Abstract

To address the problem of real-time coordinated control in gear selection and power distribution for hybrid energy storage systems, an adaptive real-time optimal control strategy is proposed in this study. Firstly, a vehicle dynamics model with a hybrid energy storage system and a two-speed mechanical automatic transmission (2AMT) is constructed. Next, a nonlinear optimization problem aiming to minimize battery energy consumption is established. To address the challenge of high computational complexity, polynomial fitting and variable substitution are employed to transform the original nonlinear problem into a convex optimization framework. This transformation enables the control variables to be directly obtained through efficient matrix operations with a global optimal analytical solution, thereby significantly improving computational efficiency. The real-time adaptive control strategy achieves forward-looking coordinated optimization of power distribution and gear selection. The simulation results show that the proposed method can achieve an effect similar to that of dynamic programming (DP) in terms of energy consumption but gains much higher computational efficiency. Compared with the rule-based strategy, the battery energy consumption is reduced by approximately 10%. The method demonstrates advantages both in terms of economy and real-time performance.

1. Introduction

Driven by the global goal of carbon neutrality, new-energy vehicles play a significant role in alleviating energy shortages and environmental pollution [1]. However, lithium-ion batteries, which are the main power source for electric vehicles, have shortcomings in terms of energy density, charging speed, and cycle life, which limit the vehicle’s range [2,3]. This problem is particularly prominent in commercial vehicles with complex working conditions and frequent starts and stops.

To enhance the overall vehicle performance, the hybrid energy storage system (HESS), which combines batteries and supercapacitors, has been introduced to balance both range and dynamic requirements, thereby extending the battery lifespan [4,5]. The two-speed automatic mechanical transmission (2AMT) features a simple structure and controllable cost, which optimizes the matching of motor torque and speed [6], improving the energy efficiency of the vehicle in various operating conditions and providing an effective approach for the energy conservation and power optimization of electric vehicles [7]. This is particularly advantageous for commercial vehicles, such as the electric logistics van considered in this study, which experiences significant load fluctuations and frequent start–stops. It would lead to lower overall energy efficiency, especially during low-speed, high-torque demands, such as start-up and climbing.

For vehicles equipped with both an HESS and a 2AMT, the integrated control strategy must simultaneously address gear selection and power distribution under dynamic driving conditions. However, most existing studies focus on either energy management or transmission control independently, leading to suboptimal performance in real-time applications [8]. Control strategies can be categorized into rule-based strategies and optimization-based strategies [9,10].

Rule-based strategies, such as deterministic rule tables [11,12], fuzzy logic control [13,14], and wavelet transform [15], are valued for their simplicity and improved adaptability. However, a fundamental limitation is their reliance on predefined logic based on current or immediate past system states. This reactive nature often prevents them from achieving optimal power distribution, frequently leading to issues such as premature supercapacitor depletion and low overall energy utilization efficiency. Their inherent rigidity makes it challenging to adapt to dynamic driving conditions or achieve a global optimization across multiple, often competing, objectives like energy efficiency, battery longevity, and real-time performance.

Optimization-based strategies aim to overcome these limitations by systematically seeking optimal control actions [16]. These can be further divided into several classes. Global optimization methods like dynamic programming (DP) are fundamental global optimization techniques designed to minimize energy consumption and determine optimal transmission ratios over a known driving cycle [17]. However, their high computational complexity restricts them to offline benchmark studies. Real-time optimization methods include methods that sacrifice global optimality for practical realizability. The equivalent consumption minimization strategy (ECMS) improves real-time performance by adaptively optimizing equivalent factors [18,19]. Intelligent algorithms, such as NSGA-II [20] and neural networks [21], offer powerful ways to handle complex, nonlinear optimization problems. However, they belong to a different class of heuristic search methods that do not offer the same theoretical guarantees and often struggle with computational efficiency. Other advances include stochastic control [22] and Pontryagin’s minimum principle [23], which are often combined with a model predictive control (MPC) framework to enhance robustness using short-term predictions [24]. Reinforcement learning (RL)-based intelligent coordinators have also been explored to enhance system adaptability through online learning. They all possess a significant theoretical advantage but still fall short in terms of real-time responsiveness.

Convex optimization methods enable practical implementation by efficiently solving convex models that simultaneously optimize gear selection and torque distribution [25,26]. Studies [27] have shown that convex optimization-based power allocation can significantly reduce the variance in battery power output and slow down battery capacity decay compared to rule-based methods while achieving high system efficiency. A common challenge is that the original nonlinear model dynamics may require simplification or linearization to fit the convex form, which can compromise accuracy. Furthermore, even with a convex optimization toolbox (CVX), meeting strict real-time requirements can be challenging for complex problems.

