Abstract

This study presents a comprehensive thermo-structural and modal analysis of a ball screw assembly. Thermal analysis revealed a maximum temperature of 29.1 °C at the ball nut, corresponding to a total rise of 7.1 °C above ambient. The resulting thermal deformation reached 77.81 μm, while the von Mises stress peaked at 53.9 MPa, both within acceptable limits. Modal simulation of 360 modes showed a sharp increase in frequency with mode number and larger deformation patterns at the higher modes. The first two modes dominate the effective mass with the first 8 modes capturing over 90% of the cumulative effective mass. Overall, the results demonstrate stable thermal performance, limited deformation, low stress, and controlled vibrations, confirming the modeling approach and the suitability of 42CrMo4 steel for high-precision ball screw assemblies.

1. Introduction

Ball screws convert rotary motion into linear motion and are widely used in precision manufacturing. Their accuracy is strongly affected by heat generated during operation [1]. In machining, various heat sources such as bearings, servo motors, cutting zones, and ambient temperature create uneven thermal fields that cause deformation and positioning errors. These thermal effects can account for up to 70% of total machining errors in precision machine tools [2].

As core transmission elements in electromechanical linear actuators, ball screws play a significant role in actuator positioning accuracy, stiffness, and dynamic behavior [3]. Beyond static accuracy, the structural and modal characteristics of the ball screw assembly further shape the actuator’s vibration response and dynamic stability, particularly at higher operating speeds. These thermally induced deformations and positioning deviations directly translate into performance degradation in ball screw-driven actuators [1,2].

The finite element method (FEM) is commonly used to investigate thermal errors in machine tools and electromechanical actuators [4]. Li et al. [5] performed numerical simulations to analyze the heating of individual components within the ball screw system, and they integrated these results with the finite element method to develop models for both the temperature distribution and thermal errors of the ball screw. Xu et al. [6] integrated an enhanced lumped parameter model with the finite element method to evaluate the temperature distribution and thermal deformation in the ball screw feed system. Li et al. [7] developed an exponential model grounded in FEA to forecast temperature changes in the ball screw at various stages and to determine its thermal boundary conditions. Razak et al. [8] applied finite element analysis to examine the distribution of temperature, thermal stress, and strain in a CNC milling machine feed system, while Oyanguren et al. [9] using a 3D thermodynamic FEM model, predicted stress, transient temperature and contact forces of a double-nut ball screw. Shang et al. [10] further refined the simulation of ball screw nut pairs using APDL to model their reciprocating motion and study thermal characteristics. These studies demonstrate that FEM-based modeling is an effective approach for analyzing temperature fields, thermal deformation, and stress behavior in ball screw systems.

Like thermal errors, ball screws are subjected to vibrations where they lead to elastic deformation and can greatly influence positioning accuracy at high speeds [11]. Experimental investigations using operational modal analysis (OMA) were conducted to characterize the dynamic behavior of ball-screw drives, identifying their natural frequencies and damping ratios under real operating conditions. Comparisons with mathematical models revealed deviations caused by modeling assumptions and parameter uncertainties [12]. In addition, both hybrid and lumped-mass dynamic models have been developed to analyze the modal characteristics of ball-screw feed drives, demonstrating that the screw shaft plays a dominant role in determining the system’s eigenfrequencies and vibration modes [13]. Aenlle et al. [14] proposed new formulations for modal parameters that offer physically meaningful definitions of modal mass and mode shape length. These theoretical advancements enhanced the analysis of experimentally identified mode shapes in complex structures, where distributed mass and stiffness significantly influence vibration behavior. Together, these studies provide a comprehensive understanding of ball screw dynamics and offer tools to accurately predict their vibration behavior under practical operating conditions.

Previous research has extensively examined the thermal, structural, and dynamic behavior of ball screw systems, focusing on the effects of frictional heating, vibrations, and geometric parameters. However, most prior works have relied on conventional materials such as high-carbon or case-hardened steels and have generally treated thermal and modal effects separately. To address these limitations, the present study conducts an integrated thermo-structural and modal analysis of a precision ball screw assembly. The analysis incorporates realistic frictional heat generation and convective boundary conditions while employing 42CrMo4 steel, a high-strength alloy rarely applied in ball screw design to assess its suitability for precision motion systems. This combined approach provides a comprehensive understanding of the system’s thermal stability, deformation characteristics, and vibration behavior, offering new insights for optimizing the design and material selection of next-generation ball screw mechanisms.

