Abstract

During the launch phase of a carrier rocket, the spacecraft carried by the rocket will be subjected to strong vibrations from the rocket body. Therefore, based on the special working conditions during the rocket launch phase, a passive-tuned magnetorheological (PT-MR) damper using the magnetorheological (MR) composite was proposed, which achieves stable and efficient operational performance using permanent magnets (PMs). Firstly, the influence of squeeze mode on the performances of the MR composite was analyzed for different vibration conditions. Then, by analyzing the squeeze strengthening effect of the MR composite and the influence of non-uniform radial gap size on the damping force, the mechanical model of the proposed damper was derived. Furthermore, the damper prototype was fabricated and its mechanical properties were tested, and the test results showed that the proposed damper can generate a damping force exceeding 800 N. Finally, the vibration isolation effectiveness of the proposed damper was verified from a system perspective by building the simulation model of whole-spacecraft vibration isolation.

1. Introduction

During the launch phase of a carrier rocket, the rocket-borne spacecraft will be subjected to strong vibrations from the rocket body, which will affect the normal operation of the spacecraft and rocket equipment and even cause serious consequences, such as spacecraft launch failure [1,2]. The vibration isolation and energy dissipation performance of the whole-spacecraft vibration isolation system is crucial as the isolation device between the spacecraft and the rocket [3,4,5].

The main contradiction currently faced by whole-spacecraft vibration isolation technology is the requirement for good stiffness and damping characteristics during the low-frequency resonance stage and the requirement for low dynamic stiffness and small damping characteristics during high-frequency vibration. This contradictory demand poses significant challenges for the design of vibration isolators. Therefore, the dynamic range of the damping force becomes an important indicator affecting the broadband vibration isolation performance of the damper. Existing whole-spacecraft vibration isolation systems can be divided into passive [6,7], active [8,9,10], and semi-active [11,12,13] systems. Currently, widely used passive vibration isolation technology has the advantage of high reliability and can achieve vibration isolation under specific working conditions without additional energy input. However, it often cannot meet the requirements of both low-frequency resonance and high-frequency vibration isolation at the same time. Therefore, active vibration isolation technology has emerged. Many studies [14,15] have proposed multi-axis active vibration isolation platforms whose stiffness or damping can be adjusted according to the requirements of the vibration environment. This has to some extent solved the problem of broadband vibration. However, due to the complexity of the active system, its reliability still needs to be further verified.

As a compromise between passive and active isolation technologies, the semi-active isolation system has the advantages of simple and reliable structure, adjustable damping, etc., and it is the research focus of whole-spacecraft vibration isolation systems. As a component of the semi-active system, the magnetorheological (MR) damper has the advantages of rapid response, large output force, low power consumption, and strong anti-interference ability, which is very suitable for the working conditions of whole-spacecraft vibration isolation. According to the different working conditions of MR fluid at the damping gap, the working modes of the MR damper can be divided into flow mode [16], shear mode [17,18], squeeze mode [19,20], and a combination [21,22] of these three basic working modes. Among them, the damper under the flow mode has a large output force, but the high-frequency hardening effect is severe and the dynamic range is small, which is not conducive to medium–high-frequency vibration isolation. Under the squeeze mode, the damping force of the damper is large, but the stroke is short. The MR damper under the shear mode is less affected by high-frequency hardening and has a long stroke, making it suitable for broadband vibration isolation conditions. However, its peak damping force is less than that of the flow mode.

To increase the peak damping force of the MR damper, the mainstream approach is to design high-performance dampers based on the flow mode. Senkal et al. [23] developed a meandering magnetic flux path to regulate MR fluid by optimizing the magnetic circuit design. Compared with the commercial MR damper, this rotary MR damper with a meandering magnetic circuit has approximately 2.7 times the damping force while reducing its volume by 1/3. Mao et al. [24] designed an MR damper with a folding channel structure, placing excitation coils usually wound around the piston on both sides of the damper cylinder and designing the piston as a rotating body with an I-shaped cross-section. Based on the proposed structure, a larger dynamic range of the damping force was achieved, and an additional increase in damping force was also obtained. From this, it can be seen that some scholars have conducted research on the performance-enhanced mechanisms of MR dampers, but the structures involved, such as irregular pistons and folding channels, are relatively complex, which reduces the reliability of MR dampers.

At present, the application scope of MR vibration isolation technology mainly focuses on low-frequency and large-amplitude vibration scenarios. With the development of the aerospace industry, some scholars have also conducted research on MR dampers with broadband vibration isolation capabilities required for medium–high-frequency vibration isolation conditions. However, further research is needed on the mechanism of MR broadband vibration isolation. Zuo et al. [25] considered the pressure distribution and local loss of flow in the liquid chamber, modified the high-frequency model of the MR damper, and optimized the damper structure based on the modified model. The results showed that reasonable selection of structural dimensions can significantly reduce the high-frequency hardening effect of the MR damper, but the damper designed based on the modified model still has the deficiency of energy dissipation reduction under high-frequency conditions. Wu et al. [26] developed a passive-tuned MR damper under shear mode for the aviation field, which solves the problem of leakage and dripping of the damper in special fields. The test results show that the dynamic range of the damping force is approximately 4.6, and stable performance can also be ensured under medium–high-frequency and micro-amplitude conditions. Furthermore, the elastic properties of the material are not obvious. However, its peak damping is relatively low at only 77.4 N, which to some extent limits its application scope. The study by Goldasz et al. [27] showed that fluid inertia and compressibility have a significant impact on the output performance of the damper under high-frequency excitation. Based on this, Dong et al. [28] proposed a compact MR damper with a pressure control mechanism. A critical model of the MR fluid under medium–high-frequency excitation was established considering liquid inertia and compressibility, and the critical model was verified through experiments to effectively predict the performances of MR dampers under medium–high-frequency vibration.