The integrated control of hybrid energy storage systems (HESSs) and two-speed automated manual transmissions (2AMT) presents two primary challenges: the multi-objective optimization of gear shifting and power management, and the critical trade-off between real-time operational performance and global energy optimality. To overcome the limitations of existing strategies, this paper proposes a novel hierarchical convex optimization framework. The core innovation involves a mathematical reformulation that transforms the original non-convex optimization problem into a tractable convex form through polynomial fitting and variable substitution. This approach enables the direct derivation of a global optimal solution via efficient matrix operations, successfully bridging the gap between computational efficiency and near-global optimality. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- A vehicle dynamics model and a hierarchical optimization framework are developed. Based on the “prediction-control” framework, this paper proposes a hierarchical control scheme to achieve decoupling and real-time control of gear shifting and power distribution of the power supply.

- A convex optimization strategy is proposed to transform the power allocation problem into a convex quadratic programming form and obtain the global optimal solution non-iteratively through matrix operations, achieving efficient and real-time power allocation between the battery and the supercapacitor.

- The proposed strategy demonstrates real-time performance across diverse system configurations. Its superior computational efficiency, a key advantage over conventional methods, provides a solid foundation for real-time control applications. This conclusion is robustly supported by comparative analyses with both dynamic programming and rule-based methods, showing that the strategy consistently achieves near-global optimality.

2. Vehicle Modeling

This section is dedicated to establishing the mathematical model of the vehicle powertrain, comprising the vehicle dynamics and the hybrid energy storage system (HESS). All equations herein describe the physical relationships and component characteristics that form the basis for the optimization problem.

2.1. Vehicle Structure Description

Electric logistics vehicles often encounter significant load fluctuations during operation, especially during low-speed start-up and climbing phases, where the drive motor needs to provide high torque. Conversely, during high-speed cruising, the motor operates at high speed and lower torque. A single-speed transmission represents a compromise, unable to optimally match both extremes. To enhance the efficiency of the drive motor across this wide range of operating conditions and alleviate the pressure on the power system, this study employs a two-speed mechanical automatic transmission (2AMT). By optimizing the transmission ratio, the operating conditions of the motor are improved. Given the inherent limitations of the power density and cycle life of lithium-ion batteries, supercapacitors are introduced into the power system to construct a hybrid energy storage system (HESS), which reduces the frequency of the batteries being subjected to large current charging and discharging, thereby extending their service life. The basic parameters of the vehicle are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Vehicle parameters and dynamic requirements.

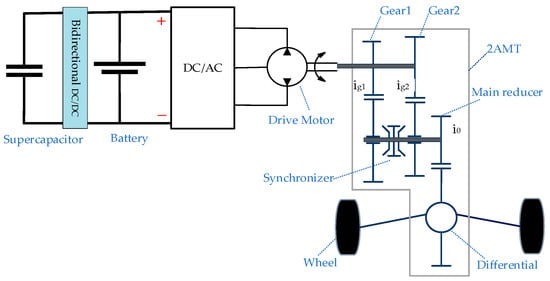

The vehicle topology is shown in Figure 1. The battery is directly connected to the DC bus, and the supercapacitor is connected in parallel with the battery through a bidirectional DC/DC converter. The bidirectional DCDC converter resolves the voltage matching issue through its Buck (downward conversion) and Boost (upward conversion) modes, thereby enabling precise energy routing and leveraging the complementary characteristics of both energy sources. This structure helps stabilize the bus voltage and allows the battery and supercapacitor to supply power to the drive motor independently or collaboratively. The output shaft of the motor is directly connected to the input shaft of the 2AMT, reducing the efficiency loss in the transmission chain.

Figure 1.

Vehicle topology structure.

2.2. Vehicle Dynamics Model

The vehicle driving resistance includes rolling resistance, slope resistance, air resistance and acceleration resistance [4,5,6,7]. Based on the power balance equation, the required driving torque and power at the wheel end can be calculated, respectively, by the following equations.

where and are the road slope and the vehicle speed. is the rotational speed at the wheel end, which can be calculated as

where is the sign of ; when , the drive motor is in driving mode; when , the vehicle is in regenerative braking mode.

Under quasistatic rigid body assumptions, the 2AMT input torque and speed are determined as

Given the transmission efficiency , gear ratio includes the final gear ratio. Since the input shaft of the 2AMT is directly driven by the motor, the output power of the drive motor can be expressed as

and are the output torque and the rotation speed of the drive motor. The total motor power consumption is the sum of the mechanical output power and power dissipation losses . The mathematical relationship is defined as Equation (8), and the basic parameters of the motor are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Drive motor parameters.