2. Methodology

This section describes the approach used to study the ball screw assembly. The first subsection covers CAD modeling of the assembly, while the next subsections describe the simulation setup for thermal, structural, and modal analyses.

2.1. CAD Modeling of the Ball Screw

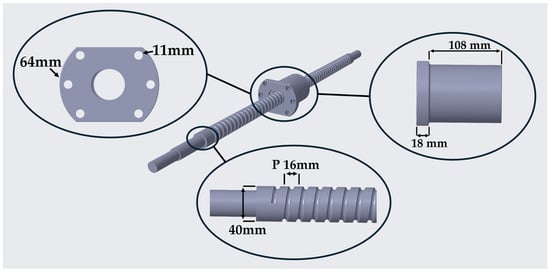

The ball screw was modeled in SolidWorks 2025, the assembly consists of the screw shaft and nut. The ball screw selected for this study has a diameter of 40 mm, a pitch of 16 mm, and a total shaft length of 1127 mm. The design was chosen based on common industrial use in precision motion systems and was developed in accordance with ISO 3408 standards [15]. The ball screw model and some dimensions are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CAD model of the ball screw assembly with key dimensions, where P denotes the screw pitch.

2.2. Simulation Setup and Boundary Conditions

The simulation of the proposed ball screw was performed in Ansys 2025 R1. The ball screw shaft and nut were made from 42CrMo4 steel, a low-alloy chromium-molybdenum steel that complies with the European standard EN 10083-3 [16]. The material was chosen for its favorable combination of high strength and good thermal conductivity, which are critical for the thermo-mechanical analysis of ball screw. The detailed properties and their values are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mechanical and thermal properties of 42CrMo4 steel.

The analysis comprised three sequential stages: thermal, structural, and modal. The temperature results obtained from the thermal simulations were imported as a thermal load in the static analysis to account for temperature induced effects on the ball screw.

2.3. Thermal Analysis

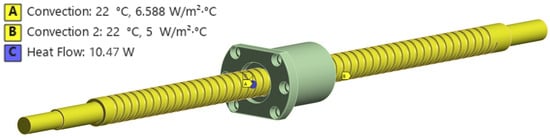

The boundary conditions used for thermal simulation are detailed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Thermal simulation boundary conditions.

The ball–raceway interfaces involve complex rolling contact, continuously changing load paths, and fine geometric features. Explicit numerical modeling of individual balls and their contact with the screw and nut would therefore require highly refined meshes and nonlinear transient contact formulations, resulting in a prohibitive computational cost. Accordingly, and in line with existing studies on ball screw thermal behavior (e.g., [1,6]), the frictional interaction between the balls, screw, and nut can be represented using equivalent friction torque–based heat generation models, expressed in Equations (1) and (2):

where is the lubrication coefficient, is the lubricant kinematic viscosity, is the screw rotational speed, and is the friction torque.

where is friction torque and is the angular speed.

Although Equation (1) is more detailed as it accounts for multiple effects, Equation (2) is used in this study as it captures the dominant frictional effects while simplifying numerical implementation, ensuring a stable and efficient simulation of thermal behavior.

Rotational speed was fixed at 500 rpm, which lies within the experimentally investigated operating range for ball screws [17]. The friction torque was selected as 0.2 N·m, from the experimentally reported range for precision ball screws under typical preload conditions [18]. Using these parameters, assuming full conversion of frictional work into heat, the total frictional heat generation was calculated as 10.47 W. This value was applied as an equivalent heat input in the thermal finite element model to account for frictional heating at the ball–screw and ball–nut interfaces.

It should be noted that this modeling approach is intended to capture the global temperature rise and steady-state thermal response of the ball screw assembly. Local contact stresses and transient temperature variations at individual ball–raceway contacts are not explicitly resolved and are beyond the scope of the present study.

