Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a common foodborne pathogen, posing significant concern due to the emergence of its multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. The aim of this study was to assess the antibiotic resistance profiles in S. aureus isolated from raw poultry, the associated resistance genes, and their ability to form biofilms. S. aureus was isolated and identified using conventional microbiological methods. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles were assessed using the disk diffusion method, and biofilm-forming ability was evaluated using the microtiter plate assay. The presence of antimicrobial resistance genes was determined by PCR. A total of 45 isolates were isolated. High resistance rates were observed against penicillin (88.9%), tetracycline (86.7%) and doxycycline (66.7%). Of the isolates, 71.1% were classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms, and 60% exhibited a multiple antibiotic resistance index greater than 0.2. PCR analysis revealed the presence of the resistance genes blaZ (86.7%), mecA (27.3%), tet(M) (46.2%), tet(K) (35.9%), tet(S) (59%), erm(B) (51.9%), and erm(C) (59.3%). A total of 44 isolates were biofilm producers: 46.7% were weak producers, 46.7% were moderate producers, and 4.4% were strong producers. These findings highlight a significant public health concern, emphasizing the need for stringent hygiene practices and continuous monitoring to limit the spread of resistant pathogens through the food chain.

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a commensal and opportunistic bacterium with a broad host range capable of causing a wide range of infections, from minor skin and soft tissue infections to severe, life-threatening conditions such as sepsis and toxic shock syndrome [1]. Furthermore, it is a significant foodborne pathogen, recognized as one of the mean causes of food poisoning. Globally, it is classified as the third leading causative agent of foodborne illnesses, following Salmonella and Vibrio parahaemolyticus [2,3]. One of the most critical public health concerns in recent decades is the rapid emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistant (AMR) bacteria. In poultry farming, antibiotics are routinely used not only for the treatment of infections but also as growth promoters and for prophylactic purposes [4]. The overuse and often inappropriate use of antimicrobials in the poultry sector exerts strong selective pressure that contributes to the emergence of resistant bacterial strains. These AMR strains can be transmitted to humans through the food chain, primarily via zoonotic pathogens many of which are foodborne bacteria present in contaminated animal-derived products such as meat and meat products, thereby posing a significant risk to public health [5,6,7]. Among the key characteristics of S. aureus is its remarkable ability to adapt to varying environmental conditions and rapidly acquire resistance to multiple antibiotic agents [3,8]. In recent years, multidrug-resistant S. aureus strains have been increasingly reported in foodborne outbreaks and isolated from a wide range of food products, particularly chicken meat [3,9]. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has gained significant attention due to its resistance to β-lactam antibiotics and its ability to acquire resistance to additional classes of antimicrobial agents, making infections caused by this pathogen difficult to treat [9,10,11]. The zoonotic transmission of MRSA from food-producing animals to humans has been well-documented and represents a significant public health concern [1]. In addition, S. aureus has the ability to form biofilms which can develop on a variety of biotic and abiotic surfaces such as human tissues, medical devices, food products, and food processing equipment [8,12]. Biofilm formation begins with attachment of bacterial cells to the surface, followed by the phases of accumulation, maturation, and eventual detachment, which facilitate the dissemination of staphylococci [13]. The biofilm matrix protects bacteria from cleaning and disinfection procedures, impedes the penetration of antimicrobial agents, and enables the bacteria to escape host immune responses, thereby allowing the bacteria to persist in the environment [14]. In meat processing facilities, the formation of biofilms on contaminated surfaces creates a persistent source of contamination posing a significant challenge to the food industry [15]. Slaughterhouses are considered a primary point of contamination in the meat production chain, and chicken meat is increasingly recognized as a reservoir for antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. This study was conducted to isolate S. aureus from raw chicken meat collected at slaughterhouses, evaluate the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of the isolates, detect selected resistance genes, and assess their biofilm-forming ability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

A total of 130 chicken meat samples were randomly collected from different slaughterhouses located in Setif Province, Eastern Algeria, between September 2021 and January 2023. The samples were aseptically sampled, placed in sterile sampling bags and immediately transported to the Laboratory of Applied Microbiology, University of Setif 1, for analysis, under refrigerated conditions using an ice box.

2.2. Isolation and Identification of S. aureus

The isolation of S. aureus was carried out following the method described by Parvin et al. [16], with modifications. Briefly, ten grams of fresh chicken meat were aseptically cut into small pieces using a sterile tool and transferred into 90 mL of buffered peptone water. The mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Following incubation, a loopful of the enrichment broth was streaked onto Mannitol Salt Agar (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy) and further incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Two to three putative colonies of S. aureus from each plate were streaked on Nutrient Agar (TM-Media, Delhi, India) to obtain pure isolates. Suspected colonies were further identified on the basis of the phenotypic characteristics observed in selective media such as Mannitol Salt Agar and Baird-Parker Agar (VWR, Leuven, Belgium) supplemented with 5% tellurite emulsion (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), Gram staining, catalase and coagulase tests. Further confirmation was achieved by the API Staph kit (BioMerieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France). Upon confirmation, one representative S. aureus isolate from each positive sample was selected for subsequent analyses. The pure cultures were preserved in 30% glycerol and stored at −20 °C until phenotypic antimicrobial resistance testing and DNA extraction.