In addition, some scholars have conducted research on the structural design of MR dampers suitable for whole-spacecraft vibration isolation. Tu et al. [29] designed an MR damper with a high-frequency decoupling structure, which mainly involves setting decoupling springs between the piston and the piston rod. Under low-frequency excitation, the piston and the piston rod move together, and the damper outputs a large magnetic induced force. Under high-frequency excitation, the piston rod is decoupled from the piston structure, and the damper only outputs the elastic force of the decoupling spring. The decoupling structure effectively avoids the elastic squeeze of the liquid inside of the MR damper under high-frequency vibration, expanding the working frequency range of the damper. However, this structure increases the gap between the limit baffle and the piston, which to some extent reduces the low-frequency performance of the MR damper. Cheng et al. [30] proposed a novel MR damper with a meandering magnetic circuit to improve the damping performance. The experimental results show that when the input current exceeds 0.75 A, the equivalent damping and damping coefficient of the proposed damper are greater than those of traditional MR dampers. But, for aerospace equipment, the demand for MR dampers is more stable and simpler, which can ensure that damping cannot be lost in cases of accidental power loss, thereby providing better performance.

This paper addresses the issues of insufficient dynamic range and complex structures of shock absorbers in the current working conditions of whole-spacecraft vibration isolation. A passive-tuned MR (PT-MR) damper based on permanent magnets (PMs) and MR composite is proposed to improve platform stability while ensuring the vibration isolation effect. The main contents of this work include the characterization of the mechanical properties of the MR composite, as well as the design, simulation, and testing analysis of the PT-MR damper. A two-degree-of-freedom vibration isolation platform for the whole-spacecraft was built, and we verified the effectiveness of vibration isolation performance of the proposed PT-MR damper through system simulation.

2. Structure of Proposed MR Damper

2.1. Structural Design

The traditional MR damper under shear mode generates a magnetic field through an excitation coil, changes the rheological properties of the MR fluid at the working gap, and adjusts the output force of the MR damper. This regulation method introduces external excitation and reduces the reliability of the damper, and the output characteristics are limited by the magnetic saturation phenomenon of the MR material. Therefore, a PT-MR damper was proposed, which uses PMs instead of excitation coils to mechanically adjust the magnetic flux density at the damping gap, increasing the reliability of the damper structure.

In order to address the various challenges that conventional MR materials encounter in complex vibration, we propose to apply the MR composite [31] developed by the team as the working medium (base liquid MRF-G28, with a density of 2960 kg/m3, operating temperature range of −40~150 °C, shear stress at 0.5 T ≥50 kPa; Chongqing Materials Research Institute Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China) to the whole-spacecraft vibration isolation system, which improved the comprehensive performance of the material compared to traditional MR fluid. Because the polypropylene non-woven fabric in the MR composite has superior oil absorption performance, it can absorb more than ten times its own weight of oily materials and store them in the fiber voids. Moreover, due to the porous fiber characteristics inside, it can to some extent hinder the movement and sedimentation of internal magnetic particles. Combined with the adjustable damping gap structure designed, the damping force capability and stability of the damper can be effectively enhanced through a squeeze strengthening effect.

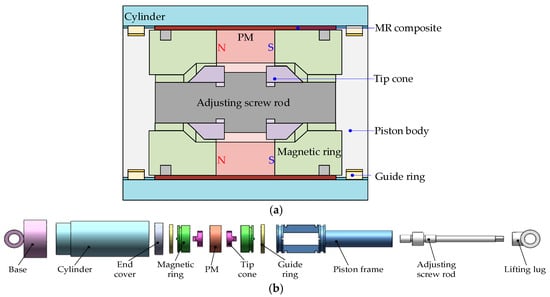

Figure 1 illustrates the working principle of the PT-MR damper. The piston’s assembly consists of two PMs (model: N42, NdFeB magnet, Shenzhen Xinchuang Magnets Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) and magnetic rings (20# steel, China standard), and the PMs are magnetized axially to determine a magnetic circuit perpendicular to the damping gap. An adjusting screw rod is installed inside of the piston, and forward and reverse threads are machined on the screw rod (brass), which rotate with the left and right tip cones, respectively (45# steel, China standard). The MR composite is located between the piston and the inner wall of the cylinder (20# steel, China standard). When the piston moves, the MR composite is subjected to shear force and generates a controllable damping force under the action of the magnetic field. Furthermore, by rotating the adjusting screw rod in the forward direction, the axial movement of the left and right tip cones can be controlled, pushing apart the upper and lower PMs and the magnetic rings and reducing the working gap size. As a result, the MR composite is compressed, enhancing the MR effect of the composite and increasing the output damping force.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the PT-MR damper: (a) main body structure of piston, (b) exploded view of the PT-MR damper.

The PT-MR damper, based on this working principle, can theoretically adjust the output damping force from zero (frictionless state) due to its adjustable gap size, with a wide adjustable range. Moreover, due to the squeeze strengthening effect of the MR composite at the damping gap, it can generate a larger output force than traditional shear mode MR dampers under the same structure size. The exploded view of the PT-MR damper is shown in Figure 1b.

2.2. Analysis of Squeeze Strengthening Mechanism

At present, the squeeze strengthening theory for MR fluid mainly focuses on the following two aspects for analysis:

- (1)

- The squeeze process will lead to an increase in the density of magnetic particles in the MR fluid. Due to the compressibility of silicone oil as the carrier liquid of the MR fluid, its total volume decreases under pressure, and the content of magnetic particles per unit volume increases. Under the action of the magnetic field, the number of magnetic chains formed by particles per unit volume increases, thereby increasing the shear stress of MR fluid.

- (2)

- The squeeze process will promote the transformation of a single magnetic chain in the MR fluid into more complex structures, such as dual chains, multiple chains, and magnetic particle columns. Compared with the single-chain structure of magnetic particle, the complex chain structure can resist stronger external shear, thereby increasing the shear stress of the MR fluid [32].

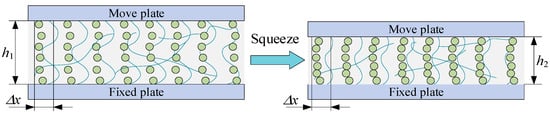

However, unlike traditional MR fluid, MR composite uses non-woven fabric as the matrix, so the magnetic particles are restrained by the fibers of the non-woven fabric. Even without applying a magnetic field, it is not easy to change the spatial position of the ferromagnetic particles on the non-woven fabric. Therefore, the squeeze process of the MR composite can be described in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Squeeze process of MR composite.

As shown in the figure, during the squeeze process of the MR composite, particles are adsorbed onto porous fibers, the particle chains will form a more stable, column-like structure along the squeeze direction, and the number of magnetic particles within the unit length Δx corresponding to the infinitesimal does not change. Meanwhile, the response process of the MR material to the magnetic field is in the millisecond level, which is much less time-consuming than manually adjusting the gap size. Therefore, the following assumption can be made: the squeeze process of the proposed MR composite is a quasi-static process, and the magnetic particles in the composite are fixed by porous fibers, so there is no flow during the squeezing process.