According to known Nusselt number correlations [6], the convective heat transfer coefficient was determined using Equation:

where is convective heat transfer coefficient is Nusselt number is thermal conductivity of the fluid and is characteristic length.

These coefficients were then applied as convection boundary conditions to simulate heat dissipation from the ball screw. A value of 5 W/m2·K was assigned to the external surfaces exposed to ambient air, while coefficient of 6.58 W/m2·K was used to represent the confined airflow between the nut and screw grooves. The selected ambient temperature was 22 °C.

2.4. Structural Analysis

A static structural analysis was carried out to evaluate the deformation and stress distribution in the ball screw assembly under equivalent operating conditions. The boundary conditions are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Static structural simulation boundary conditions (Ux, Uy, Uz: translational displacements).

One end of the screw shaft was constrained against axial and radial translation while remaining free to rotate, representing a fixed support. The opposite end was constrained radially but allowed axial displacement and rotation, corresponding to a floating support. This fixed–floating support configuration prevents rigid-body motion while allowing axial deformation due to thermal expansion, thereby avoiding over-constraint of the screw. The thermal results were used as input for the structural analysis, and a rotational speed of 500 rpm was applied.

2.5. Modal Analysis

The modal analysis was performed to investigate the natural frequencies and mode shapes of the ball screw. A total of 360 vibration modes were extracted to thoroughly examine the dynamic behavior of the ball screw across a wide frequency range.

The dynamic behavior of the system can be expressed by the general equation of motion, which can be derived based on Newton’s law or the Lagrange equation:

where is the mass matrix representing inertia, is the damping matrix that models energy loss, and is the stiffness matrix depending on the screw length and preload . Here, is the displacement vector, is the velocity vector, is the acceleration vector, and represents the external force acting on the system.

Mass participation analysis was performed to check whether the calculated modes are sufficient to capture the complete dynamic behavior of the system. The formulas for mode participation and mass participation (effective mass) are described as [14]:

where is the mode shape vector of mode . is the mass matrix of the system. It represents how the mass is distributed across the structure. is the unit displacement vector in the direction of excitation which can be translation or rotation about an axis.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the simulations, including the mesh convergence study, thermal and structural behavior, and modal analysis. It also discusses their implications.

3.1. Mesh Convergence Study

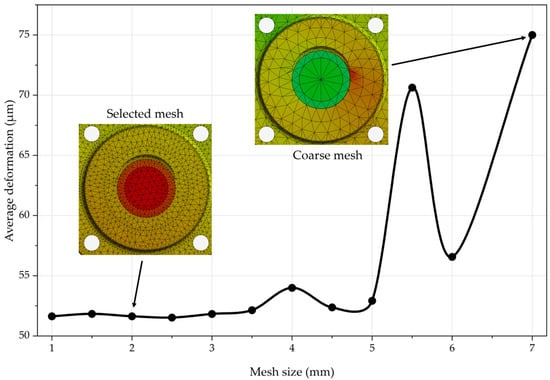

A mesh convergence study was conducted using tetrahedral mesh which is ideal for simulation of complex geometries.

Meshes with element sizes of 4 mm and larger produced unstable results. Stability was achieved when the element size was reduced to below 3.5 mm as shown in Figure 4. However, a 2 mm mesh was chosen to ensure reliable results. Further refinement showed only minimal changes in deformation (within ±2%) ensuring solution accuracy in line with established best practices [19].

Figure 4.

Mesh convergence study showing the effect of mesh refinement on average deformation; different colors correspond to results obtained using coarse and refined meshes.