2.3. HESS Model

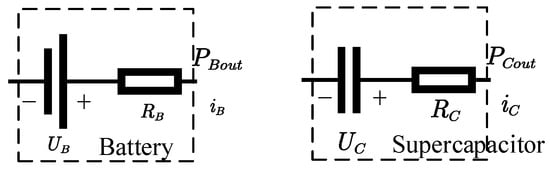

The HESS combines a battery and a supercapacitor via a bidirectional DC/DC converter. To reduce computational load, a simplified Rint model is adopted for the battery model, while the supercapacitor is modeled as an RC equivalent circuit. Corresponding equivalent circuit diagrams are provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Equivalent circuits for battery and supercapacitor.

Battery power consumption is defined as the sum of output power and internal resistive losses .

denotes battery open-circuit voltage, and is internal resistance. The discharge current and state of charge of battery can be calculated as follows:

where is the battery initial , is the maximum battery capacity (), and the constraints for and are

Similar to the battery model, the relationship of supercapacitor power consumption , output power , and power loss can also be expressed as

Supercapacitor current and SOC can be, respectively, expressed as

where is supercapacitor open-circuit voltage, and is internal resistance.

The total motor power consumption equals the combined output power supplied by the battery pack and supercapacitor pack if DC–DC converter losses is neglected, which can be expressed as Equation (20):

3. Optimization Algorithm

This section presents the methodological framework for solving the energy management problem. It focuses on formulating the optimization problem based on the models in Section 2, transforming it into a tractable form, and detailing the solution algorithm. The optimization problem formulation is first determined in Section 3.1; then, a hierarchical optimization framework is adopted, and the complex nonlinear power distribution problem is transformed and solved via convex optimization in Section 3.2; and finally, the overall real-time control process is described in Section 3.3.

3.1. Optimization Problem Formulation

This subsection formally defines the optimization problem, specifying the objective function, state variable, control variables, and constraints, thereby establishing the foundation for the subsequent convex reformulation.

The optimization problem is formulated to minimize battery power consumption by controlling the battery output and the discrete gear ratio , with the supercapacitor SOC as the state variable . The control variables are expressed as . The mathematical formulation is as follows:

Constraints are as follows:

and denote the at the initial time and final time ; and represent the limits of ; and are the limits of ; and and are the two gear ratios of the 2AMT.

Based on the PMP, the Hamilton function can be written as

is the equivalent factor (EF). The goal is to find the optimal control trajectory that minimizes the Hamilton function at each instant subject to the system constraints.

The battery power consumption and both exhibit nonlinear relationships with , resulting in a non-convex Hamiltonian and a terminal constraint. The above optimization problem is a mixed integer programming problem. The complexity of this kind of problem is relatively high, which is needed to handle linear, nonlinear and integer constraints simultaneously; it is usually solved using numerical iterative methods.

3.2. Convex Modeling

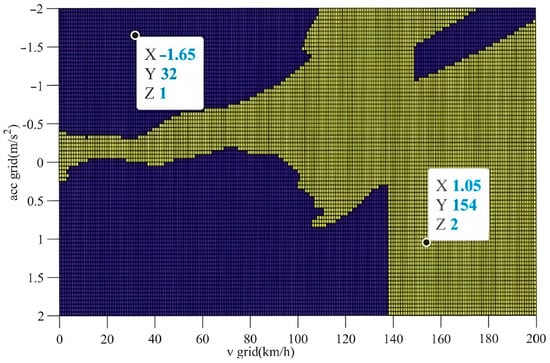

A hierarchical optimization method is proposed to simplify the optimization problem and decouple the two control variables. The first step is to determine the optimal gear offline. Firstly, vehicle speed and acceleration are discretized over typical operating ranges (, −2~2 m/s2). To minimize motor consumption, the optimal gear is selected using the following equations with the lowest motor power consumption, resulting in a gear selection map in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Optimal gear selection map of 2AMT. (The blue area represents the selection of Gear 1, the yellow area represents the selection of Gear 2).

Motor power consumption and correspond to Gear 1 and Gear 2, respectively. During real-time operation, the optimal gear is determined by referring to the gear selection map in Figure 3. For example, Gear 1 is selected at a wheel acceleration of and vehicle speed of , while Gear 2 is chosen at and .

The total motor power demand is first set by the predicted 2AMT gear sequence. For the subsequent real-time power distribution, a new control variable is defined to manage the nonlinear .

The variable is defined as a function of the rate of change in the supercapacitor’s SOC. Referring back to Equation (20), the expression for is exactly the same as the right-hand side of Equation (26). Therefore, . This substitution transforms the original nonlinear and non-convex constraint relationship concerning into a linear relationship regarding the new control variable u. The state-variable differential equations from Equation (22) can be rewritten as

Then, can be written as a function of .

