Abstract

As one of the most serious and widespread neurological disorders, epilepsy affects nearly 70 million people worldwide. In the development of this disease, significant alterations of gut microbiotas are often observed in the patients. During the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy, which accounts for ~20–30% of cases, a ketogenic diet (KD), a diet containing high fat, adequate protein, and low carbohydrate, has been widely used and showed promising therapeutic effects. The underlying mechanisms of the neuroprotective effects of a KD have been suggested in recent studies to be connected to the gut microbiota, the composition of which is dramatically influenced by this treatment. In this review, we summarize the recent advances of the relationship between a KD, gut microbiota, and epilepsy, with an emphasis on the gut bacterial changes under KD treatment, hoping to delineate the gut microbiota as a potential therapeutic target in epilepsy.

1. Introduction

The human gut microbiota has received immense attention from the fields of microbiology, genetics, and basic and clinical medicine in recent years, and it has been found to play important roles in the immune, endocrine, neurological, and other systems of the human body [1]. The bidirectional signaling network linking the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system (CNS), known as the gut–brain axis, has been extensively studied for its critical relationship to health and disease [2]. Recently, with the in-depth study of the gut microbiota, the notion has been extended to including the microbiota, termed the “microbiota–gut–brain axis”. The concept associates gut microbiota with various CNS disorders, like epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease [3], Parkinson’s disease [4], autism spectrum disorder [5], and multiple psychiatric disorders like stress, anxiety, and depression [6]. As the most serious and widespread neurological disorder, epilepsy usually starts in infancy and lasts for an individual’s lifetime. Nearly 70 million people worldwide are affected by it, and approximately~20–30% of these patients are resistant to routine antiepileptic drugs [7]. According to the ad hoc Task Force of the International League Against Epilepsy, those who fail to achieve lasting freedom from seizures after adequate trials with monotherapy or multi-drug combinations of first-line antiepileptic drugs are diagnosed as having drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) [8]. Interestingly, patients with epilepsy (PWEs) often suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms, and patients with inflammatory bowel disease are more susceptible to epilepsy [9]. A considerable number of studies on gut microbiota and epilepsy have been published, many of which emphasized the significant impacts of dietary intervention. Among these interventions, a ketogenic diet (KD), a high-fat, low-carbohydrate, and adequate-protein diet established early in the 1920s by Wilder [10], has proven efficacy for refractory epilepsy [5,11]. Dramatic compositional changes in gut microbiota in refractory epilepsy patients and the therapeutic effects of KD on epilepsy via regulating gut microecology have been demonstrated in many studies [12,13,14]. However, the gut microbiota’s mechanistic role in the KD’s therapeutic effects to intractable epilepsy has not been fully illustrated. In this review, recent advances regarding the associations of gut microbiota, DRE, and a KD are discussed.

2. Gut Microbiota and DRE

2.1. Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis

The human gut microbiota is a complex microbial ecosystem that maintains immune, endocrine, metabolic, and neurological homeostasis [15]. It is estimated that over 100 trillion microorganisms, representing more than 1000 species, inhabit the adult gastrointestinal tract, with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes constituting more than 90% of the microbial population [16,17,18]. This composition is shaped by numerous internal and external factors, such as diet, medication, age, and lifestyle [19,20]. Among these, diet exerts the most profound and immediate influence, capable of modifying microbial diversity and metabolic functions within days.