3.2. Thermal and Structural Analysis Results

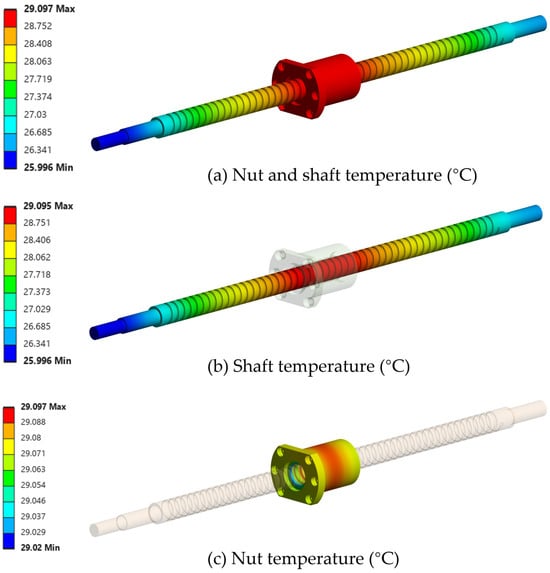

The total temperature distribution along the ball screw was computed and the results are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Temperature results for the ball screw (°C). The figure shows (a) the complete assembly, (b) the screw shaft, and (c) the ball nut.

The results reveal a clear thermal gradient along the screw shaft, with the maximum temperature localized around the ball nut region and gradually decreasing toward both shaft ends. The maximum temperature observed was approximately 29.1 °C, while the minimum was around 25.9 °C, yielding a total temperature rise of about 7.1 °C above the ambient condition (22 °C).

This distribution corresponds well to the expected heat generation pattern due to frictional contact between the circulating balls and the raceways within the nut [5]. In contrast, the threaded portions of the screw away from the nut and the exposed shaft surfaces dissipate heat more effectively through convection to the ambient air, resulting in a nearly linear temperature drop along the screw length.

Furthermore, the predicted temperature distribution and magnitude of temperature rise are consistent with experimental observations reported in the literature, with temperature rises typically below 5–10 °C for rotational speeds up to 2500 rpm [17].

The thermal gradient suggests efficient heat conduction through the 42CrMo4 steel shaft (thermal conductivity = 45.1 W/m·K), which facilitates temperature uniformity and prevents localized overheating. The relatively low maximum temperature rise (≈7 °C above ambient) indicates that, under the given operating conditions, the system maintains thermal stability.

The thermal gradients observed in the ball screw and applied rotational velocity led to thermal expansion and deformation. The total thermal deformation was computed, yielding a maximum displacement of 77.81 μm. This value falls well within the range of thermal elongations reported in experimental investigations of ball screw feed drives, where elongations between approximately 30 and 140 µm have been observed [17].

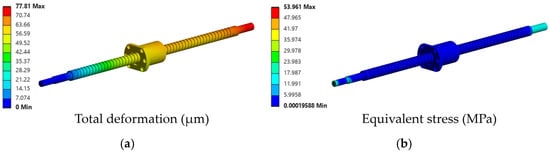

In parallel, the von Mises stress distribution was evaluated to assess the structural integrity under the loads, resulting in a maximum stress of 53.9 MPa as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Simulation results showing (a) total thermal deformation (μm) and (b) equivalent (von Mises) stress distribution (MPa) of the ball screw.

Furthermore, the heat generation and subsequent thermal deformation were compared against the allowable limits for ball screws as defined in ISO 3408 [15]. The analysis confirms that both the thermal rise and the structural response are within acceptable ranges. Consequently, the ball screw demonstrates excellent thermal and mechanical performance under simulated operational conditions, highlighting its suitability for high-precision applications.

3.3. Modal Analysis Results

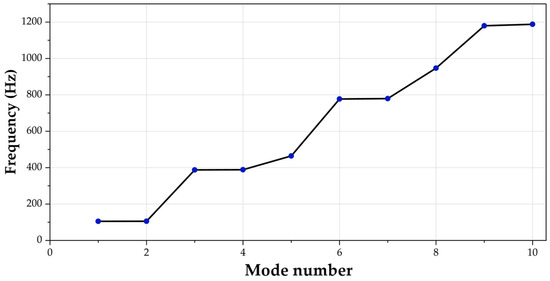

A total of 360 vibration modes were computed to ensure convergence of the cumulative effective mass participation and to confirm that higher-order modes have a negligible contribution to the dynamic response.