Take the partial derivative of both sides of the equation with respect to

Since the partial derivative is positive, increases monotonically with , so its limits are functions of .

and are the minimum and maximum output power of the battery. Consequently, is parameterized as a quadratic function of :

Due to the omission of battery resistance loss, minimizing total power consumption is equivalent to minimizing . The objective function therefore simplifies to a convex quadratic function of , defined by constants are related to .

The termination constraints of the state variable can be written as

Multiply both sides by , the terminal constraint can be converted into the terminal energy constraint, which can be denoted as

Similarly, by defining a variable , the and can be converted into energy consumption () and the change rate of energy consumption ().

Optimization problem can be algebraically transformed into the following structure:

Constraints can be rewritten as

The Hamiltonian equation is rewritten as

The problem is a convex quadratic programming due to the Hamiltonian’s convexity and linear constraints. It is solved online in a prediction horizon , with the power demand partitioned into driving and braking () modes as follows:

The prediction horizon length is the sum of the driving phase length and braking phase length (). During braking mode, supercapacitor is engaged for braking energy recovery and battery power output maintained at zero.

During braking, the supercapacitor output power () equals the maximum of the recoverable braking power () and the supercapacitor charging power is given by

The total recoverable braking energy during prediction horizon is given by

By discretizing the constraint in Equation (36) and combining it with Equation (43), the terminal energy constraint for the supercapacitor is derived under the principle of energy conservation as

The foregoing analysis enables the following optimization problem formulation; the boundary constraints are temporarily omitted:

The matrixes in Equation (45) are denoted as

The new Lagrange function of Equation (45) can be written as

Take partial derivatives of U and λ, and set the derivatives to zero:

Write the obtained system of equations in matrix form:

Since is symmetrically positively definite, the coefficients of the system are non-singular, so the equation has a unique solution, which can be expressed as

Matrix can be expressed by the following formula:

At this point, through efficient matrix operations, the analytical solution of can be obtained, and the control variables sequence within the prediction period can be calculated. If exceeds the constraint range, the data of the extremum point can be selected, which is as follows:

Update per prediction cycle; and can be calculated by following equations:

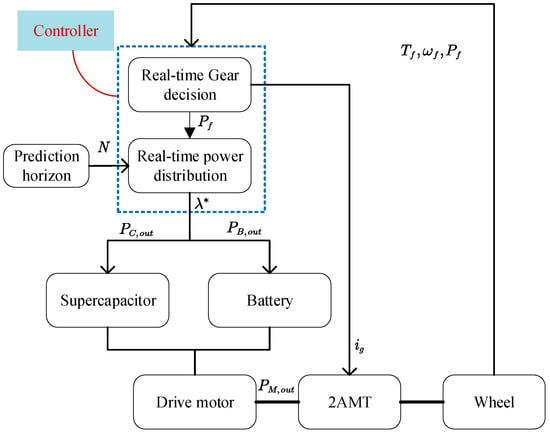

3.3. Real-Time Control Process

The real-time control process is illustrated in Figure 4. First, sensors collect current vehicle speed; the controller uses the current vehicle speed and a predefined prediction horizon to generate predicted speed and acceleration profiles. Subsequently, the optimal gear is determined in real time via a look-up table, and the optimal total demand power over the prediction horizon can be calculated. The required power is then discretized according to the sampling time () and segregated into driving and braking components. The optimal equivalence factor is derived analytically to assign output power setpoints for the battery and supercapacitor. If any power value exceeds operational limits, the Hamiltonian is penalized to infinity (), forcing the corresponding source to operate at its boundary.

Figure 4.

Real-time control process. (The direction of the arrow indicates the direction of power output.)

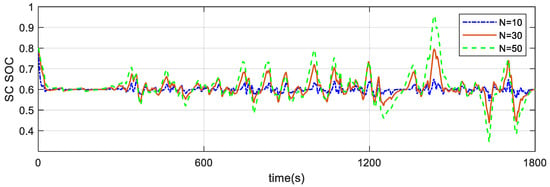

Prediction uncertainty increases with the length of the prediction horizon; SOC stabilization performance exhibits strong dependence on the length of the prediction horizon. To characterize the relationship between the length of the prediction horizon and supercapacitor SOC variability, supercapacitor SOC profiles under three prediction periods () is compared in Figure 5. It shows that under identical operating conditions, a longer prediction period significantly increases the fluctuation amplitude of the capacitor SOC, with the effect being most pronounced at , while the shortest period () minimizes SOC fluctuation. It also limits the capacitor’s ability to perform effective peak-shaving and valley filling, thereby reducing battery energy economy. In order to strike a balance between peak shaving and valley filling utilization and the stability of battery state of charge (SOC), a 30 s prediction horizon () is selected as the optimal prediction length.

Figure 5.