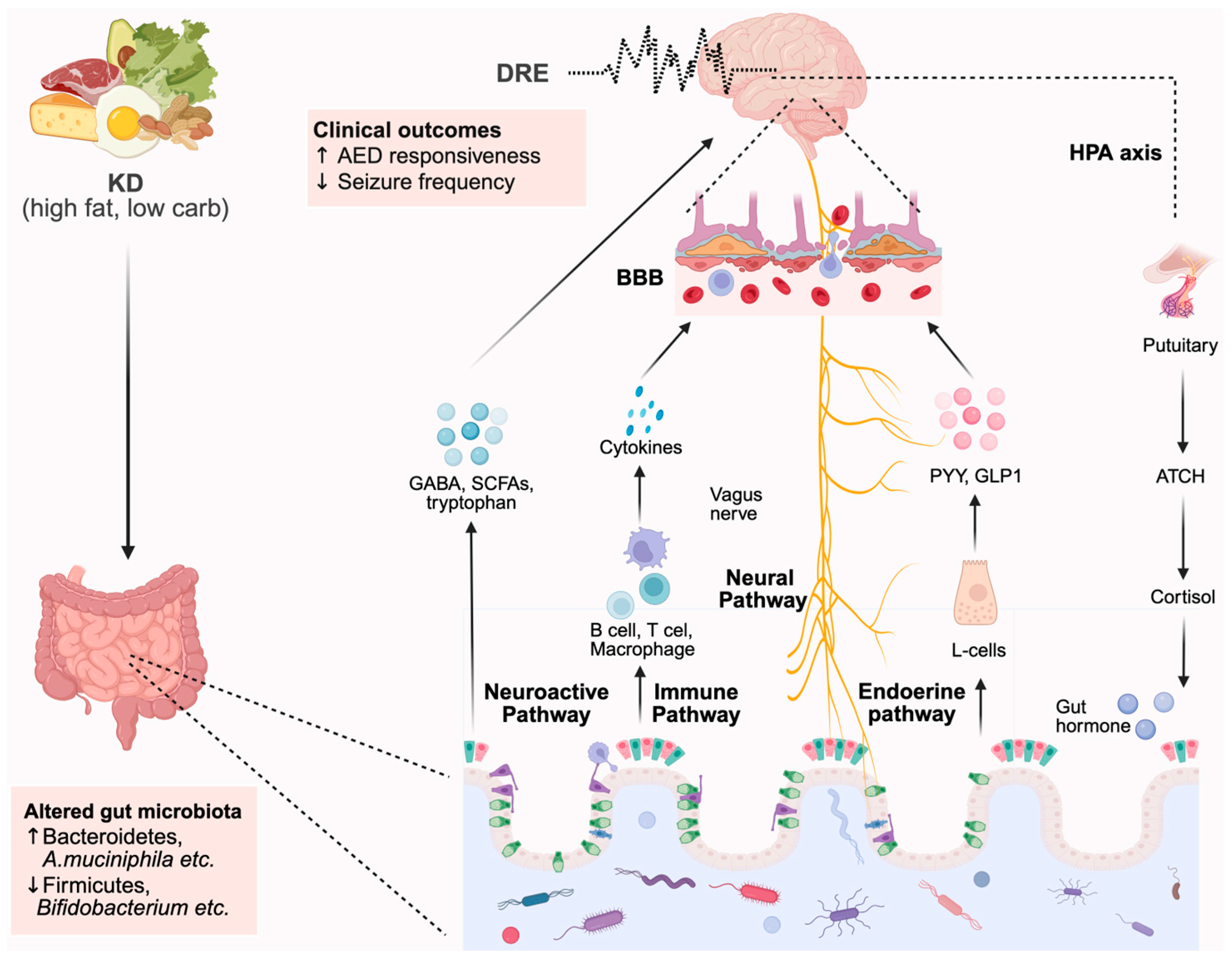

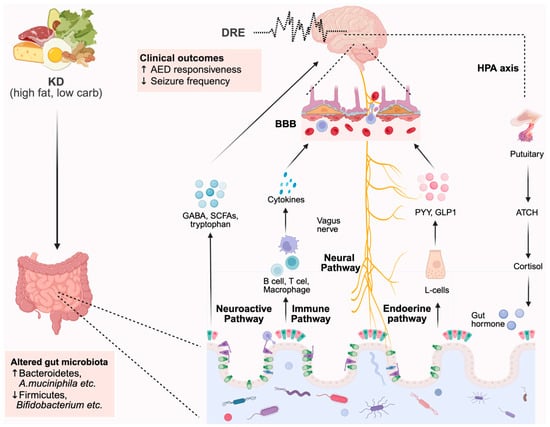

The microbiota–gut–brain axis describes the bidirectional communication network connecting the intestinal microbiota and the central nervous system (CNS) [21,22,23]. This interaction occurs through multiple pathways: (1) the neural (vagus nerve) pathway; (2) the neuroendocrine–hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis; (3) the immune system; (4) microbially derived neurotransmitters and neuromodulators; and (5) the intestinal mucosal and blood–brain barriers (BBBs) [24,25]. Through these mechanisms, the brain modulates gut motility, secretion, and permeability, while the microbiota regulates neurotransmitter synthesis, neuroinflammation, and neuronal excitability [26,27].

Microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acids, and tryptophan derivatives play key roles in maintaining BBB integrity, microglial activation, and the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission, particularly glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [27,28]. Disruption of this axis, termed dysbiosis, can result in decreased SCFA production, impaired immune signaling, and altered neurotransmitter metabolism, contributing to the pathogenesis of several neurological disorders, including epilepsy [29,30].

2.2. Evidence of Microbiota Dysbiosis in DRE Cases

Vast evidence from animals and human studies has shown that the gut microbiota plays a critical role in brain development and functioning [4,16,29,30]. With the wide use of 16S rRNA sequencing technology, the latest population-based studies revealed not only gut microbiota differences between PWEs and healthy controls (HCs) but also gut bacterial composition variations between individuals with DRE and drug-sensitive epilepsy (DSE, Table 1). These differences between healthy controls and individuals with epilepsy have suggested the possible roles of gut microbes in the pathogenesis of epilepsy. Here, we elaborate on the relationship between the gut microbiota and epilepsy in clinical cases and discuss the modulation of gut microbiota in epilepsy patients.

One of these studies assessed the gut microbe’s diversity in a Turkish cohort with idiopathic focal epilepsy (N = 30) and a HC group (N = 10) by 16s rRNA sequencing in 2018 [31]. Safak et al. [32] analyzed seven main phyla from all samples and unveiled the difference in microbiota at the phylum and species level in the HC group and PWEs. Proteobacteria were found to be higher in PWEs (25.4%) than in HCs (1.5%). Fusobacteria were detected in 10.6% of the PWEs but not in the HCs, while Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria were found to be higher in the HCs than in PWEs. These significant differences in gut microbiota composition suggest that bacterial dysbiosis may play a key role in the etiology of epilepsy. Of note, there was a potentially confounding factor in Safak’s study: the absence of family controls to eliminate the possible effects caused by baseline dietary differences. Another study by Lindefeldt et al. [33] eliminated this confounder by analyzing fecal samples from 12 Swedish children with DRE (aged 2~11 years) and 11 healthy parents, who served as controls, using shotgun metagenomic sequencing. In the patient group, fecal microbiota diversity showed a slight decrease, and the microbiota of children with DRE presented a higher variability. In addition, the relative abundances of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria decreased, while both Firmicutes and Actinobacteria increased in children with DRE. The authors also noted that the expression of genes involved in the acetyl-CoA pathway, such as acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase and β-hydroxybutyric-CoA dehydrogenase, were reduced in the patients’ microbiota compared with those in the HCs. Subsequently, following the preliminary analysis of gut microbiota differences between DRE patients and controls, Lindefeldt et al. [33] proceeded to conduct a KD management intervention, which will be discussed in the following section.