The first few modal frequencies are presented in Figure 7 which occur at relatively low frequencies, with Mode 1 and Mode 2 appearing around 105 Hz. As the mode number increases, the frequencies rise sharply. Mode 5 reaches approximately 464 Hz, and by Mode 10, the frequency is near 1188 Hz. The obtained natural frequencies are consistent with previous studies on ball-screw feed drive systems, which report first natural frequencies typically in the range of 100–170 Hz depending on the structural configuration and loading conditions [11].

Figure 7.

First ten mode shapes and natural frequencies (Hz) of the ball screw assembly.

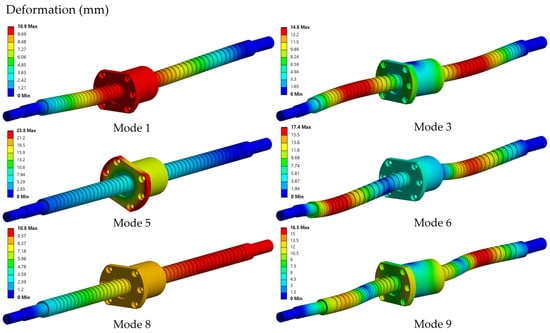

Some of the mode shapes are presented in Figure 8. Only modes with unique deformation patterns are illustrated, as several modes in the low-frequency range have nearly identical frequencies and exhibit similar behavior. This selection provides a clear visual understanding of the global bending and torsional behavior of the assembly.

Figure 8.

Mode shapes of the ball screw assembly for Modes 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9.

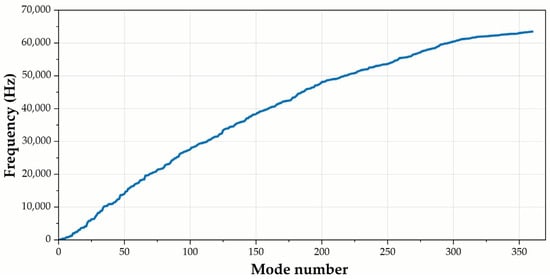

The natural frequencies of all modes obtained are presented in Figure 9. Mid-range modes, between 20 and 60 fall between 4000 Hz and 17,000 Hz, where multiple coupled bending–torsional modes appear, often influenced by screw geometry. Beyond Mode 100, the frequencies increase more gradually, ranging from about 28,000 Hz up to 63,000 Hz at Mode 360, indicating high-frequency local resonances within the screw–nut assembly.

Figure 9.

Frequency distribution of all 360 vibration modes of the ball screw assembly.

This smooth upward trend suggests a well-constrained and stiff system, where the lower modes govern global structural behavior while higher modes correspond to localized vibrations. Overall, the frequency distribution reflects a typical modal response, where fundamental modes dominate low-frequency behavior and complex localized vibrations appear at higher frequencies [20].

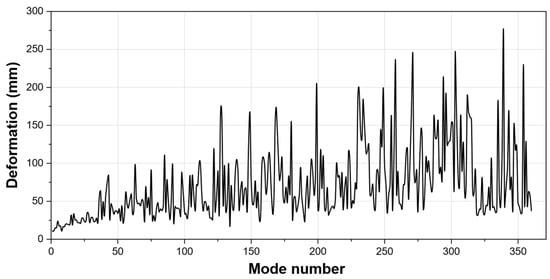

Figure 10 illustrates the deformation patterns across the first 360 vibration modes of the ball screw. The analysis revealed that the deformation patterns varied across the 360 modes, with lower modes (1–20) exhibiting comparatively small deformation patterns representing fundamental global bending and axial vibrations of the screw. Between modes 20 and 100, the deformation increased, indicating the onset of torsional and higher order bending effects. As the mode number increased further, the deformation shapes became more irregular, with pronounced localized and high-frequency vibrations concentrated near the nut. The increasing complexity of deformation at higher modes aligns with findings in previous studies showing that elastic effects become more significant at high speeds and accelerations [11].

Figure 10.

Deformation response of the ball screw assembly across all 360 vibration modes.