The maintenance of the supercapacitor SOC under different prediction horizons.

A time-varying target terminal SOC update rule is proposed to curtail prediction error effects, which is determined as

where is the modified target terminal SOC, represents the target terminal SOC for the actual cycle, and the current SOC.

4. Results

4.1. Economic Performance

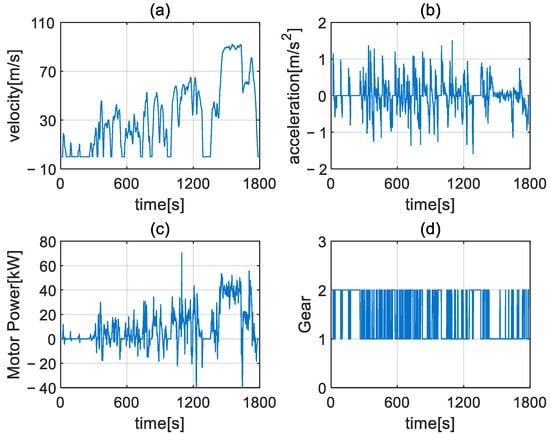

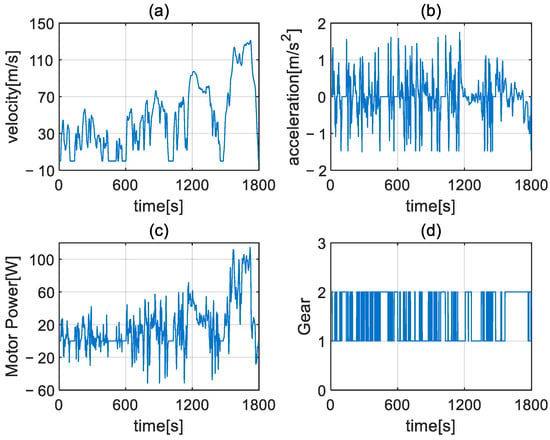

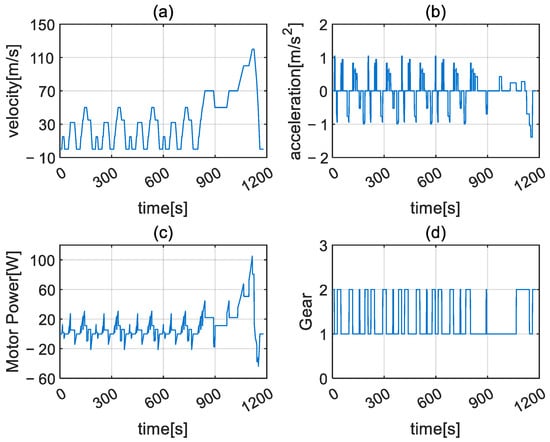

To verify the performance of the electric drive system structure and control strategy proposed in this paper, tests were conducted under three typical load cycle conditions: the Chinese Light-duty Vehicle Test Cycle (CLTC-C), the Worldwide Light-duty Vehicle Test Cycle (WLTC), and the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC). The operation data of the motor and the 2AMT under each condition are plotted in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively. Taking Figure 6 as an example, it shows the time series curves of key parameters under the driving cycle of CLTC-C. Figure 6a is the vehicle speed (km/h), Figure 6b is the vehicle acceleration (m/s2), Figure 6c is the total power consumption of the motor (W) after applying the shift strategy proposed in this paper, and Figure 6d shows the optimal gear selection sequence of the 2AMT transmission during this process. Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the test data under the WLTC and NEDC conditions, respectively, in the same structure.

Figure 6.

Driving cycle of CLTC_C: (a) vehicle speed; (b) vehicle acceleration; (c) drive motor power; (d) selected gear of 2AMT.

Figure 7.

Driving cycle of WLTC: (a) vehicle speed; (b) vehicle acceleration; (c) drive motor power; (d) selected gear of 2AMT.

Figure 8.

Driving cycle of NEDC: (a) vehicle speed; (b) vehicle acceleration; (c) drive motor power; (d) selected gear of 2AMT.

The gear ratio election principle of the transmission should be clarified first, which is essentially a multi-objective trade-off process. Based on the vehicle’s dynamic requirements listed in Table 1, to achieve a 20% climbing slope at a speed of 10 km/h and a maximum speed of 135 km/h, the feasible range of gears needs to satisfy the following constraint equations:

denotes the drive motor’s rated peak torque capability. The range of the transmission ratio is [6.73, 12.6]. Three powertrain systems are selected for comparison: a 2AMT with gear ratios of and , a single-gear reducer with a gear ratio of , and a single-gear reducer with a gear ratio of .