Gut microbiota analysis can also be used to determine the difference between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant individuals. The first study of this kind was published in 2018 [34], where Peng and colleagues performed high-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing of fecal samples of the participants. After comparing the microbial compositions of DRE patients (N = 42), DSE patients (N = 49), and HCs (N = 65, from the same families as the patients), they found that the DRE group had significantly increased α-diversity compared with the HCs. They also observed that DSE patients and HCs normally had more Bacteroidetes than Firmicutes, while this ratio was reversed in DRE patients. The abundances of specific bacterial genera also increased abnormally [34], including Clostridium XVIII, Akkermansia, Atopobium, Holdemania, Dorea, Delftia, Coprobacillus, Paraprevotella, and Fusobacterium. In addition, the levels of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria were elevated in individuals with fewer seizures (≤4 per year). Meanwhile, the DSE patients displayed comparable community richness and evenness to those of the HCs [34]. These results suggested that dysbiosis might be involved in the pathogenesis of DRE, and the restoration of gut microbiota might be a new method of treatment.

In line with the principle of comparing drug responders and non-responders, Gong and colleagues designed an analysis to display these changes [35]. They performed two independent cross-sectional analyses, including an exploration and a validation cohort, aiming to use the gut microbiota as a biomarker for epilepsy. The exploration cohort contained 55 PWEs and 46 HCs, who were healthy spouses of the patients, and another cohort contained 13 PWEs and 10 HCs. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were similar to the above-mentioned study by Peng et al. [34]. The alpha diversity indexes of the specimens from PWEs were much lower than those from the HCs (p < 0.05). Microbiota alterations in PWEs included increases in Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobia and a decrease in Proteobacteria at the phylum level, and rises in Prevotella_9, Blautia, Bifidobacterium, and others at the genus level [35]. In the subsequent sample analysis, 30 DRE patients were compared to 25 DSE patients in the exploration cohort, and the authors found that DRE patients showed significant enrichment in Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, and Nitrospirae, as well as the genera Blautia, Bifidobacterium, Subdoligranulum, Dialister, and Anaerostipes [35].

Table 1.

Representative studies on gut microbiota and epilepsy.

Table 1.

Representative studies on gut microbiota and epilepsy.

| Year | Population (N, Age) | Methodology | Findings | Country | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | DRE (12, NA) HCs (12, NA) | Fecal samples 16S rRNA sequencing | ↑ Akkermansia muciniphila, ↑ Parabacteroides gordonii | America | Lum et al. [36] |

| 2021 | DREPs (20, 41 ± 13.6 years) DSEPs (20, 44 ± 17.2 years) | Fecal samples 16S rRNA sequencing | ↔ α-diversity, β-diversity ↑ Firmicutes, Bifidobacterium, Shigella, Veillonellales, Klebsiella, Streptococcus ↓ Bacteroidetes, Ruminococcus_g2, Bifidobacterium | Korea | Lee et al. [37] |

| 2020 | Exploration cohort: PWEs (55, 15∼50 years), HCs (46, NA)/ DRE (30, NA), DSE (25, NA) Validation cohort: PWEs (13, NA), HCs (10, NA) | Fecal samples 16S rRNA sequencing | ↓ α-diversity ↑ Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Nitrospirae, Blautia, Bifidobacterium, Subdoligranulum, Dialister, Anaerostipes ↓ Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria | China | Gong et al. [35] |

| 2020 | IEPs (8, 1.16–6.92 years), HCs (32, 1.16–6.92 years) | Fecal samples 16S rRNA sequencing | ↓ α-diversity ↑ Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia ↓Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria | Korea | Lee et al. [38] |

| 2020 | IEPs (30, 41.3 ± 12.2 years), HCs (10, 31.7 ± 6.8 years) | Fecal samples 16S rRNA sequencing | α-diversity NA ↓ Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Euryarchaeota ↑ Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Spirochaetes | Turkey | Birol Şafak et al. [32] |

| 2019 | DREPs (20, 2–17 years), HCs (11, NA) | Fecal samples Metagenomic sequencing | ↔ α-diversity ↑ Firmicute, Actinobacteria ↓Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria | Sweden | Lindefeldt et al. [33] |

| 2018 | DREPs (42, 28.4 ± 12.4 years), DSEPs (49, 25.1 ± 14.6 years), HCs (65, 29.4 ± 13.8 years). | Fecal samples 16S rRNA sequencing | ↑ α-diversity ↑ Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobiota, Clostridium XVIII, Akkermansia, Atopobium, Holdemania, Dorea, Delftia, Coprobacillus, Paraprevotella, Fusobacterium, etc. ↓ Bacteroidetes | China | Peng et al. [34] |

Abbreviations: PWEs, patients with epilepsy; IEPs, idiopathic/intractable epilepsy patients; DREPs, drug-resistant epilepsy patients; DSEPs, drug-sensitive epilepsy patients; HCs, healthy controls; NA, not available. ↑ Increase in abundance. ↓ Decrease in abundance. ↔ No significant changes in abundances.

Considering the inconsistent results of the published studies regarding the gut microbiota as a diagnostic biomarker of DRE that had been published at that time, Lee et al. [38] analyzed fecal samples from a population of 8 Korean children aged 1~7 years old with intractable epilepsy and 32 age-matched HCs. Using the 16S rRNA gene sequencing approach, they found that α-diversity was higher in epilepsy patients, and β-diversity showed a clear difference in bacterial composition between the two groups. In the epilepsy group, the amount of Bacteroidetes was lower and the amount of Actinobacteria was higher than in the healthy group. Species biomarkers for intractable epilepsy included the Enterococcus faecium group, Bifidobacterium longum group, and Eggerthella lenta. By analyzing those data, the authors confirmed that patients with intractable epilepsy did, indeed, have gut bacterial dysbiosis. The following year, Lee and colleagues [37] conducted another exploratory trial based on adult patients at their clinic. They prospectively included 44 adult epilepsy patients and classified them into drug-responsive and drug-resistant groups but found no differences in α or β diversity between the two groups. While the abundances of Firmicutes, Bifidobacterium, Shigella, Veillonellales, Klebsiella, and Streptococcus increased in DRE patients, the relative abundances of Bacteroides, Ruminococcus_g2, and Bifidobacterium were augmented in DSE patients. The significant difference in the composition of gut microbiota among patients with DRE and DSE supported the conclusions in Peng and Gong’s research.