2.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Test

All the isolated cultures were examined for their patterns of antimicrobial resistance to 19 antibiotics belonging to 13 classes using Kirby Bauer Disc diffusion method on Mueller Hinton Agar according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines [17]. The antibiotics tested were as follows: β-lactams: Penicillins [Amoxicilline/Clavulanic acid (AMC), Penicillin (P), Ampicillin (Amp)] and Cephalosporins [Cefoxitin (FOX), Fosfomycin (Fosfomycin (FF)]; Glycopeptides [Vancomycin (VAN)]; Aminosides [Kanamycin (K), Tobramycin (TOB), Gentamycin (CN)]; Macrolids [Erythromycin (E)]; Lincosamids [Clindamycin (CD)], Tetracyclines [Doxycycline (DO), Tetracycline (Tet)]; Fluoroquinolones [Ciprofloxacin (Cip), Ofloxacin (OFX)]; Rifampicin [Rifampicin (RD)]; Diaminopyrimidines/Sulfamides [Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (SXT)]; Phenicols [Chloramphenicol (C)]; Fusidic acid (FA). The diameter of inhibition zones surrounding each antibiotic disk was measured, and bacterial susceptibility was subsequently classified as sensitive or resistant in accordance with the breakpoints established by EUCAST. Antimicrobial resistant bacterial isolates were classified into three categories: multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, which are non-susceptible to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories; extensively drug-resistant (XDR) bacteria, which are non-susceptible to at least one agent in all but two or fewer antimicrobial categories; and pan-drug-resistant (PDR) bacteria, which are non-susceptible to all agents in all antimicrobial categories [18]. The multiple antibiotic resistances (MAR) index was determined as described by Anihouvi et al. [19].

2.4. DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA from all bacterial isolates was extracted using the boiling method [20]. Briefly, two to three colonies from a pure overnight culture grown on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar were suspended in 300 µL of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8). The suspension was then incubated in a dry bath (HB 120-C, Argolab, Carpi, Italy) at 100 °C for 12 min. After that, the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min using a Rotofix 32A centrifuge (Hettich, Milan, Italy). Subsequently, the supernatant was transferred to new tubes and stored at −20 °C for further use. The extracted DNA was assessed for quantity and purity using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). DNA samples were then amplified via endpoint PCR using the universal prokaryotic primer pair 388f–518r [21] to verify successful bacterial DNA extraction.

2.5. PCR Detection of AR Genes

All isolates exhibiting phenotypic resistance were screened for the presence of AR genes associated with resistance to β-lactams (blaZ, mecA), tetracycline [(tet(K), tet(M), tet(O), tet(S)], erythromycin [(erm(A), erm(B), erm(C)], vancomycin (vanA, vanB) [22], and aminoglycosides [aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia] [23] using end-point PCR. DNA from bacterial references, each carrying one of the AR genes under study, was used as a positive control in each PCR [24]. The amplification reactions were carried out in a final volume of 25 µL each consisting of 0.15 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (5U/µL) (SibEnzyme Ltd., Novosibirsk, Russia), 2 µL of 10X SE-Taq polymerase buffer, 0.5 µL of 10 mM dNTPs, 1 µL of each 10 µM primer, 3 µL of extracted DNA, and sterile, nuclease-free water was added to adjust the final volume. The primers, expected amplification product sizes, and PCR conditions are listed in Table 1. To assess the presence or absence of the tested AR genes in the isolates, five microliters of PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on a 1.5% (w/v) agarose gel prepared in 0.5× Tris/Borate/EDTA (TBE) buffer (VWR Chemicals), containing 0.5 μg/mL GelRed® Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (10,000× in water; Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA). Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 50 min. The PCR products were visualized under a UV transilluminator and photographed. The expected fragment sizes for each AR gene were verified by comparison with a 100 bp DNA ladder (HyperLadder™ 100 bp, Bioline, London, UK).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial resistance genes targets, primers, and PCR conditions.

2.6. Biofilm Formation

S. aureus isolates were screened for their ability to form biofilm using 96 microtiter plate method according to [35] with slight modifications. Briefly, two or three colonies from a pure fresh culture were transferred into BHI broth (Condalab, Madrid, Spain) supplemented with 1% glucose and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in sterile medium. 200 μL of each bacterial suspension was inoculated in duplicate into 96-well sterile polystyrene microplates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. 200 µL of fresh broth with 1% glucose served as the negative control, and a strain of S. aureus 29213 used as the positive control. The bacterial suspensions were aspirated from each well and washed 3 times with 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline. The wells were air-dried and then stained with 200 μL of 0.1% crystal violet for 15 min. After removing the crystal violet solution (Biochen Chemopharma, Cosne-sur-Loire, France), the wells were rinsed with water, and the plates were kept for drying. 200 uL of ethanol (95%) was added to all the wells, then the optical densities (ODs) of the plates were measured at 570 nm using an ELISA reader. The cut-off for OD was established as follows:

where c is the control, nc is the negative control, and SD is the standard deviation.

ODc = Average ODnc + 3 × SDnc

The isolates were classified into four categories as follows: A: non-biofilm producer (OD ≤ ODc); B: weak biofilm producer (ODc < OD ≤ 2 × ODc); C: moderate biofilm producer (2 × ODc < OD ≤ 4 × ODc); and D: strong biofilm producer (4 × ODc < OD).

2.7. Statistics

GraphPad Prism 5.03 was used to design the histograms, while statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 21.0 statistical software. The Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact two-tailed test were used to assess any significant correlations between biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance patterns, and antibiotic resistance genes. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of S. aureus

The present study was conducted to evaluate the prevalence of Staphylococcus and its resistance profiles from raw chicken meat samples. This microorganism was present in 34.62% of samples based on phenotypic and biochemical characterization.