To evaluate the control performance, three strategies were applied to the powertrain systems: the optimization strategy proposed in this study (OPT), dynamic programming (DP), and a rule-based control method (RB). The initial state of charge (SOC) for both the battery and supercapacitor was set to 0.8. Table 3 compares the battery energy consumption of two powertrain configurations (2AMT; Reducer1 and Reducer2) under three control methods (OPT, DP, and RB) across three test cycles (CLTC_C, WLTC, and NEDC). The values in parentheses indicate the percentage increase in energy consumption for the reducer-equipped system relative to the 2AMT baseline under the same control strategy.

Table 3.

Comparison of economic performance.

The data in Table 3 demonstrate that both the powertrain configuration and energy management strategy significantly influence the energy consumption of electric vehicles. As for the superiority of the integrated powertrain, the consistent 11–19% higher energy consumption of the single-gear reducer configurations, even under OPT control, underscores the critical role of the 2AMT in optimizing motor operational efficiency. This validates the necessity of the integrated control problem addressed in this study.

The proposed strategy shows a maximum deviation of only 2–3% between its battery energy consumption values and the global optimal values obtained by dynamic programming (DP) across all driving cycles (such as CLTC-C, WLTC, and NEDC). This indicates that this method efficiently captures the potential for system energy savings. Compared with the rule-based (RB) strategy, the OPT strategy can continuously reduce battery energy consumption by approximately 10%, for instance, from 5.79 kWh to 5.2 kWh in the CLTC-C mode, highlighting its significant economic improvement and practical application advantages.

4.2. SOC Performance

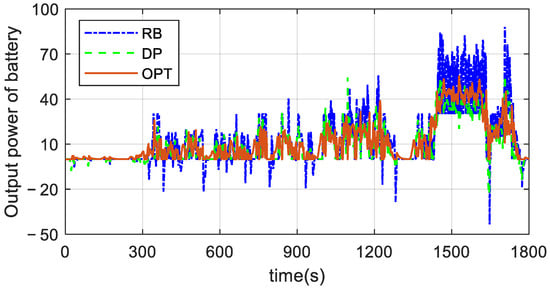

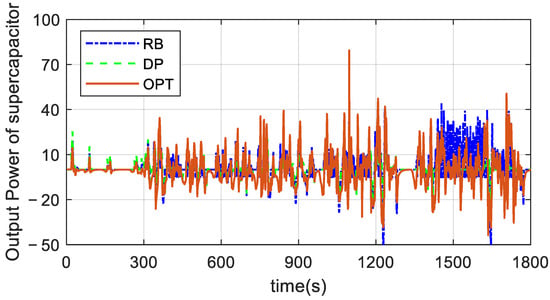

The vehicle demand power curve under the CLTC-C condition is shown in Figure 6c, with the peak discharge power reaching 80 kW and the maximum feedback power reaching 40 kW. Based on this power boundary, Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the output power of the battery and supercapacitor to compare the power distribution effects under the three control strategies.

Figure 9.

Comparison of battery output power under three control methods.

Figure 10.

Comparison of supercapacitor output power under three control methods.

Supercapacitors are mainly responsible for dealing with high-frequency power fluctuations. However, the output power of the supercapacitors shown varies significantly under different control strategies. In Figure 10, we can conclude that the output power of the capacitor fluctuates frequently within the constraints under the RB strategy, while the DP and OPT strategies can better control the power changes, allowing the supercapacitor to mainly play the role of “peak shaving and valley filling”, serving as a buffer.

In terms of battery output power in Figure 9, the RB strategy has significant fluctuations, while the DP strategy achieves the smoothest power output through global optimization. The OPT strategy is similar to the DP in performance, with a much higher smoothness than RB, and can limit the battery discharge rate within 1.5 C, providing effective overload protection for it.

The economic advantage reported in Table 3 is directly attributable to the effective power splitting strategy visualized in Figure 9 and Figure 10. The OPT strategy, similar to DP, smooths the battery power output and leverages the supercapacitor for high-frequency dynamics. This not only reduces energy losses but also mitigates battery stress, contributing to longer battery lifespan—an important benefit beyond the immediate energy consumption metrics in Table 3. The rule-based strategy’s higher consumption is a direct consequence of its inefficient power allocation, leading to increased battery current stress and higher resistive losses.