Most recently, Lum et al. [36] conducted a dual human–mouse study in a U.S. pediatric cohort to investigate microbial dysbiosis in epilepsy. The authors observed that children with DRE exhibited lower microbial diversity but enrichment of Akkermansia muciniphila and Parabacteroides gordonii. Importantly, fecal microbiota transplantation from DRE patients into germ-free mice significantly increased seizure thresholds and reduced seizure frequency, confirming that the gut microbiota directly modulates seizure susceptibility. These findings provided the first causal evidence in humans and mice linking microbiota alterations to seizure control.

Taken together, these six clinical studies assessed the diversity and composition of gut microbiota in PWEs and suggested the existence of microbial dysbiosis in DRE patients, indicating the potential value of using the gut microbiota as a sensitive biomarker for diagnosis and a treatment target to enhance control of seizures. Notably, most studies showed that α-diversity in the HC group was higher than that in the DRE group [32,33,35,37,38]. However, Peng’s study demonstrated an opposite trend, with increased α-diversity in the DRE group [34], which indicated that the alteration of microbiota in epilepsy patients might not always be consistent. Considering the influence of study design, age, diet, living environment, and other impacts on gut microbes, a larger-sample analysis based on reasonable control variables is still needed.

3. Links Between KD and Gut Microbiota in DRE

3.1. Gut Microbiota and KD

Unlike the host genome, the gut microbiota exhibits a considerable plasticity and can be readily influenced by a variety of stimuli, including diet [31], medication [39], stress [40], infection [41], and lifestyle factors [42]. Among these, diet represents the dominant determinant shaping the gut microbiota’s composition and metabolic activity. Numerous studies have shown that daily dietary habits are pivotal in defining microbial diversity across different health states and life stages [31]. In line with Hippocrates’ ancient notion that “food is medicine,” modern evidence confirms that diet-induced changes in microbial ecology can profoundly affect disease susceptibility, either by triggering dysbiosis or restoring microbial balance [43].

Dietary composition primarily consists of carbohydrates, fiber, proteins, and fats, each exerting distinct influences on the gut microbial community [43]. The impact of different types of diet on gut microbiota profiles and the pathogenesis of illness related to this have been studied extensively [44]. For instance, the Western diet, providing 40–55% of calories from fats [45], is typically high in saturated fats and refined sugars. Such diets have been consistently associated with inflammation, impaired intestinal barrier function, and reduced production of SCFAs [46,47]. On the other hand, microbiota-accessible carbohydrates (MACs)—abundant in dietary fiber—play essential roles in maintaining microbial diversity, supporting SCFA production, and promoting gut–brain axis homeostasis [48,49,50]. MAC-deficient diets, however, sometimes exacerbate inflammatory diseases such as allergies, infections, and autoimmunity [46,51]. Another example is the Mediterranean diet, which is rich in omega-3 fatty acids and polyphenols, increases anti-inflammatory bacteria, and is linked to reduced obesity, cancer, and chronic inflammation [52,53]. Dietary protein also critically influences microbial metabolism, as it provides nitrogen, which is essential for bacterial growth and the synthesis of SCFAs [44,54]. However, excessive protein intake may increase harmful fecal metabolites such as hydrogen sulfide, trimethylamine, and phenols, contributing to inflammatory bowel disease and cancer [55].

Building on this evidence, the KD—a high-fat, low-carbohydrate regimen—represents a well-defined nutritional model that profoundly alters the gut microbiota’s structure and function. A classic KD typically follows a 3:1 or 4:1 ratio, meaning that 80–90% of total energy is derived from fats, while only 10–20% comes from carbohydrates and proteins [56]. Although excessive fat intake has been known to have adverse effects [45,47], modern KD protocols have been refined for improved safety and compliance. Four primary KD variants are commonly employed in epilepsy therapy, as summarized in Table 2: the classic KD, medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) diet, modified Atkins diet, and low-glycemic-index therapy [57].

Table 2.

Compositions of the four types of KD.

Originally introduced in the 1920s for treating refractory epilepsy [10], the KD has since been extended to other neurological and metabolic disorders, including migraine [58], glaucoma [56], Alzheimer’s disease [59], obesity [60], cancer [44], and respiratory disorders [61]. Although its clinical efficacy in reducing seizures is well established, the precise mechanisms underlying KD’s antiepileptic effects remain incompletely understood. Current evidence suggests that increased ketone body utilization and polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism play crucial roles [57,62], potentially involving regulation of brain energy metabolism [63], ion-channel activity [64], neurotransmitter synthesis [65], epigenetic modification [66], and gut microbiota modulation [67].

A KD markedly decreases microbial diversity due to its extremely low carbohydrate content, resulting in reduced fiber-degrading bacteria [68]. The microbial community typically shifts toward increased Bacteroides and Prevotella populations, with an approximately 50% reduction in Escherichia coli levels [14]. In a mouse model of refractory epilepsy induced by 6 Hz stimulation, both germ-free and antibiotic-treated mice failed to achieve seizure protection under a KD, whereas fecal microbiota transplantation from KD-treated donors restored the antiseizure effect [67,69]. These studies provide compelling evidence that gut microbiota are essential mediators of KD efficacy.

Further human KD intervention studies have identified responder- and non-responder-specific microbial signatures [70]. Differences were observed at the phylum, family, and genus levels, as well as in the production of microbial metabolites. Such findings suggest the presence of ketone-sensitive microbiota within the gastrointestinal tract that are critical for seizure control [69,71]. These “keto microbiota,” along with their metabolites, can synthesize inhibitory neurotransmitters, such as GABA, by regulating metabolic precursors [72]. Together, these observations indicate that KD exerts its antiepileptic effects through a microbiota–metabolite–neurotransmitter regulatory pathway, modulating neuronal excitability and seizure susceptibility [69].