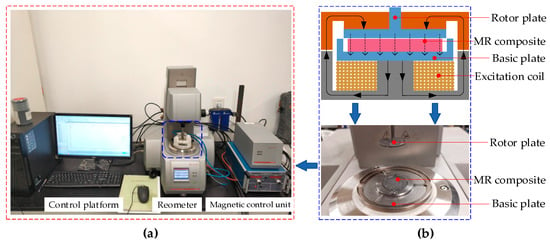

In order to visually verify the effect of squeezing on the material, the MRC301 rheometer produced by Anton Par was used to test the rheological properties of the MR composite, as shown in Figure 3. The diameter of the probe used for testing is 20 mm, the testing gap is 0.7 mm~1 mm, and the water temperature is controlled at 25 °C. Based on the test conditions of the rheometer, 3 layers of the MR composite with a diameter of 25 mm were used to fill the test gap, and the rheological properties of the MR composite under different magnetic fields were tested in different squeeze states (1 mm gap size is the un-squeezed state, 0.7 mm gap size is the squeezed state).

Figure 3.

Experimental set-ups of the MR porous fabric composite. (a) Experimental system and (b) main body of the test.

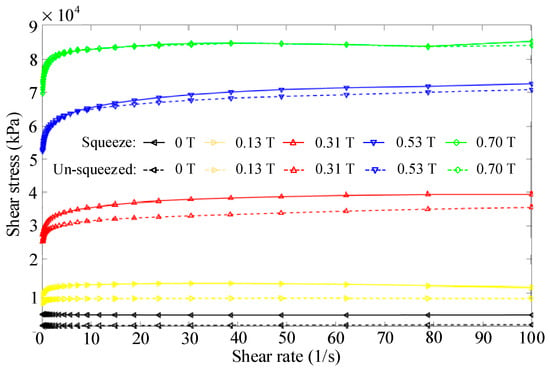

Figure 4 shows the test results of the MR composite under different squeeze states. As shown in the figure, squeeze has a certain improvement effect on the rheological properties of the MR composite, but the improvement effect weakens with the increase in magnetic flux density. At a magnetic flux density of 0.13 T, squeeze can increase the shear yield stress of the composite by 39.9%. However, the improvement effect weakens to 3.7% at a magnetic flux density of 0.53 T, and the improvement effect of squeeze on the MR composite is very weak at 0.70 T. Analysis suggests that squeeze mainly enhances the structural stability of the non-woven fabric matrix, resulting in greater shear stress in the composite under a low magnetic field. As the magnetic flux density increases, the magnetic chain structure in the matrix gradually replaces the non-woven fabric matrix as the main strength structure of the MR composite. The increase in magnetic field does not significantly improve the magnetic chain strength, so the squeeze strengthening effect of the MR composite is weak under the high magnetic field. At the same time, the test gap in the squeezed state may be too small, causing the composite to lose some of the MR fluid adsorbed inside of the fabric, resulting in a weak strengthening effect under high magnetic fields.

Figure 4.

Test results of MR composite under different squeeze states.

Based on the analysis above, a theory for the squeeze strengthening effect of the MR composite was proposed:

where τy is the strengthening shear stress of the MR composite, τ0 is the initial shear stress of the MR fluid, δ is the volumetric strain of the MR composite, Cmag is a comprehensive influence coefficient related to the matrix and the magnetic flux density [33], ΔV is the change in volume, V0 is the initial volume, and V is the volume of the MR composite. The shear stress of the MR composite is not only influenced by their own material properties but also by the volumetric strain and the magnetic field. When the magnetic flux density remains constant, the shear stress and the volumetric strain of the MR composite are linearly related. The higher the degree of squeeze and the greater the volumetric strain, the greater the shear stress of the MR composite.

2.3. Mechanical Model

Based on the unique working mode of the PT-MR damper for whole-spacecraft vibration isolation, the damper under shear mode was proposed. Under the shear working mode, the pressure difference on both sides of the damping gap is zero. When the upper working plate moves to the left at a velocity of v0, the fluid shear velocity vg in the gap is a gradient function in the y-direction:

where Hd is the working distance between the moving plate and fixed plate.

At this point, the shear force Fs generated by the MR material can be divided into two parts:

where Fz is the viscous induced force and Fδ is the magnetic induced force.

The viscous induced force caused by the intrinsic viscosity of the MR material and the magnetic induced force caused by the magnetic field can be expressed as follows:

where ƞ is the apparent viscosity of the MR material, v is the moving velocity of the moved plate, L is the length of the moved plate, and b is the width of the moved plate.

Under the cylindrical shear mode with a constant gap size, the shear force Fs generated by the MR material can be calculated as

where l is the length of the damping gap, h is the gap size of the damping gap, and D is the diameter of the cylinder.

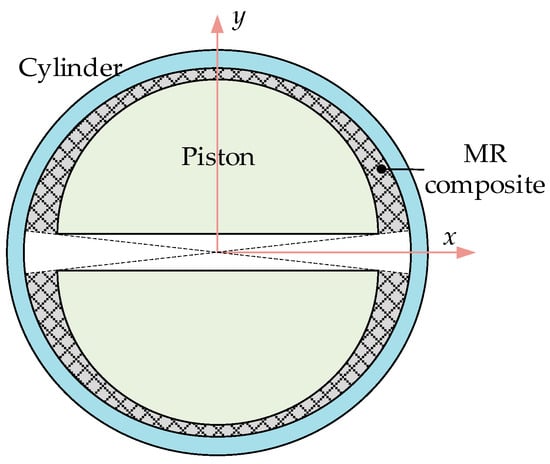

For the PT-MR damper, its damping gap is the channel formed by the two eccentric cylinders, which is not a concentric circular channel. The structure of this damping gap is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Cross-section of damping gap.

When the split-type piston moves radially outward, a damping gap, as shown in the figure, will be formed, and the MR composite will be subjected to uneven compression. Therefore, a detailed analysis of the squeeze state of the MR composite at the damping gap is required.