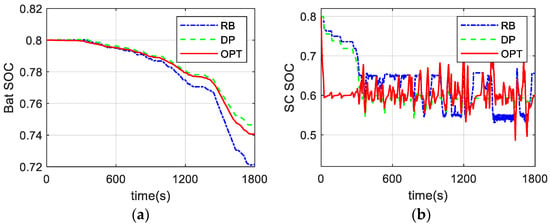

In order to have a more intuitive comparison of the control effect, Figure 11 shows the change in battery SOC and supercapacitor SOC. Figure 11b shows that all three strategies can keep the supercapacitor SOC within a reasonable range of 0.4 to 0.8. In the initial stage, all strategies prioritize the use of supercapacitors, causing their SOC to drop rapidly from 0.8 to 0.6; then, the battery begins to play a major role. The supercapacitor is prioritized for charging in the braking stage. Under the RB strategy, the battery SOC continuously decreases slowly and reaches a final value, which is the lowest among the three, indicating the highest battery energy consumption; the battery SOC curves of DP and OPT are very similar, demonstrating a higher overall energy efficiency. The proposed control strategy not only reduces energy losses but also mitigates battery stress, as evidenced by the smoother battery power output shown in Figure 9 and the stable SOC profiles of both the battery and supercapacitor shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Battery SOC and supercapacitor SOC comparison with three control strategies in CLTC_C. (a) Battery SOC. (b) supercapacitor SOC.

Table 4 summarizes the battery terminal SOC and single-step calculation efficiency data of the composite power system with the 2AMT structure under different operating conditions. Taking the CLTC_C condition as an example, the battery terminal SOC obtained with the OPT control strategy under the same transmission system is 0.74, which is very close to the result of the DP strategy (0.75) and significantly better than the result of the RB strategy (0.72), indicating that OPT has achieved nearly optimal results in energy management. In terms of calculation time, the OPT strategy demonstrates significant advantages, with its single-step calculation time being only 6.5 × 10−5 s, at the microsecond level, which is comparable to the RB strategy (7.6 × 10−5 s). The proposed analytical approach attains global optima via efficient matrix operations, significantly improving computational efficiency, with an average calculation time per step on the order of 10−4 s. This means that OPT outperforms the RB strategy in control effectiveness and does not significantly increase the time cost. In contrast, the single-step calculation time of the DP strategy is as long as 1.13 s, which fails to meet the response speed requirements of real-time control systems. In vehicle energy management, the system usually needs to respond to power demand at millisecond-level frequencies or even higher. Therefore, the DP strategy is generally only used as an offline calculation performance benchmark and cannot be directly applied to online control. The tests under the WLTC and NEDC conditions also obtained similar conclusions.

Table 4.

SOC performance and average calculation time under different control strategies.

In summary, the optimization strategy (OPT) has a decisive advantage in calculation efficiency. It not only overcomes the real-time application limitations of DP due to long calculation times but also exceeds the performance of the RB strategy, achieving a good balance between control quality and calculation efficiency. Combined with the conclusion of Table 3, the combination configuration of the OPT control strategy for the 2AMT transmission system is the optimal solution, taking into account both high efficiency and engineering feasibility.

5. Conclusions

An adaptive real-time optimal control strategy for hybrid energy storage systems based on convex optimization models is proposed, and an iterative analytical solution method is developed, providing a theoretical basis for real-time control. The main contributions are as follows:

- Model and problem formulation: A mathematical model is established for an electric vehicle equipped with a battery–supercapacitor hybrid energy storage system and a two-speed automated manual transmission. With the economic efficiency of battery energy consumption as the optimization objective and gear shifting and power allocation as control variables, a hierarchical optimization architecture is designed to achieve real-time control.

- Convex reformulation and efficient solution: Through variable substitution and function fitting, the original nonlinear optimization problem is transformed into a convex quadratic programming model. This reformulation allows for the direct derivation of an analytical solution for the optimal equivalent factors in power allocation. Compared to traditional numerical methods that rely on iterations, the proposed analytical approach attains global optima via efficient matrix operations, significantly improving computational efficiency.