3.2. KD Intervention Studies and Microbiota-Mediated Mechanisms

As discussed above, clinical analyses have demonstrated distinct alterations in the gut microbiota of patients with DRE. With growing interest in the microbiota–gut–brain axis, multiple studies have investigated how a KD reshapes gut microbial composition and how these changes may contribute to seizure control.

A landmark study by Olson et al. [67] first established the causal link between the KD and seizure protection mediated by gut microbiota. Using two mouse models of 6 Hz induced refractory epilepsy, they found that antibiotic-treated KD-fed mice exhibited increased seizure susceptibility due to microbiota depletion. Remarkably, recolonization with normal gut microbiota restored seizure protection. Feding with a KD reduced microbial diversity but markedly increased the relative abundance of A. muciniphila. Co-colonization of A. muciniphila and Parabacteroides prevented seizures in germ-free mice, whereas single-species colonization failed to do so. Subsequent analyses revealed an elevated hippocampal GABA/glutamate ratio in KD-fed mice, suggesting a mechanistic link between microbial metabolism and neurotransmitter modulation. This pivotal study provided the first direct evidence that gut microbiota are required for the antiseizure effects of KD and that specific bacterial interactions regulate peripheral metabolites influencing hippocampal neurotransmission [69].

Subsequent human studies corroborated these findings. Xie et al. [14] analyzed fecal microbiota from 14 children with refractory epilepsy and 30 healthy controls using 16S rRNA sequencing. After one week of KD treatment, Bacteroidetes increased, whereas overall richness and Proteobacteria declined. At the genus level, Cronobacter decreased, while Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Prevotella increased. Since Bacteroides are involved in lipid metabolism and cytokine regulation (IL-6, IL-17) [73], their increased abundance may reflect enhanced anti-inflammatory potential associated with seizure reduction [74]. These results indicated that a KD could alleviate seizure symptoms by reshaping gut microbiota composition in pediatric patients [14].

In a prospective trial of 20 children with intractable epilepsy, Zhang et al. [70] applied a 4:1 KD for six months. Half of the participants achieved ≥50% seizure reduction. Responders displayed lower alpha diversity and a significant shift from Firmicutes toward Bacteroidetes, along with enrichment of Alistipes, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Rikenellaceae. These taxa differences correlated with treatment efficacy, suggesting that specific bacterial signatures could serve as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for DRE.

Similarly, Lindefeldt et al. [33] performed shotgun metagenomic sequencing on fecal samples from 12 children with DRE before and three months after KD treatment. A KD did not change alpha diversity but significantly altered microbial species and metabolic pathways. Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium rectale, and Dialister decreased, while Escherichia coli increased markedly. Functional profiling revealed 29 altered SEED subsystems, including decreases in 7 carbohydrate metabolism pathways, indicating a major metabolic reprogramming of gut microbiota. These findings highlight Bifidobacteria and E. coli as key contributors to KD-induced metabolic remodeling.

Further insights were provided by Gong et al. [75], who conducted a cross-sectional study involving 12 children with DRE and 12 healthy controls. After six months of KD therapy, fecal SCFA concentrations increased and correlated positively with beneficial microbial taxa. Specifically, Actinobacteria, Bacteroides, Blautia, Anaerostipes, and Subdoligranulum were enriched, whereas potentially pro-convulsive genera declined. These results demonstrate that KD can modulate both microbial composition and metabolite profiles, supporting its capacity to restore gut–brain axis homeostasis in epilepsy.

In addition to these earlier studies, Li et al. [76] provided further mechanistic insights using a rat model of epilepsy treated with a 3:1 ratio KD. Combining 16S rRNA sequencing with metabolomic profiling, the authors revealed increased abundance of Lactobacillus and Akkermansia and decreased levels of Bacteroides following KD administration. These microbial shifts were accompanied by elevated concentrations of SCFAs, including butyrate and propionate, and improved mitochondrial function and oxidative stress parameters. This study highlighted the potential role of SCFA-producing bacteria and improved redox homeostasis as key mediators of the KD’s antiseizure effects.

Building upon these findings, Özcan et al. [77] investigated how dietary fiber content modulates the efficacy of KD in both clinical and experimental models. They compared standard and high-fiber KD formulations and found that the inclusion of microbiota-accessible carbohydrates enriched Akkermansia, Roseburia, and Bacteroides, taxa that are known for SCFA and anti-inflammatory metabolite production. Mice and human subjects receiving a high-fiber KD exhibited greater seizure protection, reduced neuroinflammatory markers, and enhanced SCFA concentrations. These results demonstrated that gut microbiota-derived metabolites, particularly SCFAs, contribute to the neuroprotective effects of KD and that dietary fiber acts as a crucial modulator of KD efficacy.

Collectively, these studies provide convergent evidence that the ketogenic diet (KD) reshapes gut microbiota diversity and functionality, thereby contributing to seizure control. The key methodologies, inferences, and major findings are summarized in Table 3. Despite substantial progress, the precise mechanisms linking microbial alterations to seizure modulation remain incompletely understood. Proposed mechanisms include regulation of cerebral energy metabolism; modulation of neurotransmitters such as GABA, glutamate, and aspartate; and effects on neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission [57].

Table 3.

Gut microbiota alterations after KD in DRE.

The integrated mechanistic relationships between specific gut microbes, their metabolites, and seizure modulation under a KD are summarized in Table 4. Taken together, these findings indicate that a KD promotes the enrichment of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)- and bile acid-producing taxa (Akkermansia, Parabacteroides, Eubacterium), while reducing saccharolytic bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. These microbial and metabolic shifts contribute to strengthened blood–brain barrier (BBB) integrity, reduced neuroinflammation, and elevated seizure thresholds [36,67,76,77,78,79,80].

Table 4.

Mechanistic links between specific gut microbes or metabolites and seizure modulation in ketogenic diet.