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

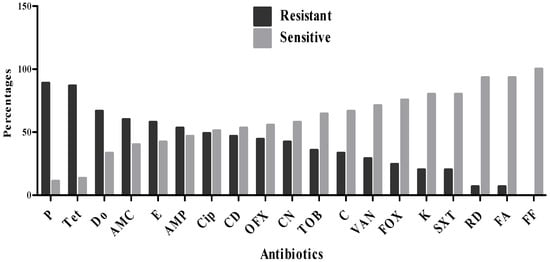

Th antibiogram results revealed varying levels of susceptibility and resistance among the 45 S. aureus isolates to the tested antibiotics (Figure 1, Table 2). The highest resistance rates were observed against penicillin (88.9%), tetracycline (86.7%), doxycycline (66.7%), amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (60%), and erythromycin (57.8%). Moderate resistance levels were seen for ampicillin (53.3%), ciprofloxacin (48.9%), clindamycin (46.7%), ofloxacin (44.4%), gentamicin (42.2%), and tobramycin (35.6%). Lower resistance rates were recorded for chloramphenicol (33.3%), vancomycin (28.9%), cefoxitin (24.4%), as well as kanamycin and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (each at 20%). In contrast, the highest susceptibility rates were observed for fosfomycin (100%), rifampicin (93.3%), and fusidic acid (93.3%).

Figure 1.

Resistance profile of S. aureus strains.

Table 2.

Prevalence of antibiotic resistance among S. aureus isolates.

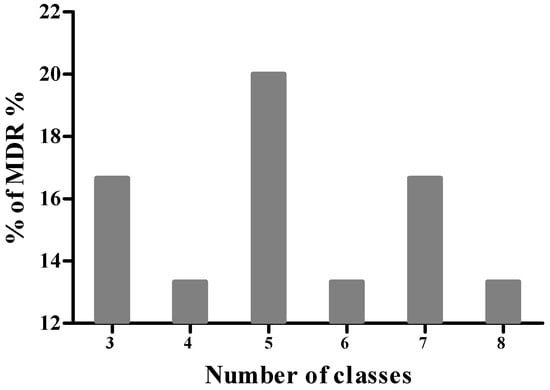

Based on the results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing, none of the isolates were classified as XDR or PDR. However, 71.11% of isolates were identified as MDR, exhibiting resistance to three or more classes of antibiotics. Among the latter isolates, 12.5% were resistant to 3 antibiotic classes, 18.8% to four classes, and 9.4% to five classes (Figure 2). Furthermore, 15.6%, 12.5%, and 18.8% of the isolates demonstrated resistance to six, seven, and eight antibiotic classes, respectively. Notably, 12.5% of the MDR isolates showed resistance to as many as 9 antibiotic classes.

Figure 2.

Distribution of multidrug-resistant (MDR) S. aureus isolates.

The MAR index was calculated for each isolate (Table 3), ranging from 0.1 to 0.78, with an average value of 0.4. Notably, 88.88% of the isolates exhibited a MAR index greater than 0.2. All 45 isolates exhibited distinct antibiotic resistance patterns, which are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antibiotic resistance profiles and MAR index of S. aureus isolates.

3.3. Biofilm-Forming Ability

Out of the S. aureus isolates examined, only one isolate was identified as a non-biofilm producer (Table 4), whereas the remaining 44 isolates (97.8%) were able to produce biofilm (Table 4). Among the latter microorganisms, 46.7% of isolates exhibited weak biofilm formation, an equal proportion (46.7%) showed moderate biofilm production, and only 2 isolates were classified as strong biofilm producers.

Table 4.

Distribution of S. aureus non-producer and producer biofilm.

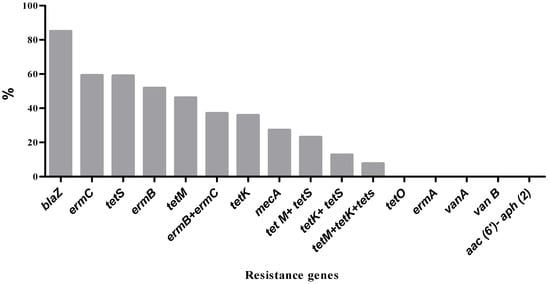

3.4. Detection of Resistance Genes

Among the isolates phenotypically identified as MRSA based on resistance to cefoxitin, only three isolates were found to harbor the mecA resistance gene. The blaZ gene, which confers resistance to penicillin, was the most frequently detected, present in approximately 86.7% of penicillin-resistant isolates (Figure 3). Tetracycline-resistant isolates were screened for four tet resistance genes. The tet(S) gene was the most prevalent, detected in 59% of the isolates, followed by tet(M) (46.2%) and tet(K) (35.9%). None of the isolates carried the tet(O) gene. Some isolates possessed multiple tet resistance genes, including combinations such as tet(M) + tet(S) (23.1%), tet(K) + tet(S) (12.8%), and tet(M) + tet(K) + tet(S) (7.7%). Regarding erythromycin resistance, three resistance genes were tested. The erm(C) gene was identified in 59.3% of resistant isolates, while erm(B) was present in 51.9%. The erm(A) gene was not detected in any of the isolates. Notably, 37% of the isolates carried both erm(B) and erm(C) genes. Genes associated with vancomycin resistance (vanA, vanB) and aminoglycoside resistance aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia were not detected in any of the assayed isolates.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes among S. aureus isolates.

3.5. Statistical Correlations

3.5.1. Association of Biofilm Formation with Antibiotic Resistance Patterns in S. aureus Isolates

The association between biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance patterns was evaluated. Among the non-MDR S. aureus isolates, 69.2% were weak biofilm producers, while 30.8% were moderate biofilm producers. In contrast, among MDR isolates, 53.1% were moderate producers, followed by 37.5% weak producers, 6.3% strong producers, and 3.1% non-producers. A statistically significant association was observed between biofilm formation and multidrug-resistant strains at p = 0.0001 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Biofilm formation among non-MDR and MDR S. aureus.

3.5.2. Association of Biofilm Formation with Antibiotic Resistance Genes

The distribution of various resistance genes with respect to biofilm formation in S. aureus isolates are presented in Table 6. Although there was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) in the prevalence of resistance genes across the different categories of biofilm-producing isolates, these genes were generally more frequently detected in weak and moderate biofilm producers.