- The proposed optimal control strategy successfully achieves the optimal balance between control optimality and real-time computing. It not only addresses the problem of complex calculations, which prevent the dynamic programming strategy from being applied in real time, but also overcomes the limitations of the rule-based strategy, such as its poor adaptability. After verification under various operating conditions, it was found that compared with the rule-based method, battery energy consumption can be reduced by more than 10%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y. and B.W.; methodology, M.Y.; software, B.W.; validation, B.W.; M.Y. and S.H.; formal analysis, B.W.; investigation, B.W.; resources, M.Y. and Z.Y.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W.; writing—review and editing, B.W. and M.Y.; visualization, B.W.; supervision, N.Z.; project administration, M.Y.; funding acquisition, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52102423), China and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities: (Grant No. JZ2024HGTB0204), China.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schleussner, C.-F.; Rogelj, J.; Schaeffer, M.; Lissner, T.; Licker, R.; Fischer, E.M.; Knutti, R.; Levermann, A.; Frieler, K.; Hare, W. Science and policy characteristics of the Paris Agreement temperature goal. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aphale, S.; Kelani, A.; Nandurdikar, V.; Lulla, S.; Mutha, S. Li-ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles: Requirements, State of Art, Challenges and Future Perspectives. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Power and Energy (PECon), Virtual, 7–8 December 2020; pp. 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Hicks-Garner, J.; Sherman, E.; Soukiazian, S.; Verbrugge, M.; Tataria, H.; Musser, J.; Finamore, P. Cycle-life model for graphite-LiFePO4 cells. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 3942–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, C.V.V.M.; Ramesh, R. Review of battery-supercapacitor hybrid energy storage systems for electric vehicles. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaresan, N.; Rammohan, A. A comprehensive review on energy management strategies of hybrid energy storage systems for electric vehicles. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Z. Impacts of Two-Speed Gearbox on Electric Vehicle’s Fuel Economy and Performance. Eng. Environ. Sci. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Meng, D.; Shi, W.; Cai, W.; Dong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H. Topology optimization and the evolution trends of two-speed transmission of EVs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuanming, S.; Yajie, L.; Guang, J.; Xucheng, H. Review of energy management methods for lithium-ion battery/supercapacitor hybrid energy storage systems. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Z. Development of energy management system based on a rule-based power distribution strategy for hybrid power sources. Energy 2019, 175, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukajlović, N.; Milićević, D.; Dumnić, B.; Popadić, B. Comparative analysis of the supercapacitor influence on lithium battery cycle life in electric vehicle energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2020, 31, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; He, H.; Xiong, R. Rule based energy management strategy for a series–parallel plug-in hybrid electric bus optimized by dynamic programming. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z. Load-adaptive real-time energy management strategy for battery/ultracapacitor hybrid energy storage system using dynamic programming optimization. J. Power Sources 2019, 438, 227024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumediene, S.; Nasri, A.; Hamza, T.; Hicham, C.; Kayisli, K.; Garg, H. Fuzzy logic-based Energy Management System (EMS) of hybrid power sources: Battery/Super capacitor for electric scooter supply. J. Eng. Res. 2024, 12, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaresan, N.; Rammohan, A. Adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system based optimized energy management strategy for the power integration of battery and supercapacitor in electric vehicle. J. Energy Storage 2025, 126, 117073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasrouri, M.; Charrouf, O.; Betka, A.; Abdeddaim, S.; Tiar, M. Adaptive wavelet-fuzzy energy management system for battery-supercapacitor energy storage system in electric vehicles integrating driving pattern recognition. J. Energy Storage 2025, 129, 117330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgovski, N.; Hu, X.; Johannesson, L.; Egardt, B. Combined Design and Control Optimization of Hybrid Vehicles. In Handbook of Clean Energy Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; He, R.; Xu, Y. Design of an Energy Management Strategy for a Parallel Hybrid Electric Bus Based on an IDP-ANFIS Scheme. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 23806–23819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Han, S.; Tian, X.; Zhijia, J.; Cao, Y.; Xue, M. Adaptive real-time ECMS with equivalent factor optimization for plug-in hybrid electric buses. Energy 2024, 304, 132014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Liu, S.; Zhu, H.; Feng, Y.; Dong, Z. Real-time optimal control of an LNG-fueled hybrid electric ship considering battery degradations. Energy 2024, 296, 131170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, Y. A real-time optimization energy management of range extended electric vehicles for battery lifetime and energy consumption. J. Power Sources 2021, 498, 229939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Jemei, S.; Wimmer, G.; Hissel, D. Nonlinear autoregressive neural network in an energy management strategy for battery/ultra-capacitor hybrid electrical vehicles. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2016, 136, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Deng, W.; Li, G. Stochastic Control of Predictive Power Management for Battery/Supercapacitor Hybrid Energy Storage Systems of Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 3023–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; Qi, L.; Weirong, C.; Guorui, Z. An Energy Management Method Based on Pontryagin Minimum Principle Satisfactory Optimization for Fuel Cell Hybrid Systems. Proc. CSEE 2019, 39, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Xiao, F.; Chang, C.; Shao, Y.; Song, C. Adaptive Model Predictive Control-Based Energy Management for Semi-Active Hybrid Energy Storage Systems on Electric Vehicles. Energies 2017, 10, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourabdollah, M.; Egardt, B.; Murgovski, N.; Grauers, A. Convex Optimization Methods for Powertrain Sizing of Electrified Vehicles by Using Different Levels of Modeling Details. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 1881–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Tang, X.; Hu, X.; Lin, X. Convex optimization-based predictive and bi-level energy management for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Energy 2022, 257, 124672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nüesch, T.; Elbert, P.; Flankl, M.; Onder, C.; Guzzella, L. Convex Optimization for the Energy Management of Hybrid Electric Vehicles Considering Engine Start and Gearshift Costs. Energies 2014, 7, 834–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.