Future research should aim to elucidate how specific bacterial taxa and their metabolites influence neuronal membrane potential and neurotransmitter balance. A better understanding of these microbiota–metabolite–neurotransmitter pathways will refine mechanistic models of the KD’s efficacy and facilitate the development of microbiota-targeted interventions for refractory epilepsy.

4. Conclusions

Over the past decade, gradually emerging evidence has supported a crucial connection between the microbiota–gut–brain axis and epilepsy. Gut microbes appear to be key modulators of central nervous system signaling, particularly in DRE treated with the KD. Both animal and human studies suggest that the KD’s antiepileptic effects may depend, at least in part, on microbiota-mediated mechanisms. In this review, we summarize recent murine experimental data and clinical evidence to explore the association between gut microbiota, the KD, and DRE (as schematically summarized in Figure 1). Based on these findings, it is reasonable to speculate that gut microbiota dysbiosis may be a strong factor in both the development and severity of epilepsy. Notably, our recent metagenomic and bioinformatic analyses revealed that the abundance of certain bacteria, such as A. muciniphila and Parabacteroides gordonii—previously identified as antiepileptic species by Olson et al. [67]—increased dramatically following KD treatment, consistent with their demonstrated capacity for lipid utilization in vitro [81]. However, for other bacteria, abundance and growth rates were not correlated, suggesting that KD-induced changes in microbial composition may also be driven by non-nutritional factors.

Figure 1.

Integrated model illustrating microbiota–metabolite–neural pathways linking ketogenic diet to seizure modulation.

These findings deepen our understanding of how the KD reshapes the gut ecosystem to exert its therapeutic effects. Nonetheless, several critical questions remain unresolved, including the multifaceted mechanisms by which microbial metabolites influence seizure susceptibility and how microbiota can be leveraged as therapeutic targets. To address these gaps, future studies should adopt multi-omics strategies, integrating metagenomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics, to more precisely identify key microbial taxa, metabolic pathways, and bioactive metabolites associated with seizure control.

Importantly, translating these findings into clinical practice will require exploration of microbiota-oriented interventions, such as probiotics, prebiotics, and personalized dietary approaches, as adjunctive strategies to enhance the efficacy of the KD in DRE management. A systems-level understanding of host–microbe interactions will provide new insights into the pathogenesis of epilepsy and the development of microbiome-based precision therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.W., J.W., and Y.W.; resources, W.W., Y.W. and J.W.; data curation, M.T. and W.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, W.W. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by High Technology Research and Development Center, Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2019YFA0801900); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (YG2023QNB22); and Epilepsy Research Fund of China Association Against Epilepsy (CJ-B-2021-21); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 22122702), and Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences (BNLMS202306).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the contents of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KD | ketogenic diet |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| DRE | drug-resistant epilepsy |