Figure 6 shows the schematic diagram of the damping gap when the radial movement of the upper separation piston is q. Assume that the radius of the inner wall of the cylinder is R, the outer diameter of the piston is r, and the radial displacement of the piston on one side is q. Draw a straight line L1 passing through the origin, with an inclination angle of θ, intersecting with the outer profile of the piston and the inner profile of the cylinder at points a and b, respectively. Turning the straight line counterclockwise by an angle of dθ forms a straight line L2, which intersects with the outer profile of the piston and the inner profile of the cylinder at points c and d, forming a tiny element Sabcd. Analyze the area variation pattern of the infinitesimal.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of damping gap change.

From the geometric relationship, it can be seen that the tangent between the line segment ab and the arc segment bd at point b is always perpendicular. Therefore, the infinitesimal is approximated as a rectangle, and its area dS can be calculated as

where lab is the length of the line segment ab, and the arc segment Cbd can be calculated as

where R is the inner radius of the cylinder and dθ is the differential of the angle θ.

The length of the line segment lab can be expressed as

where xa and ya are the coordinates of point a.

Combine the equation of the outer contour line of the piston with the equation of the straight line:

where r is the radius of the piston and q is the radial adjustment displacement of the piston.

The coordinates of the intersection point a of the two lines can be obtained:

At the same time, the expression for the infinitesimal area is obtained:

When the piston moves radially with a distance q = 0, the initial area of the infinitesimal is

Then, for the volume element corresponding to any angle θ, the volumetric strain should be

By referring to Equations (1), (4), (7), (8), and (18), the shear stress (damping force) acting on the infinitesimal A can be obtained as

That is,

Then, the damping force acting on the piston is the integral of the volume infinitesimal over the entire cross-sectional area (as shown in Figure 5) of the piston:

Therefore, the damping force for the PT-MR damper can be derived as follows:

where θ0 is the angle between the side of the split-type piston and the x-axis. When the split-type piston is in the state with minimal damping, θ0 = 0.

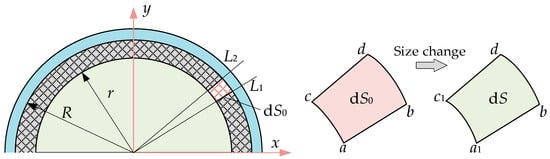

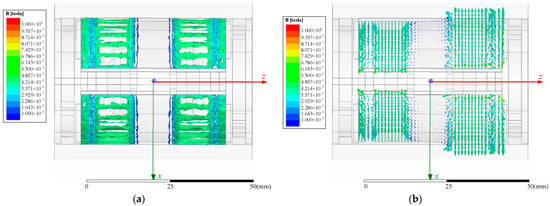

2.4. Simulated Analysis of Magnetic Circuit

Furthermore, we used ANSYS Maxwell software (Version 19.2.0) to analyze the magnetic field distribution of the PT-MR damper. According to the grade (N42) of the PMs, determine the magnetization intensity and direction (axial magnetization with an intensity of 955 kA/m). Assign material properties based on the material type of each component (20# steel, 45# steel, and MR composite were imported as magnetic permeability based on their respective B-H curves), and select the magnetic flux density at the damping gap as the solution object. The minimum gap size of the simulation is 0.2 mm~1.0 mm, and the final simulation results are as follows.

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the simulation results and the variation law of the magnetic flux density for the different gap sizes of the PT-MR damper (the z-axis is the axial direction and the x-axis is the radial direction). The analysis of simulation results shows that the magnetic flux lines are mainly distributed on both sides of the piston body along the z-axis, namely, at the magnetic rings, and the middle gap along the z-axis is the movable gap of two split-type pistons, which is the air gap, and the magnetic field is extremely weak. As shown in Figure 8, the magnetic flux density at the damping gap follows a gradient distribution along the axial direction of the piston, with high magnetic flux density at small gap size. As the gap size increases, the induced magnetic field will attenuate to a certain extent, which corresponds to the magnetic field’s theoretical analysis. At the same time, when the PM is magnetized axially, the direction of the induced magnetic field is perpendicular to the damping gap, which proves that the magnetic circuit design of the damper is reasonable. When the minimum gap size is reduced from 1.0 mm to 0.2 mm, the magnetic flux density increases from 0.45 T to about 1.27 T, indicating that changing the size of the damping gap can adjust the magnetic flux density within a larger range, verifying the accuracy of the principle.

Figure 7.

Distribution of magnetic field of the main body of the piston (gap size of 1 mm). (a) Contour of magnetic flux density, (b) vector magnetograms.

Figure 8.

Magnetic field simulation results. (a) Gap size of 1.0 mm, (b) gap size of 0.6 mm, (c) gap size of 0.2 mm.

It is worth noting that when the magnetic flux density at the damping gap changes along the piston axis direction, there are three sudden drops in density. This is due to the presence of two ring grooves on the magnetic ring that fit with the shaft clamp. There is no MR composite on the grooves. Also, the sudden drop in density on the middle position is caused by the magnetization direction of the PMs, so there is almost no magnetic field passing through the middle area (corresponding to the middle part along the x-axis in Figure 7a or Figure 7b; this position is the PMs).

3. Experimental Analysis of Proposed MR Damper

3.1. Experimental Test

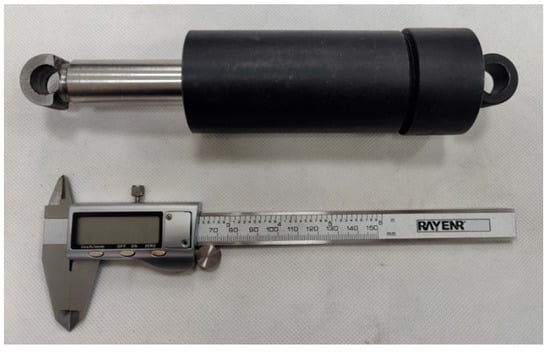

Based on the theoretical analysis of the PT-MR damper, the feasibility of the damper’s design has been verified. Furthermore, based on the design and simulation of the proposed damper, the actual assembly prototype of the PT-MR damper was fabricated as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Prototype of proposed MR damper.

In this work, the thread lead on the adjusting screw rod is 1.5 mm, and the taper angle of the tip cone is 45°, so the minimum gap size increment Δh is equal to the axial displacement Δx of the tip cone and the initial minimum gap size h0 = 2 mm. Based on this, the relationship between the adjustment angle θ and the minimum gap size h is shown in Table 1. When the gap size reaches its maximum (Δh = 1.6 mm), the axial displacement of the tip cone is 1.6 mm, corresponding to a maximum adjustment angle of θ = 384°.