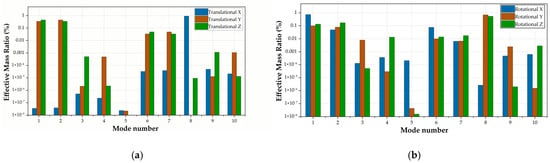

The ratio of effective mass to total mass was evaluated for each of the 360 extracted modes to quantify the contribution of individual modes to the overall dynamic behavior of the ball screw assembly. As summarized in Figure 11, the first few lower-order modes dominate the effective mass in all principal directions, confirming that these modes represent the global vibration patterns of the system.

Figure 11.

Effective mass ratio of first 10 modes. (a) Translational effective mass ratios in the X, Y, and Z directions; (b) rotational effective mass ratios about the X, Y, and Z axes.

In the translational directions, Mode 1 has an effective mass ratio of 0.34 along the Y-axis and 0.44 along the Z-axis, while Mode 2 exhibits the opposite trend, with 0.44 in Y and 0.34 in Z. Together, these two modes account for over 80% of the total effective mass in their respective directions, indicating that they represent the primary bending and lateral translation of the ball screw shaft.

For rotational motion, the first two modes also dominate: Mode 1 contributes 0.73 about the X-axis and 0.13 about the Z-axis, while Mode 2 contributes 0.17 about the Z-axis. Additionally, Mode 8 exhibits significant contributions in both translation and rotation, with 0.9 along the X-axis for translation and 0.69 and 0.53 along the Y- and Z-axes, respectively, for rotation.

Beyond these primary modes, the effective mass ratios decrease sharply, suggesting that the higher-frequency modes are associated with localized deformations such as nut vibrations, thread bending, or shaft torsion.

The cumulative effective mass exceeds 90% within the first 8 modes confirming that the modal extraction is sufficient and that the essential dynamic characteristics of the assembly have been captured [21].

4. Conclusions

The study presents an integrated thermo-structural and dynamic analysis of a ball screw assembly. The model was created in SolidWorks and simulated in Ansys, incorporating thermal, static, and modal analyses to evaluate the combined effects of heat generation, thermal deformation, and vibration under realistic operating conditions. Thermal loading was calculated based on frictional power losses, while convective effects were modeled using established Nusselt number correlations. Structural deformation was assessed under the applied rotational velocity, followed by modal simulations with a focus on mass participation. The simulation results can be summarized as follows:

- The maximum temperature rise was approximately 7.1 °C above ambient, with a peak temperature of 29.1 °C localized around the ball nut region.

- The maximum total deformation was found to be 77.81 µm, and the maximum equivalent (von Mises) stress was 53.9 MPa, remaining well below the yield strength of 42CrMo4 (650 MPa).

- A total of 360 vibration modes were extracted, with the first two modes dominating the system’s effective mass participation (≈80%) and exhibiting natural frequencies near 105 Hz.

The results collectively demonstrate that the ball screw maintains structural integrity, thermal stability, and favorable dynamic characteristics within acceptable limits, validating both the modeling approach and the chosen material.

5. Limitation and Future Work

The following points summarize the limitations of the present study and opportunities for future work:

- The present analysis assumes steady-state thermal conditions and does not account for transient temperature variations that may occur during acceleration or variable loading cycles.

- Ball–nut contact interactions were simplified using a thermal-load substitution approach, which neglects localized heat generation and contact stresses within the raceways.

- The influence of lubrication properties, preload variation, and manufacturing tolerances was not explicitly modeled and may affect real-world performance.

- Experimental validation of the simulated results is recommended to verify the accuracy of thermal and modal predictions.

- Further studies can investigate alternative materials or surface coatings to improve thermal dissipation and wear resistance in high-speed applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A., D.W.J. and O.S.; data curation, O.A., D.W.J. and A.N.; funding acquisition, D.W.J. and J.H.J.; investigation, D.W.J. and J.H.J.; methodology, O.A., A.N., O.S., A.K. and A.T.; project administration, D.W.J. and J.H.J.; resources, D.W.J. and J.H.J.; supervision, D.W.J. and J.H.J.; validation, O.A., A.N., O.S., A.K., A.T. and D.W.J.; visualization, O.A., A.N., O.S., A.K. and A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A., A.N., O.S., A.K. and A.T.; writing—review and editing, J.H.J. and D.W.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the (Jeju Rise Center), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeju Special-Governing Province, Republic of Korea. (2025-RISE-17-001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the authors used Chat GTP Open AI 4o for the re-write of the text to improve its quality. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| APDL | Ansys Parametric Design Language |

| OMA | Operational Modal Analysis |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