| PWEs | patients with epilepsy |

| IEPs | idiopathic/intractable epilepsy patients |

| DREPs | drug-resistant epilepsy patients |

| HCs | healthy controls |

| RE | refractory epilepsy |

References

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: A review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 2019–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, N.; Yamashiro, Y. The Gut-Brain Axis. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 77 (Suppl. 2), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelucci, F.; Cechova, K.; Amlerova, J.; Hort, J. Antibiotics, gut microbiota, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulak, A.; Bonaz, B. Brain-gut-microbiota axis in Parkinson’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 10609–10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, C.; Bomhof, M.R.; Reimer, R.A.; Hittel, D.S.; Rho, J.M.; Shearer, J. Ketogenic diet modifies the gut microbiota in a murine model of autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 2016, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C.A.; Diaz-Arteche, C.; Eliby, D.; Schwartz, O.S.; Simmons, J.G.; Cowan, C.S.M. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression—A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 83, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Trevick, S. The Epidemiology of Global Epilepsy. Neurol. Clin. 2016, 34, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, P.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Berg, A.T.; Brodie, M.J.; Allen Hauser, W.; Mathern, G.; Moshé, S.L.; Perucca, E.; Wiebe, S.; French, J. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: Consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Caro, C.; Leo, A.; Nesci, V.; Ghelardini, C.; di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Striano, P.; Avagliano, C.; Calignano, A.; Mainardi, P.; Constanti, A.; et al. Intestinal inflammation increases convulsant activity and reduces antiepileptic drug efficacy in a mouse model of epilepsy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheless, J.W. History of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Jackson, C.F.; Levy, R.G.; Cooper, P. Ketogenic diet and other dietary treatments for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD001903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddel, S.; Putignani, L.; Del Chierico, F. The Impact of Low-FODMAPs, Gluten-Free, and Ketogenic Diets on Gut Microbiota Modulation in Pathological Conditions. Nutrients 2019, 11, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Rao, Y.; Miao, J.; Lu, X. Intestinal Microbiota as an Alternative Therapeutic Target for Epilepsy. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2016, 2016, 9032809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhou, Q.; Qiu, C.-Z.; Dai, W.-K.; Wang, H.-P.; Li, Y.-H.; Liao, J.-X.; Lu, X.-G.; Lin, S.-F.; Ye, J.-H.; et al. Ketogenic diet poses a significant effect on imbalanced gut microbiota in infants with refractory epilepsy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 6164–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alander, M.; Satokari, R.; Korpela, R.; Saxelin, M.; Vilpponen-Salmela, T.; Mattila-Sandholm, T.; von Wright, A. Persistence of colonization of human colonic mucosa by a probiotic strain, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, after oral consumption. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiola, F.; Ianiro, G.; Franceschi, F.; Fagiuoli, S.; Gasbarrini, G.; Gasbarrini, A. Gut microbiota in autism and mood disorders. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäckhed, F.; Roswall, J.; Peng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Jia, H.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Li, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhong, H.; et al. Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.; Tosh, P.K. A clinician’s primer on the role of the microbiome in human health and disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, S.; Shen, N.; Wu, H.C.; Clemente, J.C. The microbiome in early life: Implications for health outcomes. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.A.; Hennet, T. Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 2959–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, L.H.; Schreiber, H.L., IV; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota-brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Mahony, S.M. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: From bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.M.; Bercik, P. The relationship between intestinal microbiota and the central nervous system in normal gastrointestinal function and disease. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.; Flaminio, Z.; Vardhan, M.; Xu, F.; Li, X.; Devinsky, O.; Saxena, D. Cross talk between drug-resistant epilepsy and the gut microbiome. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Lang, Y.; Shu, H.; Shao, J.; Cui, L. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Epilepsy: A Review on Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 742449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, T.J.W.; Henry-Barron, B.J.; Felton, E.A.; Gutierrez, E.G.; Barnett, J.; Fisher, R.; Lwin, M.; Jan, A.; Vizthum, D.; Kossoff, E.H.; et al. Improving compliance in adults with epilepsy on a modified Atkins diet: A randomized trial. Seizure J. Br. Epilepsy Assoc. 2018, 60, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandwitz, P.; Kim, K.H.; Terekhova, D.; Liu, J.K.; Sharma, A.; Levering, J.; Mcdonald, D.; Dietrich, D.; Ramadhar, T.R.; Lekbua, A.; et al. GABA-modulating bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Wouw, M.; Boehme, M.; Lyte, J.M.; Wiley, N.; Strain, C.; O’Sullivan, O.; Clarke, G.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; et al. Short-chain fatty acids: Microbial metabolites that alleviate stress-induced brain-gut axis alterations. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 4923–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, H.; Ma, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Tang, W.; Tan, Z.; Shi, J.; et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Borre, Y.; O’ Brien, C.; Patterson, E.; El Aidy, S.; Deane, J.; Kennedy, P.J.; Beers, S.; Scott, K.; Moloney, G.; et al. Transferring the blues: Depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 82, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, M.J.; Jeffery, I.B.; Conde, S.; Power, S.E.; O’Connor, E.M.; Cusack, S.; Harris, H.M.B.; Coakley, M.; Lakshminarayanan, B.; O’Sullivan, O.; et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature 2012, 488, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şafak, B.; Altunan, B.; Topçu, B.; Eren Topkaya, A. The gut microbiome in epilepsy. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 139, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindefeldt, M.; Eng, A.; Darban, H.; Bjerkner, A.; Zetterström, C.K.; Allander, T.; Andersson, B.; Borenstein, E.; Dahlin, M.; Prast-Nielsen, S.; et al. The ketogenic diet influences taxonomic and functional composition of the gut microbiota in children with severe epilepsy. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A.; Qiu, X.; Lai, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, X.; He, S.; Duan, J.; Chen, L. Altered composition of the gut microbiome in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2018, 147, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, C.; Lin, J.; Li, A.; Guo, K.; An, D.; Zhou, D.; Hong, Z. Alteration of Gut Microbiota in Patients With Epilepsy and the Potential Index as a Biomarker. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 517797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, G.R.; Ha, S.M.; Olson, C.A.; Blencowe, M.; Paramo, J.; Reyes, B.; Matsumoto, J.H.; Yang, X.; Hsiao, E.Y. Ketogenic diet therapy for pediatric epilepsy is associated with alterations in the human gut microbiome that confer seizure resistance in mice. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, D.-H.; Kim, D.W. A comparison of the gut microbiota among adult patients with drug-responsive and drug-resistant epilepsy: An exploratory study. Epilepsy Res. 2021, 172, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Kim, N.; Shim, J.O.; Kim, G.-H. Gut Bacterial Dysbiosis in Children with Intractable Epilepsy. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, K.; Buerger, M.; Stallmach, A.; Bruns, T. Effects of Antibiotics on Gut Microbiota. Dig. Dis. 2016, 34, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Cao, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wu, Q.; You, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; et al. Chronic stress promotes colitis by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune system response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2960–E2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducarmon, Q.R.; Zwittink, R.D.; Hornung, B.V.H.; Van Schaik, W.; Young, V.B.; Kuijper, E.J. Gut Microbiota and Colonization Resistance against Bacterial Enteric Infection. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019, 83, e00007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Wolters, M.; Weyh, C.; Krüger, K.; Ticinesi, A. The Effects of Lifestyle and Diet on Gut Microbiota Composition, Inflammation and Muscle Performance in Our Aging Society. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, M.S.; Seekatz, A.M.; Koropatkin, N.M.; Kamada, N.; Hickey, C.A.; Wolter, M.; Pudlo, N.A.; Kitamoto, S.; Terrapon, N.; Muller, A.; et al. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell 2016, 167, 1339–1353.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, R.; Pazienza, V. Impact of Different Types of Diet on Gut Microbiota Profiles and Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Medicina 2019, 55, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, X.-J. Effects of a high fat diet on intestinal microbiota and gastrointestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 8905–8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Starving our Microbial Self: The Deleterious Consequences of a Diet Deficient in Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrates. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamar, G.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Pisani, L.P. High-fat or high-sugar diets as trigger inflammation in the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 836–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.; Chase, A.B.; Weihe, C.; Orchanian, S.B.; Riedel, S.F.; Hendrickson, C.L.; Lay, M.; Sewall, J.M.; Martiny, J.B.H.; Whiteson, K. High-Fiber, Whole-Food Dietary Intervention Alters the Human Gut Microbiome but Not Fecal Short-Chain Fatty Acids. mSystems 2021, 6, e00115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, M.; Hao, S.; Lum, J.S.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.-F.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, K. Supplement of microbiota-accessible carbohydrates prevents neuroinflammation and cognitive decline by improving the gut microbiota-brain axis in diet-induced obese mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Smits, S.A.; Tikhonov, M.; Higginbottom, S.K.; Wingreen, N.S.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Diet-induced extinctions in the gut microbiota compound over generations. Nature 2016, 529, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daïen, C.I.; Pinget, G.V.; Tan, J.K.; Macia, L. Detrimental Impact of Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrate-Deprived Diet on Gut and Immune Homeostasis: An Overview. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliannan, K.; Wang, B.; Li, X.-Y.; Bhan, A.K.; Kang, J.X. Omega-3 fatty acids prevent early-life antibiotic exposure-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis and later-life obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigstad, C.S.; Salmonson, C.E.; Iii, J.F.R.; Szurszewski, J.H.; Linden, D.R.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Farrugia, G.; Kashyap, P.C. Gut microbes promote colonic serotonin production through an effect of short-chain fatty acids on enterochromaffin cells. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ju, Z.; Zuo, T. Time for food: The impact of diet on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrition 2018, 51–52, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowska, I.M. Therapeutic Use of the Ketogenic Diet in Refractory Epilepsy: What We Know and What Still Needs to Be Learned. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegar, M.; Afghan, M.; Tarmahi, V.; Behtari, M.; Rahimi Khamaneh, S.; Raeisi, S. Ketogenic diet: Overview, types, and possible anti-seizure mechanisms. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbanti, P.; Fofi, L.; Aurilia, C.; Egeo, G.; Caprio, M. Ketogenic diet in migraine: Rationale, findings and perspectives. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38 (Suppl. 1), 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broom, G.M.; Shaw, I.C.; Rucklidge, J.J. The ketogenic diet as a potential treatment and prevention strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrition 2019, 60, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Barrea, L.; Laudisio, D.; Pugliese, G.; Salzano, C.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. The management of very low-calorie ketogenic diet in obesity outpatient clinic: A practical guide. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangitano, E.; Tozzi, R.; Gandini, O.; Watanabe, M.; Basciani, S.; Mariani, S.; Lenzi, A.; Gnessi, L.; Lubrano, C. Ketogenic Diet as a Preventive and Supportive Care for COVID-19 Patients. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bough, K. Energy metabolism as part of the anticonvulsant mechanism of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bough, K.J.; Wetherington, J.; Hassel, B.; Pare, J.F.; Gawryluk, J.W.; Greene, J.G.; Shaw, R.; Smith, Y.; Geiger, J.D.; Dingledine, R.J.; et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis in the anticonvulsant mechanism of the ketogenic diet. Ann. Neurol. 2006, 60, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellen, G. Ketone bodies, glycolysis, and KATPchannels in the mechanism of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, N.; Betancourt, L.; Hernández, L.; Rada, P. A ketogenic diet modifies glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid and agmatine levels in the hippocampus of rats: A microdialysis study. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 642, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbek, A.; Wojtala, M.; Pirola, L.; Balcerczyk, A. Modulation of Cellular Biochemistry, Epigenetics and Metabolomics by Ketone Bodies. Implications of the Ketogenic Diet in the Physiology of the Organism and Pathological States. Nutrients 2020, 12, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.A.; Vuong, H.E.; Yano, J.M.; Liang, Q.Y.; Nusbaum, D.J.; Hsiao, E.Y. The Gut Microbiota Mediates the Anti-Seizure Effects of the Ketogenic Diet. Cell 2018, 173, 1728–1741.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianchecchi, E.; Fierabracci, A. Recent Advances on Microbiota Involvement in the Pathogenesis of Autoimmunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, T. Gut Microbes May Account for the Anti-Seizure Effects of the Ketogenic Diet. JAMA 2018, 320, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y. Altered gut microbiome composition in children with refractory epilepsy after ketogenic diet. Epilepsy Res. 2018, 145, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, E.; Blackford, R. Gut Microbiota, the Ketogenic Diet and Epilepsy. Pediatr. Neurol. Briefs 2018, 32, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Mulero, A.; Tinahones, A.; Bandera, B.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Macías-González, M.; Tinahones, F.J. Keto microbiota: A powerful contributor to host disease recovery. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2019, 20, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, L.-Y.; Ding, J.; Peng, W.-F.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Fan, W.; Wang, X. Interictal interleukin-17A levels are elevated and correlate with seizure severity of epilepsy patients. Epilepsia 2013, 54, e142–e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.-M.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Cai, Q.; Liu, X.; An, D.; Zhou, D.; Luo, R.; Peng, R.; Hong, Z. Gut flora and metabolism are altered in epilepsy and partially restored after ketogenic diets. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 155, 104899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Yang, L.; Ji, H.; Liu, K.; et al. Ketogenic Diets Alter the Gut Microbiome, Resulting in Decreased Susceptibility to and Cognitive Impairment in Rats with Pilocarpine-Induced Status Epilepticus. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 2726–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, E.; Yu, K.B.; Dinh, L.; Lum, G.R.; Lau, K.; Hsu, J.; Arino, M.; Paramo, J.; Lopez-Romero, A.; Hsiao, E.Y. Dietary fiber content in clinical ketogenic diets modifies the gut microbiome and seizure resistance in mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadi, P.; Farokh, P.; Osouli Meinagh, S.; Izadi-Jorshari, G.; Hajikarimloo, B.; Mohammadi, G.; Parvardeh, S.; Nassiri-Asl, M. The Influence of the Probiotics, Ketogenic Diets, and Gut Microbiota on Epilepsy and Epileptic Models: A Comprehensive Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 14519–14543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, J.; Scantlebury, M.H.; Rho, J.M.; Tompkins, T.A.; Mu, C. Intermittent vs continuous ketogenic diet: Impact on seizures, gut microbiota, and mitochondrial metabolism. Epilepsia 2023, 64, e177–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubareva, O.E.; Dyomina, A.V.; Kovalenko, A.A.; Roginskaya, A.I.; Melik-Kasumov, T.B.; Korneeva, M.A.; Chuprina, A.V.; Zhabinskaya, A.A.; Kolyhan, S.A.; Zakharova, M.V.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum in a Lithium-Pilocarpine Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, L.; Niu, J.; Meng, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Comparative analysis of growth dynamics and relative abundances of gut microbiota influenced by ketogenic diet. Phenomics 2025, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).