Table 1.

Relationship between adjustment angle and minimum gap size.

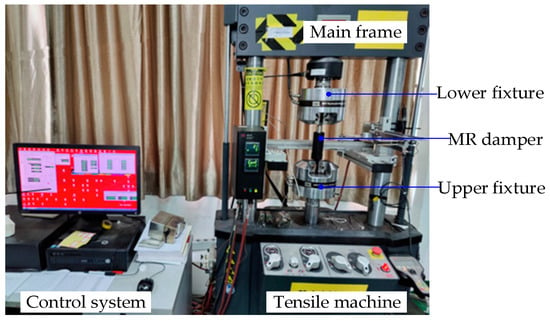

This research uses an MTS tensile machine (MTS, Shanghai, China) to test the mechanical properties of the PT-MR damper, as shown in Figure 10. The testing system includes an MTS tensile machine, upper and lower fixtures, a prototype of the PT-MR damper, and a PC. In this test, the MTS tensile machine is used as an excitation source to provide sine excitation signals of different frequencies and amplitudes, providing cyclic excitation for the proposed damper. The force data of the damper is collected through the force sensor and transmitted back to the PC. The upper fixture is connected to the MTS moving part and transmits displacement excitation signals to the damper piston to drive the system to work. We adjusted the frequency, amplitude, and number of cycles of the applied motion excitation on the PC, which displays the output characteristic curve of the proposed damper in real time during testing.

Figure 10.

Experimental set-up of proposed MR damper.

Subsequently, it is necessary to analyze the test results of the output characteristics of the PT-MR damper. We analyzed the indicator curves and velocity characteristic curves of the damper under different adjustment angles, frequencies, and amplitudes. By integrating the single cycle indicator curve of the damper, the envelope area of the curve can be obtained, which is the dissipated energy E (a single cycle). Based on the single-cycle dissipated energy of the damper, the equivalent damping coefficient Ceq of the proposed damper can be obtained.

where f is the test frequency and X is the test amplitude for the damper.

3.2. Experimental Analysis

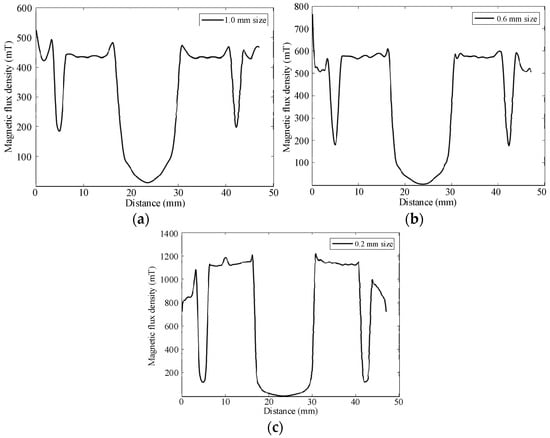

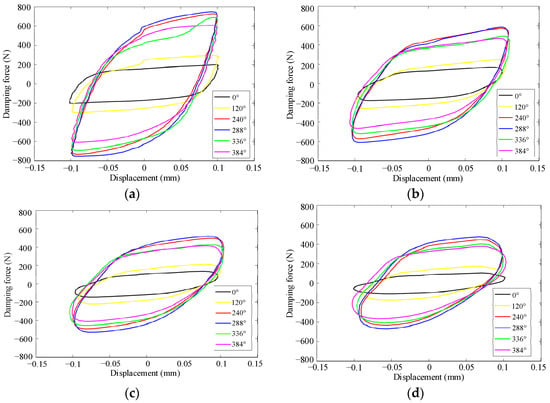

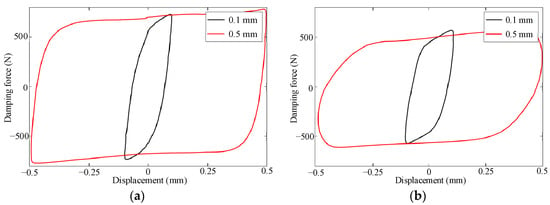

Figure 11 illustrate the variation of the output characteristics of the PT-MR damper with the adjustment angle under different frequencies (amplitude of 0.1 mm). It can be seen that under the fixed amplitude and frequency, the maximum output force and the envelope area of the force–displacement curve show the phenomenon of first increasing and then decreasing with the increase in the adjustment angle. This indicates that in the initial stage (adjustment angle of 0–240°), as the gap size decreases, the magnetic flux density at the gap increases while the MR composite is squeezed, producing a squeeze strengthening effect and increasing the output force of the PT-MR damper. But, when the angle exceeds 240°, the MR composite is subjected to excessive squeeze, causing the MR fluid adsorbed on the non-woven fabric to be squeezed out of the damping gap, reducing the output capacity of the PT-MR damper.

Figure 11.

Variation of the damping characteristics with the adjustment angle under different frequencies (amplitude of 0.1 mm). (a) 5 Hz, (b) 15 Hz, (c) 20 Hz, (d) 25 Hz.

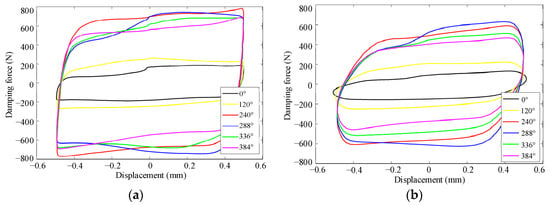

The damping characteristic curves of the PT-MR damper at different frequencies with an amplitude of 0.5 mm are shown in Figure 12. The peak force variation pattern is similar to that of the 0.1 mm micro-amplitude condition, but the curves under 0.5 mm amplitude are fuller, and there is no obvious slope characteristic in the upper left and lower right corners, indicating that the viscoelastic properties exhibited by the MR composite are no longer significant at large amplitudes. As the vibration frequency increases, the damping force decreases to a certain extent. The main reason is that with the increase in shear rate, the magnetic particle chains in the MR composite will disperse to a certain extent, and the overall viscosity will decrease.

Figure 12.

Variation of the damping characteristics with the adjustment angle under different frequencies (amplitude of 0.5 mm). (a) 5 Hz, (b) 15 Hz.