Table 6.

Distribution of resistance genes based on categories of biofilm formation.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to assess the prevalence and to characterize the phenotypic and genotypic profiles of antibiotic resistance in S. aureus isolates from raw chicken meat collected from slaughterhouses in Eastern Algeria. Of the 130 samples analyzed, 34.6% were contaminated with S. aureus. These results are closely aligned with those of a previous study conducted in Algeria, which reported that 46.66% of chicken meat samples collected from slaughterhouses were positive for S. aureus [36]. Similarly, in Korea, 43.3% of chicken meat samples from slaughterhouses were found to be contaminated with this food-borne pathogen [37]. However, in Morocco, the prevalence was considerably lower, with only 15.92% of chicken meat samples testing positive for S. aureus [38]. The presence of S. aureus in the meat is often indicative of insufficient control measures and inadequate personal hygiene practices [39]. These differences in the prevalence of S. aureus may be attributed to various factors, including study design, sampling techniques, sample size, identification methods, and slaughterhouse equipment used (e.g., knives, slicing machines, wiping cloths) [39,40]. The management of staphylococcal infection relies on antimicrobial therapy, which often fails because of the strong resistance of the bacteria to certain drugs [16]. In the present study, among penicillins, the highest resistance was observed against penicillin G (88.9%), followed by amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (60%) and ampicillin (53.3%). Similar findings have been reported in previous studies, where S. aureus isolates from chicken meat exhibited high levels of resistance to penicillin G [41,42,43]. Other authors [38,42] reported that 100% of S. aureus isolates were resistant to ampicillin. Consistent with our findings, Islam and colleagues [44] reported a resistance rate of 61.54% to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. S. aureus is recognized for its notable resistance to the penicillin class of antimicrobials, which has been documented in Gram-positive bacteria since 1940s. Cefoxitin is used as a reliable indicator for the detection of methicillin resistance [6]. Based on the results of resistance to cefoxitin, 24.4% of S. aureus isolates were identified as MRSA. A comparable prevalence of MRSA in chicken meat has been reported in previous studies, including 19.4% in Benin and 20.8% in South Africa [19,45]. In contrast, a significantly higher prevalence rate of 63% and 42,31% has been reported in Pakistan and Bangladesh, respectively [6,44]. In the tetracycline class, a notably high resistance rate was observed against tetracycline (86.7%), followed by doxycycline (66.7%). These findings are consistent with those of [38,41] who reported tetracycline resistance in S. aureus isolated from fresh chicken meat at rates of 80.4% and 100%, respectively. Furthermore, our results align with those of [46] regarding resistance to doxycycline. The resistance to tetracycline was not surprising, as it is extensively used in poultry farms due to its low price and minimal side effects to promote growth [47]. The observed resistance to erythromycin (57.8%) and clindamycin (46.7%) corroborates with the findings of [48]. Among the fluoroquinolones tested in this study, moderate levels of resistance were observed against ciprofloxacin (48.4%) and ofloxacin (44.4%). Compared to the findings of other studies conducted in Algeria, both antibiotics showed lower resistance rates, with 14.28% of S. aureus isolates from chicken meat resistant to ofloxacin [49], and 13% and 19% of isolates from artisanal sausage resistant to ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin, respectively [50]. Our results indicated that resistance to gentamicin (42.2%) was notably high among the aminoglycoside class of antibiotics, contrasting with earlier studies conducted in the same country, which reported lower resistance rates to this antibiotic [51,52]. Despite the official prohibition of chloramphenicol by the Algerian government, 33% of the isolates demonstrated resistance to this antibiotic. This observation may be explained by the illicit use of chloramphenicol in poultry farming [50]. Fortunately, the isolates in this study demonstrated high susceptibility to fosfomycin, rifampicin, fusidic acid, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and vancomycin. The high sensitivity observed against these antibiotics may be due to their limited or absent application in veterinary medicine, which reduces the selective pressure for resistance development. However, the variation in antibiotic resistance rates between and within countries may be attributed to differences in animal husbandry practices, sanitary conditions, and the types of antimicrobials used on farms [53]. All S. aureus isolates were resistant to at least one of the antibiotics tested. Furthermore, 71.11% of the isolates exhibited multidrug resistance. These findings are consistent with those reported by Li and colleagues [9] and Nacer and colleagues [38], who observed that 99.7% and 100% of S. aureus isolates, respectively, were resistant to at least one antibiotic. However, both studies reported higher rates of multidrug resistance compared to the findings of our study. The MAR index serves as a valuable tool for evaluating the potential health risks associated with antimicrobial resistance in bacteria and for determining whether bacterial isolates originate from environments characterized by low (MAR index ≤ 0.2) or high (MAR index > 0.2) antibiotic usage. The MAR index is calculated as the ratio of the number of antibiotics to which an organism exhibits resistance to the total number of antibiotics tested [54]. In this study, MAR index values exceeding the threshold of 0.2 were observed in 88.88% of the isolates, indicating that these bacteria likely originated from high-risk sources where multiple antibiotics are frequently used, potentially due to contamination of human or animal origin [19]. MRSA has emerged as a significant food safety concern and represents a major challenge in healthcare. The confirmation of MRSA is based on the detection of the mecA gene, a highly conserved genetic determinant among staphylococcal species, which serves as a reliable biomarker for methicillin resistance [6,16]. In this study, only three of the phenotypically cefoxitin-resistant isolates were found to harbor the mecA resistance gene. The isolates that lack the mecA gene may exhibit resistance due to the presence of the mecC gene, which was not investigated in our study [55]. In close agreement with our findings, previous research conducted in Algeria reported that, among 30 phenotypically identified MRSA isolates from various food sources, only 3 strains carried the mecA gene [52]. However, in another study, approximately half of the MRSA isolates recovered from food sources were found to harbor the mecA gene [56]. Resistance to penicillin and its analogues in S. aureus is primarily mediated by the production of β-lactamase, encoded by the blaZ gene [57,58]. This resistance gene was frequently detected among the penicillin-resistant isolates in our study, which is in concordance with the findings of Igbinosa et al. [15]. The resistance to tetracycline in S. aureus is mainly due to two mechanisms: active efflux mediated by tet(K) and ribosomal protection conferred by tet(M), tet(O), and tet(S) genes [55,59]. The most frequently detected genes associated with tetracycline resistance in other studies were tet(K) and tet(M), which is consistent with our findings [15,43,60]. However, our isolates also harbored the tet(S) gene, which was the most prevalent. The absence of the tet(O) gene in all tested isolates aligns with the findings reported by Zehra and colleagues [10].