References

- Qiu, Y.-L.; Zhou, C.-G.; Ou, Y.; Feng, F.-T. Theoretical and experimental analysis of the temperature rise of a ball screw. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Su, H.; Lu, L.; Chen, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, P. Thermal optimization of an ultra-precision machine tool by the thermal displacement decomposition and counteraction method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 76, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, Y.; Verl, A.; Brecher, C.; Uriarte, L.; Pritschow, G. Machine tool feed drives. CIRP Ann. 2011, 60, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B. Modification of CNC Machine Tool Operations and Structures Using Finite Element Methods: A Review. Jordan J. Mech. Ind. Eng. 2023, 17, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.-J.; Zhao, C.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-M. Adaptive real-time model on thermal error of ball screw feed drive systems of CNC machine tools. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 3853–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-Z.; Choi, C.; Liang, L.-J.; Li, D.-Y.; Lyu, S.-K. Study on a novel thermal error compensation system for high-precision ball screw feed drive (1st report: Model, calculation and simulation). Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2015, 16, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fan, K.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y. Time-varying positioning error modeling and compensation for ball screw systems based on simulation and experimental analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 73, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, I.H.A.; Muhamad, W.M.W.; Reshid, M.N.; Baharudin, N.S. CNC Machine Capability Study Based on Structural and Thermal Analysis of Ball Screw Using Finite Element Method. 2017. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:189920073 (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Oyanguren, A.; Larrañaga, J.; Ulacia, I. Thermo-mechanical modelling of ball screw preload force variation in different working conditions. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 97, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, P.; Gao, C.; Han, Z.; Liu, T.; Gao, W.G.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, D.W. Simulation study on thermal balance-temperature rise characteristics of a precision ball screw-nut pair. J. Tianjin Univ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 52, 725–732. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-S.; Huang, Y.-K.; Cheng, C.-C. Mechanical model and contouring analysis of high-speed ball-screw drive systems with compliance effect. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2004, 24, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatwesh, A.; Fletcher, S.; Longstaff, A.; Pan, W.; Gu, F. Expedient identification of the dynamics of ball-screw drives using online-validation. In Proceedings of the 2017 23rd International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC), Huddersfield, UK, 7–8 September 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, S.; Dadalau, A.; Verl, A. Expedient modeling of ball screw feed drives. Prod. Eng. 2012, 6, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aenlle, M.; Juul, M.; Brincker, R. Modal Mass and Length of Mode Shapes in Structural Dynamics. Shock. Vib. 2020, 2020, 8648769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Ball Screws—Part 2: Nominal Diameters, Leads, Nut Dimensions and Mounting Bolts—Metric Series; International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EN 10083-3:2006; Steels for Quenching and Tempering—Part 3: Technical Delivery Conditions for Alloy Steels. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Zhang, L.-C.; Ou, Y.; Feng, H.-T. Prediction of the Thermal Elongation of the Ball Screw Mechanism under Various Rotational Speeds. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2021, 22, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-C.; Zhou, C.-G. Experimental Study on the Coefficient of Friction of the Ball Screw. J. Tribol. 2022, 144, 031601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-M.; Cai, Y.-H.; Yu, Y.; Geng, X.; Ma, X. Optimal Mesh Criteria in Finite Element Modeling of Human Foot: The Dependence of Multiple Model Outputs on Mesh Density and Loading Boundary Conditions. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2021, 21, 2140034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Chen, T.; Lu, X.; Yi, X. Identification of dominant global and local modes behind dynamic stiffness valleys in BIW structures via modal contribution and ESE. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0334932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, N.; Elrafei, A.; Genidi, M.; Elsaied, T.M.S. Efficient Mass Participation Ratio of Building with Basement. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2017, 14, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.