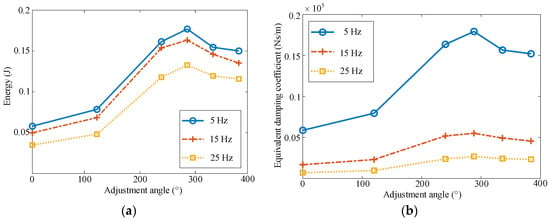

The single-cycle energy dissipated of the PT-MR damper under amplitudes of 0.1 mm is shown in Figure 13a, and the equivalent damping coefficient curve is shown in Figure 13b. When the adjustment angle increases from 0° to 288°, the energy dissipated by the damper under 5 Hz and 0.1 mm increases from 0.058 kN·mm to 0.177 kN·mm, and the equivalent damping coefficient increases from 5.88 × 104 N·s/m to 17.93 × 104 N·s/m. When the adjustment angle increases from 288° to 384°, the energy dissipated per cycle of the PT-MR damper under 5 Hz and 0.1 mm decreases from 0.177 kN·mm to 0.150 kN·mm, and the equivalent damping decreases from 17.93 × 104 N·s/m to 15.22 × 104 N·s/m.

Figure 13.

Performance curves of the PT-MR damper under different frequencies. (a) Energy dissipated under 0.1 mm amplitude. (b) Equivalent damping coefficient under 0.1 mm amplitude.

From the results, it can be seen that the single-cycle energy dissipated and the equivalent damping coefficient of the PT-MR damper increase first and then decrease with the increase in the adjustment angle, which is consistent with the trend of the force–displacement curves. It is worth noting that the energy dissipated by the proposed damper increases more in the initial stage than it decreases in the later stage, indicating that as the gap size continues to decrease, the squeeze strengthening effect of the MR composite at the damping gap continues to increase, offsetting the energy dissipation reduction effect caused by the loss of MR fluid inside of the damping gap.

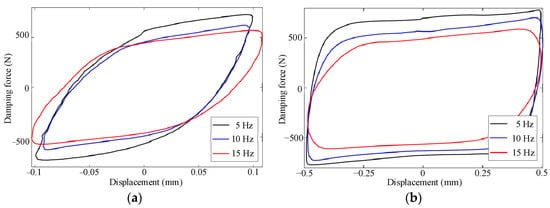

To verify the energy dissipation capability of the PT-MR damper, based on experimental data analysis, the variation of the force–displacement curves of the PT-MR damper with frequency under excitation amplitudes of 0.1 mm and 0.5 mm at a fixed adjustment angle of 240° (minimum gap size of 1 mm) is shown in Figure 14. With the increase in excitation frequency, the maximum damping force of the damper and the envelope area of the curves decrease slightly, indicating that the increase in excitation frequency will slightly weaken the output capability of the PT-MR damper.

Figure 14.

Damping characteristics with different frequencies. (a) Amplitude of 0.1 mm, (b) amplitude of 0.5 mm.

Based on the test results of the PT-MR damper, a comparative analysis was conducted on the variation of the force–displacement curves of the PT-MR damper with amplitude under excitation frequencies of 5 Hz and 15 Hz at a fixed adjustment angle of 240° (minimum gap size of 1 mm), as shown in Figure 15. The increase in excitation amplitude hardly affects the output damping force, and the force–displacement curves only extend along the displacement direction (x-axis) under different amplitudes, indicating that the output performance of the proposed damper is not affected by amplitude and can effectively dissipate vibration energy under amplitudes of 0.1 mm~0.5 mm.

Figure 15.

Damping characteristics with different amplitudes. (a) Frequency of 5 Hz, (b) frequency of 15 Hz.

4. Whole-Spacecraft System Simulation Analysis

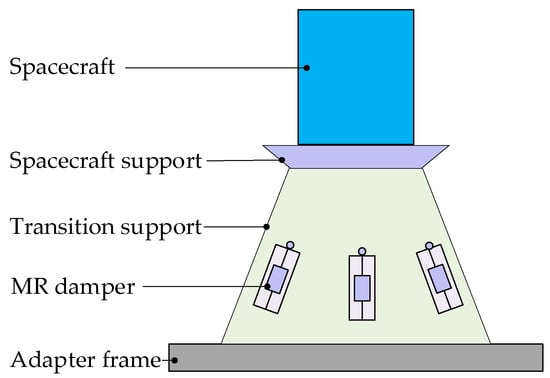

The whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platform is the connecting part between the carrier rocket and the spacecraft that can simultaneously achieve the functions of connecting and fixing the spacecraft as well as vibration isolation. During the rocket launch process, the vibration energy is gradually amplified through the structure of the spacecraft support, transition support, and adapter frame, resulting in severe vibration of the spacecraft. The traditional isolation measure for the whole-spacecraft platform is to connect an isolation system in series between the transition support and the adapter, but this will result in a decrease in the overall stiffness of the platform, affecting the stability of the spacecraft during launch.

The MR whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platform is shown in Figure 16. It abandons the traditional series vibration isolation scheme. Instead, eight MR dampers are uniformly arranged in parallel along the circumference of the transition support as the damping element, solving the problem of stiffness loss of traditional whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platforms and achieving the integration of carrying and vibration isolation functions of the platform.

Figure 16.

Structure of whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platform.

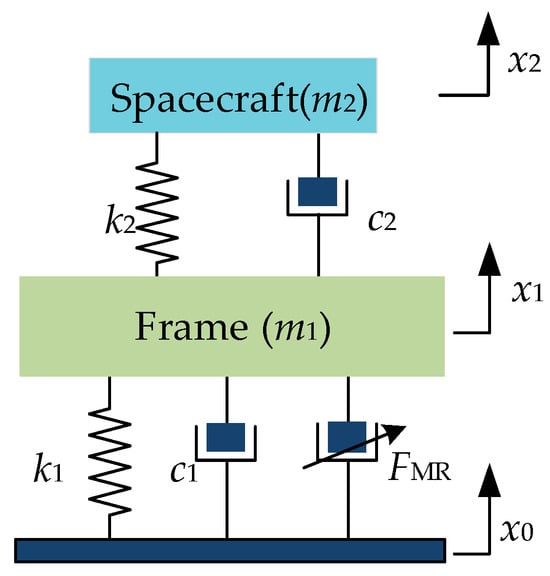

Dynamic modeling of the MR whole-spacecraft vibration isolation system was conducted by considering the spacecraft and transition support as a concentrated mass form in the modeling, ignoring the lighter structural mass of the spacecraft support, and rendering equivalent the two supports as a parallel form of stiffness and damping elements. The simplified two-degree-of-freedom model of the MR vibration isolation platform is shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Simplified two-degree-of-freedom model of the vibration isolation system.