The erythromycin ribosomal methylase (erm) genes confer resistance not only to macrolides but also to lincosamides and streptogramin B by encoding methyltransferases that methylate the 23S rRNA of the 50S ribosomal subunit [61,62]. In contrast to the findings of Chouaib et al. [52] which identified only the erm(C) gene, the erythromycin-resistant isolates in the present study harbored erm(C) and/or erm(B). A previous study conducted in Algeria reported that S. aureus isolates from clinical samples carried erm(C) or erm(A), the latter of which was completely absent in our isolates [63]. One of the primary mechanisms by which staphylococci develop resistance to aminoglycosides is the inactivation of the antibiotic by aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs). These enzymes are encoded by various resistance genes, such as aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia, which was absent in all aminoglycoside-resistant isolates examined in our study. The observed resistance may therefore be attributed to the presence of other AME genes not investigated in this study or to reduced permeability of the bacterial cell wall [55,64,65]. Vancomycin is considered a last-resort antibiotic, primarily reserved for the treatment of severe infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria, particularly multidrug-resistant organisms such as MRSA. However, S. aureus has developed resistance mechanisms against vancomycin, most notably through the acquisition of van gene clusters, especially the vanA and vanB genes [66,67]. In this study, none of the vancomycin-resistant isolates harbored the vanA or vanB genes, which contrasts with the findings of previous research. Elshebrawy and colleagues [66] reported the presence of the vanA gene in S. aureus isolates obtained from chicken carcasses, sandwiches, and buffalo milk, while the vanB gene in S. aureus isolates from foods of animal origin. S. aureus may employ alternative mechanisms to resist vancomycin, such as increasing the thickness of the bacterial cell wall, which limits the antibiotic’s access to its target site [67,68]. One of the key virulence factors of S. aureus is its ability to form a complex extracellular polymeric biofilm, which enables the bacteria to survive under various hostile environmental conditions. The biofilm offers protection against standard disinfection procedures, including detergents and sanitizing agents, as well as environmental stressors, host immune responses, and antimicrobial treatments. As a result, biofilm formation plays a crucial role in persistent contamination and chronic infections across clinical and environmental settings [46,69,70,71]. In the present study, the biofilm forming test revealed that 97.8% of the isolates were able to form biofilms. Among these, 4.4% were classified as strong biofilm producers, 46.7% as moderate producers, and 46.7% as weak or low-level producers. These findings are in line with previous studies from Algeria, where all S. aureus isolates recovered from various food sources demonstrated biofilm-forming capacity using the same Method [11,71]. Similarly, in Egypt, 60% of MRSA isolates from raw chicken meat were reported as biofilm producers, with nearly all showing strong biofilm-forming potential [46]. In Nigeria, Igbinosa et al. [15] also reported that 76.36% of MRSA isolates obtained from poultry meat were capable of biofilm production.

