geographic Location and Host Health. Cell 2025, 188, P3942–P3959.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, E.; Yasir, M.; Bachar, D.; Azhar, E.I.; Lagier, J.C.; Bibi, F.; Jiman-Fatani, A.A.; Alawi, M.; Bakarman, M.A.; Robert, C.; et al. Gut Microbiome and Dietary Patterns in Different Saudi Populations and Monkeys. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Babaei, P.; Ji, B.; Nielsen, J. Human Gut Microbiota and Healthy Aging: Recent Developments and Future Prospective. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2016, 4, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Li, R.; Lin, H.; Fu, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Su, M.; Huang, P.; Qian, J.; Jiang, F.; et al. Enriched Taxa Were Found among the Gut Microbiota of Centenarians in East China. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Li, K.; Sadd, B.M.; Guo, Y.; Zhuang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Evans, J.D.; Guo, J.; et al. Dynamic Changes of Gut Microbial Communities of Bumble Bee Queens through Important Life Stages. mSystems 2019, 4, e00631-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La-Ongkham, O.; Nakphaichit, M.; Nakayama, J.; Keawsompong, S.; Nitisinprasert, S. Age-Related Changes in the Gut Microbiota and the Core Gut Microbiome of Healthy Thai Humans. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtanova, D.A.; Klimenko, N.S.; Strazhesko, I.D.; Starikova, E.V.; Glushchenko, O.E.; Gudkov, D.A.; Tkacheva, O.N. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Gut Microbiota Composition in Moscow Long-Livers. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Martín, A.; García-Villalba, R.; González-Sarrías, A.; Romo-Vaquero, M.; Loria-Kohen, V.; Ramírez-de-Molina, A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Selma, M.V.; Espín, J.C. The Gut Microbiota Urolithin Metabotypes Revisited: The Human Metabolism of Ellagic Acid Is Mainly Determined by Aging. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 4100–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhong, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, Z.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Tang, S.; Han, X.; Lin, Y.; et al. Sex- and Age-Related Trajectories of the Adult Human Gut Microbiota Shared across Populations of Different Ethnicities. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kato, K.; Murakami, H.; Hosomi, K.; Tanisawa, K.; Nakagata, T.; Ohno, H.; Konishi, K.; Kawashima, H.; Chen, Y.A.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Gut Microbiota of a Healthy Population and Covariates Affecting Microbial Variation in Two Large Japanese Cohorts. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Becker, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, D.; Ma, X. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Dai, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, M.; Jiang, X.; Huang, Z.; Yu, H.; Huang, J.; et al. Altered Fecal Microbiota Composition in Older Adults with Frailty. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 696186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.Y.; Hong, S.; Kim, J.H.; Nam, Y.D. Association between Gut Microbiome and Frailty in the Older Adult Population in Korea. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, H.M.; Sardeli, A.V.; Conway, J.; Duggal, N.A.; Cavaglieri, C.R. Comparison between Frail and Non-Frail Older Adults’ Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 82, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirasawa, Y.; Isobe, J.; Hosonuma, M.; Tsurui, T.; Baba, Y.; Funayama, E.; Tajima, K.; Murayama, M.; Narikawa, Y.; Toyoda, H.; et al. Veillonella and Streptococcus Are Associated with Aging of the Gut Microbiota and Affect the Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1528521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.Y.; Hong, S.; Bang, S.J.; Chung, W.H.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Nam, Y.D. Gut Microbiome Structure and Association with Host Factors in a Korean Population. mSystems 2021, 6, e0017921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Qin, Q.; Yan, S.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Gao, X.; Ding, S. Comparison of the Gut Microbiota in Different Age Groups in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 877914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiman, J.; Luber, J.M.; Chavkin, T.A.; MacDonald, T.; Tung, A.; Pham, L.D.; Wibowo, M.C.; Wurth, R.C.; Punthambaker, S.; Tierney, B.T.; et al. Meta-Omics Analysis of Elite Athletes Identifies a Performance-Enhancing Microbe That Functions via Lactate Metabolism. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, E.; Benítez-Cabello, A.; Arenas-de Larriva, A.P.; Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M.; Pérez-Martínez, P.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Arroyo-López, F.N.; Garrido-Fernández, A. Application of Compositional Data Analysis to Study the Relationship between Bacterial Diversity in Human Faeces and Sex, Age, and Weight. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).