The simplified two-degree-of-freedom model can be expressed as

where m1 and m2 are the concentrated masses of the transition support and the simulated spacecraft, c1 and c2 are the equivalent damping coefficients of the transition support and the spacecraft support, k1 and k2 are the equivalent stiffness coefficients of the transition support and the spacecraft support, x1 and x2 are the absolute displacements of transition support and the spacecraft support, x0 is the vibration displacement transmitted from the carrier rocket to the adapter frame, FMR is the damping force provided by a single PT-MR damper, and α is the vertical installation angle of the MR damper (α = 40°).

In order to apply the characteristics of the PT-MR damper more accurately and efficiently to the vibration isolation system, it is necessary to model and characterize the test results of the damper. In this part, the hyperbolic tangent model was selected to fit the PT-MR damper. The model is expressed as

where the unit of velocity is mm/s, the unit of displacement x is mm, the unit of adjustment angle θ is °, and the unit of output damping force FMR is kN.

Based on the mechanical characteristic curves of the damper under different conditions obtained from the experiment in Section 3, the functional relationship between the adjustment angle θ and each parameter was obtained through parameter identification and polynomial fitting. The expressions of each parameter with respect to the adjustment angle θ are as follows:

The matrix form of the simplified two-degree-of-freedom model is

where X is the displacement matrix, M is the mass matrix of the system, C is the damping matrix of the system, K is the stiffness matrix of the system, G is the excitation matrix, and Γ is the position matrix of the MR damper.

Based on the actual structure of the MR whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platform, the actual values of key parameters of the model are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of MR whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platform model.

The concentrated masses of the transition support and the simulated spacecraft in Table 2 were set according to the actual parameters of the target spacecraft. Other damping and stiffness parameters were obtained by building the entity model of the vibration isolation platform and using finite element analysis software to obtain the modal vibration of each order of the system. The optimal damping and stiffness parameters that meet the vibration isolation requirements were analyzed and obtained.

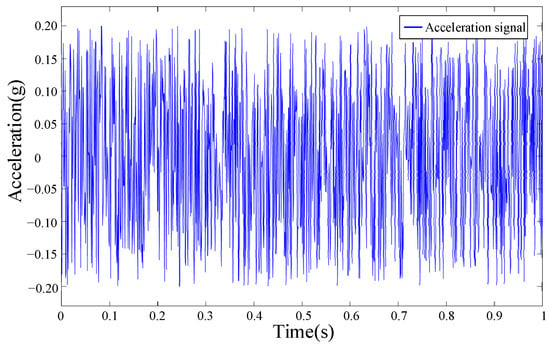

For the theoretical model of Equation (27), the model’s framework was established using Simulink software. Taking the two-degree-of-freedom model of the MR whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platform as the research object, random excitation was applied to the vibration isolation system to further verify the isolation performance of the proposed damper at different adjustment angles. The acceleration signal used in the simulation is shown in Figure 18. For the convenience of analysis and evaluation, we take the gravitational acceleration ‘g’ as the basic unit of acceleration.

Figure 18.

Time domain diagram of acceleration under random excitation.

Table 3 shows the simulation results of spacecraft acceleration under the different working conditions of no damper and different adjustment angles of screws after installing the damper, which were used to evaluate the vibration isolation performance of the PT-MR damper.

Table 3.

Simulation results of vibration isolation effect.

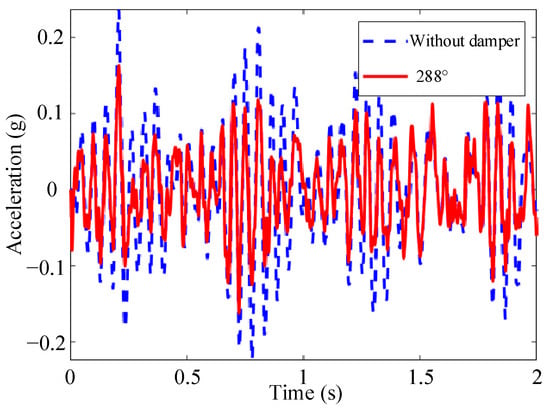

According to the results in Table 3, it can be seen that after installing the PT-MR damper, the maximum acceleration and root mean square (RMS) acceleration of the spacecraft both decrease to a certain extent, and this degree of decrease is affected by the adjustment angle of the adjusting screw rod. When the adjusting angle increases from 0° to 288°, the maximum acceleration and RMS acceleration of the spacecraft under random excitation decrease with the increase in the adjustment angle. When the adjustment angle increases from 288° to 384°, the maximum acceleration and RMS acceleration of the spacecraft under random excitation increase with the increase in the adjustment angle. This phenomenon is consistent with the variation law of single-cycle energy dissipated by the PT-MR damper with the adjustment angle shown in Figure 13b. When the adjustment angle is 288°, the damper leads to relatively large energy dissipation in a given period, and its damping effect is relatively good. When the system does not install the PT-MR damper and the adjustment angle of the adjusting screw rod is 288°, the acceleration time–domain diagram of the spacecraft under random excitation is shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Comparison of acceleration results between installing and not installing damper.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a PT-MR damper using the MR composite was proposed, aimed at improving the performance of the shear-type MR damper for the whole-spacecraft vibration isolation condition.

- (1)

- The squeeze strengthening effect of the MR composite at the damping gap was analyzed, and the mechanical model of the damper was derived based on the squeeze principle.

- (2)

- The mechanical performance of the PT-MR damper was tested and analyzed. The results indicate that the proposed damper can generate a damping force greater than 800 N, and the output force increases with the adjustment angle within a certain range.