5. Conclusions

This study reveals a high prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Staphylococcus aureus with strong biofilm-forming ability in raw chicken meat from slaughterhouses in the Setif province. The detection of MRSA isolates, multiple resistance genes, and elevated MAR index values indicates that poultry meat constitutes an important reservoir of antibiotic-resistant S. aureus, representing a serious threat to public health. These results emphasize the urgent necessity for comprehensive control actions—including rigorous hygiene measures in slaughterhouses, stricter regulation of antibiotic use in poultry production (particularly for critically important antimicrobials), and the establishment of a national antimicrobial resistance surveillance system. Moreover, the integration of alternative strategies such as probiotics, bacteriophage therapy, and vaccination should be prioritized. Implementing evidence-based interventions, modeled after successful programs in the EU and other countries, is essential to safeguard public health and strengthen food safety in Algeria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E., L.A., N.B. and Y.B.; methodology, F.B., M.K. and A.O.; validation, Y.B., M.R. and B.-H.J.; formal analysis, C.M., F.B. and Y.B.; investigation, F.B., M.E., N.B. and A.B.; resources, L.A., V.M., A.O., L.A., M.R., B.-H.J. and H.-J.A.; data curation, F.B., M.E. and N.B.; writing, original draft preparation, F.B., M.E. and N.B.; writing, review and editing, Y.B., A.O., L.A., V.M., M.R., B.-H.J. and H.-J.A.; visualization, Y.B.; supervision, A.O., L.A., V.M., B.-H.J. and Y.B.; project administration, B.-H.J. and Y.B.; funding acquisition, B.-H.J., L.A. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been supported by the Midcareer Research Program (Grant No. RS-2025-00520940) of the Ministry of Education and the Government of the Republic of Korea. Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-957), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The Department of Agricultural, Food, and Environmental Sciences (D3A), Università Politecnica delle Marche (UNIVPM) and the and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, Algeria.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in the published article, and additional raw data can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study has been supported by the Midcareer Research Program (Grant No. RS-2025-00520940) of the Ministry of Education and the Government of the Republic of Korea. The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-957), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Szabó, Á.; Jerzsele, Á.; Kovács, L.; Kerek, Á. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Commensal Staphylococcus spp. Isolates from Chickens in Hungarian Poultry Farms Between 2022 and 2023. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Ghany, W.A. Staphylococcus aureus in Poultry, with Special Emphasis on Methicillin-Resistant Strain Infection: A Comprehensive Review from One Health Perspective. Int. J. One Health 2021, 7, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand, S.; Haeili, M.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Molecular Typing and Drug Resistance Patterns of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Raw Beef and Chicken Meat Samples. Iran. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 14, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanlıbaba, P. Prevalence, Antibiotic Resistance, and Enterotoxin Production of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Retail Raw Beef, Sheep, and Lamb Meat in Turkey. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 361, 109461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, O.V.A.; Behruznia, M.; Preuss, A.L.; O’Brien, C.L. Diversity of Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria Isolated from Australian Chicken and Pork Meat. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1347597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, A.; Samad, M.; Saddam; Basharat, N.; Ali, S.; Roohullah; Saad, Z.; Khan, A.N.; Ahmad, Y.; Khan, A.; et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Slaughter Houses and Meat Shops in Capital Territory of Pakistan During 2018–2019. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 577707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Machado, C.; Alonso-Calleja, C.; Capita, R. Prevalence and types of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in meat and meat products from retail outlets and in samples of animal origin collected in farms, slaughterhouses and meat processing facilities. A review. Food Microbiol. 2024, 123, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titouche, Y.; Akkou, M.; Djaoui, Y.; Chergui, A.; Mechoub, D.; Bentayeb, L.; Fatihi, A.; Nia, Y.; Hennekinne, J.-A. Investigation of Biofilm Formation Ability and Antibiotic Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Food Products. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2024, 22, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, P.; Fu, C.; Meng, J.; Wang, X. Characterization of Toxin Genes and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus from Retail Raw Chicken Meat. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, A.; Gulzar, M.; Singh, R. Assessment of Correlation Between Phenotypic and Genotypic Resistance Profile of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Meat Samples of Punjab, India. Haryana Vet. 2020, 59, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Titouche, Y.; Akkou, M.; Campaña-Burguet, A.; González-Azcona, C.; Djaoui, Y.; Mechoub, D.; Fatihi, A.; Bouchez, P.; Bouhier, L.; Houali, K.; et al. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Nasal Samples of Healthy Dairy Goats in Algeria. Pathogens 2024, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limoli, D.H.; Jones, C.J.; Wozniak, D.J. Bacterial Extracellular Polysaccharides in Biofilm Formation and Function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torky, H.A. Risk of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Poultry Meat of Chicken with Arthritis in Poultry Farms. J. Adv. Vet. Res. 2023, 13, 904–909. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, C.; Shang, D.; Yang, J.; Chen, B.; Chang, J.; Jin, F.; Shi, C. Prevalence of Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates with Strong Biofilm Formation Ability among Animal-Based Food in Shanghai. Food Control. 2020, 112, 107106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbinosa, E.O.; Beshiru, A.; Igbinosa, I.H.; Ogofure, A.G.; Ekundayo, T.C.; Okoh, A.I. Prevalence, Multiple Antibiotic Resistance, and Virulence Profile of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Retail Poultry Meat from Edo, Nigeria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1122059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, M.S.; Ali, Y.; Talukder, S.; Nahar, A.; Chowdhury, E.H.; Rahman, T.; Islam, T. Prevalence and Multidrug Resistance Pattern of Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus Isolated from Frozen Chicken Meat in Bangladesh. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUCAST. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Växjö, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Disk_test_documents/2022_manuals/Manual_v_10.0_EUCAST_Disk_Test_2022.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant, and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anihouvi, D.G.H.; Koné, K.M.; Anihouvi, V.B.; Mahillon, J. Sanitary Quality and Bacteriological Antibiotic-Resistance Pattern of Frozen Raw Chicken Meat Sold in Retail Market in Benin. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.F.D.; Paim, T.G.D.S.; Reiter, K.C.; Rieger, A.; D’azevedo, P.A. Evaluation Of Four Different Dna Extraction Methods In Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Clinical Isolates. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2014, 56, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S Ribosomal DNA Amplification for Phylogenetic Study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, V.; Osimani, A.; Aquilanti, L.; Tavoletti, S.; Garofalo, C.; Polverigiani, S.; Litta-Mulondo, A.; Cocolin, L.; Ferrocino, I.; Di Cagno, R.; et al. Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Fecal DNA of Healthy Omnivores, Ovo-Lacto Vegetarians, and Vegans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1601098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanović, V.; Cardinali, F.; Aquilanti, L.; Maoloni, A.; Garofalo, C.; Zarantoniello, M.; Olivotto, I.; Riolo, P.; Ruschioni, S.; Isidoro, N.; et al. Quantitative Assessment of Transferable Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Fed Hermetia illucens-Based Feed. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 277, 114978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, V.; Roncolini, A.; Cardinali, F.; Garofalo, C.; Aquilanti, L.; Riolo, P.; Ruschioni, S.; Corsi, L.; Isidoro, N.; Zarantoniello, M.; et al. Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Hermetia illucens Larvae Fed Coffee Silverskin Enriched with Schizochytrium limacinum or Isochrysis galbana Microalgae. Genes 2021, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Vignaroli, C.; Zandri, G.; Aquilanti, L.; Bordoni, D.; Osimani, A.; Clementi, F.; Biavasco, F. Direct Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Specimens of Chicken and Pork Meat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 113, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminov, R.I.; Garrigues-Jeanjean, N.; Mackie, R.I. Molecular Ecology of Tetracycline Resistance: Development and Validation of Primers for Detection of Tetracycline Resistance Genes Encoding Ribosomal Protection Proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsvik, B.; Olsen, I.; Tenover, F.C. Detection of Tet (M) and Tet (Q) Using the Polymerase Chain Reaction in Bacteria Isolated from Patients with Periodontal Disease. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 1995, 10, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.-K.; Martin, I.; Alfa, M.; Mulvey, M. Multiplex PCR for the Detection of Tetracycline-Resistant Genes. Mol. Cell. Probes 2001, 15, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, J.; Grebe, T.; Tait-Kamradt, A.; Wondrack, L. Detection of Erythromycin-Resistant Determinants by PCR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 2562–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutka-Malen, S.; Evers, S.; Courvalin, P. Detection of Glycopeptide Resistance Genotypes and Identification to the Species Level of Clinically Relevant Enterococci by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Predari, S.C.; Ligozzi, M.; Fontana, R. Genotypic Identification of Methicillin-Resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991, 35, 2568–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, K.; Minamide, W.; Wada, K.; Nakamura, E.; Teraoka, H.; Watanabe, S. Identification of Methicillin-Resistant Strains of Staphylococci by Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1991, 29, 2240–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, F.; Picard, F.J.; Grenier, L.; Roy, P.H.; Ouellette, M.; Bergeron, M.G. Multiplex PCR Assays for the Detection of Clinically Relevant Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Staphylococci Isolated from Patients Infected after Cardiac Surgery. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 46, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Guo, X.; Yan, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, B.; Ge, F.; Ye, B. A Comprehensive Analysis on Spread and Distribution Characteristic of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Livestock Farms of Southeastern China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanović, S.; Vuković, D.; Hola, V.; Bonaventura, G.D.; Djukić, S.; Ćirković, I.; Ruzicka, F. Quantification of Biofilm in Microtiter Plates: Overview of Testing Conditions and Practical Recommendations for Assessment of Biofilm Production by Staphylococci. APMIS 2007, 115, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guergueb, N.; Alloui, N.; Ammar, A.; Bennoune, O. Effect of Slaughterhouse Hygienic Practices on the Bacterial Contamination of Chicken Meat. Sci. J. Vet. Adv. 2014, 3, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, H.-M.; Lee, A.-L.; Jung, S.-C.; Kim, M.-N.; Jang, G.-C.; Wee, S.-H.; Lim, S.-K. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus and Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Bovine Mastitis in Korea. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2011, 8, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacer, S.; El Ftouhy, F.Z.; Derqaoui, S.; Khayli, M.; Nassik, S.; Lkhider, M. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance of Salmonella spp. and Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Broiler Chicken Meat in Modern and Traditional Slaughterhouses of Morocco. World’s Vet. J. 2022, 12, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaharn, K.; Pichpol, D.; Meeyam, T.; Harintharanon, T.; Lohaanukul, P.; Punyapornwithaya, V. Bacterial Contamination of Chicken Meat in Slaughterhouses and the Associated Risk Factors: A Nationwide Study in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, K.M.; Amer, A.M.; Badr, J.M.; Saad, A.S.A. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance Profile of Staphylococcus Species in Chicken and Beef Raw Meat in Egypt. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2015, 12, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Guzman, M.L.C.; Manzano, R.M.E.; Monjardin, J.F.B. Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria in Raw Chicken Meat Sold in a Public Market in Quezon City, Philippines. Phil. J. Health Res. Dev. 2016, 20, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Joshua, A.; Moses, A.; Ezekiel Olugbenga, A. A Survey of Antimicrobial Agents’ Usage in Poultry Farms and Antibiotic Resistance in Escherichia coli and Staphylococci Isolates from the Poultry in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. J. Infect. Dis. Epidemiol. 2018, 4, 047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Momtaz, H. Molecular Typing, Phenotypic and Genotypic Assessment of Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Factors Amongst the Staphylococcus aureus Bacteria Isolated from Raw Chicken Meat. Mol. Genet. Microbiol. Virol. 2022, 37, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Joy, M.H.; Sarker, A. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern of Staphylococcus aureus from Frozen Chicken Meat. Int. J. Biosci. 2024, 25, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, V.; Madoroba, E.; Magwedere, K.; Fosgate, G.; Kuonza, L. Prevalence and Risk Factors Contributing to Antibiotic-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Poultry Meat Products in South Africa, 2015–2016. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2019, 90, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, O.; Tarabees, R.; Badr, H.; Hassan, H.; Hussien, A. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from Poultry Meat Products Regarding mecA Gene, Antibiotic Sensitivity, and Biofilm Formation. Alex. J. Veter Sci. 2022, 75, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarmadi, A.A.M.; Prajitno, S.; Widodo, A.D.W. Antibiotic Resistance in Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus from Retail Chicken Meat in Surabaya, Indonesia. Biomol. Health Sci. J. 2020, 3, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako, D.G.; Somboro, A.M.; Abia, A.L.K.; Molechan, C.; Perrett, K.; Bester, L.A.; Essack, S.Y. Antibiotic Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus from Poultry and Poultry Products in uMgungundlovu District, South Africa, Using the “Farm to Fork” Approach. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamendjari, S.; Bouzebda Afri, F.; Chaib, L.; Aggad, H.; Bouzebda, Z. Combination of Gembili Tuber and Lactobacillus plantarum on the Performance, Carcass, Hematological Parameters, and Gut Microflora of Broiler Chickens. Adv. Anim. Veter Sci. 2022, 11, 189–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachemi, A.; Zenia, S.; Denia, M.F.; Guessoum, M.; Hachemi, M.M.; Ait-Oudhia, K. Epidemiological Study of Sausage in Algeria: Prevalence, Quality Assessment, and Antibiotic Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus Isolates and the Risk Factors Associated with Consumer Habits Affecting Foodborne Poisoning. Vet. World 2019, 12, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounar-Kechih, S.; Taha Hamdi, M.; Aggad, H.; Meguenni, N.; Cantekin, Z. Carriage Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Poultry and Cattle in Northern Algeria. Vet. Med. Int. 2018, 2018, 4636121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouaib, N.E.H.; Benhamed, N.; Kaas, R.S.; Otani, S.; Benyettou, I.; Bekki, A.; Hansen, E.B. Analysis of genetic signatures of virulence and resistance in foodborne Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Algeria. LWT 2024, 209, 116754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermana, N.S.P.; Safika; Indrawati, A.; Wibawan, I.W.T.; Pasaribu, F.H. Identification of Antibiotic Resistance Pattern and Antibiotic Resistance Gene of Staphylococcus aureus from Broiler Chicken Farm in Sukabumi and Cianjur Regency, West Java Province, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1174, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogofure, A.G.; Igbinosa, E.O. Effects of Rinsing on Staphylococcus aureus Load in Frozen Meats and Fish Obtained from Open Markets in Benin City, Nigeria. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 2021, 22, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekana, A.; Green, E. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Meat Carcasses and Bovine Milk in Abattoirs and Dairy Farms of the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achek, R.; Hotzel, H.; Cantekin, Z.; Nabi, I.; Hamdi, T.M.; Neubauer, H.; El-Adawy, H. Emerging of Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococci Isolated from Clinical and Food Samples in Algeria. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghabbour, R.; Awad, A.; Younis, G. Genetic Characterization and Antimicrobial-Resistant Profiles of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Different Food Sources. Biocontrol. Sci. 2022, 27, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.Á.A.D.; Almeida, A.C.D.; Xavier, M.A.D.S.; Silva, L.M.V.D.; Sousa, C.N.; Sanglard, D.A.; Xavier, A.R.E.D.O. Characterization and Molecular Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus Strains Resistant to Beta-Lactams Isolated from the Milk of Cows Diagnosed with Subclinical Mastitis. Vet. World 2019, 12, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.E.; Christensen, H.; Skov, R.L.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Agerso, Y. Diversity of the Tetracycline Resistance Gene Tet(M) and Identification of Tn916- and Tn5801-like (Tn6014) Transposons in Staphylococcus aureus from Humans and Animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 64, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier-Lachance, J.; Arsenault, J.; Usongo, V.; Parent, É.; Labrie, J.; Jacques, M.; Malouin, F.; Archambault, M. Prevalence and Characteristics of Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) Isolated from Chicken Meat in the Province of Quebec, Canada. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbo, M.C.; Ezeonu, I.M.; Onodagu, B.O.; Ezeh, C.C.; Ozioko, C.A.; Emencheta, S.C. Antimicrobial Resistance Markers Distribution in Staphylococcus aureus from Nsukka, Nigeria. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Xu, G.; Li, D.; Bai, B.; Wang, H.; Cheng, H.; Zheng, J.; Sun, X.; Lin, Z.; Deng, Q.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus with an Erm-Mediated Constitutive Macrolide-Lincosamide-Streptogramin B Resistance Phenotype Has Reduced Susceptibility to the New Ketolide, Solithromycin. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laceb, Z.M.; Diene, S.M.; Lalaoui, R.; Kihal, M.; Chergui, F.H.; Rolain, J.-M.; Hadjadj, L. Genetic Diversity and Virulence Profile of Methicillin and Inducible Clindamycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates in Western Algeria. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Omidi, A.H.; Afkhami, H.; Sabati, H.; Mohsenzadeh, A.; Soleymani, A.; Zonobian, M.A.; Ghanbarnejad, N.; Mohammadi, M.R. Frequency of Aac(6)-Le-Aph(2) Gene and Resistance to Aminoglycoside Antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates. Cell. Mol. Biomed. Rep. 2024, 4, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdiyoun, S.M.; Kazemian, H.; Ahanjan, M.; Houri, H.; Goudarzi, M. Frequency of Aminoglycoside-Resistance Genes in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Isolates from Hospitalized Patients. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2016, 9, e35052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshebrawy, H.A.; Kasem, N.G.; Sallam, K.I. Methicillin- and Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Chicken Carcasses, Ready-to-Eat Chicken Meat Sandwiches, and Buffalo Milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 427, 110968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, H.J.; Jebur, M.H.; Ali, J.A.; Ali Jeddoa, Z.M. Molecular Detection of Vancomycin Resistance Genes in Staph aureus Isolates from Different Clinical Specimens. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 12, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizlisoy, H.; Ertas Onmaz, N.; Karadal, F.; Al, S.; Yildirim, Y.; Gonulalan, Z.; Kilic, H. Hayvansal Gıdalardan İzole Edilen Staphylococcus aureus’ların Antibiyotik Dirençlilik Gen Profilleri. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2018, 24, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballah, F.M.; Islam, M.d.S.; Rana, M.d.L.; Ferdous, F.B.; Ahmed, R.; Pramanik, P.K. Phenotypic and Genotypic Detection of Biofilm-Forming Staphylococcus aureus from Different Food Sources in Bangladesh. Biology 2022, 11, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, S.J.; Kannan, P.; Savariraj, W.R.; Ayyasamy, E.; Tuticorin Maragatham Alagesan, S.K.; Ravindran, N.B.; Sundaram, S.; Mohanadasse, N.Q.; Kang, Q.; Cull, C.A.; et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from milk samples for their virulence, biofilm, and antimicrobial resistance. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achek, R.; Hotzel, H.; Nabi, I.; Kechida, S.; Mami, D.; Didouh, N. Phenotypic and Molecular Detection of Biofilm Formation in Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Different Sources in Algeria. Pathogens 2020, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).