- (3)

- A whole-spacecraft vibration simulation system was built, and the results showed that the damper had a good damping effect at the adjustment angle of 288°. Compared with the situation without the proposed damper installed, the RMS of spacecraft acceleration decreased from 0.0806 to 0.0528, a decrease of 34.49%. This indicates that the proposed damper can effectively dissipate the vibration energy of the vibration isolation platform and improve the vibration situation of the spacecraft.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W. and L.W.; methodology, X.D.; software, L.W. and J.W.; validation, K.W. and L.W.; formal analysis, X.D.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, X.D.; data curation, X.F.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review and editing, L.W.; visualization, K.W.; supervision, X.D.; project administration, X.D.; funding acquisition, X.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported financially by the ‘National Natural Science Foundation of China’ (Grant No. 52475088) and the ‘Science and Technology Program of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region’ (Project No. 2025YFHH0060).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PT-MR | Passive-tuned magnetorheological |

| MR | Magnetorheological |

| PMs | Permanent magnets |

| RMS | Root mean square |

References

- Chiu, M.C.; Von-Mehlem, U.I.; Willey, C.E.; Betenbaugh, T.M.; Maynard, J.J.; Krein, J.A.; Conde, R.F.; Gray, W.T.; Hunt, J.W.; Mosher, L.E.; et al. ACE spacecraft. Space Sci. Rev. 1998, 86, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Che, J.; Shu, H.; Bai, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, W.; Wu, J.; Chen, X. Stewart-inspired vibration isolation mechanisms for precision equipment: Current status and future research trend. Mech. Mach. Theory 2025, 214, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.T.; Abubakar, M.; Bai, X.T.; Luo, Z. Vibration isolation methods in spacecraft: A review of current techniques. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 3993–4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.K.; Zheng, G.T. Parameter analysis of PAF for whole-spacecraft vibration isolation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2007, 11, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, B.; Zang, J. Dynamic features of passive whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platform based on non-probabilistic reliability. J. Vib. Control 2015, 21, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Gai, P.P.; Xu, Z.D.; Yan, X.; Guo, Y.Q.; Huang, X.H. A hybrid constitutive model of high-damping viscoelastic materials used for vibration control of civil structures. Eng. Struct. 2024, 210, 117648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, P.S.; Johnson, C.D.; Fosness, E.R. Whole-spacecraft passive launch isolation. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 1998, 35, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, H.Y.; Chen, Z.B.; Tzou, H.S. Experiments on active precision isolation with a smart conical adapter. J. Sound Vib. 2016, 374, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Z.B.; Tzou, H.S. Torsion and transverse sensing of conical shells. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2010, 24, 2235–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Marneffe, B.; Avraam, M.; Deraemaeker, A.; Horodinca, M.; Preumont, A. Vibration isolation of precision payloads: A six-axis electromagnetic relaxation isolator. J. Guid. Control Dynam. 2012, 32, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Xing, J.; Chen, Z.; Pan, Z. Design, analysis and experimental investigation on the whole-spacecraft vibration isolation platform with magnetorheological dampers. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 075016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, Z.; Yin, X. Research on multi-dimensional vibration isolation control system based on a parallel mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Information and Automation, Macao, China, 18–20 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Pan, Z.; Xing, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yan, M.; Dong, X. Controllability analysis and intelligent control of magnetorheological whole-satellite under small amplitude and medium-high frequency vibration. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2023, 34, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edberg, D.L.; Wilke, P.; Davis, T.; Fosness, E. On the design and testing of a spacecraft launch vibration isolation system (LVIS). In Proceedings of the 38th Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 7–10 April 1997; pp. 1494–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, X. Active vibration isolation using a six-axis orthogonal vibration isolation platform with piezoelectric actuators. J. Vibroeng. 2017, 19, 6105–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Ying, S.; Qi, H.; Yu, L.; Li, G. Design, analysis and optimization of a hybrid fluid flow magnetorheological damper based on multiphysics coupling model. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 205, 110877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Ma, L.; Chu, F. Rotor vibration control via integral magnetorheological damper. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 252, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Numerical simulation and torsional vibration mitigation of spatial eccentric structures with multiple magnetorheological dampers. Actuators 2022, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Ruan, X.; Xuan, S.; Yan, Q.; Deng, H. Magnetorheological damper working in squeeze mode. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2014, 6, 410158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Yau, H.; Lee, C.; Tung, K. System identification and semiactive control of a squeeze-mode magnetorheological damper. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mech. 2013, 18, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Yoon, I.; Kim, B.; Han, Y.; Park, S.; Hwang, H.; Kim, S. A haptic knob based on the combination of shear mode and flow mode magnetorheological behaviors. Smart Mater. Struct. 2023, 32, 75011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, W. Modeling of magnetorheological fluid in quasi-static squeeze flow mode. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 65022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkal, D.; Gurocak, H. Serpentine flux path for high torque MRF brakes in haptics applications. Mechatronics 2010, 20, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Hu, W.; Choi, Y.T.; Wereley, N.M.; Browne, A.L.; Ulicny, J.; Johnson, N. Nonlinear modeling of magnetorheological energy absorbers under impact conditions. Smart Mater. Struct. 2013, 22, 115015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Mao, Y.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Wei, X. Modelling and optimization of high frequency hardening characteristics of magneto rheological damper. J. Vib. Shock. 2016, 35, 120–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Dong, X.; Xu, D. A passive-tuned damper based on magnetorheological porous fabric composite. Smart Mater. Struct. 2024, 33, 115013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldasz, J.; Alexandridis, A.A. Medium- and high-frequency analysis of magnetorheological fluid dampers. J. Vib. Control 2012, 18, 2140–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.M.; Li, P.Y.; Yan, M.S.; Li, X. Characteristic analysis under small-stroke and medium-high frequency of magneto-rheological damper with pressure controlled mechanism. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 045011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, F.; Chen, Z.; Hua, L.; Jiao, Y.H.; Li, M.Z.; Huang, W.H. Research on dynamic characteristics of a magnetorheological damper with decoupling mechanism. In Proceedings of the ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 4–7 September 2007; pp. 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Chen, Z.B.; Xing, J.W. Design, analysis, and experimental evaluation of a magnetorheological damper with meandering magnetic circuit. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2018, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Dong, X.; Yan, H.; Wang, K.; Ran, J.; Yang, R. Performance evaluation of magnetorheological fluid porous fabric composite based on a novel constitute model. Compos. Struct. 2023, 322, 117363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R. Super-strong magnetorheological fluids. J. Phys.-Condens. Mat. 2001, 13, 979–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wu, H.; Ran, J.; Shan, H.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, R.; Dong, X. Industrial pipeline vibration attenuation with magnetorheological tuned mass damper. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2025, 36, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).